Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

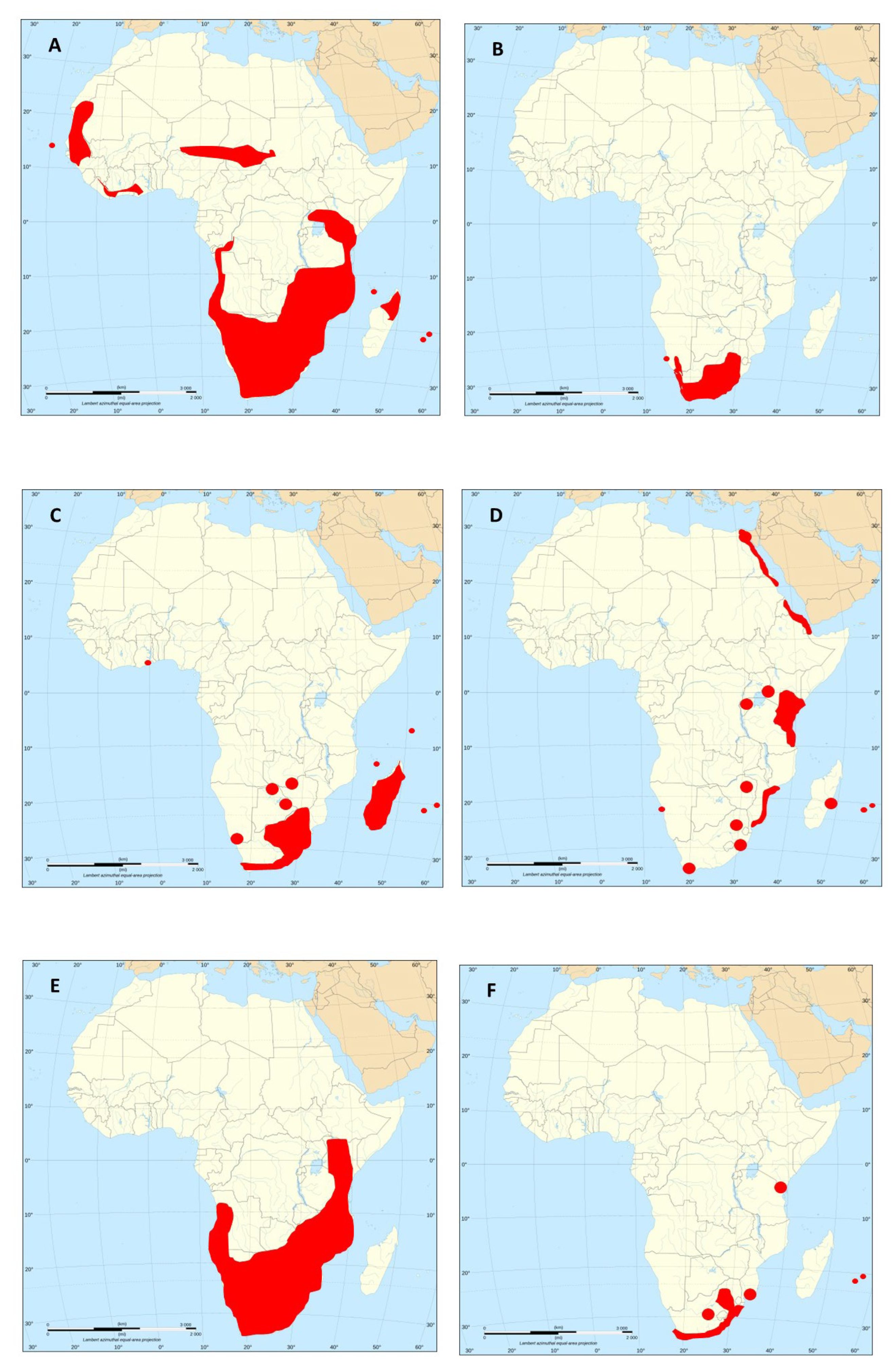

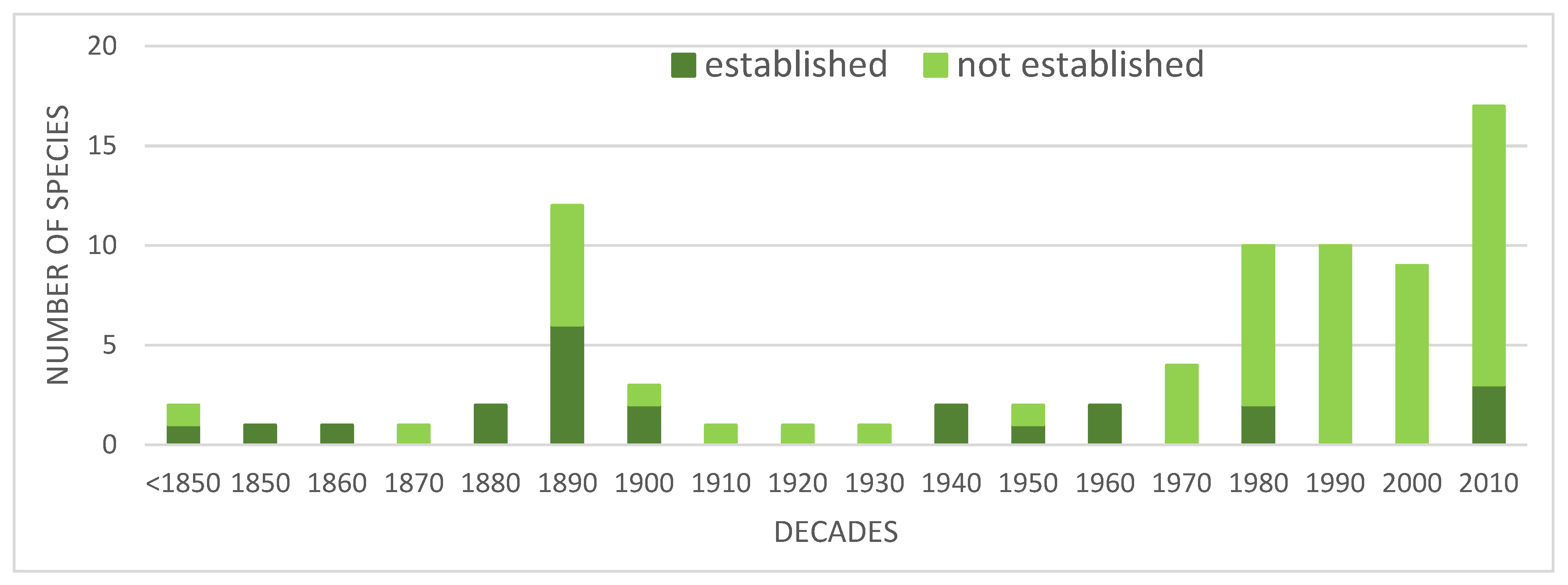

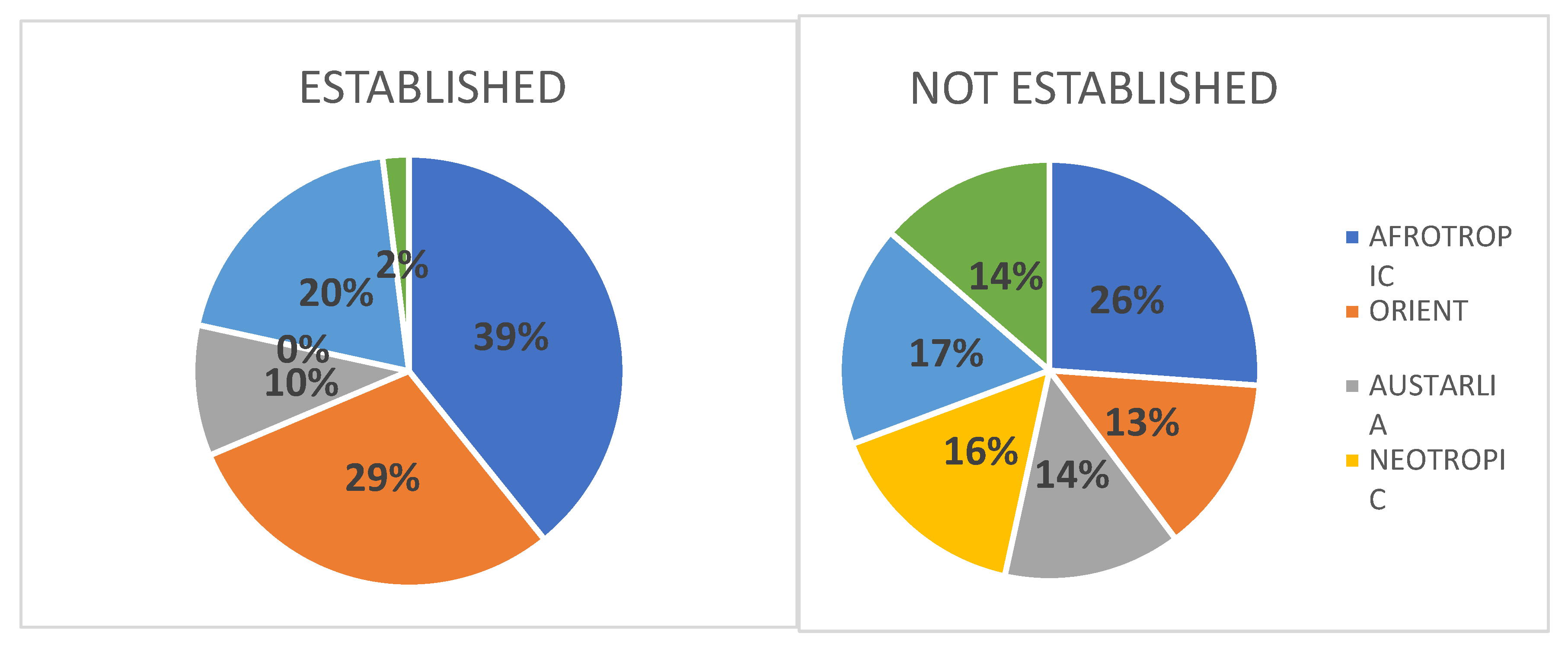

Introduced species may pose one of the biggest threat to the biodiversity conservation. Monitoring their status, distribution and abundance constitute today an important part of ecological and conservation studies throughout the world. In the Afrotropical Region (sub-Saharan Africa) avian introductions attract attention of many researchers, but there is a lack of comprehensive review of this subject on a continental scale. The presented paper constitutes an attempt to overview the status, distribution, threats and control measures of bird introduced in sub-Saharan Africa in the last 200 years. This review lists 150 bird species introduced in sub-Saharan Africa. Only 49 (32.7%) of them have developed viable populations and only 7 (4.7%) became invasive species, namely Passer domesticus, Sturnus vulgaris, Acridotheres tristis, Corvus splendens, Columba livia var. domestica, Psittacula krameria and Pycnonotus jocosus. Data on distribution of most introduced species are provided together with information on the place and year of their first introductions. For Passer domesticus and Columba livia var. domesticus data on population densities are also provided from several southern African towns. The most specious groups of introduced species were parrots (Psittaciformes) comprising 33.3% (including Pisittacidae: 14%, and Psittaculidae: 16%), Anatidae: 11.3%, Phasianidae: 11.3%, and Passeriformes: 29.3%. Most avian introductions in sub-Saharan Africa took place in Southern Africa (mainly Cape Town, Durban and Johannesburg areas) and in Madagascar and surrounding islands (mostly Mauritius, Reunion and Seychelles). Most introduced species which have developed viable populations originate from Afrotropical, Oriental and Palearctic regions (altogether 78%), with only 2% from the New World. The proportions among introduced species which have not established viable populations are quite different: 30% from the New World, and only 56% from the Afrotropical, Oriental and Palearctic regions (Figure 4). Main factors affecting successful avian introductions and introduction pathways have been identified. A review of control measurers undertaken in sub-Saharan Africa (mainly in small oceanic islands) is outlined for the following species: Passer domesticus, Acridotere tristis, Corvus splendens, Pyconotus jocosus, Foudia madagascarensis, Psittacula krameiri and Agapornis roseicollis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Indigenous species (native, autochthonous): species living within its natural range.

- Alien species (introduced, non-native, non-indigenous, foreign, exotic): species introduced by man intentionally or accidentally.

- Invasive alien species (invader): introduced species which has been introduced, to areas not previously occupied, establishing viable breeding population, spreads and becomes a pest affecting ecosysstem, local biodiversity, economy and society (including human health).

- Non-invasive alien species: introduced species with developed viable population of low dispersal abilities and not affecting adversely ecosystems, economy and society in the conquered areas.

- Translocated species: accidental escapee from aviary or enclosure; may reproduce in wild, but has not develop viable population.

- Post-invasive alien species (established, naturalized): a species introduced long time ago (before 1900), well-established in the wild, but without expansion tendencies.

- Cryptogenic species: unknown origin (alien or indigenous), its expansion may be shaped by natural or anthropogenic factors.

- Intentional introduction: purposeful relocation of a species beyond its natural range.

- Unintentional introduction: accidental relocation of a species beyond its natural range.

- Expansion: continuous natural enlargement of natural range by acquisition of the adjacent areas or natural occupation of new habitats within the original range

- Invasion (colonization): natural spread into new areas accompanied by a rapid and often explosive exponential population growth and changes in natural environment and human economy.

