1. Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) is a highly contagious disease of domestic, synanthropic and wild birds, occurring as an epizootic or enzootic disease, characterized by damage to the respiratory organs and gastrointestinal tract, general depression, and decreased productivity. HPAI is caused by various antigenic variants of the influenza virus subtype A [

1]. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, former OIE) classifies HPAI as a particularly dangerous transboundary zoonotic infection [

2]. Acute epizootic outbreaks caused by subtypes H5 and H7 of the virus are the most dangerous and, as a rule, are accompanied by catastrophic consequences with losses of 75 to 100% of the livestock [

3]. Bird flu is also a serious public health problem. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), between 2003 and 2020, 861 cases of H5N1 influenza with 455 fatal outcomes have been registered among the population of 17 countries [

4,

5].

According to WHO, in 2020, HPAI was registered in 20 countries of the world (countries of Europe, Africa, Asia, including Russia, China, Kazakhstan, etc.) [

2,

6,

7,

8,

9]. At the time when this manuscript was written in January 2025, HPAI routinely recurs and is registered in many countries of Europe, Africa, Asia. For example, in November 2024 alone, about 16 cases of infection of domestic and wild birds were notified to the WOAH information system WAHIS, including countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, Hungary, the Philippines, etc. In total, 90 HPAI outbreaks were registered in the world in 2024 [

10]. HPAI is a transboundary animal disease by nature. For example, in 2020, when an epidemic of was reported in Kazakhstan, outbreaks (January-May) were also recorded in China, Russia, Iraq, Vietnam [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Ongoing outbreaks are still present in Afghanistan, China, India, Korea, the Philippines and Vietnam among poultry (subtypes H5, H5N1, H5N2, H5N5, H5N6 and H7N9) [

4,

10,

12,

15,

16].

The epidemiological situation of HPAI is difficult for Kazakhstan. The first HPAI outbreaks in Kazakhstan were registered in 2005 [

17,

18]. Subsequently, intensive vaccination of poultry was implemented. However, despite all the measures taken, in 2020 outbreaks of avian influenza caused enormous damage to the poultry industry of Kazakhstan. In September 2020, the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Kazakhstan reported a HPAI outbreak in the North Kazakhstan region and its spread to other regions. In total, 11 outbreaks of infection were registered that year in the Akmola, Almaty, Kostanay, Pavlodar and North Kazakhstan regions [

19]. In 2021, five more outbreaks of infection were notified in the Akmola, Aktobe, Pavlodar and North Kazakhstan regions [

6,

10,

20]. In the outbreaks, quarantine was declared and temporary restrictions were introduced on the export of live poultry and poultry products, which had a significant impact on the rise in prices for eggs and poultry meat [

21].

Several routes of seasonal bird migration pass through the territory of Kazakhstan. At the same time, the Central Asian-Indian and East Asian bird migration routes intersect with the Black Sea-Mediterranean and East African-West Asian pathways in the west of the Republic [

22]. In Kazakshtan, 130 species of birds have been registered during the nesting, molting, seasonal migrations and wintering periods. Every year, the number of nesting bird species reaches 10 million, 2-3 million birds arrive for molting, and about 50 million migratory birds stop on Kazakhstani water bodies during the spring and autumn migrations [

23]. At the same time, a number of studies by Kazakh scientists confirm the transcontinental route of introduction of the HPAI virus, where wild migratory birds play the role of a reservoir. Thus, whole-genome sequencing of avian influenza virus in Kazakhstan during disease outbreaks in 2020 showed that the isolated strains are associated with isolates from Southern Russia, the Russian Caucasus, the Ural region, Southwestern Siberia and Eastern Europe [

6]. In Northern Kazakhstan, the influenza virus strain A/chicken/North Kazakhstan/184/2020 (H5N8) was isolated, phylogenetic analysis of which showed significant genetic similarity of the isolate in all eight genes with highly pathogenic H5 influenza viruses isolated from poultry in the Middle East and West Africa [

20]. Also, during the influenza outbreaks in 2021 in the North Kazakhstan and Akmola regions among poultry caused by the avian influenza A/H5N8 virus, it was established that the Kazakhstani isolates of HPAI H5N8 belong to the 2.3.4.4b clade with a high level of homology (98.42–98.70%) to the strains from China [

21]. In addition, during the epidemiological surveillance of avian influenza viruses in wild birds in 2018–2019, the simultaneous circulation of genome segments of Asian, European, and Australian genetic lineages of the H3N8 AIV virus was established in wild birds in Kazakhstan, which confirms the important role of Kazakhstan and Central Asia as a center for the transmission of avian influenza viruses, linking the migration routes from East Asia to Europe and vice versa [

24].

At the same time, despite the long history of studying the ecology of avian influenza viruses in Kazakhstan, many key aspects of the HPAI epidemiology remain insufficiently studied. In particular, anthropogenic and natural-climatic factors influencing the epidemiology of the disease have not been determined, the mechanisms of transboundary spread of infection are not fully understood, and there is no ranking of the territory with an assessment of the risk of occurrence and spread. The purpose of this work was to model the suitability of the territory of Kazakhstan for the occurrence of HPAI outbreaks using an ecological niche model based on information from a number of neighboring countries with similar climatic conditions, as well as to assess the impact of a number of climatic, landscape and socio-economic factors on the epidemiological process of the disease. Results will help evaluate the effectiveness of the surveillance system for HPAI in Kazakhstan, contributing to the implementation of measures intended to prevent and mitigate the impact of the disease in the country.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

