1. Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological condition caused by abnormal and hypersynchronous brain activity, leading to recurring and unpredictable epileptic seizures. The prevalence of active epilepsy worldwide, disregarding cases in remission, is 6.38 per 1,000 people. Prevalence rates are higher in low/middle-income countries than in high-income countries, with 6.68 and 5.49 per 1,000 inhabitants, respectively, due to diverse population structures and increased exposure to risk factors, such as infectious diseases and head trauma in lower-income populations [

1].

Epilepsy treatment with

Cannabis sp. and related compounds has drawn increasing attention from researchers in recent years. Studies indicate that certain compounds from

Cannabis, such as cannabidiol (CBD), a major non-psychoactive cannabinoid, and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, THC), known for its psychoactive effects, possess antiepileptic properties, including evidence of a possible role in the treatment of pharmacoresistant epilepsy [

2]. Nonetheless, a large interindividual variability in response to cannabinoids remains a challenge in endocannabinoid system pharmacological modulation for epilepsy, emphasizing the need for further studies to better understand their potential therapeutic role [

3,

4].

The effects of THC are primarily mediated by the cannabinoid receptor-1 (CB1) in presynaptic neurons and, to a lesser extent, by the cannabinoid receptor-2 (CB2), resulting in the modulation of neurotransmitter release, particularly glutamate. Conversely, CBD has a weak interaction with CB1 and CB2, which are not critical to its central effects. Instead, CBD appears to inhibit the breakdown of anandamide, an endogenous cannabinoid, thereby prolonging its activity upon CB receptors, indirectly modulating their effects [

5].

Alternatively, CBD may stimulate the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) or antagonize the G protein-coupled receptor-55 (GPR55), targeting abnormal sodium channels, T-type calcium channels, adenosine receptors, and voltage-dependent anion-selective channel 1 (VDAC1), as well as regulating the release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [

6,

7]. While both CBD and THC show promise in epilepsy treatment, the psychoactive effects of THC due to its CB agonistic activity remain a limiting factor [

8,

9].

Astrocytes play a crucial role in the blood-brain barrier and the regulation of the extracellular milieu [

10]. They support neurite outgrowth, synaptic maturation, and plasticity, in addition to maintaining mature synapses. Astrocytes also control neurotransmitter spillover and extrasynaptic transmission by taking up glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) from the synaptic cleft, thereby modulating synaptic signaling and neurotransmitter turnover [

11]. The balance between glutamate, GABA, and glutamine regulates excitatory/inhibitory neurotransmission over the medium and long term [

12].

Under pathological conditions such as infection, trauma, ischemia, hemorrhage, or seizures, astrocytes become activated along with microglia and infiltrating leukocytes, and all of them can secrete inflammatory mediators [

13,

14]. The consequent inflammatory response triggers reactive astrogliosis, a process characterized by morphological and metabolic changes in astrocytes and altered protein expression, which has been observed in epileptic foci [

15,

16]. One of the most well-known proteins modified in reactive astrocytes is glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a component of the astrocytic cytoskeleton and a key molecular marker of astrogliosis. Several other proteins involved in ion homeostasis and neurotransmitter reuptake also undergo expression changes in epilepsy, including potassium channels [

17].

The inwardly rectifying potassium channel 4.1 (Kir4.1) is predominantly expressed in astrocytes and plays a key role in regulating extracellular potassium levels, which are crucial for neuronal excitability [

18]. By buffering the extracellular potassium increase during neuronal activity, Kir4.1 prevents excessive depolarization and supports the physiological function of neural networks [

19,

20].

The major GABA transporter-1 (GAT1) is responsible for GABA reuptake into nerve terminals and astrocytes, maintaining inhibitory neurotransmission [

21]. While GAT1 expression is higher in GABAergic nerve terminals, it is also present in astrocytes, playing a vital role in synaptic inhibition [

22,

23]. Both Kir4.1 and GAT1 are essential for neuronal communication, and their dysfunction has been implicated in the pathophysiology of epilepsy and other neurological disorders. Current research seeks to further elucidate their roles and potential as therapeutic targets in epilepsy [

24,

25].

Given these mechanisms, the present study aimed to investigate the modulation of astrocytic Kir4.1 and GAT1 expression as potential contributors to the antiseizure effects of CBD and THC solved in Licuri oil as vehicle, and their possible impact on GFAP expression. Different doses of CBD and THC, administered individually or in combination, were tested in two seizure models: (i) pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced acute seizures and (ii) PTZ-induced kindling. Kindling is widely used to mimic epileptogenesis, as repeated administration of subconvulsive doses of PTZ initially causes mild behavioral changes but eventually leads to progressive worsening of motor seizures, with the contribution of oxidation as a pathophysiological mechanism [

26].

3. Discussion

In this study, we have investigated the effects of CBD and THC nanoemulsions on animal models of acute and chronic seizures induced by PTZ. These nanoemulsions demonstrated efficacy in modulating seizures and attenuating associated brain damage, at concentrations much lower than those reported as successful in other reports [

28]. The nanometric size of the particles in these nanoemulsions suggests an optimized formulation for therapeutic action. In acute models, high doses of CBD, THC, and their combinations significantly prolonged the latency to the first generalized seizure and to death as well, indicating an antiseizure action. These treatments also resulted in decreased levels of oxidative and nitrosative stress markers in brain regions important for seizure onset. In the chronic model, that is, PTZ-induced kindling, preemptive treatment with CBD, lower dose CBD/THC combinations, and valproic acid slowed the progression of kindling acquisition, while a higher dose of CBD/THC showed no efficacy. From a behavioral standpoint, no significant differences were observed in most treated groups, except for those receiving valproic acid, indicating a cognitive deficit possibly related to the epilepsy model not approached by the treatments. Nonetheless, a relationship of the cognitive deficit with the cannabinoid treatment per se cannot be ruled out, given that behavioral deficit was seen also in the group treated with CBD/THC nanoemulsions and no PTZ. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry findings indicate neurochemical changes, with a decreased expression of GFAP and GAT1 and an increased expression of Kir4.1 in cannabinoid-treated animals, which may represent possible mechanisms of the disease improvement afforded by the cannabinoid nanoemulsions.

The advantage of nanoemulsions, as demonstrated in this study, lies in their effective absorption and the ability to cross biological barriers including the blood-brain barrier, enhancing the bioavailability of the tested compounds. Nakano et al. [

29] developed an innovative nanoemulsion formulation to improve the intestinal absorption of CBD, highlighting the potential of these approaches in epilepsy-related models and other neurological conditions. Additionally, Ahmed et al. [

30] created a CBD nanoemulsion for direct nasal-to-brain delivery, enhancing drug bioavailability and addressing the specific organic site of action. Furthermore, El Sohly et al. [

31] demonstrated that an UltraShear nanoemulsion of CBD significantly increased its oral-gastrointestinal bioavailability in rats, offering a promising alternative for delivering cannabinoids with enhanced efficacy, thus supporting our findings.

These results are consistent with findings from other researchers who have investigated the effects of

Cannabis compounds in epilepsy models. For example, Namvar et al. [

32] corroborated the effectiveness of

Cannabis sativa extract at a dose of 800 mg/kg in rats in modulating PTZ-induced seizures but did not delve deeply into behavioral effects. Additionally, Lu et al. [

33] showed that CBD treatment improves epilepsy by acting on metabolism and calcium signaling pathways.

