1. Introduction

The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is characterized by a distinct ecological gradient, with mean annual precipitation decreasing from east to west (150–400 mm) and vegetation transitioning from meadow steppes in the east to desert steppes in the west [

1,

2,

3]. This arid and semi-arid environment provides suitable conditions for grassland pests, while ongoing grassland degradation and desertification further disrupt ecological balance and weaken natural predator control, contributing to frequent pest outbreaks [

4,

5].

The

Galeruca daurica belongs to the order Coleoptera, family Chrysomelidae, and subfamily Galerucinae Its larvae primarily feed on the leaves of Allium species (Liliaceae), such as Mongolian onion (Allium mongolicum),many-rooted onion (Allium polyrhizum), and wild leek (Allium ramosum), and may severely damage roots in extreme cases [

6]. This pest is native to Mongolia, Russia, North Korea, and South Korea, and is widely distributed in China’s Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Gansu [

7].In recent years, influenced by global warming and grassland degradation, Galeruca daurica experienced its first large-scale outbreak in the grasslands of Inner Mongolia in 2019, emerging as a major pastoral pest [

8]. Affected regions include Hulunbuir, Xing’an League, Xilingol League, and Ulanqab [

8]. Thus, projecting its potential distribution under future climate scenarios is vital for ecological risk early-warning and pest management.

There is a close relationship between species distribution and the environment. Climatic factors have a great influence on species distribution [

9].Elucidating the mechanisms of interaction between organisms and their living environment is an essential prerequisite for understanding the ecological adaptive characteristics of species and the patterns of their geographical distribution [

10].The spatial distribution pattern of species is the result of the combined effects of bioclimatic factors, community succession processes, and human disturbance activities. These elements together shape the ecological suitability of habitats and directly affect the species’ potential for continued survival [

11].With the intensification of global warming, many plant and animal species are gradually migrating to higher latitudes or altitudes [

12,

13]. In response to the impacts of climate change, numerous species are continuously shifting toward habitats with more suitable climatic conditions, leading to dynamic changes in their geographical distribution ranges [

14].Besides climate, topographic factors (e.g., elevational gradients) and soil properties (including physicochemical characteristics) also influence the geographical distribution patterns of insects. Altitudinal variation acts as an ecological barrier by restricting species’ dispersal capacity, while soil pH, organic matter content, and porosity directly affect oviposition site selection, larval development, and microbial symbiosis in insects. Furthermore, human activities such as urbanization and deforestation can significantly alter insect habitats, leading to shifts in their distribution ranges [

15]. The combined effects of these factors drive the formation of species’ geographical distribution patterns and their responses to environmental changes.

The Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) model is widely recognized for its robust predictive performance in species distribution modeling, particularly with limited occurrence data [

16,

17]. Its principle involves estimating the probability of species occurrence by maximizing entropy subject to environmental constraints derived from known presence locations [

18]. In this study, the model was applied to integrate multi-dimensional environmental variables—including climatic, topographic, and notably soil factors—to enhance prediction accuracy. Furthermore, comparative analyses under multiple climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5) were conducted to project spatiotemporal shifts in habitat suitability [

19,

20]. This approach offers improved mechanistic insight into the species’ ecological niche and potential range dynamics [

21].

This study collected and screened geographical distribution data of Galeruca daurica, combined with relevant environmental variables, and employed the Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) model to predict its potential suitable habitats in Inner Mongolia under current and future climate conditions. The research further examined the impact of contemporary and future climate change on its distribution, aiming to address the following questions: (1) the potential suitable habitat distribution of G. daurica in Inner Mongolia under current climate conditions; (2) changes in its potential suitable habitats under future climate scenarios; and (3) the relationship between the beetle’s potential geographical distribution and environmental factors in Inner Mongolia. The findings provide a theoretical foundation and scientific support for ecological early warning and pest control strategies in the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Species Occurrence Data and Preprocessing

Occurrence records of Galeruca daurica were compiled from field surveys conducted during June–August of 2022 and 2023 in Inner Mongolia. To mitigate potential model overfitting caused by spatial autocorrelation, the initial 148 occurrence points were processed using ENM Tools v1.4. A total of 26 spatially redundant points were removed, resulting in 122 unique and spatially independent records retained for model calibration.

2.2. Environmental Variables

A total of 36 environmental variables were initially considered, including:

19 bioclimatic variables (current and future) from the WorldClim database under three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5) for the mid-century (2041–2060) and late-century (2061–2080) periods,

3 topographic variables (elevation, slope, and aspect), and

14 soil variables obtained from the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD).

To reduce multicollinearity among predictors and improve model parsimony, pairwise Pearson correlations were calculated. If the absolute correlation coefficient between two variables exceeded 0.8, the variable with the lower contribution to the model was excluded. Additionally, only variables with contribution rates ≥0.5% were retained [

22,

23,

24]. Following this two-step screening, 12 environmental predictors were selected for final model construction.

2.3. Model Construction and Evaluation

MaxEnt v3.4.4 was employed to model the current and future distributions of

G. daurica. The 122 occurrence records and 12 selected environmental variables were input into the model [

25,

26]. Data were randomly partitioned: 75% for training and 25% for testing. The model was set to run for a maximum of 10,000 iterations with 10 replicates. Output was generated in “logistic” format with default settings [

27,

28].

