Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Lamezia Terme Station and Employed Methods

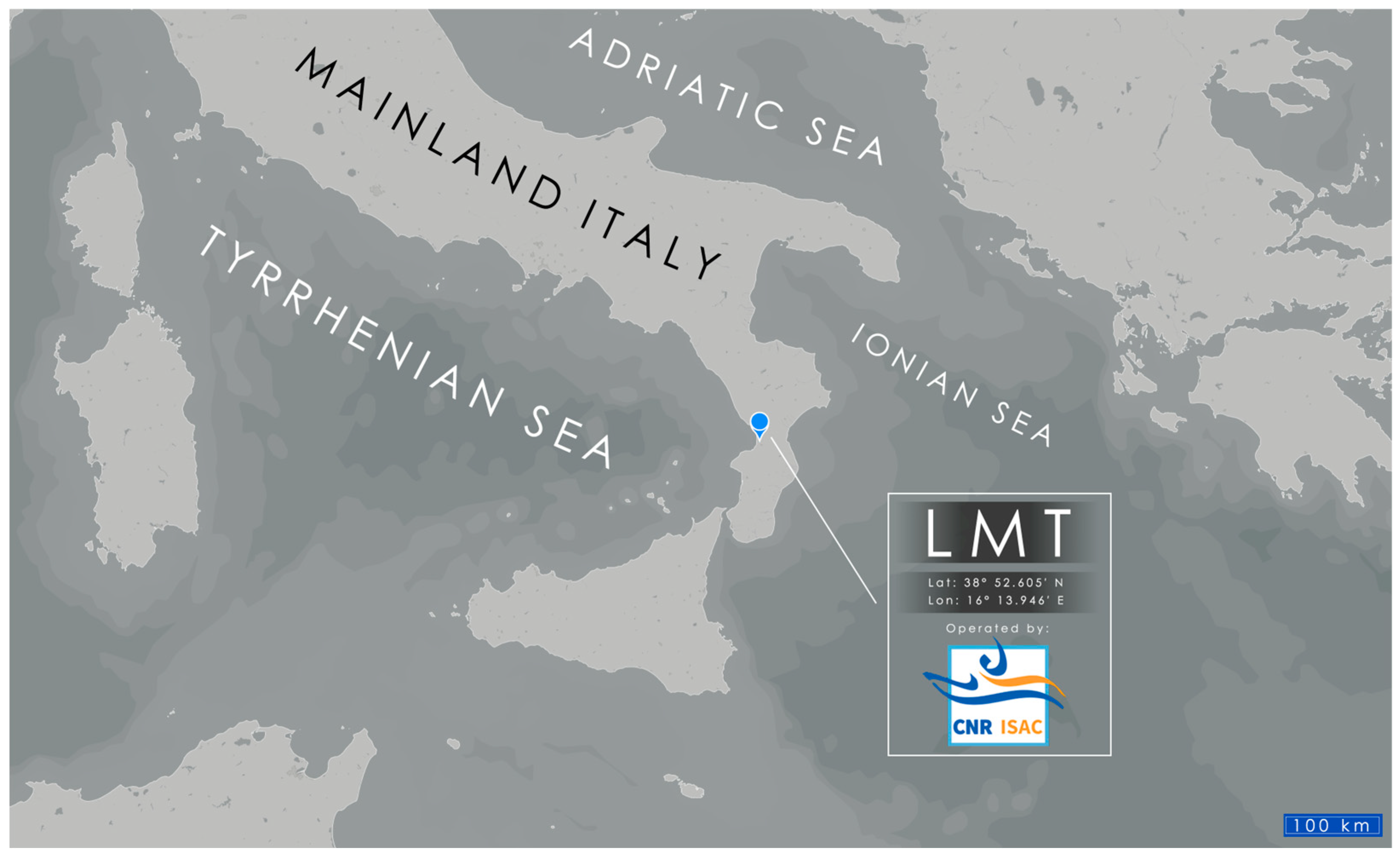

2.1. The LMT WMO/GAW Observation Site in Calabria, Southern Italy

2.2. Surface Measurements, Available Satellite Products, and Data Processing

3. Results

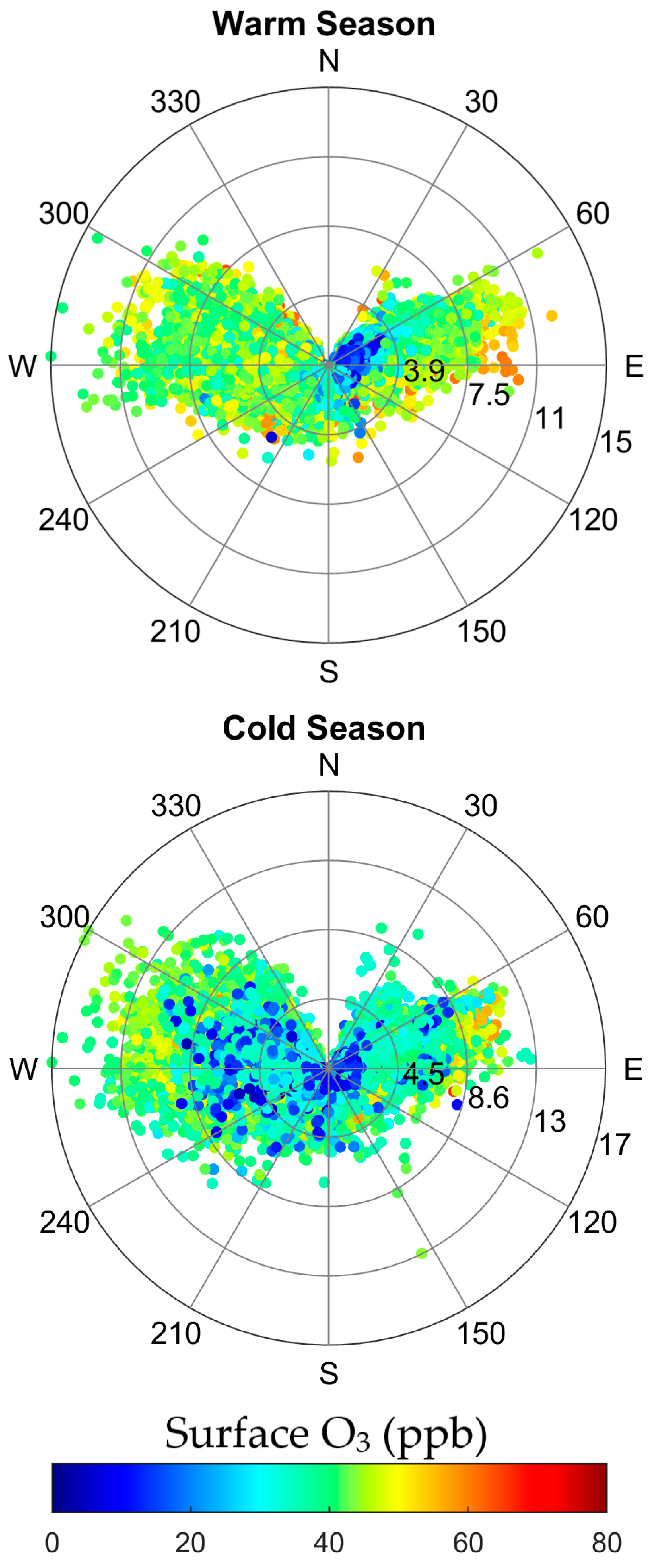

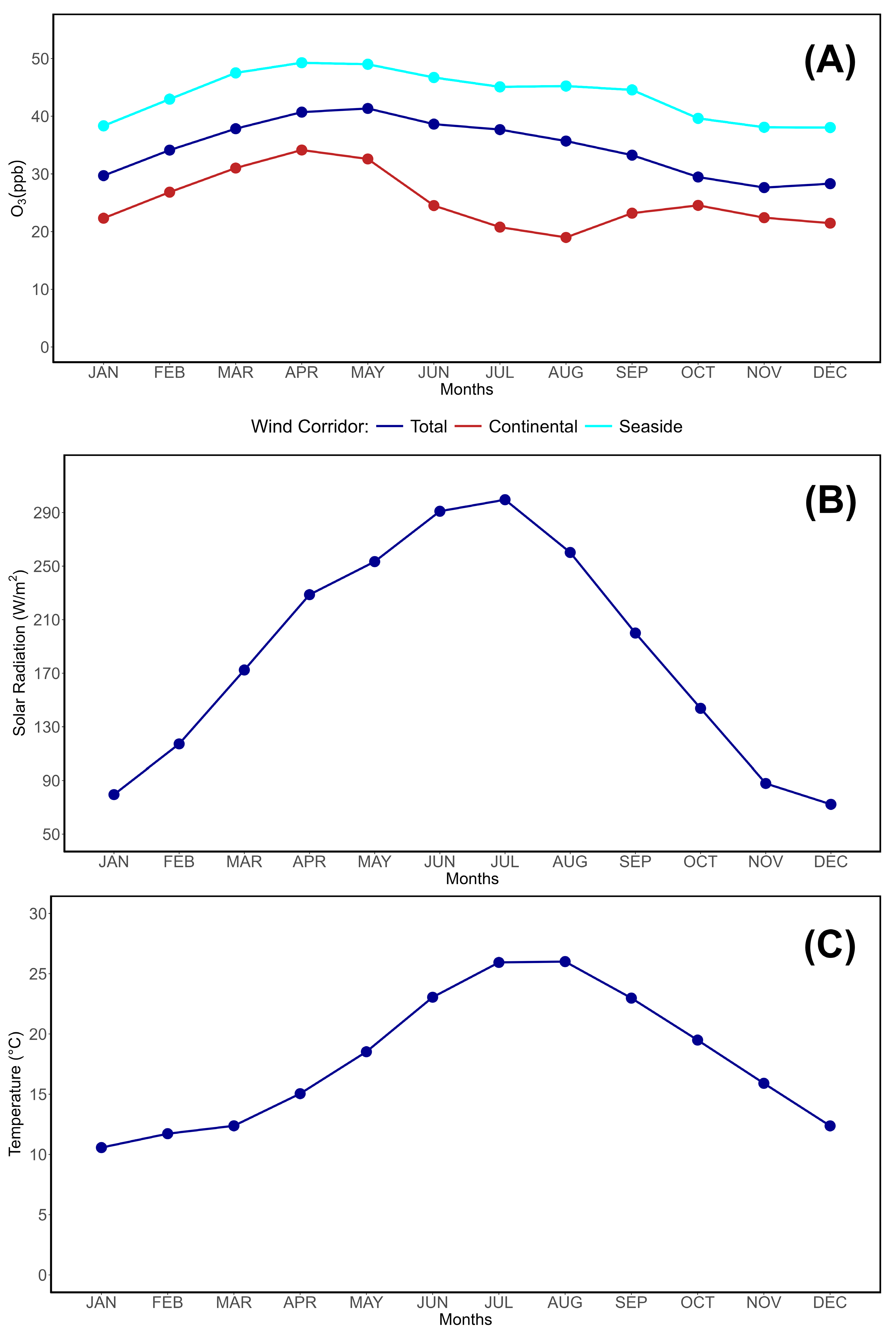

3.1. Seasonal and Monthly Behaviors of Evaluated Parameters Through the Year

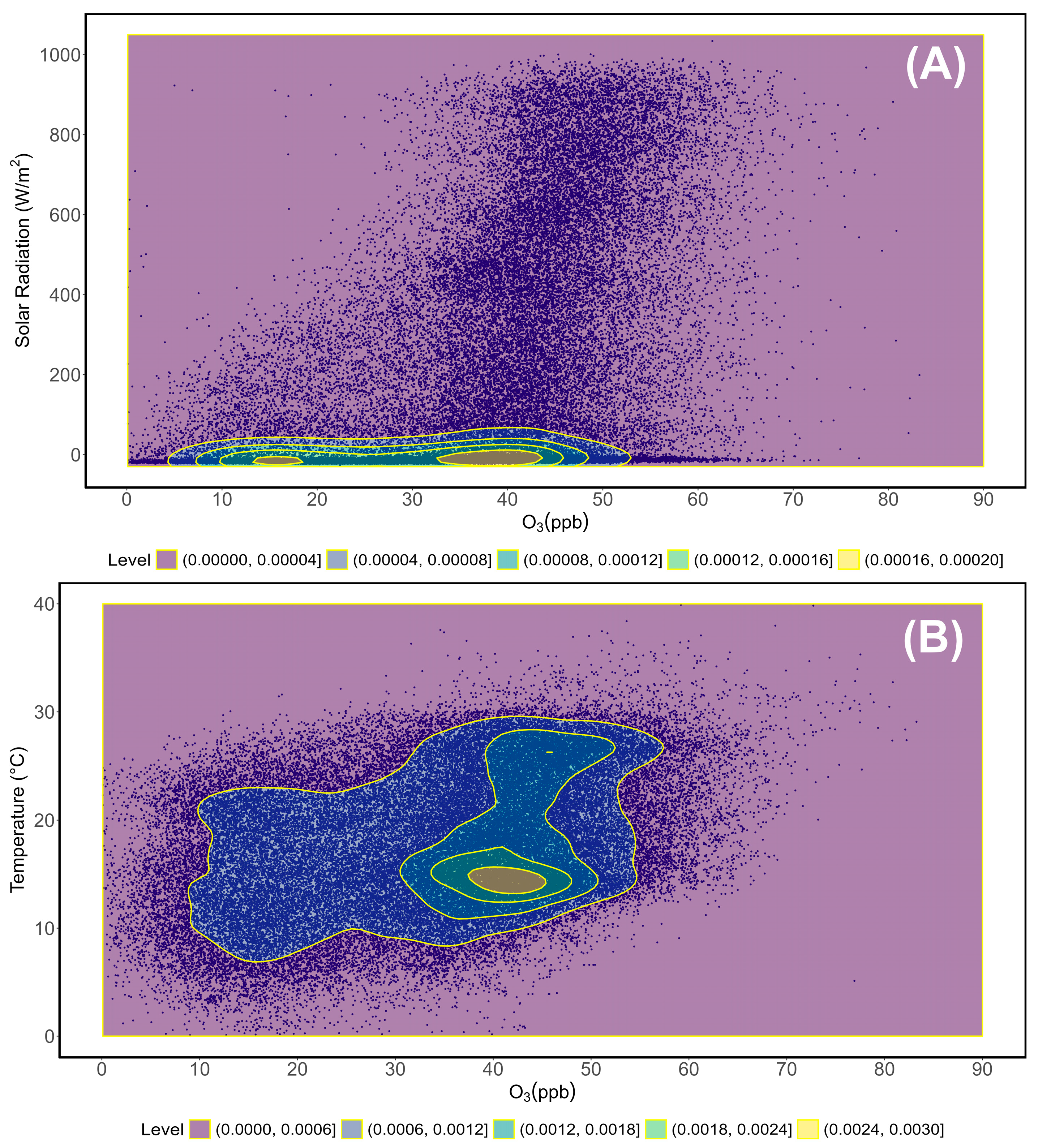

3.2. Correlations Between O3, Solar Radiation, and Temperature at the Site

3.3. Daily Cycle Variability

3.4. Correlations Based on O3/NOx Ratio Proximity Categories

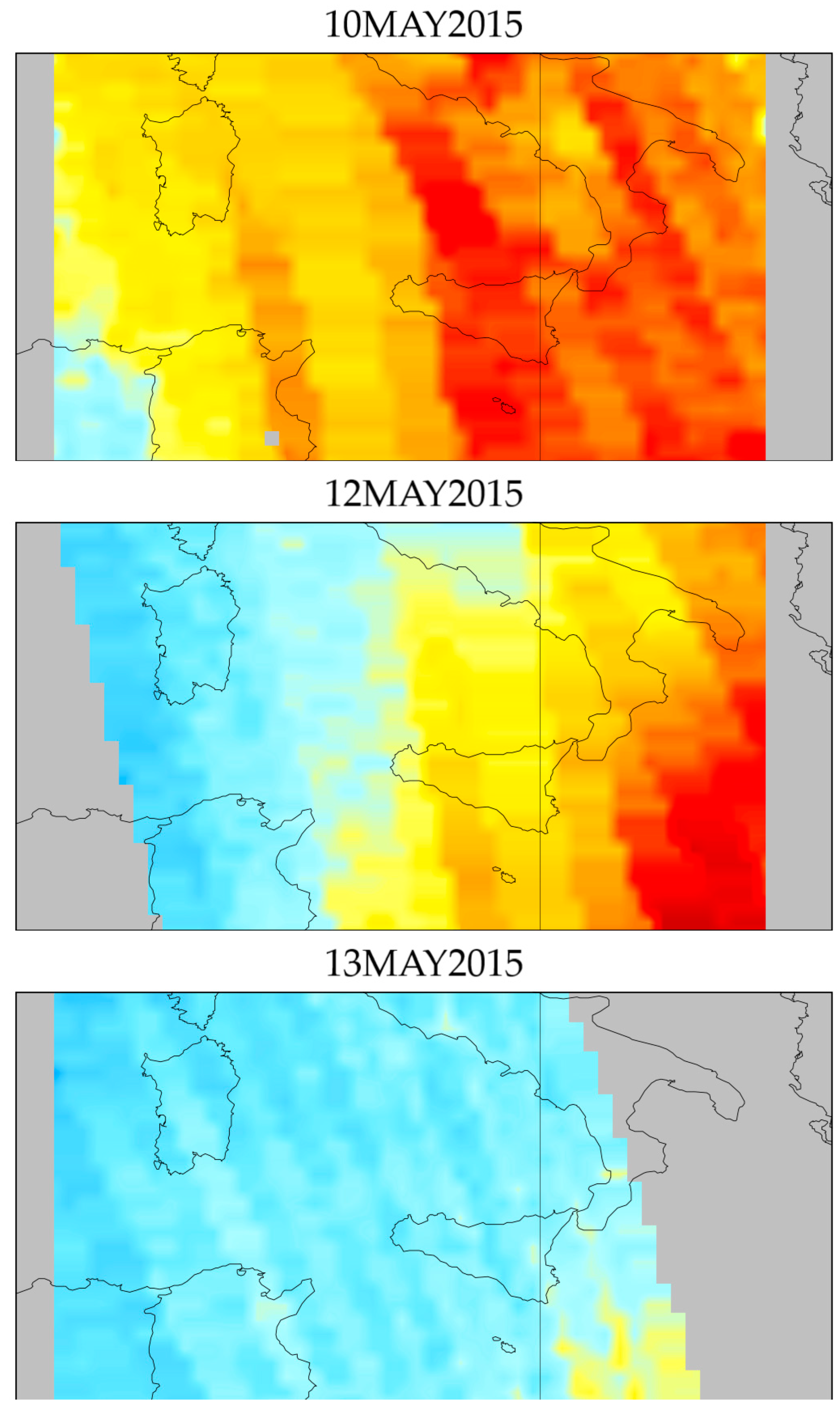

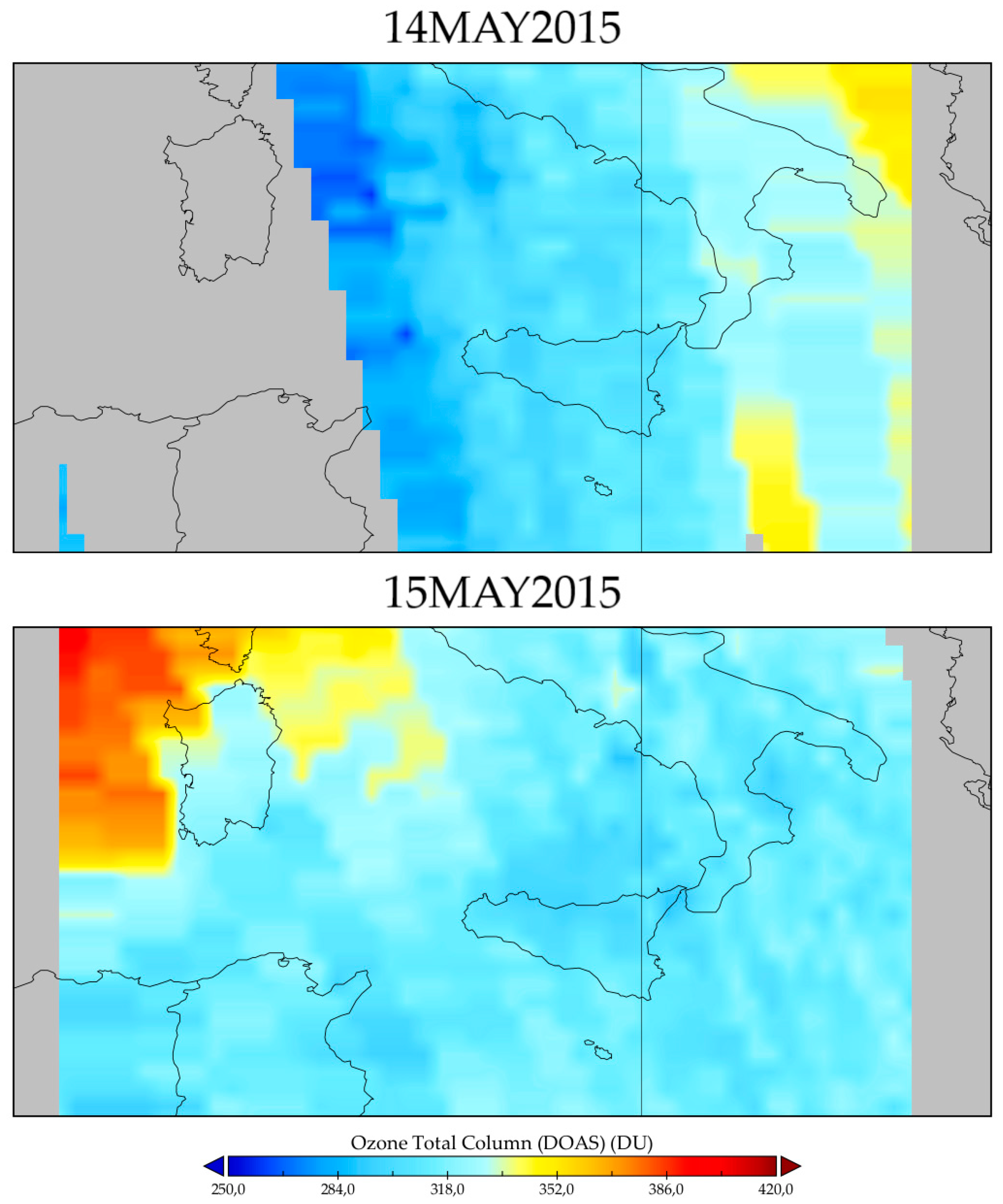

3.5. Case study: 10-15 May 2015

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2016.

- Rodrigues, N.d.N.; Cebrián, J.; Montané, A.; Mendez, S. Intermolecular Interactions and In Vitro Performance of Methyl Anthranilate in Commercial Sunscreen Formulations. AppliedChem 2021, 1, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbein, C.F. Beobachtungen über den bei der Elektrolysation des Wassers und dem Ausströmen der gewöhnlichen Elektricität aus Spitzen sich entwickelnden Geruch. Ann. Phys. Chem. 1840, 50, 616–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbein, C.F. Ueber verschiedene Zustande des Sauerstoffes. Ann. Chem. Pharm. 1854, 89, 257–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, G.H.; Bais, A.F.; Aucamp, P.J.; Klekociuk, A.R.; Liley, J.B.; McKenzie, R.L. Stratospheric ozone, UV radiation, and climate interactions. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 937–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseaux, M.C.; Ballaré, C.L.; Giordano, C.V.; Scopel, A.L.; Zima, A.M.; Szwarcberg-Bracchitta, M.; Searles, P.S.; Caldwell, M.M.; Díaz, S.B. Ozone depletion and UVB radiation: Impact on plant DNA damage in southern South America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999, 96, 15310–15315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, R.P.; Lee, T.K. Adverse effects of ultraviolet radiation: A brief review. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2006, 92, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błazejczyk, B.; Błazejczyk, A. Changes in UV radiation intensity and their possible impact on skin cancer in Poland. Geogr. Pol. 2012, 85, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D. The effects of ozone on plants and people. In: Calvert, J. (Ed.), Chemistry of the Atmosphere: Its Impact on Global Change. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford; 1994.

