Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Instruments, Datasets, and Methodologies

3. Characteristics of the Lamezia Terme WMO/GAW Observation Site

4. Results

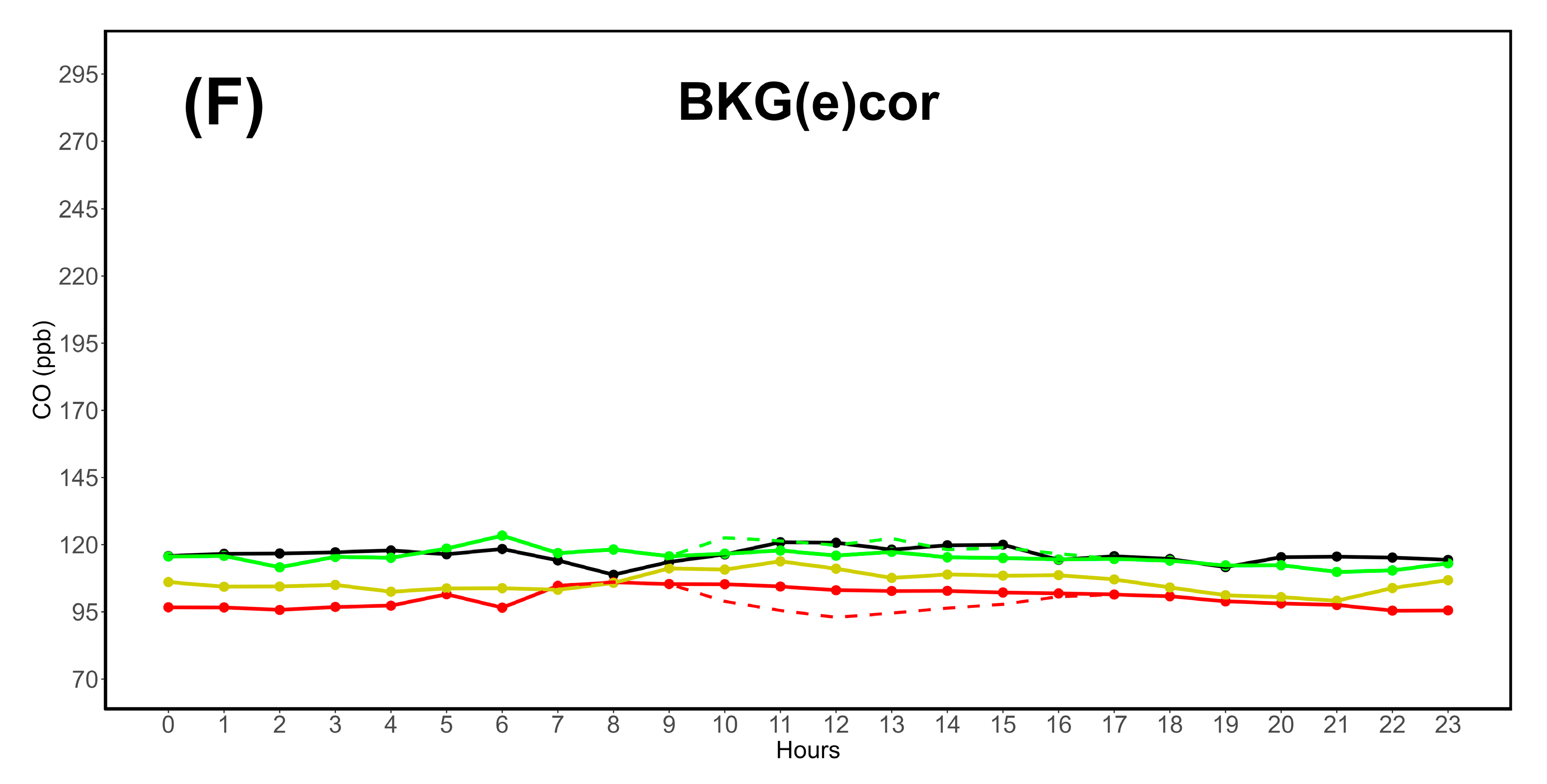

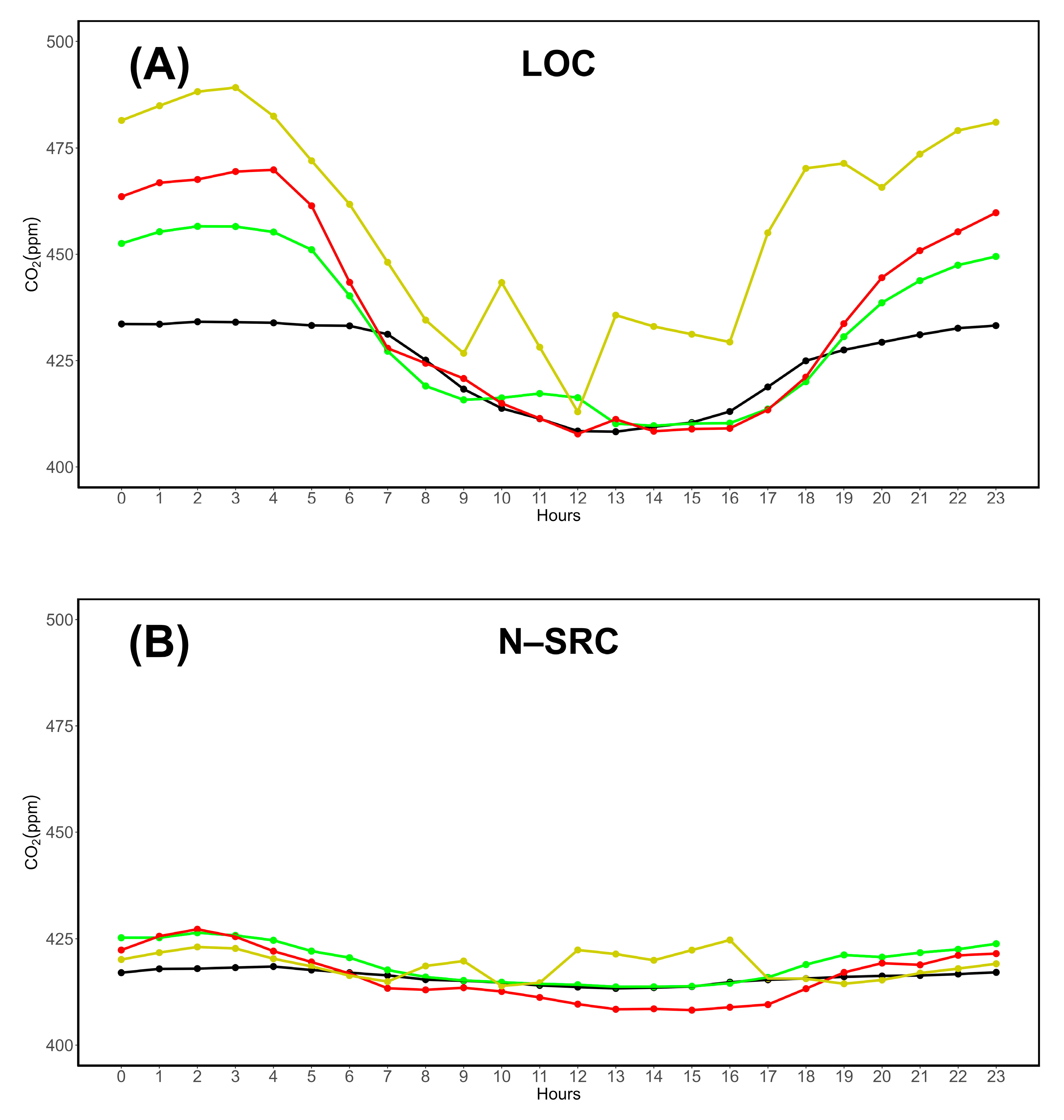

4.1. CO, CO2, and CH4 Concentration Variability by Category

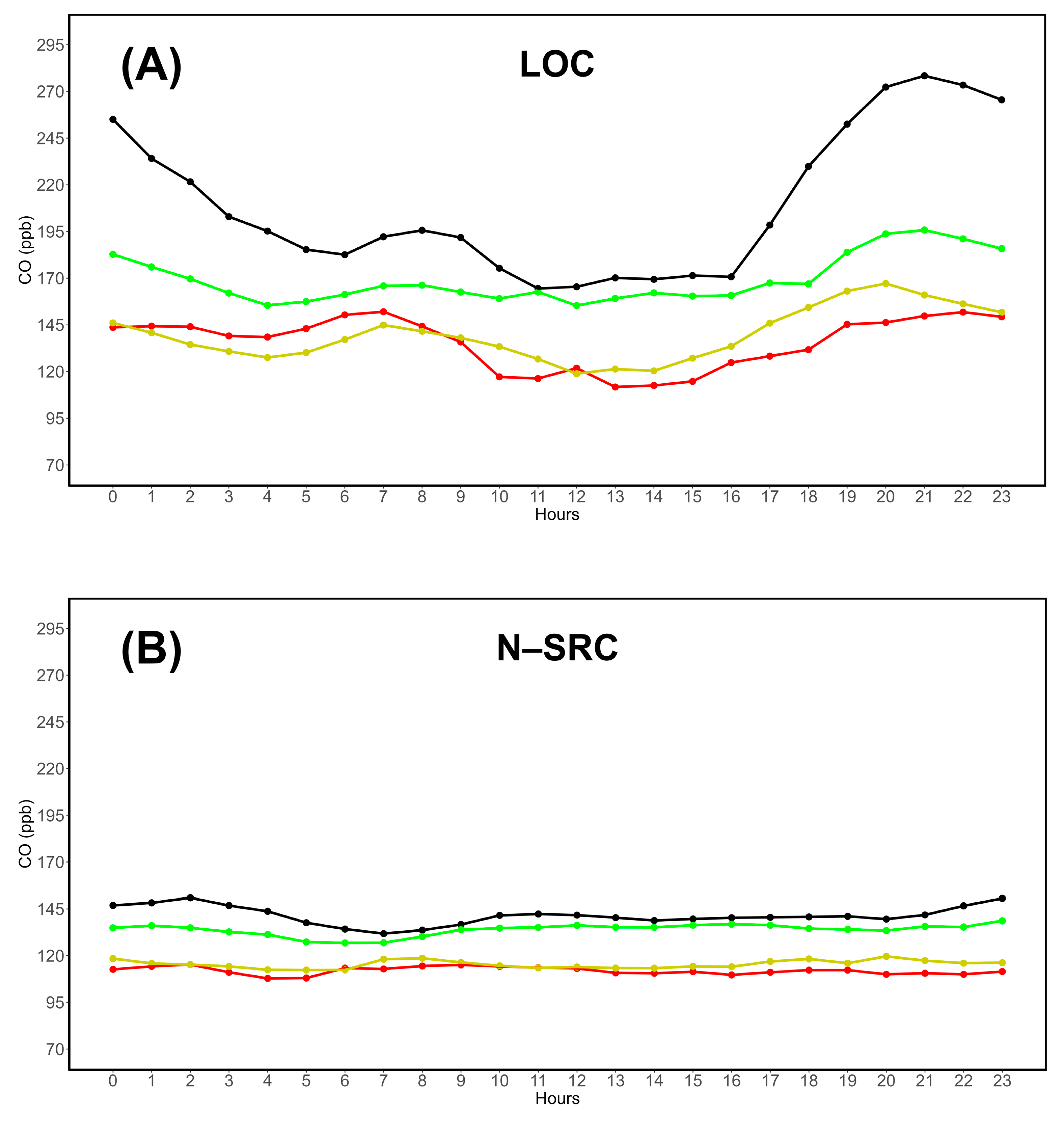

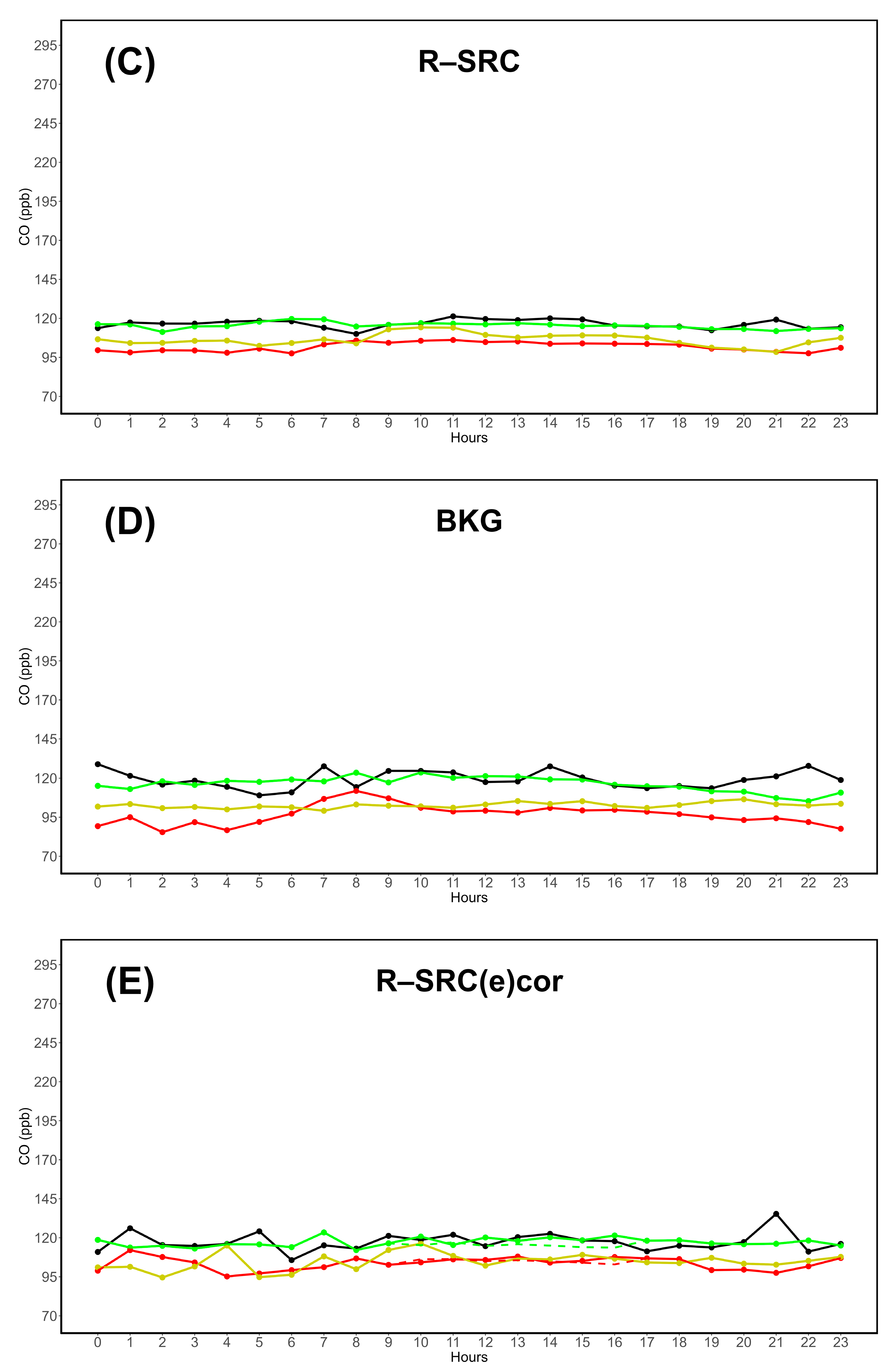

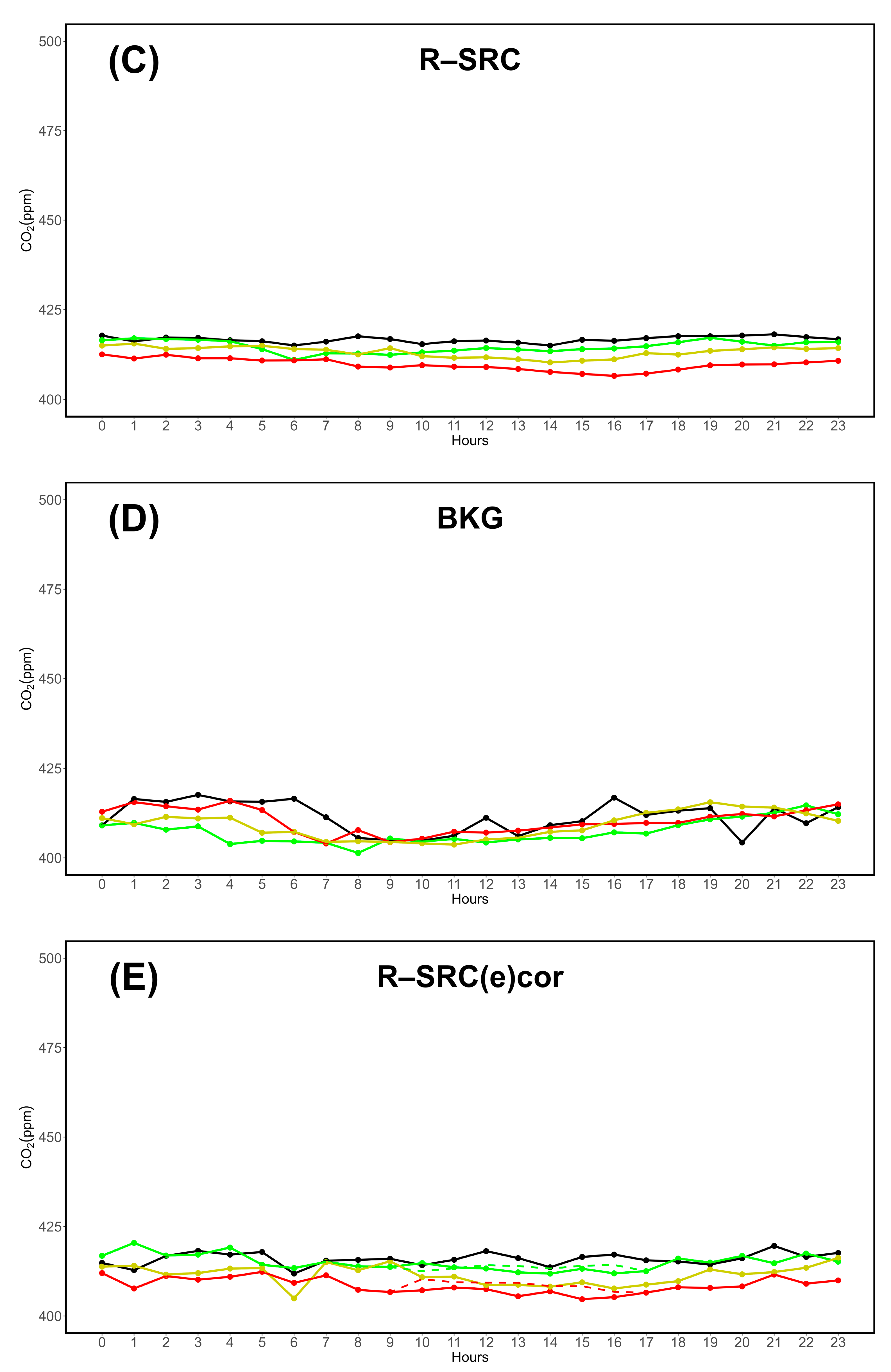

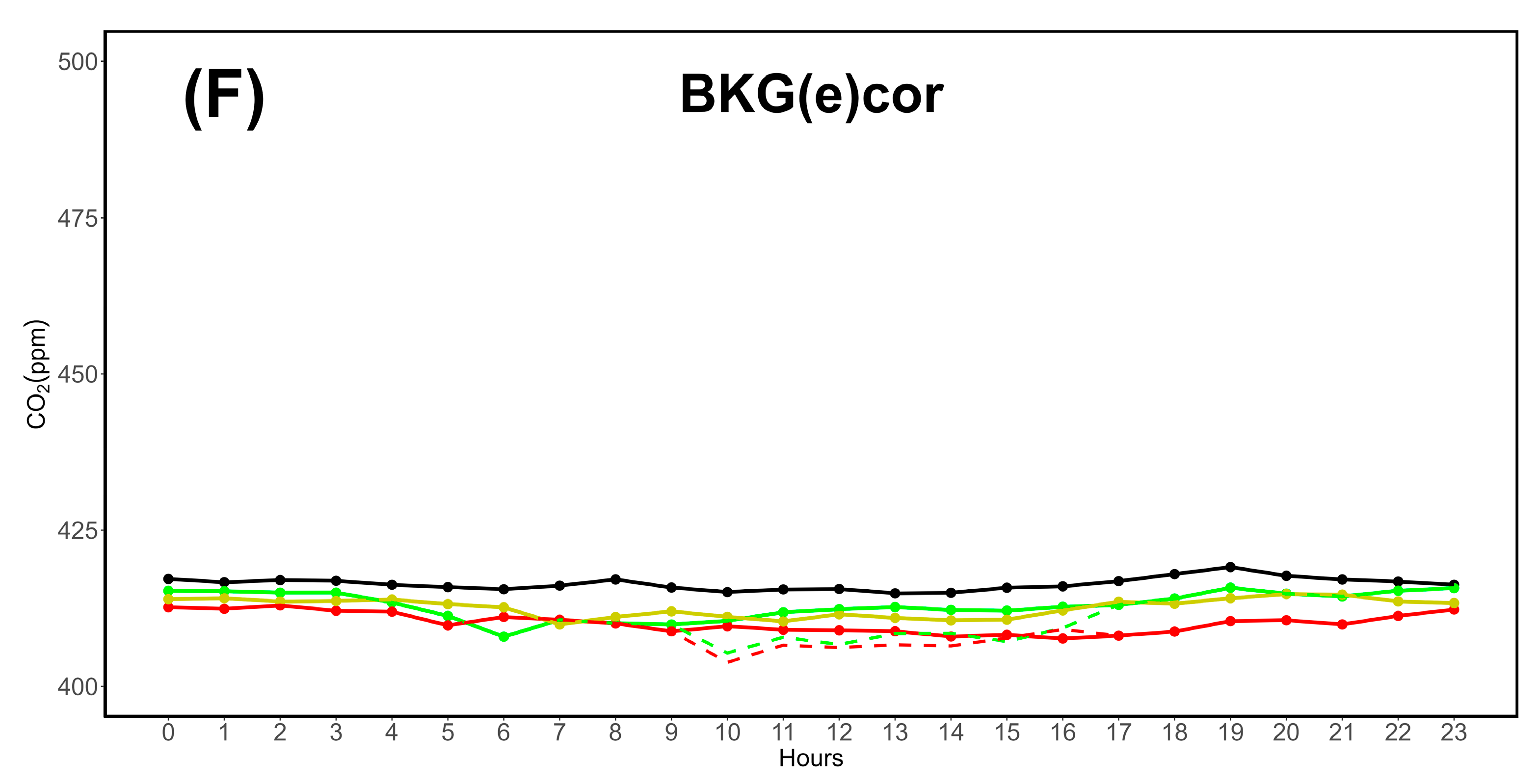

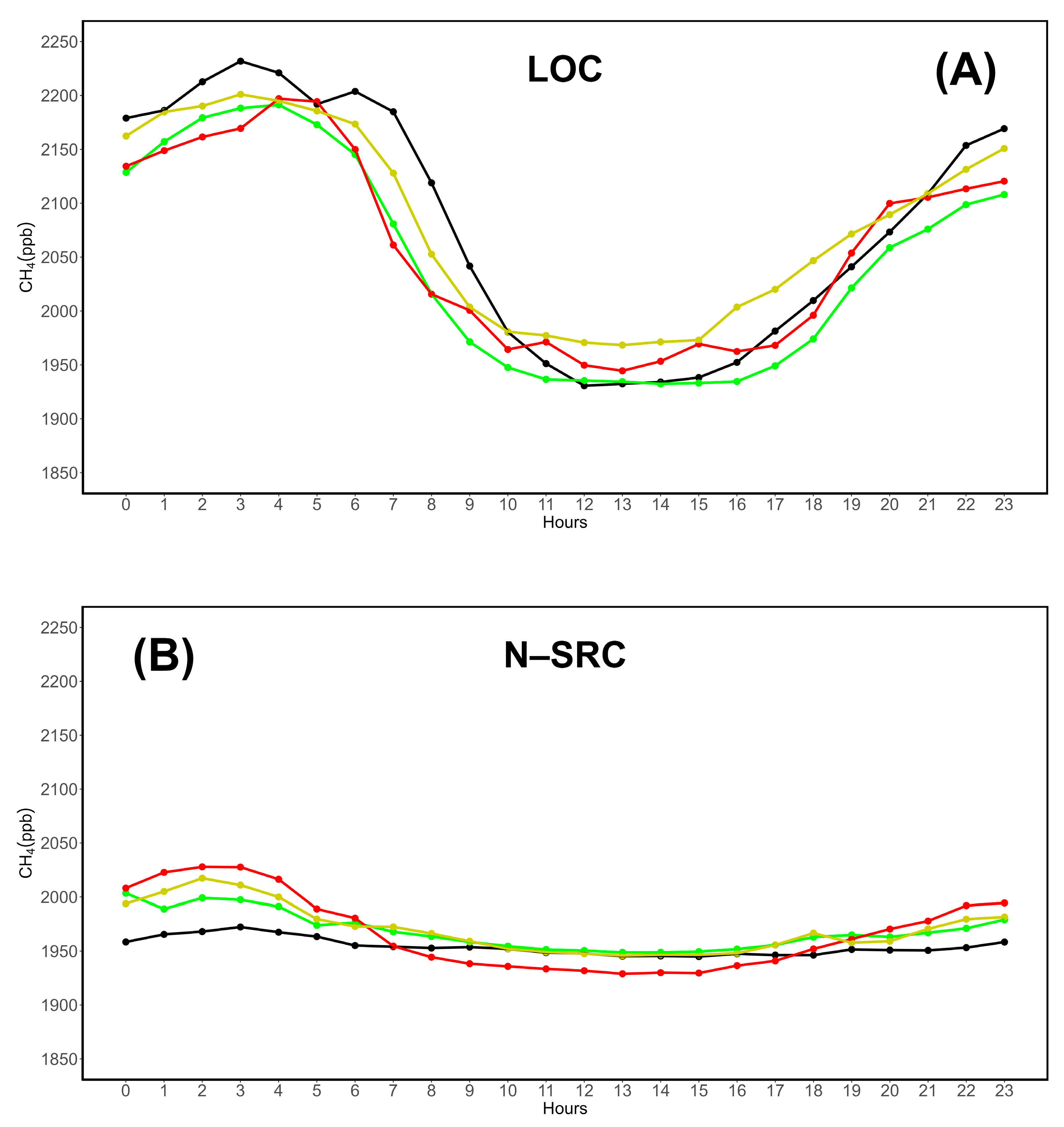

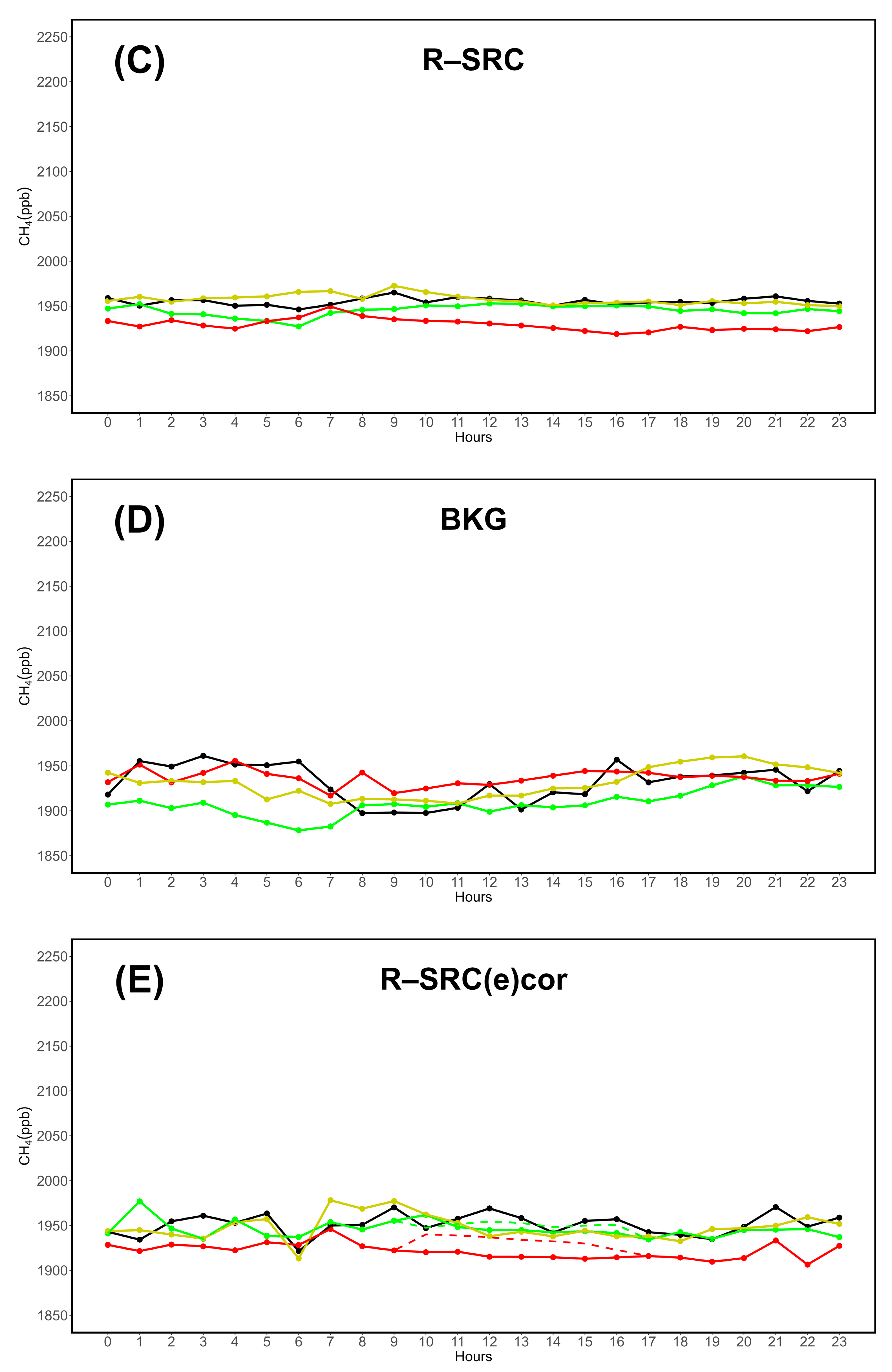

4.2. Assessment of Daily Cycles

