Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

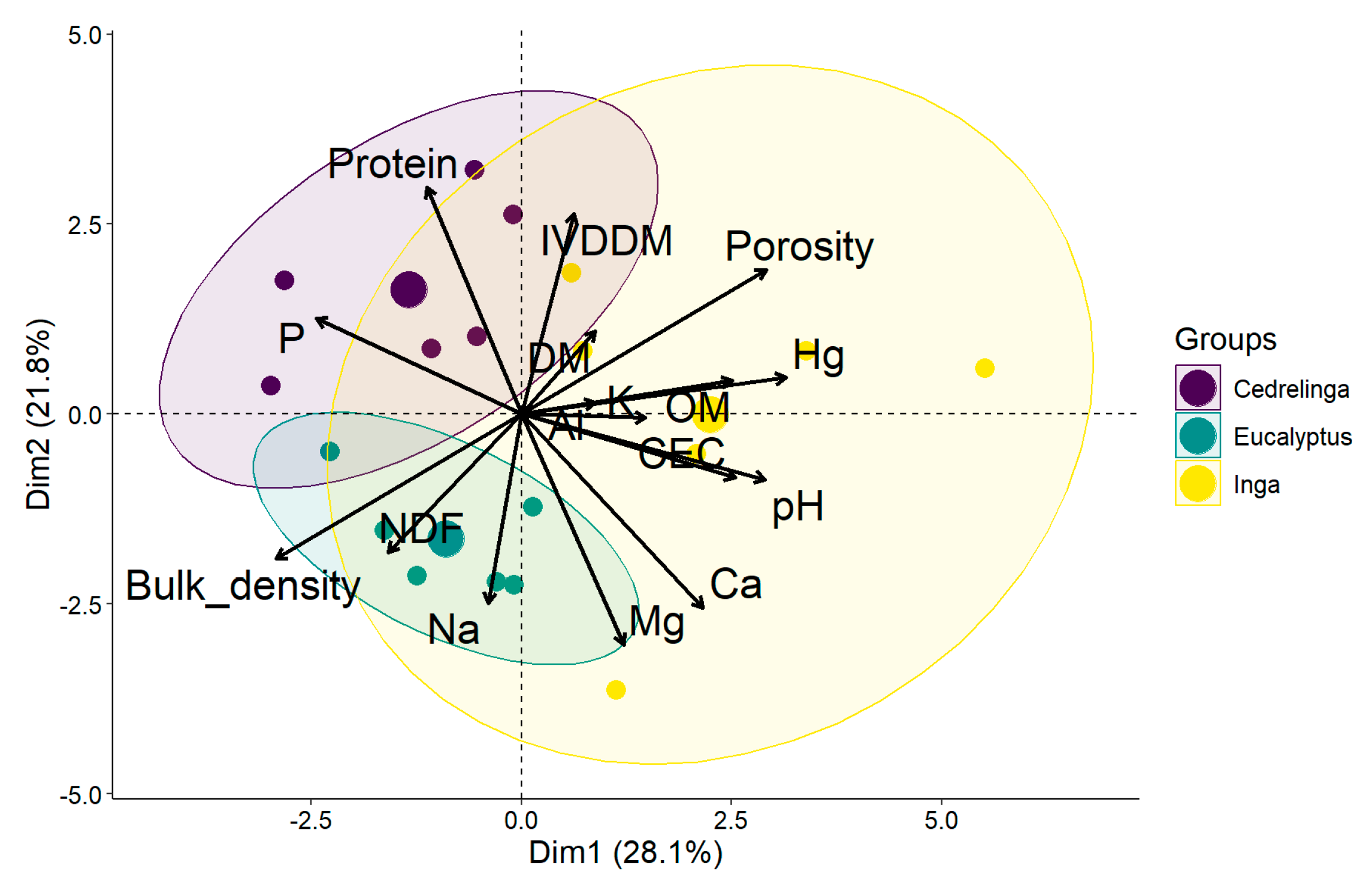

This study evaluated the effect of light conditions on the yield and nutritional value of Brachiaria decumbens (Brachiaria) in different silvopastoral systems (SPS) in the Peruvian Amazon, aiming to contribute to developing sustainable livestock systems. A 3 × 2 factorial design with three replications was used to compare three SPS with Inga edulis (guaba), Eucalyptus torrelliana (eucalyptus), and Cedrelinga cateniformis (tornillo) under shaded and open-field conditions. The results showed no significant interactions between the SPS and light conditions for most variables evaluated. However, forage availability per cut was higher in the guaba system under shade (1406 kg DM ha⁻¹). Protein content was significantly higher in the tornillo