Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Mice genes can be easily manipulated [18].

- This animal model is miniature-sized and can be handled easily [23].

- Mouse models are easily affordable [23].

- Immune responses to Plasmodium infection in murine models is widely used to understand that in human Plasmodium infection owing to their well-defined immune system [20].

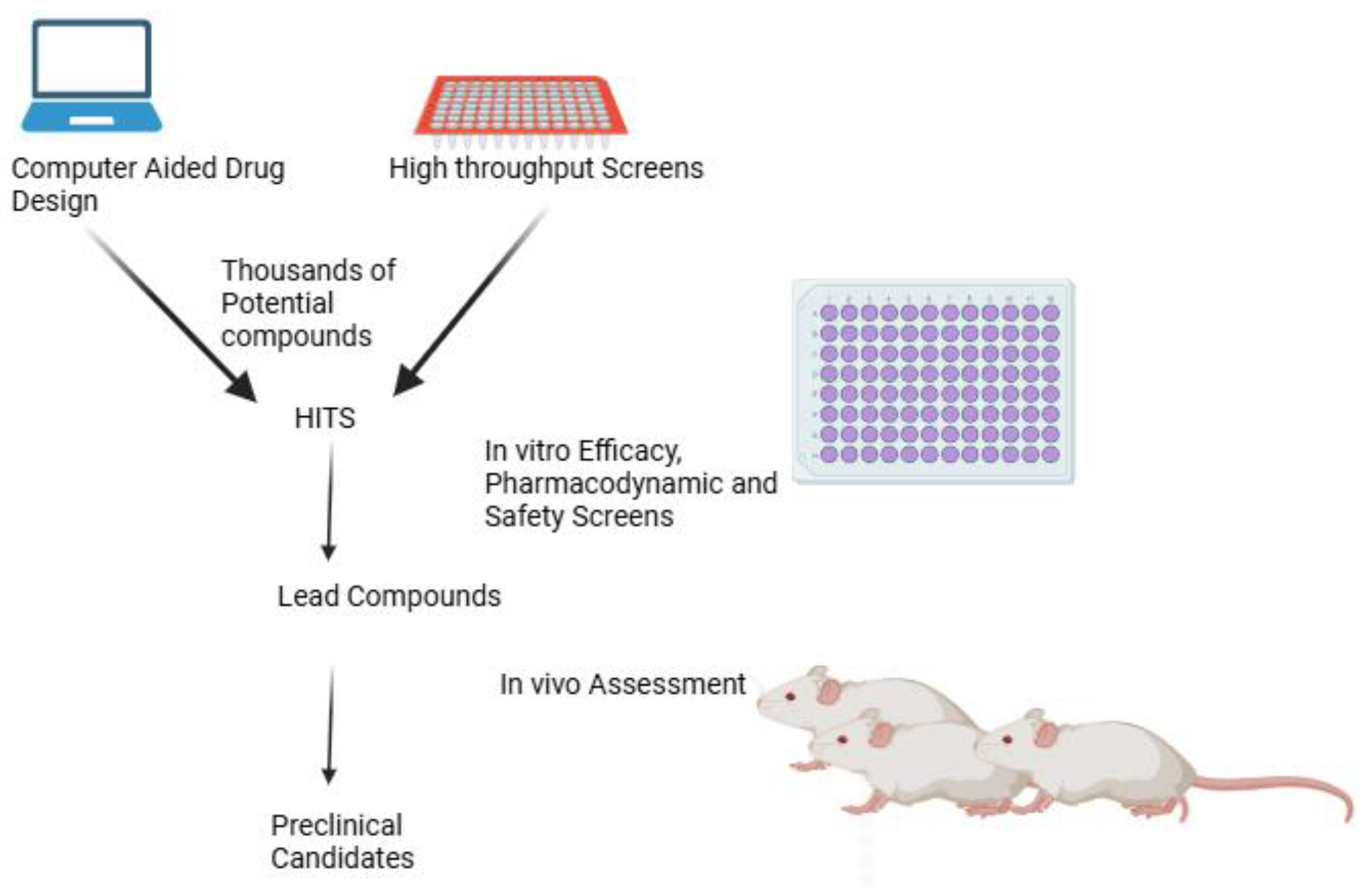

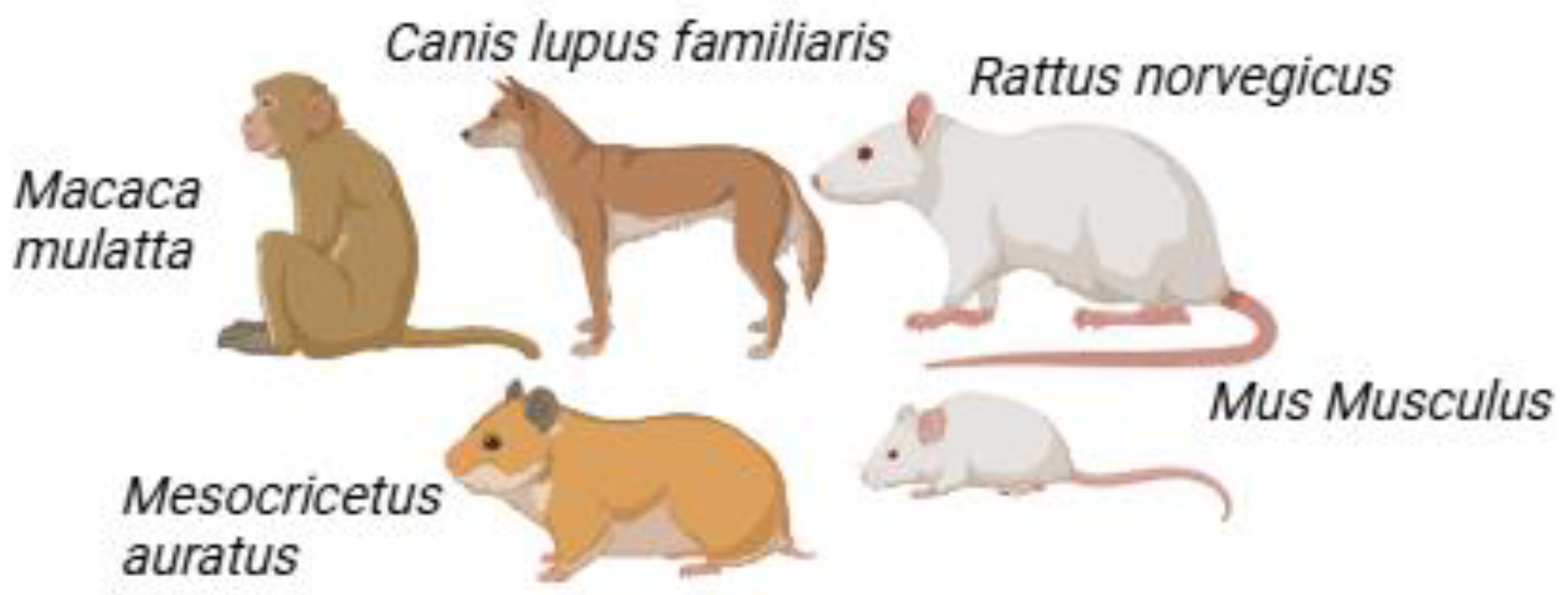

2. Current Murine Models Used in Antimalarial Drug Discovery

2.1. Inbred Mice

2.2. Outbred Mice

2.3. Humanized Mice

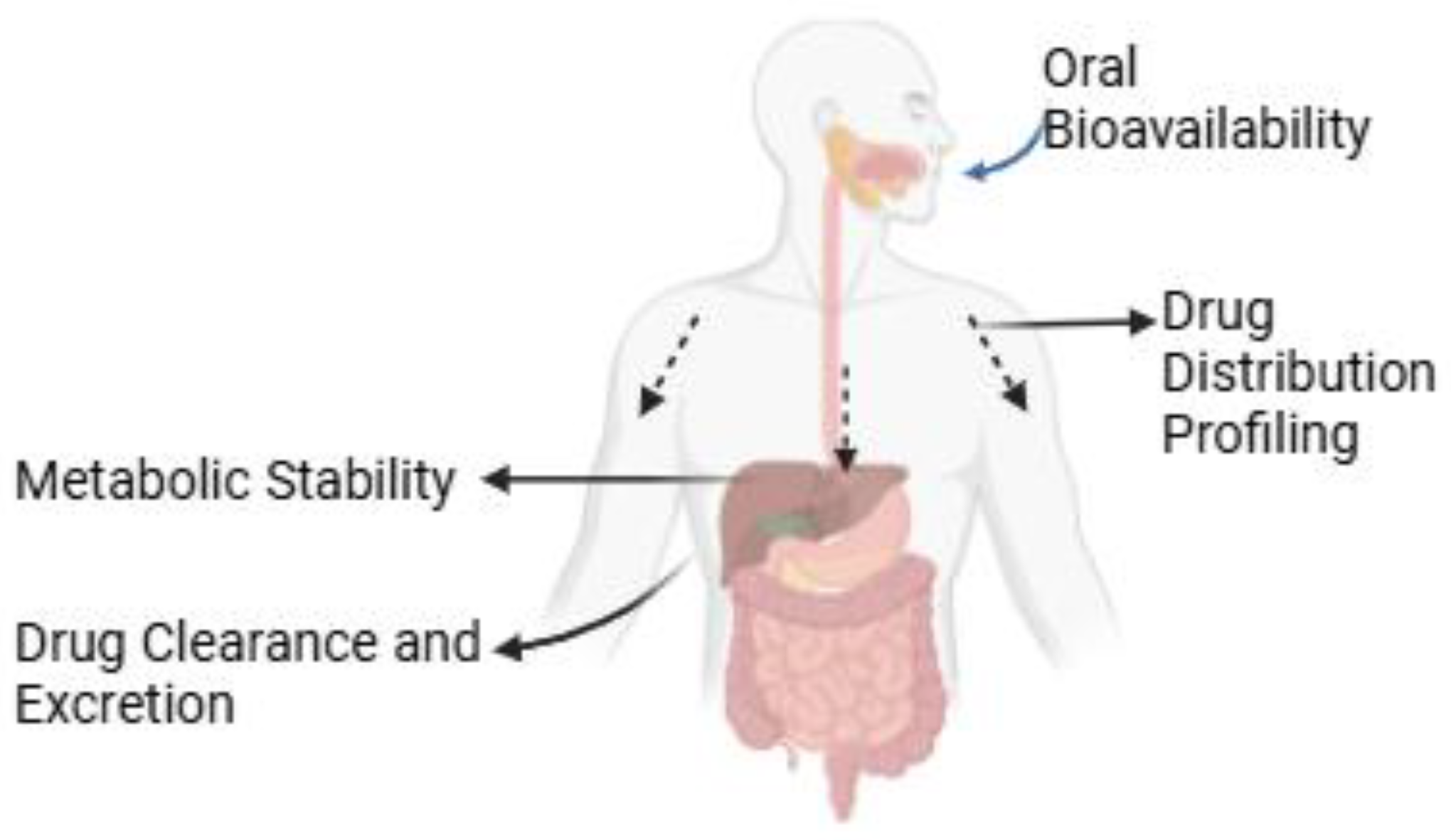

3. In Vivo Pharmacokinetic (PK) Studies

3.1. Oral Bioavailability

3.2. Drug Distribution Profiling