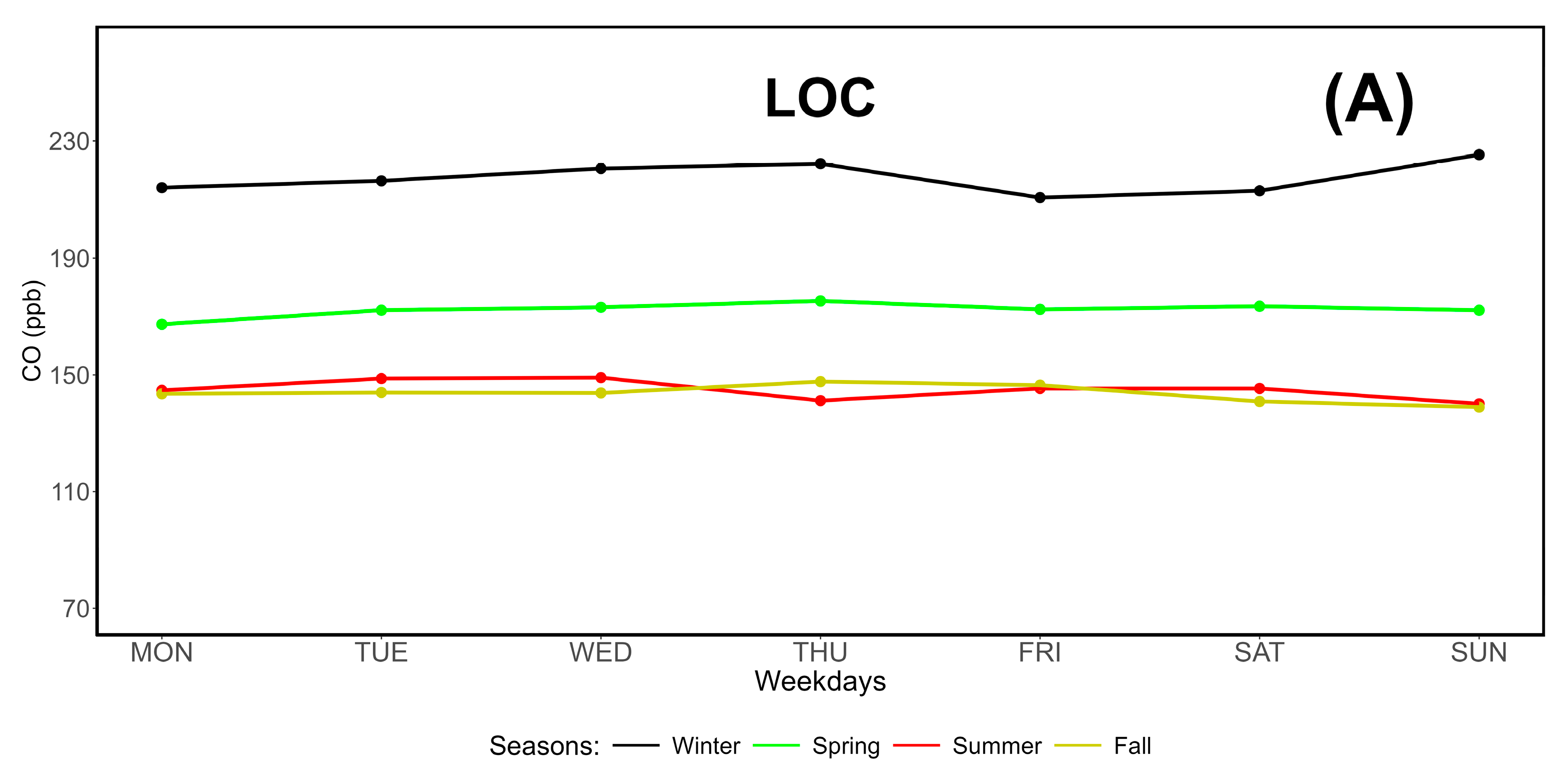

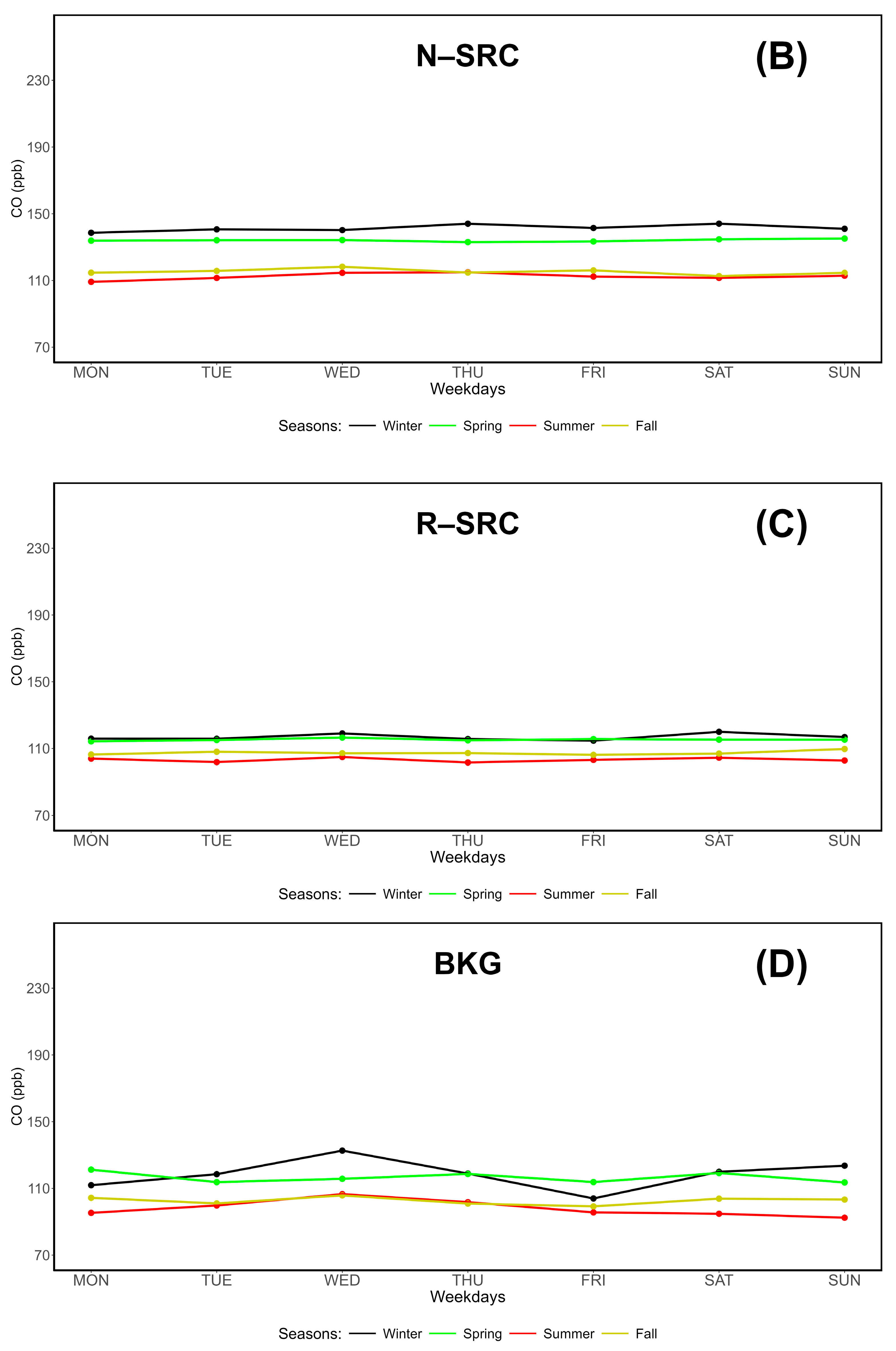

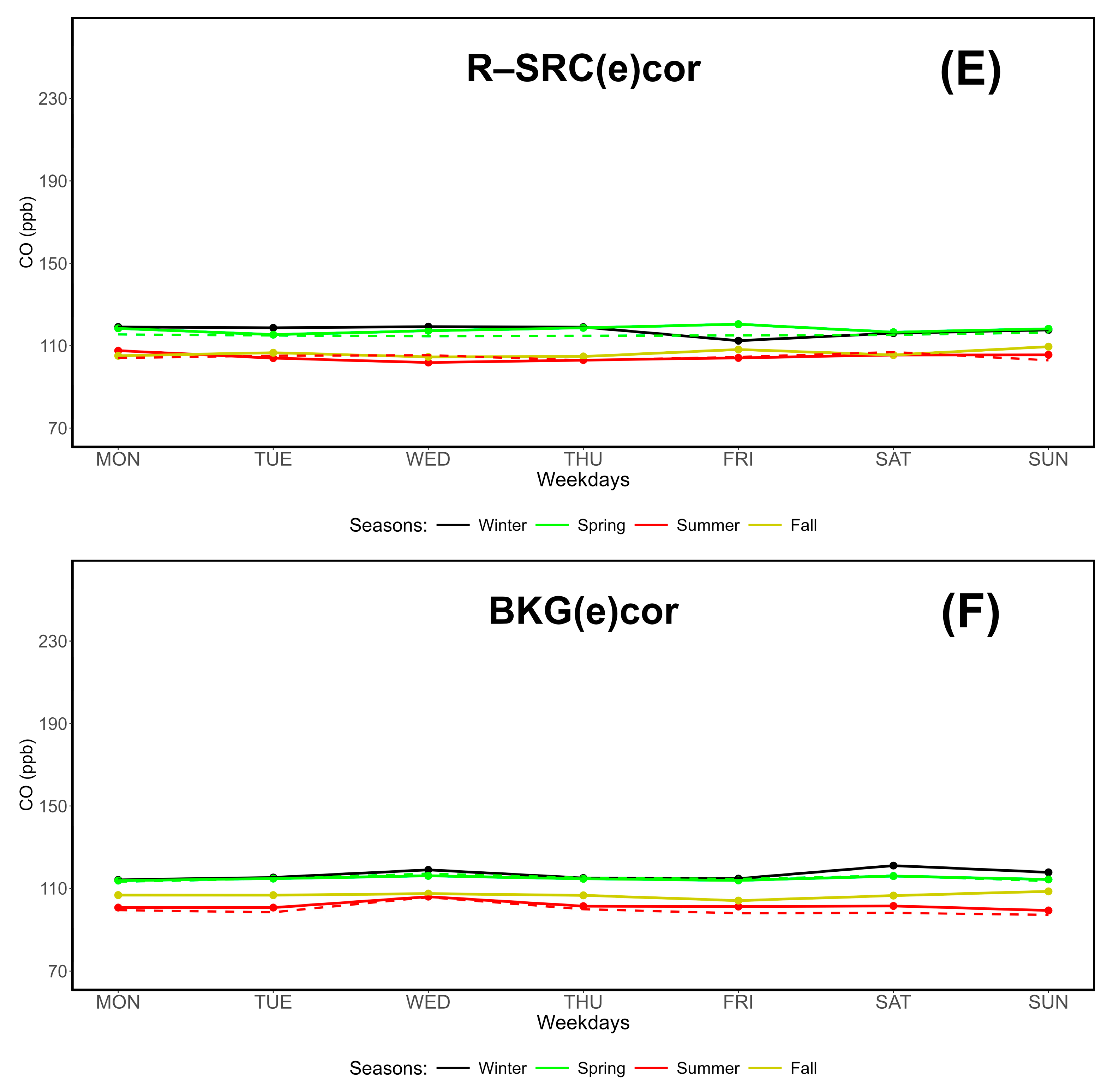

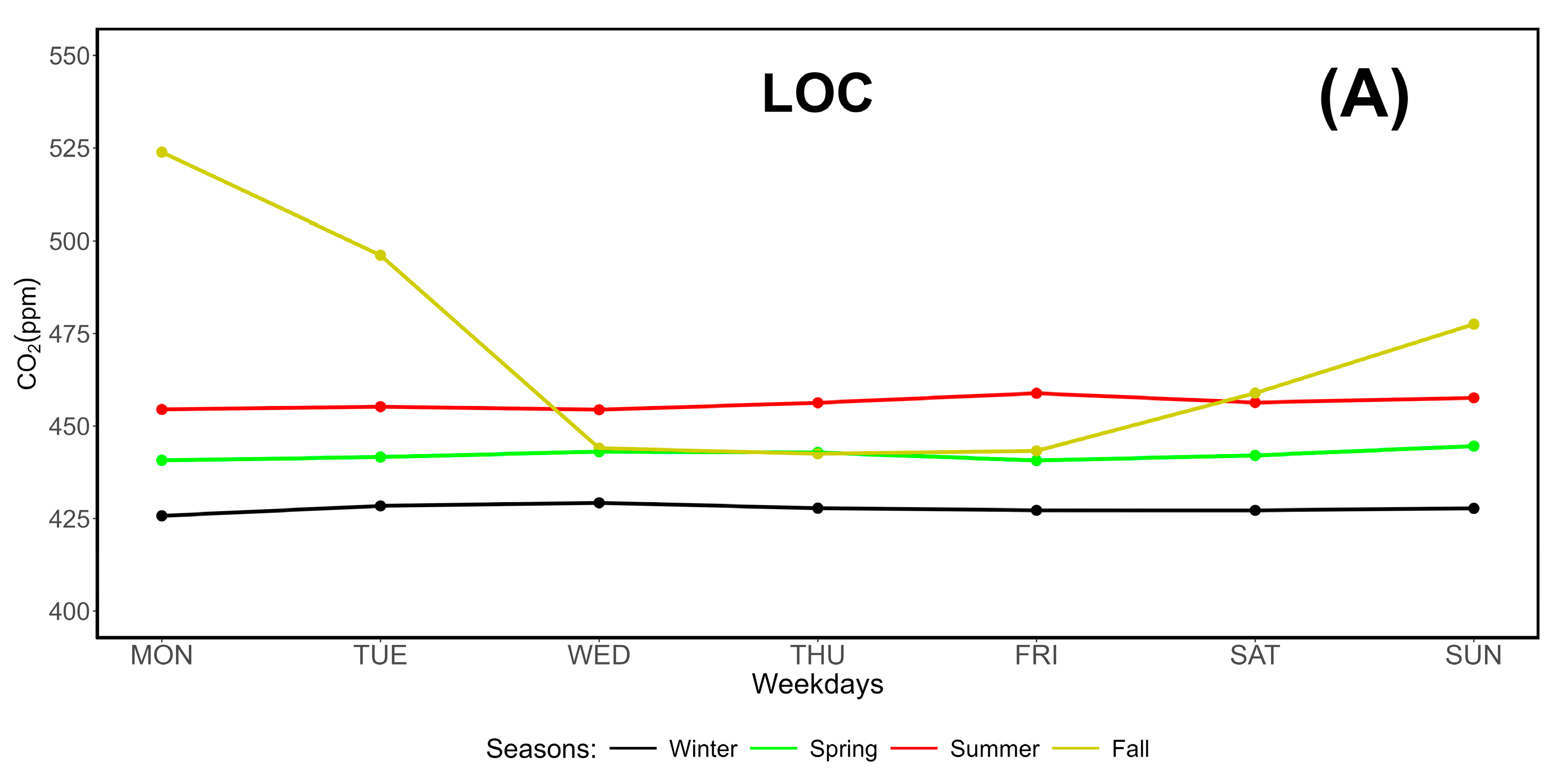

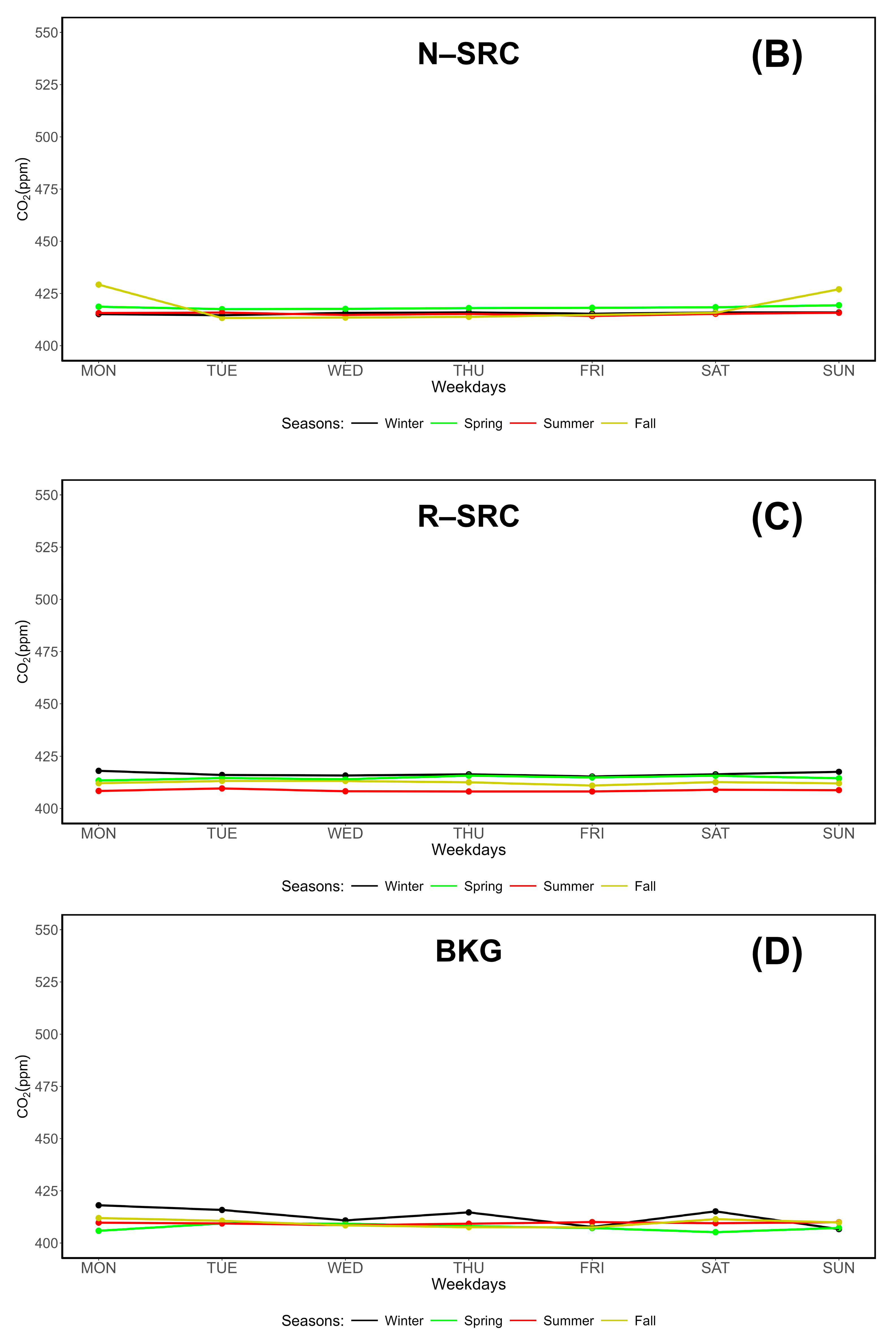

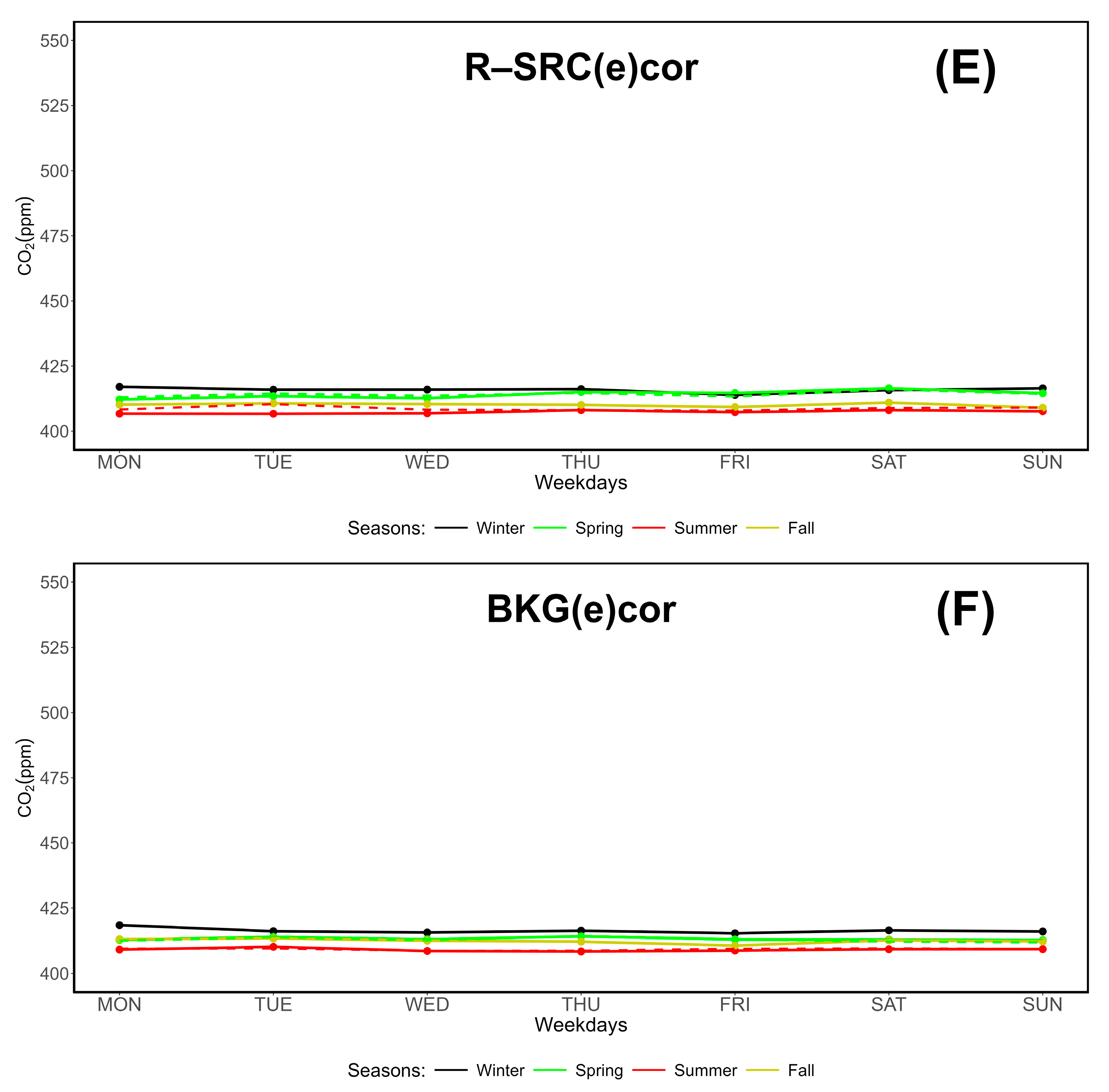

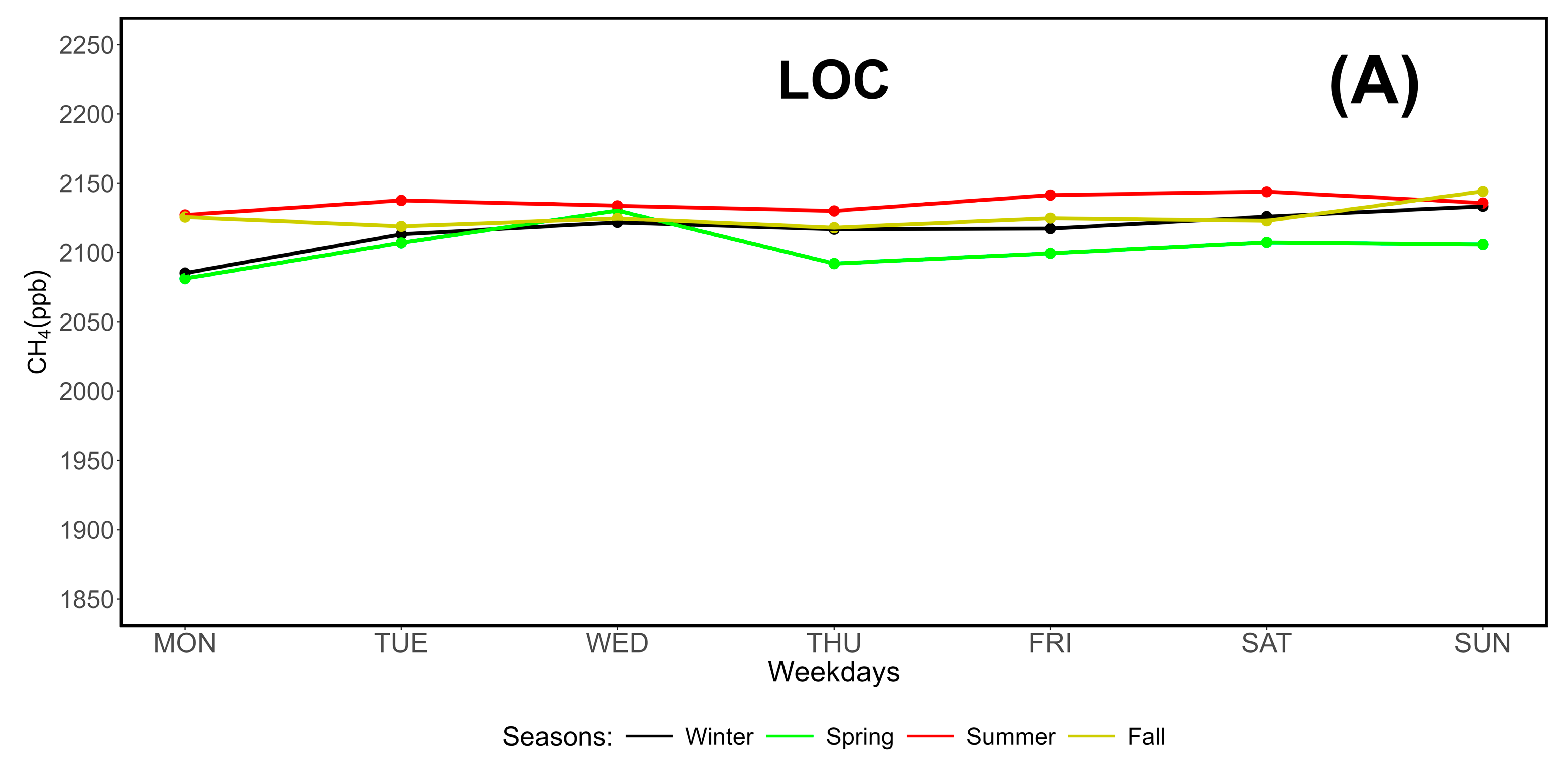

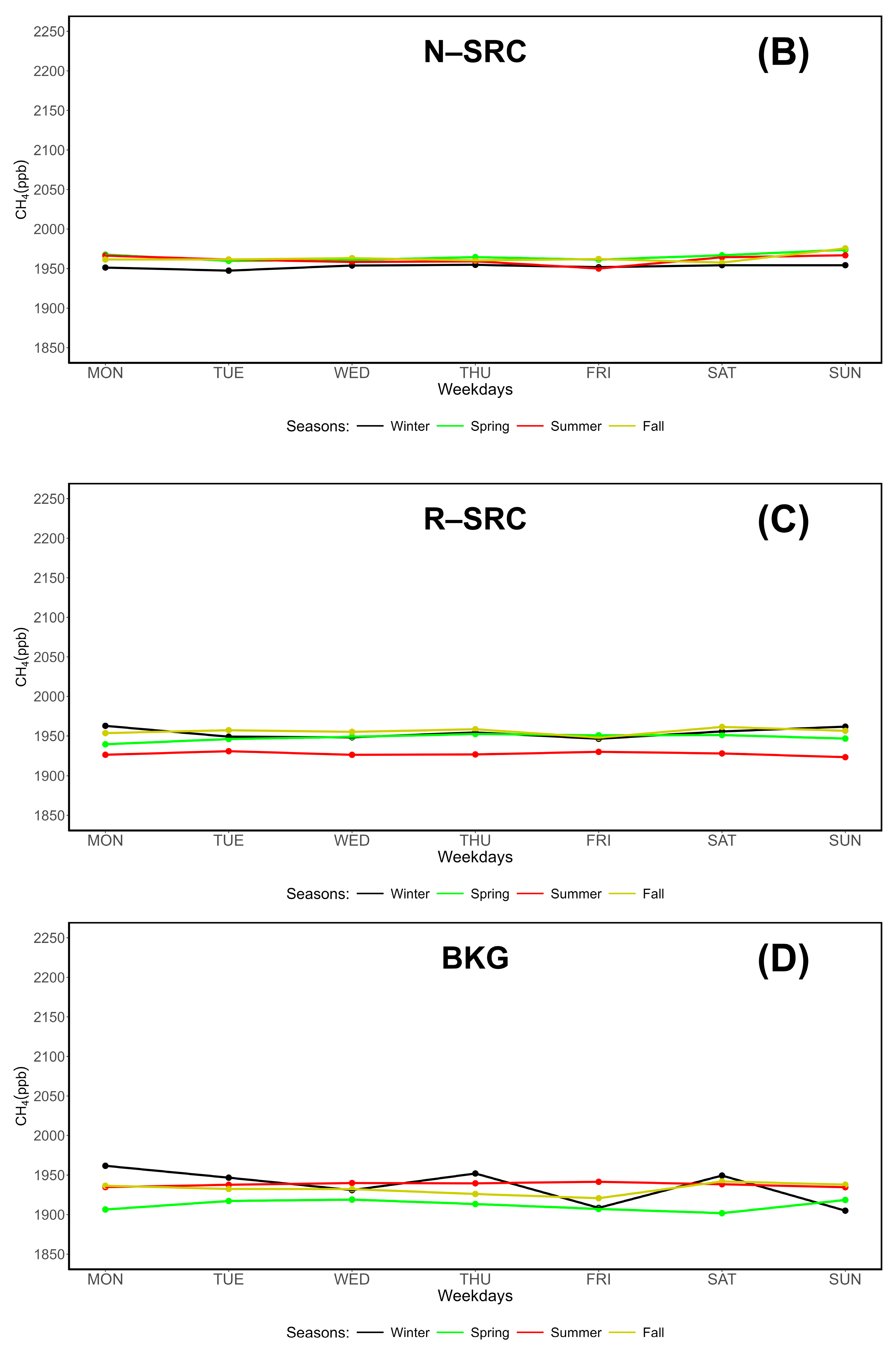

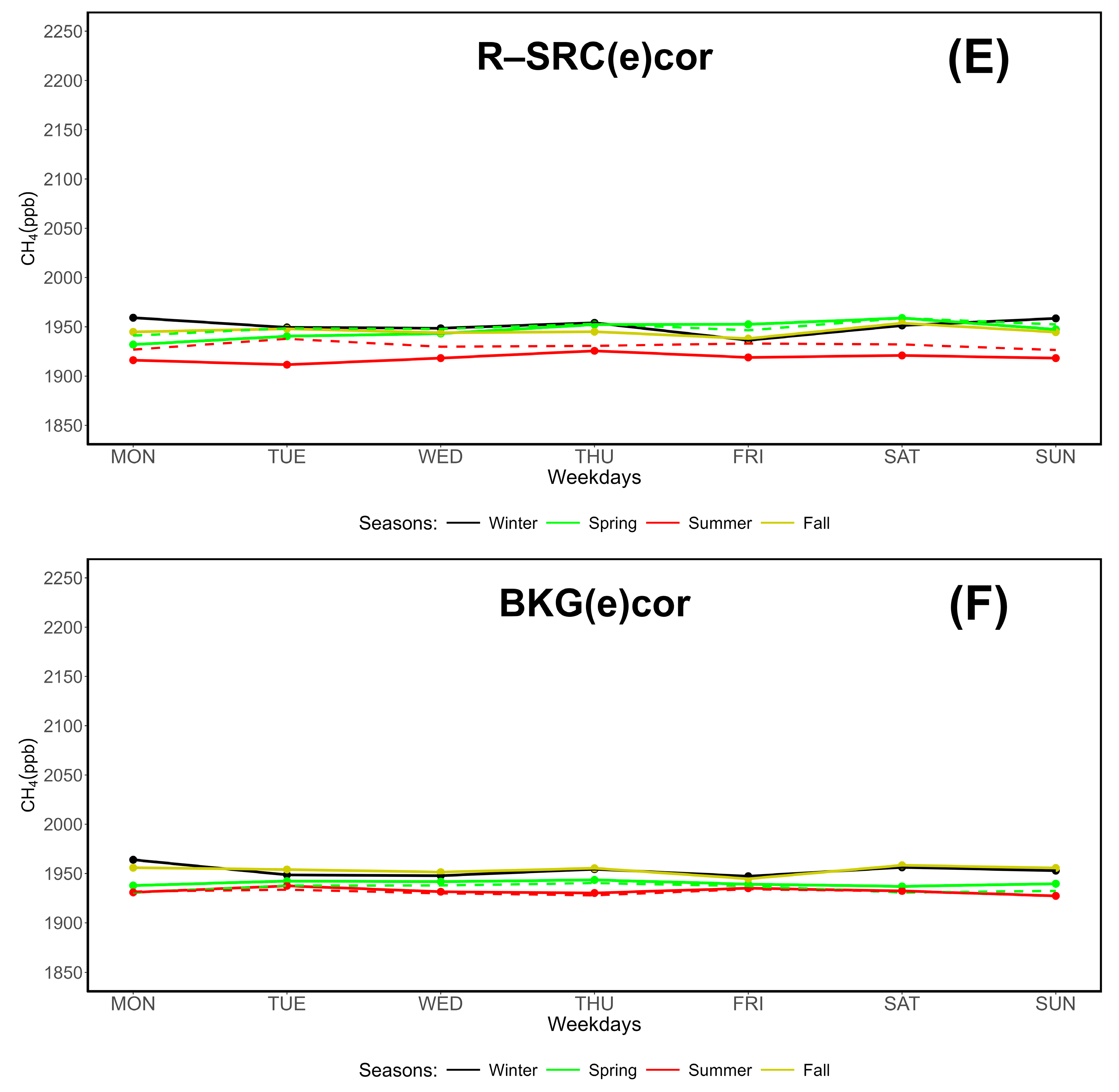

4.3. Weekly Cycle Variability

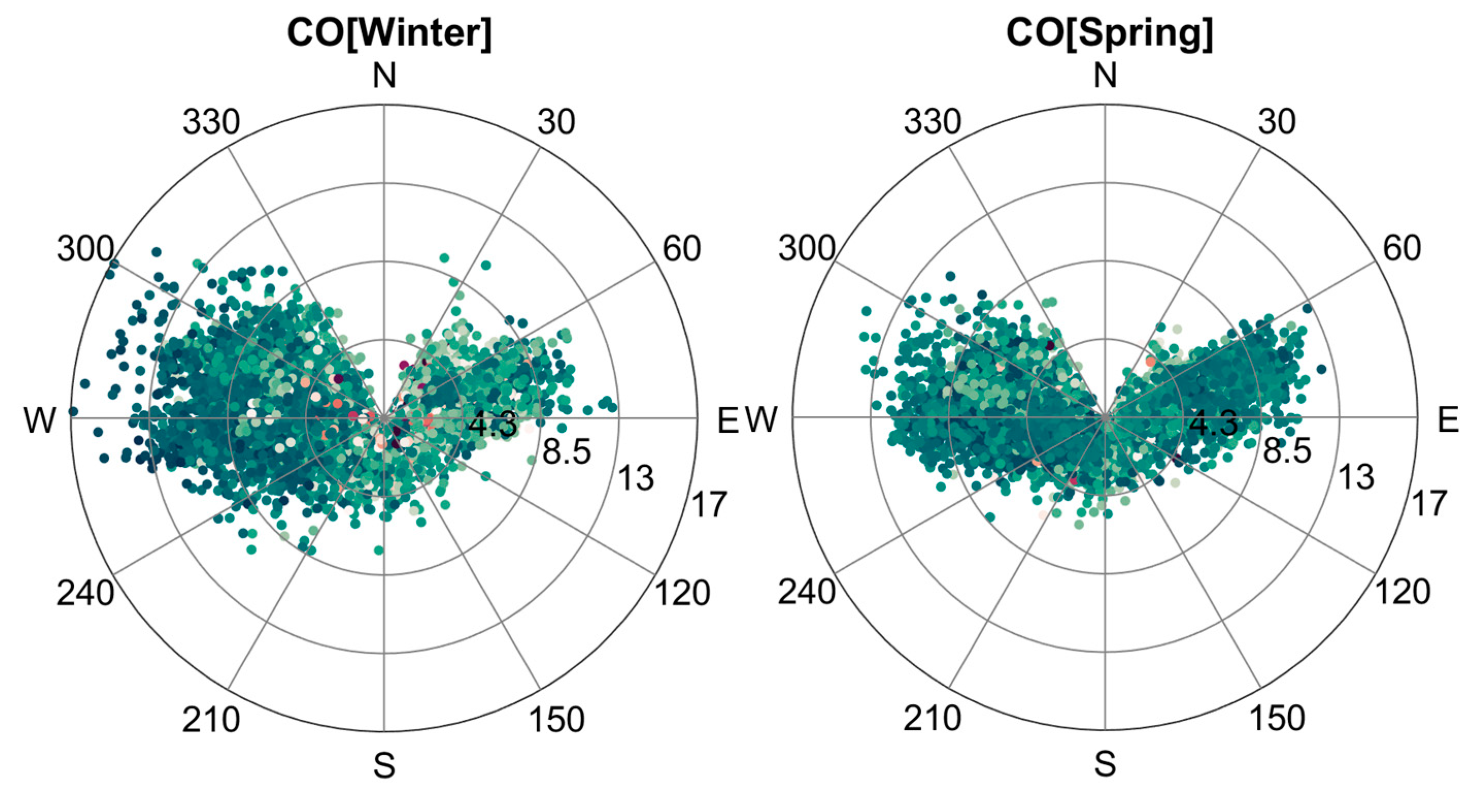

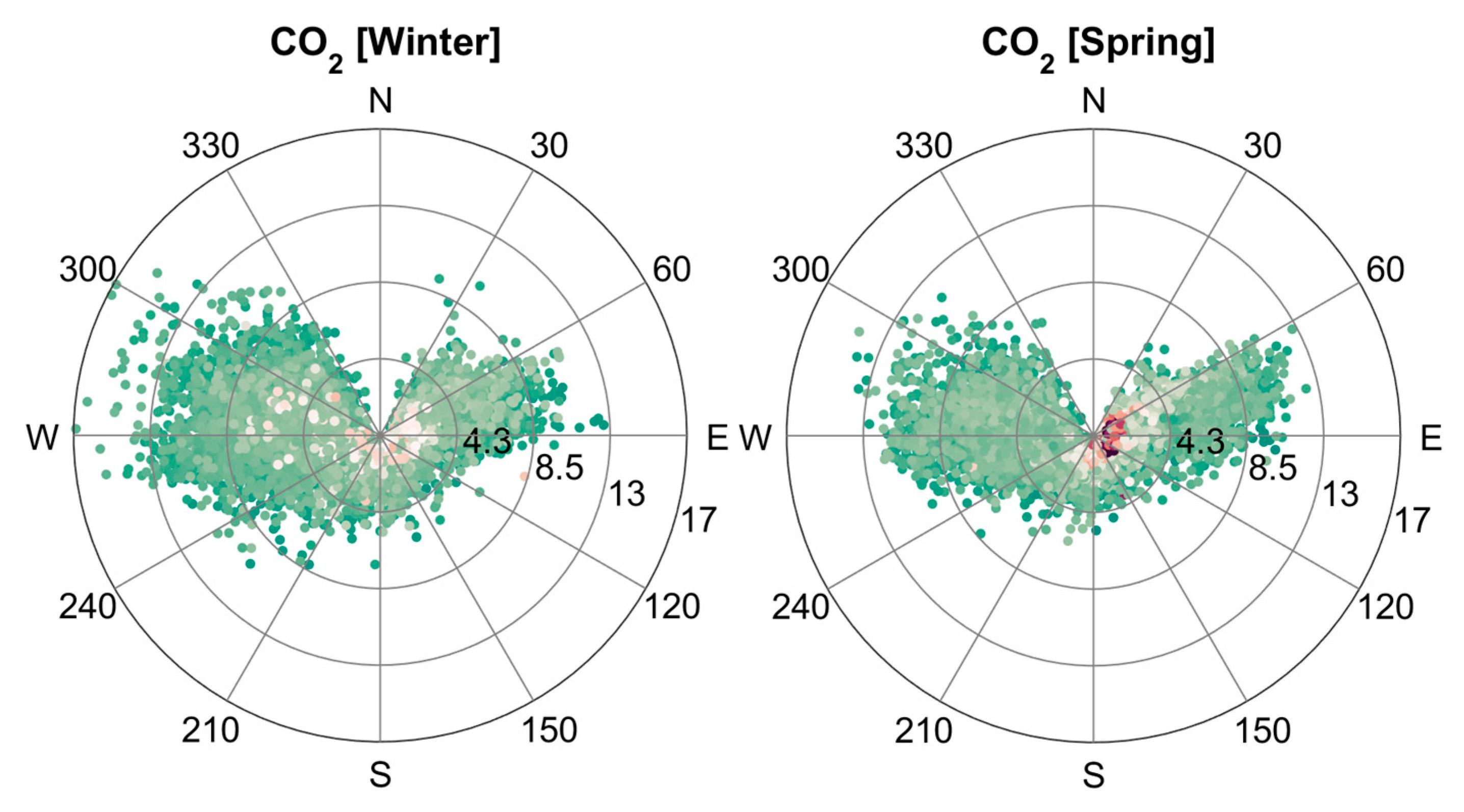

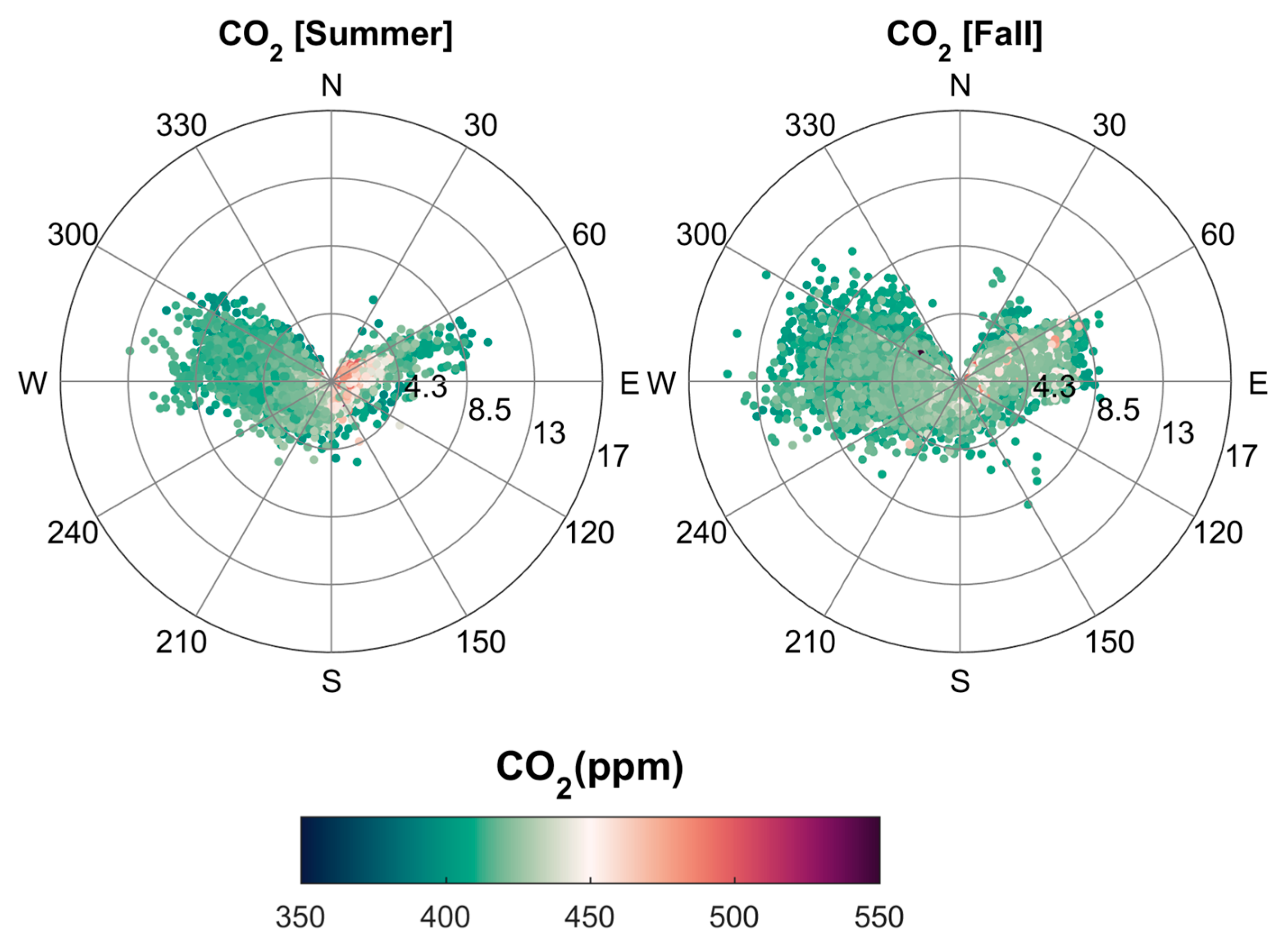

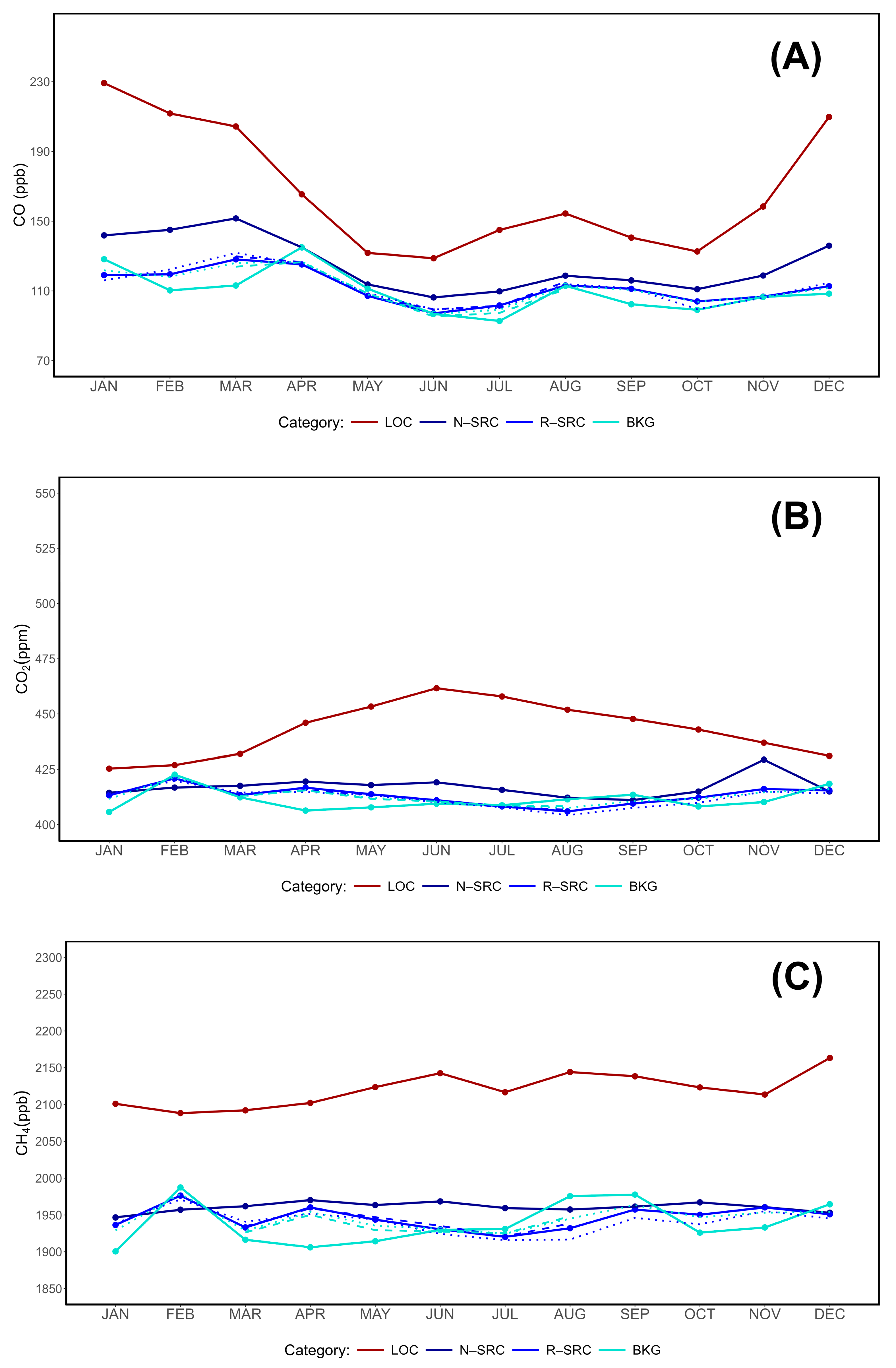

4.4. Seasonal Variability by Wind Sector

