Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

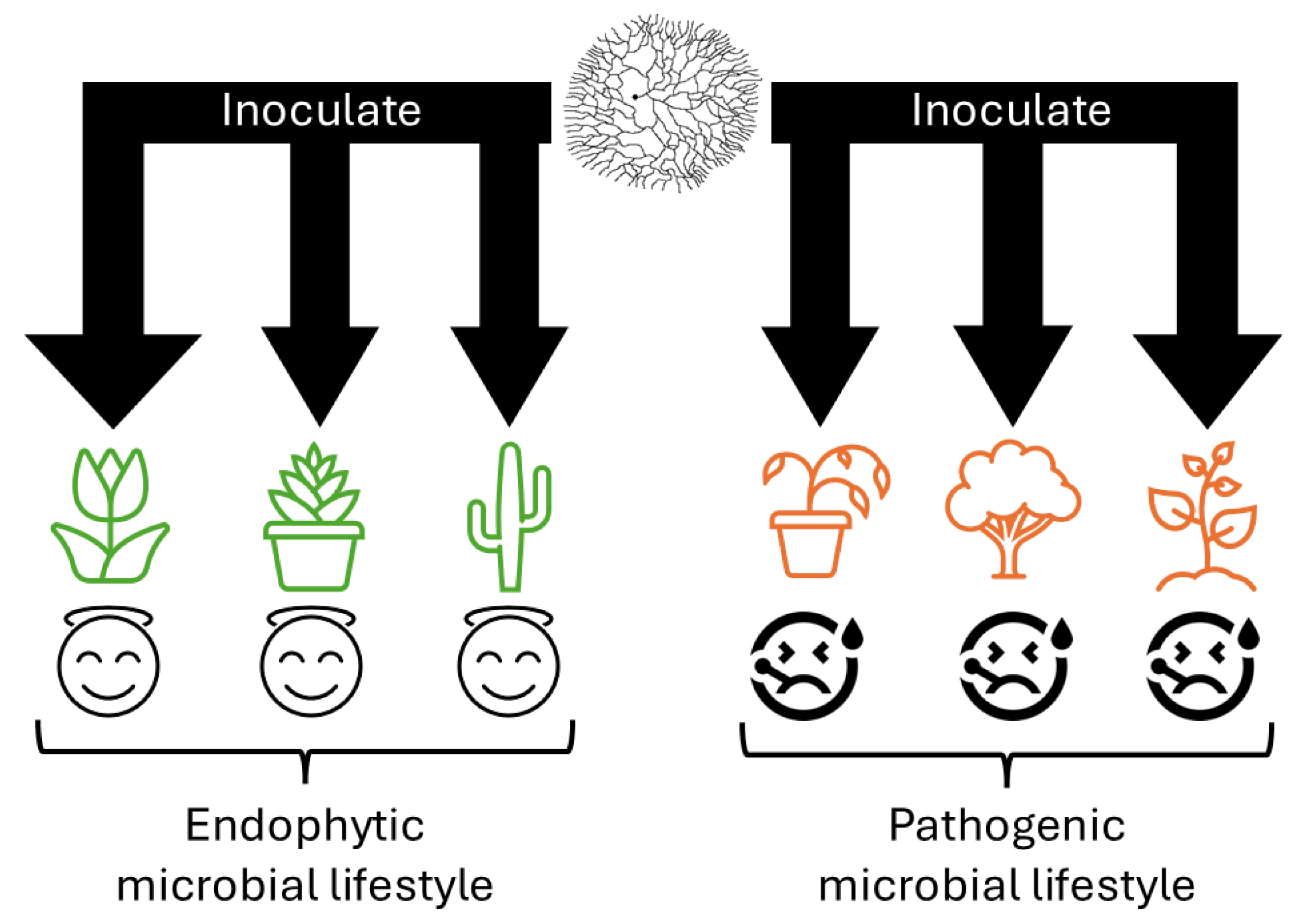

2. Lifestyle as a Result of Host Colonization

2.1. Host Range of Pathogens

2.2. Host Range of Endophytes

| Colletotrichum species | Host range as pathogen | Host range as endophyte |

| C. lupini | Lupinus species [37] | Coffea arabica [60] |

| C. boninense s. l. | Protea species, Carica papaya, Capsicum species, Citrus species, Coffea species, Cucurbita species, Cymbidium species, Dracaena marginata, Diospyros australis, Solanum species, Passiflora edulis, Crinum asiaticum, Euonymus japonica, Persea americana, Phyllanthus acidus, Brassica oleracea [38] | Maytenus ilicifolia, Podocarpaceae, Myrtaceae, Coffea species, Mangifera indica, Pachira species Pleione bulbocodioides, Oncidium flexuosum, Quercus salicifolia, Theobroma cacao, Zamia obliqua, Parsonsia capsularis [38]; Eperua falcata, Goupia glabra, Manilkara bidentata, Mora excelsa, Catostemma fragrans, Carapa guianensis [61]; Podocarpaceae [62] |

| C. capsici | Piper betle, Vigna unguiculata, Phaseolus vulgaris, Cicer arietinum, Lupinus angustifolius, Pisum sativum, Vigna species [39] | Arachia hypogaea, Cajanus cajan, Phaseolus vulgaris, Phasolus lunatus [39] |

