Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Immunotherapy and HCC

2. Microbiota and Immunotherapy Efficacy

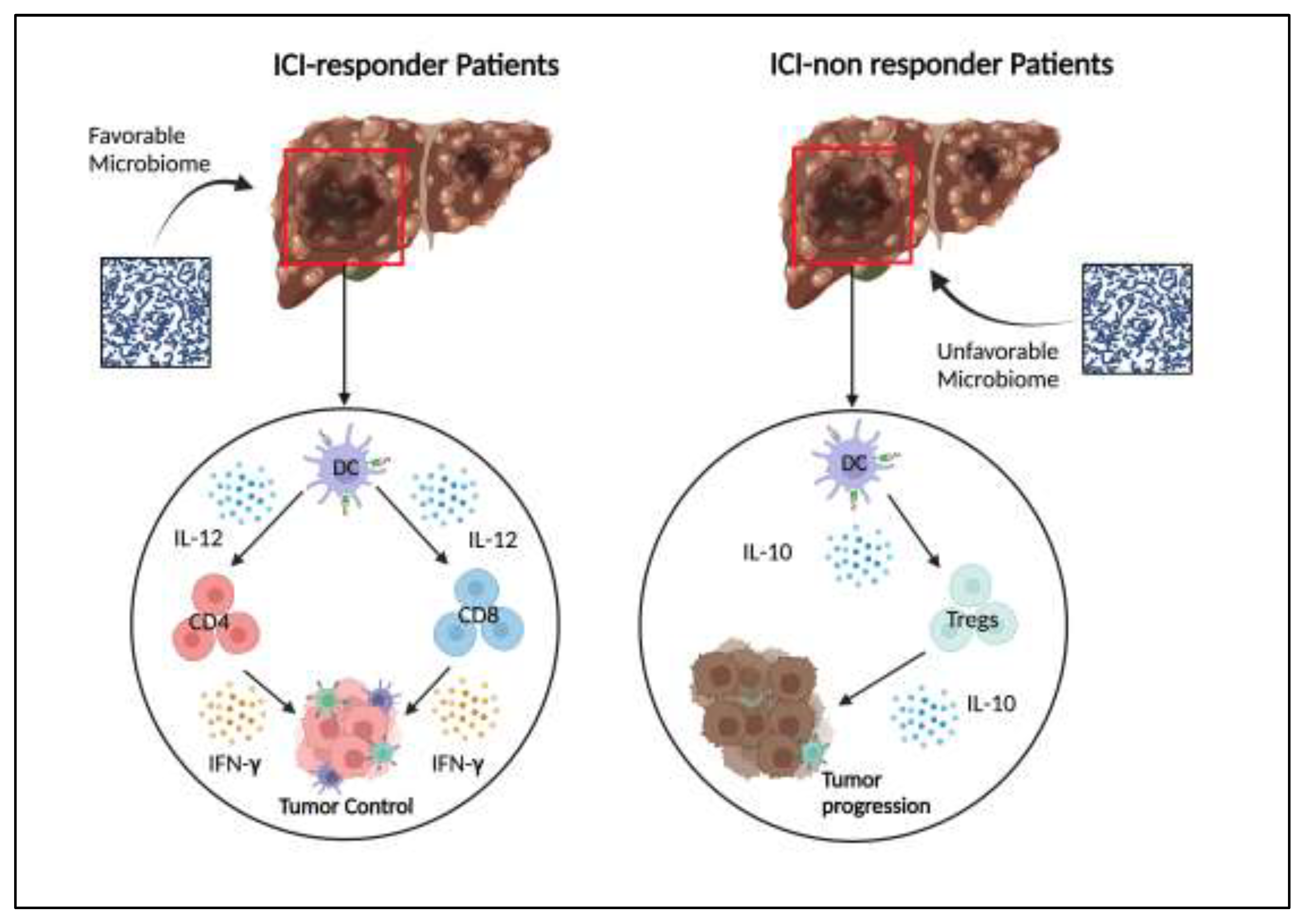

3. Microbiome: ICI-Responders and Non-Responders

4. Future Perspective and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Laface, C.; Memeo, R. Clinical Updates for Gastrointestinal Malignancies. J Pers Med 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laface, C.; Ranieri, G.; Maselli, F.M.; Ambrogio, F.; Foti, C.; Ammendola, M.; Laterza, M.; Cazzato, G.; Memeo, R.; Mastrandrea, G.; et al. Immunotherapy and the Combination with Targeted Therapies for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laface, C.; Fedele, P.; Maselli, F.M.; Ambrogio, F.; Foti, C.; Molinari, P.; Ammendola, M.; Lioce, M.; Ranieri, G. Targeted Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Old and New Opportunities. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laface, C.; Laforgia, M.; Molinari, P.; Ugenti, I.; Gadaleta, C.D.; Porta, C.; Ranieri, G. Hepatic Arterial Infusion of Chemotherapy for Advanced Hepatobiliary Cancers: State of the Art. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, G.; Laface, C. Loco-Regional and Systemic Chemotherapies for Hepato-Pancreatic Tumors: Integrated Treatments. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi-Farsi, N.; Bostanian, F.; Shahbazi, T.; Shamsinejad, F.S.; Bolideei, M.; Mohseni, P.; Zangooie, A.; Boustani, F.; Shoorei, H. Novel Oncogenes and Tumor Suppressor Genes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Carcinogenesis, Progression, and Therapeutic Targets. Gene 2025, 941, 149229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, T.; Liu, K.; Chilambe, L.O.; Khare, S. NAFLD and NAFLD Related HCC: Emerging Treatments and Clinical Trials. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temraz, S.; Nassar, F.; Kreidieh, F.; Mukherji, D.; Shamseddine, A.; Nasr, R. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy and the Potential Influence of Gut Microbiome. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Ye, J.; Liu, M. Characterization of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma Received Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Chinese Population-Based Study. Medicine 2020, 99, E21788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Guo, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, M.; Sang, L.; Chang, B.; Wang, B. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: How the Gut Microbiota Contributes to Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanu, D.; Pretta, A.; Lai, E.; Persano, M.; Donisi, C.; Mariani, S.; Dubois, M.; Migliari, M.; Saba, G.; Ziranu, P.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Microbiota: Implications for Clinical Management and Treatment. World J Hepatol 2022, 14, 1319–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Khatiwada, S.; Behary, J.; Kim, R.; Zekry, A. Modulation of the Gut Microbiome to Improve Clinical Outcomes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shui, L.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Yi, C.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, H. Gut Microbiome as a Potential Factor for Modulating Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.; Boyle, F.; Pavlakis, N.; Clarke, S.; Eade, T.; Hruby, G.; Lamoury, G.; Carroll, S.; Morgia, M.; Kneebone, A.; et al. The Gut Microbiome and Cancer Immunotherapy: Can We Use the Gut Microbiome as a Predictive Biomarker for Clinical Response in Cancer Immunotherapy? Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, Á.; Kelley, R.K.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Salem, R.; et al. BCLC Strategy for Prognosis Prediction and Treatment Recommendation: The 2022 Update. J Hepatol 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, G.; Laface, C.; Fazio, V.; Ceglia, D. De; MacIna, F.; Gisone, V.; Porcelli, M.; Vinciarelli, G.; Carella, C.; Molinari, P.; et al. Local Treatment with Deep Percutaneous Electrochemotherapy of Different Tumor Lesions: Pain Relief and Objective Response Results from an Observational Study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 7764–7775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Ricci, S.; Mazzaferro, V.; Hilgard, P.; Gane, E.; Blanc, J.-F.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Santoro, A.; Raoul, J.-L.; Forner, A.; et al. Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2008, 359, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Han, K.H.; Ikeda, K.; Piscaglia, F.; Baron, A.; Park, J.W.; Han, G.; Jassem, J.; et al. Lenvatinib versus Sorafenib in First-Line Treatment of Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Randomised Phase 3 Non-Inferiority Trial. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, G.; Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Jin, F.; Yang, H.; Han, B.; Zhou, R.; Chen, C.; Chen, L.; et al. The REACH Trial: A Randomized Controlled Trial Assessing the Safety and Effectiveness of the Spiration® Valve System in the Treatment of Severe Emphysema. Respiration 2018, 97, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Meyer, T.; Cheng, A.-L.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Rimassa, L.; Ryoo, B.-Y.; Cicin, I.; Merle, P.; Chen, Y.; Park, J.-W.; et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabrizian, P.; Abdelrahim, M.; Schwartz, M. Immunotherapy and Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatol 2024, 80, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkus, U.; Wankell, M.; Palamuthusingam, P.; McFarlane, C.; Hebbard, L. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in HCC: Cellular, Molecular and Systemic Data. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 86, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A.L.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Lim, H.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; et al. Updated Efficacy and Safety Data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab vs. Sorafenib for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatol 2022, 76, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangro, B.; Chan, S.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Lau, G.; Kudo, M.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Yarchoan, M.; De Toni, E.N.; Furuse, J.; Kang, Y.K.; et al. Four-Year Overall Survival Update from the Phase III HIMALAYA Study of Tremelimumab plus Durvalumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2024, 35, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, P.R.; Decaens, T.; Kudo, M.; Qin, S.; Fonseca, L.; Sangro, B.; Karachiwala, H.; Park, J.-W.; Gane, E.; Pinter, M.; et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) plus Ipilimumab (IPI) vs Lenvatinib (LEN) or Sorafenib (SOR) as First-Line Treatment for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (UHCC): First Results from CheckMate 9DW. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42, LBA4008–LBA4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Xu, J.; Bai, Y.; Xu, A.; Cang, S.; Du, C.; Li, Q.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. Sintilimab plus a Bevacizumab Biosimilar (IBI305) versus Sorafenib in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (ORIENT-32): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 2-3 Study. Lancet Oncol 2021, 22, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Kudo, M.; Merle, P.; Meyer, T.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Xu, R.; Edeline, J.; Ryoo, B.Y.; Ren, Z.; et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab versus Lenvatinib plus Placebo for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (LEAP-002): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol 2023, 24, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, R.K.; Rimassa, L.; Cheng, A.L.; Kaseb, A.; Qin, S.; Zhu, A.X.; Chan, S.L.; Melkadze, T.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Breder, V.; et al. Cabozantinib plus Atezolizumab versus Sorafenib for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (COSMIC-312): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol 2022, 23, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Park, J.W.; Finn, R.S.; Cheng, A.L.; Mathurin, P.; Edeline, J.; Kudo, M.; Harding, J.J.; Merle, P.; Rosmorduc, O.; et al. Nivolumab versus Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma (CheckMate 459): A Randomised, Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol 2022, 23, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Ryoo, B.Y.; Merle, P.; Kudo, M.; Bouattour, M.; Lim, H.Y.; Breder, V.; Edeline, J.; Chao, Y.; Ogasawara, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab As Second-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human Gut Microbiota/Microbiome in Health and Diseases: A Review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 2019–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, C.; Duranti, S.; Bottacini, F.; Casey, E.; Turroni, F.; Mahony, J.; Belzer, C.; Delgado Palacio, S.; Arboleya Montes, S.; Mancabelli, L.; et al. The First Microbial Colonizers of the Human Gut: Composition, Activities, and Health Implications of the Infant Gut Microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2017, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, I.E.K.; Yao, Y.; Ng, M.T.T.; Kim, J.E. Influence of Dietary Protein and Fiber Intake Interactions on the Human Gut Microbiota Composition and Function: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, N.; Su, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, R. Gut-Microbiota-Derived Metabolites Maintain Gut and Systemic Immune Homeostasis. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeler, M.; Caesar, R. Dietary Lipids, Gut Microbiota and Lipid Metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2019, 20, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An Insight into Gut Microbiota and Its Functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góralczyk-Bińkowska, A.; Szmajda-Krygier, D.; Kozłowska, E. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Psychiatric Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T. V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut Microbiome Modulates Response to Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Melanoma Patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant Promotes Response in Immunotherapy-Refractory Melanoma Patients. Science 2021, 371, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davar, D.; Dzutsev, A.K.; McCulloch, J.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Chauvin, J.M.; Morrison, R.M.; Deblasio, R.N.; Menna, C.; Ding, Q.; Pagliano, O.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant Overcomes Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Melanoma Patients. Science 2021, 371, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut Microbiome Influences Efficacy of PD-1-Based Immunotherapy against Epithelial Tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vétizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillère, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.M.; et al. Anticancer Immunotherapy by CTLA-4 Blockade Relies on the Gut Microbiota. Science 2015, 350, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, M.; Lunceford, J.; Nebozhyn, M.; Murphy, E.; Loboda, A.; Kaufman, D.R.; Albright, A.; Cheng, J.D.; Kang, S.P.; Shankaran, V.; et al. IFN-γ-Related MRNA Profile Predicts Clinical Response to PD-1 Blockade. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 2930–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Lei, Y.M.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.L.; et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium Promotes Antitumor Immunity and Facilitates Anti-PD-L1 Efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoue, T.; Morita, S.; Plichta, D.R.; Skelly, A.N.; Suda, W.; Sugiura, Y.; Narushima, S.; Vlamakis, H.; Motoo, I.; Sugita, K.; et al. A Defined Commensal Consortium Elicits CD8 T Cells and Anti-Cancer Immunity. Nature 2019, 565, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, D.; Long, J.; Yang, X.; Lin, J.; Song, Y.; Xie, F.; Xun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiome Is Associated with the Clinical Response to Anti-PD-1 Based Immunotherapy in Hepatobiliary Cancers. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R.; et al. Gut Microbiome Affects the Response to Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H.; Zitvogel, L.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Kroemer, G. The Immune Contexture in Cancer Prognosis and Treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017, 14, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, M.; Nagatomo, R.; Doi, K.; Shimizu, J.; Baba, K.; Saito, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Inoue, K.; Muto, M. Association of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut Microbiome With Clinical Response to Treatment With Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab in Patients With Solid Cancer Tumors. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e202895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, M.; Riester, Z.; Baldrich, A.; Reichardt, N.; Yuille, S.; Busetti, A.; Klein, M.; Wempe, A.; Leister, H.; Raifer, H.; et al. Microbial Short-Chain Fatty Acids Modulate CD8+ T Cell Responses and Improve Adoptive Immunotherapy for Cancer. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Wan, W.H.; Lu, J.; Kong, D.; Jin, Y.; You, W.; Sun, H.; Mu, X.