Submitted:

12 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Chronic Unpredictable Stress CUS

2.4. Behavioral Tests

2.4.1. Open Field Test (OFT)

2.4.2. Tail Suspension Test (TST)

2.5. Hair, Blood and Organ Samples Collection

2.6. Corticosterone Measurement

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

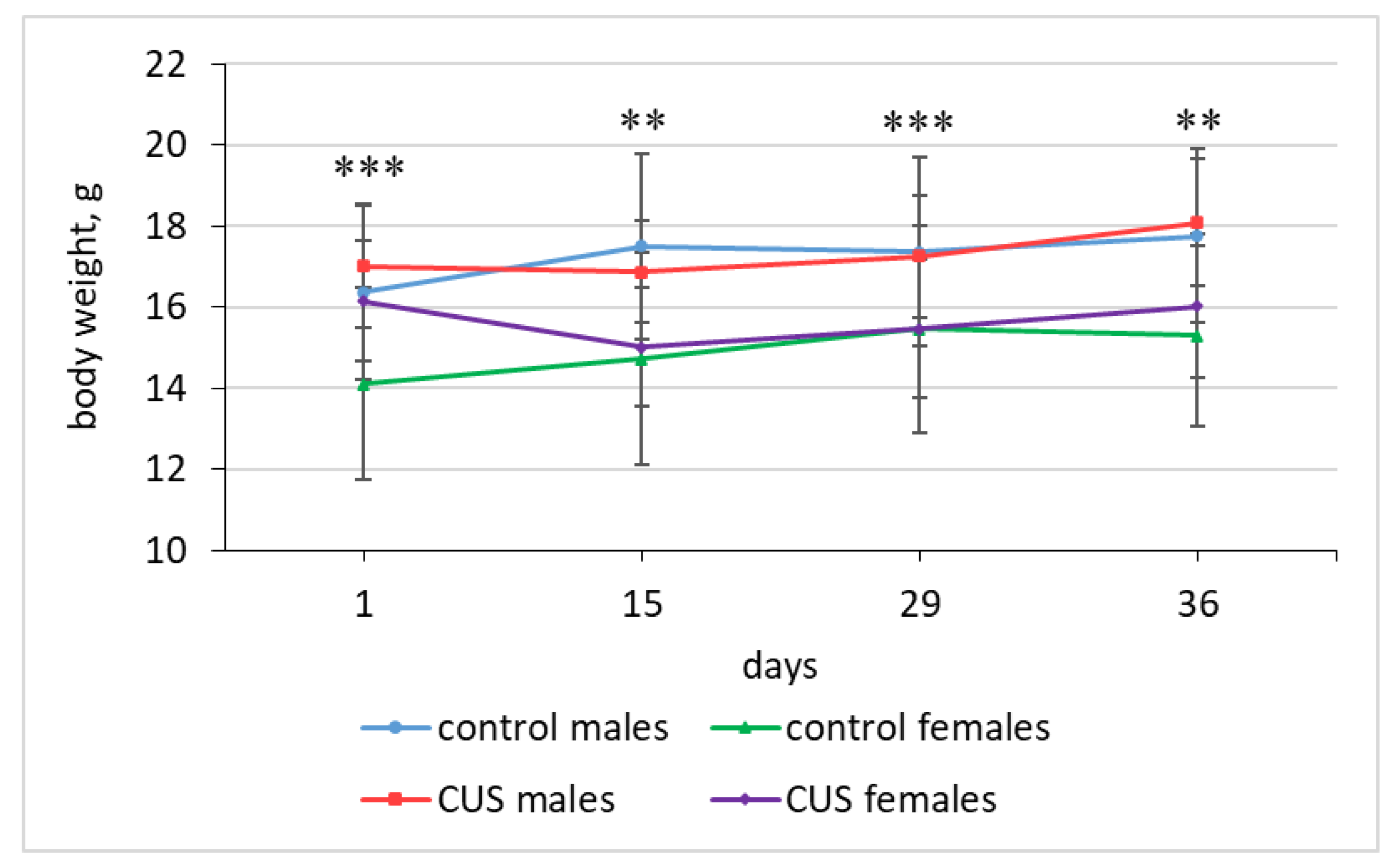

3.1. Body Weight Change

3.2. Post-Mortem Stress-Sensitive Organ Weights

3.3. Behavioral Changes

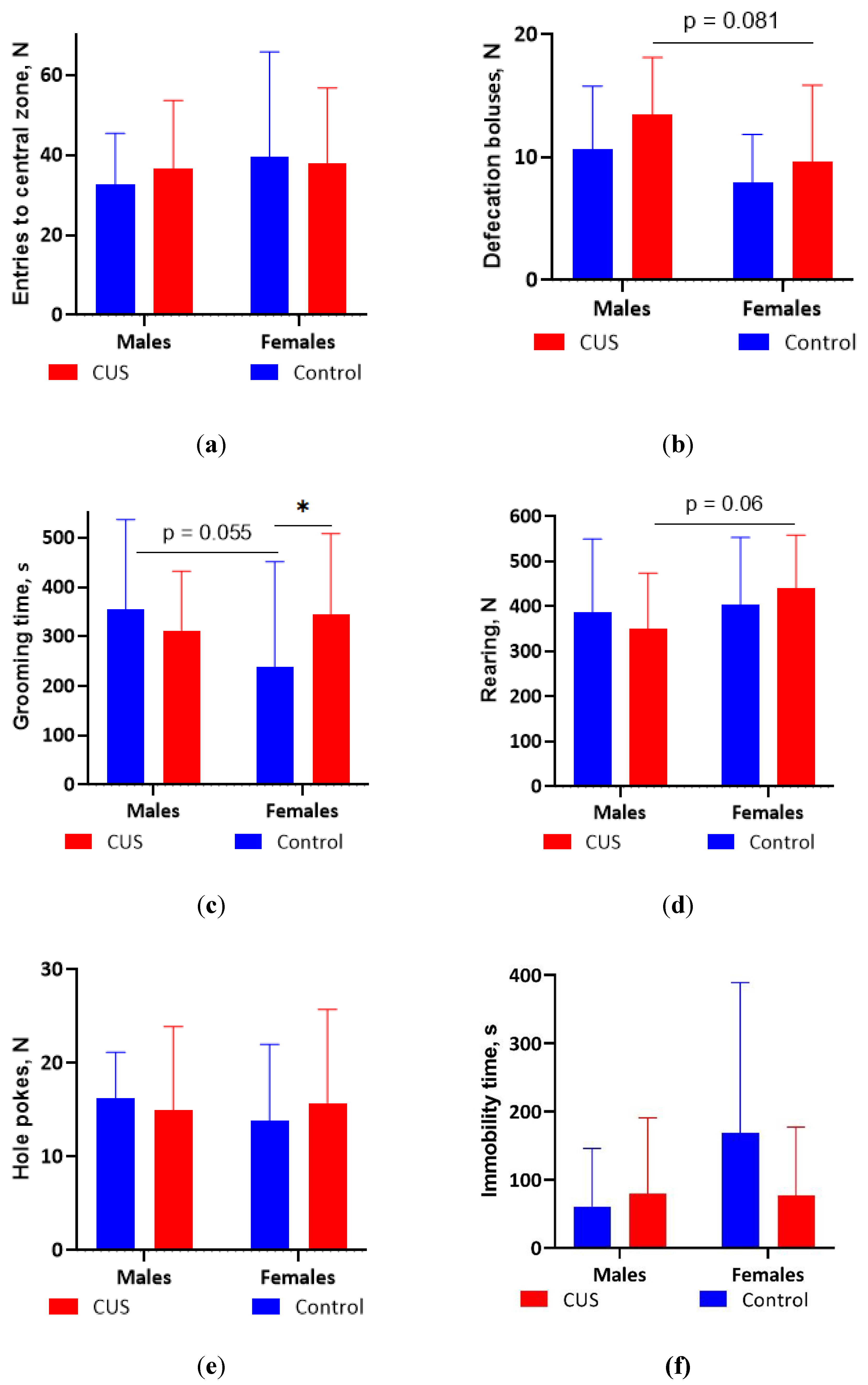

3.3.1. OFT

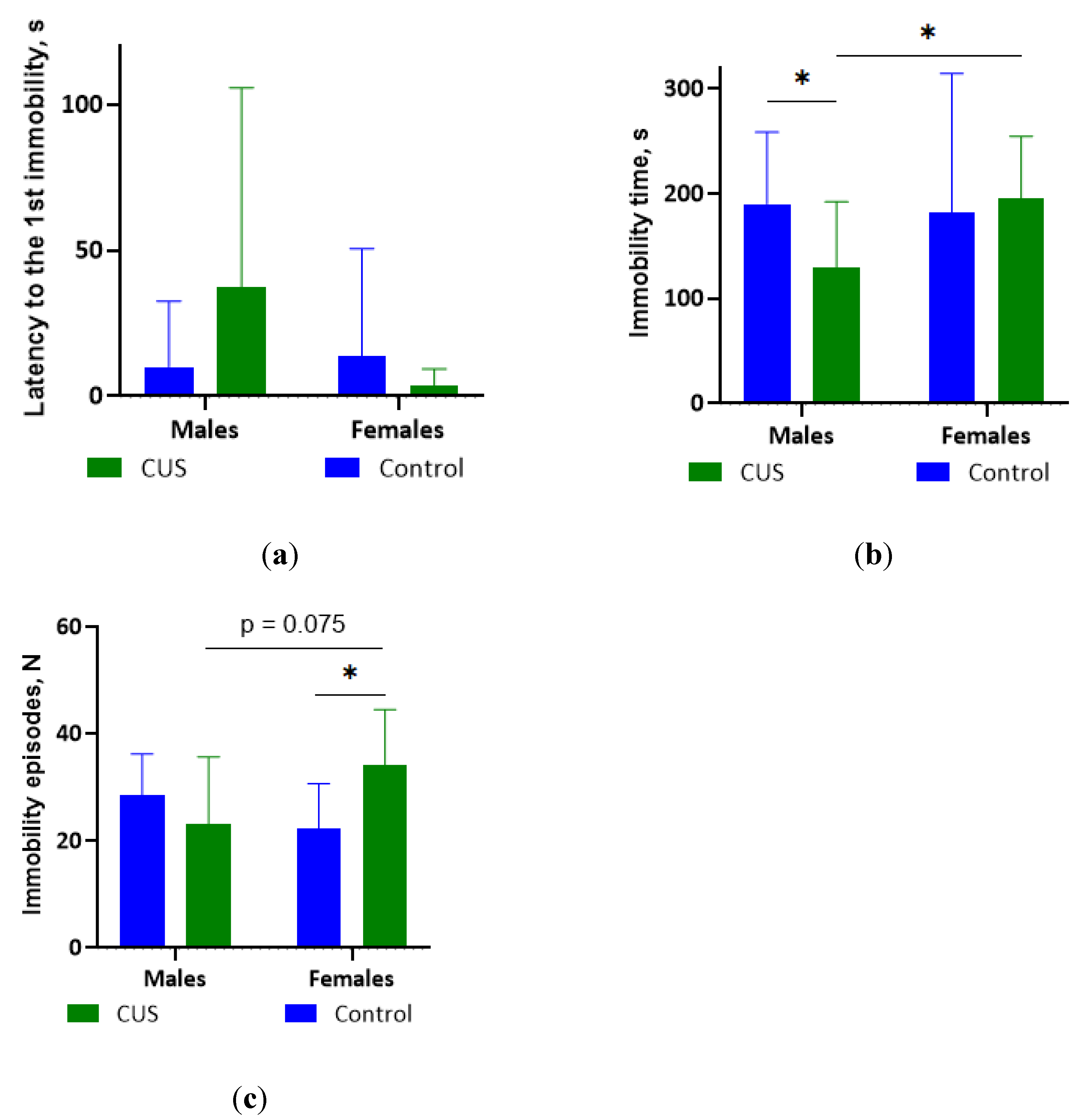

3.3.2. TST

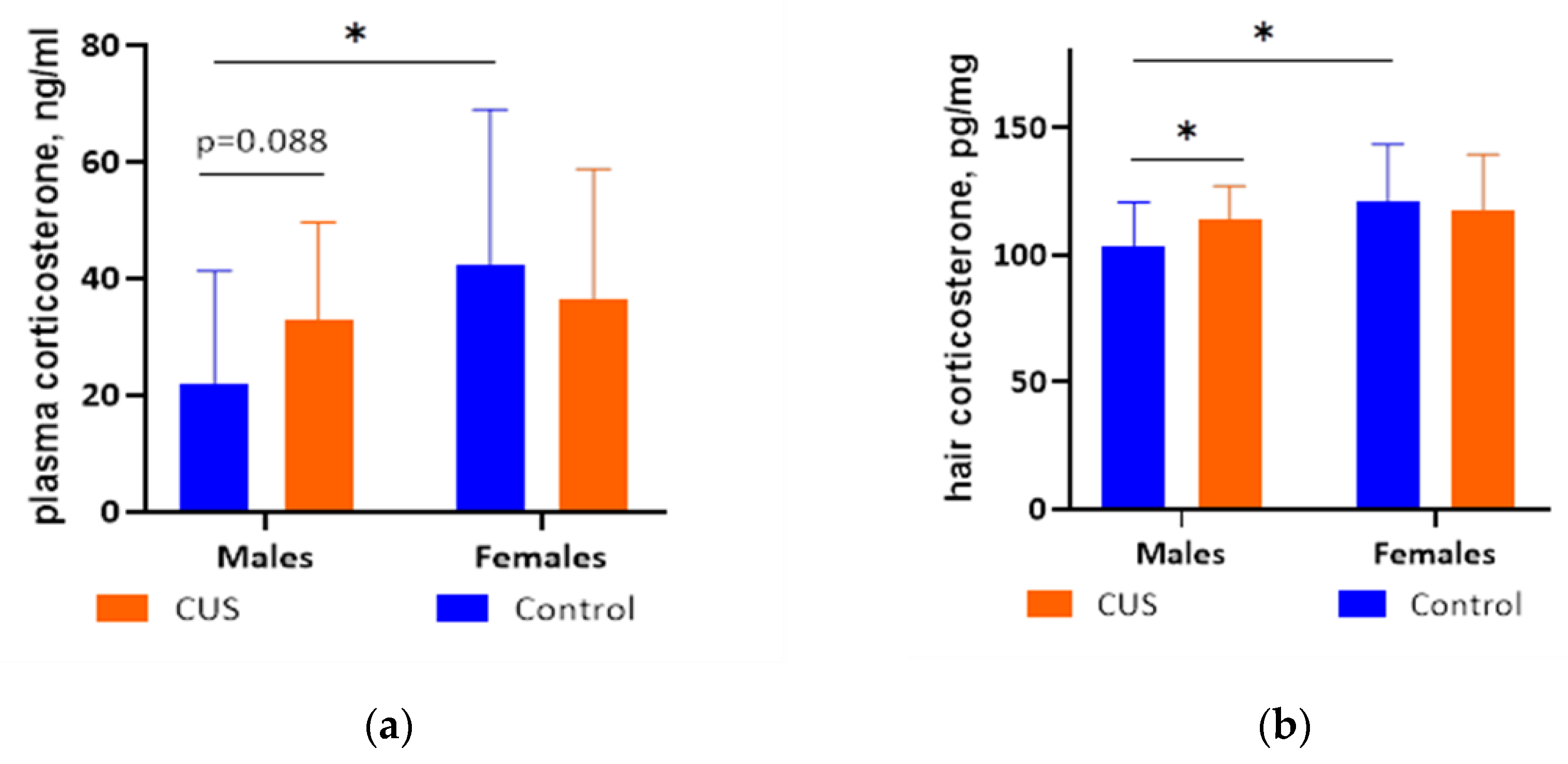

3.4. Hair and Plasma Corticosterone

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| M. m. | Mus musculus |