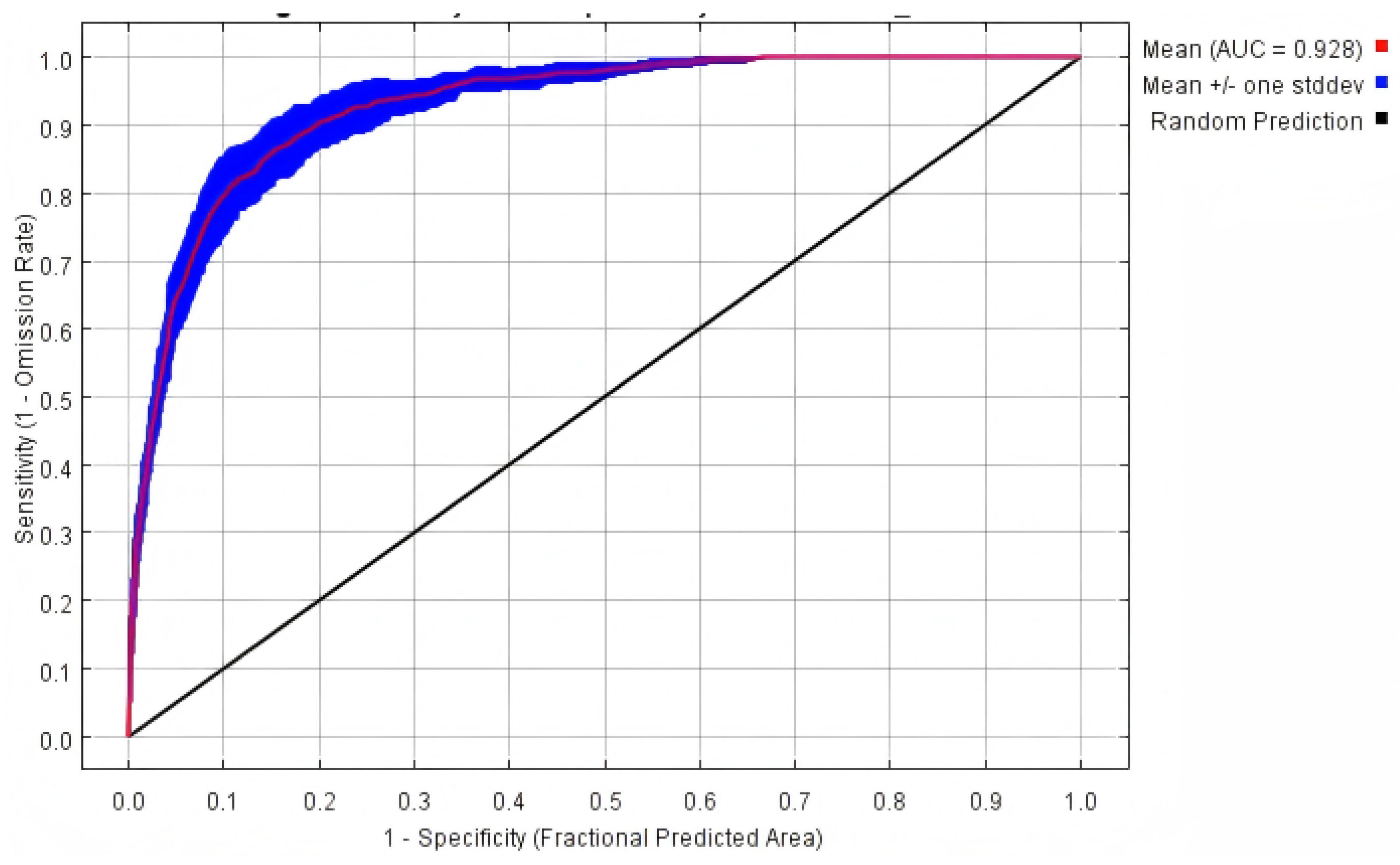

Model performance was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). AUC values >0.9 indicate excellent predictive performance [

29,

30]. Variable importance was assessed using the built-in Jackknife test and response curves.

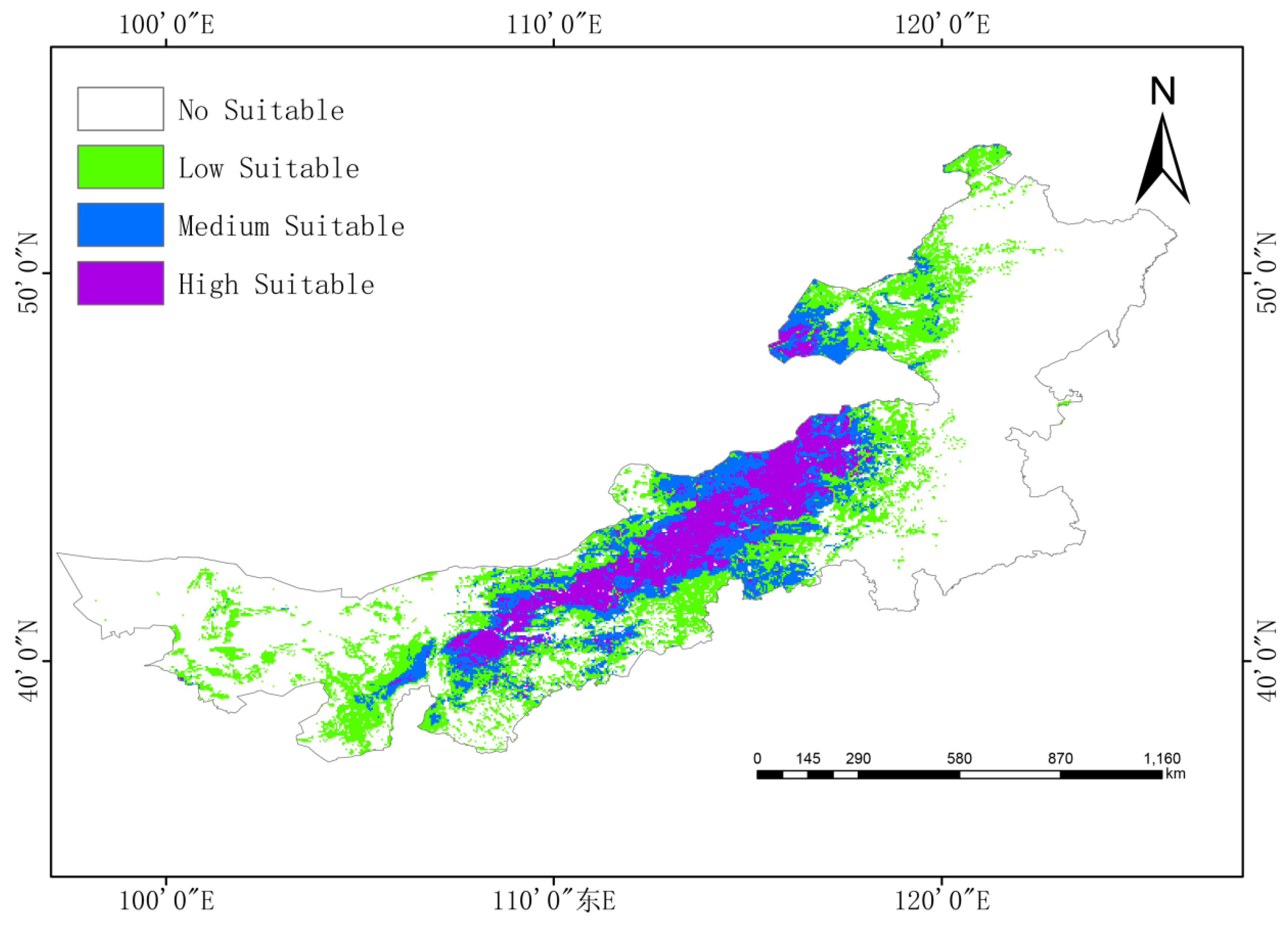

2.4. Habitat Suitability Classification

Habitat suitability was classified using the Jenks natural breaks method in ArcGIS. Predicted suitability values (P) were categorized as:

Non-suitable (P < 0.1),

Low suitability (0.1 ≤ P ≤ 0.27),

Medium suitability (0.27 < P ≤ 0.48), and

High suitability (P > 0.48).

