Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

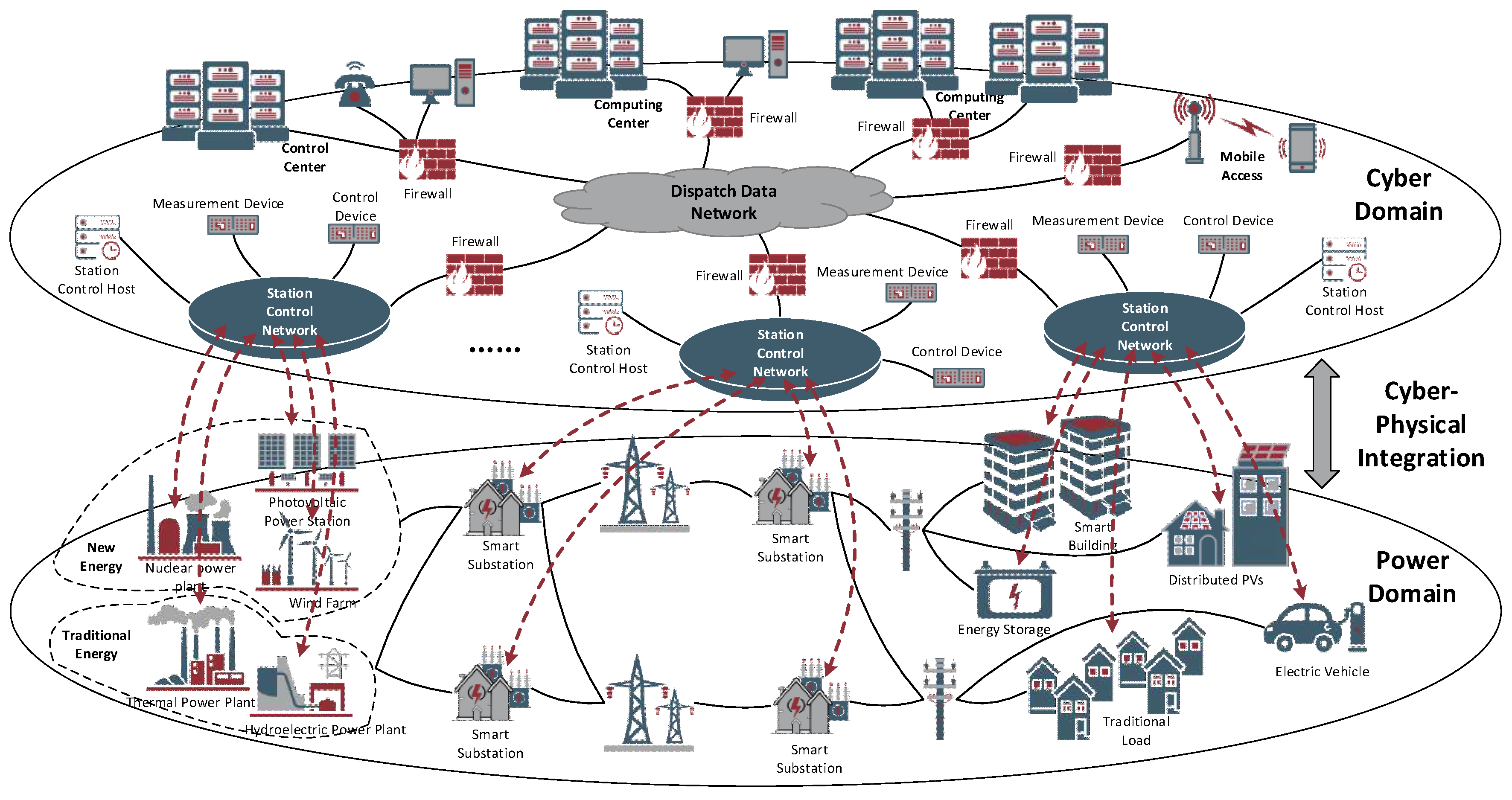

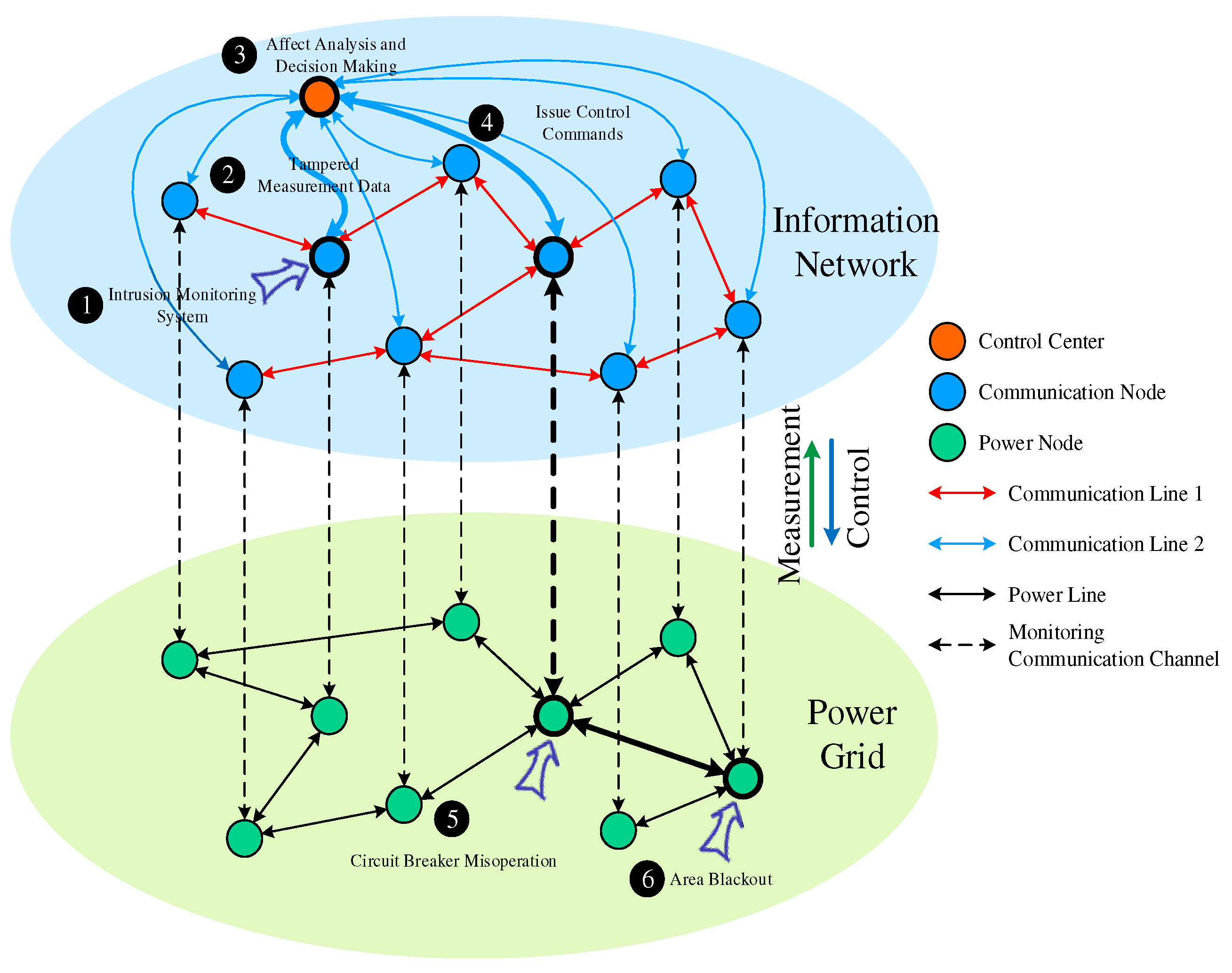

This review provides a comprehensive overview of data injection attacks (DIAs) in power systems, addressing their evolution, detection, and mitigation within the broader context of cyber-physical system security. With the integration of advanced information technologies and smart grid components, power systems are increasingly vulnerable to cyber threats that can disrupt their operational integrity. The article discusses various forms of DIAs, including false data injection attacks (FDIAs) and dummy data injection attacks (DDIAs), and their impact on system reliability and security. It explores the development of sophisticated attack modeling that accounts for multi-ple types of DIAs, enhancing detection methodologies through data-driven approaches and ma-chine learning algorithms. Additionally, it highlights the importance of precise attack localization and proactive defense mechanisms that adapt dynamically to detected threats. The review also ad-dresses the integration of cyber and physical security measures as a unified approach to safeguard against these evolving cyber threats. By providing a detailed examination of current challenges and emerging trends, the review sets the stage for future research directions that focus on enhancing the resilience and security of power systems against complex and coordinated cyber attacks.

Keywords:

