1. Introduction

Scintillators coupled to fast detectors are widely used in several fields and applications, such as high-energy physics [

1], medical imaging [

2], dosimetry [

3], and archaeology [

4]. Over the last seventy years various researchers have studied the possibility of using this type of detection system in time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ToF-MS, see for instance [

5,

6,

7,

8]), and scintillators are now finding their way into the ion detectors of state-of-the-art commercial time-of-flight instruments [

9,

10,

11]. In most of these detectors the ions hit a microchannel plate (MCP) detector or a conversion dynode, generating secondary electrons which are accelerated towards the scintillator. This way more scintillation photons are produced and the detection efficiency increases.

There have been a small number of investigations into the possibility of removing the MCPs and directly detecting the ions using a scintillator coupled to a photodetector [

6,

8,

12]. This approach is widely used in the high-energy physics/astrophysics community (see for instance [

13,

14,

15]), but until recently has not been suitable for the detection of low-energy ions due to the fact that impact of a low-energy ion with a scintillator generally generates too few photons to be detected [

16,

17,

18]. The advent of faster, brighter scintillators [

19,

20,

21], coupled with a new generation of photodetectors capable of single-photon detection [

22,

23], opens up new opportunities for the development of low-energy ion detectors based on this concept. Eliminating the MCPs from an ion detector has a number of advantages. While MCPs have outstanding time resolution, which is crucial in ToF-MS systems, they are expensive, fragile, suffer from ageing, and have strict high vacuum requirements. They are also prone to saturation, with a maximum output current that limits the achievable data acquisition rate [

24,

25]. As noted above, eliminating the MCPs drastically reduces the number of photons available for detection, in principle compromising the detection efficiency, particularly for high

ions. However, there are ways to overcome this issue. For instance, Dubois and coworkers [

6] were able to increase the detection efficiency for 70 kDa ions by placing a copper grid immediately before the scintillator as a secondary ion converter. Later [

7], the

range was increased to 90 kDa using a more complex method in which the scintillator was coated with a thin layer of aluminium (

Å) and the ion beam was directed towards it to generate secondary cations. These cations were then guided to a washer-shaped aluminium component to produce secondary electrons, which were subsequently accelerated to the scintillator.

Most scintillation detectors employed in ToF-MS applications are equipped with a photomultiplier tube (PMT) as a photodetector. Wilman

et al [

8] investigated replacing this with a silicon photomultiplier (SiPM). SiPMs offer several advantages with respect to PMTs, including a higher photodetection efficiency (PDE), a greater degree of compactness and robustness, insensitivity to magnetic fields, and no requirement for a high operation voltage. A single-photon time resolution (SPTR) below 100 ps FWHM can be obtained with commercial SiPMs [

26], and the time resolution can be as good as a few tens of ps for higher intensity signals. In addition, SiPMs can easily be grouped into compact arrays to achieve a few tens of channels per cm

2, offering substantial possibilities for increasing the ion detection throughput by orders of magnitude via parallelisation of the detection system.

SiPM arrays are particularly well suited for use in imaging mass spectrometry and multi-mass imaging experiments, such as velocity-map and spatial-map imaging mass spectrometry (VMImMS) [

27,

28]. These techniques require fast position-sensitive detectors capable of operating at high acquisition rates to achieve 3D-imaging (

) of the velocity distributions of the fragment ions. A camera based on SiPM technology offers an increase in speed of an order of magnitude or more relative to the fastest existing optical cameras for time-resolved particle imaging [

29,

30,

31]. One of the main challenges associated with building such a camera is the requirement for signal acquisition and digitization of several tens to hundreds of closely-packed channels. Unsurprisingly, the cost and complexity of the detector increases with the number of readout channels.

In the following, we report results from the first ToF-MS experiments performed with an array of 16 SiPMs coupled to a fast scintillator to directly detect the ions without MCPs. The SiPMs were read out using FastIC, an 8-channel application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) developed for fast-timing applications and easily scalable for read-out of hundreds of pixels [

32,

33,

34,

35].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The FastIC ToF-MS Prototype

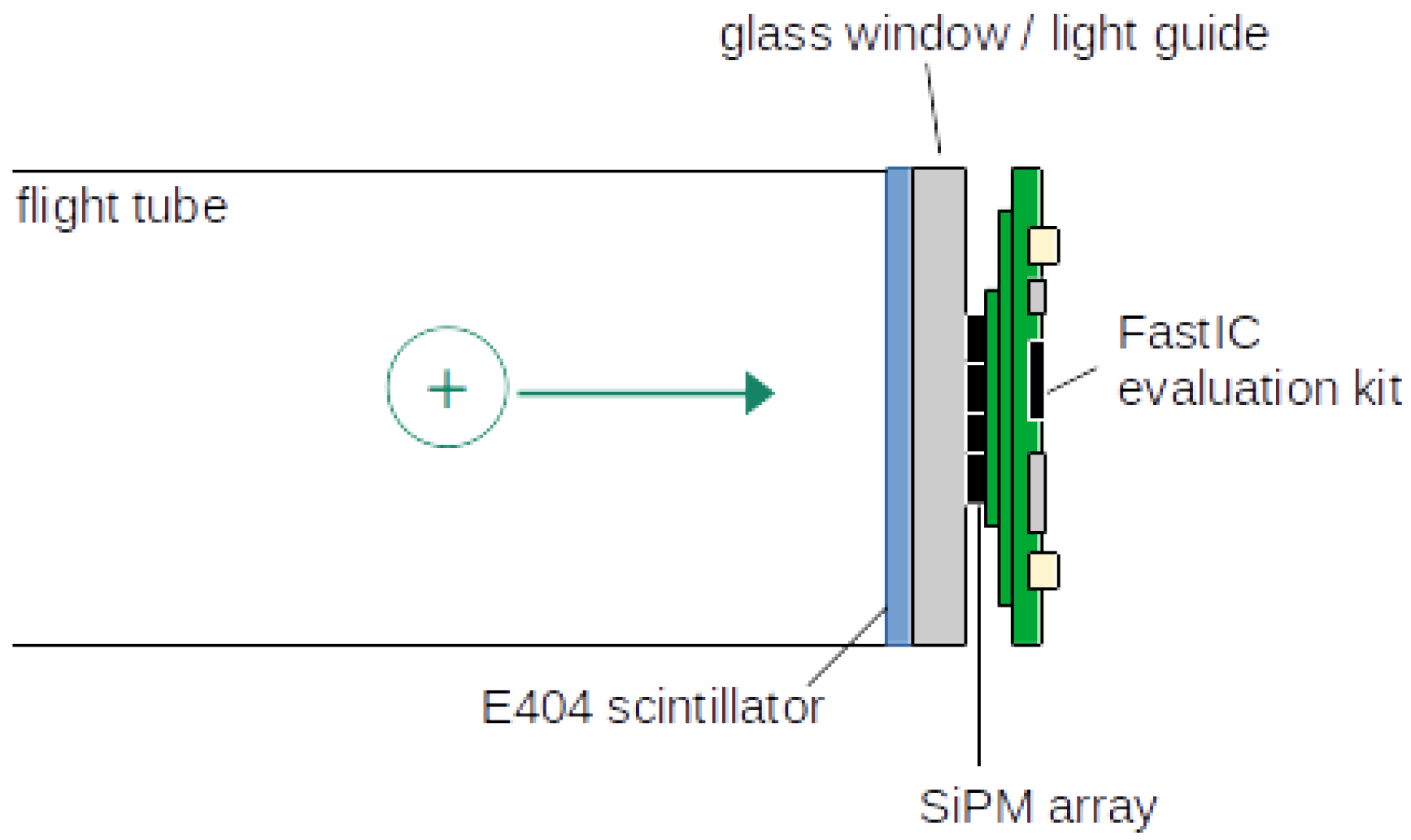

The detector we have developed is shown schematically in

Figure 1, and consists of an Exalite 404 (E404) scintillator (see [

19] and [

12] for details) coupled to the SiPM sensor array and readout system. The E404 scintillator is coated by vacuum sublimation [

12,

19] onto the vacuum side of an indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated 40 mm diameter fibre-optic plate (Photonis) that forms the vacuum interface. The scintillator emission peaks at ∼412 nm, with a rise time of ∼1.1 ns and a decay time of ∼ 1.5 ns [