Each habitat class was visualized, and the area of each suitability zone was quantified using the Reclassification and Zonal Statistics tools [

31,

32].

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance

The MaxEnt model demonstrated robust predictive power under both current and future climate scenarios. All models achieved AUC values exceeding 0.90 (

Table 1,

Figure 1), indicating high model reliability and accuracy in predicting

G. daurica’s habitat suitability.

3.2. Key Environmental Drivers

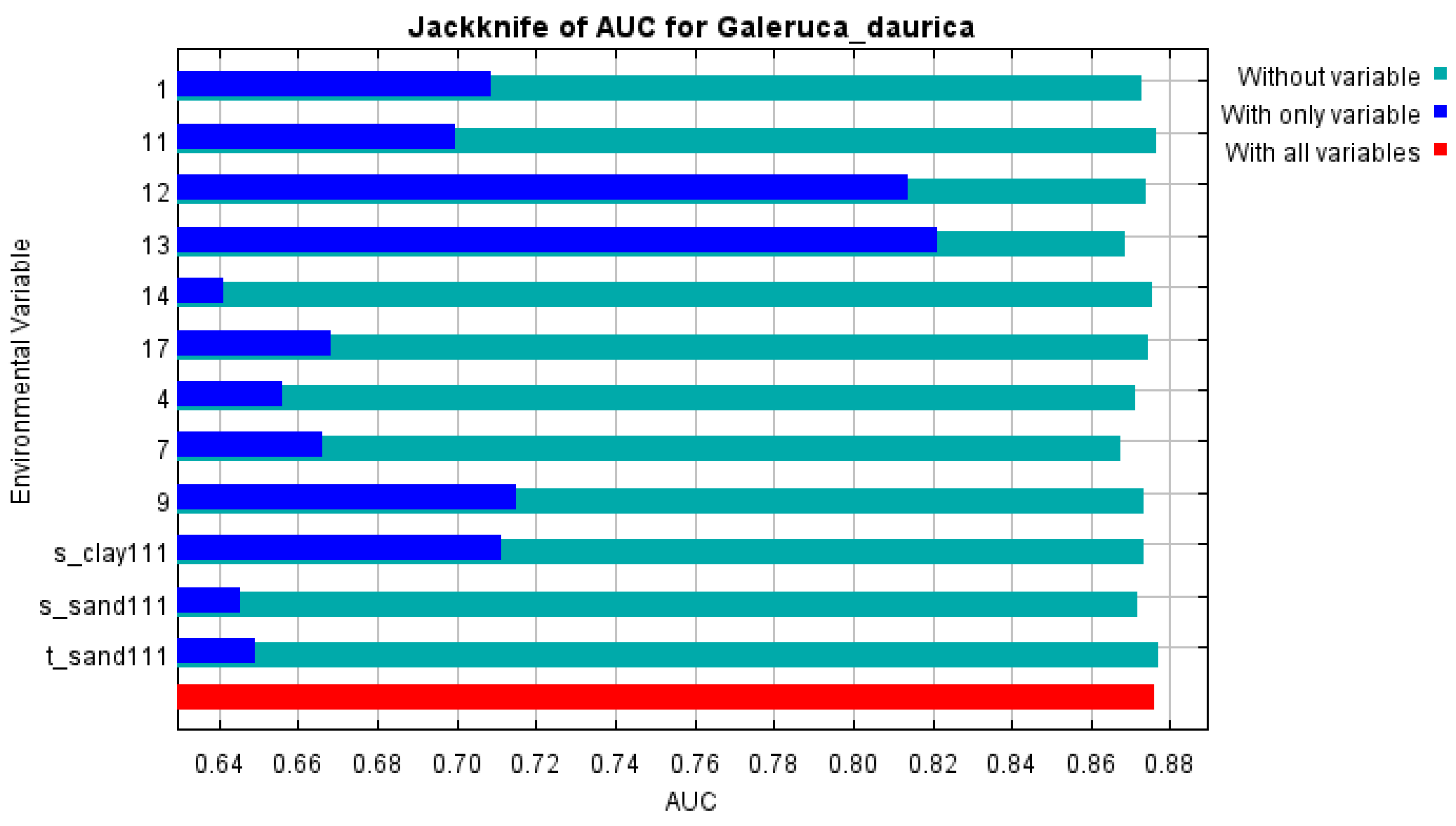

Among the 12 environmental predictors, the three most influential were:

Precipitation of the wettest month (bio13) – 39.6% contribution,

Annual precipitation (bio12) – 24.0%,

Annual temperature range (bio7) – 8.2%,

These top predictors contributed a cumulative 71.8% to the model. Other relevant variables included subsoil clay content, sand content, mean annual temperature, and precipitation of the driest quarter. Jackknife analyses further confirmed the critical role of bio13 and bio12, both achieving AUC values >0.8 when used in isolation (

Figure 2).

