1. Introduction

Nowadays superfruits are used in the cosmetic industry for skin benefits. The term “superfruit” typically describes fruits that are abundant in antioxidants, making them highly beneficial for human health [1]. Acai is a widely recognized superfruit. The Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) is native to Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, Bolivia, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. These trees are characterized by their tall, slender appearance and produce small, round fruits with a black-purple hue [2]. Acai berry extract is renowned for its exceptionally high antioxidant content, surpassing that of cranberries, raspberries, blackberries, strawberries, and blueberries. It is particularly rich in anthocyanins, flavonoids, carotenoids, and polyphenols, which are widely recognized for their anti-aging properties and potential as key ingredients in cosmetic formulations [3,4,5,6,7]. The therapeutic properties of superfruits are predominantly derived from their active constituents, with phenolic compounds being especially noteworthy. These phytochemically active phenolics are instrumental in delivering positive effects on the skin, effectively addressing issues such as dryness, wrinkles, and dullness, which are prominent signs of skin aging [4]. Moreover, studies have indicated that Acai berry exhibits a remarkable ability to inhibit the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), confirming its efficacy in mitigating oxidative stress and inflammatory responses [5]. An in vivo study conducted by Favacho et al. evaluated the effects of Euterpe oleracea on skin inflammation and immune responses using commercially available Acai fruit oil. Additionally, an in vitro study by Petruk et al. examined the protective activity of E. oleracea against UV-induced skin damage. Furthermore, Kang et al. conducted both in vivo and in vitro studies to explore the wound-healing properties of Acai berry preparations [6]. Acai-based formulations hold significant potential for use in multifunctional cosmetic products, offering a holistic approach to skincare. With their rich composition of antioxidants, essential fatty acids, and polyphenols, these formulations can effectively address hydration, provide anti-aging benefits by reducing the appearance of wrinkles and fine lines, and protect the skin from environmental stressors such as UV radiation and pollution. This versatility positions Acai as a valuable ingredient in developing innovative products that cater to diverse skin care needs. In recent years, the utilization of by-products derived from plant origins has emerged as a significant trend in cosmetics. These by-products are abundant in sugars, minerals, organic acids, dietary fiber, and bioactive compounds such as polyphenols and carotenoids. Their characterization and valorization have the potential to transform them into high-value products with applications across various biotechnological fields, including cosmetics. Moreover, this approach contributes to reducing environmental waste and lowering associated treatment costs [8]. This experiment will specifically investigate the skin hydration properties of Acai oil, aligning with the growing clean beauty trend that emphasizes the use of sustainable and natural products. Derived from the Acai palm, a nutrient-rich superfruit native to the Amazon rainforest, Acai oil embodies the principles of clean beauty through its minimal environmental impact and transparency in formulation. Its natural origin not only supports eco-friendly practices but also caters to consumer demand for ethically sourced and effective skincare solutions. The demand for natural, plant-based ingredients in products has seen significant growth, driven by health-conscious and environmentally aware consumers [9]. This shift reflects a preference for formulations that are free from synthetic chemicals, and perceived as safer for both the skin and the environment [10]. Natural ingredients like Acai provide a safer and more biocompatible alternative to synthetic chemicals, making them highly desirable in skincare formulations. In this study, ABS Acai Sterols EFA, sourced from Active Concepts, was employed as the active ingredient to evaluate its moisturizing and hydrating benefits.

The investigation involved a comparative analysis of three formulations: a base lotion (without active ingredients), an Acai lotion (containing ABS Acai Sterols EFA), and a nanoemulsion formulation (incorporating nanoparticles of ABS Acai Sterols EFA). This approach aimed to assess the efficacy of Acai Sterols EFA in enhancing skin hydration and to explore the potential benefits of nanoparticle-based delivery systems in improving performance.

2. Nano-Encapsulation Systems

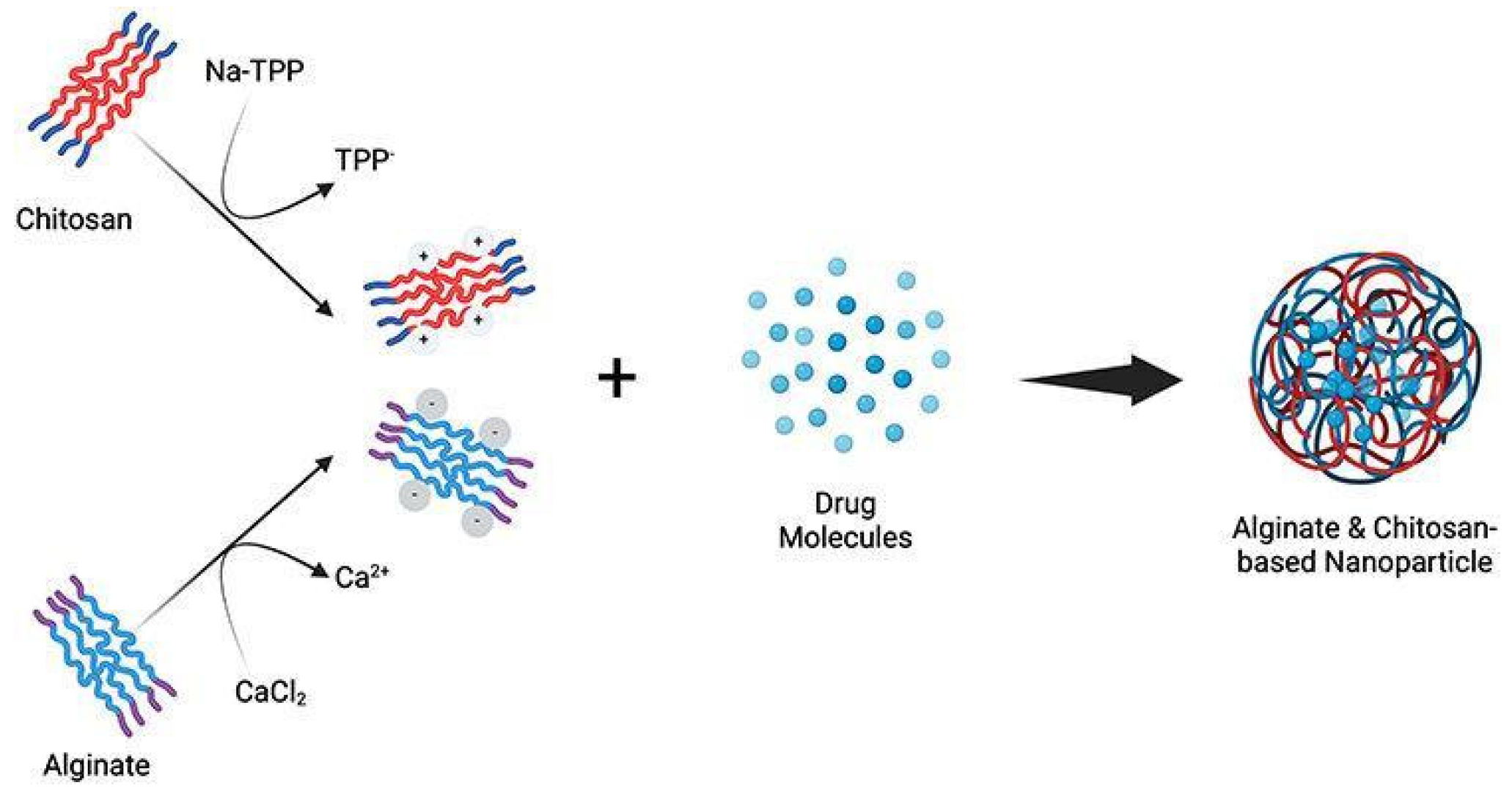

Nano-encapsulation enhances the efficacy of natural ingredients by protecting them from environmental factors like light, air, and heat, ensuring their stability and potency while preserving their beneficial properties over time [11,12]. The type of nanoemulsion that was prepared in this study was chitosan-sodium alginate nanoparticles. Currently, the idea of using nanoparticles made from naturally biodegradable polymers to deliver drugs has aroused great interest. Especially, alginate and chitosan are very promising and widely used in the pharmaceutical industry to control drug release [13].

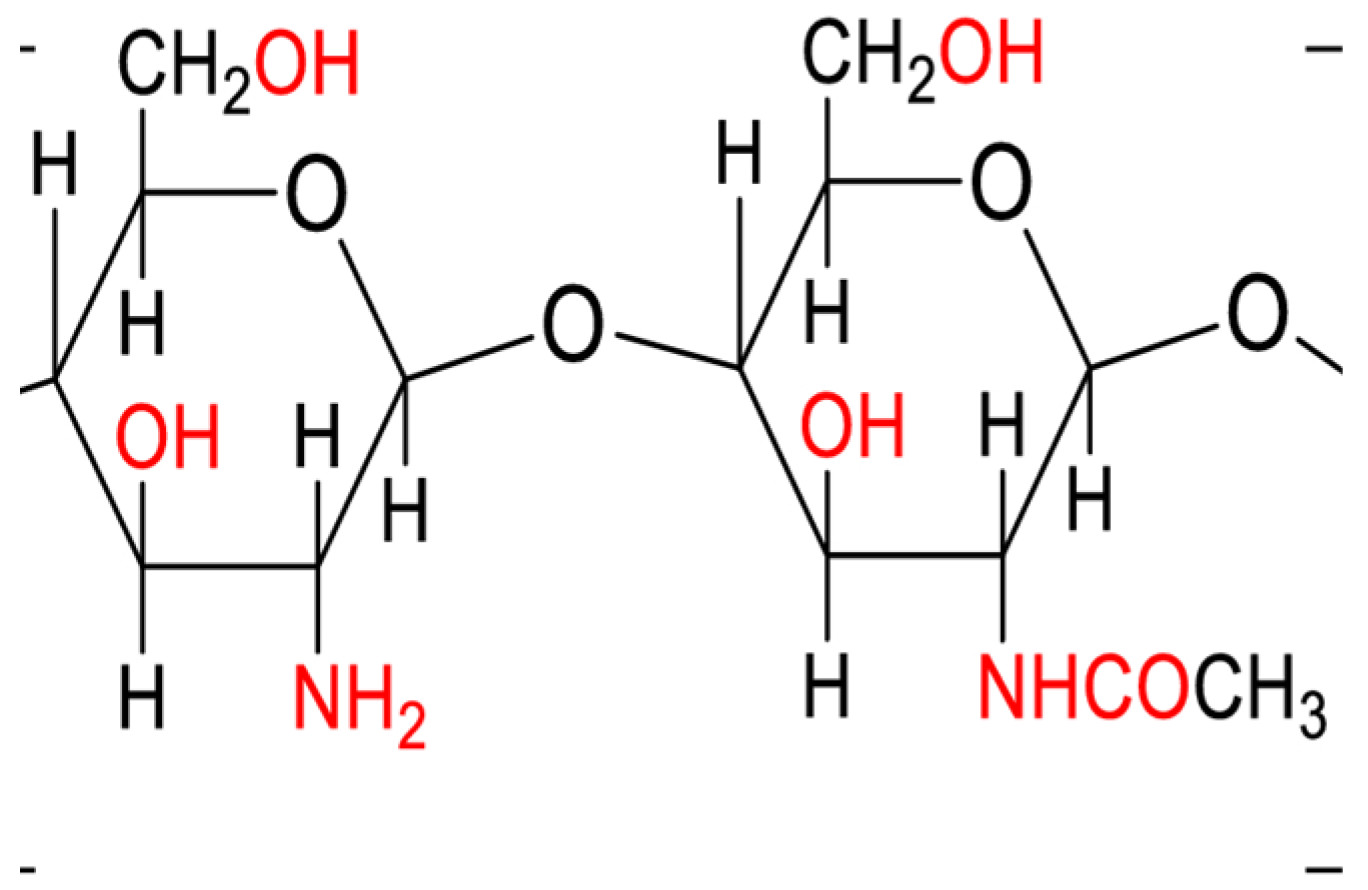

Chitosan is derived from chitin. It is a natural polycationic linear polysaccharide and is recognized as a versatile biomaterial because of its non-toxicity, low allergenicity, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [14].

Figure 1.

Chemical Structure of Chitosan Polymer [24].

Figure 1.

Chemical Structure of Chitosan Polymer [24].

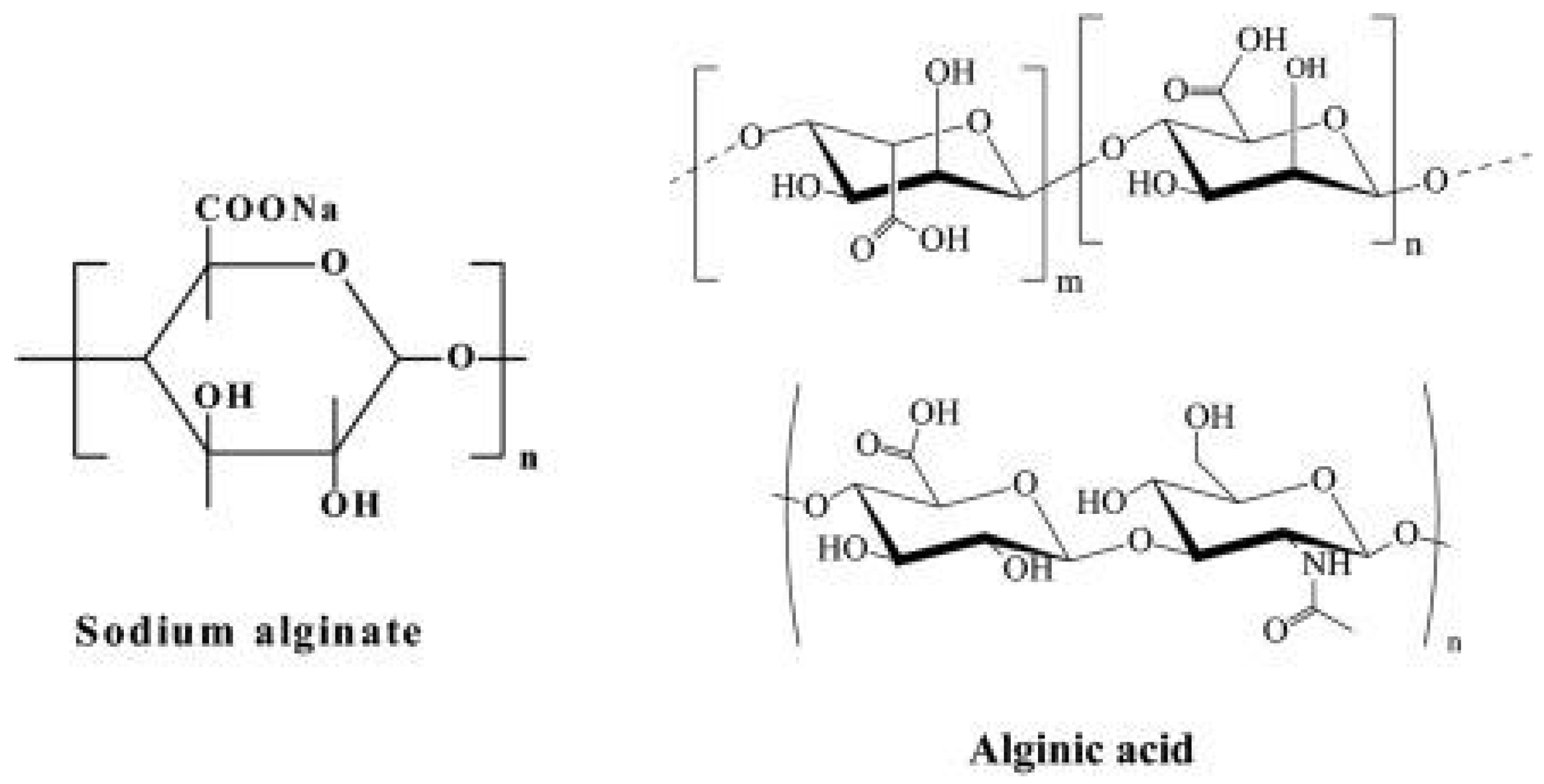

Alginate is a biocompatible biomaterial that forms stable, reversible gels in hydrogel form, making it an ideal, cost-effective, and readily available encapsulation matrix with the ability to rapidly absorb water, resulting in a viscous gum-like consistency [15,16].

