Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Social Defeat Stress (SDS)

2.3. Mechanical and Thermal Threshold Evaluation

2.4. Open-Field and Light-and-Dark Tests

2.5. Immunostaining

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

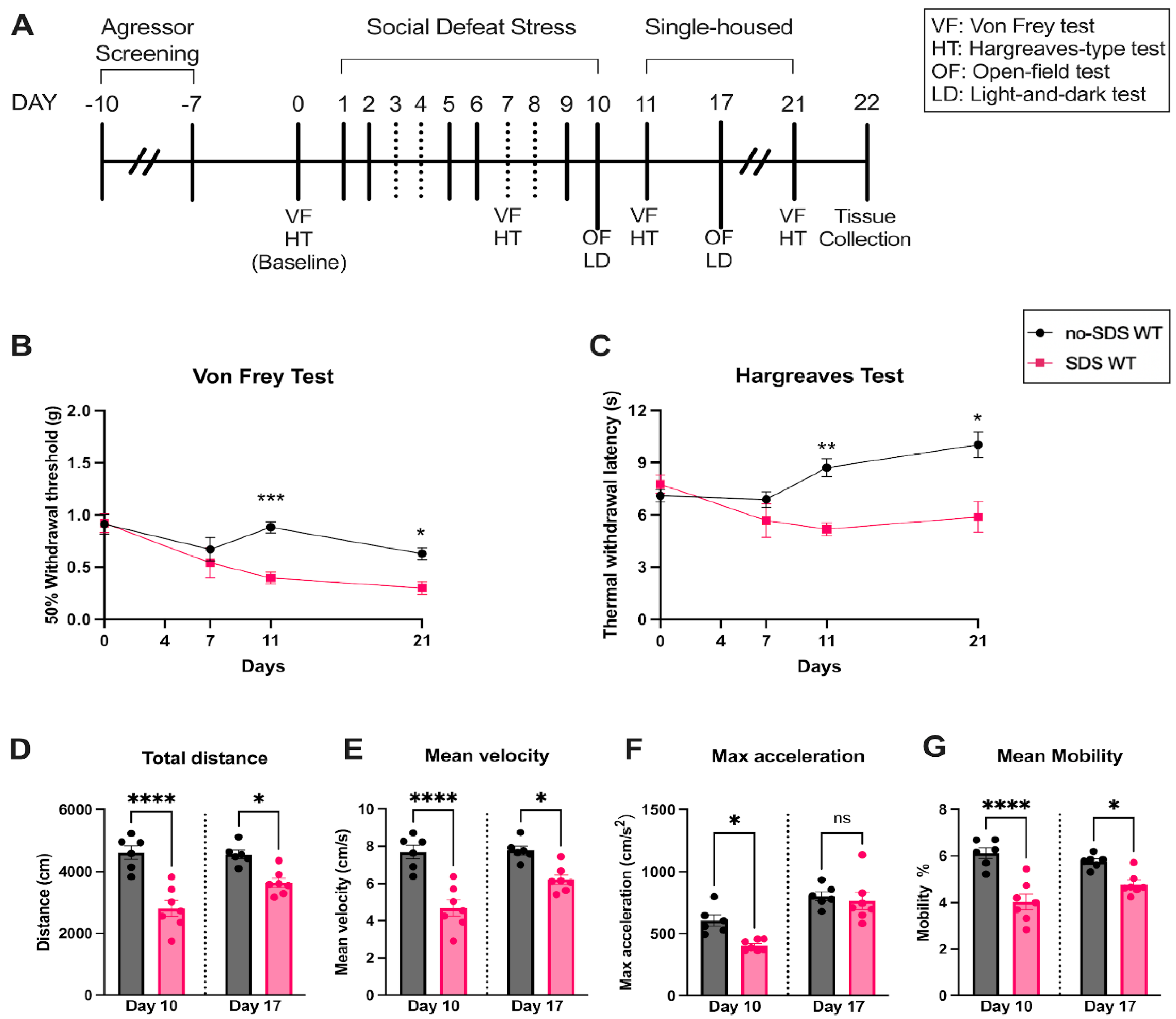

3.1. SDS Induces Persistent Mechanical Allodynia and Thermal Hyperalgesia

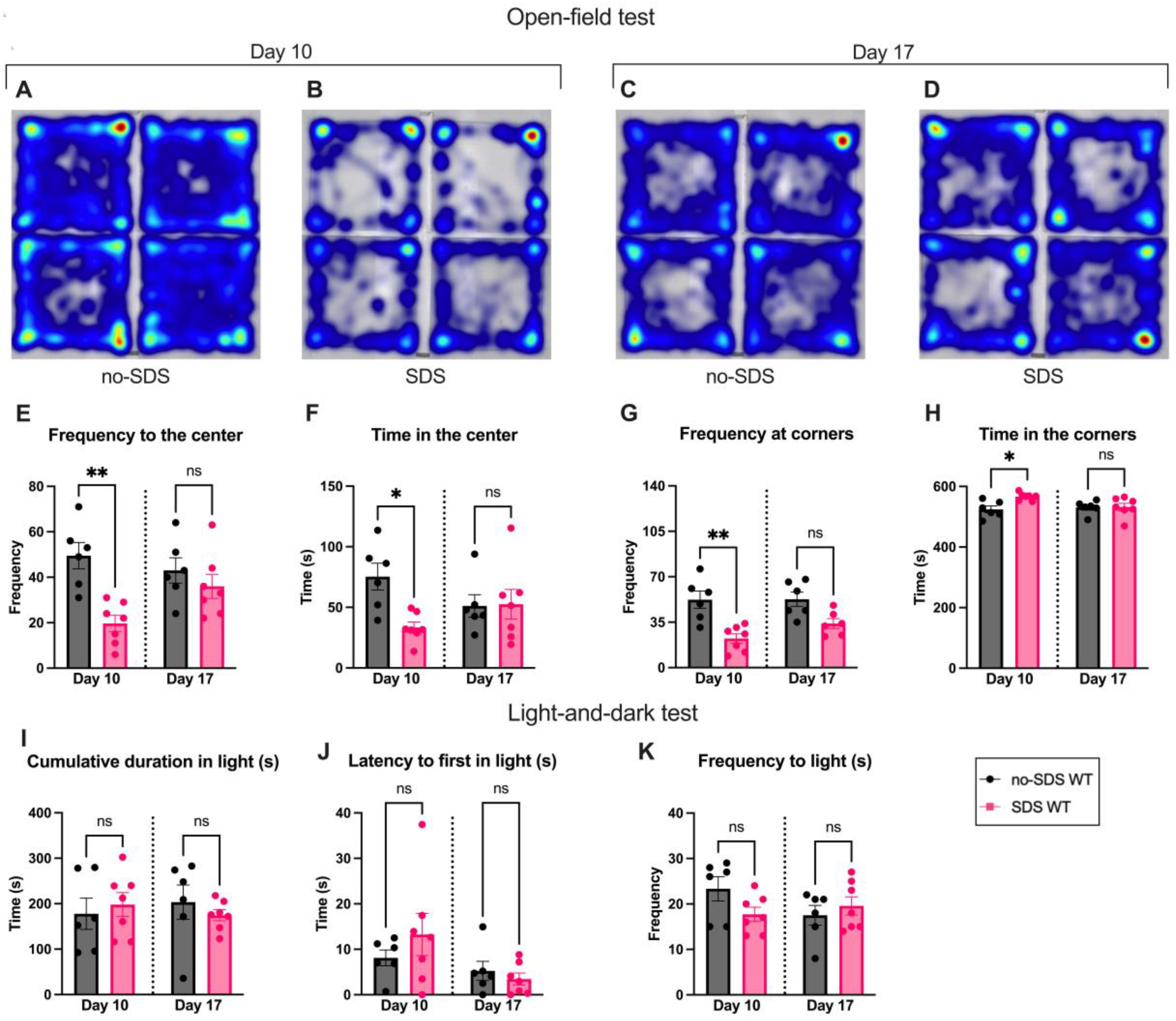

3.2. SDS Induces Long-Term Locomotor Changes and Short-Term Anxiety-Like Behavior

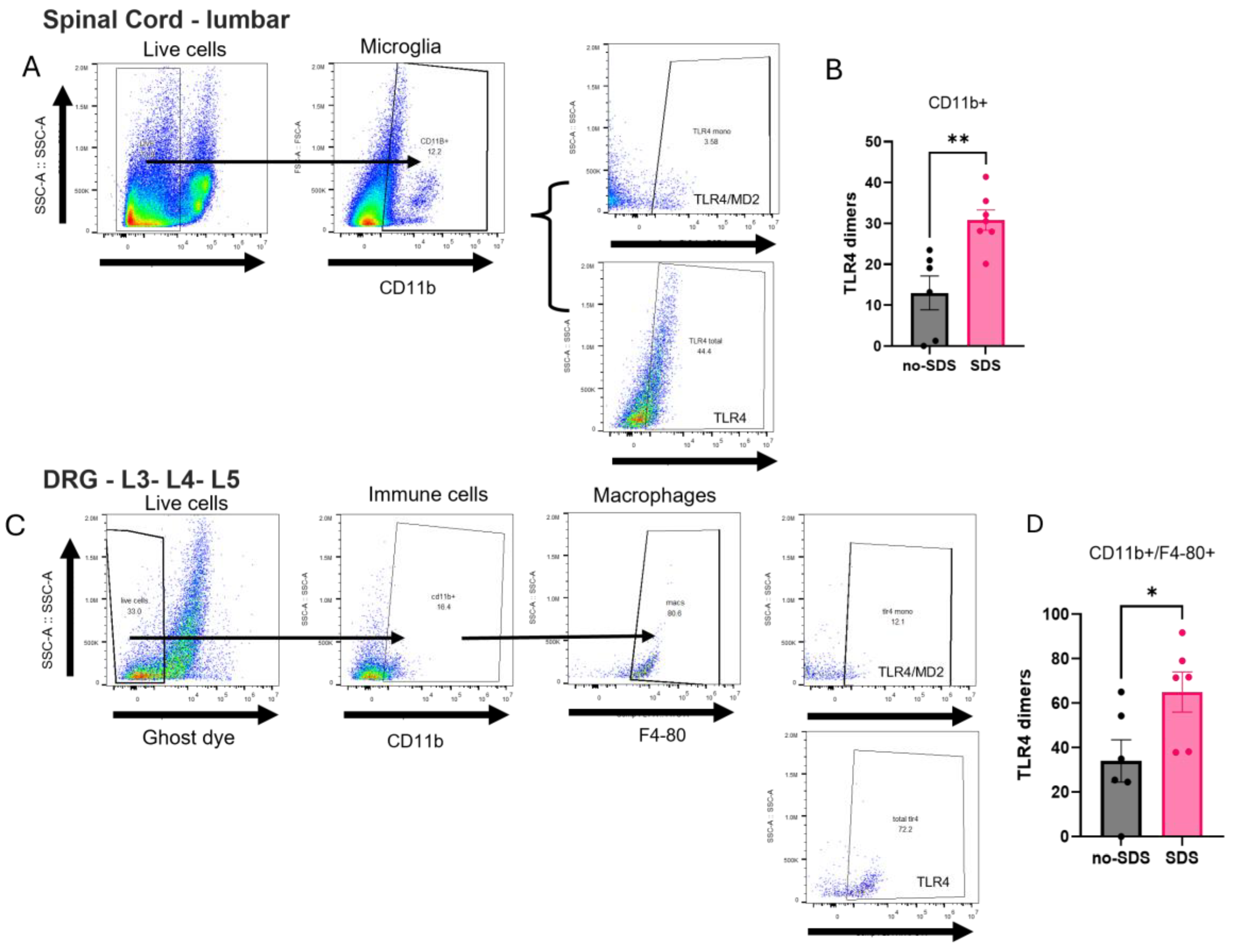

3.3. TLR4 Activation in Spinal Cord, Dorsal Root Ganglia, and Prefrontal Cortex After SDS

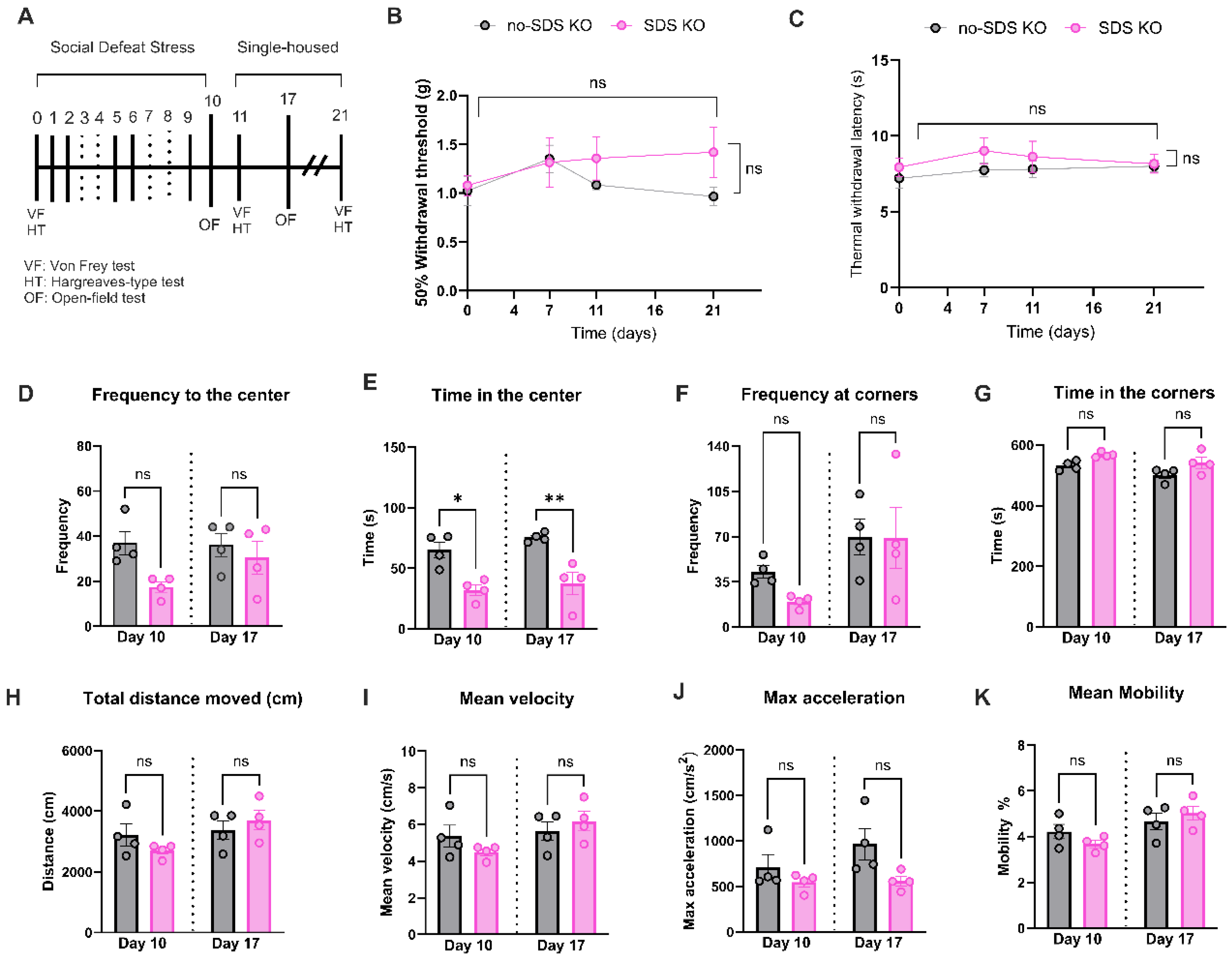

3.4. Genetic Ablation of TLR4 Expression Prevented Pain Phenotype Induced by SDS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McEwen, B.S. Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, T.B.; Silva, B.A.; Perova, Z.; Marrone, L.; Masferrer, M.E.; Zhan, Y.; Kaplan, A.; Greetham, L.; Verrechia, V.; Halman, A.; et al. Prefrontal cortical control of a brainstem social behavior circuit. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Nasca, C.; Gray, J.D. Stress Effects on Neuronal Structure: Hippocampus, Amygdala, and Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannibal, K.E.; Bishop, M.D. Chronic