Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Purification of Microorganisms

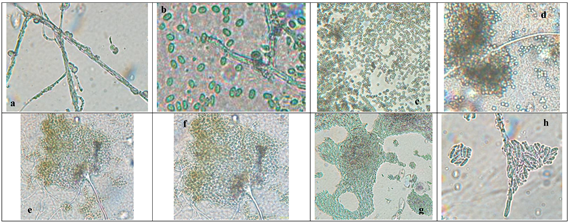

2.2. Morphological Identification

2.3. Molecular Identification Through DNA Sequencing

2.4. Ex Vivo Fungal Activity

2.5. In Vitro Antifungal Activity with Essential Oils

3. Results

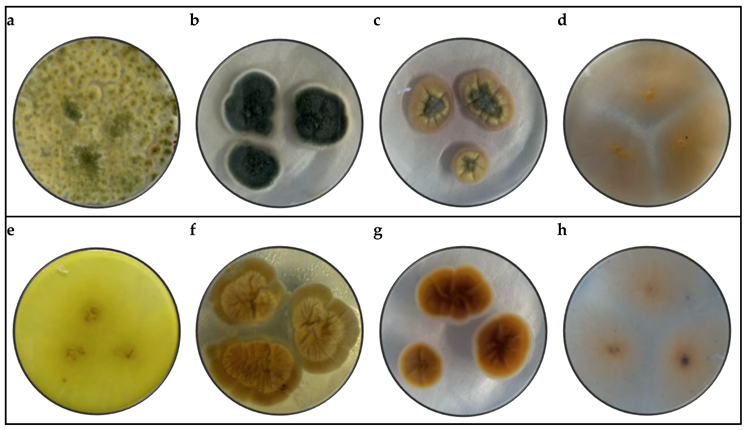

3.1. Morphological Identification

3.2. Molecular Identification Through DNA Sequencing

3.3. Fungal Activity Ex Vivo

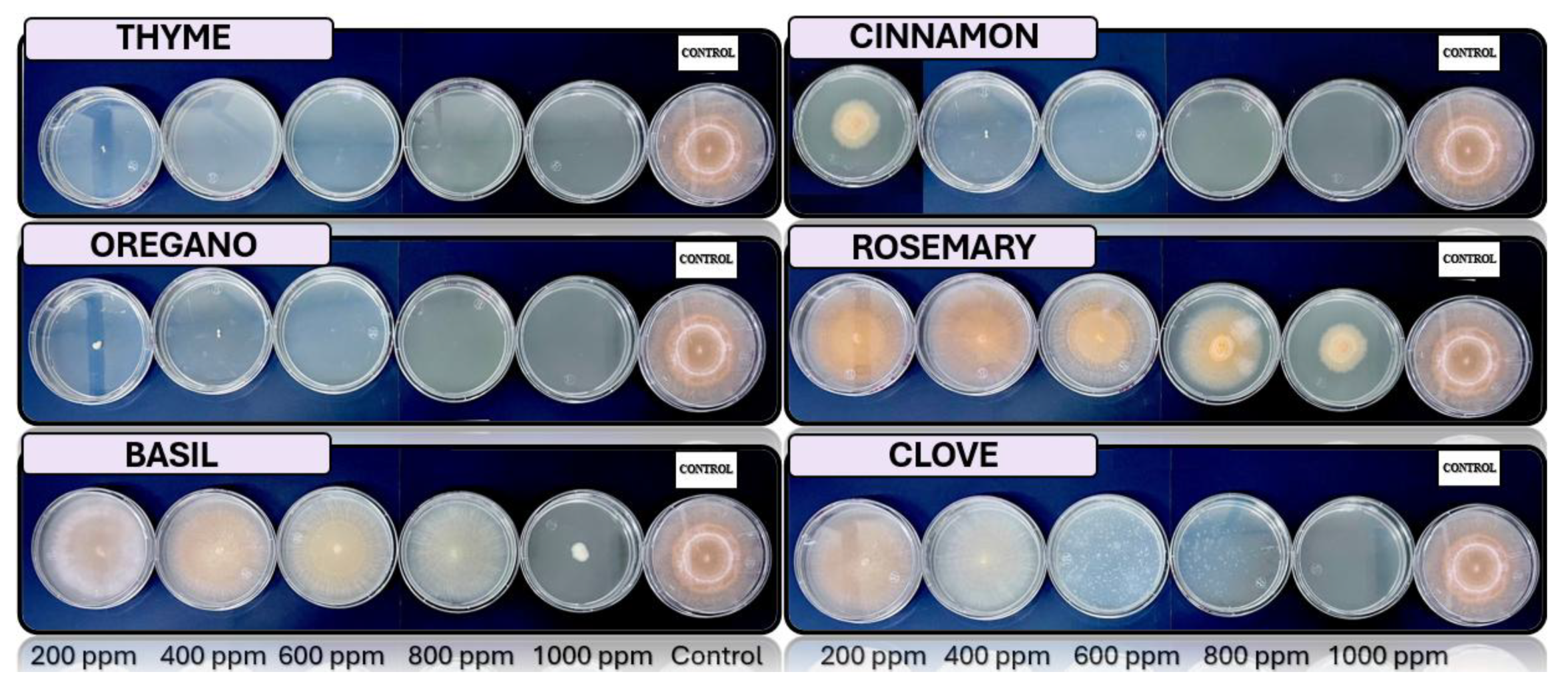

3.4. In Vitro Antifungal Activity with Essential Oils

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological Identification

4.2. Molecular Identification Through DNA Sequencing

4.3. Ex Vivo Fungal Activity

4.4. In Vitro Antifungal Activity with Essential Oils

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galan V, Rangel A, Lopez J, Hernandez JBP, Sandoval J, Rocha HS. Propagación del banano: técnicas tradicionales, nuevas tecnologías e innovaciones. Rev Bras Frutic 2018;40. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina MD, Ruales J. Postharvest Alternatives in Banana Cultivation. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Capa Benítez LB, Alaña Castillo TP, Benítez Narváez RM. Importancia de la producción de banano orgánico. Caso: Provincia de El Oro, Ecuador. Revista Universidad y Sociedad 2016;8:64–71.