Figure 2.

Chemical Structure of Sodium Alginate (Left) and Alginic Acid (Right) [25].

Figure 2.

Chemical Structure of Sodium Alginate (Left) and Alginic Acid (Right) [25].

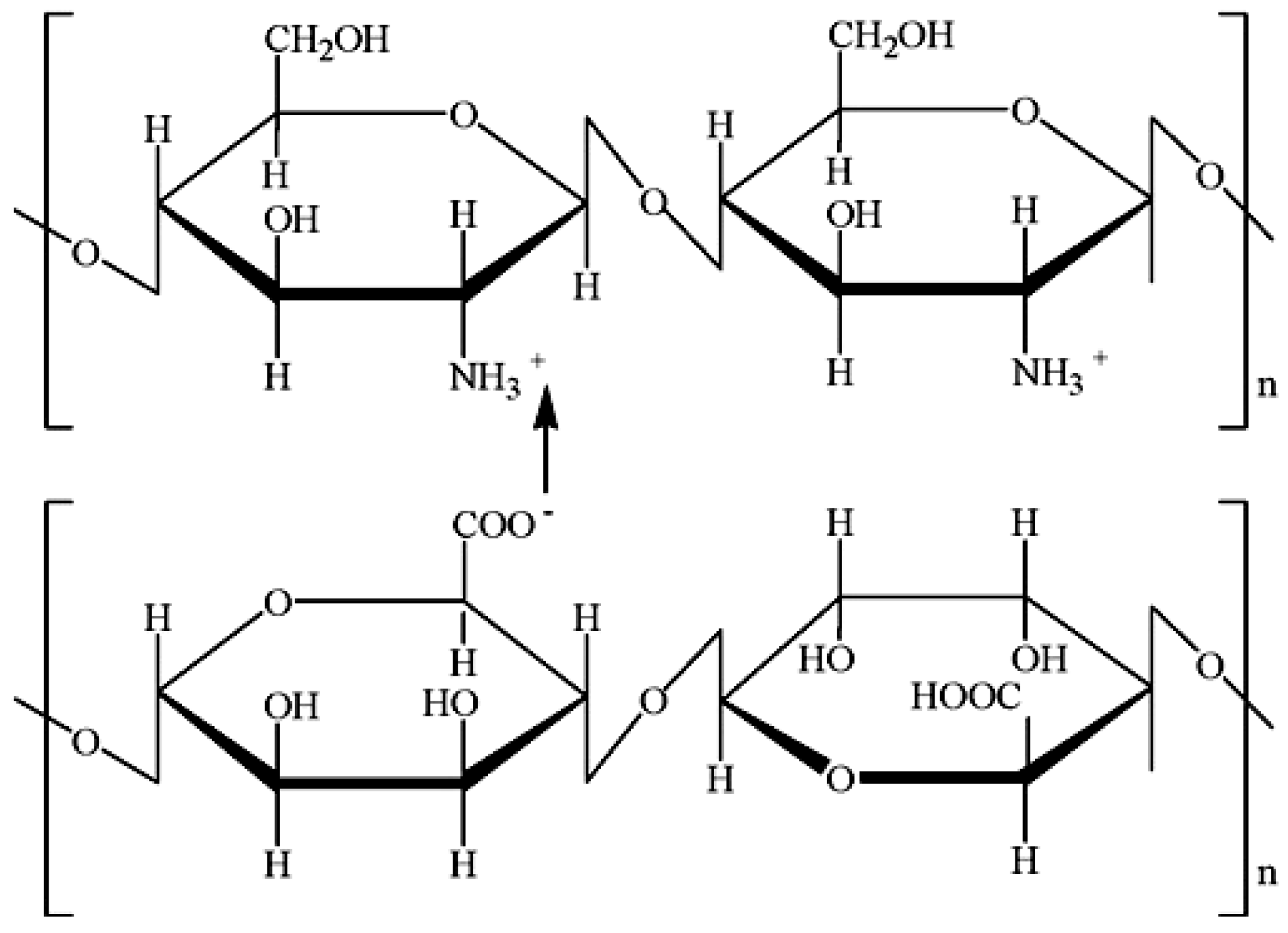

The integration of sodium alginate with other biomaterials like chitosan could offer a novel approach to regulating drug delivery [17].

Figure 3.

Structures and Scheme of Chitosan-Alginate Interaction [26].

Figure 3.

Structures and Scheme of Chitosan-Alginate Interaction [26].

In this study, nanoparticles were prepared with calcium alginate pre-gel by ionotropic gelation in the first stage followed by chitosan polyelectrolyte complexation [13]. The biodegradable and biocompatible nature of Alginate and Chitosan polymers, widely recognized in the medical industry [18], makes them highly suitable for safe and effective use in skincare applications. In addition, Alginate and Chitosan polymers possess unique properties such as film-forming, moisturizing, and antimicrobial effects, which enhance the functional benefits and efficacy of cosmetic formulations [19,20]. Ionic gelation is a simple, mild, and solvent-free method for forming stable nanoparticles by interacting oppositely charged macromolecules with a nontoxic, multivalent material to provide charge density, offering high loading capacity but facing limitations such as large particle sizes and pH sensitivity [21,22,23].

Figure 4.

The mechanism of forming alginate and chitosan-based nanoparticles [27].

Figure 4.

The mechanism of forming alginate and chitosan-based nanoparticles [27].

Currently, the drug-loading capacity of most nanoparticle systems is relatively low, typically under 10 wt% [28] while micellar nanoparticles can encapsulate a maximum of approximately 20%–30% relative to the polymer content [29].

This study aimed to develop a nanoparticle-based formulation incorporating Acai oil to evaluate its performance and refine it for future cosmetic applications. Encapsulation into nanoparticles enhances the oil’s stability and enables prolonged release, thereby optimizing its moisturizing properties. By merging the natural benefits of Acai with cutting-edge nanotechnology, this research bridges traditional remedies and modern cosmetic science. Moreover, the limited exploration of Acai in advanced nano-delivery systems highlights the significance of this study in paving the way for innovative opportunities in the field.

3. Phytochemical Profile

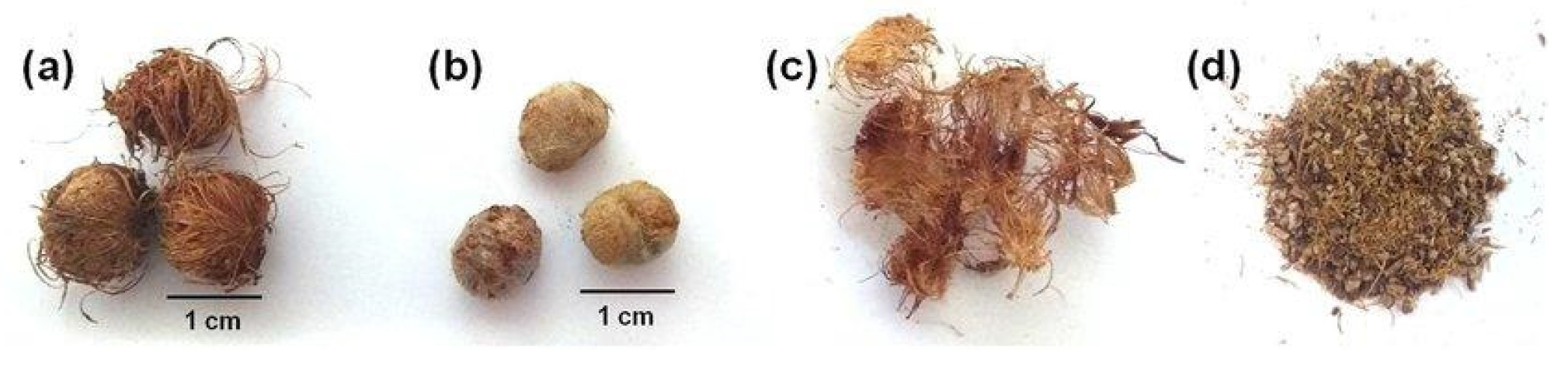

The health-enhancing benefits of acai are primarily attributed to its abundant bioactive phytochemicals, with a specific focus in this context on the properties of acai oil. Acai oil is extracted from the pulp (

Figure 5) or seeds (

Figure 6) of the acai berry, which is harvested from the acai palm tree.

Figure 5.

Characteristic of Acai Pulp [30].

Figure 5.

Characteristic of Acai Pulp [30].

Acai pulp and seeds are rich in phytochemicals, with polyphenol content comprising 28.3% in seeds and 25.5% in pulp, predominantly cyanidin 3-glucoside and cyanidin 3-rutinoside [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Acai pulp undergoes clarification through the extraction of açaí oil using a water-insoluble filter cake. Studies have identified the presence of several phenolic acids, including protocatechuic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid, and ferulic acid, as well as the flavonoid (+)-catechin, in the extracted oil [36].

Figure 6.

Acai seed samples: (a) whole seeds; (b) core stone after removing the external fibers; (c) fiber layer; (d) milled whole seeds [32].

Figure 6.

Acai seed samples: (a) whole seeds; (b) core stone after removing the external fibers; (c) fiber layer; (d) milled whole seeds [32].