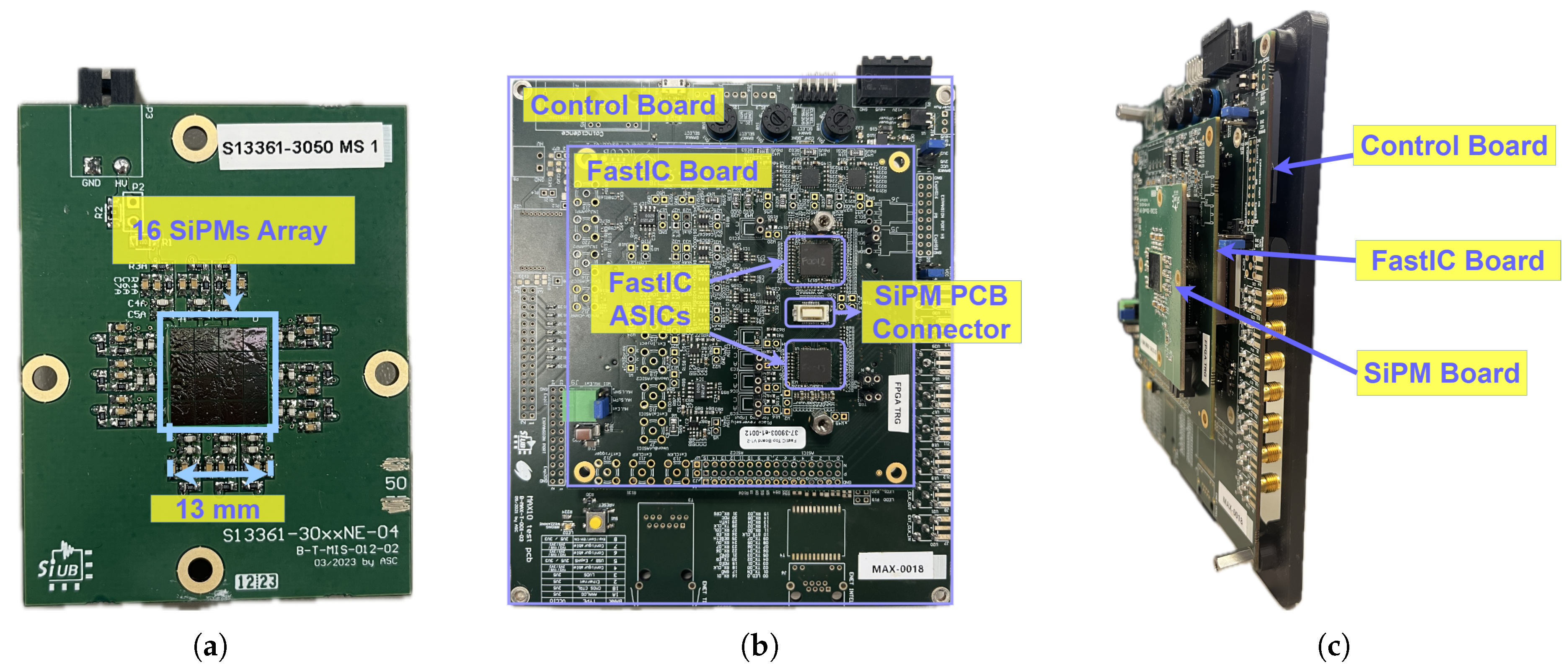

30]. Incoming ions strike the scintillator with energies of a few keV, typically generating a few scintillation photons per ion. The array of 16 SiPMs (Hamamatsu S13361-3050-NE04 - see

Figure 2) is mounted outside the vacuum on the output face of the fibre-optic plate and is optically coupled to the plate using BC-630 silicone optical grease. Signals from the SiPM array are digitised and read out using a FastIC evaluation kit. Each SiPM has an area of

mm

2 and is protected with an epoxy resin (refraction index

1.55). The SiPMs have a breakdown voltage of ∼52 V at room temperature. They achieve a peak PDE of ∼55% at 450 nm, when operated at 7 V above breakdown. The total area occupied by the array, including dead spaces between SiPMs, is 13×13 mm

2. Each SiPM has a fill factor of 74%, resulting in a total sensitive area of the array employed of ∼106.6 mm

2, which represents ∼8% of the total scintillation area.

The FastIC evaluation kit comprises two printed circuit boards (PCBs): one that houses two FastIC ASICs; and another equipped with a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) (refer to

Figure 2). FastIC is an 8-channel ASIC designed to process signals from high-gain detectors, includings SiPMs, PMTs, and MCPs, specifically for fast-timing applications. The ASIC processes incoming pulses, allowing for the extraction of crucial information regarding their arrival time and amplitude. The arrival time information is obtained using a threshold comparator. The level of the comparator can be modified by the user. More details on the ASIC can be found in [

32,

33,

34].

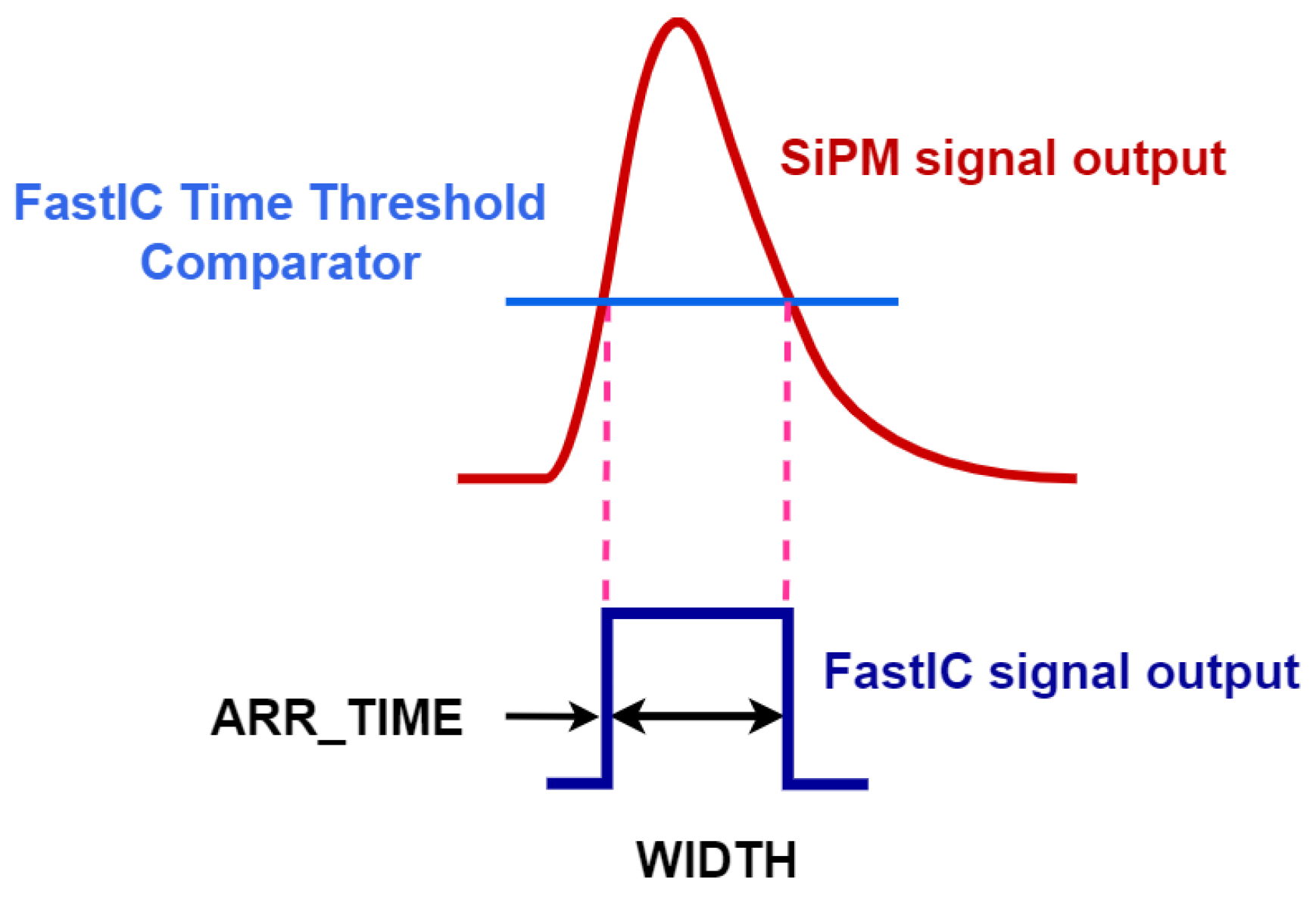

The readout system has two operation modes: `standard’ and `high-rate’. In the standard mode FastIC outputs two consecutive binary pulses: the first one encodes in its rise time the arrival time of the input signal, while the width of the second one is proportional to the amplitude of the input signal. The main drawback of this mode is that it has a dead time of 500 ns per detector channel. In the high-rate mode, FastIC outputs a single binary pulse that still encodes in its rise time the arrival time of the input signal while the width of this binary pulse is related, non-linearly, to the amplitude of the input signal (see

Figure 3). This mode, which is the one employed in the experiments reported here, results in a channel dead time as low as ∼20 ns and, as will be shown in

Section 3, can still provide information about the intensity of the incoming signals for fluxes of a few photoelectrons (phes).

The binary signals generated by FastIC can easily be digitized by a multi-channel time-to-digital converter (TDC), such as that implemented in the FPGA of the FastIC evaluation kit. In the present implementation, the TDC was used to process 17 signals, 16 arising from the two FastIC ASICs and an additional channel used to record the trigger signal. For each FastIC signal the TDC outputs two values, which we labeled ARR_TIME ( the arrival time of the recorded signal, see

Figure 3) and WIDTH (related to the amplitude of the signal).

2.2. Characterization of the Detector

Initially, the SiPM/FastIC detection and readout system was characterised using pulses from a picosecond pulsed laser, before being coupled with the fast scintillator and incorporated into a custom-built velocity-map imaging mass spectrometer for ToF-MS measurements. These two steps are described separately in the following.

2.2.1. Optical Characterization of the SiPM Array

One of the most important design specifications for a ToF-MS detector is its intrinsic time resolution. In our case, the overall time resolution of the detector comprises contributions from the time responses of the scintillator, the photodetector, and the readout electronics. The time response of the E404 scintillator has been characterised previously [

30]. In the present work we have characterized the single-photon time resolution (SPTR) of the SiPM array readout using the FastIC evaluation kit. These measurements were performed by illuminating the SiPM array directly with pulses of light from a picosecond pulsed laser (Picosecond laser diode system `PiL040X’ from Advanced Laser Diode Systems A.L.S. GmbH). The laser generates ∼ 405 nm (∼1 nm full width half maximum, FWHM), ∼28 ps pulses. The laser output was coupled via a single-mode optical fibre to a collimator, before entering a liquid-crystal beam attenuator (Thorlabs LCC1620). This way we could achieve a photon flux of a few photons at the front of the SiPM array.