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Regulate Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells in HCC. Hepatology 2023, 77, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, L.F.; Burkhard, R.; Pett, N.; Cooke, N.C.A.; Brown, K.; Ramay, H.; Paik, S.; Stagg, J.; Groves, R.A.; Gallo, M.; et al. Microbiome-Derived Inosine Modulates Response to Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy. Science 2020, 369, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behary, J.; Amorim, N.; Jiang, X.T.; Raposo, A.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Chu, F.; Stephens, C.; Jebeili, H.; et al. Gut Microbiota Impact on the Peripheral Immune Response in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuzak, J.; Dillon, S.; Wilson, C. Differential Interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-23 Production by Human Blood Monocytes and Dendritic Cells in Response to Commensal Enteric Bacteria. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012, 19, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurje, I.; Hammerich, L.; Tacke, F. Dendritic Cell and T Cell Crosstalk in Liver Fibrogenesis and Hepatocarcinogenesis: Implications for Prevention and Therapy of Liver Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, K.; Tahara, S.M. Immunotherapy and Microbiota for Targeting of Liver Tumor-Initiating Stem-like Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-C.; Lee, P.-C.; Kuo, Y.-L.; Wu, W.-K.; Chen, C.-C.; Lei, C.-H.; Yeh, C.-P.; Hsu, C.; Hsu, C.-H.; Lin, Z.-Z.; et al. An Exploratory Study for the Association of Gut Microbiome with Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2021, 8, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, A.; D’Alessio, A.; Enica, A.; Talbot, T.; Fulgenzi, C.A.M.; Nteliopoulos, G.; Goldin, R.D.; Cortellini, A.; Pinato, D.J. Predictive Biomarkers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2022, 22, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gok Yavuz, B.; Hasanov, E.; Lee, S.S.; Mohamed, Y.I.; Curran, M.A.; Koay, E.J.; Cristini, V.; Kaseb, A.O. Current Landscape and Future Directions of Biomarkers for Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2021, 8, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, F.; Colquhoun, S.D.; Wan, Y.J.Y. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy: The Impact of Epigenetic Drugs and the Gut Microbiome. Liver Res 2020, 4, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Chan, S.L.; Kudo, M.; Lau, G.; Kelley, R.K.; Furuse, J.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Kang, Y.-K.; Dao, T. V.; Toni, E.N. De; et al. Phase 3 Randomized, Open-Label, Multicenter Study of Tremelimumab (T) and Durvalumab (D) as First-Line Therapy in Patients (Pts) with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (UHCC): HIMALAYA. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 40, 379–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.W.; Kim, M.J.; Won, E.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Yun, Y.W.; Cho, S.B.; Joo, Y.E.; Hwang, J.E.; Bae, W.K.; Chung, I.J.; et al. Gut Microbiome Composition Can Predict the Response to Nivolumab in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. World J Gastroenterol 2021, 27, 7340–7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannone, G.; Ghisoni, E.; Genta, S.; Scotto, G.; Tuninetti, V.; Turinetto, M.; Valabrega, G. Immuno-Metabolism and Microenvironment in Cancer: Key Players for Immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinato, D.J.; Li, X.; Mishra-Kalyani, P.; D’Alessio, A.; Fulgenzi, C.A.M.; Scheiner, B.; Pinter, M.; Wei, G.; Schneider, J.; Rivera, D.R.; et al. Association between Antibiotics and Adverse Oncological Outcomes in Patients Receiving Targeted or Immune-Based Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JHEP Rep 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F.R.; Nicoletti, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Pompili, M. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Potential of the Gut Microbiota in Patients with Early Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforgia, M.; Calabrò, C.; Scattone, A.; Laface, C.; Porcelli, M.; Gadaleta, C.D.; Nardulli, P.; Ranieri, G. Pharmacotherapy in Mast Cell Leukemia. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2020, 21, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CLINICAL TRIAL | TREATMENT | Setting | RESULTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMbrave 150 | Atezolizumab+Bevacizumab vs Sorafenib |

