Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

26 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

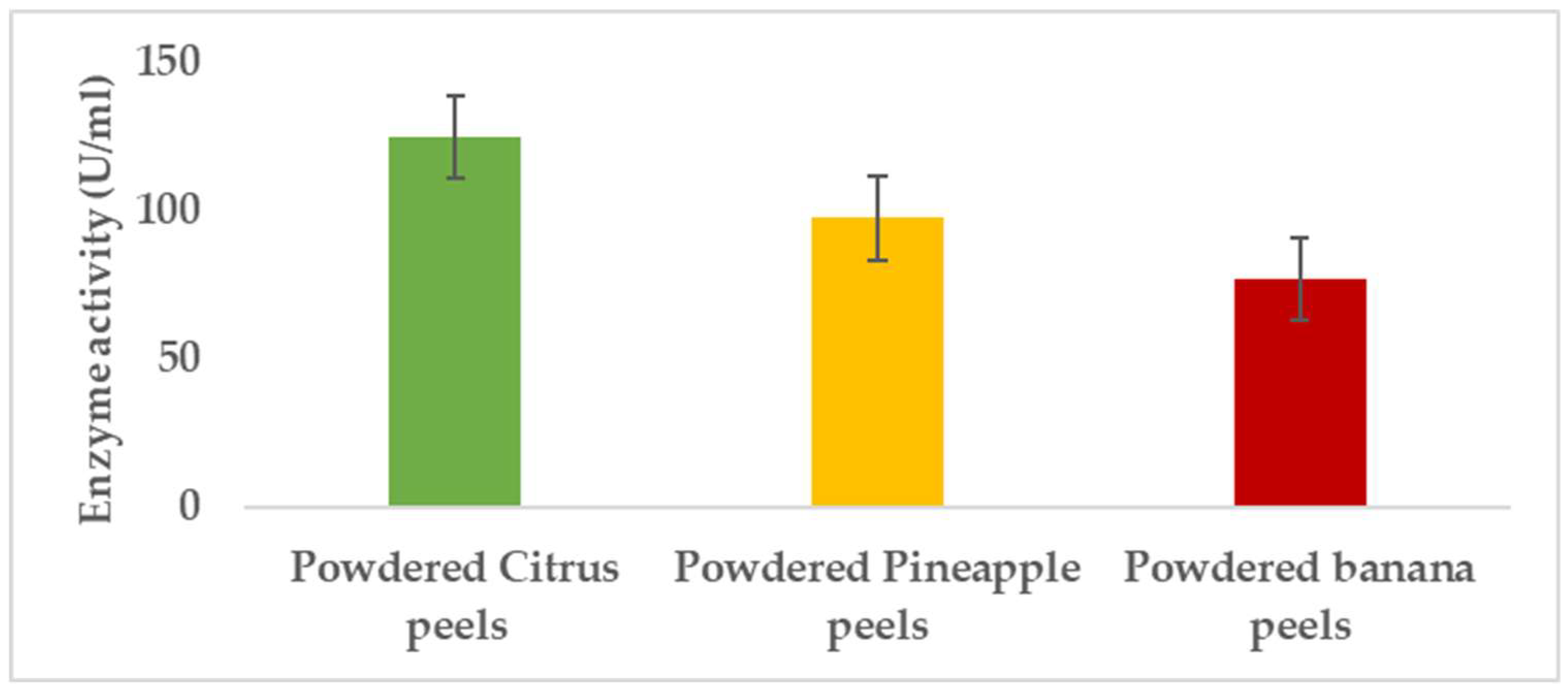

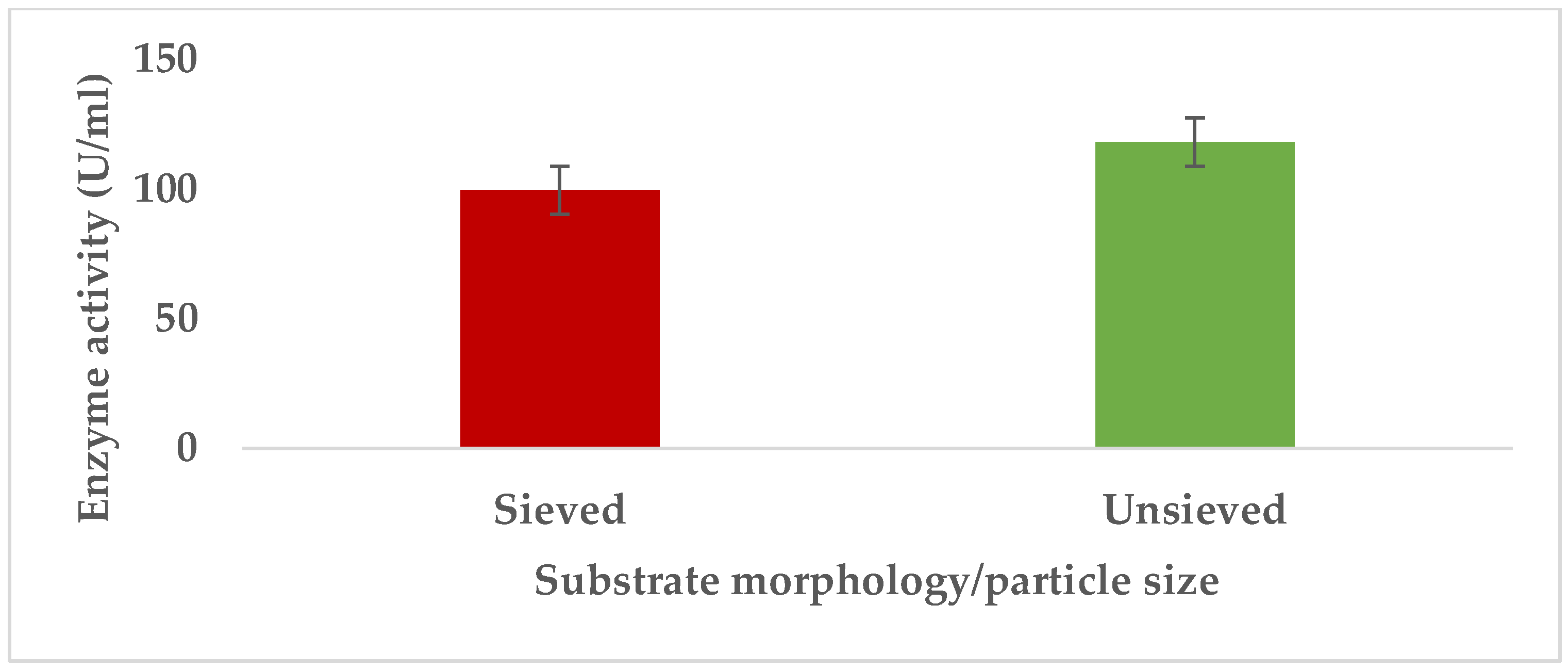

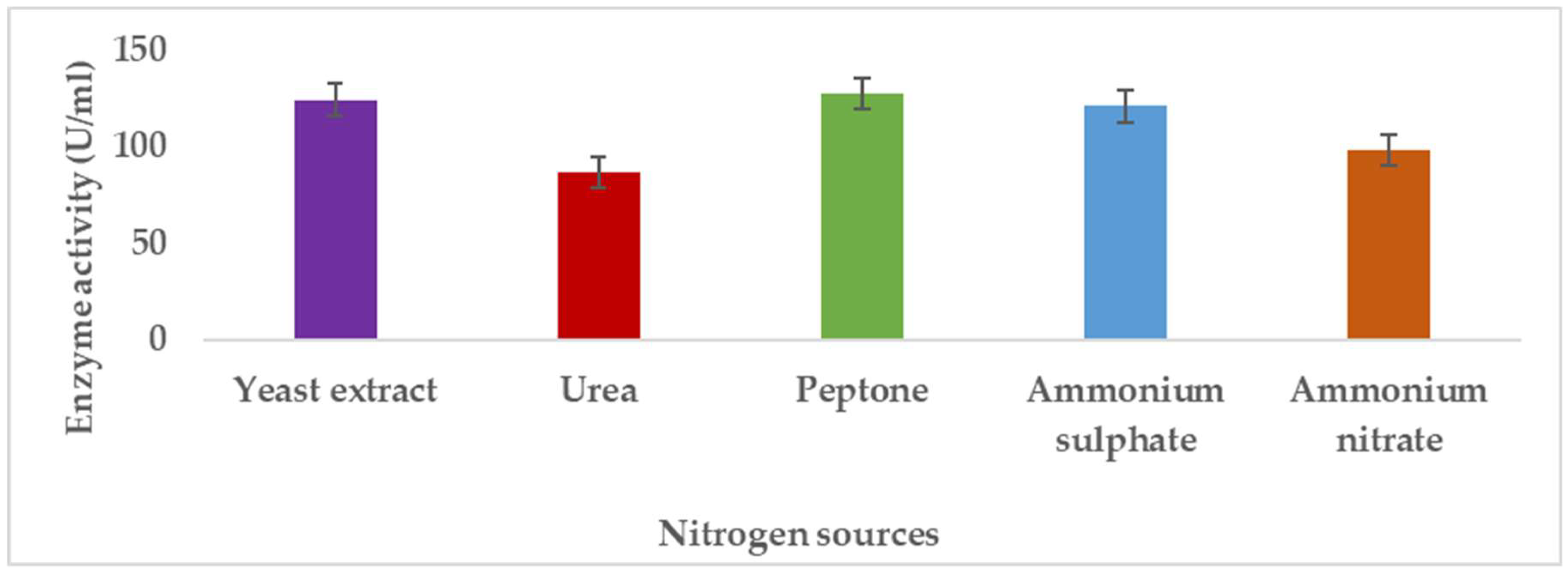

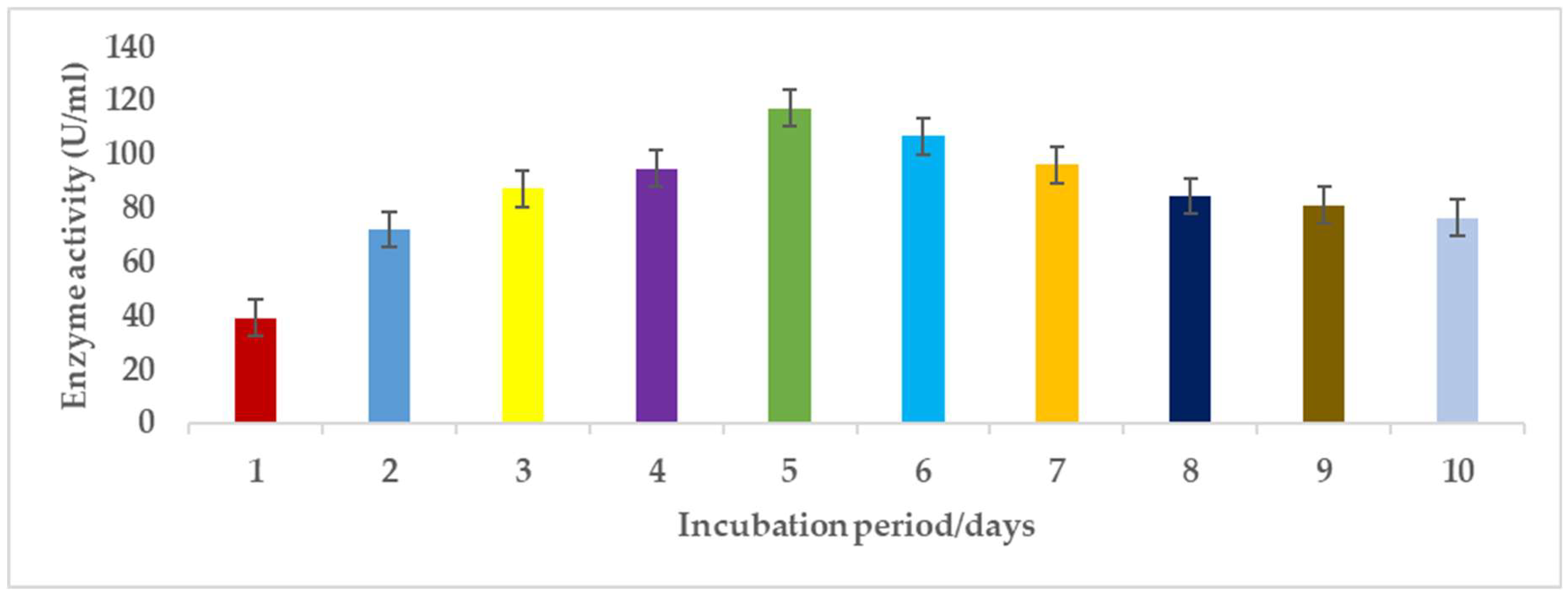

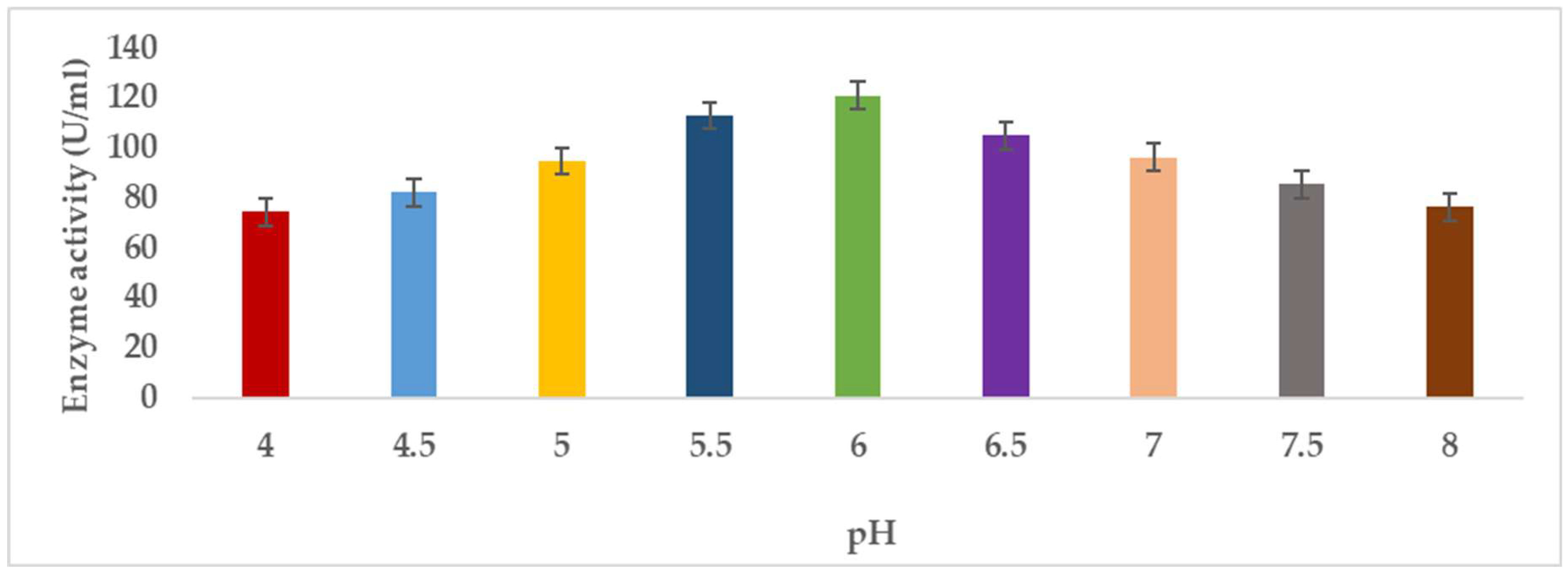

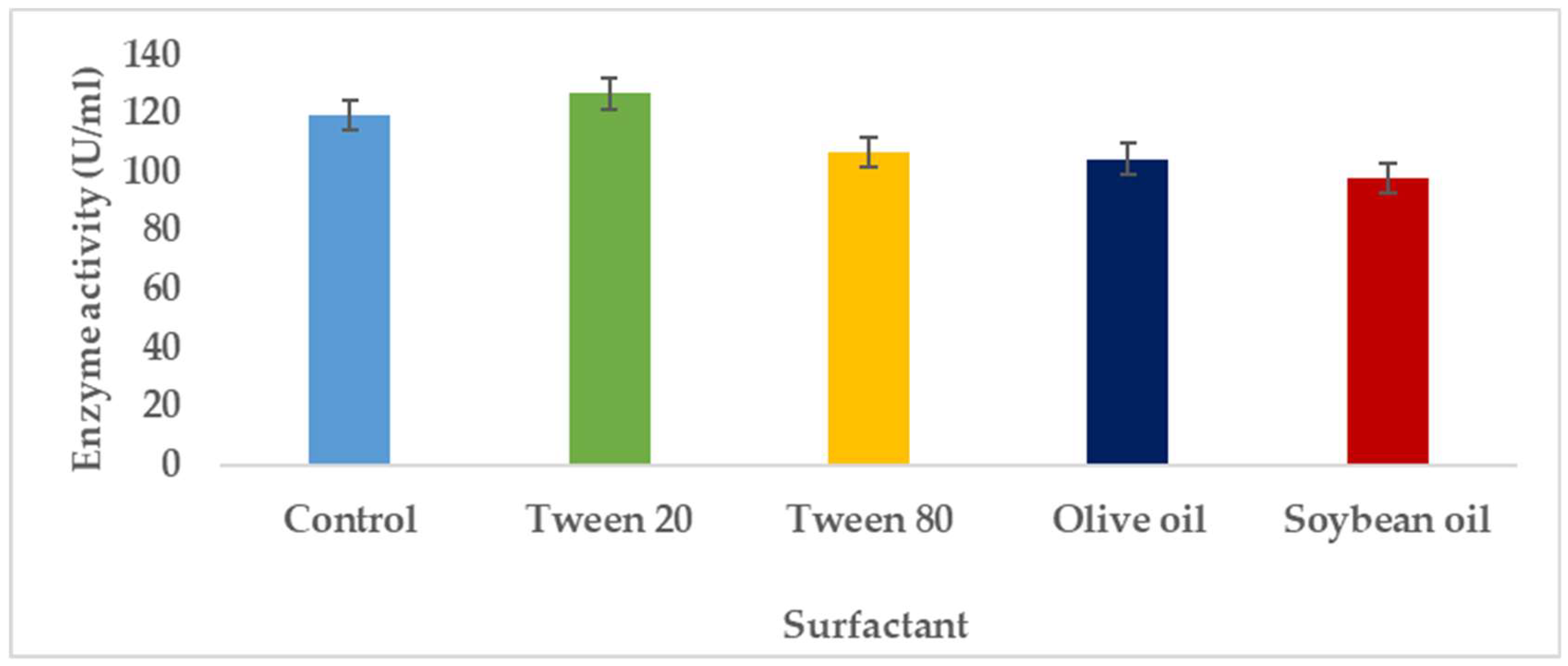

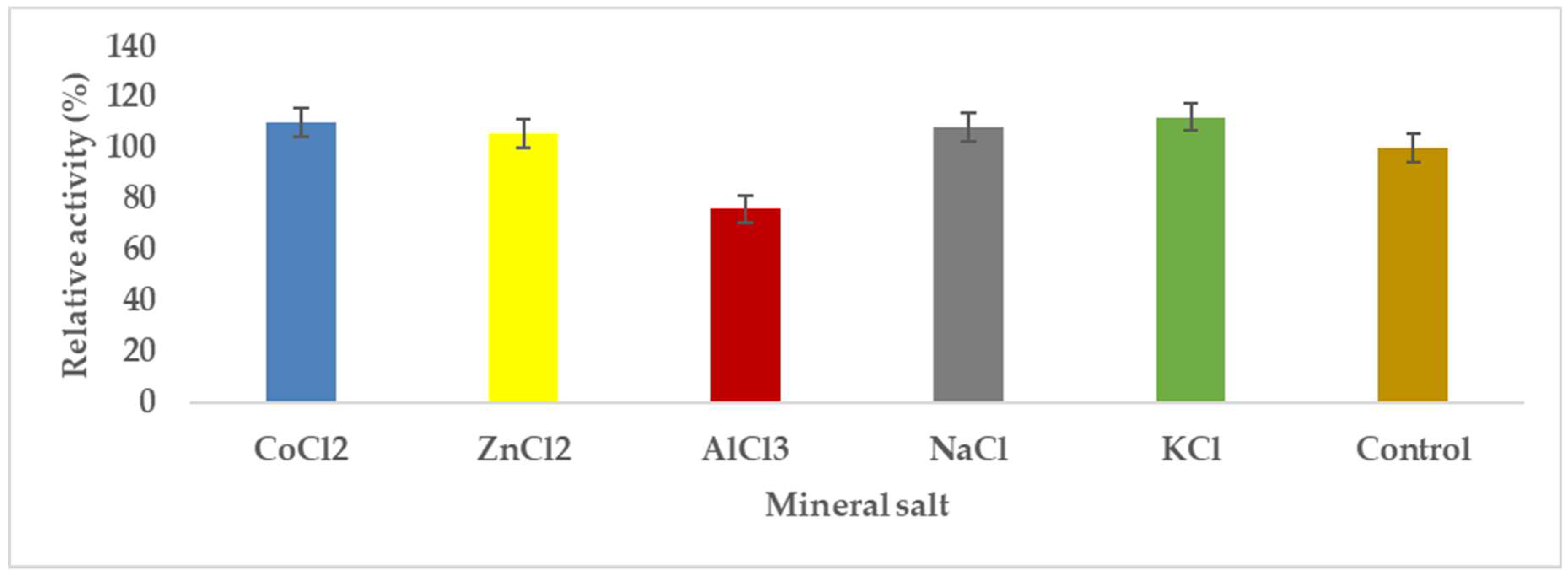

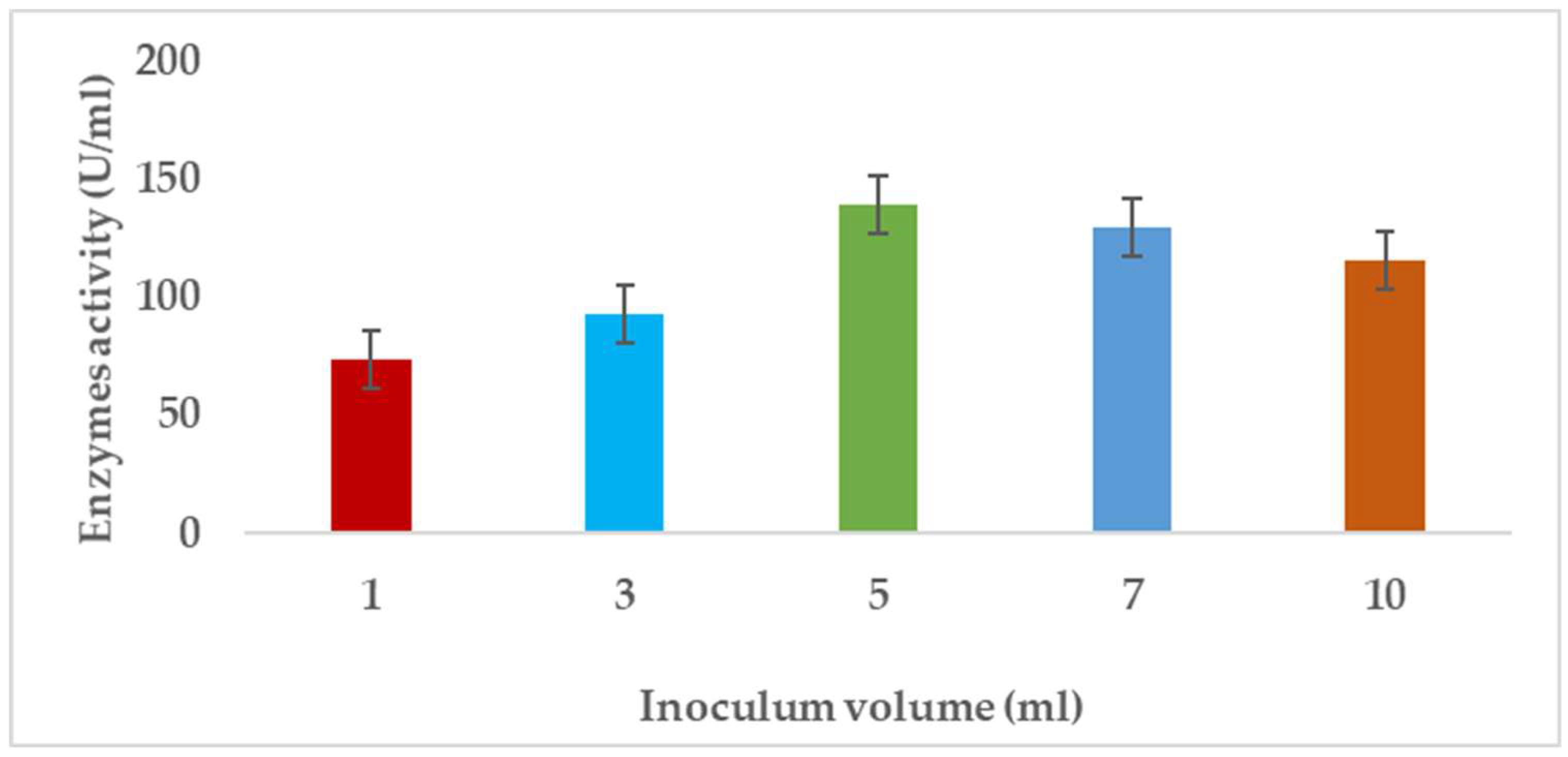