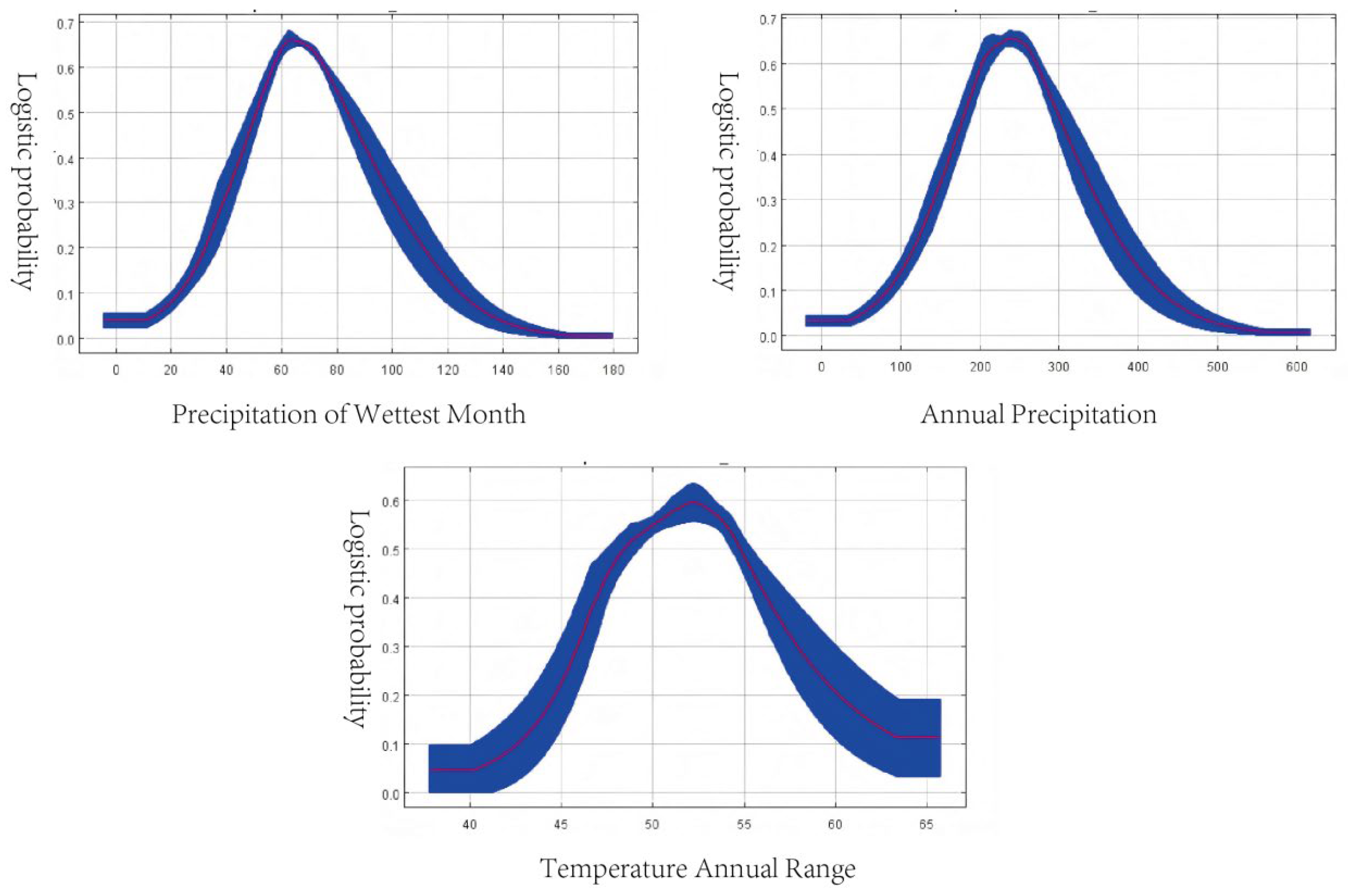

3.3. Response Curve Analysis

Response curves (

Figure 3) indicated the optimal ecological ranges for G. daurica occurrence:

Precipitation of the wettest month: 51–82 mm, with maximum presence probability (0.66) at 62 mm.

Annual precipitation: 180–300 mm, optimal at 240 mm.

Annual temperature range: 48.5–54.7°C, optimal at 52°C.

3.4. Current Potential Distribution

Under current climate conditions, G. daurica’s suitable habitat in Inner Mongolia encompasses approximately 531,300 km2, or 44.9% of the region:

High suitability: 117,500 km2 (9.9%),

Moderate suitability: 149,200 km2 (12.6%),

Low suitability: 264,600 km2 (22.4%).

High-suitability areas are concentrated in the central-western region, notably the Ordos Plateau, Hetao Plain, and parts of Xilingol League and Ulanqab (

Figure 4).

