Introduction

Laryngeal cancer is still a serious health issue, particularly in high-risk groups. The incidence of laryngeal cancer has increased over the past 30 years, despite advances in treatment options. This upward trend emphasizes the critical importance of early identification and preventive measures [

1].

A substantial number of individuals diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) are often detected at later stages, frequently requiring complete removal of the larynx—even with enhanced diagnostic methods. This operation results in an abrupt loss of voice and impacts breathing function, considerably affecting patients' mental and social quality of life [

2].

Induction chemotherapy (IC), also known as neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), followed by radiation therapy has become an important treatment strategy for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). This combination of therapies significantly improves treatment outcomes, as evidenced by higher tumor response rates and better organ preservation. Induction chemotherapy specifically targets rapidly dividing cancer cells, which helps to reduce tumor size and lower the potential for metastasis [

3]. The subsequent radiation therapy aims to eliminate any remaining cancer cells, thereby decreasing the risk of recurrence. The synergistic effects of these treatment approaches not only increase the rates of complete responses but also allow for more conservative surgical options. This, in turn, helps preserve essential laryngeal functions and enhances the quality of life for patients [

4].

Salt-inducible kinases (SIKs) are a subgroup of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) family [

5]. The family comprises three members: SIK1, SIK2, and SIK3. The expression of SIK1 is regulated by external factors, in contrast to the steady expression levels of SIK2 and SIK3 [

5].

SIK1 (Salt-Inducible Kinase 1), plays a pivotal role in various cellular processes, including metabolic regulation, inflammation, cell cycle progression, stress response, and tumor suppression. It modulates glucose and lipid homeostasis, maintains energy balance, and exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting key mediators like NF-κB, thereby controlling excessive inflammation and supporting immune homeostasis [

6]. SIK1 induces cell cycle arrest at the G1/S checkpoint through the phosphorylation of targets such as CREB-Regulated Transcription Coactivators (CRTCs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), preventing the proliferation of damaged cells, and promotes apoptosis by modulating pro-apoptotic proteins [

7]. Furthermore, SIK1 acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting oncogenic signaling, promoting cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, and reducing inflammation. It also influences gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms by modulating the activity of histone deacetylases (HDACs) and other chromatin-modifying enzymes [

7].

Research has established Salt-Inducible Kinase 1 (SIK1) as a key player in cancer, with roles that are both context-dependent and multifaceted. In certain cancers, SIK1 acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis, thereby preventing uncontrolled cell growth [

8]. Conversely, in other contexts, SIK1 can promote tumor progression by enhancing cell survival and facilitating metastasis through pathways associated with cell invasiveness. Notably, reduced LKB1-SIK1 signaling has been linked to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and increased resistance to radiation therapy in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, highlighting its role in therapeutic resistance [

9].

Although the precise mechanisms through which SIK1 contributes to cancer remain under investigation, emerging evidence highlights its potential as a therapeutic target. Elucidating the complex interactions between SIK1 and other signaling pathways could pave the way for innovative cancer treatments.

This study evaluated the efficacy of induction chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy in patients with locally advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Furthermore, it explored the potential of SIK1 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for this disease, aiming to enhance therapeutic strategies and improve patient outcomes.

Patients and Methods

Between August 2013 and December 2024, a total of 108 patients diagnosed with locally advanced laryngeal cancer were referred to the Clinical Oncology Department and the Head and Neck Surgical Oncology Unit at Zagazig University Hospitals in Zagazig, Egypt, for evaluation and potential inclusion in this study. The research was conducted with the informed consent of each participant, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of the Faculty of Medicine at Zagazig University under the approval number (2013-August-213).

Patient Eligibility Criteria

The study focused on treatment-naive patients, defined as those who had not received any prior therapeutic interventions for their condition. Biopsy results confirmed the presence of squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx in all participants. The disease was classified as locally advanced, specifically stages T3 or T4 with nodal involvement of N0, N1, or N2, according to the staging guidelines established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [

10]. Eligible participants exhibited an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 or better [

11]. They also demonstrated adequate function of key organ systems, including the liver, kidneys, heart, and bone marrow. Furthermore, participants maintained sufficient nutritional and auditory status to undergo the proposed treatment regimen.

Initial Patient Evaluation

The initial evaluation comprised a comprehensive medical history and a detailed physical examination. This was supplemented by a series of diagnostic tests, including a complete blood cell count (CBC), routine serum biochemical tests, and an assessment of creatinine clearance to evaluate renal function. Additionally, all patients underwent a chest X-ray to rule out pulmonary metastases.

Imaging studies were performed to assess the local extent of the disease and to detect any regional metastases. These included either a computed tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the craniofacial region. In cases where patients reported bone pain, bone scintigraphy was conducted to evaluate potential bone involvement.

The size of the primary tumor and the presence of regional metastases were further assessed using triple endoscopy. This procedure involved endoscopic examination of the larynx, pharynx, and esophagus, with biopsies taken from the tumor site and the surrounding normal tissue to confirm the diagnosis and assess the extent of local invasion.

Induction Chemotherapy Regimen

The induction chemotherapy regimen consists of three treatment cycles, each involving the administration of docetaxel at a dose of 75 mg/m² on day 1, cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg/m² on day 1, and a continuous intravenous infusion of fluorouracil at a rate of 500 mg/m²/day from day 1 to day 5. This regimen is repeated every four weeks.

Evaluation of Induction Chemotherapy Efficacy

The effectiveness of the induction chemotherapy regimen was rigorously assessed through a combination of clinical evaluations and radiological imaging. Prior to each treatment cycle, patients underwent endoscopic examinations to monitor tumor response. After the second cycle, radiological imaging using either a computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to provide detailed assessment of tumor size and nodal involvement. Palpable lymph nodes were evaluated through clinical assessment and palpation techniques to detect any changes in size or consistency.

Patients who exhibited a favorable response to chemotherapy, defined as either a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), were eligible to receive a maximum of three courses of chemotherapy before proceeding to definitive radiation therapy. Following the third cycle, patients with CR or PR continued to irradiation, while those showing any signs of disease progression were directed to surgical resection followed by postoperative radiation therapy. Tumor responses were evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria [

12].

