Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Purification of Microorganisms

2.2. Morphological Identification

2.3. Molecular Identification Through DNA Sequencing

2.4. Ex Vivo Fungal Activity

2.5. In Vitro Antifungal Activity with Essential Oils

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification

3.2. Molecular Identification Through DNA Sequencing

3.3. Fungal Activity Ex Vivo

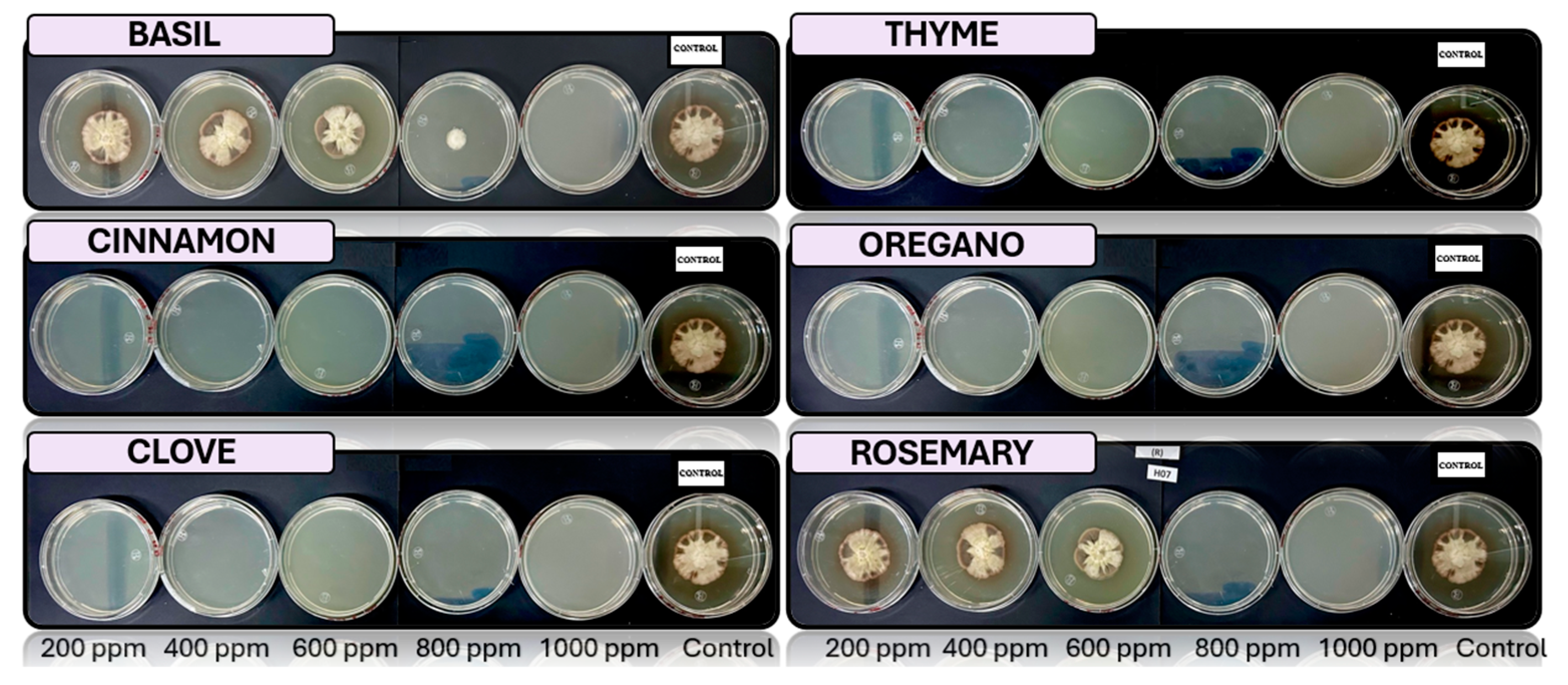

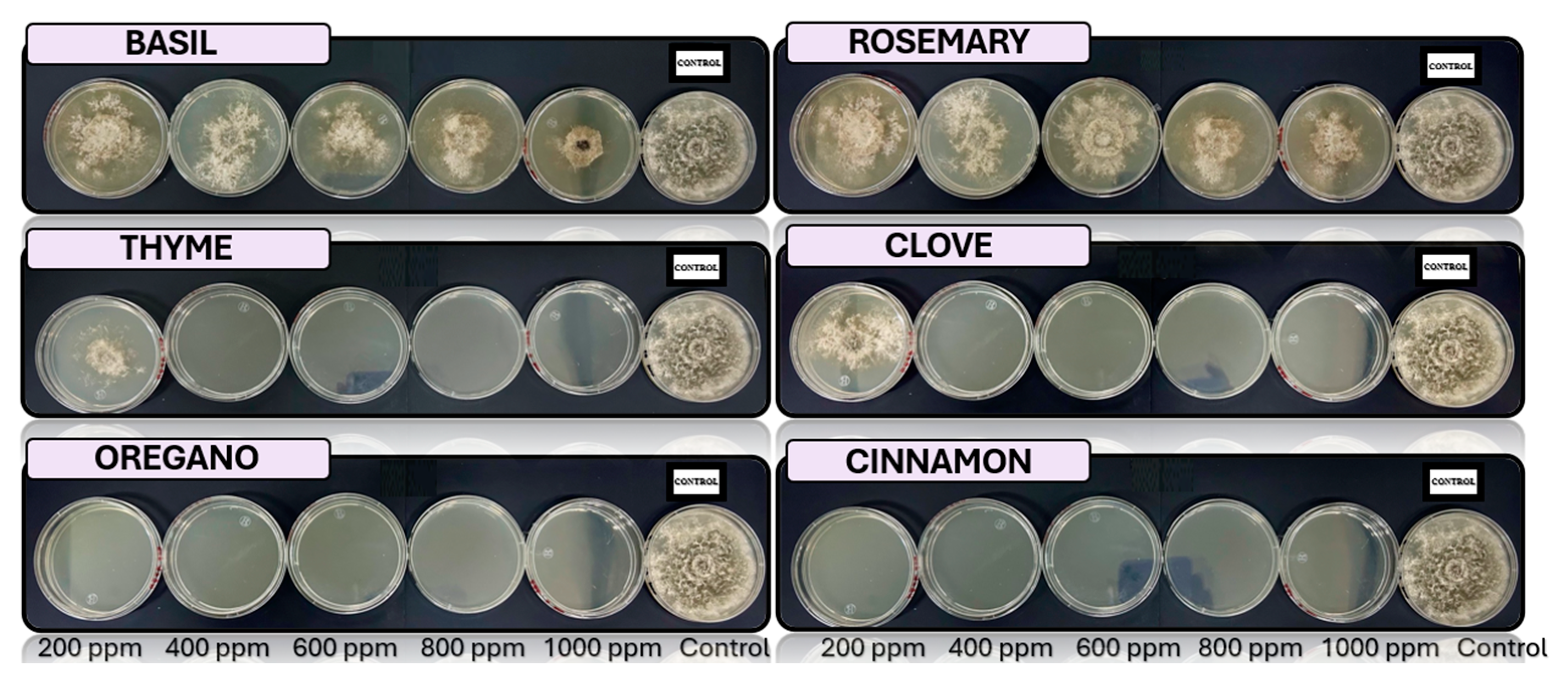

3.4. In Vitro Antifungal Activity with Essential Oils

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological identification

4.2. Molecular Identification Through DNA Sequencing

4.3. Ex Vivo Fungal Activity

4.4. In Vitro Antifungal Activity with Essential Oils

| Essential oil | Fungus | Concentration [ppm] | ||||

| 200 | 400 | 600 | 800 | 1000 | ||

| Cinnamon | Fusarium pseudocircinatum | + | + | - | - | - |

| Colletotrichum tengchongense | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium verticilloides | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusariumnapiforme | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Verticillium dahliae | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Clove | Fusarium pseudocircinatum | + | + | + | + | + |