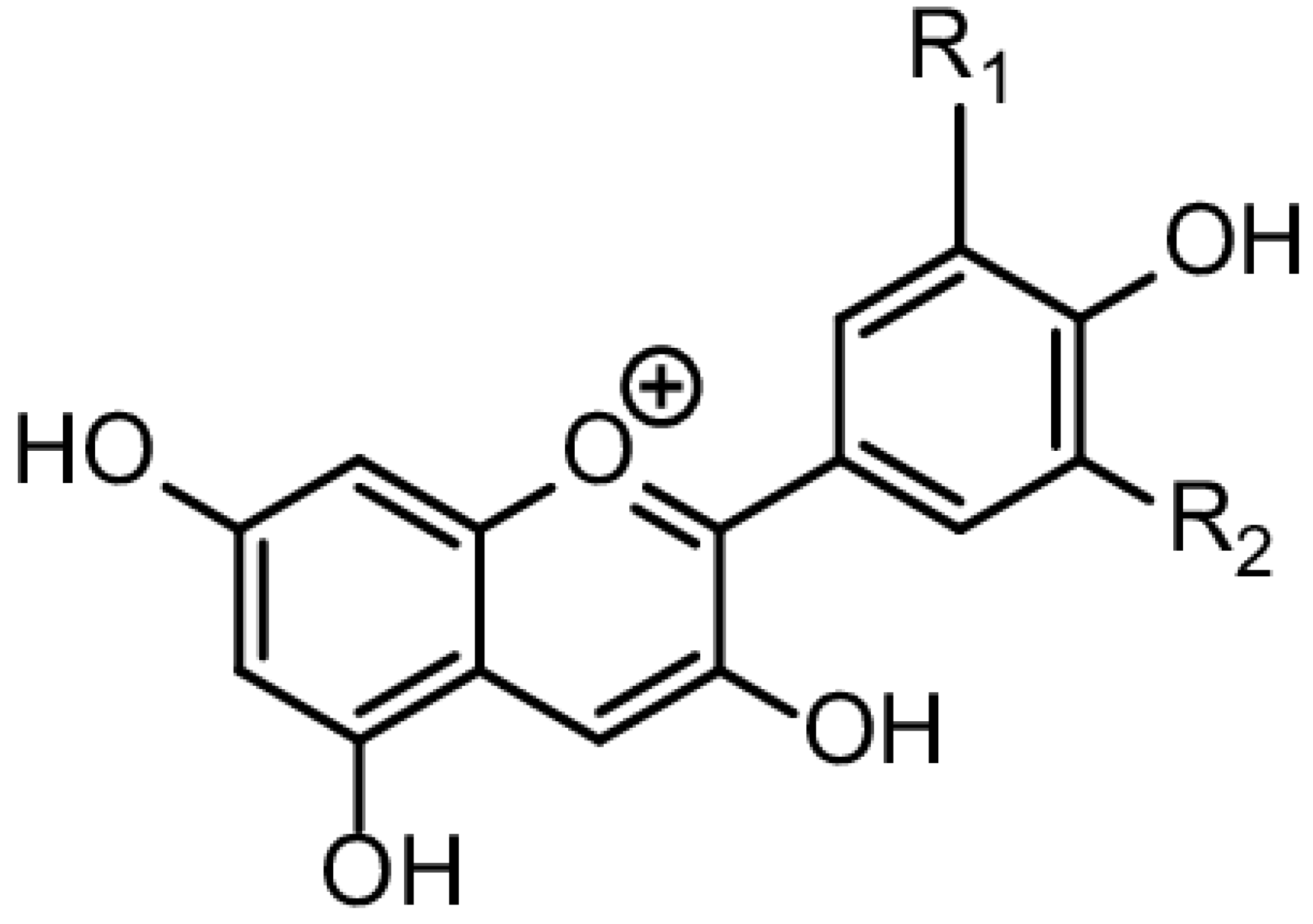

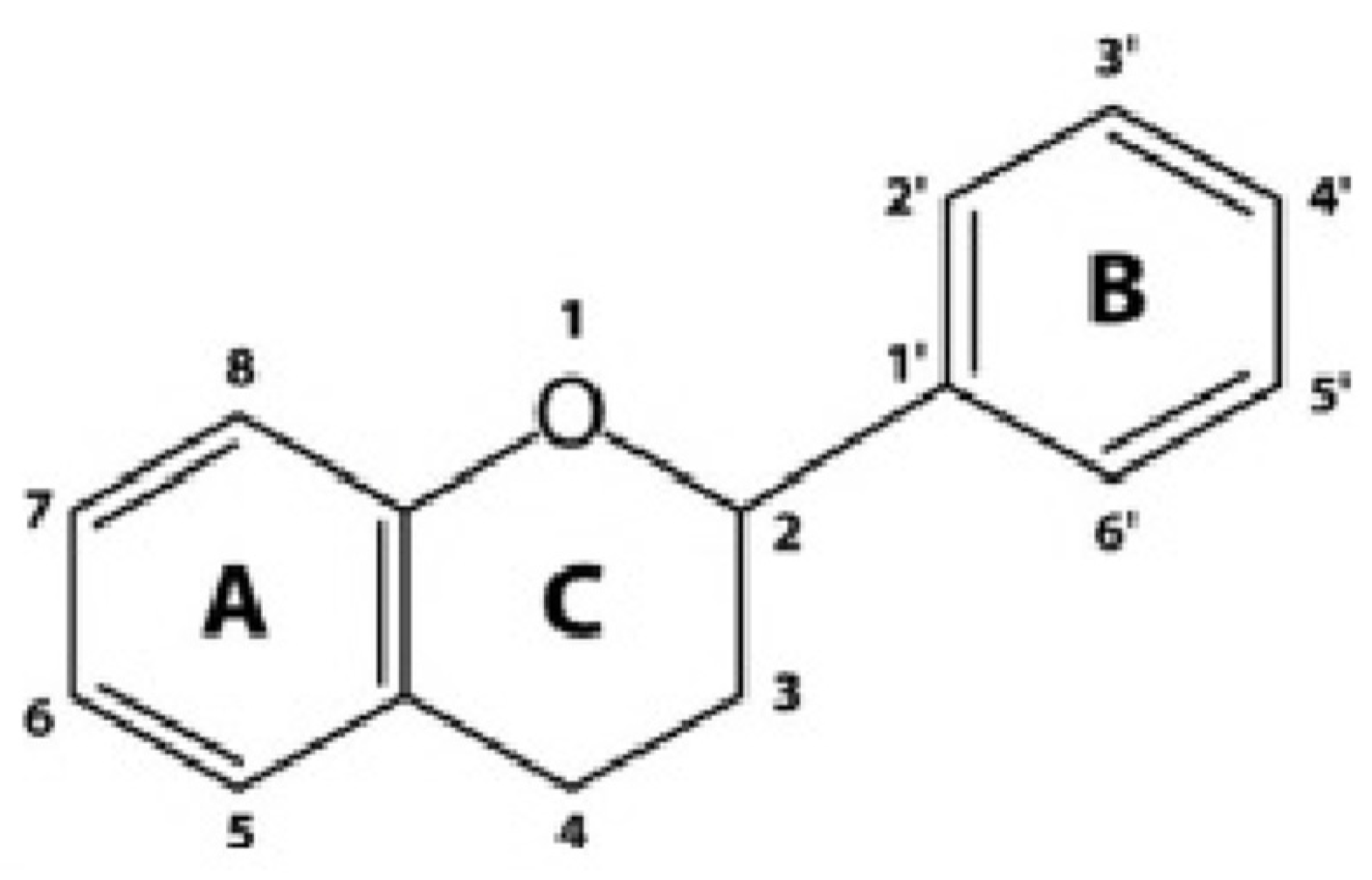

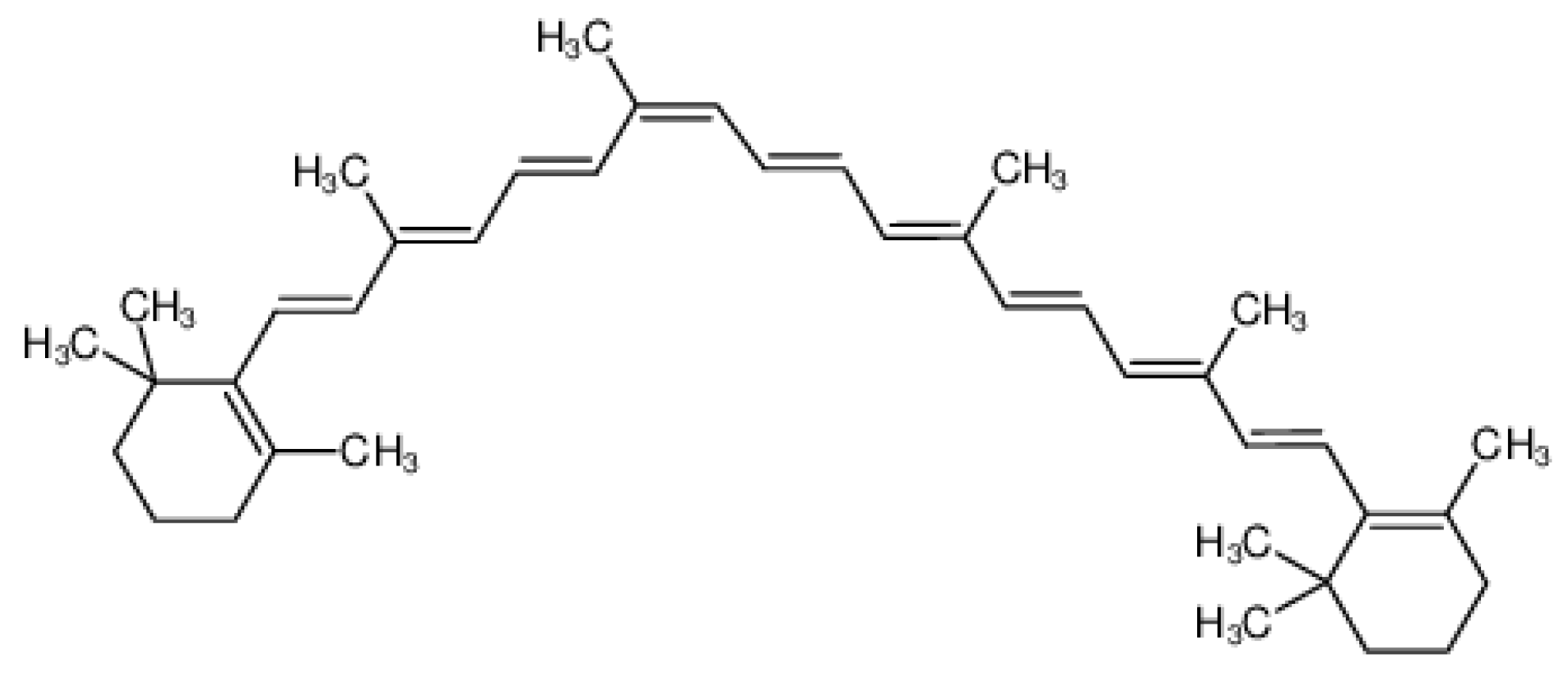

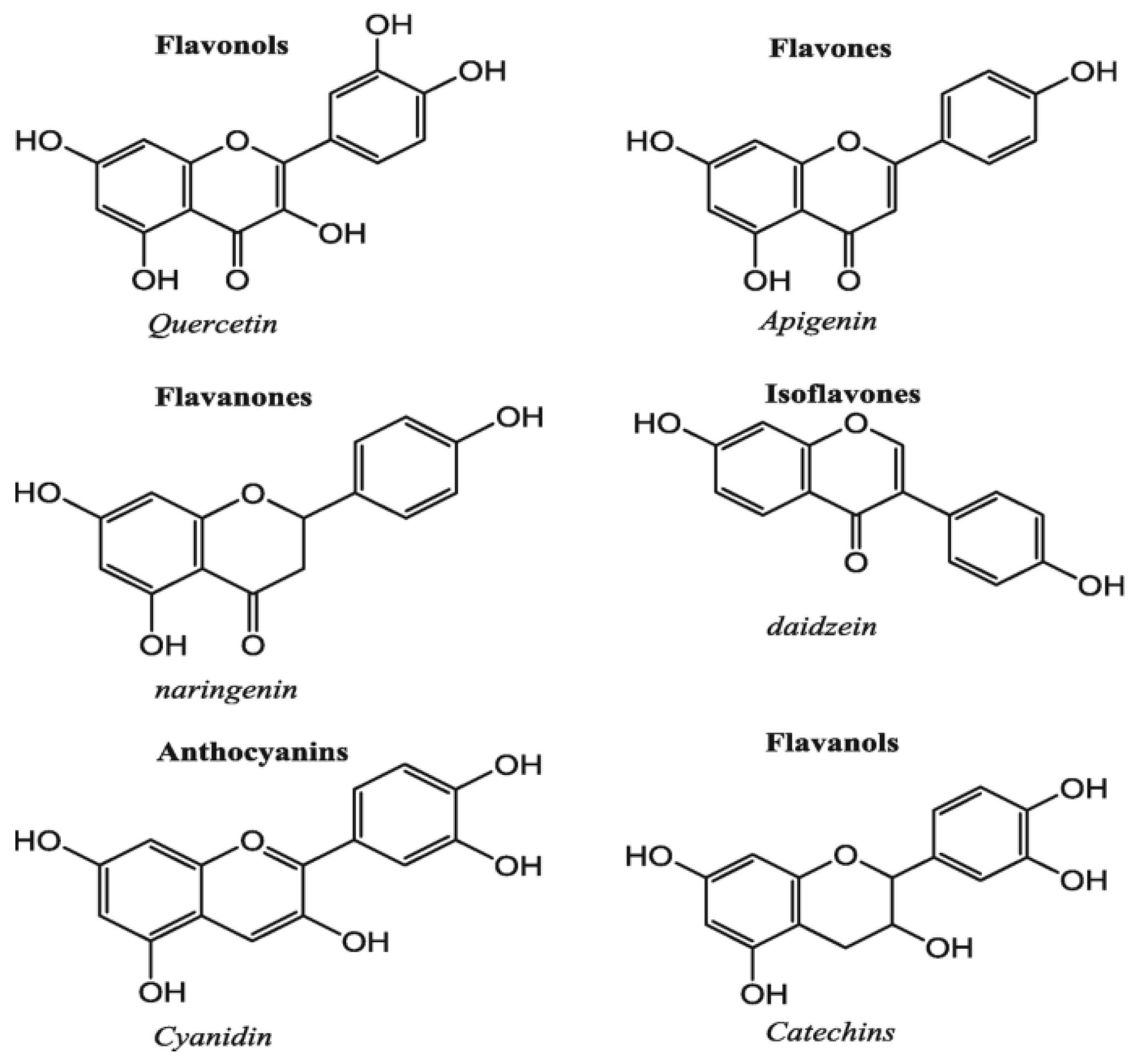

As previously mentioned, acai oil is especially rich in anthocyanins (

Figure 7), flavonoids (

Figure 8), carotenoids (

Figure 9), and polyphenols (

Figure 10), which are well-known for their moisturizing and anti-aging benefits [3,4,7]

Figure 7.

Chemical Structure of Anthocyanin [37].

Figure 7.

Chemical Structure of Anthocyanin [37].

Figure 8.

Chemical Structure of Flavonoid [38].

Figure 8.

Chemical Structure of Flavonoid [38].

Figure 9.

Chemical Structure of Carotenoid [39].

Figure 9.

Chemical Structure of Carotenoid [39].

Figure 10.

Chemical Structure and Classification of Polyphenols [40].

Figure 10.

Chemical Structure and Classification of Polyphenols [40].

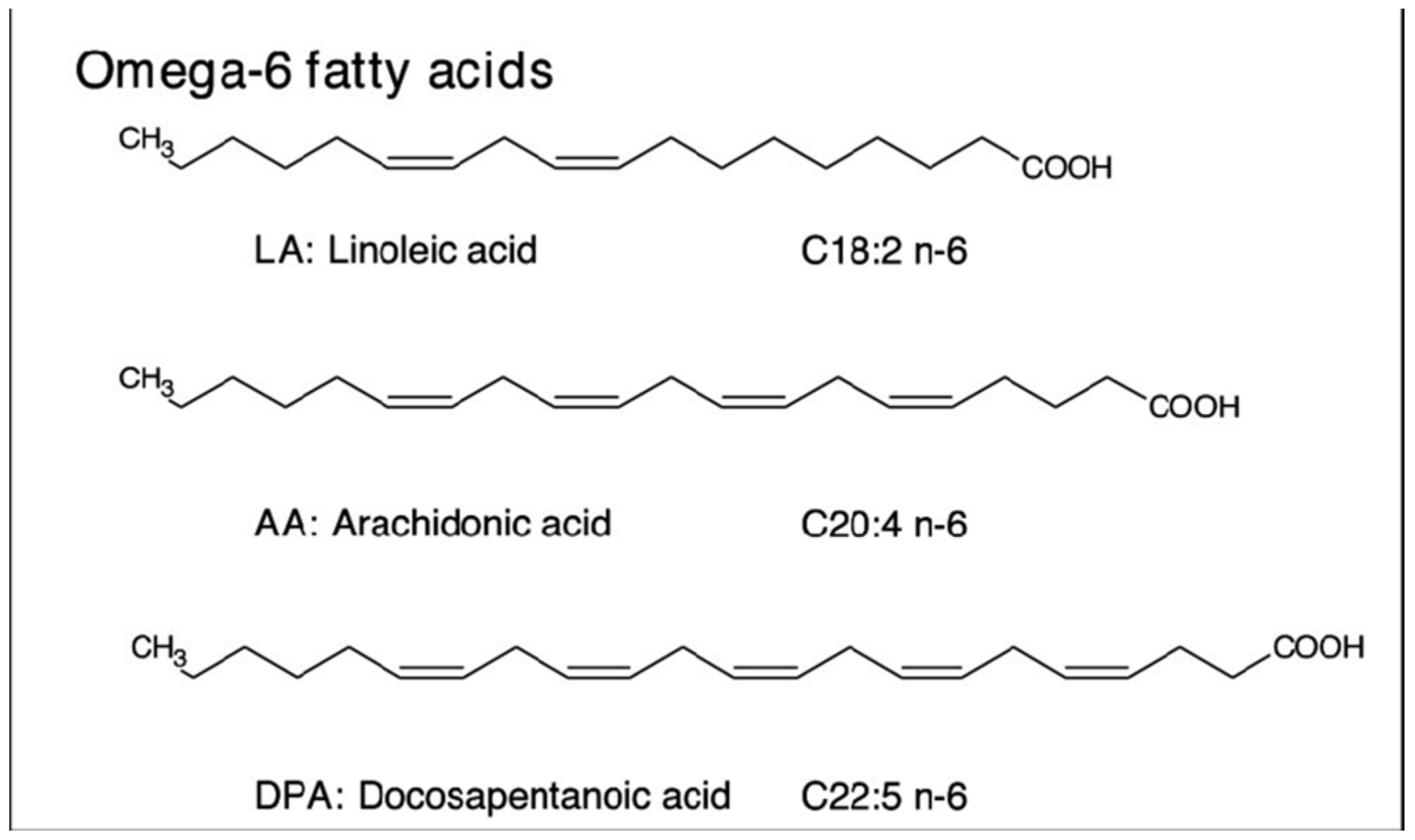

Furthermore, the omega-6 fatty acids (

Figure 11) present in acai are essential for maintaining skin hydration and elasticity, serving as fundamental components of ceramides within the skin barrier [41,42].

Figure 11.

Chemical Structure of Omega 6 Fatty Acids [43].

Figure 11.