- Feng, Z.; Sun, J.; Wan, W.; Hu, E.; Calatayud, V. Evidence of widespread ozone-induced visible injury on plants in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.S.; Fnais, M.; Giannadaki, D.; Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 2015, 525, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Wei, Y.; Fang, Z. Ozone Pollution: A Major Health Hazard Worldwide. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, T.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Effects of Ambient O3 on Respiratory Mortality, Especially the Combined Effects of PM2.5 and O3. Toxics 2023, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; He, Z.; Wang, Z. Change in Air Quality during 2014–2021 in Jinan City in China and Its Influencing Factors. Toxics 2023, 11, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, F.M.; Shephard, F.E. Ozone hole and the greenhouse effect. Gas Eng. Manage. 1989, 29, 282–284. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, T. The stratospheric ozone layer-An overview. Environ. Pollut. 1994, 83, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, F. Stratospheric ozone depletion – an overview of the scientific debate. Prog. Phys. Geog. 1995, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canan, P.; Andersen, S.O.; Reichman, N.; Gareau, B. Introduction to the special issue on ozone layer protection and climate change: the extraordinary experience of building the Montreal Protocol, lessons learned, and hopes for future climate change efforts. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2015, 5, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessenich, H.E.; Seppälä, A.; Rodger, C.J. Potential drivers of the recent large Antarctic ozone holes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkov, B.H.; Vitale, V.; Di Carlo, P.; Ochoa, H.A.; Gulisano, A.; Coronato, I.L.; Láska, K.; Kostadinov, I.; Lupi, A.; Mazzola, M.; et al. Approximate Near-Real-Time Assessment of Some Characteristic Parameters of the Spring Ozone Depletion over Antarctica Using Ground-Based Measurements. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimedieu, P.; Krueger, A.J.; Robbins, D.E.; Simon, P.C. Ozone profile intercomparison based on simultaneous observations between 20 and 40 km. Planet. Space Sci. 1983, 31, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasseur, G.; Solomon, S. Aeronomy of the Middle Atmosphere, 2nd ed. D. Reidel, Norwell, Mass, 1986. [CrossRef]

