1. Introduction

For For decades, the detrimental effects of tobacco use on global health have been well-documented. Tobacco consumption in any form remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, affecting millions of individuals worldwide annually [

1,

2]. A recent systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study revealed a death statistic of over 8 million people from a tobacco-related disease in 2019 alone [

3]. Highlighting the regional impact of this global issue, unfortunately, WHO statistical trends indicated a gradual increase in tobacco use among individuals aged 15 and older in Saudi Arabia, from 16.6% in 2000 to 17.5% in 2020. Notably, tobacco use in Saudi Arabia was more prevalent among males (27.8% in 2020) compared to females (2.0% in 2020)[

1] However, the consumption of tobacco products showed a continued decline globally, with about 1 in 5 adults worldwide consuming tobacco compared to 1 in 3 in 2000 [

2]. Despite this positive global trend, a paradoxical rise in annual tobacco-related deaths is anticipated, because tobacco kills its users and people exposed to its emissions slowly [

4].

While traditional cigarettes remain a public health concern, their dominance as the primary form of tobacco use appears to be waning, particularly among youth populations [

5]. In the recent decade, the emergence of an increasingly diverse array of nicotine-containing products has gaining popularity, including electronic cigarettes (E-cigs) [

5], tobacco heating products [

6], and oral nicotine pouches (ONPs) [

7].

ONPs are pre-portioned pouches that share similarities with Snus, a traditional smokeless tobacco product. However, unlike Snus, ONPs are demonstrably tobacco-free, relying solely on nicotine, flavorings, sweeteners, and plant-based fibers for their composition [

8]. This unique characteristic translates to a convenient, discreet, and potentially palatable method of nicotine delivery, potentially appealing to a broader user base, particularly in environments where traditional tobacco use is restricted. Capitalizing on this innovation and the growing social stigma against conventional tobacco use, large tobacco companies have marketed ONPs as "tobacco-free" [

7,

9], “tobacco leaf-free” [

9,

10], or “all white” [

10] alternatives. This marketing strategy positions ONPs within the emerging category of "modern oral" nicotine products, alongside established options like nicotine lozenges and gum [

11].

ONPs entered the U.S. market in 2016, and as an emerging product, sales have witnessed a dramatic rise. Sales figures indicate a significant increase from 0.16 million units (

$0.7 million) in 2016 to a staggering 46 million units (

$200 million) within the first half of 2020 alone [

12]. With further growth reaching

$808 million from January to March 2022 [

13]. This rapid growth in popularity highlights the evolving global market for ONPs, which is projected to reach

$22.98 billion by 2030 [

14]. However, the non-targeted marketing of ONPs raises concerns, especially as they appear to be appealing to youth and young adult non-smokers. This raises concerns about the potential for initiation and increased use among these vulnerable populations.

The composition of nicotine within ONPs plays a crucial role in their potential for addiction. Unlike traditional cigarettes where nicotine exists primarily in its free-base form, ONPs can contain nicotine in both protonated and unprotonated forms depending on their pH [

15]. Protonated nicotine predominates at a pH below 6.0, while unprotonated (free-base) nicotine increasingly predominates as the pH rises above 6.0 [

15]. Compared with protonated nicotine, unprotonated nicotine readily passes through the oral mucosa epithelium, leading to faster and more extensive increases in blood nicotine levels [

16]. Consequently, some ONPs formulated with a higher proportion of unprotonated nicotine may pose a greater risk of nicotine dependence due to the enhanced bioavailability [

16]. This concern is particularly relevant for youth, who are a growing target demographic for ONPs [

17,

18]. Nicotine is a highly addictive substance, and its use during adolescence can negatively impact brain development, potentially priming the brain for addiction to other drugs [

19]

While smokeless tobacco products, including ONPs, generally lack the typical tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) found in combusted cigarettes, toxicological concerns regarding these products still exist [

20]. Unsmoked tobacco can still harbor TSNAs in various forms, including N-nitrosonornicotine (NNN), N-nitrosoanatabine (NAT), N-nitrosoanabasine (NAB), and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) [