3.3. Metabolic Stability

3.4. Drug Clearance and Excretion

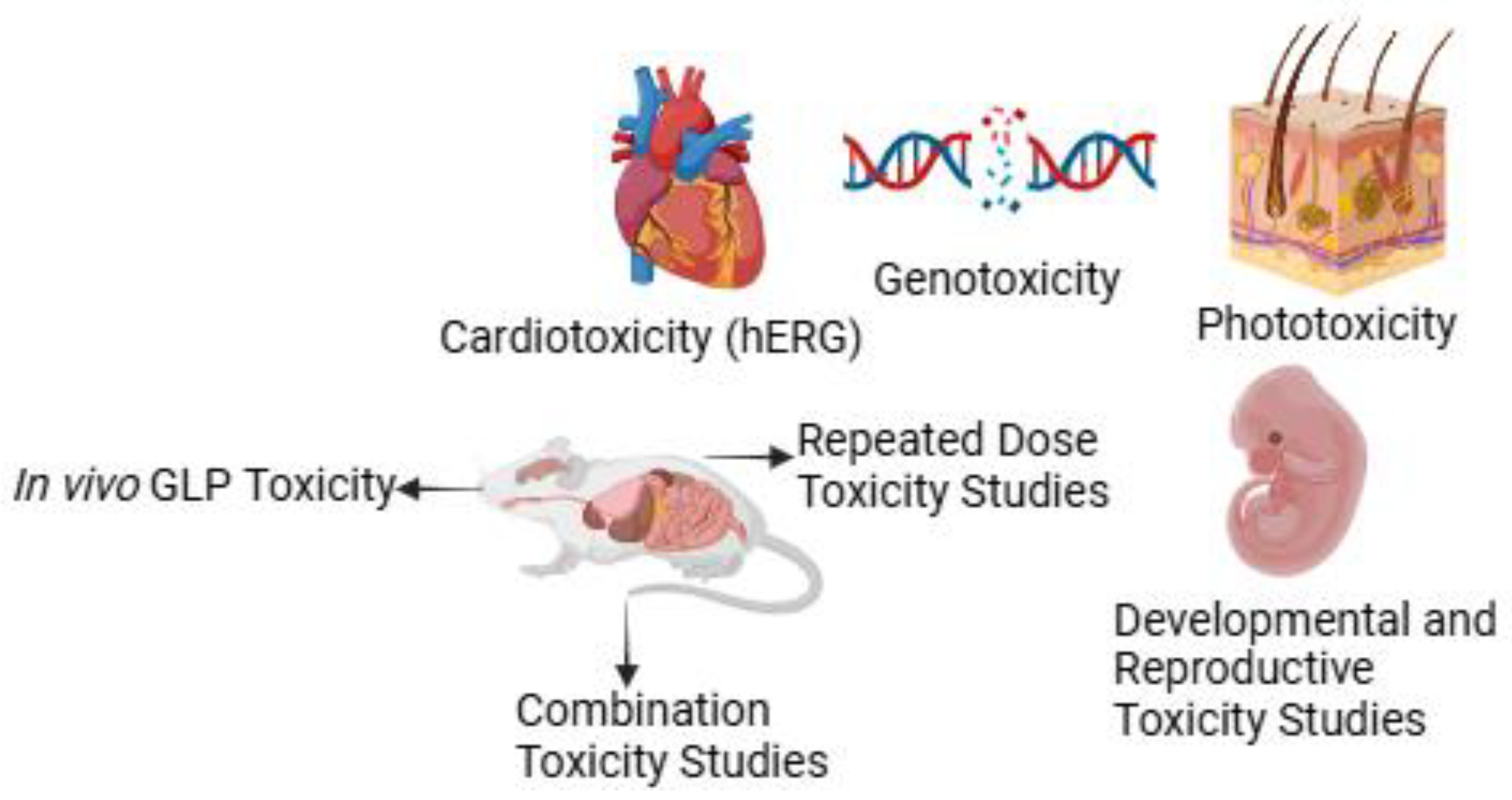

4. In Vivo Safety Studies

4.1. Cardiotoxicity (hERG)

4.2. Genotoxicity

4.3. Phototoxicity

4.4. Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) Toxicology Studies

4.5. Combination-Toxicity Studies

4.6. Repeated Dose Toxicity

4.7. Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity Testing

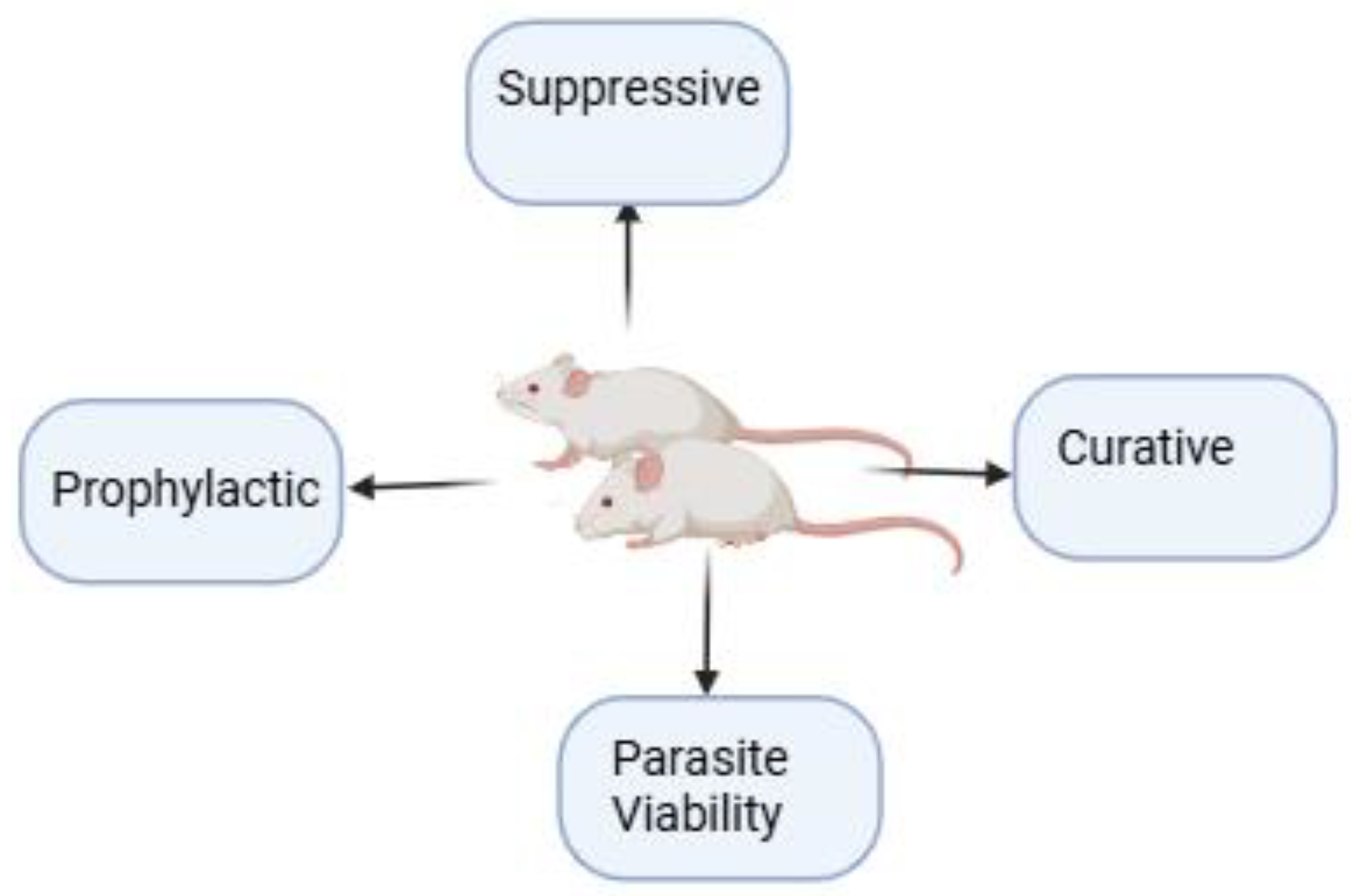

5. In Vivo Rodent Efficacy Studies

5.1. Prophylactic Test

5.2. Suppressive Test

5.3. Curative Test

5.4. Parasite Viability

| Murine Model | Area of Malaria Research | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Theiler’s Original (TO) | Drug resistance mechanisms | [24] |

