Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Identification of MADS-Box Genes in Cucumber

2.2. Gene Structure and Motif Analysis

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Multiple Sequence Alignment

2.4. Gene Duplication Analysis and Genome Distribution

2.5. Analysis of Promoter Regions of CsMADS-Box Genes

2.6. Transcriptome Analysis of CsMADS-Box Genes in Cucumber

2.7. Transcriptome Analysis of CsMADS in Response to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of MADS-Box from Chinese Long 9930 (V3 Version)

3.2. Analysis of the Differences of Amino Acid Sequences of MADS-Box Family Members Between V1 and V3 Versions

3.3. Analysis of Protein Motif Difference of MADS-Box

3.4. CsMADS Multiple Sequence Alignment

3.5. Phylogenetic Relationship and Gene Structure Analysis of MADS-Box Genes

3.6. Chromosome Distribution Analysis of CsMADS-Box Genes

3.7. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in Gene Promoter Region

3.8. Expression Patterns of CsMADS in Different Tissues

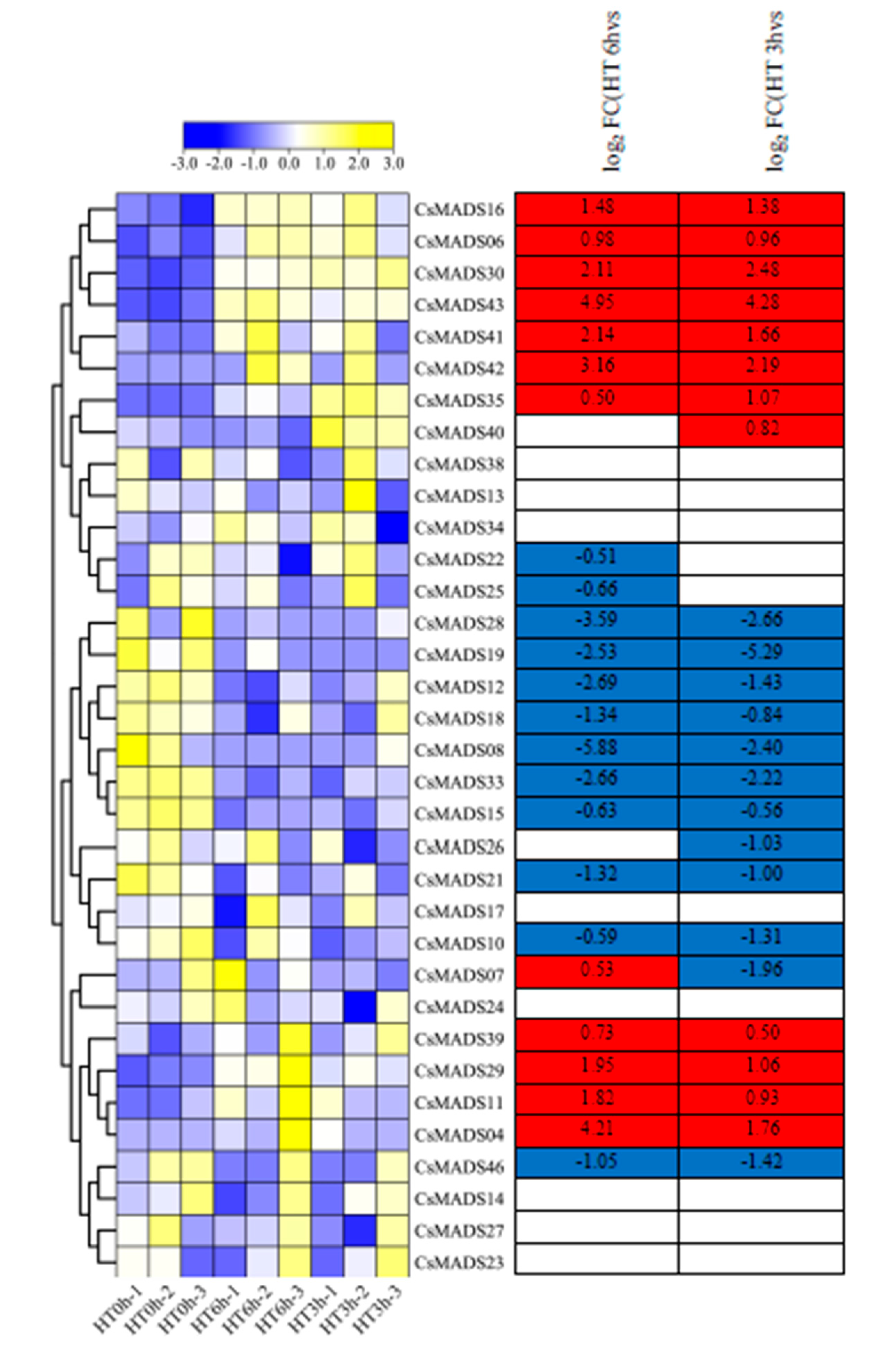

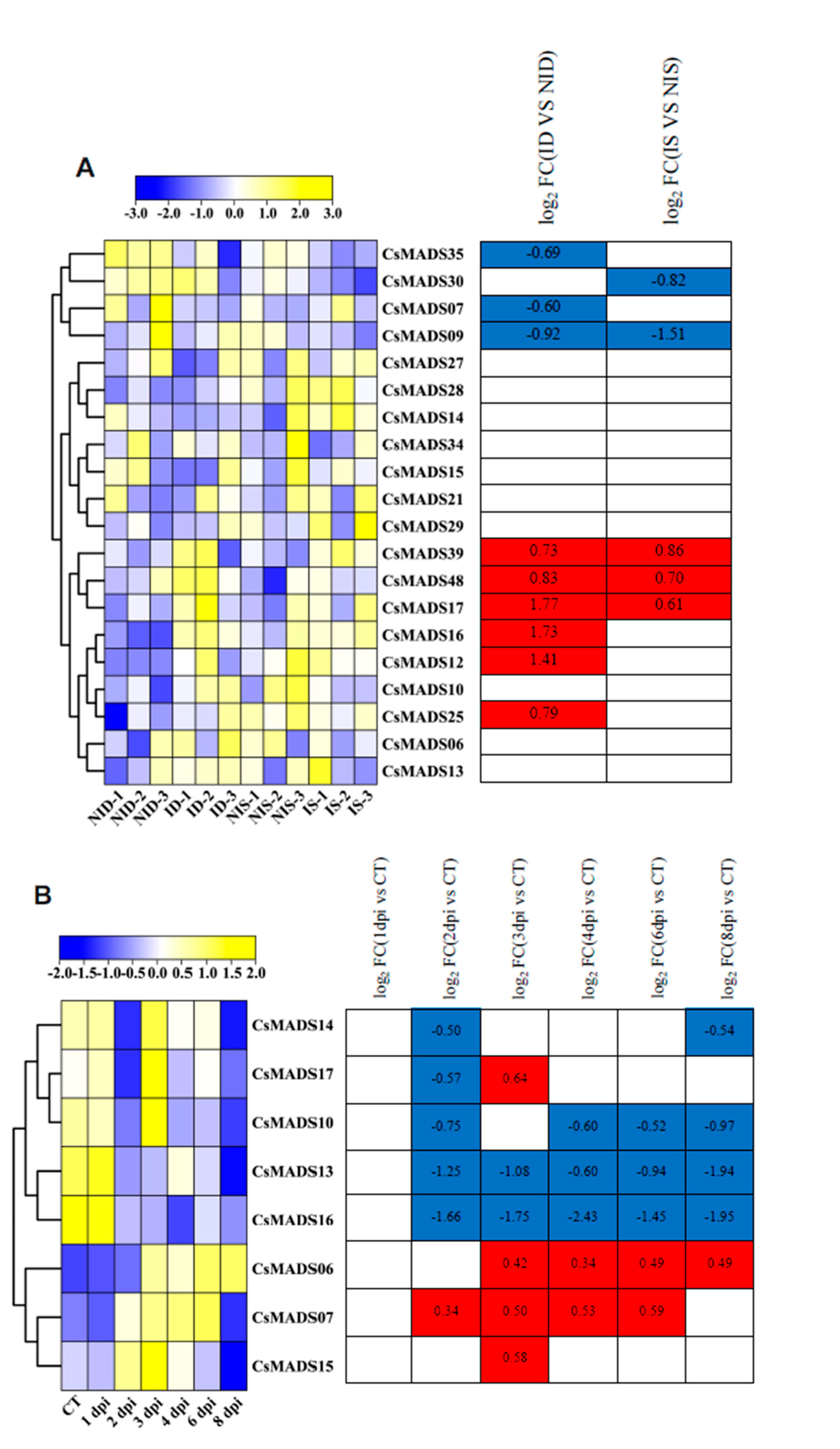

3.9. Expression Profiles of CsMADS Genes Under Abiotic and Biotic Stresses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riechmann, J.L. , and Meyerowitz, E.M. MADS domain proteins in plant development. Biol. Chem. 1997, 378, 1079–1101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Messenguy, F. , and Dubois, E. Role of MADS box proteins and their cofactors in combinatorial control of gene expression and cell development. Gene 2003, 316, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, K. , Melzer, R., and Theissen, G. MIKC-type MADS-domain proteins: structural modularity, protein interactions and network evolution in land plants. Gene 2005, 347, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B. , Egea-Cortines, M., de Andrade Silva, E., Saedler, H., and Sommer, H. Multiple interactions amongst floral homeotic MADS box proteins. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 4330–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riechmann, J.L. , Krizek, B.A., and Meyerowitz, E.M. Dimerization specificity of Arabidopsis MADS domain homeotic proteins APETALA1, APETALA3, PISTILLATA, and AGA-MOUS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 4793–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, E.M. , Dorit, R.L., and Irish, V.F. Molecular evolution of genes controlling petal and stamen development: duplication and divergence within the APETALA3 and PISTILLATA MADS-box gene lineages. Genetics 1998, 149, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschel, K. , Kofuji, R., Hasebe, M., Saedler, H., Munster, T., and Theissen, G. Two ancient classes of MIKC-type MADS-box genes are present in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Mol. Biol.Evol. 2002, 19, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Buylla, E.R. , Liljegren, S.J., Pelaz, S., Gold, S.E., Burgeff, C., Ditta, G.S., et al. MADS-box gene evolution beyond flowers: expression in pollen, endosperm, guard cells, roots and trichomes. Plant J. 2000, 24, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Riquelme, J. , Lijavetzky, D., Martínez-Zapater, J.M., and Carmona, M.J. Genome-wide analysis of MIKCC-type MADS box genes in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Buylla, E.R. , Pelaz, S., Liljegren, S.J., Gold, S.E., Burgeff,C., Ditta, G.S., et al. An ancestral MADS-box gene duplication occurred before the divergence of plants and animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97, 5328–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bodt, S. , Raes, J., Florquin, K., Rombauts, S., Rouze, P., Theissen, G., and Van de Peer, Y. Genomewide structural annotation and evolutionary analysis of the type I MADS-box genes in plants. J. Mol. Evol. 2003, 56, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pařenicová, L. , de Folter, S., Kieffer, M., Horner, D.S., Favalli, C., Busscher, J., et al. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: new openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1538–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanofsky, M.F. , Ma, H., Bowman, J.L., Drews, G.N., Feldmann, K.A., and Meyerowitz, E.M. The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene agamous resembles transcription factors. Nature 1990, 346, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigel, D. , and Meyerowitz, E.M. The ABCs of floral homeotic genes. Cell 1994, 78, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H. , and dePamphilis, C. The ABCs of floral evolution. Cell 2000, 101, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepworth, S.R. , Valverde, F., Ravenscroft, D., Mouradov, A., and Coupland, G. Antagonistic regulation of flowering-time gene SOC1 by CONSTANS and FLC via separate promoter motifs. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 4327–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C. , Chen, H., Er, H.L., Soo, H.M., Kumar, P.P., Han, J.-H., et al. Direct interaction of AGL24 and SOC1 integrates flowering signals in Arabidopsis. Development 2008, 135, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, S.D. , and Amasino, R.M. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searle, I. , He, Y., Turck, F., Vincent, C., Fornara, F., Krober, S., et al. The transcription factor FLC confers a flowering response to vernalization by repressing meristem competence and systemic signaling in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H. , Xu, Y., Tan, E.L., and Kumar, P.P. AGAMOUS-LIKE 24, a dosage-dependent mediator of the flowering signals. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 16336–16341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaels, S.D. , Ditta, G., Gustafson-Brown, C., Pelaz, S., Yanofsky, M., and Amasino, R.M. AGL24 acts as a promoter of flowering in Arabidopsis and is positively regulated by vernalization. Plant J. 2003, 33, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, U. , Hohmann, S., Nettesheim, K., Wisman, E., Saedler, H., and Huijser, P. Molecular cloning of SVP: a negative regulator of the floral transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2000, 21, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H. , Yoo, S.J., Park, S.H., Hwang, I., Lee, J.S., and Ahn, J.H. Role of SVP in the control of flowering time by ambient temperature in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Q. , Ferrándiz, C., Yanofsky, M.F., and Martienssen, R. The FRUITFULL MADS-box gene mediates cell differentiation during Arabidopsis fruit development. Development 1998, 125, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrándiz, C. , Liljegren, S.J., and Yanofsky, M.F. Negative regulation of the SHATTERPROOF genes by FRUITFULL during Arabidopsis fruit development. Science 2000, 289, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rounsley, S.D. , Ditta, G.S., and Yanofsky, M.F. Diverse roles for MADS box genes in Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia-López, R. , García-Ponce, B., Dubrovsky, J.G., Garay-Arroyo, A., Pérez-Ruíz, R.V., Kim, S.