1. Introduction

Plants can endure diverse abiotic and biotic stressors by altering their physiology and biochemistry which may also change their metabolome. Plant secondary metabolites (PSMs), including phenolic compounds, can exhibit qualitative and/or quantitative changes in response to regulatory processes and thereby mitigate the impacts of potentially harmful stressors [1-6]. The identification of metabolites mediating plant tolerance of stress is essential to understand adaptive responses. Unbiased (or non-targeted) metabolomics has emerged as a powerful tool to investigate plant responses because it expedites the identification of metabolites of potential adaptive significance [

7,

8].

Phenolic compounds are the most abundant and widely occurring PSMs of the plant kingdom [

9,

10]. Possibly the most studied of the phenolic compounds are the “tannins” because they have been implicated (rightly and wrongly) in many interactions between plants and herbivores [11-14]. Structurally, phenolic PSMs comprise at least one aromatic ring with one or more hydroxyl group. The interactions between these two structural moieties are key to their biological activity via the ability to produce free radicals where the radical is stabilised by delocalisation [

9,

10,

15]. High molecular weight tannins (e.g. the hydrolysable and condensed tannins) have been shown to be up to 15-20 times more effective in quenching peroxyl radicals than simple polyphenols [

16]. Oxidative stress arising from photodamage has been suggested to be at least as important, if not more so, to the evolution and proliferation of plant phenolic compounds as herbivory [

17]. The importance of phenolic compounds for photoprotection of eucalypt leaves was first proposed by Close & McArthur [

17].

UV radiation is a known elicitor for the synthesis of PSMs [

18]. Almost 95% of UV

A and 5% of UV

B radiation penetrates the Earth’s atmosphere and reaches the surface. Although UV

A is less damaging than UV

B, it can penetrate deeper and is more abundant. Hence, UV

A can cause significant damage to plant tissues and DNA [

19,

20]. The lower cloud cover over Oceania and Antarctica compared to the rest of the world means there is a significantly greater flux of UV

A in these regions than elsewhere on the planet [

21]. Therefore, plants at these latitudes are exposed to higher UV

A, with UV flux increasing by approximately 1–2% per one degree of latitude away from the equator [

22,

23]. Although plants are exposed 10-100 times more UV

A than UV

B, most research has focussed on the effects of UV

B.

Phenolic compounds have unique absorption maxima and can absorb UV radiation without affecting the availability of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). For example, hydroxycinnamic acid exhibits maximum absorption between 310−332 nm, flavones between 250−270 and 330−350 nm and flavonols between 250−270 nm and 350−390 nm [

24]. Studies on the effects of increased UV on a variety of non-woody, herbaceous plants and fruits are numerous because phenolic compounds can affect the colour and/or flavour of the edible tissues to humans [

25]. Such studies often report increased concentrations of a range of phenolic compounds [26-28], however, some have reported no change in composition [

29].

For such an ecologically and economically important group of trees, the paucity of information about the responses of eucalypts (an informal grouping encompassing the genera

Eucalyptus,

Angophora and

Corymbia and others) to abiotic stressors is surprising, in particular their tolerance of the harsh Australian sun. Since our lab was already researching natural variation in foliar phenolics of river red gum,

Eucalyptus camaldulensis [

30,

31], we chose to conduct an experimental study to quantify how this widely distributed species responds to a specific component of solar radiation, namely UV

A, at low and elevated fluxes. Rather than use conventional analytical techniques to assess changes in phenolics composition, we chose to employ an unbiased metabolomics approach. Such an approach has not been applied to eucalypt phytochemistry before.

2. Results

The leaves of

E. globulus and, to a lesser extent,

E. nitens have been reported to develop epidermal blisters and exhibit curling when grown under elevated humidity such as can occur in glasshouses [

32]. We did not observe any similar morphological responses by the leaves of our saplings which could suggest they experienced ambient humidities comparable to those experienced under non-glasshouse conditions. Alternatively,

E. camaldulensis might not respond similarly to high humidity as do the two aforementioned species.

2.1. Effect of Provenance on Phenolic Composition

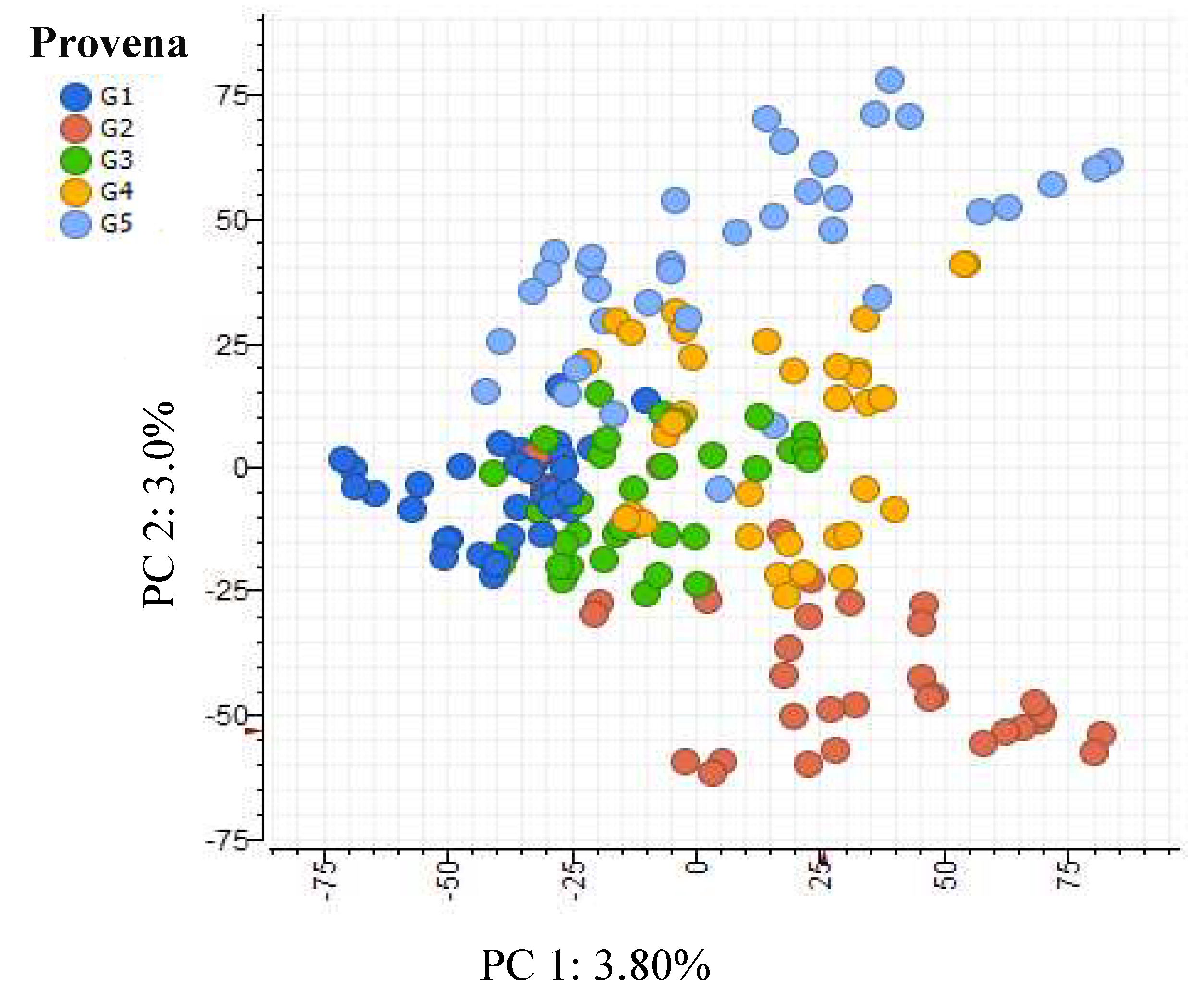

A PCA ordination of the phenolics of the individual saplings used in the experiment revealed some differentiation according to provenance (

Figure 1). The variation explained by the first principal component was only 3.8% while the variation explained by the second was also small at only 3.0%. PC1 provided the greatest separation of G

1 (latitude -31.46S) and G

2 (latitude -35.75S) and PC2 provided the greatest separation of G

2 and G

5 (latitude -33.10S).