All study participants received radiotherapy, which was administered according to a standardized protocol based on their response to chemotherapy. For patients who demonstrated a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) to chemotherapy, radiotherapy was initiated immediately after chemotherapy. In contrast, those who did not respond favorably to chemotherapy proceeded to surgery, followed by postoperative radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy Technique Following Chemotherapy

Radiotherapy was planned and executed following chemotherapy. The key components of the radiotherapy protocol are as follows:

1. Simulation and Planning:

Computed Tomography (CT) Simulation: Patients were immobilized using a thermoplastic mask to ensure accurate and reproducible treatment delivery. CT images acquired during simulation were utilized to delineate target volumes and critical structures.

Target Volume Delineation: The Gross Tumor Volume (GTV) encompassed the primary tumor and any involved lymph nodes. The Clinical Target Volume (CTV) was defined by expanding the GTV by 5–10 mm to account for potential microscopic disease spread. The Planning Target Volume (PTV) was generated by adding a 3–5 mm margin to the CTV to compensate for setup uncertainties and organ motion.

Delineation of Risk Structures: Critical structures, including the spinal cord, salivary glands, and mandible, were meticulously delineated to ensure that radiation doses to these areas were minimized.

2. Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT):

IMRT was employed to deliver highly conformal radiation doses, allowing for the delivery of high doses to the tumor while sparing adjacent healthy tissues.

Dose Painting: This technique enabled the delivery of different radiation doses to various parts of the target volume, thereby optimizing the therapeutic ratio.

3. Dose Fractionation:

Standard Regimen: Following chemotherapy, the primary tumor and involved lymph nodes were treated with a total dose of 70 Gy administered in 35 fractions (2 Gy per fraction) over 7 weeks.

High-Risk CTV: Received a dose of 59.4–63 Gy in 1.8–2.0 Gy per fraction.

Low-Risk CTV (Elective Nodal Regions): Treated with 50–54 Gy in 1.6–1.8 Gy per fraction.

Assessment of Therapeutic Response and Salvage Procedures

The therapeutic response was re-evaluated twelve weeks after the completion of radiation therapy. Patients presenting with persistent laryngeal disease were scheduled for salvage laryngectomy. For those with residual cervical disease but whose primary tumors were under control, a selective neck dissection was performed.

The extent of surgical resection was determined based on the initial assessment of the tumor's extent prior to chemotherapy administration. A conventional wide-field total laryngectomy was conducted for all primary tumors, and regional neck dissections were performed for all surgical candidates. However, this approach was not applied to patients classified as T3N0 or those with midline supraglottic T4N0 tumors, as the specific side of the neck at higher risk for occult metastases could not be determined in these cases.

Salvage surgery was carried out following the confirmation of residual tumor through biopsy. All patients adhered to a systematic follow-up protocol, which included clinical evaluations every three months during the first-year post-treatment and subsequently every six months thereafter.

Analyzing SIK1 mRNA Expression in Tumor and Adjacent Normal Tissues: RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tumor and adjacent normal tissues using Trizol reagent (Gibco Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA). For reverse transcription, 2 μg of total RNA was utilized along with oligo-dT primers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase.

RT-PCR Amplification

RT-PCR products for SIK1 and β-actin were amplified using gene-specific primers from the Roche Universal Probe Library. The primer sequences were as follows:

SIK1:

Forward (F): 5'-GCTCAACCCTCCTTGCATAA-3'

Reverse (R): 5'-GTTCCTTCCGAGGGACTCA-3'

β-actin:

Forward (F): 5'-GCACCAACACCTTCTACAAG-3'

Reverse (R): 5'-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACGATGGAGGG-3'

PCR Reaction Mixture

The PCR reaction mixture consisted of: 3 μL of cDNA , 10 μM of each primer, 2.5 μg/mL of Go Tag Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 3.0 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 40 μL,

PCR Cycling Conditions

PCR amplification was performed in a 9700 Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer) using the following cycling conditions:

Initial denaturation: 95 °C for 2 minutes

30 cycles of: Denaturation: 95 °C for 30 seconds, Annealing: 55 °C for 40 seconds, Extension: 72 °C for 100 seconds, Final extension: 72 °C for 5 minutes

Quantification of SIK1 mRNA Expression

The relative expression levels of SIK1 mRNA were determined based on the average cycle threshold (Ct) values. The expression level of SIK1 was quantified using the comparative Ct (2−

ΔΔCt) method [

13].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. For data that followed a normal distribution, paired t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed to analyze paired data.

The diagnostic efficiency of the tests was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, from which the area under the curve (AUC), specificity, and sensitivity were calculated. Survival analysis was conducted using Kaplan-Meier curves, and differences in survival rates were assessed using the log-rank test.

Results

The study included 108 patients aged 32 to 68, with a median age of 47.5. The majority of the patients were male, and 66 of them were classified as stage III.

Analysis of Treatment Response in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LSCC)

Table 1 presents the response rates of 108 patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) who received induction chemotherapy. The initial response rates were as follows: 29.6% achieved a complete response (CR), 50% showed a partial response (PR), and 20.4% had stable disease (SD). Following the completion of radiotherapy, an assessment conducted at 12 weeks post-treatment, involving 86 patients, revealed a significant shift in response rates. The complete response (CR) rate increased substantially to 64%, while the partial response (PR) rate declined to 18%, and the stable disease (SD) rate dropped to 4%.

Enhancing Laryngeal Function Preservation in LSCC: The Efficacy of Combined Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy

Table 2 outlines the surgical salvage procedures for two patient groups: those who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=22) and those who underwent combined modality therapy with chemotherapy and radiation (n=11).

After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy (n=22):

Total Laryngectomy with Partial Pharyngectomy: Four patients required this extensive procedure, indicating significant disease involvement.