3.5. Future Habitat Shifts

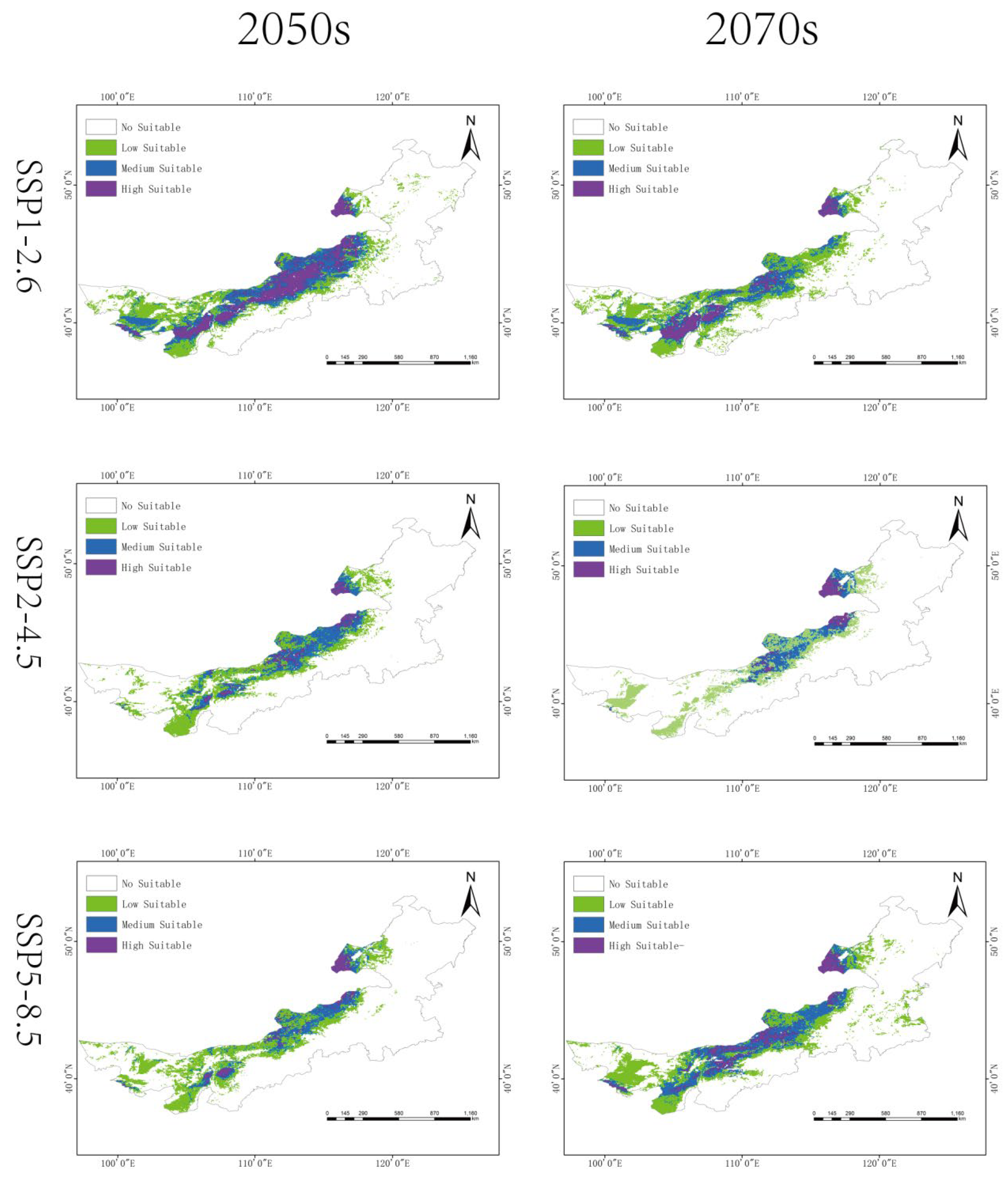

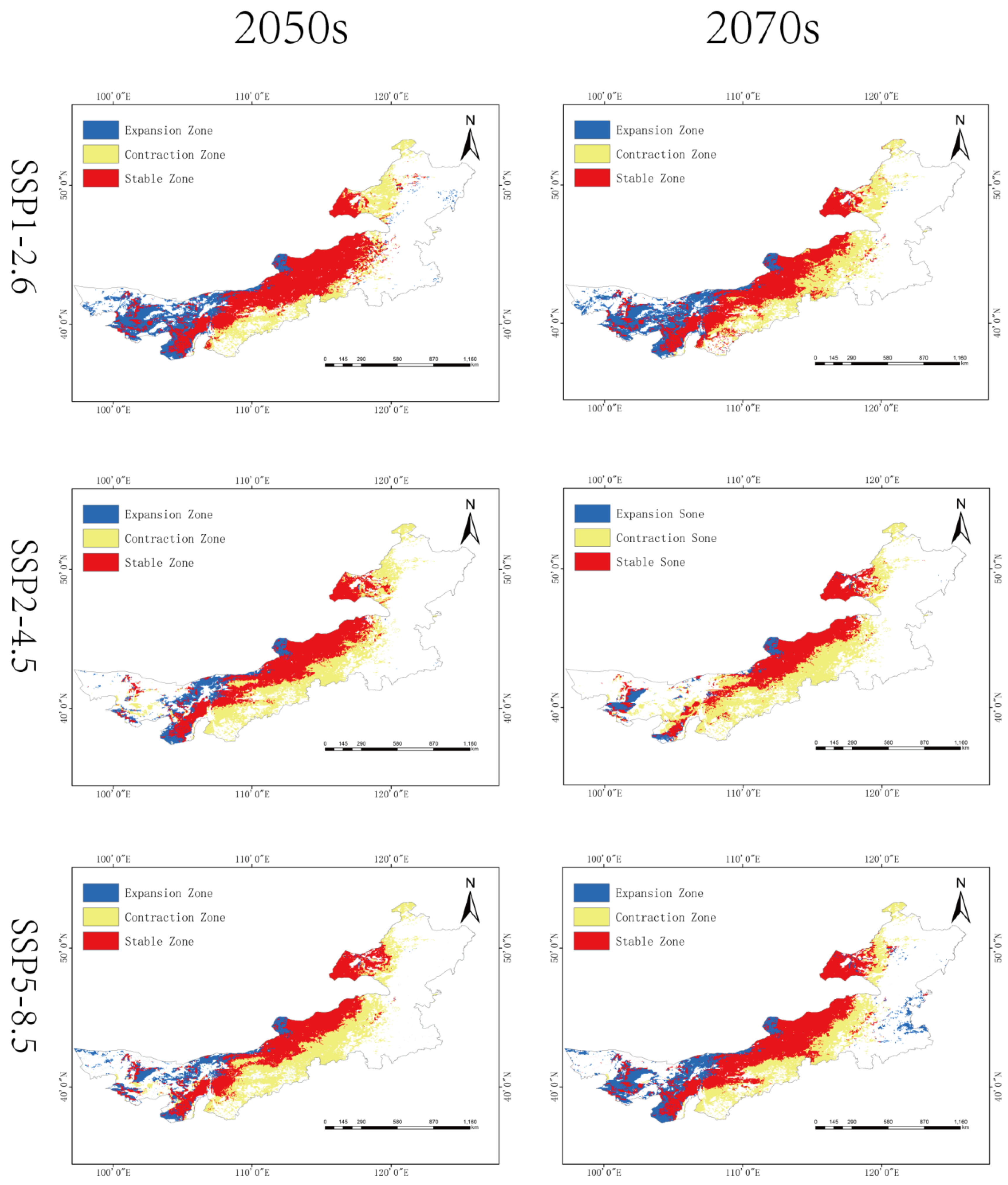

Climate projections suggest notable spatiotemporal changes in habitat suitability:

SSP1-2.6: slight short-term expansion in the 2050s (835,100 km2), followed by a decrease by the 2070s (782,300 km2).

SSP2-4.5: steady contraction to 486,300 km2 by 2070s (23.56% of Inner Mongolia).

SSP5-8.5: an initial decline followed by moderate rebound (801,000 km2 in the 2070s).

Overall, a northward shift in high-suitability areas is observed under all scenarios, with fragmentation of medium- and low-suitability zones (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6,

Table 2).