| Humanized | Liver and Blood Stage Malaria Pathogenesis | [24,189] |

| C57BL/6 | Kinetics of the Infection and Disease Progression in mice compared to humans | [190] |

| C57BL/6 | Malaria-induced kidney impairment | [191] |

| C57Bl/6 | Vaccine Development | [192,193] |

| CBA | Lipidome Profile Assessment in Cerebral Malaria | [194] |

| ICR based | Understanding metabolic responses from immune perturbations through liver transcriptomics | [195] |

| C57BL/6 | Alterations in Cardician of parasite development and the resulting effect in cerebral malaria | [196] |

| C57BL/6 | Understanding malaria infection during pregnancy and the consequential birth effects | [197,198] |

| BALB/c | Vaccine Development against Malaria Relapse | [199] |

| C57BL/6 | Malaria Pathogenesis and Associated Lung Impairment | [200,201,202] |

| BPH/2 (transgenic) | The possibility of association between Malaria and Hypertension | [203] |

| BALB/c/C57BL/6 | Understanding the difference in metabolic responses between Uncomplicated and severe malaria | [204] |

| C57BL/6 | Immunity and Malaria infection | [205] |

| BALB/c/C57BL/6 | Environmental temperature and its association with malaria disease progression | [206] |

| C57BL/6 | Neonatal Immune response in malaria pathogenesis | [207,208] |

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAG | Albumin and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein |

| BALB/c | Bagg Albino |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| GLP | Good Laboratory Practice |

| hERG | human ether-ago-go related gene |

| HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry |

| ICR | Institute of Cancer Research |

| PPB | Plasma protein binding |

| PK | Pharmacokinetic |

| RDT | - Repeat dose toxicology |

| TO | Theiler’s Original |

| Vd | Volume of distribution |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Lindblade, K.A.; Li Xiao, H.; Tiffany, A.; Galappaththy, G.; Alonso, P.; Abeyasinghe, R.; Akpaka, K.; Aragon-Lopez, M.A.; Baba, E.S.; Bahena, A.; et al. Supporting Countries to Achieve Their Malaria Elimination Goals: The WHO E-2020 Initiative. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemingway, J.; Shretta, R.; Wells, T.N.C.; Bell, D.; Djimdé, A.A.; Achee, N.; Qi, G. Tools and Strategies for Malaria Control and Elimination: What Do We Need to Achieve a Grand Convergence in Malaria? PLOS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.K.; Anand, U.; Siddiqui, W.A.; Tripathi, R. Drug Development Strategies for Malaria: With the Hope for New Antimalarial Drug Discovery—An Update. Adv. Med. 2023, 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhameliya, T.M.; Kathuria, D.; Patel, T.M.; Dave, B.P.; Chaudhari, A.Z.; Vekariya, D.D. A Quinquennial Review on Recent Advancements and Developments in Search of Anti-Malarial Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 753–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira-Neto, J.L.; Wicht, K.J.; Chibale, K.; Burrows, J.N.; Fidock, D.A.; Winzeler, E.A. Antimalarial Drug Discovery: Progress and Approaches. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira-Neto, J.L.; Wicht, K.J.; Chibale, K.; Burrows, J.N.; Fidock, D.A.; Winzeler, E.A. Antimalarial Drug Discovery: Progress and Approaches. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.P.; Rathi, B. Editorial: Advances in Anti-Malarial Drug Discovery. Front. Drug Discov. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.P.S.; Manjunatha, U.H.; Mikolajczak, S.; Ashigbie, P.G.; Diagana, T.T. Drug Discovery for Parasitic Diseases: Powered by Technology, Enabled by Pharmacology, Informed by Clinical Science. Trends Parasitol. 2023, 39, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ncube, N.B.; Tukulula, M.; Govender, K.G. Leveraging Computational Tools to Combat Malaria: Assessment and Development of New Therapeutics. J. Cheminform. 2024, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akash, S.; Abdelkrim, G.; Bayil, I.; Hosen, M.E.; Mukerjee, N.; Shater, A.F.; Saleh, F.M.; Albadrani, G.M.; Al-Ghadi, M.Q.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; et al. Antimalarial Drug Discovery against Malaria Parasites through Haplopine Modification: An Advanced Computational Approach. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 3168–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duay, S.S.; Yap, R.C.Y.; Gaitano, A.L.; Santos, J.A.A.; Macalino, S.J.Y. Roles of Virtual Screening and Molecular Dynamics Simulations in Discovering and Understanding Antimalarial Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisnerat, C.; Dassonville-Klimpt, A.; Gosselet, F.; Sonnet, P. Antimalarial Drug Discovery: From Quinine to the Most Recent Promising Clinical Drug Candidates. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 3326–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, M.; Pešić, D.; Alihodžić, S.; Fajdetić, A.; Herreros, E.; Gamo, F.J.; Angulo-Barturen, I.; Jiménez-Díaz, M.B.; Ferrer-Bazaga, S.; Martínez, M.S.; et al. A Novel Class of Fast-acting Antimalarial Agents: Substituted 15-membered Azalides. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JIMÉNEZ-DÍAZ, M.B.; VIERA, S.; FERNÁNDEZ-ALVARO, E.; ANGULO-BARTUREN, I. Animal Models of Efficacy to Accelerate Drug Discovery in Malaria. Parasitology 2014, 141, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingber, D.E. Human Organs-on-Chips for Disease Modelling, Drug Development and Personalized Medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cauvin, A.J.; Peters, C.; Brennan, F. Advantages and Limitations of Commonly Used Nonhuman Primate Species in Research and Development of Biopharmaceuticals. In The Nonhuman Primate in Nonclinical Drug Development and Safety Assessment; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 379–395.

- Greenwood, B. Malaria — Obstacles and Opportunities. Parasitol. Today 1992, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Niz, M.; Heussler, V.T. Rodent Malaria Models: Insights into Human Disease and Parasite Biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 46, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuberi, A.; Lutz, C. Mouse Models for Drug Discovery. Can New Tools and Technology Improve Translational Power? ILAR J. 2016, 57, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olatunde, A.C.; Cornwall, D.H.; Roedel, M.; Lamb, T.J. Mouse Models for Unravelling Immunology of Blood Stage Malaria. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannery, E.L.; Foquet, L.; Chuenchob, V.; Fishbaugher, M.; Billman, Z.; Navarro, M.J.; Betz, W.; Olsen, T.M.; Lee, J.; Camargo, N.; et al. Assessing Drug Efficacy against Plasmodium Falciparum Liver Stages in Vivo. JCI Insight 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, A.J. A Primer for Research Scientists on Assessing Mouse Gross and Histopathology Images in the Biomedical Literature. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Seed, T.M. How Necessary Are Animal Models for Modern Drug Discovery? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simwela, N. V.; Waters, A.P. Current Status of Experimental Models for the Study of Malaria. Parasitology 2022, 149, 729–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaprasad, A.; Klaus, S.; Douvropoulou, O.; Culleton, R.; Pain, A. Plasmodium Vinckei Genomes Provide Insights into the Pan-Genome and Evolution of Rodent Malaria Parasites. BMC Biol. 2021, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.L.; White, K.L. Methods to Assess Immunotoxicity*. In Comprehensive Toxicology; Elsevier, 2010; pp. 567–590.

- Thakre, N.; Fernandes, P.; Mueller, A.-K.; Graw, F. Examining the Reticulocyte Preference of Two Plasmodium Berghei Strains during Blood-Stage Malaria Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, F.; Chen, X.; Xing, J. The Effect of Malaria-Induced Alteration of Metabolism on Piperaquine Disposition in Plasmodium Yoelii Infected Mice and Predicted in Malaria Patients. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Wu, J.; Pattaradilokrat, S.; Tumas, K.; He, X.; Peng, Y.; Huang, R.; Myers, T.G.; Long, C.A.; Wang, R.; et al. Detection of Host Pathways Universally Inhibited after Plasmodium Yoelii Infection for Immune Intervention. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longley, R.J.; Hill, A.V.S.; Spencer, A.J. Malaria Vaccines: Identifying Plasmodium Falciparum Liver-Stage Targets. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, N.; Parthiban, C.; Billman, Z.P.; Stone, B.C.; Watson, F.N.; Zhou, K.; Olsen, T.M.; Cruz Talavera, I.; Seilie, A.M.; Kalata, A.C.; et al. More Time to Kill: A Longer Liver Stage Increases T Cell-Mediated Protection against Pre-Erythrocytic Malaria. iScience 2023, 26, 108489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedegah, M.; Finkelman, F.; Hoffman, S.L. Interleukin 12 Induction of Interferon Gamma-Dependent Protection against Malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994, 91, 10700–10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conteh, S.; Kolasny, J.; Robbins, Y.L.; Pyana, P.; Büscher, P.; Musgrove, J.; Butler, B.; Lambert, L.; Gorres, J.P.; Duffy, P.E. Dynamics and Outcomes of Plasmodium Infections in Grammomys Surdaster (Grammomys Dolichurus) Thicket Rats versus Inbred Mice. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1893–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter, A.E.; Sudhakar, P.; Sandeep, B. V.; Rao, B.G.; Kalpana, V.L. Murine Models for Development of Anti-Infective Therapeutics. In Model Organisms for Microbial Pathogenesis, Biofilm Formation and Antimicrobial Drug Discovery; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; pp. 611–655. [Google Scholar]

