Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

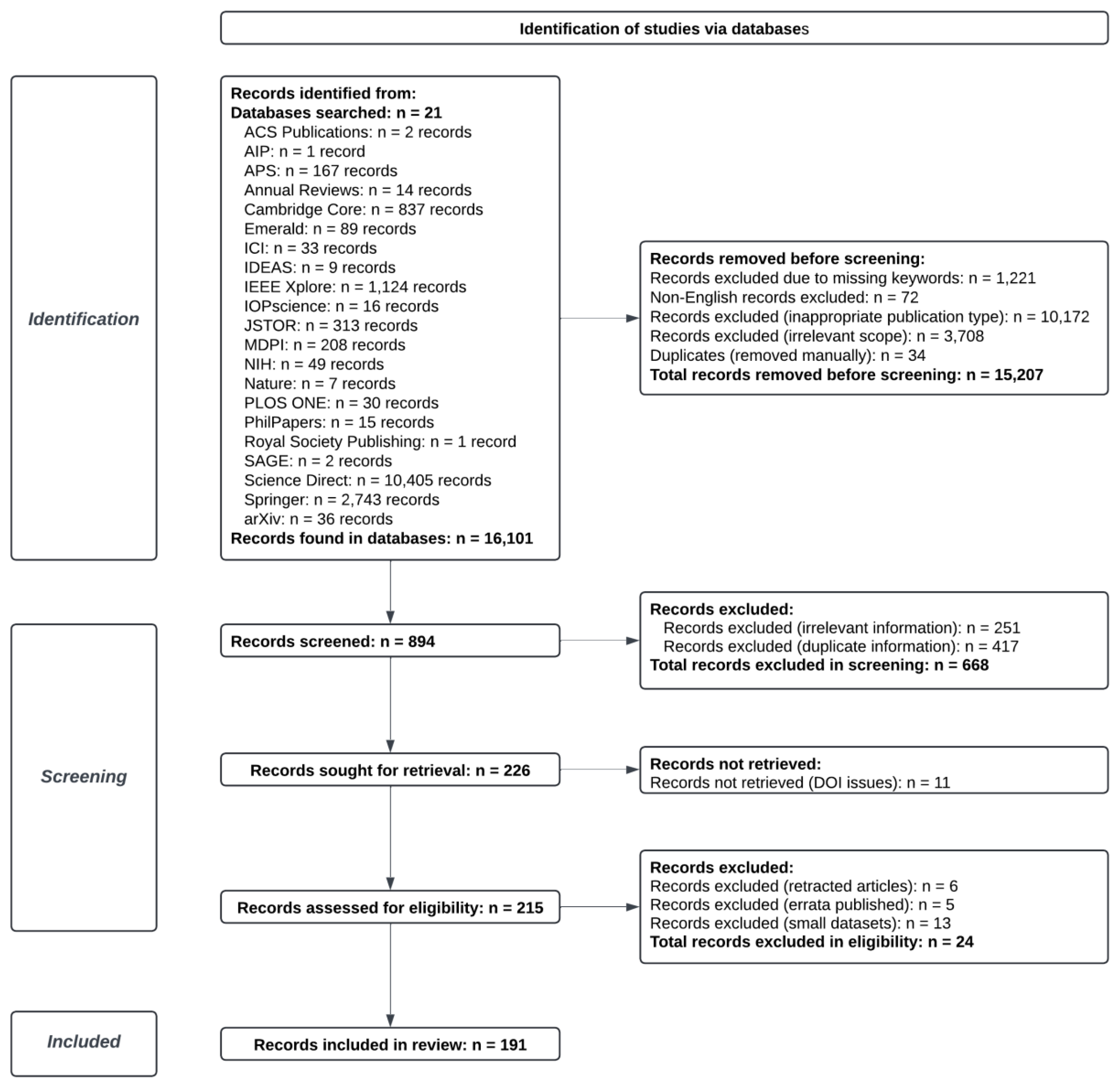

This systematic literature review introduces managerial infophysics, a novel framework and metaparadigm that integrates Business Process Management (BPM) principles with entropy-based metrics to address organizational uncertainty and enhance decision-making in complex environments. Employing the PRISMA methodology, the review spans research from 2018 to 2024, drawing on a comprehensive search across 21 databases, each selected for its focus on peer-reviewed content in BPM, econophysics, and informatics. The identification stage yielded 16,101 records, which were rigorously evaluated to ensure the inclusion of the most current and valid research on these topics. This review highlights the potential for entropy-based metrics to quantify process variability, offering a dynamic alternative to traditional KPIs. Through an interdisciplinary synthesis, managerial infophysics is proposed as a metaparadigm, presenting a unified approach to managing complexity and uncertainty within structured organizational processes. Findings suggest that entropy-enhanced BPM frameworks not only improve operational predictability and resource allocation but also extend BPM's applicability to sectors with high variability, such as healthcare and finance. Despite challenges in aligning BPM’s efficiency orientation with entropy’s probabilistic insights, the curated evidence supports this interdisciplinary framework's role in fostering organizational resilience and adaptability. This review establishes managerial infophysics as a promising conceptual model, inviting further empirical validation for broader application.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

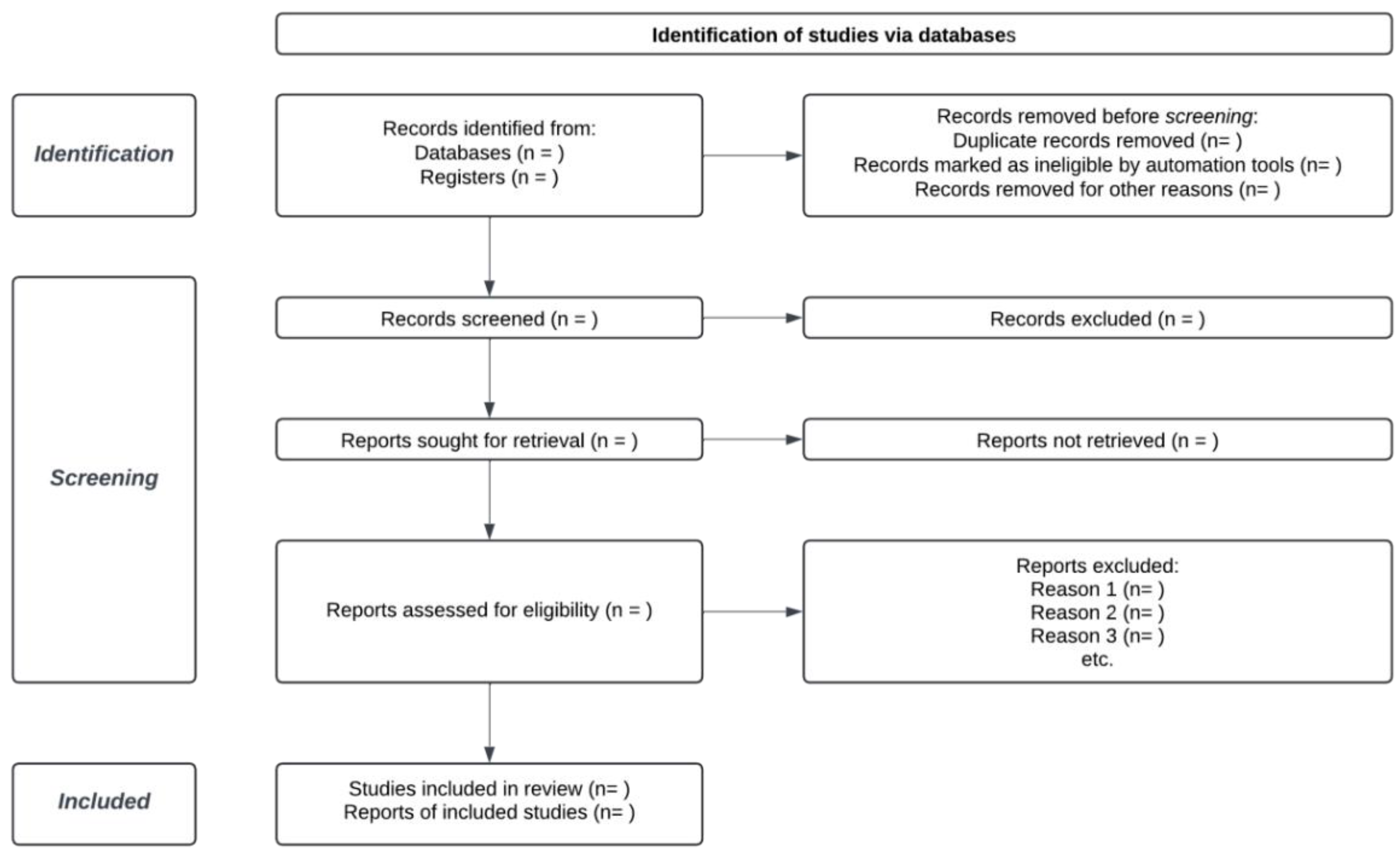

2.1. Research Design and PRISMA Framework

- If possible, the number of records found in each database or registration searched should be reported rather than the total;

- The number of excluded records (either manually or automatically) should be indicated.

- BPM: Focusing on optimization through modeling, quality standards, and data-driven decision-making;

- Econophysics and Financial Networks: Integrating complex systems theory and machine learning within economic and ethical contexts;

- Thermodynamics, Entropy, and Information Theory: Their applications in industrial settings, complex systems, and interdisciplinary scientific advancements.

2.2. Database Selection and Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Inclusion Criteria: Records were considered if they were peer-reviewed articles, review papers, or studies that directly addressed the research themes, such as BPM optimization, entropy in complex systems, or econophysics;

- Exclusion Criteria: Records were excluded if they did not contain relevant keywords, were non-English, were not suitable peer-reviewed types (e.g., conference abstracts or non-academic publications), were irrelevant to the core themes of the study, or were duplicates. Specifically, 1,221 records were excluded for missing relevant keywords when a narrowing down of the scope was necessary, 72 non-English records were removed to focus on English-language publications, 10,172 records were excluded for being inappropriate peer-reviewed types, and 3,708 records were excluded for irrelevance to the study’s main themes. Additionally, 34 duplicate records were removed manually.

