Submitted:

21 October 2023

Posted:

24 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical clearance and recruitment of the participants

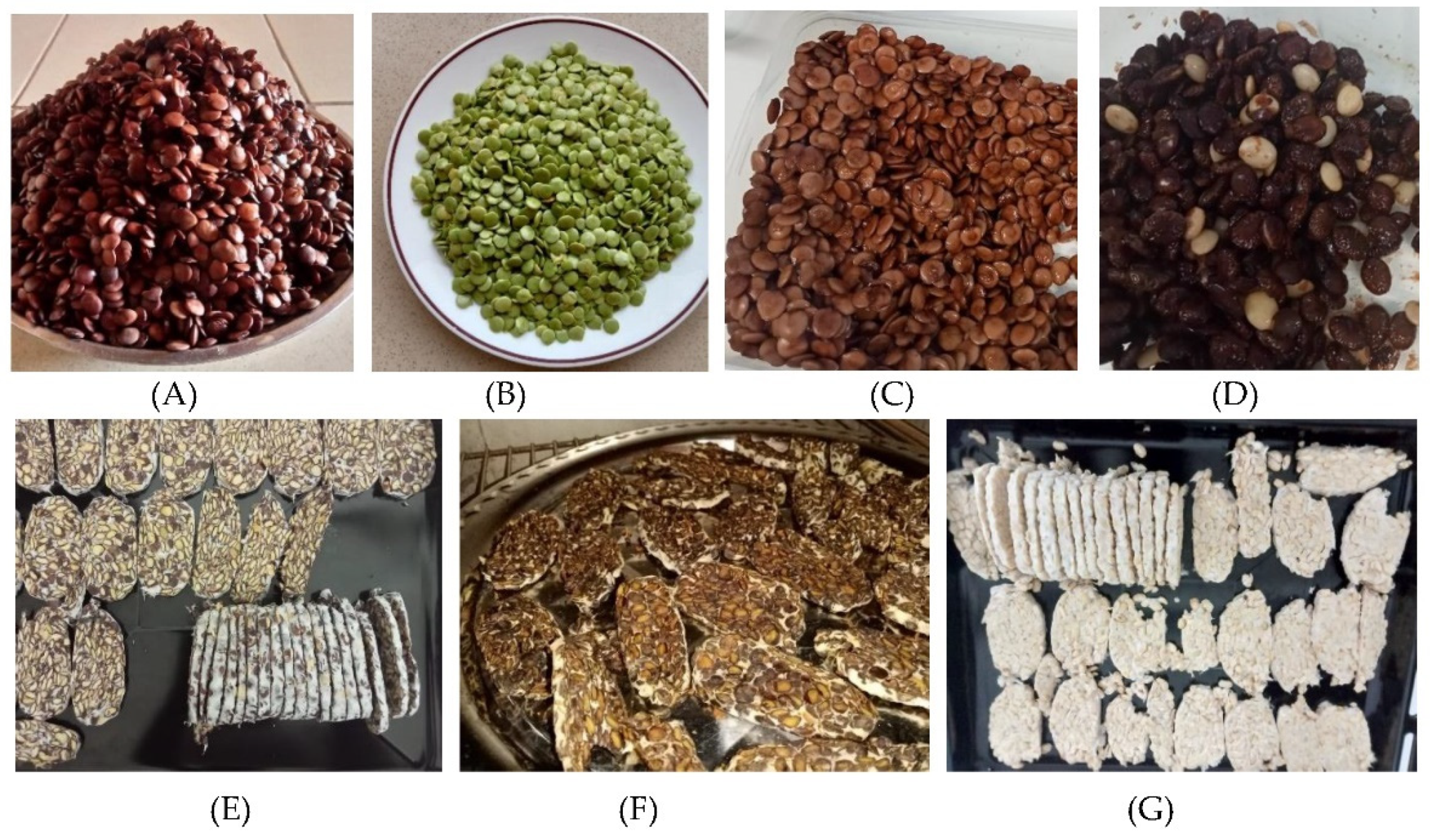

2.2. Products

2.3. Assessment of the products

2.3.1. Accommodation of the participants and pre-questionnaire

2.3.2. Sensory test and overall attitudes toward the products

2.4. Data collection and analysis

3. Results

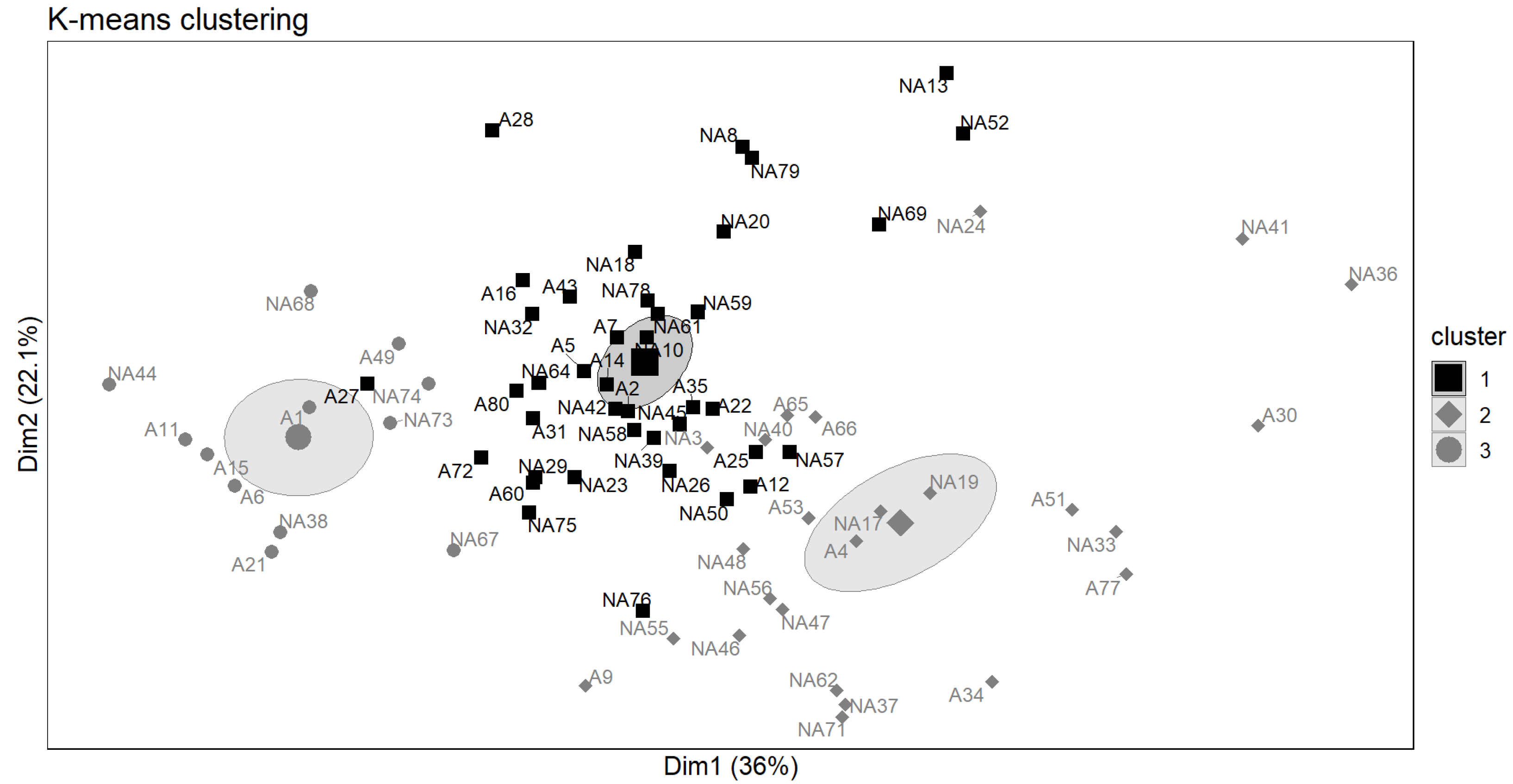

3.1. Panel composition and a priori of the participants

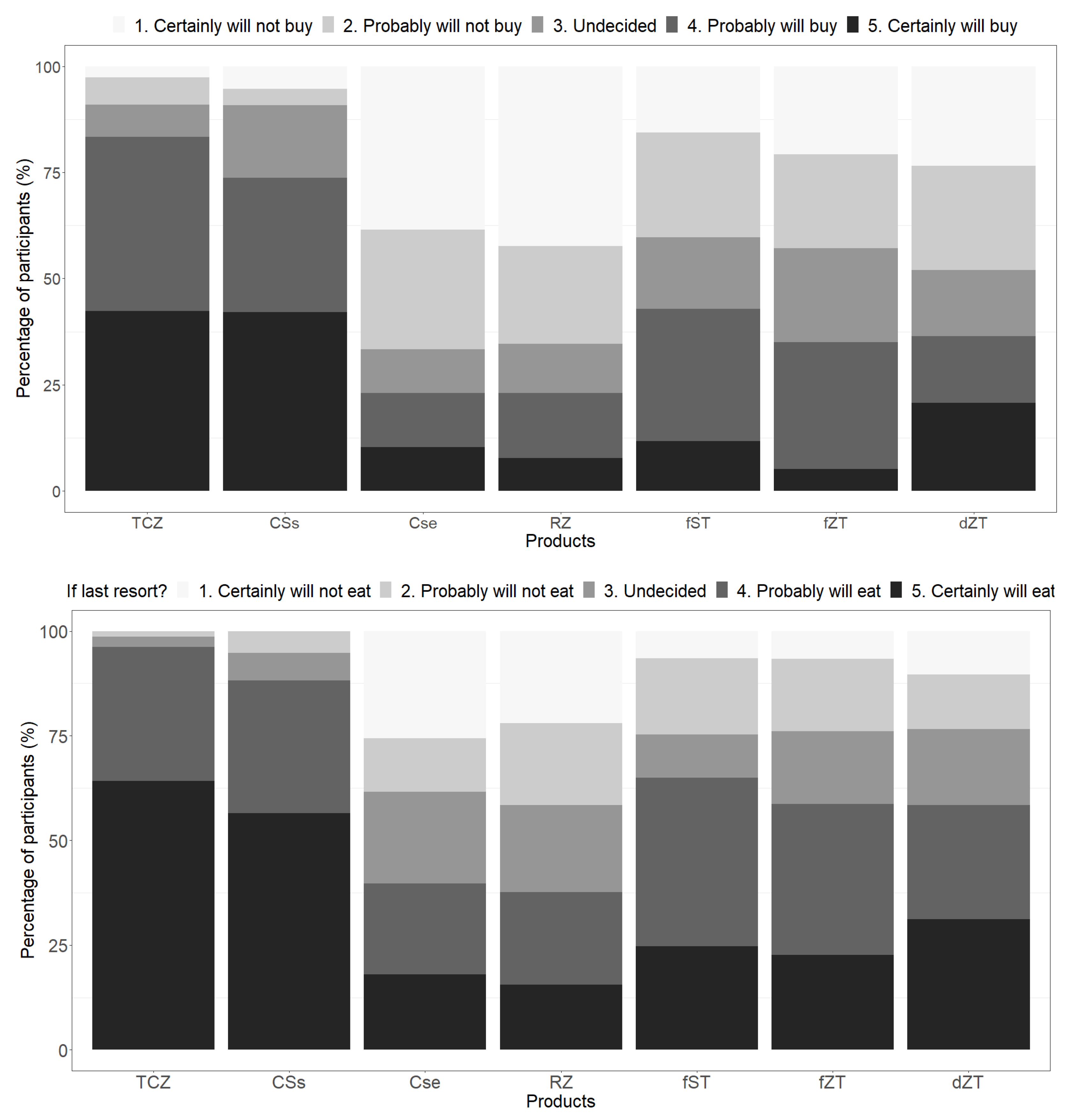

3.2. Sensory appeal of the products

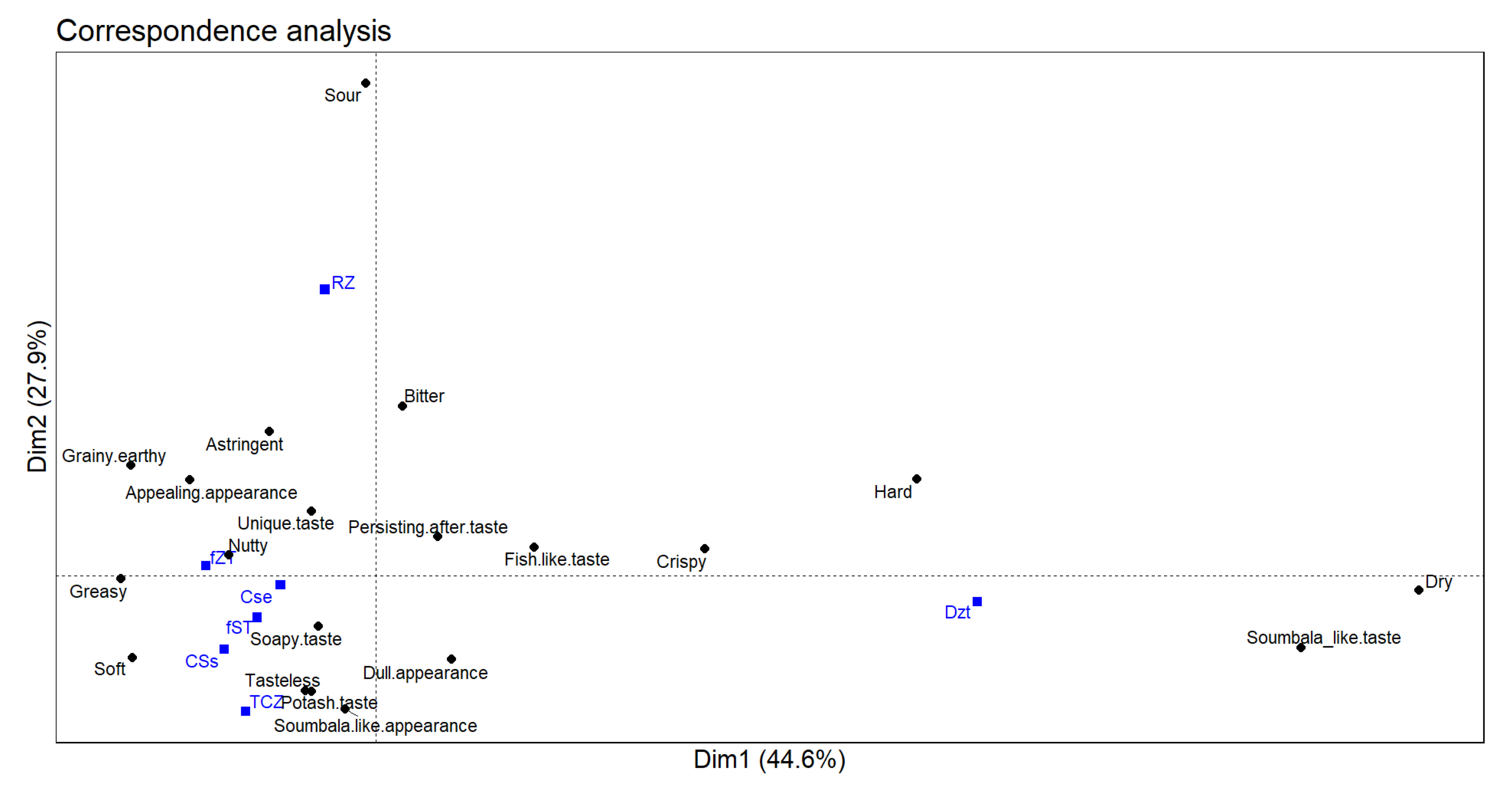

3.3. Sensory profile of the products

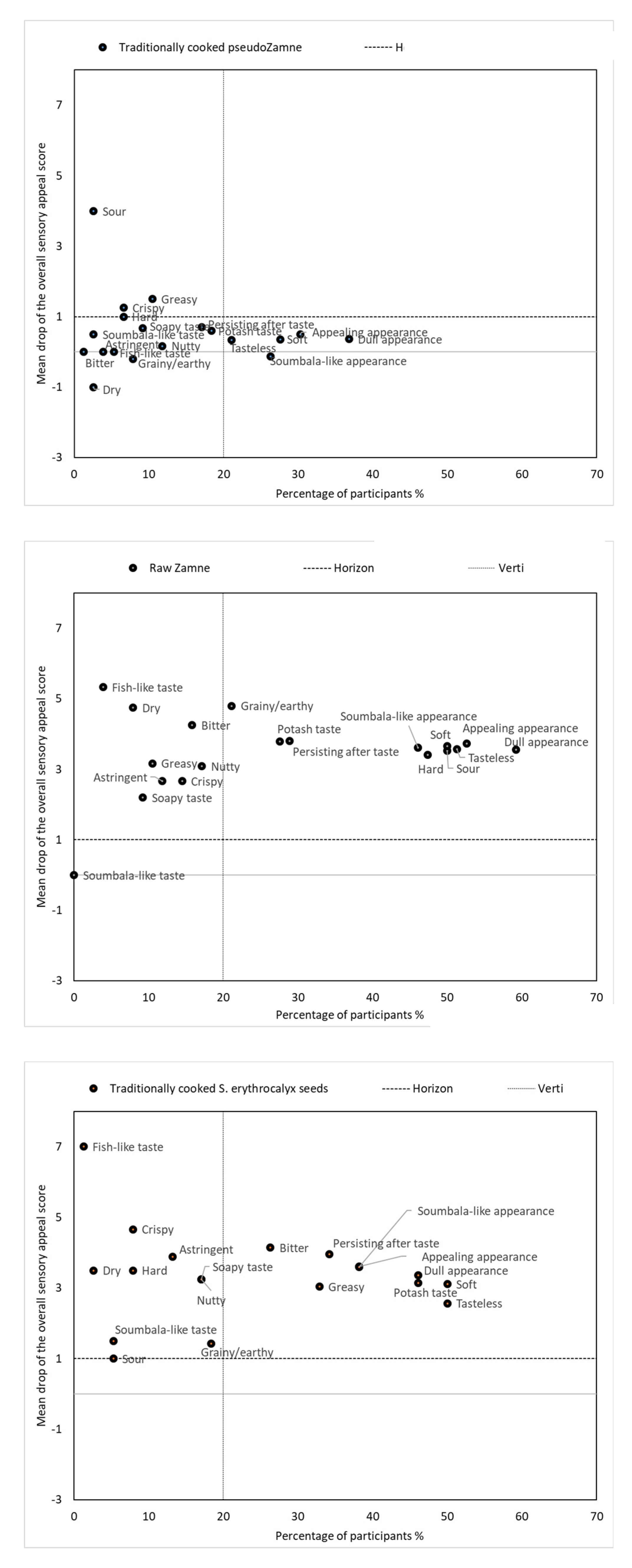

3.4. Penalties of the sensory attributes on the overall sensory appeal of the products

