1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was predominantly characterized as a public health event and disease mitigation and control measures were adopted accordingly [

1,

2]. However, subsequent analysis on pandemic preparedness and response measures recognized the multi-dimensional, concurrent and overlapping nature of social and economic threats (including war, political instability and food insecurity) and the impact these had on effective pandemic responses in different countries. We now know that the cumulative and amplifying effect of these threats created a syndemic; COVID-19 was not only a public health emergency of international concern, but also triggered by, and became the trigger for multiple structural inequalities. Syndemics examine how social and health conditions develop, how they interact, and the underlying factors driving these interactions [

3]. The term combines "synergy" and "epidemics," reflecting the concept that diseases do not occur in isolation. Instead, population health is often shaped by the interplay of various factors—such as climate change or social inequality—that contribute to multiple health issues disproportionately affecting certain groups [

4]. The interventions to contain the pandemic resulted in multiple unintended consequences including severe food insecurity and poor mental health, particularly in vulnerable groups such as externally and internally displaced refugees [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Recognition of the "syndemic” nature of COVID-19 would have enabled a better understanding of the interaction between biological conditions and social states, which potentially increased individuals’ susceptibility to harmful conditions [

10]. However, the evidence regarding the physiological interactions of co-occurring diseases during the COVID pandemic is still emerging. Challenges persist in defining and applying syndemics theory; demonstrating the complexity of syndemic systems also poses methodological challenges. A key methodological challenge in applying syndemics theory lies in capturing the dynamic and multidimensional interactions between social, environmental, and biological factors over time. For example, studying the interplay between food insecurity, mental health outcomes, and infectious diseases such as COVID-19 requires longitudinal data that tracks these variables simultaneously within affected populations. However, such data is often incomplete, inconsistent, or unavailable in resource-limited settings, making it difficult to demonstrate causality and the complexity of syndemic systems. Furthermore, integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches to account for cultural and contextual nuances adds another layer of methodological complexity. Despite these limitations, the syndemic framework presents a valuable opportunity for systems-level thinking. It encompasses the intricate interplay of social life, including public health and healthcare systems, economic and welfare policies, housing conditions, climate and environmental changes, and broader social structures, offering critical insights for shaping future pandemic preparedness and response strategies [

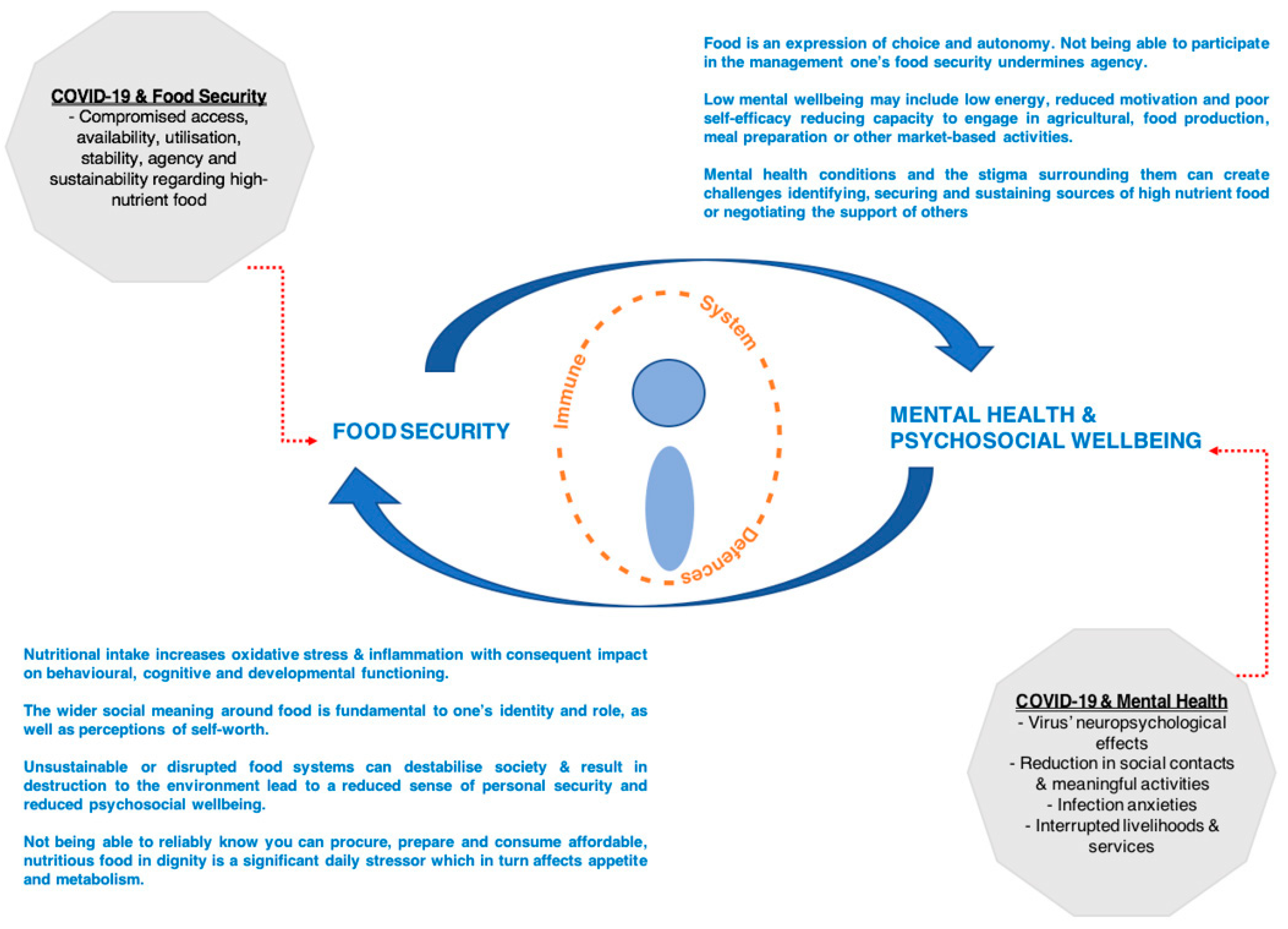

11]. Mental health and food security share a complex relationship, which has been further intensified by the impacts of COVID-19, amplifying their effects on health and psychosocial well-being (

Figure 1).

In this study, we explore the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity and mental health in displaced Syrians working in agricultural settings inside Syria and in neighboring countries.

The Syrian conflict, which began in 2011, resulted in the internal displacement of more than 7.2 million people [

12] and an estimated 6.6 million cross-border displaced Syrians. In absolute numbers, Türkiye hosts the majority of Syrian refugees, followed by Lebanon and Jordan (

Figure 2.). This mass exodus has placed immense economic and social pressure on host countries [

13,

14].

In 2020, there were approximately 5.6 million registered Syrian refugees in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Türkiye [

15]. Türkiye hosted the largest population of Syrian refugees in 2020, with 3,6 million Syrians registered [

12]. Lebanon accommodated approximately 1,5 million Syrian refugees, many of whom live in informal tent settlements and struggle to afford basic necessities [

12,

16,

17]. Jordan hosted over 1.3 million Syrians according to the Jordanian government [

18] (or 618,000 according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)), while Iraq recorded 244,760, a lower number compared to other neighboring countries [

19]. In Türkiye and Jordan, about 80% of Syrians residing in rural and urban areas face significant challenges, including inadequate living conditions, harassment from host communities, and limited access to essential resources such as education and food [

13,

20].

Syrians living in Syria and other countries in the Middle East had varying experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic due to important differences in economic and political stability within and between countries [

21]. Lebanon, for example, implemented early measures such as school closures and social distancing to curb the spread of COVID-19 [

21]. Syria's response was delayed as it was heavily reliant on support from the UNHCR and other Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), with limited access to personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing [

21]. Many countries, particularly those hosting large numbers of forcibly displaced persons, faced considerable challenges in responding to the pandemic due to limited resources and inadequate infrastructure [

22]. Due to the vulnerable status of refugees and issues within Syria in implementing measures to combat the spread of COVID-19, SSR are vulnerable to worsening conditions and at risk of not being included in global and local responses to COVID-19 [

23,

24].

1.1. Food Insecurity

Food insecurity (FI) is defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” [

25]. In practical terms, this often means that affected individuals must rely on cheaper, less nutritious food, reduce their overall food intake, and live with the constant uncertainty of whether they will be able to afford food in the future.

Prior to COVID-19, food insecurity was already a critical issue affecting the daily lives of Syrians. The ongoing conflict in Syria, subsequent changes in migration patterns and policies which resulted in the exclusion of refugees from formal labour markets have had significant long term economic and social effects [

26,

27] and have severely destabilised Syrian food security. In 2024, the World Food Programme (WFP) estimated that in Syria there are 12.9 million Syrians who are food insecure and 2.6 million Syrians at risk of hunger [

28]. In neighbouring countries like Jordan, more than half of Syrian refugees were still experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity [

29]. In 2023, 18% of Syrian households experienced severe food insecurity, with an additional 27% reported difficulties in affording food [

15]. While in Lebanon, 277,000 children under the age of five are affected by food poverty, including 85,000 who are living in conditions of severe food deprivation [

16].

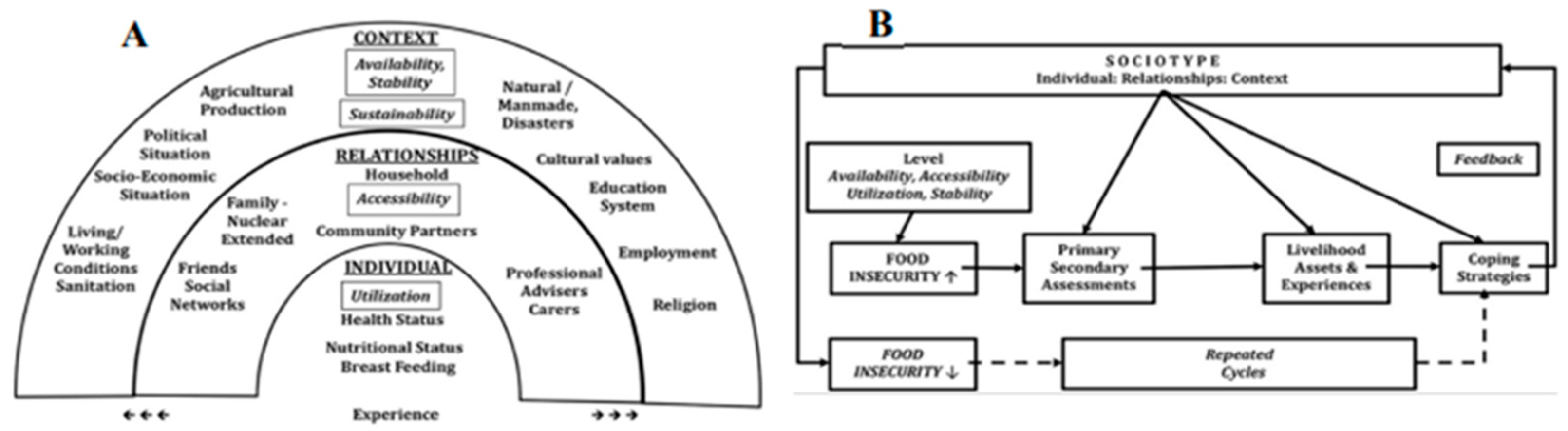

The 'Sociotype Ecological Framework' explores FI coping strategies by analysing how individuals, their relationships, and their broader context contribute to either sustaining or alleviating FI [

30].