| CUS | Chronic unpredictable stress |

| OFT | Open field test |

| TST | Tail suspension test |

| FST | Forced swim test |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

References

- Becegato, M.; Silva, R.H. Female Rodents in Behavioral Neuroscience: Narrative Review on the Methodological Pitfalls. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 284, 114645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, A.K.; Zucker, I. Sex Bias in Neuroscience and Biomedical Research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woitowich, N.C.; Beery, A.; Woodruff, T. A 10-Year Follow-up Study of Sex Inclusion in the Biological Sciences. eLife 2020, 9, e56344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, I.; Gellner, A.-K. Long-Term Effects of Chronic Stress Models in Adult Mice. J. Neural. Transm. 2023, 130, 1133–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyola, M.G.; Handa, R.J. Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal and Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Gonadal Axes: Sex Differences in Regulation of Stress Responsivity. Stress 2017, 20, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekker, M.H.J.; Van Mens-Verhulst, J. Anxiety Disorders: Sex Differences in Prevalence, Degree, and Background, But Gender-Neutral Treatment. Gend. Med. 2007, 4, S178–S193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altemus, M.; Sarvaiya, N.; Neill Epperson, C. Sex Differences in Anxiety and Depression Clinical Perspectives. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangasser, D.A.; Cuarenta, A. Sex Differences in Anxiety and Depression: Circuits and Mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 22, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Wingfield, J.C. The Concept of Allostasis in Biology and Biomedicine. Horm. Behav. 2003, 43, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, M.; Casagrande, S.; Ouyang, J.Q.; Baugh, A.T. Glucocorticoid-Mediated Phenotypes in Vertebrates. In Advances in the Study of Behavior; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 48, pp. 41–115 ISBN 9780128047873.