The SiPMs were operated at a bias voltage of 59 V. In these measurements we set the FastIC discriminator threshold below the single-phe level. During the analysis we applied cuts in the WIDTH values to select single-phe events. From the resulting subsample, we extracted the ARR_TIME values and built a distribution that we could fit to an exponentially modified Gaussian (EMG) function, which is standard in SPTR studies with SiPMs [

26]. Typically, the SPTR is defined as the FWHM of this fitted distribution, which includes contributions from the laser, the SiPM, and the electronic readout. To obtain the intrinsic SPTR of the photonic detector, the contribution of the laser must be deconvoluted.

2.2.2. Characterization of the Ion Detector Performance within a ToF-MS Experiment

The complete detector described in

Section 2.1 was mounted within a custom-designed multi-mass velocity-map imaging instrument located at the University of Oxford. The instrument is essentially a time-of-flight mass spectrometer which is designed to record images of the scattering or velocity distributions of each ion in addition to their time-of-flight [

36,

37]. The specific details of the instrument have been described in detail previously [

38,

39,

40,

41], and will only be summarised fairly briefly in the following.

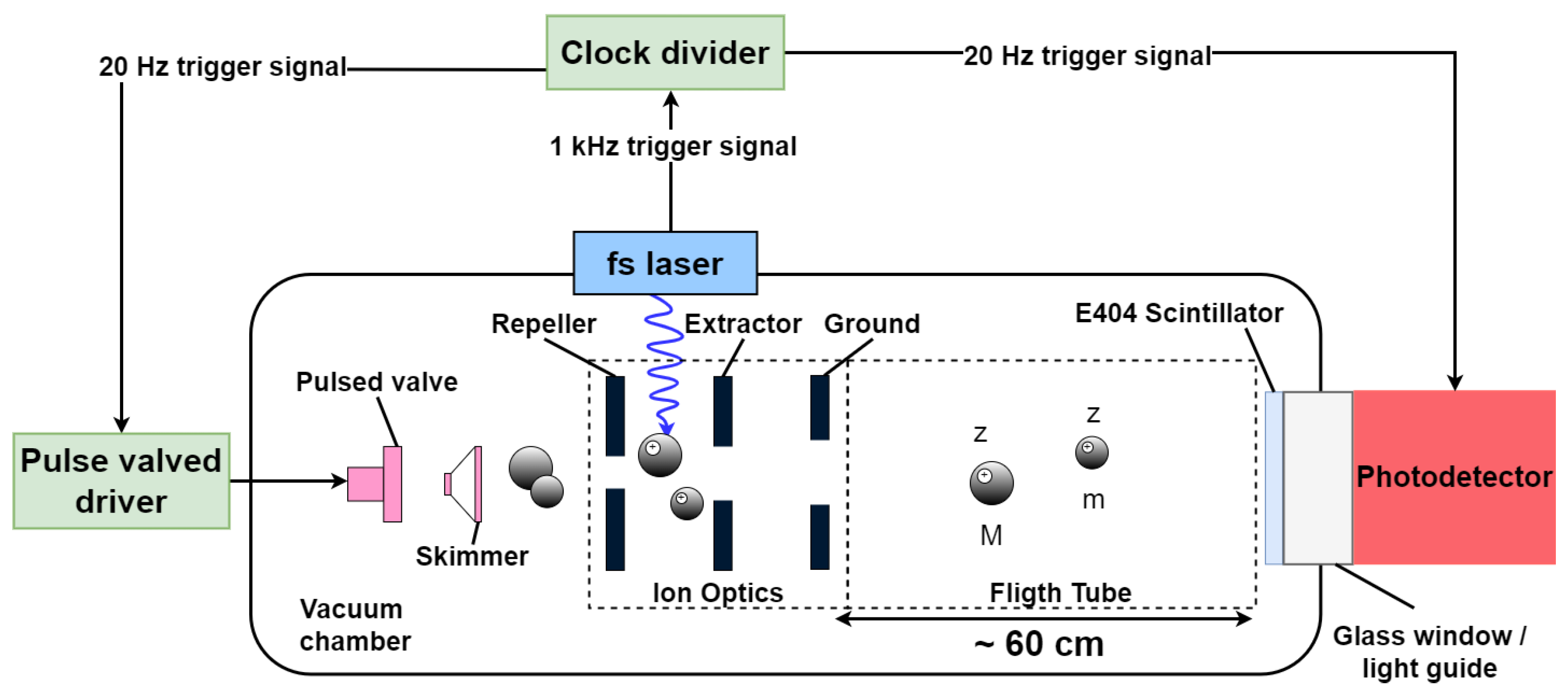

The ion detector was used to record ion signals arising from the dissociative photoionisation of CF

3I and C

3H

6. Both molecules were prepared in a seeded supersonic molecular beam using helium as the buffer gas. The supersonic expansion was generated using a Parker Hannifin Series 9 pulsed solenoid valve operating at a frequency of 20 Hz, and passed through a skimmer before entering the interaction region through a 2 mm hole in the repeller plate of the velocity-mapping ion optics assembly (see

Figure 4). The complete ion optics assembly comprised three electrodes, referred to as the repeller, extractor, and ground plates, respectively. Within the interaction region between the repeller and extractor electrodes, the skimmed molecular beam was intersected at right angles by a high-intensity 800 nm, ∼65 fs laser pulse from a Spectra-Physics Solstice Ti:Sapphire laser. The 1 kHz laser pulses were synchronised with the 20 Hz molecular beam pulses by triggering the pulsed valve from the laser trigger via a clock divider. The trigger signal was also sent to the FastIC module.

Interaction with the laser pulses initiated ionisation and fragmentation of the CF3I or C3H6 molecules in the molecular beam, generating a variety of fragment ions. The electric field maintained within the velocity-mapping ion optics assembly accelerated the ions along a ∼60 cm field-free linear time-of-flight tube to the ion detector, mapping the three-dimensional velocity distributions of the nascent ions into a two-dimensional projection on the front surface of the detector. Of particular note, parent molecular ions that do not undergo fragmentation retain the extremely narrow transverse velocity distribution of the supersonic molecular beam, and are mapped onto a small spot in the centre of the detector. In contrast, dissociation events impart momentum and kinetic energy to the fragments, and fragment ions therefore exhibit characteristic scattering distributions that reflect the forces acting during the dissociation event.

We focused the parent ion beam onto the central pixels of the SiPM array and conducted the experiments under conditions similar to those used with an MCP-based detector, specifically a laser pulse energy of approximately 150 J and an acceleration potential of 7 kV. We acquired k and k thousand ToF cycles for the CF3I and C3H6 molecules, respectively. Additionally, the SiPMs were biased at 59 V, and the FastIC time discriminator threshold was set to be able to record the single-phe signal.

3. Results

3.1. SiPM Array Single-Photon Time Resolution

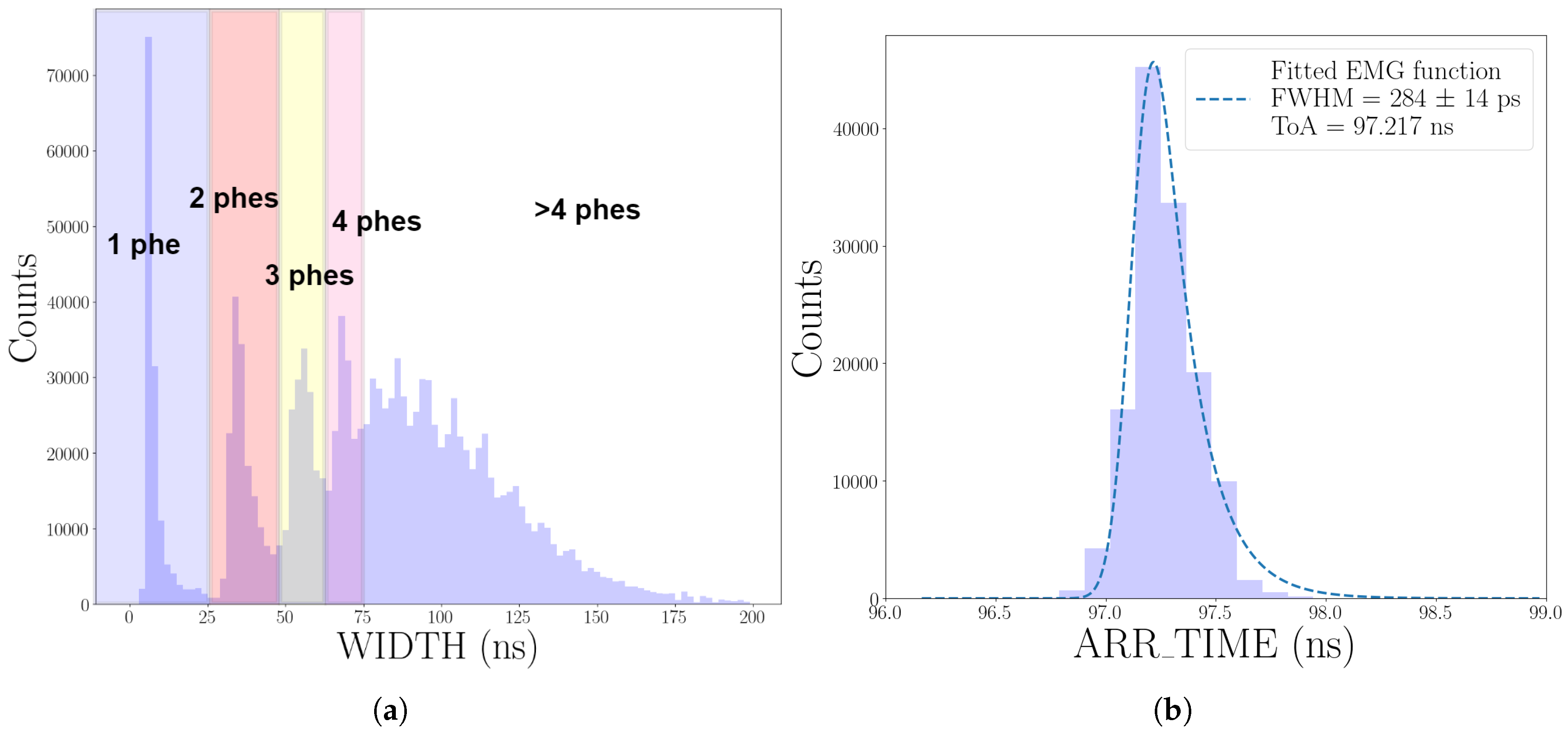

Figure 5 shows the results of a SPTR measurement for one of the channels of the 16-SiPM array, recorded as described in

Section 2.2.1. We consider first the WIDTH distribution shown in

Figure 5 a). The first four peaks correspond to events of one (peak at ∼6 ns), two (∼34 ns), three (∼55 ns) and four (∼68 ns) phes. The peaks are harder to distinguish when the signal is larger due to the non-linear nature of the FastIC operation mode employed (see

Section 2.1).