2.4. Screening Stage

2.5. Eligibility Stage

2.6. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.7. Query Formulation

- Pre-Screening: Removing records not meeting all of the inclusion criteria;

- Detailed Screening: Removing records fοr meeting all the exclusion criteria for in-depth review.

2.8. Data Summary and PRISMA Flowchart Construction

2.9. Data Availability and Ethical Considerations

2.10. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. BPM Overview: Concepts and Evolution

3.1.1. BPM Ontology

3.1.2. BPM Life Cycle

3.1.3. Process Classifications

3.1.4. BPM Principles

- Value Creation: Organizations deploy various processes, from employee management to financial reporting, to create value for stakeholders [8]. Managing a collective of processes in a business setting should eventually promote the creation of value;

- Process Optimization: Effective process design methodologies with integrated maturity assessment procedures are essential; leveraging new information technologies is advisable [78]. Without well-defined process designs, regardless of mode of representation, a system will experience a propensity towards destabilization, thus, hindering overall performance [9];

- Process Standardization: Standardized processes enhance efficiency and consistency, yielding cost efficiency [74];

- Effective Management: Having established a fundamental process conceptualization in [2], it may be deduced that managing processes is not feasible without managing procedures. BPM, encompassing processes such as risk management and strategic planning, is an essential component of governance, similar to Project Management [79]. For a BPM system to merely possess effective design or standards is not enough; thorough execution management is essential for achieving continuous improvement [80]. Overseeing each updated BPM cycle is crucial for maintaining performance as operational efficiency may decline over time due to changing conditions.

3.1.5. BPM Paradigms

Quality Control

Epistemic Management

Information Technology

3.1.6. Business Process Modeling (BPMo)

3.1.7. Business Process Modeling Languages (BPMLs)

3.1.8. Process Metrics

3.2. Physics and Information in Social Sciences

3.2.1. Interdisciplinary Synergies

Big Data Statistics

Challenging Norms

Academic Momentum

Epistemological Convergences

3.2.2. Econophysics

3.2.3. Sociophysics

3.2.4. Network Science

3.2.5. Infophysics

3.2.6. Entropy Generalization

3.3. The Involutional Nexus of Entropy

3.3.1. Entropy's Emergence

3.3.2. Entropy Defined

3.3.3. Interdisciplinary Entropy

3.3.4. Foundations and Universality of Entropy

3.3.5. From Thermodynamics to Information

3.3.6. Information and Entropy

3.3.7. Information Entropy

- 1.

- Thermal Entropy:

- 2.

- Residual Entropy:

- 3.

- Information Entropy:

3.4. Epistemological Frontiers of Information Entropy in BPM

3.4.1. Foundational Empirical Implementations and Applications

3.4.2. PRISMA-Based Empirical Implementations and Applications

3.4.3. Analogical Inductions in BPM through Information Entropy

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Findings

4.1.1. Alignment with Previous Studies

4.1.2. Evaluation of Working Hypothesis

Hypothesis

Validation and Falsification Criteria

Emergent Research Questions and Expected Outcomes

4.2. Broader Context and Implications

4.2.1. Advancing BPM through Transdisciplinary Insights and Uncertainty Management

4.2.2. Integration Challenges, Limitations and Opportunities

Entropy-Based BPM

Entropy-Driven Management

Innovation-Focused BPM

Evolving Challenges and Adaptations in BPM

Methodological Divergence

Postulations for Novel BPM Development

- Tailor to context-specific factors and maintain alignment with organizational culture to ensure continuity and relevance;

- Identify key competencies and establish governance structures, metrics, and strategies that support effective and measurable outcomes;

- Involve individuals actively in process design, promoting stakeholder understanding and cognitive clarity to foster adoption;

- Ensure customization, simplicity, and cost-effective technological compatibility to meet goals and address potential implementation challenges;

- Provide ongoing feedback on system evolution, driven by dynamic changes to support adaptability and complexity management.

4.3. Future Research Directions

4.3.1. Enhancing BPM Predictive Models Through Entropy and Interdisciplinary Methods

4.3.2. Evolving BPM for Adaptive Strategy and Innovation Integration

4.3.2. Explorative BPM: Innovation and Entropy Modeling

4.4. Limitations

4.4.1. Scope, Complexity, and Generalizability Challenges

4.4.2. Rigidity, Scalability, and Industry-Specific Adaptations

4.4.3. Data and Methodological Constraints

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Appendix A

| Category | Terms |

|---|---|

| Business and Management Concepts | Business analytics, Actionable guidelines, Adoption of change, Agent-based models (ABM), Automated planning, Balanced Scorecard, BPM (Business Process Management), BPMN (Business Process Modeling Notation), Business excellence models, Business process modeling, Business process performance, Business process re-engineering, Capability maturity model integration, Change adoption, Change agents, Efficient business processes, Future business process management capabilities, Integrating process management, Process-aware information systems, Process models, Quality awards, Quality measurement, Quality requirements, Re-engineering, Reversibility, SIPOC, Systematic literature review, Unified BPM methodologies, Use cases, Value chain processes, Value network. |

| Corporate Excellence and Strategies | ASQ, Baldrige criteria, Corporate communication, Competitive advantage, Firm performance, Kaplan, Key performance indicators (KPIs), Management, Management theory, Market efficiency, Performance excellence, Porter models, Porter's value chain framework, Quality standards, Scientific management, TQM literature review. |

| Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Informatics | Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine learning (ML), Deep learning, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Neural networks, Simulation algorithms, Simulation-based estimations. |

| Informatics and Data | Bioinformatics, Medical informatics, Nursing informatics, Neuroinformatics, Urban informatics, Data analysis, Data science, Data uncertainty, Information systems, Future ERP, Software engineering language selection, Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). |

| Entropy, Thermodynamics, and Physics | Aleatoric, Barrow entropy, Basic concepts of classical thermodynamics, Bayesian inference, Boltzmann, Boltzmann entropy, Boltzmann equation, Carnot cycle, Clausius, Diffusion entropy, Disorder, Entanglement entropy, Entropic uncertainty relation, Entropy, Entropy economics, Entropy growth, Entropy maximization, Entropy measures, Entropy research, Equilibrium for a low-density gas, First law of thermodynamics, Finite-time thermodynamic process, Gibbs and Boltzmann entropy, Gibbs free energy, H-theorem, Irreversible entropy production, Landauer’s principle, Maximum entropy, Modified cosmology, Renyi entropy, Residual entropy, Second law of thermodynamics, Shannon entropy, Statistical entropy, Statistical mechanics, Thermodynamic entropy, Third law of thermodynamics, Transfer entropy, Von Neumann entropy. |

| Classical and Modern Physics | A mathematical theory of communication, Alan Turing legacy, Brillouin, Classical mechanics, Claude Shannon, Coalescence processes, Confined quantum systems, Conservation of information, Contributions of Shewhart and Deming, Crystallization, Diffusion rate, Einstein, Heisenberg, Hilbert space, Irreversibility, Ising model, Jaynes, Josiah Willard, Joule, Mayer, Quantum cosmology, Quantum mechanics, Rudolf Clausius, Symmetry, Thomson. |

| Statistical and Mathematical Modeling | Abductive theory, Algorithmic complexity, Bayesian inference, Complex methods, Complex networks, Complex systems, Complexity economics, Comparative research, Comparative study, Continuous stochastic volatility models, Decision models, Determinism, Dynamic controllability, Dynamical stability, Fat-tailed distributions, Fractional cumulative residual entropy, Geometry, Geostatistical models, Granger causality, Macroscopic behavior, Mathematical modeling, Multivariate probability density, Network analysis, Network structure, Probabilities, Probability, Stochastic processes, Temporal process modeling. |

| Information Theory and Entropy | Information dynamics, Information entropy system model, Information gain, Information governance, Information theory, Entropy measures, Shannon entropy, Negentropy. |

| Econophysics and Financial Systems | Economic complexity, Econophysics, Financial economics, Financial inclusion, Financial networks, Financial system networks, Physics of financial networks, Risk, Portfolio allocation. |

| Decision-Making and Management | Decision models, Decision support systems, DebtRank, Delphi study, MCDM (Multi-Criteria Decision Making), TOPSIS, PDCA. |

| Technological Innovations | Industry 3.5, 4.0, 5.0, Industrial revolution, Lean Philosophy, Circular value chain, Renewable energy resources, Digital transformation. |

| Process and System Improvements | BPMN (Business Process Modeling Notation), Event processing, Process-oriented systems, Re-engineering, iBPM (Intelligent BPM), Integration, Techniques. |

| Communication Models and Theories | A mathematical theory of communication, Communication, Interactive communication, Message transmission, Corporate communication. |

| Information and Knowledge | A priori knowledge, Application research, Application scenarios, Bibliometric analysis, Information theory, Information systems, Knowledge-based systems. |

| Philosophical and Ethical Concepts | Ethical challenges, Ethical concerns, Ethical interventions, Ethics in technology, Philosophical frameworks, Philosophy of economics, Philosophy of physics, Scientific pluralism, Scientific revolution, Scientific method, Scientific transformations. |

| Historical and Legacy Contributions | Alan Turing legacy, Contributions of Shewhart and Deming, Historical evolution, Historical interpretation, History of management, History of thermodynamics, Michael Porter, Robert Batterman, Rudolf Clausius, Eugene Stanley, Jaynes, Rosario Nunzio Mantegna, Taylorism. |

| Health Systems and Models | COVID-19 pandemic, Epidemiological models, Healthcare informatics, Biosystems, Biocomplexity. |

| Miscellaneous Concepts and Theories | Chapman–Jouguet condition, Constantino Tsallis, Field theories, Glasses, Historical overview, Micro-founded approach, Operating organized systems, Social influence dynamics, Sociophysics, Synchronization. |