-H., et al. An AGAMOUS-related MADS-box gene, XAL1 (AGL12), regulates root meristem cell proliferation and flowering transition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao PX, Zhang J, Chen SY, Wu J, Xia JQ, Sun LQ, Ma SS, Xiang CB. Arabidopsis MADS-box factor AGL16 is a negative regulator of plant response to salt stress by downregulating salt-responsive genes. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 2418–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li X, Yu B, Wu Q, Min Q, Zeng R, Xie Z, Huang J. OsMADS23 phosphorylated by SAPK9 confers drought and salt tolerance by regulating ABA biosynthesis in rice. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tardif, G.; Kane, N.A.; Adam, H.; Labrie, L.; Major, G.; Gulick, P.; Sarhan, F.; Laliberté, J.F. Interaction network of proteins associated with abiotic stress response and development in wheat. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 63, 703–718. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling S, Kennedy A, Pan S, Jermiin LS, Melzer R. Genome-wide analysis of MIKC-type MADS-box genes in wheat: pervasive duplications, functional conservation and putative neofunctionalization. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, W.; Song, X.; Liu, T.; Huang, Z.; Ren, J.; Hou, X.; Li, Y. Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family in Brassica rapa (Chinese cabbage). Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015, 290, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu L, Liu S. Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family in cucumber. Genome. 2012, 55, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Williams, N.; Misleh, C.; Li, W.W. MEME: Discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W369–W373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorrips, R.E. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, P.; Huang, S.; Fei, Z.; Lin, K. RNA-Seq improves annotation of protein-coding genes in the cucumber genome. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yin, J.; Liang, Y.; Liu, J.; Jia, J.; Huo, H.; Wu, Z.; Yang, R.; Gong, H. Transcriptomic dynamics provide an insight into the mechanism for silicon-mediated alleviation of salt stress in cucumber plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 174, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Tang, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Ren, Z. Genome-Wide identification and expression analysis of Hsf and Hsp gene families in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 95, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.N.; Savory, E.A.; Vaillancourt, B.; Childs, K.L.; Hamilton, J.P.; Day, B.; Buell, C.R. Expression Profiling of Cucumis sativus in Response to Infection by Pseudoperonospora cubensis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Qi, X.; Chen, X. Elucidation of the molecular responses of a cucumber segment substitution line carrying Pm5.1 and its recurrent parent triggered by powdery mildew by comparative transcriptome profiling. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Dong, Q.; Ji, Z.; Chi, F.; Cong, P.; Zhou, Z. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MADS-box gene family in apple. Gene 2015, 555, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffares, D.C.; Penkett, C.J.; Bähler, J. Rapidly regulated genes are intron poor. Trends Genet. 