- Vitousek, M.N.; Johnson, M.A.; Downs, C.J.; Miller, E.T.; Martin, L.B.; Francis, C.D.; Donald, J.W.; Fuxjager, M.J.; Goymann, W.; Hau, M.; et al. Macroevolutionary Patterning in Glucocorticoids Suggests Different Selective Pressures Shape Baseline and Stress-Induced Levels. Am. Nat. 2019, 193, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindre-Parker, S. Individual Variation in Glucocorticoid Plasticity: Considerations and Future Directions. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2020, 60, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudielka, B.M.; Buske-Kirschbaum, A.; Hellhammer, D.H.; Kirschbaum, C. HPA Axis Responses to Laboratory Psychosocial Stress in Healthy Elderly Adults, Younger Adults, and Children: Impact of Age and Gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2004, 29, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.N.; Pearce, B.D.; Biron, C.A.; Miller, A.H. Immune Modulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis during Viral Infection. Viral Immunol. 2005, 18, 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, N.E.; Michael Romero, L. Chronic Stress in Free-Living European Starlings Reduces Corticosterone Concentrations and Reproductive Success. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2007, 151, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voznessenskaya, V.V.; Malanina, T.V. Effect of Chemical Signals from a Predator (Felis Catus) on the Reproduction of Mus Musculus. Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2013, 453, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voznessenskaya, V.V. Influence of Cat Odor on Reproductive Behavior and Physiology in the House Mouse: (Mus Musculus). In Neurobiology of Chemical Communication; Mucignat-Caretta, C., Ed.; Frontiers in Neuroscience; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton (FL), 2014; pp. 389-405. ISBN 9781466553415.

- Kvasha, I.G.; Laktionova, T.K.; Voznessenskaya, V.V. The Presentation Rate of Chemical Signals of the Domestic Cat Felis Catus Affects the Reproductive Status of the House Mouse. Biol. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2018, 45, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsamakis, G.; Chrousos, G.; Mastorakos, G. Stress, Female Reproduction and Pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 100, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheriff, M.J.; Dantzer, B.; Delehanty, B.; Palme, R.; Boonstra, R. Measuring Stress in Wildlife: Techniques for Quantifying Glucocorticoids. Oecologia 2011, 166, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogovin, K.A.; Moshkin, M.P. [Autoregulation in mammalian populations and stress: an old theme revisited]. Zh. Obshch. Biol. 2007, 68, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonhomme, F.; Gué, J.-L. Mouse Inbred Strains, Origins Of. In Encyclopedia of Immunology; Elsevier, 1998; pp. 1771–1774 ISBN 9780122267659.

- Sage, R.D.; Atchley, W.R.; Capanna, E. House Mice as Models in Systematic Biology. Syst. Biol. 1993, 42, 523–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhomme, F.; Anand, R.; Darviche, D.; Din, W.; Boursot, P. The mouse as a ring species? In Genetics in Wild Mice. Its Application to Biomedical Research; Moriwaki, K., Shiroishi, T., Yonekawa, H., Eds.; Japan Scientific Societies Press: Tokyo, 1994; pp. 13–23.

