Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

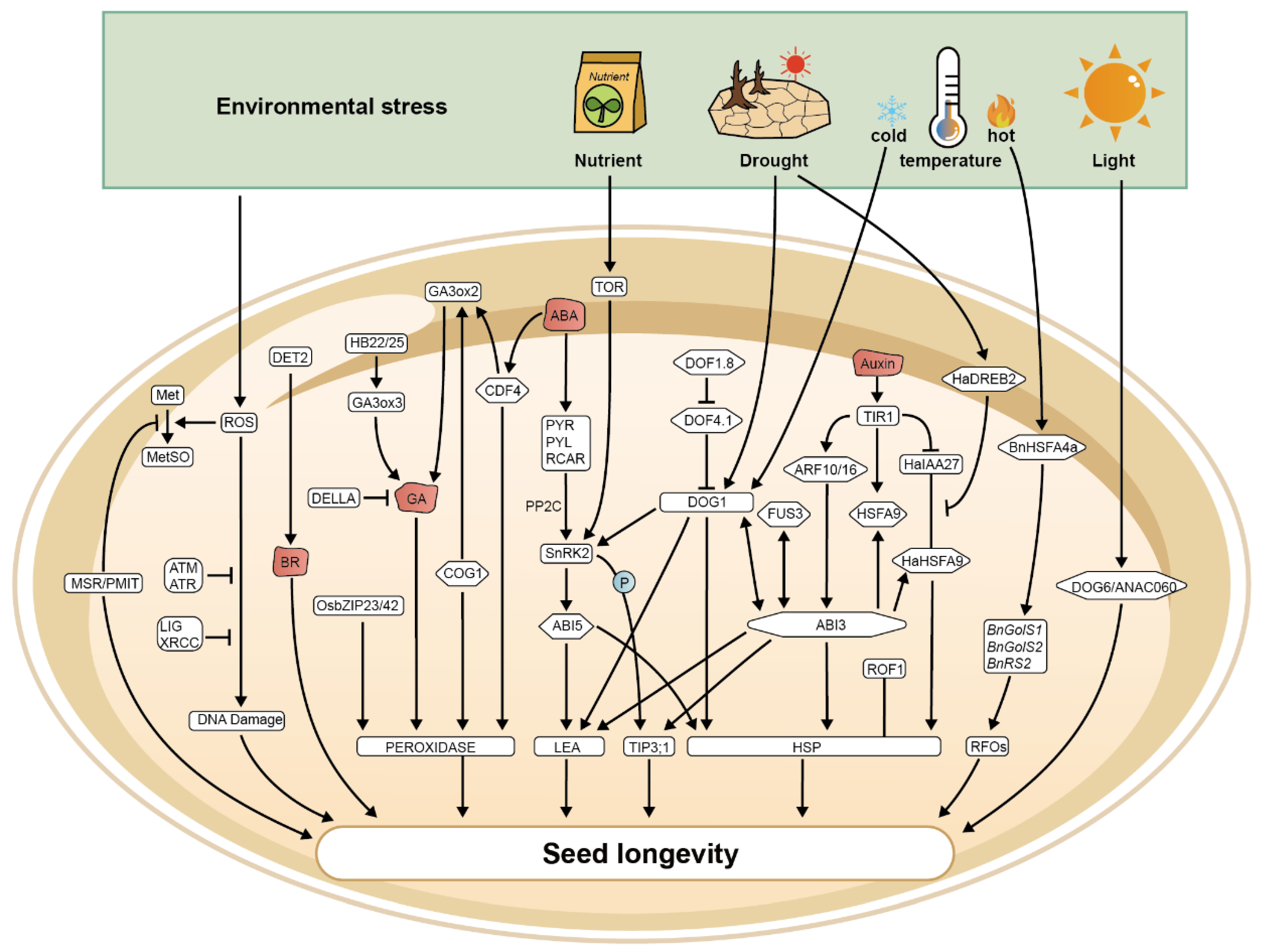

2. Molecular Genetics Governing Seed Longevity

2.1. Transcription Factors in Regulating Seed Longevity

2.2. Impact of DNA Damage Repair on Seed Longevity

2.3. Role of Protein Repair or Homeostasis in Maintaining Seed Longevity

2.4. Role of RFOs in Regulating Seed Longeivity

2.5. Hormonal Regulation of Seed Longevity

2.5.1. ABA: A Central Regulator of Seed Longevity

2.5.2. Impact of Auxin on Seed Longevity

2.5.3. Influence of Gibberellins (GA) on Seed Longevity

2.6. Seed Dormancy and Longevity: Positive and Negative Correlations

3. Environmental Regulation of Seed Longevity

3.1. Influence of Temperature on Seed Longevity

3.2. Water Availability

3.3. Light Exposure

3.4. Nutrient Supply

3.5. Oxygen Level

4. Strategies to Enhance Seed Longevity

4.1. Extension of Seed Longevity Through Molecular Genetics

4.2. Extending Seed Longevity Through Seed Priming

4.3. Revitalizing Old Seeds

5. Challenges, Questions and Approaches

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SLAG | SEED LONGEVITY-ASSOCIATED GENE |

| ABI3 | ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE3 |

| TIP3;1 | TONOPLAST INTRINSIC PROTEIN 3;1 |

| ROF1 | ROTAMASE FKBP 1 |

| DREB2 | DROUGHT RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTOR 2 |

| IAA27 | AUXIN-RESPONSIVE PROTEIN 27 |

| DOG1 | DELAY OF GERMINATION |

| COG1 | COGWHEEL1 |

| CDF4 | CYCLING DOF FACTOR 4 |

| PER1A | PEROXIDASE 1A |

| ATM | ATAXIA TELANGIECTASIA MUTATED |

| ATR | ATM AND RAD3-RELATED |

| SOG1 | SUPPRESSOR OF GAMMA 1 |

| LIG4 | DNA LIGASE 4 |

| XRCC2 | X-RAY REPAIR CROSS COMPLEMENTING 2 |

| PARP1 | POLY(ADP-RIBOSE) POLYMERASE 1 |

| ERCC1 | EXCISION REPAIR CROSS COMPLEMENT-ING-GROUP 1 |

| 8-OXOG | 8-OXOGUANINE |

| DSBS | double-strand breaks |

| HR | homologous recombination |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SnRK2 | SUCROSE NON-FERMENTING 1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE 2 |

