Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

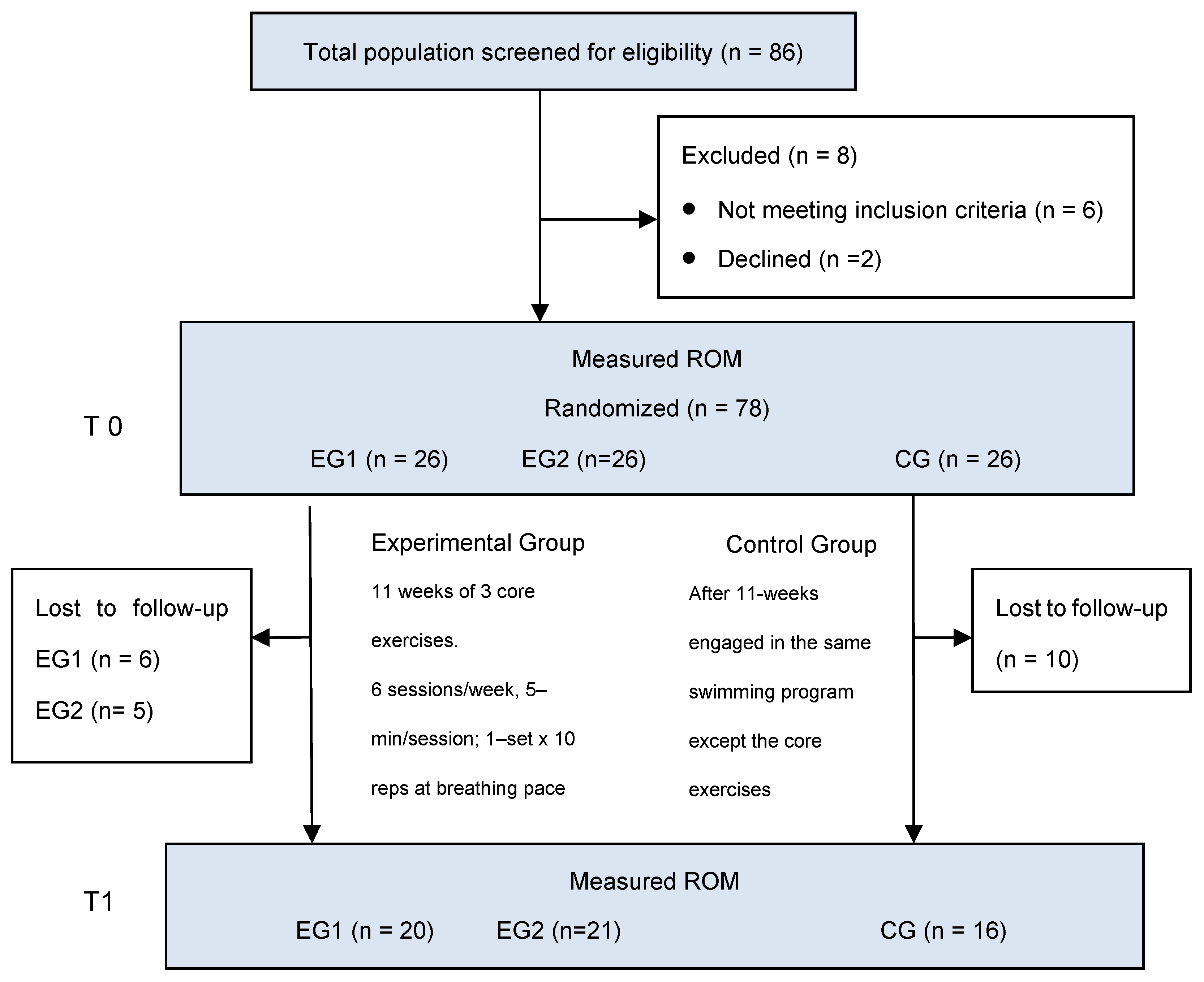

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

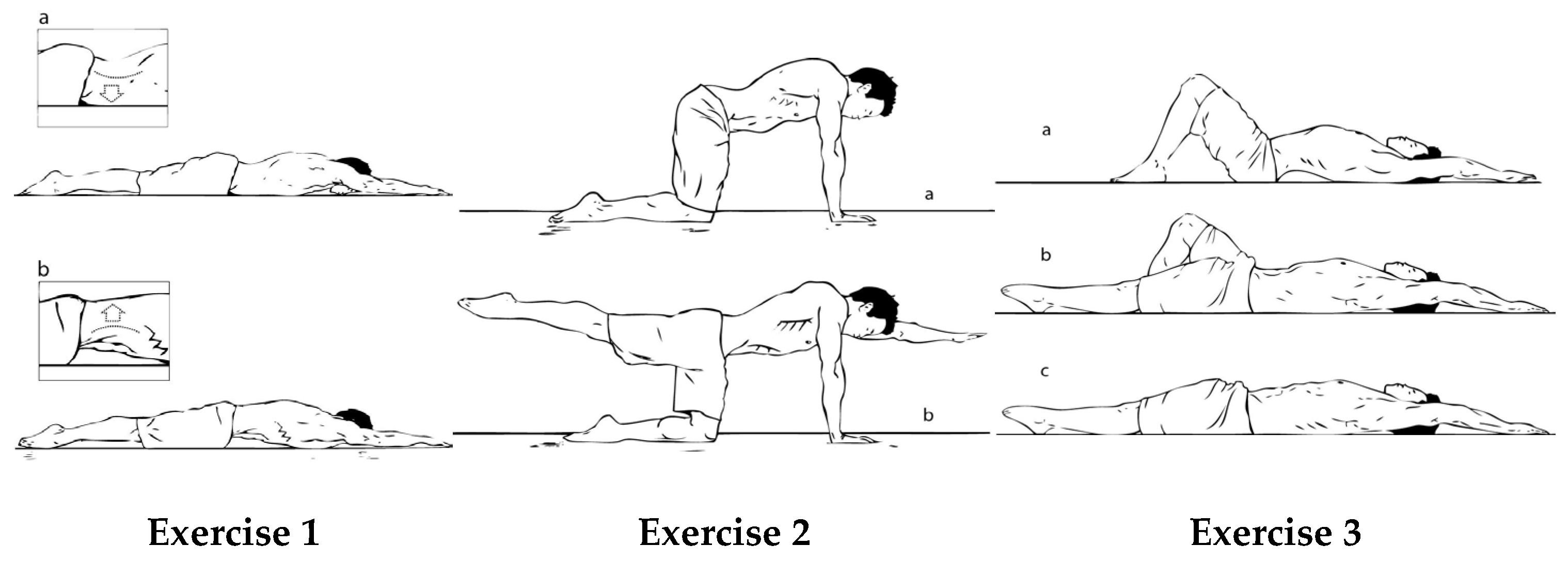

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Testing Protocol

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ha, T.H.; Saber-Sheikh, K.; Moore, A.P.; Jones, M.P. Measurement of Lumbar Spine Range of Movement and Coupled Motion Using Inertial Sensors - A Protocol Validity Study. Man Ther 2013, 18, 87–91.

- Consmüller, T.; Rohlmann, A.; Weinland, D.; Druschel, C.; Duda, G.N.; Taylor, W.R. Comparative Evaluation of a Novel Measurement Tool to Assess Lumbar Spine Posture and Range of Motion. Eur Spine J 2012, 21, 2170–2180. [CrossRef]

- Edmondston, S.J.; Song, S.; Bricknell, R. V; Davies, P.A.; Fersum, K.; Humphries, P.; Wickenden, D.; Singer, K.P. MRI Evaluation of Lumbar Spine Flexion and Extension in Asymptomatic Individuals. Man Ther 2000, 5, 158–164.