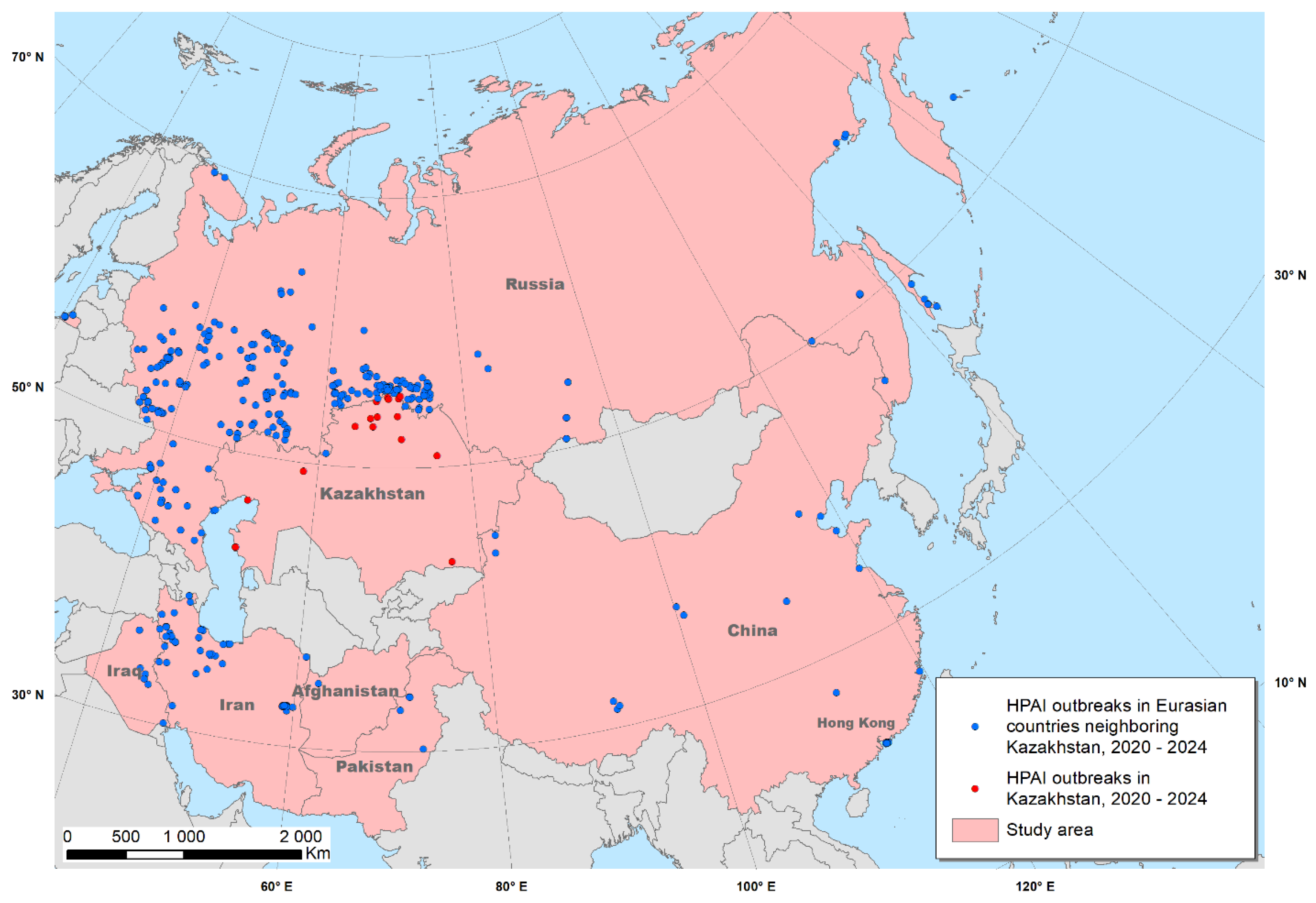

The study area comprised Kazakhstan and neighboring countries in Eurasia considered to be similar to Kazakhstan in terms of their climatic and geographic conditions and in which HPAI outbreaks were reported in 2020 – 2024. Those countries included Afghanistan, China and Hong Kong, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and Russia (

Figure 1). Inclusion of those countries was necessary because of the limited number of outbreaks reported in Kazakhstan. The addition of data from countries considered to be similar to Kazakhstan is expected to support the identification of associations between outbreaks and predictors, contributing to the ultimate objective of identifying areas in which the disease may have been under-reported in Kazakhstan.

2.2. HPAI Data

Spatially referenced data on Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreaks were collected from FAO Empres-i database (

https://empres-i.apps.fao.org/). The attributes of the data include geographical coordinates, virus serotype, location name, dates of disease observation and reporting, and the source of information. Only outbreaks attributed to WOAH (former OIE) were used for the analysis. The total number of HPAI outbreaks during the study period were 17 in Kazakhstan (hereinafter “test data”) and 444 in the rest of the study area (hereinafter “training data”) (

Table 1). Outbreaks in domestic and wild birds were treated together as indicators of HPAI virus presence [

25].

2.3. Study Design

First, the environmental suitability to HPAI was evaluated for the whole study area using only training data. Subsequently, the model was tested on Kazakhstan data to evaluate whether the fitted model was able to adequately predict the observed HPAI outbreaks in Kazakhstan, and whether there are areas of over- or underprediction. Finally, the numbers of HPAI outbreaks by country were compared to the summary environmental suitability in the corresponding country, calculated as the sum of cells with suitability >50%.