| Colletotrichum tengchongense | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium verticilloides | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Fusariumnapiforme | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Verticillium dahliae | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Basil | Fusarium pseudocircinatum | + | + | + | + | + |

| Colletotrichum tengchongense | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Fusarium verticilloides | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Fusariumnapiforme | + | + | + | + | - | |

| Verticillium dahliae | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Oregano | Fusarium pseudocircinatum | + | - | - | - | - |

| Colletotrichum tengchongense | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium verticilloides | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusariumnapiforme | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Verticillium dahliae | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Rosemary | Fusarium pseudocircinatum | + | + | + | + | + |

| Colletotrichum tengchongense | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Fusarium verticilloides | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Fusariumnapiforme | + | + | + | - | - | |

| Verticillium dahliae | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Thyme | Fusarium pseudocircinatum | + | + | + | + | - |

| Colletotrichum tengchongense | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium verticilloides | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Fusariumnapiforme | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Verticillium dahlia | + | - | - | - | - | |

5. Conclusions

Autor Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang Q, Liu D, Zhang J. Post-harvest control of fungal diseases in bananas using essential oils. Journal of Postharvest Biology 2019, 45, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2019.05.002.

- Mata Anchundia D, Suatunce Cunuhay P, Poveda Morán R. Análisis económico del banano orgánico y convencional en la provincia Los Ríos, Ecuador. Avances 2021, 23, 419–430.

- Borges CV, Amorim EP, Leonel M, Gomez 0Gomez HA, Santos TPR dos, Ledo CA da S, et al. Post-harvest physicochemical profile and bioactive compounds of 19 bananas and plantains genotypes. Bragantia 2018, 78, 284–296.

- Ruiz Medina MD, Ruales J. Postharvest Alternatives in Banana Cultivation. 2024. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202402.0783.v1.

- Aguilar-Anccota R, Arévalo-Quinde CG, Morales-Pizarro A, Galecio-Julca M, Aguilar-Anccota R, Arévalo-Quinde CG, et al. Hongos asociados a la necrosis de haces vasculares en el cultivo de banano orgánico: síntomas, aislamiento e identificación, y alternativas de manejo integrado. Scientia Agropecuaria 2021, 12, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.17268/sci.agropecu.2021.028.

- Capa Benítez LB, Alaña Castillo TP, Benítez Narváez RM. Importancia de la producción de banano orgánico. Caso: Provincia de El Oro, Ecuador. Revista Universidad y Sociedad 2016, 8, 64–71.

- Agronomía C. Tecnología Poscosecha. Agronomía Costarricense 2005, 29, 207–209.

- Mari M, Torres R, Vanneste JL. Biological control of postharvest diseases: Opportunities and challenges. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00688.

- Villa-Martínez A, Pérez-Leal R, Morales-Morales HA, Basurto-Sotelo M, Soto-Parra JM, Martínez-Escudero E. Situación actual en el control de Fusarium spp. y evaluación de la actividad antifúngica de extractos vegetales. Acta Agronómica 2015, 64, 194–205. https://doi.org/10.15446/acag.v64n2.43358.

- Goicoechea N. To what extent are soil amendments useful to control Verticillium wilt? Pest Management Science 2009, 65, 831–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.1774.

- Pabon Montoya B, Córdova Chávez M, Alban Alcivar J, Jaramillo Robles A. Efectos antifúngicos de extractos botánicos sobre el crecimiento micelial de Colletotrichum sp. a nivel in vitro, causante de antracnosis en la fruta de aguacate. 593 Digital Publisher CEIT 2024, 9, 869–879.

- Alzate D, Mier G, Afanador L, Durango D, García C. Evaluación de la fitotoxicidad y la actividad antifúngica contra Colletotrichum acutatum de los aceites esenciales de tomillo (Thymus vulgaris), limoncillo (Cymbopogon citratus), y sus componentes mayoritarios 2009, 16.

- Bandoni AL, Retta D, Lira PMDL, Baren CM van. ¿Son realmente útiles los aceites esenciales? Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 2009, 8, 317–322.