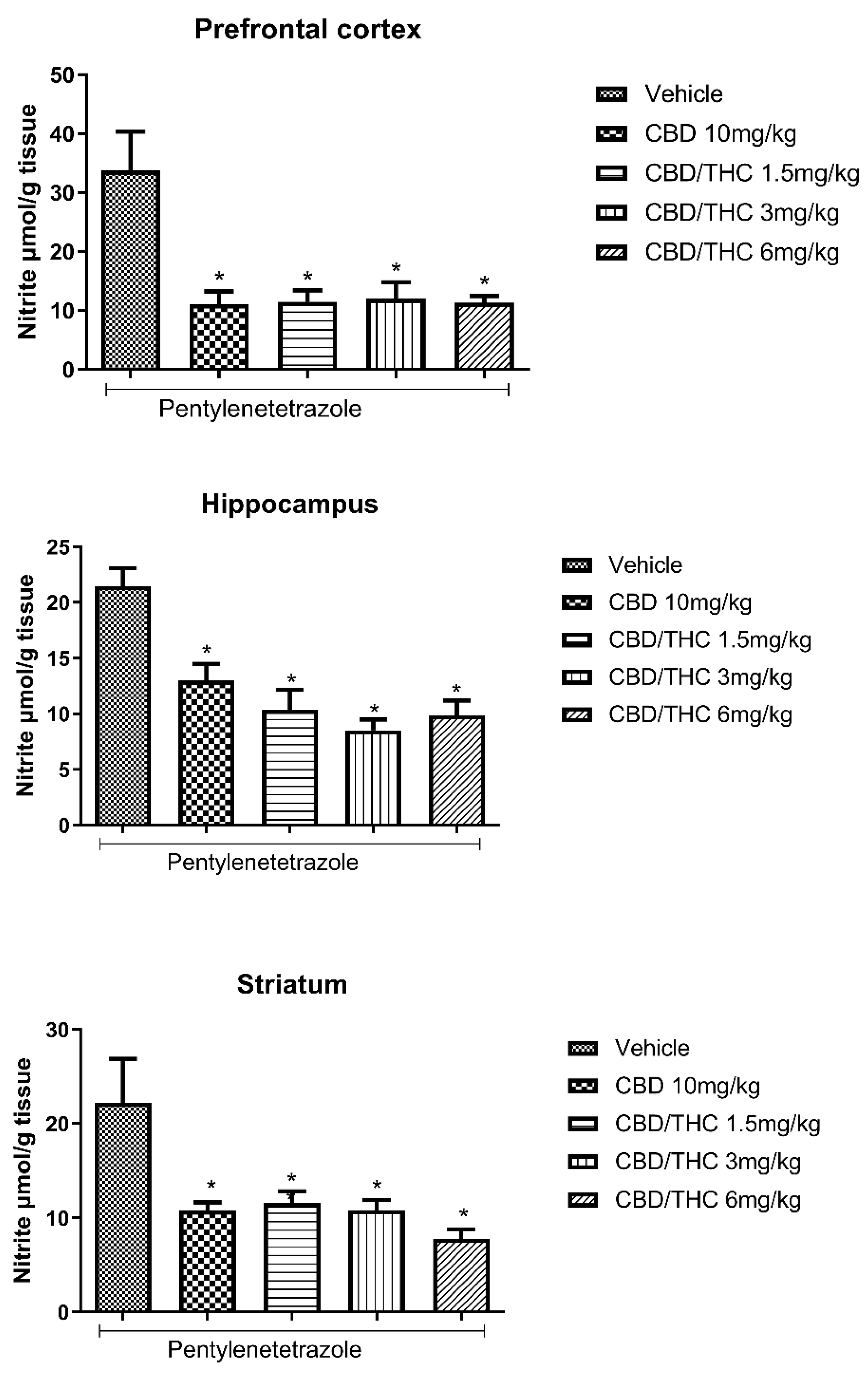

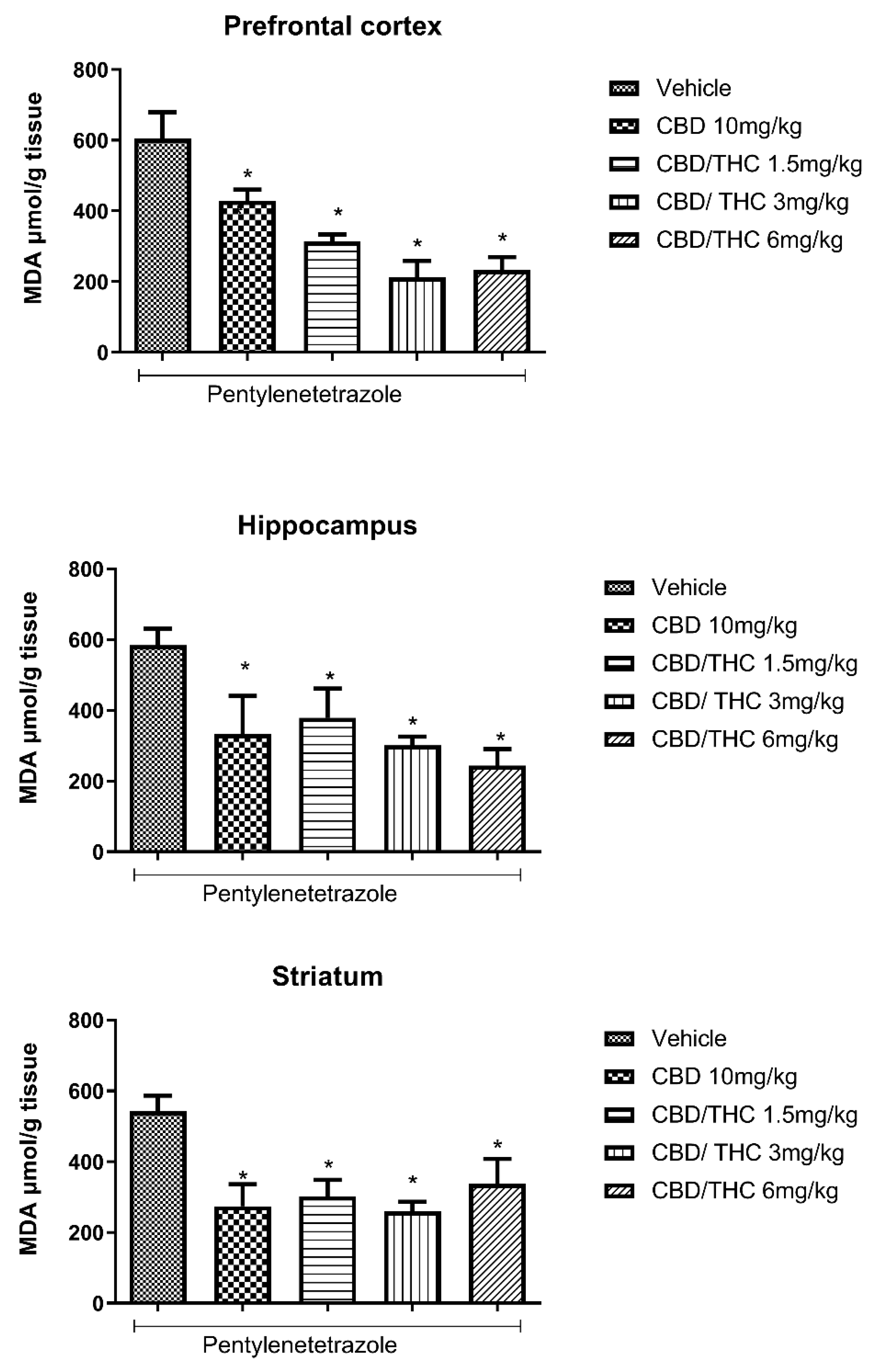

During seizures, an increase in levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and nitrate/nitrite is observed, which indicates nitrosative and oxidative stress. This increase results from intense neuronal activity in the brain, leading to high oxygen consumption and excessive production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species [

34,

35]. MDA, a byproduct of lipid peroxidation, reflects damage to cell membranes caused by the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acid residues of membrane phospholipids. Simultaneously, the elevation of nitrate/nitrite, derived from nitric oxide metabolism, points to increased nitrosative stress [

36,

37]. Both oxidative and nitrosative stresses are known to be closely related to neuroinflammation [38-40]. This oxidative environment not only reflects cellular damage caused by seizures but also can contribute to epilepsy progression by altering neuronal and glial function and metabolism, thus increasing susceptibility to future seizures [

41,

42]. The present study showed that the levels of oxidative and nitrosative stress markers, MDA and nitrate/nitrite, in the groups pretreated with CBD and THC nanoemulsions were significantly lower than in the vehicle-pretreated group, suggesting that the antioxidative properties of the cannabinoids tested may have contributed to some extent to their antiseizure effect.

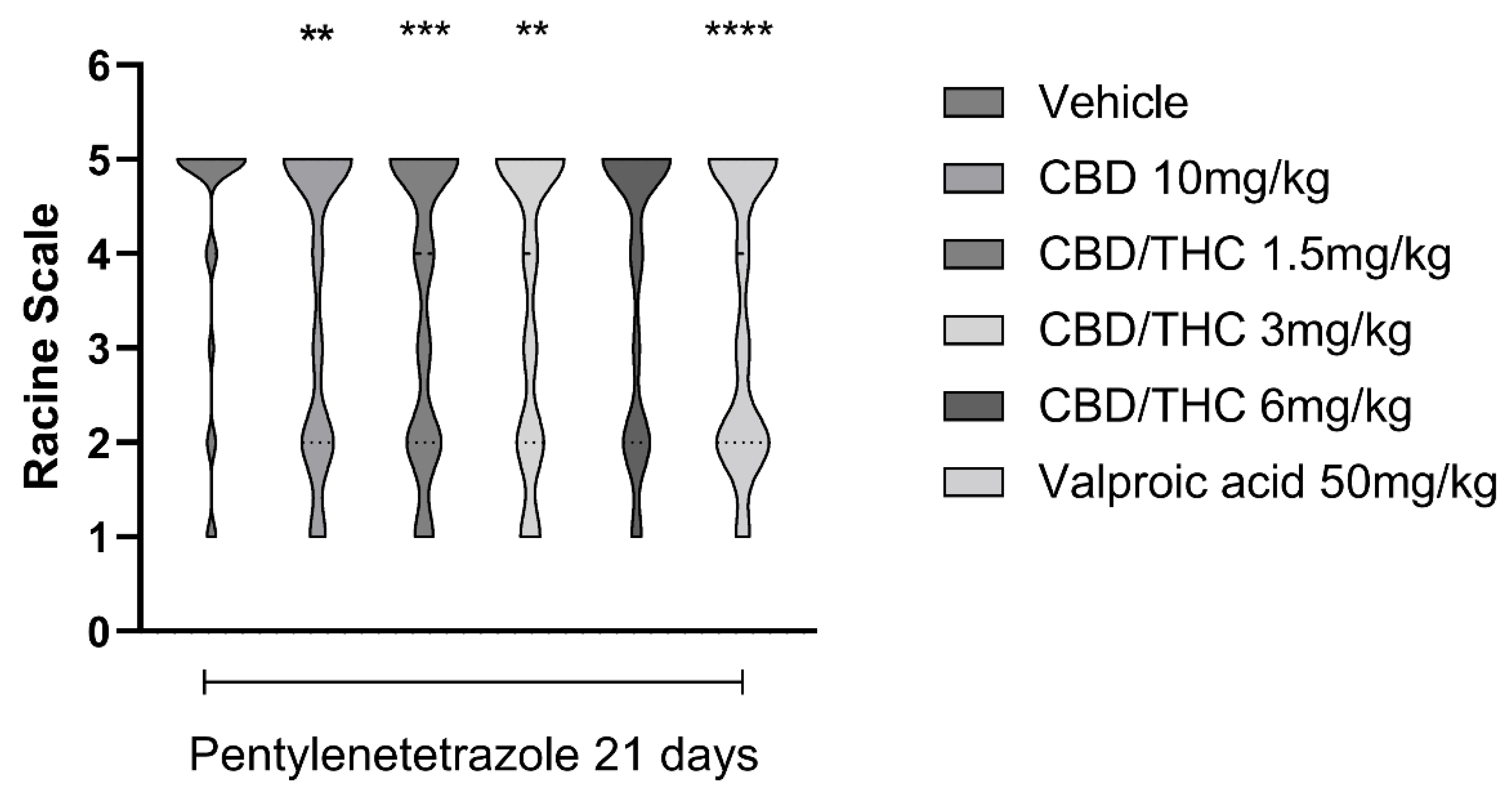

Regarding the PTZ-induced kindling model, which emulates chronic epileptogenesis, a delaying effect of CBD and CBD/THC combinations on kindling acquisition was observed, highlighting the potential of these compounds in modifying the progression of epilepsy. The use of

Cannabis compounds for epilepsy has drawn attention, especially after studies like those of Anderson et al. [

28], which emphasized the therapeutic potential of CBD and THC in epilepsy models, including Dravet syndrome. Together, these studies complement and expand on our findings, pointing to several approaches and mechanisms by which

Cannabis compounds can be useful in treating seizure-related disorders.

