Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

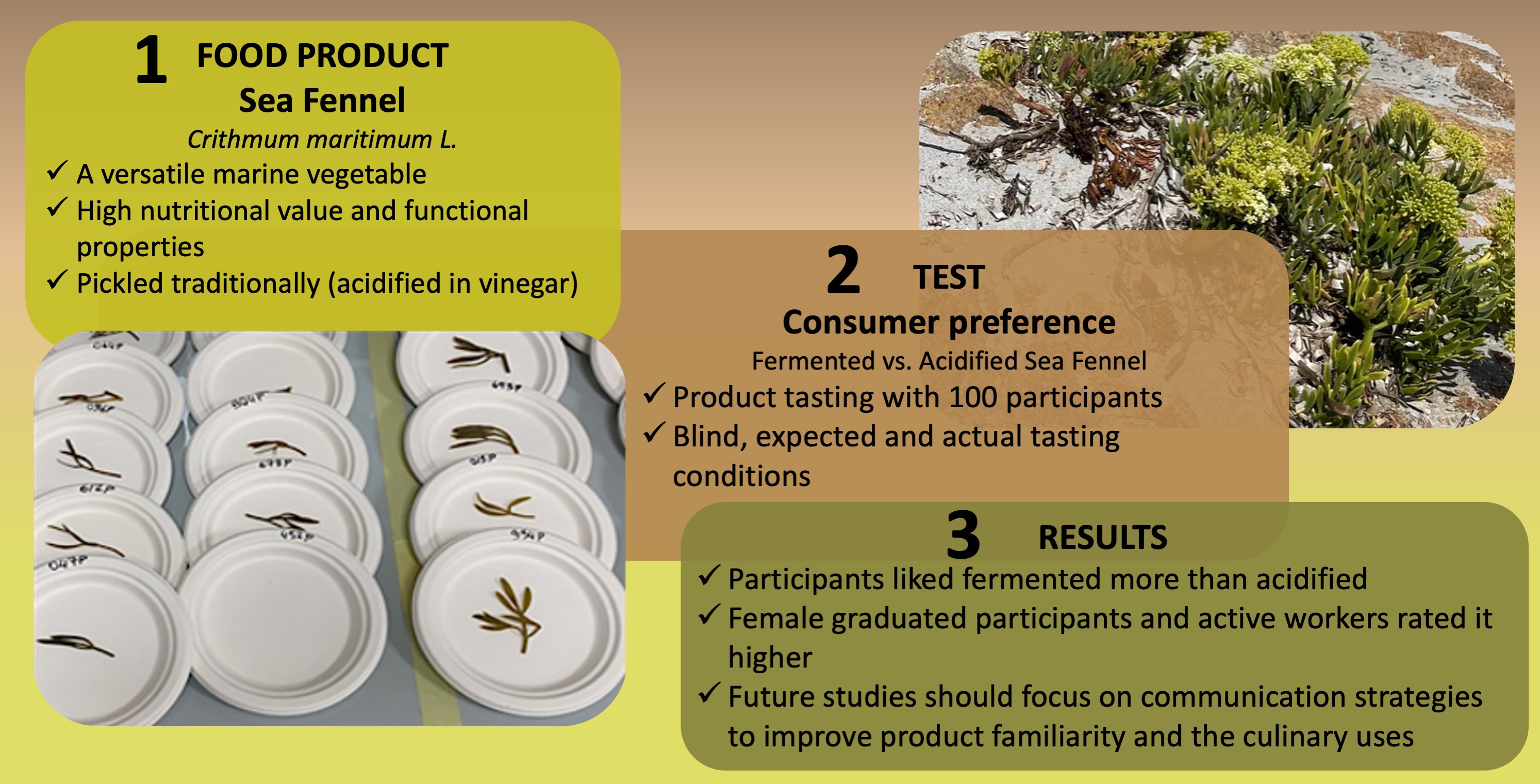

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sea Fennel Samples

2.2. Physico-Chemical Analysis

2.3. Consumer Studies

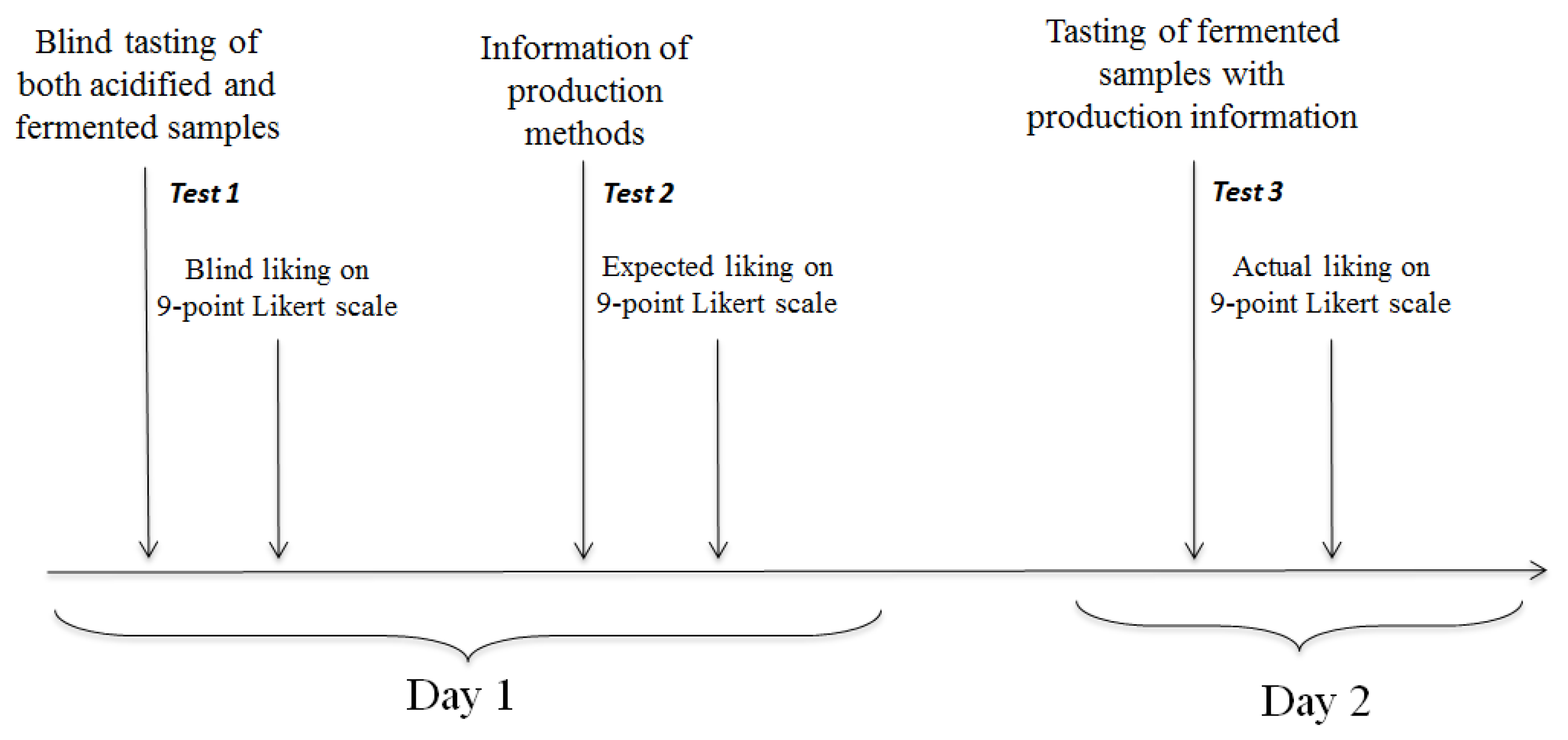

- Blind liking (perceived sensory acceptability): in Test 1, each participant tasted a sample of each sea fennel, acidified and fermented, without any information (bind condition). They expressed their liking scores over a 9-point Likert scale verbally anchored from ‘dislike extremely’ to ‘like extremely’ and at the mid-point with ‘neither like nor dislike’ [32].