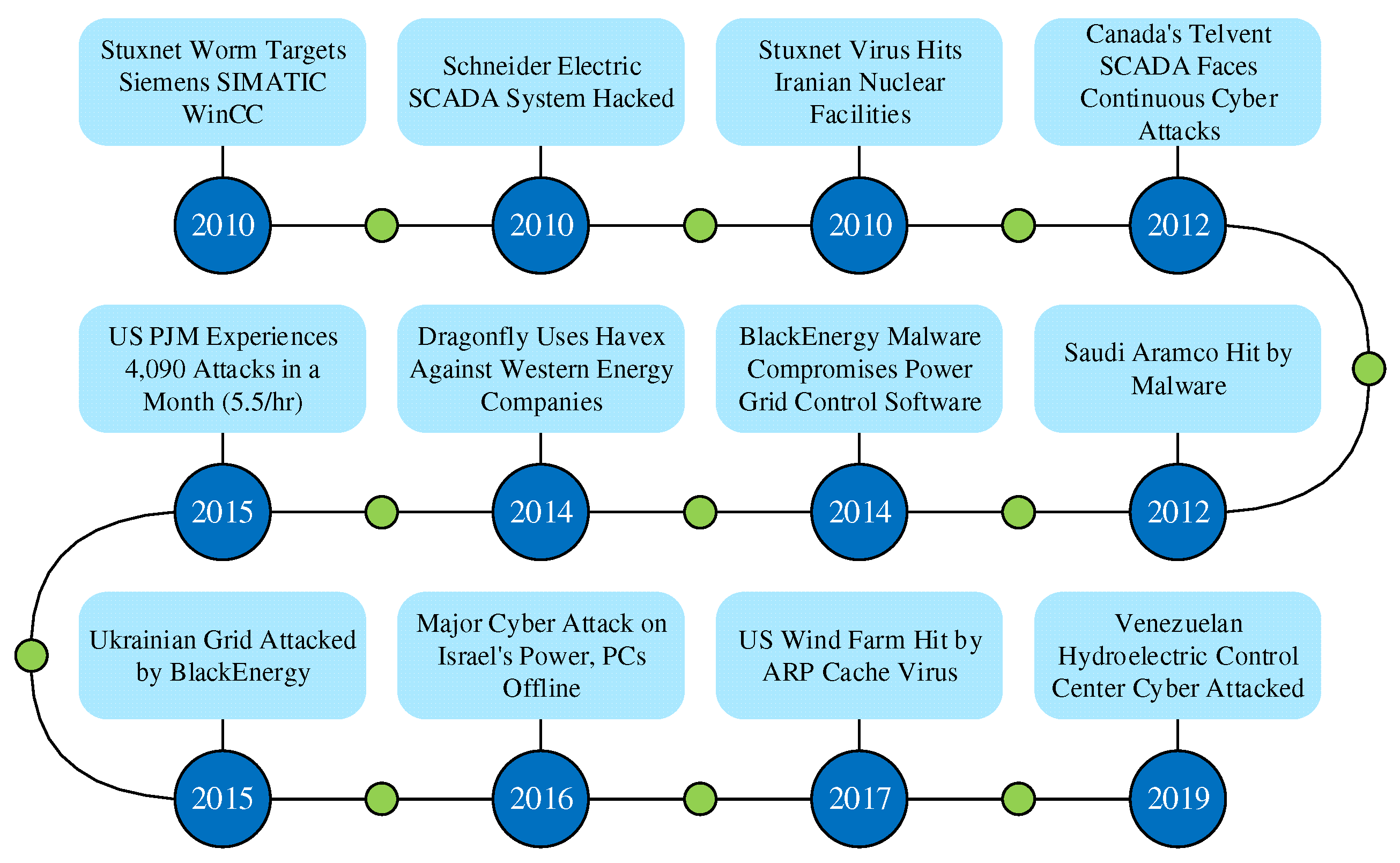

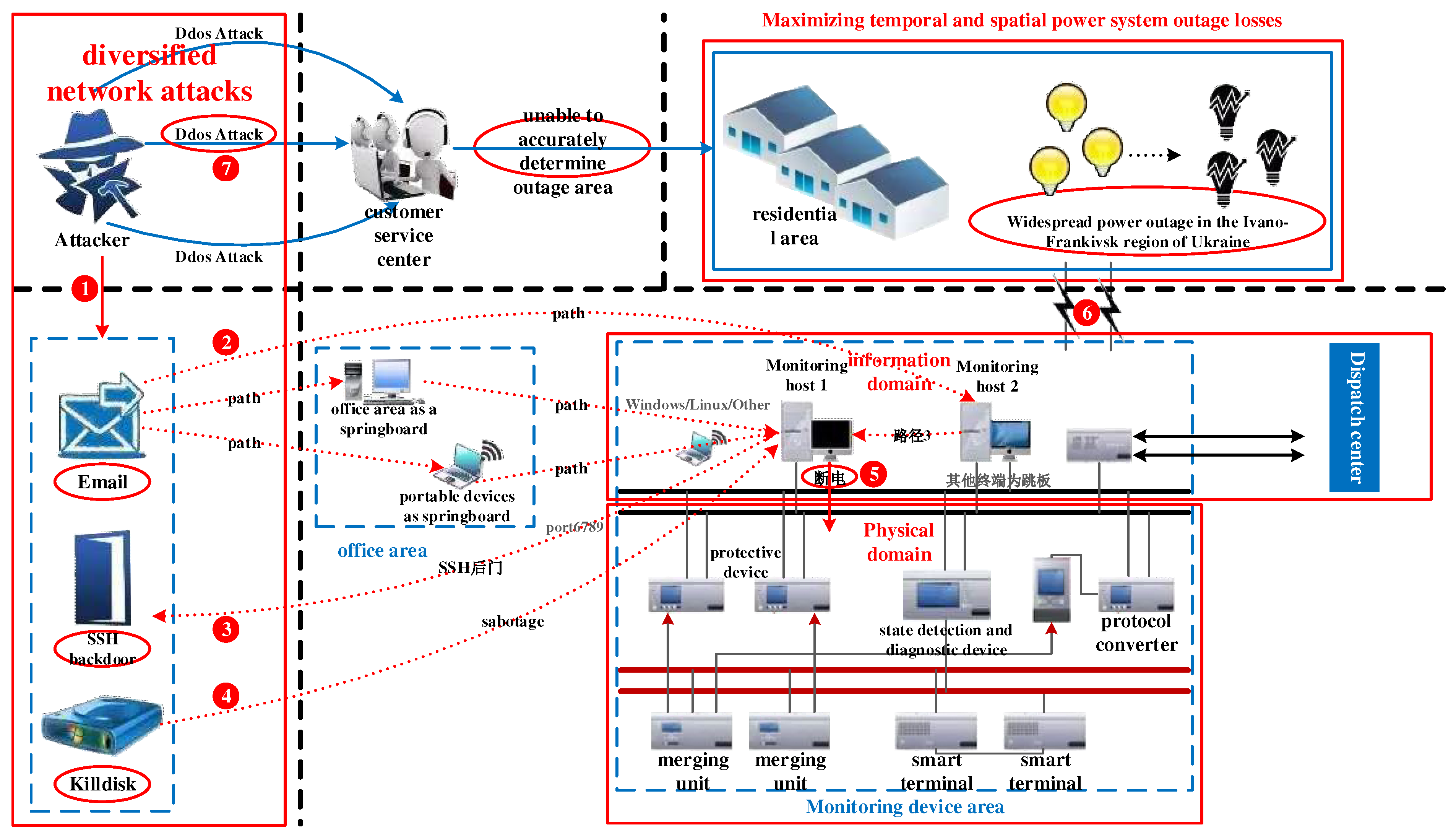

1. Introduction

2. Current Research on DIA in Power Systems

2.1. Attack Targets of DIA in Power Systems

2.2. DIA Modeling Methods

2.3. DIA Detection Methods

2.3.1. State Estimation-Based DIA Detection

2.3.2. Dynamic State Estimation

2.3.3. Graph-Theoretical Models

2.3.4. Physical Property-Based Detection

2.3.5. Data-Driven Detection Methods

2.4. DIA Localization Methods

2.5. DIA Defense Methods

2.5.1. Proactive Protection of Critical Devices

2.5.2. Optimization of Attack-Defense Resource Configuration

2.5.3. Moving Target Defense

2.5.4. Active Defense through Measurement Data Recovery and Correction

3. Existing Issues and Trends in Research on DIA in Power Systems

3.1. Modeling Limitations

3.2. Detection Challenges

3.3. Analysis Limitations

3.4. Traditional Defense Shortcomings

4. Future Research Directions

4.1. Advanced Attack Modeling

4.2. Enhanced Attack Identification Techniques

4.3. Precise Attack Localization

4.4. Proactive and Adaptive Defense Mechanisms

4.5. Integrating Cyber-Physical Systems Security

5. Conclusion

References

- Liu, Z.; Wang, L. Leveraging Network Topology Optimization to Strengthen Power Grid Resilience Against Cyber-Physical Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 12, 1552–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ti, B.; Li, G.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J. Resilience Assessment and Improvement for Cyber-Physical Power Systems Under Typhoon Disasters. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 13, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, M.; Faraji, J.; Hashemi-Dezaki, H.; Ketabi, A. A novel clustering-based method for reliability assessment of cyber-physical microgrids considering cyber interdependencies and information transmission errors. Appl. Energy 2022, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X. A Review of Detection, Evolution, and Data Reconstruction Strategies for False Data Injection Attacks in Power Cyber-Physical Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.10441. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xu, P.; Qu, Z.; Bo, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Coordinated Cyber-Attack Detection Model of Cyber-Physical Power System Based on the Operating State Data Link. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, Y. , et al. Determination Method of Network Risk Propagation Threshold in Power CPS Based on Percolation Theory. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2020, 44, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Shahidehpour, M.; Li, J.; Long, C. Data-driven distributionally robust scheduling of community integrated energy systems with uncertain renewable generations considering integrated demand response. Appl. Energy 2023, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Liu, S. , et al. Security technology for ubiquitous electric power IoT based on biological immunology methods. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2020, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Tian, J.; Wang, J.Z. , et al. Comprehensive security threats and defenses research for cyber-physical systems. Acta Automatica Sinica 2019, 45, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, N.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y. Method for Quantitative Estimation of the Risk Propagation Threshold in Electric Power CPS Based on Seepage Probability. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 68813–68823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.Y.; Yang, G.H. False data injection attacks against state estimation without knowledge of estimators. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 2022, 67, 4529–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Qu, N. , et al. Quantitative Assessment of Survivability of Power CPS Considering Load Optimization and Reconfiguration. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2019, 43, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Li, M.Y.; Tang, Y. , et al. A review on cyber-attack and defense research for electrical cyber-physical systems (Part I): Modeling and assessment. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2019, 43, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Xin, S.; Wang, J. , et al. Comprehensive security assessment of information-energy systems observed from the Ukraine blackout incident. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2016, 40, 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J. , et al. Network coordinated attacks: Deduction and insights from the Ukraine blackout incident. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2016, 40, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, X.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Dong, Y.; Qu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Modeling Method for the Coupling Relations of Microgrid Cyber-Physical Systems Driven by Hybrid Spatiotemporal Events. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 19619–19631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairy, F.; Scekic, L.; Elmoudi, R.; Wshah, S. Accurate Detection of False Data Injection Attacks in Renewable Power Systems Using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 135774–135789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Li, Y. , et al. Enhancing Cyber-Resilience in Integrated Energy System Scheduling with Demand Response Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Applied Energy 2025, 379, 124831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, S.; Jiang, T.; Li, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L.; Bo, X.; Zang, J.; et al. Localization of dummy data injection attacks in power systems considering incomplete topological information: A spatio-temporal graph wavelet convolutional neural network approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Detection of False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grid: A Secure Federated Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM)., LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–1.