- Oliva M de LM, Lorello IM, Baglio C, Posadaz A, Carezzano ME, Paletti Rovey MF, et al. Chemical composition, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus Spenn.) essential oils from Argentina 2023.

- Pilozo G, Villavicencio-Vásquez M, Chóez-Guaranda I, Murillo DV, Pasaguay CD, Reyes CT, et al. Chemical, antioxidant, and antifungal analysis of oregano and thyme essential oils from Ecuador: Effect of thyme against Lasiodiplodia theobromae and its application in banana rot. Heliyon 2024, 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31443.

- Flores-Villa E, Sáenz-Galindo A, Castañeda-Facio AO, Narro-Céspedes RI, Flores-Villa E, Sáenz-Galindo A, et al. Romero (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): su origen, importancia y generalidades de sus metabolitos secundarios. TIP Revista especializada en ciencias químico-biológicas 2020, 23. https://doi.org/10.22201/fesz.23958723e.2020.0.266.

- Farias APP, Monteiro O dos S, da Silva JKR, Figueiredo PLB, Rodrigues AAC, Monteiro IN, et al. Chemical composition and biological activities of two chemotype-oils from Cinnamomum verum J. Presl growing in North Brazil. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 57, 3176–3183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-020-04288-7.

- Pinto E, Silva C, Costa L. Eugenol as an antifungal agent: Mechanisms and applications. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2018, 124, 1089–1099. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13748.

- Abadias M, Teixidó N, Usall J, Viñas I. Evaluation of alternative strategies to control postharvest blue mould of apple caused by Penicillium expansum. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2008, 122, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.11.048.

- Haro-González JN, Castillo-Herrera GA, Martínez-Velázquez M, Espinosa-Andrews H. Clove Essential Oil (Syzygium aromaticum L. Myrtaceae): Extraction, Chemical Composition, Food Applications, and Essential Bioactivity for Human Health. Molecules 2021, 26, 6387. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26216387.

- Boulanger R, Liu Y, Jiang Z. Synergistic effects of essential oils against fungal pathogens: Mechanisms and applications. Food Control 2021, 123, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.107118.

- Kintzios SE. 21 - Oregano. In: Peter KV, editor. Handbook of Herbs and Spices (Second Edition), Woodhead Publishing; 2012, p. 417–36. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857095688.417.

- Choi YH, Kim H, Lee S. The antifungal activity of essential oils: Mechanisms and applications in plant disease management. Phytopathology Research 2018, 44, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42055-018-0032-2.

- Arcila-Lozano CC, Loarca-Piña G, Lecona-Uribe S, González de Mejía E. El orégano: propiedades, composición y actividad biológica de sus componentes. Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutrición 2004, 54, 100–111.

- Prashar A, Locke IC, Evans CS. Cytotoxicity of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) oil and its major components to human skin cells. Cell Proliferation 2006, 39, 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00384.x.

- Selles SMA, Kouidri M, Belhamiti BT, Ait Amrane A. Chemical composition, in-vitro antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil. Food Measure 2020, 14, 2352–2358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-020-00482-5.

- Ruiz M, Ávila J, Ruales J. Diseño de un recubrimiento comestible bioactivo para aplicarlo en la frutilla (Fragaria vesca) como proceso de postcosecha 2016, 17, 276–287.

- Aquino-Martínez JG, Vázquez-García LM, Reyes-Reyes BG. Biocontrol in vitro e in vivo de Fusarium oxysporum Schlecht. f. sp. dianthi (Prill. y Delacr.) Snyder y Hans. con Hongos Antagonistas Nativos de la Zona Florícola de Villa Guerrero, Estado de México. Revista mexicana de fitopatología 2008, 26, 127–137.

- Barrera Necha LL, García Barrera LJ. Actividad antifúngica de aceites esenciales y sus compuestos sobre el crecimiento de Fusarium sp. aislado de papaya ( Carica papaya). Revista Científica UDO Agrícola 2008, 8, 33–41.

