Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

In a previous paper [1], we presented a very simple monitoring system. That system aimed at providing the basic information needed to set up a hydrological simulation model which would be used to explore and understand the behavior of the system and explore possible changes linked to future climates. After more than 1.5 years of observations, the gathered information was utilizable to test a 0D hydrological model. This exercise is presented here together with a comparison with a more refined, and more demanding, 2D hydrodynamic model, enlightening strengths and weaknesses. Several details are revealed in this paper showing how even a simple case needs some type of art in order to overcome the unavoidable difficulties. Surprisingly nice answers have been obtained which illuminate on the behavior of the lagoon and shed light on the key points to be improved both in monitoring and modelling. This exercise can be of help in several similar situations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

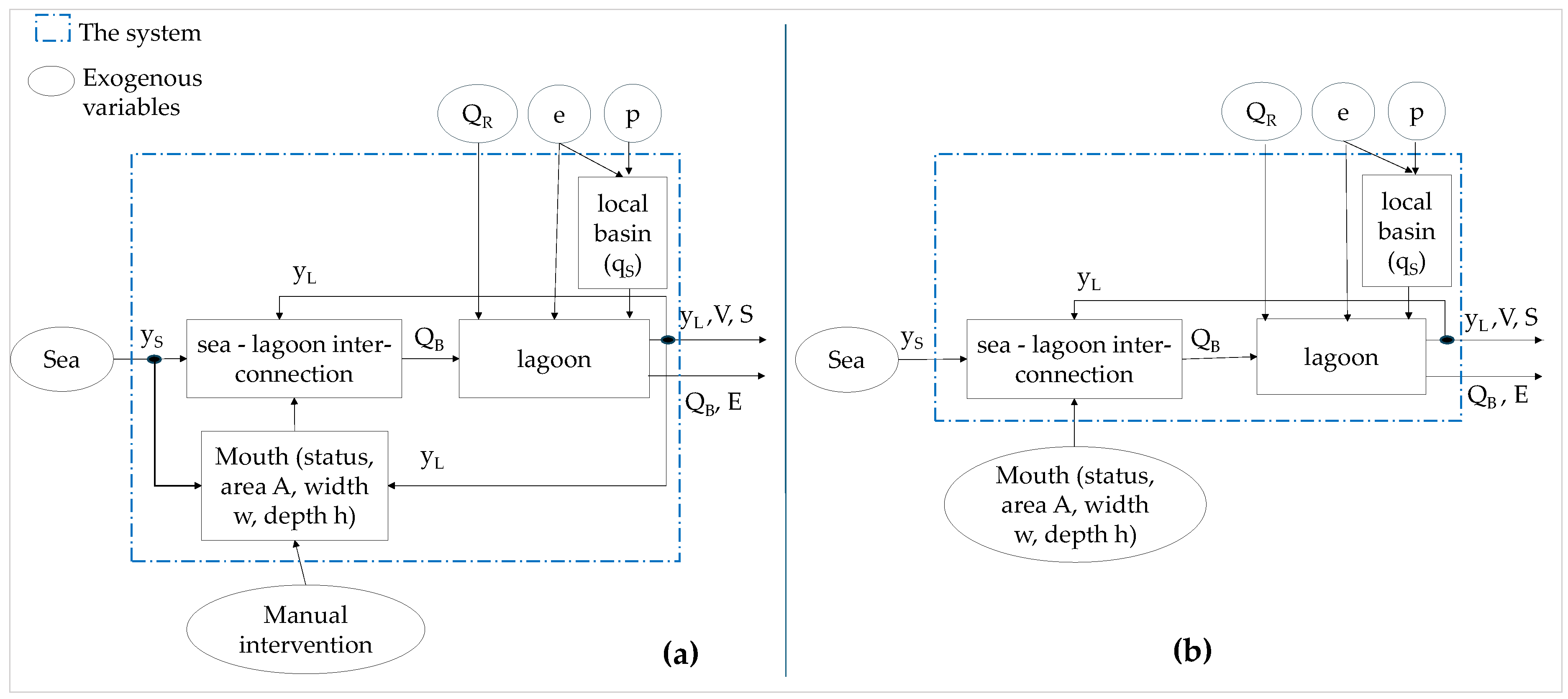

2. System Approach: Two Views of the Same System

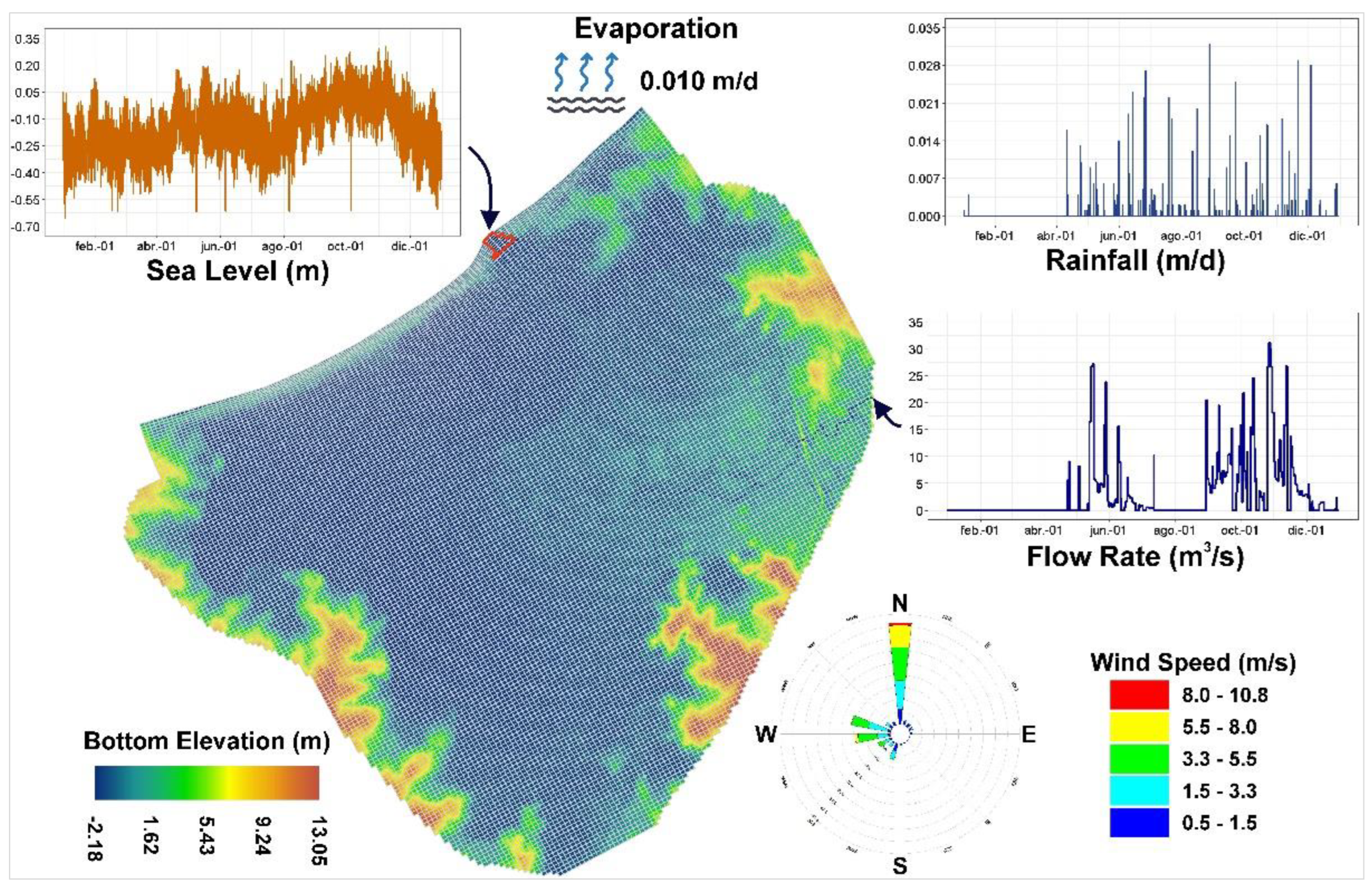

3. Elements of the Modelled System

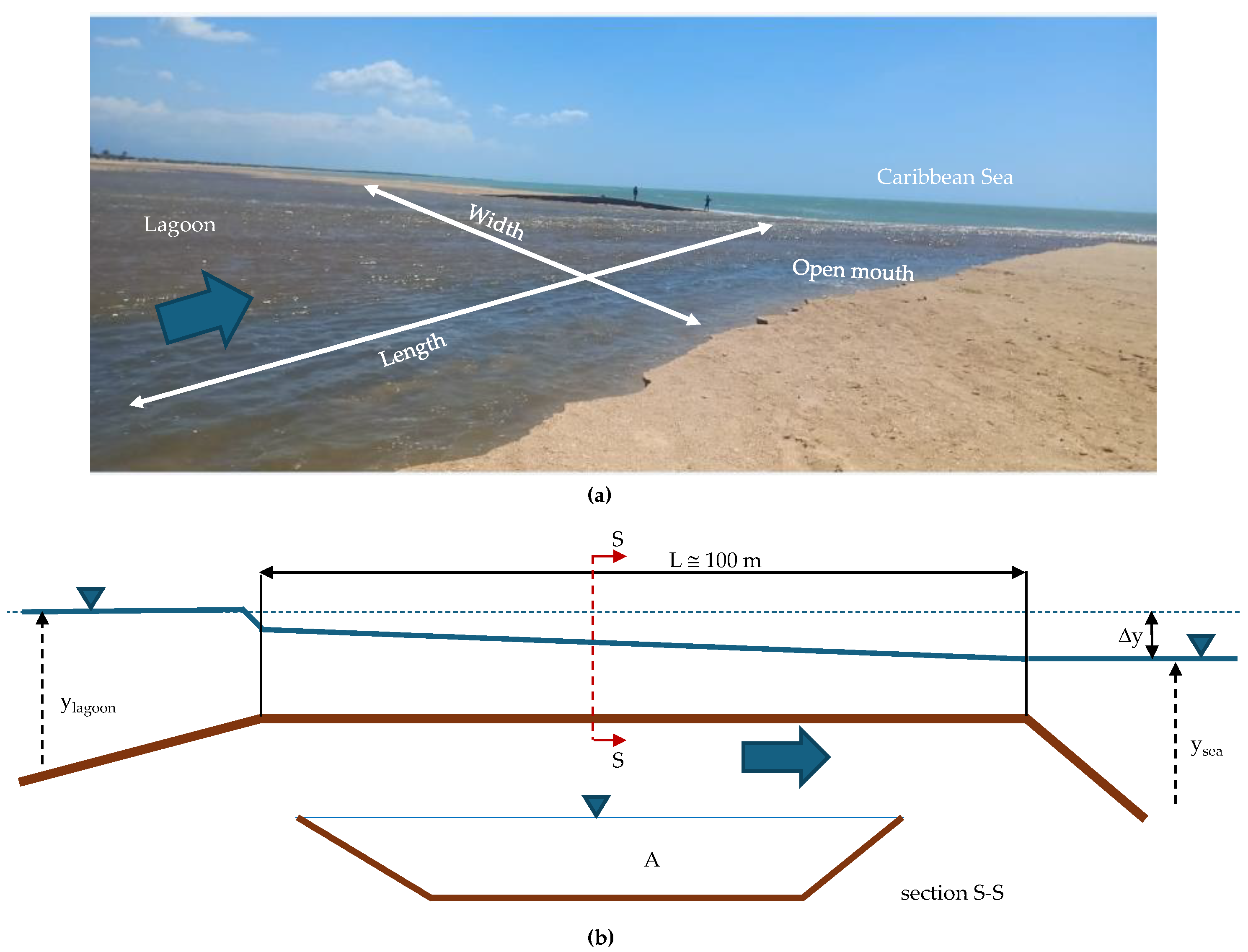

3.1. Morphometrics

3.1.1. Process

3.1.2. Validation

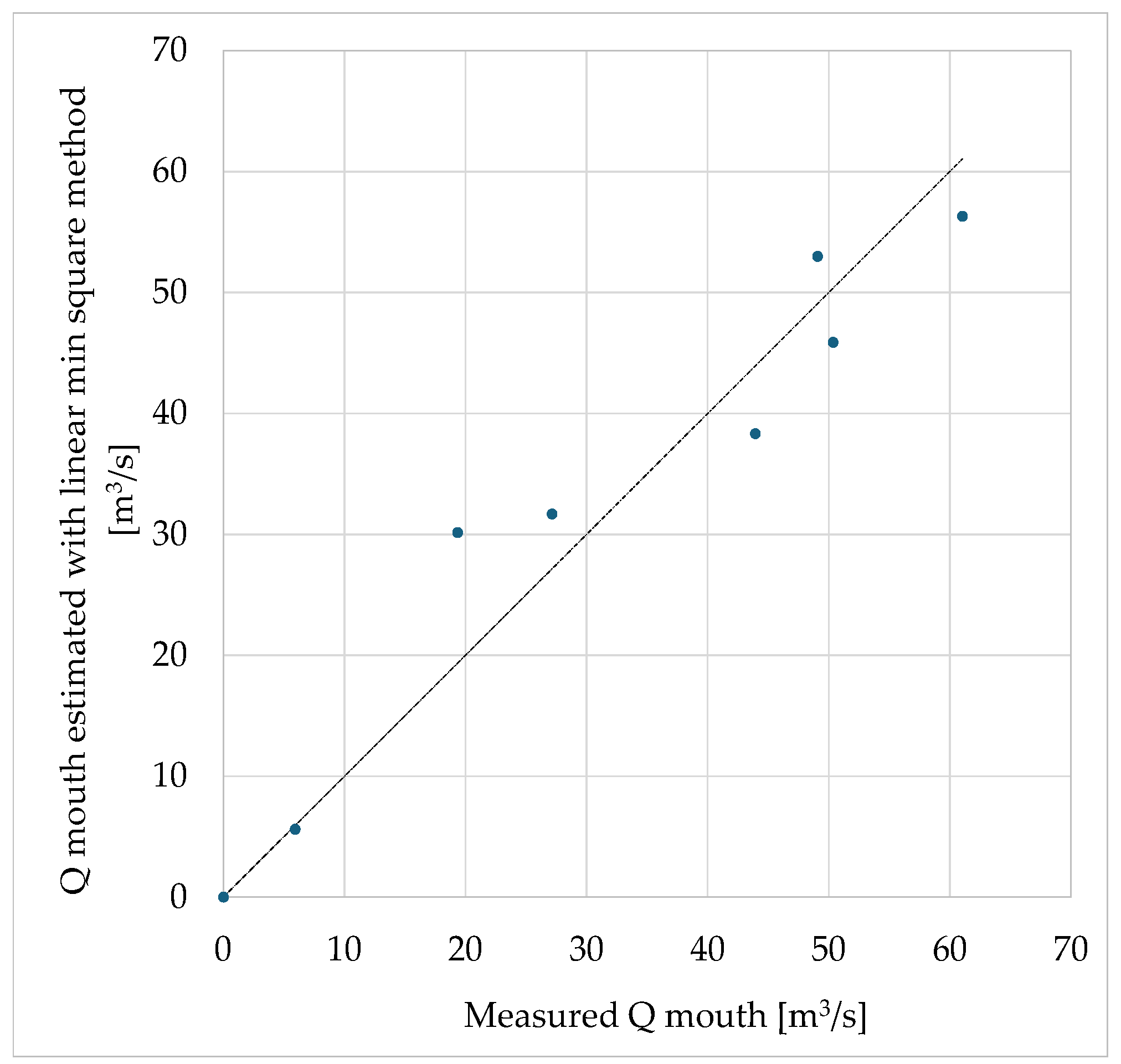

3.2. Mechanisms: Lagoon-Sea Exchange Flows

3.3. Mechanisms: Dynamics of the Mouth

3.4. Inflow from Runoff and Direct Precipitation

3.5. Evaporation

4. Modelling of the Lagoon

4.1. Characteristics

4.1.1. 0D Spatial Modelling

4.1.2. 2D Spatial Modelling

- ▪

- ▪

- One simple way to deal with this is to adopt a (topo-bathymetric) DEM including the largest mouth, and then run a number of simulations, each starting with the final state of the previous one and including a border condition with progressively a larger width on top of the DEM mouth, while the mouth is widening and vice versa when it is narrowing. A more elegant solution is to embed directly in the model code (usually not accessible) a time varying border condition.