- Olanlokun, J.O.; Abiodun, W.O.; Ebenezer, O.; Koorbanally, N.A.; Olorunsogo, O.O. Curcumin Modulates Multiple Cell Death, Matrix Metalloproteinase Activation and Cardiac Protein Release in Susceptible and Resistant Plasmodium Berghei-Infected Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comino Garcia-Munoz, A.; Varlet, I.; Grau, G.E.; Perles-Barbacaru, T.-A.; Viola, A. Contribution of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Studies to the Understanding of Cerebral Malaria Pathogenesis. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriboonvorakul, N.; Chotivanich, K.; Silachamroon, U.; Phumratanaprapin, W.; Adams, J.H.; Dondorp, A.M.; Leopold, S.J. Intestinal Injury and the Gut Microbiota in Patients with Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria. PLOS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaraj, C.; Ragavendran, C.; Kumar, R.C.S.; Ali, A.; Khan, S.U.; Mashwani, Z. ur-R.; Luna-Arias, J.P.; Pedroza, J.P.R. Antiparasitic Potential of Asteraceae Plants: A Comprehensive Review on Therapeutic and Mechanistic Aspects for Biocompatible Drug Discovery. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevagi, R.J.; Good, M.F.; Stanisic, D.I. Plasmodium Infection and Drug Cure for Malaria Vaccine Development. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H. BALB/c Mouse. In Brenner’s Encyclopedia of Genetics; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 290–292.

- Barr, J.T.; Tran, T.B.; Rock, B.M.; Wahlstrom, J.L.; Dahal, U.P. Strain-Dependent Variability of Early Discovery Small Molecule Pharmacokinetics in Mice: Does Strain Matter? Drug Metab. Dispos. 2020, 48, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimperman, C.K.; Pena, M.; Gokcek, S.M.; Theall, B.P.; Patel, M. V.; Sharma, A.; Qi, C.; Sturdevant, D.; Miller, L.H.; Collins, P.L.; et al. Cerebral Malaria Is Regulated by Host-Mediated Changes in Plasmodium Gene Expression. MBio 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubouy, A.; Camara, A.; Haddad, M. Medicinal Plants from West Africa Used as Antimalarial Agents: An Overview. In Medicinal Plants as Anti-Infectives; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 267–306.

- Hernandez-Valladares, M.; Rihet, P.; Iraqi, F.A. Host Susceptibility to Malaria in Human and Mice: Compatible Approaches to Identify Potential Resistant Genes. Physiol. Genomics 2014, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.M.; McMorran, B.J.; Foote, S.J.; Burgio, G. Host Genetics in Malaria: Lessons from Mouse Studies. Mamm. Genome 2018, 29, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Richter, N.; König, C.; Kremer, A.E.; Zimmermann, K. Generalized Resistance to Pruritogen-Induced Scratching in the C3H/HeJ Strain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vydyam, P.; Chand, M.; Gihaz, S.; Renard, I.; Heffernan, G.D.; Jacobus, L.R.; Jacobus, D.P.; Saionz, K.W.; Shah, R.; Shieh, H.-M.; et al. In Vitro Efficacy of Next-Generation Dihydrotriazines and Biguanides against Babesiosis and Malaria Parasites. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djokic, V.; Akoolo, L.; Parveen, N. Babesia Microti Infection Changes Host Spleen Architecture and Is Cleared by a Th1 Immune Response. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Wu, J.; Xu, F.; Pattaradilokrat, S. Genetic Mapping of Determinants in Drug Resistance, Virulence, Disease Susceptibility, and Interaction of Host-Rodent Malaria Parasites. Parasitol. Int. 2022, 91, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnider, C.B.; Yang, H.; Starrs, L.; Ehmann, A.; Rahimi, F.; Di Pierro, E.; Graziadei, G.; Matthews, K.; De Koning-Ward, T.; Bauer, D.C.; et al. Host Porphobilinogen Deaminase Deficiency Confers Malaria Resistance in Plasmodium Chabaudi but Not in Plasmodium Berghei or Plasmodium Falciparum During Intraerythrocytic Growth. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muqbil, I.; Philip, P.A.; Mohammad, R.M. A Guide to Tumor Assessment Methodologies in Cancer Drug Discovery. In Animal Models in Cancer Drug Discovery; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 233–248.

