1. Introduction

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report Six (AR6) indicated that human practices through releasing radiative active greenhouse gases have evidently triggered global warming. Historical records show an increase in global surface temperature by 1.1

oC since 1950 [

1]. According to the same source, several changes in extremes are a direct result of increased radiative forcing of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere both globally and, to some extent county-wide. The global warming is associated with changes in large-scale hydrological cyclic events, such as an increase in atmospheric water vapour, shifting rainfall patterns, changes in rainfall intensity and seasonal to annual variations [

2]. A literature review indicated that the increasing of temperature increases the intensity of evaporation and rate of falling of condensed water vapor, cause changes in the weather patterns that characterize climate of specific area [

3]. Moreover, the water holding capacity of air parcel also increases with every 1

oC rise in ambient air temperature that would have adverse impact on hydrological process [

4]. As a result, the water gripping capability of the air parcel increases, leading to changes in vertical stability and meridional temperature gradients [

5]. Thus, the changing climate influences on climate dynamics of onset, secession, spatio-temporal distribution and amounts [

6] [

7]. Potential future changes in rainfall and temperature are likely to increase, especially in East African countries, and are more likely to warm by the end of the century according to different scenarios compared to the reference period [

8]. In Ethiopia, rapidly increasing temperature has projected to be warmer at the end of a century [

9].

According to United Nation Development Program (UNDP), the mean yearly temperature has increased via 1.3

oC between 1960 and 2006, with an average rate of 0.28

oC per decade [

10]. At a station level, mean annual temperature has increased at a rate of 0.81

oC to 1.68

oC, indicating greater than the rate of change found at national level [

11]. Other researchers emphasized that annual minimum and maximum temperature significantly increased at stations level in the period of 1993-2022 [

12]. The strong inter-annual and inter-decadal variability in Ethiopia’s rainfall and its linkages with atmospheric drivers makes it difficult to detect long-term trends [

13]. However, station-level studies have shown an increasing trend at some weather stations and a decreasing trend at other stations. For example, rainfall from June to September has shown a decreasing trend at some weather stations and an increasing trend at other stations with high interannual variability. [

14]. Other scholars also noted that the annual, spring and summer rainfall significantly increased while autumn and winter rainfall revealed decreasing trend with varying magnitude [

12].

The consequence of climate change is more pronounced in developing nations due to highly reliance on rain-fed agriculture, and have low adaptive capacity of a societies [

15]. The situation is more severe in Sub-Saharan countries like Ethiopia, due to its highly reliance on rain-fed agriculture practiced by smallholder farming systems [

16]. Smallholder farming is the primary agricultural activity, providing 84% of the country’s livelihoods [

17]. Studies indicated that rainfall based crop cultivation is adversely affected by climate change and its variability causing food insecurity [

18]. Ethiopia has a wide range of agro-ecological zones ranging from higher altitude greater than 4550 meter above mean sea level to lower altitude to 160 meter below mean sea level [

19]. The country’s location close to the equator provides bimodal rainfall types that periodically circulate [

20]. The first period occurs throughout spring season spanning from February to May, while the second occurs during the summer season spanning from June to September bringing longer rainy season [

21]. Therefore, rain-fed agriculture dominates many farming activities in the country, and is well kwon for high crop diversity [

22].

According to the Central Statistical Authority (CSA) of Ethiopia, the numerous types of crops farmed by smallholders across the country include cereals, tubers, cash crops, and oil crops. Among roots and tuber crops, sweet potato and taro are important crop served as stample or subsistence food by millions of people accros a country. They provide a substancial part of the country’s food supply and are also an important source of food security for rapidly growing population [

23]. They are grown throughout the world, however, particularly grown tropical areas, with an altitude of 1700 to 2700 meter above mean sea level [

24]. Sweet potato yield is Early maturing tuber crop, can be harvested three to four months after planting, providing food security across many Sub-Saharan African countries. Temperature and amount of sunny days have a significant impact on sweet potato yields. If temperatures are low, the growing season must be extended to six to seven months, and if there are many overcast days, production would be reduced with low root quality [

24]. On the other hand, taro can grow in areas above mean sea level of 1800 meter [

25]. These crops are more prized, because they are grown under different growing seasons, warm and humid climate of diversified agro-ecology [

26]. Moreover, they are an adaptable crop that produces large amounts of food per unit area and per unit time, giving it an advantage over other staple foods [

27].

Despite the vital contribution to food security, yield of tuber crops remained below the global average leading to poor yield at farm level. Studies indicated that it is significantly affected by both biotic and abiotic including lack of adaptable cultivars, low availability of improved seed varieties, inadequate of irrigation, weak attitude of people toward tuber crops and inefficient means of technology transfer [

28]. On the other hand, tuber crops are highly threaten by extreme climatic conditions derived by ongoing global warming [

29]. Other authors explained that tuber crop production is significantly constrained by climatic stress [

30]. As a result, the average yield produced by peasants are far lower than the global average in Ethiopia [

31]. This is since extreme weather conditions, such as climate change and fluctuation, are detrimental to most crops performance and have an impact on the predicted quantity of agricultural output [

32]. While there is no way to totally eliminate such devastating hazard, it would be much better if decision makers and farmers have sufficient information about the future, so that they can plan accordingly [

33]. Examining the spatial and temporal dynamics of climate variables and their relationships with crop production and productivity is essential to recommend appropriate adaptation measures at farm-level and improve productivity [

34]. Moreover, sharing early information about predicted crop production could help to reduce the likelihood of food insecurity.

In this regard, this study was aimed to investigate spatio-temporal climatic trends and variability, to analysis the relationship between climatic variables with tuber crop yields such as sweet potato and taro harvests, and to evaluate the predictive potential of three machine learning models. Three machine learning models are used to identify the best model in the future for crop yield prediction, named as a Regression, XGBRegression and Random Forest Regression. Modified Mann-Kendal (MMK) trend test and coefficient of variation were implemented to analysis the trend and variability. Seaborne bivariate kernel density estimate (KDE) were used to ascertain the relationship between tuber crop yields (sweet potato and taro) and climatic variables (rainfall, maximum and minimum temperature).

4. Discussion

The apparent temporal fluctuation in rainfall and temperature has far-reaching implications for smallholder farming system. Adequate and timely rainfall during agricultural/cropping seasons is crucial to farming activities. However, unpredictable rainfall triggered by fluctuation, erratic nature and inconsistency during the growing season, rain-fed smallholder farmers suffer from food insecurity [

19]. Along with insufficient soil moisture to sustain crop farming as a result of evaporation and transpiration due to increased temperature, reduces agricultural productivity and production [

58]. During the study period, rising temperatures may have had a substantial impact on smallholder farmer’s farming practices. It would exacerbate the occurrence of drought, limiting soil moisture availability and crop-land productivity, leading to crop failures [

59]. According to the evidence shown above, agricultural production is reduced by rainfall and temperature variability, which has an impact on agricultural sector, which significant contributors to food security and employments across a country. Therefore, climate variability has a potential implication on agriculture because it is very susceptible to climate change and variability [

60].