21]. A recent study by Mallock et al. [

22] detected the presence of TSNAs in over half (26 out of 44) of the analyzed nicotine pouch products. The highest measured concentrations, though relatively low, were 13 ng and 5.4 ng per pouch for NNN and NNK, respectively. In addition to nicotine and TSNAs, toxic chromium and formaldehyde were detected in some nicotine pouch products [

7]. Any trace of toxic elements should not be present because of potential health risks. Exposure to NNN has been linked to an increased risk of esophageal tumors [

20]. This association raises particular concern for ONPs, given their placement within the oral cavity and potential for prolonged contact with esophageal tissue.

In summary, oral nicotine products mainly contains nicotine, flavorings, pH buffer, filling agents, as well as a trace of toxic TSNAs, metal, and formaldehyde. This mix may pose several health risks. Hence, in this survey study, we will assess awareness and susceptibility to ONP use among Saudi adults, along with investigating the side effects experienced by those who have used them. The findings from this survey will provide valuable insights into the landscape of ONP use in Riyadh region of Saudi Arabia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Procedure

A cross-sectional survey conducted over a seven-months period, from April 2024 to November 2024 to investigate ONPs awareness, use patterns, and beliefs targeting Saudi adults’ population in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia (18-69 years old). Following informed consent, 831 participants (age ≥ 18 years) were recruited through cluster sampling based on age, gender, and Riyadh districts. Data collection utilized a web-based, close-ended questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 19 questions, divided into two sections. The first section focused on demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and existing use of nicotine sources. The second section explored participants' awareness of ONPs, their usage patterns, associated beliefs, and any symptoms experienced during ONP use. Participants completed the questionnaire online or in-person, with data anonymized and analyzed using Google Sheets. To assess internal consistency, a simple mathematical question (2+2) achieved a 97.3% correct response rate. Internal validity was further supported by including two related questions: nicotine pouch use and associated symptoms. Participants answering "no" to the first question logically skipped the symptom question. Discrepant responses (n=16) were excluded after review. Ethical approval was granted by Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University's research ethics committee.

2.2. ONP Awareness, Susceptibility, Beliefs and Associated Use Symptoms

Respondents were presented with an image of some popular brands of ONP and asked the following questions: “Have you ever seen or heard of nicotine pouches before this study?” Those who answered “yes” were classified as being aware of ONPs, and those who answered “no” or “not sure” were classified as being unaware of ONPs. All ONP non-user respondents were then asked ONP susceptibility measures: “Are you curious about nicotine pouches?” , “Have you received sufficient information about the dangers of nicotine pouches?” and “Do you know someone around you use nicotine pouch, and would you use them if they offer you?”. Respondents who answered that were not curious about ONP, and know about its health risks and would not use them were classified as non-susceptible to ONP use. Otherwise, respondents were classified as susceptible to ONP use. They were then asked to assess their beliefs about ONP health risks by rating their agreement with the following statements: “Do you think nicotine pouches pose a health risk”, “Do you think nicotine pouches help you quit smoking”, and “Do you think nicotine pouches lead to addiction”. Responses were categorized as “agree” , “not sure” and “disagree”. Additionally, respondents who answered “yes” for using ONP were asked if they experienced any of the following symptoms associated with ONP use: “Frequent coughing”, “White spots and ulcerations in the mouth”, “taste alteration”, “Dry mouth, “throat symptoms”, “Abdominal pain or digestive disorders”, “No symptoms”, or Other symptoms.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Post-stratification weights were applied to achieve representativeness within the target population of Saudi adults aged 18-69 years in the Riyadh region, estimated at 2.5 million out of the 4.43 million Saudi residents in Riyadh, based on the latest Saudi census data [