- Population stages: not established, developing, viable, established (naturalized.

- Population growth (dynamic): stable, increasing, declining, locally extinct.

- The types of invaded ecosystems can be grouped as follow:

- Natural ecosystem: natural formations not altered and not disturbed by man, usually in the climax stage.

- Semi-natural: natural formation modified/altered by human; in successive or/and climax stages.

- Artificial ecosystem: artificial formations created by man, not in a climax stage.

3. The Introduced Species

3.1. Invasive Alien Bird Species

3.1.1. House Sparrow

3.1.2. Common Starling

3.1.3. Indian Myna

3.1.4. House Crow

3.1.5. Rock Pigeon

3.1.6. Rose-ringed Parakeet

3.1.7. Red-whiskered Bulbul

3.2. Non-Invasive But Established Alien Bird Species

3.3. Not Established Alien Bird Species

4. General Characteristics of the Avian Introductions in Sub-Saharan Africa

4.1. Species Representativness

4.2. Factors Affecting Successful Introduction

4.3. Ecological Characteristic of Successful Species

4.4. Factors Affecting Unsuccessful Introductions

4.5. Introduction Pathways

5. Management and Nature Conservation Implications

5.1. Impact Categories

5.1.1. Hybridization

5.1.2. Competition

5.1.3. Predation

5.1.4. Disease Transmission

5.1.5. Parasitism

5.1.6. Human-Wildlife Conflict

5.1.7. Agricultural Pests

5.1.8. Seed Dispersal

5.2. Control Measures

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, F.; Sahi, D.N. Food and feeding habits of the Common Myna, Acridotheres tristis (Family: Sturnidae) at Jammu, Jammu and Kashmir. Ecoscan 2012, 6, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, N.; Khan, H.A.; Javed, M. Inhibiting the House Crow (Corvus splendens) damage on maize growth stages with reflecting ribbons in farmland. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2013, 23, 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S. The Book of Indian Birds, 13th ed. Oxford University Press, New Dehli, India, 2002.

- Anderson, T.R. Biology of the Ubiquitous House Sparrow: From Genes to Populations. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006.

- Avery, M.L.; Tillman, E.A. Alien birds in North America-challenges for wildlife managers, 2005.

- Bednarczuk, E.; Feare, C.J.; Lovibond, S.; Tatayah, V.; Jones, C.G. Attempted eradication of house sparrows Passer domesticus from Round Island (Mauritius), Indian Ocean Conserv. Evid. 2010, 7, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- BirdLife International. Invasive alien species have been implicated in nearly half of recent bird extinctions. In: BirdLife State of the World’s Birds. 2010 www.birdlife.org/datazone/sowb/casestudy/127.

- BirdLife International. Rock Dove: Columba livia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. Available at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ species/22690066/86070297.

- Blackburn, T.M.; Lockwood, J.L.; Cassey, P. Avian Invasions. Oxford University Press, New York, 2009.

- Blackburn, T.M.; Duncan, R.P. Determinants of establishment success in introduced birds. Nature 2001, 414, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, T.M.; Lockwood, J.L.; Cassey, P. Avian Invasions: The Ecology and Evolution of Exotic Birds. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009.

- Brochier, B.; Vangeluwe, D.; van den Berg, T. Alien invasive birds. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz. 2010, 29, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J. Invasive alien birds in South West Africa/Namibia. In: Brown, C.J., Macdonald, I.A.W. and Brown, S.E. (eds) Invasive Alien Organisms in South West Africa Namibia. South African National Scientific Programs Report, 1985, 119, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, B.W.; Sodhi, N.S.; Malcolm, C.K.S.; Lim, H.C. Abundance and projected control of invasive house crows in Singapore. J. Wildl. Manag. 2003, 67, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, R.K.; Lloyd, R.H.; De Viltiers, A.L. Alien and translocated terrestrial vertebrates in South Africa. In: The Ecology and Management of Biological Invasions in Southern Africa, eds. I.A.W Mac Donald, EJ. Kruger, A.A. Ferrar, pp. 63–74. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1986.