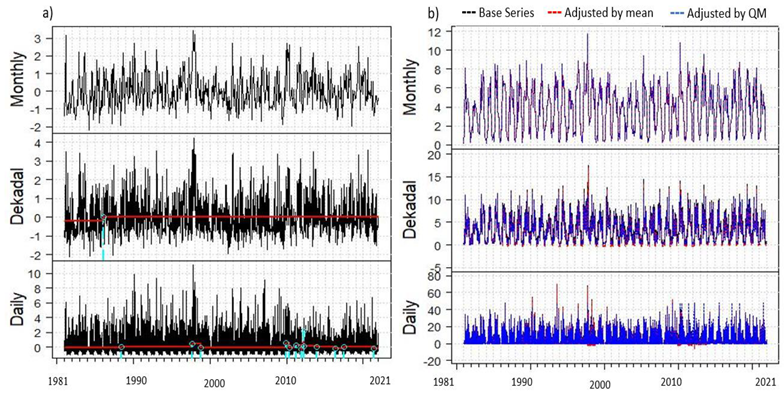

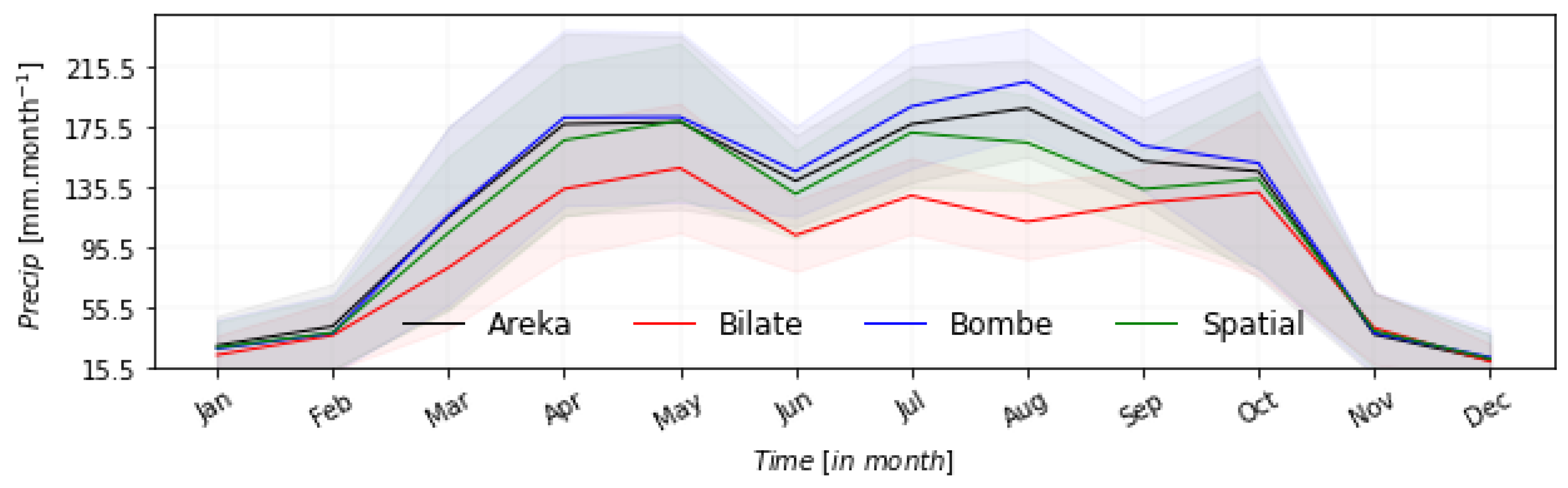

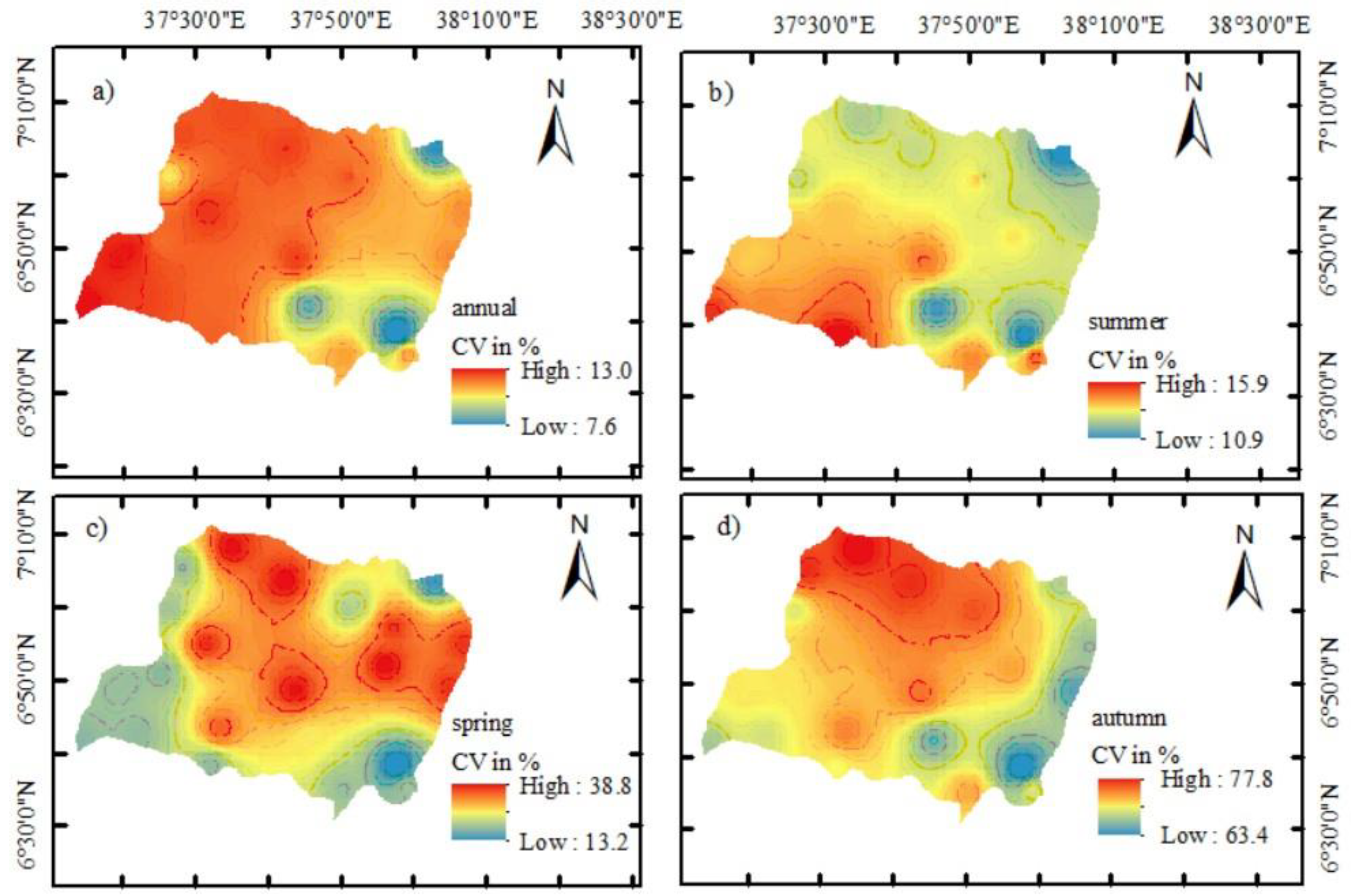

The rainfall analysis showed bi-modal characteristic with spatial-temporal variation across meteorological stations (