Figure 5 b) shows the ARR_TIME distribution of single-phe events, fitted with an EMG function. The SPTR obtained, defined as the FWHM of the fitted function, was

ps. This result includes all contributions to the time resolution (laser, SiPM, and readout electronics). However, in this case the contribution from the laser, which has a pulse width of a few tens of ps, is negligible.

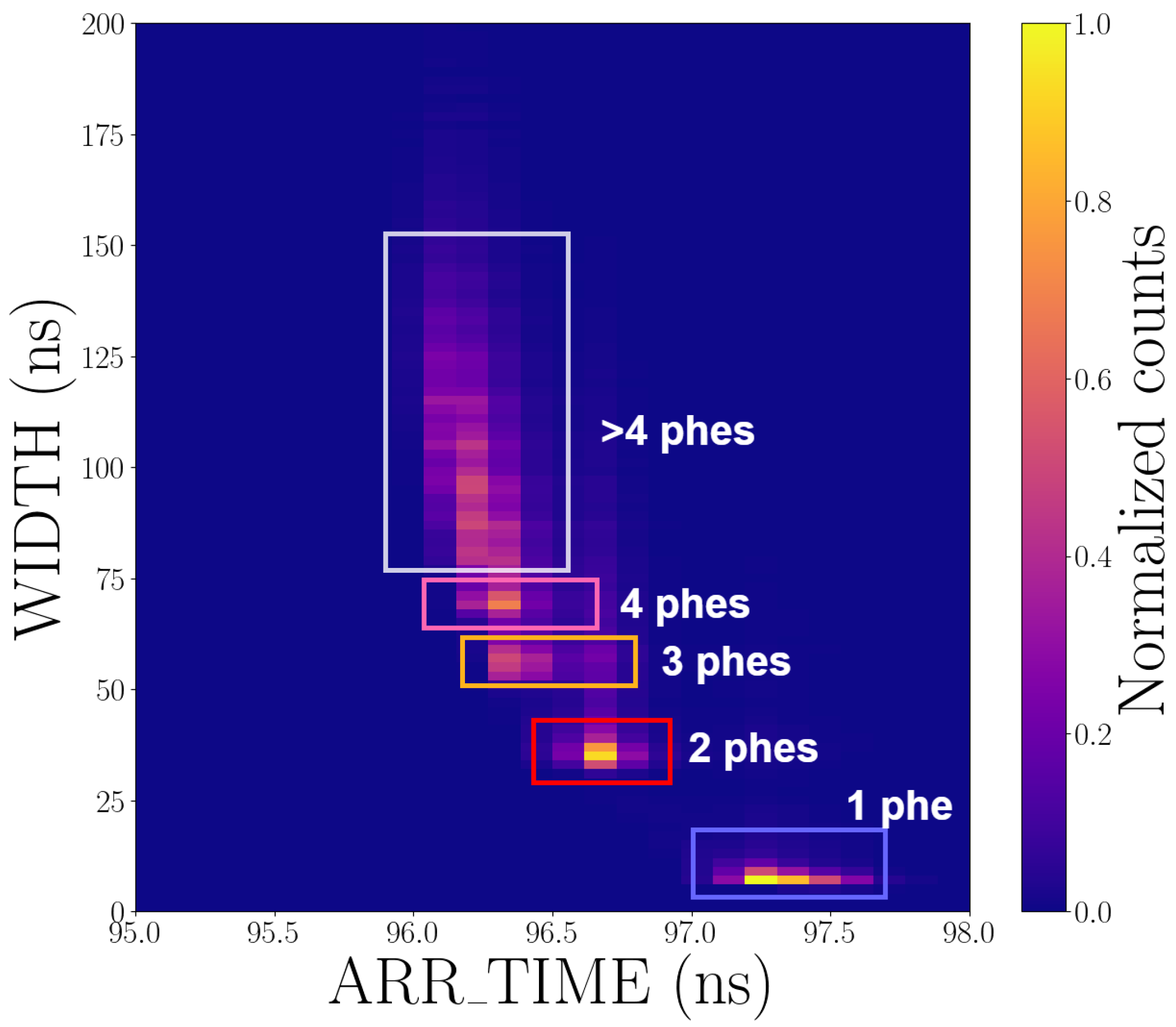

Figure 6 shows a two-dimensional histogram of the WIDTH and ARR_TIME values, revealing a correlation between the ARR_TIME and WIDTH, namely that the mean time of arrival (ToA) is longer for smaller signals. This

time-walk effect is intrinsic to systems that employ a leading-edge discriminator to extract arrival times [

42]. When required, simple correction algorithms can be applied to compensate for this effect [

32,

43,

44]. The correlation plot also shows that the spread of arrival times is larger for weaker signals. As a result, the time resolution of a SiPM typically improves with the intensity of the incoming flux.

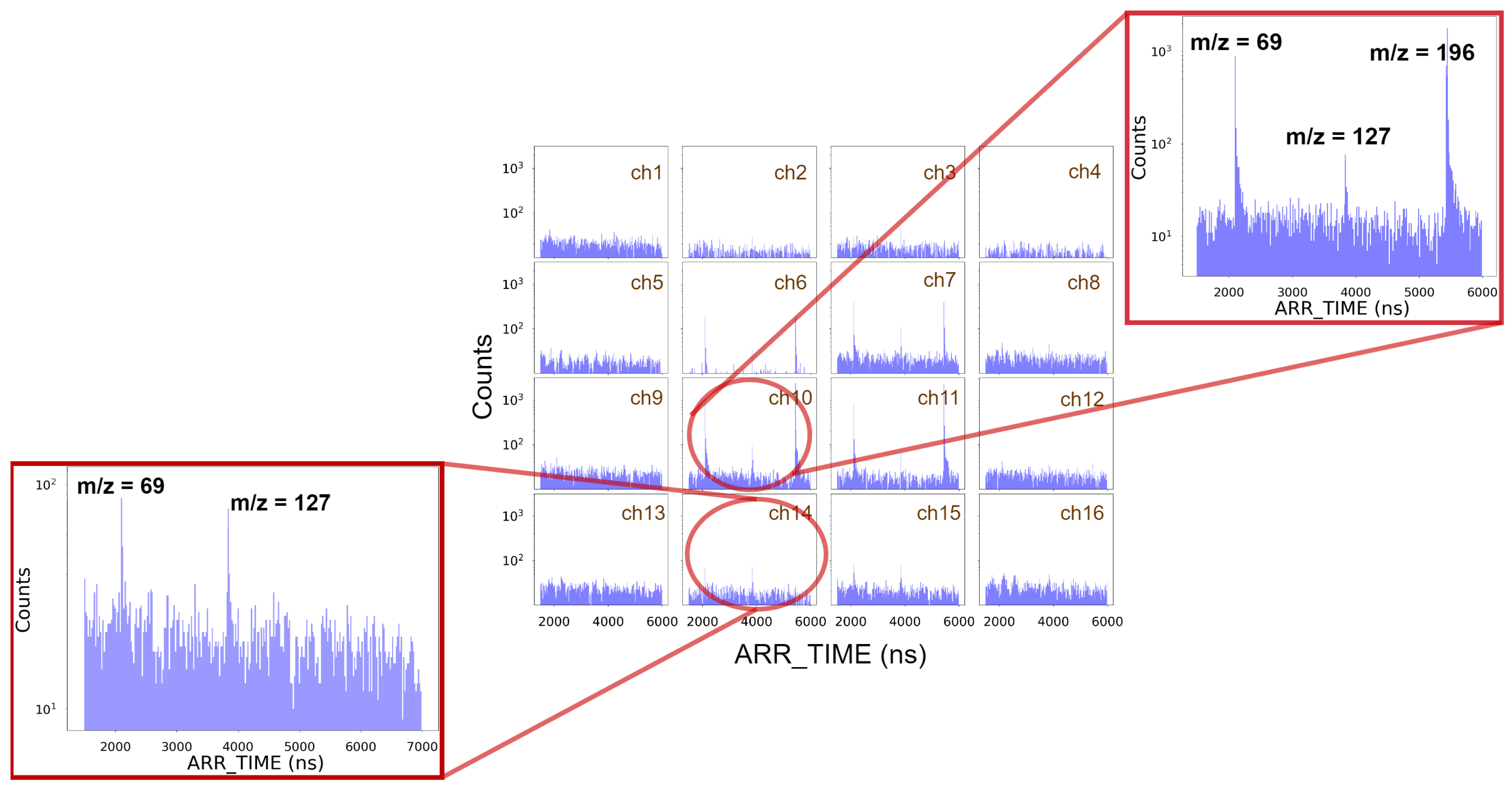

3.2. ToF-System Time Resolution

Figure 7 shows an example of the CF

3I photofragment ion time-of-flight spectra recorded by each SiPM. The three observed peaks correspond to the fragment ions CF

3 + (

) and I

+ (

), and the parent ion CF

3I

+ (

). The parent molecular ion is detected only in the central channels (6, 7, 10 and 11) because it retains the narrow transverse velocity distribution of the supersonic molecular beam, as explained in

Section 2.2.2. On the other hand, the fragment ions show a wider spatial distribution (see channels 14 and 15), especially the I

+ fragment, due to their characteristic scattering distributions resulting from the dissociation event [

45,

46,

47]. As pointed out in

Section 2.2.2, FastIC time comparator threshold was set to detect the single-phe signal. Thus, the background shown in

Figure 7 can be attributed to SiPM optical noise, namely dark counts and crosstalk.