- Mata Anchundia D, Suatunce Cunuhay P, Poveda Morán R. Análisis económico del banano orgánico y convencional en la provincia Los Ríos, Ecuador. Avances 2021;23:419–30.

- Aguilar-Anccota R, Arévalo-Quinde CG, Morales-Pizarro A, Galecio-Julca M, Aguilar-Anccota R, Arévalo-Quinde CG, et al. Hongos asociados a la necrosis de haces vasculares en el cultivo de banano orgánico: síntomas, aislamiento e identificación, y alternativas de manejo integrado. Scientia Agropecuaria 2021;12:249–56. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán O. El nemátodo barrenador (Radopholus similis [COBB] Thorne) del banano y plátano 2011;1.

- Smith JA, Johnson RH, Thompson L. Fungal pathogens of banana: Current understanding and management strategies. Journal of Tropical Agriculture 2018;52:1–10.

- Solis EM, Montoya CG. Fusarium wilt in bananas: A critical review of fungal pathogens and control methods. Tropical Plant Pathology 2017;42:124–35.

- Castellanos D, Algecira N, Villota C. Aspectos relevantes en el almacenamiento de banano en empaques con atmósferas modificadas. 2011 2011;12:114–34.

- Garcia M, Pérez J, Valero M. Antifungal properties of essential oils in postharvest disease control of tropical fruits. International Journal of Food Science 2021;23:250–8.

- Boulos M, Lacey M. Role of essential oils in food preservation: A review. Food Control 2020;111:203–12.

- Khan SH, Rehman S. Therapeutic and antifungal potentials of essential oils from plants. Natural Products Research 2020;34:1045–51.