Figure 3). The coefficient of variation indicated that June-September rainfall experienced low variability. While spring and autumn rainfall experienced moderate and high variability, contributing 35.7% and 16.5% to the total annual rainfall, respectively, with associated risks to rain-fed crop cultivation (

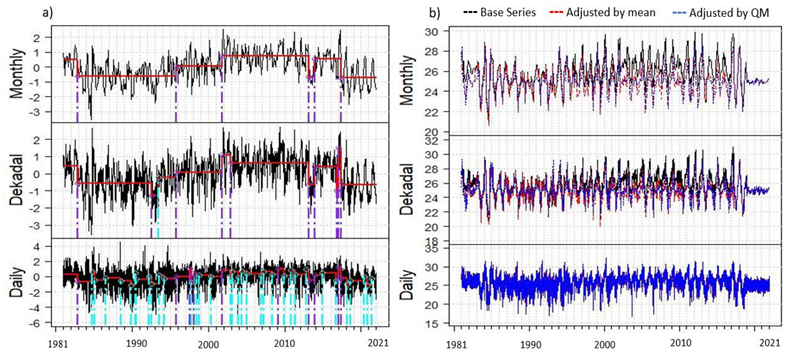

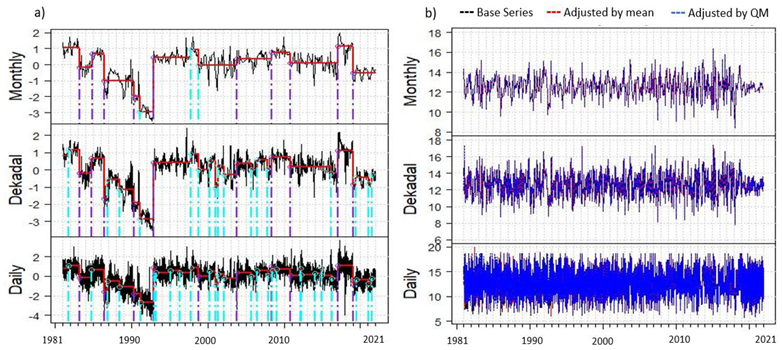

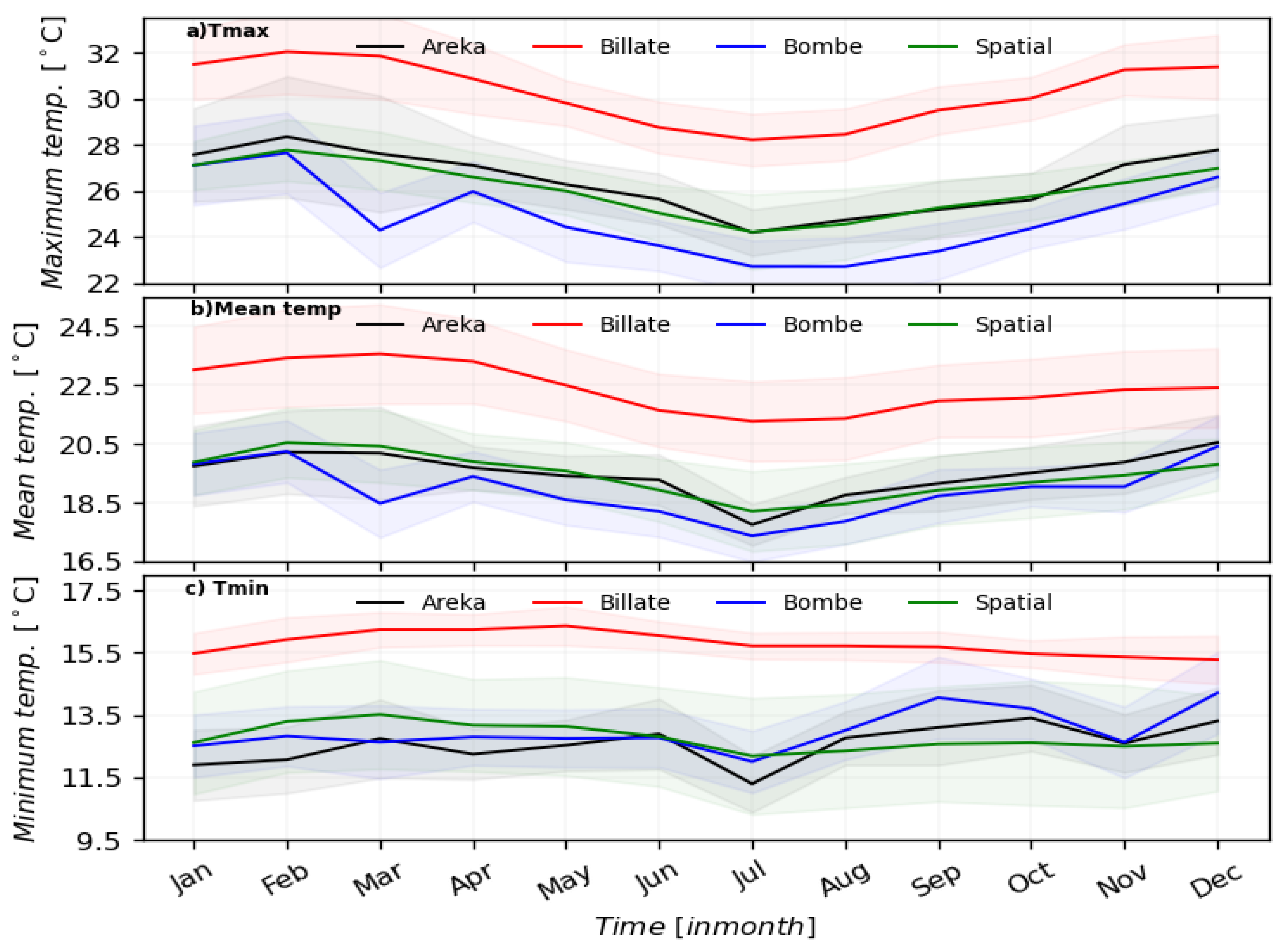

Table 2). Spatially averaged annual, spring and autumn rainfall increased at a rate of 0.275 mm/year, 0.32 mm/year and 1.67 mm/year. Whereas June-September rainfall has significantly decreased at a rate of 0.455 mm/year during crop growing period. Maximum and minimum temperature indicated significant increasing trend at a rate of 0.053

oC/year and 0.016

oC/year (

Table 3). The results of this study are consistence with those of earlier researchers. For example, [

12] has shown that summer rainfall tends to decline while autumn and winter rainfall tend to increase. Previous studies in southern Ethiopia found inter-annual fluctuations in temperature and rainfall [

53]. A comparable study in the Wolaita zone revealed a considerable increase in temperature and a decrease in rainfall [

61]. Other researchers also discovered that rainfall analysis showed significant station-to-station variability (Habte et al., 2023). The inter-seasonal and yearly rainfall variations at meteorological stations exhibited a shifting pattern that drive up and down, with the changes affecting crop output and productivity in diverse way [

62].