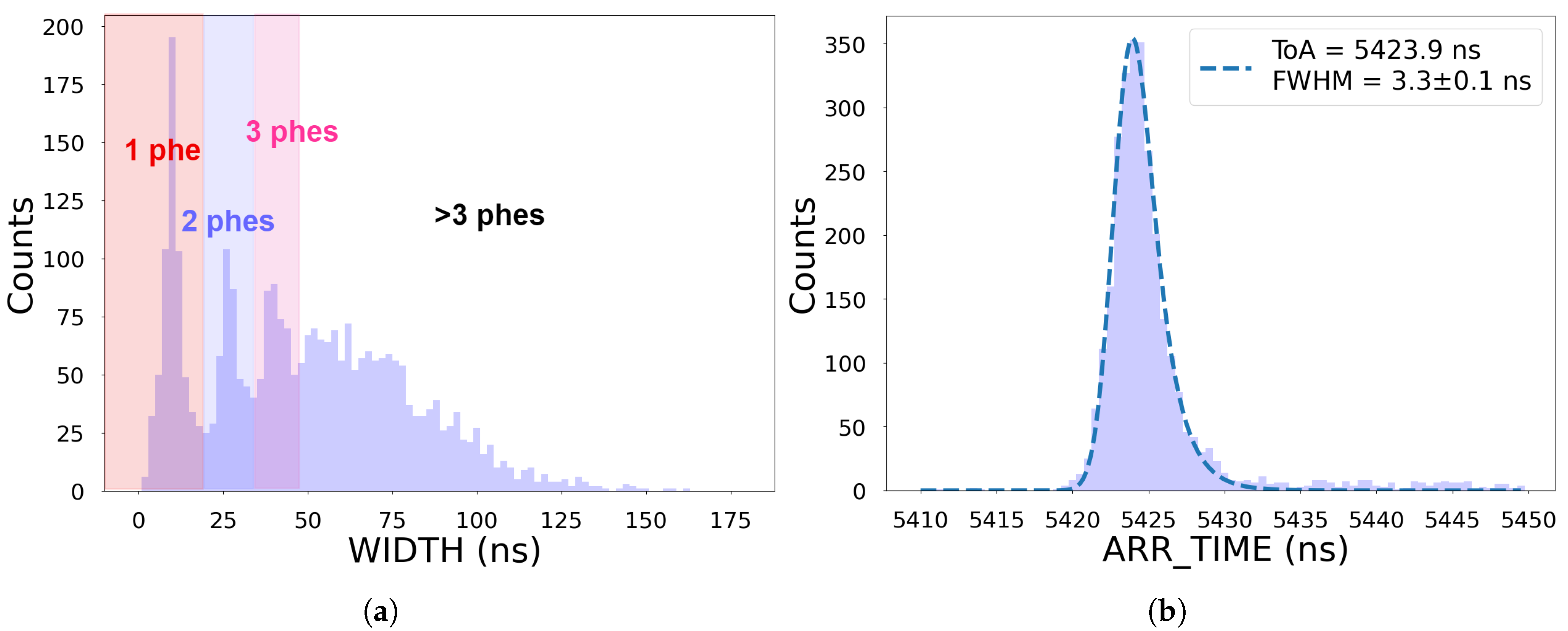

Figure 8 shows the ARR_TIME and WIDTH distributions recorded by pixel 10 for the CF

3I

+ peak. In the WIDTH distribution the peaks corresponding to 1 phe, 2 phes and 3 phes events can be distinguished. This implies that a typical signal collected in a single cycle consists of a few photons. Note that the intensity of the detected flux depends on many parameters, including the number of ions arriving at the scintillator, the number of photons produced in the scintillator, the collection efficiency, and the SiPM PDE. We fitted the ARR_TIME distribution to an EMG function and calculated the FWHM of the fitted function, finding a time resolution of

ns (see right panel in

Figure 8), which is compatible with a mass resolution (

) of ∼ 1200. The time resolution is affected by the time spread with which the ions reach the detector, the scintillator properties (light yield, rise and decay time) and the photodetector intrinsic time resolution (including the electronics).

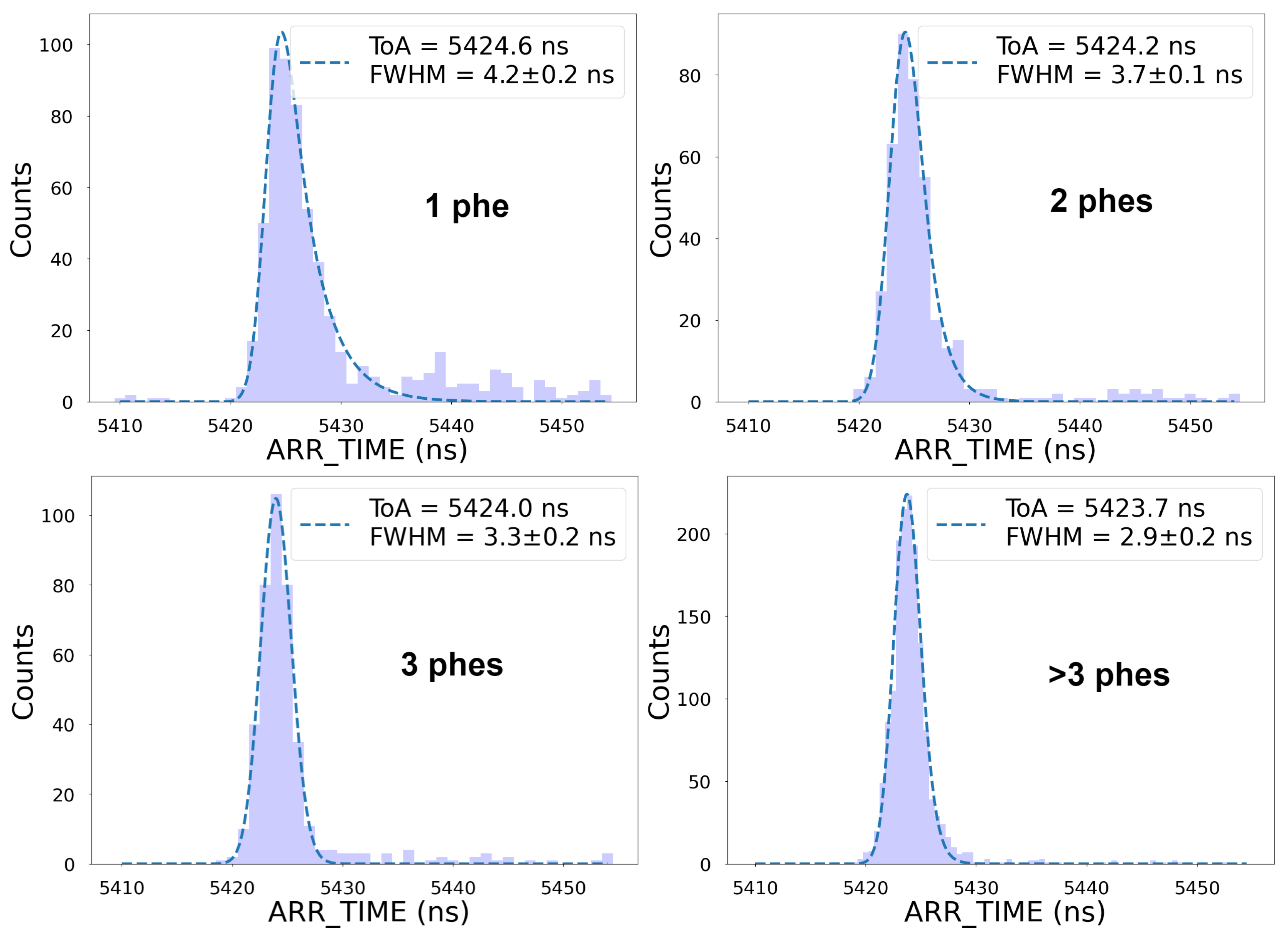

Figure 9 compares the arrival time distribution of the same CF

3I

+ peak after applying different cuts in WIDTH to select events of 1, 2, 3 and

phes, showing that time resolution improves for larger signals. This is primarily because the time jitter associated with the scintillator-photodetector pair decreases as the number of detected photons increases [

48]. The expected jitters associated with scintillator and the photodetector (including electronics) for single-phe events are

ns [

30] and

ps (see section 4.1), respectively. The fact that we found a time resolution larger than 4 ns for single-phe events (top left panel in

