1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) reports, tobacco consumption in Europe decreased by 9.3% between 2000 and 2020 [

1]. In Spain, the National Health Surveys (NHS) also pointed towards an overall decrease in tobacco consumption, from 38.4% in 1987 to 18.3% in 2023 [

2]. Several factors have contributed to this decline, such as measures included in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) [

3], related to sales regulations, smoke-free environments, bans on advertising and sponsorship, and restrictions on the availability and accessibility of tobacco—especially for young people. These measures influenced the development of Spanish legislation in 2005 and 2010 [

4,

5].

Nevertheless, tobacco use persists among 30% of the Spanish population aged 14 to 65, and 19.8% of those aged 15 and over [

2]. The use of new electronic nicotine delivery systems, such as electronic cigarettes (ECs), has risen in recent years. In Spain, the 2015 EDADES survey reported 6.8% of the population aged 15 to 63 had tried ECs at least once in their lives. By the 2022 survey, this figure had increased to 12.1%, and in the most recent survey published in 2024, it had risen further to 19% [

6]. Consumption within the past 30 days has risen from 1.5% in 2018 to 2.2% in 2022, reaching 4.6% in 2024 [

6]. According to the ESTUDES survey, conducted biennially among secondary school students aged 14 to 18, 17% had tried ECs at least once by 2014. By 2021, this percentage had risen to 44.3%, and in the most recent survey conducted in 2023, over half of the respondents (54.6%) reported having tried it. As many as 26.3% reported using ECs in the past 30 days [

7].

In Europe, the Eurobarometer estimates that 6% of Europeans have used ECs, with 3% being regular consumers[

8]. It estimated that 82 million people were using ECs in 2021 [

9].

The rise of ECs entails significant challenges for tobacco control. The evidence regarding the risks and benefits of EC use is subject to debate and varying interpretations. In clinical settings, when combined with counselling, ECs are more effective for smoking cessation than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), although a significant number of users continue using them long-term [

10]. There is no evidence to suggest that it is more effective than varenicline [

10]. Outside of clinical settings, its effectiveness in helping people quit conventional cigarettes is highly discussed and may even hinder the quitting process [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Conversely, some have suggested that EC use may increase the likelihood of taking up smoking, potentially acting as a gateway. A systematic review estimates that non-smokers who begin using ECs are three times more likely to start smoking conventional cigarettes compared to those who do not [

15,

16].

The population’s use of new nicotine products fosters the adoption of various delivery methods depending on the environment and context. As a result, dual use of ECs and conventional tobacco may become a common pattern, especially in countries where EC use is more widely accepted [

17]. In the UK, overall dual use has risen from 3.5% to 5.2%, while among smokers; it has increased from 19.5% to 34.2%. Some studies report that between 19.6% and 59.4% of young smokers engage in dual use (ECs and conventional tobacco) which may decrease the motivation to quit, thereby sustaining nicotine addiction among smokers[

11,

12]. Dual users tend to have higher levels of dependence [

18] and may face an increased risk of disease [

19,

20].

The latest WHO report [

1], highlights the importance of monitoring EC use among adults and adolescents alike to gain a better insight into the factors involved and how usage patterns evolve over time. Dual use of ECs and conventional cigarettes may present a public health concern due to the health risks linked to tobacco use, the possible added risks from dual use, not to mention the ongoing nicotine dependence. Therefore, this study aims to describe the use of ECs and dual use among the Spanish population aged 15–64 who participated in the 2022 Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain (EDADES)[

21] , as well as to analyse the associated sociodemographic characteristics and perceived health status.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

Descriptive cross-sectional study of participants from the 2022 EDADES survey, in the Spanish population aged 15 to 64 years.

The primary objective is to ascertain the prevalence of dual use of conventional tobacco and ECs in the Spanish population, specifically among EC users and tobacco smokers. As secondary objectives, we analysed the associated factors to dual use and the transition patterns between dual use, exclusive EC or tobacco use, and cessation.

2.2. Variables

Dual use was defined as individuals who use ECs and smoke tobacco, either daily and/or within the past 30 days.

Conventional tobacco use was defined as smoking traditional tobacco products daily and/or within the past 30 days.

EC use was defined as daily consumption and/or use within the past 30 days.

Sociodemographic: Sex, age, educational level, employment status, income level.

Perceived health status: Very good/good, average and bad/very bad.