- Apti, A.; Çolak, T.K.; Akçay, B. NORMATIVE VALUES FOR CERVICAL AND LUMBAR RANGE OF MOTION IN HEALTHY YOUNG ADULTS. Journal of Turkish Spinal Surgery 2023, 34, 113–117. [CrossRef]

- Errabity, A.; Calmels, P.; Suck Han, W.; Bonnaire, R.; Pannetier, R.; Convert, R.; Molimard, J. The Effect of Low Back Pain on Spine Kinematics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical Biomechanics 2023, 108. [CrossRef]

- Leetun, D.T.; Ireland, M.L.; Willson, J.D.; Ballantyne, B.T.; Davis, I.M. Core Stability Measures as Risk Factors for Lower Extremity Injury in Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004, 36, 926–934. [CrossRef]

- Panjabi, M.M. The Stabilizing System of the Spine. Part I. Function, Dysfunction, Adaptation, and Enhancement. J Spinal Disord 1992, 5, 383–389; discussion 397.

- Mok, N.W.; Hodges, P.W. Movement of the Lumbar Spine Is Critical for Maintenance of Postural Recovery Following Support Surface Perturbation. Exp Brain Res 2013, 231, 305–313.

- Hibbs, A.E. Development and Evaluation of a Core Training Programme in Highly Trained Swimmers, 2011.

- Khiyami, A.; Nuhmani, S.; Joseph, R.; Abualait, T.S.; Muaidi, Q. Efficacy of Core Training in Swimming Performance and Neuromuscular Parameters of Young Swimmers: A Randomised Control Trial. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.-Y.; Yoon, J.-H.; Song, K.-J.; Oh, J.-K. Effect of Dry-Land Core Training on Physical Fitness and Swimming Performance in Adolescent Elite Swimmers; 2021; Vol. 50;.

- Karpiński, J.; Rejdych, W.; Brzozowska, D.; Gołaś, A.; Sadowski, W.; Swinarew, A.S.; Stachura, A.; Gupta, S.; Stanula, A. The Effects of a 6-Week Core Exercises on Swimming Performance of National Level Swimmers. PLoS One 2020, 15. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Cuenca-Fernández, F.; Sanders, R.; Arellano, R. The Determinant Factors of Undulatory Underwater Swimming Performance: A Systematic Review. J Sports Sci 2022, 40, 1243–1254. [CrossRef]

- Veiga, S.; Lorenzo, J.; Trinidad, A.; Pla, R.; Fallas-Campos, A.; de la Rubia, A. Kinematic Analysis of the Underwater Undulatory Swimming Cycle: A Systematic and Synthetic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19.

- Houel, N.; Elipot, M.; Andrée, F.; Hellard, H./ Kinematics Analysis of Undulatory Underwater Swimming during a Grab Start of National Level Swimmers. XIth International Symposium for Biomechanics & Medicine in Swimming 2010, 97–99.

- Matsuura, Y.; Matsunaga, N.; Iizuka, S.; Akuzawa, H.; Kaneoka, K. Muscle Synergy of the Underwater Undulatory Swimming in Elite Male Swimmers. Front Sports Act Living 2020, 2. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M. Simulation Analysis of the Effect of Trunk Undulation on Swimming Performance in Underwater Dolphin Kick of Human. Journal of Biomechanical Science and Engineering 2009, 4, 94–104. [CrossRef]

- Born, D.-P.; Burkhardt, D.; Buck, M.; Schwab, L.; Romann, M. Key Performance Indicators and Reference Values for Turn Performance in Elite Youth, Junior and Adult Swimmers. Sports Biomech 2024, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Connaboy, C.; Coleman, S.; Moir, G.; Sanders, R. Measures of Reliability in the Kinematics of Maximal Undulatory Underwater Swimming. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010, 42, 762–770. [CrossRef]

- Gavilan, A.; Arellano, R.; Sanders, R. UNDERWATER UNDULATORY SWIMMING: STUDY OF FREQUENCY, AMPLITUDE AND PHASE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE “BODY WAVE.” Revista Portuguesa de Ciencias do Desporto 2006, 6, 35–37.