Figure 9) suggests that the time resolution of the system must be dominated by the spread in the arrival time of the ions. This spread is much larger than the typical spread associated with the time-walk effects described in

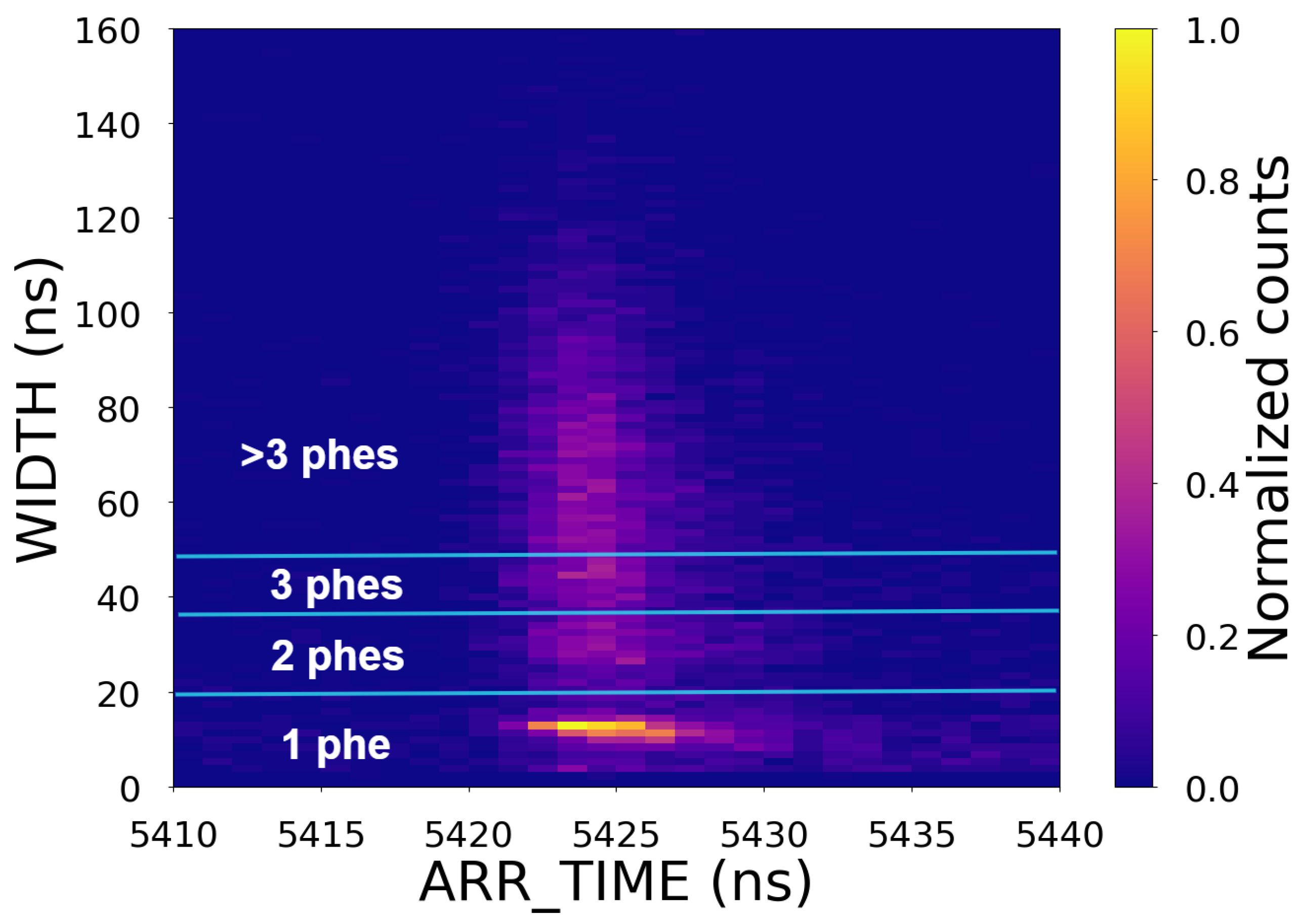

Section 3.1, making any time-walk correction unnecessary. This can be seen in

Figure 10, which shows the measured WIDTH as a function of ARR_TIME, and can be compared with the data shown in

Figure 6.

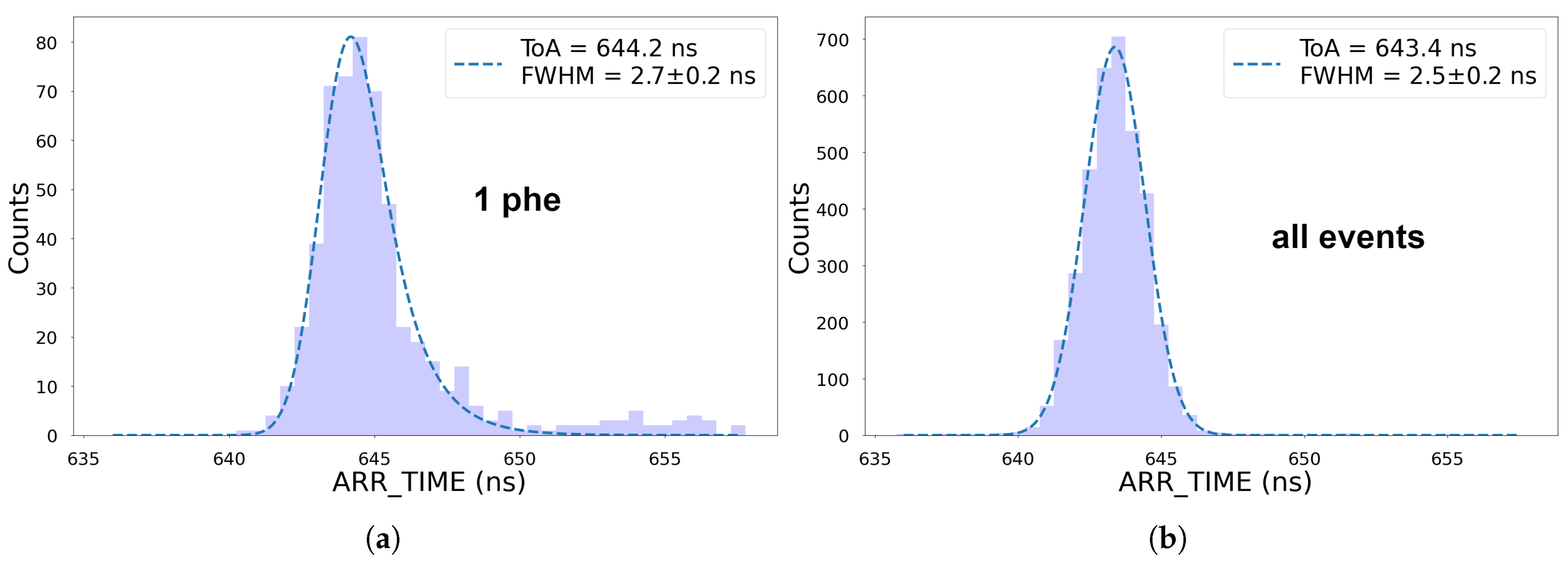

Figure 11 shows the ARR_TIME distribution associated with ions of

(H

2O

+ background ions). The time resolution found when filtering 1-phe events was (

) ns FWHM, which is significantly lower than was found for CF

3I

+. This would have not been the case if the time resolution had not been dominated by the spread of the arrival time of the ions. At low

the ion arrival time spread is narrower and even comparable to the expected jitter associated to the scintillator during 1-phe events. The time resolution found when using all events was (

) ns FWHM, which corresponds to a mass resolution of ∼770.