- Bunbury, N.; Mahoune, T.; Raguain, H.; Richards, H.; Fleischer-Dogley, F. Red-whiskered Bulbul eradicated from Aldabra. Aliens: Invas. Spec. Bull. 2013, 33, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bunbury, N. et al. Five eradications, three species, three islands: overview, insights and recommendations from invasive bird eradications in the Seychelles. In: Island Invasives 2017 Conference. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2019, 282-288.

- Butler, C.J. Population biology of the introduced Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri in the UK. Ph.D. thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, 2003.

- Canning, G. Eradication of the invasive common myna, Acridotheres tristis, from Fregate Island, Seychelles. Phelsuma 2011, 19, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Carié, P. Note sur l’acclimatation du Bulbul (Octocompsa jocosa L.) à l’île Maurice. Bulletin de la Société Nationale d’acclimatation 1910, 57, 462–464. [Google Scholar]

- Cheke, A. The timing of arrival of humans and their commensal animals on Western Indian Ocean oceanic islands. Phelsuma 2010, 18, 38–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chiron, F.; Shirley, S.; Kark, S. Human-related processes drive the richness of exotic birds in Europe. Proc. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. Sci., 2009, 276, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, N.J.; Olsson-Pons, S.; Ishtiaq, F.; Clegg, S.M. Specialist enemies, generalist weapons and the potential spread of exotic pathogens: malaria para sites in a highly invasive bird. Intern. J. Parasitol. 2015, 45, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, J.F.; Schulenberg, T.S.; Iliff, M.J.; Roberson, D.; Fredericks, T.A.; et al. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: 2018. www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/.

- Clergeau, P.; Mandon-Dalger, I. Fast colonization of an introduced bird: the case of Pycnonotus jocosus on the Mascarene Islands. Biotropica 2001, 33, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clergeau, P.; Lay, G.L.; Mandon-Dalger, I. Intégrer les analyses géographiques, écologiques et sociales pour gérer la faune sauvage. In: Legay, J.M. (ed.) L’Interdisciplinarité dans les Sciences de la Vie. Édition Cemagref, Antony Cedex, France, pp. 103–113, 2006.

- Cox, G.W. 1999. Alien Species in North America and Hawaii: Impacts on Natural Ecosystems. Island Press, Washington, DC.

- Craig, A.J.F.K. Common Myna. In: Hockey, P.A.R., Dean, W.R.J. and Ryan, P.G. (eds) Roberts Birds of Southern Africa, 7th edn. Trustees of the John Voelker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, p. 972, 2005.

- Craig, A.J.; Edwards, S. Counting Common Starlings: is Sturnus vulgaris invasive in rural South Africa? Ostrich, 2012, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowl, T.A.; Crist, T.O.; Parmenter, R.R.; Belovsky, G.; Lugo, A.E. The spread of invasive species and infectious disease as drivers of ecosystem change. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 6, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P. Is Namibia on the brink of being invaded by Common Starling Sturnus vulgaris? Biodiv. Observ. 2016, 7, 76–1. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, W.R.J. Alien birds in southern Africa: what factors determine success? S. Afr. J. Sci. 2000, 96, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, W.R.J. Rock Dove. In: Hockey, P.A.R., Dean, W.R.J. and Ryan, P. (eds) Roberts Birds of Southern Africa, 7th ed. Trustees of the John Voelker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, pp. 276–277, 2005a.

- Dean, W.R.J. House Crow. In: Hockey, P.A.R., Dean, W.R.J. and Ryan, P. (eds) Roberts Birds of Southern Africa, 7th ed. Trustees of the John Voelker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, pp.721–722, 2005b.

- Dean, W.R.J. House Sparrow. In: Hockey, P.A.R., Dean, W.R.J. and Ryan, P.G. (eds) Roberts Birds of Southern Africa, 7th ed. Trustees of the John Voelker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, pp. 1082–1083, 2005c.

- Douthwaite, R. Common Myna – a new bird species for Zambia. Kafue River Trust, 2015. http://www.kafuerivertrust.org/commonmyna-a-new-bird-species-for-zambia-2/.

- Downs, C.T.; Hart, L.A. (Eds.). (2020). Invasive birds: global trends and impacts. CABI.

- Dyer, E.E.; Cassey, P.; Redding, D.W.; Collen, B.; Franks, V.; Gaston, K.J.; et al. The global distribution and drivers of alien bird species richness. PLoS Biology, 2017, 15, e2000942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, E.E.; Redding, D.W.; Blackburn, T.M. The global avian invasions atlas, a database of alien bird distributions worldwide. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earlé, R.; Grobler, N. First Atlas of Bird Distribution in the Orange Free State. National Museum, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 1987.

- Engel, J.; Willard, D. The mynas are coming! A summary of common myna records in Namibia. Biodiv. Observ., 2017, 8, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Feare, C.J. The use of Starlicide in preliminary trials to control invasive Common Myna Acridotheres tristis populations on St Helena and Ascension islands, Atlantic Ocean. Conserv. Evid. 2010, 7, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Feare, C.J.; van der Woude, J.; Greenwell, P.; Edwards, H.; Taylor, J.A.; Larose, C.S.; Ahlen, P.-A.; West, J.; Chadwick, W.; Pandey, S.; Raines, K.; Garcia, F.; Komdeur, J.; de Groene, A. Eradication of common mynas from Denis Island, Seychelles. Pest Manag Sci. 2016, 73, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feare, C.J.; Waters, J.; Fenn, S.R.; Larose, C.S.; Retief, T.; Havemann, C.; et al. Eradication of invasive common mynas Acridotheres tristis from North Island, Seychelles, with recommendations for planning eradication attempts elsewhere. Manag. Biol. Invas. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feare, C.J.; Lebarbenchonb, C.; Dietrichc, M.; Larosed, C.S. Predation of seabird eggs by Common Mynas Acridotheres tristis on Bird Island, Seychelles, and its broader implications. Bull. ABC 2015, 22, 162–170. [Google Scholar]

- Feare, C.; Craig, A. 1998. Starlings and Mynas. Helm, London.

- Feare, C.J.; Mungroo, Y. The status and management of the House Crow Corvus splendens (Vieillot) in Mauritius. Biol. Conserv. 1990, 51, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feare, C.J.; van der Woude, J.; Greenwell, P.; Edwards, H.; Taylor, J.A.; Larose, C.S.; Ahlen, P.-A.; West, J.; Chadwick, W.; Pandey, S.; Raines, K.; Garcia, F.; Komdeur, J.; de Groene, A. Eradication of common mynas from Denis Island, Seychelles. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 73, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feare, C.J.; Waters, J.; Fenn, S.R.; Larose, C.S.; Retief, T.; Havemann, C.; Ahlen, P.-A.; Waters, C.; Little, M.K.; Atkinson, S.; Searle, B.; Mokhobo, E.; de Groene, A.; Accouche, W. Eradication of invasive common mynas Acridotheres tristis from North Island, Seychelles, with recommendations for planning eradication attempts elsewhere. Manag. Biol. Invas. 2021, 12, 700–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, M.; Larson, B.M.; Irlich, U.M.; Holmes, P.M.; Stafford, L.; van Wilgen, B.W.; Richardson, D.M. Managing invasive species in cities: a framework from Cape Town, South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 151, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, K.L.; Shuford, W.D.; Gill, R.E.; Handel, C.M. Introducing change: A current look at naturalized bird species in western North America. Trends and Traditions: Avifaunal Change in Western North America 2018, 3, 116–130. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt, E. Die gegenwärtige Verbreitung von Haussperling, Star und Buchfink in Südafrika. J. Orn. 1954, 95, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, E. Europäische Vögel in überseeischen Ländern. Bonner Zool. Beitr. 1959, 10, 310–342. [Google Scholar]

- Genovesi, P.; Shine, C. European strategy on invasive alien species. Nature and environment, 137. Council of Europe Publ., Strasbourg: 1-67, 2004.

- Glyphis, J.P.; Milton, S.J.; Siegfried, W.R. Dispersal of Acacia cyclops by birds. Oecologia 1981, 48, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.M.; Raselimanana, A.P.; Andriniaina, H.A.; Gauthier, N.E.; Ravaojanahary, F.F.; Sylvestre, M.H.; Raherilalao, M.J. The distribution and ecology of invasive alien vertebrate species in the greater Toamasina region, central eastern Madagascar. Malagasy Nature 2017, 12, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Grandi, G.; Menchetti, M.; Mori, E. Vertical segregation by breeding ring-necked parakeets Psittacula krameri in northern Italy. Urban Ecosyst. 2018, 21, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag-Wackernagel, D.; Moch, H. Health hazards posed by feral pigeons. J. Infection 2004, 48, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.A.; Allan, D.G.; Underhill, L.G.; Brown, C.J.; Tree, A.J.; Parker, V.; Herremans, M. (eds). The Atlas of Southern African Birds. Vol. 2. BirdLife South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1997.