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asati, V.; Deepa, P.R.; Sharma, P.K. Silent Metabolism and Not-so-Silent Biological Activity: Possible Molecular Mechanisms of Stress Response in Edible Desert Legumes. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabo, M.S.; Shumoy, H.; Savadogo, A.; Raes, K. Inventory of Human-Edible Products from Native Acacia Sensu Lato in Africa, America, and Asia: Spotlight on Senegalia Seeds, Overlooked Wild Legumes in the Arid Tropics. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagg, C.W.; Stewart, J.L. The Value of Acacia and Prosopis in Arid and Semi-Arid Environments. J. Arid Environ. 1994, 27, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabo, M.S.; Savadogo, A.; Raes, K. Effects of Tempeh Fermentation Using Rhizopus Oryzae on the Nutritional and Flour Technological Properties of Zamnè (Senegalia Macrostachya Seeds): Exploration of Processing Alternatives for a Hard-to-Cook but Promising Wild Legume. Food Biosci. 2023, 54, 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabo, M.S.; Shumoy, H.; Cissé, H.; Parkouda, C.; Nikiéma, F.; Ismail, O.; Traoré, Y.; Savadogo, A.; Raes, K. Mapping the Variability in Physical, Cooking and Nutritional Properties of Zamnè, a Wild Food in Burkina Faso. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guissou, A.W.D.B.; Parkouda, C.; Ganaba, S.; Savadogo, A. Technology and Biochemical Changes Associated with the Production of Zamne : A Traditional Food of Senegalia