Total Laryngectomy: Twenty patients underwent total laryngectomy, with 10 patients having unilateral and 6 patients having bilateral neck dissection, suggesting advanced disease affecting the larynx and lymph nodes.

Hemi Laryngectomy: Eight patients had hemi laryngectomy with unilateral neck dissection, reflecting a less extensive approach for more localized disease.

After Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy (n=11):

Total Laryngectomy: No patients required this procedure, indicating better disease control with the combined modality therapy.

Hemi Laryngectomy: Eight patients underwent hemi laryngectomy, with two requiring unilateral and six requiring bilateral neck dissection, suggesting significant regional lymph node involvement despite partial laryngeal preservation.

Neck Dissection Only: Fourteen patients had neck dissection only, with 10 having unilateral and 4 having bilateral dissection, indicating persistent or recurrent cervical disease with controlled primary tumors.

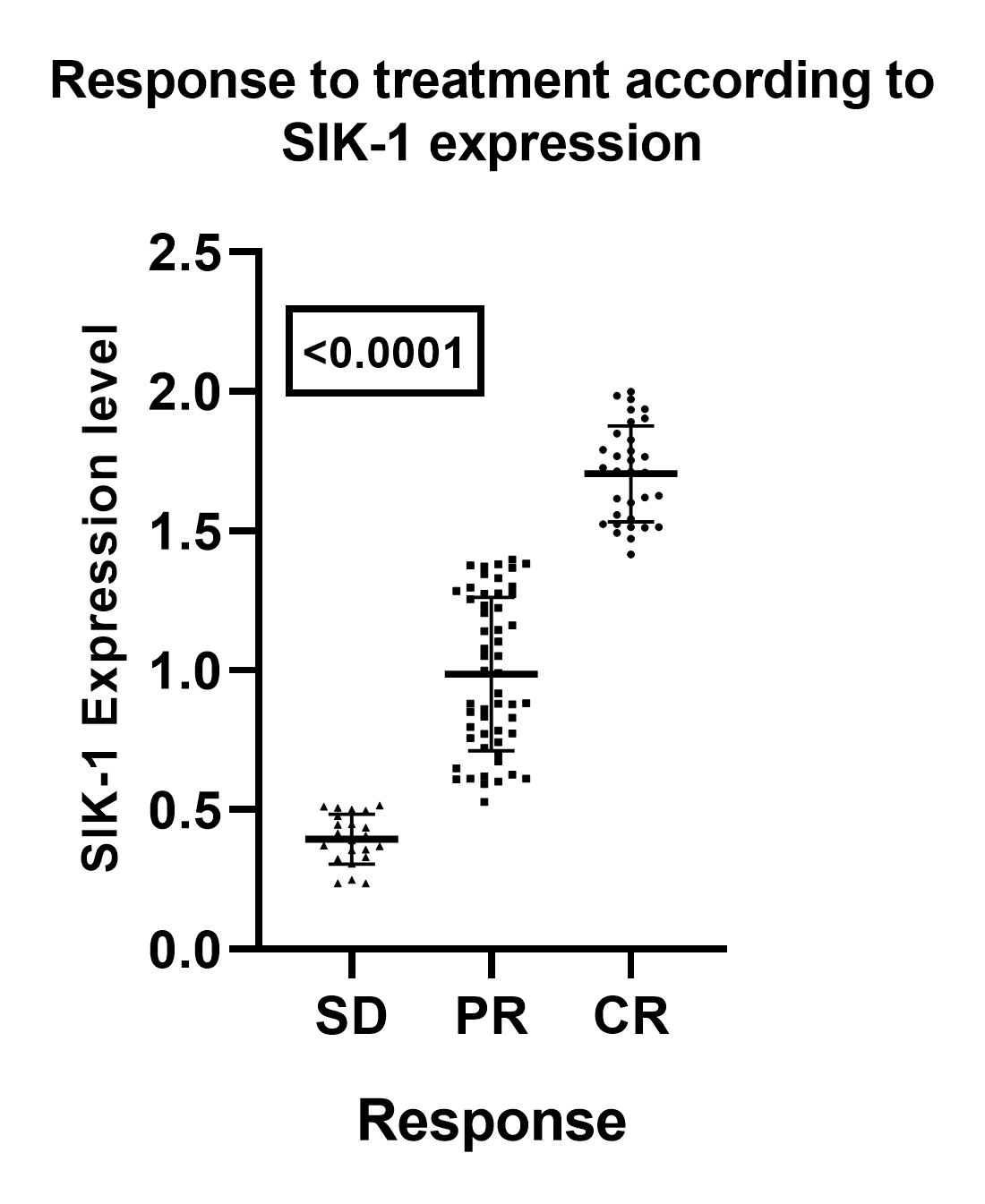

Evaluating SIK-1 as a Diagnostic Biomarker: Comparative Analysis in LSCC and Adjacent Normal Tissues

Figure 1 offer insights into the expression and diagnostic potential of SIK-1 in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) and adjacent normal tissues (ANT).

Figure 1A: illustrates the expression levels of SIK-1 in LSCC and adjacent normal tissues. The data revealing a notable difference between the two tissue types. LSCC tissues exhibit markedly lower expression levels of SIK-1 compared to adjacent normal tissues. This finding suggests that the downregulation of SIK-1 may be associated with the development or progression of LSCC, potentially indicating its role as a tumor suppressor in this context.

Figure 1B: presents the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for SIK-1 expression, evaluating its diagnostic efficiency in distinguishing LSCC from adjacent normal tissues. The ROC curve demonstrates an area under the curve (AUC) of 1.000 with a p-value of < 0.0001, indicating excellent discrimination between LSCC and normal tissues. This high AUC value underscores the strong sensitivity and specificity of SIK-1 as a diagnostic marker for LSCC, suggesting its potential utility in clinical settings for early detection and diagnosis.

Figure1A depicts the expression levels of SIK-1 in LSCC tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues (ANT), showing significantly lower expression in LSCC. Figure1B presents the ROC curve for SIK-1 expression, demonstrating an AUC of 1.000 (p < 0.0001), indicating excellent diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing LSCC from normal tissues.