Chemical Structure of Omega 6 Fatty Acids [43].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.1.1. Chemical and Ingredients

ABS Acai Sterols EFA and Acai Berry Virgin Oil were supplied by Adina Cosmetic Ingredients (Tunbridge Wells, UK); Calcium Chloride, Caprylic/Capric Triglyceride, Chitosan Powder, and Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid, and Sodium Alginate Powder were supplied by VWR International (Lutterworth, UK); Olivem® VS Feel was supplied by Hallstar Beauty (Redditch, UK); Glycerin, Xanthan Gum, Phenoxyethanol, and Propylene Glycol were supplied by MakingCosmetics (Washington, US).

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Preparation of Chitosan-Sodium Alginate Nanoparticles

Preparation of CS-ALG Nanoparticles by High-Pressure Condition

The Chitosan-sodium alginate nanoparticles were prepared by the principle involving cation-induced controlled gelification of alginate [17]. Briefly, calcium chloride (1.5 ml, 18 mM) was added to 28.5 ml of sodium alginate solution (0.06% w/v) [44,45]. Six ml of chitosan solution (0.05% w/v) was added and followed by homogenization at 10,000 rpm for 5 min (Silverson Model L5 Series, Silverson Machines Ltd., Chesham, UK) and Ultrasonication for 10 minutes (Camlab Transsonic T460, Camlab Ltd., Cambridge, UK) [44,45] After that, the nanoparticles were recovered by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 45 min (MSE Mistral 1000, Wolflabs, York, UK) and washed thrice with distilled water to obtain the final pellets. In this study, the use of the homogenizer and centrifuge was limited. Homogenization was conducted at 8,000 rpm for 3 min, while ultrasonication was applied for 10 min. Centrifugation was performed at 1,500 rpm for 45 min.

Preparation of the Active-Loaded NPs

ABS Acai Sterols EFA was melted and added into sodium alginate before the addition of calcium chloride and chitosan respectively. The characteristics of the active-loaded nanoparticles shall also be collected. For determining the loading efficiency of the process, the nanoparticles were segregated from the liquid suspension medium by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 45 min with MSE Mistral 1000. The amount of active-loaded nanoparticles was calculated by using the differences between the total weight used to prepare the nanoparticles and the weight that was found in pellets. Entrapment efficiency provides insight into the percentage of the drug successfully encapsulated or adsorbed within the nanoparticles

(Equation 1), whereas loading capacity indicates the amount of drug contained within the nanoparticles following their separation from the medium

(Equation 2) [46,47]. The active loading capacity of the nanoparticles and entrapment efficiency of the process were calculated as indicated below:

Supernatants are in the nanocrystal form when combined with the CS-ALG solution. A control experiment was performed to determine whether these nanoparticles are associated with CS-ALG nanoparticles or suspended independently. In this control experiment, the suspension of ABS Acai Sterols EFA nanocrystals was centrifuged in the specific condition that was mentioned above. Then the amount of Acai Sterols EFA that formed sediments was determined.

4.2.2. Analytical Characterization of the Nanoparticles

The morphological examination of the Acai Sterols EFA-loaded CS-ALG nanoparticles was performed with an optical microscope (Olympus BH-2, Scientific Laboratory Supplies Ltd., Nottingham, UK) equipped with the Axiovision 4.4 software [48,49].

4.2.3. Formulation

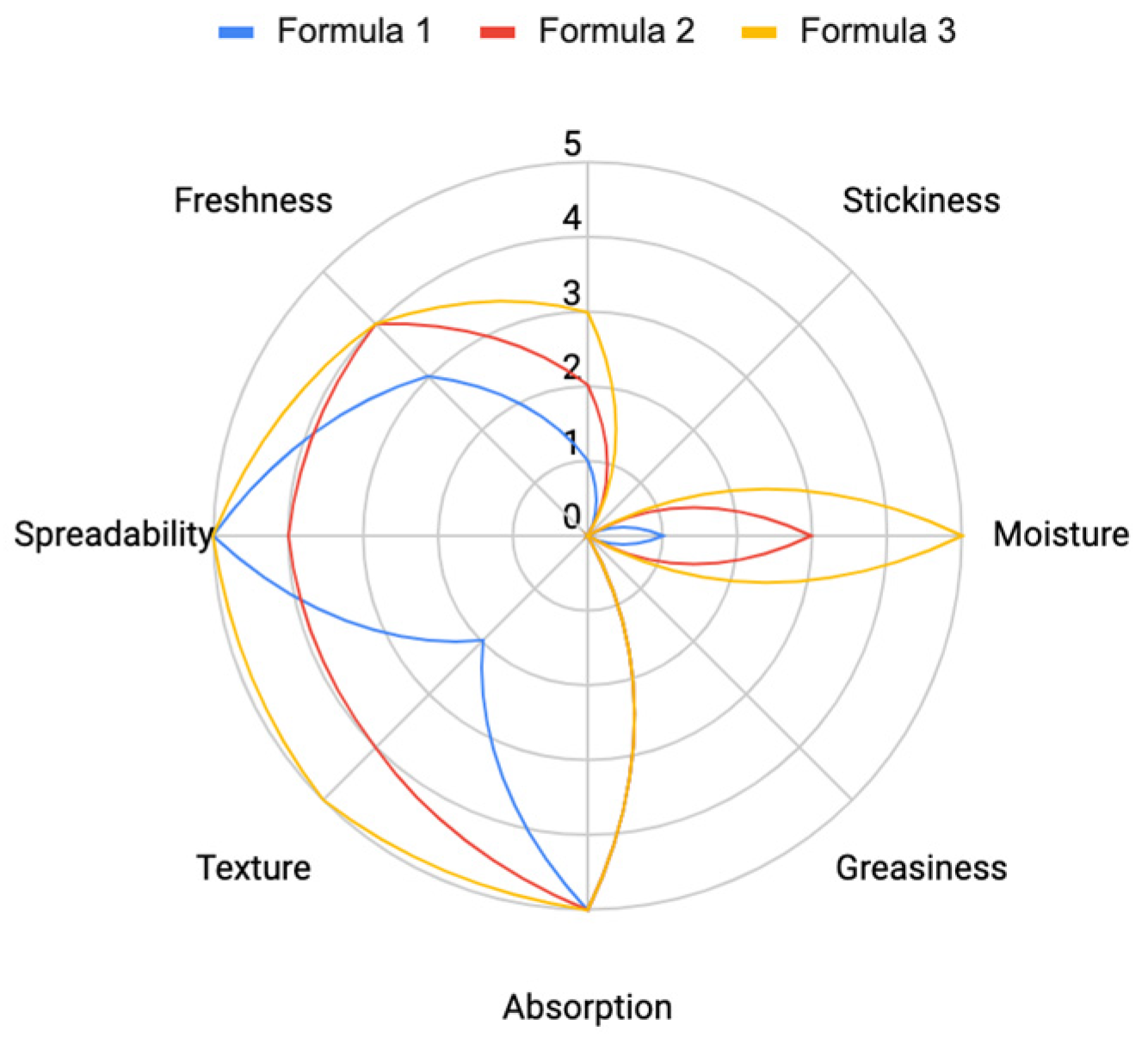

The optimal moisturizing properties of the Nano-lotion developed in this study are presented in

Table 1. Prior to this, the formulations were refined and adjusted by incorporating additional ingredients to enhance texture, functionality, and stability. Olivem

® VS Feel was utilized as an emulsion stabilizer and viscosity enhancer, functioning as both an emulsifier and a thickening agent. Polymeric nanoparticles containing 1 g of ABS Acai Sterols EFA were incorporated into the oil phase. To improve the efficacy of the base lotion, humectants and emollients such as Glycerin, Propylene Glycol, Caprylic/Capric Triglyceride, and Acai berry virgin oil were included. Both Acai berry virgin oil and ABS Acai Sterols EFA in their raw forms were employed to evaluate their short-term moisturizing effects on the skin. The addition of Acai nanoparticles in the final formulation allowed for a more straightforward comparison of efficacy. The formulation development process is detailed in

Table 2, where Formula 3 was the optimized formula, based on the sensory evaluation data (Figure 16).

To compare the efficiency of skin hydration, stability, and prolonged release, both a base lotion and an Acai lotion were formulated. The compositions of these formulations are detailed in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

4.2.4. Analytical Testing

Viscosity

The viscosity of moisturizing Nano-lotion was measured in triplicate by using a viscometer (Brookfield LVDV-II+P, Ametek Brookfield, Harlow, UK). Spindle no.64 with 10 to 35 rpm was selected under room temperature condition (25 °C).

pH Measurements

The pH of the moisturizing nano-lotion was measured at room temperature using pH test strips, with measurements conducted in triplicate. The pH stability of the nano-lotion was compared to the Acai lotion to confirm that the nano-lotion maintained an ideal pH, as expected from a stable nanoemulsion formulation.

Stability Testing

The stability of the products after storage for one month at ambient temperature was observed macroscopically by monitoring phase separation and texture changes.

4.2.5. Efficacy Test

Treatment Regimen

Five females, aged 20-30 years with normal skin types were recruited for this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants were instructed to adhere to their regular lifestyle before testing. Other hydration treatments were not permitted during the study. The control lotion (base lotion) was applied on the left hand and the Acai lotion (containing ABS Acai Sterols EFA) was applied on the right hand. After 10 minutes, moisture content was measured using the Delfin Moisturemeter SC Compact (Delfin Technologies UK Ltd., Surrey, UK) [50].

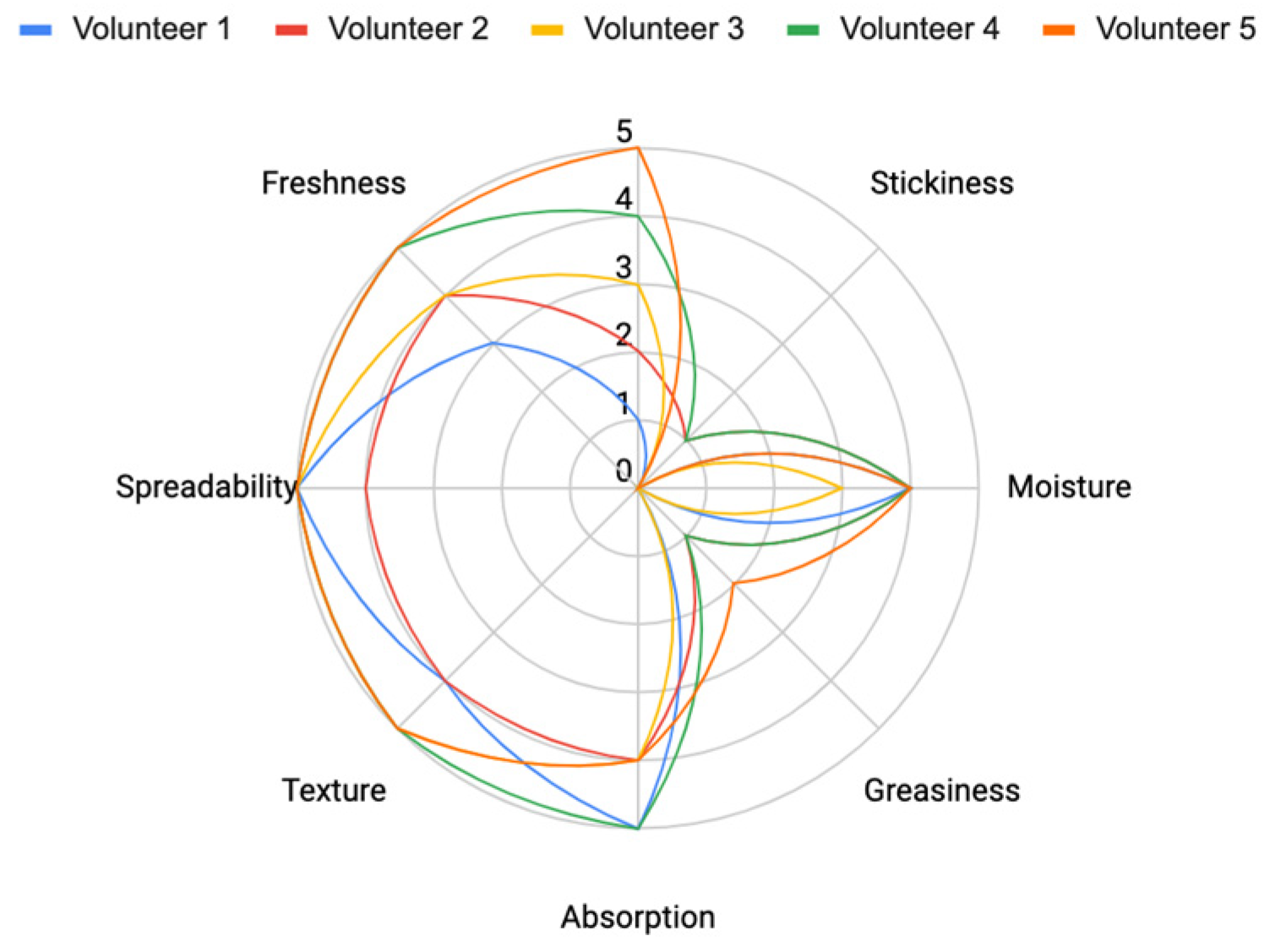

4.2.6. Sensory Evaluation

The sensory evaluation was carried out for the optimization of the three pilot formulas (Formula 1, Formula 2, and Formula 3 from

Table 2). The sensory descriptors were Freshness, Stickiness, Spreadability, Moisture, Texture, Absorption, and Greasiness. (Shown in

Figure 16)

The scores were calculated based on questions by an ordinal scale of 5: 4 = extremely agree, 3 = agree, 2 = slightly agree, 1 = slightly disagree, and 0 = disagree.

4.2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of the differences before applying and after applying Acai lotion was tested by t-test. Differences were considered to be significant at a level of P < 0.05.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Active-Loaded Nanoparticles

The results showed that 92% of the active was entrapped into the nanoparticles. Compared to the findings in the literature [29], which reported that the maximum drug encapsulation capacity is typically around 20%–30% relative to the polymer amount, the results of our study represent a significant success.