- Ultee A, Bennik MHJ, Moezelaar R. The phenolic hydroxyl group of carvacrol is essential for action against the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2002, 68, 1561–1568. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.68.4.1561-1568.2002.

- Pina-Vaz C, Gonçalves Rodrigues A, Pinto E, Costa-de-Oliveira S, Tavares C, Salgueiro L, et al. Antifungal activity of Thymus oils and their major compounds. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2004, 18, 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00886.x.

- Shahrajabian MH, Sun W, Cheng Q. Chemical components and pharmacological benefits of Basil (Ocimum basilicum): a review. International Journal of Food Properties 2020, 23, 1961–1970. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2020.1828456.

- Zhao S, Zhang Z, Wei Y. Mechanisms of antifungal action of cinnamaldehyde. Phytochemistry 2020, 173, 112112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112112.

- Salazar E, Hernández R, Tapia A, Gómez-Alpízar L. Identificación molecular del hongo Colletotrichum spp., aislado de banano (Musa spp) de la altura en la zona de Turrialba y determinación de su sensibilidad a fungicidas poscosecha. Agronomía Costarricense 2012, 36, 53–68.

- Tortora GJ, Funke BR, Case CL. Introducción a la microbiología. Ed. Médica Panamericana; 2007.

- Agu K, Awah N, Nnadozie A. Isolation, identification, and pathogenicity of fungi associated with cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta) spoilage. Food Science and Technology 2016.

- Suárez L, Rangel A. Aislamiento de microorganismos para control biológico de Moniliophthora roreri 2013, 62.

- Orwa P, Mugambi G, Wekesa V, Mwirichia R. Isolation of haloalkaliphilic fungi from Lake Magadi in Kenya. Heliyon 2020.

- Vilaplana R, Pazmiño L, Valencia-Chamorro S. Control of anthracnose, caused by Colletotrichum musae, on postharvest organic banana by thyme oil. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2018, 138, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2017.12.008.

- Morales R, Henríquez G. Aislamiento e identificación del moho causante de antracnosis en Musa paradisiaca l. (plátano) en cooperativa san carlos, el salvador y aislamiento de mohos y levaduras con capacidad antagonista. Crea Ciencia Revista Científica 2021, 13, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.5377/creaciencia.v13i2.11825.

- Funnell-Harris D, Prom L. Isolation and characterization of grain mold fungi Cochliobolus and Alternaria spp. from sorghum using semiselective media and DNA sequence analyses. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 2013.

- Vargas-Fernández JP, Wang-Wong A, Muñoz-Fonseca M, Vargas-Fernández JP, Wang-Wong A, Muñoz-Fonseca M. Microorganismos asociados a la enfermedad conocida como pudrición suave del fruto de banano (Musa sp.) y alternativas de control microbiológicas y químicas a nivel in vitro *. Agronomía Costarricense 2022, 46, 61–76. https://doi.org/10.15517/rac.v46i2.52046.

- Ruiz-Medina M, Ruales J. Essential Oils as an Antifungal Alternative to Control Fusarium spp., Penicillium spp., Trichoderma spp. and Aspergillus spp. 2024. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202408.1987.v1.

- Vanegas J Santamaría, González N Comba, Mancilla XC Pérez. Manual de Microbiología General: Principios Básicos de Laboratorio. Editorial Tadeo Lozano; 2014.

- Lopes J, Araújo G, Almeida M. Storage methods of fungi for long-term research. Mycological Studies 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycos.2021.06.001.

- Siller-Ruiz M, Hernández-Egido S, Sánchez-Juanes F, González-Buitrago JM, Muñoz-Bellido JL. Métodos rápidos de identificación de bacterias y hongos. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 2017, 35, 303–313.

- Acurio Vásconez RD, España Imbaquingo CK, Acurio Vásconez RD, España Imbaquingo CK. Aislamiento, caracterización y evaluación de Trichoderma spp. como promotor de crecimiento vegetal en pasturas de Raygrass (Lolium perenne) y trébol blanco (Trifolium repens). LA GRANJA Revista de Ciencias de la Vida 2017, 25, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.17163/lgr.n25.2017.05.