Figure 3. illustrates the three interconnected domains: individuals, their relationships, and their wider context, highlighting their interactions and how coping strategies are perceived by those experiencing FI. Peng et al. (2018) propose a feedback loop within this framework, where events at the contextual level influence the individual, and individual-level actions, in turn, affect the broader context (

Figure 3B.). The Sociotype Ecological Framework's feedback loop can be applied to FI issues affecting Syrians and SSR. The conflict in Syria destabilised the country and its national food security (context), which subsequently impacted individual food security [

30]. As individuals and families sought refuge in neighbouring countries, the influx of refugees placed significant strain on the economic and social support systems of host nations, leading to increased FI rates [

30]. However, this perspective may oversimplify the situation by overlooking the influence of social and economic policies enacted in response to refugee migration. These policies are often restrictive, such as barring refugees from participating in formal labour markets, which can exacerbate FI and contribute to long-term negative economic outcomes [

26,

27]. For example, in Beqaa, Lebanon, Syrians residing in a large agricultural area were living in conditions of food insecurity and poor living standards; some Syrians were reliant on child labour, informal employment, and accumulating debt to mitigate food insecurity [

20,

31]. Governments and NGOs have attempted to distribute food aid via e-vouchers [

20,

32,

33]. This has resulted in collaborations between e-voucher recipients and shop owners creating collective food shopping and sharing practices to maximize resources [

33]. However, these collective practices may not always be compatible with the e-voucher systems and the associated policies in place to mitigate fraud and abuse of the e-voucher scheme, illustrating the dissonance between top-down and bottom-up approaches [

20,

30,

33]. The voucher system and compulsory dispersal policies might contribute to the isolation of refugees, fostering severe social exclusion. Efforts to promote the social inclusion of recognized refugees remain limited, inconsistent, and reliant on voluntary initiative [

34]. Other alternatives such as Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance (MPCA) have shown some long-term improvements in household food security [

35]. However, in general, formal assistance appears to have had little impact on reducing high levels of food insecurity [

36].

1.2. The Relationship Between Food Security and Mental Health

The relationship between food insecurity and mental health

1 (MH) is well established [

37,

38] and has been observed in Syrian communities worldwide, including Norway, Turkey and the United States of America [

39,

40,

41,

42]. The protracted nature and outcomes of the ongoing conflict mean that Syrians are predisposed to negative mental health experiences due to exacerbation of pre-existing mental disorders, emergence of new concerns, and issues related to adaptation to their current circumstances [

43]. However, the cross-sectional nature of these observational studies has made it difficult to conclusively determine directionality. Studies suggest that the relationship between mental health and food insecurity is likely bi-directional in any setting, not only in the humanitarian setting [

44,

45,

46,

47], but this is difficult to evidence conclusively in cross-sectional studies [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51].

Due to the nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were a number of rapid needs assessments on food insecurity and livelihoods for Syrian refugees, but limited research has been conducted among Syrians to investigate the relationship between food insecurity, mental health, and COVID-19. This study addresses this gap by investigating the relationship between food insecurity, mental health, and COVID-19 among displaced Syrians and SRR working in agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We used a mixed-methods approach utilizing data from a Household Survey and interviews with data collectors [

5,

52,

53]. The Household Survey was a multi-disciplinary research project designed to capture the experience of displaced Syrian agricultural workers during the COVID-19 pandemic during Summer 2020. A bottom-up approach was employed, emphasizing collaboration and co-creation with Syrian academics affiliated with the Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA)

2 and Lebanese research partners. This approach aimed to ensure that the research framework and outcomes were directly informed by the lived experiences, cultural knowledge, and expertise of those most affected. By prioritizing input from these stakeholders, the project sought to foster culturally relevant methodologies, amplify local perspectives, and promote equitable partnerships, ultimately ensuring that the findings and interventions were grounded in the realities of the communities they aimed to serve. Topics of the survey included socio-demographics; sanitation and cleanliness; mental health; physical health; food; livestock; work; individual and community coping strategies; and gender. Interviews were conducted with researchers who had collected the Household Survey data, to provide additional detail, context, and prospective concerning aspects of FI and MH during COVID-19.

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.2.1. Household Survey

Inclusion criteria for the survey required participants to have worked or work in agriculture. Recruitment was primarily conducted by CARA Syria academics. These researchers were mostly Syrian (as well as one Jordanian and two Lebanese), and except for one Syrian were based in the study countries, so directly affected by the pandemic. Researchers utilized professional contacts and their personal kinship networks together with the application of snowballing techniques to recruit participants. Participants were identified in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey, and 20 people were selected to take part in the study, from each country. Participants were paid the equivalent of £10 for participation either through phone credit or in cash. Cash payments were limited due to the pandemic.

2.2.2. Researcher Interviews

Researchers who collected data for the Household Survey were approached and invited for a semi-structured online interview. Because the researchers were also Syrian refugees and had experience with SSR communities outside the Household Survey, they were able to provide a unique perspective on current concerns that are rarely accessible to researchers based in the West. This allowed them to contribute valuable cultural context to the discussion.

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Household Survey

Prior to participating in the survey, respondents were provided with an information sheet detailing the study's aims and procedures, translated into Arabic to ensure comprehension. To enhance accessibility, interviewers conducted the survey verbally via phone, asking questions and recording responses. WhatsApp, an end-to-end encrypted messaging platform, was chosen for its widespread use among SSR for maintaining familial and social connections, as well as for its data security features. With participants' consent, phone conversations were recorded to ensure the accurate capture of data during interviews.

The questionnaire was developed as a pilot study. It included validated tools to measure food insecurity (Coping Strategies Index - CSI) and mental health (Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale - Seven-Item Version, SWEMWBS) [

54,

55,

56,

57]. The SWEMWBS was selected for its validity among Arabic-speaking populations. Local collaborators determined that its non-intrusive and positively framed wording made it well-suited to the sensitive humanitarian context [

52]. The scale addresses emotional and functional dimensions, tracking mood fluctuations and the impacts of daily stressors effectively.

The CSI was slightly adapted to fit the survey's context, adhering to guidelines from the 2008 Field Manual produced by the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere and the World Food Programme. Additionally, two COVID-19-specific measures (C19a and C19p) assessed participants' awareness and preparedness. C19a evaluated the availability and type of COVID-19 information SSR received, as well as its sources, while C19p assessed participants' preparedness, including access to face masks and hand sanitizer.

The survey consisted of 96 questions, with COVID-19-related data captured in questions 46-48 (C19a) and 55-56 (C19p). Data analysis was conducted using SPSS to ensure rigorous examination of responses.

2.3.2. Researcher Interviews

Five researchers, who collected data for the Household Survey, were interviewed in English, via Zoom/WhatsApp and their interviews were recorded with their consent. NVivo12 [

58] software was used to analyze the interviews. Coding and thematic analysis were conducted in Microsoft Word, with Miro (a mind mapping tool) being used to develop final visualizations of themes.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Household Survey

The raw data set was cleaned, and responses were removed that were either not demographic in nature (Q2-17) or concerning elements of the primary research question, i.e., MH (Q35-41), FI (Q57-68) or COVID-19 (Q46-48, Q55-56, Q85 and Q86). Questions regarding the location were simplified to the participants’ current country. The monthly rent was converted to USD to ease comparison between countries using historical exchange rates. Missing scores for CSI (FI) and SWEMWBS (MH) were replaced with mean averages for each question. Conversion for SWEMWBS scores was applied following guidelines and CSI scores were weighted according to its manual [

55]. Correlation and regression analyses were conducted to establish and determine the relationship between FI, MH, C19a and C19p. Household/societal responses to COVID-19 were used in Spearman’s correlation to identify relationships with FI, MH, C19a and C19p. Significant correlations with both FI and MH were further investigated using moderated hierarchical regression.

2.4.2. Researcher Interviews

Thematic analysis was conducted on interview transcripts per Braun and Clarke (2006). Thematic analysis was chosen in favour of interpretive phenomenological analysis as it allowed for patterning across all participants and flexibility in the coding and analysis process [

59,

60]. Thematic analysis also suited the interview focus of recounting experiences of survey participants second-hand [

61]. Familiarity with researcher interviews revealed that the impact of other economic and/or political factors on SSR should be considered in the analysis. The thematic analysis was therefore conducted in a theoretical/deductive manner in order to investigate the second-hand experiences of field work researchers and to describe the experience of research participants regarding mental wellbeing; food insecurity; and the impact of COVID-19 and other economic/political issues on SSR. The text was described in initial codes, and these were later refined to have consistency between the interviews. From these codes, patterns were identified and were assigned to themes. Themes were refined and checked against initial coding before being defined and named.

3. Results

3.1. Household Survey Results

Data was gathered for approximately 568 people (5,68 people- average household size). This was achieved by 100 household survey participants (75 males, 25 females) from Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey. Only MH scores were normally distributed, all other measures did not satisfy parametric assumptions (including normality). Therefore, all correlations were conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

3.1.1. Is There a Relationship Between FI and MH?

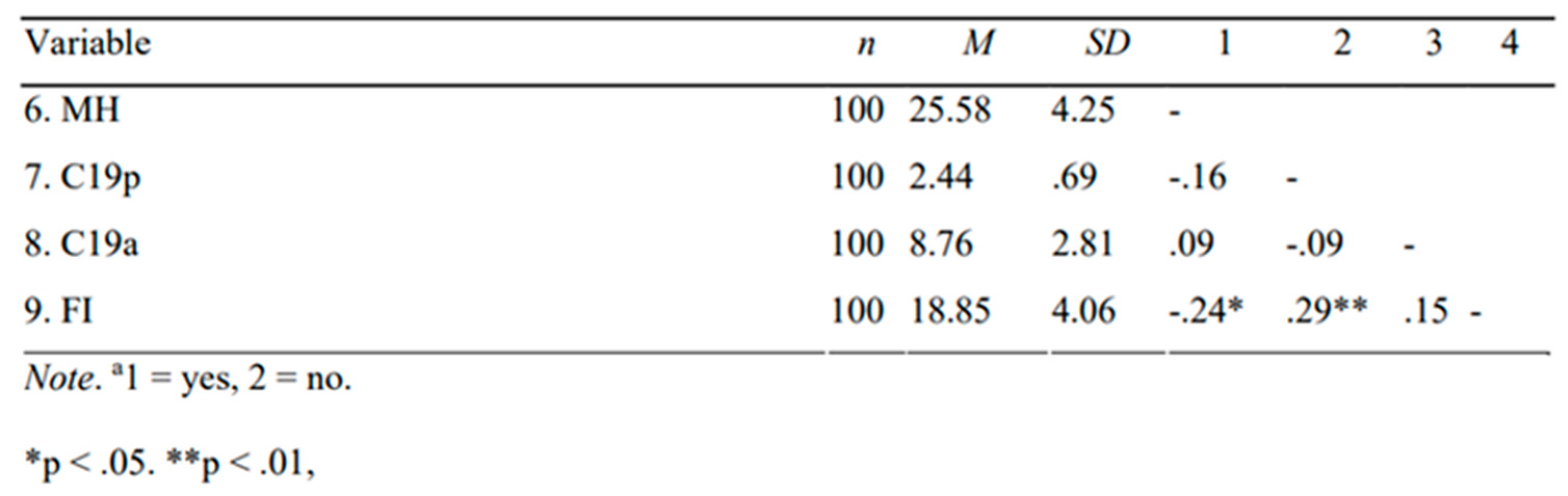

The average score for CSI measuring FI was 18.85 (SD = 4.06), and the average score for MH using the SWEMWBS was 25.58 (SD = 4.25), indicating moderate well-being among participants. A statistically significant correlation was found between FI and MH (rs = -.24, p = .018), illustrating that higher FI was associated with worse MH. Linear regression analysis confirmed that FI was a significant predictor of MH, explaining 4.7% of the variance in MH scores (b = .23, t(-2.199), p = .030) (

Appendix A,

Table A1).