5.2. Characterisation of Active-Loaded Chitosan and Sodium Alginate Nanoparticles

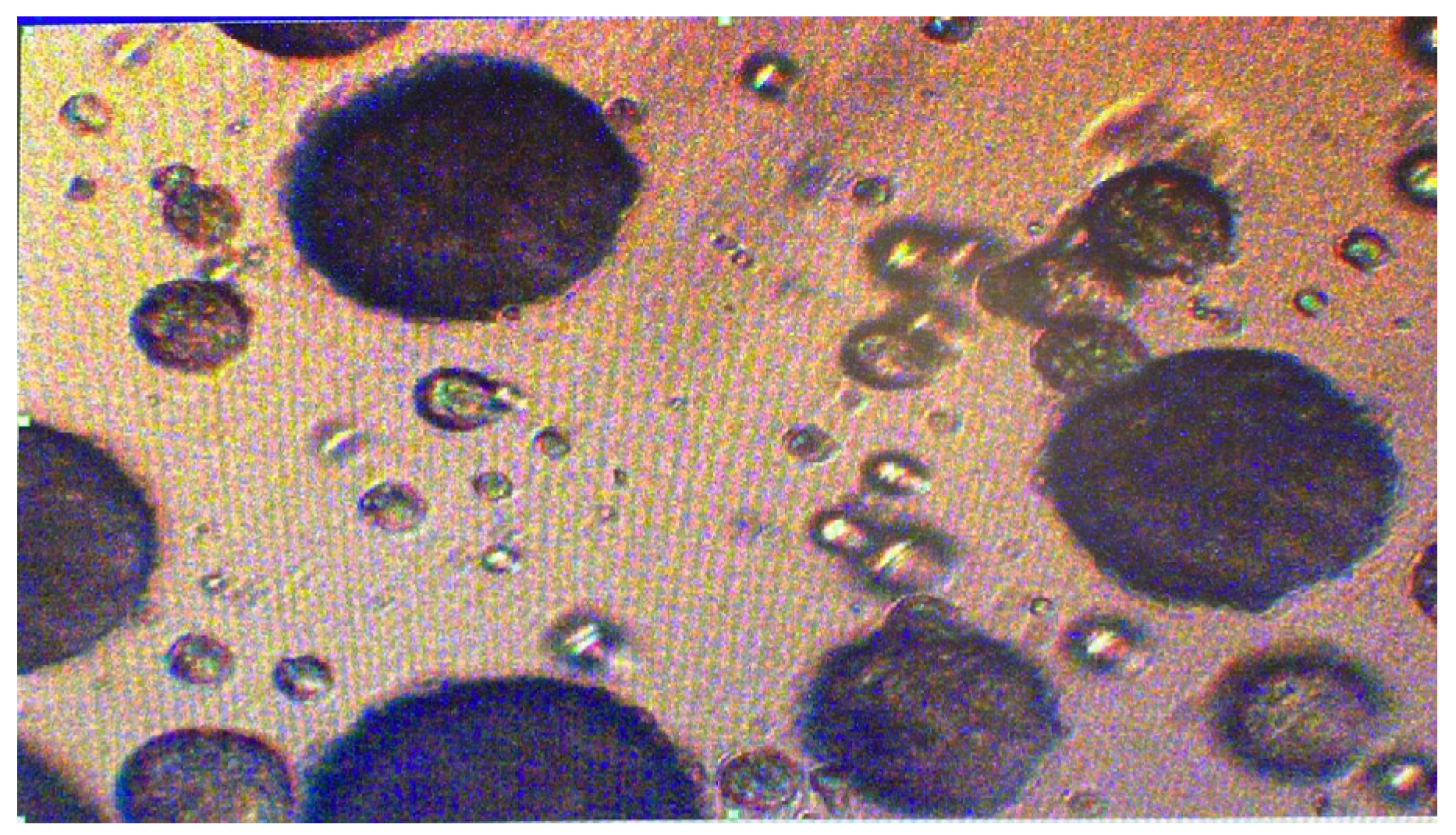

Microscopic analysis of the active-loaded CS-ALG nanoparticles revealed a distinct oval structure (

Figure 12), indicating successful encapsulation. As a result, the final product comprises well-formed CS-ALG nanoparticles with ABS Acai Sterols EFA effectively incorporated within the CS-ALG matrix, confirming the stability and integrity of the nano-delivery system. As highlighted in prior studies [21,22,23], ionic gelation offers high loading capacity but is constrained by challenges like large particle sizes; similarly, this study found that chitosan-alginate nanocapsules were larger compared to Acai lotion globules. (

Figure 13). On the other hand, the Acai lotion that was not prepared in nanoemulsion form appeared in a round shape (

Figure 14) and the texture was smooth and homogeneous (

Figure 15).

5.3. Formulation of Moisturising Nano-Lotion

The formulation was assessed through sensory evaluation, with the results indicating that

Formula 3 (as shown in

Table 2) demonstrated the best performance. It provided a strong hydrating effect, smooth texture, excellent spreadability, fast absorption, and a refreshing feel. Additionally, the volunteers rated it highly for its non-stickiness and non-greasiness (

Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Sensory Evaluation of Formulas 1, 2, and 3 based on key attributes (Spreadability, Absorption, Texture, Freshness, Moisture, Stickiness, and Greasiness).

Figure 16.

Sensory Evaluation of Formulas 1, 2, and 3 based on key attributes (Spreadability, Absorption, Texture, Freshness, Moisture, Stickiness, and Greasiness).

5.4. Analytical test of Lotion

5.4.1. Viscosity Results

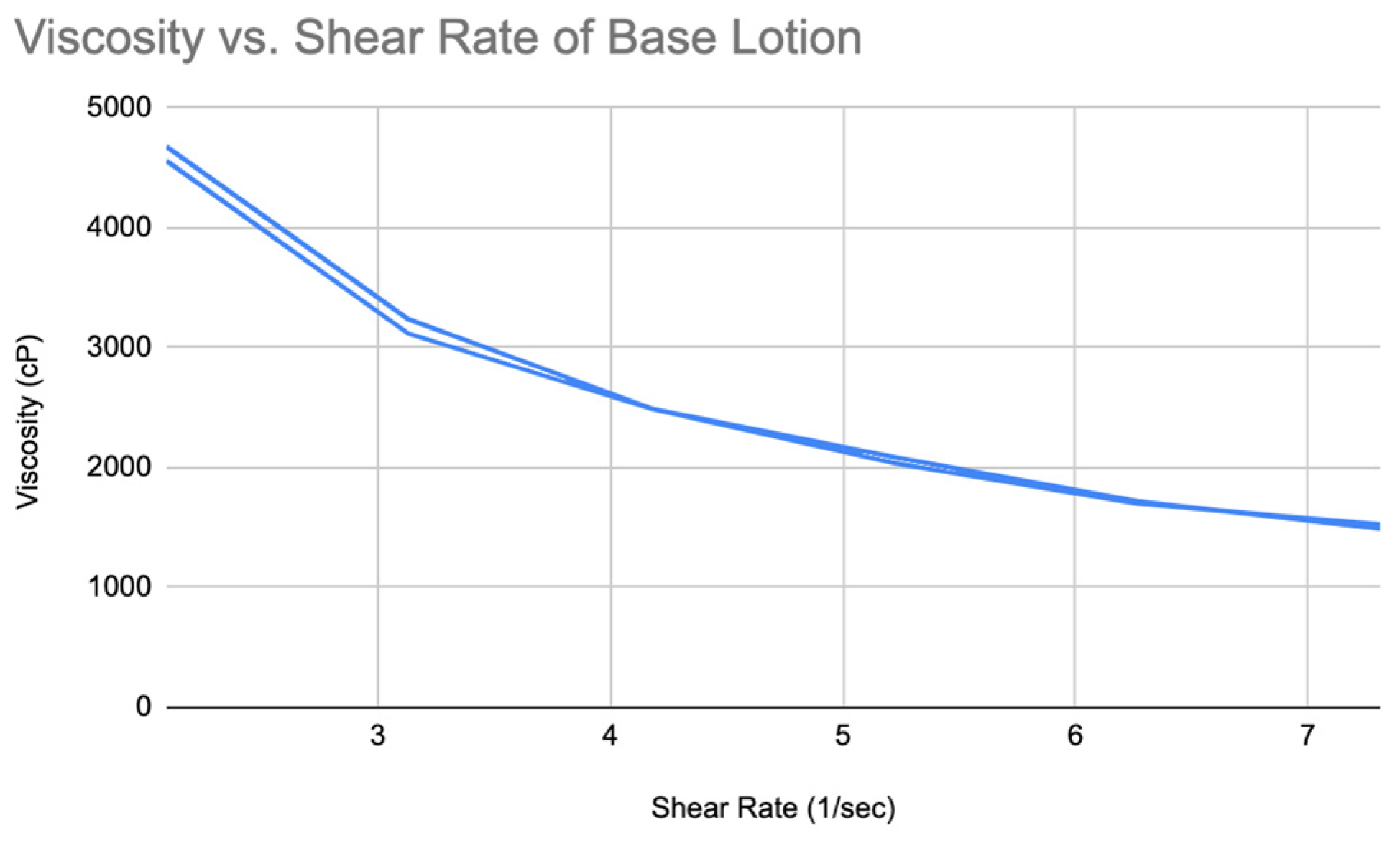

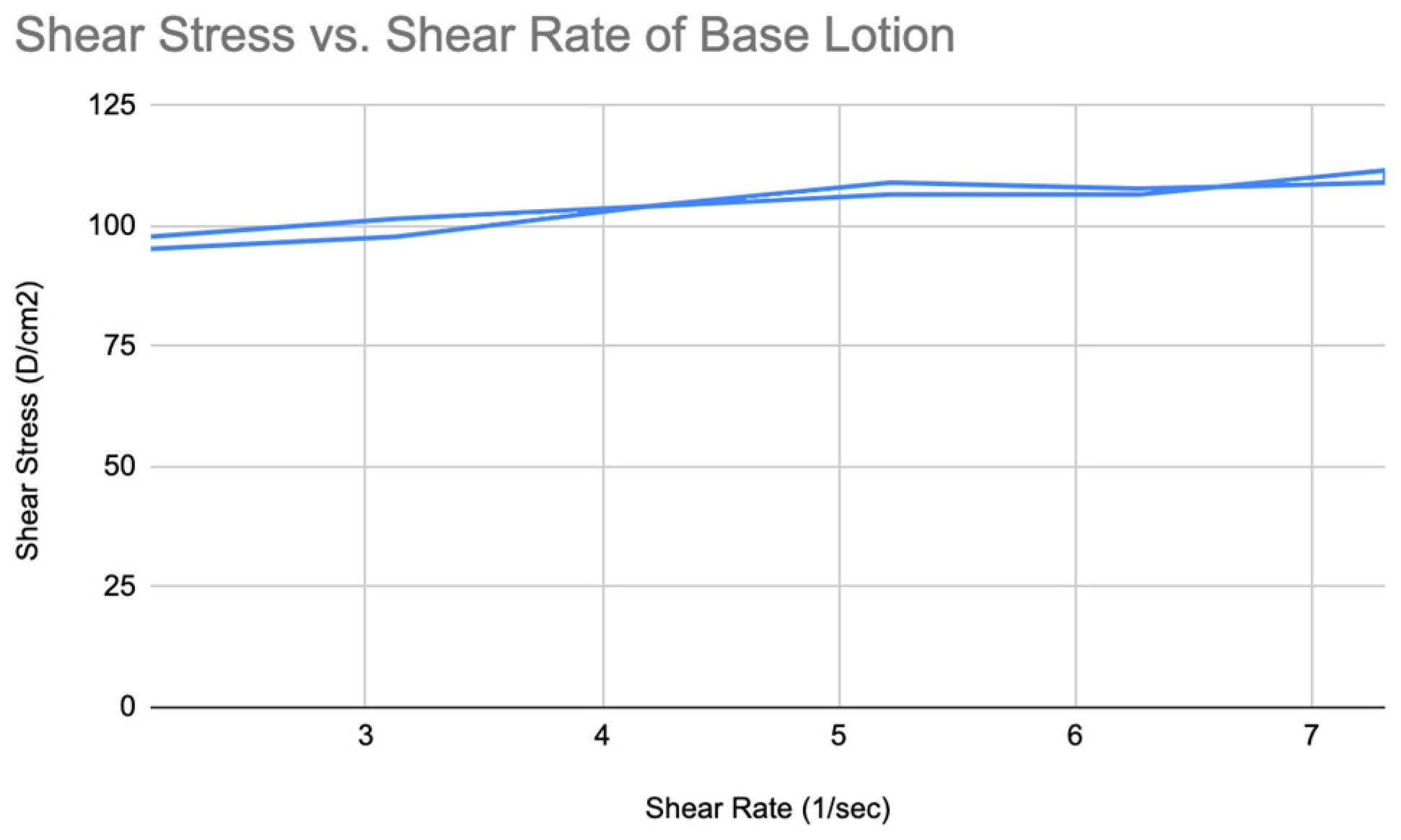

In terms of rheology, the viscosity range of Acai lotion was 1491.11 - 4679.00 cP, while moisturizing Nano-lotion was 1713.92 - 4978.94 cP.

Viscosity and Spreadability of Acai Lotion

The results showed that both formulas are non-Newtonian fluids. By plotting the rheogram, it can be seen that the viscosity of Acai lotion decreased as the shear rate increased over time. So, it is a shear-thinning fluid (

Figure 17). The viscosity values are higher at all shear rates compared to the moisturizing nano-lotion. At lower shear rates (e.g., 10 RPM), the viscosity starts at 4679 cP, decreasing to 1491 cP at 35 RPM.

Moreover, the rheogram showed that it is a slightly thixotropic fluid which is indicative of time-dependent decrease in viscosity (

Figure 18).