- Carpio-Coba CF, Noboa-Silva VF, Salazar-Castañeda EP, Lema-Saigua ER. Caracterización macroscópica y microscópica de cuatro especies forestales de la amazonia del sur de Ecuador. Polo del Conocimiento 2021, 6, 886–904. https://doi.org/10.23857/pc.v6i8.2986.

- Bellemain E, Carlsen T, Brochmann C, Coissac E, Taberlet P, Kauserud H. ITS as an environmental DNA barcode for fungi: an in silico approach reveals potential PCR biases. BMC Microbiology 2010, 10, 189.

- Chacón-Cascante A, Crespi JM. Historical overview of the European Union banana import policy. Agronomía Costarricense 2006, 30, 111–127.

- Aguilar-Anccota R, Apaza-Apaza S, Maldonado E, Calle-Cheje Y, Rafael-Rutte R, Montalvo K, et al. Control in vitro e in vivo de Thielavipsis paradoxa y Collettrichum musae cn biofungicidas en frutos de banano orgánico. Manglar 2024, 21, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.57188/manglar.2024.006.

- Leslie JF, Summerell BA. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

- González A, others. Identification and characterization of Fusarium species from infected plants. Mycological Research 2013, 117, 189–197.

- Cai L, others. Identification of Colletotrichum species using molecular markers. Fungal Diversity 2011, 48, 25–35.

- Carrasco A, Sanfuentes E, Duran A, Valenzuela S. Cancro resinoso del pino: ¿una amenaza potencial para las plantaciones de Pinus radiata en Chile? Gayana Botánica 2016, 73, 369–380. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-66432016000200369.

- Marasas WFO, others. Fusarium verticilloides: Morphology and Mycotoxins. Mycological Research 2011, 115, 845–857.

- Inderbitzin P, others. Molecular and morphological characterization of Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Diversity 2011, 50, 105–118.

- Jayawardena R, others. Recent advances in molecular identification of Colletotrichum species. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 509–522.

- Rojo-Báez I, Álvarez-Rodríguez B, García-Estrada R, León-Félix J, Sañudo Barajas JA, Allende R. Situación actual de Colletotrichums spp. en México: Taxonomía, caracterización, patogénesis y control. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología, Mexican Journal of Phytopathology 2017, 35. https://doi.org/10.18781/R.MEX.FIT.1703-9.

- Wang Y, others. Molecular and morphological characterization of Colletotrichum tengchongense. Mycological Progress 2012, 11, 423–430.

- Zhang H, others. Molecular identification of Fusarium napiforme in diverse habitats. Fungal Ecology 2015, 17, 63–69.

- Jabnoun-Khiareddine H, Mahjoub M, Daami-Remadi M. Morphological Variability Within and Among Verticillium Species Collected in Tunisia. Tunisian Journal of Plant Protection 2010, 5, 19–38.

- Sharma RR, Singh D, Singh R. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables by microbial antagonists: A review. Biological Control 2009, 50, 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.05.001.

- Bautista-Baños S, Bosquez-Molina E, Barrera-Necha LL. The use of fungal antagonists to reduce postharvest fruit decay. Mycopathologia 2003, 155, 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022244032461.

- Fusarium verticilloides: Morphology and Mycotoxins. Mycological Research 2011, 115, 845–857.

- Ranasinghe L, Jayawardena B, Abeywickrama K. Fungicidal activity of essential oils of Cinnamomum zeylanicum (L.) and Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr et L.M. Perry against crown rot and anthracnose pathogens isolated from banana. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2002, 35, 208–211. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-765X.2002.01165.x.

- Burt S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2004, 94, 223–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.022.

|

|

| Organism | Fragment | % identity |

| Fusarium pseudocircinatum | ITS | 99.55 % |

| Fusarium napiforme | ITS | 98.92 % |

| Colletotrichum tengchongense | ITS | 99.58 % |

| Fusarium verticilloides | ITS | 99.11 % |

| Verticillium dahliae | ITS | 99.04 % |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).