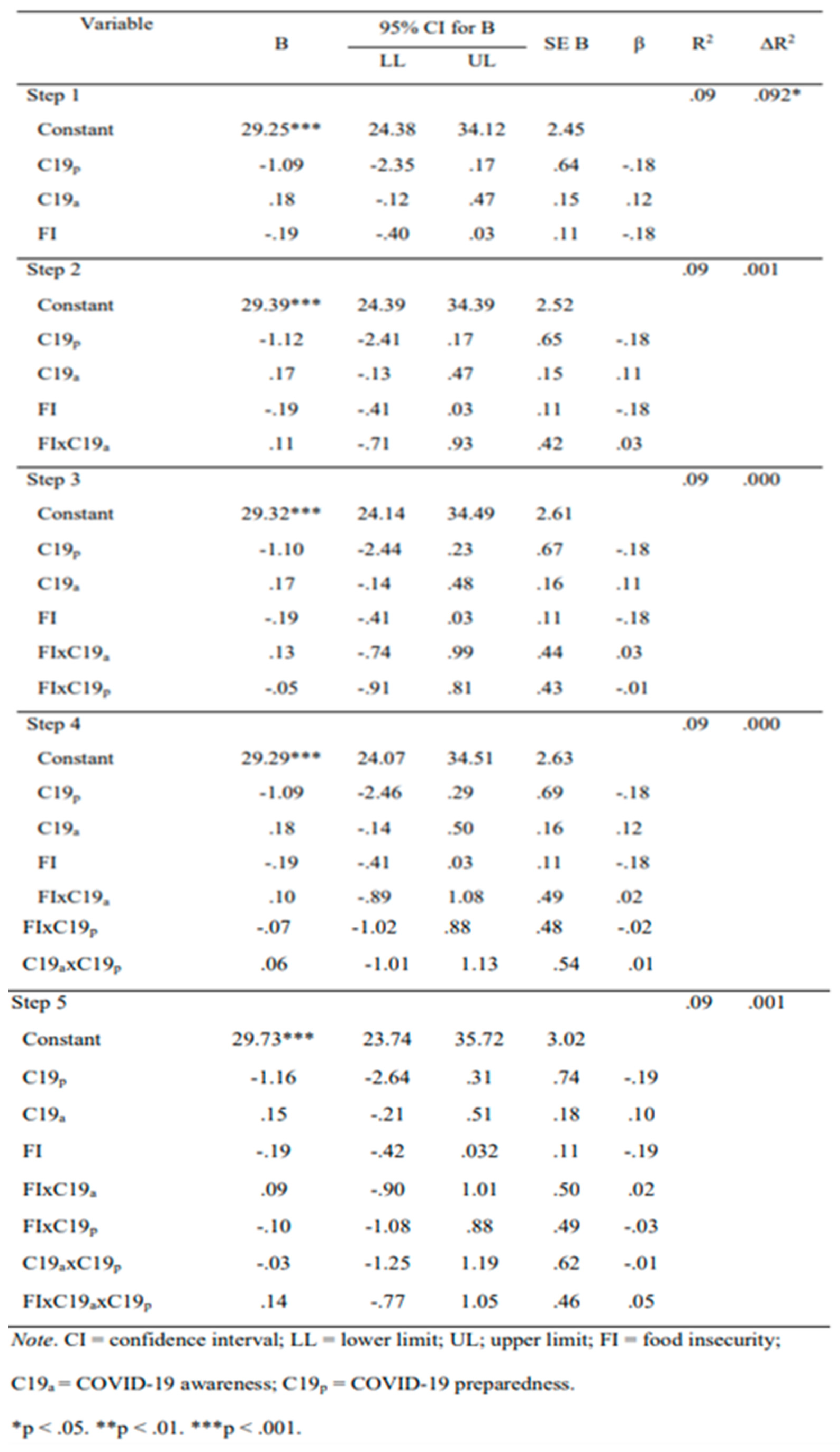

3.1.2. Is There a Relationship Between FI and MH Moderated by COVID-19 Awareness and Preparedness (Questions 46-48 (C19a) and 55-56 (C19p))?

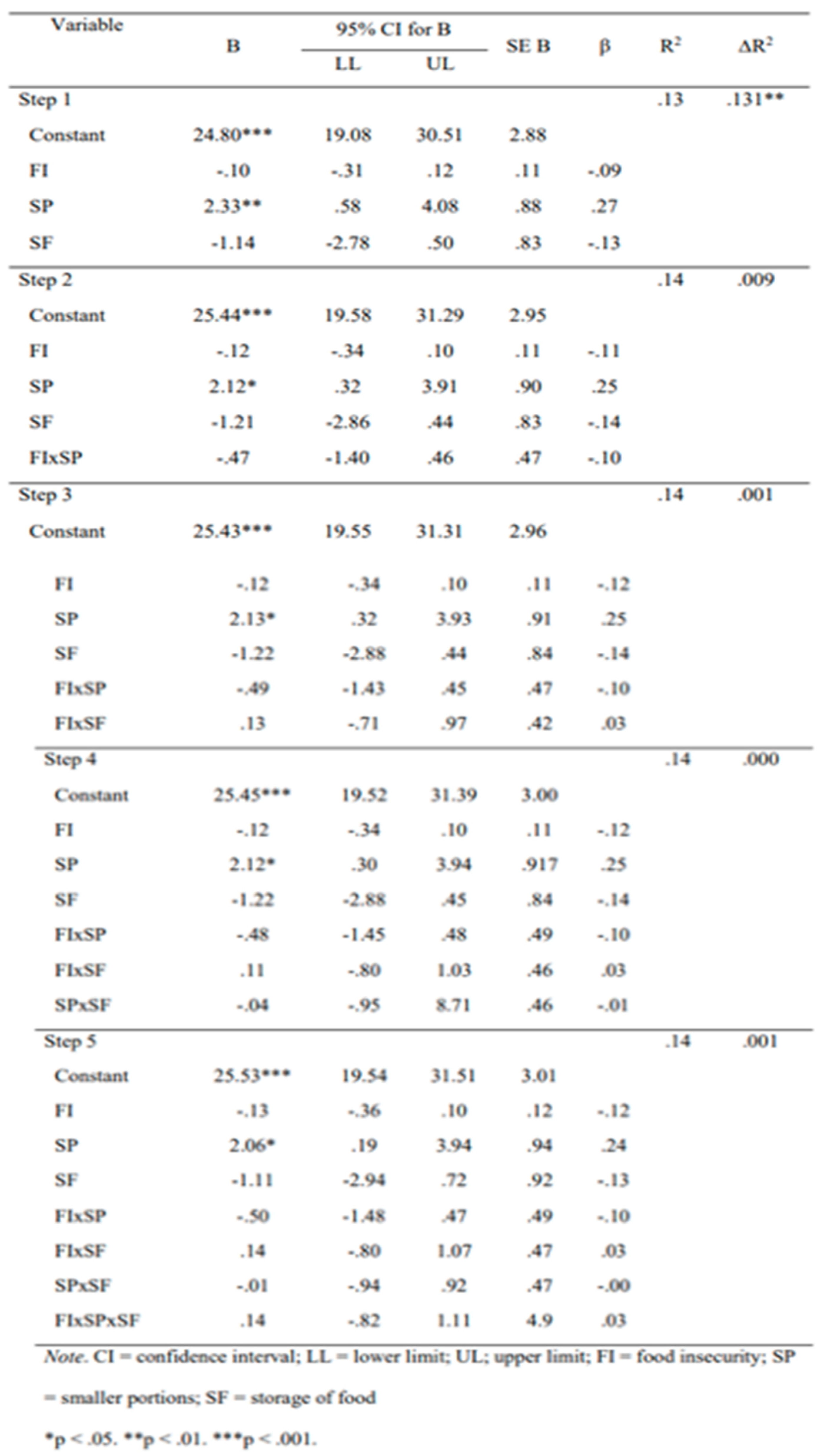

Spearman’s rank correlations were used to assess whether C19a and C19p moderated the relationship between FI and MH. A positive correlation was found between worse C19p and FI (rs = 0.29, p = 0.004). However, the hierarchical regression analysis showed that neither C19a nor C19p significantly moderated the relationship between FI and MH (

Table 1.).