| C. acutatum s. l. | Malus domestica, Aspalathus linearis, Acer platanoides, Araucaria excelsa, Coffea arabica, Cyclamen species, Fragaria x ananassa, Lobelia species, Chrysanthemum coronarium, Actinidia species, Anemone coronaria, Cyclamen species, Hevea brasiliensis, Lupinus species, Nuphar luteum, Nymphaea alba, Oenothera species, Passiflora edulis, Parthenocissus species, Penstemon species, Persea americana, Prunus cerasus, Pyrus species, Solanum species, Ugni molinae, Vaccinium corymbosum, Citrus aurantium, Mahonia aquifolium [40] | Coffea robusta, Mangifera indica, Tsuga canadensis, Theobroma cacao, Dendrobium nobile [40] |

| C. graminicola | Zea mays [42]; Sorghum species [41] | Zea mays [63]; Lolium perenne [64] |

| C. orbiculare s. s. | Cucurbitaceae species [43]; Nicotiana species [65] | |

| C. higginsianum | Brassicaceae species [23]; Campanula species [66]; Rumex species [67] | Centella asiatica [69] |

| C. siamense | Capsicum species, Pyrus pyrifolia [45] | Pennisetum purpureum, Cymbopogon citratus [26]; Paullinia cupana [68] |

| C. gloeosporioides s. s. | Spondias pinnata, Persea americana, Aegle marmelos, Anacardium occidentale, Citrus species, Syzygium species, Durio zibethinus, Psidium guajava, Annona muricata, Mangifera indica, Garcinia mangosteen, Carica papaya, Passiflora edulis, Punica granatum, Nephelium lappaceum, Phyllanthus heyneanus, Achras sapota, Annona squamosa, Lycopersicon esculentum, Flacourtia inermis, Elaeocarpus glandulifer, Feronia limonia [70]; Olea europaea, Malus domestica [71] | Podocarpaceae [62]; Lolium perenne [64]; Centella asiatica [69]; Huperzia serrata [72]; Citrus species, Commelina benghalensis, Sida rhombifolia, Amaranthus deflexus [73]; Theobroma cacao, Anacardium excelsum, Genipa americana, Pentagonia macrophylla, Tetragastris panamensis, Trichilia tuberculata, Virola surinamensis, Cordia alliodora, Merremia umbellata, Zamia obliqua [74]; Uncaria rhynchophylla [75]; Camellia sinensis [76] |

| C. fructicola | Coffea species [47], Camellia sinensis, Citrus species, Malus species, Persea americana, Prunus persica, Pyrus species [77] | Coffea species [78]; Hevea species [79]; Dendrobium species [80] |

| C. tofieldiae | Arabidopsis thaliana [12], Ornithogalum umbellatum [28]; Capsella rubella [22] | Arabidopsis thaliana [12,22,51]; Zea mays, Solanum lycopersicum [50]; Cardamine hirsuta [22] |

| C. brasiliense | Passiflora edulis | Passiflora edulis |

| C. chrysophilum | Cucurbitaceae [54], Musa species [52]; Anacardium occidentale [53] | Theobroma species, Genipa species [56]; Anacardium occidentale [55] |

| C. coccodes | Capsicum species [59]; Solanum lycopersicum, Solanum tuberosum [57] | Brassica alba, Latuca sativa, Lepidum sativum, Brassica oleracea, Chrysanthemum species, Solanum nigrum [57] |