system (10.64%) and under shade (9.55%). eucalyptus increased neutral detergent fiber (69.72%), while metabolizable energy reached its highest in the guava system (8.09 MJ kg⁻¹ DM). Principal component analysis revealed that guaba improves soil moisture and cation exchange capacity; tornillo increases forage protein and soil phosphorus; and eucalyptus influences fiber and soil bulk density. Integrating Brachiaria into SPS with guaba under shade enhances forage production and soil structure, highlighting the potential of SPS for sustainable livestock in tropical regions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

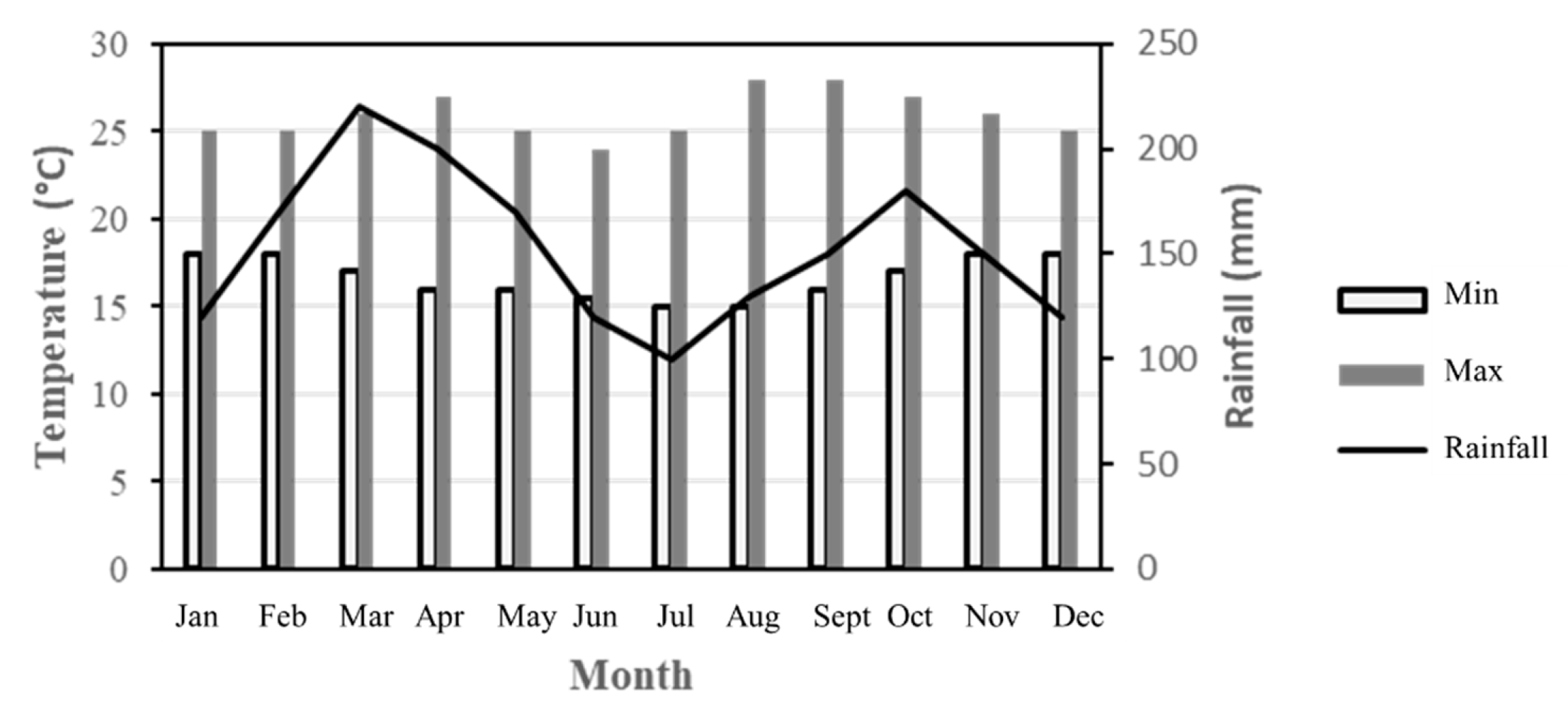

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Treatments and Sampling

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Forage Availability and Nutritional Quality