- Kotenkova, E.V.; Mal’tsev, A.N.; Ambaryan, A.V. Experimental Analysis of the Reproductive Potential of House Mice (Mus Musculus Sensu Lato, Rodentia, Muridae) in Transcaucasia and Other Regions. Biol. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2018, 45, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, J.R.; Didion, J.P.; Buus, R.J.; Bell, T.A.; Welsh, C.E.; Bonhomme, F.; Yu, A.H.-T.; Nachman, M.W.; Pialek, J.; et al. Subspecific Origin and Haplotype Diversity in the Laboratory Mouse. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorová, S.; Forejt, J. PWD/Ph and PWK/Ph Inbred Mouse Strains of Mus m. Musculus Subspecies--a Valuable Resource of Phenotypic Variations and Genomic Polymorphisms. Folia Biol. (Praha) 2000, 46, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, C.; Liu, L.; Paya-Cano, J.L.; Gregorová, S.; Forejt, J.; Schalkwyk, L.C. Behavioral Characterization of Wild Derived Male Mice (Mus Musculus Musculus) of the PWD/Ph Inbred Strain: High Exploration Compared to C57BL/6J. Behav. Genet. 2004, 34, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bímová, B.; Albrecht, T.; Macholán, M.; Piálek, J. Signalling Components of the House Mouse Mate Recognition System. Behav. Processes 2009, 80, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambaryan, A.V.; Voznessenskaya, V.V.; Kotenkova, E.V. Mating Behavior Differences in Monogamous and Polygamous Sympatric Closely Related Species Mus Musculus and Mus Spicilegus and Their Role in Behavioral Precopulatory Isolation. Rus. J. Theriol. 2019, 18, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiadlovská, Z.; Hamplová, P.; Berchová Bímová, K.; Macholán, M.; Vošlajerová Bímová, B. Ontogeny of Social Hierarchy in Two European House Mouse Subspecies and Difference in the Social Rank of Dispersing Males. Behav. Processes 2021, 183, 104316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, P. The Chronic Mild Stress (CMS) Model of Depression: History, Evaluation and Usage. Neurobiol. Stress 2017, 6, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, S.A.; De La Sancha, N.U.; Pérez, P.; Kabelik, D. Small Mammal Glucocorticoid Concentrations Vary with Forest Fragment Size, Trap Type, and Mammal Taxa in the Interior Atlantic Forest. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlitz, E.H.D.; Runge, J.-N.; König, B.; Winkler, L.; Kirschbaum, C.; Gao, W.; Lindholm, A.K. Steroid Hormones in Hair Reveal Sexual Maturity and Competition in Wild House Mice (Mus Musculus Domesticus). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlitz, E.H.D.; Lindholm, A.K.; Gao, W.; Kirschbaum, C.; König, B. Steroid Hormones in Hair and Fresh Wounds Reveal Sex Specific Costs of Reproductive Engagement and Reproductive Success in Wild House Mice (Mus Musculus Domesticus). Horm. Behav. 2022, 138, 105102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surget, A.; Belzung, C. Unpredictable chronic mild stress in mice. In Experimental Animal Models in Neurobehavioral Research; Kalueff, A.V., LaPorte, J.L., Eds.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 79–112. ISBN 9781606920220. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, S.; Roque, S.; De Sá-Calçada, D.; Sousa, N.; Correia-Neves, M.; Cerqueira, J.J. An Efficient Chronic Unpredictable Stress Protocol to Induce Stress-Related Responses in C57BL/6 Mice. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, E.A.; Manavalan, S.J.; Zhang, Y.; Quartermain, D. Beta Adrenoceptor Blockade Mimics Effects of Stress on Motor Activity in Mice. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1995, 12, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, S.C. The Open Field Test: Reinventing the Wheel. J. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 21, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steru, L.; Chermat, R.; Thierry, B.; Simon, P. The Tail Suspension Test: A New Method for Screening Antidepressants in Mice. Psychopharmacology 1985, 85, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryan, J.F.; Mombereau, C.; Vassout, A. The Tail Suspension Test as a Model for Assessing Antidepressant Activity: Review of Pharmacological and Genetic Studies in Mice. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 571–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.D.; Tiefenbacher, S.; Lutz, C.K.; Novak, M.A.; Meyer, J.S. Analysis of Endogenous Cortisol Concentrations in the Hair of Rhesus Macaques. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2006, 147, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, R.L.; Browne, C.A.; Lucki, I. Hair Corticosterone Measurement in Mouse Models of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 178, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, P. Validity, Reliability and Utility of the Chronic Mild Stress Model of Depression: A 10-Year Review and Evaluation. Psychopharmacology 1997, 134, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Jiang, S.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Kim, C.S.; Blake, D.; Weintraub, N.L.; Lei, Y.; Lu, X.-Y. Chronic Unpredictable Stress Induces Depression-Related Behaviors by Suppressing AgRP Neuron Activity. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2299–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, N.; Bhatnagar, S. Habituation to Repeated Stress: Get Used to It. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2009, 92, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewsbury, D.A.; Baumgerdner, D.J.; Evans, R.L.; Webster, D.G. Sexual Dimorphism for Body Mass in 13 Taxa of Muroid Rodents under Laboratory Conditions. J. Mammal. 1980, 61, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haisová-Slábová, M.; Munclinger, P.; Frynta, D. Sexual Size Dimorphism in Free-living Populations of Mus Musculus: Are Male House Mice Bigger? Acta Zool. Hung. 2010, 56, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- François, M.; Fernández-Gayol, O.; Zeltser, L.M. A Framework for Developing Translationally Relevant Animal Models of Stress-Induced Changes in Eating Behavior. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 91, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, O.; Tsoory, M.; Chen, A. Differential Chronic Social Stress Models in Male and Female Mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 55, 2777–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, M.E. Effects of Stress Due to Deprivation and Transport in Different Genotypes of House Mouse. Lab. Anim. 1976, 10, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.P.; Romero, L.M. Chronic Captivity Stress in Wild Animals Is Highly Species-Specific. Conserv. Physiol. 2019, 7, coz093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomucci, A.; Cabassi, A.; Govoni, P.; Ceresini, G.; Cero, C.; Berra, D.; Dadomo, H.; Franceschini, P.; Dell’Omo, G.; Parmigiani, S.; et al. Metabolic Consequences and Vulnerability to Diet-Induced Obesity in Male Mice under Chronic Social Stress. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzoli, M.; Carboni, L.; Andreoli, M.; Ballottari, A.; Arban, R. Different Susceptibility to Social Defeat Stress of BalbC and C57BL6/J Mice. Behav. Brain. Res. 2011, 216, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghez, V.; Razzoli, M.; Carobbio, S.; Campbell, M.; McCallum, J.; Cero, C.; Ceresini, G.; Cabassi, A.; Govoni, P.; Franceschini, P.; et al. Psychosocial Stress Induces Hyperphagia and Exacerbates Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance and the Manifestations of the Metabolic Syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 2933–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Figueiredo, H.F.; Ostrander, M.M.; Choi, D.C.; Engeland, W.C.; Herman, J.P. Chronic Stress Induces Adrenal Hyperplasia and Hypertrophy in a Subregion-Specific Manner. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 291, E965–E973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruver, A.L.; Sempowski, G.D. Cytokines, Leptin, and Stress-Induced Thymic Atrophy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 84, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrow, A.P.; Heck, A.L.; Miller, A.M.; Sheng, J.A.; Stover, S.A.; Daniels, R.M.; Bales, N.J.; Fleury, T.K.; Handa, R.J. Chronic Variable Stress Alters Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function in the Female Mouse. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 209, 112613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielohuby, M.; Herbach, N.; Wanke, R.; Maser-Gluth, C.; Beuschlein, F.; Wolf, E.; Hoeflich, A. Growth Analysis of the Mouse Adrenal Gland from Weaning to Adulthood: Time- and Gender-Dependent Alterations of Cell Size and Number in the Cortical Compartment. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 293, E139–E146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Gerpe, L.; Rey-Méndez, M. Evolution of the Thymus Size in Response to Physiological and Random Events throughout Life. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2003, 62, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrooz, F.; Alkadhi, K.A.; Salim, S. Understanding Stress: Insights from Rodent Models. Curr. Res. Neurobiol. 2021, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, V.E.; Zagoruĭko, N.V.; Meshkova, N.N.; Kotenkova, E.V. [Exploratory behavior of synantropic and outdoor forms of house mice of superspecies Mus musculus S. lato: a comparative analysis]. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. 1993, 332, 540–542. [Google Scholar]