-

Expected liking (expected acceptability): immediately after the blind liking test, Test 2 was conducted to determine the expected liking of both samples. The aim of Test 2 was to investigate the effect of information on the expected acceptability. To this end, each participant received an information sheet explaining the main characteristics of the acidified and fermented samples. Particularly, the descriptions were specifically neutral and focused on processes, without reporting the origin, brand, or health benefits of these products, to avoid any influence on the expected and actual liking procedure. The descriptions of both processes were as follows:

- Acidified sea fennel: The production of acidified sea fennel involves using preservation techniques, generally vinegar-based, through acidification by immersion in an acid solution. In addition to preserving food safely, this procedure gives the products a sour taste due to vinegar. This preservation process can be combined with a heat treatment (pasteurization) to obtain a safe product that can be preserved at room temperature. The acidified product can be consumed as it is, without rinsing in water.

- Fermented sea fennel: The production of fermented sea fennel involves using preservation techniques through lactic fermentation in brine, i.e., an aqueous solution with a salinity greater than 5%. In addition to preserving food safely, this procedure gives the products a sour taste due to lactic acid bacteria. This preservation process guarantees the preservation of safe products that can be stored at room temperature even without heat treatment (pasteurization), which would destroy some of their nutritional properties. For consumption, it is advisable to rinse the product briefly in fresh water to remove excess salt.

- 3.

- Actual liking (informed acceptability): test 3 was carried out on the second day (Day 2) and aimed to evaluate the effect of information on the actual liking of the innovative sea fennel sample (fermented). Participants simultaneously received the fermented sea fennel sample for tasting and the same product information sheet used in Test 2. They were asked to taste the sample after reading the information and invited to score their liking on the same scale as the previous two tests (see Figure 1 for the experimental design).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Physico-Chemical Characteristics

3.2. Consumer Acceptance of Sea Fennel Preserves

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petropoulos, S.A.; Karkanis, A.; Martins, N.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Edible Halophytes of the Mediterranean Basin: Potential Candidates for Novel Food Products. Trends Food Sci Technol 2018, 74, 69–84. [CrossRef]

- FAO The Future of Food and Agriculture: Alternative Pathways to 2050. Summary Version; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISBN 9789251309896.

- Panta, S.; Flowers, T.; Lane, P.; Doyle, R.; Haros, G.; Shabala, S. Halophyte Agriculture: Success Stories. Environ Exp Bot 2014, 107, 71–83. [CrossRef]

- Wendin, K.; Stedt, K.; Steinhagen, S.; Pavia, H.; Undeland, I. Sensory and Consumer Aspects of Sea Lettuce (Ulva Fenestrata) – Impact of Harvest Time, Cultivation Conditions and Protein Level. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100431. [CrossRef]

- Basheer, L.; Niv, D.; Cohen, A.; Gutman, R.; Hacham, Y.; Amir, R. Egyptian Broomrape (Phelipanche Aegyptiaca): From Foe to Friend? Evidence of High Nutritional Value and Potential Suitability for Food Use. Future Foods 2024, 10, 100413. [CrossRef]

- Ben Hamed, K.; Castagna, A.; Ranieri, A.; García-Caparrós, P.; Santin, M.; Hernandez, J.A.; Espin, G.B. Halophyte Based Mediterranean Agriculture in the Contexts of Food Insecurity and Global Climate Change. Environ Exp Bot 2021, 191, 104601. [CrossRef]

- Maoloni, A.; Milanović, V.; Osimani, A.; Cardinali, F.; Garofalo, C.; Belleggia, L.; Foligni, R.; Mannozzi, C.; Mozzon, M.; Cirlini, M.; et al. Exploitation of Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.) for Manufacturing of Novel High-Value Fermented Preserves. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2021, 127, 174–197. [CrossRef]

- Karkanis, A.; Polyzos, N.; Kompocholi, M.; Petropoulos, S.A. Rock Samphire, a Candidate Crop for Saline Agriculture: Cropping Practices, Chemical Composition and Health Effects. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12, 737. [CrossRef]

- Özcan, M. The Use of Yogurt as Starter in Rock Samphire (Crithmum Maritimum L.) Fermentation. Eur Food Res Technol 2000, 210, 424–426. [CrossRef]

- Atia, A.; Barhoumi, Z.; Mokded, R.; Abdelly, C.; Smaoui, A. Environmental Eco-Physiology and Economical Potential of the Halophyte Crithmum Maritimum L. (Apiaceae). Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 2011, 5, 3564–3571.

