Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Providing a segmentation strategy that separates the process into manageable sub-stages for separate analysis.

- Overall analysis of recorded event logs and organizational resources or staff involved in the lending process.

- Identifying bottlenecks, deviations, and areas for improvement through process analysis.

- The paper extracts KPIs from the perspectives of organizational resources and individual cases, using Alpha, Inductive, and Heuristic miners to construct process diagrams.

- These KPIs are then evaluated using a scenario-based robust DEA model to rank the performance of employees, providing a robust framework for resource performance assessment and optimization.

- The study integrates machine learning prediction and behavior analysis to anticipate future trends, optimize operations, and drive continuous improvement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Process Mining

2.1.1. Foundational Concepts and Techniques

2.1.2. Practical Tools and Implementation

2.1.3. Ethical Considerations and Collaborative Efforts

2.2. Business Process Mining – BPI Challenge 2012

2.3. Data Envelopment Analysis

2.4. Robust Scenario-Based Data Envelopment Analysis

2.5. Supervised Learning

2.5.1. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

2.5.2. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

2.5.3. Gradient Boosting (GB)

2.5.4. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks

2.5.6. Predicting Next Activity

2.6. Behavior Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Preparation

3.2. Process Mining Techniques

| Algorithm 1 IM Algorithm |

|

1. For each activity in activities, do: 2. Compute the connected activities of a distinct, unrelated group G 3. If the length of any connected activities in G is greater than one, then: 4. Return the connected activities as a cut partition 5. End if 6. End for. 7. For each activity in activities, do: 8. Given a set of activities, A: 9. Classify activities into groups such that each group has a start and end activity, and the activities between them directly follow relations 10. Partition A into groups {P1,…., Pn} such that there are no pairwise reachable activities in different groups 11. Merge the pairwise unreachable activities to create the final groups {P1,…., Pn} 12. Order the resulting groups 13. If {n > 1} then: 14. Return {P1,…., Pn } as a cut partition 15. End if 16. End for 17. For each activity in `activities` do: 18. Given a set of activities A: 19. For each group G do: 20. If G does not have a start or end activity, then: 21. Merge G with another arbitrary group 22. End if 23. End for 24. Partition the resulting sub-groups 25. If the partition has a length greater than one, then: 26. Return the resulting partition as a cut partition 27. End if 28. End for 29. For each activity in `activities` do: 30. P1 set of all start and end activities in L 31. {P2,…., Pn} partition of all other activities in L such that with Pi and β ∈ Pj implies i< j 32. For i ←2 to n do: 33. If Pi is connected to P1 through a start or end activity, then: 34. Merge Pi with P1 35. Else if Pi has an activity connected to some but not all start activities of P1, then: 36. Merge Pi with P1 37. Else if Pi has an activity connected from some but not all end activities of P1, then: 38. Merge Pi with P1 39. End if 40. End for 41. If {n > 1} then: 42. Return {P1,…., Pn} as cut partition 43. End if 44. End for |

| Algorithm 2 HM Algorithm |

|

1. Initialize empty set A of candidate activities 2. Initialize empty set S of candidate sequences 3. Initialize empty process model M 4. For each trace t in L, do: 5. For each activity a in t do: 6. Add a to A 7. End for. 8. For i from 1 to length(t) - 1 do: 9. For j from i + 1 to length(t) do: 10. s ← sequence of activities from ti to tj 11. Add s to S 12. End for 13. End for 14. End for 15. For each candidate sequence s in S, do: 16. count ← frequency of s in L 17. If count f then: 18. Add s to M 19. End if 20. End for 21. Refine M using optimization heuristics 22. Return M |

3.3. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)

3.4. Robust Optimizations

| Indices |

|

Parameters Parameters |

3.5. Robust Optimization DEA

3.6. Prediction

3.6.1. Loan Receiving Prediction

3.6.2. Next Activity Prediction

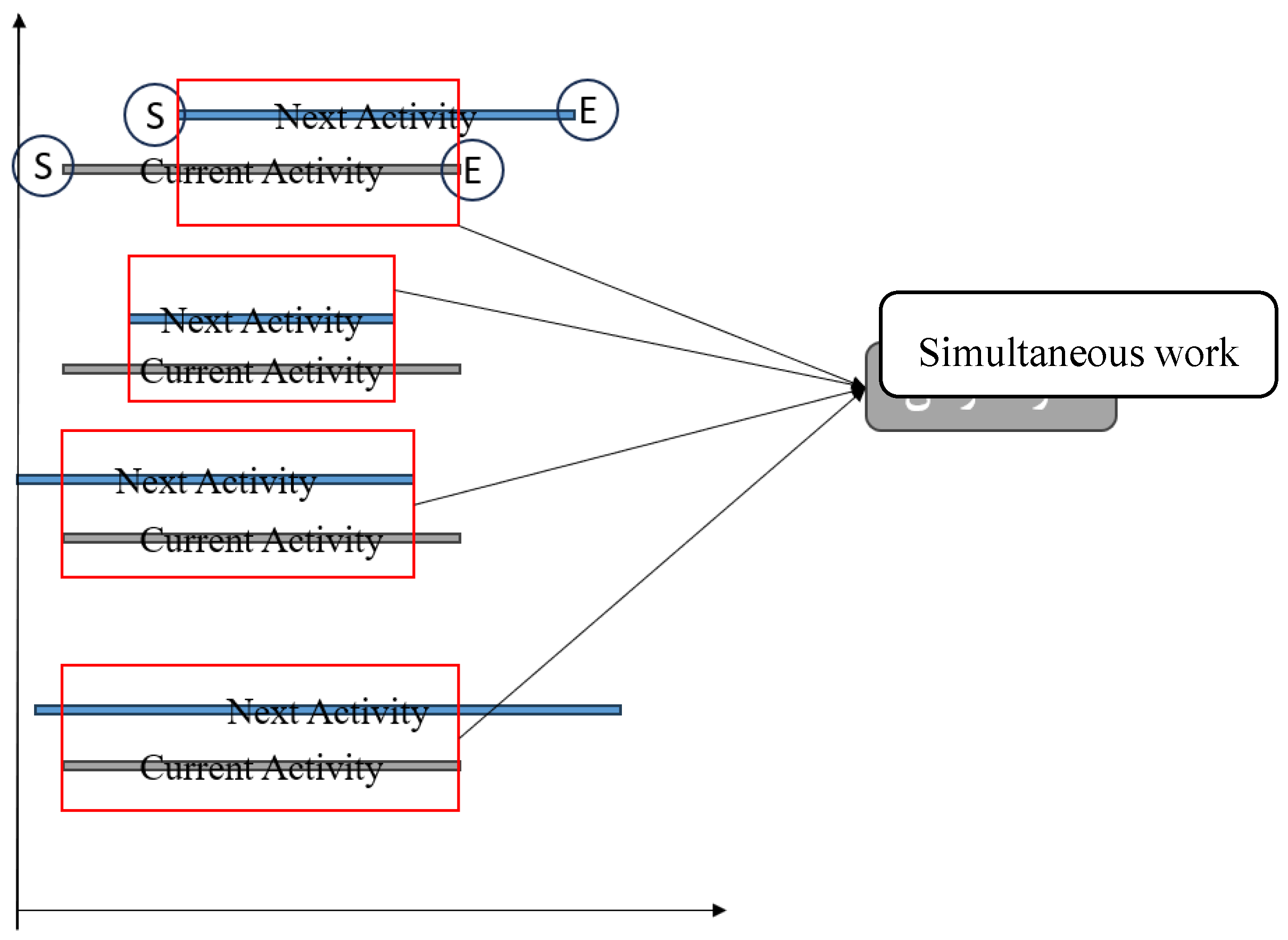

3.7. Behavior Analysis

- 1)

- Model Selection: Choose a range of customer behavior models, including NBD, Pareto/NBD, BG/NBD, MBG/NBD, BG/CNBD-k, MBG/CNBD-k, hierarchical Bayes variant of Pareto/NBD, Pareto/NBD (Abe), and Pareto/GGG.

- 2)

- Dataset Preparation: To test the models, collect and prepare datasets reflecting various customer behaviors and resource usage patterns (extracted KPIs).

- 3)

- Model Implementation: Implement and calibrate each model to fit the prepared datasets, adjusting for specific dataset characteristics.

- 4)

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate model performance using metrics such as Log-likelihood and mean error.

- 5)

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the models based on performance metrics to identify their strengths, weaknesses, and optimal use cases.

- 6)

- Integration with DEA: Incorporate the best-performing models into the DEA framework to predict future resource efficiency, adjust for uncertainty, and validate effectiveness.