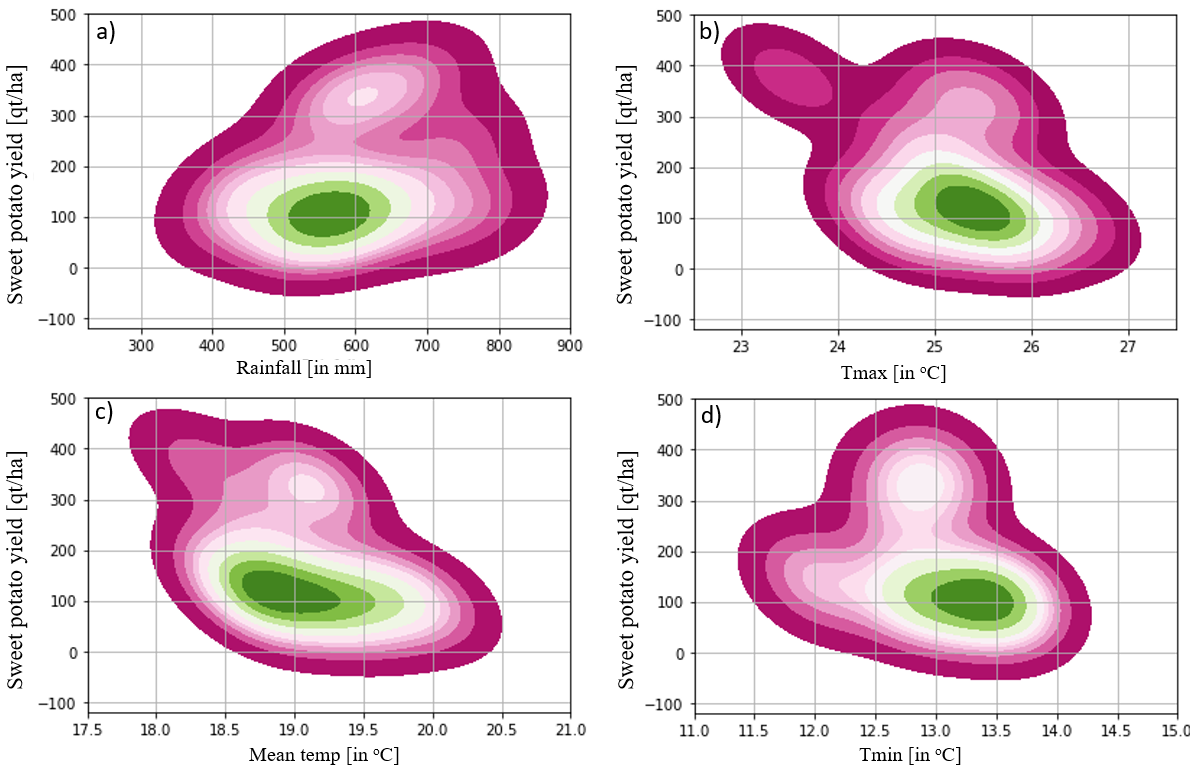

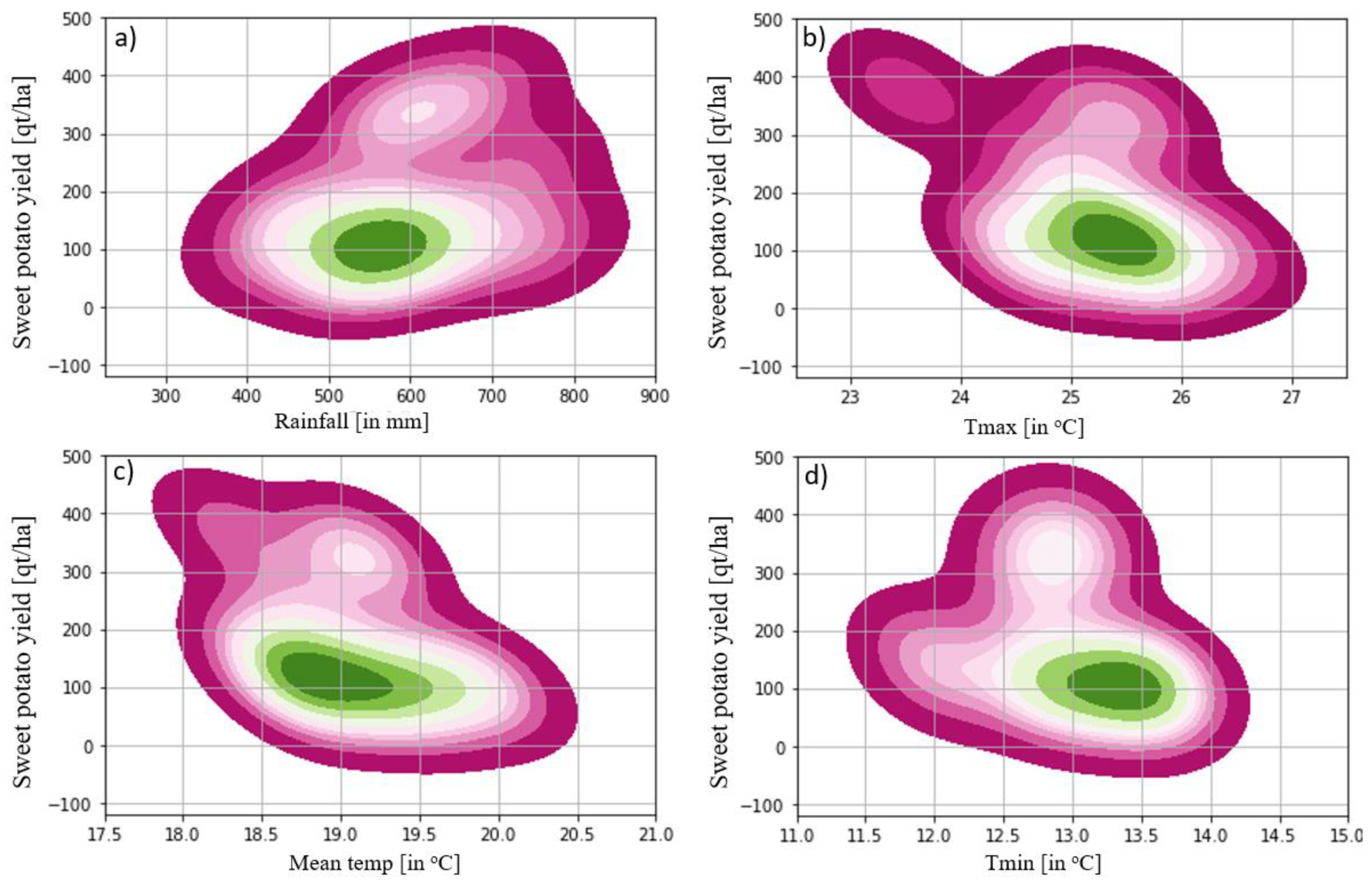

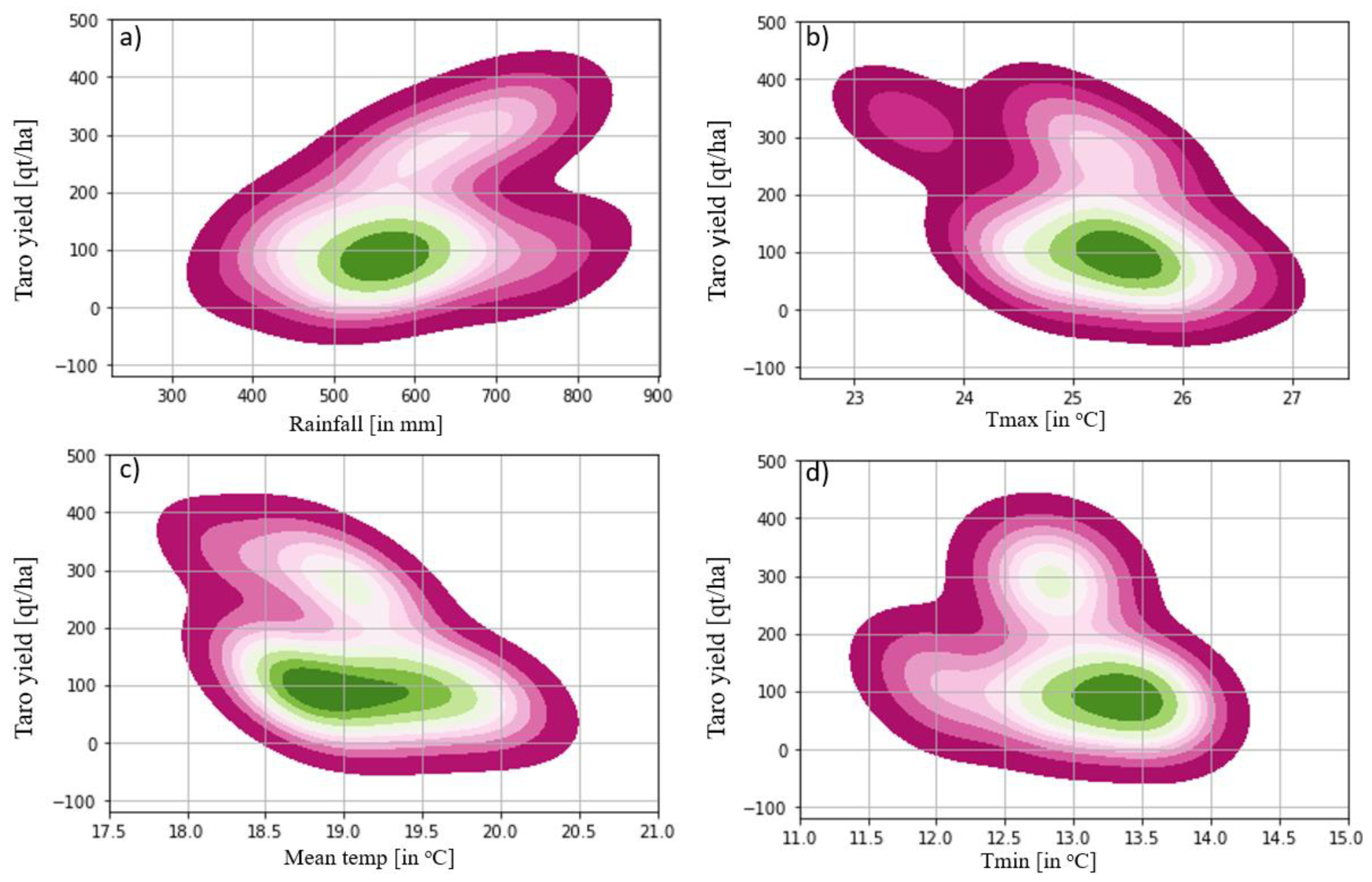

The environmental response of certain crops relies on the severity of particular weather events, the cultivated species, and the crop’s phonological conditions [

63]. Crop water requirements vary from crop to crop, growing season, and specific region [

64]. According to the finding of this study, a reasonable tuber crop yield was harvested with cumulative rainfall ranging from 450.0 to 650.0 mm during the growing season, with harvested yield amount of 150-200 qt/ha of land. However, this is only achieved at optimum crop water requirement level. For example, the yield of sweet potato and taro was decreasing below 450.0 mm and above 750.0 mm, respectively (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), indicating positive relationship. According to KDE, sweet potato and taro yields were decreased as temperature increased, demonstrating a negative association (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Crop productivity can be affected by above and below optimum temperatures, which result from reduced photosynthesis. Research finding revealed that above or below the optimum temperature has an impact on the performance of the photosynthetic process, resulting in crop failure [

33]. According to this finding, the highest density distribution of sweet potato and taro were harvested when the daytime and nighttime temperatures were around 25.0

oC and 13.5

oC, respectively. As daytime and nighttime temperature dip below 23.0

oC and increase above 26.0

oC, and nighttime temperatures decline below 11.5

oC and rise above 14.0

oC, sweet potato and taro yields decrease, and harvesting is utterly unexpected (

