Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) present a serious global health challenge. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), NCDs are responsible for approximately 41 million deaths annually, accounting for 74% of all deaths globally [

1]. Adding to the mortality, the morbidity associated with NCDs severely impacts the quality of life of millions due to long-term disability and exerts immense pressure on the healthcare system. These facts underscore an urgent need for comprehensive strategies to combat NCDs and necessitate robust, sustained and coordinated international responses. At the helm of international efforts, the WHO developed the Global Action Plan and Control of NCDs 2013-2030 [

2]. This strategic declaration is designed to address the prevention and reduction of morbidity, mortality, and the myriad socioeconomic impacts related to NCDs with an ambitious goal of a 25% relative reduction in premature mortality from NCDs by 2025. In addition, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3, which focuses on ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all ages, is particularly relevant to the health challenges faced by FDP [

3]. It sets a clear target for reducing one-third premature mortality from NCDs by 2030, obliging member states to reduce risk factors for NCDs, such as tobacco consumption and substance abuse, and achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

Despite these international initiatives, progress faces significant challenges, particularly due to the serious disparities of NCDs burdens across economic divides. High-income countries (HICs) have experienced a noteworthy decline in the disease burden since the 1980s, thanks to advanced healthcare systems and effective public health policies. However, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bear the brunt of the impact, with over 75% of global NCDs-related deaths occurring in these regions [

1]. This disparity is primarily attributed to a confluence of risk factors prevalent in LMICs, including unhealthy diets, high consumption of tobacco and alcohol, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and limited political will to address the issues [

2,

4,

5].

The challenges are further compounded in the settings of humanitarian crises, such as among forcibly displaced people (FDP). Recent statistics about FDP revealed a concerning trend: the number worldwide has surged dramatically over the last decades, surpassing 100 million in 2022 [

6]. Furthermore, the data clarifies a disturbing reality where over three-quarters of these displaced individuals remain in protracted displacement situations, with the average duration extending beyond 20 years [

7]. The long-term displacement presents serious challenges for managing NCDs, as healthcare systems are often overwhelmed by immediate demands such as infectious diseases and trauma. In these contexts, the chronic nature of NCDs is frequently neglected, and access to essential medications and ongoing care is severely limited. In addition to the direct health challenges, displaced populations face socio-economic barriers that further complicate NCD management. Displacement often disrupts livelihoods, limits access to clean water and nutrition, and leads to overcrowded living conditions, all of which contribute to the worsening of chronic diseases. Moreover, the stress and trauma associated with displacement can exacerbate conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, creating a vicious cycle of worsening health outcomes. Despite the evident need for targeted interventions in these populations, the epidemiology of NCDs among FDP remains poorly understood.

This research addresses these gaps by conducting a systematic mapping review of the literature on NCDs among FDP. Given the limited availability of high-quality empirical studies, this mapping review aims to synthesize and categorize existing evidence, providing a comprehensive overview of the current state of research. The primary goal is to aggregate and categorize available evidence, creating meta-data to draw a global picture of NCDs among FDP. By systematically mapping the existing literature, the research seeks to provide an extensive overview of the current state of knowledge and the scale of research conducted to date. This comprehensive aggregation helps facilitate a clearer understanding of how NCDs are addressed in humanitarian settings, particularly in FDP.

In addition, the research seeks to underscore knowledge focuses that can implement secondary synthesis and identify knowledge gaps that need further investigation. By providing current research focuses and gaps in this issue, the research holds significant potential to guide future studies, shape health policies, and ultimately contribute to better health outcomes of FDP suffering from NCDs. Consequently, the systematic mapping review serves not only as an academic exercise but also as a vital step toward improving the health and well-being of FDP.

Methods

1.1. Methodological Framework

There is no standard methodological framework of systematic mapping reviews in the public health field as it is still an evolving method of evidence synthesis. To ensure the research quality, this study applied a methodology in environmental sciences and software engineering that follows the “same rigorous, objective, and transparent processes as do systematic reviews” [

8]. The systematic mapping review was structured into five distinctive stages: (1) defining the scope and research questions along with establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria, (2) conducting a comprehensive search for relevant evidence, (3) screening the gathered evidence for relevance, (4) coding the evidence based on the predefined definitions, and (5) synthesizing and presenting the findings.

1.1. Defining the Scope and Research Questions Along with Establishing Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study proposes six research questions (RQ) below to broaden and analyze data related to NCDs among FDP from multiple dimensions.

RQ1. Temporal trend: How much literature on NCDs among FDP has been published each year?

RQ2: Scientific evidence level: How much literature on NCDs among FDP has been published based on the scientific level of evidence defined by Melynk & Fineout-Overholt (2023)?

RQ3. Research domains: Which diseases and domains of medical interventions are prioritized in research on NCDs among FDP?

RQ4. Geographical areas: Which countries of FDP originated from and hosted in are the research focus on NCDs?

RQ5. Type of FDP: Which type of FDP and living environment are prioritized in research on NCDs among FDP

RQ6. Funding source: Which entities have provided financial support for research on NCDs among FDP?

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to ensure a systematic and objective approach to selecting studies for this mapping review. These criteria were based on six aspects: the target population of the study, the specific research domains relevant to NCDs among FDP, the study design adhered to criteria for the evidence level of “Evidence-based nursing care guidelines” (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2023), publication types, and language. These criteria allowed for a structured and evidence-informed assessment of the literature. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in

Table 1.

1.1. Conducting a Comprehensive Search for Relevant Evidence

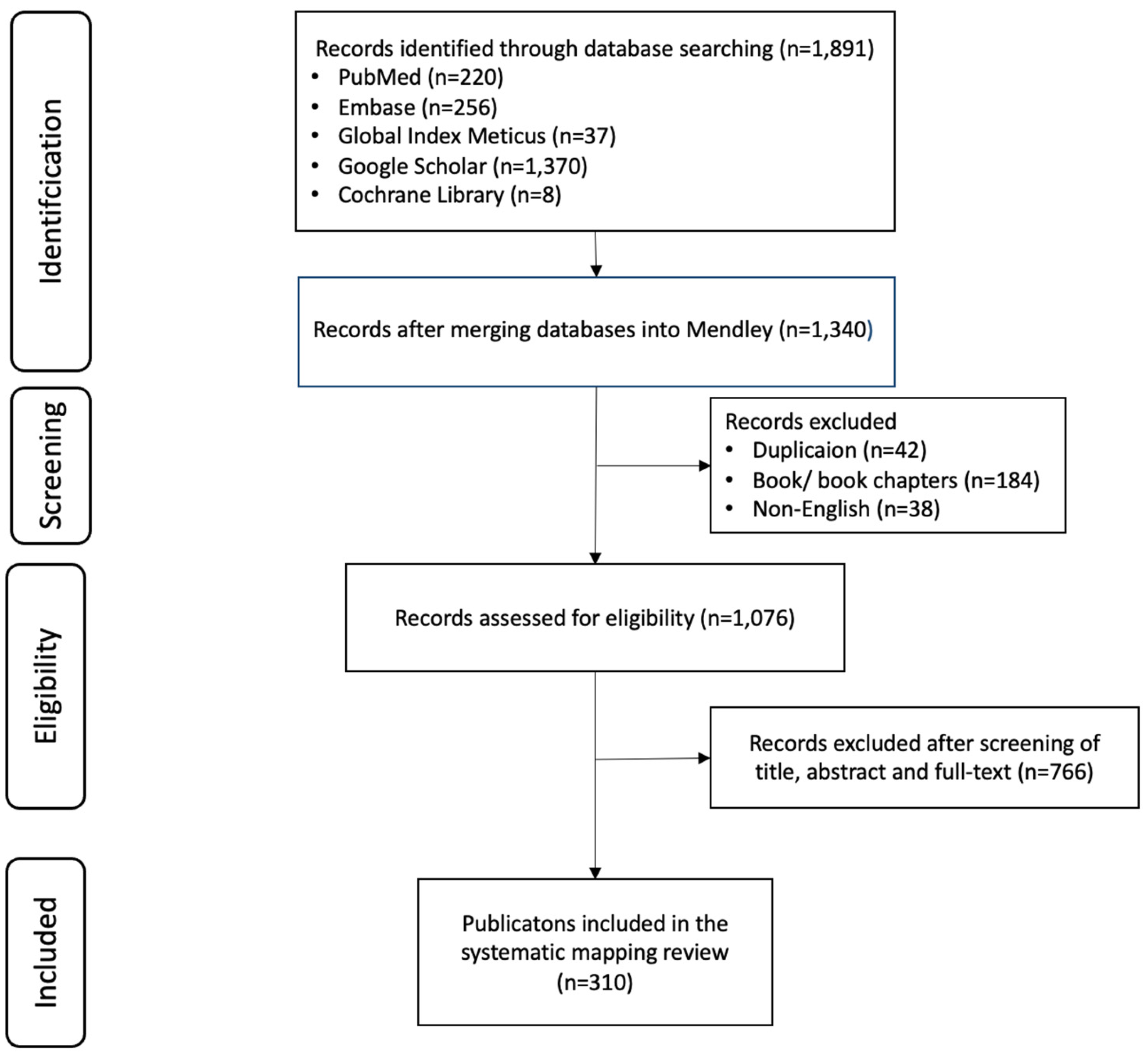

An extensive search strategy was enacted to systematically gather literature on NCDs among FDP. We interrogated five prominent electronic databases from November 22nd to December 8th, 2022: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Global Index Medicus and Google Scholar. The database selection was decided to capture the widest possible spectrum of research outputs, ranging from peer-reviewed articles to grey literature, ensuring the inclusivity of relevant studies.