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| EM1 | EARLY METHIONINE1 |

| AtHB25 | ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA HOMEOBOX 25 |

| TOR | Target of Rapamycin |

| SOD | SUPEROXIDE DISMUTASE |

| CAT | CATALASE |

| POD | PEROXIDASES |

References

- Sano, N.; Rajjou, L.; North, H.M.; Debeaujon, I.; Marion-Poll, A.; Seo, M. Staying Alive: Molecular Aspects of Seed Longevity. Plant Cell Physiol 2016, 57, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, R.C.; Bradford, K.J.; Khanday, I. Seed germination and vigor: ensuring crop sustainability in a changing climate. Heredity (Edinb) 2022, 128, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramtekey, V.; Cherukuri, S.; Kumar, S.; V, S.K.; Sheoran, S.; K, U.B.; K, B.N.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.N.; Singh, H.V. Seed Longevity in Legumes: Deeper Insights Into Mechanisms and Molecular Perspectives. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 918206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, B.; Gao, J.; Chen, W.; Gong, X.; Ge, G. The Effects of Climate Change on Landscape Connectivity and Genetic Clusters in a Small Subtropical and Warm-Temperate Tree. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 671336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.; Pence, V.C. The unique role of seed banking and cryobiotechnologies in plant conservation. Plants People Planet 2021, 3, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatkamp, A.; Cochrane, A.; Commander, L.; Guja, L.K.; Jimenez-Alfaro, B.; Larson, J.; Nicotra, A.; Poschlod, P.; Silveira, F.A.O.; Cross, A.T.; et al. A research agenda for seed-trait functional ecology. New Phytol 2019, 221, 1764–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajjou, L.; Debeaujon, I. Seed longevity: survival and maintenance of high germination ability of dry seeds. C R Biol 2008, 331, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitink, J.; Leprince, O. Intracellular glasses and seed survival in the dry state. C R Biol 2008, 331, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallon, S.; Solowey, E.; Cohen, Y.; Korchinsky, R.; Egli, M.; Woodhatch, I.; Simchoni, O.; Kislev, M. Germination, genetics, and growth of an ancient date seed. Science 2008, 320, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen-Miller, J.; Lindner, P.; Xie, Y.; Villa, S.; Wooding, K.; Clarke, S.G.; Loo, R.R.; Loo, J.A. Thermal-stable proteins of fruit of long-living Sacred Lotus Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn var. China Antique. Trop Plant Biol 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman, J.C.; Cigliano, E.M. New carbon-14 evidence for six hundred years old Canna compacta seed. Nature 1971, 232, 568–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Botany. Patience yields secrets of seed longevity. Science 2001, 291, 1884–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, M.A.R.; Afzal, I.; Borner, A. Genetic Aspects and Molecular Causes of Seed Longevity in Plants-A Review. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Keizer, P.; van Eeuwijk, F.; Smeekens, S.; Bentsink, L. Natural variation for seed longevity and seed dormancy are negatively correlated in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2012, 160, 2083–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, M.; Kodde, J.; Pistrick, S.; Mascher, M.; Borner, A.; Groot, S.P. Barley Seed Aging: Genetics behind the Dry Elevated Pressure of Oxygen Aging and Moist Controlled Deterioration. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzon, F.; Gianella, M.; Velazquez Juarez, J.A.; Sanchez Cano, C.; Costich, D.E. Seed longevity of maize conserved under germplasm bank conditions for up to 60 years. Ann Bot 2021, 127, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agacka-Moldoch, M.; Arif, M.A.; Lohwasser, U.; Doroszewska, T.; Qualset, C.O.; Borner, A. The inheritance of wheat grain longevity: a comparison between induced and natural ageing. J Appl Genet 2016, 57, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwember, A.R.; Bradford, K.J. Quantitative trait loci associated with longevity of lettuce seeds under conventional and controlled deterioration storage conditions. J Exp Bot 2010, 61, 4423–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arif, M.A.; Nagel, M.; Lohwasser, U.; Borner, A. Genetic architecture of seed longevity in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J Biosci 2017, 42, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lin, C.; Pan, R.; Ma, W.; Zheng, Y.; Guan, Y.; Hu, J. Suppression of LOX activity enhanced seed vigour and longevity of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) seeds during storage. Conserv Physiol 2018, 6, coy047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, S.; Liu, X.; Xue, H.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Functional characterization of BnHSFA4a as a heat shock transcription factor in controlling the re-establishment of desiccation tolerance in seeds. J Exp Bot 2017, 68, 2361–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Velasco-Punzalan, M.; Pacleb, M.; Valdez, R.; Kretzschmar, T.; McNally, K.L.; Ismail, A.M.; Cruz, P.C.S.; Sackville Hamilton, N.R.; Hay, F.R. Variation in seed longevity among diverse Indica rice varieties. Ann Bot 2019, 124, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Tan, S.; Cao, J.; Wang, H.L.; Luo, J.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z. Leaf Senescence Database v5.0: A Comprehensive Repository for Facilitating Plant Senescence Research. J Mol Biol, 6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, K.; Pajoro, A.; Angenent, G.C. Regulation of transcription in plants: mechanisms controlling developmental switches. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.W.; Abeysinghe, J.K.; Kamali, M. Regulating the Regulators: The Control of Transcription Factors in Plant Defense Signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.Y.; Kagale, S.; Ferrie, A.M.R. Multifaceted roles of transcription factors during plant embryogenesis. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1322728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clerkx, E.J.; El-Lithy, M.E.; Vierling, E.; Ruys, G.J.; Blankestijn-De Vries, H.; Groot, S.P.; Vreugdenhil, D.; Koornneef, M. Analysis of natural allelic variation of Arabidopsis seed germination and seed longevity traits between the accessions Landsberg erecta and Shakdara, using a new recombinant inbred line population. Plant Physiol 2004, 135, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parcy, F.; Valon, C.; Kohara, A.; Misera, S.; Giraudat, J. The ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE3, FUSCA3, and LEAFY COTYLEDON1 loci act in concert to control multiple aspects of Arabidopsis seed development. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monke, G.; Altschmied, L.; Tewes, A.; Reidt, W.; Mock, H.P.; Baumlein, H.; Conrad, U. Seed-specific transcription factors ABI3 and FUS3: molecular interaction with DNA. Planta 2004, 219, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotak, S.; Vierling, E.; Baumlein, H.; von Koskull-Doring, P. A novel transcriptional cascade regulating expression of heat stress proteins during seed development of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Sun, W. Arabidopsis seed-specific vacuolar aquaporins are involved in maintaining seed longevity under the control of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 3. J Exp Bot 2015, 66, 4781–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, R.; Deng, X. Arabidopsis HSFA9 acts as a regulator of heat response gene expression and the acquisition of thermotolerance and seed longevity. Plant Cell Physiol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiri, D.; Breiman, A. Arabidopsis ROF1 (FKBP62) modulates thermotolerance by interacting with HSP90.1 and affecting the accumulation of HsfA2-regulated sHSPs. Plant J 2009, 59, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoguera, C.; Personat, J.M.; Prieto-Dapena, P.; Jordano, J. Heat shock transcription factors involved in seed desiccation tolerance and longevity retard vegetative senescence in transgenic tobacco. Planta 2015, 242, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier, J.; Lalanne, D.; Pelletier, S.; Torres-Jerez, I.; Righetti, K.; Bandyopadhyay, K.; Leprince, O.; Chatelain, E.; Vu, B.L.; Gouzy, J.; et al. A regulatory network-based approach dissects late maturation processes related to the acquisition of desiccation tolerance and longevity of Medicago truncatula seeds. Plant Physiol 2013, 163, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoguera, C.; Prieto-Dapena, P.; Diaz-Martin, J.; Espinosa, J.M.; Carranco, R.; Jordano, J. The HaDREB2 transcription factor enhances basal thermotolerance and longevity of seeds through functional interaction with HaHSFA9. BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranco, R.; Espinosa, J.M.; Prieto-Dapena, P.; Almoguera, C.; Jordano, J. Repression by an auxin/indole acetic acid protein connects auxin signaling with heat shock factor-mediated seed longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 21908–21913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Sun, H. DOF transcription factors: Specific regulators of plant biological processes. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1044918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninoles, R.; Ruiz-Pastor, C.M.; Arjona-Mudarra, P.; Casan, J.; Renard, J.; Bueso, E.; Mateos, R.; Serrano, R.; Gadea, J. Transcription Factor DOF4.1 Regulates Seed Longevity in Arabidopsis via Seed Permeability and Modulation of Seed Storage Protein Accumulation. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 915184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentsink, L.; Jowett, J.; Hanhart, C.J.; Koornneef, M. Cloning of DOG1, a quantitative trait locus controlling seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 17042–17047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Barral, N.; Rodriguez-Gacio, M.D.C.; Matilla, A.J. Delay of Germination-1 (DOG1): A Key to Understanding Seed Dormancy. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, J.; Martinez-Almonacid, I.; Sonntag, A.; Molina, I.; Moya-Cuevas, J.; Bissoli, G.; Munoz-Bertomeu, J.; Faus, I.; Ninoles, R.; Shigeto, J.; et al. PRX2 and PRX25, peroxidases regulated by COG1, are involved in seed longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ 2020, 43, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueso, E.; Munoz-Bertomeu, J.; Campos, F.; Martinez, C.; Tello, C.; Martinez-Almonacid, I.; Ballester, P.; Simon-Moya, M.; Brunaud, V.; Yenush, L.; et al. Arabidopsis COGWHEEL1 links light perception and gibberellins with seed tolerance to deterioration. Plant J 2016, 87, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righetti, K.; Vu, J.L.; Pelletier, S.; Vu, B.L.; Glaab, E.; Lalanne, D.; Pasha, A.; Patel, R.V.; Provart, N.J.; Verdier, J.; et al. Inference of Longevity-Related Genes from a Robust Coexpression Network of Seed Maturation Identifies Regulators Linking Seed Storability to Biotic Defense-Related Pathways. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 2692–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, J.; Ninoles, R.; Martinez-Almonacid, I.; Gayubas, B.; Mateos-Fernandez, R.; Bissoli, G.; Bueso, E.; Serrano, R.; Gadea, J. Identification of novel seed longevity genes related to oxidative stress and seed coat by genome-wide association studies and reverse genetics. Plant Cell Environ 2020, 43, 2523–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueso, E.; Munoz-Bertomeu, J.; Campos, F.; Brunaud, V.; Martinez, L.; Sayas, E.; Ballester, P.; Yenush, L.; Serrano, R. ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA HOMEOBOX25 uncovers a role for Gibberellins in seed longevity. Plant Physiol 2014, 164, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregis, V.; Sessa, A.; Colombo, L.; Kater, M.M. AGL24, SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE, and APETALA1 redundantly control AGAMOUS during early stages of flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Neto, L.G.; Rossini, B.C.; Marino, C.L.; Toorop, P.E.; Silva, E.A.A. Comparative Seeds Storage Transcriptome Analysis of Astronium fraxinifolium Schott, a Threatened Tree Species from Brazil. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Q.; Xu, D.Y.; Sui, Y.P.; Ding, X.H.; Song, X.J. A multiomic study uncovers a bZIP23-PER1A-mediated detoxification pathway to enhance seed vigor in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, K.S.; Osborne, D.J. DNA lesions occur with loss of viability in embryos of ageing rye seed. Nature 1978, 272, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterworth, W.; Balobaid, A.; West, C. Seed longevity and genome damage. Biosci Rep 2024, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterworth, W.M.; Footitt, S.; Bray, C.M.; Finch-Savage, W.E.; West, C.E. DNA damage checkpoint kinase ATM regulates germination and maintains genome stability in seeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 9647–9652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterworth, W.M.; Latham, R.; Wang, D.; Alsharif, M.; West, C.E. Seed DNA damage responses promote germination and growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2202172119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterworth, W.M.; Masnavi, G.; Bhardwaj, R.M.; Jiang, Q.; Bray, C.M.; West, C.E. A plant DNA ligase is an important determinant of seed longevity. Plant J 2010, 63, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y.; Tsang, E.W.; Jiang, L.; Wu, K.; Huang, S. Overexpression of AtOGG1, a DNA glycosylase/AP lyase, enhances seed longevity and abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 2012, 63, 4107–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.E.; Waterworth, W.; West, C.E.; Foyer, C.H. WHIRLY proteins maintain seed longevity by effects on seed oxygen signalling during imbibition. Biochem J 2023, 480, 941–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J.A.; Melo, J.A.; Cheung, S.K.; Vaze, M.B.; Haber, J.E.; Toczyski, D.P. DNA breaks promote genomic instability by impeding proper chromosome segregation. Curr Biol 2004, 14, 2096–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culligan, K.M.; Robertson, C.E.; Foreman, J.; Doerner, P.; Britt, A.B. ATR and ATM play both distinct and additive roles in response to ionizing radiation. Plant J 2006, 48, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falck, J.; Coates, J.; Jackson, S.P. Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage. Nature 2005, 434, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.; Lyu, J.I.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Nam, H.G.; Woo, H.R. ATM suppresses leaf senescence triggered by DNA double-strand break through epigenetic control of senescence-associated genes in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 2020, 227, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, J.E. Partners and pathwaysrepairing a double-strand break. Trends Genet 2000, 16, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeevan Kumar, S.P.; Rajendra Prasad, S.; Banerjee, R.; Thammineni, C. Seed birth to death: dual functions of reactive oxygen species in seed physiology. Ann Bot 2015, 116, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtman, E.R.; Berlett, B.S. Reactive oxygen-mediated protein oxidation in aging and disease. Chem Res Toxicol 1997, 10, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermolaieva, O.; Xu, R.; Schinstock, C.; Brot, N.; Weissbach, H.; Heinemann, S.H.; Hoshi, T. Methionine sulfoxide reductase A protects neuronal cells against brief hypoxia/reoxygenation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004, 101, 1159–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovitz, J.; Berlett, B.S.; Poston, J.M.; Stadtman, E.R. The yeast peptide-methionine sulfoxide reductase functions as an antioxidant in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 9585–9589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazra, A.; Varshney, V.; Verma, P.; Kamble, N.U.; Ghosh, S.; Achary, R.K.; Gautam, S.; Majee, M. Methionine sulfoxide reductase B5 plays a key role in preserving seed vigor and longevity in rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol 2022, 236, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatelain, E.; Satour, P.; Laugier, E.; Ly Vu, B.; Payet, N.; Rey, P.; Montrichard, F. Evidence for participation of the methionine sulfoxide reductase repair system in plant seed longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 3633–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitink, J.; Leger, J.J.; Guisle, I.; Vu, B.L.; Wuilleme, S.; Lamirault, G.; Le Bars, A.; Le Meur, N.; Becker, A.; Kuster, H.; et al. Transcriptome profiling uncovers metabolic and regulatory processes occurring during the transition from desiccation-sensitive to desiccation-tolerant stages in Medicago truncatula seeds. Plant J 2006, 47, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellión, M.; Matiacevich, S.; Buera, P.; Maldonado, S. Protein deterioration and longevity of quinoa seeds during long-term storage. Food Chem 2010, 121, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oge, L.; Bourdais, G.; Bove, J.; Collet, B.; Godin, B.; Granier, F.; Boutin, J.P.; Job, D.; Jullien, M.; Grappin, P. Protein repair L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase 1 is involved in both seed longevity and germination vigor in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 3022–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudgett, M.B.; Lowenson, J.D.; Clarke, S. Protein repair L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase in plants. Phylogenetic distribution and the accumulation of substrate proteins in aged barley seeds. Plant Physiol 1997, 115, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petla, B.P.; Kamble, N.U.; Kumar, M.; Verma, P.; Ghosh, S.; Singh, A.; Rao, V.; Salvi, P.; Kaur, H.; Saxena, S.C.; et al. Rice PROTEIN l-ISOASPARTYL METHYLTRANSFERASE isoforms differentially accumulate during seed maturation to restrict deleterious isoAsp and reactive oxygen species accumulation and are implicated in seed vigor and longevity. New Phytol 2016, 211, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Kaur, H.; Petla, B.P.; Rao, V.; Saxena, S.C.; Majee, M. PROTEIN L-ISOASPARTYL METHYLTRANSFERASE2 is differentially expressed in chickpea and enhances seed vigor and longevity by reducing abnormal isoaspartyl accumulation predominantly in seed nuclear proteins. Plant Physiol 2013, 161, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Hatzianestis, I.H.; Pfirrmann, T.; Reza, S.H.; Minina, E.A.; Moazzami, A.; Stael, S.; Gutierrez-Beltran, E.; Pitsili, E.; Dormann, P.; et al. Seed longevity is controlled by metacaspases. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.; Saxena, S.C.; Petla, B.P.; Kamble, N.U.; Kaur, H.; Verma, P.; Rao, V.; Ghosh, S.; Majee, M. Differentially expressed galactinol synthase(s) in chickpea are implicated in seed vigor and longevity by limiting the age induced ROS accumulation. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 35088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Dirk, L.M.A.; Goodman, J.; Downie, A.B.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Zhao, T. Regulation of Seed Vigor by Manipulation of Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides in Maize and Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant 2017, 10, 1540–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Qi, J.; Hao, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Dirk, L.M.A.; Downie, A.B.; Zhao, T. ZmDREB1A Regulates RAFFINOSE SYNTHASE Controlling Raffinose Accumulation and Plant Chilling Stress Tolerance in Maize. Plant Cell Physiol 2020, 61, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, P.; Varshney, V.; Majee, M. Raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs): role in seed vigor and longevity. Biosci Rep 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Vidigal, D.; Willems, L.; van Arkel, J.; Dekkers, B.J.W.