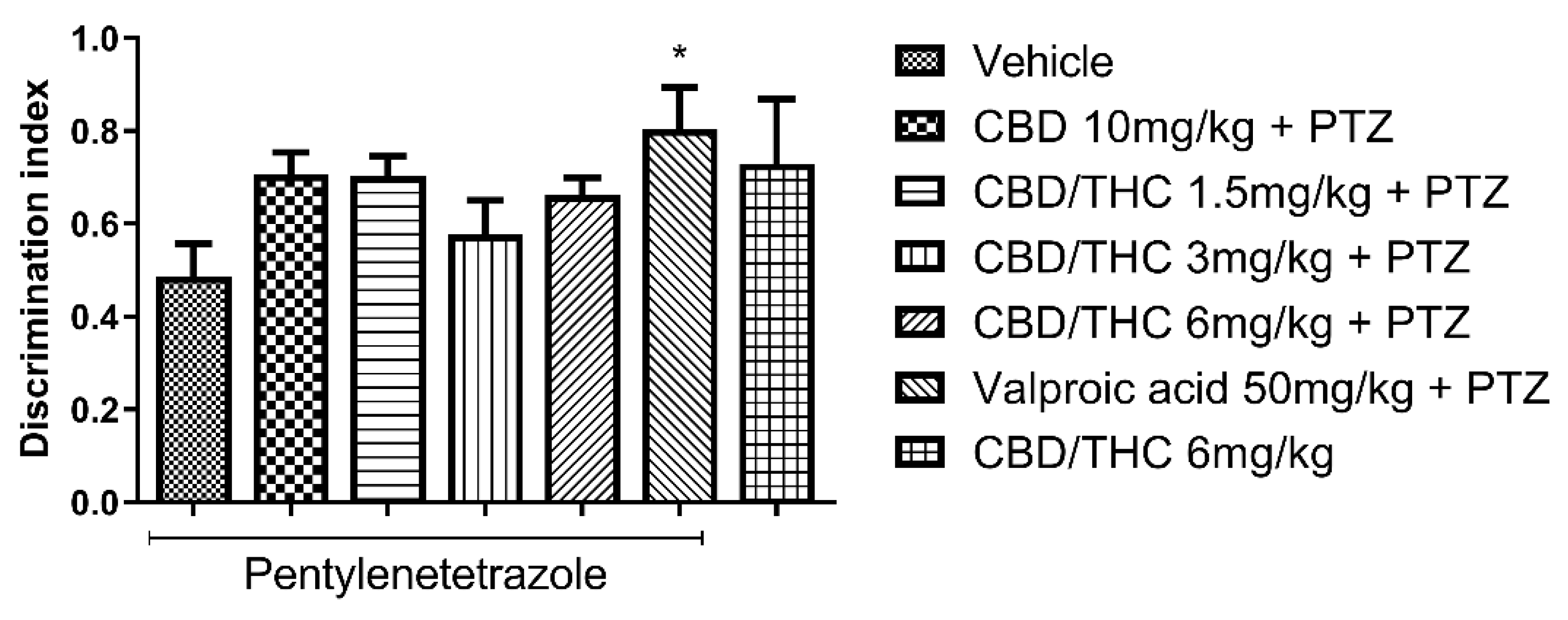

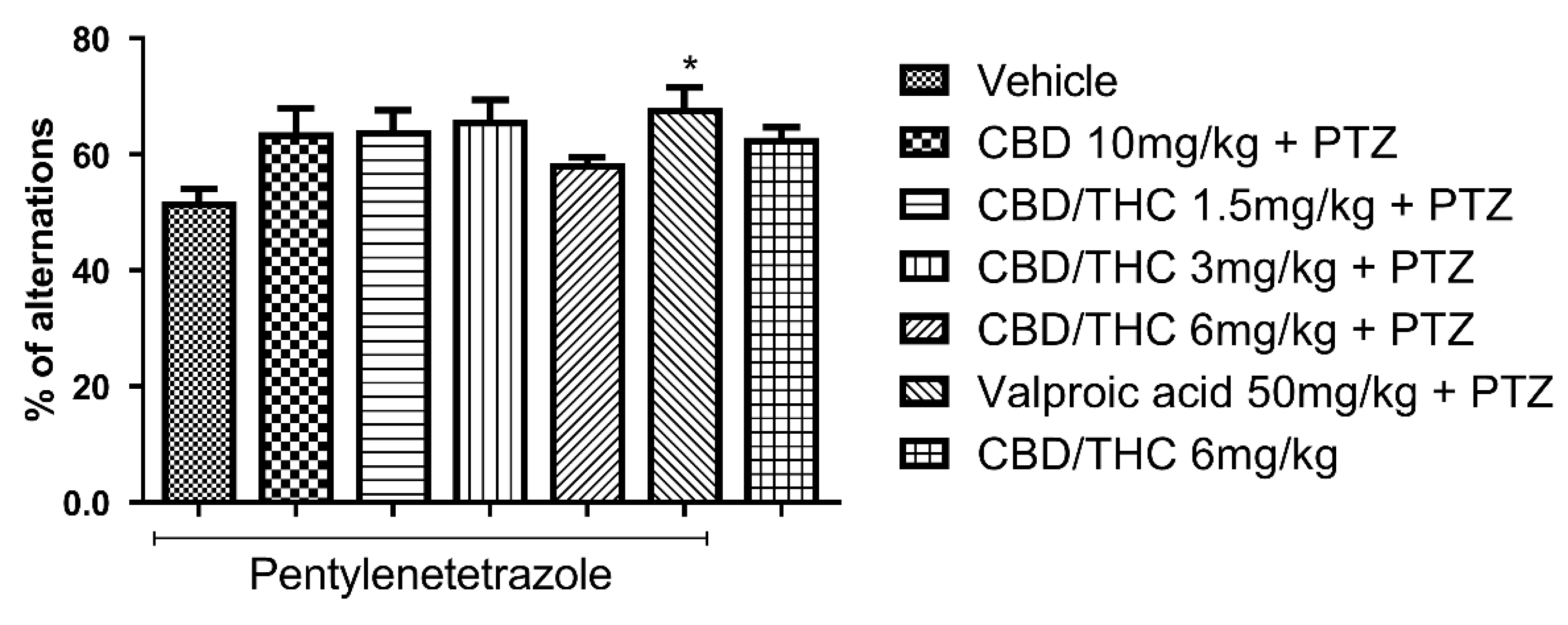

CBD shows beneficial cognitive effects in animal models of, and neutral or beneficial cognitive effects in humans with epilepsy [

43]. Nevertheless, studies such as that of Gáll et al. [

44], which analyzed chronic CBD treatment in the PTZ-induced kindling model, found that while CBD increased latency to the first seizure and reduced mortality, behavioral changes such as decreased vertical exploration and discrimination in the novel ORT were also observed. Also, CBD improved cognitive deficit in models of fetal alcoholic exposure disorder [

45], glutamatergic NMDA antagonist-induced schizophrenia-like behavior [

46], scopolamine-induced memory impairment [

47] and Alzheimer disease [

48], in the latter case associated with a shift from M1 to M2 phenotype of activated hippocampal microglia. Furthermore, a selective agonist of the CB2 receptor, which is upregulated in Alzheimer disease in humans and animal models, improved cognitive deficit in an animal model of the disease [

49]. In our study, groups treated with cannabinoid nanoemulsions, even without PTZ, failed to show cognitive improvement. The behavioral tests ORT and Y-maze did not show significant differences in most groups, except for the valproic acid-pretreated group. This associated with the fact that a sham-kindled group was not included in analyses prevents the inference of a possible cognitive worsening induced by cannabinoids. Therefore, a definitive assertion on the effect of cannabinoids in this model is not possible.