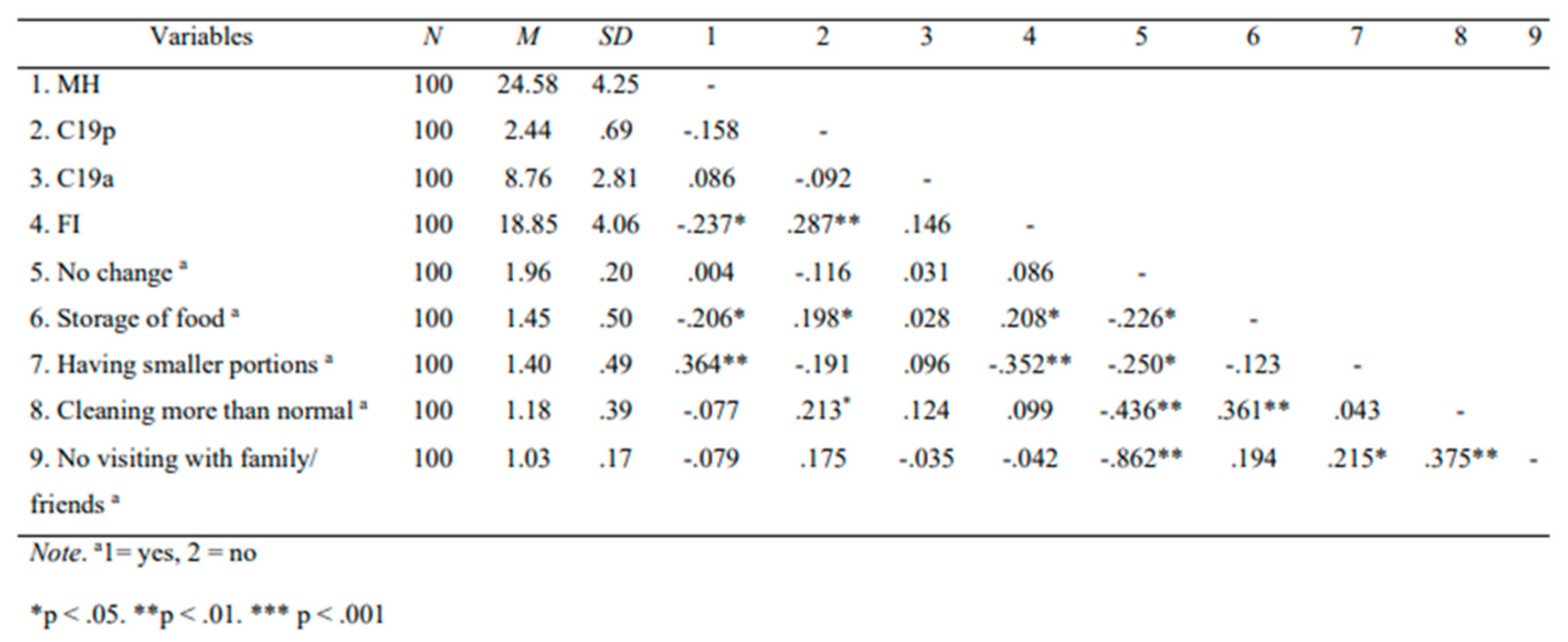

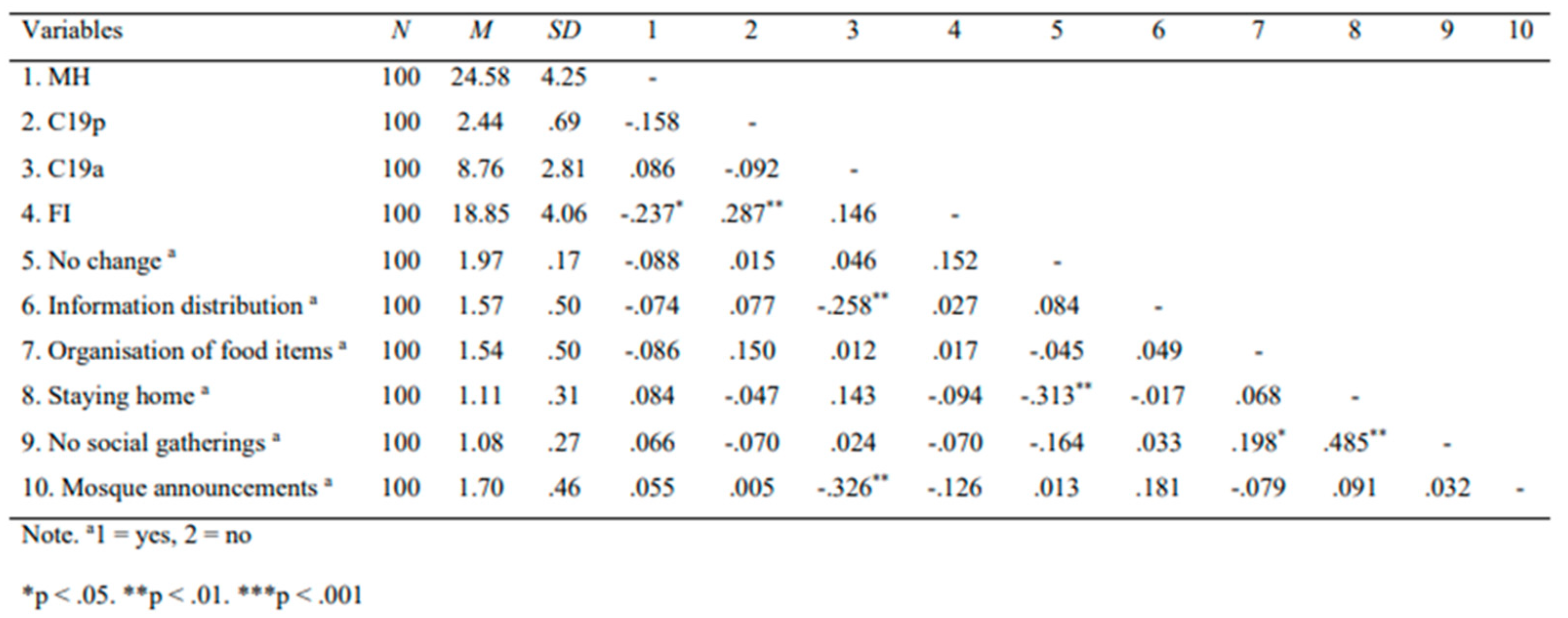

3.1.3. Is There a Relationship Between FI and Household/Societal COVID-19 Responses?

Two significant correlations were found at the household level: not storing food (rs = .21, p = .038) and having smaller meal portions (rs = -0.35, p <0.001) were associated with worse FI. No significant correlations were observed between FI and societal COVID-19 responses (

Appendix A,

Table A2 and

Table A3).

3.1.4. Is There a Relationship Between MH and Household/Societal COVID-19 Responses?

At the household level, storing food was correlated with better MH (rs = -0.21, p = 0.039), while having smaller portions was correlated with worse MH (rs = .364, p < 0.001). No significant correlations were found between MH and societal COVID-19 responses (

Appendix A,

Table A2 and

Table A3).

3.1.5. Does Storing Food or Having Smaller Portions in Response to COVID-19 Moderate the Relationship Between FI and MH?

Storing food and having smaller portion sizes were consistently significant predictors of MH and FI in the models. Upon conducting a moderated hierarchical regression, however, no significant moderation was found despite having smaller portion sizes being a consistently significant predictor in all models (

Table 2.).

3.2. Thematic Analysis Results: Researcher Interviews

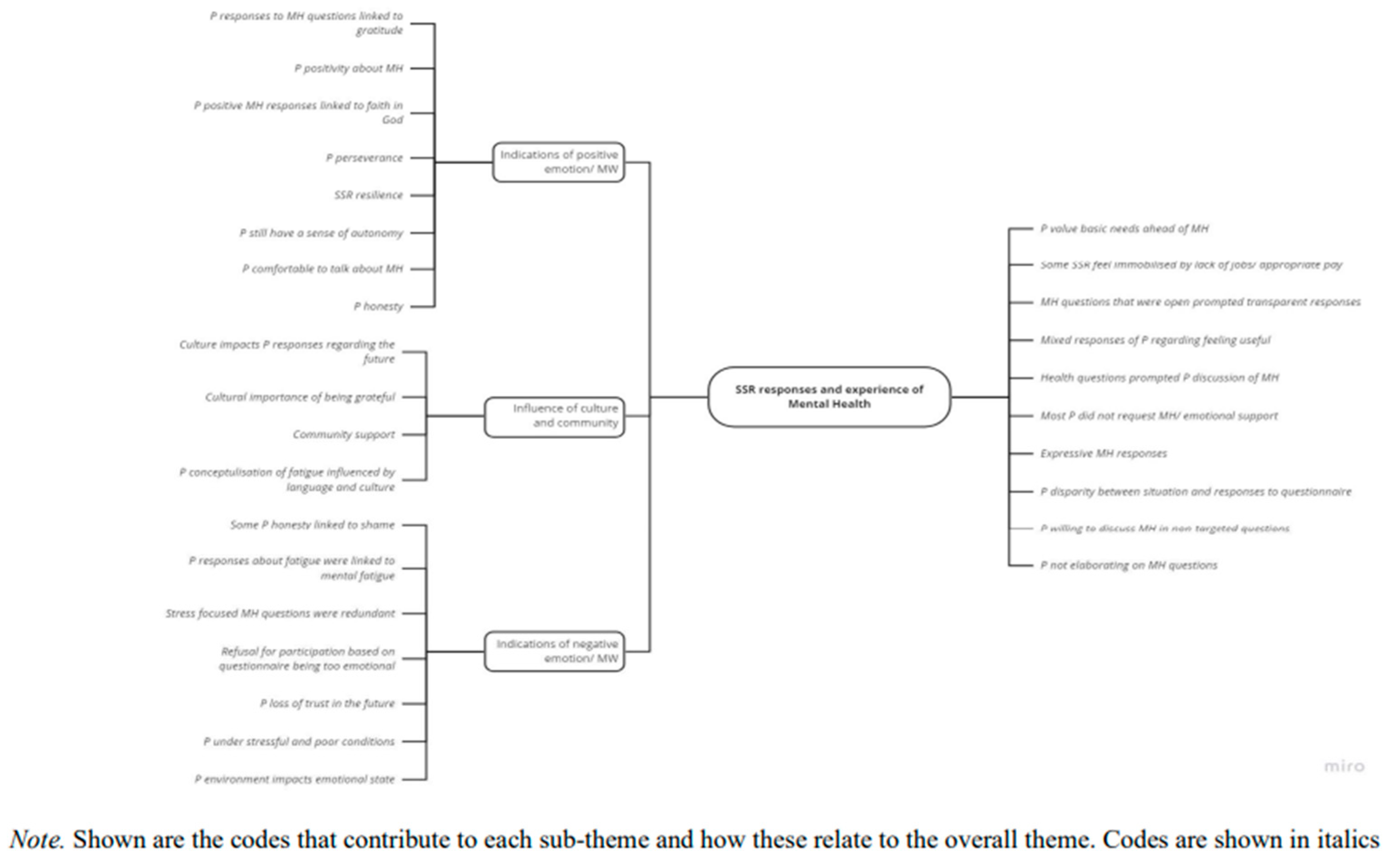

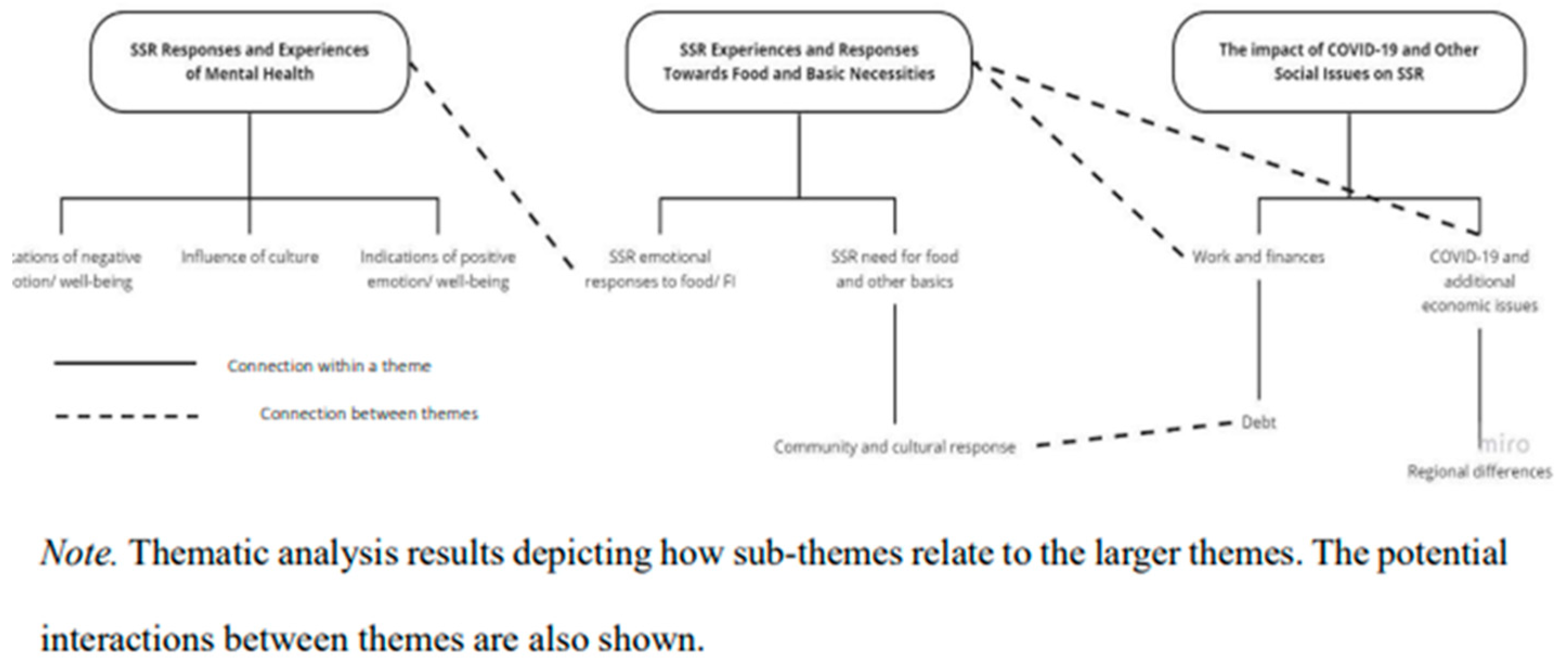

Deductive thematic analysis was conducted on the transcripts and additional emails from interviews with researchers who collected data from the Household Survey. Three main themes emerged (

Figure 4):

3.2.1. SSR Responses and Experiences of Mental Health:

Sub-themes collate the positive and negative aspects of MH indicated by researchers in these interviews and how culture may have an influence and included (

Appendix A,

Figure A1.):

Indications of Positive Emotion/Wellbeing: Many SSR expressed MH in positive terms, often linked to religious beliefs and a sense of resilience. However, there was a noted loss of trust in the future.

Indications of Negative Emotion/Well-being: Despite the general positive outlook, there were concerns about the future, especially regarding children’s well-being, reflecting the broader societal situations impacting the MH of SSR.