| Criteria Details | Auxiliary Information |

|---|---|

| Missing Keywords | H-Theorem, ASQ, Alan Turing, BPM life cycle, Baldrige, Bibliometric analysis, Biocomplexity, Boltzmann entropy, Coalescence processes, Continuum informatics, DMAIC, Deming, Deming cycle, Deming prize, EFQM, Eco-informatics, Embedding, Empirical study, Enterprise applications, Financial, Financial networks, Granger, Group transfer entropy, Guidelines, ISO, Industrial revolutions, Informatics, Information dynamics, Japan, Juran, M. Porter, Nursing informatics, Ohno, PDCA, Philosophical, Process, Review, Shannon, Shingo, Survey, Systematic literature review, Ten principles of good BPM, Understandable BPMN, Use cases, Automated planning, Business analytics, Dynamic controllability, Modeling. |

| Appropriate Publication Type | Articles, Articles Compiled into Handbooks or Book Chapters, Entry, Journal Articles, Journals, Research Articles, Review Articles. |

| Relevant Scope | Applied Software Computing, Artificial Intelligence, Author: Schinckus, Big Data, Business, Chemistry and Earth Sciences, Computer Science, Cosmology, Decision Sciences, Earth Sciences, Econometrics and Finance, Economics, Engineering, History and Philosophical Foundations of Physics, Information Technology, Management, Managerial Accounting, Mathematics, Networks, Philosophy, Philosophy of Science, Physics, Physics and Astronomy, Quantitative Finance, Research and Analysis Methods, Software Engineering, Statistical physics and dynamical systems, Statistics, Statistics for Engineering, Thermodynamics |

| DB | Query No. | ID Terms | Records | Records Removed (Pre-Screening) | Exclusion Criteria (AND) | Inclusion Criteria (AND) | Records Found | Chosen for Screening |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Science Direct | 1 | business analytics, business process performance bper, resource-based view, firm performance | 3 | 2 | Record did not include the keywords: business analytics | 1 | 1 | |

| Science Direct | 2a | industrial internet of things, IoT, integrating process management, system, architecture, event processing, use cases, integration, application scenarios, BPM | 20 | 4 | Research Articles | 16 | 1 | |

| 2b | 15 | Record did not include the keywords: use cases | 1 | |||||

| Science Direct | 3a | process models, efficient business processes, synchronizations, automated planning, control flow patterns | 1.465 | 935 | Computer Science | 530 | 1 | |

| 3b | 242 | Research Articles | 288 | |||||

| 3c | 287 | Record did not include the keywords: automated planning | 1 | |||||

| Science Direct | 4 | time aware BPMN, temporal verification, BPMN processes, dynamic controllability, temporal process modelling, temporal constraints | 70 | 69 | Software Publication | 1 | 1 | |

| Science Direct | 5 | Porter, circular value chain, value chain processes, Porter's value chain framework, competitive advantage | 553 | 491 | Review Articles | 62 | 62 | |

| Science Direct | 6 | project management, enterprise applications | 17 | 8 | Record did not include the keywords: enterprise applications | 9 | 9 | |

| Science Direct | 7 | Juran, ASQ | 22 | 20 | Review Articles | 2 | 2 | |

| Science Direct | 8a | bpm definition | 5.911 | 1.658 | Research Articles | 4.253 | 168 | |

| 8b | 3.644 | Review Articles | 609 | |||||

| 8c | 441 | Business, Management and Accounting | 168 | |||||

| Science Direct | 9a | PDCA, Deming cycle | 192 | 66 | Non-English | 126 | 4 | |

| 9b | 18 | Research Articles | 108 | |||||

| 9c | 85 | Review Articles | 23 | |||||

| 9d | 19 | Record did not include the keywords: PDCA, Deming cycle | 4 | |||||

| Science Direct | 10a | SIPOC, DMAIC Methodology | 69 | 8 | Non-English | 52 | 3 | |

| 10b | 4 | Research Articles | 47 | |||||

| 10c | 0 | Review Articles | 5 | |||||

| 10d | 54 | Record did not include the keywords: DMAIC | 3 | |||||

| Science Direct | 11a | quality standards, EFQM, ISO | 99 | 46 | Research Articles | 53 | 1 | |

| 11b | 35 | Review Articles | 11 | |||||

| 11c | 17 | Record did not include the keywords: EFQM, ISO | 1 | |||||

| Science Direct | 12a | bpm life cycle approach, process life cycle, design, implementation, integration | 719 | 337 | Research Articles | 382 | 2 | |

| 12b | 246 | Review Articles | 136 | |||||

| 12c | 134 | Record did not include the keywords: bpm life cycle | 2 | |||||

| IEEE Xplore | 13a | processing real-time big data stream ,review | 963 | 776 | Journals | 187 | 1 | |

| 13b | 94 | Big Data | 93 | |||||

| 13c | 92 | Record did not include the keywords: review | 1 | |||||

| IEEE Xplore | 14 | PDCA, Deming cycle | 11 | 9 | Journals | 2 | 2 | |

| IEEE Xplore | 15 | peer to peer, person to application, and application to application, process aware information systems | 137 | 118 | Journals | 19 | 19 | |

| IEEE Xplore | 16 | capability maturity model integration, systematic literature review | 7 | 6 | Record did not include the keywords: systematic literature review | 1 | 1 | |

| IEEE Xplore | 17 | Event-Driven Process Chain, systematic literature review | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Springer | 18 | future business process management capabilities, BPM frameworks, traditional information systems, Delphi study | 41 | 31 | Research Articles | 6 | 10 | |

| Book Chapters | 4 | |||||||

| Springer | 19 | systematic review, unified, bpm methodologies | 17 | 15 | Engineering | 2 | 2 | |

| Springer | 20a | history of ASQ | 528 | 4 | Non-English | 524 | 2 | |

| 20b | 479 | Business, Management | 45 | |||||

| 20c | 43 | Record did not include the keywords: Juran, ASQ, Deming | 2 | |||||

| Springer | 21 | Lean Philosophy, Japan, Deming, Shingo, Ohno | 18 | 17 | Record did not include the keywords: Japan, Deming, Shingo, Ohno | 1 | 1 | |

| Springer | 22 | Michael Porter, management theory, porter models, value chain, Japanese | 170 | 167 | Review Articles | 3 | 3 | |

| Springer | 23a | value chain, value network, Systematic literature review, Porter, evolution, intangible assets | 80 | 57 | Articles | 23 | 1 | |

| 23b | 10 | Business, Management | 13 | |||||

| 23c | 12 | Record did not cite: M. Porter | 1 | |||||

| Springer | 24 | future ERP, big data, iBPM, process oriented | 3 | 2 | Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| Springer | 25 | impact of Alan Turing, formal methods, Andrew Hodges, Alan Turing legacy | 3 | 2 | Record did not include the keywords: Alan Turing | 1 | 1 | |

| Springer | 26a | business process modeling, BPM and software engineering language selection, decision models, decision making, decision support systems, case study research, language selection problem, BPMN, EPC | 12 | 3 | Articles | 9 | 5 | |

| 26b | 4 | Computer Science | 5 | |||||

| Cambridge Core | 27a | Lean Philosophy, Japan, Deming, Shingo, Ohno | 837 | 744 | Book Chapters | 93 | 31 | |

| 27b | 62 | Management | 31 | |||||

| NIH | 28 | comprehensive, Balanced Scorecard, Kaplan | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| NIH | 29 | re-engineering, Hammer, Champy, IT | 5 | 3 | Medical | 2 | 2 | |

| NIH | 30 | business information-entropy correlation | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9 | ||

| NIH | 31 | contributions of Shewhart and Deming, TQM literature review | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| NIH | 32 | Taylor contributions, Taylorism, scientific management, efficiency, history of management | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | ||

| MDPI | 33a | process scheduling, dynamic controllability | 100 | 4 | Articles | 96 | 1 | |

| 33b | 95 | Record did not include the keywords: dynamic cotrollability | 1 | |||||

| MDPI | 34a | business process re-engineering, literature review | 4 | 2 | Articles | 2 | 1 | |

| 34b | 1 | IT | 1 | |||||

| Emerald | 35a | ten principles of good BPM, vom Brocke | 59 | 1 | Articles | 58 | 1 | |

| 35b | 57 | Record did not include the keywords: ten principles of good BPM | 1 | |||||

| Emerald | 36 | business excellence models, Baldrige criteria, performance excellence, EFQM, Deming prize, quality awards, comparative study, Europe, Japan, compare, Crosby | 3 | 2 | Record did not include the keywords: Baldrige, EFQM, Deming prize, Japan | 1 | 1 | |

| Emerald | 37 | BPMN, communication, cognitive, process modeling, corporate communication, visualization | 10 | 7 | Record did not include the keywords: process, modeling | 3 | 3 | |

| Science Direct | 38a | understandable BPMN, guidelines, Business Process Modelling Notation 2.0, object management group, BPMN models | 63 | 14 | Research Articles | 49 | 1 | |

| 38b | 40 | Engineering | 9 | |||||

| 38c | 8 | Record did not include the keywords: understandable BPMN, guidelines | 1 | |||||

| Springer | 39a | business process modeling language selection, BPM languages, decision models and multi-criteria decision-making, decision support systems, Software Engineering, BPMN | 26 | 12 | Articles | 14 | 5 | |

| 39b | 6 | Computer Science | 8 | |||||

| 39c | 3 | Software Engineering | 5 | |||||

| Emerald | 40 | BPM success factors, BPM pitfalls, integrated frameworks, actionable guidelines | 4 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Science Direct | 41a | KPIs management, KPI taxonomy, key performance indicators management, taxonomy development, qualitative attributes | 147 | 126 | Review Articles | 21 | 6 | |

| 41b | 15 | Decision Sciences | 6 | |||||

| MDPI | 42 | Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing, business process management | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Science Direct | 43 | quality measurement, quality requirements, quality requirements management, quality-related indicators, non-functional requirements, quality indicators metrics, systematic mapping, ARSD | 2 | 1 | Research Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| MDPI | 44 | organizational changes, key performance indicators, measures, methods, and techniques | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Science Direct | 45a | uncertainty quantification, review, ensembles, evidence lower bound, aleatoric, data uncertainty, deep learning, artificial intelligence, applications, Bayesian, research gaps, machine learning | 21 | 15 | Review Articles | 6 | 4 | |