- Cunnold, D.M.; Chu, W.P.; Barnes, R.A.; McCormick, M.P.; Veiga, R.E. Validation of SAGE II ozone measurements. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 1989, 94, 8447-8460. [CrossRef]

- Grewe, V. The origin of ozone. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006, 6, 1495–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D.D.; Law, K.S.; Staehelin, J.; Derwent, R.; Cooper, O.R.; Tanimoto, H.; Volz-Thomas, A.; Gilge, S.; Scheel, H.-E.; Steinbacher, M.; Chan, E. Long-term changes in lower tropospheric baseline ozone concentrations at northern mid-latitudes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 11485–11504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooß, J.U.; Müller, R. Simulation of record Arctic stratospheric ozone depletion in 2020. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2021, 126, e2020JD033339. [CrossRef]

- Holton, J.R.; Haynes, P.H.; McIntyre, M.E.; Douglass, A.R.; Rood, R.B.; Pfister, L. Stratosphere-troposphere exchange. Rev. Geophys. 1995, 33, 403–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauzerall, D.L.; Jacob, D.L.; Fan, S.-M.; Brandshaw, J.D.; Gregory, G.L.; Sachse, G.W.; Blake, D.R. Origin of tropospheric ozone at remote high northern latitudes in summer. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 1996, 101(D2), 4175-4188. [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, G.-J.; Lelieveld, J. Model study of the influence of cross-tropopause O3 transports on tropospheric O3 levels. Tellus Ser. B 1997, 49, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stohl, A.; Bonasoni, P.; Cristofanelli, P.; Collins, W.; Feichter, J.; Frank, A.; Forster, C.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Gäggeler, H.; James, P.; et al. Stratosphere-troposphere exchange: A review, and what we have learned from STACCATO. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2003, 108, 8516. [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Bonasoni, P.; Tositti, L.; Bonafè, U.; Calzolari, F.; Evangelisti, F.; Sandrini, S.; Stohl, A. A 6-year analysis of stratospheric intrusions and their influence on ozone at Mt. Cimone (2165 m above sea level). J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2006, 111, D03306. [CrossRef]