Influence of Culture and Community: Cultural and religious beliefs shaped how SSR participants expressed their mental health. A notable influence was the role of religious faith, which fostered a generally positive outlook despite challenges. Many participants emphasised gratitude towards God as a coping mechanism when faced with adversity, exemplified by expressions such as "thank God for what we have" (Interview 1). This perspective reflects the protective role of faith in providing comfort, hope, and meaning during times of hardship. Ramadan, occurring during the study period, was a particularly influential cultural factor. Religious fasting during Ramadan directly affected food consumption and preparation practices among participants, adding complexity to their experiences of food insecurity. Traditional Ramadan gatherings, which are central to fostering a sense of community and solidarity, were largely disrupted by COVID-19 social distancing measures. This limitation not only altered dietary practices but also impacted participants’ sense of belonging and social support, highlighting the intersection of religious observance, community dynamics, and the broader effects of the pandemic on psychosocial wellbeing.

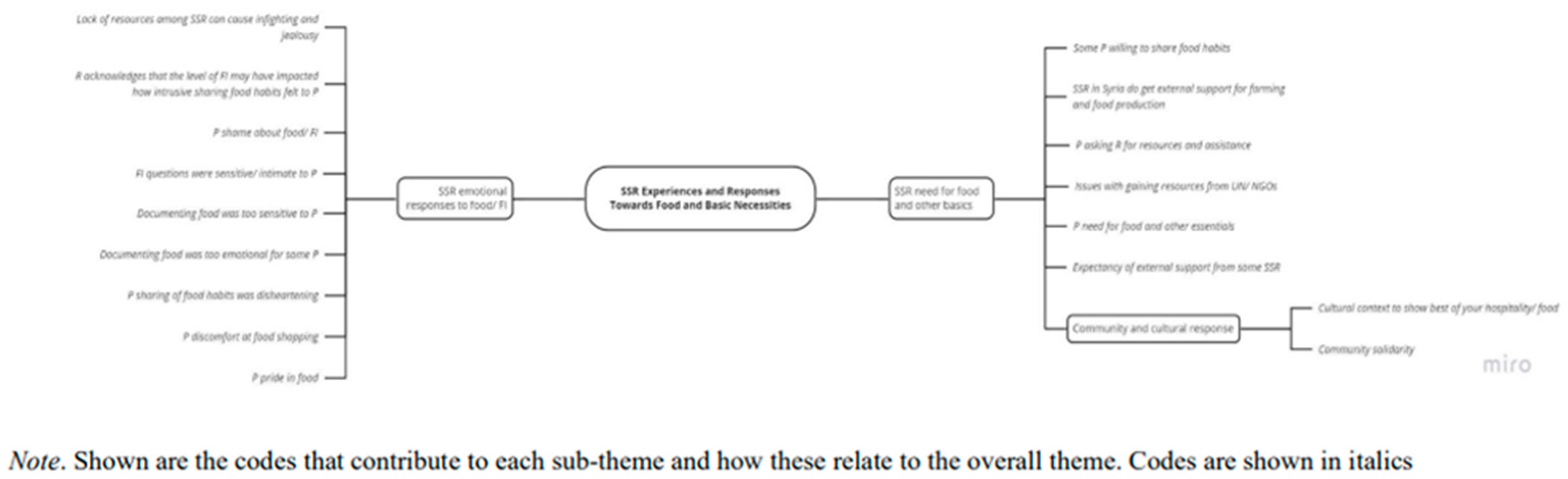

3.2.2. SSR Experiences and Responses Towards Food and Basic Necessities:

This theme incorporates the experience participants had with necessities, in particular food. Codes also were clustered under three sub-themes (

Appendix A,

Figure A2.)

Emotional Responses to FI/Food: SSR often expressed emotions an emotion-based approach when discussing food habits such as shame or distress. Nevertheless, others expressed pride in the nature of their cooking.

SSR Need for Food and Other Basics: This sub-theme highlighted the lack of availability of resources and SSR reliance on external bodies for support.

Community and Cultural Responses: A sense of solidarity and camaraderie within the community such as relying on neighbours for food was prevalent when managing FI.

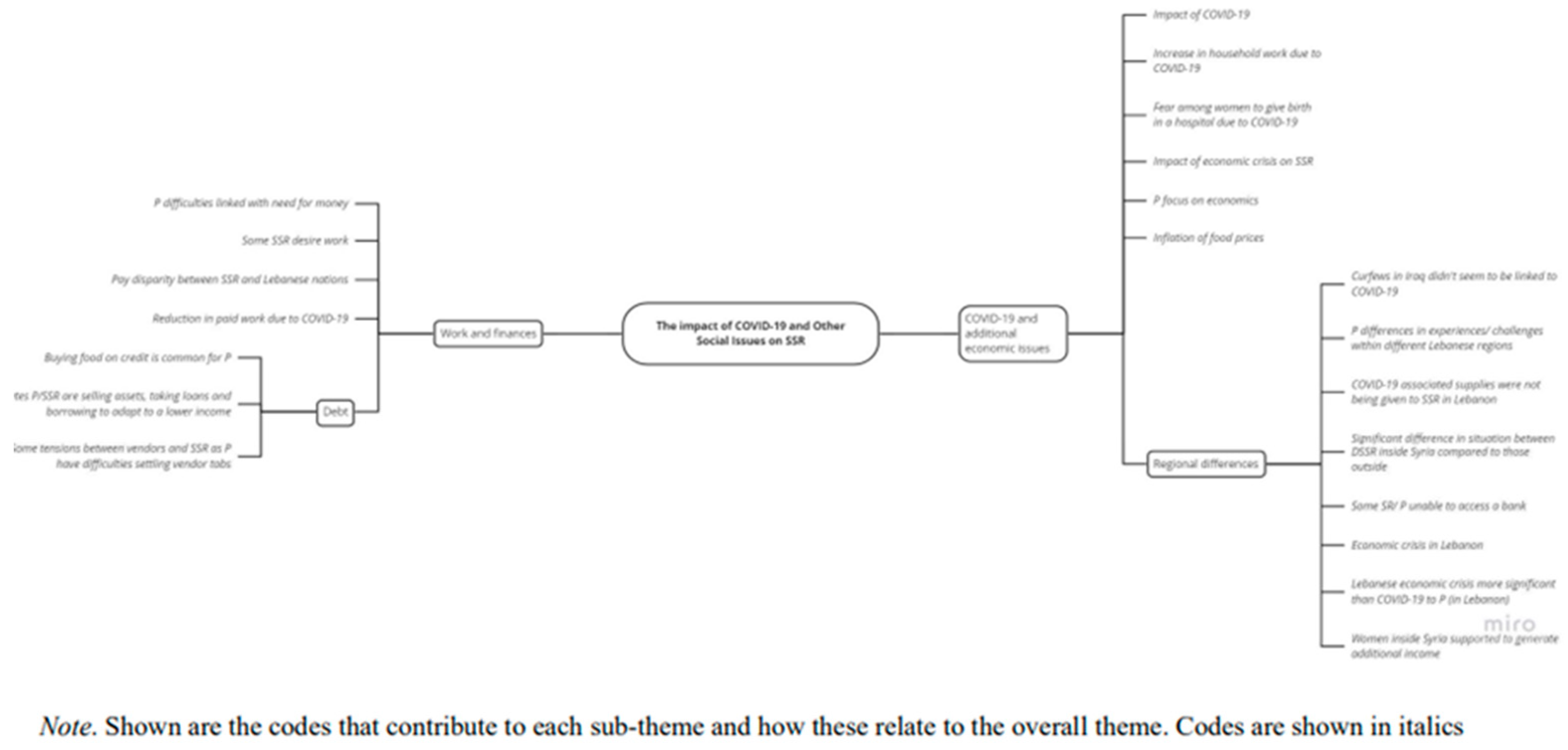

3.2.3. The Impact of COVID-19 and Other Social Issues on SSR

This theme captured the impact that COVID-19 and current economic/financial issues had on participants (

Appendix A,

Figure A3.).

COVID-19 and Additional Economic Issues: The impact of the pandemic was often overshadowed by pre-existing economic challenges, such as inflation. The pandemic merely exacerbated these difficulties. Some interviews referred to the current economic crisis in Lebanon as playing a significant role in impacting the lives of SSR.

Work and Financial Changes: The impact of COVID-19 and the existing economic challenges that Covid exacerbated were keenly observed through changes in work available to SSR. Many Syrian refugees lost their jobs due to disruptions in agricultural supply chains and pandemic-related restrictions, exacerbating already precarious working conditions shaped by limited labour rights and legal ambiguity. While work was disrupted for many, some displaced people continued working as the beginning of the pandemic coincided with the start of the agricultural season in the Middle East. However, many respondents reported having nothing left to sell and no one to borrow from, indicating that their communities' ability to cope with shocks had already been eroded before the pandemic. The study by Zuntz et al. (2021) (which draws on the same survey data), highlights the need for both short-term welfare assistance and longer-term reforms, such as formalising labour contractors' roles and fostering local employment forums, to better support refugees in volatile labour markets. SSR often resorted to selling assets or borrowing money to cope with financial difficulties, highlighting the impacts of the ongoing economic struggles.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted everyone, but affected people very differently. Those who had already been made vulnerable because of conflict, climate change or financial inequities were made even more vulnerable, for example populations such as SSR [

3]. This study examines the impacts beyond disease at an intersection of FI and MH among SSR during the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasising the syndemic effects [

8] that exacerbate the vulnerabilities of these populations. Through applying a mixed-methodological approach, this research provides insights into how FI and MH are interrelated and how SSR's resilience and coping mechanisms can inform future interventions and support strategies.

4.1. The Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Mental Health

4.1.1. Influences on Mental Health

Thematic analysis and quantitative findings revealed that, despite the pandemic, the mental health and attitudes of SSR were generally positive. Interviews with participants suggested that this positive MH was largely attributed to religious influences, such as gratitude to God. Religious beliefs are known to provide comfort, hope, and meaning, offering protective effects against psychological distress [

62,

63,

64]. Practices such as expressing gratitude, as observed among participants, have been associated with promoting positive well-being [

65]. However, while religious gratitude plays a significant role in fostering mental well-being, its impact appears less robust compared to dispositional gratitude [

66]. It is important to note, however, that the study by Aghababaei and Tabik (2013) involved Iranian Muslim students, limiting its applicability to adult SSR populations. Nonetheless, religious gratitude among this study’s participants remains valuable in promoting positive well-being and warrants consideration in future research and interventions.

Despite the generally positive MH, participants expressed a lack of trust in the future. Similar sentiments were reported by long-term displaced Syrian refugees in Lebanon, who experienced anxiety, depression, hopelessness, sadness, and diminished self-worth [

67]. Such feelings of hopelessness can significantly affect long-term MH outcomes [

68]. Among this study’s participants, these issues were often indirectly revealed through questions about physical health, current circumstances, or the environment. This aligns with Syam et al.'s (2019) findings that environmental factors, including harassment, unsafe living conditions, and social isolation, profoundly impact MH.

Neither this study nor Syam et al. (2019) examined the potential role of targeted MH questions in shaping participants' responses. Participants might feel more comfortable disclosing MH concerns in response to indirect questions rather than direct ones, where cultural norms like religious gratitude could influence answers. However, further research is needed to determine whether indirect questioning elicits more candid responses regarding negative MH among SSR.