An ecological niche model based on the principle of Maximum Entropy (Maxent) was used to evaluate an environmental suitability to HPAI [

25]. We chose a set of potential explanatory variables including a number of climatic, landscape and socioeconomic factors (

Table 2), which demonstrated significance in explaining the observed distribution of HPAI cases in similar studies [

25,27–29]. The set of environmental variables included: population density, land cover, human footprint index, chicken population density, maximum green vegetation fraction, altitude, mean yearly air temperature, yearly precipitation, minimum temperature of coldest month, precipitation seasonality, precipitation of driest quarter and precipitation of warmest quarter. All raster layers were clipped by the extent of the study area and transformed to the same resolution of 10×10 km2, defined by the layer with the coarsest resolution (namely FAO global chicken density). Model performance was assessed by the mean AUC value that indicates an ability of the model to correctly predict any random presence location. AUC values exceeding 0.8 are normally considered a “high indicator”, values 0.7<AUC<0.8 are considered “good indicator”, while AUC around 0.5 indicate no predictive power of the model [30].

Further, test data (namely HPAI outbreaks in Kazakhstan) were used in the same model to assess the model performance. The AUC value was obtained and compared with the AUC of trained model. Test data were overlaid with the predicted suitability surface and conclusions were made about the adequateness of the prediction.

To test the importance of the variables, a Jackknife test was used. For each individual variable, it runs model without this variable, and with only this variable, comparing a test gain with the full model.

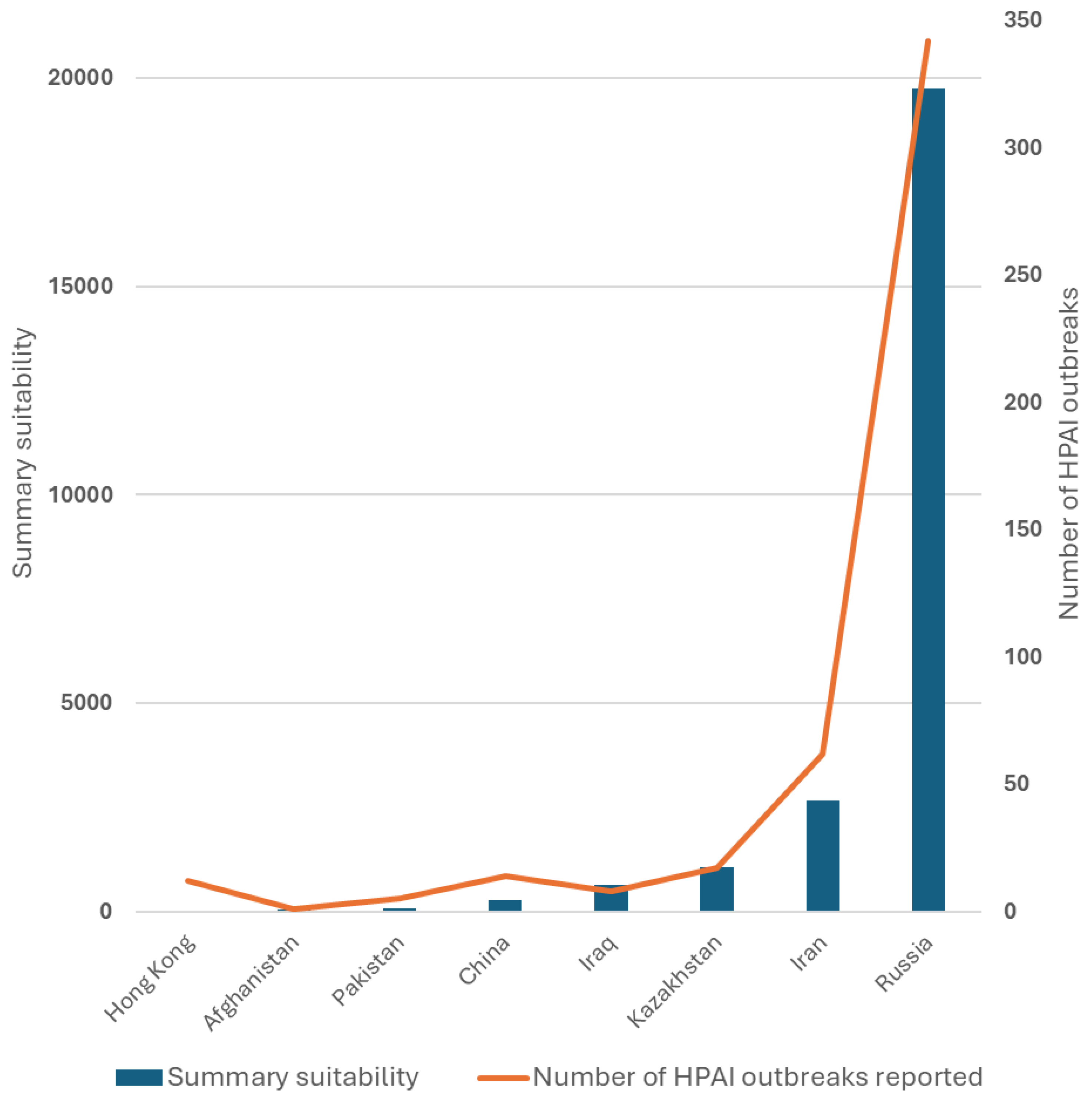

To assess potential over- or underreporting of HPAI outbreaks by country, we calculated a summary suitability as a number of raster cells per country, where the predicted suitability exceeds 50%. We then plotted this summary suitability against the reported number of HPAI outbreaks and applied a Negative Binomial linear regression model to assess a goodness of the summary suitability as a predictor of the number of outbreaks per country.