- Knowland, K.E.; Ott, L.E.; Duncan, B.N.; Wargan, K. Stratospheric Intrusion-Influenced Ozone Air Quality Exceedances Investigated in the NASA MERRA-2 Reanalysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 10691–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chameides, W.L.; Davis, D.D.; Rodgers, M.O.; Bradshaw, J.; Sandholm, S.; Sachse, G.; Hill, G.; Gregory, G.; Rasmussen, R. Net ozone photochemical production over the eastern and central North Pacific as inferred from GTE/CITE 1 observations during fall 1983. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 1987, 92(D2), 2131-2152. [CrossRef]

- Butković, V.; Cvitaš, T.; Klasinc, L. Photochemical ozone in the mediterranean. Sci. Total Environ. 1990, 99(1-2), 145-151. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Fan, J.; Tie, X. Impacts of biogenic emissions on photochemical ozone production in Houston, Texas. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2007, 112(D10), 309. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Ma, X.; Lu, K.; Jiang, M.; Zou, Q.; Wang, H.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, Y. Direct evidence of local photochemical production driven ozone episode in Beijing: A case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 148868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhu, B.; Tang, G.; Liu, C.; An, J.; Liu, D.; Zu, J.; Xu, H.; Liao, H.; Zhang, Y. Observational evidence of aerosol radiation modifying photochemical ozone profiles in the lower troposphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49(15), e2022GL099274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Match, A.; Gerber, E.P.; Fueglistaler, S. Beyond self-healing: stabilizing and destabilizing photochemical adjustment of the ozone layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24(18), 10305–10322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lv, X.; Zhong, M.; Zhong, B.; Deng, M.; Jiang, B.; Luo, J.; Caio, J.; Li, X.-B.; Yuan, B.; Shao, M. Intercomparison of measured and modelled photochemical ozone production rates: Suggestion of chemistry hypothesis regarding unmeasured VOCs. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Li, J. Biogenic VOCs emissions and its impact on ozone formation in major cities of China. J. Environ. Sci. Health A 2000, 35, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthawaree, J.; Tajima, Y.; Khunchornyakong, A.; Kato, S.; Sharp, A.; Kajii, Y. Identification of volatile organic compounds in suburban Bangkok, Thailand and their potential for ozone formation. Atmos. Res. 2012, 104–105, 245–254. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Deng, X.J.; Zhu, D.; Gong, D.C.; Wang, H.; Li, F.; Tan, H.B.; Deng, T.; Mai, B.R.; Liu, X.T.; et al. Characteristics of 1 year of observational data of VOCs, NOx and O3 at a suburban site in Guangzhou, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 6625–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; An, J.; Xin, J.; Wu, F.; Wang, J.; Ji, D.; Wang, Y. Source apportionment of VOCs and the contribution to photochemical ozone formation during summer in the typical industrial area in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Atmos. Res. 2016, 176–177, 64–74. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Ho, S.S.H.; Huang, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, L.; Dai, W.; Cao, J.; Lee, S. Source apportionment of VOCs and their impacts on surface ozone in an industry city of Baoji, Northwestern China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Men, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Yue, H.; Cui, S.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, M.; Li, H. Significance of Volatile Organic Compounds to Secondary Pollution Formation and Health Risks Observed during a Summer Campaign in an Industrial Urban Area. Toxics 2024, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, P.S.; Archibald, A.T.; Colette, A.; Cooper, O.; Coyle, M.; Derwent, R.; Fowler, D.; Granier, C.; Law, K.S.; Mills, G.E.; Stevenson, D.S.; Tarasova, O.; Thouret, V.; von Schneidemesser, E.; Sommariva, R.; Wild, O.; Williams, M.L. Tropospheric O3 and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 8889–8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusede, S.E.; Steiner, A.L.; Cohen, R.C. Temperature and recent trends in the chemistry of continental surface O3. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3898–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, E. Fundamentals of Atmospheric Aerosol Chemistry. Akadémiai Kiado, Budapest, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Yin, S.S.; Yu, S.J.; Bai, L.; Wang, X.D.; Lu, X.; Ma, S.L. Characteristics of ozone pollution and the sensitivity to precursors during early summer in central plain. China. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 99, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berntsen, T.K.; Fuglestvedt, J.S.; Joshi, M.M.; Shine, K.P.; Stuber, N.; Ponater, M.; Sausen, R.; Hauglustaine, D.A.; Li, L. Response of climate to regional emissions of ozone precursors: sensitivities and warming potentials. Tellus B 2005, 57, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassomenos, P.; Kotroni, V.; Kallos, G. Analysis of climatological and air quality observations from Greater Athens Area. Atmos. Environ. 1995, 29, 3671–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.M.; Artiñano, B.; Alonso, L.; Navazo, M.; Castro, M. The effect of meso-scale flows on regional and long-range atmospheric transport in the Western Mediterranean area. Atmos. Environ. 1991, 25, 949–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.M.; Salvador, R.; Mantilla, E.; Kallos, G. Photooxidant dynamics in the Mediterranean basin in summer: Results from European research projects. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 1997, 102, 8811-8823. [CrossRef]

- Gangoiti, G.; Millán, M.M.; Salvador, R.; Mantilla, E. Long-range transport and re-circulation of pollutants in the western Mediterranean during the project Regional Cycles of Air Pollution in the West-Central Mediterranean Area. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 6267–6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasopoulos, E.; Kouvarakis, G.; Vrekoussis, M.; Donoussis, C.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Kanakidou, M. Photochemical O3 production in the Eastern Mediterranean. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 3057–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Bonasoni, P. Background O3 in the southern Europe and Mediterranean area: Influence of the transport processes. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallos, G..; Solomos, S.; Kushta, J.; Mitsakou, C.; Spyrou, C.; Bartsotas, N.; Kalogeri, C. Natural and anthropogenic aerosols in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: possible impacts. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 488-489, 389-397. [CrossRef]

- Myriokefalitakis, S.; Daskalakis, N.; Fanourgakis, G.S.; Voulgarakis, A.; Krol, M.C.; Aan de Brugh, J.M.J.; Kanakidou, M. O3 and carbon monoxide budgets over the Eastern Mediterranean. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563–564, 40–52. [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Orio, A.; Pallares, M.; Reina, F.; Dieguez, J.J.; Mantilla, E.; Escudero, M.; Alonso, L.; Gangoiti, G.; Millán, M. On the origin of the highest O3 episodes in Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querol, X.; Gangoiti, G.; Mantilla, E.; Alastuey, A.; Minguillón, M.C.; Amato, F.; Reche, C.; Viana, M.; Moreno, T.; Karanasiou, A.; Rivas, I.; Pérez, N.; Ripoll, A.; Brines, M.; Ealo, M.; Pandolfi, M.; Lee, H.K.; Eun, H.R.; Park, Y.H.; Escudero, M.; Beddows, D.; Harrison, R.M.; Bertrand, A.; Marchand, N.; Lyasota, A.; Codina, B.; Olid, M.; Udina, M.; Jiménez-Esteve, B.; Jiménez-Esteve, B.B.; Alonso, L.; Millán, M.; Ahn, K.H. Phenomenology of high-O3 episodes in NE Spain. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 2817–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Horowitz, L.W.; Payton, R.; Fiore, A.M.; Tonnesen, G. US surface O3 trends and extremes from 1980 to 2014: quantifying the roles of rising Asian emissions, domestic controls, wildfires, and climate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 2943–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.M.; Mantilla, E.; Salvador, R.; Carratalá, A.; Sanz, M.J.; Alonso, L.; Gangoiti, G.; Navazo, M. O3 Cycles in the Western Mediterranean Basin: Interpretation of Monitoring Data in Complex Coastal Terrain. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2000, 39, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, R.M.; Wild, O.; Shindell, D.T.; Zeng, G.; Collins, W.J.; MacKenzie, I.A.; Fiore, A.M.; Stevenson, D.S. Dentener, F.J.; Schultz, M.G.; Hess, P.; Derwent, R.G.; Keating, T.J. Impacts of climate change on surface O3 and intercontinental O3 pollution: A multi-model study. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2013, 118, 3744–3763. [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.H.; Berresheim, S.; Borrmann, P.J.; Crutzen, F.J.; Dentener, H.; Fischer, J.; Feichter, P.J.; Flatau, J.; Heland, R.; Holzinger, R.; Korrmann, M.G. Global air pollution crossroads over the Mediterranean. Science 2002, 298, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henne, S.; Furger, M.; Nyeki, S.; Steinbacher, M.; Neininger, B.; de Wekker, S.F.J.; Dommen, J.; Spichtinger, N.; Stohl, A.; Prévôt, A.S.H. Quantification of topographic venting of boundary layer air to the free troposphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2004, 4, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, B.N.; West, J.J.; Yoshida, Y.; Fiore, A.M.; Ziemke, J.R. The influence of European pollution on ozone in the Near East and northern Africa. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8, 2267–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, P.S.; Granier, C.; Fuzzi, S.; Stohl, A.; Willliams, M.L.; Akimoto, H.; Amann, M.; Baklanov, A.; Baltensperger, U.; Bey, I.; Blake, N.; et al. Atmospheric composition change – global and regional air quality. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 5268–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, M.; Erguler, K.; Ahmady-Birgani, H.; DaifAllah Al-Hmoud, N.; Fears, R.; Gogos, C.; Hobbhahn, N.; Koliou, M.; Kostrikis, L.G.; Lelieveld, J.; Majeed, A.; Paz, S.; Rudich, Y.; Saad-Hussein, A.; Shaheen, M.; Tobias. A.; Christophides, G. Climate change and human health in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: Literature review, research priorities and policy suggestions. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114537. [CrossRef]