K-group analysis identified five phenolic metabolites that were differentially expressed among the provenances and which had high loadings. Four of these metabolites were tentatively identified as: pentagalloylglucose (m/z 939.1107), galloylglucose (m/z 331.0669), a quercetin derivative (m/z 433.0408), HHDP-galloylglucose (m/z 633.0735) and an unknown phenolic compound (m/z 337.2052). Pentagalloylglucose occurred in the highest abundance in G1 and occurred in the lowest abundance in G2. The quercetin derivative occurred in the highest abundance in G1 and occurred in the lowest abundance in G4 (latitude -33.85S).

2.2. Effect of UVA on Phenolic Composition

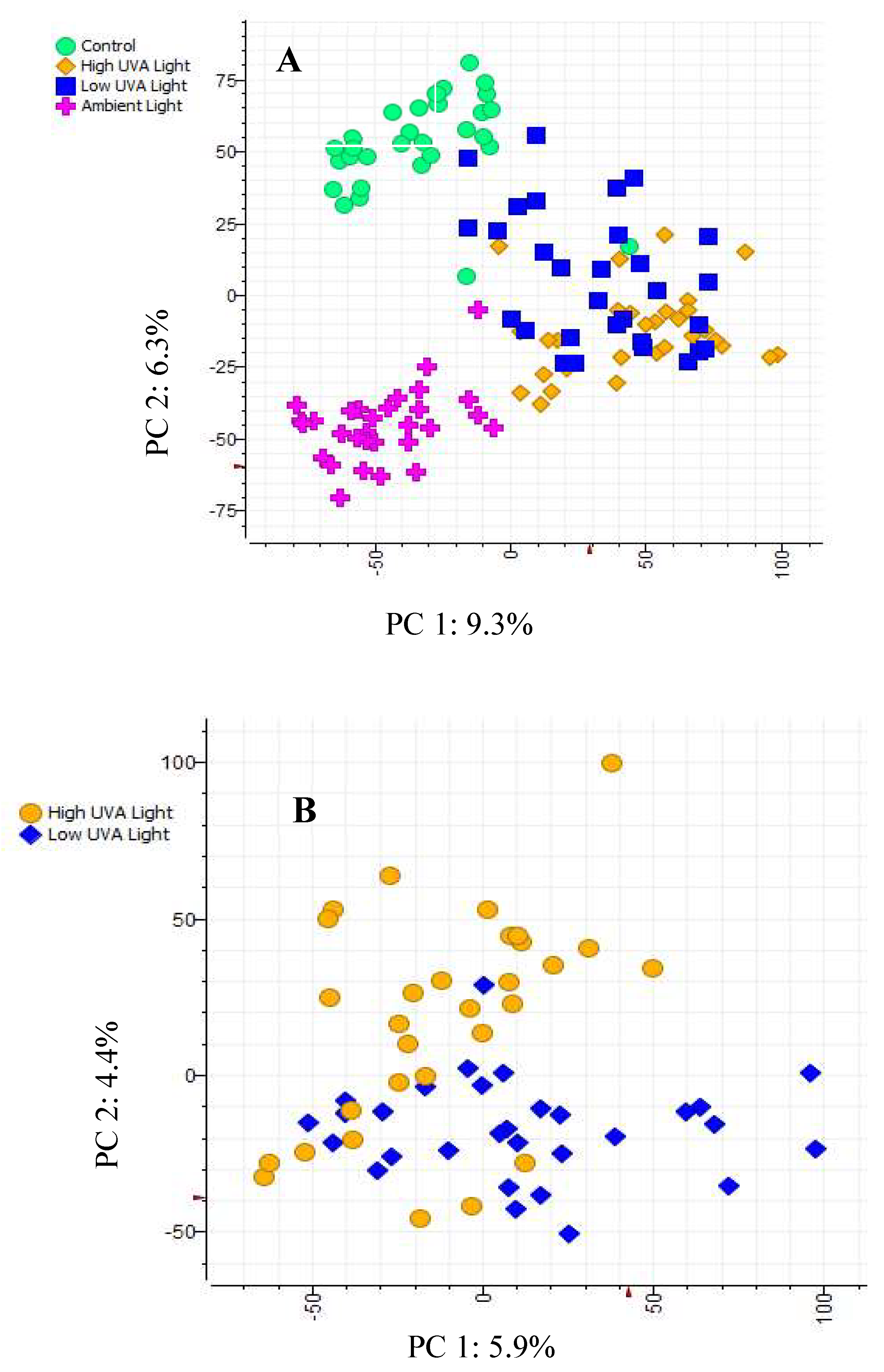

A PCA ordination showed a clear separation of saplings according to the light treatment they were grown under (

Figure 2A). On PC1 (9.3% variation), samples from high and low light treatments clustered apart from the samples from the control and ambient light treatments. Re-modelling the data using only the samples from the high and low light treatments gave a clear separation of phenolic metabolomes (

Figure 2B). However, PC1 of this second ordination only explained 5.9% of the variation in the data.