- Wang, L.; Qu, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, K.; Sun, J.; Xue, K.; Cui, M. Method for Extracting Patterns of Coordinated Network Attacks on Electric Power CPS Based on Temporal&x2013;Topological Correlation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 57260–57272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Qu, N.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mugemanyi, S. Survivability Evaluation Method for Cascading Failure of Electric Cyber Physical System Considering Load Optimal Allocation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, N.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, T.; Li, M.; Long, C. Extraction of typical operating scenarios of new power system based on deep time series aggregation. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. Stacked Autoencoder Framework of False Data Injection Attack Detection in Smart Grid. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, L. Dynamic State Estimation of Generators Under Cyber Attacks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 125253–125267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Srivastava, A.; Guo, Y.; Ćetenović, D.; Lin, Y.; Levi, V.; Yin, G.; Huang, M.; Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; et al. State Estimation for Integrated Energy Systems: Motivations, Advances, and Future Work. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, PP, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, M.; Hui, X.; Gu, S. Robust Dynamic State Estimator of Integrated Energy Systems Based on Natural Gas Partial Differential Equations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 3303–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. , et al. PMU measurements-based short-term voltage stability assessment of power systems via deep transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 2526111. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, A.; Nabipour, M.; Taheri, S.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Vahidinasab, V. A New False Data Injection Attack Detection Model for Cyberattack Resilient Energy Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2022, 19, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z. Application of EOS-ELM With Binary Jaya-Based Feature Selection to Real-Time Transient Stability Assessment Using PMU Data. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 23092–23101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Sadighian, A.; Tanveer, A.; Al-Naimi, S.J.; Oligeri, G. A survey on detection and localisation of false data injection attacks in smart grids. IET Cyber-Physical Syst. Theory Appl. 2024, 9, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, L. , et al. A false data injection attack method for generator dynamic state estimation. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society 2019, 34, 3651–3660. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Sankar, L.; Kosut, O. Vulnerability Analysis and Consequences of False Data Injection Attack on Power System State Estimation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2015, 31, 3864–3872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Q. , et al. A review of network attacks and defenses in cyber-physical power systems: Part II—Detection and Protection. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2019, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Xue, A.; Chang, N. , et al. Current research status and prospects of network attacks and defenses in power system automatic generation control. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2021, 45, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.D.; Liu, N. False data injection attacks and their detection methods for interactive demand response. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2021, 45, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Li, Z. Dummy Data Attacks in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 11, 1792–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Qi, J.; Chen, L. Robust Cubature Kalman Filter for Dynamic State Estimation of Synchronous Machines Under Unknown Measurement Noise Statistics. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 29139–29148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, S.A.; Safdar, R.; Ali, S.T. False data injection attacks on networked control systems. Journal of Control and Decision 2024, 11, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadsar, M.; Abazari, A.; Ameli, A.; Yan, J.; Ghafouri, M. Prevention and Detection of Coordinated False Data Injection Attacks on Integrated Power and Gas Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 38, 4252–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Yang, Z.; Li, G. Coordinating Flexible Demand Response and Renewable Uncertainties for Scheduling of Community Integrated Energy Systems with an Electric Vehicle Charging Station: A Bi-level Approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Hao, G.; Wang, Y. Gaussian Mixture Model Uncertainty Modeling for Power Systems Considering Mutual Assistance of Latent Variables. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2024, PP, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bu, F.; Li, Y. , et al. Optimal scheduling of island integrated energy systems considering multi-uncertainties and hydrothermal simultaneous transmission: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Applied Energy 2023, 333, 120540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y. Collaborative optimization of multi-microgrids system with shared energy storage based on multi-agent stochastic game and reinforcement learning. Energy 2023, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Mugemanyi, S.; Yu, T.; Bo, X.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Rugema, F.X.; Bananeza, C. Dynamic exploitation Gaussian bare-bones bat algorithm for optimal reactive power dispatch to improve the safety and stability of power system. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 1401–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Chen, C.; Li, Y.; Tian, Y. Corrections to “Nonintrusive Appliance Identification With Appliance-Specific Networks” [Jul/Aug 20 3443-3452]. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 5678–5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, F.; Ji, P.; Ke, W.; Wan, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Yuan, Q. Image encryption for offshore wind power based on 2D-LCLM and Zhou Yi eight trigrams. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 2023, 22, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Cai, J. , et al. SCKF-LSTM Based Trajectory Tracking for Electricity-Gas Integrated Energy System. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.18357. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, G.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Guang, K.; Zeng, Z. Safe Reinforcement Learning for Active Distribution Networks Reconfiguration Considering Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, PP, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Multi-microgrid optimization operation strategy considering nonlinear conditions and renewable energy uncertainty: A data-driven method. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, PP, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musleh, A.S.; Chen, G.; Dong, Z.Y. A survey on the detection algorithms for false data injection attacks in smart grids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 11, 2218–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X.; Qu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, M. Review of active defense methods against power CPS false data injection attacks from the multiple spatiotemporal perspective. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11235–11248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmeeda, S.; Bhagyashree, B.K. Detection and Prevention of False Data Injection Attack in Cyber Physical Power System. 