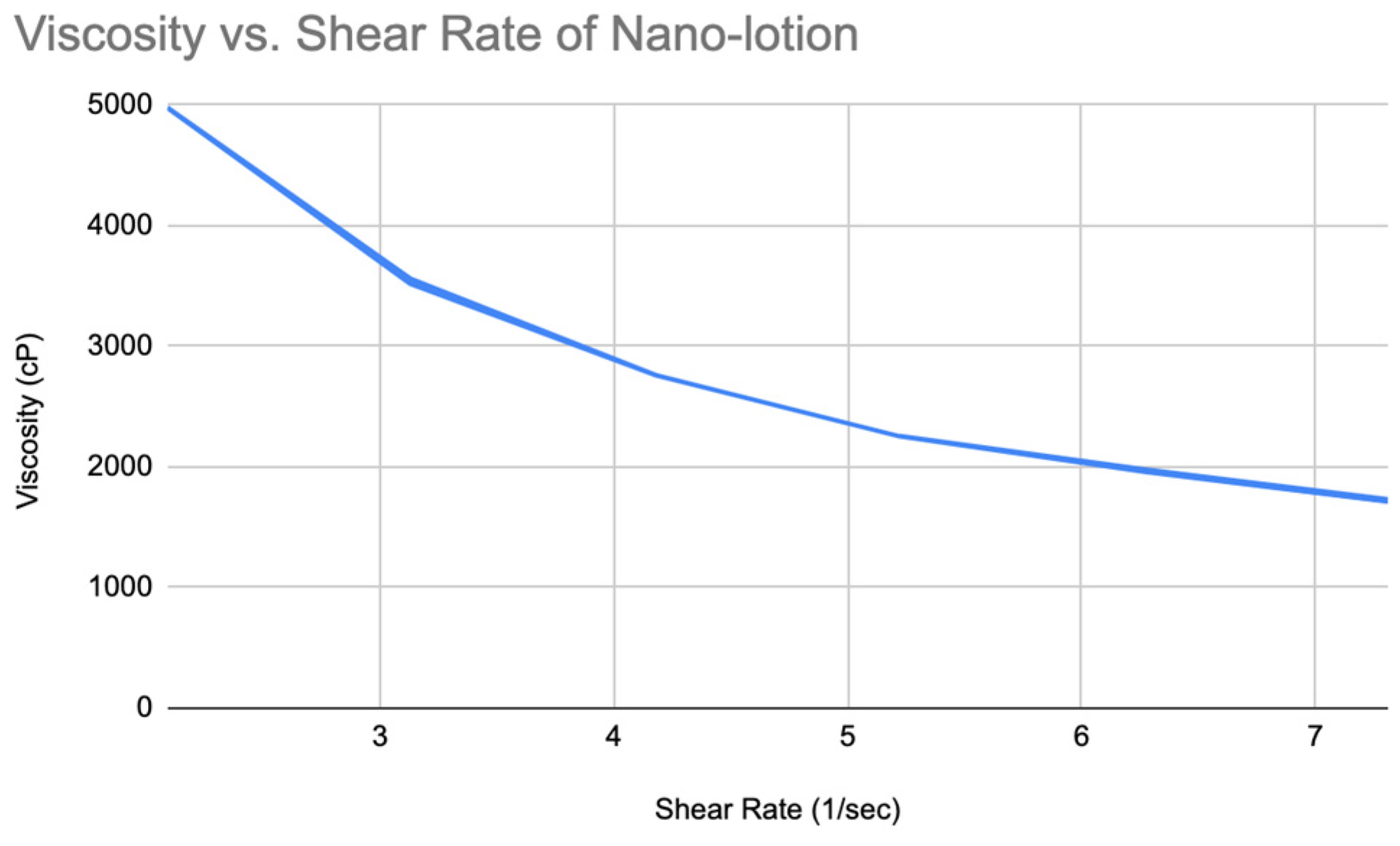

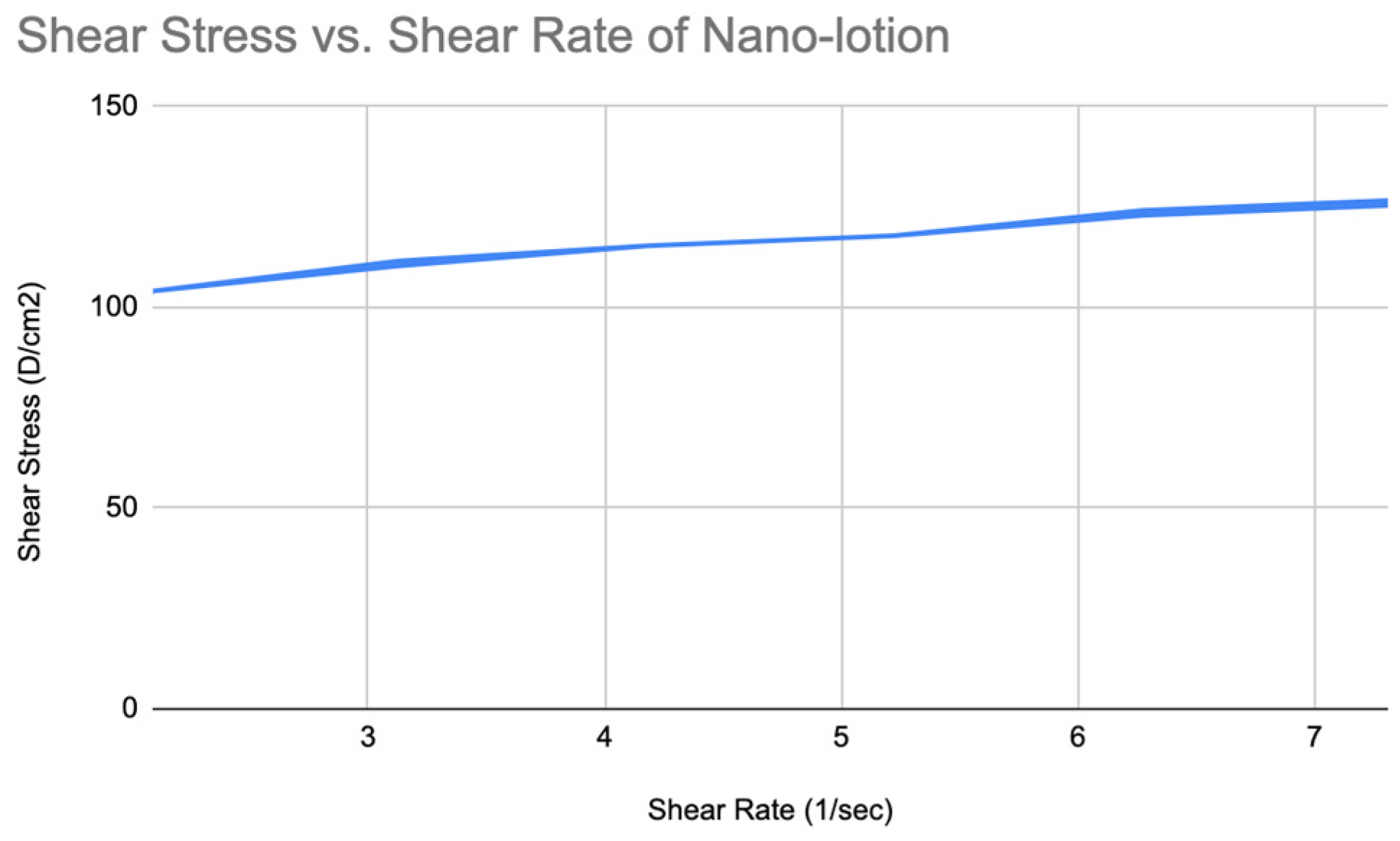

Viscosity and Spreadability of Nano Lotion

Similarly, the rheogram showed that the moisturizing nano-lotion is also a shear-thinning fluid (

Figure 19) and slightly thixotropic (

Figure 20).

The viscosity values of the nano-lotion are lower overall, indicating better spreadability and a lighter feel. At lower shear rates (e.g., 10 RPM), the viscosity starts at 4978 cP, but at higher shear rates (35 RPM), it drops to 1731 cP.

Comparison of Viscosity and Spreadability Between Acai Lotion and Nano Lotion

In terms of spreadability, the moisturizing nano-lotion (Table 6) demonstrated better spreadability due to its lower viscosity at higher shear rates, indicating it is less resistant to flow when applied.

Similarly, the lower viscosity of the moisturizing nano-lotion across a range of shear rates suggests a lighter and more user-friendly texture. The moisturizing nano-lotion (Table 6) is more lightweight and has better spreadability compared to the Acai lotion (Table 5). This makes it more suitable for cosmetic applications requiring easy application and absorption.

5.4.2. pH Measurement Result

The pH stability test confirmed that both the Acai lotion and the moisturizing nano-lotion maintained a pH of 5 for one month under ambient storage conditions, ensuring compatibility with the skin’s natural pH.

5.4.3. Stability Test Result

The stability of the product was evaluated by monitoring viscosity, pH, color, and odor changes. In terms of overall stability, neither product exhibited changes in color or odor during the testing period, demonstrating their robustness under ambient conditions. Additionally, the moisturizing nano-lotion displayed enhanced properties, including improved spreadability, lightweight texture, and superior stability due to its nanoemulsion structure, which provides better resistance to phase separation and supports prolonged product structural integrity.

5.5. Efficacy Test

5.5.1. Skin Moisturisation

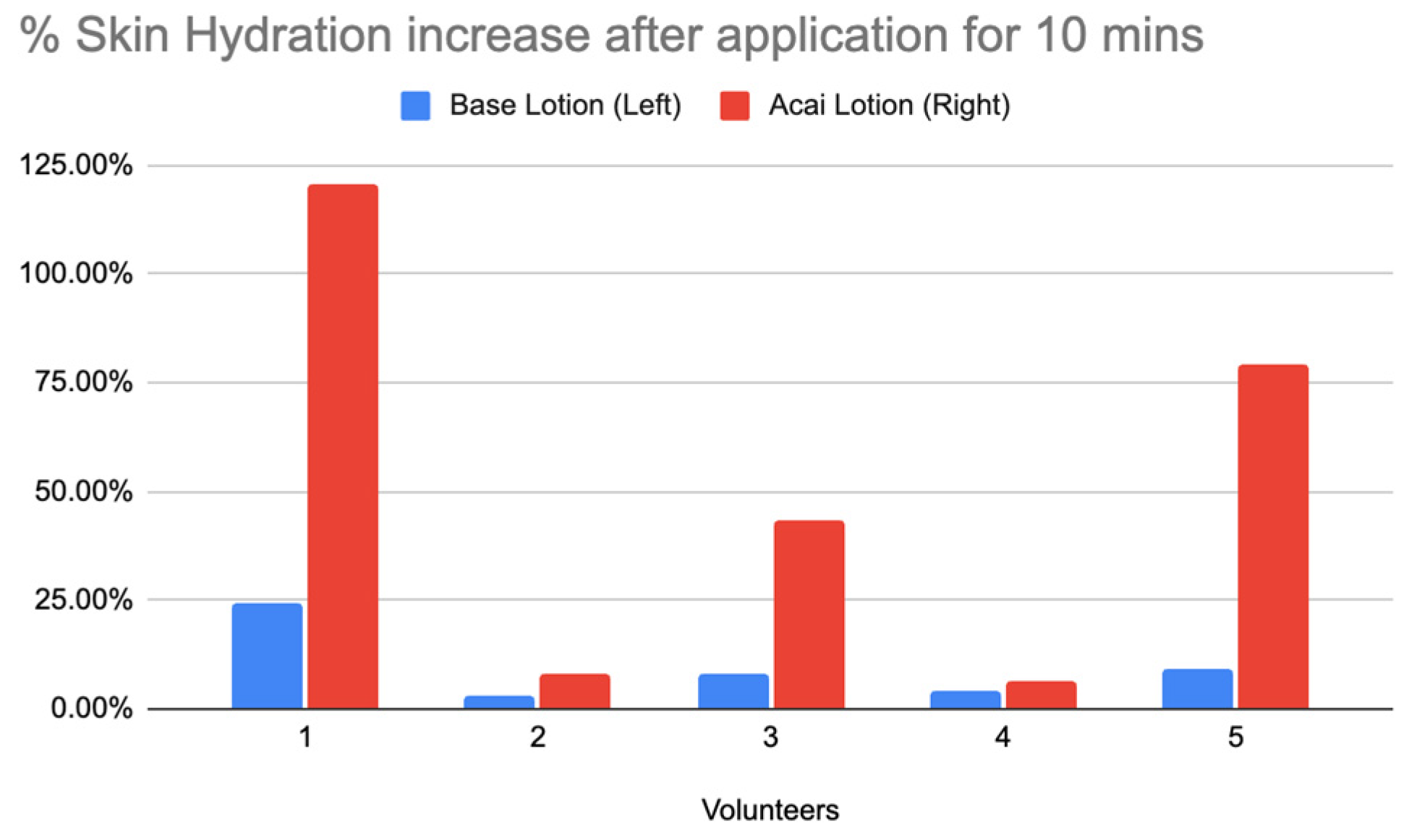

Delfin Moisturemeter SC Compact, an instrument for the determination of moisture content of the skin surface was used. After applying base lotion on the left hand and Acai-lotion on the right hand for 10 mins participants, the results showed that there was an increase in skin moisture values.

Table 7 shows the mean of skin moisture values in all participants.

Table 8 and

Figure 21 showed the percentage mean increase in skin moisturization After Application for 10 Minutes. For all volunteers, the Acai lotion shows a higher percentage increase in skin hydration compared to the base lotion. The Acai lotion consistently outperforms the base lotion across all volunteers, indicating its superior moisturizing properties.