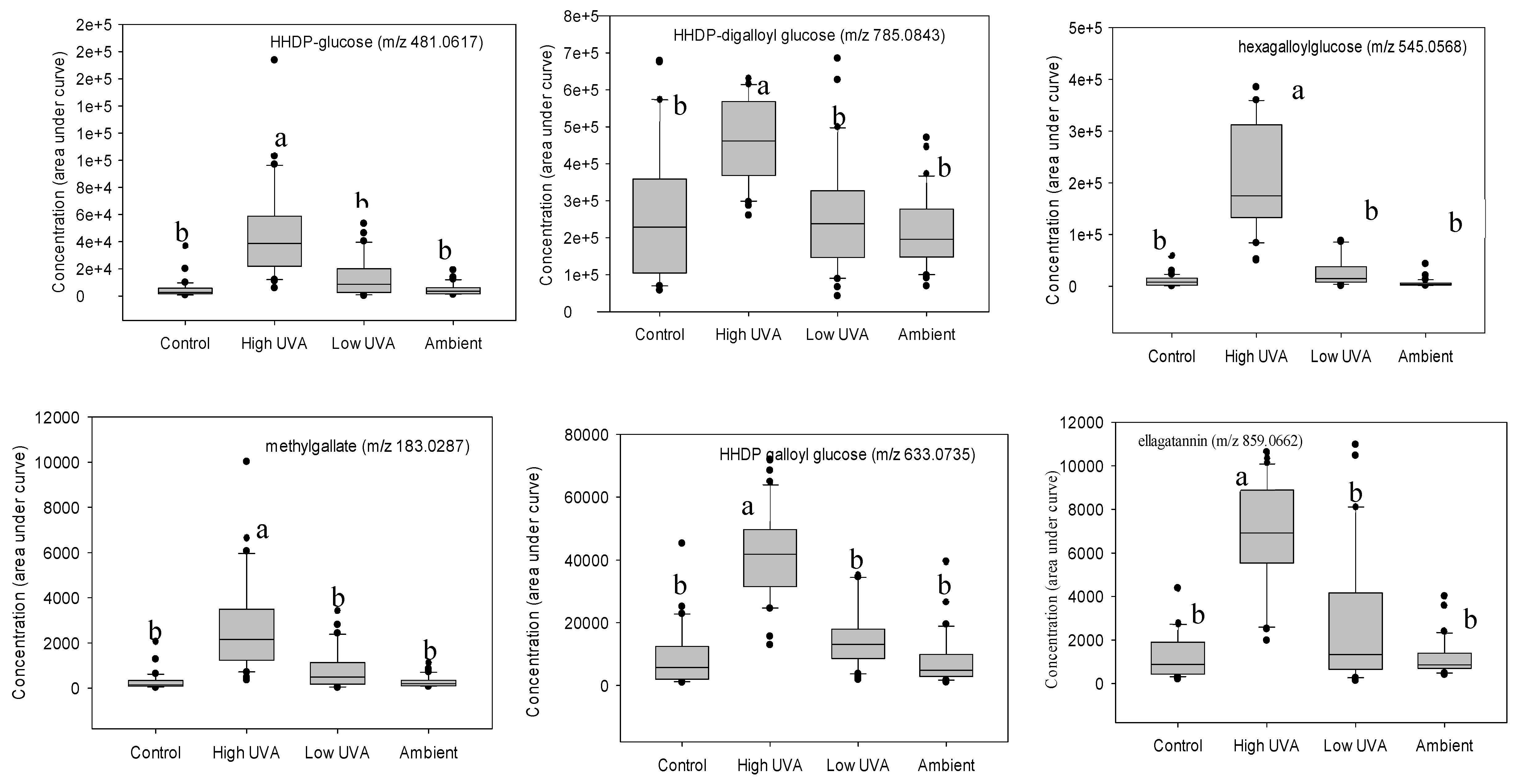

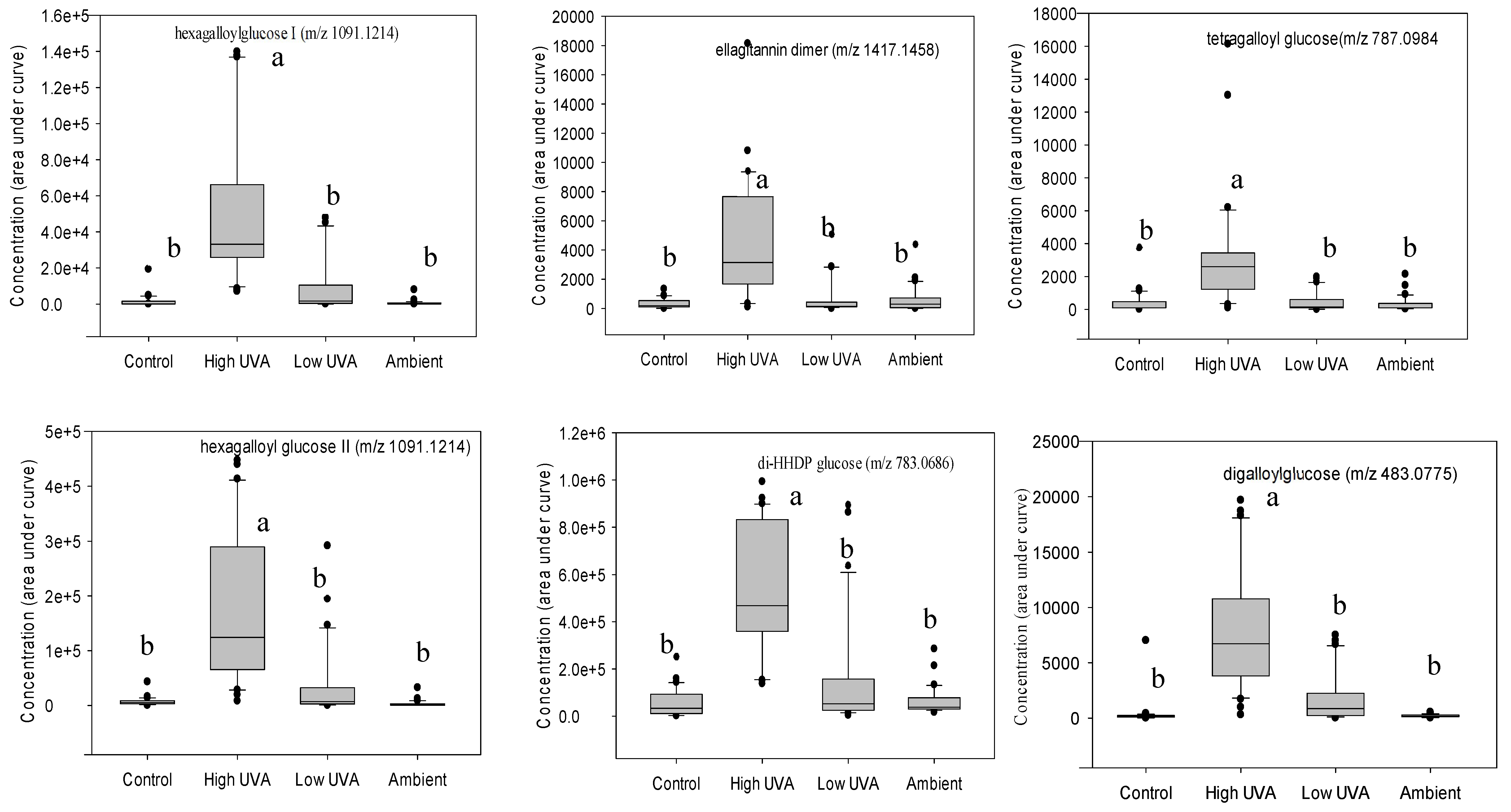

K-group analysis identified 20 compounds based on their effect size (

Table 1). Additional MS/MS tandem mass spectrometry and fragmentation enabled 17 of these phenolic compounds to be tentatively identified (

Table 1). Tukey’s multiple comparisons of means revealed that 12 hydrolysable tannins (comprising ellagitannins and gallotannins) occurred in significantly higher concentrations in leaves grown under the high UV

A treatment (

Figure 3).