3. Comparative Genomic Approaches for Understanding the Host Range of Pathogenic Colletotrichum Fungi

4. Merits of Applying Endophytic Fungal Research to Phytopathology

4.1. Comparative Omics

4.2. C. tofieldiae Study System

5. Applications of Colletotrichum Research

5.1. Endophytic Fungi

5.2. Lessons from Pathogenic Fungi

6. Relationship Between Host Range and Lifestyle

7. Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

Acknowledgements

References

- Turner, T.R.; James, E.K.; Poole, P.S. The plant microbiome. Genome Biol. 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.; Koskella, B. Nutrient- and dose-dependent microbiome-mediated protection against a plant pathogen. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 2487–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazcano, C.; Boyd, E.; Holmes, G.; Hewavitharana, S.; Pasulka, A.; Ivors, K. The rhizosphere microbiome plays a role in the resistance to soil-borne pathogens and nutrient uptake of strawberry cultivars under field conditions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, F.E.; Tinker, P.B. Mechanisms of absorption of phosphate from soil by Endogone mycorrhizas. Nature 1971, 233, 278–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ent, S.; Van Hulten, M.; Pozo, M.J.; Czechowski, T.; Udvardi, M.K.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Ton, J. Priming of plant innate immunity by rhizobacteria and β-aminobutyric acid: differences and similarities in regulation. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, R.S.; Sheehan, K.B.; Stout, R.G.; Rodriguez, R.J.; Henson, J.M. Thermotolerance generated by plant/fungal symbiosis. Science 2002, 298, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, R.V. Effects of pathogens and disease on plant physiology. In Agrios’ Plant Pathology, 6th ed.; Oliver, R.P., Hückelhoven, R., Del Ponte, E.M., Di Pietro, A., Eds.; Academic Press: London, United Kingdom, 2024; pp. 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, P.S.; Shane, W.W.; MacKenzie, D.R. Crop losses due to plant pathogens. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1984, 2, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Sun, A.; Jiao, X.; Chen, Q.-L.; Li, F.; He, J.-Z.; Hu, H.-W. National-scale investigation reveals the dominant role of phyllosphere fungal pathogens in sorghum yield loss. Environ. Int. 2024, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, S.; Smith, S.E.; Smith, F.A. Characterization of two arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in symbiosis with Allium porrum: colonization, plant growth, and phosphate uptake. New Phytol. 1999, 144, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Horowitz, S.; Sharon, A. Pathogenic and nonpathogenic lifestyles in Colletotrichum acutatum from strawberry and other plants. Phytopathology 2001, 91, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiruma, K.; Aoki, S.; Takino, J.; Higa, T.; Devi Utami, Y.; Shiina, A.; Okamoto, M.; Nakamura, M.; Kawamura, N.; Ohmori, Y.; Sugita, R.; Tanoi, K.; Sato, T.; Oikawa, H.; Minami, A.; Iwasaki, W.; Saijo, Y. A fungal sesquiterpene biosynthesis gene cluster critical for mutualist-pathogen transition in Colletotrichum tofieldiae. Nature Commun. 2023, 14, 5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.P.; Goodman, R.M. Host variation for interactions with beneficial plant-associated microbes. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 1999, 37, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.T.; Zhang, L.; He, S.Y. Plant-microbe interactions facing environmental challenge. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Gao, X.; Feng, B.; Sheen, J.; Shan, L.; He, P. Plant immune response to pathogens differs with changing temperatures. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, B.; Castroverde, C.D.M.; Velásquez, A.C.; Hubbard, E.; Pulman, J.A.; Yao, J.; Childs, K.L.; Tsuda, K.; Montgomery, B.L.; He, S.Y. Dual impact of elevated temperature on plant defence and bacterial virulence in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Loayza, P.; White, J.F., Jr.; Torres, M.S.; Balslev, H.; Kristiansen, T.; Svenning, J.-C.; Gil, N. Light converts endosymbiotic fungus to pathogen, influencing seedling survival and niche-specific filling of a common tropical tree, Iriartea deltoidea. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.L.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; Foster, G.D. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talhinhas, P.; Baroncelli, R. Colletotrichum species and complexes: geographic distribution, host range, and conservation status. Fungal Divers. 2021, 110, 109–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Cannon, P.F.; Crous, P.W. Colletotrichum species with curved conidia from herbaceous hosts. Fung. Divers. 2009, 39, 45–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, K.D.; Cai, L.; Cannon, P.F.; Crouch, J.A.; Crous, P.W.; Damm, U.; Goodwin, P.H.; Chen, H.; Johnston, P.R.; Jones, E.B.G.; Liu, Z.Y.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Moriwaki, J.; Noireung, P.; Pennycook, S.R.; Pfenning, L.H.; Prihastuti, H.; Sato, T.; Shivas, R.G.; Tan, Y.P.