SIK-1 Expression in LSCC: Association with Clinicopathological Variables and Prognostic Implications

Table 3 presents the analysis of SIK-1 expression in relation to various clinicopathological variables in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). The results indicate significant associations between SIK-1 expression and several key clinical and pathological factors. Patients aged ≤50 years exhibit higher mean SIK-1 expression (1.49) compared to those aged >50 years (0.59), with a highly significant difference (p < 0.0001). Males show lower mean SIK-1 expression (0.936) than females (1.83), with a significant difference (p < 0.0001). Patients with ECOG performance status 0 have higher mean SIK-1 expression (1.248) than those with status 1 (0.426), with a significant difference (p < 0.0001). SIK-1 expression varies significantly across different tumor grades, with well-differentiated tumors showing the highest mean expression (1.774), followed by moderately differentiated (1.206) and poorly differentiated tumors (0.522), with a highly significant difference (p < 0.0001). SIK-1 expression decreases with increasing T stage, from T2 (1.85) to T3 (1.15) and T4 (0.42), with a highly significant difference (p < 0.0001). Similarly, SIK-1 expression decreases with increasing N stage, from N0 (1.77) to N1 (1.12) and N2 (0.45), with a highly significant difference (p < 0.0001). Patients with stage III have higher mean SIK-1 expression (1.42) than those with stage IVA (0.54), with a significant difference (p < 0.0001). These findings highlight the considerable impact of various clinicopathological variables on SIK-1 expression in HNSCC, suggesting that SIK-1 could serve as a valuable biomarker for predicting disease progression and response to treatment, warranting further investigation in clinical settings.