Macrostachya Seeds from Western Africa. J. Exp. Food Chem. 2017, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnan-Winarno, A.D.; Cordeiro, L.; Winarno, F.G.; Gibbons, J.; Xiao, H. Tempeh: A Semicentennial Review on Its Health Benefits, Fermentation, Safety, Processing, Sustainability, and Affordability. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1717–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fibri, D.L.N.; Frøst, M.B. Indonesian Millennial Consumers’ Perception of Tempe – And How It Is Affected by Product Information and Consumer Psychographic Traits. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbonnier, M. Arbres, Arbustes et Lianes Des Zones Sèches d’Afrique de l’Ouest; 1st ed.; CIRAD-MNHN-UICN: Paris, 2000; ISBN 2-85653-530-5. [Google Scholar]

- Drabo, M.S. Spotlight on Senegalia Seeds, Overlooked Potentials and a Benchmark of Acacia Foods, Ghent University, 2023.

- Meilgaard, M.; Civille, G.V.; Carr, B.T. Sensory Evaluation Techniques, Third Edition; 3rd Editio.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, New York, 1999; ISBN 0-84930-276-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gacula, M.; Rutenbeck, S. Sample Size in Consumer Test and Descriptive Analysis. J. Sens. Stud. 2006, 21, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Tárrega, A.; Izquierdo, L.; Jaeger, S.R. Investigation of the Number of Consumers Necessary to Obtain Stable Sample and Descriptor Configurations from Check-All-That-Apply (CATA) Questions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.J. Experimental Designs Balanced for the Estimation of Residual Effects of Treatments. Aust. J. Sci. Res. 1949, 2, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Wood, A.; Green, B.G. Derivation and Evaluation of a Labeled Hedonic Scale. Chem. Senses 2009, 34, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, R. Use of Just-about-Right Scales in Consumer Research. In Novel techniques in sensory chracterization and consumer profiling; Varela, P., Ares, G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton -USA, 2014; pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management, Millenium Edition, 15th ed.; Pearson Custom Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 0–536–63099-2. [Google Scholar]