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Weir, B.S.; Yang, Y.L.; Zhang, J.Z. Colletotrichum - names in current use. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 147–182. [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma, K.; Gerlach, N.; Sacristán, S.; Nakano, R.T.; Hacquard, S.; Kracher, B.; Neumann, U.; Ramírez, D.; Bucher, M.; O’Connell, R.J.; Schulze-Lefert, P. Root endophyte Colletotrichum tofieldiae confers plant fitness benefits that are phosphate status dependent. Cell, 2016, 165, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; O’Connell, R.J.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum destructivum species complex - hemibiotrophic pathogens of forage and field crops. Stud. Mycol. 2014, 79, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ani, L.K.T.; Furtado, E.L. The effect of incompatible plant pathogens on the host plant. In Molecular Aspects of Plant Beneficial Microbes in Agriculture; Sharma, V., Salwan, R., Al-Ani, L.K.T., Eds.; Academic Press: London, United Kingdom, 2020; pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, T.A.; Venter, S.N. Pantoea ananatis: an unconventional plant pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 10, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manamgoda, D.S.; Udayanga, D.; Cai, L.; Chukeatirote, E.; Hyde, K.D. Endophytic Colletotrichum from tropical grasses with a new species C. endophytica. Fungal Divers. 2013, 61, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, D.O.; Silva, M.A.; Pinho, D.B.; Pereira, O.L.; Furtado, G.Q. Diversity of pathogenic and endophytic Colletotrichum isolates from Licania tomentosa in Brazil. Forest Pathol. 2018, 48, e12448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Moriwaki, J.; Kaneko, S. Anthracnose fungi with curved conidia, Colletotrichum spp. Belonging to ribosomal groups 9-13, and their host ranges in Japan. Jarq Jpn Agr. Res. Q. 2015, 49, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.-L.; Chen, Y.-S.; Mei, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, H.-B. Disease risk of the foliar endophyte Colletotrichum from invasive Ageratina adenophora to native plants and crops. Fungal Ecol. 2024, 72, 101386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cornelissen, B.; Rep, M. Host-specificity factors in plant pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2020, 144, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nürnberger, T.; Lipka, V. Non-host resistance in plants: new insights into an old phenomenon. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005, 6, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryanarayanan, T.S.; Devarajan, P.T.; Girivasan, K.P.; Govindarajulu, M.B.; Kumaresan, V.; Murali, T.S.; Rajamani, T.; Thirunavukkarasu, N.; Venkatesan, G. The host range of multi-host endophytic fungi. Curr. Sci. 2018, 115, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U’Ren, J.M.; Lutzoni, F.; Miadlikowska, J.; Laetsch, A.D.; Arnold, A.E. Host and geographic structure of endophytic and endolichenic fungi at a continental scale. Am. J. Bot. 2012, 99, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, P.; Dodd, J.C.; Jeger, M.J.; Plumbley, R.A. The biology and control of Colletotrichum species on tropical fruit crops. Plant Pathol. 1990, 39, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, J.A.; Clarke, B.B.; White Jr., J. F.; Hillman, B.I. Systematic analysis of the falcate-spored graminicolous Colletotrichum and a description of six new species from warm-season grasses. Mycologia 2009, 101, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, P.R.; Jones, D. Relationships among Colletotrichum isolates from fruit-rots assessed using rDNA sequences. Mycologia 1997, 89, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhinhas, P.; Baroncelli, R.; Le Floch, G. Anthracnose of Lupins caused by Colleotrichum lupini: a recent disease and successful worldwide pathogen. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 98, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Damm, U.; Cannon, P.F.; Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Johnston, P.R.; Weir, B.S.; Tan, Y.P.; Shivas, R.G.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum boninense species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pring, R.J.; Nash, C.; Zakaria, M.; Bailey, J.A. Infection process and host range of Colletotrichum capsici. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1995, 46, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, U.; Cannon, P.F.; Woudenberg, J.H.C.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 37–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, J.A.; Clarke, B.B.; White Jr., J. F.; Hillman, B.I. Systematic analysis of the falcate-spored graminicolous Colletotrichum and a description of six new species from warm-season grasses. Mycologia 2009, 101, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, H.; Politis, D.J.; Poneleit, C.G. Pathogenicity, host range, and distribution of Colletotrichum graminicola on corn. Phytopathol. 1973, 64, 293–296. [Google Scholar]