2021 IEEE International Conference on Mobile Networks and Wireless Communications (ICMNWC); IEEE, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y. , et al. Critical link identification of power system vulnerability based on modified graph attention network. Power System Protection and Control 2024, 52, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, P.; Reiter, M.K. False data injection attacks against state estimation in electric power grids. In Proceedings of the 16th of ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Chicago, IL, USA, 9–13 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liang, G.; Cai, Z.; Hu, C.; Xu, Y.; Luo, F.; Zhao, J. Impact analysis of false data injection attacks on power system static security assessment. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2016, 4, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ru, Y.; Liu, J. , et al. Detection of false data injection attacks in automatic generation control systems based on ensemble filtering. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2022, 46, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, S.; Govindarasu, M. Model-Based Attack Detection and Mitigation for Automatic Generation Control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, M.; Youssef, A.; El-Saadany, E. Joint Detection and Mitigation of False Data Injection Attacks in AGC Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 4985–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.D.; Debbarma, S. Detection and mitigation of cyber-attacks on AGC systems of low inertia power grid. IEEE Systems Journal 2019, 14, 2023–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.D.; Debbarma, S. A novel OC-SVM based ensemble learning framework for attack detection in AGC loop of power systems. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 202, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X. Evaluation of Reinforcement Learning-Based False Data Injection Attack to Automatic Voltage Control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 2158–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, K.; Zhu, L.; Qian, M. Novel Detection Scheme Design Considering Cyber Attacks on Load Frequency Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2017, 14, 1932–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.W.; Joo, I.Y.; Choi, D.H. False data injection attacks on contingency analysis: Attack strategies and impact assessment. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 8841–8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Chow, M.Y. Resilient Collaborative Distributed AC Optimal Power Flow Against False Data Injection Attacks: A Theoretical Framework. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2021, 13, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Bo, X.; Yu, T.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kan, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Active and passive hybrid detection method for power CPS false data injection attacks with improved AKF and GRU-CNN. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 1490–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, S.; Turuk, A.K. Design of False Data Injection Attacks in Cyber-Physical Systems. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, J.; Xue, K.; Cui, M. Power Cyber-Physical System Risk Area Prediction Using Dependent Markov Chain and Improved Grey Wolf Optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 82844–82854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, B. Global state estimation for whole transmission and distribution networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2005, 74, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, X.; Lin, J.; et al. On false data injection attacks against the dynamic microgrid partition in the smart grid. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC); IEEE, 2015; pp. 7222–7227. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, Z. , et al. False data injection attack methods for state estimation of unbalanced three-phase distribution networks. High Voltage Engineering 2021, 47, 2367–2377. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, Z.; Kou, L.; Li, Y.; Cao, M.; Ma, F. Data encryption based on a 9D complex chaotic system with quaternion for smart grid. Chin. Phys. B 2023, 32, 010502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Mo, Y.; Sinopoli, B. Integrity Data Attacks in Power Market Operations. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2011, 2, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Badrinath Krishna, V.; Yau DK, Y.; et al. , Impact of integrity attacks on real-time pricing in smart grids. In Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC conference on Computer & communications security; 2013; pp. 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, J.; Cardenas, A.; Quijano, N. Integrity Attacks on Real-Time Pricing in Smart Grids: Impact and Countermeasures. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 8, 2249–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, S.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gjessing, S.; Basar, T. Dependable Demand Response Management in the Smart Grid: A Stackelberg Game Approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Ge, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z. Transmission Line Rating Attack in Two-Settlement Electricity Markets. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 7, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Mo, Y.; Sinopoli, B. False data injection attacks in electricity markets. 2010 First IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications; IEEE, 2010; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Margossian, H.; Sayed, M.A.; Fawaz, W.; Nakad, Z. Partial grid false data injection attacks against state estimation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 110, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaojun, G.; Jirutitijaroen, P.; Motani, M. Detecting False Data Injection Attacks in AC State Estimation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 6, 2476–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Thomas, R.J.; Tong, L. On the nonlinearity effects on malicious data attack on power system. 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting; IEEE, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Li, Z. False Data Attacks Against AC State Estimation With Incomplete Network Information. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 2239–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, G.; Giampapa, J.A. Vulnerability Assessment of AC State Estimation With Respect to False Data Injection Cyber-Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2012, 3, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Wang, X.; Dong, Z. , et al. False data attack strategies based on the Lagrange multiplier method. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2017, 41, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- James, J.Q.; Hou, Y.; Li VO, K. Online false data injection attack detection with wavelet transform and deep neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2018, 14, 3271–3280. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Chen, G.; Yang, D. Local False Data Injection Attack Theory Considering Isolation Physical-Protection in Power Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 103285–103290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Mohsenian-Rad, H. False data injection attacks with incomplete information against smart power grids. 2012 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM); IEEE, 2012; pp. 3153–3158. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, R.; Xun, G.; Liu, X.; Yan, G. A New AC False Data Injection Attack Method Without Network Information. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5280–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian J, Wang B, Shang F. False data injection attacks in smart grids based on robust principal component analysis. Journal of Computer Applications 2017, 37, 1943–1947. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Qiu, R.; Zeng, J. Blind online false data injection attacks in smart grids based on kernel principal component analysis. Power System Technology 2018, 42, 2270–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; He, X.