*Student t-test, **One way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

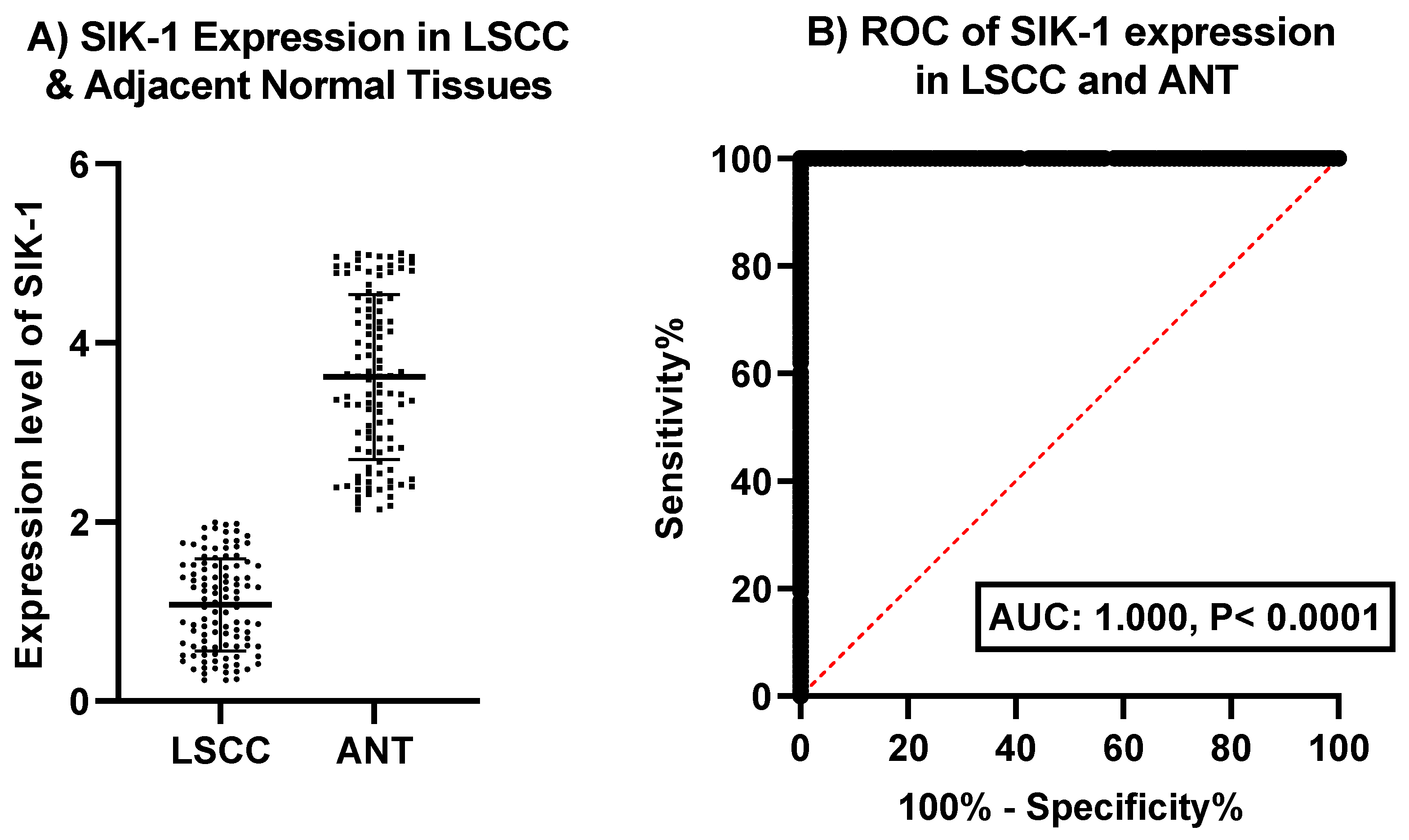

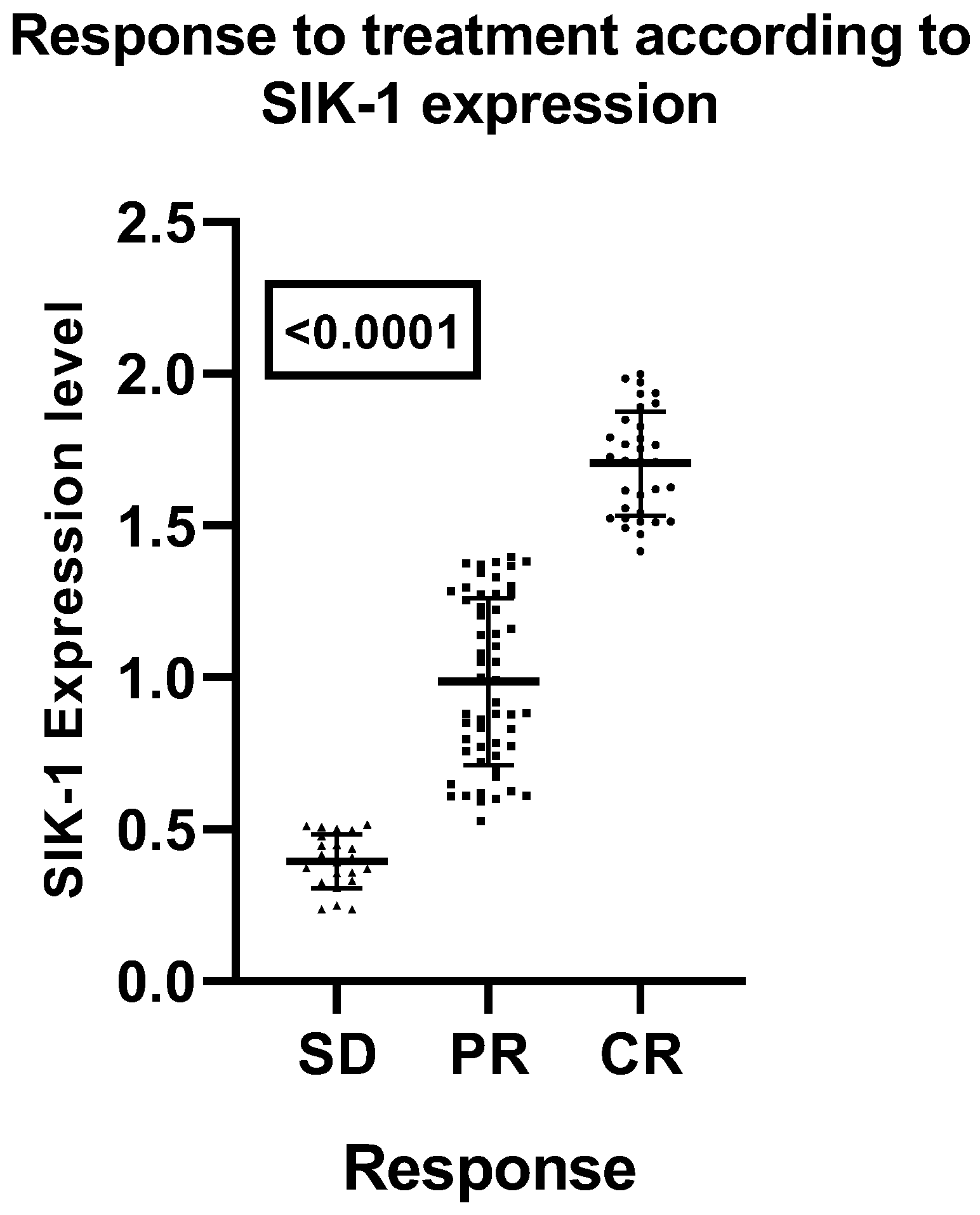

Correlation Between SIK-1 Expression and Treatment Outcomes in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LSCC)

An analysis of SIK-1 expression in relation to treatment response demonstrates a significant correlation between elevated SIK-1 levels and improved outcomes in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). Specifically, higher SIK-1 expression is associated with increased rates of complete responses (CR) and a reduced occurrence of stable disease (SD). This association is statistically significant, as evidenced by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) yielding an F-value of 239.3 and a highly significant p-value of < 0.0001 (

Figure 2).

Multivariate Analysis of SIK-1 Expression in Relation to Clinical and Pathological Variables

The multivariate analysis of SIK-1 expression in relation to various clinical and pathological variables—including age, sex, performance status (PS), pathological grade, T stage, N stage, clinical stage, and treatment response—revealed significant findings, with the model demonstrating a high R-squared value of 0.9721, indicating that 97.21% of the variance in SIK-1 expression can be attributed to these variables. Notably, age exhibited a significant negative relationship with SIK-1 expression (p < 0.0001), suggesting that younger patients tend to have higher SIK-1 levels. Sex also showed a significant positive relationship (p = 0.0076), indicating higher SIK-1 expression in male patients. Additionally, treatment response was a significant negative predictor (p < 0.0001), implying that patients with better treatment responses have lower SIK-1 expression. In contrast, performance status (PS), pathological grade, T stage, N stage, and clinical stage were not significant predictors, as their p-values were greater than 0.05. These results highlight the critical role of age, sex, and treatment response in influencing SIK-1 expression, while suggesting that other traditional clinical and pathological factors may not directly impact SIK-1 levels in LSCC (

Table 4).