- Plaehn, D. CATA Penalty/Reward. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 24, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Dauber, C.; Fernández, E.; Giménez, A.; Varela, P. Penalty Analysis Based on CATA Questions to Identify Drivers of Liking and Directions for Product Reformulation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 32, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama-Ba, F.; Siedogo, M.; Ouedraogo, M.; Dao, A.; Dicko, H.M.; Diawara, B. Modalités de Consommation et Valeur Nutritionnelle Des Legumineuses Alimentaires Au Burkina Faso. African J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2017, 17, 12871–12888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamkoulga, M.; Waongo, A.; Sawadogo, L.; Sanon, A. Gestion Post-Récolte Des Graines d’Acacia Macrostachya Reichenb. Ex DC. Dans La Province Du Boulkiemdé Au Burkina Faso: Diagnostic Participatif En Milieu Paysan. J. Appl. Biosci. 2018, 130, 13148–13161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, H.E.; Sanderson, J.E.; Sultanbawa, Y. Lexicon for the Sensory Description of Australian Native Plant Foods and Ingredients. J. Sens. Stud. 2012, 27, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganaba, S. Caractérisation d’une Légumineuse Alimentaire Sauvage, l’arbre à Zamnè; Ceprodif, Ed.; 1er Essai.; Ceprodif: Ouagadougou, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, P.R.; Ge, S.; Hong, D.; Huang, H.; Jiao, G.; Knapp, S.; Kress, W.J.; Mooney, H.; Raven, P.H.; Wen, J.; et al. The Shenzhen Declaration on Plant Sciences — Uniting Plant Sciences and Society to Build a Green, Sustainable Earth. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariutti, L.R.B.; Rebelo, K.S.; Bisconsin-Junior, A.; de Morais, J.S.; Magnani, M.; Maldonade, I.R.; Madeira, N.R.; Tiengo, A.; Maróstica, M.R.; Cazarin, C.B.B. The Use of Alternative Food Sources to Improve Health and Guarantee Access and Food Intake. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; Almedom, A.M. What Is “Famine Food”? Distinguishing between Traditional Vegetables and Special Foods for Times of Hunger/Scarcity (Boumba, Niger). Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, H.; Jatwa, R.; Purohit, A. Antiatherosclerotic and Cardioprotective Potential of Acacia Senegal Seeds in Diet-Induced Atherosclerosis in Rabbits. Biochem. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 436848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egounlety, M. Sensory Evaluation and Nutritive Value of Tempe Snacks in West Africa. Int. J. Food Prop. 2001, 4, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osundahunsi, O.F.; Aworh, O.C. A Preliminary Study on the Use of Tempe-Based Formula as a Weaning Diet in Nigeria. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2002, 57, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njume, C.; Donkor, O.N.; Vasiljevic, T.; McAinch, A.J. Consumer Acceptability and Antidiabetic Properties of Flakes and Crackers Developed from Selected Native Australian Plant Species. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4484–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelat, K.J.; Adiamo, O.Q.; Mantilla, S.M.O.; Smyth, H.E.; Tinggi, U.; Hickey, S.; Rühmann, B.; Sieber, V.; Sultanbawa, Y. Overall Nutritional and Sensory Profile of Different Species of Australian Wattle Seeds (Acacia Spp.): Potential Food Sources in the Arid Semi-Arid Regions. Foods 2019, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, R. Wattle We Eat for Dinner. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Wattle We Eat for Dinner Workshop on Australian Acacias for Food Security; pp. 20111–146.

- Codex Alimentarius Regional Standard for Tempe (CODEX STAN 313R-2013) 2017, 3.

| Information on the participants | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 80 | 100 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 49 | 61 | |

| Male | 31 | 39 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 19–30 | 55 | 69 | |

| 31–40 | 21 | 26 | |

| 41–53 | 4 | 5 | |

| Fans of Zamnè | 31 | 39 | |

| Frequency of consumption of Zamnè | |||

| At least once every week | 3 | 4 | |

| At least once every month | 15 | 19 | |

| At least once every year | 25 | 31 | |

| Very occasional | 35 | 43 | |

| Tried only once | 2 | 3 | |

| Any knowledge of tempeh before this study? | |||

| Yes | 2 | 3 | |

| No | 78 | 97 | |

| % = percentage of the total participants | |||

| Descriptors | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reasons for liking the traditionally cooked Zamnè (N = 31) | |||

| Taste | 14 | 45 | |

| Nutritional properties | 11 | 35 | |

| Culture | 8 | 26 | |

| Wholesomeness | 4 | 13 | |

| Medicinal properties | 2 | 6 | |

| Not responded | 5 | 16 | |

| Reasons for disliking the traditionally cooked Zamnè (N = 49) | |||

| Low accessibility | 16 | 33 | |

| Tasteless | 11 | 22 | |

| Bitterness | 8 | 16 | |

| Smell | 2 | 4 | |

| Appearance | 1 | 2 | |

| Lack of nutritional information | 1 | 2 | |

| Cooking labor | 1 | 2 | |

| Not responded | 11 | 22 | |

| Expectations from any novel product from Zamnè (N = 80) | |||

| Higher nutritional properties | 30 | 38 | |

| Health benefits | 23 | 29 | |

| Easy to prepare | 19 | 24 | |

| Affordability | 2 | 3 | |

| ^ The table summarizes the responses to a check-all-that apply questionnaire and open-ended comments. n = number of respondents and % = percentage of the total participants (N) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).