- ▪

- This implies that the model determines automatically the exchange flows across the mouth, given the sea level and the current lagoon water level. This seems quite feasible according to the very nature of the 2D model approach: at any time, in any cell of the discretization modelling grid, a gradient is computed and a corresponding flow determined (in x,y directions).

- ▪

- Winds are crucial in the phenomena of coastal barrier overflow and favor water exchange between the lagoon and the sea (ebb and flow), so for the case at hand where winds are scarcely known, the 2D model output can be negatively affected.

- ▪

- In the 0D model we solved this by just including a very basic rule stating, essentially, that on top of a certain lagoon level (threshold), the mouth would open, while it would close below another threshold.

- ▪

- In the 2D model, the mechanisms of bed morphology change can be embedded in the “physics” of the model itself, so that it autonomously and dynamically adjusts the mouth geometry in response to changing conditions, simulating sediment transport and morphological changes [15]. Several studies on lagoon barrier overtopping events have employed 2D hydrodynamic models to reconstruct the entire process and variability of water flows, including dam formation, breach flow hydrographs, and downstream flooding. This demonstrates the models' ability to capture complex morphodynamic and hydro-sedimentological processes [10,16].

- ▪

- Obtaining however the data required by these sophisticated models (e.g., XBeach) is expensive and logistically challenging, limiting the model applicability in practical situations where data is scarce and generally unreliable [17,18]. In addition, sophisticated algorithms and robust numerical solutions [19] are required as well as specialized knowledge and experience to configure, run the model, interpret its results [14] and occasionally access to source code to perform the necessary adjustments and configurations to the computational algorithm. This level of expertise may not always be available, especially in resource-limited regions, further complicating the practical application of these models.

- ▪

- To model in particular the closure of the mouth, essential input data detailing exogenous forcing inside the lagoon as well as in the marine domain (such as tide levels, waves, solids concentration and sediment transport by marine currents) are fundamental [11,16]. Without detailed, extensive, high-quality data input, hardly obtainable in general, as well as sufficient computational resources, the feasibility and accuracy of these types of models are significantly limited.

- ▪

- Here the key issue moves on the computing and processing speed.

- ▪

- Dimensionality reduction can be a way out (as explored for instance by [20]. However, especially concerning the simulation of coastal barrier breaches, significant computational resources are required due to the need for high-resolution numerical meshes and the complexity of the physical processes involved [13]. Mesh refinement in the breach area is generally required, implying an increase in computational cost as it necessitates decreasing the time step to maintain numerical stability. This can be a limiting factor, especially in the case of long-term simulations.

- ▪

- Most probably, the answer becomes hence negative when dealing with a personal computer, while it may be positive when thinking of cloud computing [21].