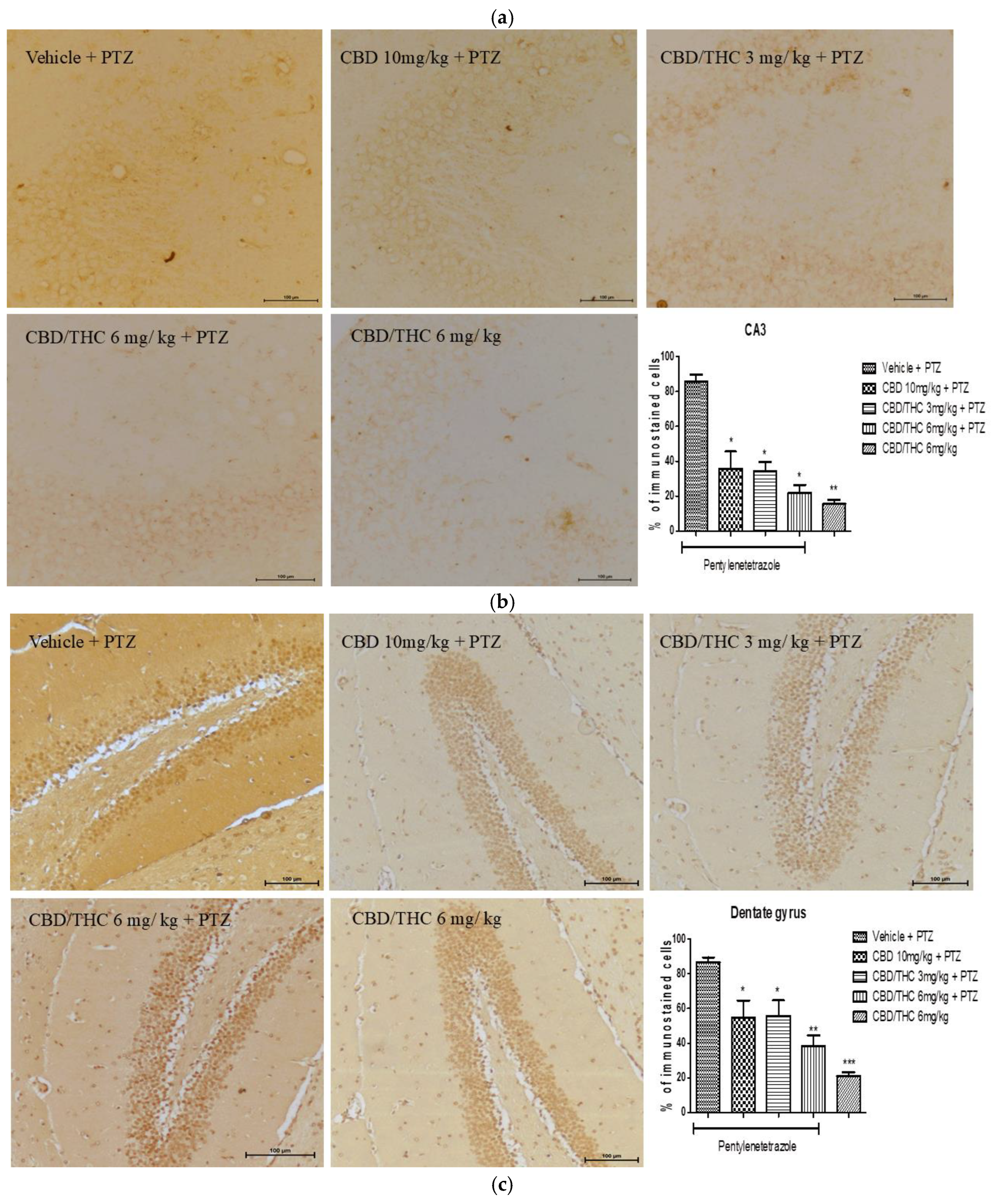

Our results demonstrate that in mice subjected to PTZ-induced kindling, the expression of GFAP, an astrogliosis marker, is decreased in animals preemptively treated with CBD and THC nanoemulsions relative to those preemptively treated with vehicle. Astrocytes play a critical role in regulating the brain tissue environment, including synaptic activity modulation and neurotransmitter homeostasis. Previous studies, such as those by Mika et al. [

50] and Devinsky et al. [

51], emphasize the importance of astrocytes in epilepsy pathophysiology, primarily through changes in expression of proteins like GFAP, which entails dysfunction in glutamate uptake. The reduction in GFAP expression observed in our study may indicate a protective action of the cannabinoid nanoemulsions, possibly through modulation of astrocytic function, contributing to a more stable synaptic environment and reduced susceptibility to seizures.

Previous studies showed that treatment with

Cannabis sativa extracts resulted in a decrease in GFAP expression in hippocampal astrocytes in rats, suggesting a protective effect in neurological conditions characterized by astrocytic reactivity, reaffirming our findings [

52]. The research focused on analyzing the effects of

Cannabis treatment on GFAP expression, a crucial marker of astrogliosis in the brain's response to injuries or diseases. The reduction of GFAP expression implies that

Cannabis compounds may act by modulating glial physiology, potentially protecting neurons from damage caused by excess inflammatory mediators.

Kozela et al. [

53] investigated how CBD modulates astrocyte activity in various neurological pathology models, including ischemia, Alzheimer's-like disease, multiple sclerosis, sciatic nerve injury, epilepsy, and schizophrenia. The results showed that CBD suppressed increased astrocyte reactivity in those conditions, as well as reduced pro-inflammatory activity and signaling in astroglial cells, suggesting its therapeutic potential in mitigating tissue dysfunction in such neurological diseases. Furthermore, Mao et al. [

54] explored the neuroprotective effects of CBD in rats with chronic epilepsy, observing a significant reduction in seizure severity, neuronal loss, and astrocyte hyperplasia in the hippocampus.

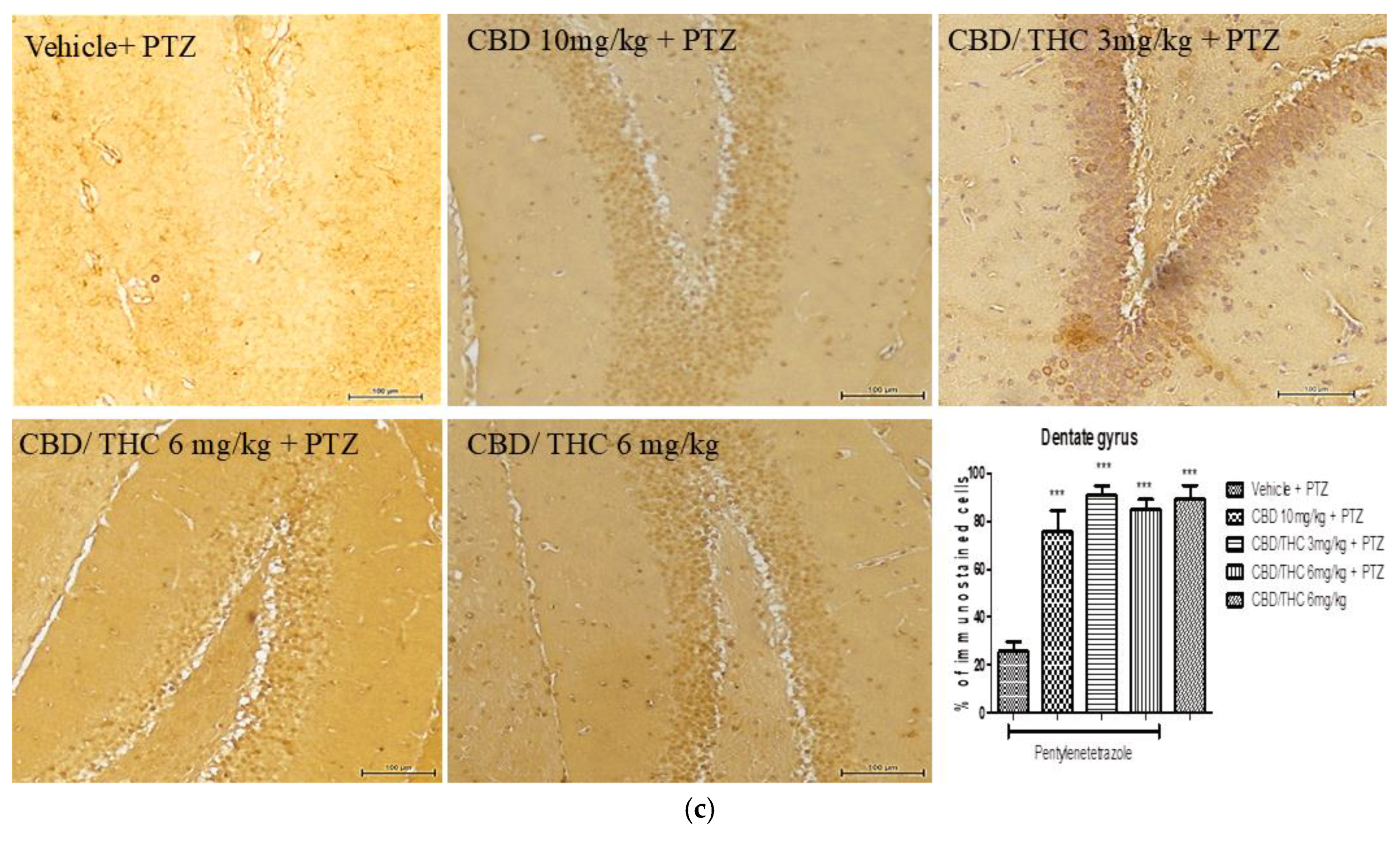

The present study showed that CBD and the combination of CBD and THC can increase the expression of Kir4.1, which, along with the probable modulation of other ion channels, could influence neuronal excitability. However, these results are preliminary, and a detailed understanding of the mechanisms involved and how cannabinoids affect Kir4.1 from the perspective of seizure and epilepsy pathophysiology remains a subject of research [

55].