- Vošlajerová Bímová, B.; Mikula, O.; Macholán, M.; Janotová, K.; Hiadlovská, Z. Female House Mice Do Not Differ in Their Exploratory Behaviour from Males. Ethology 2016, 122, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsolt, R.D.; Bertin, A.; Jalfre, M. Behavioral Despair in Mice: A Primary Screening Test for Antidepressants. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1977, 229, 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Klyuchnikova, M.A. Evaluation of Behavioral Responses to Restraint Stress in the House Mouse (Mus Musculus Musculus) of Wild Origin. Biosci. J. 2024, 40, e40043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagné, V.; Moser, P.; Roux, S.; Porsolt, R.D. Rodent Models of Depression: Forced Swim and Tail Suspension Behavioral Despair Tests in Rats and Mice. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2011, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molendijk, M.L.; De Kloet, E.R. Forced Swim Stressor: Trends in Usage and Mechanistic Consideration. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2022, 55, 2813–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalueff, A.V.; Stewart, A.M.; Song, C.; Berridge, K.C.; Graybiel, A.M.; Fentress, J.C. Neurobiology of Rodent Self-Grooming and Its Value for Translational Neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mineur, Y.S.; Belzung, C.; Crusio, W.E. Effects of Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress on Anxiety and Depression-like Behavior in Mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2006, 175, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pałucha-Poniewiera, A.; Podkowa, K.; Rafało-Ulińska, A.; Brański, P.; Burnat, G. The Influence of the Duration of Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress on the Behavioural Responses of C57BL/6J Mice. Behav. Pharmacol. 2020, 31, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palme, R. Non-Invasive Measurement of Glucocorticoids: Advances and Problems. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 199, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scorrano, F.; Carrasco, J.; Pastor-Ciurana, J.; Belda, X.; Rami-Bastante, A.; Bacci, M.L.; Armario, A. Validation of the Long-term Assessment of Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal Activity in Rats Using Hair Corticosterone as a Biomarker. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarcho, M.R.; Massner, K.J.; Eggert, A.R.; Wichelt, E.L. Behavioral and Physiological Response to Onset and Termination of Social Instability in Female Mice. Horm. Behav. 2016, 78, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchimine, S.; Matsuno, H.; O’Hashi, K.; Chiba, S.; Yoshimura, A.; Kunugi, H.; Sohya, K. Comparison of Physiological and Behavioral Responses to Chronic Restraint Stress between C57BL/6J and BALB/c Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 525, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainor, B.C.; Pride, M.C.; Villalon Landeros, R.; Knoblauch, N.W.; Takahashi, E.Y.; Silva, A.L.; Crean, K.K. Sex Differences in Social Interaction Behavior Following Social Defeat Stress in the Monogamous California Mouse (Peromyscus Californicus). PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohlbaum, K.; Merle, R.; Frahm, S.; Rex, A.; Palme, R.; Thöne-Reineke, C.; Ullmann, K. Effects of Separated Pair Housing of Female C57BL/6JRj Mice on Well-Being. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso-Frías, J.; Soto-Gamboa, M.; Mastromonaco, G.; Acosta-Jamett, G. Seasonal Hair Glucocorticoid Fluctuations in Wild Mice (Phyllotis Darwini) within a Semi-Arid Landscape in North-Central Chile. Animals 2024, 14, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colding-Jørgensen, P.; Hestehave, S.; Abelson, K.S.P.; Kalliokoski, O. Hair Glucocorticoids Are Not a Historical Marker of Stress – Exploring the Time-Scale of Corticosterone Incorporation into Hairs in a Rat Model. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2023, 341, 114335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gáll, Z.; Farkas, S.; Albert, Á.; Ferencz, E.; Vancea, S.; Urkon, M.; Kolcsár, M. Effects of Chronic Cannabidiol Treatment in the Rat Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress Model of Depression. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stage | Timeline (41-44 days in total) | Procedures | |||