23].Three sets of weighted logistic regression models were fitted. First, ONP awareness (aware vs. unaware) was modeled as the dependent variable, with demographics and nicotine-containing product use as independent variables. Second, ONP use status (user vs. non-user) was modeled as the dependent variable, with demographics and nicotine-containing product use as independent variables. This approach allowed for the examination of the association between demographics and nicotine-containing products with ONP awareness and use, while accounting for potential confounding effects. Lastly, weighted multinominal regression was conducted to examine the associations between ONP- related beliefs and ONP susceptibility and use statuses. Each belief was modeled separately, using “disagree” as the reference, adjusting for demographics and tobacco product use statuses. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 10.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Covariates of ONP Awareness and Use

The prevalence of ONP awareness and use across genders, various age groups and other nicotine product use statuses are presented in

Table 1. Furthermore, adjusted odds ratios (ORadj) are provided to quantify the associations between these variables and ONP awareness and use. Overall, 59.3% (n = 493) were aware of ONPs, 85.8% (n = 713) non-user ONPs, and 14.2% (n = 118) used ONPs. Results from the multivariable logistic regression models revealed that males were more aware (ORadj = 1.97,

p <0.0001) and user (ORadj = 2.86,

p = 0.03) of ONP than females. Similarly, younger adults (aged 18-29 and 30-39 years) demonstrated higher ONP awareness (ORadj = 4.67 and 4.88, respectively, both

p < 0.0001) and use (ORadj = 6.91,

p <0.002 and 6.12,

p < 0.003, respectively) compared to older adults (40-69 years). Additionally, ONP users were more likely to be cigarette (ORadj = 9.53,

p <0.0001) or e-cigarette (ORadj = 8.43,

p <0.0001) smokers and less likely to be non-smoker (ORadj = 0.19,

p = 0.006). Notably, only 4.2% of ONPs user were non-smoker, while 73.7%, 56.8% and 33.1% combined ONPs use with cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and hookah, respectively (not shown in the table).

3.2. Susceptibility and Perceptions for ONPs Use

Table 2 shows the prevalence of NP beliefs and their associations with ONPs susceptibility and use statuses. Approximately 60% (n = 503) of participants demonstrated susceptibility to ONP use, characterized by curiosity, limited knowledge of health risks, and potential willingness to use. Overall, over half of participants (54.6%) perceived ONPs as posing a health risk, while 25.4% believed they could aid in smoking cessation. However, most participants (70.2%) disagreed to the addictive potential of ONPs, and 84.5% acknowledged a lack of sufficient information regarding their dangers. Furthermore, 62.2% expressed a desire for additional information about nicotine pouches. Multivariate multinomial regression analysis revealed that ONP users expressed more positive perceptions regarding ONP health risks and smoking cessation benefits compared to other groups when disagreeing with a belief was the reference. Notably, agreement odds of ONPs health risks were significantly lower among ONPs users (ORadj = 0.13,

p <0.0001), and higher among the non-susceptible non-user group (ORadj = 14.56,

p = 0.0005), while the susceptible non-user group exhibited an insignificant association with agreement (ORadj = 1.07,

p = 0.83). Additionally, agreement odds about ONPs smoking cessation benefits were found to be higher among ONPs users (ORadj = 7.84,

p < 0.0001), and lower among the non-susceptible non-user group (ORadj = 0.09,

p < 0.0001) and the susceptible non-user group (ORadj = 0.56, p= 0.02). Furthermore, the susceptible non-user group demonstrated significantly lack of sufficient information about the dangers of ONPs (ORadj = 0.24,

p < 0.0001).