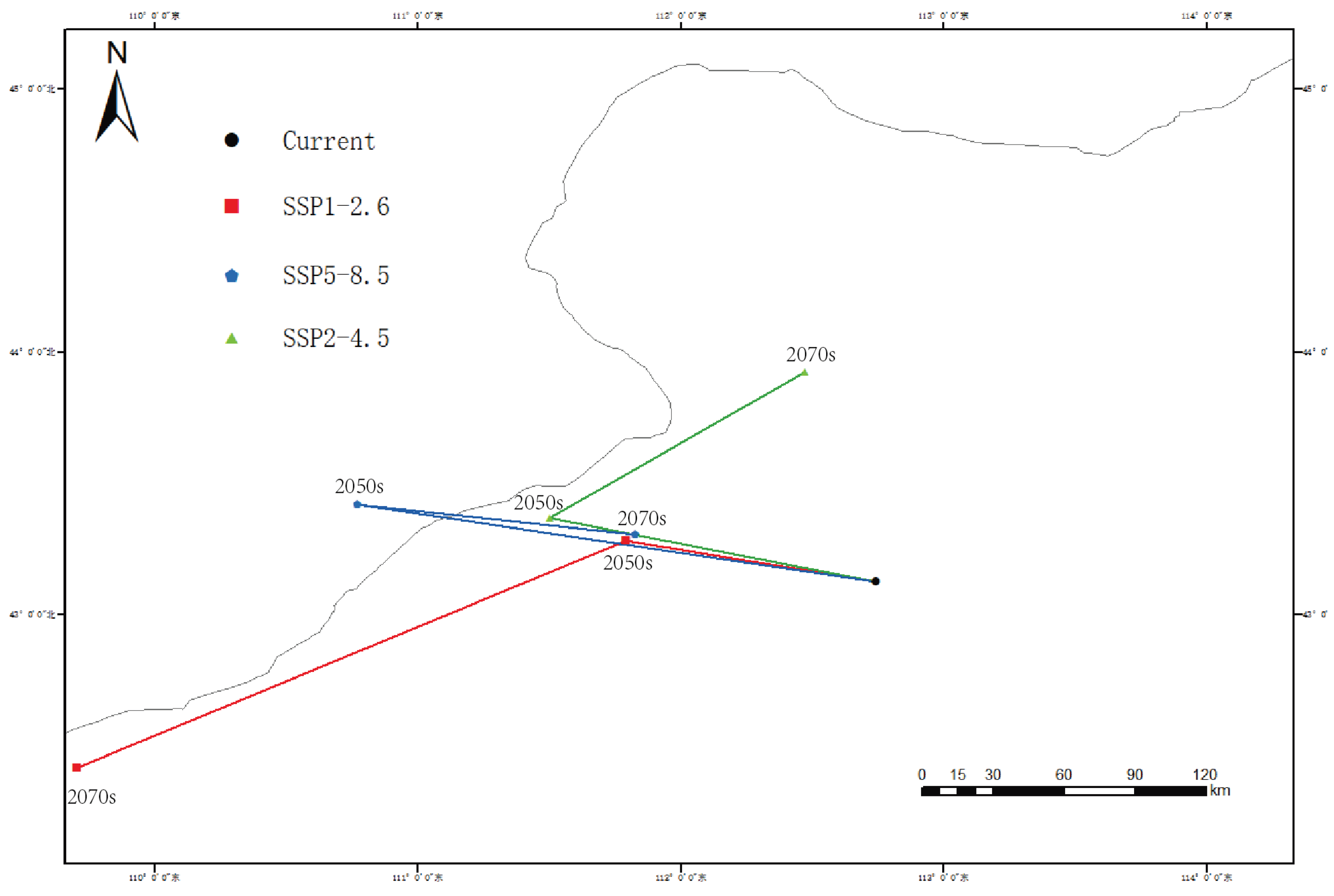

3.6. Centroid Migration

The current centroid of

G. daurica’s suitable habitat is located in Sunite Right Banner, Xilingol League (112.7390°E, 43.1234°N). Under future climate scenarios, this centroid is projected to shift northward, with the most pronounced movement (183.6 km) under SSP1-2.6 by the 2050s (

Figure 7,

Table 3).

4. Discussion

Insects, as poikilothermic organisms, have body temperatures that are largely dictated by ambient environmental conditions. Consequently,

temperature and moisture availability are key climatic determinants of their development, reproduction, behavior, and survival [

33]. Water not only supports basic physiological functions such as metabolism and excretion but also plays a central role in hormone transport and signal transduction [

34]. These physiological dependencies render insects highly sensitive to climatic fluctuations [

35]. The combined effects of temperature and precipitation operate via both direct (physiological) and indirect (habitat structural) mechanisms, ultimately shaping habitat suitability and determining the spatial distribution of insect populations [

36,

37,

38].

Our results confirm that

temperature and precipitation are the most critical environmental variables governing the distribution of

Galeruca daurica. Among the 12 environmental predictors used in the MaxEnt model, precipitation of the wettest month (bio13), annual precipitation (bio12), and annual temperature range (bio7) together accounted for 71.8% of the cumulative contribution to habitat suitability. These findings are consistent with previous studies and highlight

G. daurica’s strong ecological affinity for

semi-arid to arid climates [39]. Response curve analysis further revealed that the beetle favors environments with lower precipitation levels, which likely reduce physiological stress associated with excessive humidity during its larval and pupal stages. Additionally, the suitable annual temperature range for the beetle’s development was estimated at 48.5–54.7°C (bio7), a range known to influence key life-history traits such as larval development rate and diapause termination.

Climatic variables also exert

indirect control over beetle distribution by influencing the phenology, nutritional quality, and spatial availability of host plants, primarily

Allium mongolicum and related species. Previous studies have shown that temperature and precipitation changes affect host plant biomass and chemistry, which in turn modulate herbivore fitness, survival, and dispersal capacity [

40,

41,

42]. Therefore, shifts in the climatic niche of

G. daurica may reflect both direct thermohydric limitations and indirect host-plant-mediated constraints.

Under current climate conditions, G. daurica’s high-suitability habitats are concentrated in the temperate arid and semi-arid belt between 110°E and 120°E. These regions are characterized by abundant solar radiation, sandy soils, sparse vegetation structure, and low annual precipitation—conditions that support the species’ xerophytic life-history strategy. Central Inner Mongolia, including parts of the Ordos Plateau and Xilingol League, hosts contiguous high-suitability zones due to the co-occurrence of favorable abiotic factors and abundant host plant resources. In contrast, regions west of 100°E are constrained by higher soil clay content and slightly increased precipitation, while high-latitude zones (near 50°N) remain largely unsuitable due to thermal limitations.

Climate change projections reveal a general contraction of suitable habitat area for Galeruca daurica, particularly under moderate- to high-emission scenarios (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5). This contraction is driven by both climatic mechanisms and exacerbated by current grassland utilization patterns. Specifically, the following processes interact with regional grazing intensity and degradation-recovery dynamics:

Increased precipitation: Projected rises in precipitation exceed the species’ optimal hydrological thresholds, especially during the wettest month, reducing habitat suitability. This effect may be intensified in overgrazed or degraded grasslands, where reduced vegetation cover and compromised soil structure alter water infiltration and retention, further disrupting the microhabitat conditions required by G. daurica.