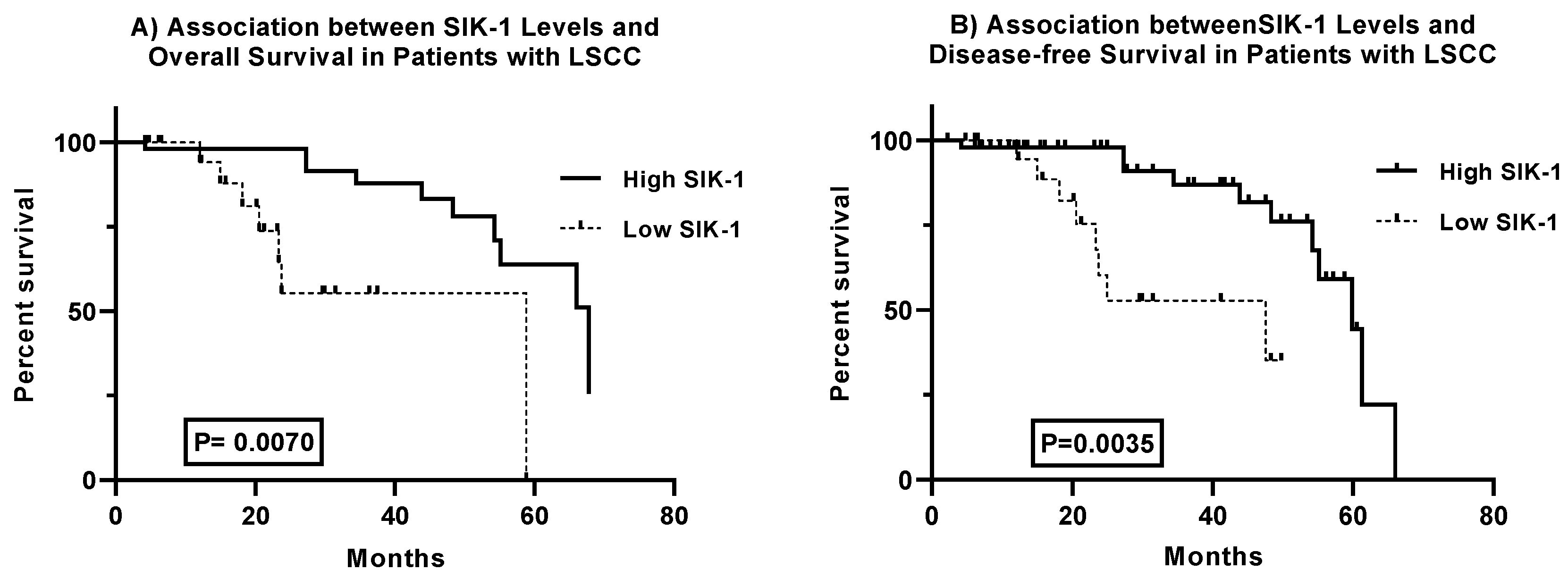

Prognostic Significance of SIK-1 Expression in Laryngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Analysis of Overall and Disease-Free Survival

The analysis of survival curves for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) patients reveals significant differences in both overall and disease-free survival based on SIK-1 expression levels. The comparison of overall survival curves demonstrates significant disparities, with the log-rank test (chi-square = 9.186, p = 0.0024) and the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test (chi-square = 7.285, p = 0.0070) confirming the statistical significance of these differences. Patients with high SIK-1 levels have a median survival of 67.82 months, compared to 58.81 months for those with low SIK-1 levels. Hazard ratios (Mantel-Haenszel: 0.1214, 95% CI 0.03105 to 0.4747; log-rank: 0.2630, 95% CI 0.07084 to 0.9766) indicate that elevated SIK-1 levels are associated with a reduced risk of mortality (

Figure 3A). Similarly, the analysis of disease-free survival curves shows significant differences, with the log-rank test (chi-square = 9.836, p = 0.0017) and the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test (chi-square = 8.520, p = 0.0035) validating the statistical significance of these differences. Patients with high SIK-1 levels exhibit a median disease-free survival of 59.86 months, whereas those with low SIK-1 levels have a median disease-free survival of 47.59 months. Hazard ratios (Mantel-Haenszel: 0.1307, 95% CI 0.03662 to 0.4661; log-rank: 0.2751, 95% CI 0.08231 to 0.9191) suggest that high SIK-1 levels are associated with a decreased risk of disease recurrence (

Figure 3B). Collectively, these findings indicate that SIK-1 may serve as a valuable biomarker for predicting overall and disease-free survival outcomes in LSCC, highlighting its potential utility in clinical prognosis and patient management.

Discussion

The management of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) has evolved to favor combined treatment approaches rather than relying solely on single-modality treatments such as surgery or radiotherapy. Current strategies often include chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and immunotherapy within a multidisciplinary framework. For advanced-stage disease, concurrent chemoradiation has become standard practice, aiming to downstage tumors and eliminate micrometastases [

14].

This combined approach to chemoradiotherapy has significantly improved the management of laryngeal cancer, allowing for laryngeal preservation and enhancing patients' quality of life. In contrast, total laryngectomy, which was the traditional definitive surgery, frequently resulted in functional impairment and reduced quality of life [

15]. Chemoradiotherapy, however, provides a viable alternative that prioritizes organ preservation without compromising oncological control [

16].

By leveraging the synergistic effects of these treatments, this approach improves locoregional control and reduces the risk of recurrence. It achieves high rates of laryngeal preservation, enabling patients to maintain their ability to speak and swallow, thereby minimizing the treatment burden and associated complications [

17].

Our findings demonstrate the efficacy of combined chemoradiotherapy in significantly reducing tumor burden and achieving high rates of laryngeal preservation in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). The observed increase in complete responses following radiotherapy underscores the synergistic benefits of this treatment approach. By preserving the larynx in the majority of patients, this strategy not only improves oncological outcomes but also crucially maintains vital functions such as speech and swallowing, thereby enhancing overall quality of life. These results support the use of induction chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy as a valuable treatment option for LSCC, aligning with the findings of previous studies [

17,

18,

19].

This study aimed to investigate the potential of SIK-1 as a prognostic and diagnostic biomarker for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). To this end, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of 108 LSCC tissue samples and their corresponding adjacent normal tissues using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). Our findings revealed a significant downregulation of SIK-1 expression in LSCC tissues compared to normal tissues. This observation suggests that SIK-1 may act as a tumor suppressor in LSCC, playing a crucial role in inhibiting tumorigenesis and progression. Comparable findings regarding SIK-1 expression have been reported in several other cancer types, including breast carcinoma [

20], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

21], colorectal cancer (CRC) [

22], pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) [

23], and gastric carcinoma [

24]. In these studies, SIK-1 was found to be downregulated, consistent with our observations in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). This suggests a potential role for SIK-1 as a tumor suppressor across multiple cancer types. In contrast, other studies have reported upregulation of SIK-1 in different tumor types, such as certain subtypes of lung cancer and ovarian cancer [