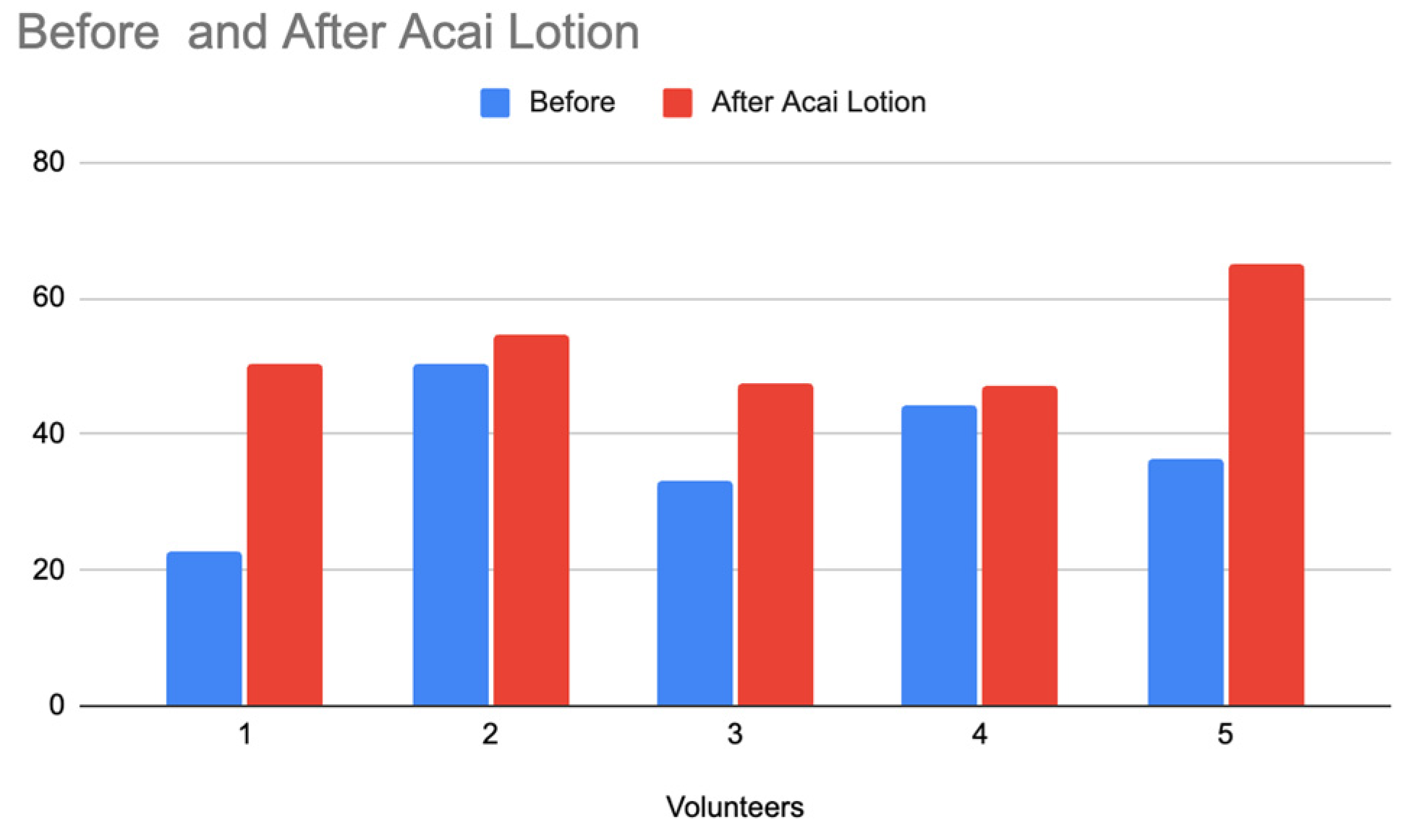

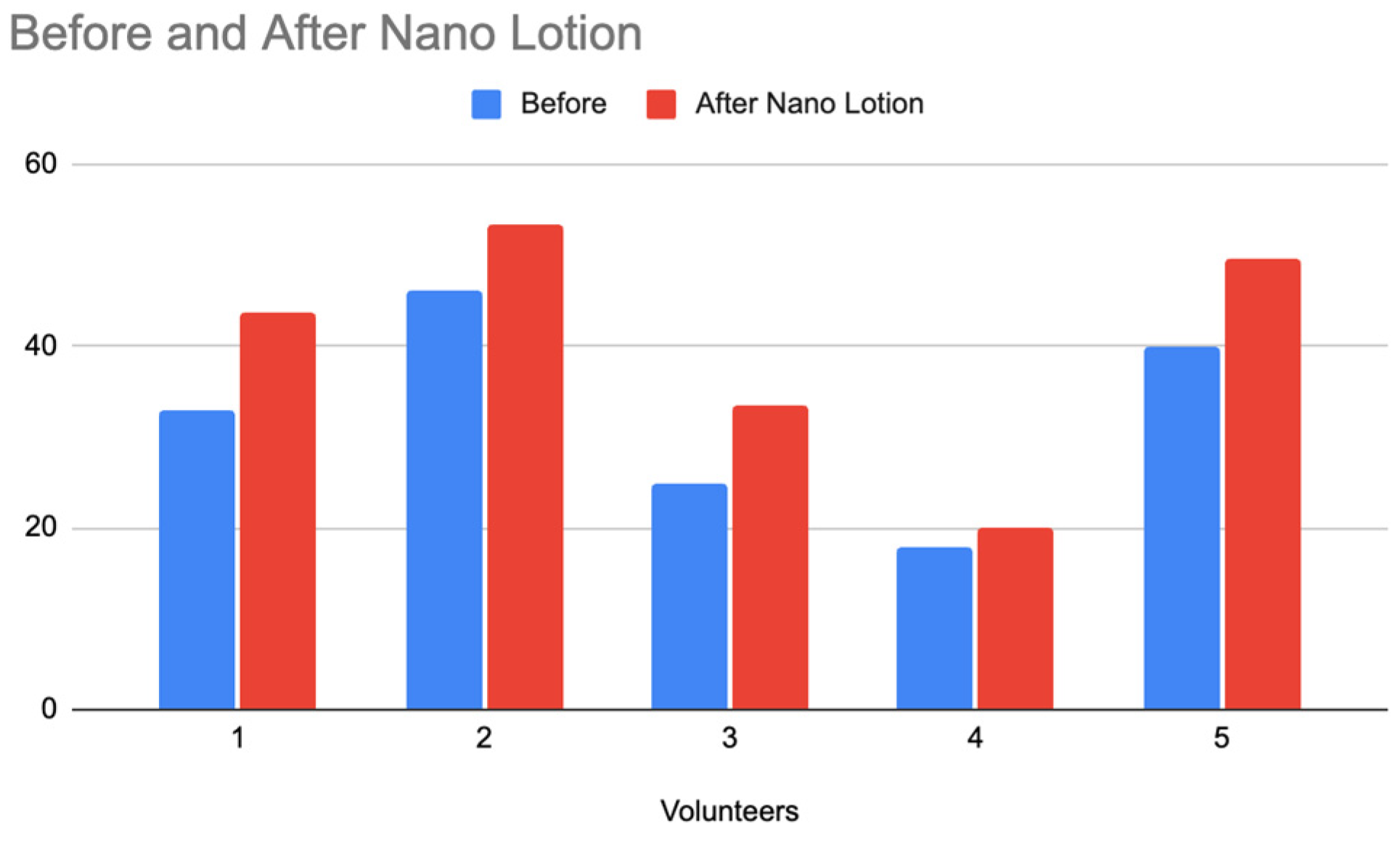

5.5.2. Observation: Prolonged Release Effect of Nano-Lotion Compared to Acai Lotion

To extend the study, the release behavior of the nano-lotion was monitored using the Delfin MoistureMeter SC Compact, a device designed to measure the moisture content on the skin’s surface. This instrument was employed to evaluate and compare the hydration effects of the Acai lotion and the nano-lotion for 10 minutes, providing insights into the prolonged release properties of the nano-lotion formulation. The results of skin hydration levels before and after applying the Acai lotion

Figure 22) and the nano-lotion (

Figure 23) )with each formulation containing 1g of ABS Acai Sterols EFA) indicate a notable difference in hydration retention between the two formulations, emphasizing the prolonged release effect of the nano-lotion. Both the Acai lotion and the nano-lotion showed an increase in hydration levels after application. However, the Acai lotion displays a more immediate increase in hydration. Although the nano-lotion shows a slightly lower hydration increase initially compared to the Acai lotion, it is expected to maintain hydration levels for a longer period due to its controlled, prolonged release mechanism. Nano-lotion formulations are designed to release active ingredients gradually, ensuring sustained hydration over time, whereas regular lotions tend to show a more immediate but short-lived effect.

To fully understand the prolonged release and sustained hydration benefits of the nano-lotion, it is recommended to extend the study period beyond the initial 10-minute observation. Conducting a longer-term evaluation over several hours or days would provide valuable insights into how the nano-lotion maintains skin hydration compared to the Acai lotion over time. This extended study would allow for a more accurate assessment of the nano-lotion’s prolonged release properties and its effectiveness in delivering consistent hydration, which is a key advantage of nanoparticle-based formulations.

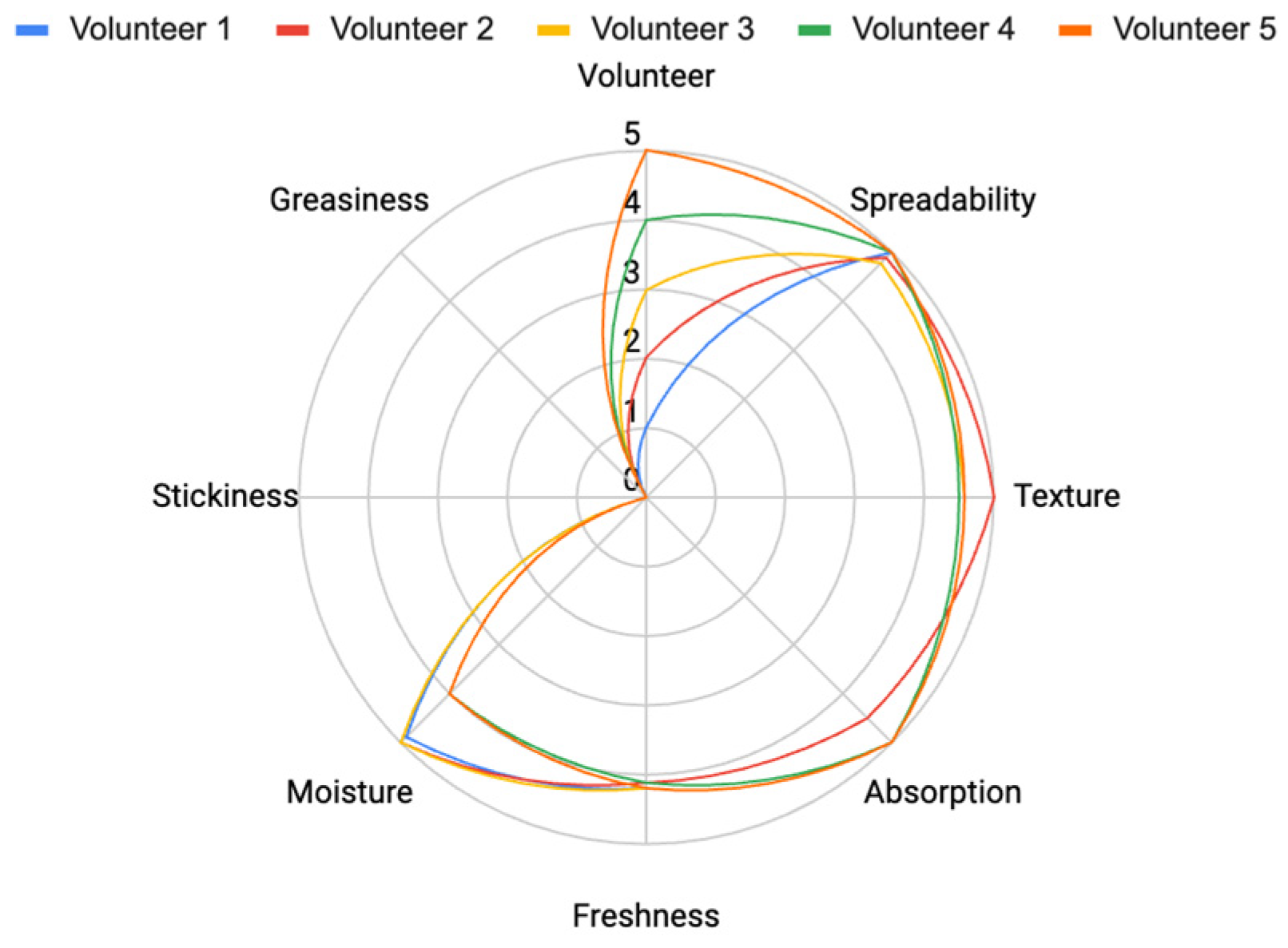

5.6. Satisfaction and Sensory Evaluation

5.6.1. The Satisfaction of Acai Lotion

The evaluation of the Acai lotion demonstrated excellent performance across various sensory parameters (

Figure 24), with high scores for spreadability (4.8), texture (4.6), absorption (4.4), freshness (4.2), and moisture (3.8). Additionally, minimal levels of stickiness (0.4) and greasiness (0.8) further highlight its suitability as a moisturizing product. These results underscore the effectiveness of the Acai lotion in delivering desirable properties for skincare applications.

5.6.2. The Satisfaction of Nano Lotion Containing Acai Oil

The sensory evaluation scores for the nano-Lotion have been extracted and displayed (Figure 25). The results indicate that the Nano-Lotion scored higher for spreadability and absorption compared to regular Acai lotion. Additionally, it shows minimal levels of stickiness and greasiness, making it a more lightweight and user-friendly formulation with high scores for spreadability (4.9), texture (4.7), absorption (4.9), freshness (4.2), moisture (4.6), non-stickiness (0) and non-greasiness (0).

Although the study focused exclusively on the Acai lotion, further evaluation of the nano-lotion is warranted to explore its potential enhanced benefits, including prolonged release, better skin penetration, and improved hydration performance. Conducting a direct comparison between the two formulations in future studies would provide valuable insights into the advantages of nano-encapsulation and further validate the use of Acai in advanced cosmetic formulations.

5.7. Statistical Analysis Result

The statistical significance of the differences between before and after application of Acai lotion was tested by t-test. Differences were considered to be significant at a level of P < 0.05 (

Table 9).

From the experimental results, it can be seen that the average skin hydration of the 5 volunteers before applying Acai lotion is equal to 37.34, while after applying Acai lotion is equal to 52.9 The paired t-test determines whether the mean difference of a pair of measurements is equal to zero. By setting the significance level (p-value) equal to 0.05 or the corresponding confidence level is 95%, the null hypothesis is the mean of the paired differences equals zero, as the alternative hypothesis does not equal zero. The result shows that the t-Stat is greater than the t-Critical value, then the null hypothesis is rejected and the alternate hypothesis is accepted. While P is less than the specified confidence level (P< 0.05) that deviation from the null hypothesis is considered to be statistically significant. This indicates that the application of the lotion resulted in a meaningful and measurable improvement in skin hydration. In addition, Acai is also well known for anti-aging. Hence, further study should evaluate the skin elasticity, surface evaluation of living skin, striae surface wrinkles, and skin smoothness for the claim substantiation.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the remarkable potential of acai oil as a key ingredient in developing advanced moisturizing formulations. The results demonstrated that the incorporation of acai oil into a nano-lotion significantly improved skin hydration, as evidenced by the noticeable increase in hydration levels after just 10 minutes of application. The nano-lotion, leveraging the encapsulation of acai oil, exhibited excellent stability in terms of pH, viscosity, color, and odor over an extended period, reflecting its robust formulation. Furthermore, the nano- lotion’s light texture, rapid absorption, and prolonged release profile ensured superior performance compared to the base lotion, aligning with consumer expectations for high-quality cosmetic products. The rich composition of açaí oil—abundant in omega-6 fatty acids, anthocyanins, and polyphenols—proved effective in enhancing skin hydration, elasticity, and overall skin health. This study not only underscores the efficacy of acai oil as a potent moisturizing agent but also bridges the gap between traditional natural remedies and modern cosmetic science through innovative nanotechnology. With its proven stability and skin-enhancing properties, acai oil nano-lotion offers a promising avenue for the development of high-performance, natural-based skincare products, paving the way for further exploration of acai’s potential in the cosmetic industry.

References

- Liu, J.; Xu, D.; Chen, S.; Yuan, F.; Mao, L.; Gao, Y. Superfruits in China: Bioactive Phytochemicals and Their Potential Health Benefits—A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 6892–6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakelyan, H.S. Acai Berry and Immune System. ResearchGate, 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343362060_Acai_Berry_and_Immune_System (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Censi, R.; et al. Cosmetic Formulation Based on an Açai Extract. Cosmetics 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y. Asian Berries: Health Benefits; CRC Press: Boca Raton, USA, 2021; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.H.; Choi, S.; Kim, B.-H. Skin Wound Healing Effects and Action Mechanism of Acai Berry Water Extracts. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, S.; et al. A Review of the Potential Benefits of Plants Producing Berries in Skin Disorders. Antioxidants 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotenoids and anthocyanins are among the most important pigments in berries. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2018, 17, 1135–1155. [CrossRef]

- Puglia, C.; Offerta, A.; Trombetta, D.; Saija, A.; Bonina, F. New Trends in Cosmetics: By-Products of Plant Origin and Their Potential Use as Cosmetic Active Ingredients. Cosmetics 2015, 2, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumers Prefer Natural More for Preventatives Than for Curatives. Journal of Consumer Research 2020, 47, 895–914. [CrossRef]

- Vidhya, D.V.; Keerthana, M. A Study on Consumer Preference towards Cosmetics with Reference to Coimbatore City. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews 2023, 4, 2763–2769. [Google Scholar]