Keywords were chosen for their relevance and frequency of use in the existing literature and were used in conjunction with filters to refine the relevance and accuracy of the search results.

1.1. Screening the Gathered Evidence for Relevance

All identified literature was imported into the Mendeley reference management software to facilitate systematic screening. Following the removal of duplicates, two authors independently screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of the collected literature, applying the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between the two authors were resolved through their discussion.

1.1. Coding the Evidence Based on the Predefined Definitions

The coding results were exactly compiled in Excel and subsequently analysed using Python 3. This systematic coding process was instrumental in structuring the evidence for in-depth analysis and synthesis, laying the groundwork for a comprehensive understanding of the current state of research on NCDs among FDP. Consequently, this process leads to insightful interpretations and substantive conclusions from the collected research data.

1.1. Synthesizing and Presenting the Findings

The coding of retrieved literature was conducted using nine key variables in line with the six research questions: year of publication, level of scientific evidence, target diseases, research domains, countries of origin and host, living environments, types of FDP, and funding sources.

Results

A total of 310 publications were extracted from 1,891 identified through a defined screening process (

Figure 1) (Additional file 1). Given the selected publications, the six research questions are answered as follows. The retrieved 310 publications are shown in Appendix A.

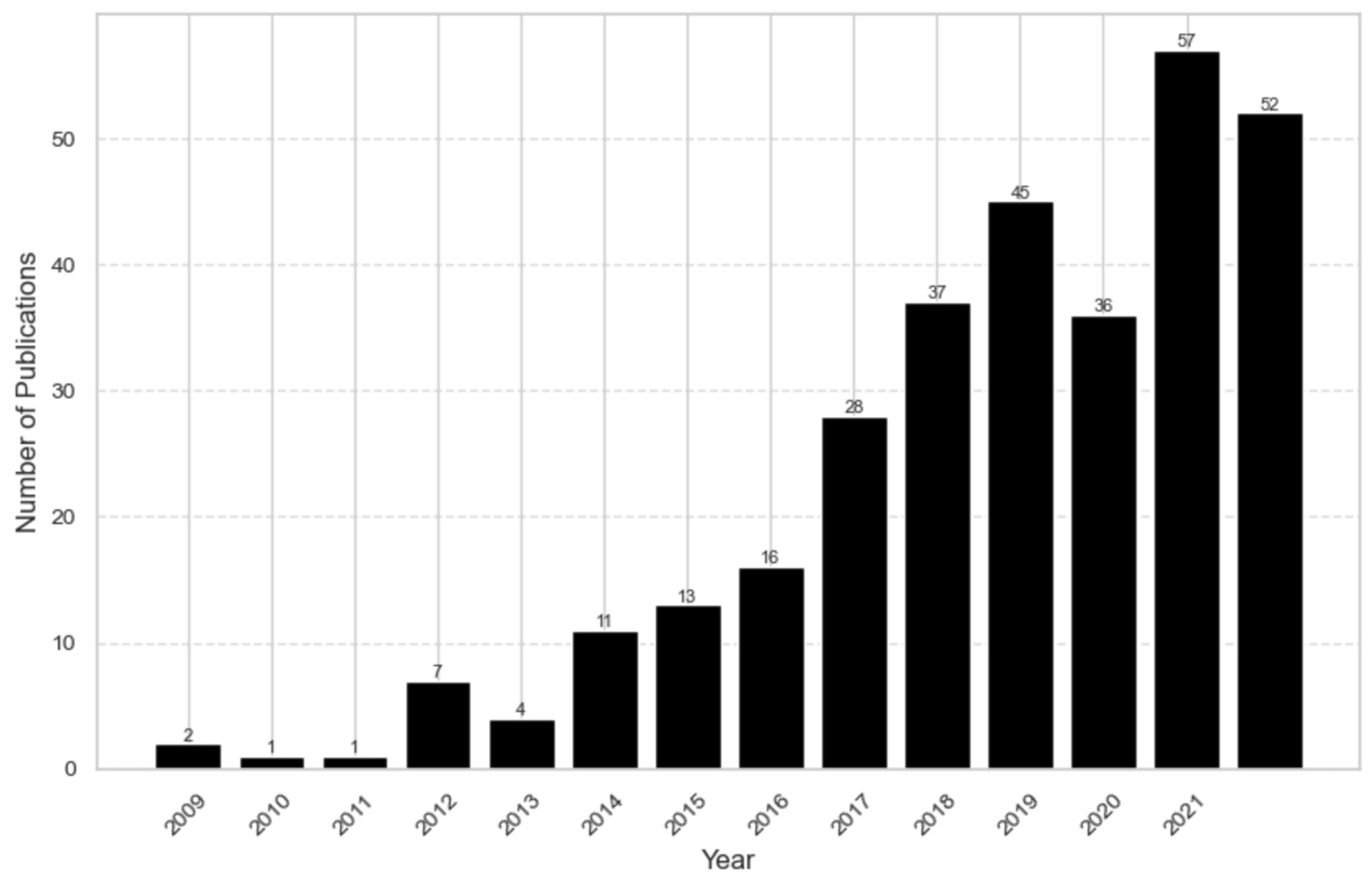

RQ1. Temporal trend: How much literature on NCDs among FDP has been published each year?

The first literature about NCDs among FDP was published in 2009 (

Figure 2). It was the WHO’s strategic plan for Palestinian refugees in the Gaza Strip. For several years, annual publications remained below ten; however, a growing trend has been shown since 2014. This trend became pronounced in 2017, with over 80% of the literature being published in the last five years.

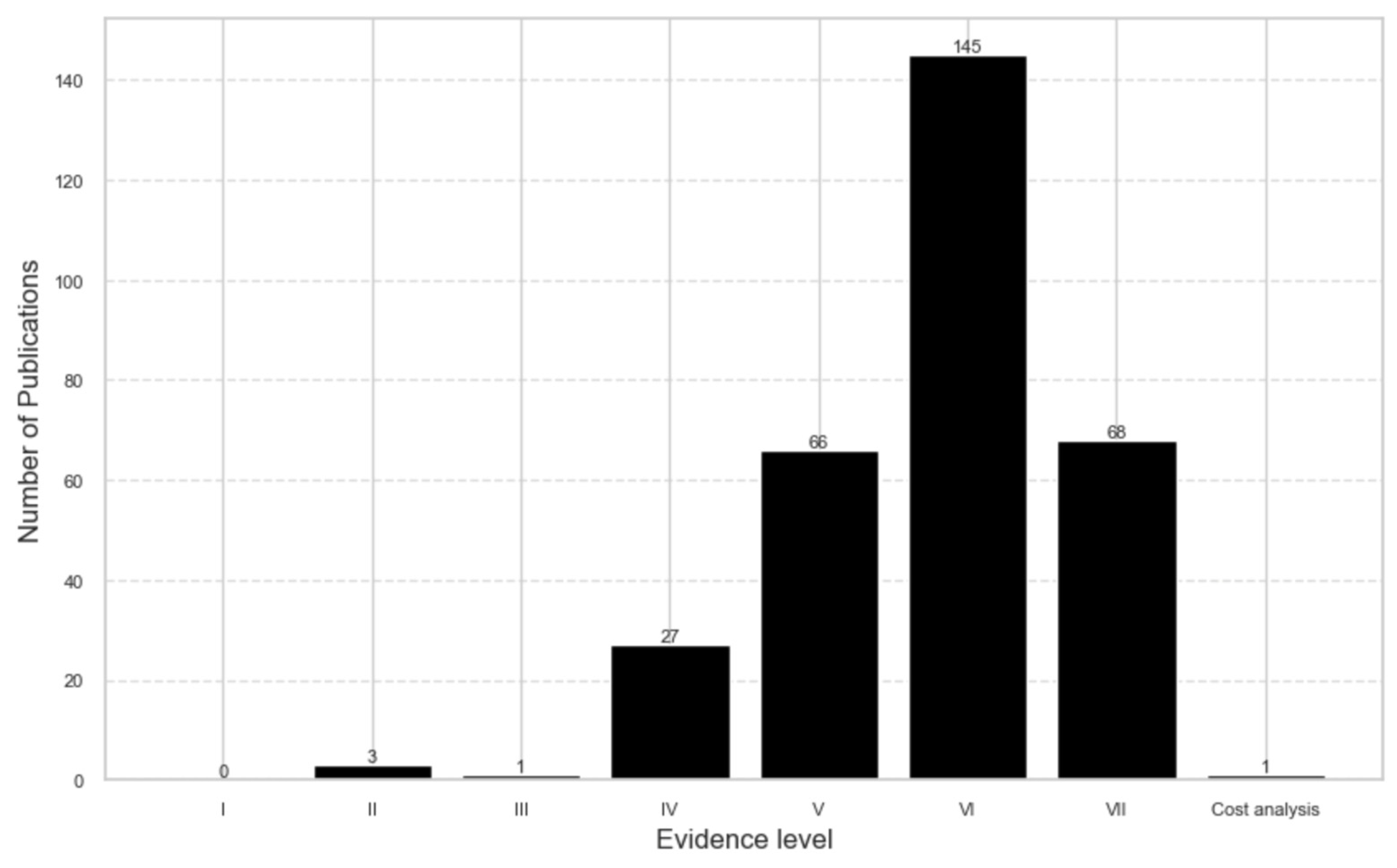

RQ2: Scientific evidence level: How much literature on NCDs among FDP has been published based on the scientific level of evidence defined by Melynk & Fineout-Overholt [

9]?