2.3. Data Collection

The Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain (EDADES) is overseen by the Government Delegation for the National Drug Plan (DGPNSD) and collaborates closely with Spain’s regions. This survey is conducted every two years since its inception in 1995, producing fifteen surveys until 2024, enabling the study of trends in the prevalence of alcohol, tobacco, sedative-hypnotics, opiates, and illicit psychoactive drugs use. The survey also collects information on a number of different topics related to drug use, including user profiles, public perception of the risks associated with certain consumption behaviours, perceived availability of different psychoactive substances, awareness of the issue, and other relevant factors. The data is available under request, by the Ministry of Health website upon request for research purposes.

Variables related to tobacco and EC use were selected from the survey (

Table S1.)

2.4. Data Analysis

Sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle factors were described using frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables, and their median with interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables, due to the non-normal distribution of the data.

A combined variable, dual use, was created to represent participants who reported using ECs and conventional tobacco within the past 30 days.

The prevalence of dual consumption was calculated, followed by a bivariate analysis comparing dual users with those who exclusively smoke conventional tobacco and those who exclusively use ECs. The Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for quantitative variables, and Pearson's chi-squared test was used for categorical variables.

A multinomial logistic regression model was conducted for explanatory variables that showed a significant association.

A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance in all analyses conducted in the study. For the analysis, theR-Studio (version 4.4.2) software was used [

22].

3. Results

The 2022 EDADES survey included 26,337 participants aged 15–64, of whom 38% (n = 10,003) reported daily use of conventional tobacco and/or ECs in the past 30 days. 57.1% were men with a median age of 37 [IQR: 26.0-48.0] years. The majority had completed secondary education (74.3%), were employed (62.3%), earned between €1,500 and €2,499 (30.6%), and rated their health status as very good or good (83.5%). Among all smokers and EC users, 94% (n = 9,411) only smoked conventional tobacco, 4.09% (n = 409) were dual users, and 2% (n = 183) only used ECs.