Stress, Cortisol Dysfunction, and Pain: A Psychoneuroendocrine Rationale for Stress Management in Pain Rehabilitation. Physical Therapy 2014, 94, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, E.; Hannibal, M.D.B. Chronic Stress, Cortisol Dysfunction, and Pain: A Psychoneuroendocrine Rationale for Stress Management in Pain Rehabilitation. Physical therapy 2014, 94, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J.J.; Lam, P.H.; Chen, E.; Miller, G.E. Psychological Stress During Childhood and Adolescence and Its Association With Inflammation Across the Lifespan: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol Bull 2022, 148, 27–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.H.; Maletic, V.; Raison, C.L. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2009, 65, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atrooz, F.; Alkadhi, K.A.; Salim, S. Understanding stress: Insights from rodent models. Curr Res Neurobiol 2021, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, S.A.; Covington, H.E., 3rd; Berton, O.; Russo, S.J. A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat Protoc 2011, 6, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piardi, L.N.; Pagliusi, M.; Bonet, I.; Brandao, A.F.; Magalhaes, S.F.; Zanelatto, F.B.; Tambeli, C.H.; Parada, C.A.; Sartori, C.R. Social stress as a trigger for depressive-like behavior and persistent hyperalgesia in mice: study of the comorbidity between depression and chronic pain. J Affect Disord 2020, 274, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Takata, K.; Yamada, D.; Usuda, H.; Wada, K.; Tada, M.; Mishima, Y.; Ishihara, S.; Horie, S.; Saitoh, A.; et al. Juvenile social defeat stress exposure favors in later onset of irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms in male mice. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 16276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R.; Talih, M.; Soares, S.; Fraga, S. Bullying Involvement and Physical Pain Between Ages 10 and 13 Years: Reported History and Quantitative Sensory Testing in a Population-Based Cohort. J Pain 2024, 25, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, T.J.; Hayden, J.A.; Lewinson, R.; Mahood, Q.; Pepler, D.; Katz, J. A Systematic Review of the Prospective Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Pain. J Pain Res 2021, 14, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navia-Pelaez, J.M.; Borges Paes Lemes, J.; Gonzalez, L.; Delay, L.; Dos Santos Aggum Capettini, L.; Lu, J.W.; Goncalves Dos Santos, G.; Gregus, A.M.; Dougherty, P.M.; Yaksh, T.L.; et