Approximately 70% of the retrieved literature fell into low evidence levels, VI or VII (

Figure 3). Notably, there were no publications at level I, and only a limited number were categorized as levels II and III. One publication was about retrospective cost analysis from provider perspectives.

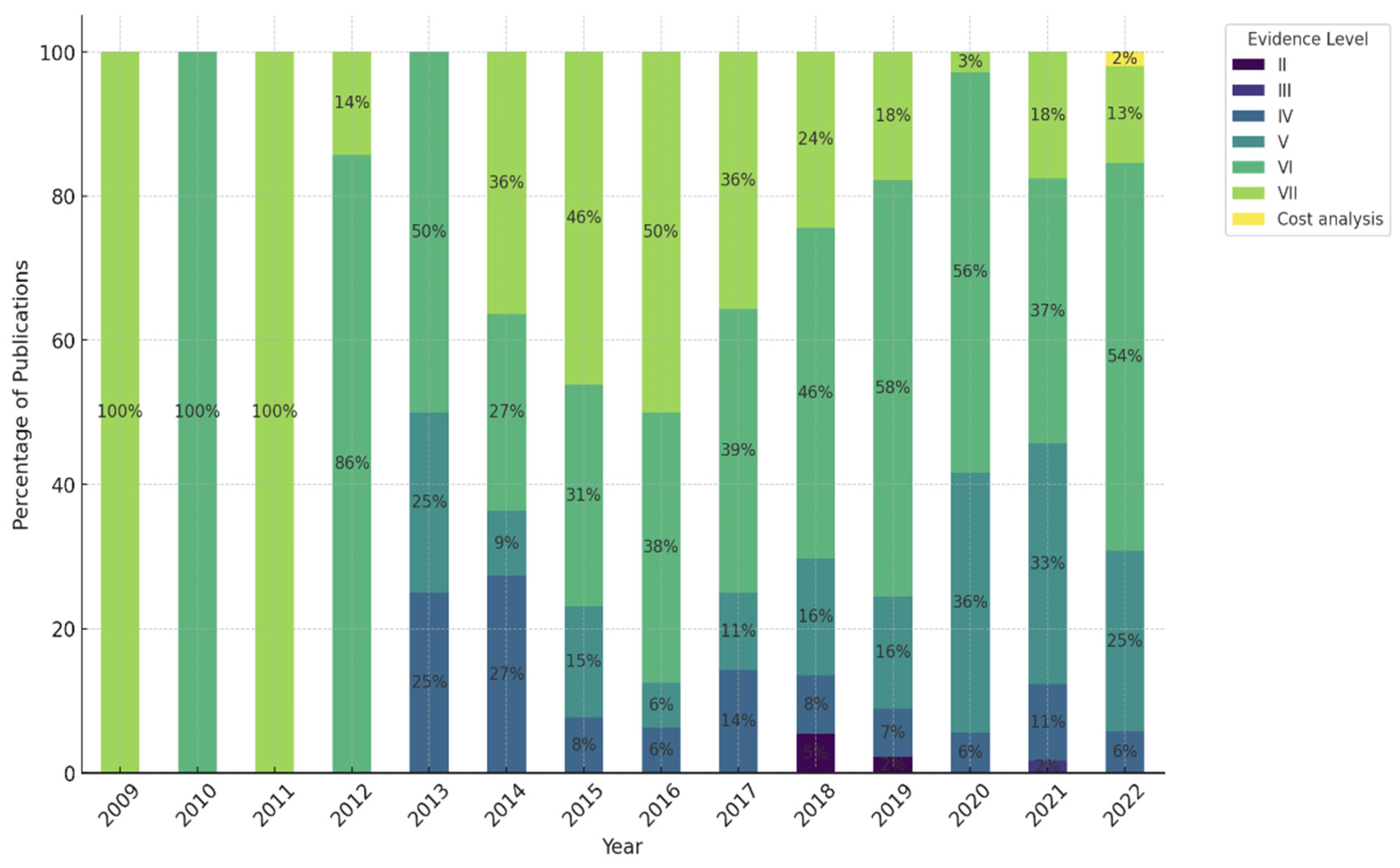

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of publications by evidence level over time. The result shows both consistency and changes. Evidence level VI, with notable constancy, continues to be the most represented category throughout the evaluation period. However, remarkable shifts are observed in the relative proportions of evidence levels V and VII. Evidence level VII was the dominant category until 2016; however, it shows an apparent decline trend after 2016. In contrast, publications at evidence level V have been increasing, especially from 2020 onward, and it has become the second most frequent category.

RQ3. Research domains: Which diseases and domains of medical interventions are the research focus on NCDs among FDP?

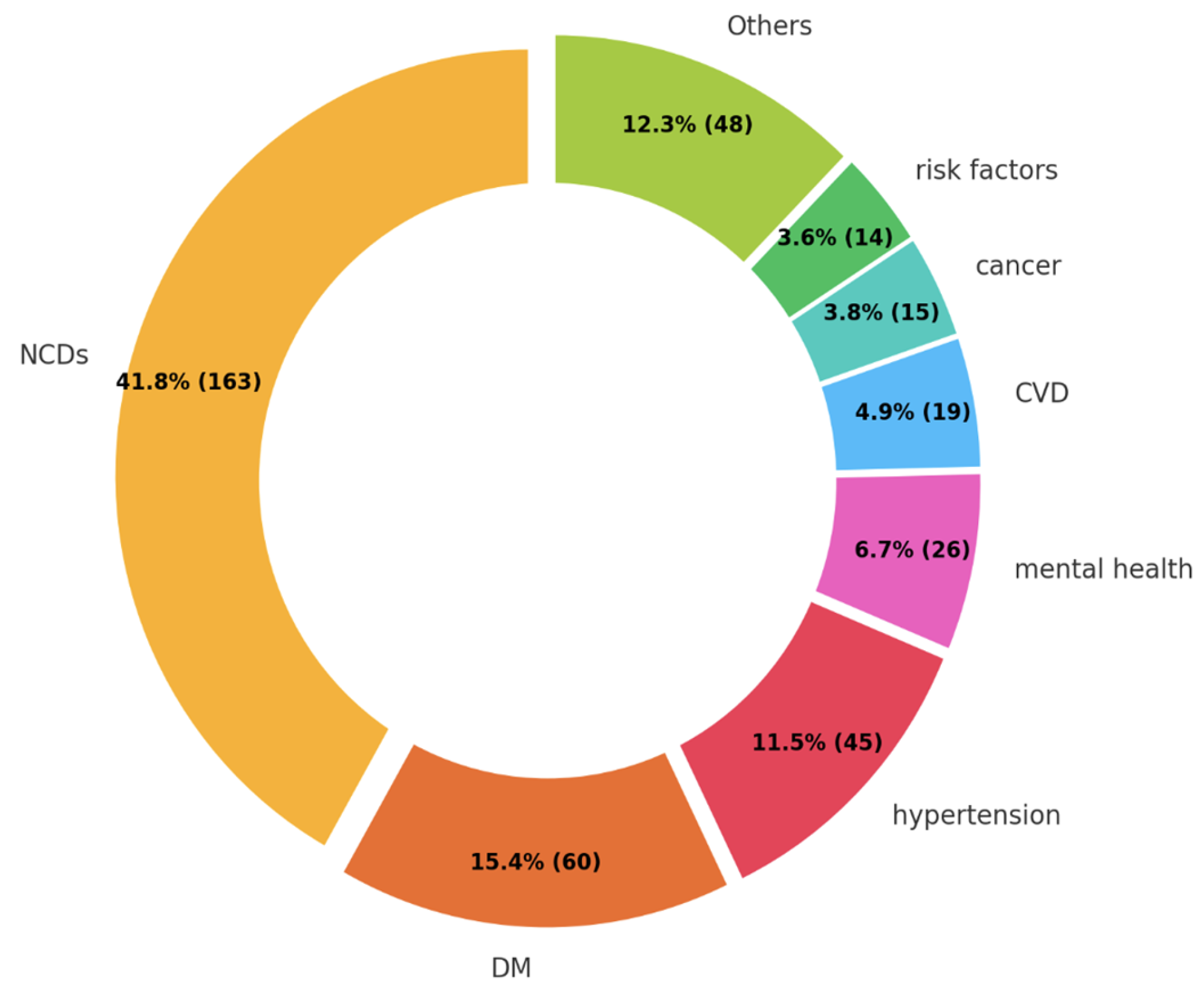

The majority of the research described a comprehensive overview of NCDs (41.8%) (

Figure 5). This result can be attributed to the high proportions of review articles (evidence level V) and expert opinions (evidence level VII) among the retrieved studies.

Among disease-specific research, DM (26.4%) and hypertension (19.8%) were the two most common focuses. The two diseases collectively comprised nearly half of the research targeting specific diseases. Subsequently, mental health (11.4%), CVD (8.4%), and cancer (6.6%) were studied; however, the number was limited.