2.4. Software

Spatial data mapping and processing was performed by means of ArcGIS for Desktop v 10.8.2 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). Maxent model was fitted in Maxent software [31]. Negative Binomial model was built in statistically oriented programming software R with MASS package [32].

Table 1.

The number of HPAI outbreaks within the study area, 2020 - 2024.

Table 1.

The number of HPAI outbreaks within the study area, 2020 - 2024.

| Number of HPAI outbreaks |

In domestic birds |

In wild birds |

| Afghanistan |

1 |

0 |

| China |

1 |

13 |

| Hong Kong |

0 |

12 |

| Iran |

57 |

5 |

| Iraq |

8 |

0 |

| Kazakhstan |

14 |

3 |

| Pakistan |

5 |

0 |

| Russia |

241 |

101 |

Figure 1.

Study area and HPAI outbreaks, 2020 – 2024.

Figure 1.

Study area and HPAI outbreaks, 2020 – 2024.

Table 2.

The list of environmental variables used in ecological niche modeling of HPAI in Eurasian countries.

Table 2.

The list of environmental variables used in ecological niche modeling of HPAI in Eurasian countries.

| Variable name |

Variable meaning |

Measurement unit |

| alt |

Altitude above the sea level |

meters |

| landcov |

Type of land cover |

categories |

| mgvf |

Maximum green vegetation fraction |

% |

| pop_dens |

Population density |

Persons/km2

|

| hum_ftprnt |

Human footprint index (a measure of human influence on the terrestrial systems of the Earth) |

index |

| chicken_dens |

Chicken density |

Head/km2

|

| bio_1 |

Annual Mean Air Temperature |

℃*10 |

| bio_6 |

Minimum Air Temperature of Coldest Month |

℃*10 |

| bio_12 |

Annual Precipitation |

Millimeters |

| bio_15 |

Precipitation Seasonality |

% |

| bio_17 |

Precipitation of Driest Quarter |

Millimeters |

| bio_18 |

Precipitation of Warmest Quarter |

Millimeters |

3. Results

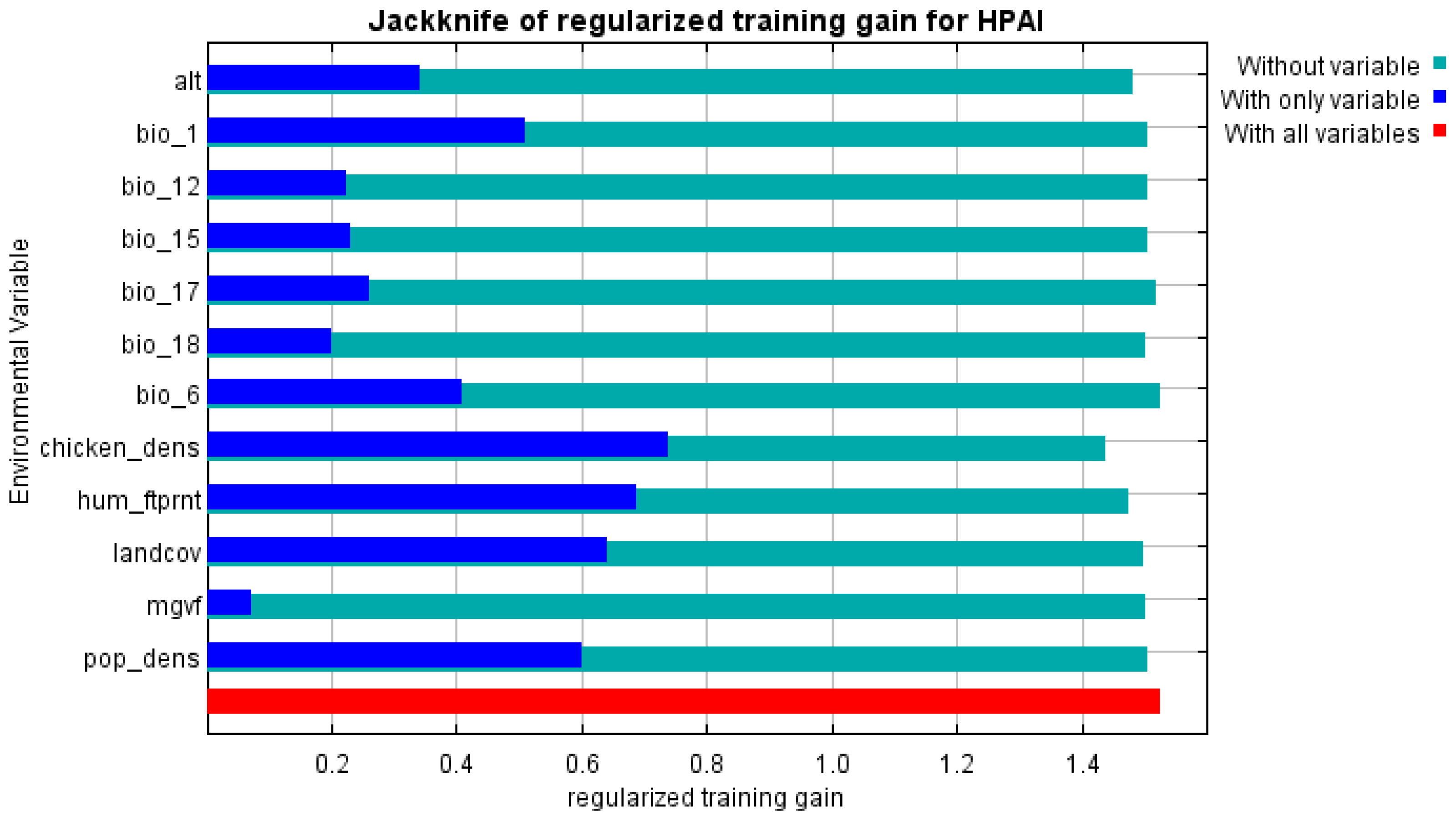

The Maxent model created with the training data provided a predictive suitability map (