- Damm, U.; Cannon, P.F.; Liu, F.; Barreto, R.W.; Guatimosim, E.; Crous, P.W. The Colletotrichum orbiculare species complex: important pathogens of field crops and weeds. Fungal Divers. 2013, 61, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Goodwin, P.H.; Hsiang, T. Infection of Nicotiana species by the anthracnose fungus, Colletotrichum orbiculare. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2001, 107, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Tang, G.; Zheng, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Qi, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Chang, X.; Zhang, S.; Gong, G. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Colletotrichum species associated with anthracnose disease in peppers from Sichuan Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, L.L.; de Almeida, L.N.; Pereira, J.O.; Neto, P.Q.C.; de Azvedo, J.L. Colletotrichum siamense, a mycovirus-carrying endophyte, as a biological control strategy for Anthracnose in Guarana plants. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2021, 64, e21200534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prihastuti, H.; Cai, L.; Chen, H.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Characterization of Colletotrichum species associated with coffee berries in northern Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, A.E.; Lutzoni, F. Diversity and host range of foliar fungal endophytes: are tropical leaves biodiversity hotspots? Ecology 2007, 88, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, R.J.; White Jr., J. F.; Arnold, A.E.; Redman, R.S. Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-González, S.; Marín, P.; Sánchez, R.; Arribas, C.; Kruse, J.; González-Melendi, P.; Brunner, F.; Sacristán, S. Mutualistic Fungal Endophyte Colletotrichum tofieldiae Ct0861 colonizes and increases growth and yield of maize and tomato plants. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, E.; Alonso, Á.; Platas, G.; Sacristán, S. The endophtyic mycobiota of Arabidopsis thaliana. Fungal Divers. 2013, 60, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, W.A.S.; Lima, W.G.; Nascimento, E.S.; Michereff, S.J.; Câmara, M.P.S. The impact of phenotypic and molecular data on the inference of Colletotrichum diversity associated with Musa. Mycologia 2017, 109, 912–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, J.S. , Câmara, M.P.S.; Lima, W.G.; Michereff, S.J.; Doyl, V.P. Why species delimitation matters for fungal ecology: Colletotrichum diversity on wild and cultivated cashew in Brazil. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, W.A.S.; da Costa, C.A.; Veloso, J.S.; Lima, W.G.; Correia, K.C.; Michereff, S.J.; Pinho, D.B.; Câmara, M.P.S.; Reis, A. Diversity of Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose in Chayote in Brazil, with a description of two new species in the C. magnum complex. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, D.G.B.; Amaral, A.G.G.; Duarte, I.G.; da Silva, A.C.; Vieira, W.A.S.; Castlebury, L.A.; Câmara, M.P.S. Endophytic species of Colletotrichum associated with cashew tree in northeastern Brazil. Fungal Biol. 2024, 128, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, E.I.; Rehner, S.A.; Samuels, G.J.; Van Bael, S.A.; Herre, E.A.; Cannon, P.F.; Chen, R.; Pang, J.; Wang, R.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.-Q.; Sha, T. Colletotrichum gloeosorioides s.l. associated with Theobroma cacao and other plants in Panamá: multilocus phylogenies distinguish host-associated pathogens from asymptomatic endophytes. Mycologia 2010, 102, 1318–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesters, C.G.C.; Hornby, D. Studies on Colletotrichum coccodes II. Alternative host tests and tomato fruit inoculations using a typical tomato root isolate. Trans Brit. Mycol. Soc. 1965, 48, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Boer, R.; Crous, P.W.; Taylor, P.W. Biology of foliar and root infection of potato plants by Colletotrichum coccodes in Australia. Phytopathol. 2014, 104, 24. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, D.D.; Crous, P.W.; Ades, P.K.; Hyde, K.D.; Taylor, P.W.J. Life styles of Colletotrichum species and implications for plant biosecurity. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2017, 31, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma-Angamarca, R.A.; Rojas, J.R.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, A.; Ruiz-González, M.X. Diversity of fungal leaf endophytes from two Coffea arabica varieties and antagonism towards Coffee Leaf Rust. Plants 2024, 13, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, G.; Cannon, P.F.; Reid, A.; Simmons, C.M. Diversity and molecular relationships of endophytic Colletotrichum isolates from the Iwokrama Forest Reserve, Guyana. Mycol. Res. 2004, 108, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshee, S.; Paulus, B.C.; Park, D.; Johnston, P.R. Diversity and distribution of fungal foliar endophytes in New Zealand Podocarpaceae. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukno, S.A.; García, V.M.; Shaw, B.D.; Thon, M.R. Root infection and systemic colonization of maize by Colletotrichum graminicola. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neill, J.C. The endophyte of Rye-Grass (Lolium perenne). N. Z. J. Sci. Tech. Section A 1940, 21, 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Goodwin, P.H.; Hsiang, T. Infection of Nicotiana species by the anthracnose fungus, Colletotrichum orbiculare. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2001, 107, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, S.; Arzanlou, M.; Torbati, M.; Eghbali, S. Novel hosts in the genus Colletotrichum and first report of C. higginsianum from Iran. Nova Hedwigia 2019, 108, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.W.; Xue, L.H.; Li, C.J. First report of Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum higginsianum on Rumex acetosa in China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, L.L.; de Almeida, L.N.; Pereira, J.O.; Neto, P.Q.C.; de Azvedo, J.L. Colletotrichum siamense, a mycovirus-carrying endophyte, as a biological control strategy for Anthracnose in Guarana plants. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2021, 64, e21200534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotoniriana, E.F.; Munaut, F.; Decock, C.; Randriamampionona, D.; Andriambololoniaina, M.; Rakotomalala, T.; Rakotonirina, E.J.; Rabeemanantsoa, C.; Cheuk, K.; Ratsimamanga, S.U.; et al. Endophytic fungi from leaves of Centella asiatica: occurrence and potential interactions within leaves. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2007, 93, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahakoon, P.W.; Brown, A.E. Host range of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides on tropical fruit crops in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2008, 40, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinovic, J.; Vucinic, Z. . Cultural characteristics, pathogenicity, and host range of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides isolated from olive plants in Montenegro. Acta Hortic. 2002, 586, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Cosoveanu, A.; Ahn, Y.; Wang, M. Identification of a novel endophytic fungus from Huperzia serrata which produces huperzine A. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 3101–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waculicz-Andrade, C.E.; Savi, D.C.; Bini, A.P.; Adamoski, D.; Goulin, E.H.; Silva Jr., G. J.; Massola Jr., N.S.; Terasawa, L.G.; Kava, V.; Glienke C. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides sensu stricto: an endophytic species or citrus pathogen in Brazil? Australas. Plant Pathol. 2017, 46, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, E.I.; Rehner, S.A.; Samuels, G.J.; Van Bael, S.A.; Herre, E.A.; Cannon, P.; Chen, R.; Pang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Peng, Y.-Q.; Sha, T. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides s.l. associated with Theobroma cacao and other plants in Panamá: multilocus phylogenies distinguish host-associated pathogens from asymptomatic endophytes. Mycologia 2017, 102, 1318–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.; Yang, Z.-D.; Chen, X.-W.; Zhou, S.-Y.; Yu, H.-T.; Sun, J.-Y.; Yao, X.-J.; Wang, Y.-G.; Xue, H.-Y. Colletotrilactam A-D, novel lactams from Colletotrichum gloeosporioides GT-7, a fungal endophyte of Uncaria rhynchophylla. Fitoterapia 2016, 113, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabha, A.J.; Naglot, A.; Sharma, G.D.; Gogoi, H.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Shreemali, D.D.; Veer, V. Morphological and molecular diversity of endophytic Colletotrichum gloeosporioides from tea plant, Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze of Assam, India. J. Genet. Eng. Biotech. 2016, 14, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Plant Health (PLH); Bragard, C.; Dehnn-Schmutz, K.; Di Serio, F.; Gonthier, P.; Jacques, M.-A.; Miret, J.A.J.; Justesen, A.F.; MacLeod, A.; Magnusson, C.S.; et al. Pest categorisation of Colletotrichum fructicola. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06803. [Google Scholar]