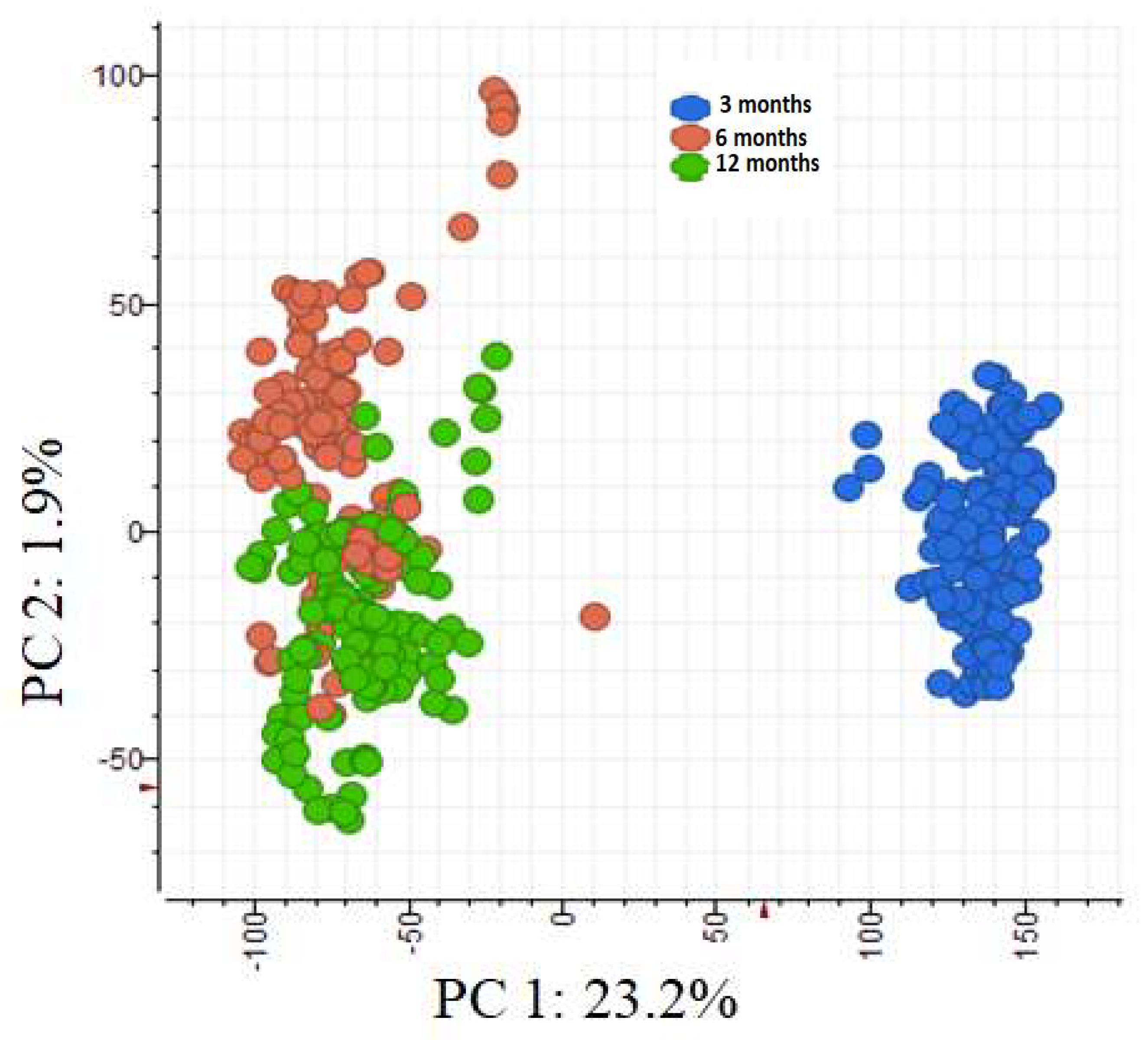

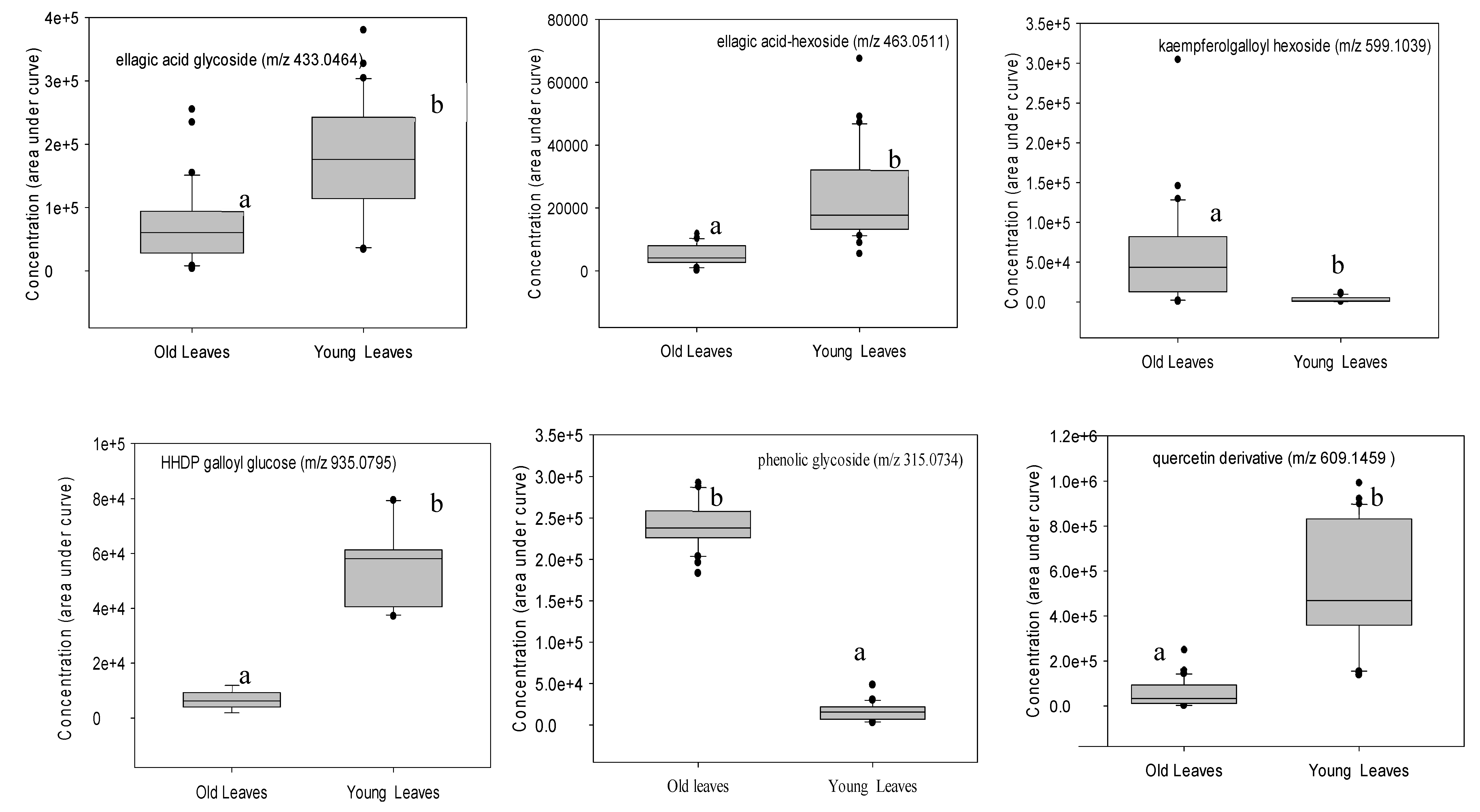

Leaf age was the most influential factor in the differential expression of phenolic compounds (

Figure 4). The phenolic metabolomes of six- and 12-month-old leaves (PC2 1.9% variation) were more alike than those of three-month-old leaves (PC1 23.2% variation). Since the separation between six- and 12-month-old leaves was comparatively small, we combined these data and refer hereafter to them ‘old leaves’; we refer to the three-month-old leaves as ‘young leaves’. Based on fold-change and

P-value, 14 phenolic compounds differed significantly in concentration between the two age classes (

Table 2). Concentrations of pedunculagin, catechin and kaempferol galloylglucoses were higher in old leaves whereas concentrations of hydrolysable tannins and quercetin were higher in young leaves (

Figure 4).

3. Discussion

Through our unique experimental and analytical approaches, we have obtained important new insights into the effect of light intensity and quality on the expression of phenolic compounds by Australia’s most iconic and globally significant species of tree. The only other study to investigate the effect of UV

A on the composition of eucalypt foliar phenolics is that by Close

et al. [

33]. Nevertheless, these authors [

33] only excluded UV

A radiation rather than replicating different intensities of exposure. Moreover, these authors studied a species of eucalypt (namely shining gum,

Eucalyptus nitens) which has a restricted region of endemism in high altitude, frost-prone habitats in the Australian Alps and which might therefore be expected to be better adapted to higher UV

A radiation than

E. camaldulensis.

3.1. Effect of Provenance on Phenolic Composition

We found that foliar concentrations of pentagalloylglucose and quercetin (a flavonol) were higher in provenances from lower latitudes, e.g. G

1 from Wilcannia (average annual rainfall 264 mm) and G

3 from Boolcunda Creek (average annual rainfall 306 mm). These provenances of

E. camaldulensis, in particular, have evolved under conditions of very low average annual rainfall and pronounced drought. Pentagalloylglucose has been reported to be an effective 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazine (DPPH) radical scavenger and to have higher free radical scavenging properties than vitamin C [

34]. Plant flavonols, such as quercetin, flavonoids and anthocyanins have strong radical scavenging activities and, when in elevated concentrations, can contribute to the mitigation of drought stress [

3,

35,

36]. In the morphologically juvenile leaves of a selection of provenances of

E. globulus and

E. viminalis, mild water deficit induced an increase in the concentrations of condensed tannins [

5]. These authors also reported that trait plasticity in response to water deficit was less pronounced than that of constitutive trait variation among provenances. We suggest that a similar explanation could underpin the relatively small influence of provenance we found in our study.

3.2. Effect of UVA on Phenolic Composition

Our results revealed an increase in the concentrations of phenolic acids, hydrolysable tannins and flavonoids under high UV

A. Close

et al. [

37] reported two periods of elevated concentrations of total anthocyanins in the leaves of nutrient deprived, seedling

E. nitens which corresponded with photoinhibitory growing conditions, i.e. low ambient temperatures and high light. The concentrations of galloylglucose and flavonols were not related to the anthocyanin concentration at these times which the authors suggested negated a possible role of anthocyanins in foliar antioxidant activity. Rather, Close

et al. [

37] proposed that higher concentrations of anthocyanins in nutrient deprived seedlings during photoinhibitory conditions supported their role in light attenuation. In contrast, Tian

et al. [

38] suggested that pentagalloylglucose provided photoprotection to the leaves of

Eucalyptus [

globulus] ssp.

maidenii. At least three studies report enhanced biosynthesis of quercetin under UV

B stress suggesting its active role in photoprotection [39-41]. Chloroplast-located quercetin and its glycosides are known for their role as effective singlet oxygen quenchers as generated by excess blue light [

42].