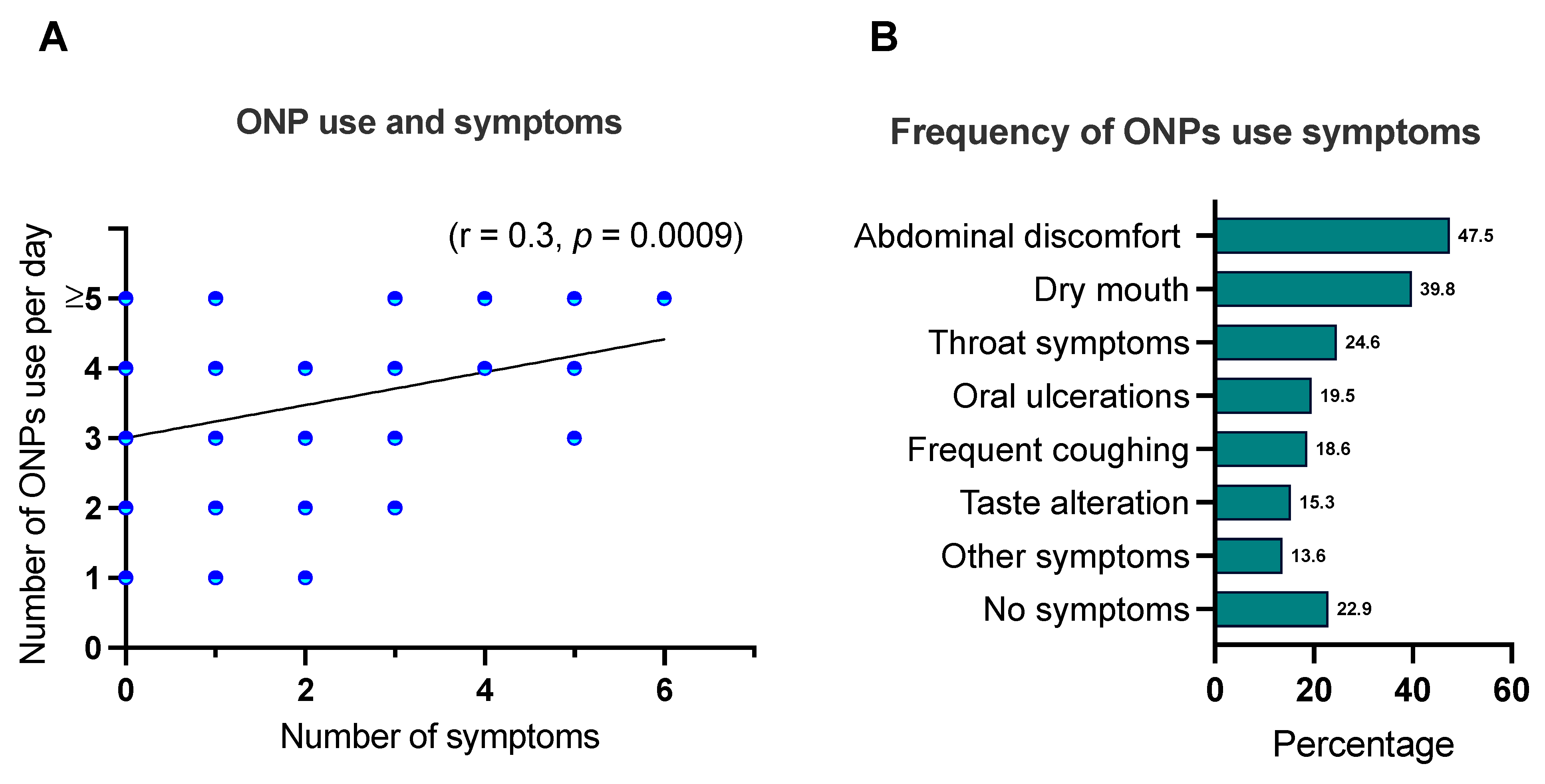

3.3. ONPs Associated Use Symptoms

A positive correlation was observed between the frequency of ONPs use and the likelihood of experiencing associated symptoms (r = 0.3,

p = 0.0009) (

Figure 1A). Among reported symptoms, gastrointestinal disturbances were most prevalent, with 47.5% of participants experiencing abdominal discomfort. Conversely, 22.9% of participants reported no discernible symptoms associated with ONP use (

Figure 1B).