Figure 6b-c and

Figure 7b-c). In general, the harvested sweet potato and taro were maximum at growing season daytime and nighttime temperatures ranging from 24.5-25.5

oC and 12.5-13.5

oC, respectively, with a mean temperature value of 18.0-19.5

oC (

Figure 6b-d and

Figure 7b-d). The findings correspond with similar work, indicating that as temperature increase, root crop yield decreased, demonstrating a negative association [

65]. Another author also suggested that the optimum temperature necessary for the growth and development for root crop was ranged from 19.9

oC to 21.0

oC [

66]. The findings of this study revealed that a daytime and nighttime temperature exceed 26.0

oC and go below 14.0

oC, with a mean value exceeding 19.5

oC, have a detrimental impact on root crop growth and development.

The model performance results showed that Random Forest regression is the best model to use in the implementation of an early crop yield prediction, and explaining a high proportion of the variance in sweet potato and taro yield variability. It accounted 79.70% and 77.93% of sweet potato and taro yield variability by combined effect of rainfall and temperature, respectively (

Table 5). Other authors have also suggested that RF regression has a high predictive potential and utilized as a machine learning techniques for crop yield prediction [

67]. Similar study revealed that crop yield prediction by RF regression produced par results than MLR. For example, RF algorithms attained highest R

2 value above 75% [

68], and the predictive potential of RF algorithms explained 87% of yield variability [

69]. Moreover, [

70] noted that the RF algorithms achieved 92.3% of yield predicting.