3.1. Prevalence and Characteristics of Dual Consumers

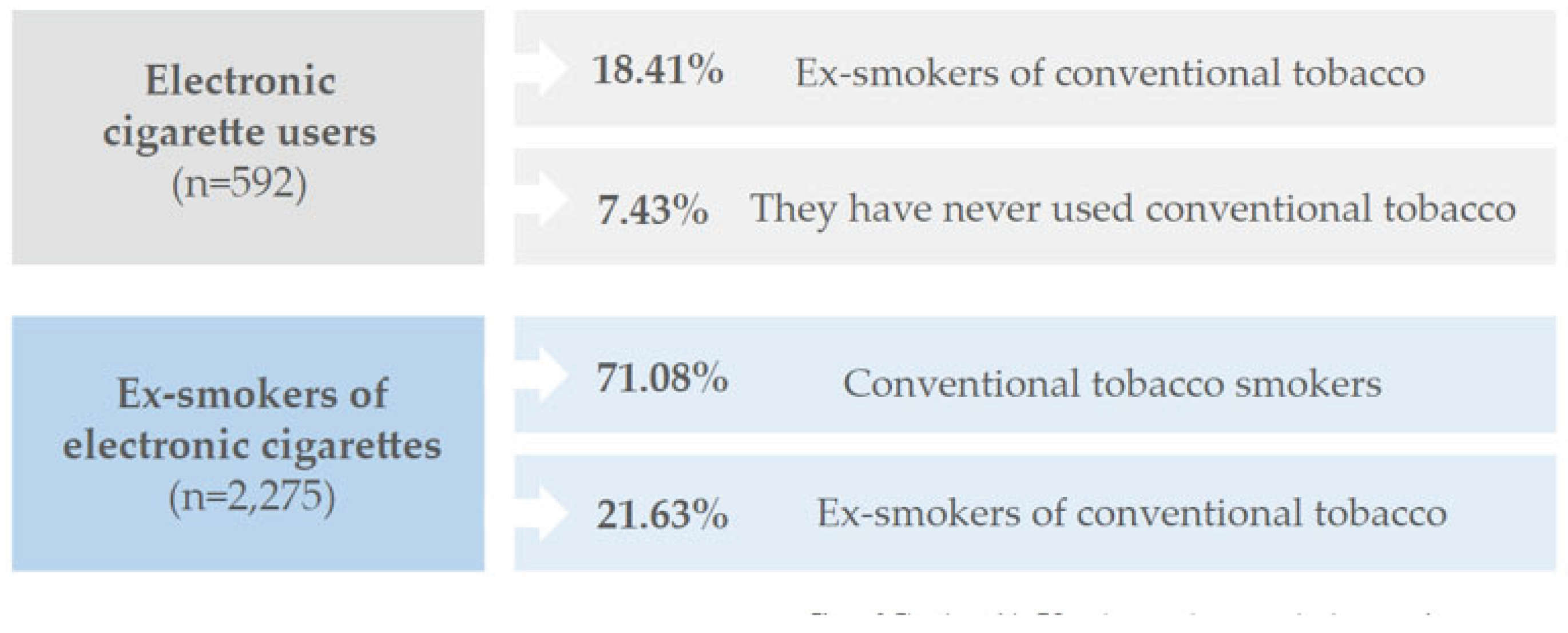

The prevalence of dual users in the population was 1.55% (95%CI: 1.40-1.70), and among all smokers (n=10,003), 4.09% (n = 409) were dual users. Fifty-three percent of dual users were men, with a median age of 29 [IQR: 22.0-40.0] years. 75.1% had completed secondary education, 53.3% were employed, and 22.0% had monthly incomes ranging from €1,500 to €2,499. Among all EC users, 69.08% (95% CI: 66.1-73.5%) were dual users of EC and combustible tobacco, 18.41% were former conventional tobacco smokers, and 7.43% had never smoked tobacco.

Compared to those who exclusively consume conventional tobacco or ECs, dual users were more likely to be economically inactive (23.2% vs. 20.9% vs. 14.9%) and to have an income below €999 (11.1% vs. 7.2% vs. 3.9%). Among dual users, 15.9% reported a fair perceived health status, compared to 4.4% of exclusive EC users and 14.1% of exclusive conventional tobacco users; and a perceived health status of poor or very poor in 3.2% vs 0% vs 2.0% of cases (

Table 1).