First-line | mOS: 19.2 vs 13.4 months mPFS: 6.8 vs 4.3 months ORR: 23.7% vs 11.9% |

| HIMALAYA | Durvalumab+Tremelimumab vs Sorafenib |

First-line | mOS: 16.4 vs 13.7 months mPFS: 3.78 vs 4.07 months ORR: 20.1% vs 2.1 % |

| CheckMate-9DW | Nivolumab+Ipilimumab vs Sorafenib or Lenvatinib |

First-line | mOS. 23.7 vs 20.6 months mPFS: 9.1 vs 9.2 months ORR: 36% vs 13% |

| Orient-32 | Sintilimab+IBI205 vs Sorafenib | First-line | mOS: Not reached vs 10.4 months mPFS: 4.6 vs 2.8 months |

| COSMIC-312 | Atezolizumab+Cabozantinib vs Sorafenib |

First-line | mOS: 16.5 vs 15.5 mPFS: 6.9 vs 4.3 |

| LEAP-002 | Pembrolizumab+Lenvatinib vs Lenvatinib |

First-line | mOS: 21.2 vs 19 months mPFS: 8.2 vs 8 months ORR: 26.3% vs 17.5% |

| CheckMate-459 | Nivolumab vs Sorafenib | First-line | mOS: 16.4 vs 14.7 months mPFS: 3.7 vs 3.8 months ORR: 15% vs 7% |

| Keynote-240 | Pembrolizumab vs Placebo | Second-line | mOS: 13.9 Vs 10.6 months mPFS: 3 vs 2.8 months ORR: 27.3 vs 11.9% |

| RESPONDERS | NON-RESPONDERS |

|---|---|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).