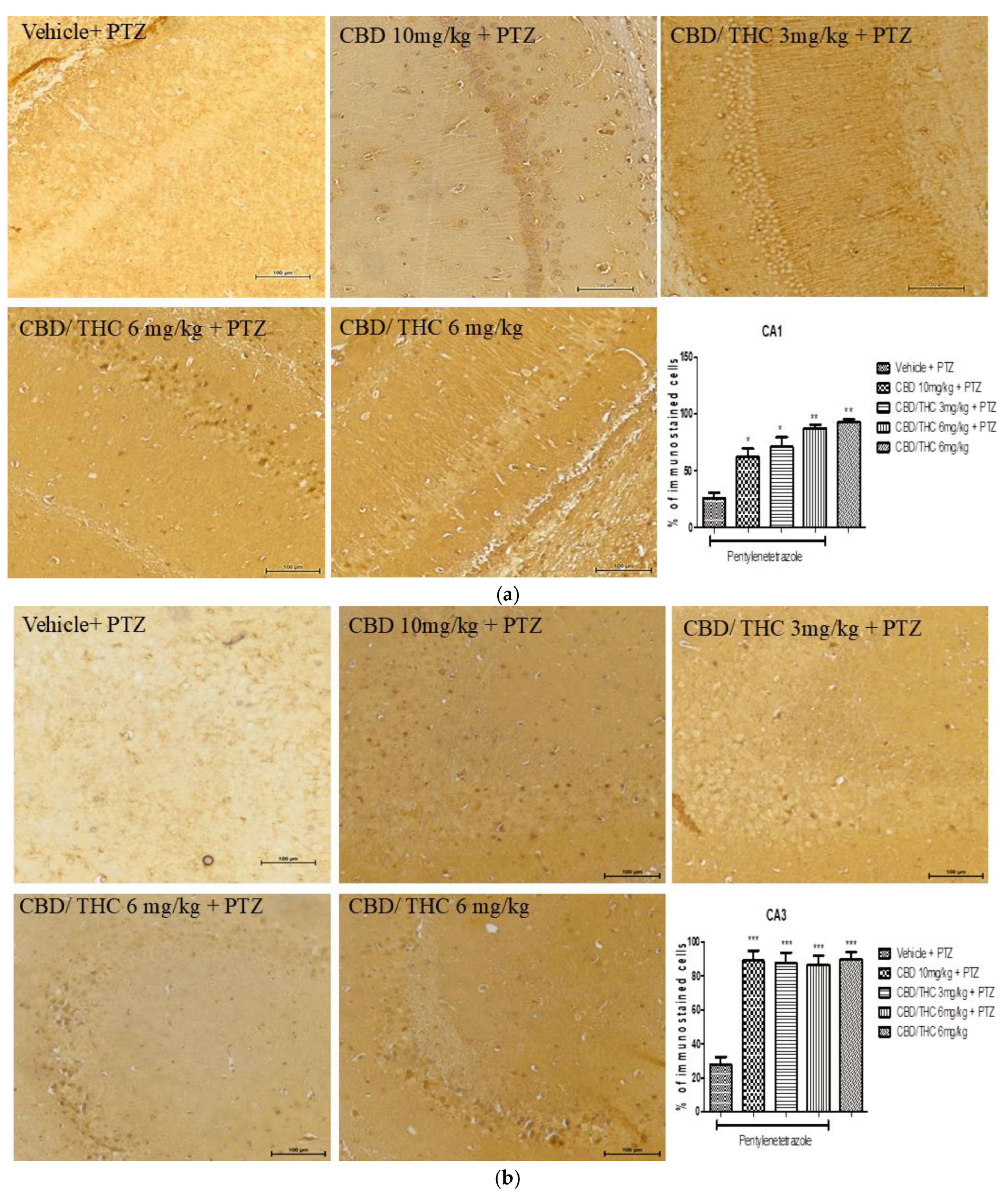

The GAT-1 transporter plays a crucial role in epilepsy by regulating the reuptake of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA at synaptic terminals and glial cells. Its dysfunction is associated with reduced synaptic inhibition, contributing to neuronal hyperexcitability and, consequently, the generation and propagation of epileptic seizures. Modulating GAT-1 activity may offer a potential therapeutic approach to control seizures and improve clinical outcomes in patients with epilepsy [

56].

Carvill et al. [

57], investigating a type of epilepsy characterized by myoclonic-atonic seizures, identified mutations in the GAT1 encoding gene, SLC6A1, as an etiological factor, leading to a loss of function of the GABA transporter. This study expands the understanding of the genetic basis of epilepsy, offering new insights into diagnostics and treatments focused on GABA regulation, and suggests a significant role of altered GABA reuptake in epilepsy pathophysiology. The increase in GAT1 observed in our vehicle-treated animals most likely represents a pathophysiological element of epileptogenesis, which is restored by the cannabinoid treatment. This finding reinforces the importance of GAT-1 in regulating inhibitory neurotransmission and maintaining the excitatory-inhibitory balance in the brain, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target for specific interventions in epilepsy and paving the way for future investigations into GAT-1 modulation as a strategy to control neuronal hyperexcitability.

Our immunohistochemical findings revealed significant neurochemical alterations in animals that underwent preemptive treatment with CBD and its combination with THC, highlighting a decrease in GAT1 expression. This observation suggests that CBD, alone or in combination with THC, may influence inhibitory neurotransmission, possibly modulating synaptic activity and contributing to restoring an altered excitatory-inhibitory balance in the brain. These results reinforce the therapeutic potential of these compounds in modulating neurological disorders such as epilepsy through the regulation of GAT-1 and Kir4.1.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

Crude oil from

Cannabis indica: CBD chemotype (Cs-CBD), and

Cannabis sativa: THC chemotype (Cs-THC) was produced and kindly provided by the Brazilian Association for the Medicinal Use of

Cannabis (ABRACAM; 257 Francisco Teixeira de Alcântara Street, Fortaleza, CE 60182-360). Oil extraction was from the Rick Simpson's method. This technique involves the production of a concentrated

Cannabis oil, also known as "Rick Simpson’s Oil" (RSO). The goal is to produce a highly concentrated oil containing a large amount of active

Cannabis compounds, such as the cannabinoids THC and CBD [

58].

The Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) profile for the crude oils Cs-CBD and Cs-THC, both containing Hydrogen-1 (1H NMR) and Carbon-13 (13C NMR), were characterized using an Avance DRX 500 MHz Spectrometer (Bruker) at CENAUREMN (Northeastern Center for the Application and Use of NMR, Department of Organic and Inorganic Chemistry-UFC). Figures representing the spectrograms are in the supplementary material. Cs-CBD was adsorbed on silica gel and subjected to preparative column chromatography to generate a fraction mainly composed of CBD, which was characterized by 1H NMR. The process was repeated once to provide a solid fraction called purified CBD (CBD-pur.), also characterized by 1H NMR and 13C NMR. Cs-CBD and CBD-pur. were compared by thin layer chromatography. Likewise, Cs-THC was adsorbed on silica gel and subjected to preparative column chromatography to generate a fraction composed mainly of THC, which was characterized by 1H NMR and 13C NMR, revealing a high degree of purity, being called purified THC (THC-pur.), also characterized by 1H NMR and 13C NMR. The Cs-THC and THC-pur. were compared by thin layer chromatography. Both Cs-CBD and CBD-pur., as well as Cs-THC and THC-pur., in nanoemulsion form were pharmacologically tested in vivo.

4.2. Preparation of Nanoemulsions

The oil extracted from nuts of licuri or ouricuri (Syagrus coronata), a palm tree from the Arecaceae family, was obtained from Licuri Brazil (Caldeirão Grande-BA, Brazil). The non-ionic surfactant used was the triblock copolymer poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide)- poly(ethylene oxide) (Pluronic® F127) from Sigma-Aldrich. For the preparation and characterization of the nanoemulsions, as well as the characterization methods, all reagents were of analytical grade.

The fatty acid composition of licuri oil was assessed using gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on a SHIMADZU QP-2010 ULTRA instrument, utilizing a (5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane (DB-5) capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm), with helium as the carrier gas (flow rate of 0.6 mL/min) in a splitless mode (injection volume of 1 μL of 1 mg/mL solutions of each product diluted in ethyl acetate). The oven temperature was initially set at +120 ˚C and increased at 10 ˚C/min to +300 ˚C, then maintained for 10 min. The injector and detector temperatures were +250 and +300 ˚C, respectively. The quadrupole analyzer was set to electron ionization (EI) mode and scanned from 50 to 450 m/z.

The aqueous phase (AP) and the organic phase (OP) were prepared and homogenized separately. The hydrophilic surfactant Pluronic® F127 (0.2 g) was added to the AP (90% of the formulation). Licuri oil (1 g) and THC (0.1 g) or CBD (0.1 g) constituted the OP (10% of the formulation). To produce each primary emulsion (10 g), the previously prepared AP was slowly added to OP and stirred at 1000 rpm for 30 min. To generate THC and CBD nanoemulsions, each primary emulsion was sonicated using a probe sonicator (Digital Sonifier W-450D, Branson) for 3 min (10s on/10s off), at 70% amplitude, in ice bath.

The nanodroplet size, PDI, and ZP of THC and CBD nanoemulsions were determined using a dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument at 25 °C with a Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The nanoemulsions were diluted at 1:1000 with deionized water. Averages and standard deviations were calculated in triplicate.

4.3. Animals and Treatments

Male Swiss mice (n=15; body weight: 25–33 g) were kept at 25 ± 2 °C, under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum. The study was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Research of the Faculty of Medicine of the Federal University of Ceará, protocol number 7839060721.

PTZ (99% purity) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Depakene (solution containing 50mg/mL sodium valproate) was purchased from Abbott Brazil Laboratories Ltda. All other drugs and reagents were of analytical grade.

Mice received either the vehicle (F127 + encapsulated licuri oil, p.o.) or nanoemulsions containing CBD or THC, respectively, at doses 1, 3, 6 and 10 mg/kg, or the combination of CBD and THC (1:1 volume/volume) at 1.5, 3 and 6 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, PTZ (80 mg/kg) was i.p. administered and animals were set in pairs at the center of plastic boxes, in a quiet environment. All experimental groups were visually monitored for one hour after the PTZ injection. The following parameters were measured: latency to first generalized seizure; latency to death; survival rate. After recovery, surviving animals were kept in cages with chow and water to evaluate the survival rate after 24 hours [

59,

60]. Brains were dissected for the neurochemical assays immediately after death.

The valproic acid control group was excluded from these tests because its action primarily targets neurotransmission, with little direct impact on oxidative and nitrosative stress markers. In this way, we optimized the comparison between cannabinoids and minimized the unnecessary use of animals. This decision follows the principles of the 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse and Refine), seeking to minimize the number of animals used, avoid redundancy and maximize scientific efficiency.