- Nastos, P.; Saaroni, H. Living in Mediterranean cities in the context of climate change: A review. Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 44, 3169–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.; Estrela, M.J.; Sanz, M.J.; Mantilla, E.; Martín, M.; Pastor, F.; Salvador, R.; Vallejo, R.; Alonso, L.; Gangoiti, G.; Ilardia, J.L.; Navazo, M.; et al. Climatic feedbacks and desertification: the Mediterranean model. J. Clim. 2005, 18, 684–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallos, G.; Astitha, M.; Katsafados, P.; Spyrou, C. Long-range transport of anthropogenically and naturally produced particulate matter in the Mediterranean and North Atlantic: current state of knowledge. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2007, 46, 1230–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabokas, P.D.; Viras, L.G.; Bartzis, J.G.; Repapis, C.C. Mediterranean rural ozone characteristics around the urban area of Athens. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 5199–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalley, L.; Stone, D.; Heard, D. New insights into the tropospheric oxidation of isoprene: combining field measurements, laboratory studies, chemical modelling and quantum theory. In: McNeill, V.F.; Ariya, P.A. (Eds.), Atmospheric and Aerosol Chemistry Topics in Current Chemistry, 2014. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 55–96. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, L.K.; Saxena, P. High time and mass resolved PTR-TOF-MS measurements of VOCs at an urban site of India during winter: role of anthropogenic, biomass burning, biogenic and photochemical sources. Atmos. Res. 2015, 164, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, L.K.; Yadav, R.; Pal, D. Source identification of VOCs at an urban site of western India: effect of marathon events and anthropogenic emissions. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2016, 121, 2416-2433. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P.; Baldasano, J.M. Contribution of atmospheric processes affecting the dynamics of air pollution in South-Western Europe during a typical summertime photochemical episode. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.M. O3 Dynamics in the Mediterranean Basin: A collection of scientific papers resulting from the MECAPIP, RECAPMA and SECAP Projects, European Commission (DG RTD I.2) Air Pollution Research Report 78, available from CEAM, Valencia, Spain, 2002, 287.

- Pilinis, C.; Kassomenos, P.; Kallos, G. Modeling of photochemical pollution in Athens, Greece. Application of the RAMS-CALGRID modeling system. Atmos. Environ. Part B. 1993, 27, 353–370. [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M.; Luria, M.; Sharf, G.; Vanger, A.; Kallos, G.; Kotroni, V.; Lagouvardos, K.; Varinou, M. Observational evidence of an O3 episode over the Greater Athens Area. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 3969–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varinou, M.; Kallos, G.; Tsiligiridis, G.; Sistla, G. The role of anthropogenic and biogenic emissions on tropospheric O3 formation over Greece. Phys. Chem. Earth, Part C 1999, 24, 507–513. [CrossRef]

- Millán, M.M.; Sanz, M.J. O3 in Mountainous regions and in Southern Europe. In: Ad hoc Working group on O3 Directive and Reduction Strategy Development, (eds.). O3 Position Paper, 145-150, 1999. European Commission, Brussels.

- Mantilla, E.; Millán, M.M.; Sanz, M.J.; Salvador, R.; Carratalá, A. Influence of mesometeorological processes on the evolution of O3 levels registered in the Valencian Community. In: I Technical workshop on O3 pollution in southern Europe, 1997. Valencia.

- Salvador, R.; Millán, M.M.; Calbo, J. Horizontal Grid Size Selection and its influence on Mesoscale Model Simulations. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1999, 38, 1311–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.F.; Mantilla, E.; Millán, M.M. Using measured and modelled indicators to assess O3-NOx-VOC sensitivity in a western Mediterranean coastal environment. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 7167–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astitha, M.; Kallos, G.; Katsafados, P. Air pollution modeling in the Mediterranean Region: Analysis and forecasting of episodes. Atmos. Res. 2008, 89, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabokas, P.D.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Ellul, R.; Kleanthous, S.; Repapis, C.C. An investigation of the meteorological and photochemical factors influencing the background rural and marine surface O3 levels in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 7894–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, D.; Peleg, M.; Alsawair, J.; Soleiman, A.; Matveev, V.; Tas, E.; Gertler, A.; Luria, M. Trans-boundary transport of O3 from the Eastern Mediterranean Coast. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 5595–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doval, M.; Castell, N.; Téllez, L.; Mantilla, E. The use of experimental data and their uncertainty for assessing O3 photochemistry in the Eastern Iberian Peninsula. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castell, N.; Tellez, L.; Mantilla, E. Daily, seasonal and monthly variations in ozone levels recorded at the Turia river basin in Valencia (Eastern Spain). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 3461–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalabokas, P.D.; Cammas, J.P.; Thouret, V.; Volz-Thomas, A.; Boulanger, D.; Repapis, C.C. Examination of the atmospheric conditions associated with high and low summer ozone levels in the lower troposphere over the eastern Mediterranean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 10339–10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, M.; Lozano, A.; Hierro, J.; del Valle, J.; Mantilla, E. Urban influence on increasing O3 concentrations in a characteristic Mediterranean agglomeration. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 99, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabokas, P.D.; Thouret, V.; Cammas, J.P.; Volz-Thomas, A.; Boulanger, D.; Repapis, C.C. The geographical distribution of meteorological parameters associated with high and low summer ozone levels in the lower troposphere and the boundary layer over the Eastern Mediterranean (Cairo case). Tellus B 2015, 67, 27853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querol, X.; Alastuey, A.; Gangoiti, G.; Perez, N.; Lee, H.K.; Eun, H.R.; Park, Y.; Mantilla, E.; Escudero, M.; Titos, G.; Alonso, L.; Temime-Roussel, B.; Marchand, N.; Moreta, J.R.; Revuelta, M.A.; Salvador, P.; Artíñano, B.; García dos Santos, S.; Anguas, M.; Notario, A.; Saiz-Lopez, A.; Harrison, R.M.; Ahn, K.-H. Phenomenology of summer ozone episodes over the Madrid Metropolitan Area, central Spain. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 6511–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, P.; Pitari, G.; Mancini, E.; Gentile, S.; Pichelli, E.; Visconti, G. Evolution of surface ozone in central Italy based on observations and statistical model. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2007, 112, D10316. [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Di Carlo, P.; Aruffo, E.; Apadula, F.; Bencardino, M.; D’Amore, F.; Bonasoni, P.; Putero, D. An Assessment of Stratospheric Intrusions in Italian Mountain Regions Using STEFLUX. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaita, P.R.; Marzuoli, R.; Gerosa, G.A. A regional scale flux-based O3 risk assessment for winter wheat in northern Italy, and effects of different spatio-temporal resolutions. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 333, 121860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Gullì, D.; Lo Feudo, T.; Ammoscato, I.; Avolio, E.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Cyclic and Multi-Year Characterization of Surface Ozone at the WMO/GAW Coastal Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): Implications for Local Environment, Cultural Heritage, and Human Health. Environments 2024, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Lo Feudo, T.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Investigation of Carbon Monoxide, Carbon Dioxide, and Methane Source Variability at the WMO/GAW Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy) Using the Ratio of Ozone to Nitrogen Oxides as a Proximity Indicator. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Busetto, M.; Calzolari, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Dinoi, A.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Sferlazzo, D.; Di Iorio, T.; et al. Investigation of reactive gases and methane variability in the coastal boundary layer of the central Mediterranean basin. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2017, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Benedetto, G.; D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Cristofanelli, P.; De Pino, M.; Gullì, D.; Calidonna, C.R. Methodology for selection near-surface CH4, CO, and CO2 observations reflecting atmospheric background conditions at the WMO/GAW station in Lamezia Terme, Italy. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansi, C.; Muto, F.; Critelli, S.; Iovine, G. Neogene-Quaternary strike-slip tectonics in the central Calabrian Arc (southern Italy). J. Geodyn. 2007, 43(3), 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrotta, C.; Parrino, N.; Pepe, F.; Tansi, C.; Monaco, C. Geomorphological and morphometric analyses of the Catanzaro Trough (Central Calabrian Arc, Southern Italy): Seismotectonic implications. Geosciences 2022, 12(9), 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calidonna, C.R.; Dutta, A.; D’Amico, F.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Lo Feudo, T. Ten-year analysis of Mediterranean coastal winds profiles using remote sensing and in situ measurements. Wind 2025, 5(2), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, W. A former continuation of the Alps. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1976, 87(6), 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandone, P. Structure and evolution of the Calabrian Arc. Earth Evol. Sci. 1982, 3, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, C.; Tortorici, L. Active faulting in the Calabrian arc and eastern Sicily. J. Geodyn. 2000, 29(3-5), 407-424. [CrossRef]