- Hart, L.A.; Downs, C.T. Public surveys of Rose-ringed Parakeets, Psittacula krameri, in the Durban Metropolitan area, South Africa. Afr. Zool. 2014, 49, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.L.; Bacher, S.; Essl, F.; Hulme, P.E.; Jeschke, J.M.; et al. Framework and guidelines for implementing the proposed IUCN Environmental Impact Classification for Alien Taxa (EICAT). Divers. Distrib. 2015, 21, 1360–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.R.; Barry, S.C. Are there any consistent predictors of invasion success? Biol. Invas. 2008, 10, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Brito, D.; Carrete, M.; Popa-Lisseanu, A.G.; Ibáñez, C.; Tella, J.L. Crowding in the city: losing and winning competitors of an invasive bird. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Brito, D.; Carrete, M.; Ibáñez, C.; Juste, J.; Tella, J.L. Nest-site competition and killing by invasive parakeets cause the decline of a threatened bat population. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, G.M.; Cuthbert, R.J. The catastrophic impact of invasive mammalian predators on birds of the UK Overseas Territories: a review and synthesis. Ibis, 2010, 152, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockey, P.A.R.; Dean, W.R.J.; Ryan, P.G. Roberts Birds of Southern Africa, 7th edn. Trustees of the John Voelker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, 2005.

- Hockey, P.A.R.; Underhill, L.G.; Neatherway, M.; Ryan, P.G. Atlas of the birds of the Southwestern Cape. Cape Bird Club, 1989.

- Iriarte, J. Invasive vertebrate species in Chile and their control and monitoring by governmental agencies. Rev. Chilena Hist. Natur. 2005, 78, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.; Williams, R.N. Red-vented Bulbul (Pycnonotus cafer) and Red-whiskered Bulbul (Pycnonotus jocosus). In: Poole, A. and Gill, F. (eds) Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York, and the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2000. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/520b. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M. First record of Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri for Indonesia. BirdingAsia 2017, 25, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Invasive Species Specialist Group. Global Invasive Species Database, 2015. www.iucngisd.org/gisd/search.php.

- Jeschke, J.M. Across islands and continents, mammals are more successful invaders than birds. Divers. Distribut. 2008, 14, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.F. Geographic size variation in rock pigeons, Columba livia. Ital. J. Zool. 1992, 59, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.F.; Garrett, K.L. Population trends of introduced birds in western North America. Stud. Avian Biol. 1994, 15, 221–231. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.G. Parrot on the way to extinction. Oryx 1980, 15, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, H.J. Starlings and others. Ostrich 1945, 16, 214–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kamel, A.M. Potential impacts of invasive House Crows (Corvus splendens) bird species in Ismailia Governorate, Egypt: ecology, control and risk management. J. Life Sci. Technol. 2014, 2, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kark, S.; Solarz, W.; Chiron, F.; Clergeau, P.; Shirley, S. Alien birds, amphibians and reptiles of Europe. Handbook of alien species in Europe, 2009, 105-118.

- Khan, H.A.; Javed, M.; Zeeshan, M. Damage assessment and management strategies for House Crow (Corvus splendens L) on the seedling stages of maize and wheat in an irrigated agricultural farmland of Punjab, Pakistan. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2015, 3, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, C.S.; Lodge, D.M. Progress in invasion biology: predicting invaders. Tren. Ecol. Evol. 2001, 16, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komdeur, J. Breeding of the Seychelles Magpie Robin Copsychus sechellarum and implications for its conservation. Ibis 1996, 138, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Breeding bird community of the UOFS campus, Bloemfontein. Mirafra 1994, 11, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Birds of Bethlehem, Free State province, South Africa. Mirafra 1997, 14, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Birds of Maseru. NUL J. Res. (Roma, Lesotho) 2000, 8, 104–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Atlas of Birds of Bloemfontein. Department of Biology, National University of Lesotho/Free State Bird Club, Roma (Lesotho)/Bloemfontein (RSA), 2001a.

- Kopij, G. Birds of Roma Valley, Lesotho. Roma (Lesotho): Department of Biology, National University of Lesotho, 2001b.

- Kopij, G. The Structure of Assemblages and Dietary Relationships in Birds in South African Grasslands. Wydawnictwo Akademii Rolniczej we Wrocławiu, Wrocław, 2006.

- Kopij, G. Segregation in sympatrically nesting Red-winged Starling Onychognathus morio (L.) and European Starling Sturnus vulgaris L. Pol. J. Ecol. 2009, 57, 589–595. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Avian Assemblages in Urban Habitats in North–central Namibia. Intern. Sci. Technol. J. Nam. 2014, 3, 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Avian communities of a Mixed Mopane–Acacia Savanna in the Cuvelai Drainage System, North–Central Namibia, During the Dry and Wet Season. Vest. Zool. 2014, 48, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. The status of sparrows in Lesotho, southern Africa. Intern. St. Sparrows 2014, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Avian diversity in an urbanized South African grassland. Zool. Ecol. 2015, 25, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Birds of Katima Mulilo town, Zambezi Region, Namibia. Intern. Sci. Technol. J. Nam. 2016, 7, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Provisional atlas of breeding birds of Swakopmund in the coastal Namib Desert. Lanioturdus 2018, 51, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Atlas of breeding birds of Kasane. Babbler 2018, 64, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Population density and structure of birds breeding in an urban habitat dominated by large baobabs (Adansonia digitata), Northern Namibia. Bios. Divers. 2019, 27, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Structure of the breeding bird community along the urban gradient in a town on the Zambezi River, north–eastern Namibia. Biologija 2020, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Structure of avian communities of suburbs of Rundu and Grootfontein, NE Namibia. Berkut 2021, 30, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Population density and structure of a breeding bird community in a suburban habitat in the Cuvelai drainage system, northern Namibia. Arxius Misc. Zool. 2021, 19, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Seasonal changes in the structure of an avian community in an urban habitat in northern Namibia. Biologija 2021, 67, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Provisional atlas of breeding birds of Hentjes Bay in the coastal Namib Desert. Nam. J. Envir. 2022a, 6C: 1-6. https://www.nje.org.na/index.php/nje/article/view/volume6-kopij.

- Kopij, G. Avian diversity in urban habitats in the arid zone of Namibia. Lanioturdus 2022, 55, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kopij, G. Structure of breeding bird assemblages in the city of Windhoek, Namibia. Arxius Misc. Zool. 2023, 21, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Provisional atlas of breeding birds of Walvis Bay in the coastal Namib Desert. Biologija 2023, 69, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, C.R.; Galbraith, J.A.; Glen, A.S.; Nathan, H.W.; Stow, A.; Maclean, N.; Holwell, G.I. Invasive vertebrates in Australia and New Zealand. Austral Ark. The State of Wildlife in Australia and New Zealand 2014, 197–226. [Google Scholar]

- Langrand, O.; Sinclair, J.C. Additions and supplements to the Madagascar avifauna. Ostrich 1994, 65, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leven, M.R.; Corlett, R.T. Invasive birds in Hong Kong, China. Orn. Sci. 2004, 3, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, C. Naturalised Birds of the World. Longman Scientific and Technical, London, 1987.

- Lever, C. Naturalised Birds of the World. Poyser, London, 2005.

- Lincoln, F.C. The military use of the homing pigeon. Wilson Bulletin 2027, 39, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Linnebjerg, J.F.; Hansen, D.M.; Bunbury, N.; Olesen, J.M. Diet composition of the invasive Red-whiskered Bulbul Pycnonotus jocosus in Mauritius. J. tropic. Ecol. 2010, 26, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liversidge, R. The spread of the European Starling in the Eastern Cape. Ostrich 1962, 33, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liversidge, R. Alien bird species introduced into southern Africa. In Proceedings of the Birds and Man Symposium, ed. L. J. Bunning, pp. 31–44, 1985.

- Long, J.L. Introduced Birds of the World: The Worldwide History, Distribution and Influence of Birds Introduced to New Environments. Universe Books, New York, 1981.