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Bentsink, L. Galactinol as marker for seed longevity. Plant Sci 2016, 246, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinson, C.C.; Mota, A.P.Z.; Porto, B.N.; Oliveira, T.N.; Sampaio, I.; Lacerda, A.L.; Danchin, E.G.J.; Guimaraes, P.M.; Williams, T.C.R.; Brasileiro, A.C.M. Characterization of raffinose metabolism genes uncovers a wild Arachis galactinol synthase conferring tolerance to abiotic stresses. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 15258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Dirk, L.M.A.; Downie, A.B.; Zhao, T. ZmAGA1 Hydrolyzes RFOs Late during the Lag Phase of Seed Germination, Shifting Sugar Metabolism toward Seed Germination Over Seed Aging Tolerance. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 11606–11615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locascio, A.; Roig-Villanova, I.; Bernardi, J.; Varotto, S. Current perspectives on the hormonal control of seed development in Arabidopsis and maize: a focus on auxin. Frontiers in Plant Science 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerkx, E.J.; Vries, H.B.; Ruys, G.J.; Groot, S.P.; Koornneef, M. Characterization of green seed, an enhancer of abi3-1 in Arabidopsis that affects seed longevity. Plant Physiol 2003, 132, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehmani, M.S.; Aziz, U.; Xian, B.; Shu, K. Seed Dormancy and Longevity: A Mutual Dependence or a Trade-Off? Plant Cell Physiol 2022, 63, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R.R.; Gampala, S.S.; Rock, C.D. Abscisic acid signaling in seeds and seedlings. Plant Cell 2002, 14 Suppl, S15–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, G.J.; Bressan, R.A.; Song, C.P.; Zhu, J.K.; Zhao, Y. Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J Integr Plant Biol 2020, 62, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, Q.; Yang, H.Q.; Luan, S.; Li, J.; He, Z.H. Auxin controls seed dormancy through stimulation of abscisic acid signaling by inducing ARF-mediated ABI3 activation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 15485–15490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellizzaro, A.; Neveu, M.; Lalanne, D.; Ly Vu, B.; Kanno, Y.; Seo, M.; Leprince, O.; Buitink, J. A role for auxin signaling in the acquisition of longevity during seed maturation. New Phytol 2020, 225, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, L.; He, W.; Lin, Q.; Yu, F.; Wang, L. Transcriptome-Wide Characterization of Seed Aging in Rice: Identification of Specific Long-Lived mRNAs for Seed Longevity. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 857390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeaujon, I.; Koornneef, M. Gibberellin requirement for Arabidopsis seed germination is determined both by testa characteristics and embryonic abscisic acid. Plant Physiol 2000, 122, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirredda, M.; Fananas-Pueyo, I.; Onate-Sanchez, L.; Mira, S. Seed Longevity and Ageing: A Review on Physiological and Genetic Factors with an Emphasis on Hormonal Regulation. Plants (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, N.; Kim, J.S.; Onda, Y.; Nomura, T.; Mochida, K.; Okamoto, M.; Seo, M. RNA-Seq using bulked recombinant inbred line populations uncovers the importance of brassinosteroid for seed longevity after priming treatments. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debeaujon, I.; Leon-Kloosterziel, K.M.; Koornneef, M. Influence of the testa on seed dormancy, germination, and longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2000, 122, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, J.; Piskurewicz, U.; Loubery, S.; Utz-Pugin, A.; Bailly, C.; Mene-Saffrane, L.; Lopez-Molina, L. An Endosperm-Associated Cuticle Is Required for Arabidopsis Seed Viability, Dormancy and Early Control of Germination. PLoS Genet 2015, 11, e1005708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, S.E.; Gilliland, L.U.; Magallanes-Lundback, M.; Pollard, M.; DellaPenna, D. Vitamin E is essential for seed longevity and for preventing lipid peroxidation during germination. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymarie, J.; Vitkauskaite, G.; Hoang, H.H.; Gendreau, E.; Chazoule, V.; Meimoun, P.; Corbineau, F.; El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H.; Bailly, C. Role of reactive oxygen species in the regulation of Arabidopsis seed dormancy. Plant Cell Physiol 2012, 53, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipatpongpinyo, W.; Korkmaz, U.; Wu, H.; Kena, A.; Ye, H.; Feng, J.; Gu, X.Y. Assembling seed dormancy genes into a system identified their effects on seedbank longevity in weedy rice. Heredity (Edinb) 2020, 124, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penfield, S.; Gilday, A.D.; Halliday, K.J.; Graham, I.A. DELLA-mediated cotyledon expansion breaks coat-imposed seed dormancy. Curr Biol 2006, 16, 2366–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, M.; Kuwahara, A.; Seo, M.; Kushiro, T.; Asami, T.; Hirai, N.; Kamiya, Y.; Koshiba, T.; Nambara, E. CYP707A1 and CYP707A2, which encode abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylases, are indispensable for proper control of seed dormancy and germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2006, 141, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Yao, X.; Ye, T.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Yin, X.; Wu, Y. Arabidopsis Aspartic Protease ASPG1 Affects Seed Dormancy, Seed Longevity and Seed Germination. Plant Cell Physiol 2018, 59, 1415–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinsmeister, J.; Leprince, O.; Buitink, J. Molecular and environmental factors regulating seed longevity. Biochem J 2020, 477, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, F.; Luo, X.; Dai, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yang, W.; Shu, K. A matter of life and death: Molecular, physiological, and environmental regulation of seed longevity. Plant Cell Environ 2020, 43, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebach, J.; Nagel, M.; Borner, A.; Altmann, T.; Riewe, D. Age-dependent loss of seed viability is associated with increased lipid oxidation and hydrolysis. Plant Cell Environ 2020, 43, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, C.; Ballesteros, D.; Vertucci, V.A. Structural mechanics of seed deterioration: Standing the test of time. Plant Science 2010, 179, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probert, R.J.; Daws, M.I.; Hay, F.R. Ecological correlates of ex situ seed longevity: a comparative study on 195 species. Ann Bot 2009, 104, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daws, M.I.; Kabadajic, A.; Manger, K.; Kranner, I. Extreme thermo-tolerance in seeds of desert succulents is related to maximum annual temperature. S Afr J Bot 2007, 73, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.B. The seed microbiome: Origins, interactions, and impacts. Plant Soil 2018, 422, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramtekey, V.; Cherukuri, S.; Kumar, S.; Sripathy, K.V.; Sheoran, S.; Udaya, B.K.; Bhojaraja, N.