The full impact of rising temperatures on crop photosynthesis is still being studied, particularly, given the complex interactions of water availability, rising atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration, nutrient availability, plant diseases, and increased frequency and intensity of extreme climate events, all of which feedback to alter crop photosynthesis and productivity [

71]. Crop productivity potential could be only determined if a full grasp of crop growth and development is realized. These, in turn, are influenced by climatic, edaphic, hydrological, physiological, use of technology, and managerial aspects. In this study, climate variables are the main drivers to cause year-to-year yield variations. In reality, climate variability is not the only driver to cause major changes to yield variability and trend, there are also other factors, such as radiations, water, nutrition, and pests and diseases [

72]. Furthermore, numerous other factors influence crop productivity, including cultivars, crop physiology, and crop management.

5. Conclusion

This study examined temperature and rainfall trend and variability, and explored the relationship between climate variability with rain-fed tuber crop productivity implementing machine learning algorithms. The study has also evaluated the predictive potential of machine learning approaches. The study used climatic variables of rainfall and air temperature as drivers, sweet potato and taro as reliant variables. The analyzed result of rainfall characteristics at station level showed decreasing trend at many stations during summer rainy season, while increasing trend during spring period at many weather stations. Spatially averaged rainfall showed increasing trend during spring, autumn and annually at a rate of 0.32 mm, 1.67 mm and 0.25 mm, while significantly decreasing in summer rainy season at a rate of 0.455 mm/year. Spring and autumn rainfall had moderate to high variability, 20.7% and 38.8%, respectively, posing risks to rain-fed farming, whereas summer rainfall had low variability. Spatially averaged mean, maximum and minimum temperatures showed an increasing trend at a rate of 0.032 oC, 0.053 oC and 0.16 oC 1981-2021 period, respectively. A reasonable tuber crop yield was harvested with cumulative rainfall ranging from 450.0 to 650.0 mm during the growing season, at a day and night time temperature was between 23.0-26.0 oC and 11.5-14.0 oC. When day time temperature above 26.0 oC and night time temperature below 11.5 oC, sweet potato and taro yields decrease, and harvesting is utterly unexpected. Machine learning model, such as RF regression has a good predictive potential, and explained 79.70% and 77.93% of sweet potato and taro yield variability. The study concludes that the high variability of spring rainfall and the decreasing trend of summer rainfall, combined with an increasing of temperatures, could reduce agricultural productivity, leading to food insecurity. While optimal climatic variables might boost crop yield, excessively increased/decreased rates result in declining or even complete failures. The RF regression model proved to be the best model performing algorithm allowing for optimal yield prediction, assisting farmers and decision makers in better planning crop production and management in Ethiopia. Therefore, the yield of tuber crops can be improved by supplementing the rain-fed farming system with irrigation and applying modern farming techniques and operations by farmers. Moreover, the finding suggests that the need to carefully select plant varieties tolerant to high ambient temperature conditions, which will be more prevalent in the context of climate change. There is a need to intensify adaptation measures to minimize the negative consequences of climate variability to improve the adaptive capacity of sweet potato and taro farmers.

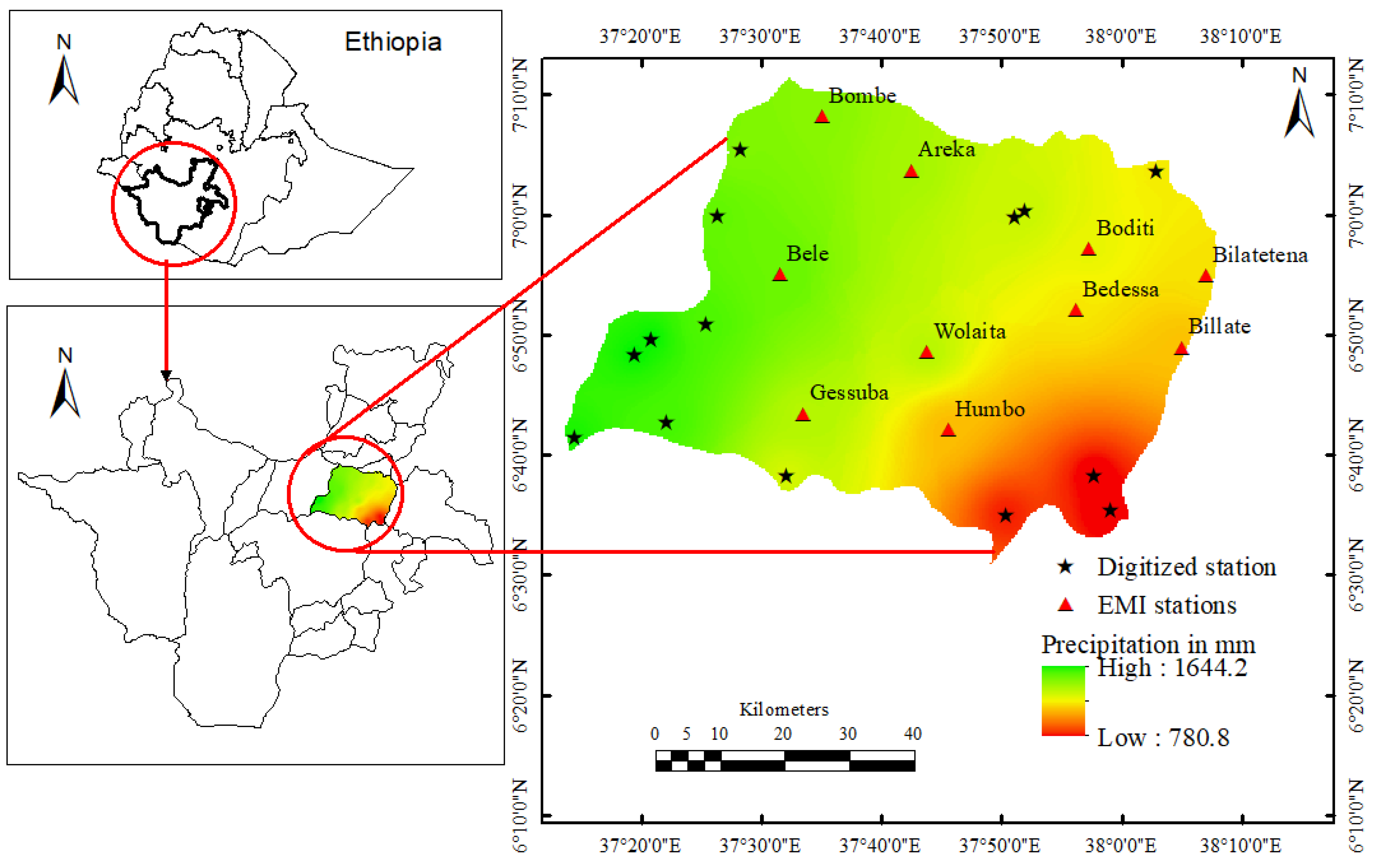

Figure 1.

Presents study area map with annual mean rainfall distribution and location of meteorological sites. The asterisks indicate digitized/virtual stations and red colored triangles represents Ethiopian Meteorological Institute (EMI) observational sites, respectively.

Figure 1.

Presents study area map with annual mean rainfall distribution and location of meteorological sites. The asterisks indicate digitized/virtual stations and red colored triangles represents Ethiopian Meteorological Institute (EMI) observational sites, respectively.