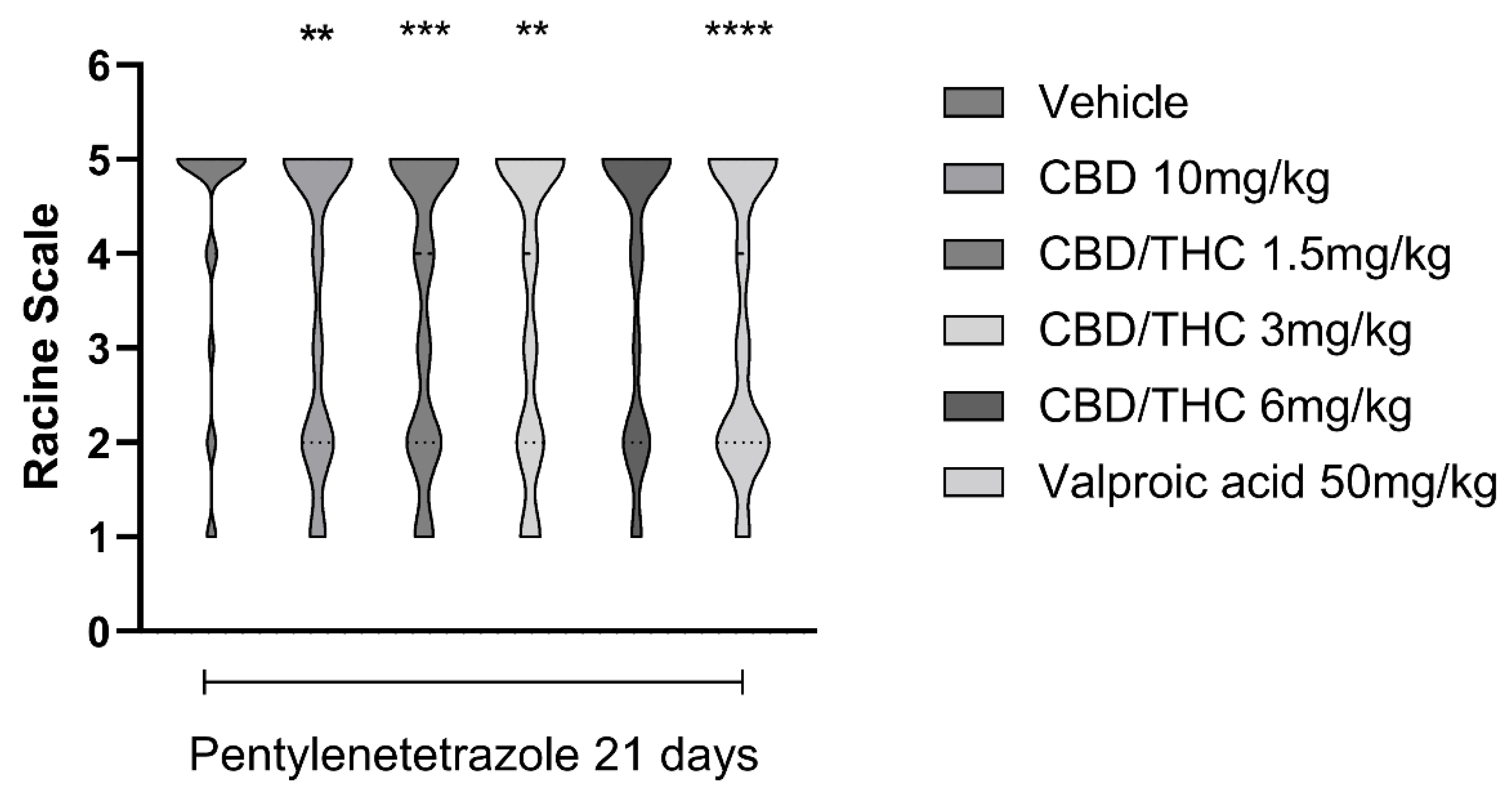

Further mice (n=15 animals per group) received PTZ 30 mg/kg i.p. every other day, for 21 days or until the development of full kindling, corresponding the most severe seizure stage. Sixty minutes before PTZ administration, either vehicle, or CBD 10 mg/kg, or the CBD/THC 1:1 combination at 1.5, 3 and 6 mg/kg, or valproic acid 50mg/kg were p.o. administered. On the 21st day of the protocol, after the PTZ injection, animals were scored over 30 minutes to grade behavioral seizures according to the Racine's scale, consisting of: stage 1 – normal behavior; stage 2 – hyperactivity; stage 3 – repeated vertical movements that may represent stereotypical behavior; stage 4 – clonus of the forepaws and “rearing”, and stage 5 – clonus of all paws, loss of righting reflex and fall, tonic ventral flexion of the head and the whole body, and tonic hindpaw extension [

61]. Full kindling was considered when the animal presented a motor behavior corresponding to stage 5 [

61,

62]. Additionally, a group was treated solely with CBD/THC (1:1) at 6 mg/kg, without PTZ, to assess the effects of the cannabinoids’ combination independently. On the following day, behavioral tests were carried out before killing for immunohistochemistry.

4.4. Behavioral Analysis

The novel ORT is used to evaluate recognition memory. This task is based on the innate tendency of rodents to explore unfamiliar objects within their environment. This test assesses the mouse ability to discriminate between familiar and novel objects. Firstly, mice were individually habituated to an open field Plexiglas® box (30 × 30 × 40 cm) for 5 min. After 15 min, mice were allowed to explore a set of two identical objects for 5 min (acquisition phase). These objects were suitably heavy and long to ensure that mice could neither displace them, nor climb over them. After a 5 min interval, mice were presented to a similar set of objects in the same environment, with the replacement of one familiar object by a novel/unknown object (testing phase). The animals were allowed to freely explore the objects again for a 5 min long period. The discrimination index was calculated as follows: (time exploring new object-time exploring familiar object)/(time exploring new object + time exploring familiar object) [

63].

The working memory and learning were assessed by the rate of spontaneous alternations in the Y-maze (40 × 5 × 16 cm), with three arms positioned at equal angles, as previously described [

64]. Before running the test, the arms were numbered, and the animal was placed in one arm and spontaneously alternated the entries in the other arms for 8 min. The sequence of the arms into which the animal entered was then noted down, and the information analyzed to determine the number of arm entries without repetition [

65].

4.5. Evaluation of Oxidation in the Brain

Animals that underwent the acute PTZ protocol had their brains used for neurochemical assays of NO3-/NO2- and TBARS. To this purpose, prefrontal cortices, hippocampi, and striata were dissected on aluminum foil-covered ice. Brain areas were kept under -80 °C until use.

Griess reagent was added to a 96-well plate containing the supernatant of the homogenates of prefrontal cortices, hippocampi, and striata from 6–8 animals. The absorbance was measured using a microplate reader at 560nm. Samples were harvested from animals treated with only vehicle (no PTZ, basal level group). Previously, a standard curve for nitrite was generated using concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, and 1.56 nmol/mL. Results were expressed as nmol/g tissue [

66].

Brain areas (prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum) from 6-8 animals were used to prepare 10% homogenates in 1.15% KCl. Then, 250 μL were added to 1mL trichloroacetic acid 10%, followed by addition of 1 mL thiobarbituric acid 0.6%. After agitation, this mixture was kept in a water bath (95–100 °C, 15 min), cooled on ice, and centrifuged (1500 × g/5 min). The TBARS content was determined in a plate reader at 540 nm, with results expressed in nmol of MDA per gram of tissue. A standard curve with MDA was performed previously [

67].

4.6. Immunohistochemistry

Animals that underwent the PTZ-induced kindling protocol, after behavioral testing were used for immunohistochemistry. Ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg) i.p. injections were the euthanasia protocol. After loss of withdrawal reflex to paw pinch, animals were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline (about 60 mL) for vascular rinsing, and afterwards with 60 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde solution in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4). Brains were then post-fixed in the same PFA 4% solution at 4 °C for 24h. After this, brains were immersed in 70% alcohol for subsequent paraffin embedding; 3 μm thick coronal slices were then obtained at the microtome (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Coronal sections obtained from −2.46 mm to −2.92 mm (caudal to bregma), containing the hippocampus (Franklin and Paxinos 2019), were cut and postfixed in 70% ethanol. After cooling, the sections were washed four times with PBS, and endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% H

2O

2 in PBS (15 min). Sections were incubated overnight (4 °C) with primary antibodies (anti-GAT-1 1:200, Abcam ab426; anti-GFAP 1:200, Thermo Fisher 53-9892-82; anti-KCNJ10 1:200, Elabscience EAB-19262) in PBS, according to the manufacturer's instructions. On the next day, sections were washed in PBS four times, incubated (30 min) with secondary biotinylated rabbit antibody (anti-IgG) in PBS (1:200), washed four times in PBS, and incubated (30 min) with the conjugated streptavidin-peroxidase complex (Burlingame, CA, USA). After washing, sections were developed with 3,3-diaminobenzidine, mounted on gelatinized glass slides, dehydrated and coverslipped for analysis [

68]. The images were analyzed semi-quantively (ImageJ software, NIH) using the plugin: Color deconvolution HDAB-Threshold-Measure particle.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Data following a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and compared using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. For data that did not meet normality assumptions, the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test for post hoc analysis. Survival analysis during the PTZ-induced kindling protocol was conducted using the Log-rank test. A 95% confidence interval was adopted for all analyses, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.E.A.d.A., F.J.G.J., M.M.F.F., G.S.B.V.; methodology, P.E.A.d.A., T.S.N., Í.R.L., D.H.A.B.; validation, F.J.G.J., NM.P.S.R, G.B.; formal analysis, P.E.A.d.A., G.É.P.A., K.B.S.; investigation, P.E.A.d.A., T.S.N., G.M.A., D.S.Z.; resources, N.M.P.S.R., E.R.S., G.B.; chemical characterization, N.M.P. S.R., E.R.S.; nanoemulsion development, D.H.A.B., K.B.S., D.S.Z., G.É.P.A.; statistical analysis, F.J.G.J., M.M.F.F., G.S.B.V.; data curation, Í.R.L., D.H.A.B., K.B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.E.A.d.A., G.S.B.V., T.S.N., Í.R.L., G.M.A.; writing—review and editing, P.E.A.d.A., M.M.F.F., G.S.B.V; visualization, Í.R.L., D.S.Z., and E.R.S.; supervision, M.M.F.F, G.S.B.V., G.B.; project administration, P.E.A.d.A., F.J.G.J.; funding acquisition, N.M.P.S.R., E.R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) nanoemulsions are respectfully shown in (a) THC and (b). Note that THC and CBD nanoemulsions were consistent.