al. AIBP regulates TRPV1 activation in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy by controlling lipid raft dynamics and proximity to TLR4 in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Pain 2023, 164, e274–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woller, S.A.; Ravula, S.B.; Tucci, F.C.; Beaton, G.; Corr, M.; Isseroff, R.R.; Soulika, A.M.; Chigbrow, M.; Eddinger, K.A.; Yaksh, T.L. Systemic TAK-242 prevents intrathecal LPS evoked hyperalgesia in male, but not female mice and prevents delayed allodynia following intraplantar formalin in both male and female mice: The role of TLR4 in the evolution of a persistent pain state. Brain Behav Immun 2016, 56, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, K.; Woller, S.A.; Miller, Y.I.; Yaksh, T.L.; Wallace, M.; Beaton, G.; Chakravarthy, K. Targeting toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4)-an emerging therapeutic target for persistent pain states. Pain 2018, 159, 1908–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.H.; Hwangbo, C. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4): new insight immune and aging. Immun Ageing 2023, 20, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Kosturakis, A.K.; Jawad, A.B.; Dougherty, P.M. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling contributes to Paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pain 2014, 15, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianson, C.A.; Dumlao, D.S.; Stokes, J.A.; Dennis, E.A.; Svensson, C.I.; Corr, M.; Yaksh, T.L. Spinal TLR4 mediates the transition to a persistent mechanical hypersensitivity after the resolution of inflammation in serum-transferred arthritis. Pain 2011, 152, 2881–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, K.; Takeuchi, O.; Kawai, T.; Sanjo, H.; Ogawa, T.; Takeda, Y.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S. Cutting Edge: Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)-Deficient Mice Are Hyporesponsive to Lipopolysaccharide: Evidence for TLR4 as the Lps Gene Product. The Journal of Immunology 1999, 162, 3749–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliusi, M.O.F., Jr.; Sartori, C.R. Social Defeat Stress (SDS) in Mice: Using Swiss Mice as Resident. Bio Protoc 2019, 9, e3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaplan, S.R.; Bach, F.W.; Pogrel, J.W.; Chung, J.M.; Yaksh, T.L. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 1994, 53, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirig, D.M.; Salami, A.; Rathbun, M.L.; Ozaki, G.T.; Yaksh, T.L. Characterization of variables defining hindpaw withdrawal latency evoked by radiant thermal stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 1997, 76, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibenhener, M.L.; Wooten, M.C. Use of the Open Field Maze to measure locomotor and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J Vis Exp 2015, e52434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourin, M.; Hascoet, M. The mouse light/dark box test. Eur J Pharmacol 2003, 463, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navia-Pelaez, J.M.; Choi, S.H.; Dos Santos Aggum Capettini, L.; Xia, Y.; Gonen, A.; Agatisa-Boyle, C.; Delay, L.; Goncalves Dos Santos, G.; Catroli, G.F.; Kim, J.; et al. Normalization of cholesterol metabolism in spinal microglia alleviates neuropathic pain. J Exp Med 2021, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, C.G.; Geha, P. Chronic Pain and Chronic Stress: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlack, R.; Peerenboom, N.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Beyer, A.K. The effects of mental health problems in childhood and adolescence in young adults: Results of the KiGGS cohort. J Health Monit 2021, 6, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. Mental disorders. Available online: (accessed on 01/16/2025).