3.8. Tools and Software

4. Results and Discussions

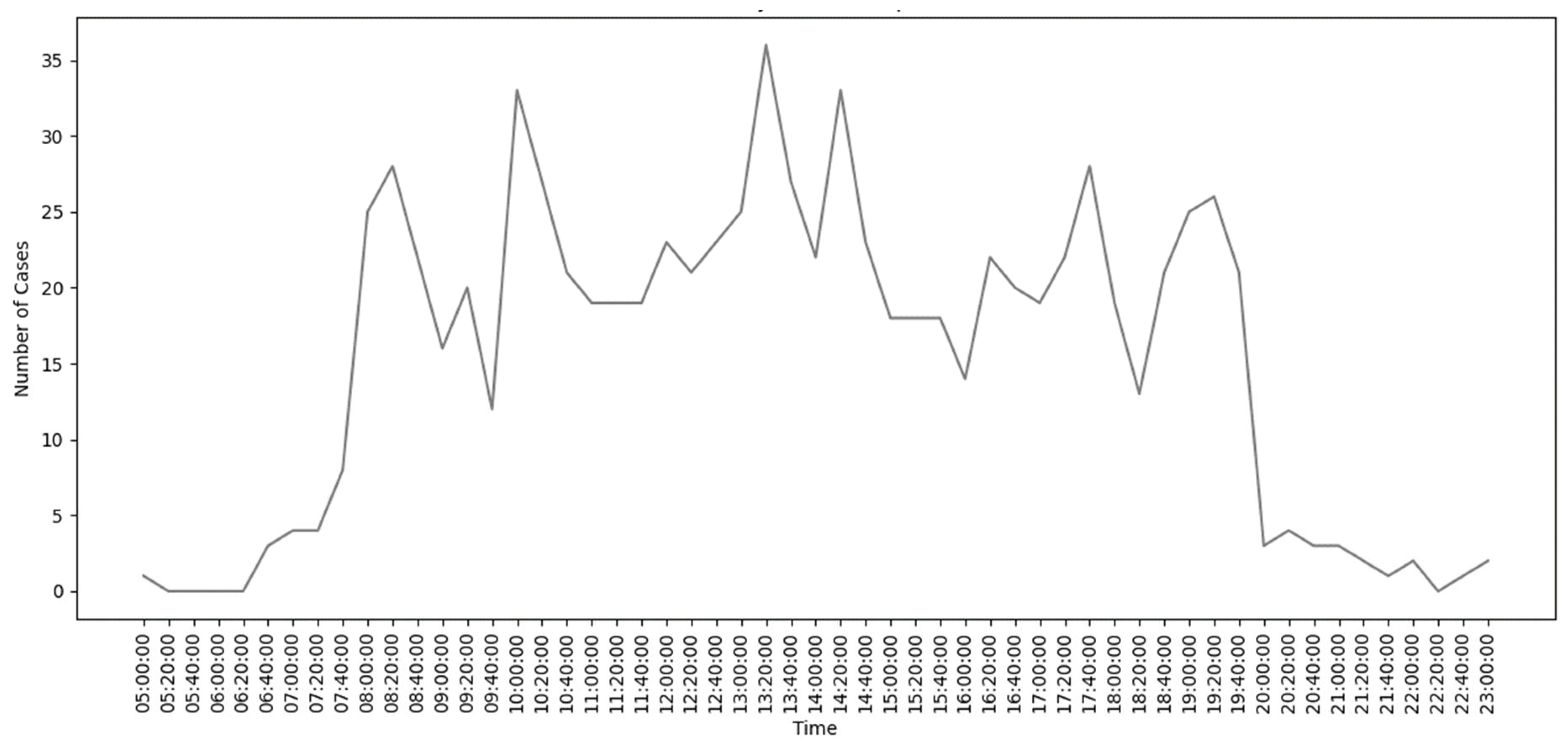

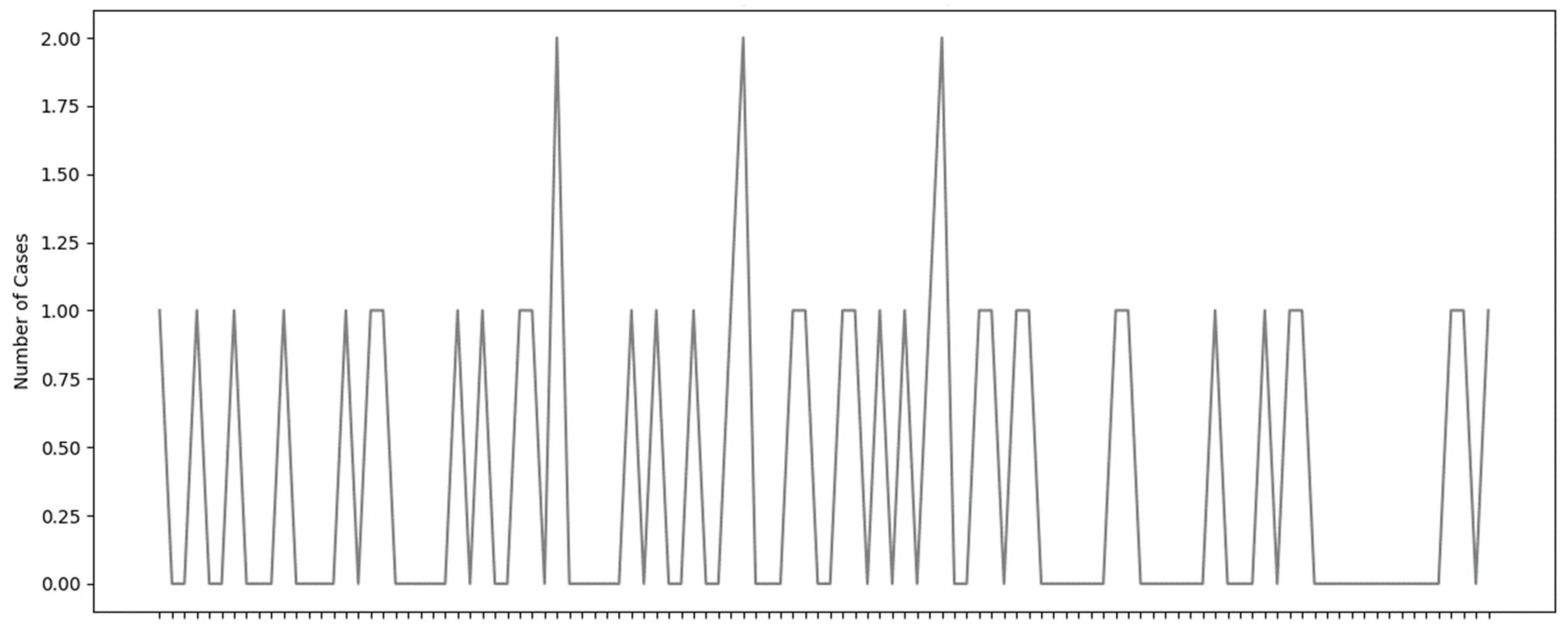

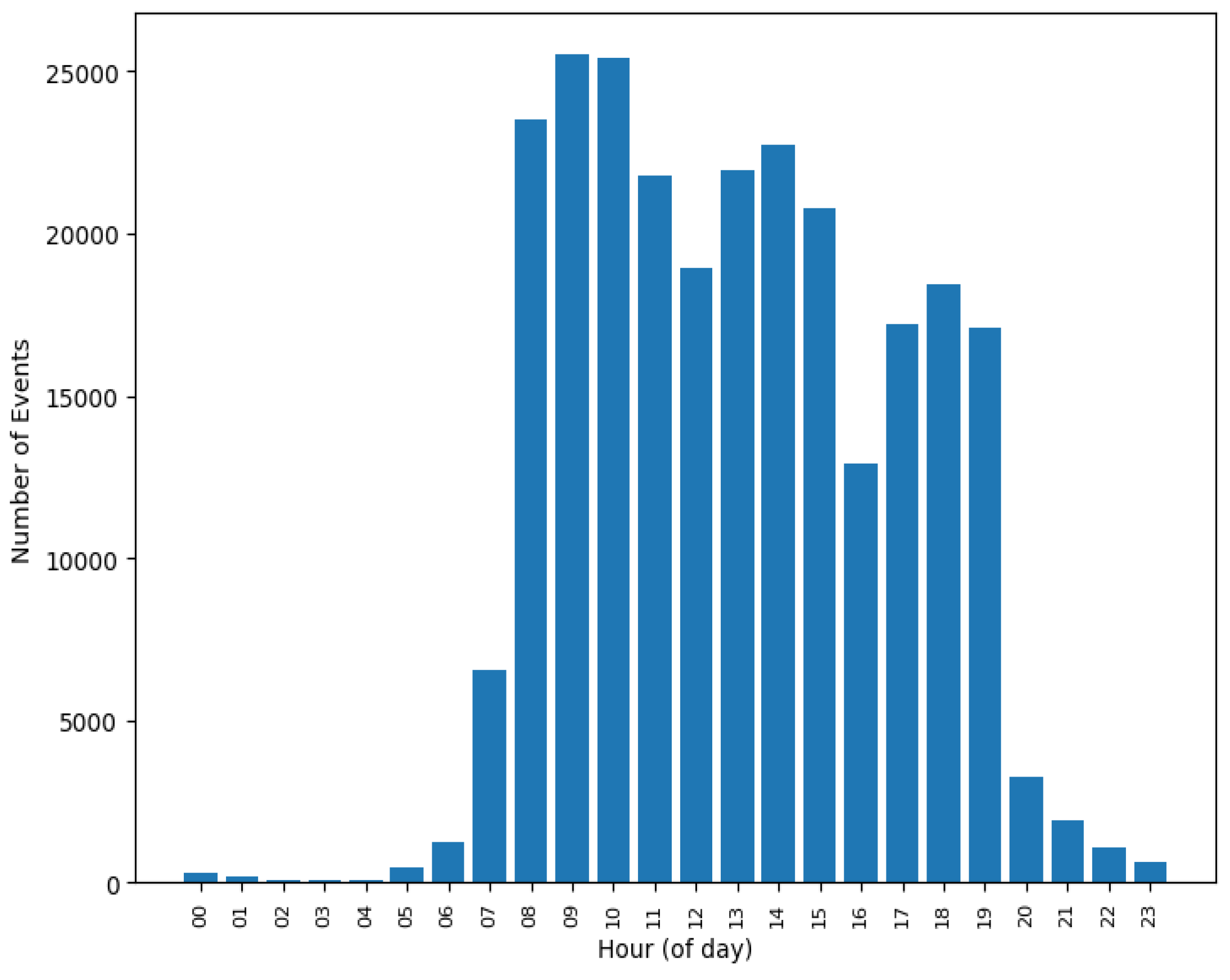

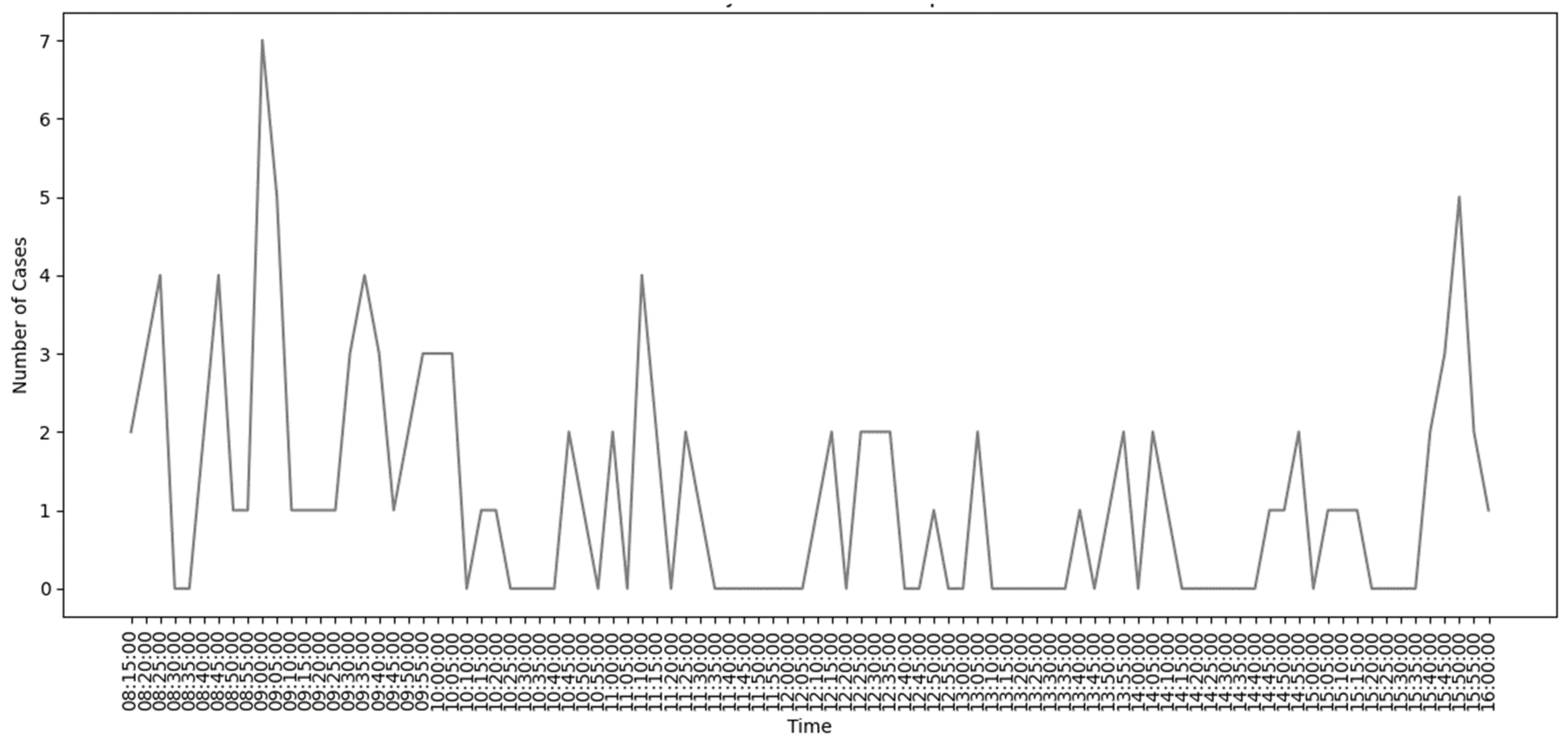

4.1. Event Log Data Analysis

4.2. Rework

| Activity | Rework count |

| O_CANCELLED | 749 |

| O_CREATED | 1438 |

| O_SELECTED | 1438 |

| O_SENT | 1438 |

| O_SENT_BACK | 197 |

| W_Afhandelen leads | 4755 |

| W_Beoordelen fraude | 108 |

| W_Completeren aanvraag | 7367 |

| W_Nabellen incomplete dossiers | 1647 |

| W_Nabellen offertes | 5011 |

| W_Valideren aanvraag | 3210 |

| W_Wijzigen contractgegevens | 4 |

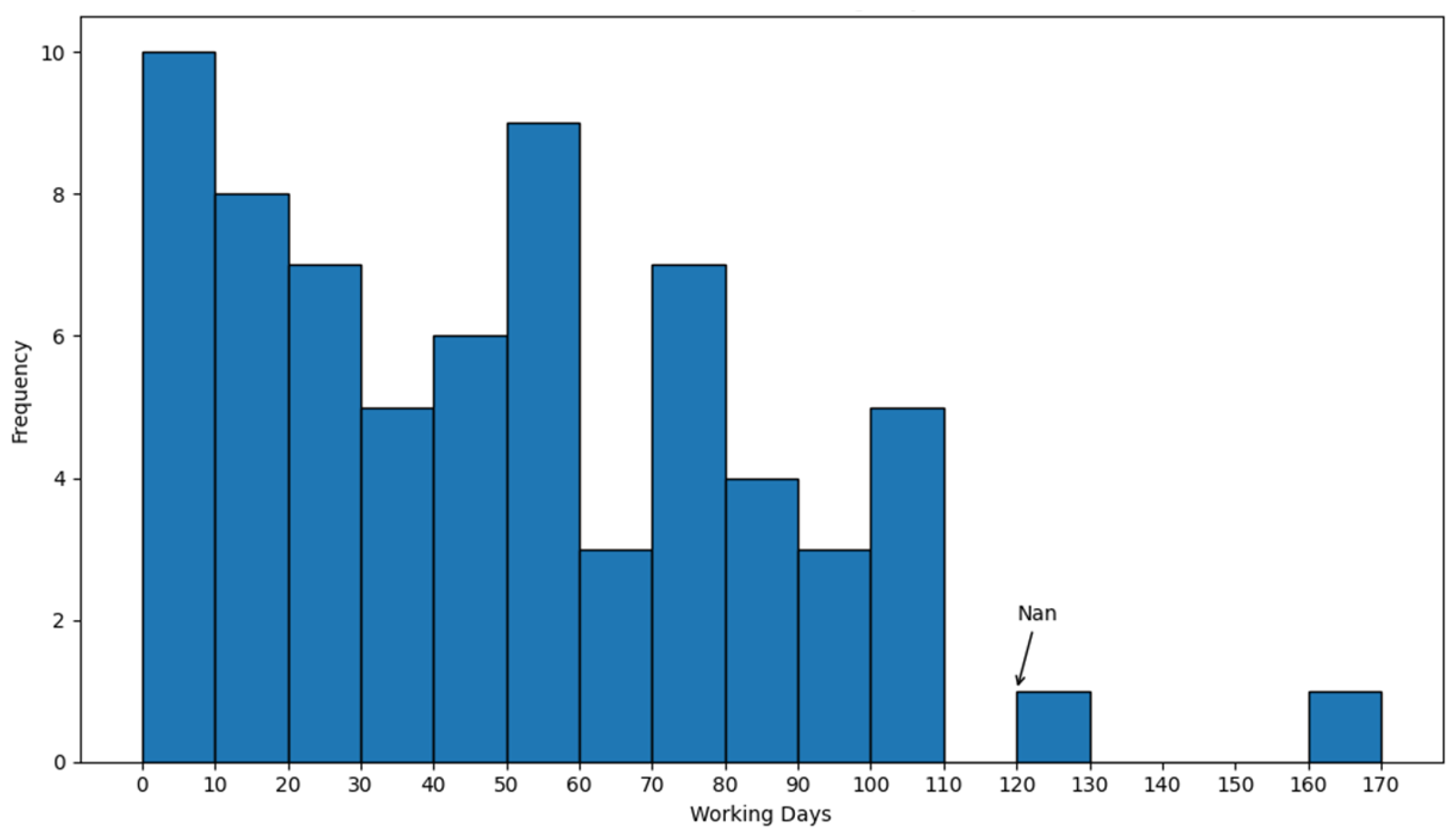

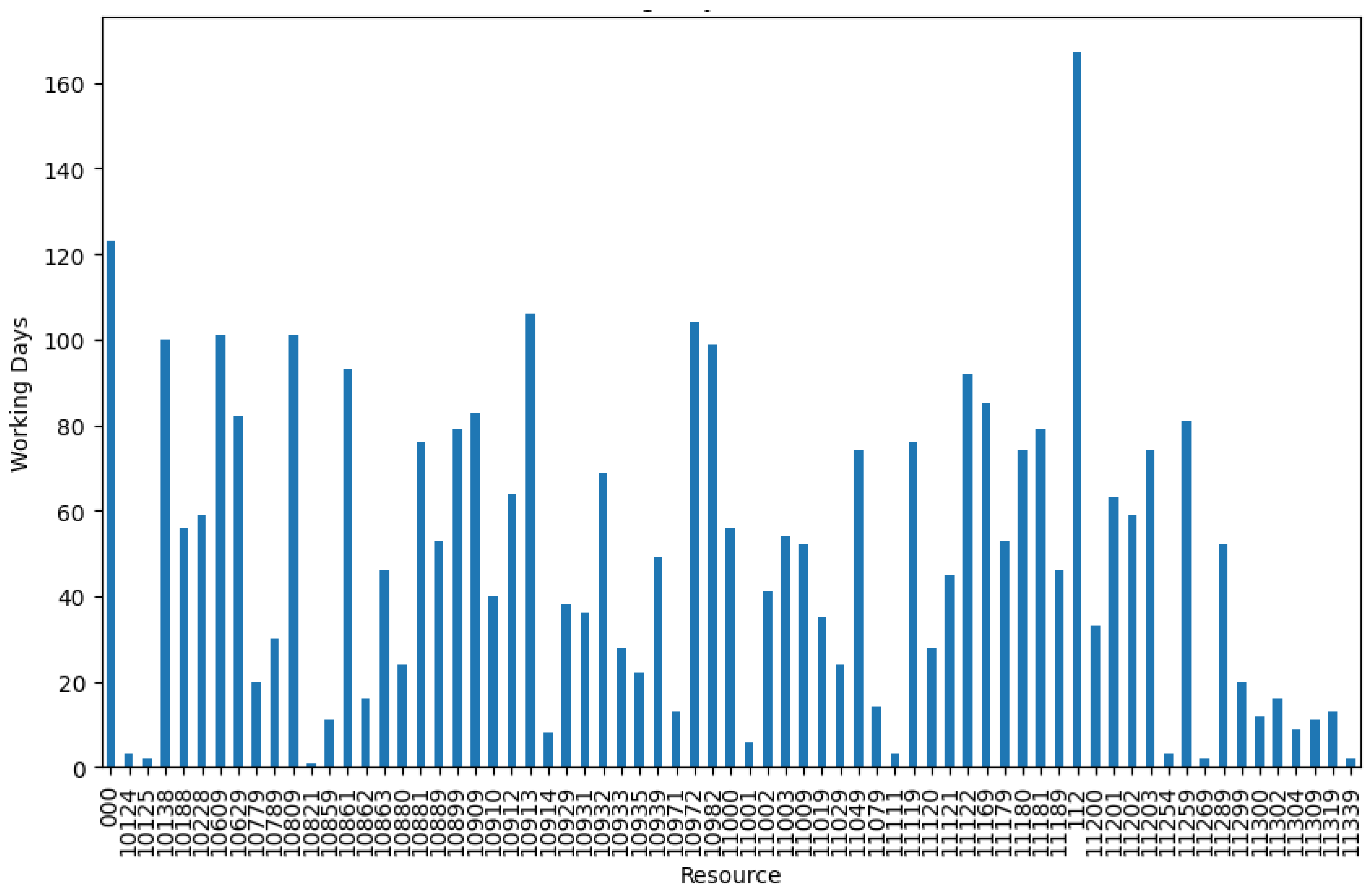

4.3. Work Resources and Activity Time

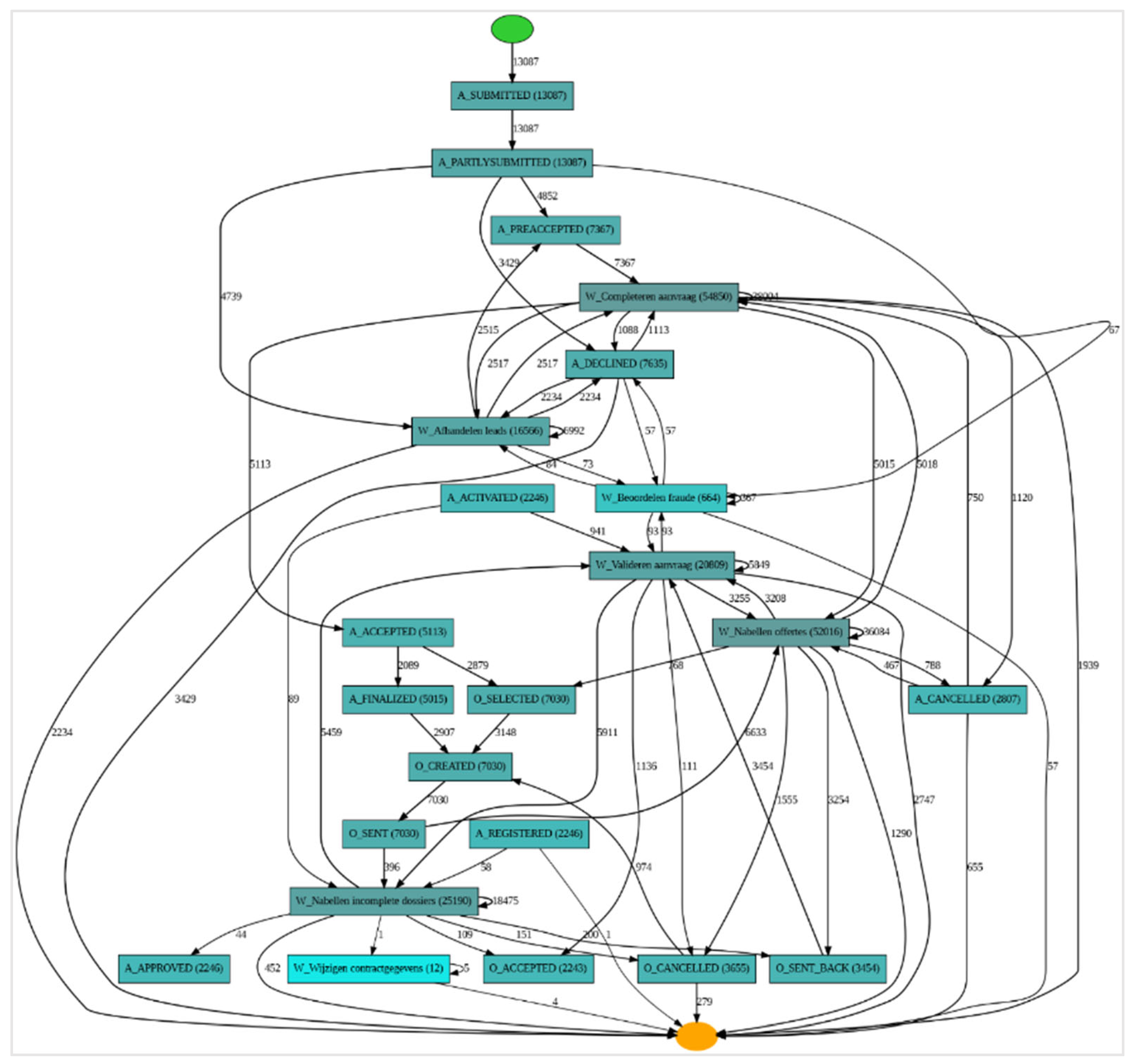

4.4. Process Discovery

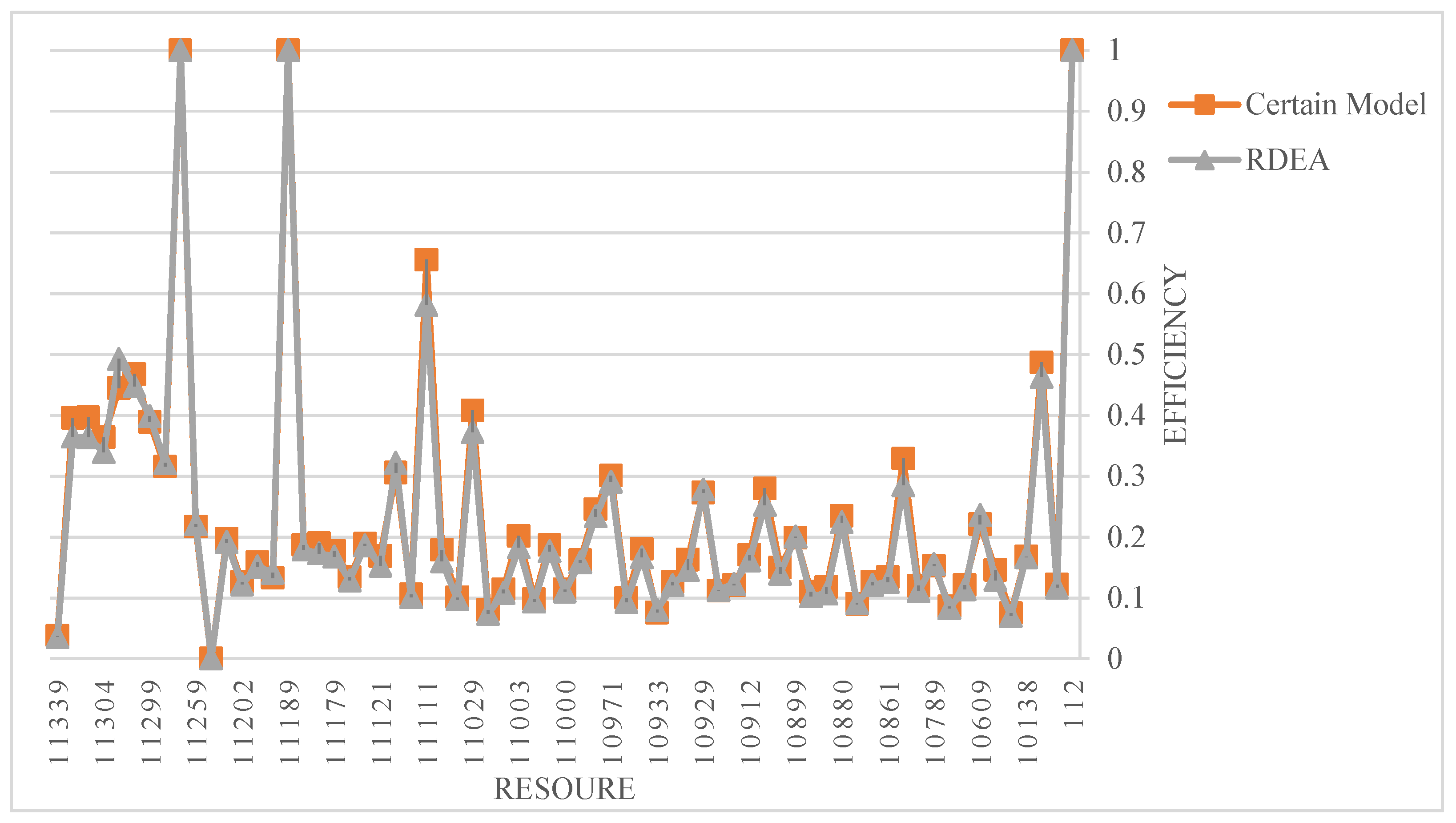

4.5. Proposed RDEA Implication

| Inputs | Outputs |

| total idle time | average work time |

| = average idle time | total work time |

| = duration of simultaneous work | = amount of loan processed |

| the number of scheduled tasks | = average time present in the event log |

| = number of completed case | |

| = number of reviewed cases | |

| = number of cases with the same start and end resources |

| DMU | Scenarios | Rank | ||

| W1 | W2 | W3 | ||

| 112 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 |

| 10124 | 0.097 | 0.122 | 0.138 | 49 |

| 10125 | 0.432 | 0.487 | 0.468 | 6 |

| 10138 | 0.156 | 0.168 | 0.18 | 32 |

| 10188 | 0.055 | 0.075 | 0.085 | 65 |

| 10228 | 0.093 | 0.146 | 0.154 | 42 |

| 10609 | 0.25 | 0.221 | 0.241 | 19 |