4.1.2. Influences on Food Security

The Household Survey revealed significant levels of FI among participants and identified various coping mechanisms, further illuminated through thematic analysis. The theme of “SSR experiences and responses towards food and basic necessities” highlighted collective strategies, such as community solidarity, children dining with other families, and vendors offering “tabs” for individuals unable to pay upfront. These responses are consistent with the Sociotype Ecological Framework, which emphasises leveraging relationships and contextual resources to manage FI [

30]. However, while these coping mechanisms align with theoretical frameworks, it is important to acknowledge that most respondents reported being unable to borrow from family, friends, or neighbours because networks of solidarity had already been eroded by years of precarity. This reality highlights a critical gap: although formal interventions often fail to complement or build upon collective practices [

20,

33], the erosion of these networks means that many individuals could not rely on collective coping mechanisms.

When external interventions overlook the autonomy and resilience patterns of SSR, they risk disempowering communities rather than supporting them [

69]. Effective FI interventions should prioritise empowering SSR by integrating their resilience strategies, such as involving them in intervention design or engaging community advocates as points of contact [

70,

71]. Innovative approaches, such as Multi-Purpose Cash and re-evaluating e-voucher systems in Lebanon, have demonstrated promise in supporting collaborative, community-based FI responses [

20,

35]. However, some participants employed erosive coping mechanisms that undermined long-term well-being, such as skipping meals, reducing dietary diversity, and selling essential assets. These strategies exacerbate household vulnerability, deplete resources, and pose significant risks to physical and mental health as FI intensifies [

24].

It is crucial to avoid romanticising “community-based resilience pathways” when addressing FI. The underlying issue lies in the lack of rights for Syrians as refugees and workers across host countries, exposing them to exploitative labour conditions while largely excluding them from healthcare access. Without a rights-based approach to addressing Syrian displacement, celebrating community resilience risks masking the systemic failures of host countries and the international community. These communities are not only under extreme pressure but also neglected in their basic human rights, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable, rights-centred solutions [

72,

73].

4.1.3. Food Insecurity and Mental Health

The study confirmed a relationship between FI and MH, with FI predicting a small but significant portion of the variance in mental health outcomes. However, this relationship is likely influenced by other factors. While the thematic analysis indicated generally positive MH, negative emotional responses related to food were also observed. Responses of shame, embarrassment, and sensitivity about food were significant, indicating a potential link between these emotions and the relationship between FI and MH. The Sociotype Ecological Framework emphasised that resilience is essential not only in buffering against poor MH but also in coping with food insecurity [

30]. Consequently, future prospective longitudinal research is required to quantify the impact they have over FI and MH.

4.2. Food Insecurity and Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19

4.2.1. Impact of Household Responses to COVID-19

No correlation was observed between COVID-19 Awareness (C19a) and COVID-19 Preparedness (C19p). This may demonstrate that COVID-19 information was not translated into action to prevent the spread of disease, potentially because of a general lack of resources among SSR [

74,

75,

76,

77]. This lack of resources, coupled with high FI, highlights the challenges SSR faced in accessing appropriate PPE and maintaining their livelihoods during lockdowns [

78]. The results of this study align with broader research indicating that syndemic effects, such as limited access to PPE and other general resources, exacerbate the vulnerabilities of SSR [

3,

10].

This position, however, does not consider that a relationship between FI and COVID-19 Preparedness (C19p) may be driven by a fear of developing COVID-19 rather than a lack of resources alone [

79]. Although the study did not find a quantitative relationship between COVID-19 Awareness (C19a) and MH, the qualitative data suggest that fear of the disease may have significantly affected the lives of SSR, particularly in relation to FI and MH. Household responses to the pandemic, such as storing food and reducing portion sizes, were significantly correlated with both FI and MH. The study highlighted a complex interplay between FI and MH among participants during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the data initially suggested the potential for a bi-directional relationship—where FI could both result from and contribute to poor MH—triangulating these findings with other data points challenges this interpretation. Specifically, the survey revealed high rates of unemployment and limited access to cash among participants, which directly necessitated coping strategies such as reducing food intake and an inability to store provisions. These economic constraints, rather than MH challenges, emerged as the primary drivers of household behaviors related to FI.

The findings underscore the structural nature of FI within this population, rooted in systemic economic challenges exacerbated by the pandemic. This reinforces the need for targeted interventions addressing economic vulnerabilities as a pathway to improving both FI and MH outcomes in SSR populations. However, the study could not determine whether these responses were a result of poor mental health or contributed to it, suggesting a potential bi-directional relationship between FI and MH in the context of COVID-19 [

44,

45,

47]. Such findings would be best supported by a follow-up study considering the longitudinal effects of COVID-19 on FI and MH.

4.2.2. Impact of Societal Responses to COVID-19

Quantitative analysis did not establish a relationship between societal responses to COVID-19 and FI/MH. However, qualitative analysis highlighted the significant impact of work changes and economic environment on SSR as a result of the pandemic. As global food prices soared due to disruptions in food supply chains and economic recession [

80,

81,

82,

83], SSR experienced worsening financial circumstances and increased FI [

82,

83]. Interviews revealed that the pandemic's economic impact such as lack of work and unstable schedules was a significant source of stress for SSR. Additionally, interviews indicated a lack of resources from governments and NGOs being given to SSR and stress may have been exacerbated by limitations on the movement of aid and inequality in social support given to citizens when compared with SR [

21,

84,

85,

86,

87].

In contrast, some countries like Jordan provided MH support to SR within camps during the pandemic [

88], demonstrating the positive outcomes of the interventions. However, access to such support remains complex, with social protection often reserved for those who have previously contributed to the host country's social system prior to the pandemic aligning with pre-pandemic trends regarding refugees which had been prevalent in lower-/middle-income countries (LMICs) [

89]. Our participants were residing outside of formal refugee camps, predominantly in informal agricultural settlements or urban areas. As a result, they would not have been eligible for this support, which highlights an important gap in MH support. The exclusion of SSR from social provisions during the pandemic highlights the need for better collaboration between governments and NGOs to ensure effective support for MH and FI during global crises.

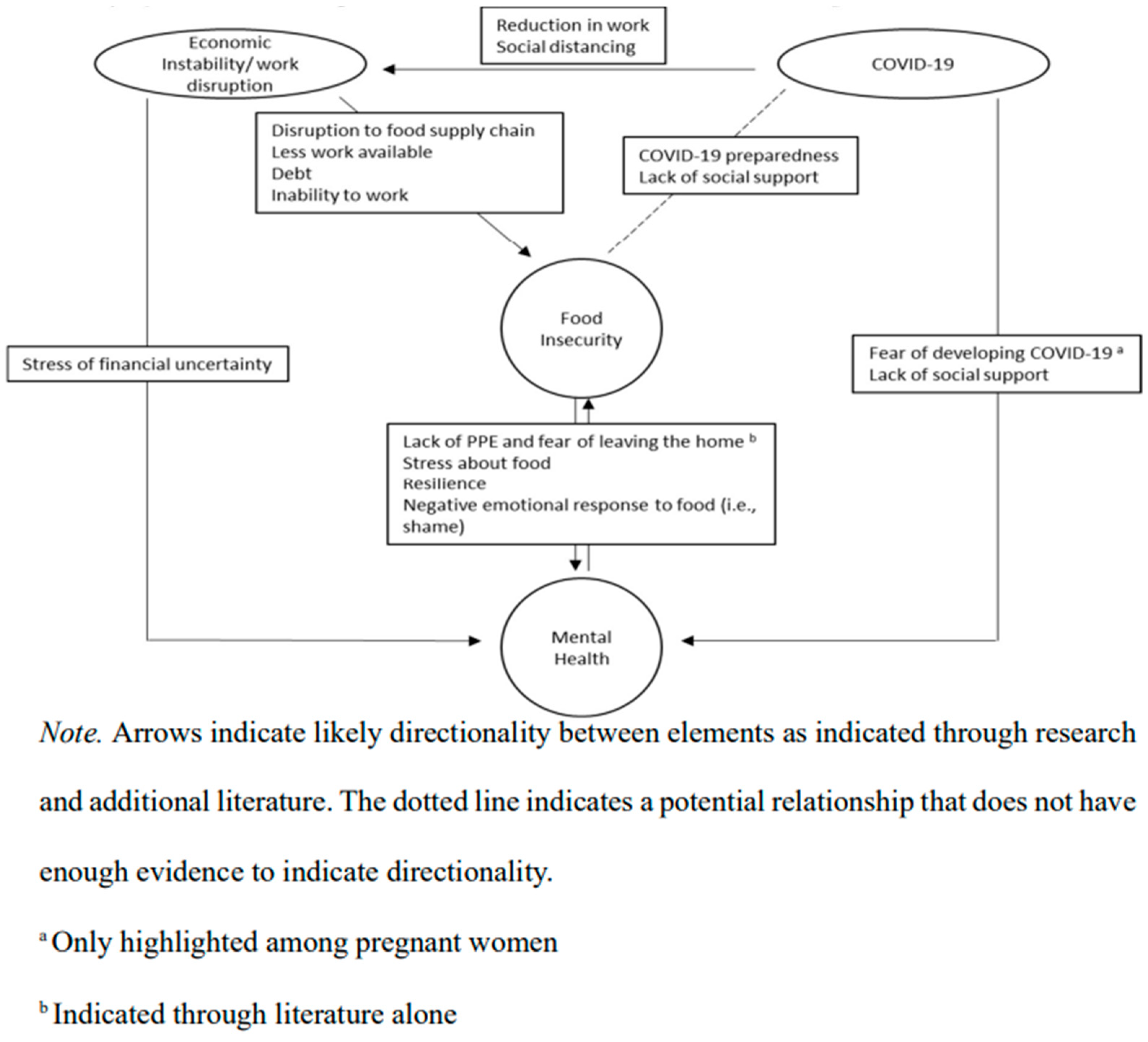

4.2.3. What Is the Relationship Between FI, MH, and COVID-19 Among SSR?

To some, COVID-19 was viewed as simply another issue to overcome, and one, relative to other circumstances, that had a limited impact on their lives. However, results and literature indicate that COVID-19 is impacting the lives of SSR regarding FI and MH (

Figure 5.).

The pandemic generated conditions that were inherently stressful for Syrian refugees and internally displaced SRR. These conditions arose primarily due to disruptions in employment opportunities, which limited their ability to work; inability to pay for food/ necessities due to economic disruptions; and fear of disease. The influence of COVID-19 beyond disease effects supports assertions of a syndemic being present among SSR and potentially exacerbating inequalities in social support. Common resilience patterns outlined in the Sociotype Ecological Framework were utilised by SSR participants but, there was no indication of whether these responses were significantly altered during the pandemic. Future longitudinal studies will be required to ascertain whether preferences for resilience patterns were present during the pandemic.

The MH findings revealed some of the most intriguing insights from the survey, particularly those emerging from responses to seemingly unrelated open-ended questions. In the final section of the survey, participants were asked about changes to household labour distribution. Many women expressed frustration over the increased workload caused by additional cleaning and children staying home due to school closures, while some men noted that they had taken on household chores. This section, positioned at the end of an hour-long interview conducted over WhatsApp, appeared to provide a space where respondents, having established trust with the interviewer, felt more comfortable sharing personal stress and concerns.

Interestingly, MH challenges also surfaced indirectly in the health section of the survey. While many adults reported good personal mental health, they used this section to highlight deteriorating MH in their children, such as experiencing nightmares. This disparity raises important questions about the cultural and social factors influencing self-disclosure. Adults may have found it less stigmatizing or easier to discuss their children’s MH struggles than their own, potentially reflecting cultural norms around self-presentation and emotional vulnerability. These findings highlight the value of indirect questioning and trust-building in revealing deeper insights into MH challenges in humanitarian contexts, suggesting the need for further exploration of effective strategies for MH assessment in these populations.

The findings of this study underscore that while the COVID-19 pandemic had a measurable impact on SSR populations, its effects were often eclipsed by pre-existing and worsening economic challenges, most notably inflation. These structural economic crises significantly shaped participants' experiences, with the pandemic primarily acting as a catalyst that exacerbated, rather than fundamentally altered, these persistent difficulties.