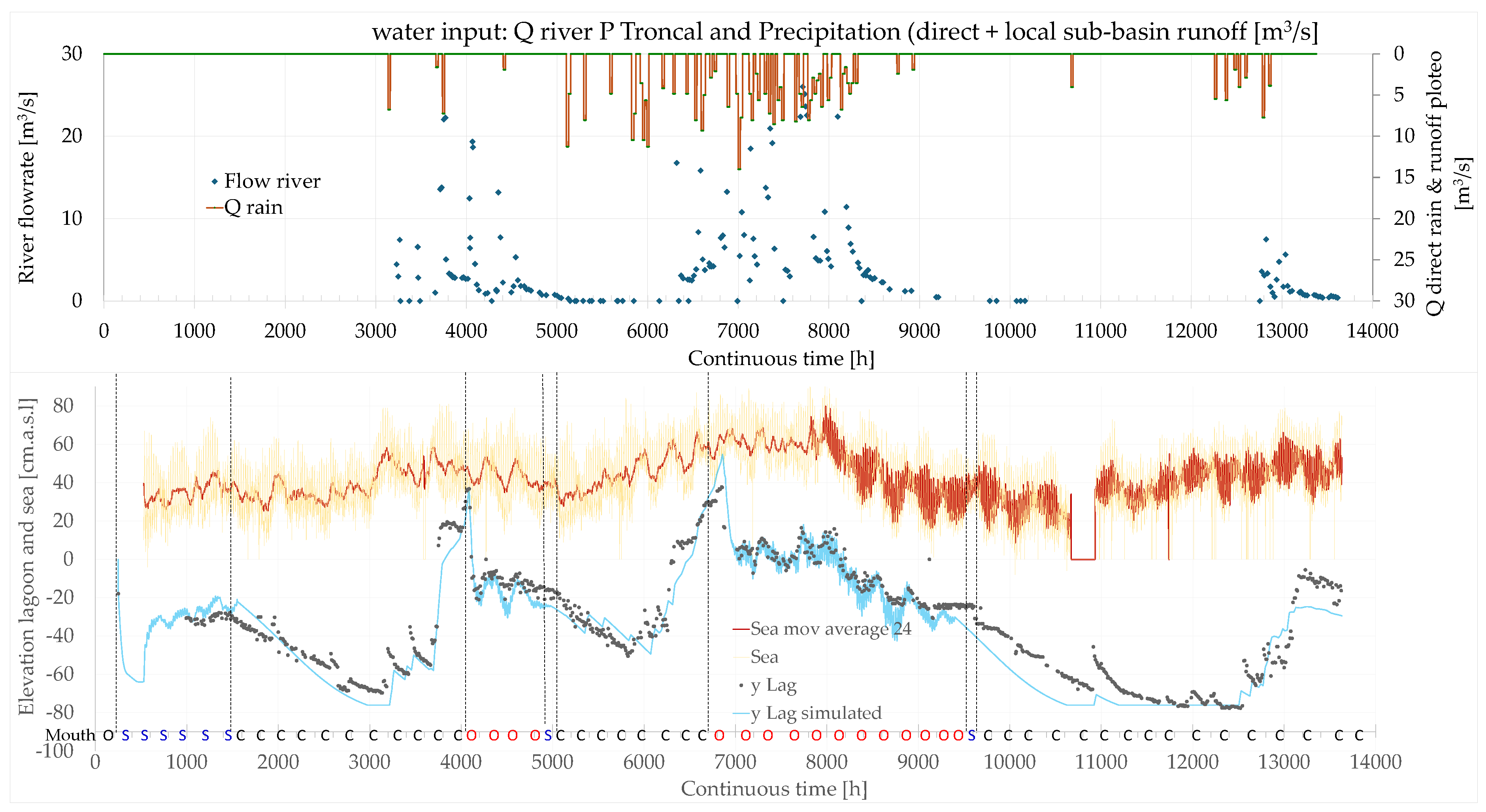

4.2. Replicating the Historical Data Set

4.2.1. The 0D Case (Excel® Model)

4.2.2. The 2D Case (EFDC+ Model)

5. Results

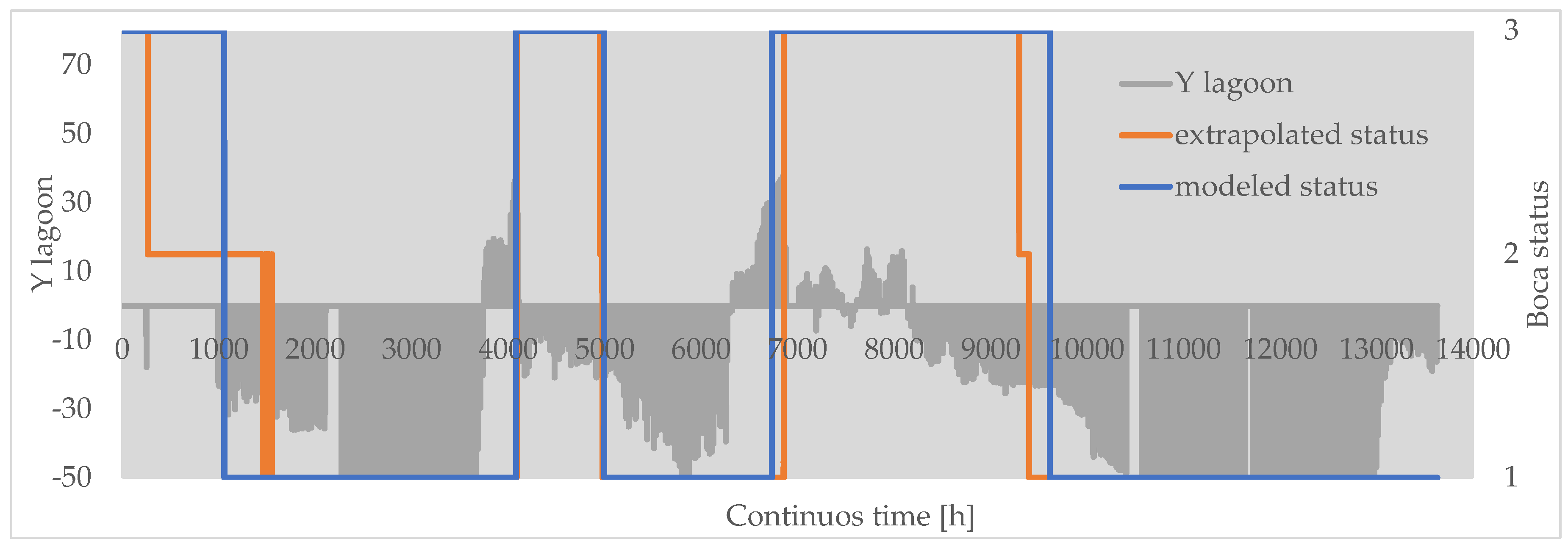

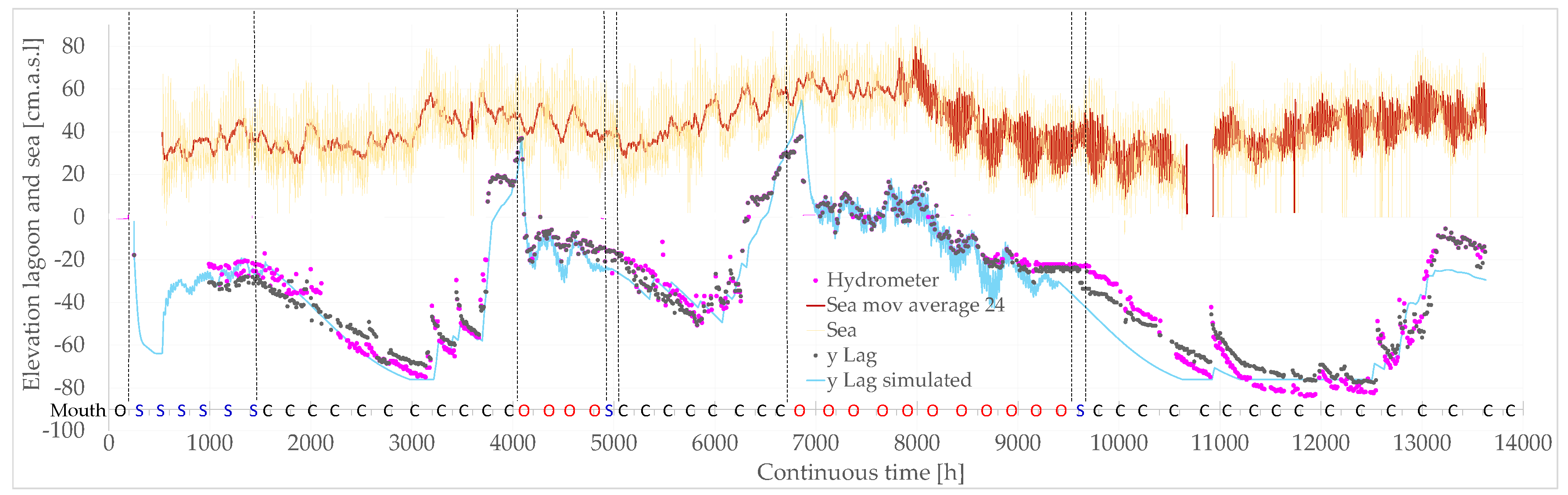

5.1. Results for 0D Model

- ▪

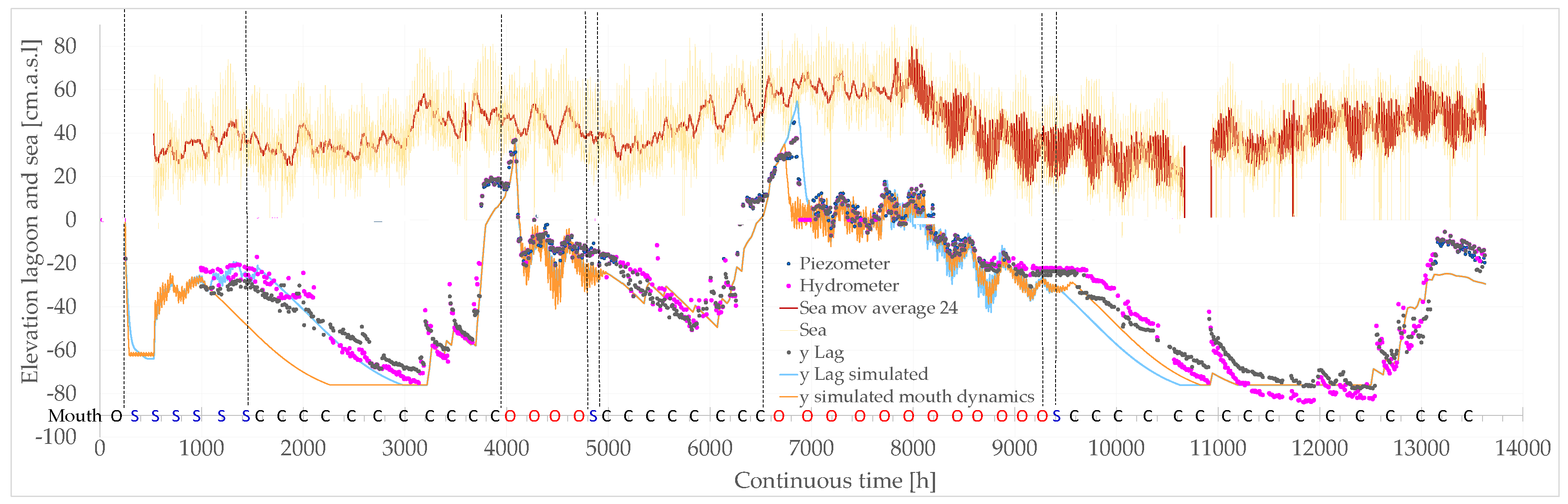

- A thorough coherence with the general system behavior is evident (Figure 10)

- ▪

- The model represents quite well measurements, although there is a general sub-estimation clearly due to lack of river inflow inputs (particularly between time 8300 and 11000, Figure 11) and a sporadic small overestimation, still lying between the hydrometer and piezometer data boundaries (notice that in the initial period until t=3000, the two instruments, hydrometer and piezometer, needed some adjustments and were less reliable).

- ▪

- The tide is very “nervous”, with an amplitude of oscillations significantly larger than that of the lagoon; this is more linked to the 24h moving average. In addition, it is evident that between time 7000 until 9300 approximately, the lagoon elevation oscillation is much wider, but so is also the tide (actually its 24 h moving average value). In general, it must be considered that the lagoon elevation measurements only occur twice a day and hence, with such a low frequency sampling, it is very unlikely that the maxima and minima are indeed captured (Figure 12).

- ▪

- There may also be calculation errors; indeed, the Euler method adopted structurally introduces some errors as, for instance, it determines the evaporation flow in the interval (k, k+1) based on the lagoon water surface (S(k) at time k, while it is constantly changing. Other errors may be due to an incorrect numerical representation of the morphometric relationships and to reckoning approximations.