3.3. Effect of Leaf Age on Phenolic Composition

Perhaps not surprisingly, we found that leaf age had the greatest influence on the composition of phenolic compounds in our study species. The contrast in phenolic composition was most pronounced when leaves were three-months old compared to when they were either six- or 12-months-old. Leaves three-months-old had higher concentrations of phenolic acids, flavonoids, quercetin and hydrolysable tannins (both galloylglucose and ellagitannins) whereas leaves six- and 12-months-old had higher concentrations of glycosylated hydroquinone, kaempferol galloylhexoside and pedunculagin. The photosynthetic apparatus of leaves is not fully functional when they are young and hence requires protection [

43]. In some eucalypts, including

E. camaldulensis, anthocyanins attenuate light intensity in young leaves before the concentration of chlorophylls rises thereby increasing their photosynthetic capacity [

44]. This can give the young leaves of some species of eucalypt an obvious red colouration. Since anthocyanins and phenolic compounds share the same biosynthetic pathway (the phenylpropanoid pathway), young red leaves are likely to produce non-pigment compounds with photoprotective properties, e.g. tannins [

37,

45]. McArthur

et al. [

46] reported that the total phenolic concentration of

E. nitens was not attained until seedlings were 200 days old. Goodger

et al. [

47] also reported that foliar phenolic compounds were more abundant in young seedlings of

E. froggattii compared to adult trees. Neither of these studies tagged individual leaves to record the specific age of the foliage used for their analyses.

3.4. Summary

Photodamage is a potential stress that arises when the quanta of incoming solar radiation greatly exceeds the energy able to be utilised by a leaf’s photosynthetic apparatus. Unused photons generate reactive oxygen species (ROS; [

19]) which cause oxidative damage to the leaf’s enzymes, lipids and pigments leading to tissue death [

17]. ROS are highly reactive forms of oxygen that possess at least one unpaired electron in their orbitals. Under steady state conditions, ROS are scavenged by various antioxidative defence mechanisms (enzymatic and non-enzymatic). Adaptation to photodamage partly explains why expanding (young) eucalypt leaves are often red in colour under natural light. Our results show that phenolic compounds are abundant in young (three-month-old)

E. camaldulensis leaves. As oxygen rich compounds, tannins and flavonols can act as non-enzymatic antioxidants [

19,

48] while hydrolysable tannins can facilitate photoprotection by preventing anthocyanin degradation [

49]. Antioxidants accept electrons from ROS and thereby neutralise them. Phenolic compounds are synthesised by either the combination of the acetate-malonate and shikimate pathways (flavonoids and condensed tannins) or by the shikimate pathway only (hydrolysable tannins such as ellagitannins and gallotannins). Typically, condensed tannins are more abundant in old leaves while the structurally simpler hydrolysable tannins are more abundant in young leaves [

13,

50].

We are unable to state whether our treatments, in particular the high UV

A treatment, induced ‘stress’ in our saplings because we took no physiological measurements of foliar photosynthetic efficiency, e.g. as potentially assessed using chlorophyll fluorescence [

51]. However, we can state that a number of hydrolysable tannins were more abundant in the leaves grown under our high UV

A treatment which could represent an adaptive response to this potential stress. It is possible that the severity of photodamage we induced might be relatively mild because the saplings were grown under mild ambient temperatures and they were not nutrient deficient. As previous studies have shown, photoinhibition in eucalypts occurs when leaves are exposed to high light during cold periods and/or when plants are nitrogen deficient. In

E. moluccana and

E. fasciculosa, the symptoms of photodamage of old (fully expanded) leaves were produced when they had experienced such abiotic conditions and their photosynthetic capacity had been reduced by the feeding activities of senescence inducing psyllids belonging to the genus

Cardiaspina [

52,

53]. Future studies should aim to include low temperatures and nitrogen limitation as experimental factors to gain a fuller understanding of the effects of elevated UV

A on the expression of phenolic compounds by river red gum. An even more complete picture could be provided by also measuring leaf colour, chlorophyll concentrations and photosynthetic efficiency. Such information is needed because river red gum is widely used in revegetation schemes around Australia and interventions to increase establishment success (e.g. condition of seedlings, time of planting, type of shelter) can reduce the need for replanting.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Species and Growing Conditions

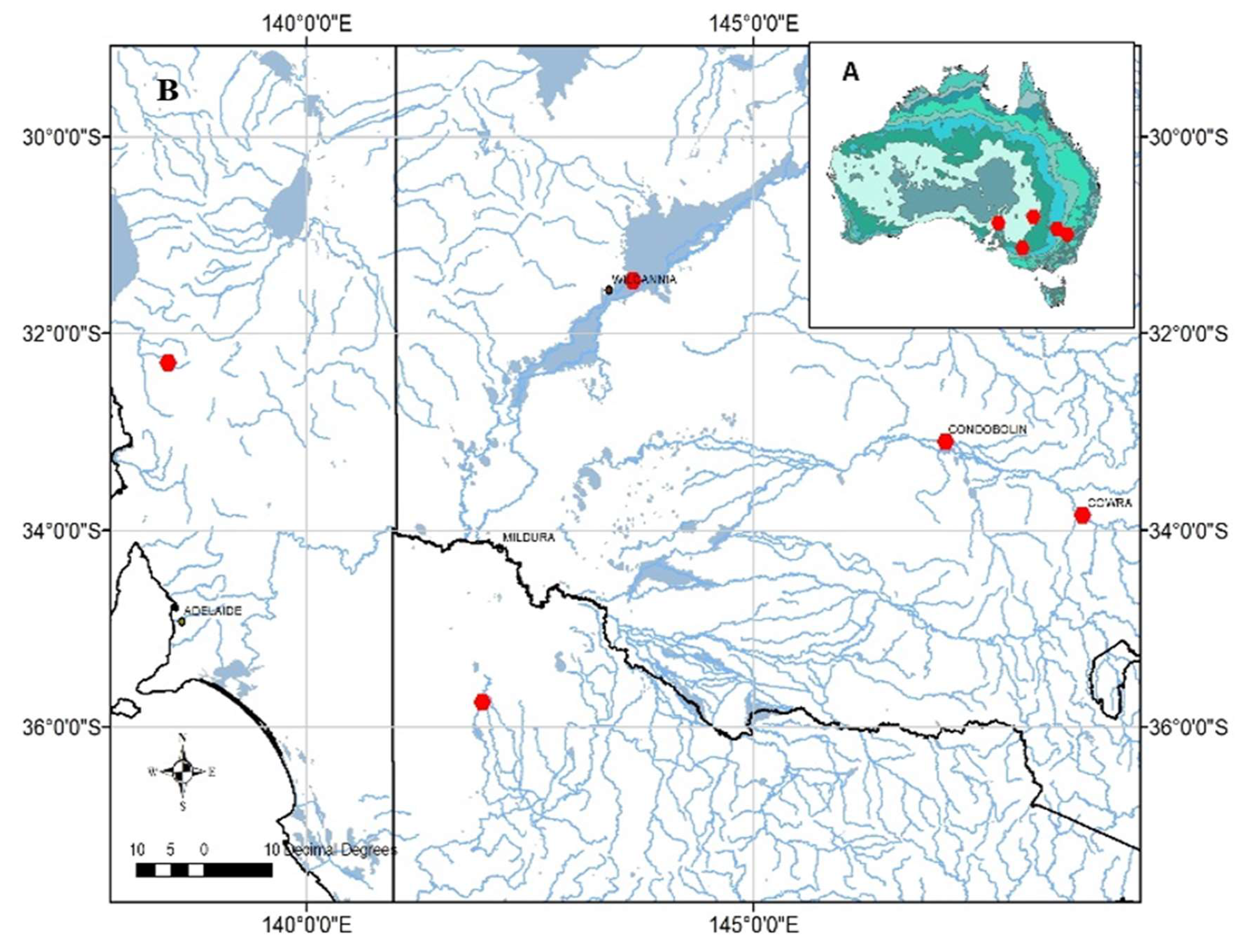

The river red gum (

Eucalyptus camaldulensis) is one of Australia’s most widely distributed species of tree; seven subspecies (abbreviated to ssp.) with distinct distributions are recognised [