- Renna, M. Reviewing the Prospects of Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.) as Emerging Vegetable Crop. Plants 2018, 7, 92. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.G.; Barreira, L.; da Rosa Neng, N.; Nogueira, J.M.F.; Marques, C.; Santos, T.F.; Varela, J.; Custódio, L. Searching for New Sources of Innovative Products for the Food Industry within Halophyte Aromatic Plants: In Vitro Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic and Mineral Contents of Infusions and Decoctions of Crithmum Maritimum L. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2017, 107, 581–589. [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Gonnella, M. The Use of the Sea Fennel as a New Spice-Colorant in Culinary Preparations. Int J Gastron Food Sci 2012, 1, 111–115. [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Gonnella, M.; Caretto, S.; Mita, G.; Serio, F. Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.): From Underutilized Crop to New Dried Product for Food Use. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2017, 64, 205–216. [CrossRef]

- Meot-Duros, L.; Cérantola, S.; Talarmin, H.; Le Meur, C.; Le Floch, G.; Magné, C. New Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activities of Falcarindiol Isolated in Crithmum Maritimum L. Leaf Extract. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2010, 48, 553–557. [CrossRef]

- Maoloni, A.; Cardinali, F.; Milanović, V.; Osimani, A.; Verdenelli, M.C.; Coman, M.M.; Aquilanti, L. Exploratory Study for Probiotic Enrichment of a Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.) Preserve in Brine. Foods 2022, 11, 2219. [CrossRef]

- Alemán, A.; Marín, D.; Taladrid, D.; Montero, P.; Carmen Gómez-Guillén, M. Encapsulation of Antioxidant Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum) Aqueous and Ethanolic Extracts in Freeze-Dried Soy Phosphatidylcholine Liposomes. Food Research International 2019, 119, 665–674. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Faure, A.; Calvo, M.M.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Martín-Diana, A.B.; Rico, D.; Montero, M.P.; Gómez-Guillén, M. del C.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Martínez-Alvarez, O. Exploring the Potential of Common Iceplant, Seaside Arrowgrass and Sea Fennel as Edible Halophytic Plants. Food Research International 2020, 137, 109613. [CrossRef]

- Generalić Mekinić, I.; Blažević, I.; Mudnić, I.; Burčul, F.; Grga, M.; Skroza, D.; Jerčić, I.; Ljubenkov, I.; Boban, M.; Miloš, M.; et al. Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.): Phytochemical Profile, Antioxidative, Cholinesterase Inhibitory and Vasodilatory Activity. J Food Sci Technol 2016, 53, 3104–3112. [CrossRef]

- Martins-Noguerol, R.; Pérez-Ramos, I.M.; Matías, L.; Moreira, X.; Francisco, M.; García-González, A.; Troncoso-Ponce, A.M.; Thomasset, B.; Martínez-Force, E.; Moreno-Pérez, A.J.; et al. Crithmum Maritimum Seeds, a Potential Source for High-Quality Oil and Phenolic Compounds in Soils with No Agronomical Relevance. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 108. [CrossRef]

- Maoloni, A.; Cardinali, F.; Milanović, V.; Garofalo, C.; Osimani, A.; Mozzon, M.; Aquilanti, L. Microbiological Safety and Stability of Novel Green Sauces Made with Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.). Food Research International 2022, 157, 111463. [CrossRef]

- Nartea, A.; Orhotohwo, O.L.; Fanesi, B.; Lucci, P.; Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Aquilanti, L.; Casavecchia, S.; Quattrini, G.; Pacetti, D. Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.) Leaves and Flowers: Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity and Hypoglycaemic Potential. Food Biosci 2023, 56, 103417. [CrossRef]