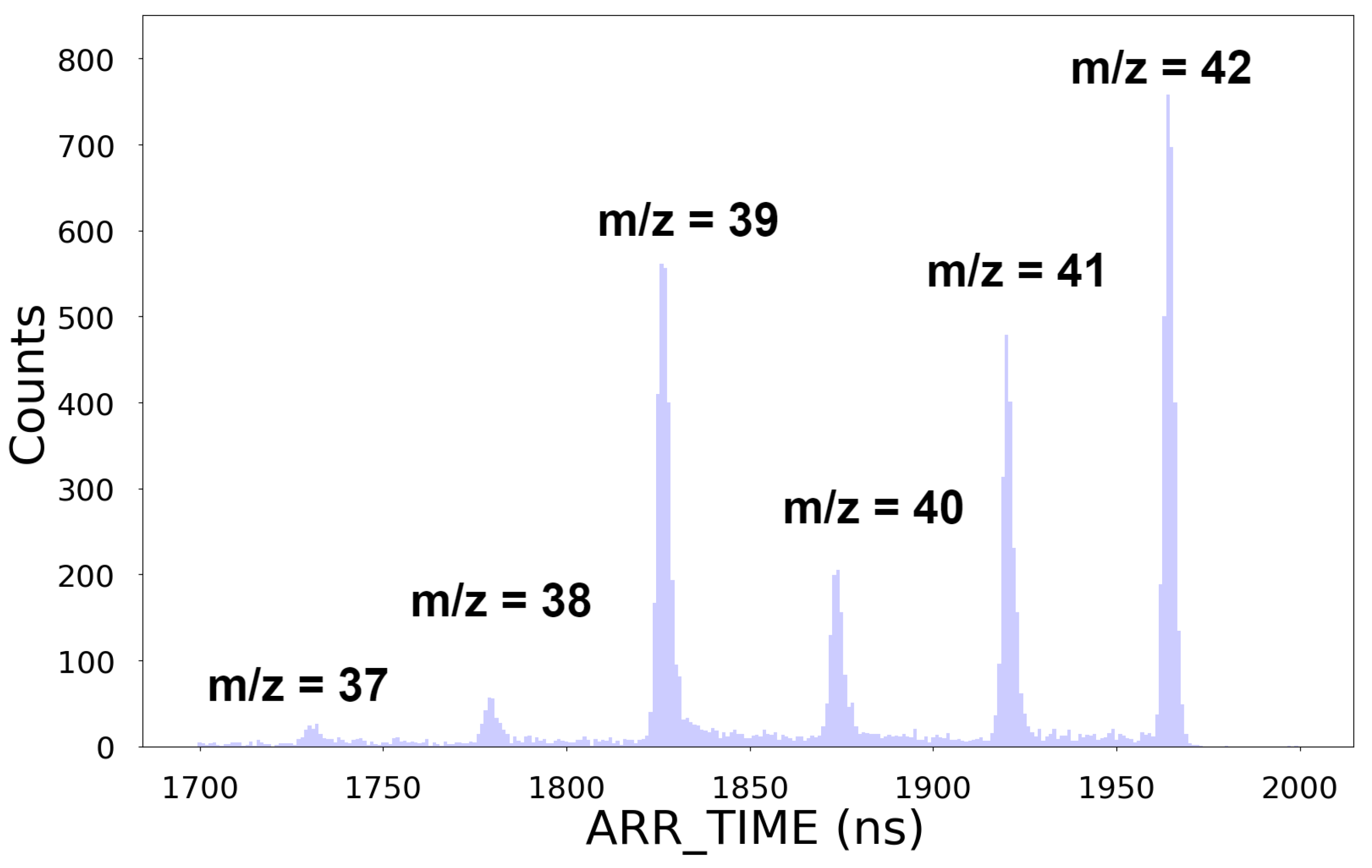

As a second example,

Figure 12 shows a reconstructed photofragment ion time-of-flight spectrum recorded for the molecule C

3H

6. All peaks from

(C

3H

1+) to

(C

3H

6+) can be clearly distinguished. The distance between consecutive peaks is ∼50 ns. We found a mass resolution of

for

.

4. Discussion

We have described, for the first time, the implementation of an ion-to-photon detector for ToF-MS that employs an array of SiPMs. Despite the constraints imposed by the small photodetection area of our prototype and the limited mass resolution of the ToF-MS instrument employed, we were able to record and reconstruct the mass spectra of CF3I and C3H6 and to evaluate the time resolution of the system.

One of the key elements of our detector is the FastIC ASIC, which can process the signals of several SiPMs with compact electronics and low power consumption. Our proof-of-concept prototype employed 16 SiPMs, but since we rely on an ASIC readout, the solution is relatively easily scalable to the hundreds of pixels that would be needed to cover the whole scintillator area [

35]. This will become even more straightforward with the release of the next version of FastIC (named FastIC+), which has its own on-chip TDC. A pixelated detector, in which each channel has its own TDC, offers several advantages. One of these is the ability to deal with high ion rates. A detector such as the one we employed, equipped with 3×3 mm

2 SiPMs, should be capable of handling ion rates higher than

cm

−2 s

−1. Higher ion rates (

cm

−2 s

−1) could be processed if using smaller SiPMs, at the expense of increasing the cost of the detector (since a larger number of SiPMs and FastIC ASICs per unit area would be needed). In this regard the proposed detector should outperform traditional detectors based on MCPs.

A second advantage of our approach is that the detector does not have the stringent vacuum requirements associated with MCP-based detectors. Moreover, SiPMs are robust devices that do not suffer from ageing. They are also much more compact than the PMTs that are used in commercial ion-to-photon conversion detectors, and do not require high-voltages for operation. Taken together, these features open up possibilities for designing compact and portable ToF-MS instruments that could be useful in applications such as space exploration [

49] or environmental monitoring [

50].

Time resolution is a critical parameter for a ToF-MS instrument, since it directly determines the achievable mass resolution. As discussed above in

Section 3.2, the time resolution achieved in the present experiments is mostly dominated by the spread in the arrival time of the ions to the scintillator. Note that when the same VMImMS system is equipped with the PImMS camera [

29], the time resolution is dominated by the photodetector. The ToF-MS instrument used in this study was optimized for imaging the ion velocity distribution, which came at the cost of reduced time resolution. By optimizing the extraction potentials and/or modifiying the ion lens design, it might be possible to improve the overall time resolution of the system.

One of the main limitations of our detector is its low light output. The scintillator has a typical light output of the order of 10 photons per keV of deposited energy, but the actual light output is reduced for low energy particles due to scintillation quenching [

51]. A significant fraction of the scintillation photons are also expected to be lost due to inefficiencies in the light collection. Finally, with a typical PDE of

, we only expect to detect about half of the photons that actually reach the SiPMs. Taken together, these factors explain why most of the signals we observed were events of a few photons. The low light output from the scintillator has a negative impact on the detection efficiency of the system, which, as shown in [

6], could be critical at high

values. We were not able to measure the ion detection efficiency directly in our experiments, as we could not control with enough precision the number of ions hitting the scintillator per cycle. However, we do not expect it to be better than traditional detectors based on MCPs, for which the detection efficiency is mostly dominated by the dead space between the microchannels (typically

of the MCP area).

The low photon flux also limits the time resolution of the detector. The time resolution of a scintillator detector improves rapidly with the number of scintillation photons detected per event [

48]. Considering the fast time response of the scintillator employed and the previous results obtained with FastIC and SiPMs [

32], it should be possible to improve the detector time resolution down to a few tens of ps if we were able to increase the light output.

The intensity of the detected flux can be increased by improving the light collection efficiency. There are a number of ways in which this could be achieved, such as improving the optical coupling of the SiPMs to the exit window or exploring alternative to the traditional light guides. However, in order to obtain a significant boost in the light output we would need to increase the number of scintillation photons generated per incident ion. This could be achieved by accelerating the ions to higher potentials, either within the ion optics or as they approach the detector, or by introducing elements such as converter plates or grids, or even an MCP, to convert the primary ions into secondary ions or electrons.

A camera based on SiPMs and FastIC holds considerable promise for a wide variety of applications in time-of-flight mass spectrometry. In conventional time-of-flight measurements such a system has the potential to provide a considerable boost in ion throughput due to the large number of parallel time-of-flight detection channels. In velocity-map and spatial-map imaging time-of-flight measurements it offers excellent time resolution competitive with the current state-of-the-art [