54]. We purchased five seedlots of the most well-known and widely (globally) planted subspecies, namely

Eucalyptus camaldulensis ssp.

camaldulensis, for our study from the Australian Tree Seed Centre (ATSC), Canberra. These seedlots encompass the entire five-degree latitudinal range of the subspecies which is characterised by a modest UV

A gradient (

Figure 5). For example, the parent trees from which these seedlots were harvested span locations varying in annual rainfall from 200 to 600 mm per annum (

Table 3). We use the term ‘provenance’ in recognition that the seedlots are from different geographic locations and, hence, that each population has experienced unique conditions of solar radiation, temperature and rainfall. Such environmental influences have been shown to be associated with morphological divergence of the leaves of

E. camaldulensis from disparate geographic locations [

55] as well as high genetic differentiation among populations [

56]. The terms provenance, genotype and family have been used interchangeably in similar studies of eucalypt PSMs [5,31,57-60].

Seeds were germinated on Scotts Osmocote Seed and Cutting Premium Potting Mix. One month after germinating, seedlings were transferred to 12 cm pots and maintained in a temperature-controlled glasshouse in the Agriculture Reserve, La Trobe University. The saplings were grown in native plant potting mix and given 200 mL of water every other day. Branches were bent to the horizontal and repositioned using bonsai wire to maintain constancy of light exposure. Frames supporting LED lights were adjusted to keep a constant distance of 50 cm from the tops of the saplings. The temperature was maintained at approximately 21°C with an 18-hour photoperiod. The saplings were rotated two to three times per week so that all plants were equally illuminated.

4.2. Experimental Treatments, Leaf Tagging and Harvesting

This study was conducted under glasshouse and ambient (natural light) conditions. Potted saplings were exposed to four treatments, namely (1) glasshouse high UV

A, (2) glasshouse low UV

A, (3) glasshouse no UV

A [control] and (4) ambient light [natural light outside the glasshouse]. The latter two treatments represent a procedural control and a natural reference, respectively. There were six saplings (replicates) per provenance for a total of 30 saplings per treatment. There were 120 saplings in total across the four treatments. Transparent UV-absorbing plastic film (SUN 5 Pro) to block solar UV radiation was purchased from Folien-Vertriebs GmbH, Dernbach, Germany, was used to cover the top of the three 1 m

3 experimental chambers inside the glasshouse (

Figure 6). The spectral properties of the film for UV

A and UV

B transmittance were measured by an ALMEMO 2390-5 data logger, equipped with UV

A and UV

B sensors (Ahlborn Mess und Regelungstechnik GmbH, Holzkirchen, Germany). The vertical walls of the experimental chambers were formed from black plastic to prevent sideways illumination of saplings. LED lights were fitted with adjustable chains for maintaining constant height above the plants.

To investigate the effect of leaf age on phenolic composition, branches and petioles were tagged using coloured cable ties to identify individual leaves according to their date of appearance. Tagged leaves from a single branch were harvested after (1) three months, (2) six months and (3) 12 months of UVA treatment. Harvested leaves were transferred to labelled paper envelopes and freeze-dried immediately using a Christ Alpha 1-4 LSC freeze drier and stored in the dark prior to analysis.

4.3. LED Lighting

UVA emitting LED lights at the maximum wavelength of 370 nm and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) emitting LED lights at the wavelength of 400 nm were purchased from Shenzhen Vanq Technology Co., Ltd, Guangdong Sheng, China. Two types of UVA LED lights were purchased, namely (1) radiation of 1800 kJ/m² UVA per day simulating mid-summer UVA [high UVA], and (2) radiation of 800 kJ/m² UVA per day simulating winter annual UVA [low UVA]. Light intensity was chosen based on average annual mid-summer and winter radiation data for Yallambie, Victoria (37°726'S, 145°104'E; data provided by the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA)). The spectral irradiance and flux of the LED lights were measured at ARPANSA and determined to be suitable for simulating mid-summer and winter UVA when distanced 50 cm from the plants. We assume that high UVA is likely to be the most stressful of the two experimental light treatments. Two chambers in the glasshouse were fitted with high and low UVA-LED lights in combination with PAR-LED lights. The control chamber was fitted with only PAR-LED lights. The same type of LED lights were used throughout the study.

4.4. Phenolics Extraction

Freeze-dried leaves were finely ground to ≤ 0.25 mm using a ball mill (Retsch MM400, Germany) at 30 Hz. 20 mg of finely ground leaf powder was weighed in duplicate into 2 mL microtubes and 1 mL of 80 : 20 MeOH : H2O (v/v) was added to each sample, and subsequently mixed with a vortex mixer for two minutes and sonicated for 10 minutes (Unisonics, Australia). Samples were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 15,000 rpm at room temperature (Eppendorf 5415D bench centrifuge, Hamburg, Germany). The extract was transferred to a clean labelled microtube. 1 mL of extract was transferred to HPLC vials for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis and 5 μL of each extract was used to prepare a pooled sample which served as a quality control (QC) sample to be analysed at the same time.

4.5. Chromatographic and Mass Spectrometric Analysis

Phenolic compounds were identified using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC, UHPLC+ focused, Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA) combined with a Q Exactive Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA) and a diode array detector. Data were collected in negative ion mode, scanning a mass range m/z of 100–1500. Negative ion mode was preferred over positive for phenolic compounds analysis for all the subgroups because of its sensitivity, and clearer fragmentation patterns and less extensive fragmentation. Nitrogen was used as the sheath and auxiliary and sweep gas and the spray voltage was set at 3,600 V. The capillary temperature was set to 300°C, with the S-lens RF level set at 64 and an auxiliary gas heater temperature of 310°C. A Hypersil GOLD C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm internal diameter, Thermo Scientific, USA) was used with the column compartment temperature set to 30°C, and a flow rate was maintained at 0.3 mL/min throughout data acquisition. The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile. A linear gradient was used beginning with 2% of B and reaching 100% of B at 15 min then kept steady at 100% of B until 18 min and then returned to an initial condition where it was held for 2 min. The MS/MS analyses were carried out by automatic fragmentation where the three most intense mass peaks were fragmented. The mass spectrometric (MS) analysis including the prediction of chemical formula and exact mass calculation was performed using Thermo Xcalibur Qual Browser software version 3.0.63 (Thermo Scientific, USA). The samples were injected into the mass spectrometry randomly (order organised by using the ‘RAND’ function in Microsoft Excel) with blank and QC samples injected every tenth sample.

4.6. Data Processing

The raw files from Xcalibur were imported to Genedata Expressionist Refiner MS version 12.0, Basel, Switzerland (

https://www.genedata.com/). Noise in the data was removed using filters toolsRT structure removal, chemical noise subtraction, peak detection, isotope clustering, adduct detection, singleton filter, and signal clustering. Further, QC was used for samples normalization to minimize and correct for batch variation. The volume of the cluster generated data from Genedata matrix was exported, visualized and analysed in Genedata Analyst™ 12.0.6 software (Genedata AG, Basel, Switzerland). Genedata Analyst was used for further integration and interpretation of results.

4.7. Data Analysis and Compound Identification

Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was used to visualise metabolite variation between groups and treatments. A two-groups test, using a Student's

t-test, in Genedata was used to compare feature between two treatments and

K-group analysis using ANOVA was used to compare more than two treatments. Highly significant values were ranked based on

P-values after Bonferroni correction (at

P = 0.05). For each Bonferroni correction, the critical

P-value was divided by the number of features and only the most statistically significant features were selected from the volcano plot produced by Genedata Analyst. These features were tentatively identified using online mass databases, comparison with standards, and MS/MS data. A more complete description of the process of compound identification and a full listing is provided in Chapter II of Khanal [

61].