- Politeo, O.; Popović, M.; Veršić Bratinčević, M.; Kovačević, K.; Urlić, B.; Generalić Mekinić, I. Chemical Profiling of Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L., Apiaceae) Essential Oils and Their Isolation Residual Waste-Waters. Plants 2023, 12, 214. [CrossRef]

- Souid, A.; Croce, C.M. Della; Frassinetti, S.; Gabriele, M.; Pozzo, L.; Ciardi, M.; Abdelly, C.; Hamed, K. Ben; Magné, C.; Longo, V. Nutraceutical Potential of Leaf Hydro-Ethanolic Extract of the Edible Halophyte Crithmum Maritimum L. Molecules 2021, 26, 5380. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, G.; Alves, M.I.; Neves, M.; Tecelão, C.; Ferreira-dias, S. Enrichment of Sunflower Oil with Ultrasound-Assisted Extracted Bioactive Compounds from Crithmum Maritimum L. Foods 2022, 11, 439. [CrossRef]

- Generalić Mekinić, I.; Šimat, V.; Ljubenkov, I.; Burčul, F.; Grga, M.; Mihajlovski, M.; Lončar, R.; Katalinić, V.; Skroza, D. Influence of the Vegetation Period on Sea Fennel, Crithmum Maritimum L. (Apiaceae), Phenolic Composition, Antioxidant and Anticholinesterase Activities. Ind Crops Prod 2018, 124, 947–953. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.G.; Moraes, C.B.; Franco, C.H.; Feltrin, C.; Grougnet, R.; Barbosa, E.G.; Panciera, M.; Correia, C.R.D.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Custódio, L. In Vitro Anti-Trypanosoma Cruzi Activity of Halophytes from Southern Portugal Reloaded: A Special Focus on Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.). Plants 2021, 10, 2235. [CrossRef]

- Radman, S.; Brzović, P.; Radunić, M.; Rako, A.; Šarolić, M.; Ninčević Runjić, T.; Urlić, B.; Generalić Mekinić, I. Vinegar-Preserved Sea Fennel: Chemistry, Color, Texture, Aroma, and Taste. Foods 2023, 12, 3812. [CrossRef]

- Custódio, M.; Lillebø, A.I.; Calado, R.; Villasante, S. Halophytes as Novel Marine Products – A Consumers’ Perspective in Portugal and Policy Implications. Mar Policy 2021, 133, 104731. [CrossRef]

- Rico, D.; Albertos, I.; Martinez-Alvarez, O.; Lopez-Caballero, M.E.; Martin-Diana, A.B. Use of Sea Fennel as a Natural Ingredient of Edible Films for Extending the Shelf Life of Fresh Fish Burgers. Molecules 2020, 25, 5260. [CrossRef]

- Amoruso, F.; Signore, A.; Gómez, P.A.; Martínez-Ballesta, M.D.C.; Giménez, A.; Franco, J.A.; Fernández, J.A.; Egea-Gilabert, C. Effect of Saline-Nutrient Solution on Yield, Quality, and Shelf-Life of Sea Fennel (Crithmum Maritimum L.) Plants. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 127. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Braghieri, A.; Piasentier, E.; Favotto, S.; Naspetti, S.; Zanoli, R. Cheese Liking and Consumer Willingness to Pay as Affected by Information about Organic Production. Journal of Dairy Research 2010, 77, 280–286. [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Iqbal, A.; Islam, M.N. Preservation of Carrot, Green Chilli and Brinjal by Fermentation and Pickling. Int Food Res J 2014, 21, 2405–2412.