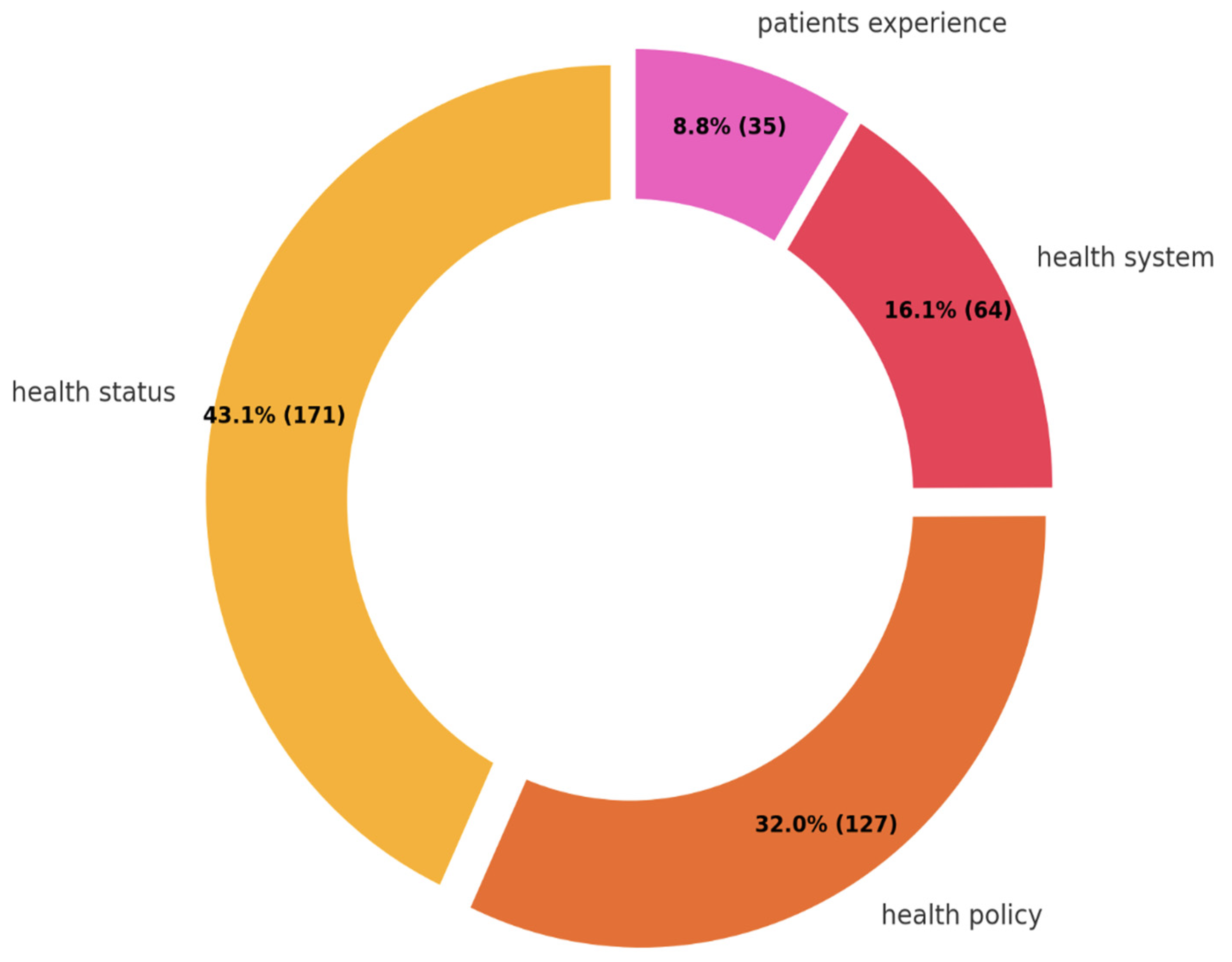

As for the research domain, health status and health policy were predominant, comprising 43.1% and 32.0%, respectively (

Figure 6). Compared to the two research focuses, less priority was given to patients’ experience (16.1%) and health system (8.8%).