- Houel, N.; Elipot, M.; Andrée, F.; Hellard, H./ Kinematics Analysis of Undulatory Underwater Swimming during a Grab Start of National Level Swimmers. XIth International Symposium for Biomechanics & Medicine in Swimming 2010, 97–99.

- Marshall, P.W.M.; Desai, I.; Robbins, D.W. Core Stability Exercises in Individuals With and Without Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain. J Strength Cond Res 2011, 25, 3404–3411. [CrossRef]

- Willardson, J.M. Core Stability Training: Applications to Sports Conditioning Programs. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association 2007, 21, 979–985. [CrossRef]

- Warneke, K.; Lohmann, L.H.; Wilke, J. Effects of Stretching or Strengthening Exercise on Spinal and Lumbopelvic Posture: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med Open 2024, 10.

- Zhou, Z.; Morouço, P.G.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Chen, C.; Cui, W.; Wu, R.; Wang, J. Effects of Two Warm-up Protocols on Isokinetic Knee Strength, Jumping Ability and Sprint Swimming Performance in Competitive Swimmers. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Loupos, D.; Tsalis, G.; Manou, B. Effects of Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) on Swimmers Leg Mobility and Performance. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2017, 17, 663–668. [CrossRef]

- Emery, K.; De Serres, S.J.; McMillan, A.; Côté, J.N. The Effects of a Pilates Training Program on Arm-Trunk Posture and Movement. Clinical Biomechanics 2010, 25, 124–130.

- Desai, I.; Marshall, P.W.M. Acute Effect of Labile Surfaces during Core Stability Exercises in People with and without Low Back Pain. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2010. [CrossRef]

- Skundric, G.; Vukicevic, V.; Lukic, N. Effects of Core Stability Exercises, Lumbar Lordosis and Low-Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Journal of Anthropology of Sport and Physical Education 2021, 5, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Lepage, L.; Altman, D.G.; Schulz, K.F.; Moher, D.; Egger, M.; Davidoff, F.; Elbourne, D.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Lang, T. The Revised CONSORT Statement for Reporting Randomized Trials: Explanation and Elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001.

- World Medical Association; Association, W.M. Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [CrossRef]

- Madson, T.J.; Youdas, J.W.; Suman, V.J. Reproducibility of Lumbar Spine Range of Motion Measurements Using the Back Range of Motion Device. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999, 29, 470–477. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ, 1988;

- Behm, D.G.; Chaouachi, A. A Review of the Acute Effects of Static and Dynamic Stretching on Performance. Eur J Appl Physiol 2011.

- Nieto-Guisado, A.; Solana-Tramunt, M.; Marco-Ahulló, A.; Sevilla-Sánchez, M.; Cabrejas, C.; Campos-Rius, J.; Morales, J. The Mediating Role of Vision in the Relationship between Proprioception and Postural Control in Older Adults, as Compared to Teenagers and Younger and Middle-Aged Adults. Healthcare (Switzerland) 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Portas, C.M.; Rees, G.; Howseman, A.M.; Josephs, O.; Turner, R.; Frith, C.D. A Specific Role for the Thalamus in Mediating the Interaction of Attention and Arousal in Humans. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 8979–8989.

- Johnson, E.O.; Babis, G.C.; Soultanis, K.C.; Soucacos, P.N. Functional Neuroanatomy of Proprioception. J Surg Orthop Adv 2008, 17, 159–164.

- Proske, U. What Is the Role of Muscle Receptors in Proprioception? Muscle Nerve 2005, 31, 780–787.

- Short, S.E.; Tenute, A.; Feltz, D.L. Imagery Use in Sport: Mediational Effects for Efficacy. J Sports Sci 2005, 23, 951–960.

- Mizuguchi, N.; Nakata, H.; Uchida, Y.; Kanosue, K. Motor Imagery and Sport Performance; 2012; Vol. 1;.

- Hiemstra, L.A.; Lo, I.K.; Fowler, P.J. Effect of Fatigue on Knee Proprioception: Implications for Dynamic Stabilization. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2001, 31, 598–605.