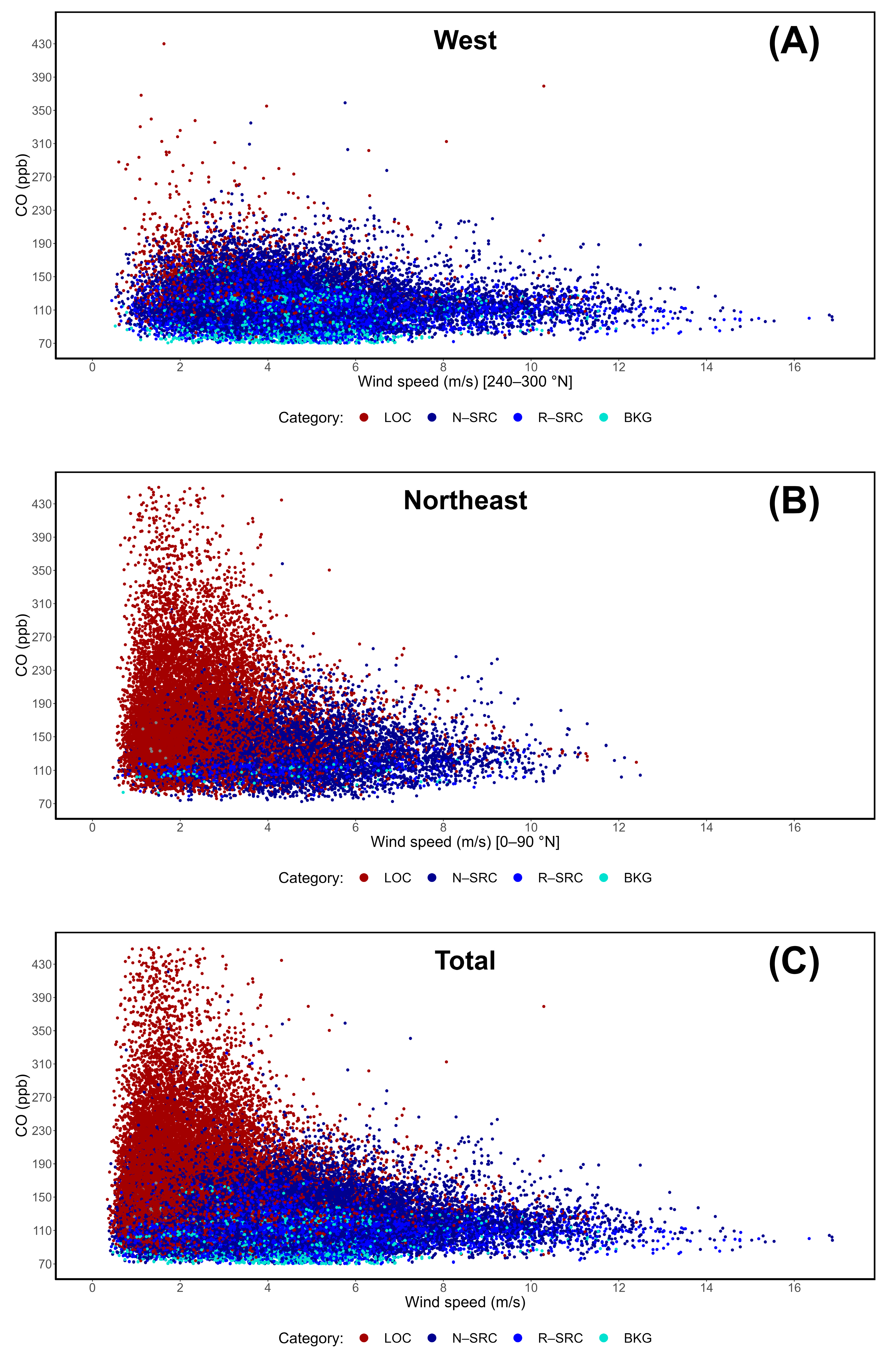

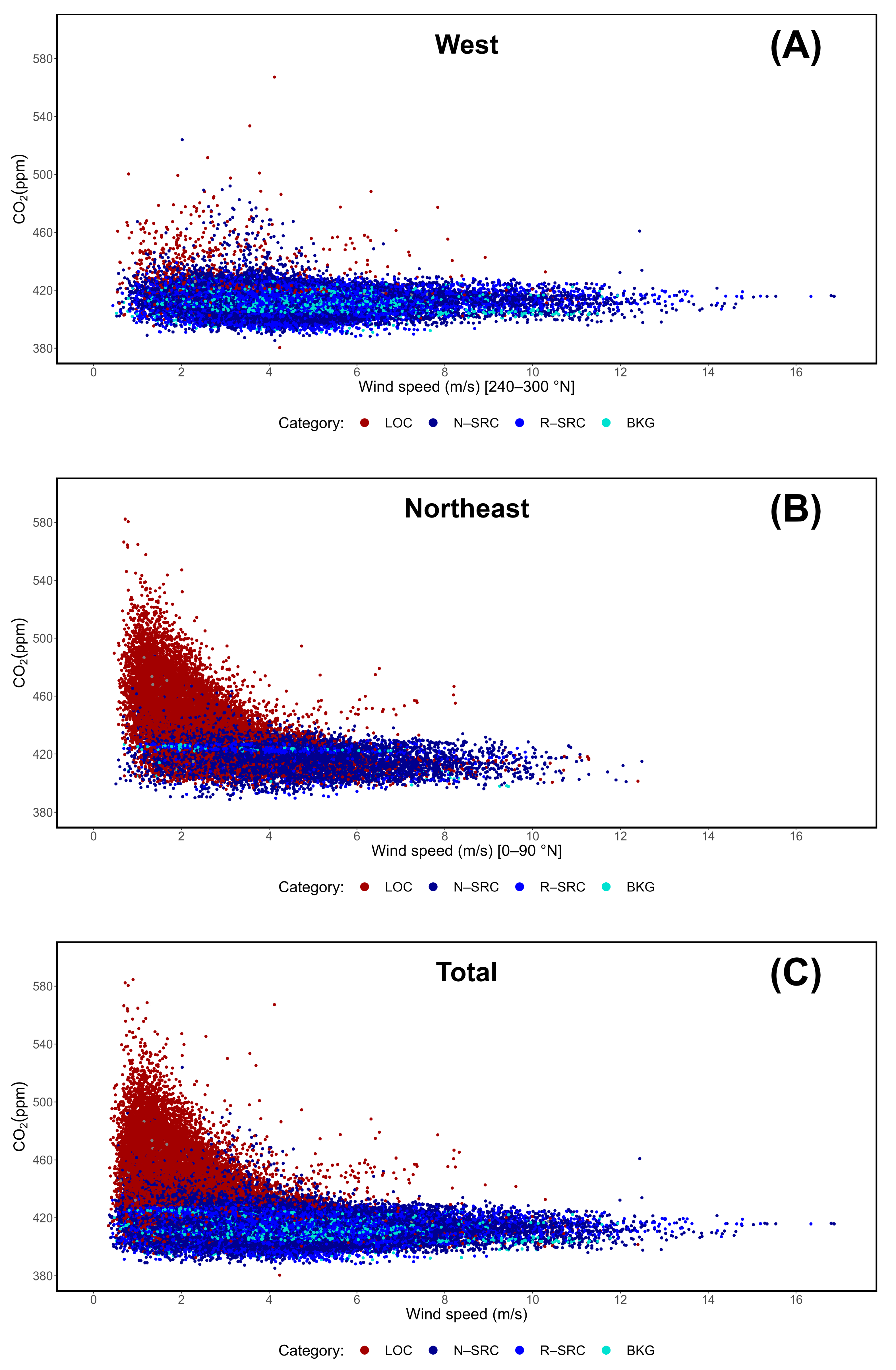

4.5. Correlations with Wind Speed by Corridors

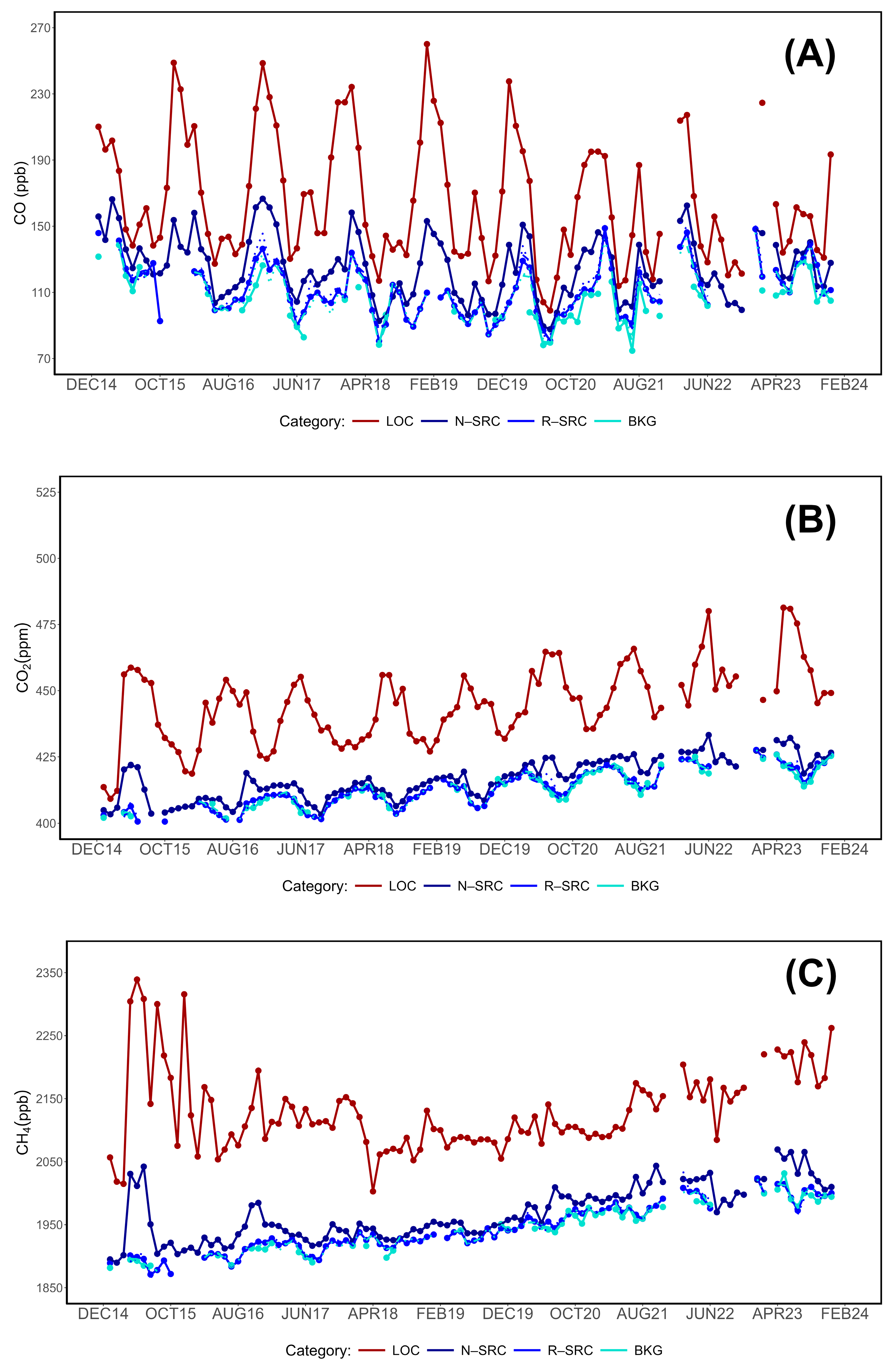

4.6. Infra- and Multi-Year Variability

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stevens, R.K.; Dzubay, T.G.; Lewis, C.W.; Shaw, R.W., Jr. Source apportionment methods applied to the determination of the origin of ambient aerosols that affect visibility in forested areas. Atmos. Environ. 1984, 18, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.J.; Kneip, T.J.; Daisey, J.M. Source apportionment of carbonaceous aerosol in New York City by multiple linear regression. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 1985, 35, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.A.K.; Rasmussen, R.A. Carbon monoxide in an urban environment: application of a receptor model for source apportionment. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 1988, 38, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, G.T.; Korsog, P.E. Atmospheric concentrations and regional source apportionments of sulfate, nitrate and sulfur dioxide in the Berkshire mountains in western Massachusetts. Atmos. Environ. 1989, 23, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Fisher, R.E.; Lowry, D.; France, J.L.; Allen, G.; Bakkaloglu, S.; Broderick, T.J.; Cain, M.; Coleman, M.; Fernandez, J.; et al. Methane Mitigation: Methods to Reduce Emissions, on the Path to the Paris Agreement. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58, e2019RG000675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzeri, G.; Graven, H.; Xu, X.; Saboya, E.; Blyth, L.; Manning, A.J.; Chawner, H.; Wu, D.; Hammer, S. Radiocarbon Measurements Reveal Underestimated Fossil CH4 and CO2 Emissions in London. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducruet, C.; Polo Martin, B.; Sene, M.A.; Lo Prete, M.; Sun, L.; Itoh, H.; Pigné, Y. Ports and their influence on local air pollution and public health: A global analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, T.; De Donno, A.; Serio, F.; Genga, A. Source Apportionment of PM10 as a Tool for Environmental Sustainability in Three School Districts of Lecce (Apulia). Sustainability 2024, 16, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, D.L.; Dzolov, G.D.; Sirakov, D.E. Effect of planetary boundary layer on long-range transport and diffusion of pollutants. C. R. Acad. Bulg. Sci. 1979, 32, 1635–1637. [Google Scholar]

