Submitted:

23 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

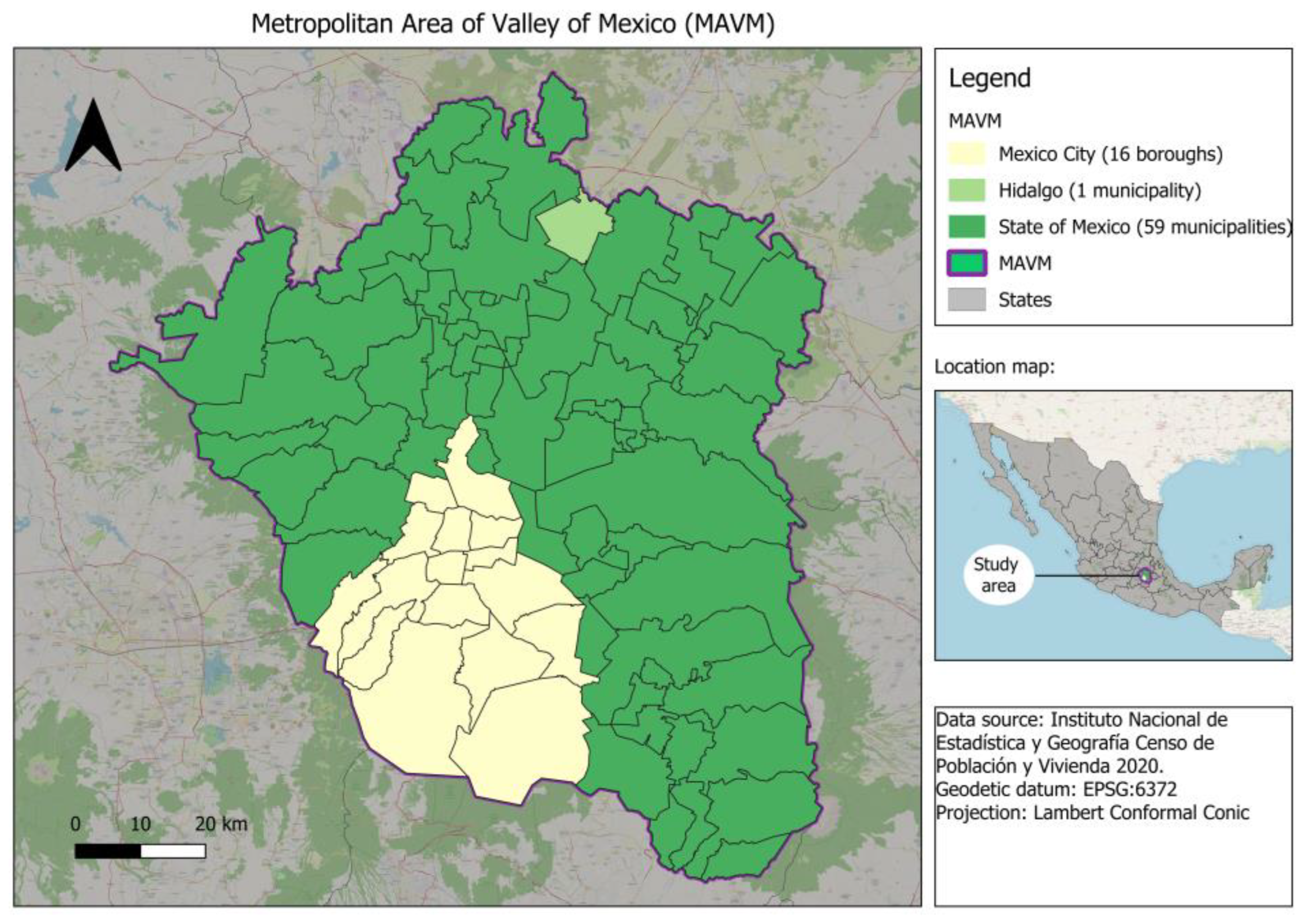

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Mortality Data

2.3. Population Data

2.4. Analisys Data

2.4.1. Temporal Trends

2.4.2. Relative Risk Estimation by Age and Sex Groups

2.4.3. Relative Risk Estimation by Municipalities

3. Results

