Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

26 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish Husbandry

2.2. Pure CBD

2.3. Cannabis Extractions

2.4. Seizure Assay

2.5. Video Tracking and Analysis

2.6. Characterizing Extract's Chemical Composition

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Effects

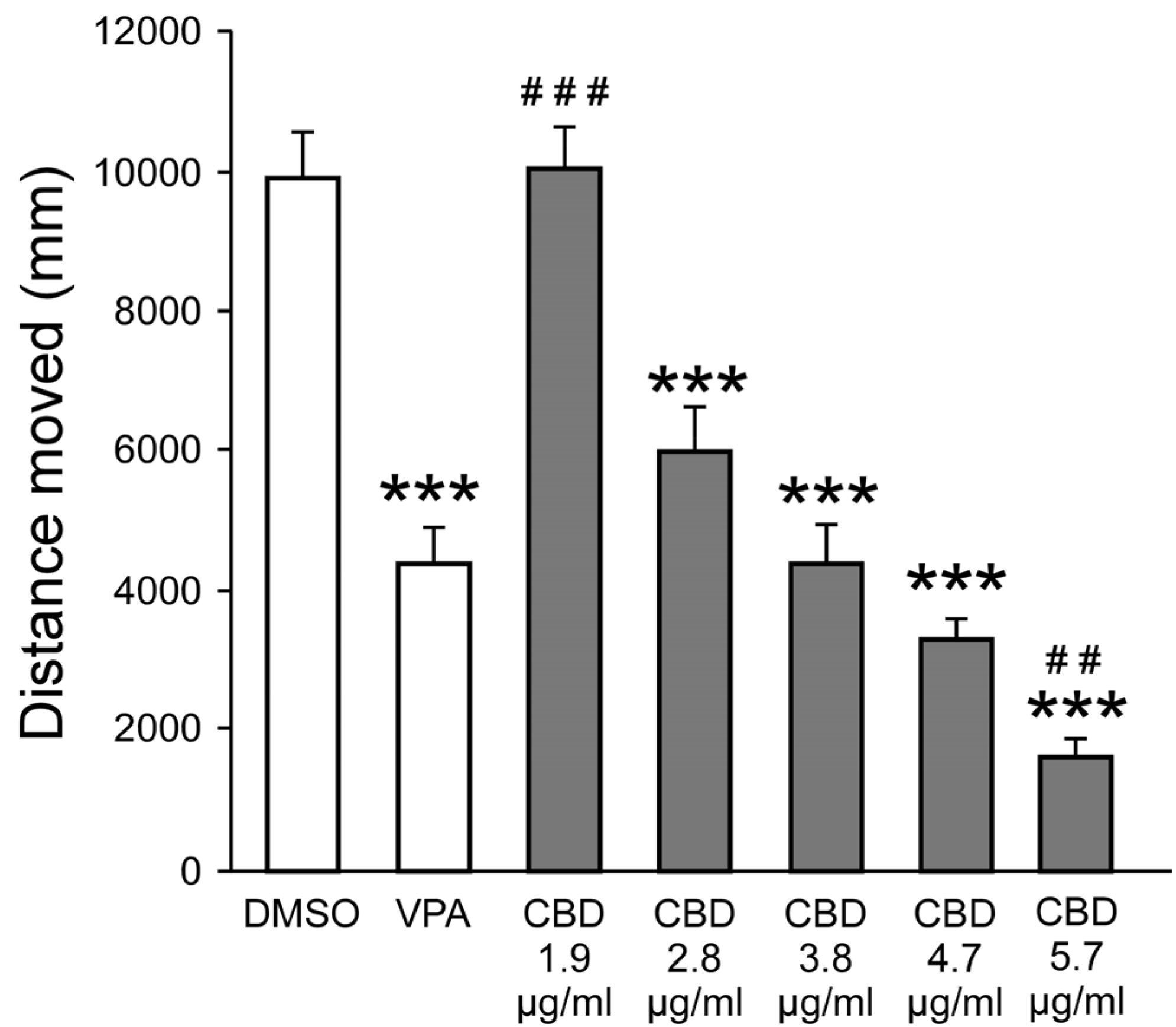

3.1.1. CBD Reduce PTZ-Induced Hyperactivity

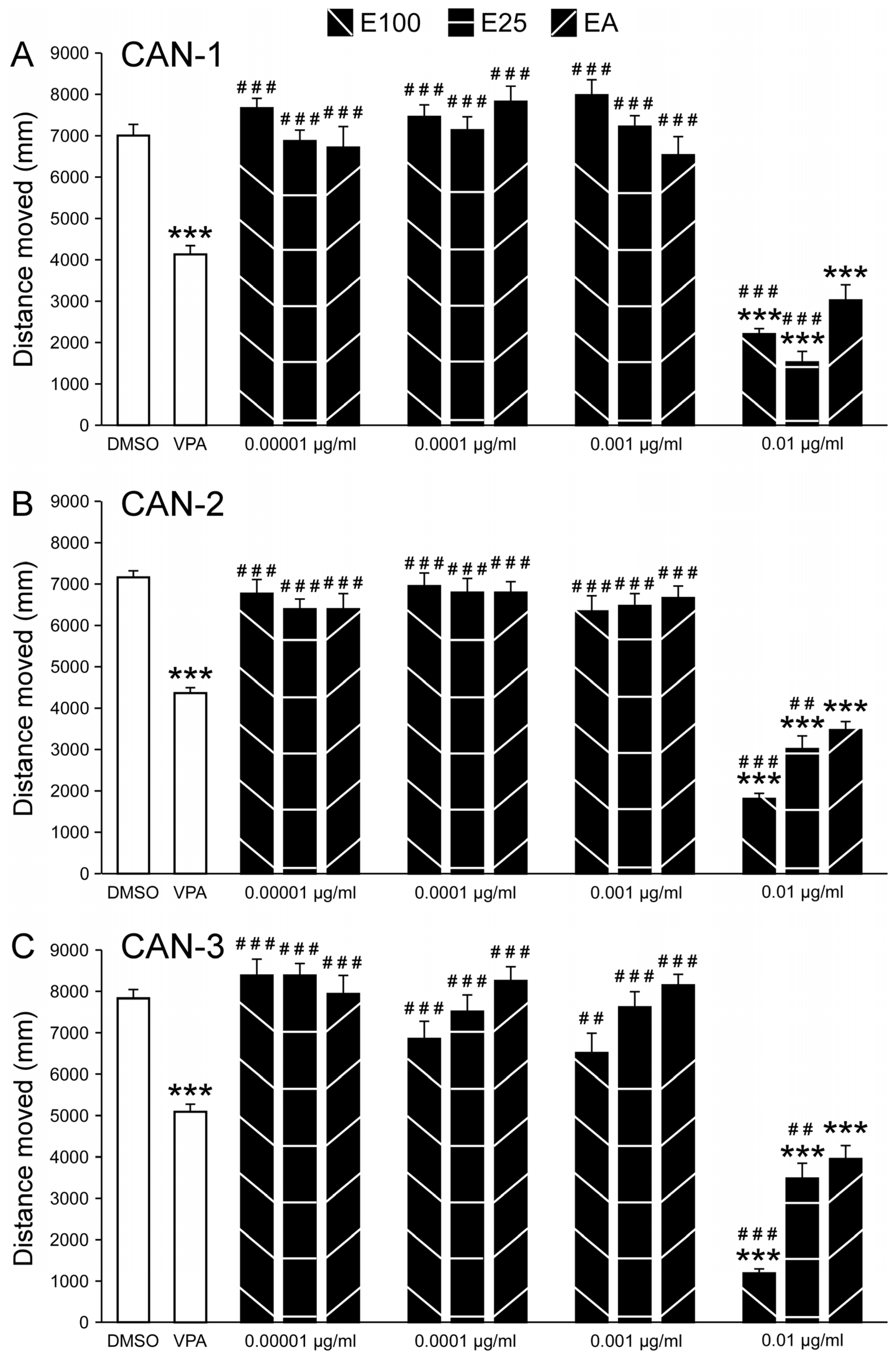

3.1.2. Extracts Reduce PTZ-Induced Hyperactivity

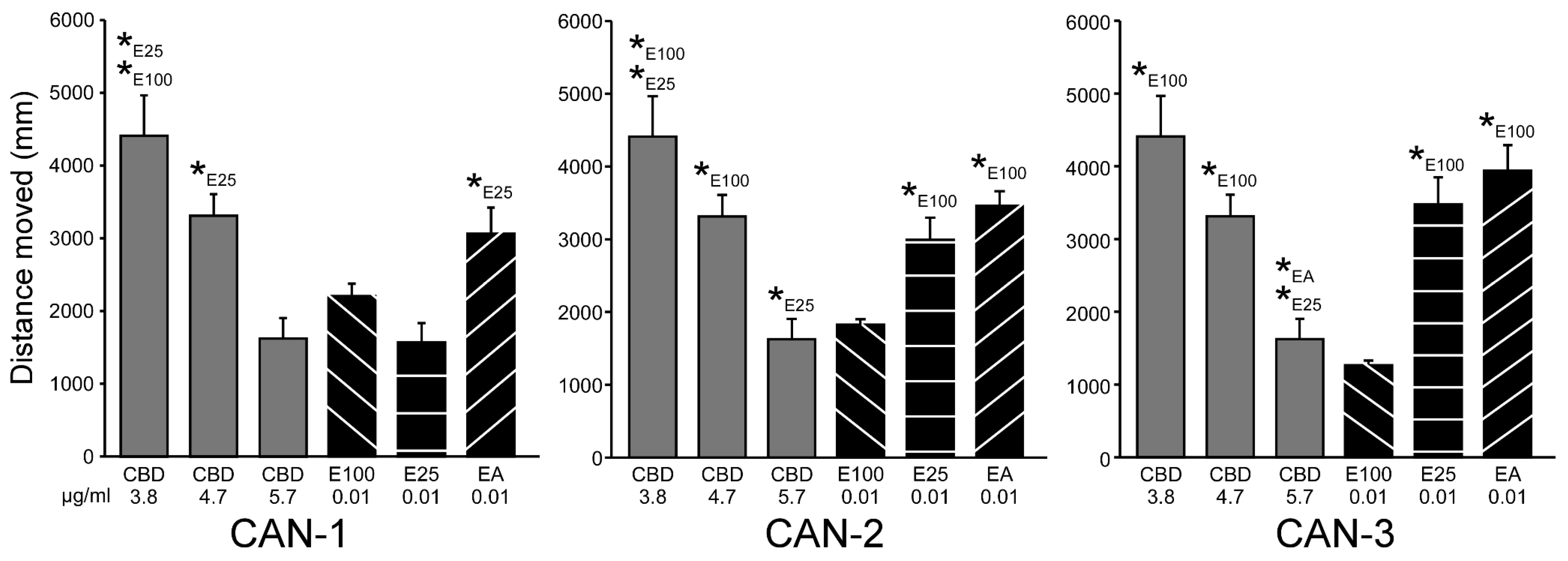

3.1.3. Comparing Effective CBD and Extracts Concentrations

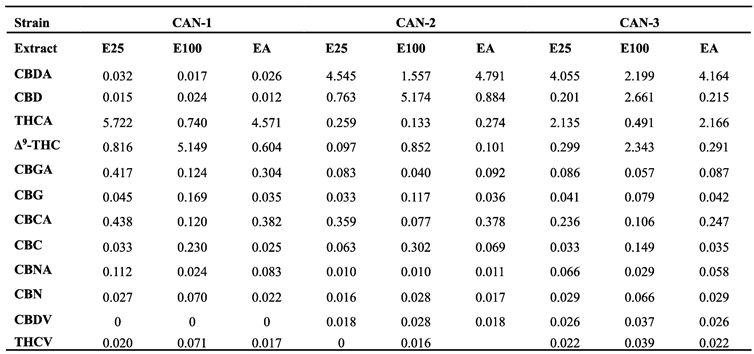

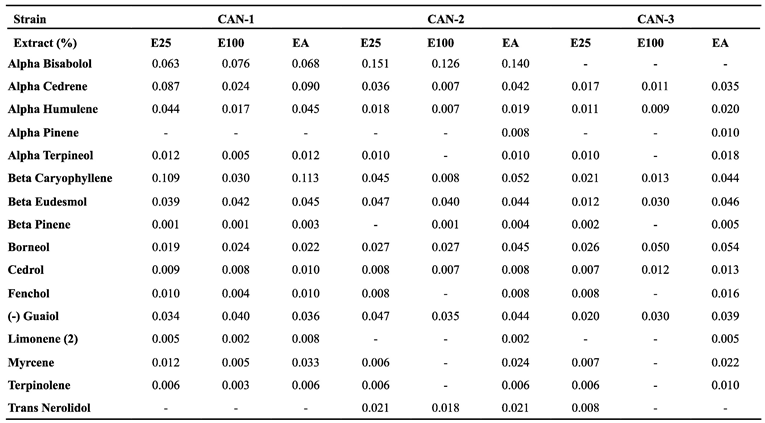

3.2. Extract profiles

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fine, A.; Wirrell, E.C. Seizures in Children. Pediatrics In Review 2020, 41, 321–347. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Epilepsy: A Public Health Imperative Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/epilepsy-a-public-health-imperative (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Singh, G.; Sander, J.W. The Global Burden of Epilepsy Report: Implications for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Epilepsy & Behavior 2020, 105, 106949. [CrossRef]

- Engel, J. Seizures and Epilepsy; OUP USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-532854-7.

- Sirven, J.I. Epilepsy: A Spectrum Disorder. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015, 5, a022848. [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, R.; Marini, C.; Mantegazza, M. Genetic Epilepsy Syndromes Without Structural Brain Abnormalities: Clinical Features and Experimental Models. Neurotherapeutics 2014, 11, 269–285. [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Vezzani, A.; O’Brien, T.J.; Jette, N.; Scheffer, I.E.; de Curtis, M.; Perucca, P. Epilepsy (Primer). Nature Reviews: Disease Primers 2018, 4, 18024. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.-M.; Britsch, S. Molecular Genetics of Acquired Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 669. [CrossRef]

- Gierbolini, J.; Giarratano, M.; Benbadis, S.R. Carbamazepine-Related Antiepileptic Drugs for the Treatment of Epilepsy - a Comparative Review. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2016, 17, 885–888. [CrossRef]

- Werner, F.-M.; Coveñas, R. Naturally Occurring and Exogenous Benzodiazepines in Epilepsy: An Update. In Naturally Occurring Benzodiazepines, Endozepines, and their Receptors; CRC Press, 2021 ISBN 978-0-367-81437-3.

- Rogawski, M.A. Reduced Efficacy and Risk of Seizure Aggravation When Cannabidiol Is Used without Clobazam. Epilepsy Behav 2020, 103. [CrossRef]

- Abdelsayed, M.; Sokolov, S. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels: Pharmaceutical Targets via Anticonvulsants to Treat Epileptic Syndromes. Channels 2013, 7, 146–152. [CrossRef]

- Löscher, W. Basic Pharmacology of Valproate. Mol Diag Ther 2002, 16, 669–694. [CrossRef]

- Iftinca, M. Neuronal T–Type Calcium Channels: What's New? Iftinca: T–Type Channel Regulation. J Med Life 2011, 4, 126–138.

- Espinosa-Jovel, C.; Valencia, N. The Current Role of Valproic Acid in the Treatment of Epilepsy: A Glimpse into the Present of an Old Ally. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2024, 26, 393–410. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Brodie, M.J.; Liew, D.; Kwan, P. Treatment Outcomes in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy Treated With Established and New Antiepileptic Drugs: A 30-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. JAMA Neurology 2018, 75, 279–286. [CrossRef]

- Fattorusso, A.; Matricardi, S.; Mencaroni, E.; Dell’Isola, G.B.; Di Cara, G.; Striano, P.; Verrotti, A. The Pharmacoresistant Epilepsy: An Overview on Existent and New Emerging Therapies. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, E.; Köklü, B.; Ozenen, C.; Arulsamy, A.; Shaikh, M.F. Elucidating the Potential Side Effects of Current Anti-Seizure Drugs for Epilepsy. Current Neuropharmacology 2021, 19, 1865–1883. [CrossRef]