- Martin-Albarracin, V.L.; Amico, G.C.; Simberloff, D.; Nuñez, M.A. Impact of Non-Native Birds on Native Ecosystems: A Global Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashao, M.; Mhlongo, S.N.; Nsibande, S.P.; Nxumalo, M.M.; Mncube, N.A. Records and distribution of House Crow Corvus splendens within the eThekwini Municipality from August 2019 to August 2023. Biodiv. Observ. 2023, 13, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meininger, P.L.; Mullie, W.C.; Bruun, B. The spread of the House Crow, Corvus splendens, with special reference to the occurrence in Egypt. Gerfaut 1980, 70, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mentil, L.; Battisti, C.; Carpaneto, G.M. The impact of Psittacula krameri (Scopoli, 1769) on orchards: first quantitative evidence for Southern Europe. Belg. J. Zool. 148, 129–134. [CrossRef]

- Meyerson, L.A.; Mooney, H.A. Invasive alien species in an era of globalization. Front. Ecol. Envir. 2007, 5, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, J.; Climo, G.; Shah, N.J. Eradication of the common myna Acridotheres tristis populations in the granitic Seychelles: successes, failures and lessons learned. Adv. Verteb. Pest Manag. 2004, 3, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, M. The Red-whiskered Bulbul Pycnonotus jocosus in Australia – a global perspective, history of introduction, current status and potential impacts. Aust. Zool. 2015, 37, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, M.P.; Cropper, W.P., Jr. A comparison of success rates of introduced passeriform birds in New Zealand, Australia and the United States. PeerJ. 2014, 2, e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebot, J. First report on the rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri) in Venezuela and preliminary observations on its behaviour. Orn. Neotropic. 1999, 10, 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Nxele, B.; Shivambu, C. House Crow (Corvus splendens) eradication measures from eThekwini Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J. Biodiv. Manag. Forest. 2018, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nyári, Á.; Ryall, C.; Townsend Peterson, A. Global invasive potential of the House Crow Corvus splendens based on ecological niche modelling. J. avian Biol. 2006, 37, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottens, G. Background and development of the Dutch population House Crows Corvus splendens. Limosa 2003, 76, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ottens, G.; Ryall, C. House Crows in the Netherlands and Europe. Dutch Birding 2003, 25, 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Pârâu, L.G.; Strubbe, D.; Mori, E.; Menchetti, M.; Ancillotto, L.; Kleunen, A.V.; et al. Rose-ringed parakeet Psittacula krameri populations and numbers in Europe: a complete overview. Open Orn. J. 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, M.P.; van Rensburg, B.J.; Robertson, M.P. The distribution and spread of the invasive alien Common Myna, Acridotheres tristis L. (Aves: Sturnidae), in southern Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2007, 103, 465–473. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin, R.; Cowgill, R. Rose-ringed parakeet Psittacula krameri. In: Hockey, P.A.; Dean, W.R., Ryan, P.G.; Maree, S.; Brickman, B.M. (eds), Roberts birds of southern Africa, 7th ed. Cape Town: Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, pp 229–230, 2005.

- Phair, D.J. Dispersal strategies, rapid geographic range expansion and their effects on invasive European starlings, Sturnus vulgaris, in South Africa and Australia (Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University), 2015.

- Pisanu, B.; Laroucau, K.; Aaziz, R.; Vorimore, F.; Le Gros, A.; Chapuis, J.L.; Clergeau, P. Chlamydia avium detection from a Ring-necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) in France. J. Exot. Pet Medic. 2018, 27, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska, K.; Haidt, A.; Myczko, Ł.; Ekner-Grzyb, A.; Rosin, Z.M.; et al. Local and landscape-level factors affecting the density and distribution of the Feral Pigeon Columba livia var. domestica in an urban environment. Acta orn. 2012, 47, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Puttoo, M.; Archer, T. Control and/or eradication of Indian crows (Corvus splendens) in Mauritius. Agric. Sugar Rev. Mauritius 2004, 83, 209–399. [Google Scholar]

- Quickelberge, C.D. Birds of the Transkei. Durban Natural History Museum, Durban, South Africa, 1989.

- Rose, E.; Nagel, P.; Haag-Wackernagel, D. Spatio-temporal use of the urban habitat by feral Pigeons (Columba livia). Beh. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2006, 60, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryall, C. Predation and harassment of native bird species by the Indian House Crow Corvus splendens in Mombasa, Kenya. Scopus 1992, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ryall, C. Further records of range extension in the House Crow Corvus splendens. Bull. B.O.C. 2002, 122, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ryall, C. Further records and updates of range extension in House Crow Corvus splendens. Bull. B.O.C. 2010, 130, 246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ryall, C. Further records and updates of range expansion in House Crow Corvus splendens. Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136.

- Ryall, C.; Reid, C. The Indian House Crow in Mombasa. Swara 1987, 10, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi, R.; Gentilli, A.; Razzetti, E.; Barbieri, F. Effects of building features on density and flock distribution of feral Pigeons Columba livia var. domestica in an urban environment. Can. J. Zool. 2002, 80, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schrey, A.W.; Liebl, A.L.; Richards, C.L.; Martin, L.B. Range expansion of house sparrows (Passer domesticus) in Kenya: evidence of genetic admixture and human-mediated dispersal. J. Hered. 2014, 105, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimba, M.J.; Jonah, F.E. Nest success of the Indian House Crow Corvus splendens: an urban invasive bird species in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Ostrich 2016, 88, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivambu, T.C.; Shivambu, N.; Downs, C.T. Impact assessment of seven alien invasive bird species already introduced to South Africa. Biol. Invas. 2020, 22, 1829–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivambu, T.C.; Shivambu, N.; Downs, C.T. Population estimates of non-native rose-ringed parakeets Psittacula krameri (Scopoli, 1769) in the Durban Metropole, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Urban Ecosyst., 2021, 24, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwartz, A.; Strubbe, D.; Butler, C.J.; Matthysen, E.; Kark, S. The effect of enemy-release and climate conditions on invasive birds: a regional test using the Rose-ringed Parakeet (Psittacula krameri) as a case study. Diver. Distrib. 2009, 15, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Von Holle, B. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: invasional meltdown? Biolog. Invas. 1999, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, I. Birds of the Indian Ocean Islands. Penguin Random House, South Africa, 2013.

- Skead, C.J. Life-history Notes on East Cape Bird Species 1940–1990. Algoa Regional Services Council, Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 1995.

- Sol, D.; Bartomeus, I.; Griffin, A.S. The paradox of invasion in birds: competitive superiority or ecological opportunism? Oecologia 2012, 169, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, D.; Lefebvre, L. Behavioural flexibility predicts invasion success in birds introduced to New Zealand. Oikos 2000, 90, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, C.A.; Dickinson, J.L. Pigeons. In: Michael, D.B. and Janice, M. (eds) Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior. Academic Press, London, pp. 723–730, 2010.

- Stephens, K. Impacts of invasive birds: assessing the incidence and extent of hybridization between invasive Mallard Ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) and native Yellow-billed Ducks (Anas undulata) in South Africa. M.Sc. thesis. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University, 2019.

- Strubbe, D.; Matthysen, E. Experimental evidence for nest-site competition between invasive Ring-necked Parakeets (Psittacula krameri) and native nuthatches (Sitta europaea). Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1588–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A.; Meier, G.; Haverson, P. Confirmed eradication of the House Crow from Socotra Island, Republic of Yemen. Wildlife Middle East 2009, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, A.S.; Taleb, N. Eradication of the house crow Corvus splendens on Socotra, Yemen. Sandgrouse 32, 136–140.

- Suliman, A.S.; Meier, G.G.; Haverson, P.J. Eradication of the House Crow from Socotra Island, Yemen. In: Veitch, C.R., Clout, M.N. and Towns, D.R. (eds) Island Invasives: Eradication and Management. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, pp. 361–363, 2011.

- Summers-Smith, J.D. The House Sparrow, 1st ed. Collins, London, 1963.

- Summers-Smith, J.D. The Sparrows: A Study of the Genus Passer. A. & C. Black Publishers, London, 1988.

- Summers-Smith, J.D. In Search of Sparrows. Academic Press. London, 1992.

- Summers-Smith, J.D. The decline of the House Sparrow: a review. British Birds 2023, 96, 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Summers-Smith, J.D. The decline of the house sparrow: A review. British Birds 2003, 96, 439–446. [Google Scholar]

- Symes, C.T. Founder populations and the current status of exotic parrots in South Africa. Ostrich 2014, 85, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N. Common Mynas in Namibia. Lanioturdus 2014, 47, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Trezza, F.R.; da Costa Nerantzoulis, I.; Cianciullo, S.; Mabilana, H.; Macamo, C.; Attorre, F.; Bento, C.M.; Perazzi, P.R. Presence of the alien Rose-ringed Parakeet Psittacula krameri (Psittacidae) in Mozambique, Ostrich 2023, 94, 129–134. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, S.J. Common Mynahs continue to spread. Babbler 2015, 61, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Uranie, S. Eradication success – Seychelles wins war against invasive Red-whiskered Bulbul. Seychelles News Agency, 2015. www. seychellesnewsagency.com/articles.