| 45b | 2 | Computer Science | 4 | |||||

| MDPI | 46 | algorithmic complexity, Shannon entropy, decomposition | 4 | 3 | Review Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| Science Direct | 47 | Shannon entropy, dynamical stability, diffusion rate, physical instabilities, dynamical indicator, chaos indicators | 15 | 10 | Research Articles | 5 | 5 | |

| Science Direct | 48 | econophysics, ising model | 1 | 0 | Author: Schinckus | 1 | 1 | |

| Springer | 49 | econophysics, bibliometric analysis, bibliometrics | 4 | 2 | Articles | 2 | 2 | |

| Science Direct | 50a | financial economics, role of econophysics | 4 | 0 | Author: Schinckus | 4 | 3 | |

| 50b | 1 | Research Articles | 3 | |||||

| Science Direct | 51 | stock markets, micro-founded approach, simulation-based estimations, herding behavior, spurious herding, agents-based models | 5 | 2 | Research Articles | 3 | 3 | |

| Science Direct | 52 | numerical simulations, coarse-grained bonded particle model, CG-BPM | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Science Direct | 53 | macro-theories, micro-theories, macro-level phenomena, Robert Batterman, philosophy of physics for economics | 2 | 1 | Research Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| arXiv | 54 | philosophy of physics, indeterminism, determinism, classical physics | 7 | 0 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Emerald | 55 | ABM, economic complexity, econophysics, perfectly rational ABM | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| JSTOR | 56a | interdisciplinary synergies, comparative research, interdisciplinary research | 313 | 131 | Journal Articles | 182 | 180 | |

| 56b | 2 | Non-English | 180 | |||||

| Science Direct | 57a | the role of econophysics, financial economics, physics, mutual influence, | 23 | 6 | Research Articles | 17 | 12 | |

| 57b | 5 | Economics, Econometrics and Finance | 12 | |||||

| Springer | 58 | Benoit Mandelbrot, fractal geometry, nature, Physics Wolf Prize, general topology | 9 | 8 | Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| PLOS ONE | 59 | interdisciplinarity in physics, PACS | 30 | 15 | Research and Analysis Methods | 15 | 15 | |

| MDPI | 60 | comprehensive survey, continuous stochastic volatility models | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 61 | big data, finance, evidence challenges, machine learning, neural network, big data-based evidence, literature review, vector autoregression framework | 52 | 44 | Review Articles | 8 | 8 | |

| Science Direct | 62 | Lomax model, Pareto Type-II, arc-sine exponentiation Lomax model | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 63 | big data, complex phenomena, networks, econophysics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Springer | 64a | institutionalization, interdisciplinarity, research studies | 294 | 273 | Philosophy | 21 | 10 | |

| 64b | 11 | Philosophy of Science | 10 | |||||

| Springer | 65 | econophysics dynamics, bibliometric analysis, network analysis | 10 | 4 | Articles | 6 | 6 | |

| arXiv | 66 | physics of financial networks, complex networks, statistical physics, DebtRank | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| MDPI | 67 | exponentially decaying coefficients, multivariate HAR model in stock markets | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 68 | heterogeneous agent-based two-state sociophysics model, financial markets simulation | 8 | 3 | Research Articles | 5 | 5 | |

| MDPI | 69 | systematic review, socio-economic development, financial inclusion, | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Science Direct | 70 | change adoption, change agents, organizational networks, adoption of change, change management scenaria | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Science Direct | 71 | econophysics and sociophysics, review, Eugene Stanley, Rosario Nunzio Mantegna | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 72 | Tsallis entropy, Landau–Ginzburg equation, complex systems | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 73 | sociophysics, complex networks | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| MDPI | 74 | entropy economics, econophysics, complexity economics | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| MDPI | 75 | big data, ethical concerns, social sciences | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Science Direct | 76a | non-Gaussian distributions, financial returns, simulation, fat-tailed distributions, leptokurtic distribution | 88 | 5 | Research Articles | 83 | 8 | |

| 76b | 54 | Mathematics | 29 | |||||

| 76c | 21 | Record did not include the keywords: financial | 8 | |||||

| MDPI | 77 | depolarization, sociophysics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 78a | biocomplexity, complexity, complex systems, complexity paradigm, philosophy | 7 | 4 | Review Articles | 3 | 1 | |

| 78b | 2 | Record did not include the keywords: biocomplexity | 1 | |||||

| IOPscience | 79a | network entropy, statistical physics, heterogeneity, modularity, network structure, information theory, information dynamics, complexity, quantum networks, machine learning | 9 | 5 | Articles | 4 | 1 | |

| 79b | 3 | Record did not include the keywords: information dynamics | 1 | |||||

| Nature | 80a | physics of financial networks, financial system networks, time-dependent, maximum entropy, statistical mechanics | 7 | 4 | Review Articles | 3 | 1 | |

| 80b | 2 | Record did not include the keywords: financial networks | 1 | |||||

| Science Direct | 81a | network science, taxonomies, applications, complex systems, network embedding techniques, network evolvement, granularity, heterogeneity, static, dynamic | 146 | 96 | Review Articles | 50 | 1 | |

| 81b | 49 | Record did not include the keywords: embedding | 1 | |||||

| Springer | 82a | big data, data science, statistics, time series, multivariate data, machine learning, sparse model selection | 559 | 131 | Articles | 428 | 4 | |

| 82b | 424 | Artificial Intelligence, Statistics | 4 | |||||

| APS | 83a | statistical physics, complex information dynamics, emergent phenomena, information dynamics, von Neumann entropy | 136 | 21 | Articles | 115 | 8 | |

| 83b | 107 | Networks | 8 | |||||

| Science Direct | 84a | maximum entropy networks, coalescence processes, complex networks, von Neumann entropy, entropy of network states | 22 | 18 | Research Articles | 4 | 1 | |

| 84b | 3 | Record did not include the keywords: coalescence processes | 1 | |||||

| Royal Society Publishing | 85 | cointegration modelling, Granger causality network modelling, financial equilibrium, financial diffusion paths | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 86a | computational intelligence, time-series studies, financial time series forecasting, RNN based DL models, CNN, LSTM, RNN, deep learning, systematic literature review | 159 | 104 | Research Articles | 55 | 3 | |

| 86b | 34 | Computer Science | 21 | |||||

| 86c | 18 | Applied Software Computing | 3 | |||||

| MDPI | 87 | multimodal approach, economic growth, multiplex network analysis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 88 | macroscopic complexity, microscopic modelling, econophysics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| arXiv | 89a | financial networks, systemic risk, systematic risk, taxonomy, portfolios, correlated portfolios, review, survey | 12 | 0 | Quantitative Finance | 12 | 1 | |

| 89b | 11 | Record did not include the keywords: survey | 1 | |||||

| NIH | 90 | nursing informatics, survey, education, open-ended questionnaires | 17 | 14 | Record did not include the keywords: nursing informatics | 3 | 3 | |

| IEEE Xplore | 91 | AI, medical informatics, current challenges, integrative analytics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 92 | informatics literature, MPV studies, medical informatics, review, medical practice variation | 20 | 19 | Review Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| ACS Publications | 93 | informatics, chemistry, biology, biomedical sciences, bioinformatics discipline, pharmacoinformatics, neuroinformatics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 94 | mathematical modeling, bioinformatics, symmetric distance matrix | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Emerald | 95 | urban informatics, citizen-ability | 8 | 6 | Record did not include the keywords: informatics | 2 | 2 | |

| Science Direct | 96a | informatics, ethics, artificial intelligence, super intelligence, ethical challenges, ethical interventions, ethics in technology, | 66 | 55 | Review Articles | 11 | 5 | |

| 96b | 6 | Computer Science | 5 | |||||

| Emerald | 97 | monistic diversity, continuum informatics, informatics, ethics, information governanc | 2 | 1 | Record did not include the keywords: continuum informatics | 1 | 1 | |

| Emerald | 98 | eco-informatics, ecological data management | 2 | 1 | Record did not include the keywords: eco-informatics | 1 | 1 | |

| MDPI | 99 | social infuence dynamics, sociophysics models | 14 | 13 | Review Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| MDPI | 100 | bibliometric analysis, Granger causality studies | 3 | 2 | Record did not include the keywords: bibliometric analysis | 1 | 1 | |

| Science Direct | 101 | P2P lending, profile modelling methods, random walk, financing platforms | 7 | 1 | Research Articles | 6 | 6 | |

| Science Direct | 102 | Granger Geweke causality, interpersonal physical interactions, information, information exchange, information flow | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Annual Reviews | 103a | Granger causality, review, mixed-frequency time series, multivariate time series | 14 | 4 | Articles | 10 | 1 | |

| 103b | 9 | Record did not include the keywords: Granger | 1 | |||||

| MDPI | 104 | Reissner–Nordström, entropy, black hole, Roegenian economics | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Science Direct | 105a | Granger-causality tests, group transfer entropy, cryptocurrencies, nonlinear, vector autoregressions | 6 | 1 | Research Articles | 5 | 1 | |

| 105b | 4 | Record did not include the keywords: group transfer entropy | 1 | |||||

| Springer | 106 | financial time series forecasting, Boltzmann entropy, neural networks, regressive models, agent-based model | 3 | 2 | Record did not include the keywords: Boltzmann entropy | 1 | 1 | |

| IEEE Xplore | 107 | effective transfer entropy, machine learning techniques, stock markets | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 108 | transfer entropy, option implied volatility, multi variate GARCH forecast, financial assets, portfolio allocation, implied volatility, realized variance, | 6 | 4 | Research Articles | 2 | 2 | |

| Science Direct | 109 | transfer entropy, diffusion entropy, normal transfer entropy, nonlinear correlations, short time sequences, stock markets, minimum spanning tree, complex networks | 39 | 36 | Research Articles | 3 | 3 | |

| IEEE Xplore | 110 | stock market forecasting, deep learning, systematic review, complex time series | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 111 | history of thermodynamics, Carnot, Clapeyron, Thomson | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 112 | Clausius, Second Law of Thermodynamics, equivalence of the transformation of heat to work | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 113a | overview of all industrial revolutions, social impacts, historical overview, industry 3.5, 4.0, 5.0, scientific transformations, automation theories | 50 | 39 | Research Articles | 11 | 1 | |