- Roullet, F.I.; Lai, J.K.Y.; Foster, J.A. In Utero Exposure to Valproic Acid and Autism — A Current Review of Clinical and Animal Studies. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 2013, 36, 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Verrotti, A.; Scaparrotta, A.; Cofini, M.; Chiarelli, F.; Tiboni, G.M. Developmental Neurotoxicity and Anticonvulsant Drugs: A Possible Link. Reproductive Toxicology 2014, 48, 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, F.F.; Gaspary, K.V.; Leite, C.E.; De Paula Cognato, G.; Bonan, C.D. Embryological Exposure to Valproic Acid Induces Social Interaction Deficits in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio): A Developmental Behavior Analysis. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 2015, 52, 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Babiec, L.; Wilkaniec, A.; Adamczyk, A. Prenatal Exposure to Valproic Acid Induces Alterations in the Expression and Activity of Purinergic Receptors in the Embryonic Rat Brain. Folia Neuropathol 2022, 60, 390–402. [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Hernández, M.G.; Villarroel-Hagemann, S.K.; Mendoza-Rodelo, I.E.; Palacios-Sánchez, L.; Gaviria-Carrillo, M.; Buitrago-Ricaurte, N.; Espinosa-Lugo, S.; Calderon-Ospina, C.-A.; Rodríguez-Quintana, J.H. Development of Antiepileptic Drugs throughout History: From Serendipity to Artificial Intelligence. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1632. [CrossRef]

- Lessman, C.A. The Developing Zebrafish (Danio Rerio): A Vertebrate Model for High-Throughput Screening of Chemical Libraries. Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews 2011, 93, 268–280. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Kannan, R.R. Zebrafish: A Potential Preclinical Model for Neurological Research in Modern Biology. In Zebrafish Model for Biomedical Research; Bhandari, P.R., Bharani, K.K., Khurana, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 321–345 ISBN 978-981-16-5217-2.

- Sierra, A.; Gröhn, O.; Pitkänen, A. Imaging Microstructural Damage and Plasticity in the Hippocampus during Epileptogenesis. Neuroscience 2015, 309, 162–172. [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, J.; Szopa, A.; Ignatiuk, K.; Świąder, K.; Serefko, A. Zebrafish as an Animal Model in Cannabinoid Research. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 10455. [CrossRef]

- Kundap, U.P.; Kumari, Y.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Zebrafish as a Model for Epilepsy-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction: A Pharmacological, Biochemical and Behavioral Approach. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Turrini, L.; Fornetto, C.; Marchetto, G.; Müllenbroich, M.C.; Tiso, N.; Vettori, A.; Resta, F.; Masi, A.; Mannaioni, G.; Pavone, F.S.; et al. Optical Mapping of Neuronal Activity during Seizures in Zebrafish. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 3025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Baraban, S.C. Network Properties Revealed during Multi-Scale Calcium Imaging of Seizure Activity in Zebrafish. eNeuro 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Burrows, D.R.W.; Samarut, É.; Liu, J.; Baraban, S.C.; Richardson, M.P.; Meyer, M.P.; Rosch, R.E. Imaging Epilepsy in Larval Zebrafish. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 2020, 24, 70–80. [CrossRef]

- Milder, P.C.; Zybura, A.S.; Cummins, T.R.; Marrs, J.A. Neural Activity Correlates With Behavior Effects of Anti-Seizure Drugs Efficacy Using the Zebrafish Pentylenetetrazol Seizure Model. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Messina, A.; Boiti, A.; Sovrano, V.A.; Sgadò, P. Micromolar Valproic Acid Doses Preserve Survival and Induce Molecular Alterations in Neurodevelopmental Genes in Two Strains of Zebrafish Larvae. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1364. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Hernández, B.A.; Colón, L.R.; Rosa-Falero, C.; Torrado, A.; Miscalichi, N.; Ortíz, J.G.; González-Sepúlveda, L.; Pérez-Ríos, N.; Suárez-Pérez, E.; Bradsher, J.N.; et al. Reversal of Pentylenetetrazole-Altered Swimming and Neural Activity-Regulated Gene Expression in Zebrafish Larvae by Valproic Acid and Valerian Extract. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 2533–2547. [CrossRef]