4. Discussion

This study represents the first investigation in Saudi Arabia to assess the prevalence of ONPs use, awareness, susceptibility, and associated symptoms among adult Saudis. The overall awareness rate of ONPs was found to be 59.3%, while 14.2% of participants reported ever using ONPs. These findings align with global trends, particularly in the United States, where awareness and use have significantly increased over the past few years among US adults who smoke. In 2020, awareness and ever-use rates in the U.S. were 19.5% and 3.0%, respectively [

24], increasing to 29.2% and 5.6% between January and February 2021 [

25] and further to 46.6% and 19.4% in 2021 [

26] This relatively high rates of awareness observed in Saudi Arabia may be attributed to the extensive marketing of recently introduced ONP products by Badael, a company that aim to offer alternatives that improve health and positively impact the environment [

27] Their marketing emphasizes ONPs as a potential aid for smoking cessation [

28].

It is noteworthy in our study that 95.8% of ONP users were cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or hookah smokers, with significantly higher odds of ever using cigarettes (ORadj = 9.53) and e-cigarettes (ORadj = 8.43). This may indicate a potential positive public health impact in future for ONPs, as harm reduction strategy within the context of smoking cessation, in Saudi Arabia. However, continuous surveillance and targeted public health interventions are crucial to mitigate the potential negative consequences of ONP use. Notably, Keller-Hamilton and colleagues [

29], reported that ONPs may not effectively facilitate tobacco cessation due to their potential for craving relief and their higher plasma nicotine delivery compared to traditional cigarettes, which could increase the risk of misuse.

Given these findings, the need for regulation of ONPs in Saudi Arabia becomes apparent. While ONPs are under the jurisdiction of the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA), they currently remain unregulated and are permitted advertising, unlike traditional cigarettes and other nicotine-delivery products [

30]. The impact of regulation absence , especially in advertising, is evident in our study that while 59.3% of participants were aware of ONPs product, yet 84.5% reported a lack of sufficient knowledge of ONP potential dangers and 62.2% expressed a desire for more scientific information about the potential harms of ONPs. This knowledge gap may be attributed to the prevalence of promotional materials that present ONPs as a safe alternative to smoking.

We assessed in our study the comparative ONP-beliefs to susceptibility and use. Our findings indicate that between the 54.6% of participants who believed that ONP pose a health risks, only 6.6% of them (not shown in the table) were ONP ever users (ORadj = 0.13). Conversely, among the 25.4% of participants who believed ONPs aid in smoking cessation, 40.3% were ONP ever user (ORadj = 7.84). These results suggest that holding favorable beliefs about ONPs is associated with ONP use. Our findings align with previous study by Morean and colleagues which reported that young adults susceptible to or using ONPs were significantly more likely to hold favorable perceptions of ONPs compared to smokeless tobacco (ORadj = 2.54 and 2.18, respectively) [

31]. And to other studies that have reported a favorable ONP beliefs association to susceptibility to ONP use and awareness [

26,

32]. However, while our study suggests an association between specific beliefs to ONP use and susceptibility, it's important to note that the susceptible non-user group held comparable beliefs agreement regarding ONP health risks and uncertainty about ONP potential addiction and smoking cessation aid (ORadj = 12.07 and 1.77; respectively). This warrant further longitudinal studies to explore this relationship and to confirm the long-term implications of these beliefs.

Several studies have investigated the potential side effects of ONPs. While no serious adverse effects have been reported, local oral irritations such as mucosal redness, ulcerations, gingival blisters, dry mouth, and sore throat have been observed, particularly among long-term use and frequent consumption of ONP [

33,

34,

35].Furthermore, animal and in vitro studies have indicated that nicotine can promote conditions like gingivitis [

36] periodontal disease [

37] and bone destruction [

38], suggesting that ONPs may contribute to inflammation in periodontal tissues. Our study assessed the frequency of self-reported symptoms associated with ONP use and found a positive correlation between usage frequency and symptom prevalence (r = 0.3,

p = 0.0009). Abdominal disturbances were the most common symptom, reported by 47.5% of participants, followed by dry mouth (39.8%), throat symptoms (24.6%), oral ulceration (19.5%), frequent coughing (18.6%), taste alteration and (15.3%). However, 22.9% of participants reported no discernible symptoms. Mallock-Ohnesorg and colleagues studied nicotine pharmacokinetic side effects of ONP use and reported cardiovascular effects of increased heart rate and elevated arterial stiffness [

39]. These acute cardiovascular effects raise concerns about potential risks of increased arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis, and myocardial infarction, particularly in individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions [

39]. These findings suggests that ONPs may exert systemic effects beyond local oral irritation. Given the limited long-term health data on ONPs, further research is crucial to comprehensively assess their potential health risks.