| 113b | 10 | Record did not include the keywords: industrial revolutions | 1 | |||||

| IDEAS | 114 | scientific revolution, industrial revolution, Habbakuk thesis | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Springer | 115 | energy concept, Mayer, Joule, conservation principle, Thomson, Young, Davy | 13 | 10 | Articles | 3 | 3 | |

| ICI | 116 | Interdisciplinary ApproachesHistorical InterpretationPhilosophical Frameworks | 33 | 31 | Record did not include the keywords: philosophical | 2 | 2 | |

| MDPI | 117 | thermodynamics, information, entropy, Industrial Revolution | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Springer | 118a | first law of thermodynamics, basic concepts of classical thermodynamics, energy transfer quantities, reversibility and irreversibility | 45 | 14 | Chapters | 31 | 4 | |

| 118b | 27 | Thermodynamics, Physics, Statistical physics and dynamical systems | 4 | |||||

| MDPI | 119 | nonequilibrium temperature, irreversibility, Gouy–Stodola theorem | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| SAGE | 120 | entropy measures, , uncertainty quantification, stochastic processes, review, probabilistic nature, disorder, process, Shannon entropy, Renyi entropy, Tsallis entropy, | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Springer | 121a | entropy maximization, entropy, self-assembly, colloidal systems, colloidal particles, crystals | 21 | 2 | Articles | 19 | 1 | |

| 121b | 18 | Physics | 1 | |||||

| MDPI | 122 | entropy universe, information theory | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 123 | crystallization, entropy, Kauzmann paradox | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| MDPI | 124 | entropy research, bibliometric | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 125 | Carnot cycle, reversibility, entropy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| arXiv | 126 | Eisenhart lift, field theories | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| arXiv | 127 | irreversible entropy production, finite-time thermodynamic process | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 128 | black hole entropy, complex systems | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| MDPI | 129 | entropy, Constantino Tsallis | 17 | 16 | Entry | 1 | 1 | |

| arXiv | 130 | Barrow entropy, modified cosmology | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| MDPI | 131 | statistical entropy, biosystems, Schrödinger, negentropy | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 132 | maximum entropy model, geoscience data, information systems | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 133 | social entropy, normative networks | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 134 | partitioning entropy, chemical potentials | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 135 | information entropy in chemistry | 8 | 7 | Review Articles | 1 | 1 | |

| Springer | 136a | entropy, information, geostatistical models, multivariate probability density, simulation algorithms | 53 | 38 | Earth Sciences, Statistics for engineering, physics, computer science, chemistry and earth sciences | 15 | 13 | |

| 136b | 2 | Articles | 13 | |||||

| MDPI | 137 | forecasting, entropy, machine-learning | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| IEEE Xplore | 138 | information-based society, information society, sustainable business development | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| IEEE Xplore | 139 | evaluation method, cost-effectiveness, data, cost management, Entropy Weight Method | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 140 | hierarchical information entropy, information entropy system model | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ACS Publications | 141 | history of thermodynamics, Rudolf Clausius, Josiah Willard | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Springer | 142a | Boltzmann equation, H-Theorem, equilibrium for a low-density gas, entropy | 719 | 306 | Chapters | 413 | 1 | |

| 142b | 185 | Physics | 228 | |||||

| 142c | 206 | History and philosophical foundations of physics | 22 | |||||

| 142d | 21 | Record did not include the keywords: H-Theorem | 1 | |||||

| Springer | 143a | COVID-19 pandemic, scientific pluralism, epidemiological models | 52 | 43 | Philosophy of Science | 9 | 7 | |

| 143b | 2 | Articles | 7 | |||||

| PhilPapers | 144 | exploratory models, exploratory modeling, science | 15 | 0 | 15 | 15 | ||

| arXiv | 145 | Gibbs and Boltzmann entropy, classical mechanics, quantum mechanics | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| IOPscience | 146 | entropy in classical physics, entropy in quantum physics, mathematical definition, historical evolution, Neumann, entanglement entropy, Hilbert space, complexity, Heisenberg, chaotic systems | 7 | 5 | Articles | 2 | 2 | |

| MDPI | 147 | statistical mechanics, discrete multicomponent fragmentation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| IDEAS | 148 | entropy, generalized maximum entropy | 6 | 0 | 6 | 6 | ||

| MDPI | 149 | entropy, information, probabilities, Bayesian inference | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| arXiv | 150 | Bayesian interpretations, quantum mechanics theory | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| arXiv | 151 | macroscopic behavior, microscopic behavior | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Science Direct | 152a | Shannon entropy, entropic uncertainty relation, confined systems, information theory, confined quantum systems | 70 | 48 | Research Articles | 22 | 19 | |

| 152b | 3 | Physics and Astronomy | 19 | |||||

| Science Direct | 153 | renewable energy resources, RES, Shannon entropy, MCDM, EDAS | 17 | 16 | Record did not include the keywords: Shannon | 1 | 1 | |

| NIH | 154 | Shannon entropy, quantifying uncertainty, quantifying risk | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Springer | 155 | IT, Shannon’s entropy and information, Claude Shannon, entropy power inequality | 28 | 21 | Physics | 7 | 7 | |

| Science Direct | 156 | interactive communication, unknown noise rate, prior knowledge, a priori knowledge, Haeupler | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 157 | mechanical Maxwell’s Demon | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| MDPI | 158 | Boltzmann, Zipf, Shannon, Jaynes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 159 | entropy, Carnot cycle, information theory | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 160 | Maxwell’s demon, information theory, market efficiency, Brillouin | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 161 | entropy, information, symmetry, Landauer principle | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Springer | 162 | physical foundations, Landauer’s principle, loss of information, thermodynamic entropy, transfer of entropy, correlated information | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Springer | 163 | entropy, information, probability, statistical mechanics, Landauer-Bennett, Maxwell’s demon | 25 | 18 | Philosophy | 7 | 7 | |

| MDPI | 164 | conservation of information, entropy, misunderstandings | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| AIP | 165 | entropy growth, information gain, operating organized systems, negentropy, Boltzmann | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| NIH | 166 | evolution of biomolecular communication, message transmission, bioinformatic | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| APS | 167 | boundary conditions, closed cosmologies, Gibbons-Hawking-York, geometry, covariant boundary action, quantum cosmology, information | 31 | 23 | Cosmology | 8 | 8 | |

| arXiv | 168 | bouncing cosmology, inhomogeneity problems | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| arXiv | 169 | similarity theory, Shannon entropy, big data | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 170 | Boltzmann, Gibbs, Shannon, nonadditive entropies | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 171 | fractional cumulative residual entropy, CRE | 21 | 14 | Research Articles | 7 | 7 | |

| arXiv | 172 | residual entropy, glasses, third law | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 173 | entropy, perfect crystals, imperfect crystals, enthalpy, third law, Gibbs free energy, Boltzmann equation, thermodynamic, Boltzmann equation, isothermal | 29 | 26 | Research Articles | 3 | 3 | |

| arXiv | 174 | thermodynamic criterions, self-assembly processes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| MDPI | 175 | information theory, applications, A Mathematical Theory of Communication | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| arXiv | 176 | application research, TOPSIS, entropy weighting method | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Science Direct | 177a | COVID-19 pandemic, information entropy, Shannon, empirical study, management | 161 | 31 | Research Articles | 130 | 2 | |

| 177b | 128 | Record did not include the keywords: empirical study | 2 | |||||

| NIH | 178 | existing knowledge, inductive reasoning | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Springer | 179 | scientific method, abductive theory, complex methods, empirical phenomena, explanatory theories, data analysis, analogical modelling, competing explanations | 6 | 2 | Philosophy | 4 | 4 |

| Details | Auxiliary Information |

|---|---|

| Databases and Searches per Database | ACS Publications: 2 times, AIP: 1 time, APS: 2 times, Annual Reviews: 1 time, Cambridge Core: 1 time, Emerald: 8 times, ICI: 1 time, IDEAS: 2 times, IEEE Xplore: 10 times, IOPscience: 2 times, JSTOR: 1 time, MDPI: 47 times, NIH: 9 times, Nature: 1 time, PLOS ONE: 1 time, PhilPapers: 1 time, Royal Society Publishing: 1 time, SAGE: 1 time, Science Direct: 47 times, Springer: 26 times, arXiv: 14 times. |

| Databases and Records per Database | ACS Publications: 2 records, AIP: 1 record, APS: 167 records, Annual Reviews: 14 records, Cambridge Core: 837 records, Emerald: 89 records, ICI: 33 records, IDEAS: 9 records, IEEE Xplore: 1124 records, IOPscience: 16 records, JSTOR: 313 records, MDPI: 208 records, NIH: 49 records, Nature: 7 records, PLOS ONE: 30 records, PhilPapers: 15 records, Royal Society Publishing: 1 record, SAGE: 2 records, Science Direct: 10405 records, Springer: 2743 records, arXiv: 36 records |

| 1 | Additional information and editable extensions, such as flowcharts and checklists, may be retrieved at the official PRISMA [60] website: https://www.prisma-statement.org/. |

| 2 | Thus, query number 2 becomes 2a and the sub-query becomes 2b (1 primary query and 1 sub-query totaling to 2 queries). |

| 3 | The European Foundation for Quality Management is a nonprofit membership organization established in nineteen eighty-nine. In its initial phase, the policy document for organizational excellence garnered the support of sixty-seven CEOs and presidents from prominent European companies, reaffirming their commitment to upholding EFQM's missions and values. EFQM partners with an extensive network of over fifty thousand enterprises across Europe and beyond, encompassing notable organizations such as BMW, Siemens, and Huawei [62]. |

| 4 | The International Organization for Standardization is a globally recognized establishment responsible for the development of international standards, comprising delegates appointed by the national standards organizations, affiliated with members all over the world [63]. |

| 5 | The Architecture of Integrated Information Systems (ARIS) platform is a BPM toolset, allowing organizations to model, analyze, and optimize their processes effectively [64]. |

| 6 | The Systems, Applications, and Products in Data Processing (SAP) reference model is a collection of predefined processes and best practices designed to help organizations implement and manage their enterprise resource planning systems efficiently [65]. |

| 7 | The Object Management Group (OMG) is an international, open membership, non-profit technology standards group that formed to develop standards for a variety of industries [66]. |

| 8 | In 1948, C. Shannon published "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" [67] which revolutionized information theory. Shannon's development of the concept of entropy in information theory led to a dramatic shift in the comprehension and measurement of information and uncertainty. |