- Quintero, L.; Cuesta, M.C.; Silva, J.A.; Arcaya, J.L.; Pinerua-Suhaibar, L.; Maixner, W.; Suarez-Roca, H. Repeated swim stress increases pain-induced expression of c-Fos in the rat lumbar cord. Brain Res 2003, 965, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez-Roca, H.; Silva, J.A.; Arcaya, J.L.; Quintero, L.; Maixner, W.; Pinerua-Shuhaibar, L. Role of mu-opioid and NMDA receptors in the development and maintenance of repeated swim stress-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Behav Brain Res 2006, 167, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, L.; Cardenas, R.; Suarez-Roca, H. Stress-induced hyperalgesia is associated with a reduced and delayed GABA inhibitory control that enhances post-synaptic NMDA receptor activation in the spinal cord. Pain 2011, 152, 1909–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Giorgi, V.; Marotto, D.; Atzeni, F. Fibromyalgia: an update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2020, 16, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, N.N.; Jiang, H.; Xia, M. Sex-dependent effects of postweaning exposure to an enriched environment on visceral pain and anxiety- and depression-like behaviors induced by neonatal maternal separation. Transl Pediatr 2022, 11, 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ma, Y.; Dong, B.; Hu, B.; He, H.; Jia, J.; Xiong, M.; Xu, T.; Xu, B.; Xi, W. Functional magnetic resonance imaging study on anxiety and depression disorders induced by chronic restraint stress in rats. Behav Brain Res 2023, 450, 114496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, C.M.; Kim, J.K.; Weber, M.D.; Faw, T.D.; McKim, D.B.; Madalena, K.M.; Lerch, J.K.; Basso, D.M.; Humeidan, M.L.; Godbout, J.P.; et al. Microglia Promote Increased Pain Behavior through Enhanced Inflammation in the Spinal Cord during Repeated Social Defeat Stress. J Neurosci 2019, 39, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, G.G.; Jimenez-Andrade, J.M.; Munoz-Islas, E.; Candanedo-Quiroz, M.E.; Cardenas, A.G.; Drummond, B.; Pham, P.; Stilson, G.; Hsu, C.C.; Delay, L.; et al. Role of TLR4 activation and signaling in bone remodeling, and afferent sprouting in serum transfer arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2024, 26, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yang, L.; Rong, W. TLR4 mediates upregulation and sensitization of TRPV1 in primary afferent neurons in 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfate-induced colitis. Mol Pain 2019, 15, 1744806919830018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Yu, S.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, F. Direct binding of Toll-like receptor 4 to ionotropic glutamate receptor N-methyl-D-aspartate subunit 1 induced by lipopolysaccharide in microglial cells N9 and EOC 20. Int J Mol Med 2018, 41, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Lian, Y.J.; Su, W.J.; Peng, W.; Dong, X.; Liu, L.L.; Gong, H.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, C.L.; Wang, Y.X. HMGB1 mediates depressive behavior induced by chronic stress through activating the kynurenine pathway. Brain Behav Immun 2018, 72, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U.; Tracey, K.J. HMGB1 is a therapeutic target for sterile inflammation and infection. Annu Rev Immunol 2011, 29, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berta, T.; Qadri, Y.; Tan, P.H.; Ji, R.R. Targeting dorsal root ganglia and primary sensory neurons for the treatment of chronic pain. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2017, 21, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, C.I.; Tran, T.K.; Fitzsimmons, B.; Yaksh, T.L.; Hua, X.Y. Descending serotonergic facilitation of spinal ERK activation and pain behavior. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 6629–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Kang, D.H.; Jeon, J.; Lee, H.G.; Kim, W.M.; Yoon, M.H.; Choi, J.I. Imbalance in the spinal serotonergic pathway induces aggravation of mechanical allodynia and microglial activation in carrageenan inflammation. Korean J Pain 2023, 36, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinez-Chaparro, B.; Lopez-Santillan, F.J.; Orduna, P.; Granados-Soto, V. Secondary mechanical allodynia and hyperalgesia depend on descending facilitation mediated by spinal 5-HT(4), 5-HT(6) and 5-HT(7) receptors. Neuroscience 2012, 222, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lv, R.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Cao, N.; Gu, B. The serotonin(5-HT)2A receptor is involved in the hypersensitivity of bladder afferent neurons in cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. Eur J Pharmacol 2024, 982, 176909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, E.R.; Carbajal, A.G.; Tian, J.B.; Bavencoffe, A.; Zhu, M.X.; Dessauer, C.W.; Walters, E.T. Serotonin enhances depolarizing spontaneous fluctuations, excitability, and ongoing activity in isolated rat DRG neurons via 5-HT(4) receptors and cAMP-dependent mechanisms. Neuropharmacology 2021, 184, 108408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, D.M.; Allen, C.; Carrive, P. Cardiovascular and behavioral responses to conditioned fear after medullary raphe neuronal blockade. Neuroscience 2008, 153, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).