- Martini, I.P.; Sagri, M.; Colella, A. Neogene—Quaternary basins of the inner Apennines and Calabrian arc. In: Anatomy of an Orogen. The Apennines and Adjacent Mediterranean Basins (Eds G.B. Vai and I.P. Martini), 2001, 375–400. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, the Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Brutto, F.; Muto, F.; Loreto, M.F.; De Paola, N.; Tripodi, V.; Critelli, S.; Facchin, L. The Neogene-Quaternary geodynamic evolution of the central Calabrian Arc: A case study from the western Catanzaro Trough basin. J. Geodyn. 2016, 102, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punzo, M.; Cianflone, G.; Cavuoto, G.; De Rosa, R.; Dominici, R.; Gallo, P.; Lirer, F.; Pelosi, N.; Di Fiore, V. Active and passive seismic methods to explore areas of active faulting. The case of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, southern Italy). J. Appl. Geophys. 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrotta, C.; Barberi, G.; Barreca, G.; Brighenti, F.; Carnemolla, F.; De Guidi, G.; Monaco, C.; Pepe, F.; Scarfì, L. Recent Activity and Kinematics of the Bounding Faults of the Catanzaro Trough (Central Calabria, Italy): New Morphotectonic, Geodetic and Seismological Data. Geosciences 2021, 11(10), 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhitano, S.G. The record of tidal cycles in mixed silici–bioclastic deposits: examples from small Plio–Pleistocene peripheral basins of the microtidal Central Mediterranean Sea. Sedimentology 2010, 58(3), 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, D.; Longhitano, S.G.; Muto, F. Sedimentary features of the lower Pleistocene mixed siliciclastic-bioclastic tidal deposits of the Catanzaro Strait (Calabrian Arc, south Italy). Rendiconti Online della Società Geologica Italiana 2012, 21(2), 919-920.

- Longhitano, S.G.; Chiarella, D.; Muto, F. Three-dimensional to two-dimensional cross-strata transition in the lower Pleistocene Catanzaro tidal strait transgressive succession (southern Italy). Sedimentology 2014, 61(7), 2136–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogan, G.E.; Cluff, L.S.; Taylor, C.L. Seismicity and uplift of southern Italy. Tectonophysics 1975, 29(1-4), 323-330. [CrossRef]

- Westaway, R. Quaternary uplift of southern Italy. J. Geophys. Res. – Solid Earth 1993, 98(B12), 21741-21772. [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, T.; Dai Pra, G.; Sylos Labini, S. Geochronology of Pleistocene marine terraces and regional tectonics in Tyrrhenian coast of South Calabria, Italy. Il Quaternario 1994, 7, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, C.; Bianca, M.; Catalano, S.; De Guidi, G.; Gresta, S.; Langher, H.; Tortorici, L. The geological map of the urban area of Catania (Sicily): morphotectonic and seismotectonic implications. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2001, 5, 425–438. [Google Scholar]

- Cucci, L. Raised marine terraces in the Northern Calabrian Arc (Southern Italy): a ~600-kyr-long geological record of regional uplift. Ann. Geophys. 2004, 47, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K.; Antonioli, F.; Purcell, A.; Silenzi, S. Sea-level change along the Italian coast for the past 10,000 yr. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2004, 23(14-15), 1567-1598. [CrossRef]

- Ruello, M.R.; Cinque, A.; Di Donato, V.; Molisso, F.; Terrasi, F.; Russo Ermolli, E. Interplay between sea level rise and tectonics in the Holocene evolution of the St. Eufemia Plain (Calabria, Italy). J. Coast. Conserv. 2017, 21, 903–915. [CrossRef]

- Amodio-Morelli, L.; Bonardi, G.; Colonna, V.; Dietrich, D.; Giunta, G.; Ippolito, F.; Liguori, V.; Lorenzoni, P.; Paglionico, A.; Perrone, V.; Piccarreta, G.; Russo, M.; Scandone, P.; Zanettin-Lorenzoni, E.; Zuppetta, A. L’Arco Calabro-Peloritano nell’orogene Appenninico-Maghrebide. Mem. Soc. Geol. Ital. 1976, 17, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi, G.; De Capoa, P.; Fioretti, B.; Perrone, V. Some remarks on the Calabria-Peloritani arc and its relationship with the southern Apennines. Boll. Geofis. Teor. Appl. 1994, 36, 483–490. [Google Scholar]

- Pirazzoli, P.A.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Saliège, J.F.; Sansò, P. Late Holocene emergence in Calabria, Italy. Mar. Geol. 1997, 141(1-4), 61-70. [CrossRef]

- EUMETSAT – EUMETView Product Viewer. https://view.eumetsat.int/productviewer (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; De Leo, L.; Bellecci, C. A study of the breeze circulation during summer and fall 2008 in Calabria, Italy. Atmos. Res. 2010, 97, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Pasqualoni, L.; Sempreviva, A.M.; De Leo, L.; Avolio, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Bellecci, C. The seasonal characteristics of the breeze circulation at a coastal Mediterranean site in South Italy. Adv. Sci. Res. 2010, 4, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Lo Feudo, T.; Torcasio, R.C.; Sempreviva, A.M. Two years of wind-lidar measurements at an Italian Mediterranean Coastal Site. In European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2017, EGU–Division Energy, Resources & Environment, ERE. Energy Procedia 2017, 125, 214–220. [CrossRef]

- Avolio, E.; Federico, S.; Miglietta, M.M.; Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Sempreviva, A.M. Sensitivity analysis of WRF model PBL schemes in simulating boundary-layer variables in southern Italy: An experimental campaign. Atmos. Res. 2017, 192, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Avolio, E.; Sempreviva, A.M. Study of the Vertical Structure of the Coastal Boundary Layer Integrating Surface Measurements and Ground-Based Remote Sensing. Sensors 2020, 20, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Calidonna, C.R.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Lo Feudo, T. Peplospheric influences on local greenhouse gas and aerosol variability at the Lamezia Terme WMO/GAW regional station in Calabria, Southern Italy: A multiparameter investigation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Integrated Analysis of Methane Cycles and Trends at the WMO/GAW Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calidonna, C.R.; Avolio, E.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Donateo, A.; Lo Feudo, T. Five Years of Dust Episodes at the Southern Italy GAW Regional Coastal Mediterranean Observatory: Multisensors and Modeling Analysis. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K. Deep Learning Techniques for Predicting Wildfires in Calabria Italy Using Environmental Parameters. In: Tekli, J., et al. New Trends in Database and Information Systems. ADBIS 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 2186. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Lo Feudo, T.; Avolio, E.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Sinopoli, S.; Cristofanelli, P.; De Pino, M.; D’Amico, F.; et al. Multiparameter Detection of Summer Open Fire Emissions: The Case Study of GAW Regional Observatory of Lamezia Terme (Southern Italy). Fire 2024, 7, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; De Benedetto, G.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; Calidonna, C.R.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; Lo Feudo, T. Tropospheric and Surface Measurements of Combustion Tracers During the 2021 Mediterranean Wildfire Crisis: Insights from the WMO/GAW Site of Lamezia Terme in Calabria, Southern Italy. Gases 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donateo, A.; Lo Feudo, T.; Marinoni, A.; Dinoi, A.; Avolio, E.; Merico, E.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Bonasoni, P. Characterization of In Situ Aerosol Optical Properties at Three Observatories in the Central Mediterranean. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donateo, A.; Lo Feudo, T.; Marinoni, A.; Calidonna, C.R.; Contini, D.; Bonasoni, P. Long-term observations of aerosol optical properties at three GAW regional sites in the Central Mediterranean. Atmos. Res. 2020, 241, 104976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repubblica Italiana - Italian Republic. Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri - Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers, 9 March 2020. GU Serie Generale n. 62. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/03/09/20A01558/sg (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Repubblica Italiana - Italian Republic. Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri - Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers, 18 May 2020. GU Serie Generale n. 127. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/05/18/20A02727/sg (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- D’Amico, F.; Ammoscato, I.; Gullì, D.; Avolio, E.; Lo Feudo, T.; De Pino, M.; Cristofanelli, P.; Malacaria, L.; Parise, D.; Sinopoli, S.; et al. Trends in CO, CO2, CH4, BC, and NOx during the first 2020 COVID-19 lockdown: Source insights from the WMO/GAW station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Sustainability 2024, 16, 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipona, R.; Kräuchi, A.; Brocard, E. Solar and thermal radiation profiles and radiative forcing measured through the atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L13806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Feudo, T.; Avolio, E.; Gullì, D.; Federico, S.; Calidonna, C.R.; Sempreviva, A. Comparison of Hourly Solar Radiation from a Ground-Based Station, Remote Sensing and Weather Forecast Models at a Coastal Site of South Italy (Lamezia Terme). Energy Procedia 2015, 76, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Burlizzi, P.; Perrone, M.R. Solar eclipse of 20 March 2015 and impacts on irradiance, meteorological parameters, and aerosol properties over southern Italy. Atmos. Res. 2017, 198, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaudi, R.; Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R.; Sempreviva, A.M. Using remote sensing data for integrating different renewable energy sources at coastal site in South Italy. Energy Procedia 2016, 97, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Liang, S.; Yang, K.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Estimating surface solar irradiance from satellites: Past, present, and future perspectives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 233, 111371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibbi, L.; Maselli, F.; Pieri, M. Improved estimation of global solar radiation over rugged terrains by the disaggregation of Satellite Applications Facility on Land Surface Analysis data (LSA SAF). Meteorol. Appl. 2020, 27, e1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, R.; Assi, A.; Fouad, M. Short-term prediction of global solar radiation energy using weather data and machine learning ensembles: A comparative study. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2021, 143, 051003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbois, H. Saint-Drenan, Y.M.; Libois, Q.; Michel, Y.; Cassas, M.; Dubus, L.; Blanc, P. Improvement of satellite-derived surface solar irradiance estimations using spatio-temporal extrapolation with statistical learning. Sol. Energy 2023, 258, 175-193. [CrossRef]