- Sunita, K.; Rajyalakshmi, M.; Kalyan Kumar, K.; Sowjanya, M.; Satish, P.V.V.; Madhu Prasad, D. Human Malaria in C57BL/6J Mice: An in Vivo Model for Chemotherapy Studies. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2014, 52, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, F.; Hammill, J.; Holbrook, G.; Yang, L.; Freeman, B.; White, K.L.; Shackleford, D.M.; O’Loughlin, K.G.; Charman, S.A.; et al. Selecting an Anti-Malarial Clinical Candidate from Two Potent Dihydroisoquinolones. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Woodward, J.J.; Lai, W.; Minie, M.; Sun, X.; Tanaka, L.; Snyder, J.M.; Sasaki, T.; Elkon, K.B. Inhibition of Cyclic <scp>GMP</Scp> - <scp>AMP</Scp> Synthase Using a Novel Antimalarial Drug Derivative in Trex1 -Deficient Mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujjari, L.; Kalani, H.; Pindiprolu, S.K.; Arakareddy, B.P.; Yadagiri, G. Current Challenges and Nanotechnology-Based Pharmaceutical Strategies for the Treatment and Control of Malaria. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.M.; Bram, J.T.; Sim, D.; Read, A.F. Effect of Drug Dose and Timing of Treatment on the Emergence of Drug Resistance in Vivo in a Malaria Model. Evol. Med. Public Heal. 2020, 2020, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunduri, A.; Watson, P.M.; Ashbrook, D.G. New Insights on Gene by Environmental Effects of Drugs of Abuse in Animal Models Using GeneNetwork. Genes (Basel). 2022, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novita, R.; Suprayogi, A.; Agusta, A.; Nugraha, A.; Nozaki, T.; Agustini, K.; Darusman, H. Antimalarial Activity of Borrelidin and Fumagilin in Plasmodium Berghei-Infected Mice. Open Vet. J. 2024, 14, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermanto, F.; Sutjiatmo, A.B.; Subarnas, A.; Haq, F.A.; Berbudi, A. The Combination of Apigenin and Ursolic Acid Reduces the Severity of Cerebral Malaria in Plasmodium Berghei ANKA-Infected Swiss Webster Mice. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annang, F.; Pérez-Moreno, G.; Díaz, C.; González-Menéndez, V.; de Pedro Montejo, N.; del Palacio, J.P.; Sánchez, P.; Tanghe, S.; Rodriguez, A.; Pérez-Victoria, I.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of Strasseriolides A–D, Potent Antiplasmodial Macrolides Isolated from Strasseria Geniculata CF-247,251. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, N.S.M.; Matsumori, H.; Dinh, T.Q.; Sato, A.; Miyoshi, S.-I.; Chang, K.-S.; Yu, H.S.; Kobayashi, F.; Kim, H.-S. Antimalarial Effect of Synthetic Endoperoxide on Synchronized Plasmodium Chabaudi Infected Mice. Parasites, Hosts Dis. 2023, 61, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounjaijean, S.; Romyasamit, C.; Somsak, V. Evaluation of Antimalarial Potential of Aqueous Crude Gymnema Inodorum Leaf Extract against Plasmodium Berghei Infection in Mice. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounjaijean, S.; Somsak, V. Exploring the Antimalarial Potential of Gnetum Gnemon Leaf Extract Against Plasmodium Berghei in Mice. J. Trop. Med. 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaniad, P.; Techarang, T.; Phuwajaroanpong, A.; Na-ek, P.; Viriyavejakul, P.; Punsawad, C. In Vivo Antimalarial Activity and Toxicity Study of Extracts of Tagetes Erecta L. and Synedrella Nodiflora (L.) Gaertn. from the Asteraceae Family. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klope, M.T.; Tapia Cardona, J.A.; Chen, J.; Gonciarz, R.L.; Cheng, K.; Jaishankar, P.; Kim, J.; Legac, J.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Renslo, A.R. Synthesis and In Vivo Profiling of Desymmetrized Antimalarial Trioxolanes with Diverse Carbamate Side Chains. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgert, L.; Rottmann, M.; Wittlin, S.; Gobeau, N.; Krause, A.; Dingemanse, J.; Möhrle, J.J.; Penny, M.A. Ensemble Modeling Highlights Importance of Understanding Parasite-Host Behavior in Preclinical Antimalarial Drug Development. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgert, L.; Zaloumis, S.; Dini, S.; Marquart, L.; Cao, P.; Cherkaoui, M.; Gobeau, N.; McCarthy, J.; Simpson, J.A.; Möhrle, J.J.; et al. Parasite-Host Dynamics throughout Antimalarial Drug Development Stages Complicate the Translation of Parasite Clearance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, A.; Arez, F.; Alves, P.M.; Badolo, L.; Brito, C.; Fischli, C.; Fontinha, D.; Oeuvray, C.; Prudêncio, M.; Rottmann, M.; et al. Translation of Liver Stage Activity of M5717, a Plasmodium Elongation Factor 2 Inhibitor: From Bench to Bedside. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, A.; Ferrer, E.; Arahuetes, S.; Eguiluz, C.; Rooijen, N. Van; Benito, A. The Course of Infections and Pathology in Immunomodulated NOD/LtSz-SCID Mice Inoculated with Plasmodium Falciparum Laboratory Lines and Clinical Isolates. Int. J. Parasitol. 2006, 36, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, M.A.; Antunez, C.; Nunez-Badinez, P.; De Leo, B.; Saunders, P.T.; Vincent, K.; Cano, A.; Nagel, J.; Gomez, R. Rodent Animal Models of Endometriosis-Associated Pain: Unmet Needs and Resources Available for Improving Translational Research in Endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-Castañón, V.H.; Juárez-Avelar, I.; Legorreta-Herrera, M.; Rodriguez-Sosa, M. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Contributes to Immunopathogenesis during Plasmodium Yoelii 17XL Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, C.R.; Smith, P.F.; Andes, D.; Andrews, K.; Derendorf, H.; Friberg, L.E.; Hanna, D.; Lepak, A.; Mills, E.; Polasek, T.M.; et al. Model-Informed Drug Development for Anti-Infectives: State of the Art and Future. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 867–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparici Herraiz, I.; Caires, H.R.; Castillo-Fernández, Ó.; Sima, N.; Méndez-Mora, L.; Risueño, R.M.; Sattabongkot, J.; Roobsoong, W.; Hernández-Machado, A.; Fernandez-Becerra, C.; et al. Advancing Key Gaps in the Knowledge of Plasmodium Vivax Cryptic Infections Using Humanized Mouse Models and Organs-on-Chips. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, P.M.; Amewu, R.K.; Charman, S.A.; Sabbani, S.; Gnädig, N.F.; Straimer, J.; Fidock, D.A.; Shore, E.R.; Roberts, N.L.; Wong, M.H.-L.; et al. A Tetraoxane-Based Antimalarial Drug Candidate That Overcomes PfK13-C580Y Dependent Artemisinin Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, D.; Kumar, S.; Betz, W.; Armstrong, J.M.; Haile, M.T.; Camargo, N.; Parthiban, C.; Seilie, A.M.; Murphy, S.C.; Vaughan, A.M.; et al. A Plasmodium Falciparum ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Is Essential for Liver Stage Entry into Schizogony. iScience 2022, 25, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oblak, A.L.; Lin, P.B.; Kotredes, K.P.; Pandey, R.S.; Garceau, D.; Williams, H.M.; Uyar, A.; O’Rourke, R.; O’Rourke, S.; Ingraham, C.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of the 5XFAD Mouse Model for Preclinical Testing Applications: A MODEL-AD Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioko, M.; Mwangi, S.; Njunge, J.M.; Berkley, J.A.; Bejon, P.; Abdi, A.I. Linking Cerebral Malaria Pathogenesis to APOE-Mediated Amyloidosis: Observations and Hypothesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisler, K.; Sagare, A.P.; Lazic, D.; Bazzi, S.; Lawson, E.; Hsu, C.-J.; Wang, Y.; Ramanathan, A.; Nelson, A.R.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Anti-Malaria Drug Artesunate Prevents Development of Amyloid-β Pathology in Mice by Upregulating PICALM at the Blood-Brain Barrier. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, Z.; Machado, M.; Lindeza, A.; do Rosário, V.; Gazarini, M.L.; Lopes, D. Treatment of Plasmodium Chabaudi Parasites with Curcumin in Combination with Antimalarial Drugs: Drug Interactions and Implications on the Ubiquitin/Proteasome System. J. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 2013, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha e Silva, L.F.; Nogueira, K.L.; Pinto, A.C. da S.; Katzin, A.M.; Sussmann, R.A.C.; Muniz, M.P.; Neto, V.F. de A.; Chaves, F.C.M.; Coutinho, J.P.; Lima, E.S.; et al. In Vivo Antimalarial Activity and Mechanisms of Action of 4-Nerolidylcatechol Derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 3271–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saroa, R.; Kaushik, D.; Rakha, A.; Bagai, U.; Kaur, S.; Salunke, D.B. Pure TLR 7 Agonistic BBIQ Is a Potential Adjuvant Against Plasmodium Berghei ANKA Challenge In Vivo . In Drug Development for Malaria; Wiley, 2022; pp. 353–366. In Drug Development for Malaria; Wiley, 2022; pp. 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Sonoiki, E.; Ng, C.L.; Lee, M.C.S.; Guo, D.; Zhang, Y.-K.; Zhou, Y.; Alley, M.R.K.; Ahyong, V.; Sanz, L.M.; Lafuente-Monasterio, M.J.; et al. A Potent Antimalarial Benzoxaborole Targets a Plasmodium Falciparum Cleavage and Polyadenylation Specificity Factor Homologue. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, K.T.; Dickson, T.M.; Lindner, S.E. Standard Selection Treatments with Sulfadiazine Limit Plasmodium Yoelii Host-to-Vector Transmission. mSphere 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, M.P.; Bhatia, B.; Assefa, H.; Honeyman, L.; Garrity-Ryan, L.K.; Verma, A.K.; Gut, J.; Larson, K.; Donatelli, J.; Macone, A.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Antimalarial Efficacies of Optimized Tetracyclines. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3131–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezewski, A.J.; Lin, Y.-H.; Reisz, J.A.; Culp-Hill, R.; Barekatain, Y.; Yan, V.C.; D’Alessandro, A.; Muller, F.L.; Odom John, A.R. Targeting Host Glycolysis as a Strategy for Antimalarial Development. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrelli, M.T.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Brotto, M. The Skeletal Muscles of Mice Infected with Plasmodium Berghei and Plasmodium Chabaudi Reveal a Crosstalk between Lipid Mediators and Gene Expression. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, Y.R.; Kang, Y.-J.; Lee, S.J. In Vivo Study on Splenomegaly Inhibition by Genistein in Plasmodium Berghei -Infected Mice. Parasitol. Int. 2015, 64, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaniad, P.; Techarang, T.; Phuwajaroanpong, A.; Plirat, W.; Viriyavejakul, P.; Septama, A.W.; Punsawad, C. Antimalarial Efficacy and Toxicological Assessment of Medicinal Plant Ingredients of Prabchompoothaweep Remedy as a Candidate for Antimalarial Drug Development. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, H.; Moon, K.; Trinh, T.-T.T.; Eom, T.-H.; Park, H.; Kim, H.S.; Yeo, S.-J. Evaluation of the Antimalarial Activity of SAM13-2HCl with Morpholine Amide (SKM13 Derivative) against Antimalarial Drug-Resistant Plasmodium Falciparum and Plasmodium Berghei Infected ICR Mice. Parasites, Hosts Dis. 2024, 62, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degotte, G.; Pendeville, H.; Di Chio, C.; Ettari, R.; Pirotte, B.; Frédérich, M.; Francotte, P. Dimeric Polyphenols to Pave the Way for New Antimalarial Drugs. RSC Med. Chem. 2023, 14, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeates, C.L.; Batchelor, J.F.; Capon, E.C.; Cheesman, N.J.; Fry, M.; Hudson, A.T.; Pudney, M.; Trimming, H.; Woolven, J.; Bueno, J.M.; et al. Synthesis and Structure–Activity Relationships of 4-Pyridones as Potential Antimalarials. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2845–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chughlay, M.F.; El Gaaloul, M.; Donini, C.; Campo, B.; Berghmans, P.-J.; Lucardie, A.; Marx, M.W.; Cherkaoui-Rbati, M.H.; Langdon, G.; Angulo-Barturen, I.; et al. Chemoprotective Antimalarial Activity of P218 against Plasmodium Falciparum: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Volunteer Infection Study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1348–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basilico, N.; Parapini, S.; D’Alessandro, S.; Misiano, P.; Romeo, S.; Dondio, G.; Yardley, V.; Vivas, L.; Nasser, S.; Rénia, L.; et al. Favorable Preclinical Pharmacological Profile of a Novel Antimalarial Pyrrolizidinylmethyl Derivative of 4-Amino-7-Chloroquinoline with Potent In Vitro and In Vivo Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrescu, I.; de Camargo, T.M.; Gimenez, A.M.; Murillo, O.; Amorim, K.N. da S.; Marinho, C.R.F.; Soares, I.S.; Boscardin, S.B.; Bargieri, D.Y. Protective Immunity in Mice Immunized With P. Vivax MSP119-Based Formulations and Challenged With P. Berghei Expressing PvMSP119. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, K.A.; Wesche, D.; McCarthy, J.; Möhrle, J.J.; Tarning, J.; Phillips, L.; Kern, S.; Grasela, T. Model-Informed Drug Development for Malaria Therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 58, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Ottilie, S.; Istvan, E.S.; Godinez-Macias, K.P.; Lukens, A.K.; Baragaña, B.; Campo, B.; Walpole, C.; Niles, J.C.; Chibale, K.; et al. MalDA, Accelerating Malaria Drug Discovery. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancucci, N.M.B.; Gumpp, C.; van Gemert, G.-J.; Yu, X.; Passecker, A.; Nardella, F.; Thommen, B.T.; Chambon, M.; Turcatti, G.; Halby, L.; et al. An All-in-One Pipeline for the in Vitro Discovery and in Vivo Testing of Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria Transmission Blocking Drugs 2024.