This observation aligns with broader research indicating that acute shocks, such as the pandemic or subsequent events like the earthquake, tend to have transient effects. These short-term disruptions, although impactful, are ultimately overshadowed by the enduring and compounding pressures of long-term economic instability and inflation. This finding is particularly salient and warrants emphasis in the conclusion, as it highlights the necessity for interventions and policies that address the systemic and chronic nature of economic challenges rather than focusing exclusively on immediate crises.

By recognizing the interplay between acute and chronic stressors, future research and policy can better address the root causes of vulnerability among SSR populations, ensuring more sustainable and effective responses to both immediate shocks and underlying structural issues.

5. Conclusions

COVID-19 has significantly impacted the FI and MH of SRR, primarily through social factors such as economic disruption and limitations on aid and governmental support. While COVID-19 did not moderate the relationship between FI and MH in this study, further research is needed to explore the role of emotional responses to food insecurity and their influence on MH outcomes. Additionally, future research should consider the protective role of religious gratitude in maintaining relatively higher MH scores among SRR.

Applied research is crucial to developing FI interventions that align with collective coping strategies, while also promoting self-esteem and resilience within this population. The factors affecting SRR are multifaceted and cannot be comprehensively addressed in a single study. Therefore, continued research is essential, and a mixed-methods approach is recommended to capture the nuanced experiences and data.

Moreover, it is important that future research be conducted in a bottom-up, collaborative manner, involving Syrian academics to ensure that SRR input is integrated at all levels of the research process—not just as participants. This approach will enhance the relevance and applicability of interventions and findings in addressing the complex challenges faced by SRR.

Limitations

The findings of this study are based on data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, which occurred five years ago. Since then, societal, economic, and health contexts may have evolved, potentially influencing the applicability of the conclusions drawn. However, despite the time elapsed, this study provides critical insights into the impact of pandemics on vulnerable populations that remain relevant for future health crises.

Author Contributions

Calia, C.: Conceptualization, Data Analysis, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing; El-Gayar, A.: Writing – Review & Editing; Boden, L.: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing; Zuntz, A-C.: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing; Abdullateef, S.: Writing - Review & Editing; Almashhor, E.: Writing - Review & Editing; Grant, L.: Writing – Review & Editing.

Funding

SFC-GCRF Covid-19 urgent call “From the FIELD: impacts of COVID-19 on lives and livelihoods of Syrians living in the Levant”. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The secondary research analysis conducted for this report received ethical approval from the University of Edinburgh, School of Health in Social Science Research Ethics, Integrity and Governance. Ethical approval for the initial study and analysis was obtained by the University of Edinburgh. Anonymised data was received by the authors on a platform supported by the University of Edinburgh; DataSync. The study adhered to ethical principles including all participants being aged above 18, voluntary participation and verbal consent to participate. Due to concerns of COVID-19, all interviews, surveys, and participant payments were conducted digitally. All participant data was anonymised and stored digitally in password-protected files.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article are available on a platform supported by the University of Edinburgh; DataSync.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of Jazmin Gentry, Joseph Baker, Joseph Burke, Joy Abihabib, Maria Azar and Tom Parkinson.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CARA |

Council for At-Risk Academics |

| CSI |

Coping Strategy Index |

| FI |

Food Insecurity |

| LMIC |

Lower-/Middle-Income Countries |

| MH |

Mental Health |

| MPCA |

Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance |

| NGO |

Non-governmental Organisation |

| PPE |

Personal Protective Equipment |

| SR |

Syrian Refugees |

| SSR |

Syrians and Syrian Refugees |

| SWEMWBS |

Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale |

| UNHCR |

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| USDA |

The United States Department of Agriculture |

| WHO |

World Health Organisation |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Spearman’s Rank Coefficient Correlation Matrix.

Table A1.

Spearman’s Rank Coefficient Correlation Matrix.

Table A2.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for Household responses to COVID against Mental Health, COVID-19 Awareness/ Preparedness and Food Insecurity.

Table A2.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for Household responses to COVID against Mental Health, COVID-19 Awareness/ Preparedness and Food Insecurity.

Table A3.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for Societal responses to COVID-19 against Mental Health, COVID-19 Preparedness/ Awareness and Food Insecurity.

Table A3.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for Societal responses to COVID-19 against Mental Health, COVID-19 Preparedness/ Awareness and Food Insecurity.

Figure A1.

Mind Map of the Theme ‘SSR Responses and Experience of Mental Health’.

Figure A1.

Mind Map of the Theme ‘SSR Responses and Experience of Mental Health’.

Figure A2.

Mind Map of the Theme ‘SSR Experiences and Responses Towards Food and Basic Necessities’.

Figure A2.

Mind Map of the Theme ‘SSR Experiences and Responses Towards Food and Basic Necessities’.

Figure A3.

Mind Map of the Theme ‘The Impact of COVID-19 and Other Social Issues on SSR’.

Figure A3.

Mind Map of the Theme ‘The Impact of COVID-19 and Other Social Issues on SSR’.

References

- Ayouni, I., Maatoug, J., Dhouib, W., Zammit, N., Fredj, S. B., Ghammam, R., & Ghannem, H. Effective public health measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19: a systematic review. BMC public health 2021, 21(1), 1015. [CrossRef]

- Kamalrathne, T., Jayasinghe, N., Fernando, N., Amaratunga, D., Haigh, R. Managing compound events in the COVID-19 era: A critical analysis of gaps, measures taken, and challenges, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2024, 112, 104765,. [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, E. The COVID-19 syndemic is not global: context matters. The Lancet 2020, 396(10264), 1731. [CrossRef]

- Singer, M., Bulled, N., Ostrach, B., Mendenhall, E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. The Lancet 2017. 389 (10072): 941–950. [CrossRef]

- Burke, J., Abdulateef, S., Boden, L., & Calia, C. (2020). Food Security and Mental Health Under the COVID-19 Syndemic. Humanitarian Practice Network. https://odihpn.org/blog/food-security-and-mental-health-under-the-covid-19-syndemic/ (accessed on 12.08.2024).

- Huizar, M. I., Arena, R., & Laddu, D. R. The global food syndemic: The impact of food insecurity, Malnutrition and obesity on the health span amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2021, 64, 107. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J. M., Seligman, H. K., & Weiser, S. D. Perspective: The Convergence of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Food Insecurity in the United States. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12(2), 287–290. [CrossRef]

- Rod, M. H., & Rod, N. H. Towards a syndemic public health response to COVID-19: Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2021, 49(1), 14–16. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, U. N., Rayamajhee, B., Mistry, S. K., Parsekar, S. S., & Mishra, S. K. A Syndemic Perspective on the Management of Non-communicable Diseases Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Frontiers in Public Health 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Horton, R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. The Lancet 2020, 396(10255), 874. [CrossRef]

- Bulled, N., & Singer, M. Conceptualizing COVID-19 syndemics: A scoping review. Journal of multimorbidity and comorbidity 2024, 14, 26335565241249835. [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Refugee Statistics. Refugee Data Finder. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/download?url=6CL09p (accessed on 12.08.2024).

- Faleh, H. M. H., & Ahmad, A.-Q. A. S. The impact of Syrian refugee crisis on neighboring countries. Вестник Рoссийскoгo Университета Дружбы Нарoдoв. Серия: Пoлитoлoгия 2018, 20(4).

- Gabiam, N. Humanitarianism, development, and security in the 21st century: Lessons from the Syrian refugee crisis. International Journal of Middle East Studies 2016, 48(2), 382– 386. [CrossRef]

- 3RP- Regional Strategic Overview, 2024 Available online: https://www.3rpsyriacrisis.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/3RP_RSO_2024_.pdf (accessed on 10.11. 2024).

- UNICEF. Child Food Poverty Report. A Nutrition Crisis in Early Childhood in Lebanon. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/lebanon/reports/child-food-poverty-report (accessed on 12.08.2024).

- UNWFP. Syria- World Food Programm. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/syria-emergency#:~:text=The%20country%20remains%20among%20the,risk%20of%20becoming%20food%20insecure (accessed on 12.08.2024).

- Karasapan, O. (2022). Syrian refugees in Jordan: A decade and counting. Brookings. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/syrian-refugees-in-jordan-a-decade-and-counting/ (accessed on 20.11.2024).

- UNICEF, Humanitarian Action for Children. Syrian refugees. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/100936/file/2021-HAC-Syrian-Refugees-May-Update.pdf (accessed on: 12.08.2024).

- Nabulsi, D., Ismail, H., Hassan, F. A., Sacca, L., Honein-AbouHaidar, G., & Jomaa, L. Voices of the vulnerable: Exploring the livelihood strategies, coping mechanisms and their impact on food insecurity, health and access to health care among Syrian refugees in the Beqaa region of Lebanon. PLoS ONE 2020, 15(12), e0242421. [CrossRef]

- Sawaya, T., Ballouz, T., Zaraket, H., & Rizk, N. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in the Middle East: A Call for a Unified Response. Frontiers in Public Health 2020, 8, 209. [CrossRef]

- Arciniegas Guaneme, I., Guerisoli, E., Guyot, L., & Kallergis, A. (2021). COVID-19 and Forcibly Displaced People: Addressing the impacts and responding to the challenges. Reference Paper for the 70th Anniversary of the 1951 Refugee Convention. The New School for Social Research. Prepared for UNHCR. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/people-forced-to-flee-book/ (accessed on: 12.08.2024).

- Lupieri, S. Refugee Health During the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Review of Global Policy Responses. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 2021, 14, 1378. [CrossRef]

- Klema, M. Precarious Labour under Lockdown. Available online: https://onehealthfieldnetwork.com/refugee-labour-under-lockdown (accessed on: 12.08.2024).

- USDA Economic Research Service. Definitions of Food Security. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-theus/definitions-of-food-security.aspx (accessed on: 12.08.2024).

- Clemens, M., Huang, C., & Graham, J. (2018). The Economic and Fiscal Effects of Granting Refugees Formal Labor Market Access (No. 496). Available online: www.cgdev.orgwww.cgdev.org (accessed: 22.08.2024).

- Marbach, M., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. The long-term impact of employment bans on the economic integration of refugees. Science Advances 2018, 4(9), eaap9519. [CrossRef]

- UNWFP (2024). Syria- World Food Programm. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/syria-emergency#:~:text=The%20country%20remains%20among%20the,risk%20of%20becoming%20food%20insecure (accessed on: 22.08.2024).

- Tiltnes, Å. A., Zhang, H., & Pedersen, J. (2019). The living conditions of Syrian refugees in Jordan. Available online: https://www.fafo.no/zoo-publikasjoner/fafo-rapporter/the-living-conditions-of-syrian-refugees-in-jordan (accessed: 22.08.2024).

- Peng, W., Dernini, S., & Berry, E. M. Coping With Food Insecurity Using the Sociotype Ecological Framework. Frontiers in Nutrition 2018, 5(107). [CrossRef]

- Zuntz, A., Klema, M., Abdullateef, S., Mazeri, S., Alnabolsi, S. F., Alfadel, A., Abi-Habib, J., Azar, M., Calia, C., Burke, J., Grant, L., & Boden, L. Syrians’ only option – Rethinking unfree labour through the study of displaced agricultural workers in the Middle East. Journal of Modern Slavery 2022, 7(2): 10-32. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ilr.12348.

- Daher, S. K. Food and nutrition security status of Syrian refugees and their host communities in Lebanon: the case of Akkar. Doctoral Dissertation. American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon, 2016.