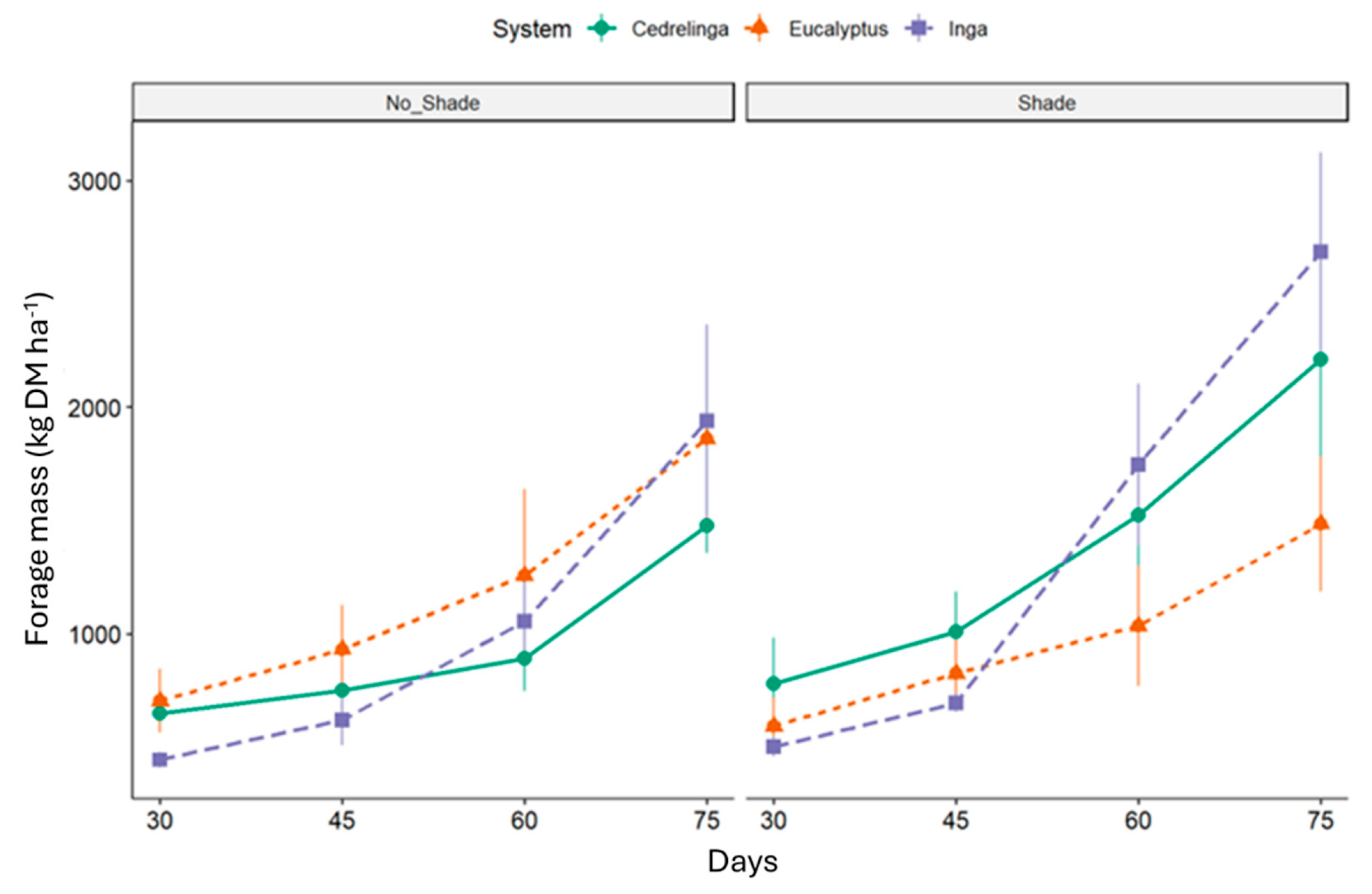

3.1.1. Forage mass

3.1.2. Nutritional Quality

3.1.3. Soil and Forage Correlations

3.2.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huertas, S.M.; Bobadilla, P.E.; Alcántara, I.; Akkermans, E.; van Eerdenburg, F.J.C.M. Benefits of Silvopastoral Systems for Keeping Beef Cattle. Animals 2021, 11, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes da Silva, I. A., Dubeux Jr, J. C. B., De Melo, A. C. L., Da Cunha, M. V., Dos Santos, M. V. F., Apolinário, V. X. O., & de Freitas, E. Tree legume enhances livestock performance in a silvopasture system. Agronomy Journal, 2021, 113(1), 358-369. [CrossRef]