- Myers, J.B.; Guskiewicz, K.M.; Schneider, R. a.; Prentice, W.E. Proprioception and Neuromuscular Control of the Shoulder after Muscle Fatigue. J Athl Train 1999, 34, 362–367.

- Brown, J.P.; Bowyer, G.W. Effects of Fatigue on Ankle Stability and Proprioception in University Sportspeople. Br J Sports Med 2002, 36, 310. [CrossRef]

- Gear, W.S. Effect of Different Levels of Localized Muscle Fatigue on Knee Position Sense. J Sports Sci Med 2011, 10, 725–730.

- Cabrejas, C.; Solana-Tramunt, M.; Morales, J.; Campos-Rius, J.; Ortegón, A.; Nieto-Guisado, A.; Carballeira, E. The Effect of Eight-Week Functional Core Training on Core Stability in Young Rhythmic Gymnasts: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Kurt, S.; İbiş, S.; Burak Aktuğ, Z.; Altundağ, E. The Effect of Core Training on Swimmers’ Functional Movement Screen Scores and Sport Performances. 2023.

- Lederman, E. The Myth of Core Stability. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2010, 14, 84–98. [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, A.E. Development and Evaluation of a Core Training Programme in Highly Trained Swimmers, 2011.

- Grooms, D.R.; Grindstaff, T.L.; Croy, T.; Hart, J.M.; Saliba, S.A. Clinimetric Analysis of Pressure Biofeedback and Transversus Abdominis Function in Individuals With Stabilization Classification Low Back Pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2013. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, P.; Kaigle Holm, A.; Holm, S.; Ekström, L.; Cresswell, A.; Hansson, T.; Thorstensson, A. Intervertebral Stiffness of the Spine Is Increased by Evoked Contraction of Transversus Abdominis and the Diaphragm: In Vivo Porcine Studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003, 28, 2594–2601.

- Breathing Pattern 2014 Ijspt-02-028.

- Talasz, H.; Kremser, C.; Talasz, H.J.; Kofler, M.; Rudisch, A. Breathing, (S)Training and the Pelvic Floor—A Basic Concept. Healthcare (Switzerland) 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zbieta Szczygiel, E._; Edrzej Blaut, J.; Zielonka-Pycka, K.; Tomaszewski, K.; Golec, J.; Czechowska, D.; Maslo, A.; Golec, E. The Impact of Deep Muscle Training on the Quality of Posture and Breathing;

- Okada, T.; Huxel, K.C.; Nesser, T.W. Relationship between Core Stability, Functional Movement, and Performance. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association 2011, 25, 252–261.

- Hibbs, A.E.; Thompson, K.G.; French, D.; Wrigley, A.; Spears, I. Optimizing Performance by Improving Core Stability and Core Strength. Sports Medicine 2008, 38, 995–1008. [CrossRef]

- Pearcy, M.; Portek, I.; Shepherd, J. Three-Dimensional x-Ray Analysis of Normal Movement in the Lumbar Spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1984, 9, 294–297.

- Perriman, D.M.; Scarvell, J.M.; Hughes, A.R.; Ashman, B.; Lueck, C.J.; Smith, P.N. Validation of the Flexible Electrogoniometer for Measuring Thoracic Kyphosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010, 35, E633-40.

- Luomajoki, H.; Kool, J.; de Bruin, E.D.; Airaksinen, O. Reliability of Movement Control Tests in the Lumbar Spine. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007, 8, 90.

- May, S.; Littlewood, C.; Bishop, A. Reliability of Procedures Used in the Physical Examination of Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Aust J Physiother 2006, 52, 91–102.

|

| Age (yr), mean (SD) Males Females |

20.2 (4.2) 20.7 (3.3) |

| Gender, n female (%) | 23 (40.3%) |

| Body mass Kg, mean (SD) | 69.7 (10.3) |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 177.8 (7.5) |

| Professional swimming experience (years) mean (SD) Level, n (%) Olympic International National Main swimming style n (%) Freestyle Breastroke Butterfly Backstroke Individual Medley Main competition distance n (%) 50-100 200-400 800-1500 |