3.1. Mortality by Non Comunicable Diseases at the Metropolitan Scale in the MAVM

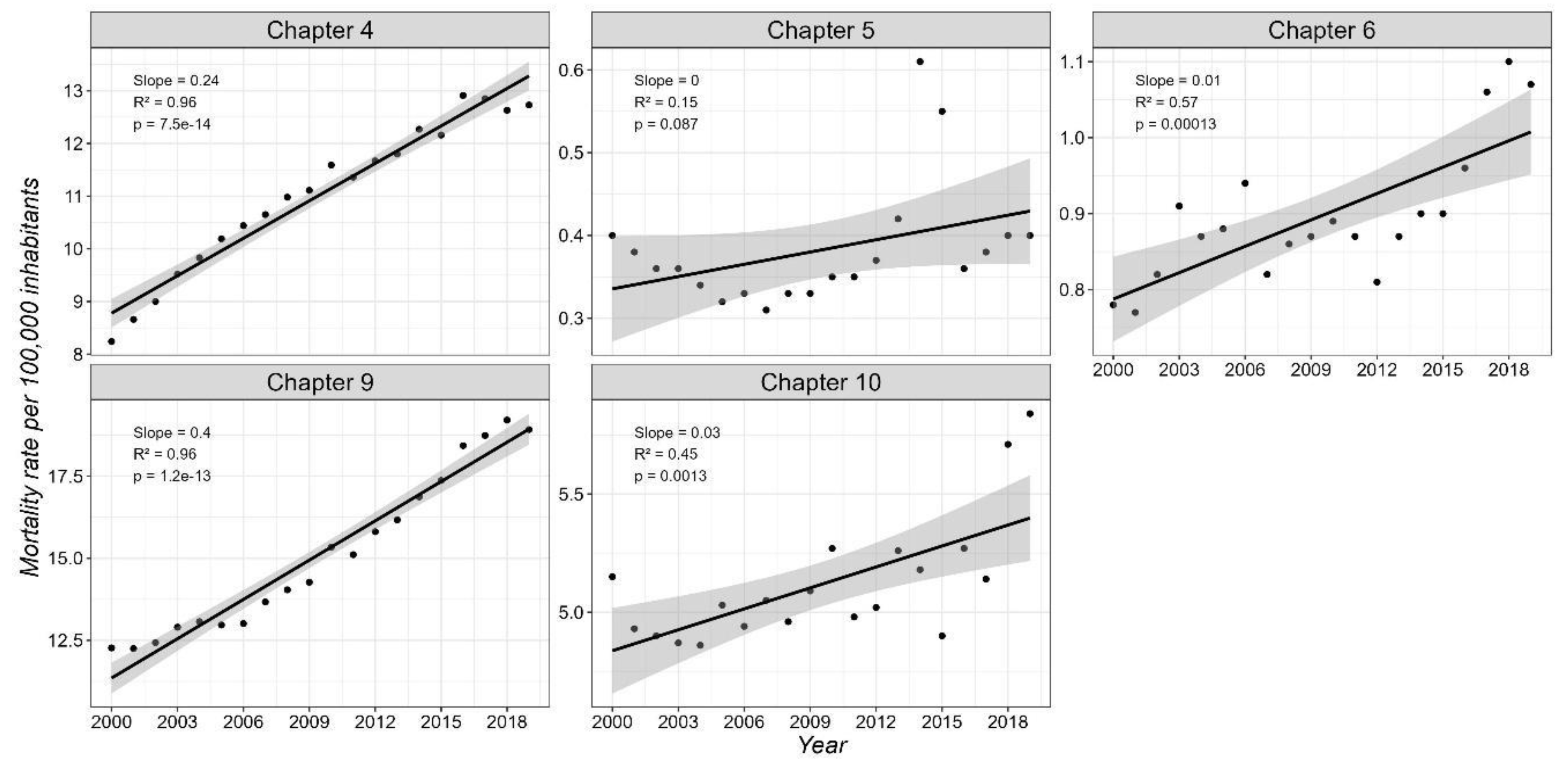

3.1.1. Mortality Trends for the Total Population

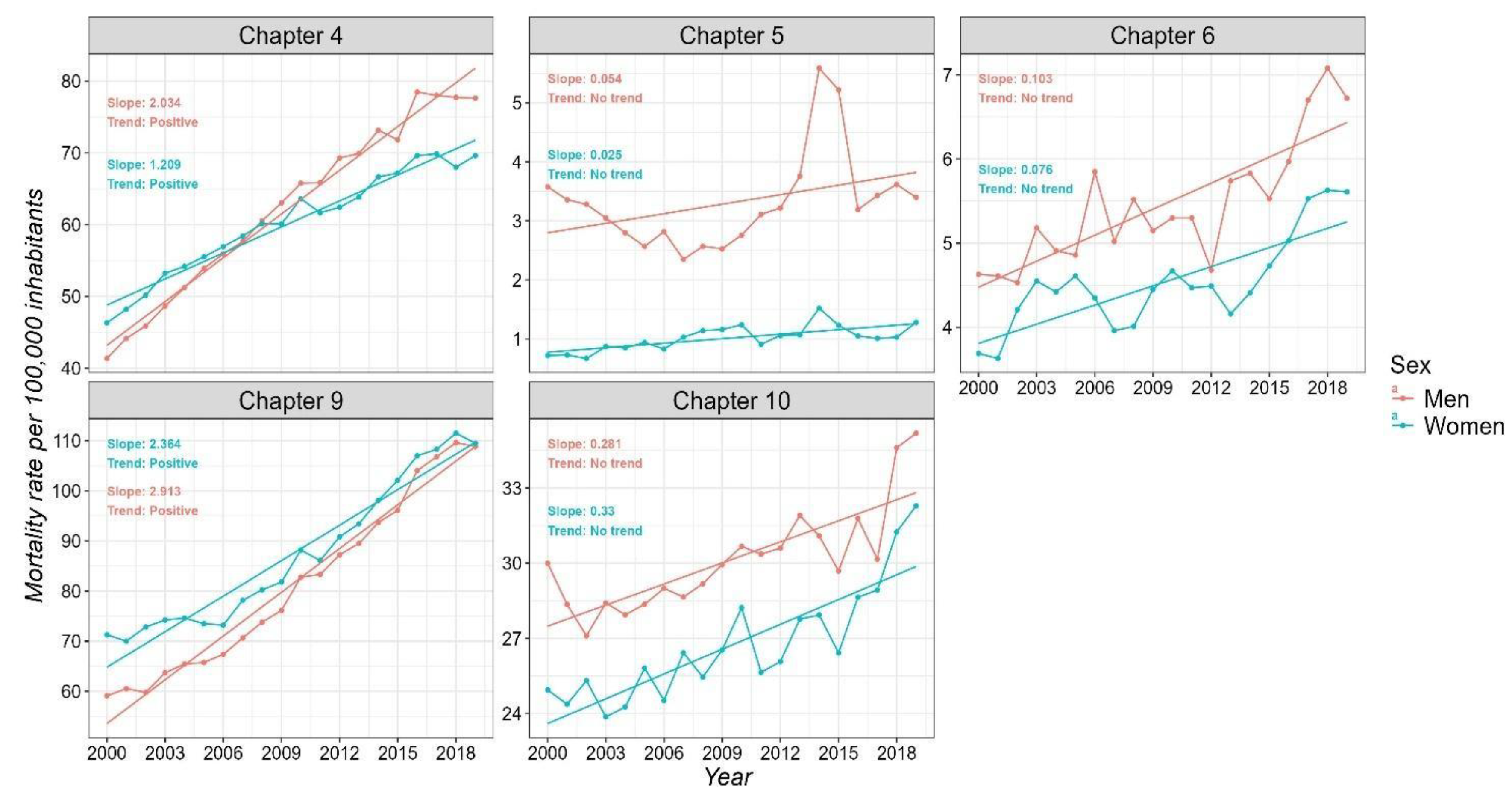

3.1.2. Sex-Specific Mortality Trends

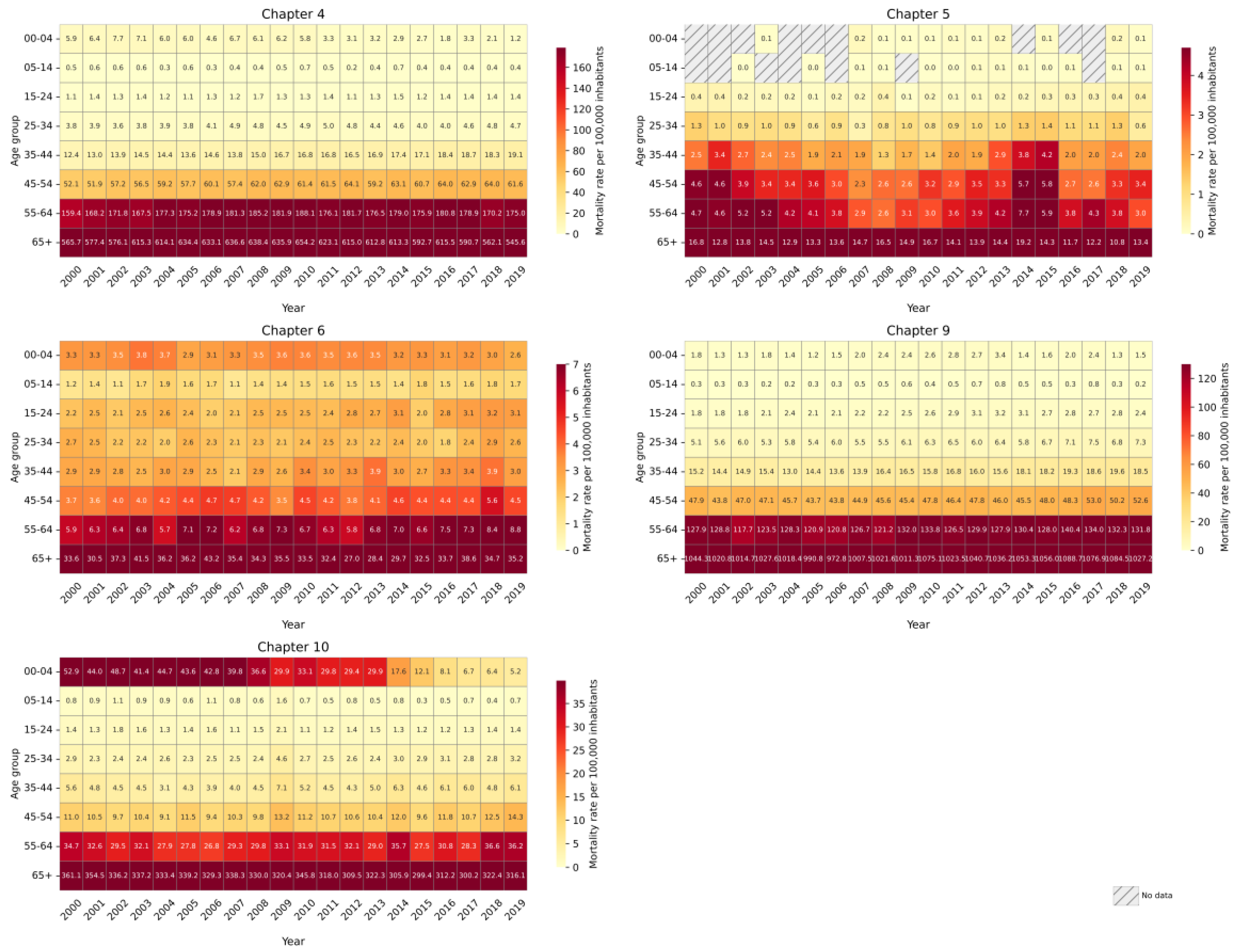

3.1.3. Age-Specific Mortality Trends

3.2. Municipal-Level Trends in Non-Communicable Disease Mortality in the MAVM