3.2. Impact of Factors Associated with EC Use and Dual Use

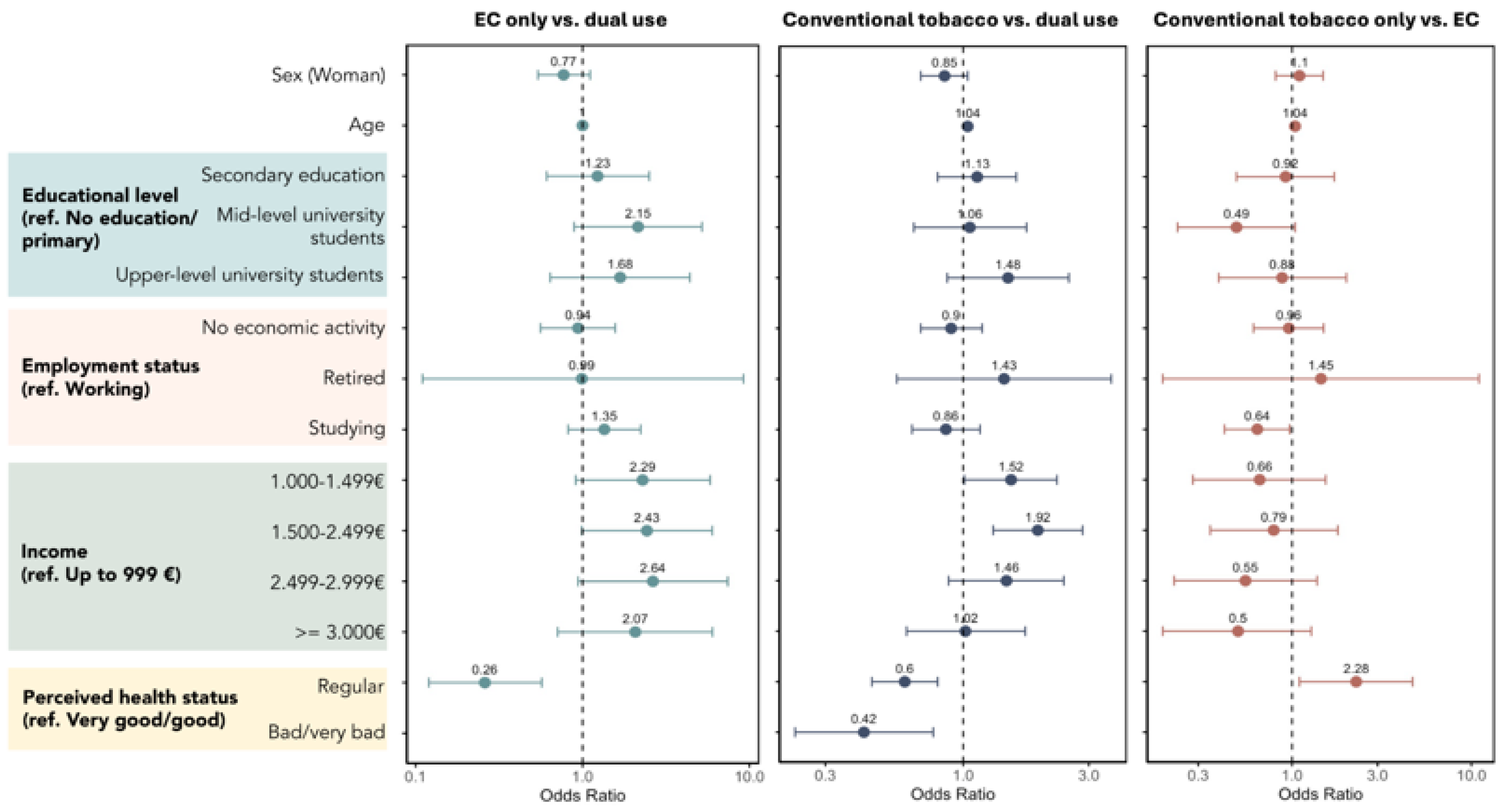

Being a dual user was associated with a 'fair' perceived health status compared to exclusive e-cigarette users, OR of 0.26 (95% CI: 0.12–0.57).

Comparing exclusive tobacco users to dual users, we find that with each additional year of age, the likelihood of using only tobacco increased by 4%, OR 1.04 (IC 95%: 1.03-1.05) compared to dual consumption. Having an income between €1,000–1,499 and €1,500–2,499 was associated with exclusive tobacco use compared to dual use: OR 1.52 (IC 95%: 1.01-2.27) and 1.92 (IC 95%: 1.30-2.84), respectively. Dual users reported a perceived health status of average, (OR) of 0.60 (IC 95%: 0.45-0.80); and bad/very bad (OR) of 0.42 (IC 95%: 0.23-0.77) with respect to exclusive tobacco consumption.

Similarly, with each additional year of age, the likelihood of being an exclusive tobacco user rather than an exclusive EC user increased by 4%, (OR) of 1.04 (IC 95%: 1.02-1.06). Being a student was associated with exclusive EC use compared with only consuming tobacco (OR) of 0.64 (IC 95%: 0.42-0.97). A 'fair' perceived health status was associated to exclusive tobacco when comparing to 'very good/good' perceived health status, OR 2.28 (95% CI: 1.10–4.70)

Figure 1.

Factors associated with dual smoking compared to EC-only and tobacco-only use: (a) EC smoking versus to dual smoking; (b) conventional tobacco smoking versus dual smoking; (c) conventional tobacco smoking versus EC smoking.

Figure 1.

Factors associated with dual smoking compared to EC-only and tobacco-only use: (a) EC smoking versus to dual smoking; (b) conventional tobacco smoking versus dual smoking; (c) conventional tobacco smoking versus EC smoking.

Table S2. Impact of sociodemographic factors and lifestyle based on type of consumption: EC use versus dual use, conventional tobacco use versus dual use, and conventional tobacco use versus EC use.

3.3. Changes in E-Cigarette Smokers

Among the total number of EC users (n=592) in the surveys, 18.41% were former conventional tobacco smokers, and 7.43% had never tried conventional tobacco. Similarly, the survey included 2,275 former EC users, of whom 22% had completely quitted both EC and tobacco. Among former EC users, 1617 (71.08%) now exclusively smoked conventional tobacco (

Figure 2). Among the total number of tobacco smokers (n=9,820), 16.46% were former EC users, whereas 4.16% (409) were dual users.

4. Discussion

Main findings: According to the National EDADES survey, the prevalence of dual use in the Spanish population is 1.55%. 69.08% (95% CI: 66.1-73.5%) of those who smoke ECs are also conventional tobacco smokers. 4.3% of smokers are dual consumers. Dual users were younger than conventional tobacco smokers, were more likely to be economically inactive, and had lower monthly incomes compared to both conventional tobacco and EC users. 71% of former EC users now smoke conventional tobacco. The likelihood of this change increased with age.