- Zambonelli A, Guerrini L. Essential oils and their antifungal properties. Fungal Biology Reviews 2021;35:21–32. [CrossRef]

- Mesa V a. M, Marín P, Ocampo O, Calle J, Monsalve Z, Mesa V a. M, et al. Fungicidas a partir de extractos vegetales: una alternativa en el manejo integrado de hongos fitopatógenos. RIA Revista de Investigaciones Agropecuarias 2019;45:23–30.

- Barrera Necha LL, García Barrera LJ. Actividad antifúngica de aceites esenciales y sus compuestos sobre el crecimiento de Fusarium sp. aislado de papaya ( Carica papaya). Revista Científica UDO Agrícola 2008;8:33–41.

- López Luengo MT. El romero. Planta aromática con efectos antioxidantes. Offarm 2008;27:60–3.

- Flores-Villa E, Sáenz-Galindo A, Castañeda-Facio AO, Narro-Céspedes RI, Flores-Villa E, Sáenz-Galindo A, et al. Romero (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): su origen, importancia y generalidades de sus metabolitos secundarios. TIP Revista especializada en ciencias químico-biológicas 2020;23. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz M, Ávila J, Ruales J. Diseño de un recubrimiento comestible bioactivo para aplicarlo en la frutilla (Fragaria vesca) como proceso de postcosecha 2016;17:276–87.

- Jeri R, H C. Consideraciones epidemiológicas para el manejo de la marchitez por Fusarium (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense) del banano en la región central del Perú 2012.

- Magdama F, Monserrate-Maggi L, Serrano L, García Onofre J, Jiménez-Gasco M del M. Genetic Diversity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, the Fusarium Wilt Pathogen of Banana, in Ecuador. Plants 2020;9:1133. [CrossRef]

- Tapia C, Amaro J. Género Fusarium. Revista Chilena de Infectología 2014;31:85–6. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan R, Prabhu G, Prasad M, Mishra M, Chaudhary M, Srivastava R. Penicillium. In: Amaresan N, Senthil Kumar M, Annapurna K, Kumar K, Sankaranarayanan A, editors. Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology, Academic Press; 2020, p. 651–67. [CrossRef]

- Velásquez MA, Álvarez RM, Tamayo PJ, Carvalho CP. Evaluación in vitro de la actividad fungistática del aceite esencial de mandarina sobre el crecimiento de Penicillium sp. Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria 2014;15:7–14.

- Timmermann LA, Lopez C, Becker B. Inhibitory effects of thyme and oregano oils on fungal spore formation. International Journal of Fungal Biology 2019;29:32–40.

- Schuster A, Schmoll M. Biology and biotechnology of Trichoderma | Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2010. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-010-2632-1 (accessed August 4, 2024).

- Brotman Y, Kapuganti JG, Viterbo A. Trichoderma. Current Biology 2010;20:R390–1. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Melchor DJ, Ferrera-Cerrato R, Alarcón A, Hernández-Melchor DJ, Ferrera-Cerrato R, Alarcón A. Trichoderma: Importancia agrícola, biotecnológica y sistemas de fermentación para producir biomasa y enzimas de interés industrial. Chilean Journal of Agricultural & Animal Sciences 2019;35:98–112. [CrossRef]

- Palou L. Control integrado no contaminante de enfermedades de poscosecha (CINCEP). Nuevo paradigma para el sector español de los cítricos. Levante Agrícola 2011:173–83.

- Chang PK, Horn BW, Abe K, Gomi K. Aspergillus: Introduction. Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology: Second Edition, Elsevier Inc.; 2014, p. 77–82. [CrossRef]

- Pinto E, Silva C, Costa L. Eugenol as an antifungal agent: Mechanisms and applications. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2018;124:1089–99. [CrossRef]

- Rokas A. Aspergillus. Current Biology 2013;23:R187–8. [CrossRef]

- Burt S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2004;94:223–53. [CrossRef]

- Suppakul P, Miltz J, Sonneveld K, Bigger SW. Antimicrobial properties of basil and its possible application in food packaging. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2003;51:3197–207. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Fernández JP, Wang-Wong A, Muñoz-Fonseca M, Vargas-Fernández JP, Wang-Wong A, Muñoz-Fonseca M. Microorganismos asociados a la enfermedad conocida como pudrición suave del fruto de banano (Musa sp.) y alternativas de control microbiológicas y químicas a nivel in vitro *. Agronomía Costarricense 2022;46:61–76. [CrossRef]

- Suárez L, Rangel A. Aislamiento de microorganismos para control biológico de Moniliophthora roreri 2013;62.