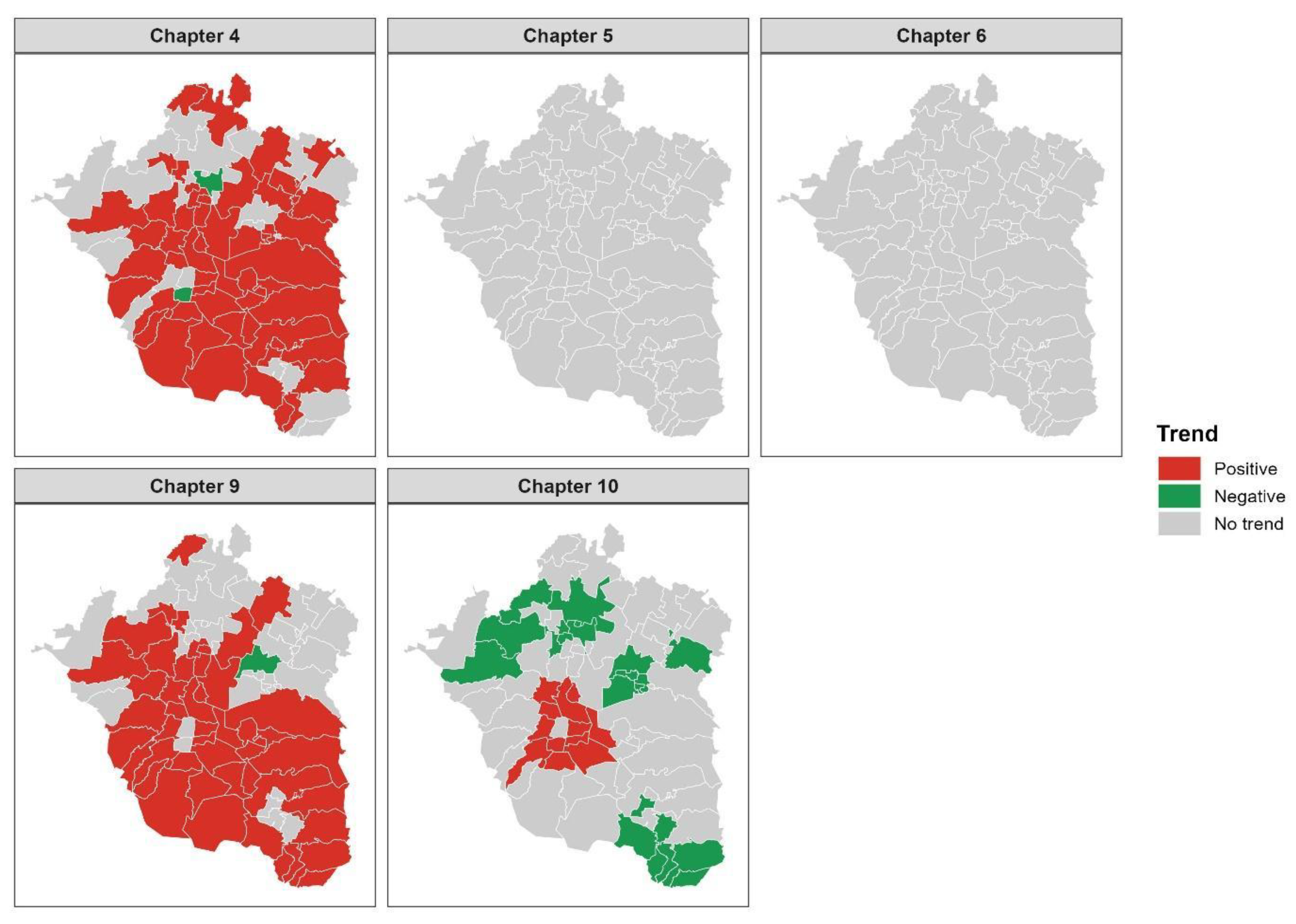

3.2.1. Mortality Trends for the Total Population

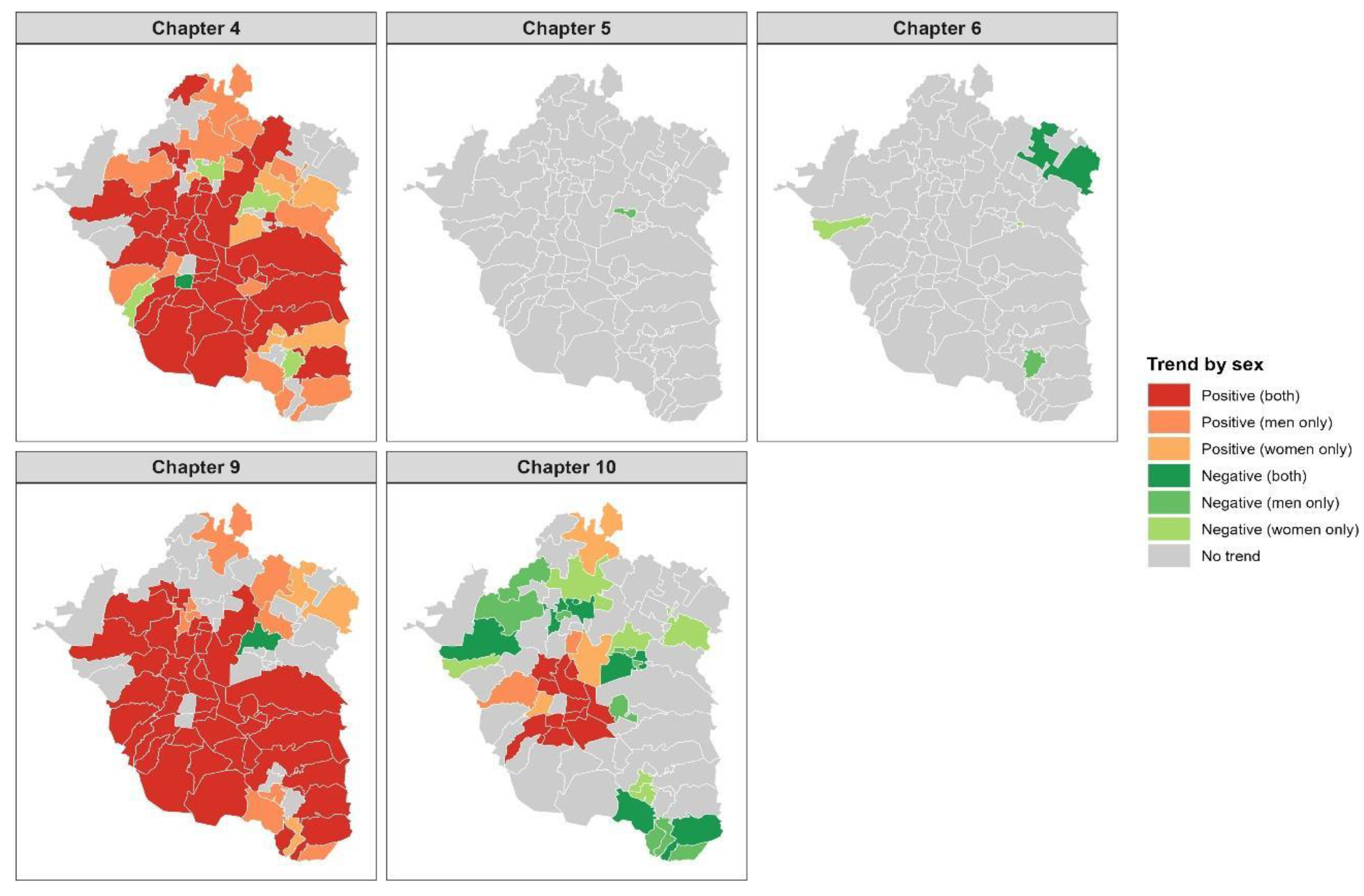

3.2.2. Sex-Specific Mortality Trends

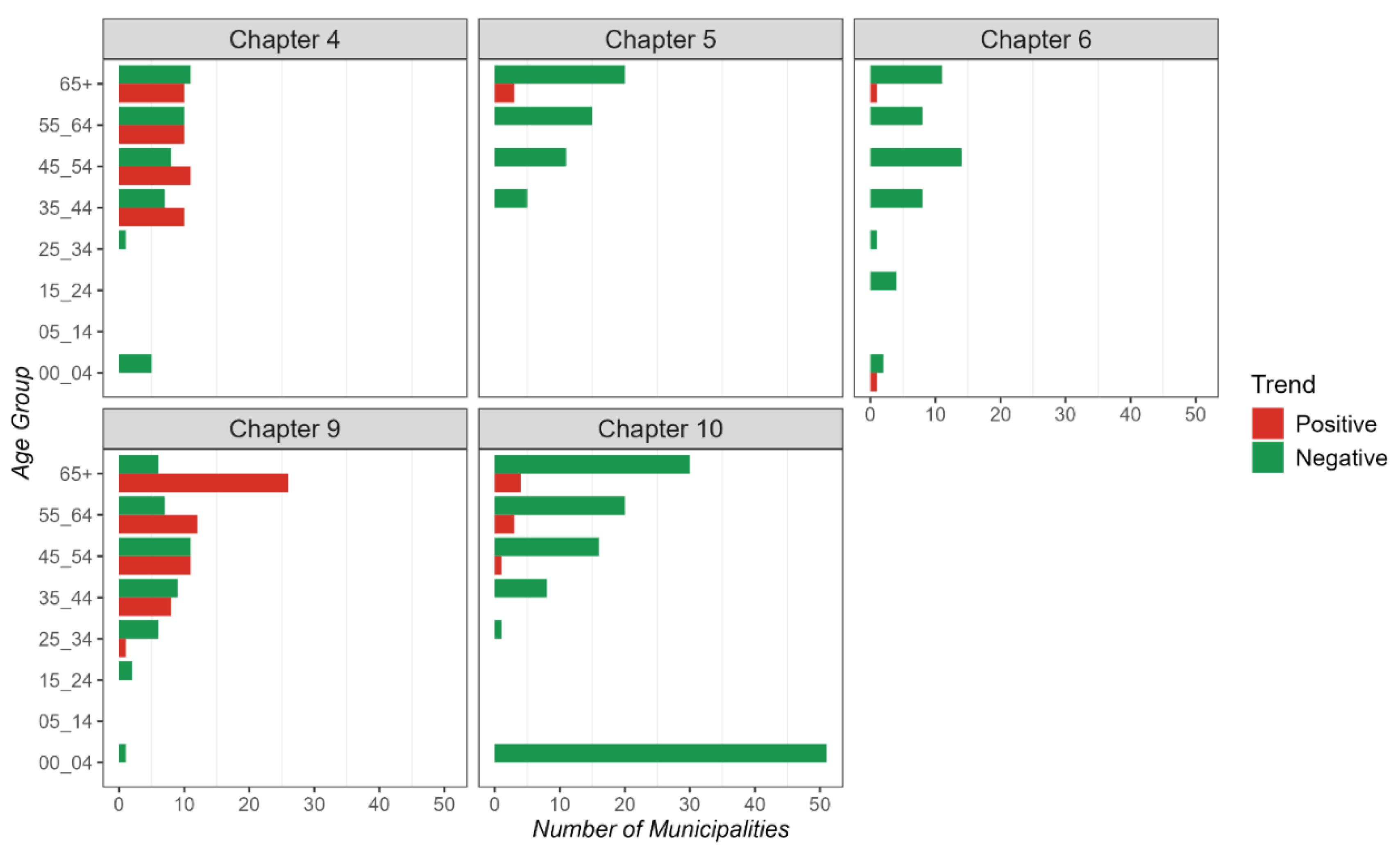

3.2.3. Age-Specific Mortality Trends

3.3. Relative Risk Trends in Non-Communicable Disease Mortality in the ZMVM

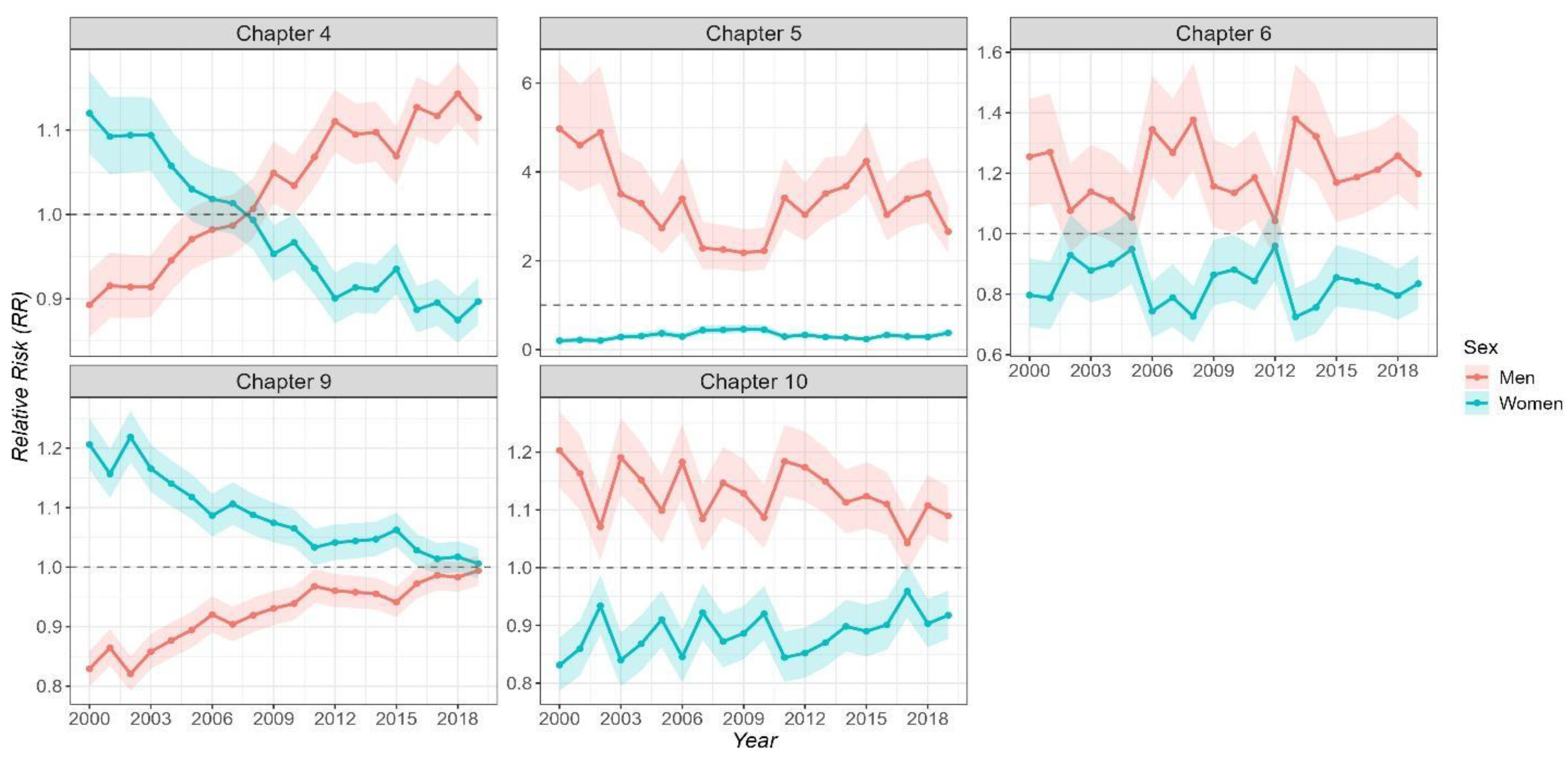