- Yap, C.A.M.; Sodhi, N.S. Southeast Asian invasive birds: ecology, impact and management. Orn. Sci. 2004, 3, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemen, A.; Suleiman, S.; Taleb, N. Eradication of the House Crow Corvus splendens on Socotra. Sandgrouse 2010, 32, 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe, F. ’n Nalatenskap van Rhodes: Europese spreeus verdring gryskopspegte. Afr. Wildl. 1984, 38, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Vall-llosera, M.; Cassey, P. Leaky doors: Private captivity as a prominent source of bird introductions in Australia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rensburg, B.J.; Peacock, D.S.; Robertson, M.P. Biotic homogenization and alien bird species along an urban gradient in South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 92, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierke, J. Die Besiedlung Sudafrikas durch den Haussperling (Passer domesticus). J. Orn. 1970, 111, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.W. On the breeding habits of some African birds. Ibis 1949, 91, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.A. First documented nesting of the Red-whiskered Bulbul Pycnonotus jocosus in Taiwan. Taiwan J. Biodiv. 2011, 13, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, W.J. Health Hazards from Pigeons, Starlings and English Sparrows: Diseases and Parasites Associated with Pigeons, Starlings, and English Sparrows which Affect Domestic Animals. Thomson Publications, Fresno, California, 1979.

- Williamson, M.; Fitter, A. The varying success of invaders. Ecology 1996, 77, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterbottom, J.M.; Liversidge, R. The European Starling in the South West Cape. Ostrich 1954, 25, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witmer, G.W.; Burke, P.W.; Pitt, W.C.; Avery, M.L. Management of invasive vertebrates in the United States: an overview, 2007.

| Scientific species name | Common species name | Original range | Expanded range in Africa | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acridotheres tristis Sturnidae | Common Myna | SE Asia | South Africa (Durban: 1888, Gauteng, Mpumalanga, KZN, FS), Lesotho | high |

|

Columba livia Columbidae |

Rock Dove | S Palearctic | South Africa: 1850; all over sub-Saharan Africa | high |

|

Passer domesticus Passeridae |

House Sparrow | India | South Africa: Durban: 1893; till 1950’s confined to KZN; S and E Africa; Sahel zone, Senegal; Ivory Coast, Ghana | high |

|

Sturnus vulgaris Sturnidae |

Common Starling | Europe | South Africa: Cape Town: 1897, W Cape: 1950’s, E Cape: 1960’s, KZN: 1970’s | high |

|

Corvus splendens Corvidae |

House Crow | SE Asia | Zanzibar: 1890’s; Kenya: 1947; Durban: 1972, Cape Town: 1979; Socotra: 1994; establ.: SA, Tanzania, Kenya, Socotra | high |

| Psittacula krameri Psittaculidae | Rose-ringed Parakeet | W Africa, SE Asia | SA: Cape Town: 1860, Durban: 1970’s, Gauteng; Socotra; Maurit., Zanzibar, Kenya, Cape Verde; Seychelles: 1970’s | high |

| Pycnonotus jocosus Pycnonotidae | Red-whisker. Bulbul | SE Asia | Established in Mauritius: 1892, Reunion: 1972; Seychelles: 1977; present in: Madagacar, South Africa, Zimbabwe | high |

|

Alectoris chukar Phasianidae |

Chukar Partridge | Eurasia | Robben Island: 1964 | medium |

|

Gallus gallus Phasianidae |

Red Junglefowl | Orient | South Africa: KZN, Mpumalanga (Gravellote); Reunion; Mayotte | medium |

|

Numida meleagris Numidae |

Helmeted Guineafowl | Africa | Cape Verde, Comoros | medium |

| Anas platyrhynchos Anatidae | Mallard | Holarctic | South Africa: 1940’s; Gauteng: 1980’s, W Cape; Madagascar, Reunion, Mauritius | medium |

|

Bubulcus ibis Ardeidae |

Cattle Egret | Africa, Asia | Seychelles and possibly Rodrigues Island | medium |

|

Geopelia placida Columbidae |

Peaceful Dove | Australia | Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, Réunion, Glorioso Islands, Rodrigues | medium |

| Geophila striata Columbidae | Zebra Dove | Australia | Seychelles; ‘hundreds of thousands of individuals’ | medium |

| Agapornis canus Psittaculidae | Madagascar Lovebird | Madaga-scar | Rodrigues, Réunion, Comoros, Seychelles; unsuccessful (unsuc.) to Mauritius, Zanzibar, Mafia Islands, South Africa | medium |

| Agapornis fischeri Psittaculidae | Fischer’s Lovebird | E. Africa | Tanga (Tanzania), S Kenya; Cape St. Francis: 2014 | medium |

| Agapornis lillianae Psittaculidae | Nyasa Lovebird | E. Africa | Possibly introduced successfully to Zambia (Lundazi), Namibia and South Africa (Pretoria: 2013) | medium |

| Agapornis personatus Psittaculidae | Masked Lovebird | E. Africa | Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Nairobi, Kenya | medium |

| Agapornis roseicollis Psittaculidae | Rosy-faced Lovebird | SW Africa | South Africa: Johannesburg: c. 1984, successful (suc.); Modimolle: 1993, Cape Town: 2008; Durban: 2008 | medium |

|

Tyto alba Tytonidae |

Barn Owl | Global | Seychelles: 1949; introduced to controls rats; preys on the endagered Fairy Tern (EN) nests in small islands | medium |

| Foudia madagasca-riensis Ploceidae | Madagascar Fody | Madaga-scar | Suc.: Seychelles (Amirantes),Mauritius, Réunion, Rodrigues and possibly Comoros and Glorioso Islands |

medium |

|

Quelea quelea Ploceidae |

Red-billed Quelea | Africa | Successfully introduced to Réunion | medium |

|

Estrilda astrild Estrildidae |

Common Waxbill | Africa | Suc.:Mauritius, Rodrigues, Amirantes, Seychelles, Réunion, Cape Verde, São Tomé; unsuc.: Madagascar |

medium |

| Coturnix coturnix Phasianidae | Common Quail | Palearctic | Successful: Reunion; unsuccessful: Seychelle, Mauritius, Comores | low |

| Coturnix chinensis Phasianidae | Blue-breasted Quail | Orient, Australia | Mauritius, Kenya | low |

| Francolinus pinte-deanus Phasianidae | Chinese Francolin | China | Successfully introduced to Mauritius andpossibly to Madagascar and Seychelles; unsuccessful: Reunion | low |

|

Pavo cristatus Phasianidae |

Common Peacock | SE Asia | Robben Island: 1968; Cape Town, Bloemfontein | low |

|

Aix galericulata Anatidae |

Mandarin Duck | Palearctic | South Africa: Johannesburg: 1980, as breeding | low |

|

Aix sponsa Anatidae |

Wood Duck | Nearctic | South Africa: Durban: 1880, as feral | low |

|

Turnix nigricollis Turnicidae |

Madagascar Buttonquail | Madaga-scar | Glorioso Islands and Réunion; unsuccessfully introduced to Mauritius | low |

|

Nesoenas picturatus Columbidae |

Malagasy Turtle-dove | Madaga-scar | Possibly successfully introduced: Mauritius and Réunion (perhaps native); N. p. picturatus succ. in Seychelles |

low |

|

Spilopelia chinensis Columbidae |

Spotted Dove | Orient | Mauritius | low |

| Steptopelia decaocto Columbidae | Collared Dove | Pelearctic | Successgul: Cape Verde; unsuccessful: South Africa: Cape Town area | low |

| Melopsittacus undu-latus Psittacidae | Budgerigar | Australia | South Africa: KZN: 1958; Pretoria: 1987; Melville: 1995; Swakopmund: 2001; Johannesburg: 2013 | low |

| Psittacus erithacus Psittaculidae | African Grey | C Africa | South Africa: Pietermaritzburg: 2013 | low |

| Nymphicushollandic-us Cacatuidae | Cockatiel | Australia | South Africa (WC, G) | low |

|

Estrilda amandava Estrildidae |

Red Avadavat | Orient | Successful: Reunion, Mayotte; unsuccessful: South Africa (Rosherville), Mauritius | low |

| Lonchura punctulata Estrildidae | Scaly-breasted Munia | Orient | Successful: Mauritius, Reunion; unsuccessful: Seychelles; Estrildidae | low |

| Lonchura oryzivora Estrildidae | Java Sparrow | Orient | South Africa: Port Alfred, Tanzania: Zanzibar; unsuccessful: Mauritius, Comoros, Seychelles, | low |

| Uraeginthus angolen-sis Estrildidae | Blue-breasted Cordon-bleu | Africa | Introduced possibly successfully to Zanzibar and São Tome e Principe | low |

| Passer hispaniolensis Passeridae | Spanish Sparrow | S Palearctic | Cape Verde | low |

| Ploceus cucullatus Ploceidae | Village Weaver | Africa | Successful: Mauritius, probably to Réunion, possibly colonized or introduced to São Tomé; unsuc.: Cape Verde | low |