Author Contributions

MJS conceived and designed the study, sourced all the materials and established the collaborative relationships. MJS (primary supervisor) and SJR supervised SK when a doctoral candidate. SJR and SK conducted the metabolomics analyses. SK wrote a first draft of the manuscript. MJS and SJR revised the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by LTUPRS and LTUFFRS stipends to SK and annual departmental allocations to MJS for research support for his post-graduate students.

Data Availability Statement

The metabolomics data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Robert Evans for assisting with the maintenance of the eucalypts in the Agriculture Reserve and for the construction of the experimental glasshouse chambers and for maintenance of the glasshouse climate control. We thank the ARPANSA staff for assisting with the assessment of flux intensity of the LED lights. We also thank Priyanka Reddy and Elizabeth Read for their advice regarding data analysis and interpretation and Angie Haslem for Figure 5. Juha-Pekka Salminen (University of Turku, Finland) provided expert phenolics extraction and analysis advice to MJS and SK. Ben Moore (Western Sydney University, Australia) and C. Peter Constabel (Centre for Forest Biology, University of Victoria, Canada) provided useful feedback on the thesis version of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Merchant, A., Tausz, M., Arndt, S. K., & Adams, M. A. (2006). Cyclitols and carbohydrates in leaves and roots of 13 Eucalyptus species suggest contrasting physiological responses to water deficit. Plant, Cell and Environment, 29(11), 2017-2029. [CrossRef]

- Merchant, A., Ladiges, P. Y., & Adams, M. A. (2007). Quercitol links the physiology, taxonomy and evolution of 279 eucalypt species. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16(6), 810-819. [CrossRef]

- Tharayil, N., Suseela, V., Triebwasser, D. J., Preston, C. M., Gerard, P. D., & Dukes, J. S. (2011). Changes in the structural composition and reactivity of Acer rubrum leaf litter tannins exposed to warming and altered precipitation: climatic stress-induced tannins are more reactive. New Phytologist, 191(1), 132–145. [CrossRef]

- McKiernan, A. B., Hovenden, M. J., Brodribb, T. J., Potts, B. M., Davies, N.W., & O’Reilly-Wapstra, J. M. (2014). Effect of limited water availability on foliar plant secondary metabolites of two Eucalyptus species. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 105, 55-64. [CrossRef]

- McKiernan, A. B., Potts, B. M., Brodribb, T. J., Hovenden, M. J., Davies, N.W., McAdam, S. A. M., Ross, J. J., Rodemann, T., & O’Reilly-Wapstra, J. M. (2016). Responses to mild water deficit and rewatering differ among secondary metabolites but are similar among provenances within Eucalyptus species. Tree Physiology, 36(2), 133-147. [CrossRef]

- Gourlay, G., & Constabel, C. P. (2019). Condensed tannins are inducible antioxidants and protect hybrid poplar against oxidative stress. Tree Physiology, 39(3), 345–355. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A., Marsal, S., & Julià, A. (2015). Analytical methods in untargeted metabolomics: State of the art in 2015. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 3. [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J., Cañal, M. J., Escandón, M., Meijón, M., Weckwerth, W., & Valledor, L. (2017). Integrated physiological, proteomic, and metabolomic analysis of ultra violet (UV) stress responses and adaptation mechanisms in Pinus radiata. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, 16(3), 485–501. [CrossRef]

- Appel, H. M. (1993). Phenolics in ecological interactions: the importance of oxidation. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 19(7), 1521-1552. [CrossRef]

- Cheynier, V., Comte, G., Davies, K. M., Lattanzio, V., & Martens, S. (2013). Plant phenolics: Recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, and ecophysiology. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 72, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Barbehenn, R. V., Jones, C. P., Hagerman, A. E., Karonen, M., & Salminen, J.-P. (2006). Ellagitannins have greater oxidative activities than condensed tannins and galloyl glucoses at high pH: Potential impact on caterpillars. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 32(10), 2253–2267. [CrossRef]

- Barbehenn, R. V., & Constabel, C. P. (2011). Tannins in plant-herbivore interactions. Phytochemistry, 72(13), 1551–1565. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, J.-P., & Karonen, M. (2011). Chemical ecology of tannins and other phenolics: we need a change in approach. Functional Ecology, 25(2), 325-338. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K. J., Wallis, I. R., Kulheim, C., Clark, R., Nicolle, D., Foley, W. J., & Salminen, J.-P. (2020). New approaches to tannin analysis of leaves can be used to explain in vitro biological activities associated with herbivore defence. New Phytologist, 225(1), 488–498. [CrossRef]

- Ariga, T., & Hamano, M. (1990). Radical scavenging action and its mode in procyanidins B-1 and B-3 from azuki beans to peroxyl radicals. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry, 54(10), 2499–2504. [CrossRef]

- Hagerman, A. E., Riedl, K. M., Jones, G. A., Sovik, K. N., Ritchard, N. T., Hartzfeld, P. W., & Riechel, T. L. (1998). High molecular weight plant polyphenolics (tannins) as biological antioxidants. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 46(5), 1887–1892. [CrossRef]

- Close, D. C., & McArthur, C. (2002). Rethinking the role of many plant phenolics – protection from photodamage not herbivores? Oikos, 99(1), 166–172. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M. M., Björn, L. O., Bornman, J. F., Flint, S. D., Kulandaivelu, G., Teramura, A. H., & Tevini, M. (1998). Effects of increased solar ultraviolet radiation on terrestrial ecosystems. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 46(1), 40–52. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. S., & Tuteja, N. (2010). Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 48(12), 909–930. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. S., Anjum, N. A., Gill, R., Jha, M., & Tuteja, N. (2015). DNA damage and repair in plants under ultraviolet and ionizing radiations. The Scientific World Journal, 2015, 250158. [CrossRef]

- Mao, K., Yuan, Z., Zuo, Z., Xu, T., Shen, X., & Gao, C. (2019). Changes in global cloud cover based on remote sensing data from 2003 to 2012. Chinese Geographical Science, 29(2), 306–315. [CrossRef]

- Ballaré, C. L., Caldwell, M. M., Flint, S. D., Robinson, S. A., & Bornman, J. F. (2011). Effects of solar ultraviolet radiation on terrestrial ecosystems. Patterns, mechanisms, and interactions with climate change. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences: Official Journal of the European Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobiology, 10(2), 226–241. [CrossRef]

- Bornman, J. F., Barnes, P. W., Robinson, S. A., Ballaré, C. L., Flint, S. D., & Caldwell, M. M. (2015). Solar ultraviolet radiation and ozone depletion-driven climate change: effects on terrestrial ecosystems. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences: Official Journal of the European Photochemistry Association and the European Society for Photobiology, 14(1), 88–107. [CrossRef]

- Aleixandre-Tudo, J. L., Buica, A., Nieuwoudt, H., Aleixandre, J. L., & du Toit, W. (2017). Spectrophotometric analysis of phenolic compounds in grapes and wines. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 65(20), 4009–4026. [CrossRef]

- Jaakola, L., & Hohtola, A. (2010). Effect of latitude on flavonoid biosynthesis in plants. Plant, Cell & Environment, 33(8), 1239–1247. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Kubota, C. (2009). Effects of supplemental light quality on growth and phytochemicals of baby leaf lettuce. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 67(1), 59–64. [CrossRef]

- Iwai, M., Ohta, M., Tsuchiya, H., & Suzuki, T. (2010). Enhanced accumulation of caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid and luteolin-glucoside in red perilla cultivated under red diode laser and blue LED illumination followed by UV-A irradiation. Journal of Functional Foods, 2(1), 66–70. [CrossRef]

- Bantis, F., Ouzounis, T., & Radoglou, K. (2016). Artificial LED lighting enhances growth characteristics and total phenolic content of Ocimum basilicum, but variably affects transplant success. Scientia Horticulturae, 198, 277–283. [CrossRef]

- Tsormpatsidis, E., Henbest, R. G. C., Davis, F. J., Battey, N. H., Hadley, P., & Wagstaffe, A. (2008). UV irradiance as a major influence on growth, development and secondary products of commercial importance in Lollo Rosso lettuce ‘Revolution’ grown under polyethylene films. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 63(1), 232-239. [CrossRef]