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, A.N.; Singh, H.V. Seed Longevity in Legumes: Deeper Insights Into Mechanisms and Molecular Perspectives. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, B.J.; He, H.; Hanson, J.; Willems, L.A.; Jamar, D.C.; Cueff, G.; Rajjou, L.; Hilhorst, H.W.; Bentsink, L. The Arabidopsis DELAY OF GERMINATION 1 gene affects ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) expression and genetically interacts with ABI3 during Arabidopsis seed development. Plant J 2016, 85, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphey, M.; Kovach, K.; Elnacash, T.; He, H.Z.; Bentsink, L.; Donohue, K. -imposed dormancy mediates germination responses to temperature cues. Environ Exp Bot 2015, 112, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, C.; Wheeler, L.M.; Grotenhuis, J.M. Longevity of seeds stored in a genebank: species characteristics. Seed Sci Res 2005, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernareggi, G.; Carbognani, M.; Petraglia, A.; Mondoni, A. Climate warming could increase seed longevity of alpine snowbed plants. Alpine Bot 2015, 125, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.C.; Bradford, K.J.; Khanday, I. Seed germination and vigor: ensuring crop sustainability in a changing climate. Heredity 2022, 128, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.J.M.; Pallavi, M.; Bharathi, Y.; Priya, P.B.; Sujatha, P.; Prabhavathi, K. Insights into mechanisms of seed longevity in soybean: a review. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballesteros, D.; Pritchard, H.W.; Walters, C. Dry architecture: towards the understanding of the variation of longevity in desiccation-tolerant germplasm. Seed Sci Res 2020, 30, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.H.; Yadav, G. Effect of simulated rainfall during wheat seed development and maturation on subsequent seed longevity is reversible. Seed Sci Res 2016, 26, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitbrecht, K.; Muller, K.; Leubner-Metzger, G. First off the mark: early seed germination. J Exp Bot 2011, 62, 3289–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackira, A.M.; Sarath, N.G.; Aswathi, K.P.R.; Pardha-Saradhi, P.; Puthur, J.T. Green seed photosynthesis: What is it? What do we know about it? Where to go? Plant Physiology Reports 2022, 27, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Lima, J.J.; Buitink, J.; Lalanne, D.; Rossi, R.F.; Pelletier, S.; da Silva, E.A.A.; Leprince, O. Molecular characterization of the acquisition of longevity during seed maturation in soybean. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0180282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffo, A.; Bosco, N.; Pagano, A.; Balestrazzi, A.; Macovei, A. Noninvasive Methods to Detect Reactive Oxygen Species as a Proxy of Seed Quality. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.; Kranner, I.; Neumann, K.; Rolletschek, H.; Seal, C.E.; Colville, L.; Fernandez-Marin, B.; Borner, A. Genome-wide association mapping and biochemical markers reveal that seed ageing and longevity are intricately affected by genetic background and developmental and environmental conditions in barley. Plant Cell Environ 2015, 38, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; de Souza Vidigal, D.; Snoek, L.B.; Schnabel, S.; Nijveen, H.; Hilhorst, H.; Bentsink, L. Interaction between parental environment and genotype affects plant and seed performance in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 2014, 65, 6603–6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosnoblet, C.; Aubry, C.; Leprince, O.; Vu, B.L.; Rogniaux, H.; Buitink, J. The regulatory gamma subunit SNF4b of the sucrose non-fermenting-related kinase complex is involved in longevity and stachyose accumulation during maturation of Medicago truncatula seeds. Plant J 2007, 51, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.P.J.; Chintagunta, A.D.; Reddy, Y.M.; Rajjou, L.; Garlapati, V.K.; Agarwal, D.K.; Prasad, S.R.; Simal-Gandara, J. Implications of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in seed physiology for sustainable crop productivity under changing climate conditions. Curr Plant Biol 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, G.; Willems, L.A.J.; Kodde, J.; Groot, S.P.C.; Bentsink, L. Evaluating the EPPO method for seed longevity analyses in Arabidopsis. Plant Sci 2020, 301, 110644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, M.B.; Hill, L.M.; Walters, C. The kinetics of ageing in dry-stored seeds: a comparison of viability loss and RNA degradation in unique legacy seed collections. Ann Bot 2019, 123, 1133–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.J.M.; Pallavi, M.; Bharathi, Y.; Priya, P.B.; Sujatha, P.; Prabhavathi, K. Insights into mechanisms of seed longevity in soybean: a review. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1206318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Benito, M.E.; Pérez-García, F.; Tejeda, G.; Gómez-Campo, C. Effect of the gaseous environment and water content on seed viability of four Brassicaceae species after 36 years storage. Seed Sci Technol 2011, 39, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C.; El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H.; Corbineau, F. From intracellular signaling networks to cell death: the dual role of reactive oxygen species in seed physiology. C R Biol 2008, 331, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Olvera-Carrillo, Y.; Garciarrubio, A.; Campos, F.; Covarrubias, A.A. The enigmatic LEA proteins and other hydrophilins. Plant Physiol 2008, 148, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Perry, S.E. Identification of direct targets of FUSCA3, a key regulator of Arabidopsis seed development. Plant Physiol 2013, 161, 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugliani, M.; Rajjou, L.; Clerkx, E.J.; Koornneef, M.; Soppe, W.J. Natural modifiers of seed longevity in the Arabidopsis mutants abscisic acid insensitive3-5 (abi3-5) and leafy cotyledon1-3 (lec1-3). New Phytol 2009, 184, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, T.J.; Vaissayre, V.; Paszkiewicz, G.; Clavijo, F.; Kelemen, Z.; Michaud, C.; Lepiniec, L.C.; Dubreucq, B.; Zhou, D.X.; Devic, M. Regulation of FUSCA3 Expression During Seed Development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol 2019, 60, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, X.; Cai, Q.; He, W.; Xie, H.; Zhang, J. The lipoxygenase OsLOX10 affects seed longevity and resistance to saline-alkaline stress during rice seedlings. Plant Mol Biol 2023, 111, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Lal, N.K.; Lin, Z.D.; Ma, S.; Liu, J.; Castro, B.; Toruno, T.