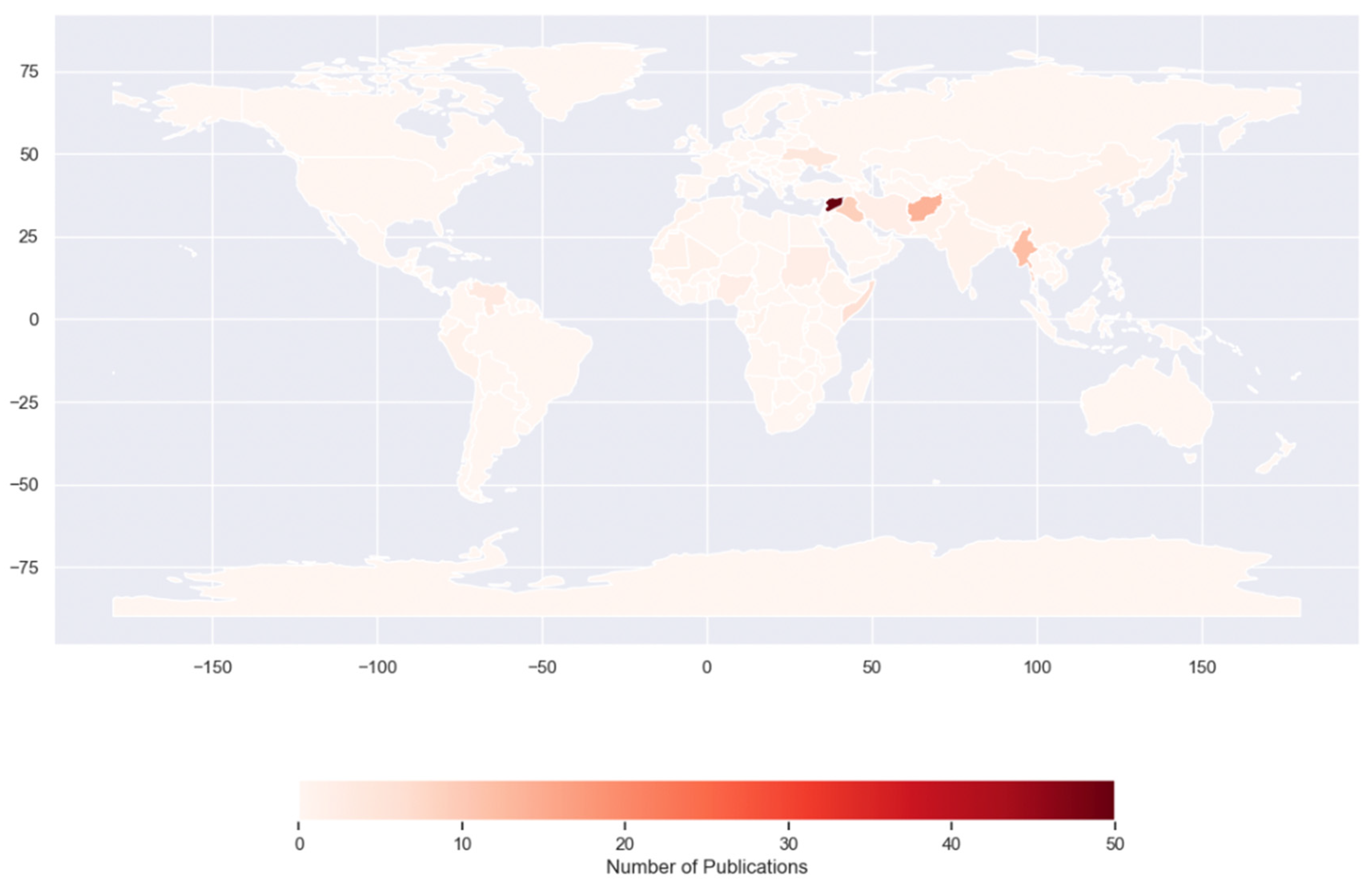

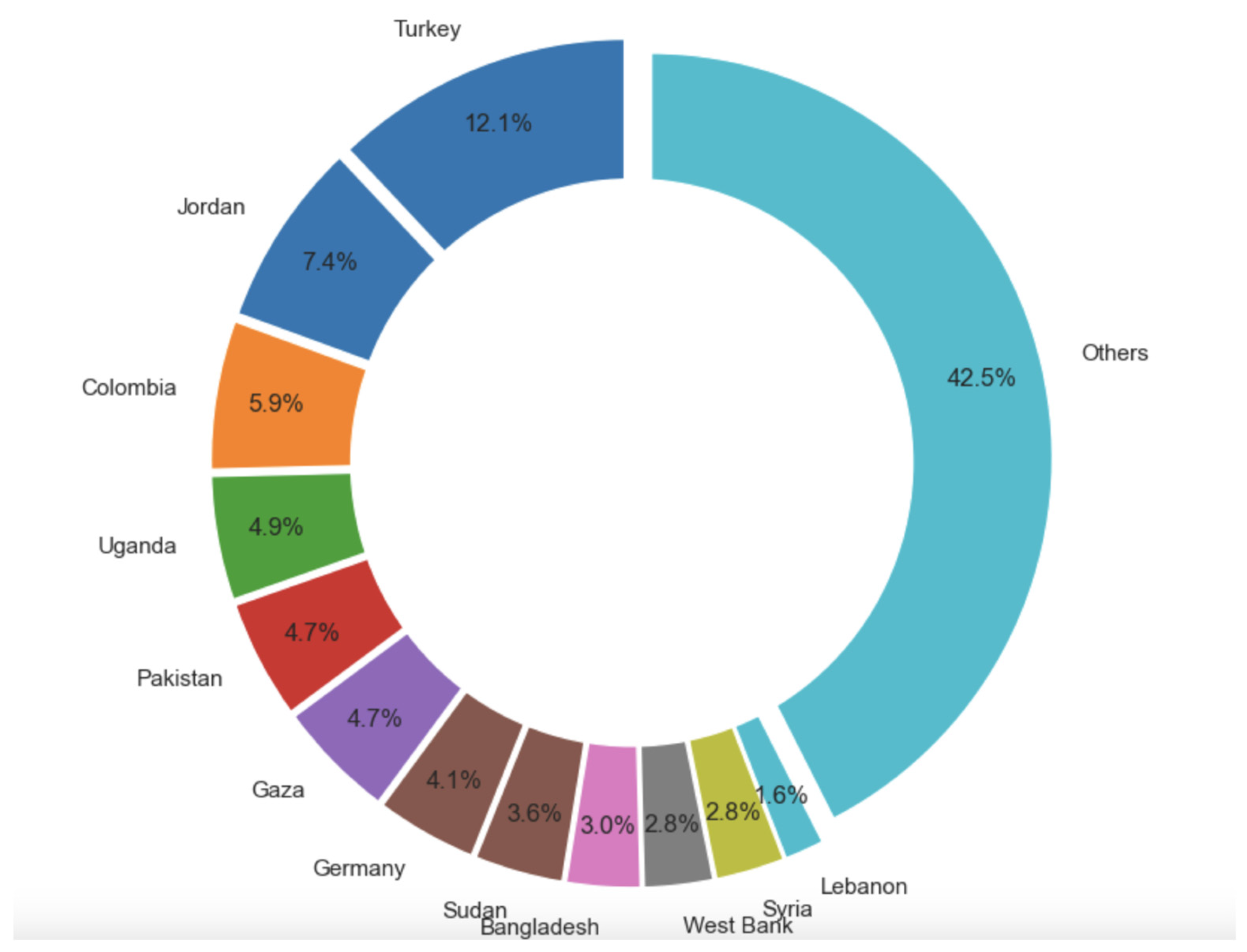

RQ4. Geographical areas: Which countries of FDP originated from and hosted in are the research focuses on NCDs?

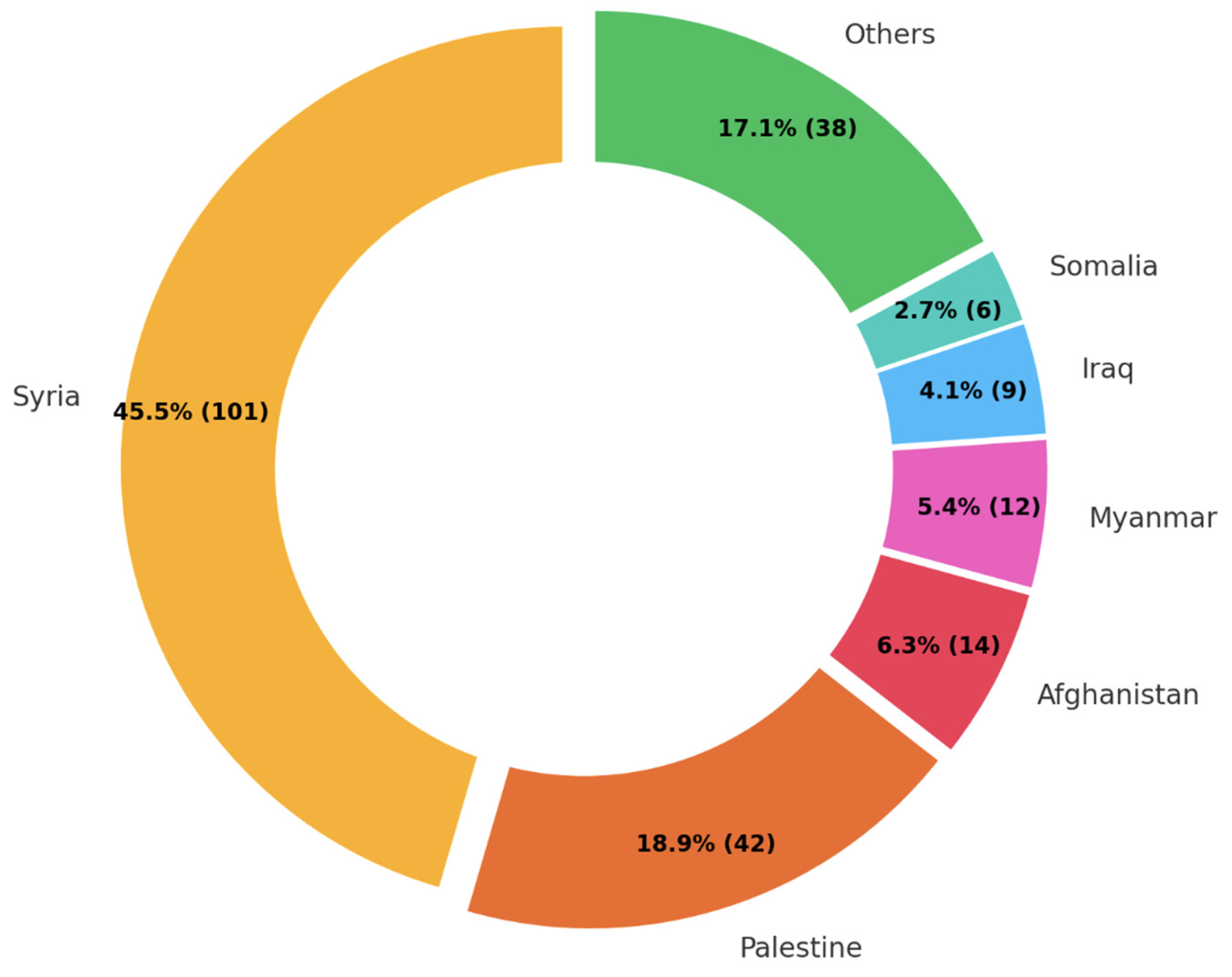

Among 222 publications defining the target countries of origin, almost half of the publications focused on Syria (45.5%), followed by Palestine (18.9%), Afghanistan (6.3%), and Myanmar (5.4%) (

Figure 7). The four countries accounted for more than three-quarters of the publications. Meanwhile, publications about Venezuela and South Sudan, the major countries of origin of FDP, were only three and one, respectively.

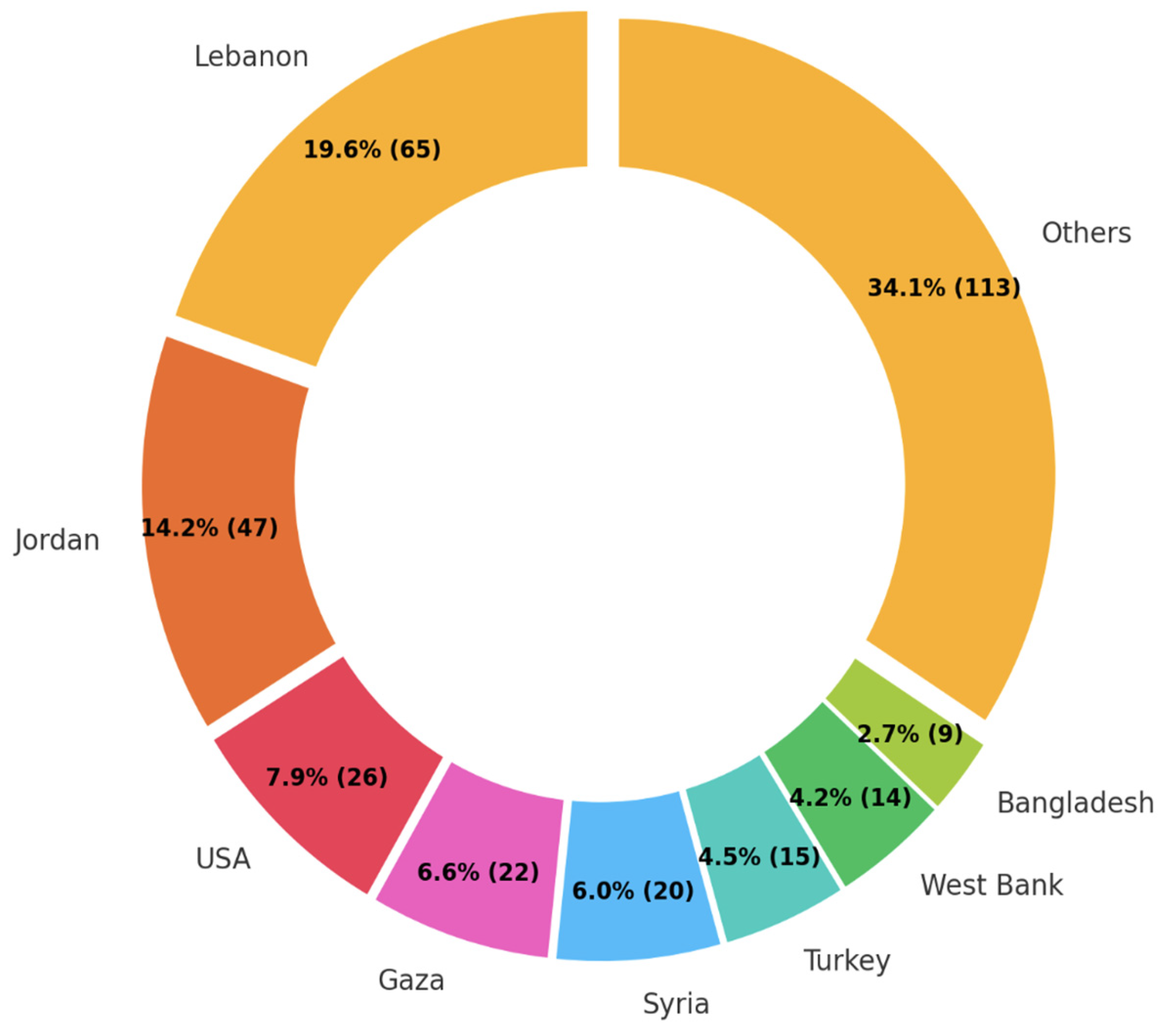

The target countries of the host were more diverse than those of origin (

Figure 8). However, among the top seven target countries, five (i.e., Lebanon, Jordan, Gaza, Syria, and West Bank) are under the UNRWA management. As Turkey is the main host country of Syrian refugees, the result is compatible with that of countries of origin. Interestingly, the USA ranked third among host countries, despite not being a primary host country for FDP.