References

- Nousias, N., Tsakalidis, G., & Vergidis, K. Not yet another BPM lifecycle: A synthesis of existing approaches using BPMN. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2024, 171, 107471. [CrossRef]

- Nandakumar, N.; Saleeshya, P.G.; Harikumar, P. Bottleneck Identification And Process Improvement By Lean Six Sigma DMAIC Methodology. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Materials and Manufacturing Applications, IConAMMA 2018, 16th-18th August 2018, India. [CrossRef]

- Ben Haj Ayech, H., Ayachi Ghannouchi, S., & Ammar El Hadj Amor, E. Extension of the BPM lifecycle to promote the maintainability of BPMN models. Proc. Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 852-860. [CrossRef]

- Tomaskova, H., Babaee Tirkolaee, E., & Raut, R.D. Business process optimization for trauma planning. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 113959. [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Soto, K.C., Blanco-Fernández, J., Miranda-Ackerman, M.A., Solís-Quinteros, M.M., Realyvásquez-Vargas, A., & García-Alcaraz, J.L. A Plan-Do-Check-Act Based Process Improvement Intervention for Quality Improvement. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 132779-132790. [CrossRef]

- Kerpedzhiev, G.D.; König, U.M.; Röglinger, M. An Exploration into Future Business Process Management Capabilities in View of Digitalization. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2021 63, 83-96. [CrossRef]

- Badakhshan, P., Scholta, H., Schmiedel, T., vom Brocke, J. A measurement instrument for the “ten principles of good BPM”. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 1762–1790. [CrossRef]

- Brinch, M.; Gunasekaran, A.; Fosso Wamba, S. Firm-level capabilities towards big data value creation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 539-548. [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; González-Zamar, M.D.; Squillante, M. Examining the Research on Business Information-Entropy Correlation in the Accounting Process of Organizations. Entropy 2021, 23, 1493. [CrossRef]

- Ibidapo, T. A. Dynamics of Quality. In: From Industry 4.0 to Quality 4.0. Management for Professionals. 1st ed.; Springer, Cham: Switzerland, 2022; pp. 433-471. [CrossRef]

- Grisold, T., Groß, S., Stelzl, K., vom Brocke, J., Mendling, J., Röglinger, M., Rosemann, M. The Five Diamond Method for Explorative Business Process Management. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2022, 64, 149-166. [CrossRef]

- Pufahl, L., Zerbato, F., Weber, B., Weber, I. BPMN in healthcare: Challenges and best practices, Inf. Syst. 2022, 107, 102013. [CrossRef]

- Aydiner, A. S., Tatoglu, E., Bayraktar, E., Zaim, S., Delen, D. Business analytics and firm performance: The mediating role of business process performance, J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 228-237. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J. P. The Impact of Alan Turing: Formal Methods and Beyond. In Engineering Trustworthy Software Systems. SETSS 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Bowen, J., Liu, Z., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11430, pp. 202-235. [CrossRef]

- Seiger, R.; Malburg, L.; Weber, B.; Bergmann, R. Integrating process management and event processing in smart factories: A systems architecture and use cases. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 63, 575-592. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, E.; Pérez, B.; Rubio, Á. L.; Zapata, M. A. A taxonomy for key performance indicators management. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2019, 64, 24-40. [CrossRef]

- Abdar, M.; Pourpanah, F.; Hussain, S.; Rezazadegan, D. A Review of Uncertainty Quantification in Deep Learning: Techniques, Applications and Challenges. Inf. Fusion 2021, 76, 243-297. [CrossRef]

- Zenil, H.; Hernández-Orozco, S.; Kiani, N.A.; Soler-Toscano, F.; Rueda-Toicen, A.; Tegnér, J. A Decomposition Method for Global Evaluation of Shannon Entropy and Local Estimations of Algorithmic Complexity. Entropy 2018, 20, 605. [CrossRef]

- Roux, T. Interdisciplinary synergies in comparative research on constitutional judicial decision-making. Verfassung Recht Übersee 2019, 52, 413-438. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27005200.

- Jakimowicz, A. The Role of Entropy in the Development of Economics. Entropy 2020, 22, 452. [CrossRef]

- Dimpfl, T., Peter, F. J. Group transfer entropy with an application to cryptocurrencies. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 516, 543-551. [CrossRef]

- Grilli, L., Santoro, D. Forecasting financial time series with Boltzmann entropy through neural networks. Comput. Manag. Sci. 2022, 19, 665-681. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Ku, S., Chang, W., Song, J. W. Predicting the direction of US stock prices using effective transfer entropy and machine learning techniques. IEEE Access. 2020, 8, 111660-111682. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L., Yang, H. Transfer entropy calculation for short time sequences with application to stock markets. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 2020, 559, 125121. [CrossRef]

- Li, A. W., Bastos, G. S. Stock market forecasting using deep learning and technical analysis: A systematic review. IEEE Access. 2020, 8, 185232-185242. [CrossRef]

- Natal, J.; Ávila, I.; Tsukahara, V.B.; Pinheiro, M.; Maciel, C.D. Entropy: From Thermodynamics to Information Processing. Entropy 2021, 23, 1340. [CrossRef]

- Tsallis, C. Entropy. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 264-300. [CrossRef]

- Filina, E.; Shindina, T. Organization of Support and Education for Adults in the Context of Transition to the Concept of Information Society. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Information Technologies in Engineering Education (Inforino), Moscow, Russian Federation, 2024; pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Torkayesh, A.E.; Santibanez-Gonzalez, E.D.R.; Otaghsara, S.K. Evaluation of renewable energy resources using integrated Shannon Entropy—EDAS model. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2020, 1, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Ayyub, B.M. Shannon Entropy for Quantifying Uncertainty and Risk in Economic Disparity. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 2160–2181. [CrossRef]

- Corral, Á.; García del Muro, M. From Boltzmann to Zipf through Shannon and Jaynes. Entropy 2020, 22, 179. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-Y. Measuring Entropy in Business Process Models. In Proceedings of the 2008 3rd International Conference on Innovative Computing Information and Control, Dalian, China, 18-20 June 2008. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-Y.; Chin, C.-H.; Cardoso, J. An Entropy-Based Uncertainty Measure of Process Models. Inf. Process. Lett. 2011, 111. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, E., & Anees, T. Challenges and Solutions for Processing Real-Time Big Data Stream: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 119123-119143. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, M.H.; Pohl, C.; Bina, O.; Varanda, M. Who is doing inter- and transdisciplinary research, and why? An empirical study of motivations, attitudes, skills, and behaviours. Futures 2019, 112, 102441. [CrossRef]

- Smolyak, A.; Havlin, S. Three Decades in Econophysics—From Microscopic Modelling to Macroscopic Complexity and Back. Entropy 2022, 24, 271. [CrossRef]

- Finn, K.; Karamitsos, S.; Pilaftsis, A. Eisenhart lift for field theories. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 016015. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.M. Entropy and Information Content of Geostatistical Models. Math Geosci 2021, 53, 163–184. [CrossRef]

- Kissa, B.; Gounopoulos, E.; Kamariotou, M.; Kitsios, F. Business Process Management Analysis with Cost Information in Public Organizations: A Case Study at an Academic Library. Modelling 2023, 4, 251-263. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, H.; Dai, W.; et al. An Entropy-Based Clustering Ensemble Method to Support Resource Allocation in Business Process Management. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2016, 48, 305-330. [CrossRef]

- Dinga, E.; Tănăsescu, C.-R.; Ionescu, G.-M. Social Entropy and Normative Network. Entropy 2020, 22, 1051. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Xiao, W.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Z.; Yang, D.; Liu, H.; Liang, B.; Fu, J. Application Research On Real-Time Perception Of Device Performance Status. arXiv 2024, 2409.03218. [CrossRef]

- Landi, G.T.; Paternostro, M. Irreversible entropy production: From classical to quantum. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 035008. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z. Learning to Recommend via Random Walk with Profile of Loan and Lender in P2P Lending. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 174, 114763. [CrossRef]

- Çengel, Y.A. On Entropy, Information, and Conservation of Information. Entropy 2021, 23, 779. [CrossRef]

- Arhami, M.; Desiani, A.; Munawar; Hayati, R. Eco-informatics: The Encouragement of Ecological Data Management. In Proceedings of MICoMS 2017 (Emerald Reach Proceedings Series, Vol. 1), Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 555-561. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Pereira, É.J.A.L.; Pereira, H.B.B. From Big Data to Econophysics and Its Use to Explain Complex Phenomena. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 153. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Khurana, P. Growth and Dynamics of Econophysics: A Bibliometric and Network Analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 4417-4436. [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, F.; Mantegna, R.N.; Schinckus, C. When financial economics influences physics: The role of Econophysics. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2019, 65, 101378. [CrossRef]

- Udriste, C.; Ferrara, M.; Tevy, I.; Zugravescu, D.; Munteanu, F. Entropy of Reissner–Nordström 3D Black Hole in Roegenian Economics. Entropy 2019, 21, 509. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L.A.; Stewart, L.A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Welch, V.A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Thomas, J.; Oliver, S. Clarifying differences between reviews within evidence ecosystems. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D. Reporting guidelines: doing better for readers. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 1-3 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, V.; Beaudart, C.; Ajamieh, S.; Rabenda, V.; Tirelli, E.; Bruyère, O. Meta-analyses indexed in PsycINFO had a better completeness of reporting when they mention PRISMA. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 115, 46-54. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, I.J.; Wallace, B.C. Toward systematic review automation: a practical guide to using machine learning tools in research synthesis. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 163. [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, J.E.; Brennan, S.E. Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2019; Chapter 12, pp. 321-346. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; López-López, J.A.; Becker, B.J., et al. Synthesising quantitative evidence in systematic reviews of complex health interventions. BMJ Global Health 2019, 4, e000858. [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [CrossRef]