- McNider, R.T.; Moran, M.D.; Pielke, R.A. Influence of diurnal and inertial boundary-layer oscillations on long-range dispersion. Atmos. Environ. 1988, 22, 2445–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tie, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Tian, H.; Bi, K.; Jin, Y.; Chen, P. In-Situ Aircraft Measurements of the Vertical Distribution of Black Carbon in the Lower Troposphere of Beijing, China, in the Spring and Summer Time. Atmosphere 2015, 6, 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, A.; Freney, E.; Chauvigné, A.; Baray, J.-L.; Rose, C.; Picard, D.; Colomb, A.; Hadad, D.; Abboud, M.; Farah, W.; Sellegri, K. Seasonal Variation of Aerosol Size Distribution Data at the Puy de Dôme Station with Emphasis on the Boundary Layer/Free Troposphere Segregation. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptis, I.-P.; Kazadzis, S.; Amiridis, V.; Gkikas, A.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Mihalopoulos, N. A Decade of Aerosol Optical Properties Measurements over Athens, Greece. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S. Relationships between Springtime PM2.5, PM10, and O3 Pollution and the Boundary Layer Structure in Beijing, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Calidonna, C.R.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Lo Feudo, T. Peplospheric influences on local greenhouse gas and aerosol variability at the Lamezia Terme WMO/GAW regional station in Calabria, Southern Italy: a multiparameter investigation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tov, D.A.S.; Peleg, M.; Matveev, V.; Mahrer, Y.; Seter, I.; Luria, M. Recirculation of polluted air masses over the East Mediterranean coast. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furutani, H.; Dall’osto, M.; Roberts, G.C.; Prather, K.A. Assessment of the relative importance of atmospheric aging on CCN activity derived from field observations. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 3130–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espina-Martin, P.; Perdrix, E.; Alleman, L.Y.; Coddeville, P. Origins of the seasonal variability of PM2.5 sources in a rural site in Northern France. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 333, 120660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D.D.; Allen, D.T.; Bates, T.S.; Estes, M.; Fehsenfeld, F.C.; Feingold, G.; Ferrare, R.; Hardesty, R.M.; Meagher, J.F.; Nielsen-Gammon, J.W.; et al. Overview of the Second Texas Air Quality Study (TexAQS II) and the Gulf of Mexico Atmospheric Composition and Climate Study (GoMACCS). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.T.; Allan, J.D.; Bower, K.N.; Highwood, E.J.; Liu, D.; McMeeking, G.R.; Northway, M.J.; Williams, P.I.; Krejci, R.; Coe, H. Airborne measurements of the spatial distribution of aerosol chemical composition across Europe and evolution of the organic fraction. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 4065–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, J.E.; Atherton, C.S.; Dignon, J.; Ghan, S.J.; Walton, J.J.; Hameed, S. Tropospheric nitrogen—A 3-dimensional study of sources, distributions, and deposition. J. Geophys. Res. - Atmos. 1991, 96, 959–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, M.; Parrish, D.D.; Buhr, M.P.; Norton, R.B.; Fehsenfeld, F.C.; Anlauf, K.G.; Bottenheim, J.W.; Tang, Y.Z.; Wiebe, H.A.; Roberts, J.M.; et al. Correlation of ozone with NOy in photochemically aged air. J. Geophys. Res. – Atmos. 1993, 98, 2917–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J.; Heikes, E.G.; Fan, S.-M.; Logan, J.A.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Bradshaw, J.D.; Singh, H.B.; Gregory, G.L.; Talbot, R.W.; Blake, D.R.; Sachse, G.W. Origin of ozone and NOx in the tropical troposphere: A photochemical analysis of aircraft observations over the South Atlantic basin. J. Geophys. Res. - Atmos. 1996, 101, 24235–24250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauglustaine, D.A.; Emmons, L.K.; Newchurch, M.; Brasseur, G.P.; Takao, T.; Matsubara, K.; Johnson, J.; Ridley, B.; Stith, J.; Dye, J. On the role of lightning NOx in the formation of tropospheric ozone plumes: A global model perspective. J. Atmos. Chem. 2001, 38, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henne, S.; Dommen, J.; Neininger, B.; Reimann, S.; Staehelin, J.; Prévôt, A.S.H. Influence of mountain venting in the Alps on the ozone chemistry of the lower free troposphere and the European pollution export. J. Geophys. Res. 2005, 110(D22), 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.F.; Mantilla, E.; Millán, M.M. Using measured and modeled indicators to assess ozone-NOx-VOC sensitivity in a western Mediterranean coastal environment. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 7167–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; Moller, S.J.; Read, K.A.; Lewis, A.C.; Mendes, L.; Carpenter, L.J. Year-round measurements of nitrogen oxides and ozone in the tropical North Atlantic marine boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. – Atmos. 2009, 114, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroidis, I.; Chaloulakou, A. Long-term trends of primary and secondary NO2 production in the Athens area. Variation of the NO2/NOx ratio. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 6872–6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenger, J. Urban air quality. Atmos. Environ. 1999, 33, 4877–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J. Introduction to Atmospheric Chemistry; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Colvile, R.N.; Hutchinson, E.J.; Mindell, J.S.; Warren, R.F. The transport sector as a source of air pollution. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 1537–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics; A Wiley-Inter Science Publication, John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers, S.D.; Westmoreland, E.; de Jong, M.C.; Williams, M.L.; Carslaw, D.C. Trends in NOx and NO2 emissions from road traffic in Great Britain. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 54, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Beirle, S.; Zhang, Q.; Dörner, S.; He, K.; Wagner, T. NOx lifetimes and emissions of cities and power plants in polluted background estimated by satellite observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 5283–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehelin, J.; Thudium, J.; Buheler, R.; Volz-Thomas, A.; Graber, W. Trends in surface ozone concentrations at Arosa (Switzerland). Atmos. Environ. 1994, 28, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyshlyaev, S.P.; Galin, V.Y.; Blakitnaya, P.A.; Jakovlev, A.R. Numerical Modeling of the Natural and Manmade Factors Influencing Past and Current Changes in Polar, Mid-Latitude and Tropical Ozone. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S. Stratospheric ozone depletion: A review of concepts and history. Rev. Geophys. 1999, 37, 275–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.B.; Weatherhead, E.C.; Stevermer, A.; Austin, J.; Brühl, C.; Fleming, E.L.; De Grandpré, J.; Grewe, V.; Isaksen, I.; Pitari, G.; et al. Comparison of recent modeled and observed trends in total column ozone. J. Geophys. Res. - Atmos. 2006, 111, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorova, T.; Rozanov, E.; Arsenovic, P.; Sukhodolov, T. Ozone Layer Evolution in the Early 20th Century. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palli, D.; Sera, F.; Giovannelli, L.; Masala, G.; Grechi, D.; Bendinelli, B.; Caini, S.; Dolara, P. Environmental ozone exposure and oxidative DNA damage in adult residents in Florence, Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 1521–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuvolone, D.; Petri, D.; Voller, F. The effects of ozone on human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 8074–8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashock, D.A.; DeLang, M.N.; Becker, J.S.; Serre, M.L.; West, J.J.; Chang, K.-L.; Cooper, O.R.; Anenberg, S.C. Estimates of ozone concentrations and attributable mortality in urban, peri-urban and rural areas worldwide in 2019. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 054023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstrup, H.; Åström, C.; Orru, H. Daily Mortality in Different Age Groups Associated with Exposure to Particles, Nitrogen Dioxide and Ozone in Two Northern European Capitals: Stockholm and Tallinn. Environments 2022, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donzelli, G.; Suarez-Varela, M.M. Tropospheric Ozone: A Critical Review of the Literature on Emissions, Exposure, and Health Effects. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlea, E.J. , Herndon, S.C.; Nelson, D.D.; Volkamer, R.M.; San Martini, F.; Sheehy, P.M.; Zahniser, M.S.; Shorter, J.H.; Wormhoudt, J.C.; Lamb, B.K.; et al. Evaluation of nitrogen dioxide chemiluminescence monitors in a polluted urban environment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 2691–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V.S.B.; Freitas, E.D.; Martins, L.D.; Martins, J.A.; Mazzoli, C.R.; de Fátima Andrade, M. Air quality status and trends over the Metropolitan Area of São Paulo, Brazil as a result of emission control policies. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 47, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, N.M. Air quality warnings and temporary driving bans: Evidence from air pollution, car trips, and mass-transit ridership in Santiago. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2021, 108, 102454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintomide Ajayi, S.; Anum Adam, C.; Dumedah, G.; Adebanji, A.; Ackaah, W. The impact of traffic mobility measures on vehicle emissions for heterogeneous traffic in Lagos City. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbacher, M.; Zellweger, C.; Schwarzenbach, B.; Bugmann, S.; Buchmann, B.; Ordóñez, C.; Prévôt, A.S.H.; Hueglin, C. Nitrogen oxide measurements at rural sites in Switzerland: Bias of conventional measurement techniques. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, A.M.; Peters, J.W.; Smith, J.P.; Pitts, J.N. Jr. Response of commercial chemiluminescence NO–NO2 analyzers to other nitrogen-containing compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1974, 8, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, D.; Harrison, J. Response of chemiluminescence NOx analyzers and ultraviolet ozone analyzers to organic air pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1985, 19, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, R.; Baumann, R. Comparison of 4 different types of commercially available monitors for nitrogen oxides with test gas mixtures of NH3, HNO3, PAN and VOC and in ambient air, paper presented at EMEP Workshop on Measurements of Nitrogen-Containing Compounds. EMEP/CCC Report 1, 1993, Les Diablerets, Switzerland.

- Navas, M.J.; Jiménez, A.M.; Galán, G. Air analysis: determination of nitrogen compounds by chemiluminescence. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 3603–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, M.R.; Kirby, C.; Cape, J.N. Systematic biases in measurement of urban nitrogen dioxide using passive diffusion samplers. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2000, 62, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerboles, M.; Lagler, F.; Rembges, D.; Brun, C. Assessment of uncertainty of NO2 measurements by the chemiluminescence method and discussion of the quality objective of the NO2 European Directive. J. Environ. Monit. 2003, 5, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickerson, R.R.; Anderson, D.C.; Ren, X. On the use of data from commercial NOx analyzers for air pollution studies. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 214, 116873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, M.R.; Laxen, D.P.H.; Marner, B.B. Biases in the Measurement of Ambient Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) by Palmes Passive Diffusion Tube: A Review of Current Understanding. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, T.; Xue, L.K.; Louie, P.K.K.; Luk, C.W.Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, S.L.; Chai, F.H.; Wang, W.X. Evaluating the uncertainties of thermal catalytic conversion in measuring atmospheric nitrogen dioxide at four differently polluted sites in China. Atmos. Environ. 2013, 76, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, B.; Oh, S. Seasonal variations in the NO2 artifact from chemiluminescence measurements with a molybdenum converter at a suburban site in Korea (downwind of the Asian continental outflow) during 2015–2016. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 165, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Calzolari, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Dinoi, A.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Sferlazzo, D.; Di Iorio, T.; et al. Investigation of reactive gases and methane variability in the coastal boundary layer of the central Mediterranean basin. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Gullì, D.; Lo Feudo, T.; Ammoscato, I.; Avolio, E.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; et al. Cyclic and multi-year characterization of surface ozone at the WMO/GAW coastal station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): implications for local environment, cultural heritage, and human health. Environments 2024, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Integrated analysis of methane cycles and trends at the WMO/GAW station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Anthropic-induced variability of greenhouse gases and aerosols at the WMO/GAW coastal site of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): towards a new method to assess the weekly distribution of gathered data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, L.S. Ambient carbon monoxide and its fate in the atmosphere. J. Air Pollut. Control Associ. 1968, 18, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, L.S. Carbon monoxide in the biosphere: sources, distribution, and concentrations. J. Geophys. Res. – Oc. Atm. 1973, 78, 5293–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.P.; Emmons, L.K.; Hauglustaine, D.A.; Chu, D.A.; Gille, J.C.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Pétron, G.; Yurganov, L.N.; Giglio, L.; Deeter, M.N.; et al. Observations of carbon monoxide and aerosols from the Terra satellite: Northern Hemisphere variability. J. Geophys. Res. - Atmos. 2004, 109, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.A.K.; Rasmussen, R.A. The global cycle of carbon monoxide: Trends and mass balance. Chemosphere 1990, 20, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenco, A. Variations of CO and O3 in the troposphere: Evidence of O3 photochemistry. Atmos. Environ. 1986, 20, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, M.J. Lifetimes and time scales in atmospheric chemistry. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2007, 365, 1705–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.A.K.; Rasmussen, R.A. Carbon Monoxide in the Earth’s Atmosphere: Increasing Trend. Science 1984, 223, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Chevallier, F.; Ciais, P.; Yin, Y.; Deeter, M.N.; Worden, H.M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; He, K. Rapid decline in carbon monoxide emissions and export from East Asia between years 2005 and 2016. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 044007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, P.E.; Brewer, S.C.; Arnold, J.D.; Moritz, M.A. Large wildfire trends in the western United States, 1984–2011. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 2928–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, R.R.; Worden, H.M.; Park, M.; Francis, G.; Deeter, M.N.; Edwards, D.P.; Emmons, L.K.; Gaubert, B.; Gille, J.; Martínez-Alonso, S.; et al. Air pollution trends measured from Terra: CO and AOD over industrial, fire-prone, and background regions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. Quantifying and comparing fuel-cycle greenhouse-gas emissions: Coal, oil and natural gas consumption. Energy Policy 1990, 18, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheraga, J.D.; Leary, N.A. Improving the efficiency of policies to reduce CO2 emissions. Energy Policy 1992, 20, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danny Harvey, L.D. A guide to global warming potentials (GWPs). Energy Policy 1993, 21, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I.M. CO2 and climatic change: An overview of the science. Energy Convers. Manag. 1993, 34, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, C.D.; Whorf, T.P.; Wahlen, M.; van der Plichtt, J. Interannual extremes in the rate of rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide since 1980. Nature 1995, 375, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, D.; Brovkin, V. The millennial lifetime of fossil fuel CO2. Clim. Chang. 2008, 90, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, B.; Eriksson, E. Changes in the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere and sea due to fossil fuel combustion. Rossby Meml. Vol. 1959, 130–146. Available online: https://nsdl.library.cornell.edu/websites/wiki/index.php/PALE_ClassicArticles/GlobalWarming/Article8.html (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Komhyr, W.D.; Harris, T.B.; Waterman, L.S.; Chin, J.F.S.; Thoninh, K.W. Atmospheric carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa Observatory: 1. NOAA global monitoring for climatic change measurements with a nondispersive infrared analyzer, 1974-1985. J. Geophys. Res. – Atmos. 1989, 94, 8533–8547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoning, K.W.; Tans, P.P.; Komhyr, W.D. Atmospheric carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa Observatory: 2. Analysis of the NOAA GMCC data, 1974-1985. J. Geophys. Res. – Atmos. 1989, 94, 8549–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugokencky, E.J.; Houweling, S.; Bruhwiler, L.; Masarie, K.A.; Lang, P.M.; Miller, J.B.; Tans, P.P. Atmospheric methane levels off: Temporary pause or a new steady-state? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinn, R.G.; Huang, J.; Weiss, R.F.; Cunnold, D.M.; Fraser, P.J.; Simmonds, P.G.; McCulloch, A.; Harth, C.; Reimann, S.; Salameh, P.; et al. Evidence for variability of atmospheric hydroxyl radicals over the past quarter century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L07809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, M.J.; Holmes, C.D.; Hsu, J. Reactive greenhouse gas scenarios: Systematic exploration of uncertainties and the role of atmospheric chemistry. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L09803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhre, G.; Shindell, D.; Bréon, F.M.; Collins, W.; Fuglestvedt, J.; Huang, J.; Koch, D.; Lamarque, J.F.; Lee, D.; Mendoza, B.; et al. Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge, UK.; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Fahey, D.; Forster, P.M.; Newton, P.J.; Wit, R.C.N.; Lim, L.L.; Owen, B.; Sausen, R. Aviation and global climate change in the 21st century. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 3520–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clairotte, M.; Suarez-Bertoa, R.; Zardini, A.A.; Giechaskiel, B.; Pavlovic, J.; Valverde, V.; Ciuffo, B.; Astorga, C. Exhaust emission factors of greenhouse gases (GHGs) from European road vehicles. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Fahey, D.W.; Skowron, A.; Allen, M.R.; Burkhardt, U.; Chen, Q.; Doherty, S.J.; Freeman, S.; Forster, P.M.; Fuglestvedt, J.; et al. The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 244, 117834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunois, M.; Stavert, A.R.; Poulter, B.; Bousquet, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Raymond, P.A.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Houweling, S.; Patra, P.K.; et al. The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1561–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Peng, S.; Ciais, P.; Saunois, M.; Dangal, S.R.S.; Herrero, M.; Havlík, P.; Tian, H.; Bousquet, P. Revisiting enteric methane emissions from domestic ruminants and their δ13CCH4 source signature. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Manning, M.R.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Fisher, R.E.; Lowry, D.; Michel, S.E.; Myhre, C.L.; Platt, S.M.; Allen, G.; Bousquet, P.; et al. Very strong atmospheric methane growth in the 4 years 2014–2017: Implications for the Paris Agreement. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2019, 33, 318–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Trends in CO, CO2, CH4, BC, and NOx during the first 2020 COVID-19 lockdown: source insights from the WMO/GAW station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Sustainability 2024, 16, 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.M.; Hodges, J.T.; Rhoderick, G.C.; Lisak, D.; Travis, J.C. Methane-in-air standards measured using a 1.65 μm frequency-stabilized cavity ring-down spectrometer. In Proceedings of the SPIE 6378, Chemical and Biological Sensors for Industrial and Environmental Monitoring II, Boston, MA, USA, 25 October 2006; Volume 6378. [CrossRef]