31], single ion detection sensitivity, and scalable capabilities for recording velocity and/or spatial distributions for ions of interest, all without requiring the use of MCPs and with considerable scope for future improvements in all areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G., D.G. and C.V.; methodology, A.M.-C., D.H, D.M, C.V. and D.G. (Daniel Guberman). ; software, A.M.-C. and J.M.; validation, M.P.; formal analysis, A.M.-C.; investigation, A.M.-C., D.H., D.M., M.P. and D.G.(Daniel Guberman); resources, D.G.(David Gascón), R.B., O.d.-l.-T., A.S., J.A., S.G., J.M., A.M.-C. and C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.-C. and D.G.(Daniel Guberman); writing—review and editing, A.M.-C., D.H., D.M., C.V., D.G., D.G., R.B., S.G.,M.C., M.P., J.M., O.d.-l.-T., A.S. and J.A.; visualization, A.M-C.;project administration, D.G.(Daniel Guberman). ; supervision, D.G.(Daniel Guberman), C.V., R.B. and S.G.; funding acquisition, D.G. (David Gascón), R.B. and C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033, “ERDF A way of making Europe” under Grant PDC2021-121442-10, EPSRC Programme Grants EP/V026690/1 and EP/T021675/1 . This study was also supported by MICIIN with funding from European Union NextGenerationEU(PRTR-C17.I1) and by Generalitat de Catalunya. The research of D. Guberman was supported by a Maria Zambrano Grant, financed by the Spanish Government through the European Union NextGenerationEU fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data can be shared upon reasonable request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Richard Plackett (Department of Physics, University of Oxford) for lending us the voltage source used for biasing the SiPM array, and to the staff of the Oxford Chemistry workshops for their help with the mechanical work and re-soldering of some components.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kharzheev, Y.N. Scintillation counters in modern high-energy physics experiments (Review). Physics of Particles and Nuclei 2015, 46, 678–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoq, P. Development of new scintillators for medical applications. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2016, 809, 130–139, Advances in detectors and applications for medicine,. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddar, A. Plastic scintillation dosimetry and its application to radiotherapy. Radiation Measurements 2006, 41, S124–S133, The 2nd Summer School on Solid State Dosimetry: Concepts and Trends in Medical Dosimetry,. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichelli, M.; Ansoldi, S.; Bari, M.; Basset, M.; Battiston, R.; Blasko, S.; Coren, F.; Fiori, E.; Giannini, G.; Iugovaz, D.; et al. A scintillating fibres tracker detector for archaeological applications. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2007, 572, 262–265, Frontier Detectors for Frontier Physics,. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P.I.; Hays, E.E. Scintillation-Type Ion Detector. Review of Scientific Instruments 1950, 21, 99–100, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/rsi/article-pdf/21/1/99/19026253/99_1_online.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, F.; Knochenmuss, R.; Zenobi, R. An ion-to-photon conversion detector for mass spectrometry. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes 1997, 169-170, 89–98, Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Mass Spectrometry,. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.; Tsai, S.T.; Chen, C.H.; Chen, C.W.; Lee, Y.T.; Wang, Y.S. Bipolar Ion Detector Based on Sequential Conversion Reactions. Analytical Chemistry 2007, 79, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilman, E.S.; Gardiner, S.H.; Nomerotski, A.; Turchetta, R.; Brouard, M.; Vallance, C. A new detector for mass spectrometry: Direct detection of low energy ions using a multi-pixel photon counter. Review of Scientific Instruments 2012, 83, 013304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agilent Mass Spectrometers. Available online: https://www.agilent.com (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Astral Mass Spectrometer. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Exosens detectors for ToF Mass Spectrometers. Available online: https://www.exosens.com (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Winter, B.; King, S.J.; Brouard, M.; Vallance, C. Improved direct detection of low-energy ions using a multipixel photon counter coupled with a novel scintillator. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 397-8, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirn, T. SciFi – A large scintillating fibre tracker for LHCb. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2017, 845, 481–485, Proceedings of the Vienna Conferenceon Instrumentation 2016,. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyratzis, D.; Alemanno, F.; Altomare, C.; Bernardini, P.; Cattaneo, P.; De Mitri, I.; de Palma, F.; Di Venere, L.; Di Santo, M.; Fusco, P.; et al. The Plastic Scintillator Detector of the HERD space mission. PoS 2021, ICRC2021, 054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, D.; Guberman, D.; Aran, A.; Garrido, L.; Gascon, D.; Izraelevitch, F.; Mauricio, J.; Roma, D.; Martín, V.; Nofrarias, M. A low-power SiPM-based radiation monitor for LISA. PoS 2023, ICRC2023, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaercher, R.; da Silveira, E.; Leite, C.; Schweikert, E. Simultaneous detection of secondary ions and photons produced by the impact of keV polyatomic ions. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 1994, 94, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.A.; Axelsson, J.; Sundqvist, B.U.R. Light emission from impacts of energetic proteins on surfaces and a light emission detector for mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 1995, 9, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rey, D.; Zurro, B.; García, G.; Baciero, A.; Rodríguez-Barquero, L.; García-Munoz, M. Ionoluminescent response of several phosphor screens to keV ions of different masses. Journal of Applied Physics 2008, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, B.; King, S.J.; Brouard, M.; Vallance, C. A fast microchannel plate-scintillator detector for velocity map imaging and imaging mass spectrometry. Review of Scientific Instruments 2014, 85, 023306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, J.; Villa, I.; Pedrini, A.; Padovani, E.C.; Crapanzano, R.; Vedda, A.; Dujardin, C.; Bezuidenhout, C.X.; Bracco, S.; Sozzani, P.E.; et al. Composite fast scintillators based on high-Z fluorescent metal–organic framework nanocrystals. Nature Photonics 2021, 15, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshimizu, M. Recent progress of organic scintillators. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2022, 62, 010503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi, F.; Ferri, A.; Gola, A.; Cazzanelli, M.; Pavesi, L.; Zorzi, N.; Piemonte, C. Characterization of Single-Photon Time Resolution: From Single SPAD to Silicon Photomultiplier. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2014, 61, 2678–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoch, S.; Gola, A.; Lecoq, P.; Rivetti, A. Design considerations for a new generation of SiPMs with unprecedented timing resolution. Journal of Instrumentation 2021, 16, P02019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, G.W.; Pearson, J.F.; Smith, G.C.; Lewis, M.; Barstow, M.A. The Gain Characteristics of Microchannel Plates for X-Ray Photon Counting. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 1983, 30, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, A.; Brinkmalm, G.; Barofsky, D. MALDI induced saturation effects in chevron microchannel plate detectors. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry and Ion Processes 1997, 169-170, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemallapudi, M.; Gundacker, S.; Lecoq, P.; Auffray, E. Single photon time resolution of state of the art SiPMs. Journal of Instrumentation 2016, 11, P10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, J.N.; Lee, J.W.; Gardiner, S.H.; Vallance, C. Account: An Introduction to Velocity-Map Imaging Mass Spectrometry (VMImMS). European Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2014, 20, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallance, C.; Brouard, M.; Lauer, A.; Slater, S.; Halford, E.; Winter, B.; King, S.J.; Lee, J.W.L.; Pooley, D.; Sedgwick, I.; et al. Fast sensors for time-of-flight imaging applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 16, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.T.; Crooks, J.P.; Sedgwick, I.; Turchetta, R.; Lee, J.W.L.; John, J.J.; Wilman, E.S.; Hill, L.; Halford, E.; Slater, C.S.; et al. Multimass Velocity-Map Imaging with the Pixel Imaging Mass Spectrometry (PImMS) Sensor: An Ultra-Fast Event-Triggered Camera for Particle Imaging. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2012, 116, 10897–10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orunesajo, E.; Basnayake, G.; Ranathunga, Y.; Stewart, G.; Heathcote, D.; Vallance, C.; Lee, S.K.; Li, W. All-Optical Three-Dimensional Electron Momentum Imaging. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2021, 125, 5220–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromberger, H.; Passow, C.; Pennicard, D.; Boll, R.; Correa, J.; He, L.; Johny, M.; Papadopoulou, C.C.; Tul-Noor, A.; Wiese, J.; et al. Shot-by-shot 250 kHz 3D ion and MHz photoelectron imaging using Timepix3. Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics 2022, 55, 144001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscal-Castilla, A.; Gomez, S.; Manera, R.; Fernandez-Tenllado, J.M.; Mauricio, J.; Kratochwil, N.; Alozy, J.; Piller, M.; Portero, S.; Sanuy, A.; et al. Toward Sub-100 ps TOF-PET Systems Employing the FastIC ASIC With Analog SiPMs. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.; Alozy, J.; Campbell, M.; Fernández-Tenllado, J.; Manera, R.; Mauricio, J.; Pujol, C.; Sanchez, D.; Sanmukh, A.; Sanuy, A.; et al. FastIC: a fast integrated circuit for the readout of high performance detectors. Journal of Instrumentation 2022, 17, C05027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.; Fernandez-Tenllado, J.M.; Alozy, J.; Campbell, M.; Manera, R.; Mauricio, J.; Mariscal, A.; Pujol, C.; Sanchez, D.; Sanmukh, A.; et al. FastIC: A Highly Configurable ASIC for Fast Timing Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC). IEEE, Vol. 15; 10 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floris Keizer, o.b.o.t.L.R.c. The FastRICH ASIC for the LHCb RICH enhancements. In Proceedings of the PM2024 - 16th Pisa Meeting on Advanced Detectors; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.S.; Lipciuc, M.L.; Gardiner, S.H.; Vallance, C. RG+ formation following photolysis of NO–RG via the A˜A˜-X˜X˜ transition: A velocity map imaging study. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2011, 135, 034308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.H.; Karsili, T.N.; Lipciuc, M.L.; Wilman, E.; Ashfold, M.N.; Vallance, C. Fragmentation dynamics of the ethyl bromide and ethyl iodide cations: a velocity-map imaging study. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2014, 16, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipciuc, M.L.; Gardiner, S.H.; Karsili, T.N.; Lee, J.W.; Heathcote, D.; Ashfold, M.N.; Vallance, C. Photofragmentation dynamics of N,N-dimethylformamide following excitation at 193 nm. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2017, 147, 13941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milešević, D.; Stimson, J.; Popat, D.; Robertson, P.; Vallance, C. Photodissociation dynamics of tetrahydrofuran at 193 nm. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2023, 25, 25322–25330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milesevic, D.; Popat, D.; Robertson, P.; Vallance, C. Photodissociation dynamics of N,N -dimethylformamide at 225 nm and 245 nm. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2022, 24, 28343–28352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milešević, D. Photoinduced Chemistry of Biomolecular Building Blocks and Molecules in Space. PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 2023.

- Dolenec, R.; Korpar, S.; Krizan, P.; Pestotnik, R. SiPM timing at low light intensities. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium, 10 2016, Vol. 2017-January, Medical Imaging Conference and Room-Temperature Semiconductor Detector Workshop (NSS/MIC/RTSD). IEEE; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Schmall, J.P.; Judenhofer, M.S.; Di, K.; Yang, Y.; Cherry, S.R. A Time-Walk Correction Method for PET Detectors Based on Leading Edge Discriminators. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences 2017, 1, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratochwil, N.; Gundacker, S.; Auffray, E. A roadmap for sole Cherenkov radiators with SiPMs in TOF-PET. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2021, 66, 195001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köckert, H.; Heathcote, D.; Lee, J.W.L.; Zhou, W.; Richardson, V.; Vallance, C. C-I and C-F bond-breaking dynamics in the dissociative electron ionization of CF3I. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 14296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köckert, H.; Heathcote, D.; Lee, J.W.L.; Vallance, C. Covariance-map imaging study into the fragmentation dynamics of multiply-charged CF3I formed in electron-molecule collisions. Mol. Phys. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Köckert, H.; Heathcote, D.; Popat, D.; Chapman, R.T.; Karras, G.; Majchrzak, P.; Springate, E.; Vallance, C. Three-dimensional covariance-map imaging of molecular structure and dynamics on the ultrafast timescale. Communications Chemistry 2020 3:1 2020, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, S.; van Dam, H.T.; Schaart, D.R. The lower bound on the timing resolution of scintillation detectors. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2012, 57, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, T.; Vuppala, S.; Ayodeji, I.; Song, L.; Grimes, N.; Evans-Nguyen, T. IN SITU MASS SPECTROMETERS FOR APPLICATIONS IN SPACE. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 2021, 40, 670–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich, R.; Cubison, M.J.; Slowik, J.G.; Bukowiecki, N.; Prévôt, A.S.H.; Baltensperger, U.; Schneider, J.; Kimmel, J.R.; Gonin, M.; Rohner, U.; et al. The ToF-ACSM: a portable aerosol chemical speciation monitor with TOFMS detection. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2013, 6, 3225–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, F. Development of organic scintillators. Nuclear Instruments and Methods 1979, 162, 477–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).