- Hultcrantz, M.; Rind, D.; Akl, E.A. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 87, 4-13. [CrossRef]

- PRISMA. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Dekkers, O.M.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Cevallos, M.; Renehan, A.G.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M. COSMOS-E: Guidance on Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies of Etiology. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002742. [CrossRef]

- EFQM. Available online: https://efqm.org/about/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- ISO. Available online: https://www.iso.org/about-us.html (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- ARIS. Available online: https://www.softwareag.com/en_corporate/platform/aris.html (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- SAP. Available online: https://community.sap.com/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Object Management Group. Available online: https://www.omg.org/about (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379-423, 623-656. [CrossRef]

- Clausius, R.J.E. Ueber verschiedene für die Anwendungen bequeme Formen der Hauptgleichungen der mechanischen Wärmetheorie. Annalen der Physik 1865, 125, 353-400. [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. Weitere Studien über das Wörmegleichgewicht unter Gasmolekülen. Sitzungsberichte Akad. Wiss., Vienna, part II, 66, 275–370 (1872); reprinted in Boltzmann's Wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen, Vol. I, J.A. Barth: Leipzig, Germany, 1909, pp. 316-402. [CrossRef]

- Popovic, M. Researchers in an Entropy Wonderland: A Review of the Entropy Concept. arXiv 2017. [CrossRef]

- Dumas, M.; van der Aalst, W.; ter Hofstede, A.H.M.; Oberweis, A.; Ellis, C.A.; Barthelmess, P.; Chen, J.; Wainer, J.; Bussler, C. Process-Aware Information Systems: Bridging People and Software Through Process Technology, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2005; pp. 3-82. [CrossRef]

- Schwerz, A.L.; Liberato, R.; Pu, C.; Ferreira, J.E. Robust and Reliable Process-Aware Information Systems. In IEEE Transactions on Services Computing, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 820-833, 1 May-June 2021. [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, M.; Fdhila, W.; Nardelli, M.; Rinderle-Ma, S.; Schulte, S. Event-based failure prediction in distributed business processes. Info. Syst. 2019, 81, 220-235. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mantilla, J.M.; Martínez-Zarzuelo, A.; Fernández-Cruz, F.J. Do ISO:9001 standards and EFQM model differ in their impact on the external relations and communication system at schools? Eval. Program Plann. 2020, 80, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Niknejad, N., Ismail, W., Ghani, I., Nazari, B., Bahari, M., & Hussin, A.R.B.C.. Understanding Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA): A systematic literature review and directions for further investigation. Inf. Syst. 2020, 91, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Szelągowski, M. Practical assessment of the nature of business processes. Inf. Syst. e-Bus. Manag. 2021, 19, 541-566. [CrossRef]

- Hasić, F.; De Smedt, J.; Vanthienen, J. Augmenting processes with decision intelligence: Principles for integrated modeling. Decis. Support Syst. 2018, 107, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Crespino, A.M.; Del Vecchio, V.; Gervasi, M.; Lazoi, M.; Marra, M. Evaluating maturity level of big data management and analytics in industrial companies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 196, 122826. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar, S.K. Project Management for Enterprise Applications. In Architecting High Performing, Scalable and Available Enterprise Web Applications, 2nd ed.; Shivakumar, S.K., Ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, USA, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 199–219. [CrossRef]

- Froger, M.; Bénaben, F.; Truptil, S.; Boissel-Dallier, N. A non-linear business process management maturity framework to apprehend future challenges. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 290-300. [CrossRef]

- Ubaid, A. M.; Dweiri, F. T. Business process management (BPM): terminologies and methodologies unified. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2020, 11, 1046-1064. [CrossRef]

- Kanger, L., & Sillak, S. Emergence, consolidation and dominance of meta-regimes: Exploring the historical evolution of mass production (1765-1972) from the Deep Transitions perspective. Technol. Soc. J. 2020, 63, 101393. [CrossRef]

- Endalamaw, A., Khatri, R.B., Mengistu, T.S., Erku, D., Wolka, E., Zewdie, A., & Assefa, Y. A scoping review of continuous quality improvement in healthcare system: conceptualization, models and tools, barriers and facilitators, and impact. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 487. [CrossRef]

- Goni, J. I. C.; Van Looy, A. Towards a Measurement Instrument for Assessing Capabilities When Innovating Less-Structured Business Processes. In Business Process Management Workshops. BPM 2023. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, Revised ed.; De Weerdt, J., Pufahl, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 492, pp. 229-240. [CrossRef]

- Nawari, O. N.; Ravindran, S. Blockchain and the built environment: Potentials and limitations. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 25, 100832. [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Guédria, W.; Panetto, H.; Barafort, B. A hybrid deep learning and ontology-driven approach to perform business process capability assessment. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 30, 100409. [CrossRef]

- Sejahtera Surbakti, F. P.; Wang, W.; Indulska, M.; Sadiq, S. Factors influencing effective use of big data: A research framework. Inf. Manag. J. 2020, 57, 103146. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Aeran, H.; Rathee, M. Quality management in healthcare: The pivotal desideratum. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2019, 9, 180-182. [CrossRef]

- Pakdil, F. Overview of Quality and Six Sigma. In: Six Sigma for Students. 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan, Cham: Switzerland, 2020; pp. 3-40. [CrossRef]

- Janoski, T.; Lepadatu, D. Mass Merchandizing and Lean Production at Walmart, Costco, and Amazon. In: The Cambridge International Handbook of Lean Production: Diverging Theories and New Industries around the World, 2nd ed.; Janoski, T., Lepadatu, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2021; pp. 350-374. [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, A.; Purwandari, B.; Budiardjo, E. K.; Solichah, I. Global Software Development and Capability Maturity Model Integration: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Informatics and Computing (ICIC), Palembang, Indonesia, 17-18 October 2018. [CrossRef]

- Westney, E. Reflecting on Japan’s contributions to management theory. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 19, 8-24. [CrossRef]

- Ricciotti, F. From value chain to value network: a systematic literature review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2020, 70, 191-212. [CrossRef]

- Eisenreich, A., Füller, J., Stuchtey, M., & Gimenez-Jimenez, D. Toward a circular value chain: Impact of the circular economy on a company's value chain processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134375. [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Gargallo, C., Zaragoza-Sáez, P. A comprehensive bibliometric study of the balanced scorecard. Eval. Program Plann. 2023, 97, 102256. [CrossRef]

- Röglinger, M., Plattfaut, R., Borghoff, V., Kerpedzhiev, G., Becker, J., Beverungen, D., vom Brocke, J., Van Looy, A., del-Río-Ortega, A., Rinderle-Ma, S., Rosemann, M., Santoro, F. M., Trkman, P. Exogenous Shocks and Business Process Management: A Scholars’ Perspective on Challenges and Opportunities. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2022, 64, 669-687. [CrossRef]

- Fetais, A., Abdella, G.M., Al-Khalifa, K.N., Hamouda, A.M. Business Process Re-Engineering: A Literature Review-Based Analysis of Implementation Measures. Inf. 2022, 13, 185. [CrossRef]

- Szelągowski, M.; Berniak-Woźny, J.; Lupeikiene, A. The Future Development of ERP: Towards Process ERP Systems? In Marrella, A., et al. Business Process Management: Blockchain, Robotic Process Automation, and Central and Eastern Europe Forum. BPM 2022. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, 1st ed.; van der Aalst, W., Mylopoulos, J., Ram, S., Rosemann, M., Szyperski, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 459, pp. 326-341. [CrossRef]

- Din, A. Muhammad, Asif, M., Awan, M.U., Thomas, G. What makes excellence models excellent: a comparison of the American, European and Japanese models, TQM J. 2021, 33, 1143-1162. [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, B., Krause, F., Schiller, A. Automated planning of process models: The construction of parallel splits and synchronizations, Decis. Support Syst. 2019, 125, 113096. [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Pineda, M., Posenato, R., Zerbato, F. TimeAwareBPMN-js: An editor and temporal verification tool for Time-Aware BPMN processes, SoftwareX 2022, 17, 100939. [CrossRef]

- Eder, J., Franceschetti, M., Lubas, J. Dynamic Controllability of Processes without Surprises. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1461. [CrossRef]

- Amjad, A.; Azam, F.; Anwar, M. W.; Butt, W. H.; Rashid, M. Event-Driven Process Chain for Modeling and Verification of Business Requirements-A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 9027-9048. [CrossRef]

- Polančič, G.; Orban, B. An Experimental Investigation of BPMN-Based Corporate Communications Modeling. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2023, 29, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Corradini, F.; Ferrari, A.; Fornari, F.; Gnesi, S.; Polini, A.; Re, B.; Spagnolo, G. O. A Guidelines framework for understandable BPMN models. Data Knowl. Eng. 2018, 113, 129-154. [CrossRef]

- Farshidi, S.; Kwantes, I. B.; Jansen, S. Business process modeling language selection for research modelers. Softw. Syst. Model. 2024, 23, 137-162. [CrossRef]

- Malinova, M.; Mendling, J. Identifying do’s and don’ts using the integrated business process management framework. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 882-899. [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, C.; Soares, I.; de Souza, D. Quality Measurement in Agile and Rapid Software Development. J. Syst. Softw. 2021, 111041. [CrossRef]

- Krhač Andrašec, E.; Kern, T.; Urh, B. An Innovative Approach to Organizational Changes for Sustainable Processes: A Case Study on Waste Minimization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15706. [CrossRef]

- Elkhovskaya, L.O.; Kshenin, A.D.; Balakhontceva, M.A.; Ionov, M.V.; Kovalchuk, S.V. Extending Process Discovery with Model Complexity Optimization and Cyclic States Identification: Application to Healthcare Processes. Algorithms 2023, 16, 57. [CrossRef]