This study, while providing valuable insights into ONP use and beliefs in Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia, has several limitations. First, due to the novelty of ONPs and the limited existing research, our sample size was relatively small and specific to the Riyadh region. Future studies should consider larger and more diverse samples to enhance generalizability. Second, the relative novelty of ONPs might have influenced participant understanding. To mitigate this, we provided visual aids and "not sure" options for belief-related questions. However, further research may be needed to assess the extent of participant knowledge and understanding. Third, the reliance on self-reported data through anonymous online surveys may introduce biases and inaccuracies. While Google Forms is a widely accepted tool, it may exclude individuals without internet access. Finally, the study did not account for underlying medical conditions that may have influenced reported symptoms. Future research should consider incorporating detailed medical history assessments to better understand the potential health impacts of ONP use.

5. Conclusions

This study represents the first investigation into the awareness, susceptibility, and use of ONPs among Saudi adults in the Riyadh region, along with an assessment of associated side effects. While 59.3% of participants were aware of ONPs and 14.2% reported using them, it is notable that 95.8% of ONP users were current smokers, suggesting a potential positive role for ONPs as a harm reduction strategy within the context of smoking cessation in the Saudi population in Riyadh. Our findings also suggest a correlation between positive beliefs about ONPs and their use, while non-susceptible non-users hold more negative views. Moreover, While this study has identified potential side effects associated with ONP use, further research is needed to comprehensively assess both short-term and long-term health impacts. Given the potential risks associated with nicotine addiction and the limited long-term data on ONP safety, ongoing public health surveillance and targeted interventions are crucial to address the potential challenges posed by ONP use in Saudi Araba.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A., A.A, and M.K; methodology H.A., A.A, and M.K.; validation, H.A., A.A, and M.K.; formal analysis, H.A., A.A, and M.K.; Data collection, H.A., A.A, M.K, M.A, B.A, H.G.A, Y.A, M.G, and F.A.; resources, H.A.; data curation, H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A., A.A, and M.K.; writing—review and editing, H.A., A.A, M.K, M.A, B.A, H.G.A, Y.A, M.G, and F.A.; supervision, H.A.; project administration, H.A.; funding acquisition, H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, award number 2024/03/29700.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the standing committee of Bioethics research (SCBR) of {rince Sattam bin Abdulaziz Unviersity (Approval No. SCBR-357/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions..

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use 2000-2025; World Health Organization, 2020; ISBN 9789240000032.