| 10629 | 0.098 | 0.121 | 0.126 | 50 |

| 10779 | 0.077 | 0.086 | 0.088 | 62 |

| 10789 | 0.157 | 0.153 | 0.158 | 36 |

| 10809 | 0.084 | 0.12 | 0.136 | 52 |

| 10859 | 0.215 | 0.329 | 0.314 | 16 |

| 10861 | 0.106 | 0.134 | 0.142 | 44 |

| 10862 | 0.111 | 0.126 | 0.128 | 47 |

| 10863 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.096 | 61 |

| 10880 | 0.194 | 0.235 | 0.25 | 21 |

| 10881 | 0.091 | 0.118 | 0.113 | 55 |

| 10889 | 0.086 | 0.11 | 0.114 | 56 |

| 10899 | 0.209 | 0.199 | 0.193 | 23 |

| 10909 | 0.119 | 0.15 | 0.152 | 41 |

| 10910 | 0.197 | 0.28 | 0.287 | 18 |

| 10912 | 0.141 | 0.171 | 0.176 | 33 |

| 10913 | 0.127 | 0.121 | 0.121 | 45 |

| 10914 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.117 | 51 |

| 10929 | 0.273 | 0.273 | 0.293 | 17 |

| 10931 | 0.108 | 0.163 | 0.172 | 39 |

| 10932 | 0.108 | 0.126 | 0.131 | 48 |

| 10933 | 0.084 | 0.076 | 0.083 | 63 |

| 10935 | 0.142 | 0.181 | 0.179 | 31 |

| 10939 | 0.081 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 60 |

| 10971 | 0.269 | 0.301 | 0.306 | 15 |

| 10972 | 0.207 | 0.246 | 0.253 | 20 |

| 10982 | 0.151 | 0.162 | 0.164 | 35 |

| 11000 | 0.094 | 0.114 | 0.129 | 53 |

| 11001 | 0.168 | 0.187 | 0.173 | 28 |

| 11002 | 0.089 | 0.098 | 0.095 | 59 |

| 11003 | 0.15 | 0.202 | 0.199 | 26 |

| 11009 | 0.1 | 0.114 | 0.11 | 54 |

| 11019 | 0.061 | 0.08 | 0.082 | 64 |

| 11029 | 0.324 | 0.408 | 0.384 | 9 |

| 11049 | 0.094 | 0.101 | 0.098 | 58 |

| 11079 | 0.115 | 0.179 | 0.194 | 34 |

| 11111 | 0.476 | 0.656 | 0.612 | 4 |

| 11119 | 0.092 | 0.106 | 0.107 | 57 |

| 11120 | 0.352 | 0.306 | 0.307 | 13 |