Figure 1.

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) nanoemulsions are respectfully shown in (a) THC and (b). Note that THC and CBD nanoemulsions were consistent.

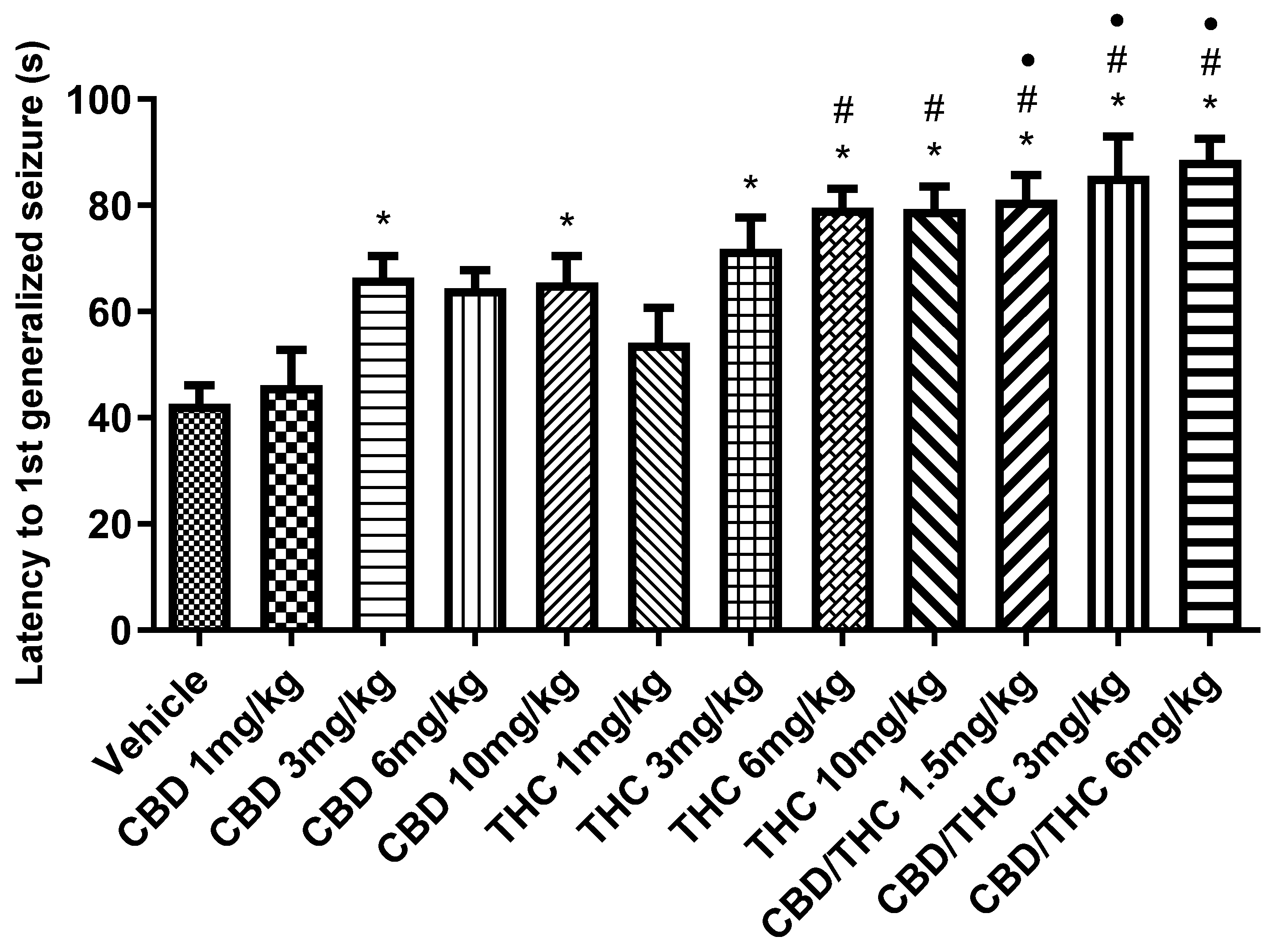

Figure 2.

Animals treated with nanoemulsions containing cannabidiol (CBD), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or a CBD/THC combination (1:1) showed a significant increase in the latency to the first generalized seizure compared to the vehicle group. This increase was more pronounced at intermediate and high doses (3, 6, and 10 mg/kg). The lowest doses (1 mg/kg) of isolated CBD and THC did not show a significant difference. Treatments were administered by gavage, and 60 minutes later the animals received intraperitoneal pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, 80 mg/kg). Values are in seconds (s), mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05 compared to the vehicle, #p < 0.05 compared to CBD 1 mg/kg, ●p < 0.05 compared to THC 1 mg/kg. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Figure 2.

Animals treated with nanoemulsions containing cannabidiol (CBD), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or a CBD/THC combination (1:1) showed a significant increase in the latency to the first generalized seizure compared to the vehicle group. This increase was more pronounced at intermediate and high doses (3, 6, and 10 mg/kg). The lowest doses (1 mg/kg) of isolated CBD and THC did not show a significant difference. Treatments were administered by gavage, and 60 minutes later the animals received intraperitoneal pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, 80 mg/kg). Values are in seconds (s), mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05 compared to the vehicle, #p < 0.05 compared to CBD 1 mg/kg, ●p < 0.05 compared to THC 1 mg/kg. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

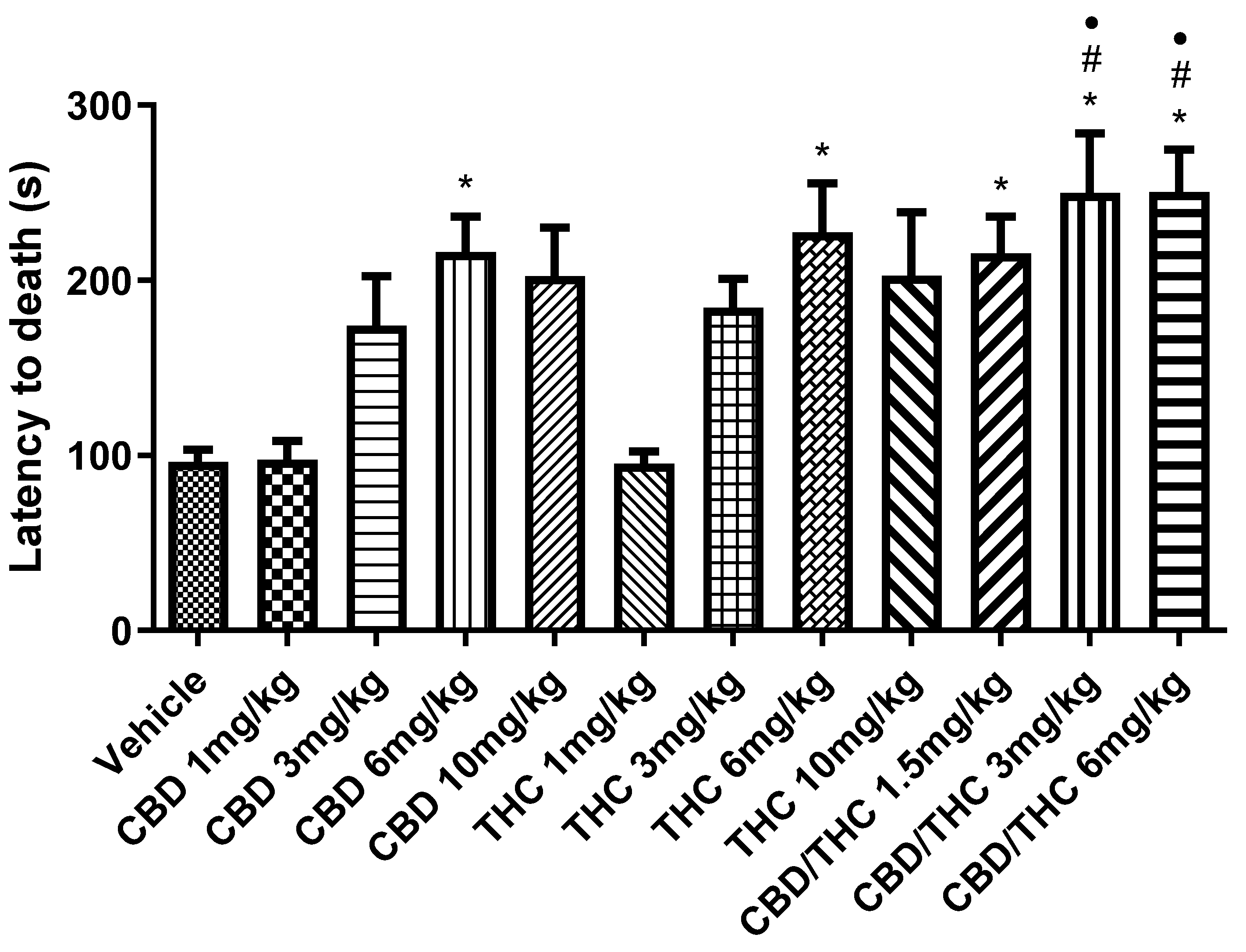

Figure 3.

Animals treated with nanoemulsions containing cannabidiol (CBD), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or a CBD/THC combination (1:1) showed a significant increase in the survival time, measured as latency to death. This increase was more pronounced at intermediate and high doses (3, 6, and 10 mg/kg). The lowest doses (1 mg/kg) of isolated CBD and THC showed no significant difference. Treatments were administered by gavage, and 60 minutes later the animals received intraperitoneal pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, 80 mg/kg). Values are in seconds (s), mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05 compared to the vehicle, #p < 0.05 compared to CBD 1 mg/kg, ●p < 0.05 compared to THC 1 mg/kg. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Figure 3.