Pectinases represent a class of enzymes involved in the breakdown of pectin-rich compounds. The importance of pectinases are well documented as they command at least a quarter of all food enzymes and 70% of all the fruit and juice processing enzymes sold around the world, respectively. The worldwide enzymes market is presently valued at $12.3 billion and is predicted to grow to $20.31 billion by 2030. This study successfully optimized the various conditions that could illicit the synthesis of pectinolytic enzymes using Aspergillus niger obtained from the soil of decomposed fruit and vegetable matter under solid-state fermentation conditions. Under the respective optimized fermentation conditions, the peak pectinase enzyme synthesis had been achieved under pH 6.0 (121.1 U/ml), incubation period of 5 days (117.4 U/ml), substrate morphology/particles size (118.0 U/ml), Peptone as nitrogen source (127.6 U/ml), Potassium chloride (KCl) as mineral salt (112.3 U/ml), Tween-20 as surfactant (126.8 U/ml), inoculum volume of 5.0ml (139.4 U/ml) and powdered Citrus peels as the best carbon source (124.8 U/ml). Under current study, moisture content (70%) and room temperature (25-30°C) and fermentation vessel (2.2L perforated tin tomato cans) were constantly maintained throughout the experiments executed under solid-state fermentation conditions. The success achieved from current study, make this enzyme isolated from Aspergillus niger, a potential candidate for many industrial applications including fruit juice clarification, wine production, food processing, coffee and tea fermentation, protoplast fusion, waste treatment, production of pharmaceuticals, detergents, pulp and paper and biofuels.