| 11121 | 0.125 | 0.169 | 0.167 | 37 |

| 11122 | 0.178 | 0.189 | 0.192 | 25 |

| 11169 | 0.125 | 0.134 | 0.126 | 43 |

| 11179 | 0.149 | 0.177 | 0.18 | 30 |

| 11180 | 0.144 | 0.19 | 0.187 | 29 |

| 11181 | 0.159 | 0.187 | 0.196 | 27 |

| 11189 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 |

| 11200 | 0.145 | 0.133 | 0.15 | 40 |

| 11201 | 0.144 | 0.159 | 0.151 | 38 |

| 11202 | 0.11 | 0.126 | 0.134 | 46 |

| 11203 | 0.171 | 0.197 | 0.211 | 24 |

| 11254 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 67 |

| 11259 | 0.226 | 0.217 | 0.222 | 22 |

| 11269 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 |

| 11289 | 0.329 | 0.316 | 0.321 | 14 |

| 11299 | 0.408 | 0.389 | 0.402 | 8 |

| 11300 | 0.391 | 0.468 | 0.495 | 7 |

| 11302 | 0.569 | 0.445 | 0.463 | 5 |

| 11304 | 0.28 | 0.364 | 0.385 | 12 |

| 11309 | 0.32 | 0.397 | 0.373 | 11 |

| 11319 | 0.28 | 0.396 | 0.434 | 10 |

| 11339 | 0.033 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 66 |

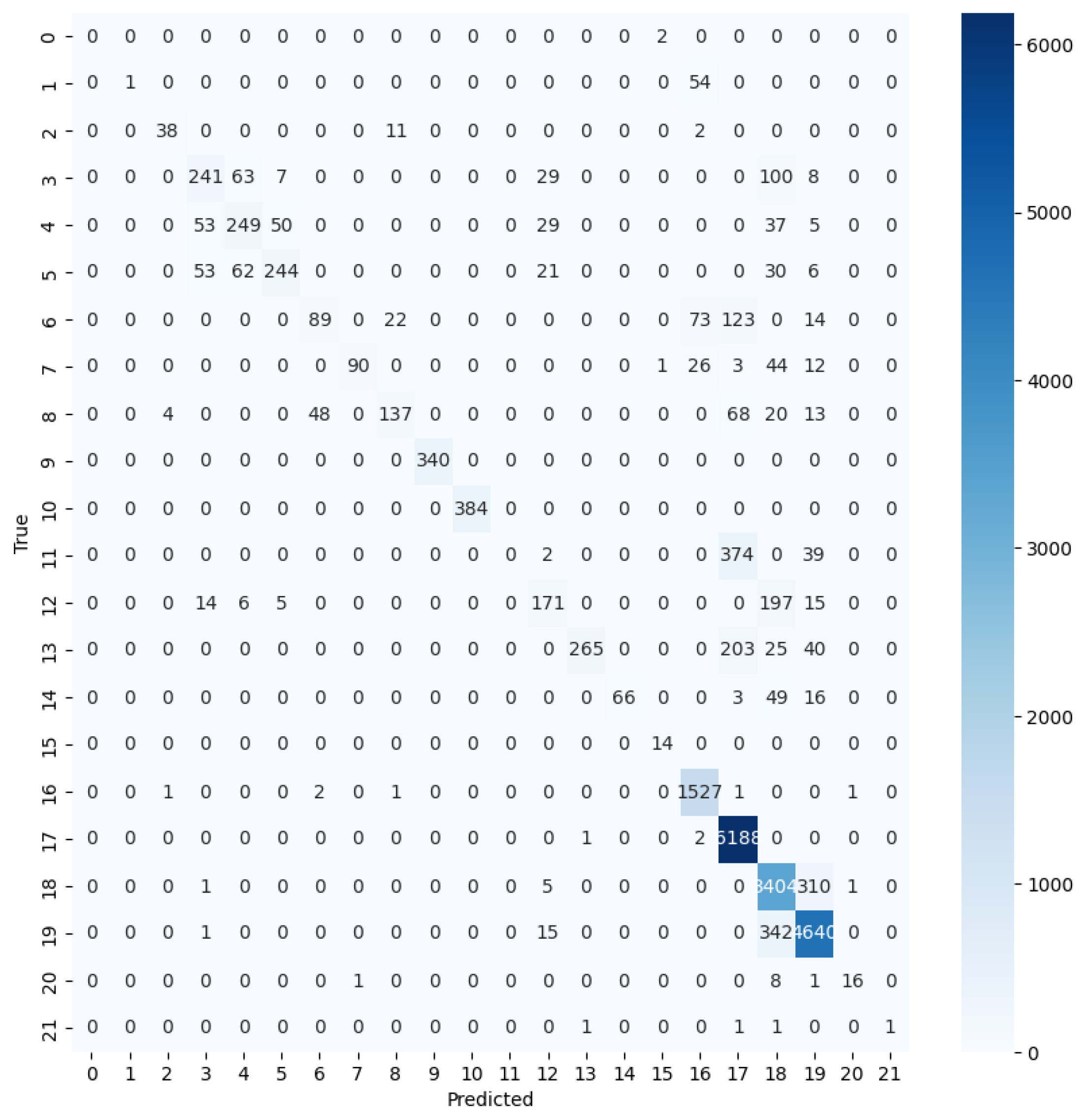

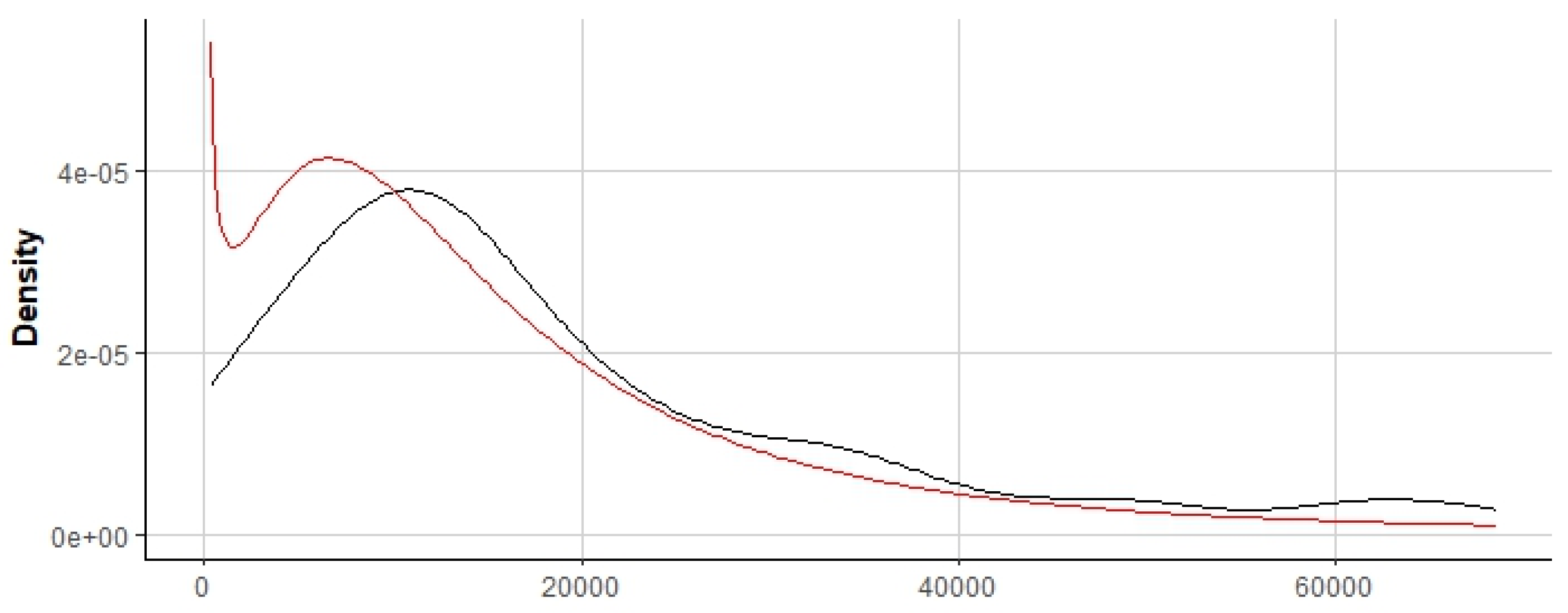

4.6. Prediction of Loan Status

| Case ID | Throughput | W.R | Amount | Activities | Rework | ES.R | Final Resource | Avg_Wait | L.S |

| 173694 | 1.000000e+00 | 10 | 7000 | 59 | 30.0 | 10609.0 | 10912.0 | 14.287189 | 2 |

| 179591 | 6.664793e-01 | 16 | 20000 | 92 | 70.0 | 10861.0 | 112.0 | 105.390192 | 2 |

| 188485 | 6.392675e-01 | 14 | 7000 | 84 | 53.0 | 10861.0 | 112.0 | 15.379321 | 2 |

| 189805 | 6.258252e-01 | 18 | 25000 | 92 | 55.0 | 10609.0 | 10629.0 | 22.020927 | 2 |

| 183405 | 6.141806e-01 | 23 | 200000 | 141 | 118.0 | 10138.0 | 10889.0 | 20.202247 | 2 |