- Kollipara, R.; Langille, E.; Tobin, C.; French, C.R. Phytocannabinoids Reduce Seizures in Larval Zebrafish and Affect Endocannabinoid Gene Expression. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1398. [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.; Dickson, K.E.; Carty, D.R.; Ashpole, N.M.; Willett, K.L. Cannabis Constituents Reduce Seizure Behavior in Chemically-Induced and Scn1a-Mutant Zebrafish. Epilepsy & Behavior 2020, 110, 107152. [CrossRef]

- Samarut, É.; Nixon, J.; Kundap, U.P.; Drapeau, P.; Ellis, L.D. Single and Synergistic Effects of Cannabidiol and Δ-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol on Zebrafish Models of Neuro-Hyperactivity. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Leo, A.; Russo, E.; Elia, M. Cannabidiol and Epilepsy: Rationale and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmacological Research 2016, 107, 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Lazarini-Lopes, W.; Do Val-da Silva, R.A.; da Silva-Júnior, R.M.P.; Leite, J.P.; Garcia-Cairasco, N. The Anticonvulsant Effects of Cannabidiol in Experimental Models of Epileptic Seizures: From Behavior and Mechanisms to Clinical Insights. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2020, 111, 166–182. [CrossRef]

- Thiele, E.A.; Marsh, E.D.; French, J.A.; Mazurkiewicz-Beldzinska, M.; Benbadis, S.R.; Joshi, C.; Lyons, P.D.; Taylor, A.; Roberts, C.; Sommerville, K.; et al. Cannabidiol in Patients with Seizures Associated with Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome (GWPCARE4): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1085–1096. [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Cross, J.H.; Laux, L.; Marsh, E.; Miller, I.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Thiele, E.A.; Wright, S. Trial of Cannabidiol for Drug-Resistant Seizures in the Dravet Syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 376, 2011–2020. [CrossRef]

- Ferber, S.G.; Namdar, D.; Hen-Shoval, D.; Eger, G.; Koltai, H.; Shoval, G.; Shbiro, L.; Weller, A. The "Entourage Effect": Terpenes Coupled with Cannabinoids for the Treatment of Mood Disorders and Anxiety Disorders. Current Neuropharmacology 2020, 18, 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, B.S.; Subbanna, S. Unveiling the Potential of Phytocannabinoids: Exploring Marijuana’s Lesser-Known Constituents for Neurological Disorders. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1296. [CrossRef]

- Caprioglio, D.; Amin, H.I.M.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Muñoz, E.; Appendino, G. Minor Phytocannabinoids: A Misleading Name but a Promising Opportunity for Biomedical Research. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1084. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Reis, R.; Silva, A.M.S.; Oliveira, P.A.; Cardoso, S.M. Antitumor Effects of Cannabis Sativa Bioactive Compounds on Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 764. [CrossRef]

- Peeri, H.; Koltai, H. Cannabis Biomolecule Effects on Cancer Cells and Cancer Stem Cells: Cytotoxic, Anti-Proliferative, and Anti-Migratory Activities. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 491. [CrossRef]

- Abyadeh, M.; Gupta, V.; Paulo, J.A.; Gupta, V.; Chitranshi, N.; Godinez, A.; Saks, D.; Hasan, M.; Amirkhani, A.; McKay, M.; et al. A Proteomic View of Cellular and Molecular Effects of Cannabis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1411. [CrossRef]

- André, R.; Gomes, A.P.; Pereira-Leite, C.; Marques-da-Costa, A.; Monteiro Rodrigues, L.; Sassano, M.; Rijo, P.; Costa, M. do C. The Entourage Effect in Cannabis Medicinal Products: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1543. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shabat, S.; Fride, E.; Sheskin, T.; Tamiri, T.; Rhee, M.-H.; Vogel, Z.; Bisogno, T.; De Petrocellis, L.; Di Marzo, V.; Mechoulam, R. An Entourage Effect: Inactive Endogenous Fatty Acid Glycerol Esters Enhance 2-Arachidonoyl-Glycerol Cannabinoid Activity. European Journal of Pharmacology 1998, 353, 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, K.F.; Scott, J.R.; Litinas, E.; Sisley, S.; Clauw, D.J.; Goesling, J.; Williams, D.A. Cannabis Use Preferences and Decision-Making Among a Cross-Sectional Cohort of Medical Cannabis Patients with Chronic Pain. The Journal of Pain 2019, 20, 1362–1372. [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, K.F.; Gagnier, J.J.; Matallana, L.; Williams, D.A. Cannabidiol Product Dosing and Decision-Making in a National Survey of Individuals with Fibromyalgia. The Journal of Pain 2022, 23, 45–54. [CrossRef]