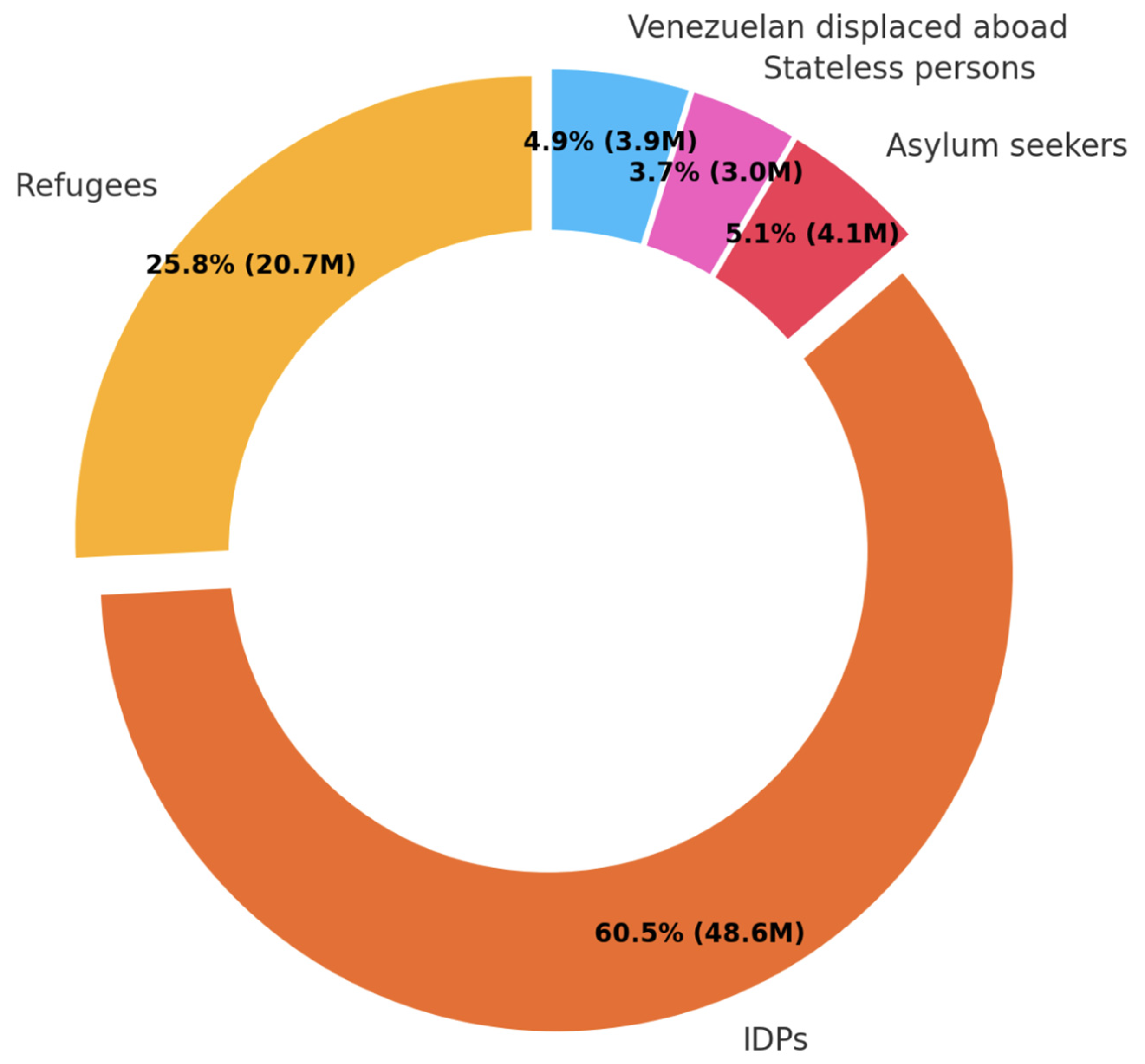

RQ5. Type of FDP: Which type of FDP and living environment are the research focus on NCDs among FDP

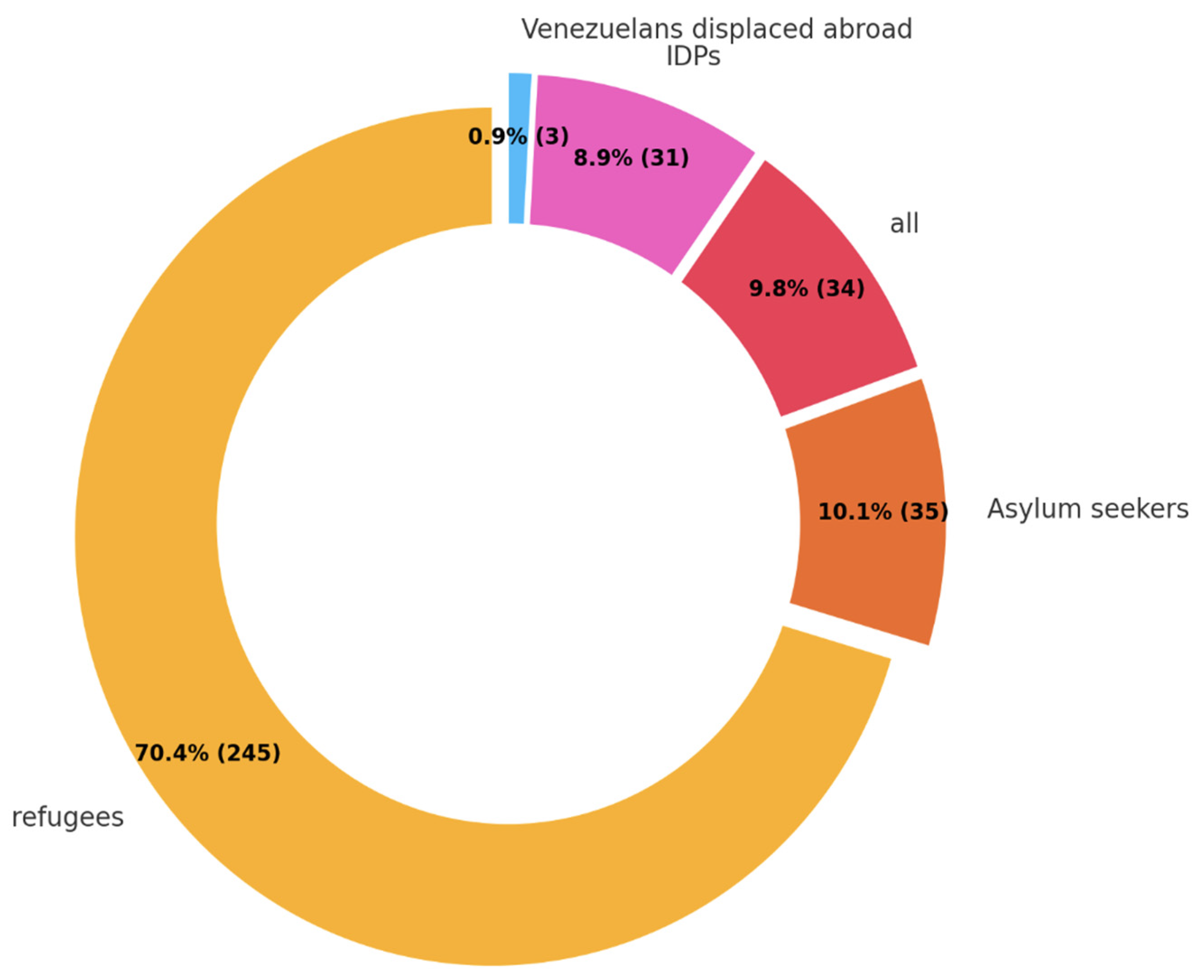

In the analysis of types of FDP, refugees were notably predominant, comprising 70.4% of the total (

Figure 9). Other categories- asylum seekers, Internally Displaced People (IDP), and Venezuelans displaced abroad- accounted for much smaller proportions at 10.1%, 8.9%, and 0.9%, respectively. No study was found for stateless people.