- Prihastuti, H.; Cai, L.; Chen, H.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Hyde, K.D. Characterization of Colletotrichum species associated with coffee berries in northern Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2009, 39, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Amaral, A.O.; Ferreira, A.F.T.A.F.; Bentes, J.L.S. Fungal endophytic community associated with Hevea spp.: diversity, enzymatic activity, and biocontrol potential. Bra. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Nontachaiyapoom, S.; Jayawardena, R.S.; Yde, K.D.; Gentekaki, E.; Zhou, S.; Qian, Y.; Wen, T.; Kang, J. Endophytic Colletotrichum species from Dendrobium spp. in China and Northern Thailand. MycoKeys 2018, 43, 23–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze-Lefert, P.; Panstruga, R. A molecular evolutionary concept connecting nonhost resistance, pathogen host range, and pathogen speciation. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C. E.; Moury, B. Revisiting the concept of host range of plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019, 57, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-J.; van der Does, H.C.; Borkovich, K.A.; Coleman, J.J.; Daboussi, M.-J.; Di Pietro, A.; Dufresne, M.; Freitag, M.; Grabherr, M.; Henrissat, B.; et al. Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature, 2010, 464, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaele, S.; Farrer, R.A.; Cano, L.M.; Studholme, D.J.; MacLean, D.; Thines, M.; Jiang, R.H.Y.; Zody, M.C.; Kunjeti, S.G.; Donofrio, N.M.; et al. . Genome evolution following host jumps in the Irish Potato Famine pathogen lineage. Science 2010, 330, 1540–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, Y.; Vy, T.T.P.; Yoshida, K.; Asano, H.; Mitsuoka, C.; Asuke, S.; Anh, V.L.; Cumagun, C.J.R.; Chuma, I.; Terauchi, R.; et al. Evolution of the wheat blast fungus through functional losses in a host specificity determinant. Science 2017, 357, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, F.E.; Sánchez-Vallet, A.; McDonald, B.A.; Croll, D. . A fungal wheat pathogen evolved host specialization by extensive chromosomal rearrangements. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, P.F.; Damm, U.; Johnston, P.R.; Weir, B.S. Colletotrichum - current status and future directions. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 181–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhinhas, P.; Baroncelli, R. Colletotrichum species and complexes: geographic distribution, host range and conservation status. Fungal Divers. 2021, 110, 109–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, R.J.; Thon, M.R.; Hacquard, S.; Amyotte, S.G.; Kleeman, J.; Torres, M.F.; Damm, U.; Buiate, E.A.; Epstein, L.; Alkan, N.; et al. Lifestyle transitions in plant pathogenic Colletotrichum fungi deciphered by genome and transcriptome analyses. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, P.; Ikeda, K.; Irieda, H.; Narusaka, M.; O’Connell, R.J.; Narusaka, Y.; Takano, Y.; Kubo, Y.; Shirasu, K. . Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal the hemibiotrophic stage shift of Colletotrichum fungi. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 1236–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusch, S.; Larrouy, J.; Ibrahim, H.M.M.; Mounichetty, S.; Gasset, N.; Navaud, O.; Mbengue, M.; Zanchetta, C.; Lopez-Roques, C.; Donnadieu, C.; et al. Transcriptional response to host chemical cues underpins the expansion of host range in a fungal plant pathogen lineage. ISME J. 2022, 16, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, P.; Narusaka, M.; Kumakura, N.; Tsushima, A.; Takano, Y.; Narusaka, Y.; Shirasu, K. Genus-wide comparative genome analyses of Colletotrichum species reveal specific gene family losses and gains during adaptation to specific infection lifestyles. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016, 8, 1467–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, P.; Hiroyama, R.; Tsushima, A.; Masuda, S.; Shibata, A.; Ueno, A.; Kumakura, N.; Narusaka, M.; Hoat, T. X.; Narusaka, Y.; et al. . Telomeres and a repeat-rich chromosome encode effector gene clusters in plant pathogenic Colletotrichum fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 6004–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsushima, A.; Gan, P.; Kumakura, N.; Narusaka, M.; Takano, Y.; Yoshihiro, N.; Shirasu, K. Genomic plasticity mediated by transposable elements in the plant pathogenic fungus Colletotrichum higginsianum. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallery, J.-F.; Lapalu, N.; Zampounis, A.; Pigné, S.; Luyten, I.; Amselem, J.; Wittenberg, A.H.J.; Zhou, S.; de Queiroz, M.V.; Robin, G.P.; et al. Gapless genome assembly of Colletotrichum higginsianum reveals chromosome structure and association of transposable elements with secondary metabolite gene clusters. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroncelli, R.; Cobo-Díaz, J.F.; Benocci, T.; Peng, M.; Battaglia, E.; Haridas, S.; Andrepoulos, W.; LaButti, K.; Pangilinan, J.; Lipzen, A.; et al. Genome evolution and transcriptome plasticity is associated with adaptation to monocot and dicot plants in Colletotrichum fungi. GigaScience 2024, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rech, G.E.; Sanz-Martín, J.M.; Anisimova, M.; Sukno, S.A.; Thon, M.R. Natural selection on coding and noncoding DNA sequences is associated with virulence genes in a plant pathogenic fungus. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 2368–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Phuong Vy, T.T.; Singkaravanit-Ogawa, S.; Zhang, R.; Yamada, K.; Ogawa, T.; Ishizuka, J.; Narusaka, Y.; Takano, Y. Selective deployment of virulence effectors correlates with host specificity in a fungal plant pathogen. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1578–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, P.S.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J. The biology of Colletotrichum acutatum. Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid 2004, 61, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Zhong, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Stukenbrock, E.H.; Tang, B.; Yang, N.; Baroncelli, R.; Peng, L.; Liu, Z.; He, X.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Z. Loss of the accessory chromosome converts a pathogenic tree-root fungus into a mutualistic endophyte. Plant Comm. 2023, 4, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Cai, J.; Shi, T.; Zheng, X.; Huang, G. Pathogenic adaptations revealed by comparative genome analysis of two Colletotrichum spp., the causal agent of anthracnose in rubber tree. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1484. [Google Scholar]