Keywords:

1.0. Introduction

2.0. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Processing of Discarded Fruits as Substrate

2.2. Preparation of Potato Dextrose Agar for Isolation of Fungal Species

2.3. Collection and Identification of Microorganism

2.4. Inoculum Preparation

2.5. Preparation of 3, 5-Dinitrosalicylic Acid (DNS)

2.6. Optimization of Parameters Controlling Pectinase Production

2.6.1. Effects of Carbon Source for Pectinase Production

2.6.2. Impacts of Substrate Morphology/Particles Size on Pectinase Synthesis

2.6.3. Effect of Nitrogen Sources on Pectinase Production

2.6.4. Effects of Incubation Periods Influencing the Production of Pectinase

2.6.5. Effects of pH on Pectinase Production

2.6.6. Effect of Surfactants on the Production of Pectinolytic Enzymes

2.6.7. Effect of Mineral Salt Supplement on Pectinase Production

2.6.8. Impact Exerted by Different Volumes of Inoculum Affecting Synthesis of Pectinase

2.7. Pectinase Enzyme Extraction and Activity Determination

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3.0. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization Parameters for Pectinase Enzyme Production

3.1.1. Carbon Source

3.1.2. Particle Size/Morphology of Substrate

3.1.3. Effects of Nitrogen Source on Pectinase Production

3.1.4. Incubation Period

3.1.5. Hydrogen Ion Concentration (pH)

3.1.6. Effects Imposed by Surfactants on Pectinase Synthesis by A. niger

3.1.7. Effects of Mineral Salts Affecting Pectinase Enzyme Synthesis by A. niger

3.1.8. Effects of Inoculum Volume on Pectinase Enzyme Produced by A. niger

4.0. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflict of Interest

Ethical Approval

Consent to Publish

References

- Hassan, S. (2020). Development of Novel Pectinase and Xylanase Juice Clarifcation Enzymes via a Combined Biorefnery and Immobilization Approach, Doctoral Thesis, Technological University Dublin. [CrossRef]

- Baljinder Singh Kauldhar, Harpreet Kaur, Venkatesh Meda, Balwinder Singh Sooch (2022). Chapter 12 - Insights into upstreaming and downstreaming processes of microbialextremozymes. Extremozymes and Their Industrial Applications, Academic Press, Pages 321 352, ISBN 9780323902748. [CrossRef]

- International Pectin Producers Association (2023). Pectin and sustainability. (Date assessed:01/11/2023).https://pectinproducers.com/factsheethub/sustainability/#:~:text=Once%20pectin%20has%20been%20extracted,sustainable%20in%20other%20ways%2C%20too.

- Shet AR, Desai SV, Achappa S. (2018). Pectinolytic enzymes: classification, production, purification and applications. Res. J. Life Sci Bioinform Pharm Chem Sci.; 4:337 –48.

- G. Garg, A. Singh, A. Kaur, R. Singh, J. Kaur3, R. Mahajan (2016). Microbial pectinases: an ecofriendly tool of nature for industries. 3 Biotech 6:47.

- Soorej M. Basheer, Sreeja Chellappan, A. Sabu (2022). Chapter 8 - Enzymes in fruit and vegetable processing, Editor(s): Mohammed Kuddus, Cristobal Noe Aguilar, Value Addition in Food Products and Processing through Enzyme Technology, Academic Press, Pages 101-110, ISBN 9780323899291. M. [CrossRef]

- Singh, Ram Sarup, Singh, Tranjeet; Pandey, Ashok (2019). Micrbial enzymes-An overview. Advances in Enzyme Technology, Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals. Elsevier, pp, 1-40, ISBN 978-0-444-64114-4.

- Emilio Rosales, Marta Pazos, M Ángeles Sanromán, (2018). Chapter 15 - Solid-StateFermentation for Food Applications, Editor(s): Ashok Pandey, Christian Larroche, Carlos Ricardo Soccol, Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Elsevier, Pages 319-355, ISBN 9780444639905. [CrossRef]

- Grand Research Review (2022): Enzymes Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Lipases, Polymerases & Nucleases, Carbohydrase), By Type (Industrial, Specialty), By Source (Plants, Animals), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2022 – 2030 (date assessed: 22/06/2022). Report ID: 978-1-68038-022-4.

- B, Leela Mani, D, Sailaja, K, Kamala (2018). Determination and Partial Purification of Pectinase Enzyme Produced by Aspergillus niger using Pineapple Peels as Sole Source of Carbon. IJEDR | Volume 6, Issue 1 | ISSN: 2321-9939.

- Q. A. Al-Maqtari, A. A. Waleed, and A. A. Mahdi (2019). “Microbial enzymes produced by fermentation and their applications in the food industry-A review,” International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research, vol. 8, no. 1.

- Dataintelo (2019). Global Juices Processing Enzymes Sales Market Report (WWW Document). URL https://dataintelo.com/report/juices-processingenzymes-sales-market/ (accessed 12.13.20).