- World health organization Tobacco. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Murray, C.J.L.; Aravkin, A.Y.; Zheng, P.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Abdollahpour, I.; et al. Global Burden of 87 Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilano, V.; Gilmour, S.; Moffiet, T.; D’Espaignet, E.T.; Stevens, G.A.; Commar, A.; Tuyl, F.; Hudson, I.; Shibuya, K. Global Trends and Projections for Tobacco Use, 1990-2025: An Analysis of Smoking Indicators from the WHO Comprehensive Information Systems for Tobacco Control. The Lancet 2015, 385, 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramôa, C.P.; Eissenberg, T.; Sahingur, S.E. Increasing Popularity of Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking and Electronic Cigarette Use: Implications for Oral Healthcare. J Periodontal Res 2017, 52, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialous, S.A.; Glantz, S.A. Heated Tobacco Products: Another Tobacco Industry Global Strategy to Slow Progress in Tobacco Control. Tob Control 2018, 27, s111–s117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, D.; Liu, C.; Murphy, J. Chemical Characterization of Tobacco-Free “Modern” Oral Nicotine Pouches and Their Position on the Toxicant and Risk Continuums. Drug Chem Toxicol 2022, 45, 2246–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebraska University Health Center Nicotine Pouches: Are They Safer than Chewing, Smoking or Vaping? Available online: https://health.unl.edu/nicotine-pouches-are-they-safer-chewing-smoking-or-vaping (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Robichaud, M.O.; Seidenberg, A.B.; Byron, M.J. Tobacco Companies Introduce “tobacco-Free” Nicotine Pouches. Tob Control 2020, 29, E145–E146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Rensch, J.; Wang, J.; Jin, X.; Vansickel, A.; Edmiston, J.; Sarkar, M. Nicotine Pharmacokinetics and Subjective Responses after Using Nicotine Pouches with Different Nicotine Levels Compared to Combustible Cigarettes and Moist Smokeless Tobacco in Adult Tobacco Users. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2022, 239, 2863–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- East, N.; Bishop, E.; Breheny, D.; Gaca, M.; Thorne, D. A Screening Approach for the Evaluation of Tobacco-Free ‘Modern Oral’ Nicotine Products Using Real Time Cell Analysis. Toxicol Rep 2021, 8, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholap, V. V.; Kosmider, L.; Golshahi, L.; Halquist, M.S. Nicotine Forms: Why and How Do They Matter in Nicotine Delivery from Electronic Cigarettes? Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2020, 17, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anuja Majmundar, P.M.C.O.M.A.X.M. et al Nicotine Pouch Sales Trends in the US by Volume and Nicotine Concentration Levels From 2019 to 2022 Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2798449 (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Research, N.T.V. Nicotine Pouches Market Size Worth $22.98 Billion by 2030. (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Stanfill, S.; Tran, H.; Tyx, R.; Fernandez, C.; Zhu, W.; Marynak, K.; King, B.; Valentín-Blasini, L.; Blount, B.C.; Watson, C. Characterization of Total and Unprotonated (Free) Nicotine Content of Nicotine Pouch Products. Nicotine and Tobacco Research 2021, 23, 1590–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, T.S.; Stanfill, S.B.; Zhang, L.; Ashley, D.L.; Watson, C.H. Chemical Characterization of Domestic Oral Tobacco Products: Total Nicotine, PH, Unprotonated Nicotine and Tobacco-Specific N-Nitrosamines. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 57, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew Chapman New Products, Old Tricks? Concerns Big Tobacco Is Targeting Youngsters — The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (En-GB) Available online: https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2021-02-21/new-products-old-tricks-concerns-big-tobacco-is-targeting-youngsters (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Jackler, RK.; Chau, C.; Getachew, BD.; Al, E. JUUL Advertising over Its First Three Years on the Market: Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, Stanford University School of Medicine: Stanford, CA, USA, 2019.

- Department of Health, U.; Services, H.; for Disease Control, C.; Center for Chronic Disease Prevention, N.; Promotion, H.; on Smoking, O. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans.; International Agency for Research on Cancer. Smokeless Tobacco ; and, Some Tobacco-Specific N-Nitrosamines.; World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2007; ISBN 9789283212898.

- Akanksha Vishwakarma & Digvijay Verma Microorganisms: Crucial Players of Smokeless Tobacco for Several Health Attributes Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-021-11460-2 (accessed on 19 July 2024).