Comparison with Pre-Existing Literature

In Spain, in a 2014 study using data from the Omnibus survey, 10.3% (IC95%: 8.6-12.4) of the Spanish adult population reported having tried EC at least once. Among EC users, 57.2% also smoked combustible tobacco, while 14.8% were former conventional cigarette smokers[

23]. The prevalence of dual use of tobacco and EC varies widely across different studies and populations. Nagel reports a dual use prevalence of 2.3% overall; 3.9% among youth, with 3.6% in men and 1.1% in women[

24]. According to a systematic review[

25], the prevalence of dual use among young people is 4%. In England, the prevalence of dual use rose from 3.5% in 2016 to 5.2% in 2024. Dual smoking among conventional smokers accounts for 34.2%, and the percentage of dual smoking among EC users is around 70%[

17]. According to the PATH survey in the US, up to 20.8% of tobacco smokers also use EC [

26]. In our study, we found the figure to be 4,16%. In Scotland, 5.5% of the population uses EC and 3.6% are dual consumers[

27]. In Poland, 15.2% had used ECs within the last 30 days, while 5.9% reported daily consumption. 10% of nicotine product users engaged in dual use of conventional and electronic cigarettes (while an additional 9% used both conventional cigarettes and heated tobacco products)[

28]. In Sweden, 2% of respondents used ECs; of these, 66.7% were dual users[

29], a figure very similar to that found in the EDADES survey. In China, the prevalence of EC use was 1.6%, of which more than 90% were dual users[

30]. In Korea, up to 85% e-cigarette users also smoked tobacco [

31]

In our analysis, there were no differences between sexes in dual smokers. According to the PATH survey, young people, women, non-Latino whites, and those with higher educational levels were at greater risk for dual consumption[

26].

Another multi-wave analysis of the PATH survey examines sex differences in dual users. These were more often men. Women were more dependent on cigarettes, whereas men were more frequent users of ECs[

32]. Other studies also found that men engage in dual consumption more frequently [

24,

27,

29].

Dual users have greater nicotine dependence, higher alcohol and cannabis use, and are more likely to have used non-medical opioids [

33].

In our study, as age increases, the likelihood of exclusively using combustible tobacco also increases. Other studies confirm a lower dual consumption with age, although dual smokers are not usually the youngest but rather in their twenties or early thirties[

17,

24,

26,

27].

While some studies, such as Assari’s, find no link between dual consumption and economic status, they do observe a correlation with higher education levels, others, such as Hedman’s, report different findings. In China and Korea, EC consumption is associated with higher economic levels [

30,

31], unlike in the United Kingdom[

17,

27].

In our study, only 1.43% of ex-smokers reported using ECs. The prevalence of vaping among individuals in the UK who quit conventional tobacco smoking over one year ago has risen from 1.9% in 2013 to 20.4% in 2024[

34].

71% of former vapers now smoke combustible tobacco, indicating a harmful shift—either due to new users taking up smoking or because ECs fail to support smoking cessation. The older average age of former EC users who now smoke suggests that a significant portion may have turned to vaping as an attempt to quit that ultimately failed. Based on an analysis of the PATH survey in the U.S., Kaplan[

13] estimates that for every beneficial transition—such as switching from conventional cigarettes to exclusive EC use or quitting smoking while using EC as a support tool—there were 2.15 harmful transitions (starting to use ECs or switching from ECs to exclusively smoking combustible cigarettes).

In Spain, an analysis of the ESTUDES survey[

35] found that individuals who had ever used ECs were nearly twice as likely to smoke conventional cigarettes further down the line. Dual smokers tend to consume more cigarettes daily, use nicotine-containing ECs more frequently, and start smoking at a younger age. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews indicate that EC use is linked to an increased likelihood of progressing to regular cigarette smoking[

15,

16,

36,

37].

Dual smokers reported poorer health compared to those who smoke only tobacco or only ECs. Dual use has been associated with a higher risk of respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, as well as cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, along with poorer overall health outcomes[

19,

20].

Strengths and Limitations

The EDADES surveys are designed to provide a highly representative sample of the Spanish population. This is supported by its large sample size and use of random sampling, making the study more accurate while minimising selection bias.