Figure 2) and demonstrated good performance with a mean AUC of 0.93. Most contributing variables were chicken population density, human footprint index, and mean yearly air temperature (

Figure 3)

A resulting predicted suitability is presented in the map (

Figure 2) overlaid with training data.

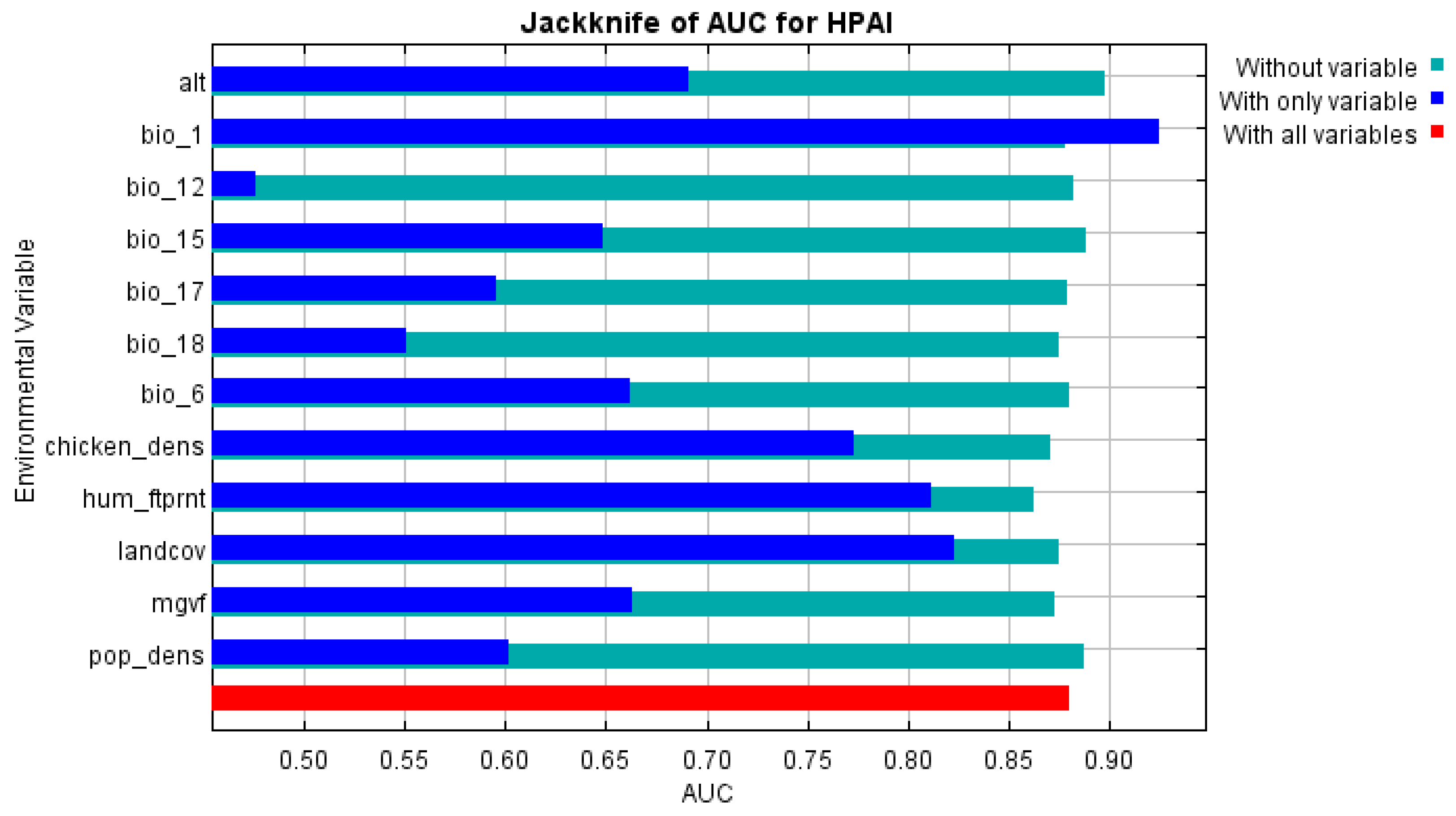

Nor surprisingly, being applied to outbreaks in Kazakhstan (test data), the model demonstrated a slightly lower AUC of 0.883 compared to the value reported for all the assessed countries. Relative contribution of variables showed an increased significance of bio_1 (mean yearly air temperature) and altitude, while keeping significance of previously revealed predictors.