- Lemes, A. P., Garcia, A. R., Pezzopane, J. R. M., Brandão, F. Z., Watanabe, Y. F., Cooke, R. F., ... & Gimenes, L. U. Silvopastoral system is an alternative to improve animal welfare and productive performance in meat production systems. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11(1), 14092. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, I. G., Auad, A. M., Veríssimo, B. A., & Silveira, L. C. P. Differences in the insect fauna associated to a monocultural pasture and a silvopasture in Southeastern Brazil. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1), 12112. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, R., Alegre, J., Pizarro, D. et al. Soil carbon stock potential in pastoral and silvopastoral systems in the Peruvian Amazon. Agroforest Systems, 2024, 98, 2157–2167. [CrossRef]

- Dagar, J. C., & Gupta, S. R. Silvopasture options for enhanced biological productivity of degraded pasture/grazing lands: an overview. Agroforestry for Degraded Landscapes: Recent Advances and Emerging Challenges, 2020, Vol. 2, 163-227. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E. F., Gómez, C., Pizarro, D., Alegre, J., Castillo, M. S., Vela, J., ... & Vásquez, H. (2023). Development of Silvopastoral Systems in the Peruvian Amazon. In Silvopastoral systems of Meso America and Northern South America (pp. 135-154). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Pizarro, D., Vásquez, H., Bernal, W. et al. Assessment of silvopasture systems in the northern Peruvian Amazon. Agroforest Syst 94, 173–183 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chará-Serna, A. M., & Chará, J. Efecto de los sistemas silvopastoriles sobre la biodiversidad y la provisión de servicios ecosistémicos en agropaisajes tropicales. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 2020, 32(11), 184.

- Haro-Castro, M. R. Efecto del componente arbóreo de un sistema silvopastoril sobre la distribución espacial de nutrientes móviles y la macrofauna del suelo en Tingo María. Universidad Agraria de la Selva. Tesis para optar el grado de Ingeniero de recursos naturales. Tingo Maria, Peru, 2022.

- Hernández, A. P., Bautista, I. B., Chávez, L. M., Ramírez, Á. E. C., & Mateo, A. B. Sistemas silvopastoriles para la producción de rumiantes en pastoreo. Brazilian Journal of Development, 2023, 9(12), 30956-30972. [CrossRef]

- Angadi, S. V., Umesh, M. R., Begna, S., & Gowda, P. (2022). Light interception, agronomic performance, and nutritive quality of annual forage legumes as affected by shade. Field Crops Research, 275, 108358.

- Pang, K., Van Sambeek, J. W., Navarrete-Tindall, N. E., Lin, C. H., Jose, S., & Garrett, H. E. (2019). Responses of legumes and grasses to non-, moderate, and dense shade in Missouri, USA. I. Forage yield and its species-level plasticity. Agroforestry Systems, 93, 11-24.

- Mercier, K. M., Teutsch, C. D., Fike, J. H., Munsell, J. F., Tracy, B. F., & Strahm, B. D. Impact of increasing shade levels on the dry-matter yield and botanical composition of multispecies forage stands. Grass and Forage Science, 2020, 75(3), 291-302. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A. F., Menezes, G. L., Goncalves, L. C., de Araujo, V. E., Ramirez, M. A., Júnior, R. G., ... & Lana, A. M. Q. Pasture traits and cattle performance in silvopastoral systems with Eucalyptus and Urochloa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Livestock Science, 2022, 262, 104973. [CrossRef]

- Sarmin, I. J., Rahman, M. S., Amin, M. H., & Ahmed, K. Effects of bark and stem exudates of eucalyptus on three crop plants. Journal of Science and Technology, 2020, 17, 24.