- ▪

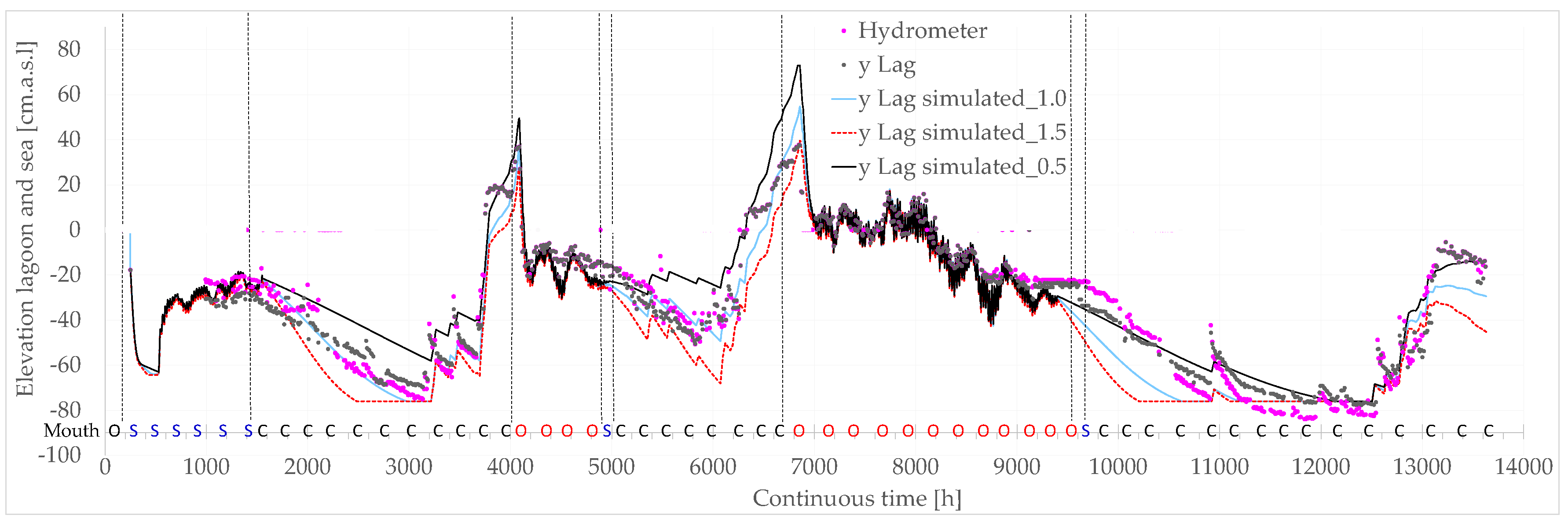

- The system appears to be very sensitive to evaporation as shown in Figure 13. This means that more attention should be paid in the determination of the evaporation rate.

- ▪

- Finally, the cross-section area of the boca determines the amplitude of the water surface oscillations (and the associated flow rates), but not the general pattern of the elevation, as shown in Figure 14 for an increased value of 50% in the period 7000-9000 (as an example).

5.2. Results for 2D Model

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nardini, A.G.C.; Escobar Villanueva, J.R.; Pérez-Montiel, J.I. Hydrological Monitoring System of the Navío-Quebrado Coastal Lagoon (Colombia): A Very Low-Cost, High-Value, Replicable, Semi-Participatory Solution with Preliminary Results. Water (Switzerland) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartiss, M.R. Lake.Xy Module.

- Chow, V.T. Open-Channel Hydraulic; McGraw-Hill, Ed.; New York, 1959; ISBN 978-0-07-085906-7.

- Corporación Autónoma Regional de La Guajira [CORPOGUAJIRA] Ajuste y/o Actualización Del POMCA Del Río Camarones y Otros Directos Al Caribe – La Guajira; Riohacha, Colombia, 2022.

- Young, D.M.; Gregory, R.T. A Survey of Numerical Mathematics; Ed. orig.: Reading : Addison-Wesley, 1972, Ed.; Courier Corporation: New York, 1988; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Moraru, A.; Rüther, N.; Bruland, O. Investigating Optimal 2D Hydrodynamic Modeling of a Recent Flash Flood in a Steep Norwegian River Using High-Performance Computing. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 25, 1690–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Xia, M. Seasonal Dynamics of Water Circulation and Exchange Flows in a Shallow Lagoon-Inlet-Coastal Ocean System. Ocean Model. 2023, 186, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Bejarano, F.M.; Torregroza-Espinosa, A.C.; Martinez-Mera, E.; Castañeda-Valbuena, D.; Tejera-Gonzalez, M.P. Hydrodynamics and Water Quality Assessment of a Coastal Lagoon Using Environmental Fluid Dynamics Code Explorer Modeling System. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2020, 6, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanis, I.K.; Wu, J.; Shen, H.; Valeo, C. Environmental Hydraulics: Hydrodynamic and Pollutant Transport Modelling of Lakes and Coastal Waters. In Environmental Hydraulics; Tsanis, I.K., Wu, J., Shen, H., Valeo, C., Eds.; Developments in Water Science; Elsevier, 2006; Vol. 56, pp. vii–360.