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

| ANN | 85% | 83% | 84% | 83% |

| KNN | 82% | 77% | 78% | 77% |

| GB | 91% | 91% | 91% | 91% |

4.7. Prediction of the Next Activity

| Class | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

| Accept | 89% | 99% | 94% | 94% |

| Declined | 94% | 86% | 90% | 90% |

| Canceled | 91% | 89% | 90% | 90% |

| Case id | Variant |

| 173688 | abcssdkelmtstttttnutugfohu |

| 173691 | abcssssdeklmtstttkplmtttttnutuuuuuofghu |

| 173694 | abcssssssssdeklmtstkplmttttttttttkplmtttttttttt... |

| 173697 | abj |

| 173700 | abj |

| 214364 | abcssssdeklmtstkpImtttttttnut |

| 214367 | abj |

| 214370 | abrrjr |

| 214373 | abrrcsrsdkelmtstt |

| 214376 | abrrjr |

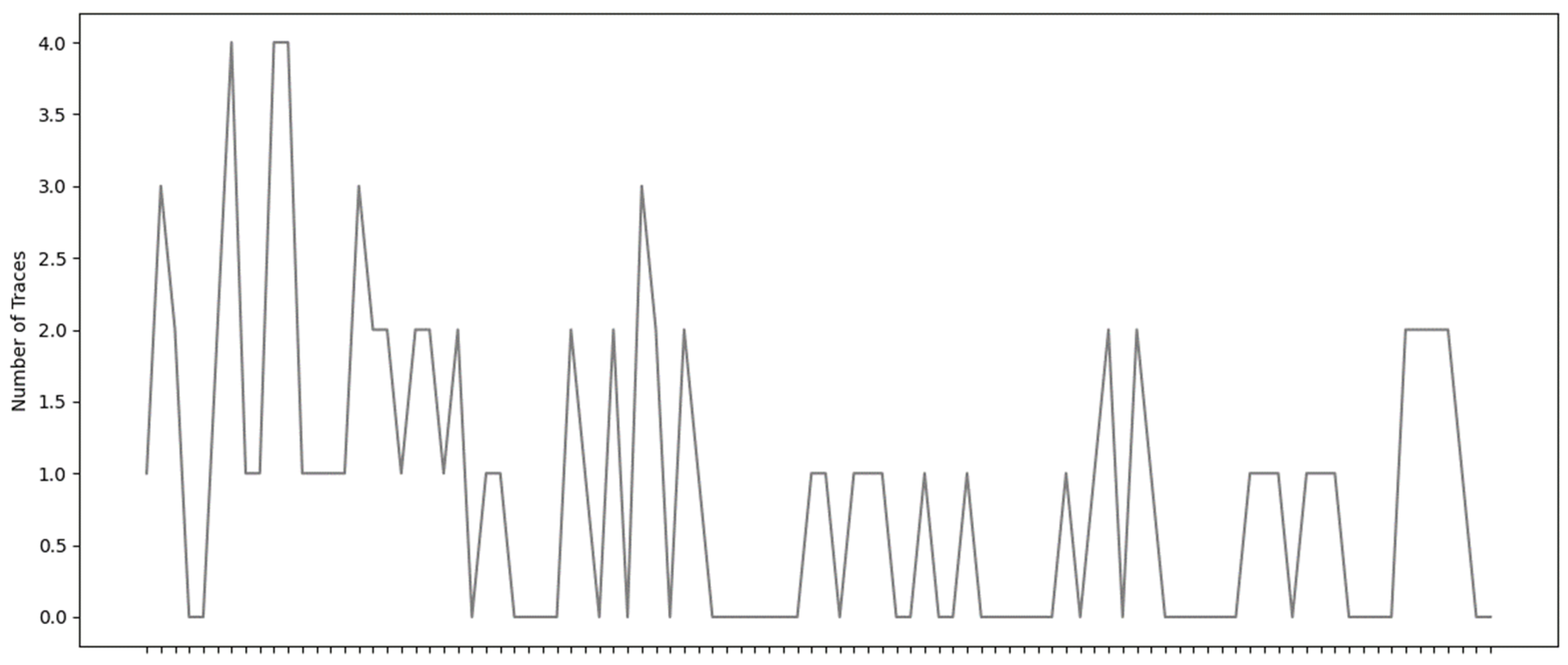

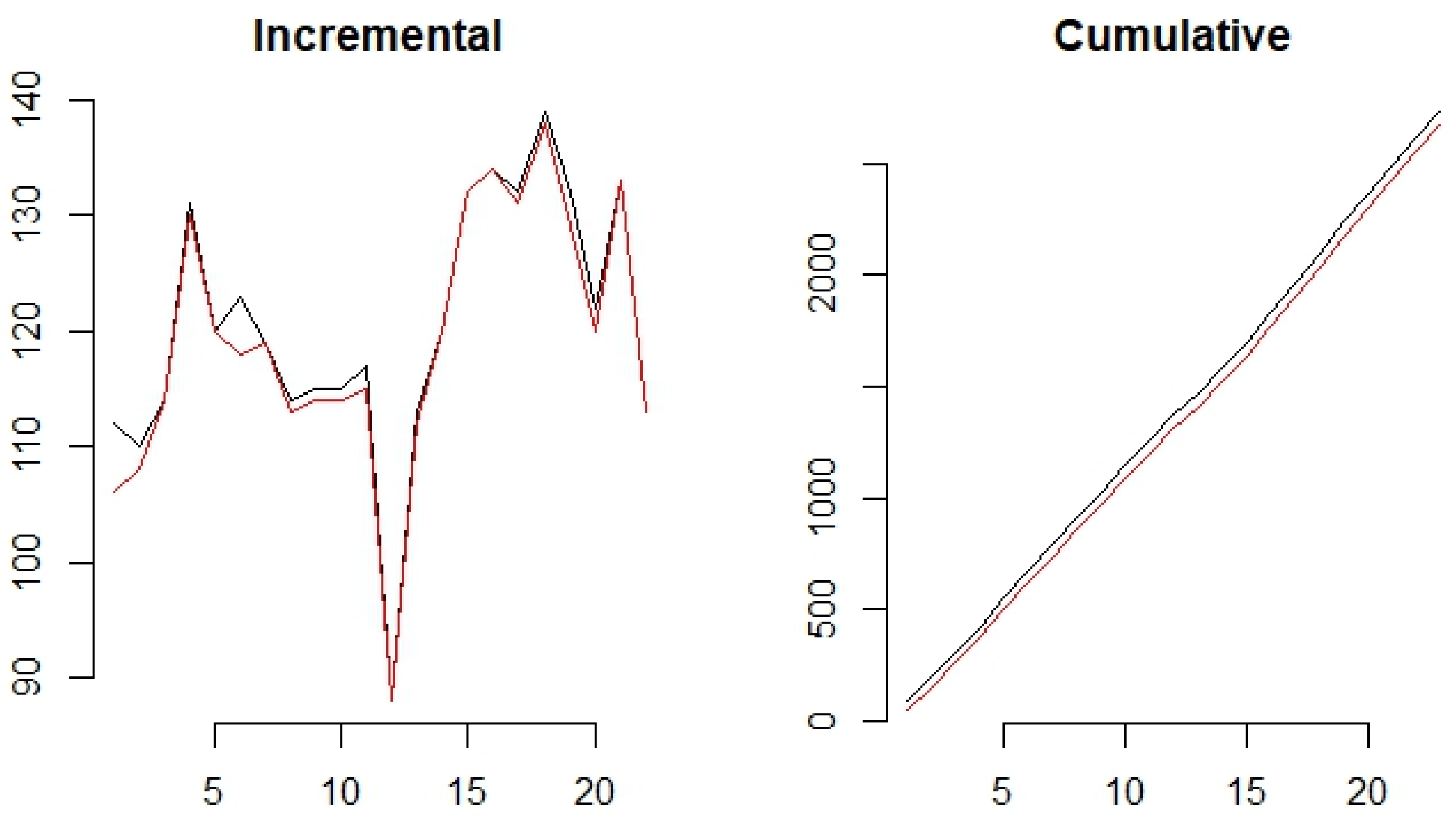

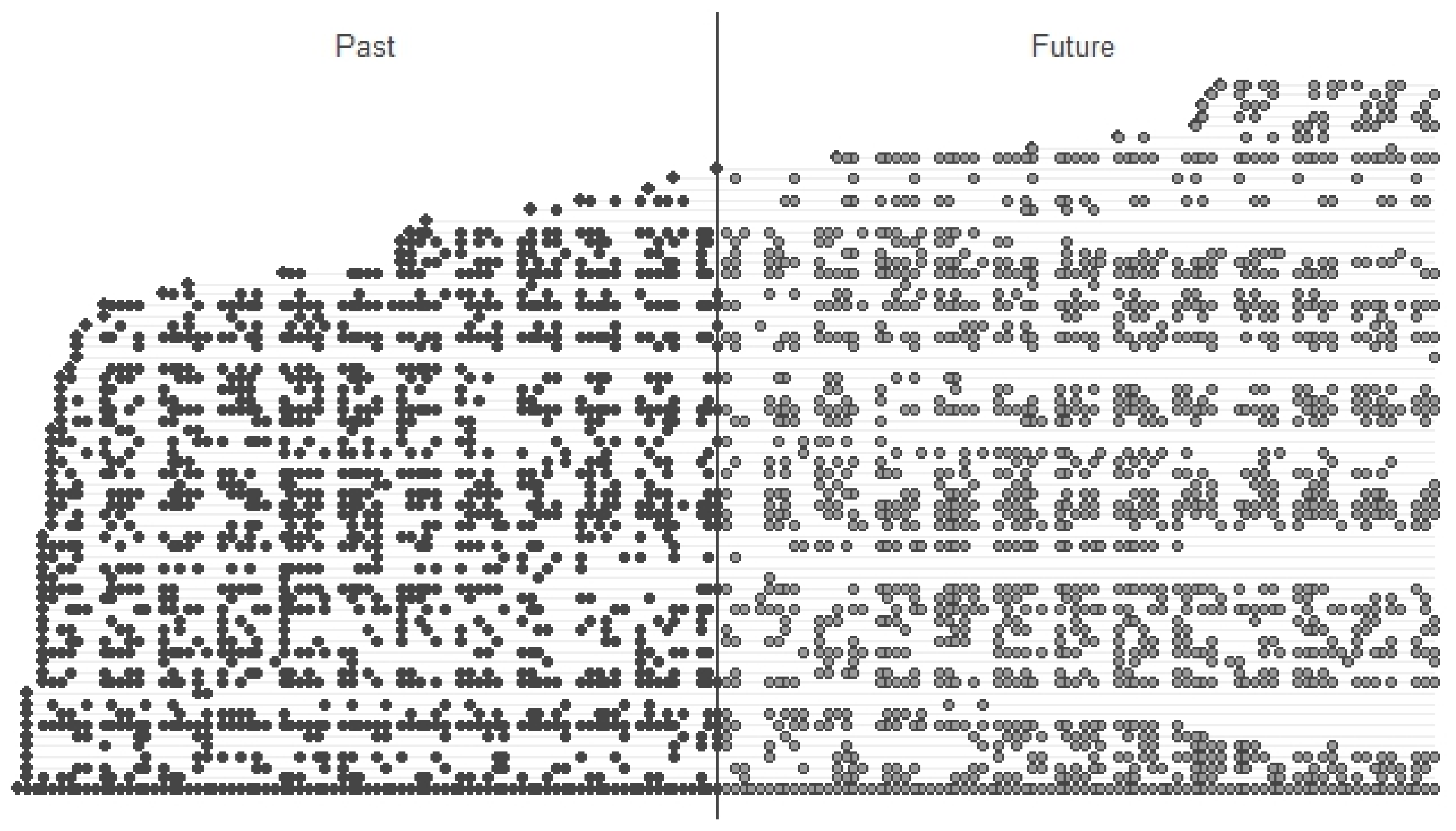

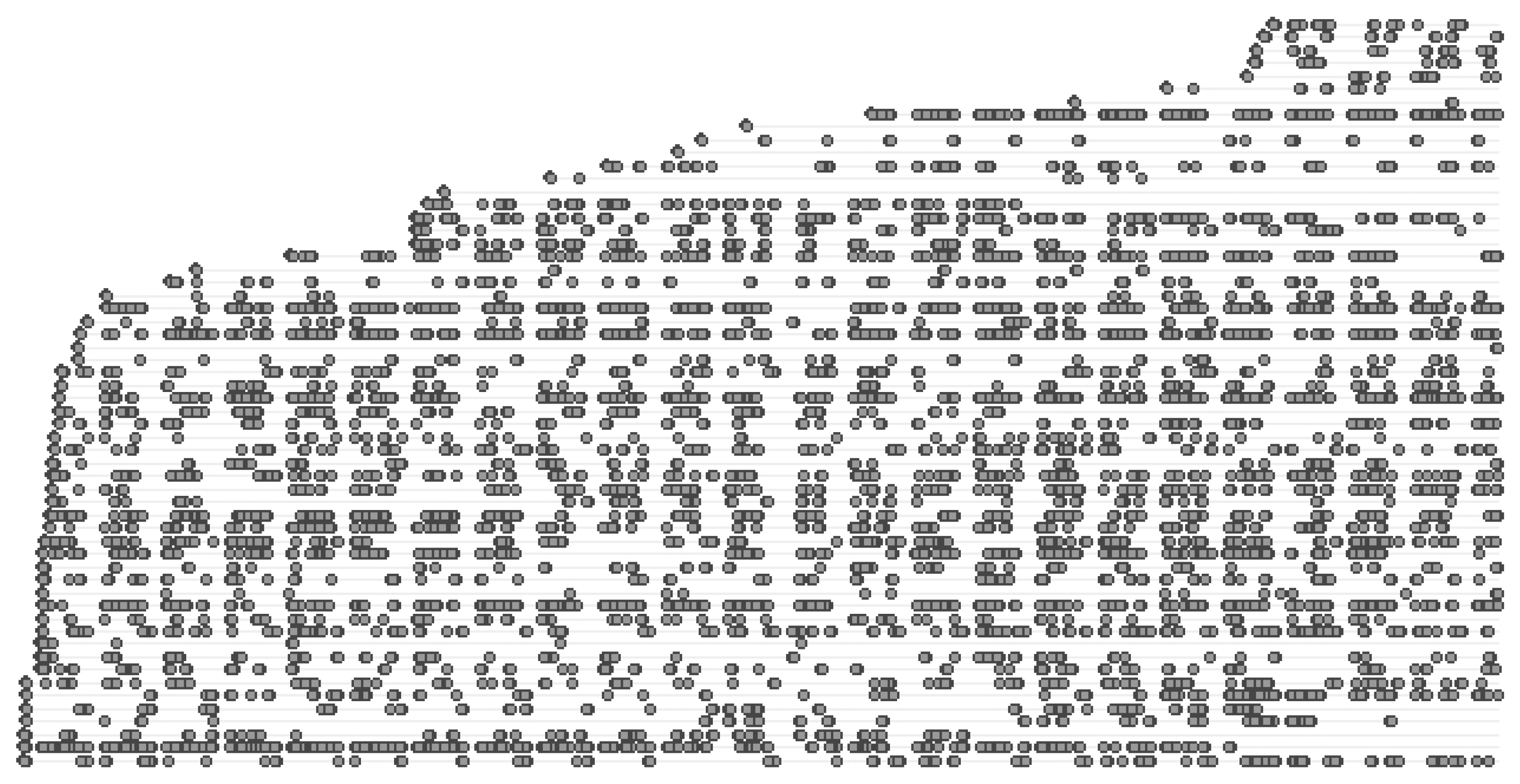

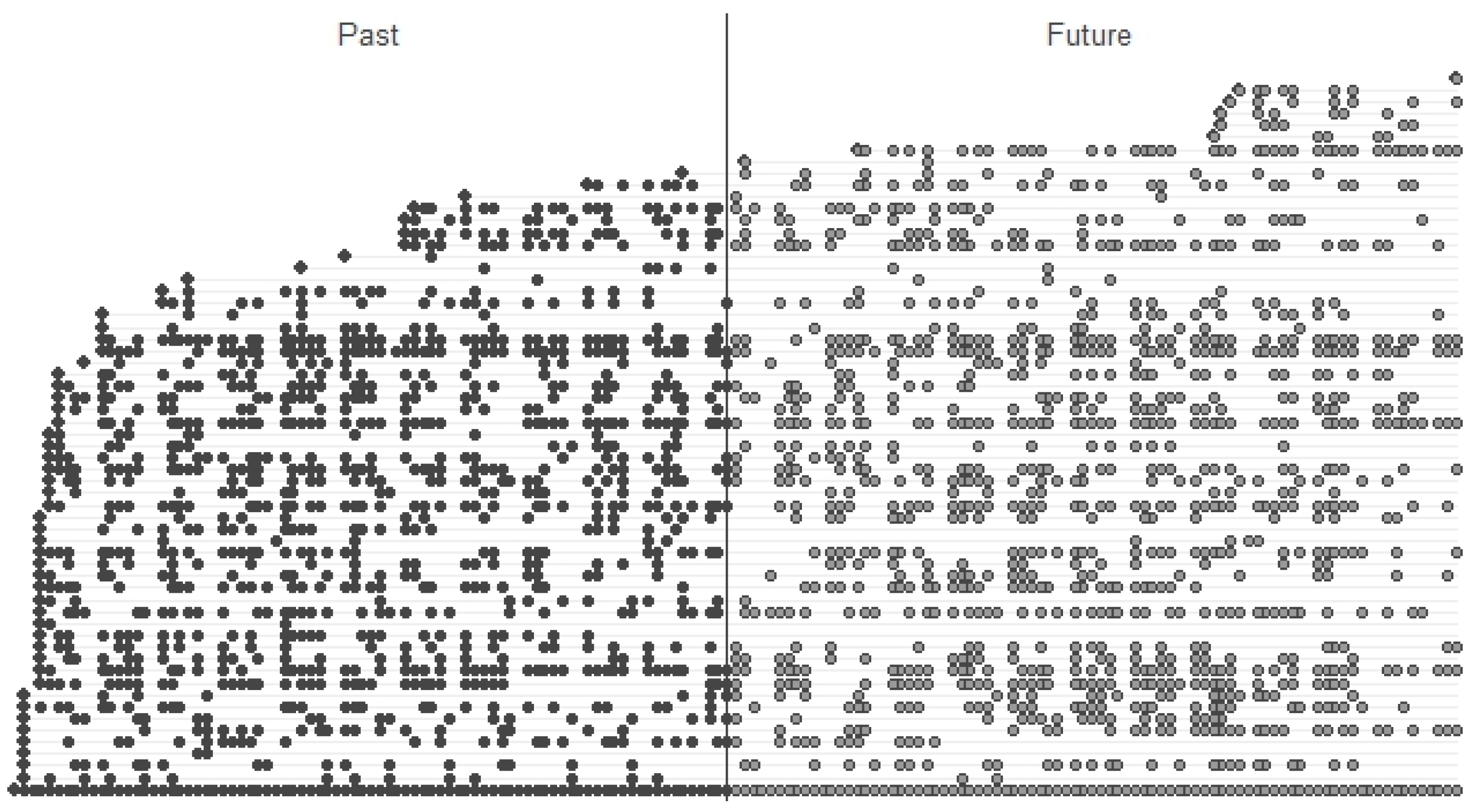

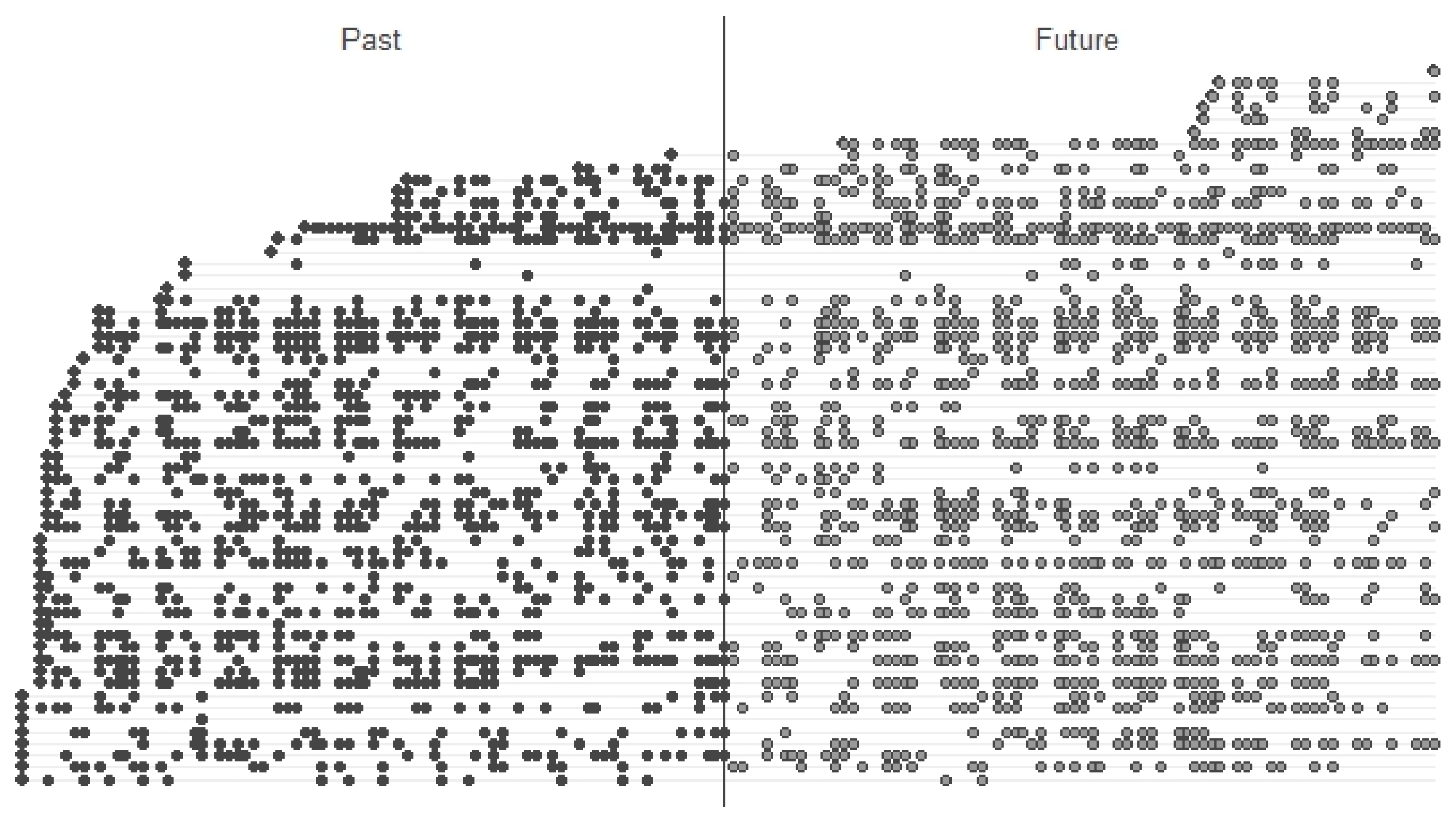

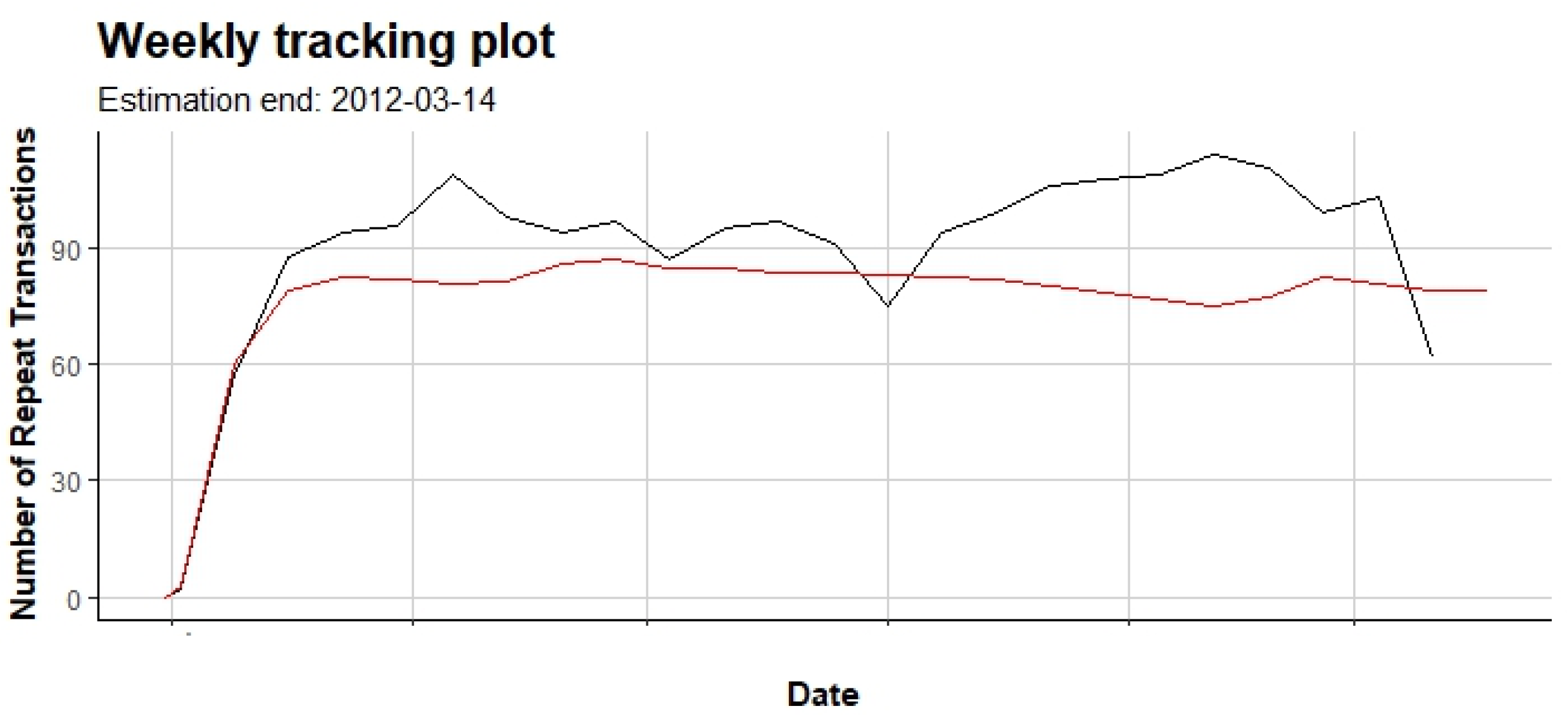

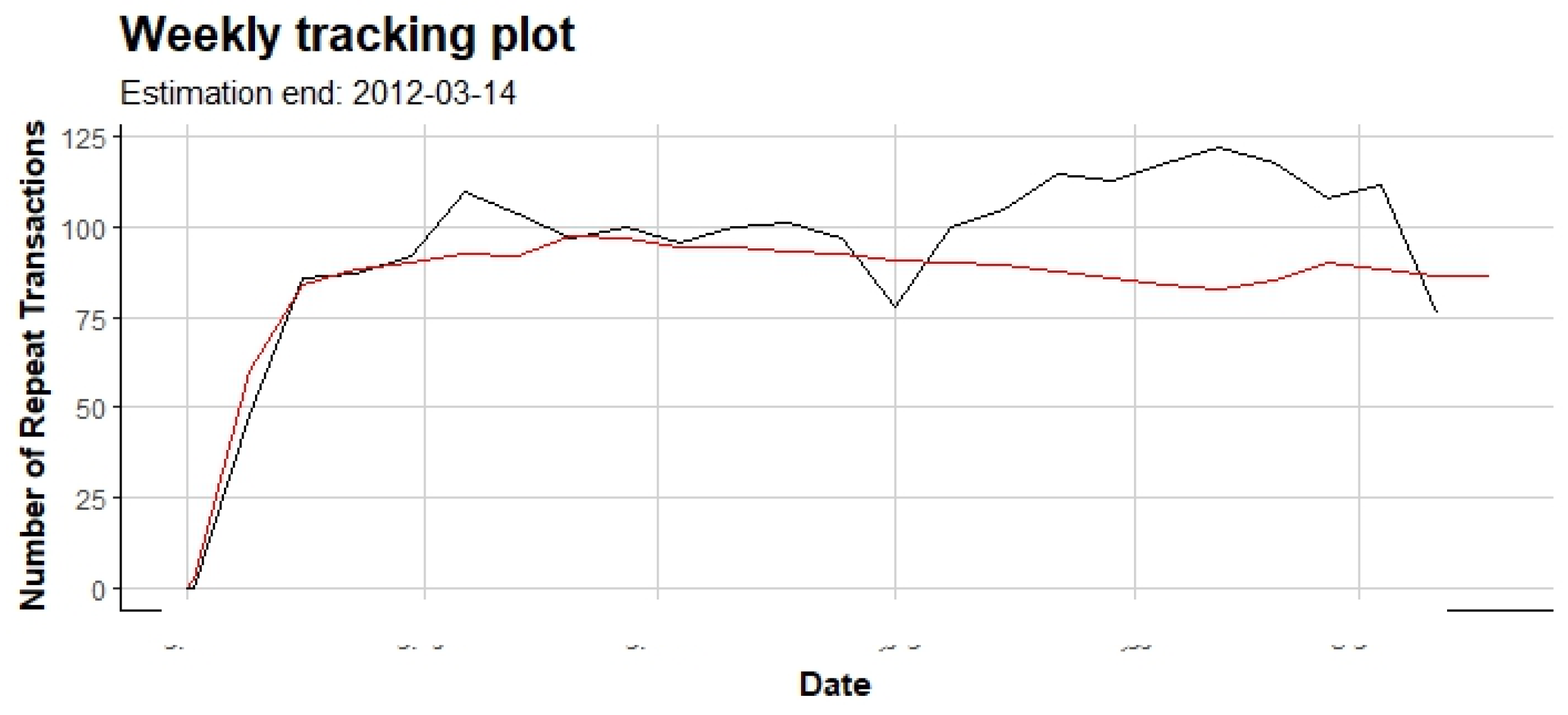

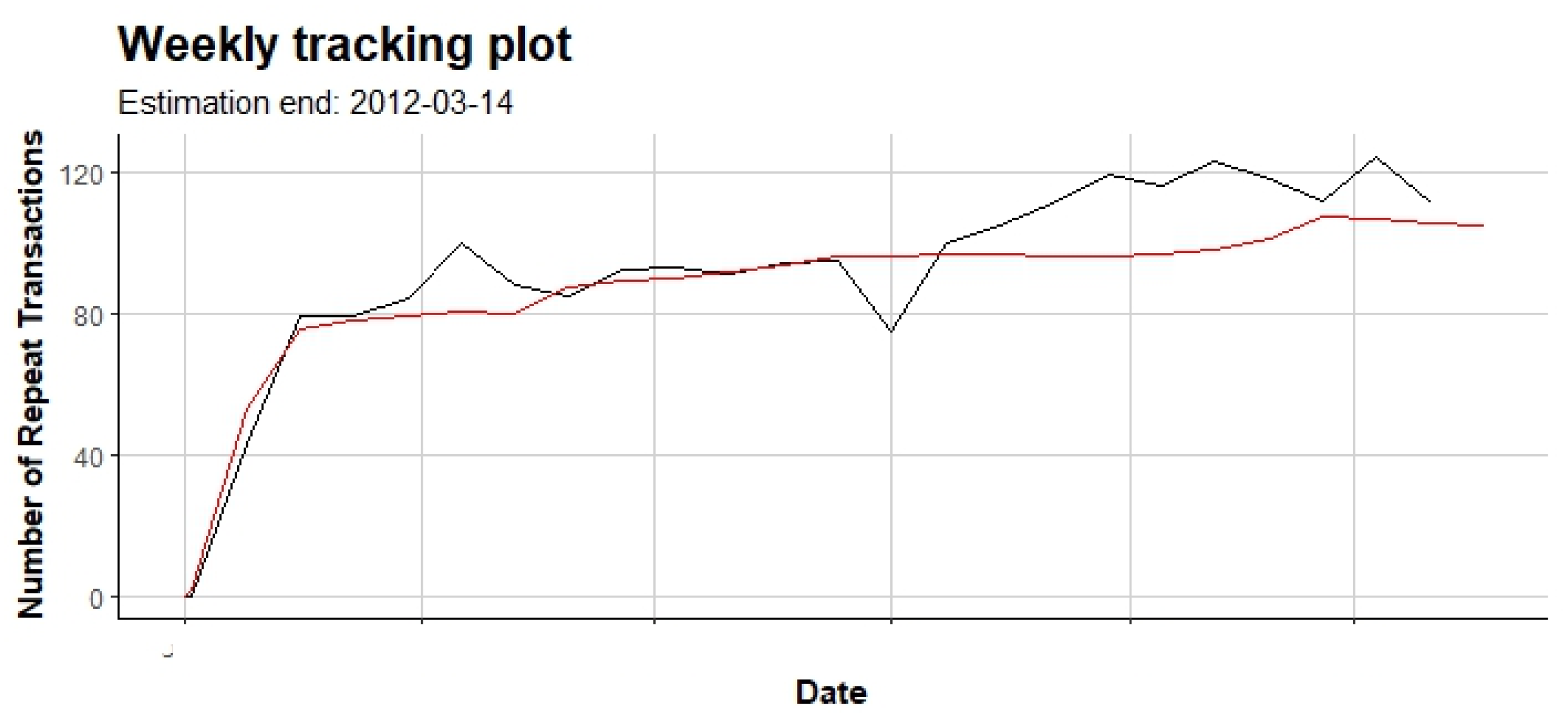

4.8. Behavior Analysis

4.8.1. Behavior of Resources Involved in the Loan Process

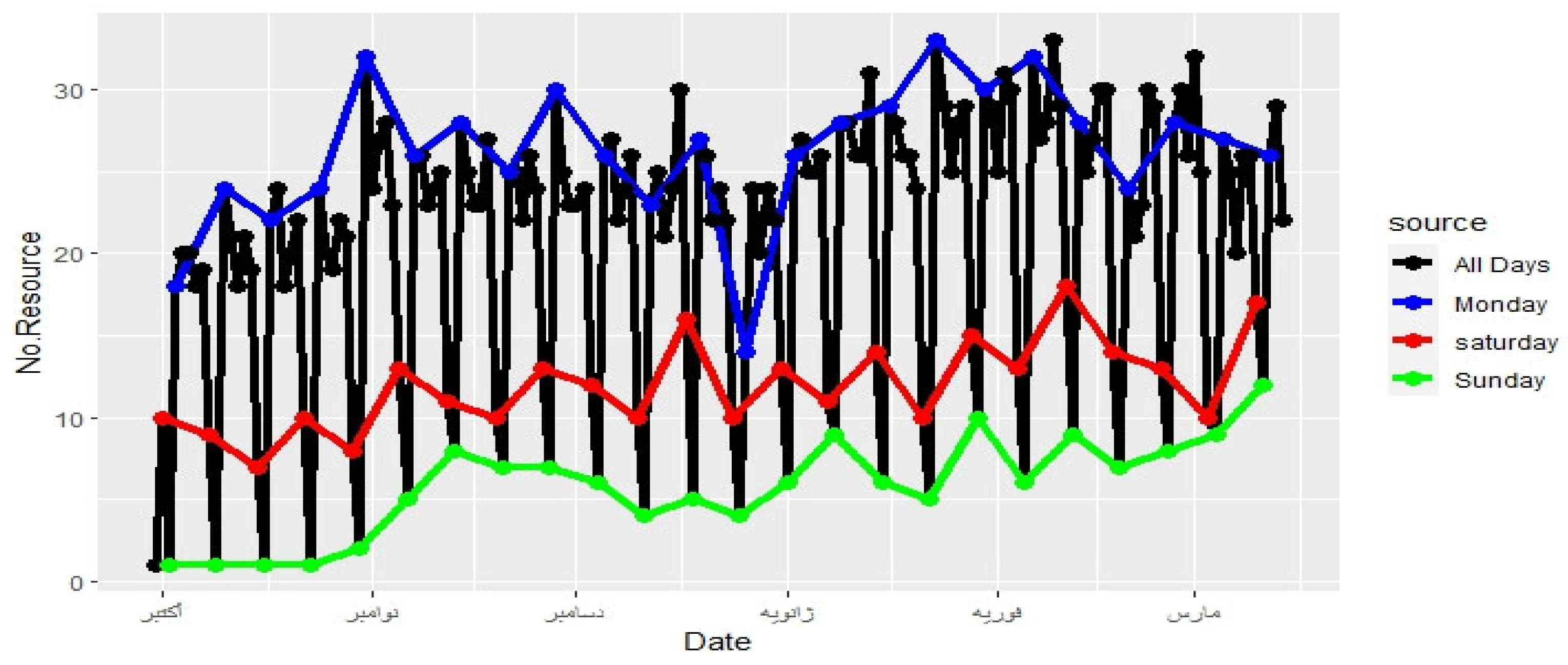

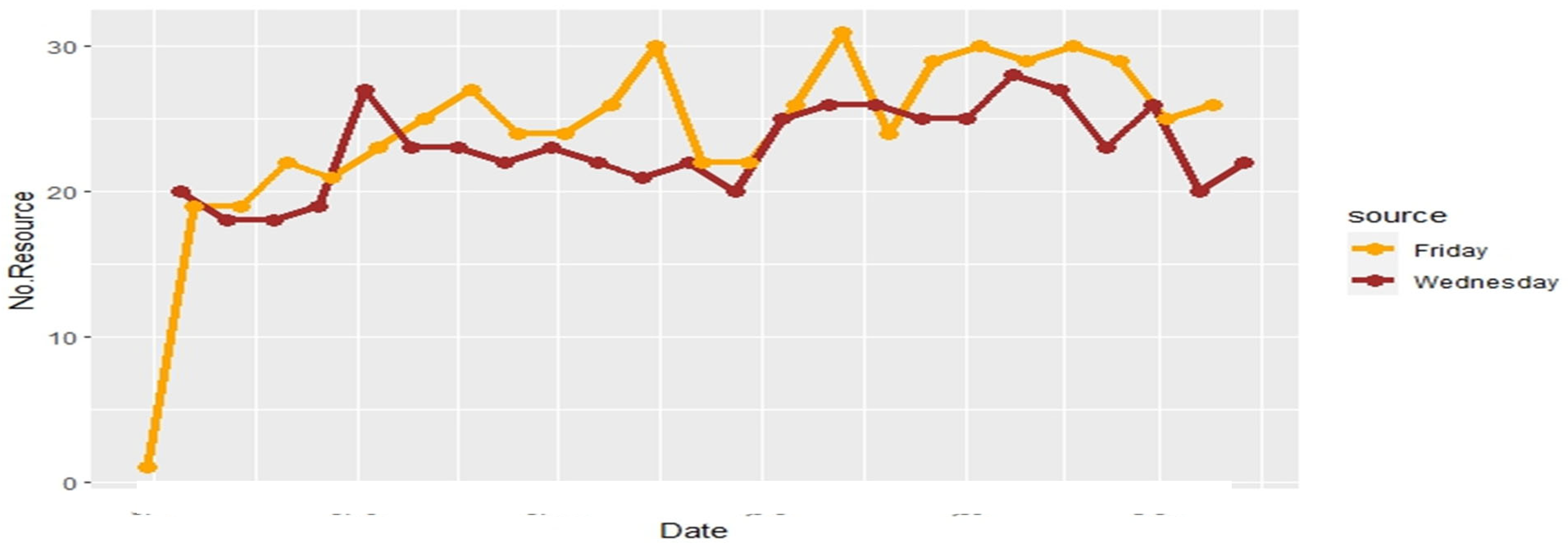

4.8.2. Activity of Resources Over the Time Horizon

4.8.3. Prediction of Resource Behavior

- What is the likelihood of each type of activity being performed by the resource in the future?

- How many activities are expected to be performed in the future?

- How much time will be spent on activities in the future? (This is only done for group W activities.)

- While the resource is active, the activities performed by the resource in the period t follow a Poisson distribution with a mean of λt.

- The variation in the activity rate among resources follows a gamma distribution with shape r and scale α.

- Each resource becomes inactive after each activity with probability p.