- Salazar E, Hernández R, Tapia A, Gómez-Alpízar L. Identificación molecular del hongo Colletotrichum spp., aislado de banano (Musa spp) de la altura en la zona de Turrialba y determinación de su sensibilidad a fungicidas poscosecha. Agronomía Costarricense 2012;36:53–68.

- Morales R, Henríquez G. Aislamiento e identificación del moho causante de antracnosis en musa paradisiaca l. (plátano) en cooperativa san carlos, el salvador y aislamiento de mohos y levaduras con capacidad antagonista. Crea Ciencia Revista Científica 2021;13:84–94. [CrossRef]

- Toure N, Yaye T. Antifungal efficacy of plant-derived essential oils in controlling post-harvest banana disease. Tropical Fruit Research 2023;18:56–64.

- Tortora GJ, Funke BR, Case CL. Introducción a la microbiología. Ed. Médica Panamericana; 2007.

- Vanegas J Santamaría, González N Comba, Mancilla XC Pérez. Manual de Microbiología General: Principios Básicos de Laboratorio. Editorial Tadeo Lozano; 2014.

- Suárez Contreras LY. Identificación molecular de aislamientos de Moniliophthora roreri en huertos de cacao de Norte de Santander, Colombia. Acta Agronómica 2016;65:51–7. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Armijos JS. Identificación del hongo fitopatógeno Phoma spp. aislado a partir de plantas de uvilla (Physalis peruviana L.) en localidades de zona norte y centro-norte de la serranía ecuatoriana 2020.

- Castro J, Guzmán M. Identificación molecular de hongos asociados a frutos de banano en Costa Rica mediante la región ITS y análisis de secuencias. Revista de Biología Tropical 2012;60:45–58.

- Aguilar-Anccota R, Apaza-Apaza S, Maldonado E, Calle-Cheje Y, Rafael-Rutte R, Montalvo K, et al. Control in vitro e in vivo de Thielavipsis paradoxa y Collettrichum musae cn biofungicidas en frutos de banano orgánico. Manglar 2024;21:57–63. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Medina M, Ruales J. Essential Oils as an Antifungal Alternative to Control Fusarium spp., Penicillium spp., Trichoderma spp. and Aspergillus spp. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aquino-Martínez JG, Vázquez-García LM, Reyes-Reyes BG. Biocontrol in vitro e in vivo de Fusarium oxysporum Schlecht. f. sp. dianthi (Prill. y Delacr.) Snyder y Hans. con Hongos Antagonistas Nativos de la Zona Florícola de Villa Guerrero, Estado de México. Revista mexicana de fitopatología 2008;26:127–37.

- Savín-Molina J, Hernández-Montiel LG, Ceiro-Catasú W, Ávila-Quezada GD, Palacios-Espinosa A, Ruiz-Espinoza FH, et al. Caracterización morfológica y potencial de biocontrol de especies de Trichoderma aisladas de suelos del semiárido. Revista mexicana de fitopatología 2021;39:435–51. [CrossRef]

- Cayotopa-Torres J, Arevalo L, Pichis-García R, Olivera-Cayotopa D, Rimachi-Valle M, Kadir KJMD. New cadmium bioremediation agents: Trichodermaspecies native to the rhizosphere of cacao trees. Scientia Agropecuaria 2021;24:155–60. [CrossRef]

- Harman GE, Kubicek CP. Trichoderma And Gliocladium: Basic Biology, Taxonomy and Genetics. Vienna, Austria: CRC Press; 2002.