- Kvamme, S.L.; Pedersen, M.M.; Rømer Thomsen, K.; Thylstrup, B. Exploring the Use of Cannabis as a Substitute for Prescription Drugs in a Convenience Sample. Harm Reduct J 2021, 18, 72. [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, C.B.; Ballard, W.W.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ullmann, B.; Schilling, T.F. Stages of Embryonic Development of the Zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics 1995, 203, 253–310. [CrossRef]

- Stella, N. THC and CBD: Similarities and Differences between Siblings. Neuron 2023, 111, 302–327. [CrossRef]

- Licitra, R.; Damiani, D.; Naef, V.; Fronte, B.; Vecchia, S.D.; Sangiacomo, C.; Marchese, M.; Santorelli, F.M. Cannabidiol Mitigates Valproic Acid-Induced Developmental Toxicity and Locomotor Behavioral Impairment in Zebrafish. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents 2023, 37, 4935–4946. [CrossRef]

- Pamplona, F.A.; da Silva, L.R.; Coan, A.C. Potential Clinical Benefits of CBD-Rich Cannabis Extracts Over Purified CBD in Treatment-Resistant Epilepsy: Observational Data Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Quispe, C.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Martorell, M.; Sharopov, F.; Tumer, T.B.; Kurt, B.; Lankatillake, C.; Docea, A.O.; Moreira, A.C.; et al. A Pharmacological Perspective on Plant-Derived Bioactive Molecules for Epilepsy. Neurochem Res 2021, 46, 2205–2225. [CrossRef]

- Challal, S.; Skiba, A.; Langlois, M.; Esguerra, C.V.; Wolfender, J.-L.; Crawford, A.D.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K. Natural Product-Derived Therapies for Treating Drug-Resistant Epilepsies: From Ethnopharmacology to Evidence-Based Medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2023, 317, 116740. [CrossRef]

- Nutt, D.J.; Phillips, L.D.; Barnes, M.P.; Brander, B.; Curran, H.V.; Fayaz, A.; Finn, D.P.; Horsted, T.; Moltke, J.; Sakal, C.; et al. A Multicriteria Decision Analysis Comparing Pharmacotherapy for Chronic Neuropathic Pain, Including Cannabinoids and Cannabis-Based Medical Products. Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research 2022, 7, 482–500. [CrossRef]

- Stueber, A.; Cuttler, C. A Large-Scale Survey of Cannabis Use for Sleep: Preferred Products and Perceived Effects in Comparison to over-the-Counter and Prescription Sleep Aids. Explor Med. 2023, 4, 709–719. [CrossRef]

- Kitdumrongthum, S.; Trachootham, D. An Individuality of Response to Cannabinoids: Challenges in Safety and Efficacy of Cannabis Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 2791. [CrossRef]

- Tzadok, M.; Uliel-Siboni, S.; Linder, I.; Kramer, U.; Epstein, O.; Menascu, S.; Nissenkorn, A.; Yosef, O.B.; Hyman, E.; Granot, D.; et al. CBD-Enriched Medical Cannabis for Intractable Pediatric Epilepsy: The Current Israeli Experience. Seizure 2016, 35, 41–44. [CrossRef]

- Ross-Munro, E.; Isikgel, E.; Fleiss, B. Evaluation of the Efficacy of a Full-Spectrum Low-THC Cannabis Plant Extract Using In Vitro Models of Inflammation and Excitotoxicity. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1434. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.; Rose, M.; Cornett, C.; Allesø, M. Decoding the Postulated Entourage Effect of Medicinal Cannabis: What It Is and What It Isn't. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2323. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).