8.7 (4.4) 33 (57.8%) 13 (22.8%) 11 (19.2%) 18 (31.5%) 14 (24.5%) 9 (15.7%) 8 (14.0%) 8 (14.0%) 20 (35.1%) 31 (54.4%) 6 (10.5%) |

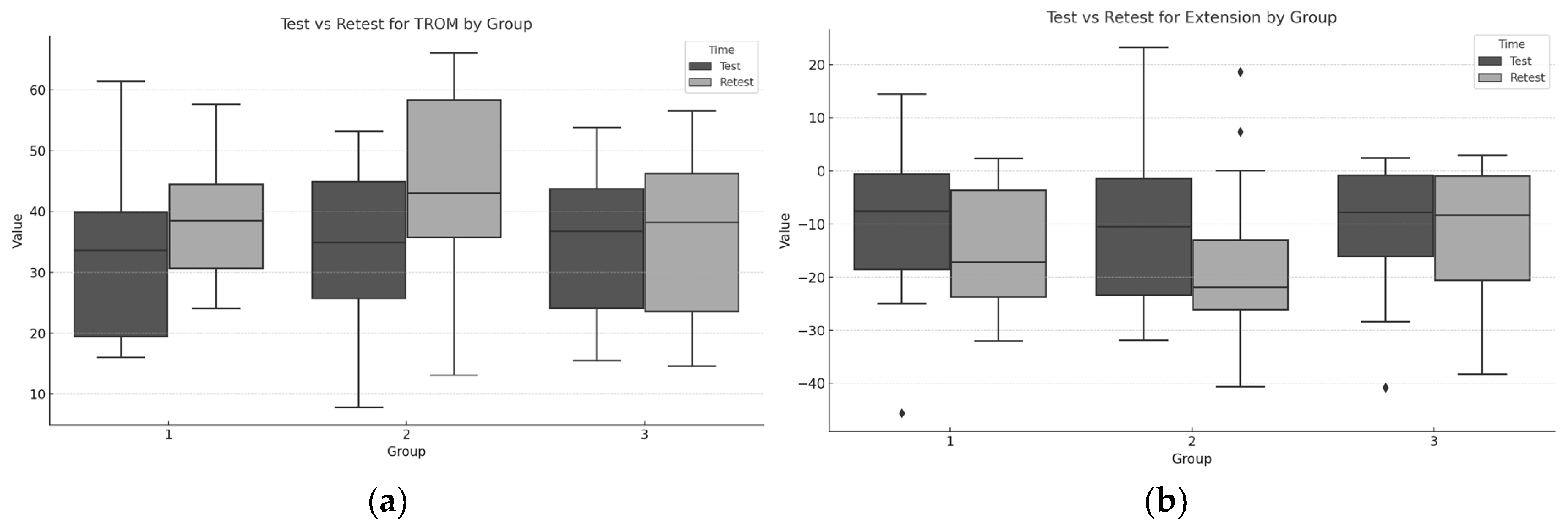

| Group | Flex test | Flex retest | d(CI) | Ext test | Ext retest | d(CI) | TROM test | TROM retest | d(CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG1 | 22.8 | 23.5 | -0.10 | -9.6 | -14.5 | 0.47 | 32.4 | 38.0 | 0.52 |

| (8.6) | (5.6) | (-0.48) | (14.2) | (10.5) | (-0.15) | (12.9) | (9.4) | (-0.85) | |

| EG2 | 24.1 | 26.4 | -0.47 | -10.2 | -18.3* | 0.83 | 34.4 | 44.7* | -1.12 |

| (6.4) | (6.1) | (-0.78) | (14.2) | (15.1) | (-0.05) | (12.0) | (14.0) | (-1.11) | |

| CG | 23.5 | 24.0 | -0.38 | -11.2 | -11.9 | 0.16 | 34.7 | 35.9 | -0.31 |

| (7.8) | (7.6) | (-0.52) | (11.9) | (12.4) | (-0.45) | (11.9) | (12.5) | (-0.64) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).