- Gunasinghe, G.P.; Ruhunage, L.; Ratnayake, N.P.; Ratnayake, A.S.; Samaradivakara, G.V.I.; Jayaratne, R. Influence of Manmade Effects on Geomorphology, Bathymetry and Coastal Dynamics in a Monsoon-Affected River Outlet in Southwest Coast of Sri Lanka. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrling, G.; Winter, C. Spatiotemporal Variability of Sedimentology and Morphology in the East Frisian Barrier Island System. Geo-Marine Lett. 2017, 37, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, J.H.; Törnqvist, T.E.; Esposito, C.R. Crevasse Splays Versus Avulsions: A Recipe for Land Building With Levee Breaches. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 4058–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Leonardi, N.; Plater, A.J. Impact of Barrier Breaching on Wetland Ecosystems under the Influence of Storm Surge, Sea-Level Rise and Freshwater Discharge. Wetlands 2020, 40, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S.M.; Oumeraci, H. Combined Modelling of Coastal Barrier Breaching and Induced Flood Propagation Using XBeach. Hydrology 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maicu, F.; Abdellaoui, B.; Bajo, M.; Chair, A.; Hilmi, K.; Umgiesser, G. Modelling the Water Dynamics of a Tidal Lagoon: The Impact of Human Intervention in the Nador Lagoon (Morocco). Cont. Shelf Res. 2021, 228, 104535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, J.H.; Heijkers, L.G.H.; Ruessink, G. Barrier Breaching Versus Overwash Deposition: Predicting the Morphologic Impact of Storms on Coastal Barriers. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2021, 126, e2021JF006066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.A.; Goodman, D.H.; Som, N.A.; Alvarez, J.; Martin, A.; Hardy, T.B. Improving Hydrodynamic Modelling: An Analytical Framework for Assessment of Two-Dimensional Hydrodynamic Models. River Res. Appl. 2017, 33, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wu, W.; Wang, Q.J.; Vaze, J. A 2D Hydrodynamic Model-Based Method for Efficient Flood Inundation Modelling. J. Hydroinformatics 2022, 24, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, M.; Zaïbi, C.; Langer, M.R.; Carbonel, P.; Ben Youssef, M. Coastal Dynamics and the Evolution of the Acholla Lagoon (Gulf of Gabes, Tunisia): A Multiproxy Approach. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmer, J.; Sire, C.; Lecacheux, S.; Idier, D.; Pedreros, R. Improved Metamodels for Predicting High-Dimensional Outputs by Accounting for the Dependence Structure of the Latent Variables: Application to Marine Flooding. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 2919–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wei, J.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, G.; Shao, S.; Tang, S. HydroMP – a Computing Platform for Hydrodynamic Simulation Based on Cloud Computing. J. Hydroinformatics 2017, 19, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Yeon, K.; Hur, Y.; Oh, K. Salinity Intrusion Characteristics Analysis Using EFDC Model in the Downstream of Geum River. J. Environ. Sci. 2010, 22, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, T.J.; Lee, S.-T.; Craig, P.M.; Lam, N.T.; Scandrett, K.; Mishra, A.; Arifin, R.R.; Jung, J.Y. Estuarine Salinity Intrusion and Implications for Aquatic Habitat: A Case Study of the Lower St. Johns River Estuary, Florida. In Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2019; 2019; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Bejarano, F.; González-Martínez, J.; Rodríguez-Pérez, J.; Rodríguez-Cuevas, C.; Mathis, T.J.; Tran, D.K. Characterization of Salt Wedge Intrusion Process in a Geographically Complex Microtidal Deltaic Estuarine System. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2023, 131, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrick, J.M. A Three-Dimensional Environmental Fluid Dynamics Computer Code: Theoretical and Computational Aspects. Spec. Rep. Appl. Mar. Sci. Ocean Eng. ; no. 317.. Virginia Inst. Mar. Sci. Coll. William Mary. 1992, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, S. V; Protsenko, E.A.; Kharchenko, A. V Comparison of Hydrodynamic Processes Modeling Results in Shal-Low Water Bodies Based on 3D Model and 2D Model Averaged by Depth. Comput. Math. Inf. Technol. 2023, 6, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, I.; Castro-Rosero, L.M.; Espino, M.; Alsina Torrent, J.M. LOCATE v1.0: Numerical Modelling of Floating Marine Debris Dispersion in Coastal Regions Using Parcels v2.4.2. Geosci. Model Dev. 2024, 17, 2221–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y. An Implicit 1D-2D Deeply Coupled Hydrodynamic Model for Shallow Water Flows. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabi, J.N.; wa Maina, C.; Mharakurwa, E.T.; Mathenge, S.W. Low Cost, LoRa Based River Water Level Data Acquisition System. HardwareX 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notter, B.; MacMillan, L.; Viviroli, D.; Weingartner, R.; Liniger, H.P. Impacts of Environmental Change on Water Resources in the Mt. Kenya Region. J. Hydrol. 2007, 343, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E. A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. J. Basic Eng. 1960, 82, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavdekar, V.A.; Deshpande, A.P.; Patwardhan, S.C. Identification of Process and Measurement Noise Covariance for State and Parameter Estimation Using Extended Kalman Filter. J. Process Control 2011, 21, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Period | Yearly | Monthly | ||

| IN | river | 94.00 | 61.54 | 5.13 |

| precipitation & runoff | 30.78 | 20.15 | 1.68 | |

| incoming sea | 195.10 | 127.72 | 10.64 | |

| Total | 319.88 | 209.41 | 17.45 | |

| OUT | outgoing to sea | 265.09 | 173.55 | 14.46 |

| evaporation | 58.46 | 38.27 | 3.19 | |

| storage loss | -1.90 | -1.24 | -0.10 | |

| Total | 321.65 | 210.58 | 17.55 | |

| BALANCE | IN-OUT | -1.78 | -1,17 | -0,10 |

| error | as a % of IN | 0.56 | 0,55 | 0,55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).