However, it is important to consider the limitations inherent to cross-sectional surveys. Although the surveys are conducted by trained researchers, responses may be affected by information bias, particularly due to the subjective nature of certain questions—such as income level, ex-smoker status, and self-perceived health status. Similarly, we cannot draw causal conclusions about changes in smoking habits among former EC users, as their motivations and decision-making factors were not documented.

Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first study of a Spanish population to estimate the prevalence of dual smoking, defined as the use of both ECs and conventional tobacco within the past 30 days. Our findings suggest that, despite ECs being promoted as a way to quit conventional tobacco[

10], most EC users are dual users, and 71% of former EC users have reverted to smoking only conventional tobacco. Therefore, legislation and future prevention and health promotion policies should take into account the behaviours of smokers and nicotine users at a population level.

Futures Research

Further studies are needed to look into the factors and motivations behind switching from EC to conventional tobacco, dual use, and the proportion of smokers who quit nicotine entirely using ECs. These motivations could be addressed through survey questions, or by conducting targeted questionnaires and qualitative research among populations at the heart of these shifts in nicotine consumption. Similarly, it is of utmost importance to tackle the increasing use of ECs and dual use—particularly among specific age groups—by conducting studies that assess potential interventions to curb these behaviours.

5. Conclusions

In 2022, dual users of ECs and tobacco accounted for 4% of smokers in the Spanish population. Dual users tend to be younger than conventional tobacco smokers and, compared to exclusive EC users, they have lower income levels and poorer self-perceived health status. Despite tobacco companies promoting electronic cigarettes as a way to stop smoking, 71% of former EC users have gone back to smoking conventional tobacco.

Although traditional tobacco use is waning, it is of utmost importance to address the rising prevalence of EC and dual use—particularly among specific age groups—through studies that assess potential interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org,.

Table S1: Selected variables from the EDADES survey;

Table S2. Impact of sociodemographic factors and lifestyle based on type of consumption_ EC use versus dual use, conventional tobacco use versus dual use, and conventional tobacco use versus EC use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.L.; methodology, C.M.L, J.R.S, and I.G.L.; software, JRS.; validation, C.M.L, J.R.S, and I.G.L.; formal analysis, J.R.S; investigation, C.M.L, J.R.S, and I.G.L.; resources, C.M.L.; data curation, J.R.S; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.L, J.R.S, and I.G.L..; writing—review and editing, C.M.L, J.R.S, and I.G.L..; visualization, C.M.L, J.R.S, and I.G.L.; supervision, C.M.L, J.R.S, and I.G.L.; project administration, C.M.L.; funding acquisition, C.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, within the Red de Investigación en Cronicidad, Atención Primaria y Promoción de la Salud (RICAPPS), grant number RD21/0016/0026.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues in the Primary Care Research Unit in Madrid, for their guidance and help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EC |

Electronic cigarrete use |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| NHS |

National Health Surveys |

| FCTC |

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control |

| EDADES |

Survey on Alcohol and Other Drugs in the General Population in Spain |

| DGPNSD |

Government Delegation for the National Drug Plan |

References

- Drope J, Hamill S, Chaloupka F, Guerrero C, Lee HM, Mirza M, Mouton A, Murukutla N, Ngo A, Perl R, Rodriguez-Iglesias G, Schluger N, Siu E, Vulovic V. The Tobacco Atlas. New York: Vital Strategies and Tobacconomics; 2022.

- Montes Martínez A, Pérez-Ríos M, Ortiz C, Gtt-See, Galán Labaca I. Cambios en el abandono del consumo de tabaco en España, 1987-2020. Medicina Clínica [Internet]. 2023 Mar [cited 2025 May 18];160(6):237–44. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0025775322004146.

- World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

- Ley 28/2005, de 26 de diciembre, de medidas sanitarias frente al tabaquismo y reguladora de la venta, el suministro, el consumo y la publicidad de los productos del tabaco.(BOE 27/12/2005) actualizada Ley 42/2010, de 30 de diciembre. 2005 [cited 2013 Jun 17]; Available from: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2005/BOE-A-2005-21261-consolidado.pdf.

- Ley 42/2010, de 30 de diciembre, por la que se modifica la Ley 28/2005, de 26 de diciembre, de medidas sanitarias frente al tabaquismo y reguladora de la venta, el suministro, el consumo y la publicidad de los productos del tabaco [Internet]. BOE; 2010 [cited 2013 Jun 17]. Available from: http://www.judicatura.com/Legislacion/3477.pdf.

- Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad. EDADES 2024. Encuesta sobre alcohol y otras drogas en España (EDADES) 1995-2024. 2024.

- Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad. ESTUDES 2023. Encuesta sobre uso de drogas en enseñanzas secundarias en España (ESTUDES). 1994-2023. 2023.

- Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and related products - junio 2024 - - Eurobarometer survey [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 24]. Available from: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2995.

- Jerzyński T, Stimson GV. Estimation of the global number of vapers: 82 million worldwide in 2021. DHS [Internet]. 2023 May 25 [cited 2025 May 24];24(2):91–103. Available from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/DHS-07-2022-0028/full/html. [CrossRef]

- Lindson N, Butler AR, McRobbie H, Bullen C, Hajek P, Wu AD, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Central Editorial Service, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2025 Jan 29 [cited 2025 May 24];2025(1). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub9. [CrossRef]

- Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine [Internet]. 2016 Feb [cited 2020 Nov 8];4(2):116–28. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213260015005214. [CrossRef]

- Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-Cigarette Use and Adult Cigarette Smoking Cessation: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Feb [cited 2024 Oct 10];111(2):230–46. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan B, Tseng TY, Hardesty JJ, Czaplicki L, Cohen JE. Beneficial and Harmful Tobacco-Use Transitions Associated With ENDS in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine [Internet]. 2025 May [cited 2025 May 24];68(5):896–904. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S074937972500025X. [CrossRef]

- Berry KM, Fetterman JL, Benjamin EJ, Bhatnagar A, Barrington-Trimis JL, Leventhal AM, et al. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Subsequent Initiation of Tobacco Cigarettes in US Youths. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2019 Feb 1 [cited 2025 May 24];2(2):e187794. Available from: http://jamanetworkopen.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7794. [CrossRef]

- Baenziger ON, Ford L, Yazidjoglou A, Joshy G, Banks E. E-cigarette use and combustible tobacco cigarette smoking uptake among non-smokers, including relapse in former smokers: umbrella review, systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2025 May 24];11(3):e045603. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045603. [CrossRef]

- Begh R, Conde M, Fanshawe TR, Kneale D, Shahab L, Zhu S, et al. Electronic cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking in young people: A systematic review. Addiction [Internet]. 2025 Jun [cited 2025 May 24];120(6):1090–111. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16773. [CrossRef]

- Jackson SE, Cox S, Shahab L, Brown J. Trends and patterns of dual use of combustible tobacco and e-cigarettes among adults in England: A population study, 2016–2024. Addiction [Internet]. 2025 Apr [cited 2025 May 24];120(4):608–19. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.16734. [CrossRef]

- Kundu A, Feore A, Sanchez S, Abu-Zarour N, Sutton M, Sachdeva K, et al. Cardiovascular health effects of vaping e-cigarettes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart [Internet]. 2025 Feb 26 [cited 2025 May 24];heartjnl-2024-325030. Available from: https://heart.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/heartjnl-2024-325030. [CrossRef]

- Pisinger C, Rasmussen SKB. The Health Effects of Real-World Dual Use of Electronic and Conventional Cigarettes versus the Health Effects of Exclusive Smoking of Conventional Cigarettes: A Systematic Review. IJERPH [Internet]. 2022 Oct 21 [cited 2025 May 24];19(20):13687. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/20/13687. [CrossRef]

- Glantz SA, Nguyen N, Oliveira Da Silva AL. Population-Based Disease Odds for E-Cigarettes and Dual Use versus Cigarettes. NEJM Evidence [Internet]. 2024 Feb 27 [cited 2024 Oct 10];3(3). Available from: https://evidence.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/EVIDoa2300229. [CrossRef]

- Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas. Ministerio de Sanidad. Encuesta sobre alcohol y otras drogas en España (EDADES) 1995-2022. 2023.

- R: The R Project for Statistical Computing [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 24]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Lidón-Moyano C, Martínez-Sánchez JM, Fu M, Ballbè M, Martín-Sánchez JC, Fernández E. Prevalencia y perfil de uso del cigarrillo electrónico en España (2014). Gaceta Sanitaria [Internet]. 2016 Nov [cited 2025 May 18];30(6):432–7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0213911116300395.