(2) Elevated temperatures: Warmer conditions disrupt critical physiological processes such as diapause termination, which depends on sufficient cold accumulation. In degraded grasslands with reduced plant biomass and lower litter cover, thermal buffering capacity is diminished, potentially amplifying temperature stress and impairing embryonic development. Consequently, range persistence may be further limited in areas subject to high grazing pressure and slow ecological recovery.

These findings highlight the importance of integrating grassland management practices—such as restoring degraded areas and regulating grazing intensity—into climate adaptation strategies to mitigate future habitat loss and suppress potential pest outbreaks.

Geographically, our analysis suggests a shift characterized by northward migration and inland westward expansion, with contraction in the southern and eastern regions. Notably, western regions such as the Alxa Plateau and western Bayannur—traditionally arid—may become newly suitable habitats due to intensified aridification under future climate regimes. This finding is consistent with ecological niche theory, which predicts poleward or altitudinal range shifts under warming scenarios. Conversely, the eastern belt, despite historically supporting large populations, may experience significant suitability loss due to altered precipitation regimes and intensified land-use activities.

Under all SSP scenarios, the centroid of suitable habitats shifts toward higher latitudes, supporting the hypothesis of climate-driven redistribution. Particularly under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, habitat fragmentation and reduced connectivity may pose additional risks to population persistence. These findings underscore the necessity for region-specific pest risk assessments and adaptive management plans.

It is recommended that ecological monitoring and early-warning systems be enhanced in newly emerging high-risk areas, particularly in western Inner Mongolia. Simultaneously, ongoing habitat degradation and potential pest collapse in eastern regions require sustained attention to avoid ecosystem-level instability due to secondary pest outbreaks or trophic imbalances.

5. Conclusions

This study employed the MaxEnt modeling approach to assess the current and future potential distribution of Galeruca daurica in Inner Mongolia. The results demonstrate that the beetle’s suitable habitats are primarily influenced by precipitation of the wettest month, annual precipitation, and annual temperature range, highlighting its strong sensitivity to climate variability. Presently, approximately 44.9% of Inner Mongolia is classified as suitable habitat, with the most favorable zones located in the arid and semi-arid landscapes of the central and western regions.

Under future climate scenarios, particularly SSP2-4.5, the total area of suitable habitats is projected to decline significantly—to 23.56% by the 2070s—accompanied by a consistent northward shift in habitat centroid. These spatial trends indicate that G. daurica’s future distribution will be increasingly constrained by rising temperatures and altered precipitation regimes. Such changes may further disrupt the beetle’s host plant interactions and physiological performance, ultimately reshaping pest dynamics at the regional scale.

This study provides critical scientific evidence to support ecological risk forecasting, pest management planning, and policy formulation under climate change. However, the modeling framework was limited to abiotic predictors (climate, soil, and topography) and did not account for biotic interactions (e.g., predator-prey dynamics, plant-insect feedbacks) or anthropogenic disturbances (e.g., grazing, land use change). Future research should integrate these dimensions to improve model realism and enhance predictive accuracy for sustainable pest management in grassland ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1. Lists the 34 environmental variables used in the modeling process. Table S2. The Pearson correlation coefficient between environmental factors and Galeruca daurica. Table S3: Suitable environmental variable ranges for the potential distribution of G. daurica. Table S4. Percentage contribution and ranking of environment variables in Maxent model. Table S5. Area of potential suitable habitat in different periods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization,X.-S.B.; methodology, T.-Y.X. and R.M.; software, T.-Y.X.; validation, T.-Y.X. and X.-S.B.; formal analysis, T.-Y.X.; investigation, T.-Y.X.; resources, X.-S.B.; data curation, T.-Y.X.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-Y.X.; writing—review and editing, X.-S.B.,T.-Y.X. and R.M.; visualization, T.-Y.X.; supervision, X.-S.B. and R.M.; project administration, X.-S.B.; funding acquisition, X.-S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32460123).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

I can provide all raw data from the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bu H, Wulan Tuya, Siqin Chaoketu, Han Shumin, Gao Suriguga, Wu Xiuquan: Response of vegetation cover change to meteorological drought in Inner Mongolia from 1982 to 2099. Journal of Northwest Forestry University 2023, 38:1-9.

- Chen X, Yan Z, Liu Q, Li R, Zhang S: Spatiotemporal characteristics of drought in Inner Mongolia based on optimized remote-sensing drought indices in GEE. Arid Land Geography 2023, in press, 1-12.

- Zhao S, Zhou Q, Wang W, Wu Y: Dry-wet climate characteristics in Inner Mongolia based on the SPI index. Journal of China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research 2022, 20:10-19.

- Guo X, Tong S, Bao Y, Ren J: Spatiotemporal drought trends in Inner Mongolia over the past 55 years based on SPEI. Geomatics World 2021, 28:42-48+79.

- Li H, Ma L, Liu T, Liang L: Spatiotemporal drought variation in Inner Mongolia based on the standardized precipitation index. Hydrology 2018, 38:47-51+90.

- Hao X, Zhou X, Pang B, Zhang Z, Bao X: Morphological and biological characteristics of Galeruca daurica. Acta Agrestia Sinica 2015, 23:1106-1108.

- Yang X, Huang D, Ge S, Bai M, Zhang R: A million mu of grassland in Inner Mongolia damaged by an outbreak of Galeruca daurica. Entomological Knowledge 2010, 47:812.

- Hao X: Studies on the life history and occurrence pattern of Galeruca daurica. Master thesis. 2014.