3.3.1. Sex-Specific Relative Risk of Mortality over Time

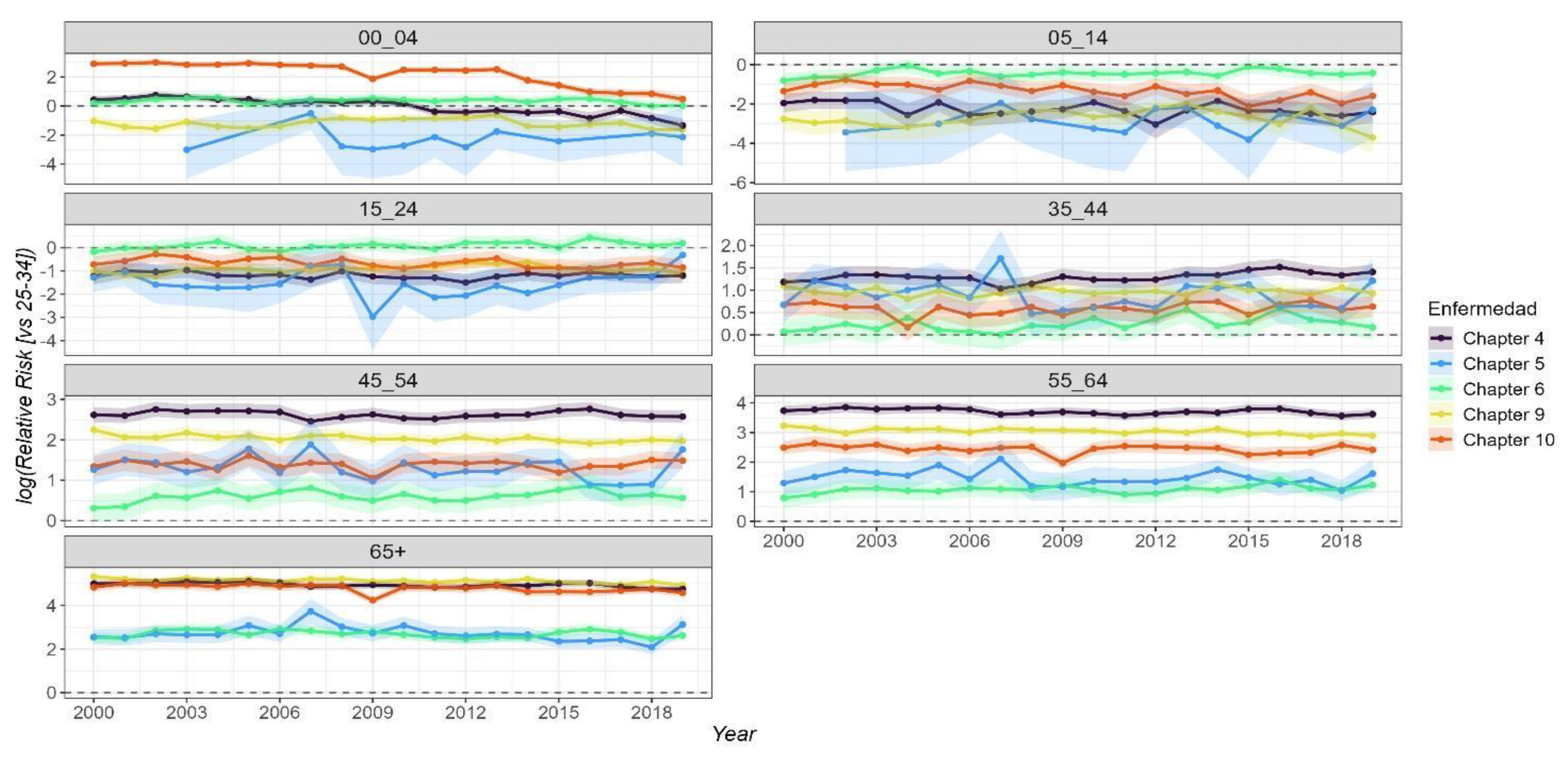

3.3.2. Age-Specific Relative Risk (RR) of Mortality over Time

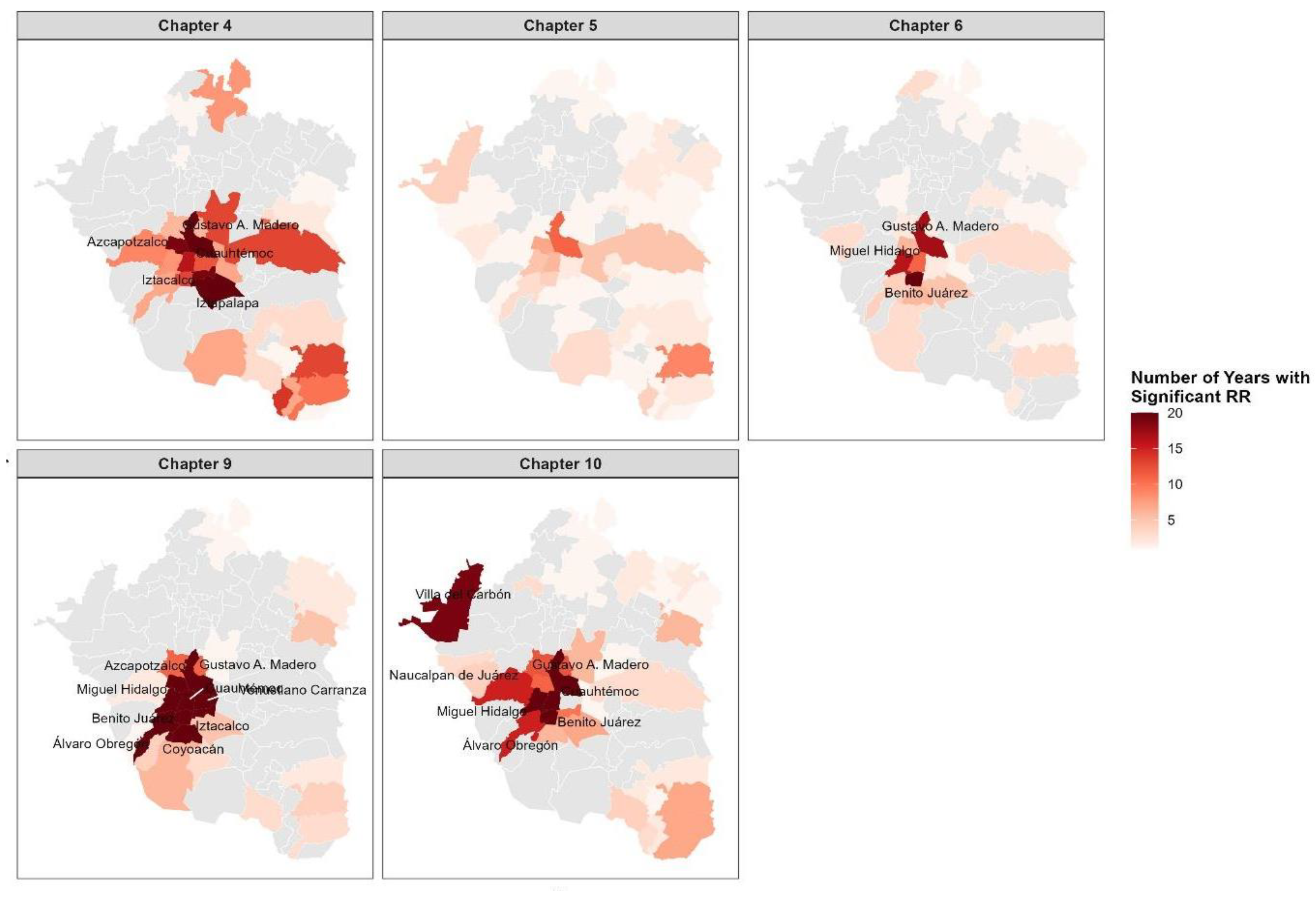

3.3.3. Municipality-Specific Relative Risk (RR) of Mortality over Time

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAVM | Metropolitan Area of Mexico Valley |

| NCD | Non-communicable diseases |

| MR | Mortality rate |

| Average of mortality rates | |

| CI | confidence interval |

| RR | relative risk |

Appendix A

| Average Mortality Rate (2000-2019) |

Slope | p-value | Trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter 4 (Endocrine, Nutritional and Metabolic Diseases) | ||||

| 00_04 | 4.6 | -0.300 | 0.0000 | No trend |

| 05_14 | 0.5 | -0.008 | 0.1310 | No trend |

| 15_24 | 1.3 | 0.006 | 0.3045 | No trend |

| 25_34 | 4.3 | 0.046 | 0.0060 | No trend |

| 35_44 | 15.9 | 0.330 | 0.0000 | No trend |

| 45_54 | 60.0 | 0.495 | 0.0000 | No trend |

| 55_64 | 176.4 | 0.444 | 0.0834 | No trend |

| 65+ | 607.6 | -0.844 | 0.4783 | No trend |

| Chapter 5 (Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental disorders) | ||||