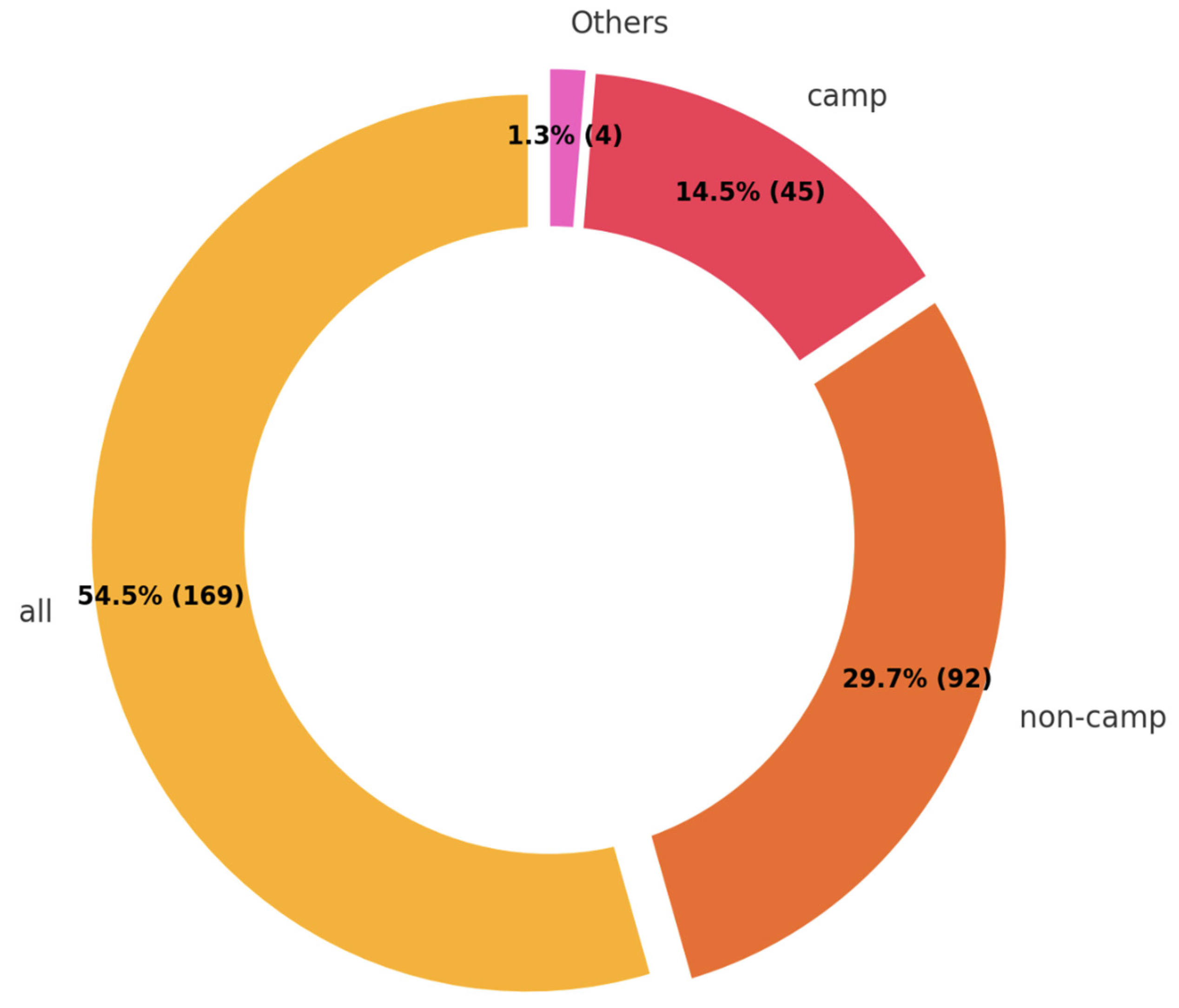

The findings of living environments show a diverse distribution (

Figure 10). The majority, comprising 54.5%, were categorized under “all”, indicating a general or unspecified living environment. This was followed by 29.7% residing in non-camp settings and 14.5% in camp-based environments.

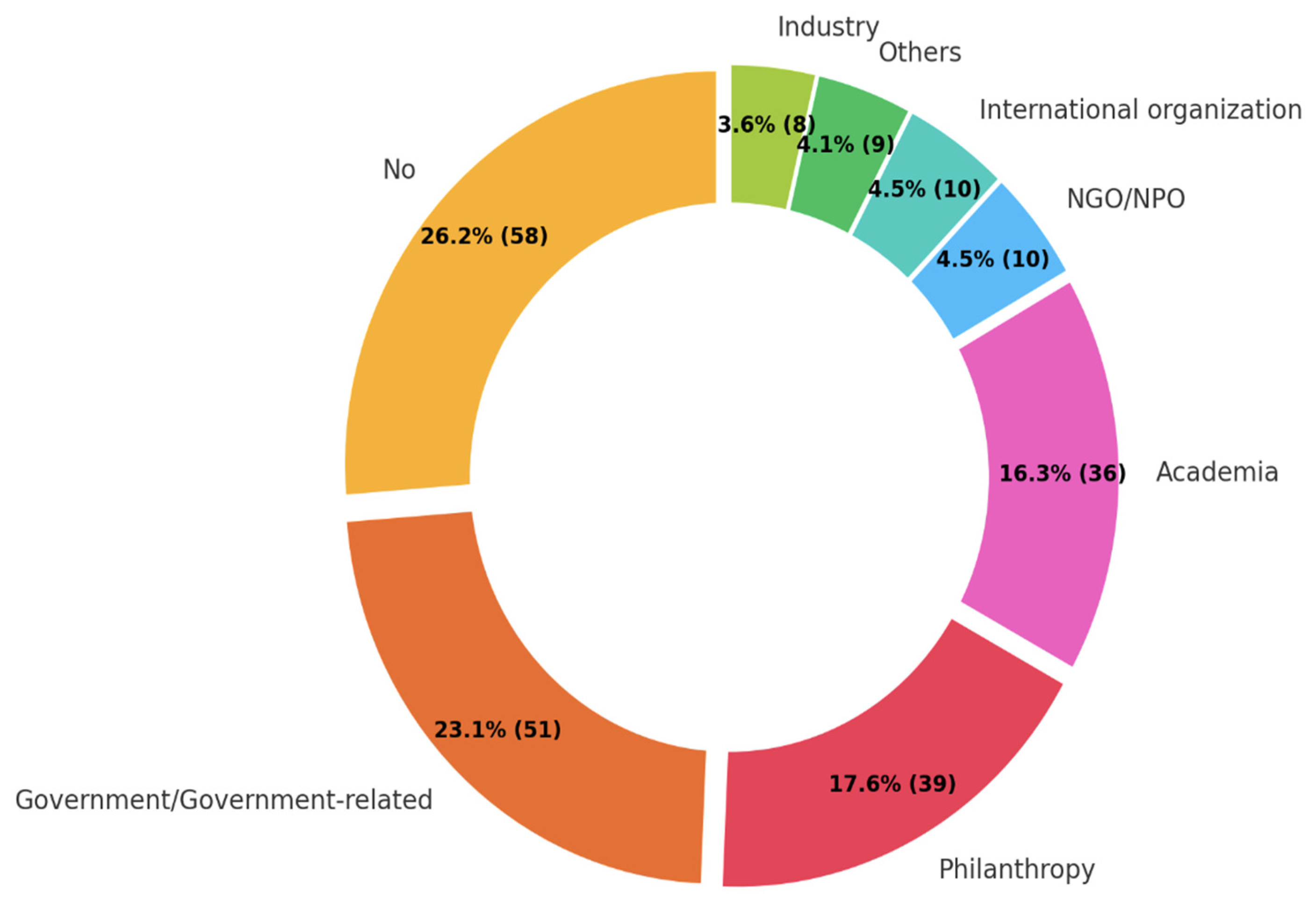

RQ6. Funding source: Which organizations financially supported the research on NCDs among FDP?

The most common funding source was the government or government-related funding agencies, contributing to 23.1% of the total (

Figure 11). This was closely followed by philanthropic foundations at 17.6% and academic institutions at 16.3%. International organizations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or non-profit organizations (NPOs), and industry and corporate research funding each constituted around 4% of the funding sources. Meanwhile, more than a quarter of the retrieved literature received no funding.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic mapping review about NCDs among FDP. The findings revealed both our current knowledge focuses and the gaps in the concerning issue. They enable us to expand and deepen our discussion, providing a clearer view of the current situation, exploring the reasons behind the identified barriers, and developing tailored strategies to move toward more effective NCDs control for their better health outcomes.

1.1. Research Focuses

The temporal trends in the publications showed a clear upward trend, especially in the last six years. This indicates the growing recognition of the importance of addressing NCDs in this vulnerable population.

Research questions from three to six have clarified the current research focuses within their respective topics. The predominant diseases studied are DM and hypertension, with research primarily concentrated on health status and health policy aspects. The main countries of origin for FDP studied are Syria and Palestine, whereas the host countries most frequently assessed are those under the UNRWA management, namely Lebanon, Jordan, Gaza, Syria, and the West Bank, alongside the USA and Turkey. The major type of FDP referred to in the retrieved studies is refugees. From these findings, it is evident that the most robust and detailed body of knowledge currently available pertains to DM and hypertension among refugees originated from Syria and Palestine, with a particular focus on their health status and health policy

1.1. Research Gaps

Three major research gaps were identified through this review: quality of research, geographical coverage, and type of FDP.

Gap 1. Quality of Research

The overall quality of retrieved studies revealed a low level of evidence in research on NCDs among FDP. The majority of publications falls within evidence levels V (21.3%), VI (21.9%), and VII (46.8%). Despite an increase in the quantity of research, the temporal trend indicates that the evidence level remains consistently low. Collectively, evidence level V, VI and VII has been accounted for approximately 90% of studies, with a quite limited number of primary research studies over time.