|

CUS group 12 males + 13 females |

Control group 14 males + 13 females |

||||

| experimental chronic stress | ↓ | 36 days | CUS protocol | undisturbed | |

| body weight on Days 1, 15, 29, and 36 | |||||

| rest | ↓ | 1–4 days | undisturbed | ||

| behavioral tests | ↓ | 2 days | open field test (OFT) (on the 1st day), tail suspension test (TST) (on the 2nd day) | ||

| hair collection | ↓ | 1 day | hair sampling | ||

| terminal | ↓ | 1 day | euthanasia, blood collection, organ weights | ||

| Days |

Control, males |

CUS, males |

Control, females |

CUS, females |

Two-way ANOVA, p-level |

t-test, p-level |

||

| N = 14 | N = 12 | N = 13 | N = 13 | sex | group | sex*group | ||

| 1-15 | 1.14 ± 1.23 (+7%) |

−0.25 ± 0.71 (−1%) |

0.70 ± 0.76 (+5%) |

−1.14 ± 0.55 (−7%) |

** m > f |

*** S < C |

n.s. | Sf < Cf*** Sm < Cm** Sm > Sf** Cm > Cf n.s. |

| 15-29 | −0.13 ± 0.71 (−1%) |

0.37 ± 0.48 (+3%) |

0.39 ± 0.77 (+3%) |

0.45 ± 0.45 (+2%) |

# m < f |

n.s. | n.s. | Sf > Cf n.s. Sm > Cm * Sm < Sf n.s. Cm < Cf # |

| 29-36 | 0.39 ± 0.48 (+2%) |

0.87± 0.98 (+4%) |

−0.16 ± 0.72 (−1%) |

0.56 ± 0.73 (+5%) |

* m > f |

** S > C |

n.s. | Sf > Cf * Sm > Cm n.s. Sm > Sf n.s. Cm > Cf* |

| 1-36 (Total) |

1.40 ± 1.39 (+9%) |

0.99 ± 0.94 (+6%) |

0.93 ± 0.83 (+7%) |

−0.13 ± 0.80 (−1%) |

** m > f |

* S < C |

n.s. |

Sf < Cf** Sm < Cm n.s. Sm > Sf** Cm > Cf n.s. |

| Control, males |

CUS, males |

Control, females |

CUS, females |

Two-way ANOVA, p-level |

t-test, p-level |

|||

| N = 14 | N = 12 | N = 13 | N = 13 | sex | group | sex*group | ||

| Thymus, mg (per 1 g of BW) |

14.92 ± 4.11 (0.92) |

16.83 ± 3.23 (0.99) |

15.42 ± 3.11 (1.06) |

17.88 ± 4.92 (1.17) |

n.s. m < f |

# S > C |

n.s. | Sf > Cf n.s. Sm > Cm n.s. Sm < Sf n.s. Cm < Cf n.s. |

| Adrenal glands, mg (per 1 g of BW) |

5.19 ± 1.26 (0.32) |

6.36 ± 2.01 (0.37) |

6.56 ± 1.25 (0.45) |

7.25 ± 2.20 (0.47) |

* m < f |

# S > C |

n.s. | Sf > Cf n.s. Sm > Cm # Sm < Sf n.s. Cm < Cf** |

| BW, g | 16.30 ± 2.20 | 16.97 ± 1.71 | 14.56 ± 2.08 | 15.34 ± 1.58 | ** m > f |

n.s. S > C |

n.s. | Sf > Cf n.s. Sm > Cm n.s. Sm > Sf * Cm > Cf* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).