- The variation in p follows a beta distribution with shape parameters a and b.

| Model | Group | k | r | α | a | b | Log-likelihood | Measurement Error |

| BG/NBD | O | 1 | 2.210217 | 7.35683 | 16.72848 | 9991.288 | -2311.05 | 2.59% |

| A | 1 | 2.151856 | 7.570773 | 2.00E-05 | 2298.765 | -2242.51 | 10.17% | |

| W | 1 | 2.101796 | 6.779813 | 6.62E-05 | 703.1266 | -2166.4 | 4.47% | |

| BG/CNBD-k | O | 2 | 2.082449 | 3.414529 | 27.25052 | 9996.939 | -2190.8 | 2.25% |

| A | 2 | 2.117672 | 3.649783 | 1.88E+01 | 9990.269 | -2117.17 | 16.91% | |

| W | 2 | 1.940769 | 3.109838 | 3.26E-05 | 781.9663 | -2028.28 | 4.47% | |

| MBG/NBD | O | 1 | 2.205368 | 7.338904 | 15.70053 | 9993.16 | -2311.13 | 5.96% |

| A | 1 | 2.151582 | 7.569427 | 2.46E-05 | 1566.838 | -2242.51 | 16.91% | |

| W | 1 | 2.103013 | 6.782676 | 2.26E-06 | 664.6548 | -2166.4 | 4.55% | |

| MBG/CNBD-k | O | 2 | 2.075718 | 3.403359 | 25.45929 | 10000 | -2190.93 | 6.22% |

| A | 2 | 2.136701 | 3.678407 | 1.84E+01 | 10000 | -2117.19 | 16.91% | |

| W | 2 | 1.940785 | 3.110092 | 4.30E-06 | 61.46382 | -2028.28 | 4.55% | |

| Pareto/NBD | O | 1 | 2.147124 | 6.959706 | 0.013459 | 11.27909 | -2312.25 | 9.50% |

| A | 1 | 2.15245 | 7.570375 | 3.43E-06 | 455.8619 | -2242.51 | 16.91% | |

| W | 1 | 2.101516 | 6.780728 | 2.36E-06 | 628.723 | -2166.4 | 4.55% |

| Activity | Selected Model | Error Percentage | |

| O | BG/CNBD-k | 2.59 | |

| A | BG/NBD | 10.17 | |

| W | MBG/NBD | 4.55 |

5. Conclusions

| 1 | Data Envelopment Analysis |

References

- Abe, M. Counting Your Customers One by One: A Hierarchical Bayes Extension to the Pareto/NBD Model. Marketing Science 2009, 28(3), 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriansyah, A.; van Dongen, B. F.; van der Aalst, W. M. P.; Andrews, R. Process Discovery Using Event Logs: A Literature Survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2011, 44(1), 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, N. S. An introduction to kernel and nearest-neighbor nonparametric regression. The American Statistician 1992, 46(3), 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batislam, E.; Denizel, M.; Filiztekin, A. Empirical validation and comparison of models for customer base analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2007, 24(3), 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, A. D.; Wangikar, L.; Akbar, S. M. K. Process mining-driven optimization of a consumer loan approvals process; BPI Challenge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tal, A.; Nemirovski, A. Robust optimization: methodology and applications. Mathematical programming 2009, 107(1-2), 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Sim, M. Robust optimization: formulation, implementation, and applications. In Handbook of data-based decision making in education; Springer; Boston, MA, 2004; pp. 431–454. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, R. J. C.; van der Aalst, W. M. Process mining applied to the BPI challenge 2012: Divide and conquer while discerning resources. Business Process Management Workshops: BPM 2012 International Workshops, Tallinn, Estonia; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, J. C.; Reijers, H. A.; van Dongen, B. F. Resolving deviant behavior in process models; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, J.; van Dongen, B. F.; Solti, A.; Weidlich, M. Automated Discovery of Process Models from Event Logs: Review and Benchmark. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS) 2018, 9(1), 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W. W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. European journal of operational research 1978, 2(6), 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W. W.; Golany, B.; Seiford, L.; Stutz, J. Foundations of data envelopment analysis for Pareto-Koopmans efficient empirical production functions. Journal of Econometrics 1985, 30(1-2), 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W. W.; Seiford, L.; Stutz, J. Invariant multiplicative efficiency and piecewise Cobb-Douglas envelopments. Operations Research Letters 1983, 2(3), 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; ACM, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W. W.; Seiford, L. M.; Tone, K. Data envelopment analysis: a comprehensive text with models, applications, references and DEA-solver software; Springer, 2007; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T. M.; Hart, P. E. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1967, 13(1), 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, M.; La Rosa, M.; Mendling, J.; Reijers, H. A. Fundamentals of Business Process Management; Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, A. S. C. The pattern of consumer purchases. Applied Statistics 1959, 8(1), 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fix, E.; Hodges, J. L. Discriminatory Analysis. Nonparametric Discrimination: Consistency Properties. Report Number 4, Project Number 21-49-004; USAF School of Aviation Medicine; Randolph Field, Texas, 1951.

- Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Annals of Statistics 2001, 29(5), 1189–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, A.; Mohamed, A.; Hinton, G. Speech recognition with deep recurrent neural networks. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing; IEEE, 2013; pp. 6645–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M. What is Business Process Management? In Handbook on Business Process Management 1; Springer, 2010; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Kamber, M. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques; Elsevier, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, P. Business Process Change: A Business Process Management Guide for Managers and Process Professionals; Morgan Kaufmann, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9(8), 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, D.; Wagner, M. Customer base analysis using stochastic modeling: An application to a large retailer. OR Spectrum 2007, 29(3), 421–433. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521(7553), 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemans, S. J. J.; Fahland, D.; van der Aalst, W. M. P.; van Dongen, B. F. Efficiently Mining Generalized Association Rules. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2013, 25(2), 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, S. C.; Tsang, S. O.; Ng, W.-L.; Wu, Y. A robust optimization model for multi-site production planning problem in an uncertain environment. European journal of operational research 2007, 181(1), 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, L.; Lee, S. C. A tree-based approach for analyzing collaborative business processes, 2014.

- Ma, S.; Liu, J. S. Hierarchical Bayes models for “buy till you die” data. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 2007, 25(4), 536–545. [Google Scholar]

- Maruster, L.; van der Aalst, W. M. P. Real-life event log selection: Method and case study; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey, J. M.; Vanderbei, R. J.; Zenios, S. A. Robust optimization of large-scale systems. Operations research 1995, 43(2), 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, M.; Reutterer, T. Incorporating regularity in transaction timings into customer base analysis. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 30, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Reutterer, T.; Platzer, M.; Schröder, T. Extending Pareto/NBD for customer base analysis using continuous and discrete covariates. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2020, 48(1), 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D. E.; Hinton, G. E.; Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323(6088), 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O.; Le, Q. V. Sequence to sequence learning with neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2014; pp. 3104–3112. [Google Scholar]

- Tax, N.; Verenich, I.; La Rosa, M.; Dumas, M. Predictive business process monitoring with LSTM neural networks. In International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering; Springer, Cham, 2017; pp. 477–492. [Google Scholar]

- Teinemaa, I.; Dumas, M.; La Rosa, M. Mining Declarative Process Models from Event Logs Containing Noise. BPM Workshops; 2012; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Thanassoulis, E. Introduction to the Theory and Application of Data Envelopment Analysis: A Foundation Text with Integrated Software; Springer, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen, B. F.; de Medeiros, A. K. A.; Verbeek, H. M. W.; Weijters, A. J. M. M.; van der Aalst, W. M. P. The ProM Framework: A New Era in Process Mining Tool Support. In Applications and Theory of Petri Nets; 2005; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Aalst, W. M. P.; Reijers, H. A.; Song, M. Discovering Social Networks from Event Logs. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 2005, 14(6), 549–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Aalst, W. M. P. Process Mining: Discovery, Conformance and Enhancement of Business Processes; Springer, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Aalst, W. M. P.; Weijters, A. J. M. M.; Maruster, L. Workflow Mining: Discovering Process Models from Event Logs. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2004, 16(9), 1128–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Aalst, W. M. P.; Weijters, A. J. M. M.; Maruster, L. The Business Process Intelligence Challenge 2012: Discovering Bottlenecks and Deviations in Processes; Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Aalst, W.; van der Aalst, W. Data science in action; Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Activity Type | Notes | Activity Name | Activity Description |

| A | This refers to the loan’s states. A customer requests a loan, and Bank users and resources follow the activities to complete the process. | A_SUBMITTED | Initial request submission |

| The customer submits part of the required information for the loan request. | A_PARTLYSUBMITTED | Partial initial request submission | |

| The loan is pre-accepted but requires additional information. | A_PREACCEPTED | Pre-accepted | |

| The loan is accepted and under review for completeness. | A_ACCEPTED | Accepted | |

| The loan is finalized for completion. | A_FINALIZED | Finalized | |

| The loan application has been reviewed and approved. | A_APPROVED | Approved | |

| The approved loan has been registered in the system. | A_REGISTERED | Registered | |

| The loan account has been activated and is ready for use. | A_ACTIVATED | Activated | |

| The status of unsuccessful program termination indicates that the loan application was either canceled by the customer or declined by the bank. | A_CANCELLED/A_DECLINED | Canceled/Declined | |

| O | Refers to proposed states that have been communicated to the customer. | O_SELECTED | Selected for receiving the loan |

| The bank has prepared a loan proposal and sent it to the customer. | O_PREPARED | Proposal prepared and sent to the applicant | |

| The loan proposal has been sent to the customer. | O_SENT | Proposal sent | |

| The customer has responded to the loan proposal. | O_SENT BACK | Proposal response received from the applicant | |

| The customer has accepted the loan proposal. | O_ACCEPTED | Approved | |

| The loan proposal was canceled before approval. | O_CANCELLED | Cancelled | |

| The bank declined the loan proposal. | O_DECLINED | Declined | |

| W | This refers to states of work items occurring during the approval process. These events mainly involve manual efforts by bank resources during the approval process. Events describe efforts at different stages of the application process. Follow up on incomplete leads. | W_Afhandelen leads | Follow up on incomplete leads after proposals are sent to qualified applicants. |

| Complete requests that were previously pre-accepted. | W_Completeren aanvraag | Complete previously accepted requests. | |

| Follow up with applicants after proposals have been sent to them to ensure they have all the necessary information and to answer any questions. | W_Nabellen offers | Follow up after sending proposals to qualified applicants | |

| Evaluate the loan application for completeness and accuracy. | W_Valideren aanvraag | Loan evaluation | |

| Search for and collect missing information or documents needed to complete the loan application evaluation. | W_Nabellen incomplete dossiers | Search for additional information during the evaluation stage. | |

| Review and investigate loan applications flagged for potential fraud. | W_Beoordelen fraude | Review suspected fraud cases. | |

| Make amendments to the terms and conditions of approved loan contracts as needed. | W_Wijzigen contractgegevens | Amend approved contracts |

| Activity | Missing start | Missing end | ||

| Variant | Case | Variant | Case | |

| W_Afhandelen leads | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| W_Beoordelen fraude | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| W_Completeren aanvraag | 104 | 455 | 0 | 0 |

| W_Nabellen incomplete dossiers | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| W_Nabellen offertes | 454 | 571 | 1 | 1 |

| W_Valideren aanvraag | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Step | Description |

| SCHEDULE | Indicates that a work item is scheduled to occur in the future |

| START | Indicates the opening/start of a work item |

| COMPLETE | Indicates the end/conclusion of a work item |

| Requested Amount | Cases | A_APPROVED | A_DECLINED | A_CANCELLED |

| 0 - 9999 | 6095 | 771 (12.65%) | 4197 (68.86%) | 1127 (18.50%) |

| 10000 - 19999 | 3627 | 808 (22.28%) | 1928 (53.16%) | 891 (24.57%) |

| 20000 - 29999 | 1593 | 389 (24.42%) | 776 (48.71%) | 428 (26.87%) |

| 30000 - 39999 | 665 | 164 (24.66%) | 324 (48.72%) | 177 (26.62%) |

| 40000 - 49999 | 296 | 62 (20.95%) | 158 (53.38%) | 76 (25.68%) |

| 50000 - 59999 | 337 | 48 (14.24%) | 206 (61.13%) | 83 (24.63%) |

| 60000 - 100000 | 75 | 4 (5.4%) | 46 (61.34%) | 25 (33.26%) |

| Resource | Total Working Time (h) | Total Working Day |

| 112 | 3101.37 | 167 |

| 10972 | 1002.43 | 104 |

| 11169 | 987.62 | 85 |

| 10932 | 960.61 | 69 |

| 10609 | 838.98 | 101 |

| 10138 | 720.14 | 100 |

| 10809 | 585.42 | 101 |

| 11203 | 492.03 | 74 |

| Resource | A_CANCELLED | Resource | A_APPROVED | Resource | A_DECLINED |

| 112 | 1004 | 112 | 3 | 112 | 3429 |

| 11203 | 108 | 10629 | 359 | 10910 | 244 |

| 11119 | 97 | 10609 | 335 | 11169 | 238 |

| 11180 | 95 | 10809 | 271 | 10609 | 206 |

| 11181 | 95 | 10972 | 518 | 11189 | 172 |

| 10861 | 85 | 10138 | 681 | 10138 | 156 |

| 10913 | 82 | 10779 | 2 | 10913 | 155 |

| 10909 | 76 | 11289 | 68 | 10861 | 137 |

| 11201 | 72 | 11339 | 9 | 10982 | 133 |

| Resource | A_DECLINED | CANCELLED | A_APPROVED |

| 112 | 3429 | 1004 | 3 |

| 10779 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| 11339 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 11289 | 55 | 3 | 68 |

| 10138 | 156 | 5 | 681 |

| 10609 | 206 | 5 | 335 |

| 10809 | 87 | 1 | 271 |

| 10972 | 106 | 3 | 518 |

| Activity | Count |

| W_Valideren aanvraag | 2747 |

| W_Wijzigen contractgegevens | 4 |

| A_DECLINED | 3429 |

| W_Completeren aanvraag | 1939 |

| A_CANCELLED | 655 |

| W_Nabellen incomplete dossiers | 452 |

| W_Afhandelen leads | 2234 |

| W_Nabellen offertes | 1290 |

| W_Beoordelen fraude | 57 |

| O_CANCELLED | 279 |

| A_REGISTERED | 1 |

| Model | Average fitness | Precision | Generalization | Simplicity |

| Alpha Miner | 0.654 | 0.105 | 0.973 | 0.944 |

| Inductive Miner | 0.9887 | 0.129 | 0.947 | 0.611 |

| Heuristic Miner | 0.9888 | 0.314 | 0.954 | 0.5656 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).