2008, 24, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindi, T.; Al-Abdallat, A.M. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MADS-box gene family in American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana). Plants 2021, 10, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Joseph, Z.; Gitter, A.; Simon, I. Studying and modelling dynamic biological processes using time-series gene expression data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenicová, L.; de Folter, S.; Kieffer, M.; Horner, D.S.; Favalli, C.; Busscher, J.; Cook, H.E.; Ingram, R.M.; Kater, M.M.; Davies, B.; et al. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the complete MADS-box transcription factor family in Arabidopsis: New openings to the MADS world. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1538–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, I.L.; McQuinn, R.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Irish, V.F. Functional diversification of AGAMOUS lineage genes in regulating tomato flower and fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1795–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardeli, S.M.; Artico, S.; Aoyagi, G.M.; de Moura, S.M.; da Franca Silva, T.; Grossi-de-Sa, M.F.; Romanel, E.; Alves-Ferreira, M. Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family in polyploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) and in its diploid parental species (Gossypium arboreum and Gossypium raimondii). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, X.; Guang, X.; Zhang, Y. Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family in watermelon. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 80, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Y.; Yu, D.; Wang, D.; Guo, D.; Guo, C. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the MADS-box gene family in soybean. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 3901–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora R, Agarwal P, Ray S, Singh AK, Singh VP, Tyagi AK, et al. MADS-box gene family in rice: genome-wide identification, organization and expression profiling during reproductive development and stress. BMC Genomics. 2007, 8, 242. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Nie G, Feng G, Xu X, Li D, Wang X, Huang L, Zhang X. Genome-wide identification of MADS-box gene family in orchardgrass and the positive role of DgMADS114 and DgMADS115 under different abiotic stress. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022, 223, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong X, Deng H, Ma W, Zhou Q, Liu Z. Genome-wide identification of the MADS-box transcription factor family in autotetraploid cultivated alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) and expression analysis under abiotic stress. BMC Genomics. 2021, 22, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma J, Yang Y, Luo W, Yang C, Ding P, Liu Y, Qiao L, Chang Z, Geng H, Wang P, Jiang Q, Wang J, Chen G, Wei Y, Zheng Y, Lan X. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MADS-box gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ). PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0181443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Serial No. | Gene name | Gene ID(V3) | Gene ID(V1) | Chromosamal location | Group | Subfamily |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CsMADS01 | CsaV3_4G010090.1 | Csa004117 | 4 | MIKC | SEP |