- Herdies, B.R.; Vendrasco, E.P.; Herdies, D.L.; de Oliveira, C.E.L.; de Quadro, M.F.L. The Use of Atmospheric Reanalysis Data for the Estimation of Solar Irradiation Considering the Effect of Atmospheric Aerosols over Brazil. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A.; De Rango, F.; Lo Feudo, T.; Calidonna, C.R. An AI-based Cost-effective Solar Energy Resource Estimation Strategy. 15th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC); Hammamet, Tunisia, 2025, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- EUMETSAT LSA SAF. Available at https://datalsasaf.lsasvcs.ipma.pt (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Carrer, D.; Ceamanos, X.; Moparthy, S.; Vincent, C.; Freitas, S.C.; Trigo, I.F. Satellite Retrieval of Downwelling Shortwave Surface Flux and Diffuse Fraction under All Sky Conditions in the Framework of the LSA SAF Program (Part 1: Methodology). Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrer, D.; Moparthy, S.; Vincent, C.; Ceamanos, X.; Freitas, S.C.; Trigo, I.F. Satellite Retrieval of Downwelling Shortwave Surface Flux and Diffuse Fraction under All Sky Conditions in the Framework of the LSA SAF Program (Part 2: Evaluation). Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troccoli, A.; Morcrette, J.-J. Skill of direct solar radiation predicted by the ECMWF global atmospheric model over Australia. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2014, 53, 2571–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, B.; Meurey, C.; Lajas, D.; Franchistéguy, L.; Carrer, D.; Roujean, J. Near real-time prevision of downwelling shortwave radiation estimates derived from satellite observations. Meteorol. Appl. 2008, 15, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NWCSAF, 2012 NWC-SAF product user manual for Cloud Products, PGE01-02-03 of the SAFNW/MSG, 2012. Available at https://www.nwcsaf.org (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Moreno, A.; Gilabert, M.A.; Camacho, F.; Martínez, B. Validation of daily global solar irradiation images from MSG over Spain. Renew. Energy 2013, 60, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, E.; Leanza, G.; Di Francia, G. Comparative Analysis of Ground-Based Solar Irradiance Measurements and Copernicus Satellite Observations. Energies 2024, 17, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, P.F.; Van Den Oord, G.H.; Dobber, M.R.; Malkki, A.; Visser, H.; De Vries, J.; Stammes, P.; Lundell, J.O.; Saari, H. The ozone monitoring instrument. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, P.F.; Joiner, J.; Tamminen, J.; Veefkind, J.P.; Bhartia, P.K.; Stein Zweers, D.C.; Duncan, B.N.; Streets, D.G.; Eskes, H.; van der A, R.; et al. The Ozone Monitoring Instrument: Overview of 14 years in space. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 5699–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The Proof and Measurement of Association between Two Things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, J.C.; Cliff, N. Empirical size, coverage, and power of confidence intervals for Spearman’s Rho. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1997, 57, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.L.; Well, A.D.; Lorch, R.F., Jr. Research Design and Statistical Analysis, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, D.D.; Allen, D.T.; Bates, T.S.; Estes, M.; Fehsenfeld, F.C.; Feingold, G.; Ferrare, R.; Hardesty, R.M.; Meagher, J.F.; Nielsen-Gammon, J.W.; et al. Overview of the Second Texas Air Quality Study (TexAQS II) and the Gulf of Mexico Atmospheric Composition and Climate Study (GoMACCS). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009, 114, D00F13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.T.; Allan, J.D.; Bower, K.N.; Highwood, E.J.; Liu, D.; McMeeking, G.R.; Northway, M.J.; Williams, P.I.; Krejci, R.; Coe, H. Airborne measurements of the spatial distribution of aerosol chemical composition across Europe and evolution of the organic fraction. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 4065–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, A.M.; Peters, J.W.; Smith, J.P.; Pitts, J.N., Jr. Response of commercial chemiluminescence NO–NO2 analyzers to other nitrogen-containing compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1974, 8, 1118–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, D.; Harrison, J. Response of chemiluminescence NOx analyzers and ultraviolet ozone analyzers to organic air pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1985, 19, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrig, R.; Baumann, R. Comparison of 4 Different Types of Commercially Available Monitors for Nitrogen Oxides with Test Gas Mixtures of NH3, HNO3, PAN and VOC and in Ambient Air. Presented at EMEP Workshop on Measurements of Nitrogen-Containing Compounds, EMEP/CCC Report 1. Les Diablerets, Switzerland, 30 June–3 July 1992.

- Navas, M.J.; Jiménez, A.M.; Galán, G. Air analysis: Determination of nitrogen compounds by chemiluminescence. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 3603–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbacher, M.; Zellweger, C.; Schwarzenbach, B.; Bugmann, S.; Buchmann, B.; Ordóñez, C.; Prévôt, A.S.H.; Hueglin, C. Nitrogen oxide measurements at rural sites in Switzerland: Bias of conventional measurement techniques. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, D11307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Lo Feudo, T.; Gullì, D.; Ammoscato, I.; De Pino, M.; Malacaria, L.; Sinopoli, S.; De Benedetto, G.; Calidonna, C.R. Integrated Surface and Tropospheric Column Analysis of Sulfur Dioxide Variability at the Lamezia Terme WMO/GAW Regional Station in Calabria, Southern Italy. Environments 2025, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friendly, M.; Monette, G.; Fox, J. Elliptical Insights: Understanding Statistical Methods through Elliptical Geometry. Statist. Sci. 2013, 28, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerefos, C.S.; Kourtidis, K.A.; Balis, D.; Bais, A.; Calpini, B. Photochemical activity over the Eastern Mediterranean under variable environmental conditions. Phys. Chem. Earth Part C 2001, 26, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasopoulos, E.; Kazadzis, S.; Vrekoussis, M.; Kouvarakis, G.; Liakakou, E.; Kouremeti, N.; Giannadaki, D.; Kanakidou, M.; Bohn, B.; Mihalopoulos, N. Factors affecting O3 and NO2 photolysis frequencies measured in the eastern Mediterranean during the five-year period 2002-2006. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2012, 117, D22305. [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Güllü, G.; Ünal, A. Assessing the impact of climate change on summertime tropospheric ozone in the Eastern Mediterranean: Insights from meteorological and air quality modeling. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 344, 121036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Hours | Ozone | Radiation | Meteo | OZR | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 8760 | 92.13% | 99.62% | 95.90% | 91.76% | 90.15% |

| 2016 | 8784 | 96.17% | 98.58% | 96.35% | 95.15% | 93.03% |

| 2017 | 8760 | 95.94% | 96.97% | 93.80% | 93.07% | 91.29% |

| 2018 | 8760 | 98.13% | 25.15% | 77.05% | 24.04% | 24.01% |

| 2019 | 8760 | 94.19% | 98.57% | 98.60% | 94.16% | 94.13% |

| 2020 | 8784 | 98.51% | 100% | 99.99% | 98.51% | 98.50% |

| 2021 | 8760 | 91.16% | 99.91% | 99.75% | 91.16% | 90.99% |

| 2022 | 8760 | 85.23% | 99.95% | 90.11% | 85.23% | 81.99% |

| 2023 | 8760 | 81.95% | 85.97% | 96.30% | 68.69% | 67.35% |

| 78,8881 | 92.60%2 | 89.41%2 | 94.20%2 | 82.42%2 | 81.27%2 |

| Parameter | Statistics | Surface O3 (ppb) [All seasons] | |||||

| All Rad. | Pos. Rad. | All NE | All W | Pos. NE | Pos. W | ||

| Solar Radiation (W/m2) | df | 65023 | 31982 | 22806 | 24281 | 6139 | 18493 |

| PCC | 0.502 | 0.452 | 0.445 | 0.195 | 0.483 | 0.174 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.592 | 0.45 | 0.551 | 0.306 | 0.459 | 0.297 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Temperature (°C) | df | 70058 | 31664 | 24949 | 26410 | 6139 | 18493 |

| PCC | 0.362 | 0.268 | 0.256 | 0.096 | 0.273 | 0.071 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.352 | 0.259 | 0.22 | 0.149 | 0.243 | 0.106 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Parameter | Statistics | Surface O3 (ppb) [Warm season] | |||||

| All Rad. | Pos. Rad. | All NE | All W | Pos. NE | Pos. W | ||

| Solar Radiation (W/m2) | df | 27773 | 15556 | 7111 | 12704 | 1684 | 10589 |

| PCC | 0.528 | 0.401 | 0.492 | 0.213 | 0.523 | 0.174 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.605 | 0.357 | 0.45 | 0.218 | 0.489 | 0.173 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Temperature (°C) | df | 29117 | 15408 | 7610 | 13431 | 1684 | 10589 |

| PCC | 0.343 | 0.103 | 0.265 | -0.098 | 0.251 | -0.111 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.316 | 0.041 | 0.169 | -0.115 | 0.19 | -0.132 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Parameter | Statistics | Surface O3 (ppb) [Cold season] | |||||

| All Rad. | Pos. Rad. | All NE | All W | Pos. NE | Pos. W | ||

| Solar Radiation (W/m2) | df | 37248 | 16424 | 15668 | 11547 | 4448 | 7878 |

| PCC | 0.44 | 0.428 | 0.421 | 0.269 | 0.459 | 0.302 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.554 | 0.417 | 0.586 | 0.27 | 0.444 | 0.326 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Temperature (°C) | df | 40939 | 16254 | 17312 | 12948 | 4448 | 7878 |

| PCC | 0.355 | 0.166 | 0.402 | -0.033 | 0.338 | 0.209 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.351 | 0.147 | 0.397 | -0.001 | 0.315 | 0.229 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| O3 by Cat. (ppb) | Statistics | Temp. (°C) |