| 00_04 | 0.1 | 0.004 | 0.3106 | No trend |

| 05_14 | 0.1 | 0.008 | 0.4461 | No trend |

| 15_24 | 0.2 | 0.002 | 0.9606 | No trend |

| 25_34 | 1.0 | -0.015 | 0.7101 | No trend |

| 35_44 | 2.4 | -0.013 | 0.7904 | No trend |

| 45_54 | 3.5 | -0.070 | 0.3693 | No trend |

| 55_64 | 4.2 | 0.002 | 0.1542 | No trend |

| 65+ | 14.2 | 0.004 | 0.3790 | No trend |

| Chapter 6 (Disease of the Nervous System) | ||||

| 00_04 | 3.3 | -0.022 | 0.0598 | No trend |

| 05_14 | 1.5 | 0.013 | 0.1052 | No trend |

| 15_24 | 2.6 | 0.041 | 0.0013 | No trend |

| 25_34 | 2.3 | 0.002 | 0.8179 | No trend |

| 35_44 | 3.0 | 0.041 | 0.0131 | No trend |

| 45_54 | 4.3 | 0.042 | 0.0187 | No trend |

| 55_64 | 6.8 | 0.088 | 0.0018 | No trend |

| 65+ | 34.5 | -0.174 | 0.2724 | No trend |

| Chapter 9 (Disease of the Circulatory System) | ||||

| 00_04 | 1.9 | 0.027 | 0.2819 | No trend |

| 05_14 | 0.4 | 0.012 | 0.1136 | No trend |

| 15_24 | 2.5 | 0.060 | 0.0001 | No trend |

| 25_34 | 6.1 | 0.099 | 0.0000 | No trend |

| 35_44 | 16.2 | 0.279 | 0.0000 | No trend |

| 45_54 | 47.0 | 0.287 | 0.0019 | No trend |

| 55_64 | 128.1 | 0.573 | 0.0032 | Positive |

| 65+ | 1034.6 | 3.114 | 0.0054 | Positive |

| Chapter 10 (Disease of Respiratory System) | ||||

| 00_04 | 30.1 | -2.526 | 0.0000 | Negative |

| 05_14 | 0.8 | -0.024 | 0.0317 | No trend |

| 15_24 | 1.4 | -0.010 | 0.2832 | No trend |

| 25_34 | 2.7 | 0.027 | 0.1787 | No trend |

| 35_44 | 5.0 | 0.071 | 0.0616 | No trend |

| 45_54 | 10.9 | 0.111 | 0.0259 | No trend |

| 55_64 | 31.2 | 0.119 | 0.3199 | No trend |

| 65+ | 326.6 | -2.364 | 0.0000 | Negative |

References

- World Health Organization Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2018; Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018.

- Bennett, J.E.; Stevens, G.A.; Mathers, C.D.; Bonita, R.; Rehm, J.; Kruk, M.E.; Riley, L.M.; Dain, K.; Kengne, A.P.; Chalkidou, K.; et al. NCD Countdown 2030: Worldwide Trends in Non-Communicable Disease Mortality and Progress towards Sustainable Development Goal Target 3.4. The Lancet 2018, 392, 1072–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girum, T.; Mesfin, D.; Bedewi, J.; Shewangizaw, M. The Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in Ethiopia, 2000–2016: Analysis of Evidence from Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 and Global Health Estimates 2016. Int J Chronic Dis 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuoane-Nkhasi, M.; van Eeden, A. Spatial Patterns and Correlates of Mortality Due to Selected Non-Communicable Diseases among Adults in South Africa, 2011. GeoJournal 2017, 82, 1005–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, D.E.; Cafiero, E.T.; Jané-Llopis, E.; Abrahams-Gessel, S.; Bloom, L.R.; Fathima, S.; Feigl, A.B.; Gaziano, T.; Mowafi, M.; Pandya, A.; et al. The Global Economic Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases. 2011.

- Capizzi, S.; De Waure, C.; Boccia, S. Global Burden and Health Trends of Non-Communicable Diseases. In A Systematic Review of Key Issues in Public Health; Springer International Publishing, 2015; pp. 19–32 ISBN 9783319136202.

- Roth, G.A.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Age-Sex-Specific Mortality for 282 Causes of Death in 195 Countries and Territories, 1980–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzati, M.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Bennett, J.E.; Mathers, C.D. Acting on Non-Communicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Tropical Countries. Nature 2018, 559, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, L.W.; Mohan, D.; Akuoku, J.K.; Mirelman, A.J.; Ahmed, S.; Koehlmoos, T.P.; Trujillo, A.; Khan, J.; Peters, D.H. Tackling Socioeconomic Inequalities and Non-Communicable Diseases in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries under the Sustainable Development Agenda. The Lancet 2018, 391, 2036–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, I.; Griebler, U.; Mahlknecht, P.; Thaler, K.; Bouskill, K.; Gartlehner, G.; Mendis, S. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Non-Communicable Diseases and Their Risk Factors: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. BMC Public Health 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.H.; Brath, H. A Global View on the Development of Non Communicable Diseases. Prev Med (Baltim) 2012, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girum, T.; Mesfin, D.; Bedewi, J.; Shewangizaw, M. The Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases in Ethiopia, 2000–2016: Analysis of Evidence from Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 and Global Health Estimates 2016. Int J Chronic Dis 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadmani, F.K.; Farzadfar, F.; Larijani, B.; Mirzaei, M.; Haghdoost, A.A. Trend and Projection of Mortality Rate Due to Non-Communicable Diseases in Iran: A Modeling Study. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves, B.; Ingram, M.; Nieto, C.; de Zapien, J.G.; Rosales, C. Non-Communicable Disease Prevention in Mexico: Policies, Programs and Regulations. Health Promot Int 2021, 35, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquera, S.; Campos-Nonato, I.; Hernández-Barrera, L. Prevalencia de Obesidad En Adultos Mexicanos, ENSANUT 2012. Salud Publica Mex 2013, 55, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rtveladze, K.; Marsh, T.; Barquera, S.; Sanchez Romero, L.M. aria; Levy, D.; Melendez, G.; Webber, L.; Kilpi, F.; McPherson, K.; Brown, M. Obesity Prevalence in Mexico: Impact on Health and Economic Burden. Public Health Nutr 2014, 17, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario Territorial y Urbano Sistema Urbano Nacional 2018; Mexico, 2018;

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020; Mexico, 2020;

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services & National Center for Health Statistics ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting FY 2024 (Updated April 1, 2024); U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2024;

- Consejo Nacional de Población Población de Los Municipios 1990-2040 (Bases de Datos); CONAPO. México, 2024;