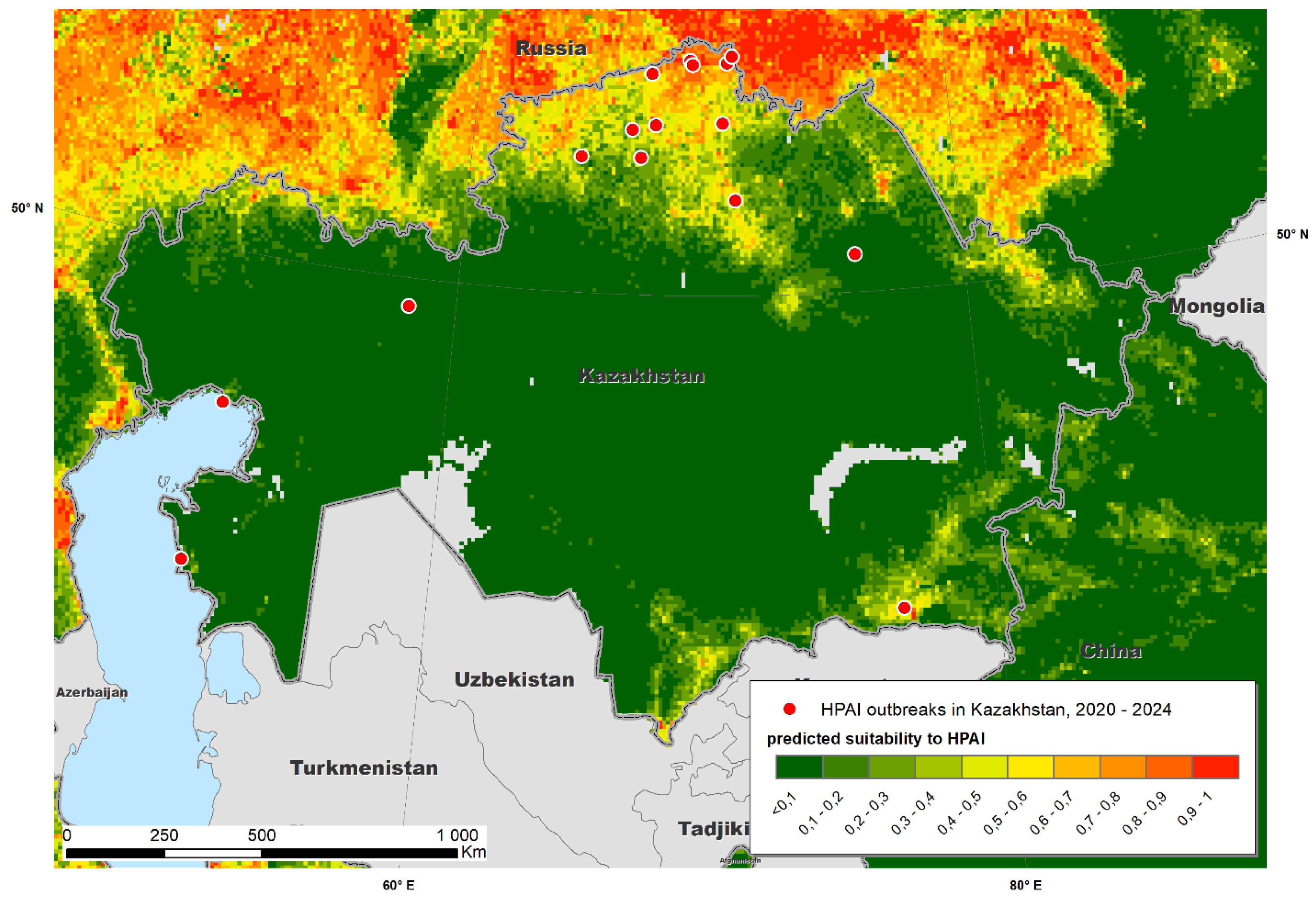

A map of predicted suitability for Kazakhstan overlaid with test data is presented in

Figure 4. The map suggests that most of HPAI outbreaks in Kazakhstan were recorded in areas predicted by Maxent as “suitable”, which confirms the adequateness of the model and underlines a possibility of the further improvement of the model by adjusting the set of environmental variables. Relative importance of variables per the results of Jackknife test is presented in

Figure 5. In addition to previously identified significant factors, mean annual temperature and maximum green vegetation fraction were found to influence the observed distribution of HPAI outbreaks in Kazakhstan.

The summary suitability against the reported number of outbreaks by country is presented in

Table 3 and plotted in

Figure 6. The regression model reveals a high significance of the summary suitability as a predictor of the number of outbreaks with p<0.001 and R2 = 0.75.

4. Discussion

The study here contributed to elucidate the most general patterns on environmental suitability for HPAI outbreaks in Kazakhstan. Human-related factors (such as human footprint index and chicken density) were more strongly associated with reported HPAI outbreaks than climate and landscape factors, such as annual mean air temperature, annual precipitation and altitude. The land cover demonstrated relatively low relation with HPAI outbreaks, with croplands, cropland/natural vegetation mosaic, urban/built-up and water areas been the most frequent categories for HPAI. For the most influential variable, namely, chicken density, a positive relation was found with suitability to HPAI, which indicates a naturally expected relation between presence of a highly dense susceptible population and disease. A similar dependency was found for the human footprint index. A stronger human impact indicates higher exposure to HPAI (presumably due to most intensive between-farm contact as well as increased probability of the disease detection). A similar pattern in terms of human footprint index was found by [27].