25,

26]. These discrepancies highlight the complexity of SIK-1's role in cancer biology and emphasize the need for further investigation. The varying expression patterns of SIK-1 across different cancers suggest context-dependent functions, which may be influenced by factors such as tumor type, stage, and microenvironment. The contrasting findings regarding SIK-1 expression underscore the importance of context-specific research. While SIK-1 may function as a tumor suppressor in some cancers, its upregulation in others indicates a potential oncogenic role. Future studies should aim to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these divergent effects and explore the therapeutic implications of targeting SIK-1 in various cancer contexts.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of SIK1 expression in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) and adjacent normal tissues (ANT) revealed a perfect area under the curve (AUC) of 1.0, with a 95% confidence interval also indicating perfect discrimination. This, coupled with a significantly low p-value, demonstrates the exceptional discriminatory power of SIK1 expression in distinguishing between LSCC and ANT. This perfect AUC strongly suggests that SIK1 expression has significant potential as a highly sensitive and specific diagnostic biomarker for LSCC. The implications of this finding are substantial for the clinical management of LSCC. The potential for non-invasive diagnostic tools based on SIK1 expression could significantly improve early detection and subsequent treatment outcomes. The robust statistical significance of these results provides strong evidence for the potential incorporation of SIK1 expression into diagnostic protocols for LSCC. Future research should focus on validating these findings in larger, multi-center studies and exploring the feasibility of integrating SIK1-based diagnostics into routine clinical practice.

The observed association between elevated SIK-1 expression and improved treatment outcomes in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) is consistent with findings reported by Gao et al. in colorectal cancer (CRC) [

27]. Specifically, higher levels of SIK-1 expression are linked to increased rates of complete responses (CR) and decreased incidence of stable disease (SD). This relationship suggests that SIK-1 may function as a predictive biomarker for treatment response in LSCC, indicating that patients with higher SIK-1 expression levels are more likely to experience favorable therapeutic outcomes.

Analysis of SIK-1 expression revealed significant associations with several critical clinical factors in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). Notably, higher SIK-1 expression levels were observed in younger patients, females, and those with better performance status. Conversely, SIK-1 expression demonstrated an inverse correlation with tumor grade, clinical stage, and nodal involvement. These findings unequivocally establish SIK-1 as a promising prognostic biomarker for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). SIK-1 expression demonstrates significant correlations with crucial clinical factors, suggesting its potential utility in monitoring disease progression, guiding treatment decisions, and potentially predicting treatment response. Further research is warranted to elucidate its underlying mechanisms and validate its clinical applicability.

Our observations are in line with previous studies conducted by Shi et al. on ovarian cancer [

27], Gao et al. on colorectal cancer [

28], and Anvarnia et al. on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). [

29] These studies similarly reported significant associations between SIK-1 expression and various clinical outcomes, underscoring the potential of SIK-1 as a prognostic biomarker across different cancer types. The consistency of our findings with these earlier investigations strengthens the evidence supporting the role of SIK-1 in cancer biology and its utility as a predictive and prognostic indicator.

Our observations are in line with previous studies conducted by Shi et al. on ovarian cancer [

7], Gao et al. on colorectal cancer [

27], and Anvarnia et al. on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

28]. These studies similarly reported significant associations between SIK-1 expression and various clinical outcomes, underscoring the potential of SIK-1 as a prognostic biomarker across different cancer types. The consistency of our findings with these earlier investigations strengthens the evidence supporting the role of SIK-1 in cancer biology and its utility as a predictive and prognostic indicator.

Multivariate analysis revealed significant associations between SIK-1 expression and several critical clinical and pathological factors in laryngeal cancer. Notably, patient age and treatment response emerged as significant negative predictors of SIK-1 expression, while sex exhibited a positive correlation. Conversely, factors such as performance status and tumor stage did not demonstrate significant associations. These findings highlight the potential of SIK-1 as a valuable prognostic biomarker in laryngeal cancer, with implications for risk stratification and treatment optimization. Further validation studies are warranted to solidify the clinical relevance of SIK-1 in this context.

The survival curve analysis for patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) based on SIK-1 levels shows significant differences in overall survival. The log-rank test (p = 0.0024) indicates that patients with high SIK-1 levels have a median survival of 67.82 months, compared to 58.81 months for those with low SIK-1 levels, suggesting that higher SIK-1 levels are with reduced risk of mortality.

Additionally, there are significant differences in disease-free survival based on SIK-1 levels (log-rank test p = 0.0017). Patients with high SIK-1 levels have a median disease-free survival of 59.86 months, while those with low levels have 47.59 months, indicating that higher SIK-1 levels correlate with a lower risk of recurrence. These findings suggest that SIK-1 may be an important biomarker for predicting both overall and disease-free survival in LSCC. In breast cancer, high levels of SIK1 expression were positively correlated with improved survival compared to low levels of this gene [

29].

By further elucidating the mechanistic role of SIK-1 in tumor behavior and treatment response, we can refine our therapeutic strategies and potentially enhance patient care through more personalized treatment plans. Despite the promising findings, our study has several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the single-center, retrospective design may restrict the generalizability of the results to broader populations. Secondly, the sample size is relatively modest, which could affect the statistical power of the analyses. Additionally, the follow-up period is relatively short, limiting the assessment of long-term outcomes. Furthermore, validation of SIK-1 as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in independent cohorts is essential to confirm its clinical utility. Lastly, there is a lack of mechanistic insights into the role of SIK-1 in LSCC pathogenesis and treatment response, which necessitates further investigation.

Conclusions

This study highlights the effectiveness of combining neoadjuvant chemotherapy with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in achieving tumor control and preserving laryngeal function in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). This integrated treatment approach demonstrates significant potential for enhancing therapeutic outcomes while maintaining critical organ function. Furthermore, the study identifies SIK-1 as a promising diagnostic biomarker, capable of effectively differentiating LSCC from normal tissues. The expression levels of SIK-1 exhibit significant correlations with key clinicopathological factors, suggesting its potential utility in predicting disease progression, treatment response, and patient survival. These findings suggest that SIK-1 may serve as a valuable tool in the clinical management of LSCC, aiding in both diagnosis and prognosis.