| Ploceus melanocepha-lus Ploceidae | Black-headed Weaver | Africa | Possibly introduced successfully to São Tomé | low |

| Carduelis carduelis Fringillidae | Goldfinch | Palearctic | Successful: Cape Verde; unsuccessful: Cape Town: 1891 | low |

| Crithagra mozambica Fringillidae | Yellow-front. Canary | Africa | Reunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, São Tome e Principe | low |

| Fringilla coelebs Fringillidae | Common Chaffinch | Eurasia | Cape Town: 1890’s, Cape Peninsula | |

|

Serinus canicollis Fringillidae |

Cape Canary | Africa | Reunion; unsuc.: Mauritius | low |

| Species scientific name | Species common name | Origin | Range after introduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agapornis canus Psittaculidae | Grey-headed Parrot | Madagasc. | SA, KZN, 1890+; Mayotte, Kenya |

| Agapornis meyerii Psittaculidae | Meyer’s Parrot | Afrotropic | SA: Cape Town + |

| Agapornis personatus Psittaculidae | Yellow-collared Lovebird | Afrotropic | SA, 2011-2023, Kenya |

| Agapornis pullarius Psittaculidae | Red-headed Lovebird | Afrotropic | Mayotte |

| Agapornis nigrigenis Psittaculidae | Black-cheeked Lovebird | Afrotropic | SA, Pretoria, 2005 |

| Aix sponsa Anatidae | Wood Duck | Nearctic | SA: 4 sites, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2001, 2002 |

| Alectoris melanocephala Phasianidae | Arabian Partridge | Arabia | Eritrea + |

| Amazona aestiva Psittacidae | Blue-fronted Amazon | Neotropic | SA: Pinetown, 1989 |

| Amazona amazonica Psittacidae | Orange-winged Amazon | Neotropic | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Amazona oratrix Psittacidae | Yellow-headed Amazon | Neotropic | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Anas rubripes Anatidae | American Black Duck | Nearctic | SA: Durban, 1975 |

| Anser anser Anatidae | Feral Graylag Goose | Palearctic | SA, 18th cen. |

| Ara ararauna Psittacidae | Blue-and-yellow Macaw | Neotropic | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Aratinga jandaya Psittacidae | Jandaya Conure | Neotropic | SA: KZN, c.2005 |

| Aratinga pertinax Psittacidae | Brown-throated Conure | Neotropic | SA: E. Cape, before 1983 |

| Aratinga solstitialis Psittacidae | Sun Conure | Neotropic | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Aratinga weddellii Psittacidae | Dusky-headed Conure | Neotropic | SA: KZN, c. 2005 |

| Aythya ferrina Anatidae | Common Pochard | Pelearctic | SA: Cape Peninsula |

| Aythya fuilgua Anatidae | Tufted Duck | Pelearctic | SA: Pietermaritzburg |

| Aythya nyroca Anatidae | Ferrugineus Duck | Palearctic | SA: Gauteng, 1994 |

| Cacatua sulphurea Cacatuidae | Yellow-crested Cockatoo | Oriental | SA: Pretoria, 1976-1983 |

| Callipepla californica Odontophoridae | California Quail | Nearctic | SA + |

| Callonecta leucophrys Anatidae | Ringed Teal | Neotropic | SA: Vaalkop Dam, 1985 |

| Ciarina moschata Anatidae | Muscovy Duck | Oriental | SA, Mayotte, |

| Colinus virginianus Phasianidae | Northern Bobwhite | Nearctic | Harare, Drakensberg |

| Columbina inca Columbidae | Inca Dove | Neotropic | SA: E Cape, 1992 |

| Coracias cyanogaster Corvidae | Blue-bellied Roller | Afr., Sahel | SA: NW Province, 2003 |

| Coracopsis vasa Psittrichasidae | Greater Vasa Parrot | Madag. | Unsuc. Reunion + |

| Corvus albus Corvidae | Pied Crow | Afrotropic | Mauritius; Mayotte |

| Corvus frugilegus Corvidae | Rook | Pelearctic | SA, late 1890’s + |

| Cyanoliseus patagonus Psittacidae | Burrowing Parrot | Neotropic | SA: Midrand, 1999 |

| Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae Psittacidae | Red-crowned Parakeet | New Zealand | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Cygnus atratus Anatidae | Black Swan | Australian | SA: Humansdorp, 1926 |

| Cygnus olor Anatidae | Mute Swan | Palearctic | SA: E. Cape, 1918; W Cape, Nyanga (Zim.) |

| Dendrocitta vagabunda Psittacidae | Rufous Treepie | Orient | Cape Town, 1997 |

| Dendrocygna autumnalis Anatidae | Black-bellied W. Duck | Neotropic | SA: Vaalkop Dam, 1997 |

| Eclectus roratus Psittaculidae | Moluccan Eclectus | Moluccas | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Eolophus roseicapilla Cacatuidae | Galah Cockatoo | Australian | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Eudocimus ruber Threkiornithidae | Scarlet Ibis | Neotropic | SA: KZN, 2000-2001 |

| Falco columbarius Falconidae | Merlin | Palearctic | SA: KZN, 1991 |

| Forpus passerinus Psittacidae | Green-rumped Parrotlet | Neotropic | SA: Durban, 1870’s + |

| Foudia sechellarum Ploceidae | Seychelles Fody | Seychelles | Sech.: Amirante Islands + |

| Fulica americana Rallidae | American Coot | Nearctic | SA: Durban, 1891 + |

| Gallinula commeri Rallidae | Gough Moorhen | Gough Is. | SA: Cape Town, 1893 + |

| Gallinula nesiotis Rallidae | Tristan Moorhen | TdC, G.Is. | SA: Cape Town 1893 |

| Gallus sonneratii Phasianidae | Grey Junglefowl | Oriental | SA |

| Geopelia cuneata Columbidae | Diamont Dove | Australian | Mauritius (before 1768), Seychelles, Réunion, SA |

| Gracula religiosa Sturnidae | Common Hill Myna | Orient | Reunion |

| Lamprotornis iris Sturnidae | Emerald Starling | W Africa | SA: Midrand, 1993 |

| Lamprotornis superbus Sturnidae | Superb Starling | E Africa | SA: Durban, 1993, 1998 |

| Leiothrix argentauris Leiotrichidae | Silver-eared Mesia | Orient | SA: Gauteng, 2002 |

| Leiothrix lutea Leiotrichidae | Red-billed Mesia | Orient | Reunion |

| Lonchura striata Estrildidae | White-rumped Munia | Orient | Reunion + |

| Lophura nycthemera Phasianidae | Silver Pheasant | Oriental | SA: Ceres (W Cape) |

| Luscinia megarhynchos Turdidae | Nightingale | Pelearctic | SA, late 1890’s + |

| Margaroperdix magagascarensis Phasianidae | Madagascar Partridge | Madagasc. | Mauritius, Reunion + |

| Melanocorypha bimaculate Alaudidae | Bimaculated Lark | NE Africa | Nam.: Swakompund, 1930 |

| Meleagris gallopavo Phasianidae | Wild Turkey | Nearctic | Unsuc. Mauritius + |

| Musophaga violacea Musophagidae | Violet Turaco | Afr., Sahel | Johannesburg, 1994-1995 + |

| Myiopsitta monachus Psittacidae | Monk Parakeet | Neotropic | SA? |

| Aratinga nenday Psittacidae | Black-hooded Conure | Neotropic | SA: E. Cape, before 1983; Johannesburg, 2001 |

| Neophema pulchella Psittaculidae | Turquoise Parrot | Australian | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Neopsephotus bourkii Psittaculidae | Bourke’s Parrot | Australian | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Netta rufina Anatidae | Red-crested Pochard | Palearctic | Zim., 1986; SA: 1996, 2003 |

| Nymphicus hollandicus Cacatuidae | Cockatiel | Australian | SA: Cape Town; Pretoria 1987 |

| Ortygornis pondicerianus Phasianidae | Gray Francolin | Orient | Reunion |

| Oxyura jamaicensis Anatidae | Ruddy Duck | Nearctic | SA |

| Paroaria coronata Thraupidae | Red-crested Cardinal | Neotropic | SA: W. Cape, 1958 |

| Paroaria dominicana Thraupidae | Red-cowled Cardinal | Neotropic | SA: Durban, 1960’s |

| Passer montanus Passeridae | Eurasian Tree Sparrow | Palearctic | Reunion |

| Pastor roseus Sturnidae | Rosy Starling | Palearctic | Mauritius |

| Perdicula asiatica Phasianidae | Jungle bush-quail | Orient | Reunion |

| Phasianus colchicus Phasianidae | Common Pheasant | Palearctic | SA: W Cape (4 sites), Kimberley; 1900-1950 + |