Figure 2.

Shows spatially averaged and station level monthly rainfall pattern at Bilate, Bombe and Areka stations, respectively.

Figure 2.

Shows spatially averaged and station level monthly rainfall pattern at Bilate, Bombe and Areka stations, respectively.

Figure 3.

Shows Coefficient of Variations in % for (a) annual rainfall, (b) Kiremt (summer) rainfall, (c) Belg (spring) rainfall and (d) Bega (autumn) rainfall, respectively.

Figure 3.

Shows Coefficient of Variations in % for (a) annual rainfall, (b) Kiremt (summer) rainfall, (c) Belg (spring) rainfall and (d) Bega (autumn) rainfall, respectively.

Figure 4.

Shows monthly maximum temperature (a), mean temperature (b) and minimum temperature (c) at Areka, Bilate, Bombe stations and spatially averaged over the study area.

Figure 4.

Shows monthly maximum temperature (a), mean temperature (b) and minimum temperature (c) at Areka, Bilate, Bombe stations and spatially averaged over the study area.

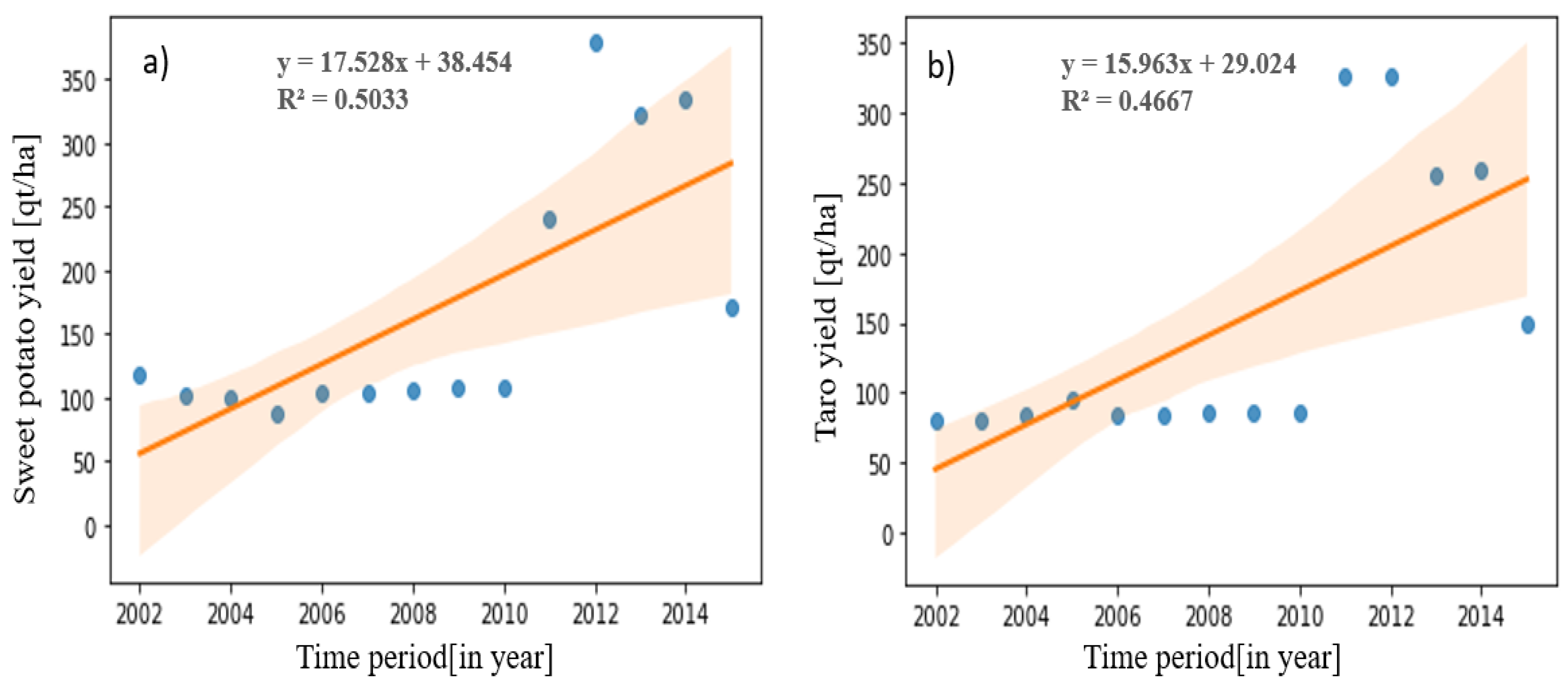

Figure 5.

Shows sweet potato (a) and taro (b) yield anomaly and trend for 2002 to 2016 period.

Figure 5.

Shows sweet potato (a) and taro (b) yield anomaly and trend for 2002 to 2016 period.

Figure 6.

Depicts Seaborne bivariate KDE between rainfall, maximum, minimum and mean temperature with sweet potato yield.

Figure 6.

Depicts Seaborne bivariate KDE between rainfall, maximum, minimum and mean temperature with sweet potato yield.

Figure 7.

Shows Seaborne bivariate KDE between rainfall, maximum, minimum and mean temperature with taro yield.

Figure 7.

Shows Seaborne bivariate KDE between rainfall, maximum, minimum and mean temperature with taro yield.

Table 1.

Present spatially averaged monthly rainfall characteristics, percent of contribution (in %), coefficient of Variation (CV in %/) , Modified Mann Kendal (MMK) trend test and Sen’s Slope (in mm) during the period of 1981 to 2021.

Table 1.

Present spatially averaged monthly rainfall characteristics, percent of contribution (in %), coefficient of Variation (CV in %/) , Modified Mann Kendal (MMK) trend test and Sen’s Slope (in mm) during the period of 1981 to 2021.

| Mon |

Contribution(%) |

CV (%) |

MK test |

Sen’s slope |

| Jan |

2.09 |

60.4 |

-0.013 |

-0.020 |

| Feb |

5.31 |

72.0 |

+ 0.18 |

+1.04 |

| Mar |

7.93 |

48.7 |

+ 0.062 |

+0.37 |

| Apr |

12.15 |

30.3 |

+ 0.068 |

+0.59 |

| May |

13.34 |

29.7 |

+ 0.066 |

+ 0.50 |

| Jun |

9.77 |

23.4 |

+ 0.090 |

+0.385 |

| Jul |

13.02 |

22.2 |

-0.035 |

-0.169 |

| Aug |

11.89 |

19.2 |

-0.018 |

-0.136 |

| Sep |

9.78 |

19.9 |

-0.175 |

-0.58 |

| Oct |

10.27 |

41.7 |

+0.11 |

+0.83 |

| Nov |

2.91 |

62.5 |

+ 0.163 |

+ 0.35 |

| Dec |

1.55 |

76.5 |

+ 0.067 |

+0.07 |

Table 2.

Show seasonal and annual rainfall characteristics, Mann-Kendal (MK) trend test, Sen’s Slope (SS), percent of contribution (% cont) and coefficient of variation 1981 to 2021 period.

Table 2.