- Nagel C, Hugueley B, Cui Y, Nunez DM, Kuo T, Kuo AA. Predictors of Dual E-Cigarette and Cigarette Use. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice [Internet]. 2022 May [cited 2025 May 24];28(3):243–7. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001491. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Lee S, Chun J. An International Systematic Review of Prevalence, Risk, and Protective Factors Associated with Young People’s E-Cigarette Use. IJERPH [Internet]. 2022 Sep 14 [cited 2025 May 24];19(18):11570. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/18/11570.

- Assari S, Sheikhattari P. Social Epidemiology of Dual Use of Electronic and Combustible Cigarettes Among U.S. Adults: Insights from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. GJCD [Internet]. 2024 Nov 19 [cited 2025 May 24];3(1):13–23. Available from: https://www.scipublications.com/journal/index.php/GJCD/article/view/1131. [CrossRef]

- Adebisi YA, Bafail DA, Oni OE. Prevalence, demographic, socio-economic, and lifestyle factors associated with cigarette, e-cigarette, and dual use: evidence from the 2017–2021 Scottish Health Survey. Intern Emerg Med [Internet]. 2024 Nov [cited 2025 May 24];19(8):2151–65. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11739-024-03716-2. [CrossRef]

- Jankowski M, Grudziąż-Sękowska J, Kamińska A, Sękowski K, Wrześniewska-Wal I, Moczeniat G, et al. A 2024 nationwide cross-sectional survey to assess the prevalence of cigarette smoking, e-cigarette use and heated tobacco use in Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health [Internet]. 2024 Sep 10 [cited 2025 May 24];37(3):271–86. Available from: https://ijomeh.eu/A-2024-nationwide-cross-sectional-survey-to-assess-the-prevalence-of-cigarette-smoking,188344,0,2.html.

- Hedman L, Backman H, Stridsman C, Bosson JA, Lundbäck M, Lindberg A, et al. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use With Smoking Habits, Demographic Factors, and Respiratory Symptoms. JAMA Netw Open [Internet]. 2018 Jul 20 [cited 2025 May 24];1(3):e180789. Available from: http://jamanetworkopen.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0789. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Z, Zhang M, Wu J, Xu X, Yin P, Huang Z, et al. E-cigarette use among adults in China: findings from repeated cross-sectional surveys in 2015–16 and 2018–19. The Lancet Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Dec [cited 2025 May 24];5(12):e639–49. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2468266720301456. [CrossRef]

- Kim CY, Paek YJ, Seo HG, Cheong YS, Lee CM, Park SM, et al. Dual use of electronic and conventional cigarettes is associated with higher cardiovascular risk factors in Korean men. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2020 Mar 27 [cited 2025 May 24];10(1):5612. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-62545-3. [CrossRef]

- Klemperer EM, Kock L, Feinstein MJP, Coleman SRM, Gaalema DE, Higgins ST. Sex differences in tobacco use, attempts to quit smoking, and cessation among dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes: Longitudinal findings from the US Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Preventive Medicine [Internet]. 2024 Aug [cited 2025 May 24];185:108024. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091743524001798.

- Chavez J, Smit T, Olofsson H, Mayorga NA, Garey L, Zvolensky MJ. Substance Use among Exclusive Electronic Cigarette Users and Dual Combustible Cigarette Users: Extending Work to Adult Users. Substance Use & Misuse [Internet]. 2021 May 12 [cited 2025 May 24];56(6):888–96. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10826084.2021.1899234. [CrossRef]

- Jackson SE, Brown J, Kock L, Shahab L. Prevalence and uptake of vaping among people who have quit smoking: a population study in England, 2013-2024. BMC Med [Internet]. 2024 Nov 21 [cited 2025 May 24];22(1):503. Available from: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-024-03723-2. [CrossRef]

- Aonso-Diego G, Secades-Villa R, García-Pérez Á, Weidberg S, Fernández-Hermida JR. Association between e-cigarette and conventional cigarette use among Spanish adolescents. Adicciones. 2024 Jun 1;36(2):199–206. [CrossRef]

- Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, Leventhal AM, Unger JB, Gibson LA, et al. Association Between Initial Use of e-Cigarettes and Subsequent Cigarette Smoking Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr [Internet]. 2017 Aug 1 [cited 2025 May 24];171(8):788. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/fullarticle/2634377.

- Kim MM, Steffensen I, Miguel RTD, Babic T, Carlone J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between e-cigarette use among non-tobacco users and initiating smoking of combustible cigarettes. Harm Reduct J [Internet]. 2024 May 22 [cited 2025 May 24];21(1):99. Available from: https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-024-01013-x. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).