| Platycercus elegans Psittaculidae | Crimson Rosella | Australian | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Platycercus eximius Psittaculidae | Eastern Rosella | Australian | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Ploceus capensis Ploceidae | Cape Weaver | Afrotropic | Mauritius |

| Ploceus intermedius Ploceidae | Lesser Masked Weaver | Afrotropic | Socotra |

| Ploceus nigerrimus Ploceidae | Vieillot’s Black Weaver | W, E Afr. | SA: Durban, 2001-2002 + |

| Poicephalus cryptoxanthus Psittacidae | Brown-headed Parrot | Afrotropic | SA: Johannesburg, 1977 |

| Poicephalus gulielmi Psittacidae | Red-fronted Parrot | Afrotropic | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Poicephalus meyeri Psittacidae | Meyer’s Parrot | Afrotropic | SA, Johannesburg, 1981 |

| Poicephalus rueppellii Psittacidae | Ruppell’s Parrot | Afrotropic | SA: Pretoria, 2007, 2013 |

| Poicephalus rufiventris Psittacidae | Red-bellied Parrot | Afrotropic | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Poicephalus senegalus Psittacidae | Senegal Parrot | Afrotropic | SA, 2011-2023, Liberia |

| Poicephalus suahelicus Psittacidae | Grey-headed Parrot | Afrotropic | SA: Johannesburg, 2009 |

| Psittacula cyanocephala Psittaculidae | Plum-headed Parakeet | Oriental | SA: Pretoria, c.1979 +; Pietermaritzburg, 1899 + |

| Psittacula eupatria Psittaculidae | Alexandrine Parakeet | Orient | Socotra |

| Pyrrhura molinae Psittacidae | Green-cheeked Conure | Neotropic | SA, 2011-2023 |

| Spermestes cucullata Estrildidae | Bronze Mannikin | Afrotropic | Mayotte |

| Streptopelia capicola Columbidae | Ring-necked dove | Afrotropic | Mayotte |

| Streptopelia picturata Columbidae | Malagasy Turtle-dove | Madagasc. | Mayotte |

| Synoicus sinensis Phasianidae | Asian Blue Quail | Australian | Mauritius, Réunion + |

| Tadorna tadorna Anatidae | Common Shelduck | Pelearctic | SA: 5 records: 1974, 1985, 1989, 1990, 1995 |

| Taenipygia guttata Estrildidae | Zebra Finch | Australian | SA: Gauteng,1984; E Cape |

| Turdus merula Turdidae | Blackbird | Pelearctic | SA, late 1890’s, 1923 + |

| Turdus philomelos Turdidae | Song Thrush | Pelearctic | SA, late 1890’s, 1947 + |

| Turtur tympanistra Columbidae | Tambourine Dove | Afrotropic | Mayotte |

| Uraeginthus bengalus Estrildidae | Red-cheeked Cordon-blue | Sahel zone | Unsuc. Cape Verde + |

| Vidua macoura Viduidae | Pin-tailed Whydah | Afrotropic | Unsuc. Mayotte + |

| Vidua paradisea Viduidae | Eastern Paradise Whydah | Afrotropic | São Tome e Principe |

| Town | Sample size |

Year | H. Sparrow | Rock Pigeon | Source | ||

| D | %D | D | %D | ||||

| Bloemfontein, whole, SA | 5100ha | 1997 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 1.5 | Kopij 2015 |

| Bloemfontein, city centre, SA | 123 ha | 1994 | 25.0 | 13.7 | 15.0 | 8.2 | Kopij 1996 |

| Bloemfontein, resid. area, SA | 55 ha | 1993 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 | Kopij 1994 |

| Bethlehem, city centre, SA | 55 ha | 1996 | 10.9 | 16.9 | 7.3 | 11.3 | Kopij 1997 |

| Bethlehem, residen. area, SA | 326 p. | 1996 | - | 0.9 | - | 0.6 | Kopij 1997 |

| Bethlehem, industr. area, SA | 89 p. | 1996 | - | 41.6 | - | 0.0 | Kopij 1997 |

| Maseru, Lesotho | 1631 p. | 1996-99 | - | 3.3 | - | 1.3 | Kopij 2000a |

| Roma, Lesotho | 82 ha | 1998-01 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Kopij 2019 |

| Semonkong, Lesotho | 460 p. | 1996-02 | - | 8.5 | - | 0.0 | Kopij 2011 |

| Thaba Tseka, Lesotho | 657 p. | 1996-02 | - | 5.5 | - | 0.0 | Kopij 2011 |

| Mokhotlong, Lesotho | 339 p. | 1996-02 | - | 13.6 | - | 0.0 | Kopij 2011 |

| Morija, Lesotho | 295 p. | 1996-02 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | Kopij 2011 |

| Lesotho, 14 large villages | 533 p. | 1996-02 | - | 5.2 | - | 0.0 | Kopij 2011 |

| Windhoek, C Namibia | 5139 p. | 2011-14 | - | 5.3 | - | 4.1 | Kopij 2023a |

| Hentjes Bay, W Namibia | 345 ha | 2016/17 | 4.1 | 16.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Kopij 2022a |

| Swakopmund, W Namibia | 415 ha | 2016/17 | 1.7 | 7.1 | 3.2 | 13.8 | Kopij 2018 |

| Walvis Bay, W Namibia | 260 ha | 2016/17 | 4.4 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 18.7 | Kopij 2023b |

| Opuwo, NW Namibia | 85 p. | 2020 | - | 57.6 | - | 9.0 | Kopij 2022b |

| Namibia, 3 towns, semidesert | 59 p. | 2018-20 | - | 13.6 | - | 13.6 | Kopij 2022b |

| Outapi, N Namibia | 130 ha | 2017 | 19.2 | 48.4 | 1.5 | 3.9 | Kopij 2019 |

| Ongwediva, N Namibia | 100 ha | 2018 | 36.4 | 48.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Kopij 2021b |

| Tsumeb, NE Namibia | 190 p. | 2017 | - | 4.7 | - | 0.0 | Kopij 2021c |

| Grootfontein, NE Namibia | 276 p. | 2014 | - | 1.8 | - | 2.5 | Kopij 2021a |

| Rundu, NE Namibia | 90 p. | 2015 | - | 0.0 | - | 8.9 | Kopij 2021a |

| Katima Mulilo, NE Namibia | 214 ha | 2014/15 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 10.1 | Kopij 2019 |

| Katima Mulilo, NE Namibia | 177 ha | 2013 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.4 | Kopij 2020 |

| Katima Mulilo, NE Namibia | 85 ha | 2015 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.4 | 15.8 | Kopij 2020 |

| Kasane, NE Botswana | 160 ha | 2014/16 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Kopij 2018b |

|

Taxonomic rank |

Established | Not stablished | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Galliformes | 8 | 16.3 | 11 | 10.9 | 19 | 12.7 |

| Phasianidae | 7 | 14.3 | 10 | 9.9 | 17 | 11.3 |

| Odontophoridae | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Numidae | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Anseriformes | 4 | 8.2 | 13 | 12.9 | 17 | 11.3 |

| Anatidae | 4 | 8.2 | 13 | 12.9 | 17 | 11.3 |

| Ciconiiformes | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Threskiornitidae | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Ardeidae | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Falconiformes | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Falconidae | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Gruiformes | 1 | 2.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 4 | 2.7 |

| Rallidae | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Turnicidae | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Columbiformes | 6 | 12.2 | 5 | 5.0 | 11 | 7.3 |

| Columbidae | 6 | 12.2 | 5 | 5.0 | 11 | 7.3 |

| Musophagiformes | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Musophagidae | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Coraciformes | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Coracidae | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Psittaciformes | 9 | 18.4 | 41 | 40.6 | 50 | 33.3 |

| Psittacidae | 1 | 2.0 | 20 | 19.8 | 21 | 14.0 |

| Psittaculidae | 7 | 14.3 | 17 | 16.8 | 24 | 16.0 |

| Cacatuidae | 1 | 2.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 4 | 2.7 |

| Psittrichasidae | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Strigiformes | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Tytonidae | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Passeriformes | 20 | 40.8 | 24 | 23.8 | 44 | 29.3 |

| Alaudidae | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Corvidae | 1 | 2.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Pycnonotidae | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Turdidae | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Sturnidae | 2 | 4.1 | 3 | 3.0 | 5 | 3.3 |

| Passeridae | 2 | 4.1 | 1 | 1.0 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Ploceidae | 4 | 8.2 | 4 | 4.0 | 8 | 5.3 |

| Viduidae | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Estrildidae | 5 | 10.2 | 4 | 4.0 | 9 | 6.0 |

| Fringillidae | 4 | 8.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.7 |

| Leiothrichidae | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Thraupidae | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Total | 49 | 100.0 | 101 | 100.0 | 150 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).