- Cincotta, P.M.; Giordano, C.M.; Silva, R.A.; Beaugé, C. The Shannon entropy: An efficient indicator of dynamical stability. Phys. D 2021, 417, 132816. [CrossRef]

- Pluchino, A.; Burgio, G.; Rapisarda, A.; Biondo, A.E.; Pulvirenti, A.; et al. Exploring the Role of Interdisciplinarity in Physics: Success, Talent and Luck. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0218793. [CrossRef]

- Di Nunno, G.; Kubilius, K.; Mishura, Y.; Yurchenko-Tytarenko, A. From Constant to Rough: A Survey of Continuous Volatility Modeling. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4201. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M., Aldallal, R., Nassr, S. G., Al Mutairi, A., Yusuf, M., Mustafa, M. S., Alsolmi, M. M., Almetwally, E. M. A new improved form of the Lomax model: Its bivariate extension and an application in the financial sector. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 75, 127-138. [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, A. Big data in finance: Evidence and challenges. Borsa Istanbul Rev. 2019, 19, 283-287. [CrossRef]

- Woodward, J. Some reflections on Robert Batterman's a middle way. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 2024, 106, 2130. [CrossRef]

- Del Santo, F.; Gisin, N. Physics without determinism: Alternative interpretations of classical physics. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 100, 062107. [CrossRef]

- Schinckus, C. Agent-based modelling and economic complexity: A diversified perspective. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2019, 26, 170-188. [CrossRef]

- Parthey, H. Institutionalization, Interdisciplinarity, and Ambivalence in Research Situations. In The Responsibility of Science, 1st ed.; Mieg, H.A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 57, pp. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Tsintsaris, D.; Tsompanoglou, M.; Ioannidis, E. Dynamics of Social Influence and Knowledge in Networks: Sociophysics Models and Applications in Social Trading, Behavioral Finance and Business. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1141. [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.-T.; Hwang, E. Exponentially Weighted Multivariate HAR Model with Applications in the Stock Market. Entropy 2022, 24, 937. [CrossRef]

- Vilela, A.L.M.; Wang, C.; Nelson, K.P.; Stanley, H.E. Majority-vote model for financial markets. Physica A 2019, 515, 762-770. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Kandpal, V.; Agarwal, N.; Srivastava, B. Financial Inclusion and Its Ripple Effects on Socio-Economic Development: A Comprehensive Review. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2024, 17, 105. [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, E.; Varsakelis, N.; Antoniou, I. Change agents and internal communications in organizational networks. Physica A 2019, 528, 121385. [CrossRef]

- Kutner, R.; Ausloos, M.; Grech, D.; Di Matteo, T.; Schinckus, C.; Stanley, H.E. Econophysics and sociophysics: Their milestones & challenges. Physica A 2019, 516, 240-253. [CrossRef]

- Robledo, A.; Velarde, C. How, Why and When Tsallis Statistical Mechanics Provides Precise Descriptions of Natural Phenomena. Entropy 2022, 24, 1761. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, F. Modeling and Analysis of Social Phenomena: Challenges and Possible Research Directions. Entropy 2022, 24, 491. [CrossRef]

- Weinhardt, M. Big Data: Some Ethical Concerns for the Social Sciences. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 36. [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, I. Remembering Benoit Mandelbrot on his centennial–His fractal geometry changed our view of nature. Struct. Chem. 2024, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Schinckus, C. Ising model, econophysics and analogies. Phys. A 2018, 508, 95-103. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.Q.; Xie, W.J.; Zhou, W.X.; Sornette, D. Multifractal Analysis of Financial Markets: A Review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2019, 82, 125901. [CrossRef]

- Bardoscia, M.; Barucca, P.; Battiston, S.; Caccioli, F.; Cimini, G.; Garlaschelli, D.; Saracco, F.; Squartini, T.; Caldarelli, G. The Physics of Financial Networks. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 490-507. [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, F.; Livan, G.; Montagna, G.; Nicrosini, O. Modeling and simulation of financial returns under non-Gaussian distributions. Physica A 2023, 622, 128886. [CrossRef]

- Sobkowicz, P. Social Depolarization and Diversity of Opinions—Unified ABM Framework. Entropy 2023, 25, 568. [CrossRef]

- Kesić, S. Complexity and biocomplexity: Overview of some historical aspects and philosophical basis. Ecol. Complex. 2024, 57, 101072. [CrossRef]

- Ghavasieh, A.; De Domenico, M. The physics of complex networks. J. Phys. Complex. 2022, 3, 011001. [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Ren, J.; Zhang, D.; Kong, X.; Zhang, D.; Xia, F. Network embedding: Taxonomies, frameworks and applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2020, 38, 100296. [CrossRef]

- Ghavasieh, A.; Nicolini, C.; De Domenico, M. Statistical physics of complex information dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 102, 052304. [CrossRef]

- Ghavasieh, A.; De Domenico, M. Maximum entropy network states for coalescence processes. Physica A 2024, 643, 129752. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Huang, S.; Sun, X.; Hao, X.; An, F. Modelling cointegration and Granger causality network to detect long-term equilibrium and diffusion paths in the financial system. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 172092. [CrossRef]

- Galeano, P.; Peña, D. Data science, big data and statistics. TEST 2019, 28, 289-329. [CrossRef]

- Sezer, O.B.; Gudelek, M.U.; Ozbayoglu, A.M. Financial time series forecasting with deep learning: A systematic literature review: 2005–2019. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 90, 106181. [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L.M.; Balcı, M.A.; Akgüller, Ö.; Gaban, L. What Drives Economic Growth across European Countries? A Multimodal Approach. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3660. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.O.; Pernoud, A. Systemic Risk in Financial Networks: A Survey. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.12702. https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.12702.

- Liu, J.; Xie, W.; Liu, S. Understanding Nursing Informatics: A Survey of Nurses' Perception. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2024, 315, 627-628. [CrossRef]

- Panayides, A.S.; et al. AI in Medical Imaging Informatics: Current Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 1837-1857. [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.; Moon, S.; Prokop, L.J.; Montori, V.M.; Fan, J.W. A scoping review of medical practice variation research within the informatics literature. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2022, 165, 104833. [CrossRef]

- López-López, E.; Bajorath, J.; Medina-Franco, J.L. Informatics for Chemistry, Biology, and Biomedical Sciences. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 26-35. [CrossRef]

- Bielińska-Wąż, D.; Wąż, P.; Błaczkowska, A.; Mandrysz, J.; Lass, A.; Gładysz, P.; Karamon, J. Mathematical Modeling in Bioinformatics: Application of an Alignment-Free Method Combined with Principal Component Analysis. Symmetry 2024, 16, 967. [CrossRef]

- Foth, M. Participatory urban informatics: towards citizen-ability. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2018, 7, 4-19. [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Pattanaik, M.; Basantia, S.; Mishra, R.; Das, D.; Sahoo, K.; Paital, B. Informatics on a social view and need of ethical interventions for wellbeing via interference of artificial intelligence. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2023, 11, 100065. [CrossRef]

- Upward, F. The monistic diversity of continuum informatics: A method for analysing the relationships between recordkeeping informatics, ethics and information governance. Records Manag. J. 2019, 29, 258-271. [CrossRef]

- Colomer, C.; Dhamala, M.; Ganesh, G.; Lagarde, J. Granger Geweke Causality Reveals Information Exchange During Physical Interaction is Modulated by Task Difficulty. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2023, 92, 103139. [CrossRef]

- Shojaie, A.; Fox, E.B. Granger Causality: A Review and Recent Advances. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 2022, 9, 289-319. [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.S.; Lam, W.H.; Jaaman, S.H.; Lee, P.F. Bibliometric Analysis of Granger Causality Studies. Entropy 2023, 25, 632. [CrossRef]

- Maghyereh, A., Abdoh, H., Awartani, B. Have returns and volatilities for financial assets responded to implied volatility during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Commodity Mark. 2022, 26, 100194. [CrossRef]

- Saslow, W.M. A History of Thermodynamics: The Missing Manual. Entropy 2020, 22, 77. [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.-W.; Guo, Z.-Y. What Is the Real Clausius Statement of the Second Law of Thermodynamics? Entropy 2019, 21, 926. [CrossRef]

- Groumpos, P.P. A Critical Historical and Scientific Overview of all Industrial Revolutions. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 464-471. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Ó Gráda, C. Connecting the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions: The Role of Practical Mathematics. Working Papers 202017, School of Economics, University College Dublin, 2020.

- Lopes Coelho, R. On the Energy Concept Problem: Experiments and Interpretations. Found Sci 2021, 26, 607–624. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.M.; Kandasamy, S.A.S. Concepts and Contexts: The Interplay of Philosophy and History in Understanding Human Society. EAJMR 2023, 2, 2581–2590. [CrossRef]

- Gedde, U.W. An Introduction to Thermodynamics and the First Law. In Essential Classical Thermodynamics; SpringerBriefs in Physics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Lucia, U.; Grisolia, G. Nonequilibrium Temperature: An Approach from Irreversibility. Materials 2021, 14, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Namdari, A.; Li, Z. (Steven). A review of entropy measures for uncertainty quantification of stochastic processes. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2019, 11, 1687814019857350. [CrossRef]

- Sciortino, F. Entropy in self-assembly. Riv. Nuovo Cim. 2019, 42, 511-548. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.; Henriques, T.; Castro, L.; Souto, A.; Antunes, L.; Costa-Santos, C.; Teixeira, A. The Entropy Universe. Entropy 2021, 23, 222. [CrossRef]

- Schmelzer, J.W.P.; Tropin, T.V. Glass Transition, Crystallization of Glass-Forming Melts, and Entropy. Entropy 2018, 20, 103. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, J. Twenty Years of Entropy Research: A Bibliometric Overview. Entropy 2019, 21, 694. [CrossRef]

- Sands, D. The Carnot Cycle, Reversibility and Entropy. Entropy 2021, 23, 810. [CrossRef]

- Tsallis, C. Black Hole Entropy: A Closer Look. Entropy 2020, 22, 17. [CrossRef]

- Sheykhi, A. Modified cosmology through Barrow entropy. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 023505. [CrossRef]