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Coaker, G. Regulation of reactive oxygen species during plant immunity through phosphorylation and ubiquitination of RBOHD. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marthandan, V.; Geetha, R.; Kumutha, K.; Renganathan, V.G.; Karthikeyan, A.; Ramalingam, J. Seed Priming: A Feasible Strategy to Enhance Drought Tolerance in Crop Plants. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, P.; Gupta, M. Micronutrient seed priming: new insights in ameliorating heavy metal stress. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022, 29, 58590–58606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, D.T.; Carbone, M. Seed Priming with Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles to Enhance Crop Tolerance to Environmental Stresses. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Wang, Y.; Samynathan, R.; Shariati, M.A.; Rebezov, M.; Nile, A.; Sun, M.; Venkidasamy, B.; Xiao, J.; et al. Nano-priming as emerging seed priming technology for sustainable agriculture-recent developments and future perspectives. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, E.A. Seed priming to alleviate salinity stress in germinating seeds. J Plant Physiol 2016, 192, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparella, S.; Araujo, S.S.; Rossi, G.; Wijayasinghe, M.; Carbonera, D.; Balestrazzi, A. Seed priming: state of the art and new perspectives. Plant Cell Rep 2015, 34, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaman, M.S.; Imran, S.; Rauf, F.; Khatun, M.; Baskin, C.C.; Murata, Y.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Seed Priming with Phytohormones: An Effective Approach for the Mitigation of Abiotic Stress. Plants (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hourston, J.E.; Perez, M.; Gawthrop, F.; Richards, M.; Steinbrecher, T.; Leubner-Metzger, G. The effects of high oxygen partial pressure on vegetable Allium seeds with a short shelf-life. Planta 2020, 251, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, Y.; Konings, M.C.; Vorst, O.; van Houwelingen, A.M.; Stoopen, G.M.; Maliepaard, C.A.; Kodde, J.; Bino, R.J.; Groot, S.P.; van der Geest, A.H. Gene expression programs during Brassica oleracea seed maturation, osmopriming, and germination are indicators of progression of the germination process and the stress tolerance level. Plant Physiol 2005, 137, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, C.; Ottobrino, V.; Bassolino, L.; Toppino, L.; Rotino, G.L.; Pagano, A.; Macovei, A.; Balestrazzi, A. Molecular dynamics of pre-germinative metabolism in primed eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) seeds. Hortic Res 2020, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Zheng, M.; Khan, F.; Khaliq, A.; Fahad, S.; Peng, S.; Huang, J.; Cui, K.; Nie, L. Benefits of rice seed priming are offset permanently by prolonged storage and the storage conditions. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Tan, B.; Xu, J.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W. Priming methods affected deterioration speed of primed rice seeds by regulating reactive oxygen species accumulation, seed respiration and starch degradation. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1267103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, N.; Seo, M. Cell cycle inhibitors improve seed storability after priming treatments. J Plant Res 2019, 132, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R.; Reeves, W.; Ariizumi, T.; Steber, C. Molecular aspects of seed dormancy. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2008, 59, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.D.; Porterfield, D.M.; Li, Y.C.; Klassen, W. Increased Oxygen Bioavailability Improved Vigor and Germination of Aged Vegetable Seeds. Hortscience 2012, 47, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi, K.; Harrington, J.F. Enhancement of germination rate of aged seeds by ethylene. Plant Physiol 1971, 47, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni-Putman, S.M.; Brumos, J.; Zhao, C.; Alonso, J.M.; Stepanova, A.N. Auxin Interactions with Other Hormones in Plant Development. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilla, A.J. Auxin: Hormonal Signal Required for Seed Development and Dormancy. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza da Silva, C.; Marcos, J. Storage performance of primed bell pepper seeds with 24-Epibrassinolide. Agron J 2020, 112, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.B.; Loy, J.B. Effects of gibberellic Acid and gold light on germination, enzyme activities, and amino Acid pool size in a dwarf strain of watermelon. Plant Physiol 1978, 62, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Integration of ABA, GA, and light signaling in seed germination through the regulation of ABI5. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1000803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.Q.; Ye, T.T.; Huang, X.; Wu, H.; Ma, T.X.; Pritchard, H.W.; Wang, X.F.; Xue, H. Glutathionylation of a glycolytic enzyme promotes cell death and vigor loss during aging of elm seeds. Plant Physiol 2024, 195, 2596–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T, V.N.; S, R.; R, L.R. Evaluation of diverse soybean genotypes for seed longevity and its association with seed coat colour. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, F.R.; Valdez, R.; Lee, J.S.; Sta Cruz, P.C. Seed longevity phenotyping: recommendations on research methodology. J Exp Bot 2019, 70, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitink, J.; Leprince, O. A Seed Storage Protocol to Determine Longevity. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2830, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenollosa, E.; Jene, L.; Munne-Bosch, S. A rapid and sensitive method to assess seed longevity through accelerated aging in an invasive plant species. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, P.; Pramitha, L.; Aggarwal, P.R.; Rana, S.; Vetriventhan, M.; Muthamilarasan, M. Biotechnological interventions for improving the seed longevity in cereal crops: progress and prospects. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2023, 43, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Solanki, M.K.; Wang, Z.; Solanki, A.C.; Singh, V.K.; Divvela, P.K. Revealing the seed microbiome: Navigating sequencing tools, microbial assembly, and functions to amplify plant fitness. Microbiol Res 2024, 279, 127549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moravcova, L.; Carta, A.; Pysek, P.; Skalova, H.; Gioria, M. Long-term seed burial reveals differences in the seed-banking strategies of naturalized and invasive alien herbs. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Locus | Gene | Effect | Pathway | References (PubMed ID) |