- Baragaña, B.; Forte, B.; Choi, R.; Nakazawa Hewitt, S.; Bueren-Calabuig, J.A.; Pisco, J.P.; Peet, C.; Dranow, D.M.; Robinson, D.A.; Jansen, C.; et al. Lysyl-TRNA Synthetase as a Drug Target in Malaria and Cryptosporidiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116, 7015–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, R.K. Plasmodium Falciparum -Infected Humanized Mice: A Viable Preclinical Tool. Immunotherapy 2021, 13, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okombo, J.; Kanai, M.; Deni, I.; Fidock, D.A. Genomic and Genetic Approaches to Studying Antimalarial Drug Resistance and Plasmodium Biology. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.R.; Davis, T.M. Updated Pharmacokinetic Considerations for the Use of Antimalarial Drugs in Pregnant Women. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2020, 16, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okombo, J.; Chibale, K. Recent Updates in the Discovery and Development of Novel Antimalarial Drug Candidates. Medchemcomm 2018, 9, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, B.K. . KAE609 (Cipargamin): Discovery of Spiroindolone Antimalarials. In Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry III; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 529–543.

- Mak, K.-K.; Epemolu, O.; Pichika, M.R. The Role of DMPK Science in Improving Pharmaceutical Research and Development Efficiency. Drug Discov. Today 2022, 27, 705–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Shi, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, M.; Qiu, F. Oral Bioavailability Comparison of Artemisinin, Deoxyartemisinin, and 10-Deoxoartemisinin Based on Computer Simulations and Pharmacokinetics in Rats. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musther, H.; Olivares-Morales, A.; Hatley, O.J.D.; Liu, B.; Rostami Hodjegan, A. Animal versus Human Oral Drug Bioavailability: Do They Correlate? Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 57, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stielow, M.; Witczyńska, A.; Kubryń, N.; Fijałkowski, Ł.; Nowaczyk, J.; Nowaczyk, A. The Bioavailability of Drugs—The Current State of Knowledge. Molecules 2023, 28, 8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerholm, U.; Hellberg, S.; Spjuth, O. Advances in Predictions of Oral Bioavailability of Candidate Drugs in Man with New Machine Learning Methodology. Molecules 2021, 26, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, A.; Sundriyal, S. Physicochemical Profiling and Comparison of Research Antiplasmodials and Advanced Stage Antimalarials with Oral Drugs. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 6424–6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Peng, J.; Li, Y.; Gong, L.; Lv, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; et al. Pharmacokinetics, Bioavailability, Excretion and Metabolism Studies of Akebia Saponin D in Rats: Causes of the Ultra-Low Oral Bioavailability and Metabolic Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samby, K.; Willis, P.A.; Burrows, J.N.; Laleu, B.; Webborn, P.J.H. Actives from MMV Open Access Boxes? A Suggested Way Forward. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Who Methods and Techniques for Assessing Exposure to Antimalarial Drugs in Clinical Field Studies. World Health 2011, 165.

- Waithera, M.W.; Sifuna, M.W.; Kariuki, D.W.; Kinyua, J.K.; Kimani, F.T.; Ng’ang’a, J.K.; Takei, M. Antimalarial Activity Assay of Artesunate-3-Chloro-4(4-Chlorophenoxy) Aniline in Vitro and in Mice Models. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, M.M.; Fernandes, C.; Remião, F.; Tiritan, M.E. Enantioselectivity in Drug Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity: Pharmacological Relevance and Analytical Methods. Molecules 2021, 26, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.A.; Beaumont, K.; Maurer, T.S.; Di, L. Volume of Distribution in Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5691–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alia, J.D.; Karl, S.; Kelly, T.D. Quantum Chemical Lipophilicities of Antimalarial Drugs in Relation to Terminal Half-Life. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 6500–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carucci, M.; Duez, J.; Tarning, J.; García-Barbazán, I.; Fricot-Monsinjon, A.; Sissoko, A.; Dumas, L.; Gamallo, P.; Beher, B.; Amireault, P.; et al. Safe Drugs with High Potential to Block Malaria Transmission Revealed by a Spleen-Mimetic Screening. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na-Bangchang, K.; Karbwang, J. Pharmacology of Antimalarial Drugs, Current Anti-Malarials. In Encyclopedia of Malaria; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2019; pp. 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wesolowski, C.A.; Wesolowski, M.J.; Babyn, P.S.; Wanasundara, S.N. Time Varying Apparent Volume of Distribution and Drug Half-Lives Following Intravenous Bolus Injections. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, R.; Cao, Y. A Method to Determine Pharmacokinetic Parameters Based on Andante Constant-Rate Intravenous Infusion. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banda, C.G.; Tarning, J.; Barnes, K.I. Use of Population Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic Modelling to Inform Antimalarial Dose Optimization in Infants. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.A.; Di, L.; Kerns, E.H. The Effect of Plasma Protein Binding on in Vivo Efficacy: Misconceptions in Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, C.-M.; Imre, S.; Vari, C.-E.; Muntean, D.-L.; Tero-Vescan, A. Ultrafiltration Method for Plasma Protein Binding Studies and Its Limitations. Processes 2021, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L. An Update on the Importance of Plasma Protein Binding in Drug Discovery and Development. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021, 16, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhango, E.K.G.; Snorradottir, B.S.; Kachingwe, B.H.K.; Katundu, K.G.H.; Gizurarson, S. Estimation of Pediatric Dosage of Antimalarial Drugs, Using Pharmacokinetic and Physiological Approach. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charman, S.A.; Andreu, A.; Barker, H.; Blundell, S.; Campbell, A.; Campbell, M.; Chen, G.; Chiu, F.C.K.; Crighton, E.; Katneni, K.; et al. An in Vitro Toolbox to Accelerate Anti-Malarial Drug Discovery and Development. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bteich, M. An Overview of Albumin and Alpha-1-Acid Glycoprotein Main Characteristics: Highlighting the Roles of Amino Acids in Binding Kinetics and Molecular Interactions. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, M.; Fajdetić, A.; Rupčić, R.; Alihodžić, S.; Žiher, D.; Bukvić Krajačić, M.; Smith, K.S.; Ivezić-Schönfeld, Z.; Padovan, J.; Landek, G.; et al. Antimalarial Activity of 9a- N Substituted 15-Membered Azalides with Improved in Vitro and in Vivo Activity over Azithromycin. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M.H.; Babalola, S.A.; Idris, A.Y.; Hamza, A.N.; Igie, N.; Odeyemi, I.; Musa, A.M.; Olorukooba, A.B. Therapeutic Potency of Mono- and Diprenylated Acetophenones: A Case Study of In-Vivo Antimalarial Evaluation. Pharm. Front. 2023, 05, e15–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Duan, H.; Yang, Y.; Yan, X.; Fan, K. Fenozyme Protects the Integrity of the Blood–Brain Barrier against Experimental Cerebral Malaria. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 8887–8895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, V.M.; Ayi, K.; Lu, Z.; Liby, K.T.; Sporn, M.; Kain, K.C. Synthetic Oleanane Triterpenoids Enhance Blood Brain Barrier Integrity and Improve Survival in Experimental Cerebral Malaria. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, N.; Prabhu, P. Emerging Avenues for the Management of Cerebral Malaria. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2022, 74, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goli, V.V.N.; Tatineni, S.; Hani, U.; Ghazwani, M.; Talath, S.; Sridhar, S.B.; Alhamhoom, Y.; Fatima, F.; Osmani, R.A.M.; Shivaswamy, U.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of a Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Co-Encapsulating Artemether and MiRNA for Mitigating Cerebral Malaria. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajula, S.N.R.; Nadimpalli, N.; Sonti, R. Drug Metabolic Stability in Early Drug Discovery to Develop Potential Lead Compounds. Drug Metab. Rev. 2021, 53, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siramshetty, V.B.; Shah, P.; Kerns, E.; Nguyen, K.; Yu, K.R.; Kabir, M.; Williams, J.; Neyra, J.; Southall, N.; Nguyễn, Ð.-T.; et al. Retrospective Assessment of Rat Liver Microsomal Stability at NCATS: Data and QSAR Models. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.J.; Laing, L.; Gibhard, L.; Wong, H.N.; Haynes, R.K.; Wiesner, L. Toward New Transmission-Blocking Combination Therapies: Pharmacokinetics of 10-Amino-Artemisinins and 11-Aza-Artemisinin and Comparison with Dihydroartemisinin and Artemether. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Słoczyńska, K.; Gunia-Krzyżak, A.; Koczurkiewicz, P.; Wójcik-Pszczoła, K.; Żelaszczyk, D.; Popiół, J.; Pękala, E. Metabolic Stability and Its Role in the Discovery of New Chemical Entities. Acta Pharm. 2019, 69, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagardère, P.; Mustière, R.; Amanzougaghene, N.; Hutter, S.; Casanova, M.; Franetich, J.-F.; Tajeri, S.; Malzert-Fréon, A.; Corvaisier, S.; Azas, N.; et al. New Antiplasmodial 4-Amino-Thieno [3,2-d]Pyrimidines with Improved Intestinal Permeability and Microsomal Stability. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 249, 115115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram-Ralph, E.; Amare, M. Factors Affecting Drug Absorption and Distribution. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2023, 24, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.J.; Laing, L.; Gibhard, L.; Wong, H.N.; Haynes, R.K.; Wiesner, L. Toward New Transmission-Blocking Combination Therapies: Pharmacokinetics of 10-Amino-Artemisinins and 11-Aza-Artemisinin and Comparison with Dihydroartemisinin and Artemether. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorjsuren, D.; Eastman, R.T.; Wicht, K.J.; Jansen, D.; Talley, D.C.; Sigmon, B.A.; Zakharov, A. V.; Roncal, N.; Girvin, A.T.; Antonova-Koch, Y.; et al. Chemoprotective Antimalarials Identified through Quantitative High-Throughput Screening of Plasmodium Blood and Liver Stage Parasites. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, B.R.; Yokokawa, F.; Kirrane, T.; Mata, A.-C.; Huang, R.; Blaquiere, N.; Waldron, G.; Zou, B.; Simon, O.; Vankadara, S.; et al. Discovery and Preclinical Pharmacology of INE963, a Potent and Fast-Acting Blood-Stage Antimalarial with a High Barrier to Resistance and Potential for Single-Dose Cures in Uncomplicated Malaria. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 3798–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appetecchia, F.; Fabbrizi, E.; Fiorentino, F.; Consalvi, S.; Biava, M.; Poce, G.; Rotili, D. Transmission-Blocking Strategies for Malaria Eradication: Recent Advances in Small-Molecule Drug Development. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagardère, P.; Mustière, R.; Amanzougaghene, N.; Hutter, S.; Casanova, M.; Franetich, J.-F.; Tajeri, S.; Malzert-Fréon, A.; Corvaisier, S.; Since, M.; et al. Novel Thienopyrimidones Targeting Hepatic and Erythrocytic Stages of Plasmodium Parasites with Increased Microsomal Stability. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 261, 115873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, A.; Gupta, S.; Shoaib, R.; Aneja, B.; Irfan, I.; Gupta, K.; Rawat, N.; Combrinck, J.; Kumar, B.; Aleem, M.; et al. Blood-Stage Antimalarial Activity, Favourable Metabolic Stability and in Vivo Toxicity of Novel Piperazine Linked 7-Chloroquinoline-Triazole Conjugates. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 115969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Lee, S.; Piao, Y.; Choi, M.; Bang, D.; Gu, J.; Kim, S. On Modeling and Utilizing Chemical Compound Information with Deep Learning Technologies: A Task-Oriented Approach. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 4288–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jusko, W.J. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetics of Lysosomotropic Chloroquine in Rat and Human. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2021, 376, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewitt, P.; Hartmann, A.; Tornesi, B.; Ferry-Martin, S.; Valentin, J.-P.; Desert, P.; Gresham, S.; Demarta-Gatsi, C.; Venishetty, V.K.; Kolly, C. Importance of Tailored Non-Clinical Safety Testing of Novel Antimalarial Drugs: Industry Best-Practice. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 154, 105736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Mambwe, D.; Korkor, C.M.; Chibale, K. Innovation Experiences from Africa-Led Drug Discovery at the Holistic Drug Discovery and Development (H3D) Centre. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, K.; Nantha Kumar, N.; Fazmin, I.T.; Edling, C.E.; Jeevaratnam, K. Anti-malarial Drugs: Mechanisms Underlying Their Proarrhythmic Effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 5237–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadioglu, O.; Klauck, S.M.; Fleischer, E.; Shan, L.; Efferth, T. Selection of Safe Artemisinin Derivatives Using a Machine Learning-Based Cardiotoxicity Platform and in Vitro and in Vivo Validation. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 2485–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira-Neto, J.L.; Wicht, K.J.; Chibale, K.; Burrows, J.N.; Fidock, D.A.; Winzeler, E.A. Author Correction: Antimalarial Drug Discovery: Progress and Approaches. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 880–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilefu, R.C.; Jumbo, U.K.; Oti, D.C.; Agwaraonye, C.K.; Okezie, O.P.; Anyanwu, W.C. Histopathological Evaluation of the Cardiotoxicity of Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine on Male Albino Rats. J. Biosci. Med. 2023, 11, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkez, H.; Arslan, M.E.; Ozdemir, O. Genotoxicity Testing: Progress and Prospects for the next Decade. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2017, 13, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Polaka, S.; Rajpoot, K.; Tekade, M.; Sharma, M.C.; Tekade, R.K. Importance of Toxicity Testing in Drug Discovery and Research. In Pharmacokinetics and Toxicokinetic Considerations; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 117–144.