| 2 | CsMADS02 | CsaV3_6G008200.1 | Csa008448 | 6 | MIKC | SEP |

| 3 | CsMADS03 | CsaV3_1G006210.1 | Csa004591 | 1 | MIKC | SEP |

| 4 | CsMADS04 | CsaV3_6G033790.1 | Csa013129 | 6 | MIKC | SEP |

| 5 | CsMADS05 | CsaV3_6G006010.1 | Csa014213, Csa025232 | 6 | MIKC | AGL6 |

| 6 | CsMADS06 | CsaV3_4G010080.1 | Csa004120 | 4 | MIKC | AP1-FUL |

| 7 | CsMADS07 | CsaV3_1G006220.1 | Csa004592 | 1 | MIKC | AP1-FUL |

| 8 | CsMADS08 | CsaV3_6G033800.1 | Csa013130 | 6 | MIKC | AP1-FUL |

| 9 | CsMADS09 | CsaV3_1G009750.1 | Csa014249, Csa026408 | 1 | MIKC | TM8 |

| 10 | CsMADS10 | CsaV3_5G005600.1 | Csa012493 | 5 | MIKC | SOC1 |

| 11 | CsMADS11 | CsaV3_3G016650.1 | Csa021114 | 3 | MIKC | SOC1 |

| 12 | CsMADS12 | CsaV3_3G009400.1 | 3 | MIKC | SOC1 | |

| 13 | CsMADS13 | CsaV3_6G006020.1 | Csa014140, Csa025231 | 6 | MIKC | SOC1 |

| 14 | CsMADS14 | CsaV3_5G003360.1 | Csa012879 | 5 | MIKC | SOC1 |

| 15 | CsMADS15 | CsaV3_6G045010.1 | Csa012099 | 6 | MIKC | SVP |

| 16 | CsMADS16 | CsaV3_2G030300.1 | Csa003859 | 2 | MIKC | SVP |

| 17 | CsMADS17 | CsaV3_4G014770.1 | Csa017496 | 4 | MIKC | SVP |

| 18 | CsMADS18 | CsaV3_7G006940.1 | Csa003446 | 7 | MIKC | SVP |

| 19 | CsMADS19 | CsaV3_5G040310.1 | 5 | MIKC | SVP | |

| 20 | CsMADS20 | CsaV3_6G052910.1 | 6 | MIKC | SVP | |

| 21 | CsMADS21 | CsaV3_3G045590.1 | Csa017887 | 3 | MIKC | AP3-PI |

| 22 | CsMADS22 | CsaV3_4G028010.1 | Csa011135 | 4 | MIKC | AP3-PI |

| 23 | CsMADS23 | CsaV3_6G015770.1 | Csa000681 | 6 | MIKC | AG |

| 24 | CsMADS24 | CsaV3_1G032920.1 | Csa017355 | 1 | MIKC | AG |

| 25 | CsMADS25 | CsaV3_6G051220.1 | 6 | MIKC | AG | |

| 26 | CsMADS26 | CsaV3_5G040370.1 | 5 | MIKC | AG | |

| 27 | CsMADS27 | CsaV3_4G028880.1 | Csa021473 | 4 | MIKC | AGL15 |

| 28 | CsMADS28 | CsaV3_3G031900.1 | Csa020302 | 3 | MIKC | AGL15 |

| 29 | CsMADS29 | CsaV3_3G048150.1 | Csa002117 | 3 | MIKC | AGL17 |

| 30 | CsMADS30 | CsaV3_4G014700.1 | Csa017500 | 4 | MIKC | AGL17 |

| 31 | CsMADS31 | CsaV3_6G044810.1 | Csa012111 | 6 | MIKC | AGL17 |

| 32 | CsMADS32 | CsaV3_4G030750.1 | Csa015983 | 4 | MIKC | MIKC* |

| 33 | CsMADS33 | CsaV3_6G008210.1 | Csa008449 | 6 | Mσ | |

| 34 | CsMADS34 | CsaV3_5G032860.1 | Csa000939 | 5 | Mσ | |