| AT4G13250 | NYC1 | enhance | Chlorophyll degradation | 22751379 |

| AT3G48190 | ATM | decrease | DNA repair | 27503884 |

| AT5G40820 | ATR | decrease | DNA repair | 27503884 |

| AT3G05210 | ERCC1 | enhance | DNA repair | 35858436 |

| AT1G16970 | KU70 | enhance | DNA repair | 35858436 |

| AT5G57160 | LIG4 | enhance | DNA repair | 20584150 |

| AT1G66730 | LIG6 | enhance | DNA repair | 20584150 |

| AT1G25580 | SOG1 | decrease | DNA repair | 35858436 |

| AT1G21710 | OGG1 | enhance | DNA repair | 22473985 |

| AT2G31320 | PARP1 | enhance | DNA repair | 35858436 |

| AT5G22470 | PARP3 | enhance | DNA repair | 24533577 |

| AT1G14410 | WHY1 | enhance | DNA repair | 37351567 |

| AT2G02740 | WHY3 | enhance | DNA repair | 37351567 |

| AT5G64520 | XRCC2 | enhance | DNA repair | 35858436 |

| AT1G34790 | TT1 | enhance | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 10677433 |

| AT5G48100 | TT10 | enhance | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 10677433 |

| AT5G42800 | TT3 | enhance | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 10677433 |

| AT3G55120 | TT5 | enhance | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 10677433 |

| AT5G07990 | TT7 | enhance | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 10677433 |

| AT4G09820 | TT8 | enhance | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 10677433 |

| AT3G28430 | TT9 | enhance | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 10677433 |

| AT3G24650 | ABI3 | enhance | Hormone, ABA | 12231895 |

| AT3G18490 | ASPG1 | enhance | Hormone, ABA | 29648652 |

| AT5G45830 | DOG1 | enhance | Hormone, ABA | 17065317 |

| AT2G36610 | ATHB22 | enhance | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT5G65410 | ATHB25 | enhance | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT1G14440 | ATHB31 | enhance | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT1G80340 | GA3OX2 | enhance | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT2G01570 | RGA1 | decrease | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT1G14920 | RGA2 | decrease | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT1G66350 | RGL1 | decrease | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT3G03450 | RGL2 | decrease | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT5G17490 | RGL3 | decrease | Hormone, GA | 24335333 |

| AT1G09570 | PHYA | decrease | Light | 27227784 |

| AT2G18790 | PHYB | decrease | Light | 27227784 |

| AT2G45970 | CYP86A8 | enhance | Lipid biosynthesis | 32519347 |

| AT3G47860 | AtCHL | enhance | Lipid peroxidation | 23837879 |

| AT5G58070 | AtTIL | enhance | Lipid peroxidation | 23837879 |

| AT1G55020 | LOX1 | decrease | Lipid peroxidation | 28371855 |

| AT1G28440 | AtHSL1 | enhance | LRR-RLK | 35763091 |

| AT2G27500 | BG14 | enhance | Metabolism Carbohydrate | 36625794 |

| AT2G47180 | GOLS1 | enhance | Metabolism Galactose | 26993241 |

| AT1G56600 | GOLS2 | enhance | Metabolism Galactose | 26993241 |

| AT1G30370 | AtDLAH | enhance | Metabolism Lipid | 21856645 |

| AT2G19900 | NADP-ME | enhance | Metabolism Malate | 29744896 |

| AT4G15940 | AtFAHD1a | decrease | Metabolism Oxoacid | 33804275 |

| AT4G02770 | PSAD1 | enhance | PHOTOSYSTEM | 32519347 |

| AT1G62710 | β-VPE | enhance | Protein catabolism | 30782971 |

| AT2G26130 | RSL1 | enhance | Protein degradation | 24388521 |

| AT5G45360 | SKIP31 | enhance | Protein degradation | 37462265 |

| AT5G53000 | TAP46 | enhance | Protein dephosphorylation | 25399018 |

| AT3G25230 | ROF1 | enhance | Protein isomerization | 22268595 |

| AT5G48570 | ROF2 | enhance | Protein isomerization | 22268595 |

| AT3G48330 | PIMT1 | enhance | Protein repair | 19011119 |

| AT3G57520 | AtSIP2 | decrease | Raffinose catabolism | 34553917 |

| AT4G02750 | SSTPR | enhance | RNA modification | 32519347 |

| AT1G19570 | DHAR1 | enhance | ROS detoxification | 32519347 |

| AT1G05250 | PRX2 | enhance | ROS detoxification | 31600827 |

| AT2G41480 | PRX25 | enhance | ROS detoxification | 31600827 |

| AT5G64120 | PRX71 | enhance | ROS detoxification | 31600827 |

| AT5G47910 | RBOHD | decrease | ROS production | 32519347 |

| AT1G19230 | RBOHE | decrease | ROS production | 32519347 |

| AT1G64060 | RBOHF | decrease | ROS production | 32519347 |

| AT3G17520 | LEA | enhance | Seed development | 32519347 |

| AT5G44120 | CRUA | enhance | Seed storage protein | 26184996 |

| AT1G03880 | CRUB | enhance | Seed storage protein | 26184996 |

| AT4G28520 | CRUC | enhance | Seed storage protein | 26184996 |

| AT4G36920 | AtAP2 | enhance | TF AP2/EREBP | 10677433 |

| AT5G53210 | SPCH1 | enhance | TF bHLH | 32519347 |

| AT2G34140 | CDF4 | enhance | TF DOF | 27227784 |

| AT1G29160 | COG1 | enhance | TF DOF | 31600827 |

| AT4G00940 | DOF4.1 | decrease | TF DOF | 35845633 |

| AT5G42630 | ATS | enhance | TF G2-LIKE | 10677433 |

| AT1G79840 | GL2 | enhance | TF HB | 10677433 |

| AT1G62990 | KNAT7 | decrease | TF HB | 32519347 |

| AT5G54070 | AtHSFA9 | enhance | TF HSF | 32683703 |

| AT5G15800 | AGL2 | decrease | TF MADS | 32519347 |

| AT1G18710 | MYB47 | enhance | TF MYB | 32519347 |

| AT1G21970 | LEC1 | enhance | TF NF-YB | 19754639 |

| AT2G38470 | WRKY33 | enhance | TF WRKY | 26410298 |

| AT4G32770 | VTE1 | enhance | Tocopherol biosynthesis | 15155886 |

| AT2G18950 | VTE2 | enhance | Tocopherol biosynthesis | 15155886 |

| AT1G73190 | TIP3.1 | enhance | Transmembrane transport | 26019256 |

| AT1G17810 | TIP3.2 | enhance | Transmembrane transport | 26019256 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).