- Araujo-Lima, C.F.; de Cassia Castro Carvalho, R.; Rosario, S.L.; Leite, D.I.; Aguiar, A.C.C.; de Souza Santos, L.V.; de Araujo, J.S.; Salomão, K.; Kaiser, C.R.; Krettli, A.U.; et al. Antiplasmodial, Trypanocidal, and Genotoxicity In Vitro Assessment of New Hybrid α,α-Difluorophenylacetamide-Statin Derivatives. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeragoni, D.; Deshpande, S.S.; Singh, V.; Misra, S.; Mutheneni, S.R. In Vitro and in Vivo Antimalarial Activity of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Sargassum Tenerrimum - a Marine Seaweed. Acta Trop. 2023, 245, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Park, H.; Lim, K.-M. Phototoxicity: Its Mechanism and Animal Alternative Test Methods. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 31, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.E.; Kennelley, G.E.; Amaye-Obu, T.; Jowdy, P.F.; Ghadersohi, S.; Nasir-Moin, M.; Paragh, G.; Berman, H.A.; Huss, W.J. The Phenomenon of Phototoxicity and Long-Term Risks of Commonly Prescribed and Structurally Diverse Drugs. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2024, 19, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidle, S. A Phenotypic Approach to the Discovery of Potent G-Quadruplex Targeted Drugs. Molecules 2024, 29, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Vazvaei-Smith, F.; Dear, G.; Boer, J.; Cuyckens, F.; Fraier, D.; Liang, Y.; Lu, D.; Mangus, H.; Moliner, P.; et al. Metabolite Bioanalysis in Drug Development: Recommendations from the <scp>IQ</Scp> Consortium Metabolite Bioanalysis Working Group. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 115, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, E.L.; Bento, A.F.; Cavalli, J.; Oliveira, S.K.; Schwanke, R.C.; Siqueira, J.M.; Freitas, C.S.; Marcon, R.; Calixto, J.B. Non-Clinical Studies in the Process of New Drug Development - Part II: Good Laboratory Practice, Metabolism, Pharmacokinetics, Safety and Dose Translation to Clinical Studies. Brazilian J. Med. Biol. Res. = Rev. Bras. Pesqui. medicas e Biol. 2016, 49, e5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshman, Y.E.; Winters, B.R.; Ryans, J.; Authier, S.; Pugsley, M.K. Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) Studies in Drug Toxicology Assessments. In Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Safety and Pharmacokinetic Assays; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tibon, N.S.; Ng, C.H.; Cheong, S.L. Current Progress in Antimalarial Pharmacotherapy and Multi-Target Drug Discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 188, 111983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulusu, K.C.; Guha, R.; Mason, D.J.; Lewis, R.P.I.; Muratov, E.; Kalantar Motamedi, Y.; Cokol, M.; Bender, A. Modelling of Compound Combination Effects and Applications to Efficacy and Toxicity: State-of-the-Art, Challenges and Perspectives. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.; Kovács, I.A.; Barabási, A.-L. Network-Based Prediction of Drug Combinations. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacaan, A.; Hashida, S.N.; Khan, N.K. Non-Clinical Combination Toxicology Studies: Strategy, Examples and Future Perspective. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 45, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azri-Meehan, S.; Latriano, L. Repeated-Dose Toxicity Studies in Nonclinical Drug Development. In Nonclinical Safety Assessment; Wiley, 2013; pp. 197–218.

- Schultz, T.W.; Cronin, M.T.D. Lessons Learned from Read-across Case Studies for Repeated-Dose Toxicity. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 88, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues-Junior, V.S.; Machado, P.; Calixto, J.B.; Siqueira, J.M.; Andrade, E.L.; Bento, A.F.; Campos, M.M.; Basso, L.A.; Santos, D.S. Preclinical Safety Evaluation of IQG-607 in Rats: Acute and Repeated Dose Toxicity Studies. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 86, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, K.H. Acute, Subacute, Subchronic, and Chronic General Toxicity Testing for Preclinical Drug Development. In A Comprehensive Guide to Toxicology in Nonclinical Drug Development; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 149–171.

- González, R.; Pons-Duran, C.; Bardají, A.; Leke, R.G.F.; Clark, R.; Menendez, C. Systematic Review of Artemisinin Embryotoxicity in Animals: Implications for Malaria Control in Human Pregnancy. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 402, 115127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Gaaloul, M.; Tornesi, B.; Lebus, F.; Reddy, D.; Kaszubska, W. Re-Orienting Anti-Malarial Drug Development to Better Serve Pregnant Women. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.L. Safety of Treating Malaria with Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapy in the First Trimester of Pregnancy. Reprod. Toxicol. 2022, 111, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olagunju, A.; Mathad, J.; Eke, A.; Delaney-Moretlwe, S.; Lockman, S. Considerations for the Use of Long-Acting and Extended-Release Agents During Pregnancy and Lactation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, S571–S578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Chetia, D. In Vitro and in Vivo Models Used for Antimalarial Activity: A Brief Review. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 5, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidock, D.A.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Croft, S.L.; Brun, R.; Nwaka, S. Antimalarial Drug Discovery: Efficacy Models for Compound Screening. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelli, F.; Odolini, S.; Autino, B.; Foca, E.; Russo, R. Malaria Prophylaxis: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 3212–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.J. The Assessment of Antimalarial Drug Efficacy in Vivo. Trends Parasitol. 2022, 38, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaribe, S.C.; Oladipupo, A.R.; Uche, G.C.; Onumba, M.U.; Ota, D.; Awodele, O.; Oyibo, W.A. Suppressive, Curative, and Prophylactic Potentials of an Antimalarial Polyherbal Mixture and Its Individual Components in Plasmodium Berghei-Infected Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 277, 114105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, R.P.; Tatham, L.M.; Savage, A.C.; Tripathi, A.K.; Mlambo, G.; Ippolito, M.M.; Nenortas, E.; Rannard, S.P.; Owen, A.; Shapiro, T.A. Long-Acting Injectable Atovaquone Nanomedicines for Malaria Prophylaxis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, A.J.; Bhardwaj, J.; Goyal, M.; Prakash, K.; Adnan, M.; Alreshidi, M.M.; Patel, M.; Soni, A.; Redman, W. Immune Responses in Liver and Spleen against Plasmodium Yoelii Pre-Erythrocytic Stages in Swiss Mice Model. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, B.; Krüger, A.; Du, X.; Visser, L.; Dömling, A.S.S.; Wrenger, C.; Groves, M.R. Discovery of Small-Molecule Allosteric Inhibitors of Pf ATC as Antimalarials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 19070–19077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravindar, L.; Hasbullah, S.A.; Rakesh, K.P.; Hassan, N.I. Pyrazole and Pyrazoline Derivatives as Antimalarial Agents: A Key Review. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 183, 106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkrumah, D.; Isaac Nketia, R.; Kofi Turkson, B.; Komlaga, G. Malaria: Epidemiology, Life Cycle of Parasite, Control Strategies and Potential Drug Screening Techniques. In Mosquito-Borne Tropical Diseases [Working Title]; IntechOpen, 2024.