- Lemaitre, M.; Carrat, F. Comparative Age Distribution of Influenza Morbidity and Mortality during Seasonal Influenza Epidemics and the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic. BMC Infect Dis 2010, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, S.B. Gender Disparities in Injury Mortality: Consistent, Persistent, and Larger than You’d Think. Am J Public Health 2011, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.A.; Gardner, M.J. Calculating Confidence Intervals for Relative Risks (Odds Ratios) and Standardised Ratios and Rates. Br Med J 1988, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Nichols, E.; Alam, T.; Bannick, M.S.; Beghi, E.; Blake, N.; Culpepper, W.J.; Dorsey, E.R.; Elbaz, A.; Ellenbogen, R.G.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Neurological Disorders, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri Soodejani, M. Non-Communicable Diseases in the World over the Past Century: A Secondary Data Analysis. Front Public Health 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.S.S.; Bilal, U.; Andrade, R.F.S.; Neto, C.C.C.; de Sousa Filho, J.F.; Santos, G.F.; Barreto, M.L.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Mullachery, P.; Sanchez, B.; et al. Scaling of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in 230 Latin American Cities. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, U.; de Castro, C.P.; Alfaro, T.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T.; Barreto, M.L.; Leveau, C.M.; Martinez-Folgar, K.; Miranda, J.J.; Montes, F.; Mullachery, P.; et al. Scaling of Mortality in 742 Metropolitan Areas of the Americas. Sci Adv 2021, 7, 6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, M.; Balmes, J.R. Outdoor Air Pollution and Asthma. The Lancet 2014, 383, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raga, G.B.; Baumgardner, D.; Castro, T.; Martínez-Arroyo, A.; Navarro-González, R. Mexico City Air Quality: A Qualitative Review of Gas and Aerosol Measurements (1960–2000). Atmos Environ 2001, 35, 4041–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Chisholm, D.; Parikh, R.; Charlson, F.J.; Degenhardt, L.; Dua, T.; Ferrari, A.J.; Hyman, S.; Laxminarayan, R.; Levin, C.; et al. Addressing the Burden of Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders: Key Messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition. The Lancet 2016, 387, 1672–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahomed, F. Addressing the Problem of Severe Underinvestment in Mental Health and Well-Being from a Human Rights Perspective. Health Hum Rights 2020, 22, 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bots, S.H.; Peters, S.A.E.; Woodward, M.; Sanne, D.; Peters, A.E. Sex Differences in Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke Mortality: A Global Assessment of the Effect of Ageing between 1980 and 2010. BMJ Glob Health 2017, 2, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkola, T.S.; Gissler, M.; Merikukka, M.; Tuomikoski, P.; Ylikorkala, O. Sex Differences in Age-Related Cardiovascular Mortality. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pandian, V.; Davidson, P.M.; Song, Y.; Chen, N.; Fong, D.Y.T. Burden and Attributable Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases and Subtypes in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. International Journal of Surgery 2025, 111, 2385–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.; Abajobir, A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abera, S.F.; Abyu, G.; Ahmed, M.; Aksut, B.; Alam, T.; Alam, K.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017, 70, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaway, J.D.; Afshin, A.; Gakidou, E.; Lim, S.S.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Comparative Risk Assessment of 84 Behavioural, Environmental and Occupational, and Metabolic Risks or Clusters of Risks for 195 Countries and Territories, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2018, 392, 1923–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Landrigan, P.J. Neurobehavioural Effects of Developmental Toxicity. Lancet Neurol 2014, 13, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.; Landrigan, P.J.; Balakrishnan, K.; Bathan, G.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Brauer, M.; Caravanos, J.; Chiles, T.; Cohen, A.; Corra, L.; et al. Pollution and Health: A Progress Update. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e535–e547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Song, H.; Cheng, Y.; Yao, X.; Li, Y. The Mortality Burden of Nervous System Diseases Attributed to Ambient Temperature: A Multi-City Study in China. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.Y.; Ng, C.F.S.; Kim, Y.; Htay, Z.W.; Cao, A.Q.; Pan, R.; Hashizume, M. Ambient Temperature and Nervous System Diseases-Related Mortality in Japan from 2010 to 2019: A Time-Stratified Case-Crossover Analysis. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 867, 161464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, B.; Acevedo, M.; Appelman, Y.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Chieffo, A.; Figtree, G.A.; Guerrero, M.; Kunadian, V.; Lam, C.S.P.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; et al. The Lancet Women and Cardiovascular Disease Commission: Reducing the Global Burden by 2030. The Lancet 2021, 397, 2385–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A. V. Conceptual Approaches to the Study of Health Disparities. In Proceedings of the Annual Review of Public Health; April 21 2012; Vol. 33; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Argumedo, G.; Cruz-Casarrubias, C.A.; Bonvecchio-Arenas, A.; Jáuregui, A.; Saavedra-Romero, A.; Martínez-Montañez, O.G.; Meléndez-Irigoyen, M.T.; Karam-Araujo, R.; Uribe-Carvajal, R.; Olvera, A.; et al. Towards the Design of Healthy Living, a New Curriculum for Basic Education in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2023, 65, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud Programa Sectorial Derivado Del Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2019-2024. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2020.

- Cacciatore, S.; Mao, S.; Nuñez, M.V.; Massaro, C.; Spadafora, L.; Bernardi, M.; Perone, F.; Sabouret, P.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Banach, M.; et al. Urban Health Inequities and Healthy Longevity: Traditional and Emerging Risk Factors across the Cities and Policy Implications. Aging Clin Exp Res 2025, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Curtis, S.; Diez-Roux, A. V.; Macintyre, S. Understanding and Representing “place” in Health Research: A Relational Approach. Soc Sci Med 2007, 65, 1825–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cumulative deaths from 2000 to 2019 | |||||||

| Sex | Age group | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 9 | Chapter 10 | Total |

| Men | 00-04 | 937 | 12 | 675 | 376 | 6365 | 8365 |

| 05-14 | 177 | 16 | 624 | 171 | 301 | 1289 | |

| 15-24 | 519 | 135 | 1285 | 1185 | 638 | 3762 | |

| 25-34 | 1916 | 618 | 972 | 2923 | 1344 | 7773 | |

| 35-44 | 6114 | 1313 | 1054 | 6547 | 1908 | 16936 | |

| 45-54 | 16500 | 1457 | 1060 | 13618 | 2926 | 35561 | |

| 55-64 | 28239 | 1079 | 1130 | 22913 | 5222 | 58583 | |

| 65+ | 70865 | 1977 | 4099 | 115163 | 41363 | 233467 | |

| Women | 00-04 | 743 | 8 | 507 | 309 | 4709 | 6276 |

| 05-14 | 160 | 10 | 465 | 143 | 254 | 1032 | |

| 15-24 | 457 | 35 | 601 | 643 | 407 | 2143 | |

| 25-34 | 1093 | 54 | 645 | 1341 | 560 | 3693 | |

| 35-44 | 3325 | 72 | 712 | 3058 | 1026 | 8193 | |

| 45-54 | 10580 | 114 | 869 | 7561 | 2013 | 21137 | |

| 55-64 | 23120 | 134 | 891 | 14509 | 3879 | 42533 | |

| 65+ | 88320 | 1733 | 4906 | 157741 | 43688 | 296388 | |

| TOTAL | 253065 | 8767 | 20495 | 348201 | 116603 | 747131 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).