- Mallock, N.; Schulz, T.; Malke, S.; Dreiack, N.; Laux, P.; Luch, A. Levels of Nicotine and Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines in Oral Nicotine Pouches. Tob Control 2024, 33, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Authority for Statistics Saudi Census. Available online: https://portal.saudicensus.sa/portal/public/1/17/101497?type=TABLE (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Felicione, N.J.; Schneller, L.M.; Goniewicz, M.L.; Hyland, A.J.; Cummings, K.M.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Fong, G.T.; O’Connor, R.J. Oral Nicotine Product Awareness and Use Among People Who Smoke and Vape in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2022, 63, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrywna, M.; Gonsalves, N.J.; Delnevo, C.D.; Wackowski, O.A. Nicotine Pouch Product Awareness, Interest and Ever Use among US Adults Who Smoke, 2021. Tob Control 2023, 32, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrock, L.S.; Phan, L.; Chen-Sankey, J.; Hacker, K.; Ajith, A.; Jewett, B.; Choi, K. Nicotine Pouch: Awareness, Beliefs, Use, and Susceptibility among Current Tobacco Users in the United States, 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badael: Who We Are. Available online: https://badaelcompany.com/en/about#whoWeAre (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Badael:Products. Available online: https://badaelcompany.com/en/products (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Keller-Hamilton, B.; Alalwan, M.A.; Curran, H.; Hinton, A.; Long, L.; Chrzan, K.; Wagener, T.L.; Atkinson, L.; Suraapaneni, S.; Mays, D. Evaluating the Effects of Nicotine Concentration on the Appeal and Nicotine Delivery of Oral Nicotine Pouches among Rural and Appalachian Adults Who Smoke Cigarettes: A Randomized Cross-over Study. Addiction 2024, 119, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Food & Drug Authority SFDA.FD5005:2020 “E-Liquids and Heated Tobacco in Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems”. Available online: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/sites/default/files/2021-10/ElectronicNicotineDeliverySystems.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Morean, M.E.; Bold, K.W.; Davis, D.R.; Kong, G.; Krishnan-Sarin, S.; Camenga, D.R. Awareness, Susceptibility, and Use of Oral Nicotine Pouches and Comparative Risk Perceptions with Smokeless Tobacco among Young Adults in the United States. PLoS One 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, E.A.; Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Kechter, A.; Tackett, A.P.; Liu, F.; Sussman, S.; Lerman, C.; Unger, J.B.; Halbert, C.H.; Chaffee, B.W.; et al. Differences in Young Adults’ Perceptions of and Willingness to Use Nicotine Pouches by Tobacco Use Status. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungraungrayabkul, D.; Gaewkhiew, P.; Vichayanrat, T.; Shrestha, B.; Buajeeb, W. What Is the Impact of Nicotine Pouches on Oral Health: A Systematic Review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadehgharib, S.; Lehrkinder, A.; Alshabeeb, A.; Östberg, A.K.; Lingström, P. The Effect of a Non-Tobacco-Based Nicotine Pouch on Mucosal Lesions Caused by Swedish Smokeless Tobacco (Snus). Eur J Oral Sci 2022, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miluna, S.; Melderis, R.; Briuka, L.; Skadins, I.; Broks, R.; Kroica, J.; Rostoka, D. The Correlation of Swedish Snus, Nicotine Pouches and Other Tobacco Products with Oral Mucosal Health and Salivary Biomarkers. Dent J (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. K. Johnson, J.M.G.S.J.C.C.O.D.V.D. Interleukin-1 and Interleukin-8 in Nicotine- and Lipopolysaccharide-Exposed Gingival Keratinocyte Cultures. Journal of Periodontal Research 2010.

- Kubota, M.; Yanagita, M.; Mori, K.; Hasegawa, S.; Yamashita, M.; Yamada, S.; Kitamura, M.; Murakami, S. The Effects of Cigarette Smoke Condensate and Nicotine on Periodontal Tissue in a Periodontitis Model Mouse. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvaro Francisco Bosco, S.B.J.M. de A.D.S.L.M.J.H.N.V.G.G. A Histologic and Histometric Assessment of the Influence of Nicotine on Alveolar Bone Loss in Rats. Journal of Periodontology 2007.

- Mallock-Ohnesorg, N.; Rabenstein, A.; Stoll, Y.; Gertzen, M.; Rieder, B.; Malke, S.; Burgmann, N.; Laux, P.; Pieper, E.; Schulz, T.; et al. Small Pouches, but High Nicotine Doses—Nicotine Delivery and Acute Effects after Use of Tobacco-Free Nicotine Pouches. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).