- Sinha, S.; Medhi, B.; Radotra, B.D.; Batovska, D.; Markova, N.; Sehgal, R. Evaluation of Chalcone Derivatives for Their Role as Antiparasitic and Neuroprotectant in Experimentally Induced Cerebral Malaria Mouse Model. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radohery, G.F.R.; Walz, A.; Gumpp, C.; Cherkaoui-Rbati, M.H.; Gobeau, N.; Gower, J.; Davenport, M.P.; Rottmann, M.; McCarthy, J.S.; Möhrle, J.J.; et al. Parasite Viability as a Measure of In Vivo Drug Activity in Preclinical and Early Clinical Antimalarial Drug Assessment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walz, A.; Sax, S.; Scheurer, C.; Tamasi, B.; Mäser, P.; Wittlin, S. Incomplete Plasmodium Falciparum Growth Inhibition Following Piperaquine Treatment Translates into Increased Parasite Viability in the in Vitro Parasite Reduction Ratio Assay. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1396786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkah, N.K.; Schafer, C.; Kappe, S.H.I. Humanized Mouse Models for the Study of Human Malaria Parasite Biology, Pathogenesis, and Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiadou, A.; Dunican, C.; Soro-Barrio, P.; Lee, H.J.; Kaforou, M.; Cunnington, A.J. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Translationally Relevant Processes in Mouse Models of Malaria. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensalel, J.; Roberts, A.; Hernandez, K.; Pina, A.; Prempeh, W.; Babalola, B. V.; Cannata, P.; Lazaro, A.; Gallego-Delgado, J. Novel Experimental Mouse Model to Study Malaria-Associated Acute Kidney Injury. Pathogens 2023, 12, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genito, C.J.; Brooks, K.; Smith, A.; Ryan, E.; Soto, K.; Li, Y.; Warter, L.; Dutta, S. Protective Antibody Threshold of RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine Correlates Antigen and Adjuvant Dose in Mouse Model. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelínková, L.; Jhun, H.; Eaton, A.; Petrovsky, N.; Zavala, F.; Chackerian, B. An Epitope-Based Malaria Vaccine Targeting the Junctional Region of Circumsporozoite Protein. npj Vaccines 2021, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batarseh, A.M.; Vafaee, F.; Hosseini-Beheshti, E.; Safarchi, A.; Chen, A.; Cohen, A.; Juillard, A.; Hunt, N.H.; Mariani, M.; Mitchell, T.; et al. Investigation of Plasma-Derived Lipidome Profiles in Experimental Cerebral Malaria in a Mouse Model Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Yang, E.; Jia, M. Genome-Wide Liver Transcriptomic Profiling of a Malaria Mouse Model Reveals Disturbed Immune and Metabolic Responses. Parasit. Vectors 2023, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Cabral, P.; Weinerman, J.; Olivier, M.; Cermakian, N. Time of Day and Circadian Disruption Influence Host Response and Parasite Growth in a Mouse Model of Cerebral Malaria. iScience 2024, 27, 109684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, A.K.; Cooper, C.A.; Moore, J.M. A Novel Murine Model of Post-Implantation Malaria-Induced Preterm Birth. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0256060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, C.L.L.; Khoo, S.K.M.; Ong, J.L.E.; Ramireddi, G.K.; Yeo, T.W.; Teo, A. Malaria in Pregnancy: From Placental Infection to Its Abnormal Development and Damage. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, A. da S.; Soares, I.F.; Rodrigues-da-Silva, R.N.; Rodolphi, C.M.; Albrecht, L.; Donassolo, R.A.; Lopez-Camacho, C.; Ano Bom, A.P.D.; Neves, P.C. da C.; Conte, F. de P.; et al. Immunogenicity of PvCyRPA, PvCelTOS and Pvs25 Chimeric Recombinant Protein of Plasmodium Vivax in Murine Model. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techarang, T.; Jariyapong, P.; Viriyavejakul, P.; Punsawad, C. High Mobility Group Box-1 (HMGB-1) and Its Receptors in the Pathogenesis of Malaria-Associated Acute Lung Injury/Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in a Mouse Model. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackeline Pérez-Vega, M.; Manuel Corral-Ruiz, G.; Galán-Salinas, A.; Silva-García, R.; Mancilla-Herrera, I.; Barrios-Payán, J.; Fabila-Castillo, L.; Hernández-Pando, R.; Enid Sánchez-Torres, L. Acute Lung Injury Is Prevented by Monocyte Locomotion Inhibitory Factor in an Experimental Severe Malaria Mouse Model. Immunobiology 2024, 229, 152823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David-Vieira, C.; Carpinter, B.A.; Bezerra-Bellei, J.C.; Machado, L.F.; Raimundo, F.O.; Rodolphi, C.M.; Renhe, D.C.; Guedes, I.R.N.; Gonçalves, F.M.M.; Pereira, L.P.M.C.; et al. Lung Damage Induced by Plasmodium Berghei ANKA in Murine Model of Malarial Infection Is Mitigated by Dietary Supplementation with DHA-Rich Omega-3. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 3607–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.; De, A.; Sinha, A. Malaria and Hypertension: What Is the Direction of Association? Function 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Sahu, W.; Ojha, D.K.; Reddy, K.S.; Suar, M. Comparative Analysis of Host Metabolic Alterations in Murine Malaria Models with Uncomplicated or Severe Malaria. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 2261–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibraheem, Y.; Bayarsaikhan, G.; Inoue, S.-I. Host Immunity to Plasmodium Infection: Contribution of Plasmodium Berghei to Our Understanding of T Cell-Related Immune Response to Blood-Stage Malaria. Parasitol. Int. 2023, 92, 102646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vialard, F.; Allaeys, I.; Dong, G.; Phan, M.P.; Singh, U.; Hébert, M.J.; Dieudé, M.; Langlais, D.; Boilard, E.; Labbé, D.P.; et al. Thermoneutrality and Severe Malaria: Investigating the Effect of Warmer Environmental Temperatures on the Inflammatory Response and Disease Progression. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opata, M.M.; Gbedande, K.; Smith, M.R.; Onjiko, R.S. Neonatal Immunity to Malaria Using a Mouse Model. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 170.25–170.25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, M.; Yang, J.; Weitner, M.; Akkoyunlu, M. Neonatal Mice Resist Plasmodium Yoelii Infection until Exposed to Para-Aminobenzoic Acid Containing Diet after Weaning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Murine Model (Mice) | Inbred/Outbred | Preclinical Assays Conducted | Resistant/Susceptible to P. berghei | Murine Plasmodium Species Assessed | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | Inbred | Efficacy, Pharmacokinetics, Safety, | Susceptible |

P. yoelii, P. chabaudi, P. vinckei |

[33,37,45,79,80] |

| AKR/J | inbred | Pharmacokinetics | Resistant | - | [45] |

| C3H/HeJ | Inbred | Efficacy | Susceptible | P. chabaudi | [45,47] |

| CBA | Inbred | Efficacy | Susceptible |

P. yoelii, P. chabaudi, P. vinckei |

[43,49,81] |

| SJL/J | Inbred | Susceptible | P. chabaudi | [45,50] | |

| C57Bl/6 | Inbred | Efficacy, Safety |

Susceptible |

P. yoelii, P. chabaudiP. falciparum, P. vinckei |

[20,24,43,55,56]. |

| DBA/2J | Inbred | Resistant |

P. yoelii , P. chabaudi, P. vinckei, |

[82,83,84,85,86] | |

| Swiss Webster | Outbred | Efficacy, Toxicity |

Susceptible |

P. yoelii P. chabaudi |

[28,25,28,87,88,89] |

| ICR | Outbred | Efficacy, Pharmacokinetics, Safety |

Susceptible |

P. yoelii , P. chabaudi, P. vinckei |

[13,90,91,92,93] |

| CD1 | Outbred | Efficacy, Pharmacokinetics, Safety |

Susceptible | P. chabaudi, P. yoelii | [36,66,67,68,94] |

| NMRI | Outbred | Efficacy, Pharmacokinetics, Safety |

Susceptible | P. chabaudi, P. yoelii | [72,95,96,97,98] |

| NOD/SCID/γcnull (NOG) | Humanized | Efficacy, Pharmacokinetics |

P. falciparum | [73,74,82] | |

| NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ | Humanized | Efficacy, Pharmacokinetics |

P. falciparum | [99,100] |

|

| FRG NOD huHep | Humanized | Efficacy | P. falciparum | [78] | |

| 5xfad | Transgenic | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).