| 35 | CsMADS35 | CsaV3_1G005580.1 | Csa004560 | 1 | Mσ | |

| 36 | CsMADS36 | CsaV3_3G016620.1 | 3 | AG | ||

| 37 | CsMADS37 | CsaV3_4G000010.1 | Csa021069 | 4 | Mα | |

| 38 | CsMADS38 | CsaV3_1G032570.1 | Csa017317 | 1 | Mα | |

| 39 | CsMADS39 | CsaV3_1G015790.1 | Csa007119 | 1 | Mα | |

| 40 | CsMADS40 | CsaV3_2G016620.1 | Csa020265 | 2 | Mα | |

| 41 | CsMADS41 | CsaV3_3G045410.1 | Csa017909 | 3 | Mα | |

| 42 | CsMADS42 | CsaV3_UNG063480.1 | Mα | |||

| 43 | CsMADS43 | CsaV3_6G051590.1 | 6 | Mα | ||

| 44 | CsMADS44 | CsaV3_3G020270.1 | Csa014962 | 3 | Mβ | |

| 45 | CsMADS45 | CsaV3_2G019470.1 | Csa017249 | 2 | Mβ | |

| 46 | CsMADS46 | CsaV3_3G038110.1 | Csa002566 | 3 | Mγ | |

| 47 | CsMADS47 | CsaV3_1G038060.1 | Csa001552 | 1 | Mγ | |

| 48 | CsMADS48 | CsaV3_1G017300.1 | Csa007130 | 1 | Mγ |

| gene name | V1 | V3 | 氨基酸序列相似度 | gene name | V1 | V3 | 氨基酸序列相似度 |

| Csa004117 | 245 | 245 | 100% | Csa011135 | 191 | 211 | |

| Csa008448 | 241 | 241 | 100% | Csa017355 | 254 | 254 | 100% |

| Csa004591 | 250 | 255 | Csa021473 | 255 | 286 | ||

| Csa013129 | 227 | 241 | Csa020302 | 204 | 250 | ||

| Csa014213 | 171 | 246 | Csa002117 | 91 | 225 | ||

| Csa025232 | 171 | 246 | Csa017500 | 122 | 235 | ||

| Csa004120 | 197 | 555 | Csa012111 | 204 | 228 | ||

| Csa004592 | 248 | 261 | Csa015983 | 323 | 350 | ||

| Csa013130 | 201 | 223 | Csa008449 | 107 | 181 | ||

| Csa014249 | 203 | 202 | Csa000939 | 339 | 339 | 100% | |

| Csa026408 | 210 | 203 | Csa004560 | 313 | 355 | ||

| Csa012493 | 182 | 282 | Csa021069 | 228 | 228 | 100% | |

| Csa021114 | 177 | 183 | Csa017317 | 173 | 173 | 100% | |

| Csa014140 | 221 | 221 | 100% | Csa007119 | 202 | 602 | |

| Csa025231 | 221 | 221 | 100% | Csa020265 | 187 | 187 | 100% |

| Csa012879 | 222 | 222 | 100% | Csa017909 | 225 | 225 | 100% |

| Csa012099 | 228 | 228 | 100% | Csa014962 | 216 | 250 | |

| Csa003859 | 245 | 230 | Csa017249 | 294 | 202 | ||

| Csa017496 | 67 | 173 | Csa002566 | 387 | 387 | 100% | |

| Csa003446 | 67 | 221 | Csa001552 | 225 | 225 | 100% | |

| Csa017887 | 244 | 276 | Csa007130 | 219 | 213 | ||

| Csa000681 | 135 | 373 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).