Animals treated with nanoemulsions containing cannabidiol (CBD), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or a CBD/THC combination (1:1) showed a significant increase in the survival time, measured as latency to death. This increase was more pronounced at intermediate and high doses (3, 6, and 10 mg/kg). The lowest doses (1 mg/kg) of isolated CBD and THC showed no significant difference. Treatments were administered by gavage, and 60 minutes later the animals received intraperitoneal pentylenetetrazole (PTZ, 80 mg/kg). Values are in seconds (s), mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05 compared to the vehicle, #p < 0.05 compared to CBD 1 mg/kg, ●p < 0.05 compared to THC 1 mg/kg. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

Figure 4.

Cannabinoids’ pretreatment attenuated the increase in the nitrate (NO3-)/nitrite (NO2-) concentration related to pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced acute seizures at all tested doses. Animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 80 mg/kg. After death, nitrate/nitrite concentrations were measured in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and striatum. Values of nitrite in μmol per gram of tissue are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Significant values: *p<0.05 versus vehicle. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 4.

Cannabinoids’ pretreatment attenuated the increase in the nitrate (NO3-)/nitrite (NO2-) concentration related to pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced acute seizures at all tested doses. Animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 80 mg/kg. After death, nitrate/nitrite concentrations were measured in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and striatum. Values of nitrite in μmol per gram of tissue are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Significant values: *p<0.05 versus vehicle. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 5.

Cannabinoids’ pretreatment attenuated the increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration caused by pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced acute seizures, at all tested doses. Animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ at 80 mg/kg. After death, MDA concentration was measured in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and striatum. Values of MDA in μmol per gram of tissue are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Significant values: *p<0.05 versus vehicle. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 5.

Cannabinoids’ pretreatment attenuated the increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration caused by pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced acute seizures, at all tested doses. Animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ at 80 mg/kg. After death, MDA concentration was measured in prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and striatum. Values of MDA in μmol per gram of tissue are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Significant values: *p<0.05 versus vehicle. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 6.

Pretreatment with per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination significantly slowed the development of pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced kindling. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg or valrpoic acid 50 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given PTZ 30mg/kg i.p.. After the last PTZ administration, seizures were staged according to the Racine's scale: stage 1 – normal behavior; stage 2- hyperactivity; stage 3 – repeated vertical movements that may represent stereotypical behavior; stage 4 – clonus of the front paws and “rearing”; and stage 5 – clonus of the four paws, loss of the righting reflex and fall, tonic ventral flexion of the head and the whole body and tonic hind paw extension. Results are expressed as median. Significant values: **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 versus vehicle. Kruskal Wallis' and Dunn's post hoc test.

Figure 6.

Pretreatment with per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination significantly slowed the development of pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced kindling. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg or valrpoic acid 50 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given PTZ 30mg/kg i.p.. After the last PTZ administration, seizures were staged according to the Racine's scale: stage 1 – normal behavior; stage 2- hyperactivity; stage 3 – repeated vertical movements that may represent stereotypical behavior; stage 4 – clonus of the front paws and “rearing”; and stage 5 – clonus of the four paws, loss of the righting reflex and fall, tonic ventral flexion of the head and the whole body and tonic hind paw extension. Results are expressed as median. Significant values: **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 versus vehicle. Kruskal Wallis' and Dunn's post hoc test.

Figure 7.

Pretreatment with per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination did not prevent the impairment in novel object recognition test, related to pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) chronic administration for kindling. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg, or valproic acid 50 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, behavioral tests were carried out. Discrimination index is presented as mean ± SEM. Significant values: *p<0.05. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 7.

Pretreatment with per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination did not prevent the impairment in novel object recognition test, related to pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) chronic administration for kindling. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg, or valproic acid 50 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, behavioral tests were carried out. Discrimination index is presented as mean ± SEM. Significant values: *p<0.05. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 8.

Effect of per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination on the Y-maze test performance in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-kindled mice. No cannabinoid preemptive treatment prevented the impairment in Y maze test related to PTZ-induced kindled seizures. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 combination 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg or valproic acid 50 mg/kg. After 60 minutes, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, behavioral tests were carried out. Percentage of arm alternation is presented as mean ± SEM. Significant values: *p<0.05. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 8.

Effect of per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination on the Y-maze test performance in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-kindled mice. No cannabinoid preemptive treatment prevented the impairment in Y maze test related to PTZ-induced kindled seizures. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 combination 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg or valproic acid 50 mg/kg. After 60 minutes, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, behavioral tests were carried out. Percentage of arm alternation is presented as mean ± SEM. Significant values: *p<0.05. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test.

Figure 9.

Effect on body weight of per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination, their vehicle, or valproic acid, in presence of pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced kindling or not. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg or valproic acid 50 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30mg/kg. Results are expressed as median values. Significant values: *p<0.05 versus vehicle. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post hoc Dunn's test.

Figure 9.

Effect on body weight of per os cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination, their vehicle, or valproic acid, in presence of pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced kindling or not. Every other day, for 21 days, animals (n=15 per group) were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of CBD 10 mg/kg or CBD/THC 1:1 1.5, 3 or 6 mg/kg or valproic acid 50 mg/kg. Sixty minutes later, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30mg/kg. Results are expressed as median values. Significant values: *p<0.05 versus vehicle. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post hoc Dunn's test.

Figure 10.

Cannabinoid pretreatment prevented the changes in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity in 3 hippocampal areas (CA1 - a; CA3 – b; dentate gyrus – c) as observed in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-treated mice receiving the cannabinoid vehicle. Every other day, for 21 days, animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination. After 60 minutes, animals were given PTZ 30 mg/kg i.p.. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, after behavioral tests, animals were euthanized and transcardially perfused for immunohistochemistry, 4 animals per group. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Significant values: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus vehicle.

Figure 10.

Cannabinoid pretreatment prevented the changes in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity in 3 hippocampal areas (CA1 - a; CA3 – b; dentate gyrus – c) as observed in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-treated mice receiving the cannabinoid vehicle. Every other day, for 21 days, animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination. After 60 minutes, animals were given PTZ 30 mg/kg i.p.. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, after behavioral tests, animals were euthanized and transcardially perfused for immunohistochemistry, 4 animals per group. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Significant values: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus vehicle.

Figure 11.

Cannabinoid pretreatment prevented the changes in GABA transporter 1 (GAT1) immunoreactivity in 3 hippocampal areas (CA1 - a; CA3 – b; dentate gyrus – c) as observed in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-treated mice receiving the cannabinoid vehicle. Every other day, for 21 days, animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination. After 60 minutes, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30 mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, after behavioral tests, animals were euthanized and transcardially perfused for immunohistochemistry, 4 animals per group. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Significant values: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus vehicle.

Figure 11.

Cannabinoid pretreatment prevented the changes in GABA transporter 1 (GAT1) immunoreactivity in 3 hippocampal areas (CA1 - a; CA3 – b; dentate gyrus – c) as observed in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-treated mice receiving the cannabinoid vehicle. Every other day, for 21 days, animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination. After 60 minutes, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30 mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, after behavioral tests, animals were euthanized and transcardially perfused for immunohistochemistry, 4 animals per group. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Significant values: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus vehicle.

Figure 12.

Cannabinoid pretreatment prevented the changes in Kyr1.4 immunoreactivity in 3 hippocampal areas (CA1 - a; CA3 – b; dentate gyrus – c) as observed in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-treated mice receiving the cannabinoid vehicle. Every other day, for 21 days, animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination. After 60 minutes, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30 mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, after behavioral tests, animals were euthanized and transcardially perfused for immunohistochemistry, 4 animals per group. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Significant values: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus vehicle.

Figure 12.

Cannabinoid pretreatment prevented the changes in Kyr1.4 immunoreactivity in 3 hippocampal areas (CA1 - a; CA3 – b; dentate gyrus – c) as observed in pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-treated mice receiving the cannabinoid vehicle. Every other day, for 21 days, animals were gavaged with either vehicle or nanoemulsion of cannabidiol (CBD) 10 mg/kg or CBD/ Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 1:1, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg combination. After 60 minutes, animals were given intraperitoneal PTZ 30 mg/kg. One group was given CBD/THC 1:1 6 mg/kg and no PTZ. On the day after the last drug administration, after behavioral tests, animals were euthanized and transcardially perfused for immunohistochemistry, 4 animals per group. One-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Significant values: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 versus vehicle.

Table 1.

Fatty Acid Composition of Licuri Oil.

Table 1.

Fatty Acid Composition of Licuri Oil.

| Fatty acid |

Area (%) |

Area (%)* |

| Decanoic acid (C10:0 - capric acid) |

7.87 |

6.40 |

| Dodecanoic acid (C12:0 - lauric acid) |

42.13 |

43.64 |

| Tetradecanoic acid (C14:0 - myristic acid) |

16.14 |

14.32 |

| Hexadecanoic acid (C16:0 - palmitic acid) |

9.18 |

6.89 |

| Octadec-9-enoic acid (C18:1 - oleic acid) |

19.52 |

11.78 |

| Octadecanoic acid (C18:0 - stearic acid) |

5.15 |

3.83 |

| Octanoic acid (C8:0 - caprylic acid) |

- |

10.05 |

| Octadeca-9,12-dienoic acid (C18:2 - linoleic acid) |

- |

3.1 |

Table 2.

Characterization of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) nanoemulsions by polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential (ZP).

Table 2.

Characterization of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) nanoemulsions by polydispersity index (PDI) and zeta potential (ZP).

| Formulation |

Droplet size (nm) |

PDI |

ZP (mV) |

| THC nanoemulsion |

237.5 ± 1.457 |

0.092 ± 0.032 |

-33.9 ± 2,14 |

| CBD nanoemulsion |

247.2 ± 1.153 |

0.082 ± 0.016 |

-32.4 ± 1.37 |