Radiation (W/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOC | df | 27292 | 27292 |

| PCC | -0.057 | -0.008 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | 0.209 | |

| SR | 0.084 | 0.183 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| N-SRC | df | 29183 | 29183 |

| PCC | -0.108 | 0.107 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.115 | 0.243 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRC | df | 10852 | 10852 |

| PCC | -0.083 | 0.179 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.131 | 0.218 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| BKG | df | 2536 | 2536 |

| PCC | -0.010 | 0.221 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.616 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | -0.130 | 0.210 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRCcor | df | 2584 | 2584 |

| PCC | -0.077 | 0.147 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.153 | 0.224 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| BKGcor | df | 10804 | 10804 |

| PCC | -0.061 | 0.197 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.078 | 0.216 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRCecor | df | 4694 | 4694 |

| PCC | -0.042 | 0.131 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.004 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.026 | 0.167 | |

| SR p-value | 0.070 | < 0.001 | |

| BKGecor | df | 7901 | 7901 |

| PCC | 0.093 | 0.188 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.110 | 0.195 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| O3 by Cat. (ppb) |

Statistics |

All Data | Northeast | West | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. (°C) |

Radiation (W/m2) | Temp. (°C) |

Radiation (W/m2) | Temp. (°C) |

Radiation (W/m2) | ||

| LOC | df | 10191 | 10191 | 5668 | 5668 | 437 | 437 |

| PCC | -0.118 | -0.032 | 0.108 | -0.020 | 0.041 | 0.173 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.135 | 0.397 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.101 | 0.083 | 0.049 | 0.147 | 0.045 | 0.442 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.343 | < 0.001 | |

| N-SRC | df | 11612 | 11612 | 1590 | 1590 | 5562 | 5562 |

| PCC | -0.107 | 0.024 | 0.303 | 0.024 | -0.057 | 0.027 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | 0.009 | < 0.001 | 0.340 | < 0.001 | 0.048 | |

| SR | 0.038 | 0.167 | 0.242 | 0.259 | -0.073 | 0.152 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRC | df | 7084 | 7084 | 133 | 133 | 5398 | 5398 |

| PCC | -0.067 | 0.006 | 0.655 | 0.313 | -0.075 | 0.085 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | 0.590 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | -0.078 | 0.072 | 0.654 | 0.357 | -0.087 | 0.119 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| BKG | df | 1950 | 1950 | 22 | 22 | 1628 | 1628 |

| PCC | -0.011 | 0.089 | 0.344 | -0.102 | -0.329 | 0.154 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.629 | < 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.635 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | -0.354 | 0.100 | 0.608 | 0.120 | -0.334 | 0.159 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.575 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRCcor | df | 1617 | 1617 | 41 | 41 | 1192 | 1192 |

| PCC | -0.059 | 0.005 | 0.744 | 0.340 | -0.031 | 0.068 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.018 | 0.830 | < 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.277 | 0.02 | |

| SR | -0.022 | 0.082 | 0.769 | 0.479 | -0.06 | 0.12 | |

| SR p-value | 0.381 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.038 | < 0.001 | |

| BKGcor | df | 7417 | 7417 | 114 | 114 | 5834 | 5834 |

| PCC | -0.049 | 0.028 | 0.587 | 0.237 | -0.161 | 0.106 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | 0.015 | < 0.001 | 0.010 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.166 | 0.075 | 0.610 | 0.200 | -0.17 | 0.129 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.031 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRCecor | df | 3515 | 3515 | 41 | 41 | 3089 | 3089 |

| PCC | -0.049 | -0.004 | 0.744 | 0.340 | -0.131 | 0.037 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.004 | 0.793 | < 0.001 | 0.026 | < 0.001 | 0.041 | |

| SR | -0.121 | 0.047 | 0.769 | 0.479 | -0.151 | 0.064 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | 0.005 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| BKGecor | df | 4876 | 4876 | 114 | 114 | 3294 | 3294 |

| PCC | -0.062 | 0.038 | 0.587 | 0.237 | -0.182 | 0.15 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | 0.010 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | -0.179 | 0.100 | 0.610 | 0.200 | -0.192 | 0.181 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.031 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| O3 by Cat. (ppb) |

Statistics |

All Data | Northeast | West | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. (°C) |

Radiation (W/m2) | Temp. (°C) |

Radiation (W/m2) | Temp. (°C) |

Radiation (W/m2) | ||

| LOC | df | 17099 | 17099 | 10892 | 10892 | 14238 | 14238 |

| PCC | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.234 | -0.016 | 0.027 | 0.077 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.004 | 0.439 | < 0.001 | 0.088 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.189 | 0.244 | 0.195 | 0.315 | -0.005 | 0.158 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.555 | < 0.001 | |

| N-SRC | df | 17569 | 17569 | 5272 | 5272 | 7793 | 7793 |

| PCC | -0.015 | 0.181 | 0.163 | 0.124 | -0.11 | 0.167 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.051 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.034 | 0.292 | 0.123 | 0.331 | -0.11 | 0.231 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRC | df | 3766 | 3766 | 522 | 522 | 2564 | 2564 |

| PCC | -0.020 | 0.361 | 0.284 | 0.586 | 0.113 | 0.215 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.220 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.116 | 0.359 | 0.317 | 0.577 | 0.104 | 0.227 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| BKG | df | 584 | 584 | 83 | 83 | 539 | 539 |

| PCC | 0.007 | 0.556 | 0.635 | 0.467 | 0.190 | 0.563 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.866 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.207 | 0.508 | 0.693 | 0.481 | 0.211 | 0.527 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRCcor | df | 965 | 965 | 110 | 110 | 699 | 699 |

| PCC | 0.013 | 0.299 | 0.212 | 0.573 | 0.136 | 0.219 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.695 | < 0.001 | 0.025 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.131 | 0.315 | 0.213 | 0.595 | 0.131 | 0.252 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.024 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| BKGcor | df | 3385 | 3385 | 495 | 495 | 2256 | 2256 |

| PCC | -0.022 | 0.409 | 0.337 | 0.571 | 0.126 | 0.262 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.194 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.143 | 0.398 | 0.406 | 0.561 | 0.131 | 0.257 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| R-SRCecor | df | 1177 | 1177 | 110 | 110 | 911 | 911 |

| PCC | 0.033 | 0.371 | 0.212 | 0.573 | 0.147 | 0.306 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.255 | < 0.001 | 0.025 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.152 | 0.404 | 0.213 | 0.595 | 0.147 | 0.353 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.024 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| BKGecor | df | 3023 | 3023 | 495 | 495 | 1894 | 1894 |

| PCC | -0.044 | 0.353 | 0.337 | 0.571 | 0.138 | 0.145 | |

| PCC p-value | 0.015 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.138 | 0.325 | 0.406 | 0.561 | 0.138 | 0.107 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Category | Average surface O3 (ppb) ± 1σ | ||

| All data | Warm season | Cold season | |

| LOC | 21.35 ± 10.11 | 21.28 ± 9.42 | 21.39 ± 10.50 |

| N-SRC | 42.08 ± 8.24 | 44.05 ± 8.76 | 40.77 ± 7.59 |

| R-SRC | 46.42 ± 7.08 | 47.81 ± 7.13 | 43.80 ± 6.20 |

| BKG | 47.73 ± 8.58 | 48.52 ± 8.84 | 45.07 ± 7.06 |

| R-SRCcor | 46.74 ± 7.13 | 48.17 ± 7.34 | 44.35 ± 6.05 |

| BKGcor | 46.64 ± 7.47 | 47.91 ± 7.58 | 43.86 ± 6.41 |

| R-SRCecor | 47.27 ± 7.22 | 47.90 ± 7.34 | 45.42 ± 6.53 |

| BKGecor | 46.04 ± 7.49 | 47.87 ± 7.72 | 43.09 ± 6.03 |

|

Statistics |

CS parameters | |||||

| LMT SAT (W/m2) | LMT OBS (W/m2) | Temp. (°C) |

Stromboli (W/m2) | Ionian (W/m2) | ||

| Surface O3 (ppb) | df | 86 | 142 | 142 | 87 | 87 |

| PCC | 0.456 | 0.51 | 0.617 | 0.463 | 0.464 | |

| PCC p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| SR | 0.442 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.437 | 0.412 | |

| SR p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).