- Khodadadi, F.; Luciano-Rosario, D.; Gottschalk, C.; Jurick II, W.M.; Aćimović, S.G. Unveiling the arsenal of apple bitter rot fungi: comparative genomics identifies candidate effectors, CAZymes, and biosynthetic gene clusters in Colletotrichum species. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkemande, J.A.; Hohmann, P.; Messmer, M.M.; Barraclough, T.G. Comparative genomics reveals sources of genetic variability in the asexual plant pathogen Colletotrichum lupini. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2024, 25, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, C.; Yang, H.; Kuang, R.; Liu, K.; Huang, B.; Wei, Y. Comparative transcriptomics and genomic analyses reveal differential gene expression related to Colletotrichum brevisporum resistance in papaya (Carica papaya L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1038598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Cai, T.; Yang, X.; Dai, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhang, P.; Li, P.; Wang, C.; Liu, N.; Li, B.; Lian, S. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals significant differences in gene expression between pathogens of apple Glomerella leaf spot and apple bitter rot. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelos-Martínez, M.I.; Cano-Camacho, H.; Díaz-Tapia, K.M.; Simpson, J.; López-Romero, E.; Zavala-Páramo, M.G. Comparative genomic analyses of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum pathotypes with different virulence levels and lifestyles. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorianinova, E.M.; Sigova, E.A.; Mallaev, T.D.; Rozhmina, T.A.; Kudryavtsveva, L.P.; Novakovskiy, R.O.; Turba, A.A.; Zhernova, D.A.; Borkhert, E.V.; Pushkova, E.N.; Melnikova, N.V.; Dmitriev, A.A. Comparative genomic analysis of Colletotrichum lini strains with different virulence on flax. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, D.-K.; Chuang, S.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chao, Y.-T.; Lu, M.-Y.J.; Lee, M.-H.; Shih, M.-C. Comparative genomics of three Colletotrichum scovillei strains and genetic analysis revealed genes involved in fungal growth and virulence on chili pepper. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 818291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, R.J.; Thon, M.R.; Hacquard, S.; Amyotte, S.G.; Kleeman, J.; Torres, M.F.; Damm, U.; Buiate, E.A.; Epstein, L.; Alkan, N.; et al. Lifestyle transitions in plant pathogenic Colletotrichum fungi deciphered by genome and transcriptome analyses. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.-F.; Hao, Z.; Wang, P.; Lu, Y.; Xue, L.-J.; Wei, G.; Tian, Y.; Hu, B.; Xu, H.; Shi, J.; Cheng, T.; Wang, G.; Yi, Y.; Chen, J. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides isolated from Liriodendron leaves. Phytopathol. 2020, 110, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacquard, S.; Kracher, B.; Hiruma, K.; Münch, P.C.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Thon, M.R.; Weimann, A.; Damm, U.; Dallery, J.-F.; Hainaut, M.; et al. Survival trade-offs in plant roots during colonization by closely related beneficial and pathogenic fungi. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, P.F.; Damm, U.; Johnston, P.R.; Weir, B.S. Colletotrichum - current status and future directions. Stud. Mycol. 2012, 73, 181–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawardena, R.S.; Hyde, K.D.; Damm, U.; Cai, L.; Liu, M.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, W.S.; Yan, J.Y. Notes on currently accepted species of Colletotrichum. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 1192–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujimatsu, R.; Takino, J.; Nakamura, M.; Haba, H.; Minami, A.; Hiruma, K. A fungal transcription factor BOT6 facilitates the transition of a beneficial root fungus into an adapted anthracnose pathogen. 2024, submitted.