A comparison between the summary suitability (expressed as a sum of raster cells with suitability of >50%) by country, and the corresponding number of reported HPAI outbreaks 2020 – 2024 suggested that Kazakhstan generally follows the pattern for the rest of analyzed countries. Consequently, with the revealed associations, three highly suitable areas for HPAI were identified. Two of those three areas, located in the northern part of the country, along the Russian border, and in south-western regions, close to Kyrgyzstan and China, were likely associated with high poultry and human density, thus, suggesting a high risk for cases in domestic susceptible populations. The remaining area of elevated suitability was identified in the western region, close to the Caspian Sea.

The Caspian Sea is located on the migration routes of wild birds, and it is part of the Central Asian Flyway. This route covers vast areas from Siberia to South Asia, including the western regions of Kazakhstan. Migratory birds such as ducks, geese, swans, birds of prey and rare species such as pink flamingos actively follow the wetlands and coastal areas of the Caspian Sea for stopovers, nesting and wintering. Due to the diversity of ecosystems in the Caspian Basin, this region provides important resources for maintaining the biological diversity of migratory species. Of particular importance are the unique ecosystems of the Ural (Zhaiyk) River delta and the northern coast of the Caspian Sea, where vast wetlands are formed. These areas serve not only as transit points for millions of migratory birds, but also as concentration sites for rare, endangered species. Most importantly, the western regions of Kazakhstan (Atyrau, Mangistau and West Kazakhstan) are characterized by the active development of the poultry industry. Proximity of poultry farms to migration routes increases the likelihood of contact between domestic and wild birds, which increases the risk for transmission of infectious diseases, such as HPAI.

Interestingly, HPAI outbreaks reported in Kazakhstan were located in high risk predicted areas, suggesting that cases that may have not been identified by the current surveillance system are likely to have occurred on the same areas in which outbreaks were reported. This observation suggests that, even in the presence of under-reporting, affected regions were properly identified, facilitating the design and implementation of actions intended to contain disease spread.

An important limitation of this study is that the association of predictive variables could only be assessed with the presence of reported outbreaks, rather than true presence of the disease. For that reason, it is possible that the associations reported here could indicate the likelihood of identifying the disease, rather than the probability of disease occurrence. The inclusion of data from other countries in the region represented an attempt to mitigate the impact of such limitation, at least in part, by adding information from countries in which different surveillance strategies were implemented. Nevertheless, it is uncertain how effective this strategy may have been in adjusting for potential reporting bias. In summary, the results here contributed to identify three areas of high risk for HPAI cases in Kazakhstan, associated with the presence of wild and domestic birds. Development and implementation of a system intended to early detect the risk for incursions in those areas could help to anticipate the introduction of the disease into the country, selectively triggering active sampling and control activities, ultimately, contributing to prevent further dissemination of the disease in the country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SKA; methodology, FIK and AMP; resources, AZhA.; data curation, YYM, ASK, IIS, ABSh; writing—original draft preparation, AZhA; writing—review and editing, SKA and AMP; visualization, FIK; supervision, SKA; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan Grant No. AP23489183 “Epidemiology of avian influenza and development of preventive measures based on methods of quantitative epidemiology and information and communication technologies”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the present research (specifically, HPAI outbreaks location data and environmental layers) are publicly available, and their sources are listed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Capua, I.; Alexander, D.J. Avian Influenza and Newcastle Disease: A Field and Laboratory Manual. Avian Influ. Newcastle Dis. A F. Lab. Man. 2009, 1–186. [CrossRef]

- The World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). Avian Influenza. Available online at: https://www.woah.org/en/disease/avian-influenza/ [Accessed December 25, 2024].

- WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health. (n.d.). Terrestrial Manual Online Access. Available online at: https://www.oie.int/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-manual-online-access/ [Accessed December 25, 2024].

- World Health Organization. Avian Influenza A (H5N1) – Cambodia. Available online at: https://www.who.int/ru/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON445. [Accessed December 27, 2024].

- Assessment of Risk Associated with Recent Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Viruses Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/assessment-of-risk-associated-with-recent-influenza-a(h5n1)-clade-2.3.4.4b-viruses (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Amirgazin, A.; Shevtsov, A.; Karibayev, T.; Berdikulov, M.; Kozhakhmetova, T.; Syzdykova, L.; Ramankulov, Y.; Shustov, A. V. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus of the A/H5N8 Subtype, Clade 2.3.4.4b, Caused Outbreaks in Kazakhstan in 2020. PeerJ 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- FUJIMOTO, Y.; HAGA, T. Association between Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Outbreaks and Weather Conditions in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 86. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Hossain, M.E.; Amin, E.; Islam, S.; Islam, M.; Sayeed, M.A.; Hasan, M.M.; Miah, M.; Hassan, M.M.; Rahman, M.Z.; et al. Epidemiology and Phylodynamics of Multiple Clades of H5N1 Circulating in Domestic Duck Farms in Different Production Systems in Bangladesh. Front. public Heal. 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Adlhoch, C.; Fusaro, A.; Gonzales, J.L.; Kuiken, T.; Mirinavičiūtė, G.; Niqueux, É.; Ståhl, K.; Staubach, C.; Terregino, C.; Willgert, K.; et al. Avian Influenza Overview September–December 2023. EFSA J. 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- The World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). Available online at: https://wahis.woah.org/#/event-management [Accessed December 27, 2024].