- Bosi C, Pezzopane JRM, Sentelhas PC, Santos PM, Nicodemo MLF (2014) Productivity and biometric characteristics of signal grass in a silvopastoral system. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Brasileira, 2014, 49:449–456. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A., Coble, A., Contosta, A. R., Orefice, J. N., Smith, R. G., & Asbjornsen, H. Forest conversion to silvopasture and open pasture: effects on soil hydraulic properties. Agroforestry Systems, 2020, 94, 869-879. [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, H. V., Valqui, L., Bobadilla, L. G., Arbizu, C. I., Alegre, J. C., & Maicelo, J. L. Influence of arboreal components on the physical-chemical characteristics of the soil under four silvopastoral systems in northeastern Peru. Heliyon, 2021, 7(8). [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J. V., Bento, L. R., Bresolin, J. D., Mitsuyuki, M. C., Oliveira, P. P. A., Pezzopane, J. R. M., ... & Martin-Neto, L. The long-term effects of intensive grazing and silvopastoral systems on soil physicochemical properties, enzymatic activity, and microbial biomass. Catena, 2022, 219, 106619. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Atencia, J., Loaiza-Usuga, J. C., Osorio-Vega, N. W., Correa-Londoño, G., & Casamitjana-Causa, M. Leaf litter decomposition in diverse silvopastoral systems in a neotropical environment. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 2020, 39(7), 710-729. [CrossRef]

- Lira Junior, M. A., Fracetto, F. J. C., Ferreira, J. D. S., Silva, M. B., & Fracetto, G. G. M. Legume silvopastoral systems enhance soil organic matter quality in a subhumid tropical environment. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2020, 84(4), 1209-1218. [CrossRef]

- Climate data for cities worldwide, Climate-Data.org, 2024.

- AOAC, Official Methods of Analysis. 17th Edition, The Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2001. Methods 950.46, 2001.

- Indah, A. S., Permana, I. G., & Despal, D. Correlation and determination of the Metabolizable Energy (ME) of tropical forage with nutrient content for ruminants. Aceh Journal of Animal Science, 2023, 8(2), 34-38. [CrossRef]

- Blake, G. R. (1965). Bulk density. Methods of soil analysis: Part 1 physical and mineralogical properties, including statistics of measurement and sampling, 9, 374-390.

- Danielson, R. E., & Sutherland, P. L. (1986). Porosity. Methods of soil analysis: part 1 physical and mineralogical methods, 5, 443-461.

- Walkley, A., & Black, I. A. (1934). An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil science, 37(1), 29-38.

- Rhoades, J. D. (1982). Cation exchange capacity. Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 chemical and microbiological properties, 9, 149-157.

- Díaz Pablo, M. E., Alegre Orihuela, J. C., Gómez Bravo, C. A., Mendoza Tamani, P., & Arévalo-Hernández, C. O. (2024). Reservas de carbono en tres sistemas silvopastoriles de la Amazonía peruana. Manglar, 21(3), 305-311.

- Dablin, L. J. Designing silvopastoral systems for the Amazon: a framework for the evaluation of native species (Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London)), 2020.

- De Freitas, A. F., Junqueira Carneiro, J., Venturin, N., de Souza Moreira, F. M., Guimaraes Ferreira, A. I., de Oliveira Lara, G. P., ... & Cardoso, I. M. Inga edulis Mart. Intercropped with pasture improves soil quality without compromising forage yields. Agroforestry Systems, 2020, 94(6), 2355-2366. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J. D., & Carpenter, F. L. Interplanting Inga edulis yields nitrogen benefits to Terminalia amazonia. Forest Ecology and Management, 2006, 233(2-3), 344-351.

- da Silva, E. R., da Costa Ayres, M. I., Neves, A. L., Uguen, K., de Oliveira, L. A., & Alfaia, S. S. Organic fertilization with residues of cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum) and inga (Inga edulis) for improving soil fertility in central Amazonia. In New generation of organic fertilizers. IntechOpen, 2021.

- Lojka, B., Preininger, D., Van Damme, P., Rollo, A., & Banout, J. Use of the Amazonian tree species Inga edulis for soil regeneration and weed control. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 2012, 89-101.

- Singh, H. P., Batish, D. R., & Kohli, R. K. Allelopathic interactions and allelochemicals: new possibilities for sustainable weed management. Critical reviews in plant sciences, 2003, 22(3-4), 239-311. [CrossRef]

- Harper, K. J., & McNeill, D. M. The role iNDF in the regulation of feed intake and the importance of its assessment in subtropical ruminant systems (the role of iNDF in the regulation of forage intake). Agriculture, 2015, 5(3), 778-790.