- Ortiz E, Riascos D, Angarita M, Castro O, Rivera C, Romero D, et al. Tópicos taxonómicos para el estudio del género Fusarium 2020;33:61–6.

- Smith J, Henderson R. Mycotoxins and Animal Foods. 1er ed. Glasgow, Scotland: CRC Press; 1991.

- Leslie JF, Summerell BA. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2006.

- Samson RA, others. Common Aspergillus species. Springer; 2011.

- Pitt JI, Hocking AD. Fungi and Food Spoilage. Springer; 2009.

- Pitt JI. Mycotoxins: Fumonisins. In: Motarjemi Y, editor. Encyclopedia of Food Safety, Waltham: Academic Press; 2014, p. 299–303. [CrossRef]

- Mendez RM, others. Aspergillus flavus: Aflatoxigenic species of importance. Food Control 2011;22:1472–84. [CrossRef]

- Abadias M, Teixidó N, Usall J, Viñas I. Evaluation of alternative strategies to control postharvest blue mould of apple caused by Penicillium expansum. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2008;122:25–31. [CrossRef]

- Acurio Vásconez RD, España Imbaquingo CK, Acurio Vásconez RD, España Imbaquingo CK. Aislamiento, caracterización y evaluación de Trichoderma spp. como promotor de crecimiento vegetal en pasturas de Raygrass (Lolium perenne) y trébol blanco (Trifolium repens). LA GRANJA Revista de Ciencias de la Vida 2017;25:53–61. [CrossRef]

- Boulanger R, Liu Y, Jiang Z. Synergistic effects of essential oils against fungal pathogens: Mechanisms and applications. Food Control 2021;123:107–18.

- Choi YH, Kim H, Lee S. The antifungal activity of essential oils: Mechanisms and applications in plant disease management. Phytopathology Research 2018;44:89–102.

- Zhao S, Zhang Z, Wei Y. Mechanisms of antifungal action of cinnamaldehyde. Phytochemistry 2020;173:112112.

- Farias APP, Monteiro O dos S, da Silva JKR, Figueiredo PLB, Rodrigues AAC, Monteiro IN, et al. Chemical composition and biological activities of two chemotype-oils from Cinnamomum verum J. Presl growing in North Brazil. J Food Sci Technol 2020;57:3176–83.

- Sadiq MB, Hameed S, Tufail S. Role of essential oils in the inhibition of fungal pathogens. Microbial Pathogenesis 2021;160:105113. [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante HA, Filho AC, Rocha F. Essential oils as alternative antifungal agents. Mycology 2019;60:358–66.

| Organism | Fragment | % Identity |

| Fusarium longicornicola | ITS | 99.08 % |

| Penicillium expansum | ITS | 99.76 % |

| Trichoderma pseudokoringii | ITS | 99.18 % |

| Aspergillus flavus | ITS | 99.33 % |

| Essential oil | Fungus | Concentration [ppm] | ||||

| 200 | 400 | 600 | 800 | 1000 | ||

| Cinnamon | Trichoderma spp. | + | + | - | - | - |

| Penicillium spp. | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Aspergillus spp. | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium spp. | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Clove | Trichoderma spp. | + | - | - | - | - |

| Penicillium spp. | + | + | + | + | - | |

| Aspergillus spp. | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium spp. | + | + | - | - | - | |

| Basil | Trichoderma spp. | + | + | + | + | + |

| Penicillium spp. | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Aspergillus spp. | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Fusarium spp. | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Oregano | Trichoderma spp. | - | - | - | - | - |

| Penicillium spp. | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Aspergillus spp. | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium spp. | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Rosemary | Trichoderma spp. | + | + | + | + | + |

| Penicillium spp. | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Aspergillus spp. | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Fusarium spp. | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Thyme | Trichoderma spp. | + | - | - | - | - |

| Penicillium spp. | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Aspergillus spp. | + | - | - | - | - | |

| Fusarium spp. | - | - | - | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).