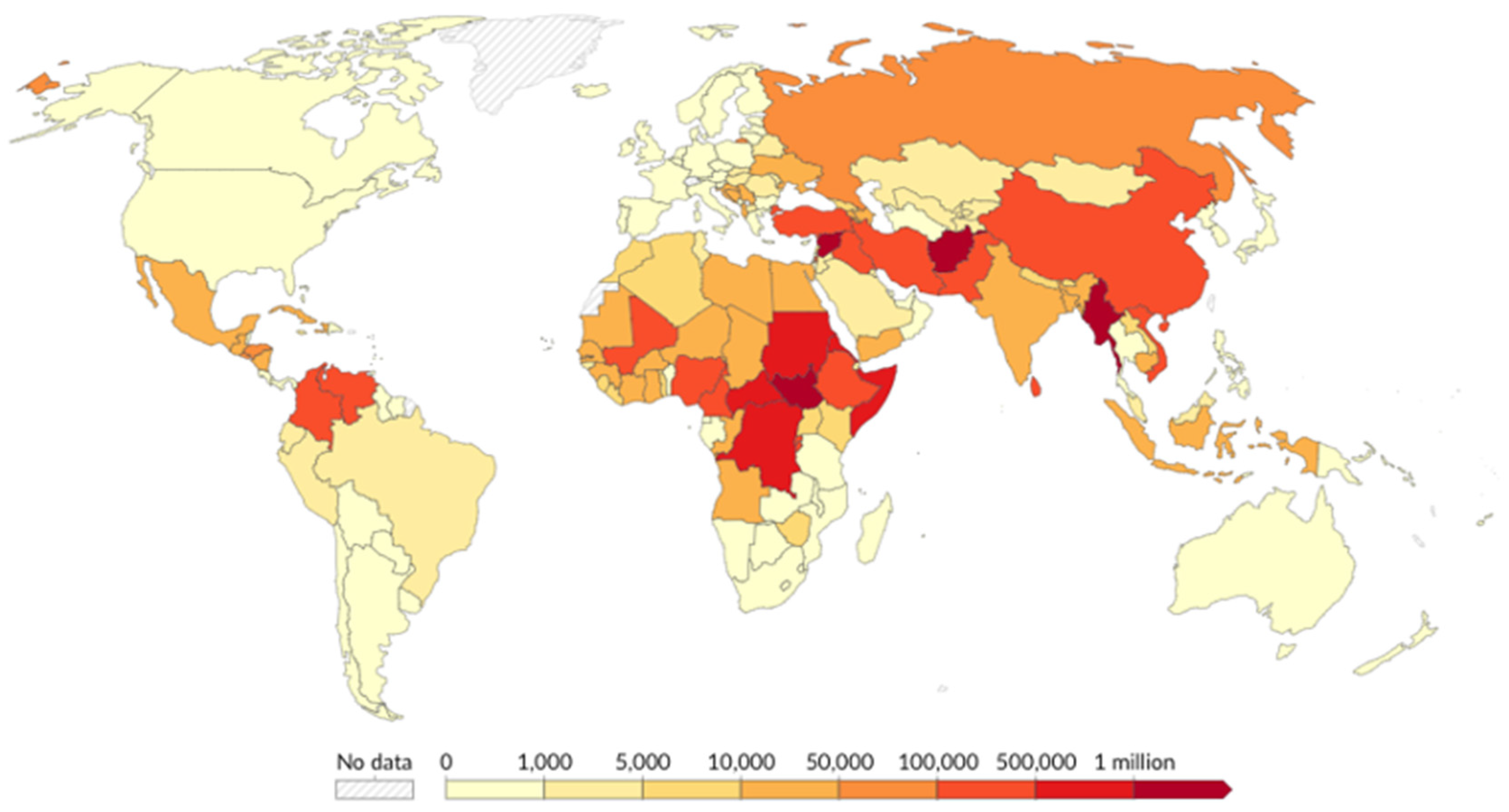

Gap 2. Geographical Coverage

Another concerning gap is the disproportionate emphasis on the countries of origin of FDP. While the majority of research focuses on Syria and Palestine, this overlooks the millions of FDP residing in other countries, notably LMICs, including Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and South America [

10] (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

The countries of the host were also significantly affected by the focus of research attention. As previously noted, five out of the seven frequently studied target countries were under the UNRWA management. Conversely, among the top ten host countries of people displaced across borders, excluding Turkey and under UNRWA management, namely Colombia, Uganda, Pakistan, Germany, Sudan, and Bangladesh, did not constitute the main focus of the retrieved studies [

11] (

Figure 14).

Gap 3. Type of FDP

The findings further highlighted a notable research gap concerning the types of FDP. Over 70% of studies focused on refugees, who constitute only a quarter of the total FDP (UNHCR, 2020). In contrast, IDP, who represent the predominant category of FDP, were the focus of less than 10% of the retrieved research (

Figure 15).

These identified research gaps, ranging from quality of research and countries of host and origin to types of FDP, underscore critical oversights in the academic literature and policy analysis on FDP. These gaps suggest that certain diseases affecting FDP, as well as particular subgroups defined by their country of origin and host, have been neglected. Moreover, the scarcity of research on IDP indicates a substantial deficiency in our understanding of the complex challenges these individuals face. The absence of comprehensive high quality research hampers the development of targeted interventions and policies, essentially rendering many FDP invisible within academic research and the broader international response to displacement issues. Consequently, their vulnerabilities continue unaddressed. Therefore, addressing these research gaps is imperative to foster a more inclusive and effective approach. Expanding the scope and depth of research to underrepresented diseases and populations will not only enhance the academic and policy framework but also improve the precision and impact of health interventions. Such efforts are essential to ensure that no groups remain marginalized in the global efforts to address displacement and its associated difficulties.

Limitations

This mapping review embodies several limitations that may impact the breadths and depth of the conclusions. Firstly, the exclusion of non-English articles represents a significant limitation. This language restriction can introduce a cultural and geographical bias, overlooking substantial research on NCDs among FDP conducted in non-English speaking countries Secondly, the omission of unpublished data can lead to an underrepresentation of available evidence. Unpublished studies, including national health data and conference papers, often contain relevant data that are not available in the retrieved publications. Excluding unpublished data could overlook a comprehensive view of current practices and challenges, particularly in capturing innovative strategies that are in the experimental phase of implementation. Thirdly, publication bias causes another concern. The bias can lead to an overestimation of the effectiveness of interventions and health status among FDP. It may also discourage the publication of studies that do not demonstrate efficacy, which is equally important for developing a full understanding of what does not work or what requires improvement. This skewed dissemination of information based on overly optimistic data can mislead our understanding of the situation. These limitations suggest that, while the mapping review provides valuable insights into the issue of NCD management among FDP, the results should be interpreted with caution, especially the generalizability and depth of findings.

Conclusion

This systematic mapping review synthesizes the current state of research on NCDs among FDP, revealing key insights into both the progress made and the gaps that remain. The growing academic interest in this issue, particularly since 2014, is encouraging, as it signals a recognition of the importance of addressing NCDs in vulnerable populations. However, significant gaps persist, both in the quality of the research and in the populations and diseases studied. DM and hypertension dominate the research landscape, with less attention paid to other major NCDs such as cancer and COPD. Geographically, the research is heavily concentrated on FDP from Syria and Palestine, with populations from Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America largely overlooked. Furthermore, the majority of studies focus on refugees, while IDP, who comprise the majority of FDP, are underrepresented in the literature.

Addressing these gaps is crucial for advancing the global response to NCDs among FDP. Future research should prioritize higher-quality studies, expand the geographical scope of research, and include a more diverse range of FDP populations. By doing so, policymakers and practitioners will be better equipped to develop evidence-based strategies that improve health outcomes for all FDP affected by NCDs. These efforts are vital to upholding the SDGs’ pledge of “no one left behind”, ensuring that FDP receive the necessary attention and care within humanitarian responses.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary S1: Study table. Summary description of retrieved 310 publications.

Author Contributions

KN collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. TG contributed to the screening and coding the process. MR conceived the study design and provided a critical review at each stage of the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We confirm that no specific funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Sachiko Ohde and Dr. Kazunari Ohnishi for their invaluable insights in expanding the analysis. We also deeply appreciate Ms. Akiko Sayama for her assistance in the comprehensive search for relevant literature.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

List of Abbreviations

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Diseases |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive |

| DM |

Diabetes Mellitus |

| FDP |

Forcibly Displaced People |

| HICs |

High-Income Countries |

| IDP |

Internally Displaced People |

| LMICs |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| NCDs |

Non-Communicable Diseases |

| NGOs |

Non-Governmental Organizations |

| NPOs |

Non-Profit Organizations |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| UHC |

Universal Health Coverage |

| UN |

United Nations |

| UNHCR |

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees |

| UNRWA |

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- The World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. Accessed November 7, 2023.

- The World Health Organization. Global action plan. For the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506236. Accessed May 10, 2022.

- The United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all ages [Internet]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/. Accessed May 10, 2022.

- Demaio A, Jamieson J, Horn R, De Courten, M, Tellier S. Non-communicable diseases in emergencies: A call to action. PLoS Curr. 2013; 5(Disasters): 0–8. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed SM, Hadi A, Razzaque A, Ashraf A, Juvekar S, Ng N, et al. Clustering of chronic non-communicable disease risk factors among selected Asian populations: Levels and determinants. Glob Health Action. 2009; 2(1), 68–75. [CrossRef]

- The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Refugee Data Finder [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/insights/explainers/100-million-forcibly-displaced.html. Accessed Nov 19, 2023,.

- The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global Report 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/flagship-reports/globalreport/. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- James KL, Randall NP, Haddaway NR. A methodology for systematic mapping in environmental sciences. Environmental Evidence. 2016; 5(1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. 5th ed . Wolters Kluwer; 2023.

- Our World in Data. Refugee population by country or territory of origin [Internet]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/refugee-population-by-country-or-territory-of-origin?time=2021. Accessed May 1, 2022.

- The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global Trend Forced Displacement in 2020 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/media/global-trends-forced-displacement-2020.Accessed May 14, 2022,.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).