Show seasonal and annual rainfall characteristics, Mann-Kendal (MK) trend test, Sen’s Slope (SS), percent of contribution (% cont) and coefficient of variation 1981 to 2021 period.

| |

Parameters |

Spatially averaged |

Areka |

Bedessa |

Bele |

Bilatetena |

Billate |

Boditi |

Bombe |

Gessuba |

Humbo |

Wolaita |

| Annual |

mean |

1324.8 |

1408.5 |

1218.1 |

1526.3 |

1214.3 |

1144.4 |

1275.0 |

1465.3 |

1376.8 |

1134.6 |

1372.5 |

| MMK |

0.119 |

0.0021 |

-0.1014 |

-0.001 |

-0.156 |

-0.114 |

-0.069 |

0.0443 |

-0.035 |

-0.097 |

0.027 |

| SS |

+0.275 |

0.128 |

-1.686 |

-0.035 |

-2.547 |

-2.095 |

-1.478 |

1.0482 |

-0.761 |

-0.864 |

0.615 |

| Spring |

mean |

490.7 |

236.7 |

216.0 |

270.0 |

234.2 |

228.3 |

226.1 |

243.0 |

234.7 |

209.3 |

236.4 |

| MMK |

+0.106 |

0.202 |

0.141 |

0.167 |

0.107 |

0.17 |

0.133 |

0.1897 |

0.157 |

-0.053 |

0.238 |

| SS |

0.32 |

2.16** |

1.250 |

1.945 |

0.947 |

1.382 |

1.208 |

0.05** |

1.076 |

-0.283 |

2.24** |

| %cont |

35.7 |

36.6 |

37.1 |

36.4 |

37.9 |

36.9 |

37.6 |

35.5 |

36.9 |

35.7 |

35.2 |

| Summer |

mean |

602.9 |

658.8 |

551.3 |

704.3 |

521.6 |

495.4 |

570.3 |

704.9 |

637.0 |

521.9 |

654.3 |

| MMK |

-0.043 |

-0.019 |

-0.173 |

0.024 |

-0.181 |

-0.11 |

-0.139 |

0.087 |

-0.0243 |

0.0317 |

-0.056 |

| SS |

-0.455** |

-0.248 |

-1.576 |

0.363 |

-1.284 |

0.913 |

-1.235 |

0.796 |

-0.178 |

0.2190 |

-0.762 |

| %cont |

47.8 |

46.8 |

45.3 |

46.1 |

42.9 |

43.3 |

44.7 |

48.1 |

46.3 |

46 |

47.7 |

| Autumn |

mean |

233.5 |

265.3 |

240.5 |

300.6 |

258.1 |

250.7 |

251.7 |

272.8 |

262.6 |

231.9 |

264.1 |

| MMK |

+0.197 |

0.202 |

0.141 |

0.167 |

0.1076 |

0.170 |

0.133 |

0.189 |

0.157 |

-0.053 |

0.238 |

| SS |

1.67** |

2.18** |

1.25 |

1.945 |

0.947 |

1.382 |

1.208 |

1.49** |

1.076 |

-0.28 |

2.24** |

| % cont |

16.5 |

16.8 |

17.7 |

17.7 |

19.3 |

20 |

17.7 |

16.6 |

17 |

18.4 |

17.2 |

Table 3.

Shows annual mean, Tmax and Tmin trend for 1981-2021 period.

Table 3.

Shows annual mean, Tmax and Tmin trend for 1981-2021 period.

Stations |

Tmax |

Mean |

Tmin |

| Mean |

MMK |

SS |

CV |

Mean |

MMK |

SS |

CV |

Mean |

MMK |

SS |

CV |

| Areka |

26.4 |

0.068 |

0.64 |

3.5 |

19.5 |

0.06 |

0.003 |

2.6 |

12.6 |

-0.03 |

-0.09 |

1.9 |

| Bedessa |

27 |

0.3 |

0.04** |

3.3 |

20.5 |

0.326 |

0.044** |

6.1 |

13.9 |

0.35 |

0.042** |

13.3 |

| Bele |

30.3 |

0.46 |

1.69** |

3.4 |

23.7 |

0.44 |

0.025** |

2.3 |

17.1 |

-0.02 |

-0.006 |

1.6 |

| Bilatetena |

27.7 |

0.3 |

0.033** |

3.4 |

20.4 |

0.29 |

0.038** |

5.9 |

13.1 |

0.26 |

0.037 |

12.7 |

| Billate |

30.3 |

0.23 |

0.032 |

2.9 |

22.4 |

0.302 |

0.039** |

5.6 |

14.5 |

0.26 |

0.037 |

12.8 |

| Boditi |

24.4 |

0.23 |

0.18 |

3.3 |

18.6 |

0.329 |

0.035** |

6.2 |

12.7 |

0.54 |

0.043** |

14.5 |

| Bombe |

24.8 |

0.029 |

0.001 |

1.4 |

18.5 |

-0.014 |

-0.006 |

1.1 |

12 |

0.05 |

0.001 |

1.9 |

| Gessuba |

29.2 |

0.28 |

0.017** |

2.4 |

21.8 |

0.251 |

0.025** |

3.3 |

14.4 |

0.097 |

0.017 |

8.3 |

| Humbo |

27.5 |

0.36 |

0.029** |

2.3 |

21.6 |

0.358 |

0.015** |

1.6 |

15.8 |

-0.034 |

-0.0007 |

0.9 |

| Wolaita |

25.8 |

0.23 |

0.13 |

2.6 |

19.5 |

0.173 |

0.016 |

5.1 |

13.1 |

0.031 |

0.008 |

11.9 |

| Spatial |

26.1 |

0.5 |

0.053** |

2.2 |

19.4 |

0.39 |

0.032** |

5.0 |

12.8 |

0.082 |

0.016 |

11.8 |

Table 4.

Show descriptive statistics and trend of taro and sweet potato yield, respectively.

Table 4.

Show descriptive statistics and trend of taro and sweet potato yield, respectively.

| Parameters |

MMK |

SS |

Mean |

SD |

cv |

Min |

Max |

| Taro |

0.46 |

6.069 |

188.28 |

103.5 |

55.0 |

85.8 |

378.7 |

| Sweet Potato |

0.516 |

5.36** |

166.40 |

89.9 |

54.0 |

80 |

327 |

Table 5.

Shows predictive potential of GBR, XGBR, RF and MLR models comparison.

Table 5.

Shows predictive potential of GBR, XGBR, RF and MLR models comparison.

| |

Yield |

RMSE |

R-squared |

| GradientBoosting Regression |

Taro |

172.2868 |

0.77599941896428238 |

| Sweet potato |

142.7695 |

0.769999976968095767 |

| XGBRegression |

Taro |

205.32352475 |

0.68999999999872404 |

| Sweet potato |

148.380 |

0.7499999998997617 |

| RandomForest Regression |

Taro |

127.2413 |

0.779352310866891 |

| Sweet potato |

117.208339 |

0.7970453256514087 |

| Linear Regression |

Taro |

96.555238 |

0.367658073611723 |

| Sweet potato |

82.21450 |

0.24159370708581318 |