- Booth, T.H.; Nix, H.A.; Busby, J.R.; Hutchinson, M.F.l Franklin, J. Bioclim: The first species distribution modelling package, its early applications and relevance to most current MaxEnt studies. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 20, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Denan, N.; Zaki, W.M.W.; Norhisham, A.R.; Sanusi, R.; Nasir, D.M.; Nobilly, F.; Ashton-Butt, A.; Lechner, A.M.; Azhar, B. Predation of potential insect pests in oil palm plantations, rubber tree plantations, and fruit orchards. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 10, 654–661. [CrossRef]

- Lux, J.; Xie, Z.; Sun, X.; Wu, D.; Scheu, S. Changes in microbial community structure and functioning with elevation are linked to local soil characteristics as well as climatic variables. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9632. [CrossRef]

- Pauli, H.; Gottfried, M.; Dullinger, S.; Abdaladze, O.; Akhalkatsi, M.; Alonso, J.L.B.; Coldea, G.; Dick, J.; Erschbamer, B.; Calzado, R.F.; et al. Recent Plant Diversity Changes on Europe’s Mountain Summits. Science 2012, 336, 353–355. [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D. Rapid Range Shifts of Species Associated with High Levels of Climate Warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024–1026. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Assessment of impact of climate change on Rhododendrons in Sikkim Himalayas using Maxent modelling: limitations and challenges. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 1251–1266. [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.P.; Gallardo, B.; Terblanche, J.S. A global assessment of climatic niche shifts and human influence in insect invasions. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 679–689. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, D.; Liao, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhuo, Z. Predicting the Current and Future Distributions of Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande) Based on the MaxEnt Species Distribution Model. Insects 2023, 14, 458. [CrossRef]

- Elango, A.; Raju, H.K.; Shriram, A.N.; Kumar, A.; Rahi, M. Predicting ixodid tick distribution in Tamil Nadu domestic mammals using ensemble species distribution models. Ecol. Process. 2025, 14, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Harte J, Umemura K, Brush M: DynaMETE: a hybrid MaxEnt-plus-mechanism theory of dynamic macroecology. Ecology Letters 2021, 24:935-949.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Gao, H.; Qi, Q.; He, W.; Li, J.; Yao, S.; Li, W. Ecological suitability distribution of hop based on MaxEnt modeling. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Ali, H.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wei, X.; Zhuo, Z. Impact of climate change on the distribution of Isaria cicadaeMiquel in China: predictions based on the MaxEnt model. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1509882. [CrossRef]

- Kilak, S.H.; Alavi, S.J.; Esmailzadeh, O. Spatial resolution matters: unveiling the role of environmental predictors in English yew (Taxus bacata L.) distribution using MaxEnt modeling. Earth Sci. Informatics 2025, 18, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Fabritius, H.; Jokinen, A.; Cabeza, M. Metapopulation perspective to institutional fit: maintenance of dynamic habitat networks. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Lu, Z.; Rohani, E.R.; Ou, J.; Tong, X.; Han, R. Current and future distribution of Forsythia suspensa in China under climate change adopting the MaxEnt model. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1394799. [CrossRef]

- Zhu L, Chen G, Li H, Zheng R: Habitat suitability of Andrias davidianus in Zhejiang Province based on Maxent modeling. Life Science Research 2023, in press, 1-12.

- Dou Q, Chen C, Zeng T, Longzhu D, Miao Q, Sun F, Cai R, Chen X, Suonang J: Predicting habitat suitability of important medicinal plants of Gentianaceae on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau with an optimized MaxEnt model. Acta Agrestia Sinica 2023, in press, 1-13.

- Yan Z, Shao M, Wang J: Prediction of suitable wintering habitat and key factors influencing population distribution of the Common Crane in China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2025, 36:578-586.

- Roshani; Rahaman, H.; Masroor, M.; Sajjad, H.; Saha, T.K. Assessment of Habitat Suitability and Potential Corridors for Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) in Valmiki Tiger Reserve, India, Using MaxEnt Model and Least-Cost Modeling Approach. Environ. Model. Assess. 2024, 29, 405–422. [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Xiang, J.; Li, D.; Liu, X. Prediction of Potential Suitable Distribution Areas of Quasipaa spinosa in China Based on MaxEnt Optimization Model. Biology 2023, 12, 366. [CrossRef]

- Liao J, Yi Z, Li S, Xiao L: Potential distribution of Miscanthus bidentatus in different periods based on Maxent modeling. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2020, 40:8297-8305.

- Wang Y, Xie B, Wan F, Xiao Q, Dai L: Application of ROC curve analysis in evaluating invasive species distribution models. Biodiversity Science 2007, 15:365-372.

- Zhao J, Lancuo Z, Wang W, Wang H, Wang W, Shen J: MaxEnt-based analysis of highland barley suitability responses to climate change on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture 2024, 32:1626-1638.

- Liao J, Li Y, Zhang S, Yang Y, Xiong C, Xiao S, Wang X, Wang Z, Guo Y: Potential habitat assessment and niche characterization of Tachypleus tridentatus and Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda in China using MaxEnt modeling. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica 2025, 56:175-185.

- Pan F, Chen M, Xiao T, Ji X, Xie S: Research progress on the effects of variable temperature on insect growth, development and reproduction. Journal of Environmental Entomology 2014, 36:240-246.

- Chang X, Gao H, Chen F, Zhai B: Effects of environmental humidity and rainfall on insects. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2008, 27:619-625.

- Ojija, F.; Mng’oNg’o, M.; Aloo, B.N.; Mayengo, G.; Helikumi, M. Effect of global climate change on insect populations, distribution, and its dynamics. J. Asia-Pacific Èntomol. 2025, 28. [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, M.; Iijima, H. Precipitation on abscised leaves modulates leaf-mining beetle (Trachys yanoi) survivorship and population dynamics. Ecol. Èntomol. 2019, 44, 630–638. [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.R.; Wei, J.; Li, X.; Han, W.; Orians, C.M. Differing non-linear, lagged effects of temperature and precipitation on an insect herbivore and its host plant. Ecol. Èntomol. 2021, 46, 866–876. [CrossRef]

- Skendžić, S.; Zovko, M.; Živković, I.P.; Lešić, V.; Lemić, D. The impact of climate change on agricultural insects pests. Insects 2021, 12, 440. [CrossRef]

- Zhou X, Han F, Hao X, Pang B, Yang X, Zhang P: Effects of fluctuating and constant temperatures on the developmental rate of Galeruca daurica. Journal of Environmental Entomology 2016, 38:931-935.

- Wang Y, Wu J, Wan F: Insect responses to extreme high- and low-temperature stress. Journal of Environmental Entomology 2010, 32:250-255.

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, T.; Ren, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, M.; Cai, Y.; Yu, C.; Shu, R.; He, S.; Li, J.; et al. Decline in symbiont-dependent host detoxification metabolism contributes to increased insecticide susceptibility of insects under high temperature. ISME J. 2021, 15, 3693–3703. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; Fang, J.; Sun, W.; Ren, B. Effects of altered precipitation on insect community composition and structure in a meadow steppe. Ecol. Èntomol. 2014, 39, 453–461. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).