- Sonali Satapathy, Jyoti Prakash Soren, Keshab Chandra Mondal, et al (2021). Industrially relevant pectinase production from Aspergillus parvisclerotigenus KX928754 using apple pomace as the promising substrate, Journal of Taibah University for Science, 15:1, 347-356. [CrossRef]

- Magnus Ivarsson, Henrik Drake, Stefan Bengtson, Birger Rasmussen (2020). A Cryptic Alternative for the Evolution of Hyphae. BioEssays. [CrossRef]

- Xiangyang Liu, Chandrakant Kokare, (2023). Chapter 17 - Microbial enzymes of use in industry, Editor(s): Goutam Brahmachari, Biotechnology of Microbial Enzymes (Second Edition), Academic Press, Pages 405-444, ISBN 9780443190599. [CrossRef]

- Meyer V, Basenko EY, Benz JP, Braus GH, Caddick MX, Csukai M, et al. (2020). Growing a circular economy with fungal biotechnology: a white paper. Fungal Biol Biotechnol.; 7:5. [CrossRef]

- Sandri IG, Silveira MM. (2018). Production and application of pectinases from Aspergillus niger obtained in solid state cultivation. Beverages. 4:48. [CrossRef]

- Ramón Verduzco-Oliva and Janet alejandra Gutierrez-Uribe (2020). Beyond Enzyme Production: Solid State Fermentation (SSF) as an Alternative Approach to Produce Antioxidant Polysaccharides. Sustainability 2020, 12, 495. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S. S., Tiwari, B., Williams, G. A. & Jaiswal, A. K. (2020). Bioprocessing of brewers’ spent grain for production of Xylanopectinolytic enzymes by Mucor sp. Bioresource Technology Reports, 9, 100371. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, K., Periasmy, V., Kandeel, M., Umapathy, V.R. (2022). Mass Multiplication, Production Cost Analysis and Marketing of Pectinase. Industrial Microbiology Based Entrepreneurship. Microorganisms for Sustainability, vol 42. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Oumer, O.J.; Abate, D. (2018). Screening and molecular identification of pectinase producing microbes from coffee pulp. BioMed Res. Int., 2961767.

- Manan MA, Webb C. (2017). Design aspects of solid state fermentation as applied to microbial bioprocessing. J Appl Biotechnol Bioeng.; 4(1):511‒532. [CrossRef]

- José Carlos, D.L.-M.; Leonardo, S.; Jesús, M.-C.; Paola, M.-R.; Alejandro, Z.-C.; Juan, A.-V.; Cristóbal Noé, A. (2020). Solid-State Fermentation with Aspergillus niger GH1 to Enhance Polyphenolic Content and Antioxidative Activity of Castilla Rose Purshia plicata Plants, 9, 1518. [CrossRef]

- Jorge A.V. Costa, Helen Treichel, Vinod Kumar, Ashok Pandey (2018). Chapter 1 - Advances in Solid-State Fermentation, Editor(s): Ashok Pandey, Christian Larroche, Carlos Ricardo Soccol, Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering, Elsevier, Pages 1-17, ISBN 9780444639905. [CrossRef]

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2021). (vol. 70th edition), BP Statistical Review, London, UK [Online]. Available: https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-full-report.pd.

- Binod Sharma, Ashish Shrestha (2023). Petroleum dependence in developing countries with an emphasis on Nepal and potential keys, Energy Strategy Reviews, Volume 45, 101053, ISSN 2211-467X. [CrossRef]

- Patidar MK, Nighojkar S, Kumar A, Nighojkar A. Pectinolytic enzymes-solid state fermentation, assay methods and applications in fruit juice industries: a review. 3 Biotech. 2018 Apr; 8(4):199. Epub 2018 Mar 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okonji, R.E., Itakorode, B.O., Ovumedia, J.O., Adedeji, O.S. (2019). Purification and biochemical characterization of pectinase produced by Aspergillus fumigatus isolated from soil of decomposing plant materials. Journal of Applied Biology & Biotechnology., 7(03):1-8.

- Sudeep KC, Jitendra U. Dev R. J., Binod L, Dhiraj K. C., Bhoj R. P, Tirtha R. B., Rajiv D. Santosh K., Niranjan K. ,10,Vijaya R. (2020). Production, Characterization, and Industrial Application of Pectinase Enzyme Isolated from Fungal Strains. Fermentation, 6, 59. [CrossRef]

- Boakye, S.O and Zakpaa, H.D (2025): Proximate Characterization of discarded fruits and their valorization to obtain pectin. Mendeley Data, V1. V1. [CrossRef]

- Boakye, S.O, Zakpaa, H.D, Borigu M., and Duwiejuah, A.B. (2025): Isolation, screening and identification of pectinolytic fungal species from soil of decomposed plant materials. Pretrints.org. [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, C.J., Mims, C.W., Blackwell, M. (1996). Intro. Mycology. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley.

- Barnett, H.L and Hunter, B.B (1972). Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi. 3rd Edition, Burgess Publishing Co., Minneapolis, 241 p.

- Satapathy, S., Behera, P.M., Tanty, D.K., Srivastava, S., Thatoi, H., Dixit, A., Sahoo, S.L. (2019). Isolation and molecular identification of pectinase producing Aspergillus species from different soil samples of Bhubaneswar regions. BioRxiv. The preprint sever for biology. 1(1):1-22.

- Kaur, H.P., Kaur, G. 2014. Optimization of cultural conditions for pectinase produced by fruit spoilage fungi. International journal of advances in research. 3(4):851-859.

- Satvinder Singh Dhillon , Rajwant Kaur Gill , Sikander Singh Gill & Malkiat Singh (2004). Studies on the utilization of citrus peel for pectinase production using fungus Aspergillus niger , International Journal of Environmental Studies, 61:2, 199-210. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G. L. (1959). Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Analytical Chemistry, 31, 426-428.