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, project No. (TU-DSPP-2024-54).

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-54).

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interests.

References

- Bradford, C.R.; Ferlito, A.; Devaney, K.O.; Makitie, A.A.; Rinaldo, A. Prognostic factors in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2020, 5, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Zhang, S.; Yu, S.; Ma, F.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; et al. Cellular heterogeneity landscape in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. International journal of cancer. 2020, 147, 2879–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.-G.; Wang, R.-J.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, X.-Y. Neoadjuvant therapy with chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor for laryngeal function preservation in locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024, 15, 1364799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Zhuge, L.; et al. Survival and long-term quality-of-life of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus surgery followed by radiotherapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy for the treatment of resectable stage III/IV hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2023, 46, 3693–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.W.; Brady, J.J.; Tsai, M.K.; Li, C.; Winters, I.P.; Tang, R.; et al. An LKB1–SIK axis suppresses lung tumor growth and controls differentiation. Cancer discovery. 2019, 9, 1590–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, A.; Taylor, L.; Ru, Y.; Wakaf, Z.; Akpobaro, K.; Vasudevan, S.; et al. The multiple roles of salt-inducible kinases in regulating physiology. Physiological Reviews. 2023, 103, 2231–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, B. Roles of salt-inducible kinases in cancer. International Journal of Oncology. 2023, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L.; Xue, L.; Tian, X.; et al. KLF12 Interacts with TRIM27 to affect Cisplatin Resistance and Cancer Metastasis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by regulating L1CAM Expression. Drug Resistance Updates. 2024, 101096. [Google Scholar]

- Hollstein, P.E.; Eichner, L.J.; Brun, S.N.; Kamireddy, A.; Svensson, R.U.; Vera, L.I.; et al. The AMPK-related kinases SIK1 and SIK3 mediate key tumor-suppressive effects of LKB1 in NSCLC. Cancer discovery 2019, 9, 1606–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Fernández, E.; Palacios-García, J.M.; Moreno-Luna, R.; Herrero-Salado, T.; Ventura-Díaz, J.; Sánchez-Gómez, S.; et al. Survival analysis in patients with laryngeal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Life. 2023, 13, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Hung, Y.-S.; Yu, S.-M.; Hsueh, S.-W.; Chou, W.-C. Integrating Frailty Assessment to Enhance Care in Cancer Patients with Borderline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine® 2024, 10499091231226062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, M. Tumor response assessment for precision cancer therapy: response evaluation criteria in solid tumors and beyond. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book. 2018, 38, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cho, J.; Park, J.; Hwang, J.H. Identification and validation of stable reference genes for quantitative real time PCR in different minipig tissues at developmental stages. BMC genomics. 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.; Li, W.; Bao, X.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Additional value of dynamic iodine concentration derived from dual-energy CT in larynx preservation decision following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clinical Radiology. 2025, 80, 106749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.W.; Han, J.S.; Kim, G.-J.; Basurrah, M.A.; Hwang, S.H. The prognostic utilities of various risk factors for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina. 2023, 59, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leblanc, A.; Thomas, T.V.; Bouganim, N. Chemoradiation for locoregionally advanced laryngeal cancer. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 2023, 56, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomkvist, R.; Marklund, L.; Hammarstedt-Nordenvall, L.; Gottlieb-Vedi, E.; Mäkitie, A.; Palmgren, B. Treatment and outcome among patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in S tockholm—A population-based study. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 2023, 8, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Re, M.; Ceka, A.; Rubini, C.; Ferrante, L.; Zizzi, A.; Gioacchini, F.M.; et al. Micro RNA-34c-5p is related to recurrence in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. The Laryngoscope. 2015, 125, E306–E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, O.; Loughran, S. New Developments in the Management of Laryngeal Cancer. International Journal of Head and Neck Surgery. 2017, 9, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, L.; Manoharan, R. Distinctive role of SIK1 and SIK3 isoforms in aerobic glycolysis and cell growth of breast cancer through the regulation of p53 and mTOR signaling pathways. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 2021, 1868, 118975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; He, D.; Lu, X.; Dong, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Salt-inducible Kinase (SIK1) regulates HCC progression and WNT/β-catenin activation. Journal of hepatology. 2016, 64, 1076–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Hu, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; et al. MicroRNA-17 promotes cell proliferation and migration in human colorectal cancer by downregulating SIK1. Cancer management and research. 2019, 3521–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.-G.; Dong, S.-X.; Han, P.; Qi, J. miR-203 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion by degrading SIK1 in pancreatic cancer. Oncology reports. 2016, 35, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, X.; Jiang, J.; Gu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Circular RNA EIF4G3 suppresses gastric cancer progression through inhibition of β-catenin by promoting δ-catenin ubiquitin degradation and upregulating SIK1. Molecular Cancer. 2022, 21, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xue, P.; Han, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, L.; et al. Exosomal miR-130b-3p targets SIK1 to inhibit medulloblastoma tumorigenesis. Cell Death & Disease. 2020, 11, 408. [Google Scholar]

- Hartono, A.B.; Kang, H.-J.; Shi, L.; Phipps, W.; Ungerleider, N.; Giardina, A.; et al. Salt-inducible kinase 1 is a potential therapeutic target in desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Oncogenesis. 2022, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Yao, X. SIK1 suppresses colorectal cancer metastasis and chemoresistance via the TGF-β signaling pathway. Journal of Cancer. 2023, 14, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvarnia, A.; Panahizadeh, R.; Zarredar, H.; Asadi, M.; Hashemzadeh, S.; Vatankhah, M.A.; et al. Down-Regulation and Clinic-Pathological Correlation of SIK-1 and SIL-1-LNC in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 2023, 24, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Rivera, A.; Alzoubi, M.; Wathieu, H.; Dong, S.; Yousefi, H.; et al. Evaluation of liver kinase B1 downstream signaling expression in various breast cancers and relapse free survival after systemic chemotherapy treatment. Oncotarget. 2021, 12, 1110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).