- Lu, H.; Zou, W.X.; Meng, J.C.; Hu, J.; Tan, R.X. New bioactive metabolites produced by Colletotrichum sp., an endophytic fungus in Artemisia annua. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-González, S. ; González-Sanz, C; González-Bodi, S.; Brunner, P.M.F.; Sacristán, S. Plant Growth Promoting fungal endophyte Colletotrichum tofieldiae Ct0861 reduces mycotoxigenic Aspergillus fungi in maize grains. bioRxiv.

- Chandini; Kumar, R.; Kumar, R.; Prakash, O. The impact of chemical fertilizers on our environment and ecosystem. In Research Trends in Environmental Sciences, 2nd ed.; Sharma, P., Ed.; AkiNik Publications: New Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, S.; Srivastava, P.; Devi, R.S.; Bhadouria, R. Influence of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides on soil health and soil microbiology. In Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment, and Remediation; Prasad, M.N.V., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2020; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Berruti, A.; Lumini, E.; Balestrini, R.; Bianciotto, V. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as natural biofertilizers: let’s benefit from past successes. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, I.; Ruiz, M.; Fernández, C.; Peña, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Sanders, I.R. The in vitro mass-produced model mycorrhizal fungus, Rhizophagus irregularis, significantly increases yields of the globally important food security crop cassava. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reducing the allelopathic effect of Parthenium hysterophorus L. on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by Pseudomonas putida. Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 66, 155–165. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-D.; Li, Z.-J.; Zhao, J.-W.; Sun, J.-H.; Yang, L.-J.; Shu, Z.-M. Secondary metabolites and PI3K inhibitory activity of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, a fungal endophyte of Uncaria rhynchophylla. Curr. Micorbiol. 2019, 76, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-X.; Tan, H.-B.; Chen, Y.-C.; Li, S.-N.; Li, H.-H.; Zhang, W.-M. Secondary metabolites from the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides A12, an endophytic fungus derived from Aquilaria sinensis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 32, 2360–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Xue, M.; Shen, Z.; Jia, X.; Hou, X.; Lai, D.; Zhou, L. Phytotoxic secondary metabolites from fungi. Toxins, 2021, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirrenberg, A.; Göbel, C.; Grond, S.; Czempinski, N.; Ratzinger, A.; Karlovsky, P.; Santos, P.; Feussner, I.; Pawlowski, K. Piriformospora indica affects plant growth by auxin production. Physiol. Plant. 2007, 131, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.N.; Higa, T.; Shiina, A.; Devi Utami, Y.; Hiruma, K. Exploring the roles of fungal-derived secondary metabolites in plant-fungal interactions. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2023, 125, 102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Traw, M.B.; Chen, J.Q.; Kreitman, M.; Bergelson, J. Fitness costs of R-gene-mediated resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 2003, 423, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, L.A.; Ridout, C.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Leach, J.E.; Leung, H. Plant-pathogen interactions: disease resistance in modern agriculture. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuthman, D.D.; Leonard, K.J.; Miller-Garvin, J. Breeding crops for durable resistance to disease. Adv. Agron. 2007, 319–367. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.-B.; Dong, Y.-W.; Hao, G.-F. Virulence factor xyloglucanase is a potential biochemical target for fungicide development. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 10483–10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Materatski, P.; Varanda, C.; Carvalho, T.; Dias, A.B.; Campos, M.D.; Gomes, L.; Nobre, T.; Rei, F.; Félix, M.R. Effect of long-term fungicide applications on virulence and diversity of Colletotrichum spp. associated to olive anthracnose. Plants 2019, 8, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.M.; Usman, H.M.; Tan, Q.; Hu, J.-J.; Fan, F.; Hussain, R.; Luo, C.-X. Fungicide resistance in Colletotrichum fructicola and Colletotrichum siamense causing peach anthracnose in China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 203, 106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogério, F.; de Castro, R.R.L.; Massola Jr., N. S.M.; Boufleur, T.R.; dos Santos, R.F. Multiple resistance of Colletotrichum truncatum from soybean to QoI and MBC fungicides in Brazil. J. Phytopathol. 2024, 172, e13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.-N.; Lian, J.-P.; Qiu, D.-. .Z.; Chen, F.-R.; Du, Y.-X. Resistance risk and molecular mechanism associated with resistance to picoxystrobin in Colletotrichum truncatum and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 3681–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Ali, S.; Nawaz, A.; Bukhari, S.A.H.; Ejaz, S.; Ahmad, S. Integrated pest and disease management for better agronomic crop production. In Agronomic Crops; Hasanuzzaman, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 385–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kolainis, S.; Koletti, A.; Lykogianni, M.; Karamanou, D.; Gkizi, D.; Tjamos, S.E.; Paraskeuopoulos, A.; Aliferis, K.A. An integrated approach to improve plant protection against olive anthracnose caused by the Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.H.; Greenblatt, G.A. The inhibition of melanin biosynthetic reactions in Pyricularia oryzae by compounds that prevent rice blast disease. Exp. Mycol. 1988, 12, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.J.; Ferrari, M.A.; Roach, D.H.; Money, N.P. Penetration of hard substrates by a fungus employing enormous turgor pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1991, 88, 11281–11284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, J.C.; McCormack, B.J.; Smirnoff, N.; Talbot, N.J. Glycerol generates turgor in rice blast. Nature 1997, 389, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Furusawa, I.; Yamamoto, M. Melanin biosynthesis as a prerequisite for penetration by appressoria of Colletotrichum lagenarium: site of inhibition by melanin-inhibiting fungicides and their action on appressoria. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1985, 23, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Ray, P. Mycoherbicides for the noxious meddlesome: can Colletotrichum be a budding candidate? Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 754048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditommaso, A.; Watson, A.K. Impact of a fungal pathogen, Colletotrichum coccodes on growth and competitive ability of Abutilon theophrasti. New Phytol. 1995, 131, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyette, C.D.; Abbas, H.K.; Johnson, B.; Hoagland, R.E.; Weaver, M.A. Biological control of the weed Sesbania exaltata using a microsclerotia formulation of the bioherbicide Colletotrichum truncatum. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 2672–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyette, C.D. Host range and virulence of Colletotrichum truncatum, a potential mycoherbicide for hemp sesbania (Sesbania exaltata). Plant Dis. 1991, 75, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).