- Sander, S.P.; Golden, D.M.; Kurylo, M.J.; Moortgat, G.K.; Wine, P.H.; Ravishankara, A.R.; Kolb, C.E.; Molina, M.J.; Finlayson-Pitts, B.J.; Orkin, V.L. Chemical Kinetics and Photochemical Data for Use in Atmospheric Studies Evaluation Number 15; Jet Propulsion Laboratory, National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; De Leo, L.; Bellecci, C. A study of the breeze circulation during summer and fall 2008 in Calabria, Italy. Atmos. Res. 2010, 97, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; Sempreviva, A.M.; De Leo, L.; Avolio, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Bellecci, C. The seasonal characteristics of the breeze circulation at a coastal Mediterranean site in South Italy. Adv. Sci. Res. 2010, 4, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, E.; Federico, S.; Miglietta, M.M.; Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Sempreviva, A.M. Sensitivity analysis of WRF model PBL schemes in simulating boundary-layer variables in southern Italy: An experimental campaign. Atmos. Res. 2017, 192, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Avolio, E.; Sempreviva, A.M. Study of the Vertical Structure of the Coastal Boundary Layer Integrating Surface Measurements and Ground-Based Remote Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Lo Feudo, T.; Torcasio, R.C.; Sempreviva, A.M. Two years of wind-lidar measurements at an Italian Mediterranean Coastal Site. Energy Procedia 2017, 125, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet). Available online: https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en/bathymetry (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Italian Republic. Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers, 9 March 2020. GU Serie Generale n. 62. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Italian Republic. Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers, 18 May 2020. GU Serie Generale n. 127. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/05/18/20A02727/sg (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Calidonna, C.R.; Avolio, E.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Donateo, A.; Lo Feudo, T. Five Years of Dust Episodes at the Southern Italy GAW Regional Coastal Mediterranean Observatory: Multisensors and Modeling Analysis. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Lo Feudo, T.; Avolio, E.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Sinopoli, S.; Cristofanelli, P.; De Pino, M.; D’Amico, F.; Calidonna, C.R. Multiparameter detection of summer open fire emissions: The case study of GAW regional observatory of Lamezia Terme (Southern Italy). Fire 2024, 7, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, N.A.; Venegas, L.E.; Choren, H. Analysis of NO, NO2, O3 and NOx concentrations measured at a green area of Buenos Aires City during wintertime. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 3055–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.C.; Santana, E.R.; Wiegand, F.; Fachel, J. Measurement of surface ozone and its precursors in an urban area in South Brazil. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 2213–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, K.A.; Kreuzer, M.; O’Mara, F.; McAllister, T.A. Nutritional management for enteric methane abatement: a review. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2008, 48, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Henderson, B.; Havlík, P.; Thornton, P.K.; Conant, R.T.; Smith, P.; Wirsenius, S.; Hristov, A.N.; Gerber, P.; Gill, M.; et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation potentials in the livestock sector. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapio, I.; Snelling, T.J.; Strozzi, F.; Wallace, R.J. The ruminal microbiome associated with methane emissions from ruminant livestock. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, G.; Goglio, P.; Vitali, A.; Williams, A.G. Livestock and climate change: Impact of livestock on climate and mitigation strategies. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graven, H.; Keeling, R.F.; Rogelj, J. Changes to carbon isotopes in atmospheric CO2 over the industrial era and into the future. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2020, 34, e2019GB006170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Rosa, L.; Lobell, D.B.; Wang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Doughty, R.; Yao, Y.; Berry, J.A.; Frankenberg, C. The weekly cycle of photosynthesis in Europe reveals the negative impact of particulate pollution on ecosystem productivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, ee2306507120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H. Isotopic standards for carbon and oxygen and correction factors for mass-spectrometric analysis of carbon dioxide. Geoch. Cosm. Act. 1957, 12, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Bowling, D.R.; Ehleringer, J.R. Seasonal cycle of carbon dioxide and its isotopic composition in an urban atmosphere: Anthropogenic and biogenic effects. J. Geophys. Res. – Atmos. 2003, 108, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rella, C.W.; Hoffnagle, J.; He, Y.; Tajima, S. Local- and regional-scale measurements of CH4, δ13CH4, and C2H6 in the Uintah Basin using a mobile stable isotope analyzer. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 4539–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazzeri, G.; Lowry, D.; Fisher, R.E.; France, J.L.; Lanoisellé, M.; Grimmond, C.S.B.; Nisbet, E.G. Evaluating methane inventories by isotopic analysis in the London region. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapenna, E.; Buono, A.; Mauceri, A.; Zaccardo, I.; Cardellicchio, F.; D’Amico, F.; Laurita, T.; Amodio, D.; Colangelo, C.; Di Fiore, G.; et al. ICOS Potenza (Italy) atmospheric station: a new spot for the observation of greenhouse gases in the Mediterranean basin. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Hours | G2401 | T42i | T49i | WXT520 | Prelim. | Proximity | Prox. Meteo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 8760 | 94.73% | 92.73% | 92.14% | 95.9% | 92.12% | 87.87% | 86.99% |

| 2016 | 8784 | 94.95% | 95.91% | 96.17% | 96.34% | 94.17% | 89.9% | 88.22% |

| 2017 | 8760 | 99.57% | 96.39% | 95.93% | 93.8% | 95.65% | 95.27% | 90.67% |

| 2018 | 8760 | 94% | 98.11% | 98.13% | 77.05% | 97.95% | 92.32% | 73.34% |

| 2019 | 8760 | 97.6% | 96.78% | 94.21% | 98.59% | 94.18% | 93.28% | 93.26% |

| 2020 | 8784 | 93.8% | 94.23% | 98.52% | 99.98% | 94% | 89.13% | 89.12% |

| 2021 | 8760 | 97.78% | 87.14% | 91.65% | 99.74% | 78.91% | 77.84% | 77.83% |

| 2022 | 8760 | 83.89% | 69% | 85.22% | 90.11% | 68.97% | 59.15% | 58.04% |

| 2023 | 8760 | 66.76% | 81.86% | 82.12% | 96.3% | 81.82% | 58.61% | 57.35% |

| 788881 | 91.45%2 | 90.24%2 | 92.68%2 | 94.20%2 | 88.64%2 | 82.60%2 | 79.42%2 |

| Year | Prelim. | Standard | Corrected | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOC | N–SRC | R–SRC | BKG | R–SRCcor | BKGcor | R–SRCecor | BKGecor | ||

| 2015 | 92.12% | 48.97% | 30.54% | 10.75% | 9.71% | 2.78% | 17.68% | 6.24% | 13.39% |

| 2016 | 94.17% | 30.75% | 46.78% | 19.1% | 3.32% | 5.06% | 17.38% | 6.66% | 13.75% |

| 2017 | 95.65% | 36.65% | 45.49% | 16.95% | 0.89% | 4.6% | 13.24% | 7.49% | 8.67% |

| 2018 | 97.95% | 42.82% | 47.72% | 9.17% | 0.26% | 3.36% | 6.07% | 3.5% | 5.62% |

| 2019 | 94.18% | 42% | 45.99% | 11.92% | 0.07% | 3.84% | 8.15% | 5% | 5.46% |

| 2020 | 94% | 37.48% | 39.28% | 15.74% | 7.48% | 2.51% | 20.7% | 6.12% | 16.6% |

| 2021 | 78.91% | 34.7% | 40.72% | 19.39% | 4.55% | 4.09% | 19.86% | 9.18% | 13.61% |

| 2022 | 68.97% | 44.75% | 42.75% | 11.51% | 0.95% | 2.33% | 10.14% | 6.27% | 5.16% |

| 2023 | 81.82% | 33.31% | 34.96% | 26.15% | 5.35% | 4.43% | 27.07% | 10.86% | 19.51% |

| 88.64%1 | 39.05%1 | 41.58%1 | 15.63%1 | 3.62%1 | 3.67%1 | 15.59%1 | 6.81%1 | 11.31%1 | |

| Year | Standard – cor | Standard – ecor | cor - ecor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R–SRC | BKG | R–SRC | BKG | R–SRC | BKG | |

| 2015 | -7.97% | +7.97% | -4.51% | +3.68% | +3.46% | -4.29% |

| 2016 | -14.04% | +14.06% | -12.44% | +10.43% | +1.6% | -3.63% |

| 2017 | -12.35% | +12.35% | -9.46% | +7.78% | +2.89% | -4.57% |

| 2018 | -5.81% | +5.81% | -5.67% | +5.36% | +0.14% | -0.45% |

| 2019 | -8.08% | +8.08% | -6.92% | +5.39% | +1.16% | -2.69% |

| 2020 | -13.23% | +13.22% | -9.62% | +9.12% | +3.61% | -4.1% |

| 2021 | -15.3% | +15.31% | -10.21% | +9.06% | +5.09% | -6.25% |

| 2022 | -9.18% | +9.19% | -5.24% | +4.21% | +3.94% | -4.98% |

| 2023 | -21.72% | +21.72% | -15.29% | +14.16% | +6.43% | -7.56% |

| -11,96%1 | +11,97%1 | -8,82%1 | +7,69%1 | +3.15%1 | -4.28%1 | |

| Type | Category | CO (ppb) | CO2 (ppm) | CH4 (ppb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Standard |

LOC | 170.360 ± 68.34 | 449.053 ± 217.56 | 2120.146 ± 187.49 |

| N–SRC | 126.492 ± 29.35 | 416.995 ± 53.22 | 1960.652 ± 67.33 | |

| R–SRC | 108.729 ± 19.29 | 411.788 ± 8.54 | 1940.776 ± 43.06 | |

| BKG | 103.882 ± 21.01 | 409.174 ± 7.85 | 1930.955 ± 42.39 | |

|

Corrected |

R–SRCcor | 110.217 ± 18.67 | 410.817 ± 8.38 | 1935.428 ± 41.15 |

| BKGcor | 107.194 ± 19.94 | 411.395 ± 8.49 | 1939.720 ± 43.53 | |

| R–SRCecor | 108.681 ± 19.57 | 410.874 ± 8.91 | 1939.121 ± 42.55 | |

| BKGecor | 106.957 ± 19.84 | 411.757 ± 8.12 | 1939.934 ± 43.51 |

| Category | Season | CO (ppb) | CO2 (ppm) | CH4 (ppb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LOC |

Fall | 143.803 ± 48.42 | 468.575 ± 395.02 | 2125.003 ± 165.83 |

| Spring | 172.361 ± 54.17 | 442.211 ± 25.07 | 2103.867 ± 182.11 | |

| Summer | 144.902 ± 50.36 | 456.226 ± 26.16 | 2135.630 ± 176.26 | |

| Winter | 217.324 ± 82.18 | 427.627 ± 15.99 | 2115.857 ± 218.65 | |

|

N–SRC |

Fall | 115.183 ± 23.05 | 418.406 ± 104.13 | 1963.134 ± 65.08 |

| Spring | 134.058 ± 25.49 | 418.273 ± 9.64 | 1964.990 ± 66.35 | |

| Summer | 112.362 ± 25.35 | 415.267 ± 13.34 | 1961.091 ± 89.99 | |

| Winter | 141.453 ± 32.36 | 415.512 ± 6.99 | 1952.578 ± 42.87 | |

|

R–SRC |

Fall | 107.461 ± 17.21 | 412.358 ± 7.03 | 1955.852 ± 36.57 |

| Spring | 115.245 ± 16.47 | 414.629 ± 7.44 | 1947.553 ± 41.44 | |

| Summer | 103.248 ± 20.49 | 408.617 ± 8.99 | 1927.197 ± 44.45 | |

| Winter | 116.777 ± 15.99 | 416.625 ± 6.14 | 1954.998 ± 33.49 | |

|

BKG |

Fall | 102.842 ± 10.85 | 409.531 ± 6.78 | 1932.981 ± 35.15 |

| Spring | 116.123 ± 16.96 | 407.519 ± 8.08 | 1912.625 ± 44.08 | |

| Summer | 97.822 ± 22.30 | 409.510 ± 7.78 | 1937.851 ± 40.86 | |

| Winter | 118.304 ± 12.96 | 412.611 ± 9.06 | 1935.331 ± 45.84 | |

|

R–SRCcor |

Fall | 106.273 ± 16.24 | 410.081 ± 7.14 | 1945.307 ± 36.28 |

| Spring | 117.803 ± 16.14 | 414.033 ± 7.71 | 1945.937 ± 42.82 | |

| Summer | 104.525 ± 19.25 | 407.336 ± 8.43 | 1918.533 ± 38.25 | |

| Winter | 117.730 ± 17.04 | 415.991 ± 5.64 | 1951.843 ± 33.81 | |

|

BKGcor |

Fall | 106.782 ± 16.43 | 412.381 ± 6.96 | 1953.807 ± 37.42 |

| Spring | 114.771 ± 16.62 | 413.182 ± 8.11 | 1940.098 ± 44.24 | |

| Summer | 101.455 ± 21.37 | 409.133 ± 8.76 | 1931.988 ± 44.60 | |

| Winter | 116.630 ± 15.31 | 416.383 ± 6.81 | 1953.831 ± 35.54 | |

|

R–SRCecor |

Fall | - | - | - |

| Spring | 115.289 ± 16.81 | 414.143 ± 7.49 | 1949.402 ± 42.19 | |

| Summer | 104.523 ± 20.48 | 408.654 ± 9.46 | 1930.893 ± 43.18 | |

| Winter | - | - | - | |

|

BKGecor |

Fall | - | - | - |

| Spring | 114.889 ± 16.27 | 412.867 ± 8.43 | 1934.997 ± 45.01 | |

| Summer | 99.403 ± 21.52 | 409.309 ± 8.07 | 1930.839 ± 44.99 | |

| Winter | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).