- Wilson, E.M.; Johanningsmeier, S.D.; Osborne, J.A. Consumer Acceptability of Cucumber Pickles Produced by Fermentation in Calcium Chloride Brine for Reduced Environmental Impact. J Food Sci 2015, 80, 1360–1367. [CrossRef]

- Fernqvist, F.; Ekelund, L. Credence and the Effect on Consumer Liking of Food - A Review. Food Qual Prefer 2014, 32, 340–353. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.U.; Sarfraz, R.A. Effect of Different Nutraceuticals on Phytochemical and Mineral Composition as Well as Medicinal Properties of Home Made Mixed Vegetable Pickles. Food Biology 2018, 7, 24–27. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Diaz, I.M.; Breidt, F.; Buescher, R.W.; Arroyo-Lopez, F.N.; Jimenez-Diaz, R.; Fernandez, A.G.; Gallego, J.B.; Yoon, S.S.; Johanningsmeier, S.D. 51. Fermented and Acidified Vegetables. In Compendium of Methods for The Microbiological Examination of Foods; American Public Health Association, 2013.

- Rampanti, G.; Belleggia, L.; Cardinali, F.; Milanović, V.; Osimani, A.; Garofalo, C.; Ferrocino, I.; Aquilanti, L. Microbial Dynamics of a Specialty Italian Raw Ewe’s Milk Cheese Curdled with Extracts from Spontaneous and Cultivated Onopordum Tauricum Willd. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 219. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. Journal of Marketing Research 1980, 17, 460. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Caporale, G.; Carlucci, A.; Monteleone, E. Effect of Information about Animal Welfare and Product Nutritional Properties on Acceptability of Meat from Podolian Cattle. Food Qual Prefer 2007, 18, 305–312. [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.; Kallas, Z.; Rivera-Toapanta, E.; Karolyi, D.; Cerjak, M.; Lebret, B.; Lenoir, H.; Pugliese, C.; Aquilani, C.; Čandek-Potokar, M.; et al. Consumers’ Expectations and Liking of Traditional and Innovative Pork Products from European Autochthonous Pig Breeds. Meat Sci 2020, 168, 10879. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, V.V.; Renna, M.; Santamaria, P. Ortaggi Liberati - Dieci Prodotti Straordinari Della Biodiversità Pugliese; 2018th ed.; Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro: Bari, Italy, 2018; ISBN 978-88-6629-030-8.

- Deroy, O.; Reade, B.; Spence, C. The Insectivore’s Dilemma, and How to Take the West out of It. Food Qual Prefer 2015, 44, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.S.G.; Fischer, A.R.H.; van Trijp, H.C.M.; Stieger, M. Tasty but Nasty? Exploring the Role of Sensory-Liking and Food Appropriateness in the Willingness to Eat Unusual Novel Foods like Insects. Food Qual Prefer 2016, 48, 293–302. [CrossRef]

- Tuorila, H.; Meiselman, H.L.; Bell, R.; Cardello, A. V.; Johnson, W. Role of Sensory and Cognitive Information in the Enhancement of Certainty and Linking for Novel and Familiar Foods. Appetite 1994, 23, 231–246. [CrossRef]

- Ballco, P.; Gracia, A. Tackling Nutritional and Health Claims to Disentangle Their Effects on Consumer Food Choices and Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Food Qual Prefer 2022, 101, 104634. [CrossRef]

- Barkla, B.J.; Farzana, T.; Rose, T.J. Commercial Cultivation of Edible Halophytes: The Issue of Oxalates and Potential Mitigation Options. Agronomy 2024, 14, 242. [CrossRef]

- Stefani, G.; Romano, D.; Cavicchi, A. Consumer Expectations, Liking and Willingness to Pay for Specialty Foods: Do Sensory Characteristics Tell the Whole Story? Food Qual Prefer 2006, 17, 53–62. [CrossRef]

| Type of scores | Acidified sea fennel (traditional) |

Fermented sea fennel (innovative) |

|---|---|---|

| Blind liking | 5.09 ± 0.211 | 5.88 ± 0.22 |

| Expected liking | 5.71 ± 0.20 | 6.05 ± 0.20 |

| Actual liking | n/a | 5.96 ± 0.21 |

| Expected minus Blind | 0.621 | 0.17 |

| Actual minus Blind | n/a | 0.08 |

| Actual minus Expected | n/a | -0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).