- Talhouk, R., Montague, K., Jensen, R. B., Holloway, R., Coles-Kemp, L., Balaam, M., Garbett, A., Ghattas, H., Araujo-Soares, V., & Ahmad, B. Food Aid Technology: The Experience of a Syrian Refugee Community in Coping with Food Insecurity. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact 2020, 4(CSCW2). [CrossRef]

- Sales, R. The deserving and the undeserving? Refugees, asylum seekers and welfare in Britain. Critical Social Policy. Sage 2002, 22,(3). [CrossRef]

- Jamaluddine, Z., Irani, A., Moussa, W., Mokdad, R. Al, Chaaban, J., Salti, N., & Ghattas, H. The Impact of Dosage Variability of Multi-Purpose Cash Assistance on Food Security in Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Current Developments in Nutrition 2020, 4(Supplement_2), 846–846. [CrossRef]

- Krafft, C., Sieverding, M., Salemi, C., & Keo, C. Syrian refugees in Jordan: Demographics, livelihoods, education, and health. Economic Research Forum Working Paper Series 2018, 1184. Available online: https://erf.org.eg/publications/syrian-refugees-in-jordan-demographics-livelihoods-education-and-health/ (accessed on: 02.09.2024).

- Ejiohuo, O., Onyeaka, H., Unegbu, K. C., Chikezie, O. G., Odeyemi, O. A., Lawal, A., & Odeyemi, O. A. Nourishing the Mind: How Food Security Influences Mental Wellbeing. Nutrients 2024, 16(4), 501. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J., Ker, S., Archer, D., Gilbody, S., Peckham, E., & Hardman, C. A. Food insecurity and severe mental illness: understanding the hidden problem and how to ask about food access during routine healthcare. BJPsych Advances 2023, 29(3), 204–212. doi:10.1192/bja.2022.33.

- Cantekin, D. Syrian Refugees Living on the Edge: Policy and Practice Implications for Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing. International Migration 2019, 57(2), 200– 220. [CrossRef]

- Kamelkova, D. Food insecurity and its association with mental health among Syrian refugees resettled in Norway. Master’s thesis, The University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2021.

- Karaman, M. A., & Ricard, R. J. Meeting the mental health needs of Syrian refugees in Turkey. The Professional Counselor 2016, 6(4), 318. http://dx.doi.org/10.15241/mk.6.4.318.

- M’zah, S., Lopes Cardozo, B., & Evans, D. P. Mental Health Status and Service Assessment for Adult Syrian Refugees Resettled in Metropolitan Atlanta: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2019, 21(5), 1019–1025. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G., Ventevogel, P., Jefee-Bahloul, H., Barkil-Oteo, A., & Kirmayer, L. J. Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 2016, 129–141. [CrossRef]

- Bruening, M., Dinour, L. M., & Rosales Chavez, J. B. Food insecurity and emotional health in the USA: a systematic narrative review of longitudinal research. Public Health Nutrition 2017, 20(17), 3200–3208. [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M., Andrade, L., Packull-McCormick, S., Perlman, C. M., Leos-Toro, C., & Kirkpatrick, S. I. Food insecurity and mental health among females in high income countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15(7). [CrossRef]

- Narvaez, A. & Goudie, S. (2024). Pushed to the brink: the UK’s interlinked mental health and food insecurity crises. The Food Foundation. Available online: https://foodfoundation.org.uk/publication/pushed-brink-link-between-food-insecurity-and-mental-health (accessed on: 02.09.2024).

- Pourmotabbed, A., Moradi, S., Babaei, A., Ghavami, A., Mohammadi, H., Jalili, C., Symonds, M. E., & Miraghajani, M. Food insecurity and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutrition 2020, 23(10), 1778–1790. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J., Parker, M., Tekwe, C., & Bidulescu, A. Food insecurity and mental health among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from National Health Interview Survey, 2020-2021. Journal of affective disorders 2024, 356, 707–714. [CrossRef]

- Talham, C. J., & Williams, F. Household food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with anxiety and depression among US- and foreign-born adults: Findings from a nationwide survey. Journal of affective disorders 2023, 336, 126–132. [CrossRef]

- Fang, D., Thomsen, M. R., & Nayga, R. M., Jr. The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC public health 2021, 21(1), 607. [CrossRef]

- Elgar, F. J., Pickett, W., Pförtner, T.-K., Gariépy, G., Gordon, D., Georgiades, K., Davison, C., Hammami, N., MacNeil, A., Da Silva, M. A., & Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R. Relative food insecurity, mental health and wellbeing in 160 countries. Social Science & Medicine 2020, 268. [CrossRef]

- Calia C, Chakrabarti A, Sarabwe E and Chiumento A. Maximising impactful and locally relevant mental health research: ethical considerations. Wellcome Open Research 2022, 7:240. [CrossRef]

- Zuntz, A., Klema, M., Abdullateef, S., Mazeri, S., Alnabolsim, S., Alfadel, A., Abi-habib, J., Azar, M., Calia, C., Burke, J., Grant, L., and Boden, L. Syrian refugee labour and food insecurity in Middle Eastern agriculture during the early COVID-19 pandemic. International Labour Review 2021, 161(2), 245-266. [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, R. E., Moshabela, M., & Bob, U. Adapting the Coping Strategies Index to measure food insecurity in the rural district of iLembe, South Africa. Food, Culture and Society 2018, 22(1), 95–110. [CrossRef]

- Fat, L. N., Scholes, S., Boniface, S., Mindell, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the Health Survey for England. Quality of Life Research 2017, 26, 1129–1144. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, D., & Caldwell, R. (2008). The Coping Strategies Index Field Methods Manual (WFP & CARE (eds.); Second). Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc (CARE). Available online: https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/manual_guide_proced/wfp2 11058.pdf (accessed on: 18.09.2024).

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2007, 5(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal K. NVivo. JMLA 2022, 110(2), 270–272. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3(2), 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 2021, 21(1), 37–47. [CrossRef]

- Pringle, J., Drummond, J., McLafferty, E., & Hendry, C. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: A discussion and critique. Nurse Researcher 2011, 18(3), 20–24. [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H. G. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie 2009, 54(5), 283–291. [CrossRef]

- Levin, J. Religion and mental health: theory and research. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 2010, 7(2), 102–115. [CrossRef]

- Papaleontiou-Louca, E. Effects of Religion and Faith on Mental Health. New Ideas in Psychology 2021, 60. [CrossRef]

- Sandage, S., Hill, P., & Vaubel, D. Generativity, relational spirituality, gratitude, and mental health: Relationships and pathways. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2011, 21(1), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Aghababaei, N., & Tabik, M. T. Gratitude and mental health: differences between religious and general gratitude in a Muslim context. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 2013, 16(8), 761–766. [CrossRef]

- Syam, H., Venables, E., Sousse, B., Severy, N., Saavedra, L., & Kazour, F. “With every passing day I feel like a candle, melting little by little.” experiences of long-term displacement amongst Syrian refugees in Shatila, Lebanon. Conflict and Health 2019, 13(1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Umer, M., & Lazarte Elliot, D. Being Hopeful: Exploring the Dynamics of Posttraumatic Growth and Hope in Refugees. Journal of Refugee Studies 2019, 34(1), 953–975. [CrossRef]

- Pasha, S. Developmental Humanitarianism, Resilience and (Dis)Empowerment In A Syrian Refugee Camp. Journal of International Development 2019, 32, 244–259. [CrossRef]

- Fratzke, S. Engaging communities in refugee protection: The potential of private sponsorship in Europe. Migration Policy Institute Europe 2017, 9. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/PrivateSponsorshipEurope-Fratzke_FINALWEB.pdf (accessed on 25.08.2024).

- Yohani, S., Kirova, A., Georgis, R., Gokiert, R., Mejia, T., & Chiu, Y. Cultural Brokering with Syrian Refugee Families with Young Children: An Exploration of Challenges and Best Practices in Psychosocial Adaptation. Journal of International Migration and Integration 2019, 20(4), 1181–1202. [CrossRef]

- Glanville, L. Resilience and Domination: Resonances of Racial Slavery in Refugee Exclusion. International Studies Quarterly 2024, 68(3), sqae116. [CrossRef]

- Bargués, P., & Schmidt, J. Resilience and the Rise of Speculative Humanitarianism: Thinking Difference through the Syrian Refugee Crisis. Millennium 2021, 49(2), 197-223. [CrossRef]

- Bahar Özvarış, Ş., Kayı, İ., Mardin, D., Sakarya, S., Ekzayez, A., Meagher, K., & Patel, P. COVID-19 barriers and response strategies for refugees and undocumented migrants in Turkey. Journal of Migration and Health 2020, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Hopman, J., Allegranzi, B., & Mehtar, S. Managing COVID-19 in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA 2020a, 323(16), 1549–1550. [CrossRef]

- Khoury, P., Azar, E., & Hitti, E. COVID-19 Response in Lebanon: Current Experience and Challenges in a Low-Resource Setting. JAMA 2020, 324(6), 548–549. [CrossRef]

- Nott, D. The COVID-19 response for vulnerable people in places affected by conflict and humanitarian crises. The Lancet 2020, 395(10236), 1532–1533. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S., Bherwani, H., Gulia, S., Vijay, R., & Kumar, R. Understanding COVID-19 transmission, health impacts and mitigation: timely social distancing is the key. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2020, 23(5), 6681–6697. [CrossRef]

- Reimold, A. E., Grummon, A. H., Taillie, L. S., Brewer, N. T., Rimm, E. B., & Hall, M. G. Barriers and facilitators to achieving food security during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preventive Medicine Reports 2021, 101500. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C. B. Measuring Food Security. Science 2010, 327, 825–828. [CrossRef]

- Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., & Griffiths, R. R. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2020, 15, 39–45. [CrossRef]

- Erokhin, V., & Gao, T. Impacts of COVID-19 on Trade and Economic Aspects of Food Security: Evidence from 45 Developing Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(16), 5775. [CrossRef]

- Ma, N. L., Peng, W., Soon, C. F., Noor Hassim, M. F., Misbah, S., Rahmat, Z., Yong, W. T. L., & Sonne, C. Covid-19 pandemic in the lens of food safety and security. Environmental Research 2021, 193, 110405. [CrossRef]

- Allahi, F., Fateh, A., Revetria, R., & Cianci, R. The COVID-19 epidemic and evaluating the corresponding responses to crisis management in refugees: a system dynamic approach. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management 2021, 11(2), 347–366. [CrossRef]

- Dempster, H., Ginn, T., Graham, J., Guerrero Ble, M., Jayasinghe, D., & Shorey, B. 2020. Locked Down and Left Behind: The Impact of COVID-19 on Refugees’ Economic Inclusion. Policy Paper 179. Center for Global Development, Refugees International, and International Rescue Committee, 1–44. Available online: https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/4994/locked-down-left-behindrefugees-economic-inclusion-covid.pdf (accessed on: 25.08.2024).

- Sumner, A., Hoy, C., & Ortiz-Juarez, E. 2020. Estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty. UNU-WIDER. Available online: https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2020/800-9 (accessed on: 25.08.2024). [CrossRef]

- Woertz, E. COVID-19 in the Middle East and North Africa: Reactions, Vulnerabilities, Prospects 2020. (GIGA Focus Nahost, 2). Hamburg: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies - Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien, Institut für Nahost-Studien. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-67334-7 (accessed on: 25.08.2024).

- El-Khatib, Z., Al Nsour, M., Khader, Y. S., & Abu Khudair, M. Mental health support in Jordan for the general population and for the refugees in the Zaatari camp during the period of COVID-19 lockdown. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2020, 12(5), 514. [CrossRef]

- Hagen-Zanker, J., & Both, N. Social protection provisions to refugees during the Covid-19 pandemic Lessons learned from government and humanitarian responses 2021, (No. 612). Available online: https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/ODI_Refugees_final.pdf (accessed on: 28.08.2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).