- Otieno, B. A. (2017). Genetic and Environmental Influences on Utilisation of Eucalyptus camaldulensis (Dehnh.) by Leptocybe invasa Fisher & LaSalle (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae). PhD Thesis, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. [CrossRef]

- Otieno, B. A., Salminen, J.-P., & Steinbauer, M. J. (2022). Resistance of subspecies of Eucalyptus camaldulensis to galling by Leptocybe invasa: Could quinic acid derivatives be responsible for leaf abscission and reduced galling? Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 24(2), 167-177. [CrossRef]

- Pinkard, E., Gill, W., & Mohammed, C. (2006). Physiology and anatomy of lenticel-like structures on leaves of Eucalyptus nitens and Eucalyptus globulus seedlings. Tree Physiology, 26(8), 989–999. [CrossRef]

- Close, D. C., McArthur, C., Hagerman, A. E., Davies, N. W., & Beadle, C. L. (2007). Phenolic acclimation to ultraviolet-A irradiation in Eucalyptus nitens seedlings raised across a nutrient environment gradient. Photosynthetica, 45(1), 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, A., Bouhlel, I., Skandrani, I., Valenti, K., Kadri, M., Guiraud, P., Steiman, R., Mariotte, A. M., Ghedira, K., Laporte, F., Dijoux-Franca, M. G., & Chekir-Ghedira, L. (2007). Study of antimutagenic and antioxidant activities of gallic acid and 1,2,3,4,6-pentagalloylglucoes from Pistacia lentiscus -: Confirmation by microarray expression profiling. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 165(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi, R., Mori, T., & Saito, K. (2014). Alternation of flavonoid accumulation under drought stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signalling & Behaviour, 9(8), e29518. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U., & Oba, S. (2018). Drought stress enhances nutritional and bioactive compounds, phenolic acids and antioxidant capacity of Amaranthus leafy vegetable. BMC Plant Biology, 18. [CrossRef]

- Close, D. C., Davies, N. W., & Beadle, C. L. (2001). Temporal variation of tannins (galloylglucoses), flavonols and anthocyanins in leaves of Eucalyptus nitens seedlings: implications for light attenuation and antioxidant activities. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology, 28(4), 269-278. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.-W., Xu, M., Li, Y., Li, X.-Y., Wang, D., Zhu, H.-T., Yang, C.-R., & Zhang, Y.-J. (2012). Phenolic compounds from the branches of Eucalyptus maideni. Chemistry & Biodiversity, 9(1), 123-130. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K. G., Swinny, E. E., Markham, K. R., & Winefield, C. (2002). Flavonoid gene expression and UV photoprotection in transgenic and mutant Petunia leaves. Phytochemistry, 59(1), 23–32. [CrossRef]

- Agati, G., & Tattini, M. (2010). Multiple functional roles of flavonoids in photoprotection. New Phytologist, 186(4), 786–793. [CrossRef]

- Shourie, A., Tomar, P., Srivastava, D., & Chauhan, R. (2014). Enhanced biosynthesis of quercetin occurs as a photoprotective measure in Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. under acute UV-B exposure. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 57(3), 317-325. [CrossRef]

- Agati, G., Matteini, P., Goti, A., & Tattini, M. (2007). Chloroplast-located flavonoids can scavenge singlet oxygen. New Phytologist, 174(1), 77-89. [CrossRef]

- Bielczynski, L. W., Łącki, M. K., Hoefnagels, I., Gambin, A., & Croce, R. (2017). Leaf and plant age affect photosynthetic performance and photoprotective capacity. Plant Physiology, 175(4), 1634–1648. [CrossRef]

- Farnier, K., & Steinbauer, M. J. (2016). Elevated anthocyanins protect young Eucalyptus leaves from high irradiance but also indicate foliar nutritional quality to visually attuned psyllids. Ecological Entomology, 41(2), 168-181. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. J., & Crowden, R. K. (1974). Anthocyanins in some Eucalyptus species. Australian Journal of Botany, 22(3), 623-627. [CrossRef]

- McArthur, C., Loney, P. E., Davies, N. W., & Jordan, G. J. (2010). Early ontogenetic trajectories vary among defence chemicals in seedlings of a fast-growing eucalypt. Austral Ecology, 35(2), 157-166. [CrossRef]

- Goodger, J. Q. D., Heskes, A. M., & Woodrow, I. E. (2013). Contrasting ontogenetic trajectories for phenolic and terpenoid defences in Eucalyptus froggattii. Annals of Botany, 112(4), 651–659. [CrossRef]

- Close, D., McArthur, C., Paterson, S., Fitzgerald, H., Walsh, A., & Kincade, T. (2003). Photoinhibition: a link between effects of the environment on eucalypt leaf chemistry and herbivory. Ecology, 84(11), 2952-2966. [CrossRef]

- Luo, H., Li, W., Zhang, X., Deng, S., Xu, Q., Hou, T., Pang, X., Zhang, Z., & Zhang, X. (2019). In planta high levels of hydrolysable tannins inhibit peroxidase mediated anthocyanin degradation and maintain abaxially red leaves of Excoecaria cochinchinensis. BMC Plant Biology, 19(1), 315. [CrossRef]

- Wam, H. K., Stolter, C., & Nybakken, L. (2017). Compositional changes in foliage phenolics with plant age, a natural experiment in boreal forests. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 43(9), 920–928. [CrossRef]

- Holly, C., Laughlin, G. P., & Ball, M. C. (1994). Cold-induced photoinhibition and design of shelters for establishment of eucalypts in pastures. Australian Journal of Botany, 42(2), 139-147. [CrossRef]

- Steinbauer, M. J., Burns, A. E., Hall, A., Riegler, M., & Taylor, G. S. (2014). Nutritional enhancement of leaves by a psyllid through senescence-like processes: insect manipulation or plant defence? Oecologia, 176(4), 1061-1074. [CrossRef]

- Steinbauer, M. J., Salminen, J.-P., & Watson, S. J. (2018). Yellow, red, dead: the nutritional consequences for Cardiaspina densitexta (Hemiptera: Aphalaridae) nymphs of inducing senescence in old Eucalyptus fasciculosa leaves. Austral Entomology, 57(2), 265-278. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M. W., Brooker, M. I. H., & Butcher, P. A. (2009). A taxonomic revision of Eucalyptus camaldulensis (Myrtaceae). Australian Systematic Botany, 22(4), 257-285. [CrossRef]

- James, S. A., & Bell, D. T. (1995). Morphology and anatomy of leaves of Eucalyptus camaldulensis clones: Variation between geographically separated locations. Australian Journal of Botany, 43(4), 415–433. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, S., McEvoy, R., Baldwin, D. S., Rees, G. N., Parsons, Y., & Southerton, S. (2014). Characterisation of adaptive genetic diversity in environmentally contrasted populations of Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. (River Red Gum). PLOS ONE, 9(8), e103515. [CrossRef]

- Ohmart, C. P., Thomas, J. R., & Stewart, L.G. (1984). Differential defoliation by insects among provenances of Eucalyptus delegatensis. Australian Journal of Entomology, 23(2), 105-111. [CrossRef]

- Steinbauer, M. J., & Matsuki, M. (2004). Suitability of Eucalyptus and Corymbia for Mnesampela privata (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) larvae. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 6(4), 323-332. [CrossRef]

- Henery, M. L., Henson, M., Wallis, I. R., Stone, C., & Foley, W. J. (2008). Predicting crown damage to Eucalyptus grandis by Paropsis atomaria with direct and indirect measures of leaf composition. Forest Ecology and Management, 255(10), 3642-3651. [CrossRef]

- Östrand, F., Wallis, I. R., Davies, N. W., Matsuki, M., & Steinbauer, M. J. (2008). Causes and consequences of host expansion by Mnesampela privata. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 34(2), 153-167. [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S. (2020). Use of Metabolomics to Understand Ontogenetic and Environmental Influences on the Abundance and Composition of Foliar Phenolic Compounds in Myrtaceae. PhD Thesis, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).