- Dange V.U., Harke S (2018). Production and purification of Pectinase by fungal strain in solid-state fermentation using agro-industrial bioproduct. International Journal of Life Sciences Vol. 6, Issue 4, pp: (85-93). ISSN 2348-3148.

- Yu P, Xu C. (2018). Production optimization, purification and characterization of a heat-tolerant acidic pectinase from Bacillus sp. ZJ1407. Inter J Biol Macromol; 108:972–80.

- Sarita Shrestha; Chonlong Chio; Janak Raj Khatiwada; Aristide Laurel Mokale Kognou; Xuantong Chen; Wensheng Qin (2023). Optimization of Cultural Conditions for Pectinase Production by Streptomyces sp. and Characterization of Partially Purified Enzymes. Microb Physiol 33 (1): 12–26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Taufq Mat Jalil* and Darah Ibrahim (2021): Partial Purifcation and Characterisation of Pectinase Produced by Aspergillus niger LFP-1 Grown on Pomelo Peels as a Substrate. Tropical Life Sciences Research 32(1): 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Setegn Haile and Abate Ayele (2022). Pectinase from Microorganisms and Its Industrial Applications. The Scientific World Journal Volume 2022, Article ID 1881305, 15 pages. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury T I, Jubayer F, Uddin B. and Aziz G. (2017). Production and characterization of pectinase enzyme from Rhizopus oryzae. Potravinarstvo Slovak Journal of Food Sciences 11(1): 641–651. [CrossRef]

- Ametefe, G.D., Oluwadamilare, L.A., Ifeoma, C. J., Olubunmi, I. I., Ofoegbu, V. O., Folake, F., Orji, F. A., Iweala, E.E.J., and Chinedu, S. N. (2021). Optimization of Pectinase Activity From Locally Isolated Fungi and Agrowastes. Research square. [CrossRef]

- Mat Jalil MT, Zakaria NA, Salikin NH, Ibrahim D. (2023). Assessment of cultivation parameters influencing pectinase production by Aspergillus niger LFP-1 in submerged fermentation. J Genet Eng Biotechnol.; 21(1):45. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ametefe, G.D., Dzogbe¦a V.P., Apprey C., Kwatia S. (2017). Optimal conditions for pectinase production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ATCC 52712) in solid state fermentation and its efficacy in orange juice extraction. IOSR. J. of Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 3(6): 78-86.

- E. El-Ghomary, A. A. Shoukry, and M. B. EL-Kotkat. (2021). Productivity of pectinase enzymes by Aspergillus sp. isolated from Egyptian soil. Al-Azhar Journal of Agricultural Research V. (46) No. (2): 79-87.

- Arekemase M.O., Omotosho I.O., Agbabiaka T.O., Ajide-Bamigboye N.T., Lawal A.K., Ahmed T. and Orogu J. O (2020). Optimization of bacteria pectinolytic enzyme production using banana peel as substrate under submerged fermentation. Science World Journal Vol. 15(No 1) 2020 www.scienceworldjournal.org ISSN 1597-6343.

- Ire FS, Vinking EG (2016). Production, purifcation, and characterization of polygalacturonase from Aspergillus niger in solid state and submerged fermentation using banana peels. J. Adv Biol Biotechnol 10(1):1–15.

- N. A. Acheampong, Gariba, W., Mensah, M., Fei-baffoe, B., Offei, F., Asankomah, J., & Sheringham, L. (2021). Optimization of hydrolases production from cassava peels by Trametes polyzona BKW001. Scientific African, 12, e00835. [CrossRef]

- Adedayo, M. R., mohammed, M. T., ajiboye, A. E. And abdulmumini, S. A. (2021). Pectinolytic activity of Aspergillus niger and aspergillus flavus grown on grapefruit (citrus parasidis) peel in solid state fermentation. Global journal of pure and applied sciences vol. 27, 93-105. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, R.; Farooq, I.; Kaleem, A.; Iqtedar, M.; Iftikhar, T. (2018). Pectinase production from Aspergillus niger IBT-7 using solid state fermentation. Bangladesh J. Bot., 47, 473–478.

- A. Ahmed, M. A. Ahmed, M. Sohail (2020) Characterization of pectinase from Geotrichum candidum AA15 and its potential application in orange juice clarification Journal of King Saud University - Science, 32 (1), pp. 955-961, 10.1016/j.jksus.2019.07.

- Robert Cavanagh, Saif Shubber, Driton Vllasaliu, Snjezana Stolnik (2022). Enhanced permeation by amphiphilic surfactant is spatially heterogenous at membrane and cell level, Journal of Controlled Release, Volume 345, Pages 734-743, ISSN 0168-3659. [CrossRef]

- Le Wang, Yu Sha, Dapeng Wu, Qixian Wei, Di Chen, Shuoye Yang, Feng Jia, Qipeng Yuan, Xiaoyao Han, Jinshui Wang (2020). Surfactant induces ROS-mediated cell membrane permeabilization for the enhancement of mannatide production, Process Biochemistry, Volume 91, Pages 172-180, ISSN 1359-5113. [CrossRef]

- Jacob Tchima Massai, Hamida Aminatou, Jean Boris Sounya, Dieudonne Ranava, Sebastien Vondou Vondou, Ousman Adjoudji and Palou Madi Oumarou (2021): Effects of salt on seed germination and plant growth of Anaccardium occidentale. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 15 (4): 1563-1572. ISSN 1997-342X (online).

- Bibi N, Ali S, Tabassum R (2016). Statistical optimization of pectinase biosynthesis from orange peel by Bacillus licheniformis using submerged fermentation. Waste Biomass Valorization 7:467– 481. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).