- Xie, R.; Edwards, K.M.; Wille, M.; Wei, X.; Wong, S.S.; Zanin, M.; El-Shesheny, R.; Ducatez, M.; Poon, L.L.M.; Kayali, G.; et al. The Episodic Resurgence of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5 Virus. Nat. 2023 6227984 2023, 622, 810–817. [CrossRef]

- Dao, D.T.; Coleman, K.K.; Bui, V.N.; Bui, A.N.; Tran, L.H.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Than, S.; Pulscher, L.A.; Marushchak, L. V.; Robie, E.R.; et al. High Prevalence of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza: A Virus in Vietnam’s Live Bird Markets. Open forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Marchenko, V.Y.; Goncharova, N.I.; Gavrilova, E. V.; Maksyutov, R.A.; Ryzhikov, A.B. Overview of the Epizootiological Situation on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Russia in 2020. Probl. Part. Danger. Infect. 2021, 0, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Zhiltsova, M. V.; Akimova, T.P.; Varkentin, A. V.; Mitrofanova, M.N.; Mazneva, A. V.; Semakina, V.P.; Vystavkina, E.S. Global Avian Influenza Situation (2019–2022). Host Range Expansion Asevidence of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza Virus Evolution. Vet. Sci. Today 2023, 12, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- Ly, H. Recent Global Outbreaks of Highly Pathogenic and Low-Pathogenicity Avian Influenza A Virus Infections. Virulence 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Islam, S.; Flora, M.S.; Amin, E.; Woodard, K.; Webb, A.; Webster, R.G.; Webby, R.J.; Ducatez, M.F.; Hassan, M.M.; et al. Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Avian Influenza A Viruses H5N1 and H3N8 Subtypes in Poultry Farms and Live Bird Markets in Bangladesh. Sci. Reports 2023 131 2023, 13, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Burashev, Y.; Strochkov, V.; Sultankulova, K.; Orynbayev, M.; Kassenov, M.; Kozhabergenov, N.; Shorayeva, K.; Sadikaliyeva, S.; Issabek, A.; Almezhanova, M.; et al. Near-Complete Genome Sequence of an H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus Strain Isolated from a Swan in Southwest Kazakhstan in 2006. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Issabek, A.; Burashev, Y.; Chervyakova, O.; Orynbayev, M.; Kydyrbayev, Z.; Kassenov, M.; Zakarya, K.; Sultankulova, K. Complete Genome Sequence of the Highly Pathogenic Strain A/Domestic Goose/Pavlodar/1/05 (H5N1) of the Avian Influenza Virus, Isolated in Kazakhstan in 2005. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- The World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH). Available online at: https://rr-europe.woah.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/8_kazakhstan_ai-nd_ru.pdf (in Russian) [Accessed December 27, 2024].

- Baikara, B.; Seidallina, A.; Baimakhanova, B.; Kasymbekov, Y.; Sabyrzhan, T.; Daulbaeva, K.; Nuralibekov, S.; Khan, Y.; Karamendin, K.; Sultanov, A.; et al. Genome Sequence of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus A/Chicken/North Kazakhstan/184/2020 (H5N8). Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Bopi A.K., Omarova Z.D., A. R.R., Tulendibaev A.B., Argimbayeva T.U., Alibekova D.A., Aubakir N.A., et al. Monitoring of highly pathogenic avian influenza in Kazakhstan. Biosafety and Biotechnology. 2022;(10):24-30. (in Russian). [CrossRef]

- Potential Risk of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Spreading through Wild Water Bird Migration Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/d6185856-dae8-4e8a-a345-1eb34e591a36 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Anonymous. Kazakhstan's wetlands are of international importance. Available online at: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=30024524&pos=4; -135#pos=4;-135/ [Accessed December 30, 2024]. (in Russian).

- Sultankulova, K.T.; Argimbayeva, T.U.; Aubakir, N.A.; Bopi, A.; Omarova, Z.D.; Melisbek, A.M.; Karamendin, K.; Kydyrmanov, A.; Chervyakova, O. V.; Kerimbayev, A.A.; et al. Reassortants of the Highly Pathogenic Influenza Virus A/H5N1 Causing Mass Swan Mortality in Kazakhstan from 2023 to 2024. Anim. an open access J. from MDPI 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, Y.P.; An, Q.; Gao, X.; Wang, H. Bin Risk Factors Contributing to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N6 in China, 2014–2021: Based on a MaxEnt Model. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2023, 2023, 6449392. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum Entropy Modeling of Species Geographic Distributions. Ecol. Modell. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Alkhamis, M.; Hijmans, R.J.; Al-Enezi, A.; Martínez-López, B.; Peres, A.M. The Use of Spatial and Spatiotemporal Modeling for Surveillance of H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Poultry in the Middle East. Avian Dis. 2016, 60, 146–155. [CrossRef]

- Belkhiria, J.; Hijmans, R.J.; Boyce, W.; Crossley, B.M.; Martínez-López, B. Identification of High Risk Areas for Avian Influenza Outbreaks in California Using Disease Distribution Models. PLoS One 2018, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kyuyoung, L.; Yu, D.; Martínez-López, B.; Belkhiria, J.; Kang, S.; Yoon, H.; Hong, S.-K.; LEE, I.; Son, H.-M.; Lee, K. Identification of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Suitable Areas for Wild Birds Using Species Distribution Models in South Korea. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Phillips, S.J.; Hastie, T.; Dudík, M.; Chee, Y.E.; Yates, C.J. A Statistical Explanation of MaxEnt for Ecologists. Divers. Distrib. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Steven J. Phillips, Miroslav Dudík, Robert E. Schapire. [Internet] Maxent software for modeling species niches and distributions (Version 3.4.1). Available from url: http://biodiversityinformatics.amnh.org/open_source/maxent/. Accessed on 2025-1-15.

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S. 2002. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).