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, R.C.; Ai, Q. Blind False Data Injection Attacks Against State Estimation Based on Matrix Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3174–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, Z.; Ren, K. Modeling Load Redistribution Attacks in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2011, 2, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, Z.; Ren, K. Quantitative Analysis of Load Redistribution Attacks in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2012, 23, 1731–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Z. Local Load Redistribution Attacks in Power Systems With Incomplete Network Information. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, D.; et al. Coordinated attacks against power grids: Load redistribution attack coordinating with generator and line attacks. 2015 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting; IEEE, 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Tong, L. On Topology Attack of a Smart Grid: Undetectable Attacks and Countermeasures. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2013, 31, 1294–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Z. Local Topology Attacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 8, 2617–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Weller, S.R.; Zhao, J.; Luo, F.; Dong, Z.Y. A Framework for Cyber-Topology Attacks: Line-Switching and New Attack Scenarios. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 10, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Xiahou, K.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.H. Real-Time Detection of Cyber-Physical False Data Injection Attacks on Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2020, 17, 6810–6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Impact of cyber attacks on SCADA systems on the reliability of power systems. Power System Protection and Control 2018, 46, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xiang, Y. Power System Reliability Analysis With Intrusion Tolerance in SCADA Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 7, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risbud, P.; Gatsis, N.; Taha, A. Vulnerability Analysis of Smart Grids to GPS Spoofing. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 3535–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Nagananda, K.; Venkitasubramaniam, P.; et al. GPS spoofing attack characterization and detection in smart grids. 2016 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS); IEEE, 2016; pp. 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, S.; Pignati, M.; Dan, G.; Le Boudec, J.-Y.; Paolone, M. Undetectable Timing-Attack on Linear State-Estimation by Using Rank-1 Approximation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 9, 3530–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyaci, O.; Narimani, M.R.; Davis, K.R.; Ismail, M.; Overbye, T.J.; Serpedin, E. Joint Detection and Localization of Stealth False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids Using Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 13, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Qi, D.; Li, Z. , et al. Distributed cooperative control of microgrids under false data injection attacks. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2021, 45, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, G.; La Scala, M.; Dong, Z.Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, J. Short-Term State Forecasting-Aided Method for Detection of Smart Grid General False Data Injection Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 8, 1580–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, K.; Cao, X.; Hu, F.; et al. Detection of faults and attacks including false data injection attack in smart grid using Kalman filter. IEEE transactions on control of network systems 2014, 1, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Zhao, J.; Luo, F.; Weller, S.R.; Dong, Z.Y. A Review of False Data Injection Attacks Against Modern Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 8, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X.; Qu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, M. Review of active defense methods against power CPS false data injection attacks from the multiple spatiotemporal perspective. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11235–11248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musleh, A.S.; Chen, G.; Dong, Z. A survey on the detection algorithms for false data injection attacks in smart grids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 11, 2218–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Abur, A. A Massively Parallel Framework for Very Large Scale Linear State Estimation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 33, 4407–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhchoukh, Y.; Ishii, H. Enhancing Robustness to Cyber-Attacks in Power Systems Through Multiple Least Trimmed Squares State Estimations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 4395–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Trinkle, M.; Dimitrovski, A.D.; Bin Song, J.; Li, H. A Cross-Layer Defense Mechanism Against GPS Spoofing Attacks on PMUs in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 6, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zeng, W.; Chow, M.-Y. Resilient Distributed DC Optimal Power Flow Against Data Integrity Attack. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 9, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Gu, W.; Lou, G.; Sheng, W.; Liu, K. Distributed synchronous detection for false data injection attack in cyber-physical microgrids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Pang, Z.; Wen, H.; Hou, W.; Han, W. FDI Attack Detection at the Edge of Smart Grids Based on Classification of Predicted Residuals. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2022, 18, 9302–9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukicheva, I.; Pozo, D.; Kulikov, A. Cyberattack detection in intelligent grids using non-linear filtering. 2018 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT-Europe); IEEE, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Liu, F.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X. Evaluation of Reinforcement Learning-Based False Data Injection Attack to Automatic Voltage Control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 2158–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, K.; Cao, X.; Hu, F.; Liu, Y. Detection of Faults and Attacks Including False Data Injection Attack in Smart Grid Using Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Control. Netw. Syst. 2014, 1, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, M.N.; Yılmaz, Y.; Wang, X. Real-time detection of hybrid and stealthy cyber-attacks in smart grid. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2018, 14, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhchoukh, Y.; Lei, H.; Johnson, B.K. Diagnosis of Outliers and Cyber Attacks in Dynamic PMU-Based Power State Estimation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 35, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Du, D.; Fei, M. A Novel Dynamic Watermarking-Based EKF Detection Method for FDIAs in Smart Grid. Ieee/caa J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 1319–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Bo, X.; Yu, T.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Kan, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Active and passive hybrid detection method for power CPS false data injection attacks with improved AKF and GRU-CNN. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2022, 16, 1490–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drayer, E.; Routtenberg, T. Detection of False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids Based on Graph Signal Processing. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 14, 1886–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, A.; Rahnamay-Naeini, M. A Graph Signal Processing Framework for Detecting and Locating Cyber and Physical Stresses in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3688–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslemi, R.; Mesbahi, A.; Velni, J.M. A Fast, Decentralized Covariance Selection-Based Approach to Detect Cyber Attacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 9, 4930–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyaci, O.; Umunnakwe, A.; Sahu, A.; Narimani, M.R.; Ismail, M.; Davis, K.R.; Serpedin, E. Graph Neural Networks Based Detection of Stealth False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids. IEEE Syst. J. 2021, 16, 2946–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorjani, M.; Seifi, H.; Varjani, A.Y. A Graph Theory-Based Approach to Detect False Data Injection Attacks in Power System AC State Estimation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2020, 17, 2465–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, S.; Sikdar, B. Detection of Malicious Command Injection Attacks on Phase Shifter Control in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hedman, K.W. Enhancing Power System Cyber-Security With Systematic Two-Stage Detection Strategy. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 1549–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, A.; Hooshyar, A.; El-Saadany, E.F. Development of a Cyber-Resilient Line Current Differential Relay. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2018, 15, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Sikdar, B.; Chow, J.H. Classification and Detection of PMU Data Manipulation Attacks Using Transmission Line Parameters. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 9, 5057–5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.; Mahmood, A.N.; Tari, Z. Identification of vulnerable node clusters against false data injection attack in an AMI based Smart Grid. Inf. Syst. 2015, 53, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Ghiasi, M.; Niknam, T.; Kavousi-Fard, A.; Tajik, E.; Padmanaban, S.; Aliev, H. Cyber Attack Detection Based on Wavelet Singular Entropy in AC Smart Islands: False Data Injection Attack. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 16488–16507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xiang, Z.; Deng, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z. False Data Injection Attacks Detection in Smart Grid: A Structural Sparse Matrix Separation Method. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 2545–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Li, H.; Campbell, K.A.; Han, Z. Real-Time Detection of False Data Injection in Smart Grid Networks: An Adaptive CUSUM Method and Analysis. IEEE Syst. J. 2014, 10, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Z.; Liu, W.X.; Li, C.Z. , et al. A review of FDIA detection methods for power SCADA systems. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering 2023, 43, 8602–8622. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, C.; Wu, D.; Yue, D.; Jin, B.; Xu, S. A hybrid method for false data injection attack detection in smart grid based on variational mode decomposition and OS-ELM. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 8, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, U.; Morris, T.H.; Pan, S. Applying Non-Nested Generalized Exemplars Classification for Cyber-Power Event and Intrusion Detection. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 9, 3928–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh-Zanjani, M.; Hallaji, E.; Razavi-Far, R.; Saif, M.; Parvania, M. Adversarial Semi-Supervised Learning for Diagnosing Faults and Attacks in Power Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 3468–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, S.A.; Salmasi, F.R. Detection of false data injection attacks against state estimation in smart grids based on a mixture Gaussian distribution learning method. IET Cyber-Physical Syst. Theory Appl. 2017, 2, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-T.; Chen, G.; Huang, Y. Incentive edge-based federated learning for false data injection attack detection on power grid state estimation: A novel mechanism design approach. Appl. Energy 2022, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Feng, H.; Li, K.; Zhao, Q. False data injection attacks detection with modified temporal multi-graph convolutional network in smart grids. Comput. Secur. 2022, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, H.T.; Anwar, A.; Mahmood, A.; Chilamkurti, N. Data-driven Approach for State Prediction and Detection of False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grid. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2023, 11, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bi, S.; Zhang, Y.-J.A. Locational Detection of the False Data Injection Attack in a Smart Grid: A Multilabel Classification Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 8218–8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xue, W.; Wang, H.; Chung, C.Y.; Wang, G.; Peng, J.; Yang, Q. Extreme Learning Machine-Based State Reconstruction for Automatic Attack Filtering in Cyber Physical Power System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2020, 17, 1892–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudell, T.R.; Nabavi, S.; Chakrabortty, A. A Real-Time Attack Localization Algorithm for Large Power System Networks Using Graph-Theoretic Techniques. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 6, 2551–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D. A novel strategy for locational detection of false data injection attack. Sustain. Energy, Grids Networks 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Developing graphical detection techniques for maintaining state estimation integrity against false data injection attack in integrated electric cyber-physical system. 2019, 105, 101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikarjunaswamy, S.; Sharmila, N.; Siddesh, G.K.; et al. A Novel Architecture for Cluster Based False Data Injection Attack Detection and Location Identification in Smart Grid. Advances in Thermofluids and Renewable Energy: Select Proceedings of TFRE 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 599–611. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Qin, Z.; Xie, M.; Liu, H.; Meng, L. Defense of Massive False Data Injection Attack via Sparse Attack Points Considering Uncertain Topological Changes. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Song Sr, H.D.; Zhang Sr, T.; et al. Research on location detection method of power network false data injection based on FCN-GRU. 2nd International Conference on Mechanical, Electronics, and Electrical and Automation Control (METMS 2022); SPIE, 2022; pp. 12244, 1242-1247. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Guan, X. Interval Observer-Based Detection and Localization Against False Data Injection Attack in Smart Grids. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Li Z, Li Z. Optimal protection strategy against false data injection attacks in power systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 8, 1802–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Piechocki, R.J.; Kaleshi, D.; Chin, W.H.; Fan, Z. Sparse Malicious False Data Injection Attacks and Defense Mechanisms in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2015, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, N.; Wang, Q.; Yan, L.; Tang, Y.; Xu, J. A multi-stage game model for the false data injection attack from attacker’s perspective. Sustain. Energy, Grids Networks 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, X.; Pahwa, A.; Wu, H. Voltage Stability Constrained Moving Target Defense Against Net Load Redistribution Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3748–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, H. Optimal D-FACTS Placement in Moving Target Defense Against False Data Injection Attacks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4345–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S. Online Generative Adversary Network Based Measurement Recovery in False Data Injection Attacks: A Cyber-Physical Approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2019, 16, 2031–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Z. Research on online defense against stealthy malicious data injection attacks in smart grids. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering 2020, 40, 2546–2559. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Xiahou, K.; Li, M. Research on a data-driven framework for defending against false data injection attacks in power systems. Electric Measurement & Instrumentation 2024, 61, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).