- Soper, F. M., & Sparks, J. P. Estimating ecosystem nitrogen addition by a leguminous tree: A mass balance approach using a woody encroachment chronosequence. Ecosystems, 2017, 20(6), 1164-1178. [CrossRef]

- Xavier, D. F., da Silva Lédo, F. J., Paciullo, D. S. D. C., Urquiaga, S., Alves, B. J., & Boddey, R. M. Nitrogen cycling in a Brachiaria-based silvopastoral system in the Atlantic forest region of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 2014, 99, 45-62.

- Smit, H. P., Reinsch, T., Swanepoel, P. A., Loges, R., Kluß, C., & Taube, F. Environmental impact of rotationally grazed pastures at different management intensities in South Africa. Animals, 2021 11(5), 1214. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C. V., Mello, A. C., Cunha, M. V. D., Silva, M. D. C., Santos, D. C. D., Santos, M. V., ... & Homem, B. G. C. Agronomic characteristics and nutritional value of cactus pear progenies. Agronomy Journal, 2021, 113(6), 4721-4735. [CrossRef]

| System | BD g cm-3 |

pH -- |

OM % |

P Ppm |

CEC | Ca 2+ | Mg 2+ Meq/100 g |

k + | Al 3+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tornillo | 1,33±0,18 | 4,24±0,50 | 3,12±0,18 | 3,43±0,21 | 9,07±0,56 | 0,36±0,18 | 0,25±0,03 | 0,14±0,02 | 0,83±0,40 |

| Eucalyptus | 1,38±0,04 | 4,85±0,10 | 3,76±0,26 | 3,20±0,95 | 9,01±5,05 | 7,61±4,01 | 1,81±0,97 | 0,35±0,35 | 0,00±0,00 |

| Guaba | 1,22±0,10 | 4,99±0,13 | 2,88±0,85 | 0,93±0,25 | 25,49±3,05 | 4,67±2,18 | 1,77±0,62 | 0,64±0,54 | 6,87±3,87 |

| Var | System | Light | System × Light | EE | P value | |||||||||||||

| SSPI | SSPII | SSPIII | ||||||||||||||||

| SSPI | SSPII | SSPIII | S | WS | S | WS | S | WS | S | WS | System | Light | System × Light | |||||

| FM (kg DM ha-1) |

1051 | 1051 | 1280 | 1164 | 1090 | 1103 | 999 | 1001 | 1100 | 1388 | 1171 | 318.29 | 0.5975 | 0.7284 | 0.8233 | |||

| FMH (kg MS ha-1) | 1210 | 1085 | 1161 | 1256 | 1047 | 1406ª | 1014BC | 983C | 1187ABC | 1380AB | 942C | 131.87 | 0.6384 | 0.0585 | 0.0328* | |||

| Protein (%) | 8.57b | 7.17b | 10.63ª | 9.55ª | 8.03b | 9.20 | 7.94 | 7.81 | 6.53 | 11.63 | 9.53 | 0.81 | 0.0045* | 0.0431* | 0.8764 | |||

| NDF (%) | 65.39 b | 69.72 a | 68.16 ab | 67.46 | 68.04 | 64.92 | 65.86 | 69.35 | 70.08 | 68.12 | 68.20 | 1.31 | 0.0215* | 0.5981 | 0.9439 | |||

| IVDMD (%) | 41.96 | 37.62 | 40.72 | 40.68 | 39.53 | 43.14 | 40.79 | 38.25 | 37.00 | 40.64 | 40.81 | 1.73 | 0.2017 | 0.5574 | 0.8637 | |||

| ME (MJ kg-1 de DM) | 8.08 a | 7.69 b | 7.77ª | 7.85 | 7.78 | 8.14 | 8.03 | 7.76 | 7.62 | 7.64 | 7.69 | 0.15 | 0.0214* | 0.5974 | 0.9437 | |||

| SSPI: Silvopastoral System with Guaba, SSPII: Silvopastoral System with Eucalyptus, SSPIII: Silvopastoral System with Tornillo, CS: With shade, SS: Without shade, FM: Forage Mass, FMH: Forage Mass by harvest, NDF: Neutral detergent fiber, IVDMD: In vitro dry matter digestibility, ME: Metabolizable energy, DM: Dry matter. *Indicates significant differences and interactions at a 5% significance level. Averages followed by different lowercase letters between the system and light factors are significantly different at the 5% probability level. Averages followed by different uppercase letters between the factor x light interactions are significantly different at the 5% probability level. | ||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).