- Detsi, A.; Kavetsou, E.; Kostopoulou, I.; Pitterou, I.; Pontillo, A.R.N.; Tzani, A.; Christodoulou, P.; Kefalas, P.; Pappas, C.; Lamari, F.N. Nanosystems for the Encapsulation of Natural Products: The Case of Chitosan Biopolymer as a Matrix. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pateiro, M.; Gómez, B.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Barba, F.J.; Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Lorenzo, J.M. Nanoencapsulation of Promising Bioactive Compounds to Improve Their Absorption, Stability, Functionality and the Appearance of the Final Food Products. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; et al. Chitosan-Alginate Nanoparticles as a Novel Drug Delivery System for Nifedipine. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2008, 4, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.C.F.; et al. Chitosan: An Update on Potential Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5156–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate: Properties and Biomedical Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Kashdan, T.; Sterner, C.; Dombrowski, L.; Petrick, I.; Kröger, M.; Höfer, R. Chapter 2—Algal Biorefineries. In Industrial Biorefineries & White Biotechnology; Pandey, A., Höfer, R., Taherzadeh, M., Nampoothiri, K.M., Larroche, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 35–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lertsutthiwong, P.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Nimmannit, U. Preparation of Turmeric Oil-Loaded Chitosan-Alginate Biopolymeric Nanocapsules. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2009, 29, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, P.; Upadhyay, T.K.; Alshammari, N.; Saeed, M.; Kesari, K.K. Alginate-Chitosan Biodegradable and Biocompatible Based Hydrogel for Breast Cancer Immunotherapy and Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 3515–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Singh, V.K.; Dwivedy, A.K.; Chaudhari, A.K.; Upadhyay, N.; Singh, P.; Sharma, S.; Dubey, N.K. Encapsulation in Chitosan-Based Nanomatrix as an Efficient Green Technology to Boost the Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and In Situ Efficacy of Coriandrum sativum Essential Oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubiev, O.M.; Egorov, A.R.; Kirichuk, A.A.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; Kritchenkov, A.S. Chitosan-Based Antibacterial Films for Biomedical and Food Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Singh, V.K.; Dwivedy, A.K.; Chaudhari, A.K.; Upadhyay, N.; Singh, P.; Sharma, S.; Dubey, N.K. Encapsulation in Chitosan-Based Nanomatrix as an Efficient Green Technology to Boost the Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and In Situ Efficacy of Coriandrum sativum Essential Oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetta, A.; Kegere, J.; Mamdouh, W. Comparative Study of Encapsulated Peppermint and Green Tea Essential Oils in Chitosan Nanoparticles: Encapsulation, Thermal Stability, In-Vitro Release, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyzioglu, G.C.; Tornuk, F. Development of Chitosan Nanoparticles Loaded with Summer Savory (Saturejahortensis L.) Essential Oil for Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Delivery Applications. LWT 2016, 70, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayan, G.; Kayan, A. Composite of Natural Polymers and Their Adsorbent Properties on the Dyes and Heavy Metal Ions. J. Polym. Environ. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alginate. Comprehensive Biotechnology, 3rd ed.; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhodub, L.B.; Yanovska, G.O.; Sukhodub, L.F. Injectable Biopolymer-Hydroxyapatite Hydrogels: Obtaining and Their Characterization. Journal of Nano- and Electronic Physics. 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wathoni, N.; Herdiana, Y.; Suhandi, C.; Mohammed, A.; Elrayyes, A.; Narsa, A. Chitosan/Alginate-Based Nanoparticles for Antibacterial Agents Delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 5021–5044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, G.; Jin, S.; Xu, L.; Zhao, C.X. Development of High-Drug-Loading Nanoparticles. Chempluschem 2020, 85, 2143–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alginate-Based Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 49–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acai Pulp Oil. The Toxic-Free Foundation. Figure 1: Acai Pulp Image. Available online: https://thetoxicfreefoundation.com/database/ingredient/acai-pulp-oil (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- de Paula, R.C.; de Figueiredo-Ribeiro, C.L.; de Moraes Rocha, G.J.; de Brito, E.S.; Macedo, G.R.; Rodrigues, T.H.S.; Gonçalves, L.R.B. High Concentration and Yield Production of Mannose from Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) Seeds via Mannanase-Catalyzed Hydrolysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.R.; Guedes, D.; Marques de Paula, U.L.; de Oliveira, M.; Lutterbach, M.T.S.; Reznik, L.Y.; Sérvulo, E.F.C.; Alviano, C.S.; Ribeiro da Silva, A.J.; Alviano, D.S. Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) Seed Extracts from Different Varieties: A Source of Proanthocyanidins and Eco-Friendly Corrosion Inhibition Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, P.R.; da Costa, C.A.; de Bem, G.F.; Cordeiro, V.S.; Santos, I.B.; de Carvalho, L.C.; da Conceição, E.P.; Lisboa, P.C.; Ognibene, D.T.; Sousa, P.J.; et al. Euterpe oleracea Mart.-Derived Polyphenols Protect Mice from Diet-Induced Obesity and Fatty Liver by Regulating Hepatic Lipogenesis and Cholesterol Excretion. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, M.O.; Silva, M.; Silva, M.E.; Oliveira, R.P.; Pedrosa, M.L. Diet Supplementation with Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) Pulp Improves Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and the Serum Lipid Profile in Rats. Nutrition 2010, 26, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens-Talcott, S.U.; Rios, J.; Jilma-Stohlawetz, P.; Pacheco-Palencia, L.A.; Meibohm, B.; Talcott, S.T.; Derendorf, H. Pharmacokinetics of Anthocyanins and Antioxidant Effects After the Consumption of Anthocyanin-Rich Açaí Juice and Pulp (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) in Healthy Human Volunteers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7796–7802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Palencia, L.A.; Talcott, S.T.; Safe, S.; Mertens-Talcott, S. Absorption and Biological Activity of Phytochemical-Rich Extracts from Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) Pulp and Oil In Vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 3593–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deveoglu, O.; Karadag, R. Polyphenols as Colorants. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Pure Sciences 2019, 31, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveoglu, O.; Karadag, R. A Review on the Flavonoids—A Dye Source. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Pure Sciences 2019, 31, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- β-Cryptoxanthin. Carotenoid Database, Figure 1. Available online: http://carotenoiddb.jp/Entries/CA00312.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.S. Carotenoid Extraction Methods: A Review of Recent Developments. In Natural Products from Plants: Methods and Protocols; Sarker, S.D., Nahar, L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.M.; Gonçalves, E.C.S.; Salgado, J.C.S.; Rocha, M.S.; Almeida, P.Z.; Vici, A.C.; Infante, J.C.; Guisán, J.M.; de Almeida, M.A.; de Oliveira, A.H.C.; et al. Production of Omegas-6 and 9 from the Hydrolysis of Açaí and Buriti Oils by Lipase Immobilized on a Hydrophobic Support. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuricic, I.; Calder, P.C. Beneficial Outcomes of Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Human Health: An Update for 2021. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashiwagi, S.; Huang, P.L. Dietary Supplements and Cardiovascular Disease: What is the Evidence and What Should We Recommend. In Cardiovascular Risk Factors; Wang, H., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmowafy, E.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Ahmed, M.A.; Ahmed, S.M.; El-Shamy, A.E.; Mohamed, S.A. Stable Colloidal Chitosan/Alginate Nanocomplexes: Fabrication, Formulation Optimization, and Repaglinide Loading. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 520–525. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, F.L.; Shyu, S.S.; Lee, S.T.; Wong, T.B. Kinetic Study of Chitosan-Tripolyphosphate Complex Reaction and Acid-Resistant Properties of the Chitosan-Tripolyphosphate Gel Beads Prepared by in Liquid Curing Method. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 74, 1868–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Q.; Xie, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L. Chitosan-Based Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, 118956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What is the Difference Between Loading Capacity and Loading Efficiency? ResearchGate. (accessed on 12 September 2015).

- Sahoo, S.K.; Labhasetwar, V. Nanotech Approaches to Delivery and Imaging Drug. In Nanotechnology in Drug Delivery; Thassu, D., Deleers, M., Pathak, Y., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Patil, R.; Ren, Y.; Shyam, R.; Wong, P.; Mao, H.Q. Enhanced Stability and Knockdown Efficiency of Poly(ethylene glycol)-Polyphosphoramidate/siRNA Micellar Nanoparticles by Co-condensation with Sodium Triphosphate. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonté, F. Skin Moisturization Mechanisms: New Data. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2011, 33, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 12.

Microscopy of the ABS Acai Sterols EFA-loaded CS-ALG nanoparticles (100x magnification).

Figure 12.

Microscopy of the ABS Acai Sterols EFA-loaded CS-ALG nanoparticles (100x magnification).

Figure 13.

The appearance of ABS Acai Sterols EFA-loaded CS-ALG nanoparticles.

Figure 13.

The appearance of ABS Acai Sterols EFA-loaded CS-ALG nanoparticles.

Figure 14.

Microscopy of the Acai lotion (100x magnification).

Figure 14.

Microscopy of the Acai lotion (100x magnification).

Figure 15.

The appearance of Acai lotion.

Figure 15.

The appearance of Acai lotion.

Figure 17.

Viscosity vs shear rate of Acai lotion.

Figure 17.

Viscosity vs shear rate of Acai lotion.

Figure 18.

Shear stress vs shear rate of Acai lotion.

Figure 18.

Shear stress vs shear rate of Acai lotion.

Figure 19.

The chart of viscosity vs shear rate of Nano-lotion.

Figure 19.

The chart of viscosity vs shear rate of Nano-lotion.

Figure 20.

The chart of shear stress vs shear rate of Nano-lotion.

Figure 20.

The chart of shear stress vs shear rate of Nano-lotion.

Figure 21.

Bar Chart of % Skin Hydration Increase After Application for 10 Minutes.

Figure 21.

Bar Chart of % Skin Hydration Increase After Application for 10 Minutes.

Figure 22.

Comparison of Skin Hydration Before and After Applying Acai Lotion.

Figure 22.

Comparison of Skin Hydration Before and After Applying Acai Lotion.

Figure 23.

Comparison of Skin Hydration Before and After Applying Nano Lotion.

Figure 23.

Comparison of Skin Hydration Before and After Applying Nano Lotion.

Figure 24.

Satisfaction evaluation after applying Acai lotion.

Figure 24.

Satisfaction evaluation after applying Acai lotion.

Figure 25.

Satisfaction evaluation after applying Nano lotion.

Figure 25.

Satisfaction evaluation after applying Nano lotion.

Table 1.

List of ingredients and their function in Acai Nano-lotion.

Table 1.

List of ingredients and their function in Acai Nano-lotion.

| Phase |

Ingredients |

Content (%w/w) |

Function |

| A |

DI Water |

q.s. to 100 |

Solvent |

| |

Glycerin |

6.00 |

Humectant |

| |

Xanthan Gum |

0.50 |

Gelling Agent |

| |

EDTA |

0.10 |

Chelating Agent |

| |

Propylene Glycol |

4.00 |

Humectant |

| B |

Caprylic/Capric |

4.00 |

Emollient |

| |

Triglyceride |

|

|

| |

Olivem® VS Feel |

5.00 |

Emulsifier |

| |

Acai Berry |

2.00 |

Emollient |

| |

Virgin Oil |

|

|

| |

ABS Acai Sterols |

1.00 |

Active |

| |

EFA Nanoparticles |

|

|

| C |

Phenoxyethanol |

0.50 |

Preservative |

Table 2.

Development of moisturizing Nano-lotion containing ABS Acai Sterol EFA.

Table 2.

Development of moisturizing Nano-lotion containing ABS Acai Sterol EFA.

| Phase |

Ingredients |

Content (%w/w) |

| |

|

F1 |

F2 |

F3 |

| A |

DI Water |

q.s. to 100 |

q.s. to 100 |

q.s. to 100 |

| |

Glycerin |

5.00 |

5.00 |

6.00 |

| |

Xanthan Gum |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

| |

EDTA |

0.10 |

0.10 |

0.10 |

| |

Propylene Glycol |

- |

4.00 |

4.00 |

| B |

Caprylic/Capric |

- |

2.00 |

4.00 |

| |

Triglyceride |

|

|

|

| |

Olivem® VS Feel |

5.00 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

| |

Acai Berry |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

| |

Virgin Oil |

|

|

|

| C |

Phenoxyethanol |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

Table 3.

List of ingredients and their function in Base lotion.

Table 3.

List of ingredients and their function in Base lotion.

| Phase |

Ingredients |

Content (%w/w) |

Function |

| A |

DI Water |

q.s. to 100 |

Solvent |

| |

Glycerin |

6.00 |

Humectant |

| |

Xanthan Gum |

0.50 |

Gelling Agent |

| |

EDTA |

0.10 |

Chelating Agent |

| |

Propylene Glycol |

4.00 |

Humectant |

| B |

Caprylic/Capric |

4.00 |

Emollient |

| |

Triglyceride |

|

|

| |

Olivem® VS Feel |

5.00 |

Emulsifier |

| C |

Phenoxyethanol |

0.50 |

Preservative |

Table 4.

List of ingredients and their function in Acai Nano-lotion.

Table 4.

List of ingredients and their function in Acai Nano-lotion.

| Phase |

Ingredients |

Content (%w/w) |

Function |

| A |

DI Water |

q.s. to 100 |

Solvent |

| |

Glycerin |

6.00 |

Humectant |

| |

Xanthan Gum |

0.50 |

Gelling Agent |

| |

EDTA |

0.10 |

Chelating Agent |

| |

Propylene Glycol |

4.00 |

Humectant |

| B |

Caprylic/Capric |

4.00 |

Emollient |

| |

Triglyceride |

|

|

| |

Olivem® VS Feel |

5.00 |

Emulsifier |

| |

ABS Acai Sterols |

1.00 |

Active |

| |

EFA |

|

|

| C |

Phenoxyethanol |

0.50 |

Preservative |

Table 7.

Mean ± SD of skin moisture values in all participants.

Table 7.

Mean ± SD of skin moisture values in all participants.

| Volunteers |

Before Left |

After Left |

Before Right |

After Right |

| 1 |

22.5 ± 1.18 |

28 ± 1.37 |

22.8 ± 0.47 |

50.3 ± 2.99 |

| 2 |

49.1 ± 2.47 |

50.5 ± 2.75 |

50.3 ± 3.77 |

54.5 ± 2.27 |

| 3 |

27.5 ± 0.78 |

29.7 ± 1.14 |

33.1 ± 1.53 |

47.5 ± 1.61 |

| 4 |

45.4 ± 1.28 |

47.4 ± 0.8 |

44.2 ± 1.08 |

47.1 ± 1.87 |

| 5 |

38 ± 2.91 |

41.5 ± 1.22 |

36.3 ± 1.2 |

65.1 ± 0.96 |

Table 8.

Skin Hydration Increase in Percentage After Application for 10 Minutes.

Table 8.

Skin Hydration Increase in Percentage After Application for 10 Minutes.

| % Skin Hydration increases after application for 10 minutes |

|---|

| Volunteers |

Base Lotion (Left) |

Acai Lotion (Right) |

| 1 |

24.44% |

120.61% |

| 2 |

2.85% |

8.35% |

| 3 |

8% |

43.50% |

| 4 |

4.40% |

6.56% |

| 5 |

9.21% |

79.34% |

Table 9.

The paired t-test of the average before and after applying Acai lotion.

Table 9.

The paired t-test of the average before and after applying Acai lotion.

| t-Test: Paired Two Sample for Mean |

|---|

| |

Before |

After |

| Mean |

37.34 |

52.9 |

| Variance |

111.373 |

55.24 |

| Observations |

5 |

5 |

| Pearson Correlation |

0.09230426579 |

|

| Hypothesized Mean Difference |

0 |

|

| df |

4 |

|

| t Stat |

-2.820868753 |

|

| P(T<=t) one-tail |

0.02389296644 |

|

| t Critical one-tail |

2.131846782 |

|

| P(T<=t) two-tail |

0.04778593287 |

|

| t Critical two-tail |

2.776445098 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).