Submitted:

18 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Fundamentals

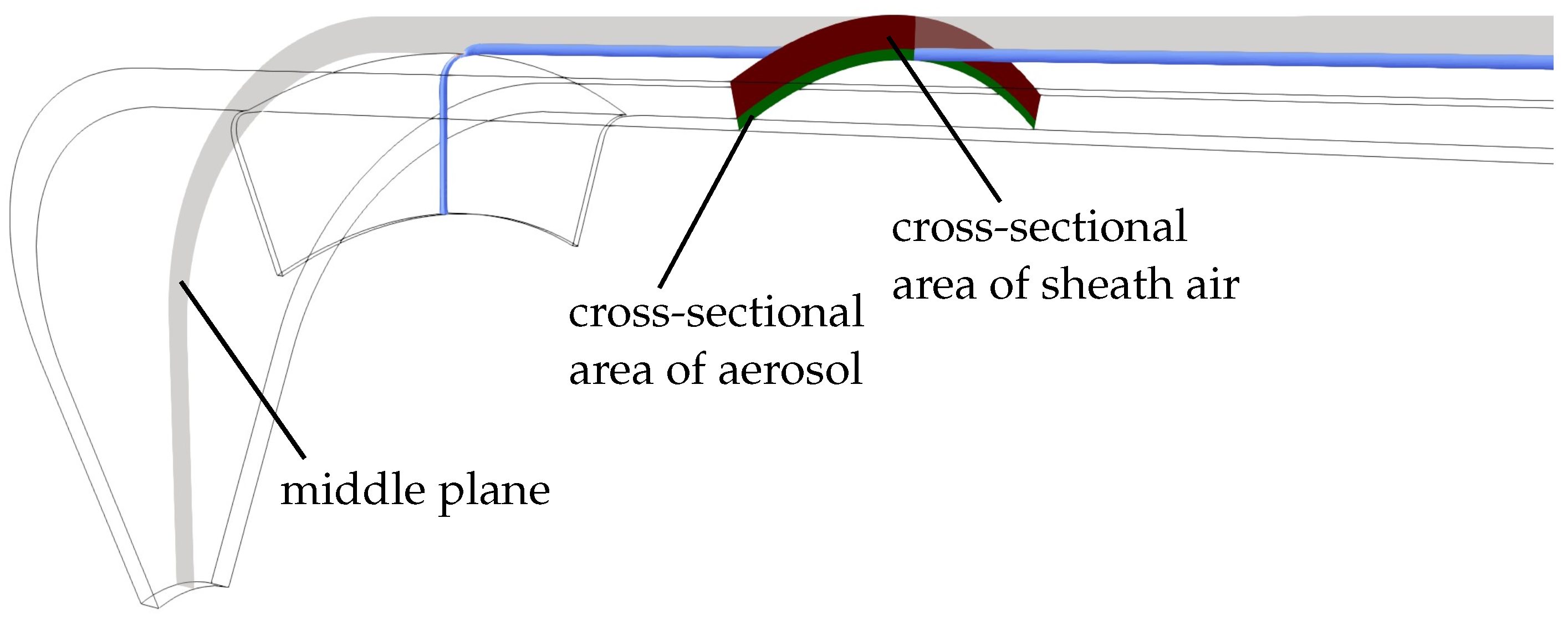

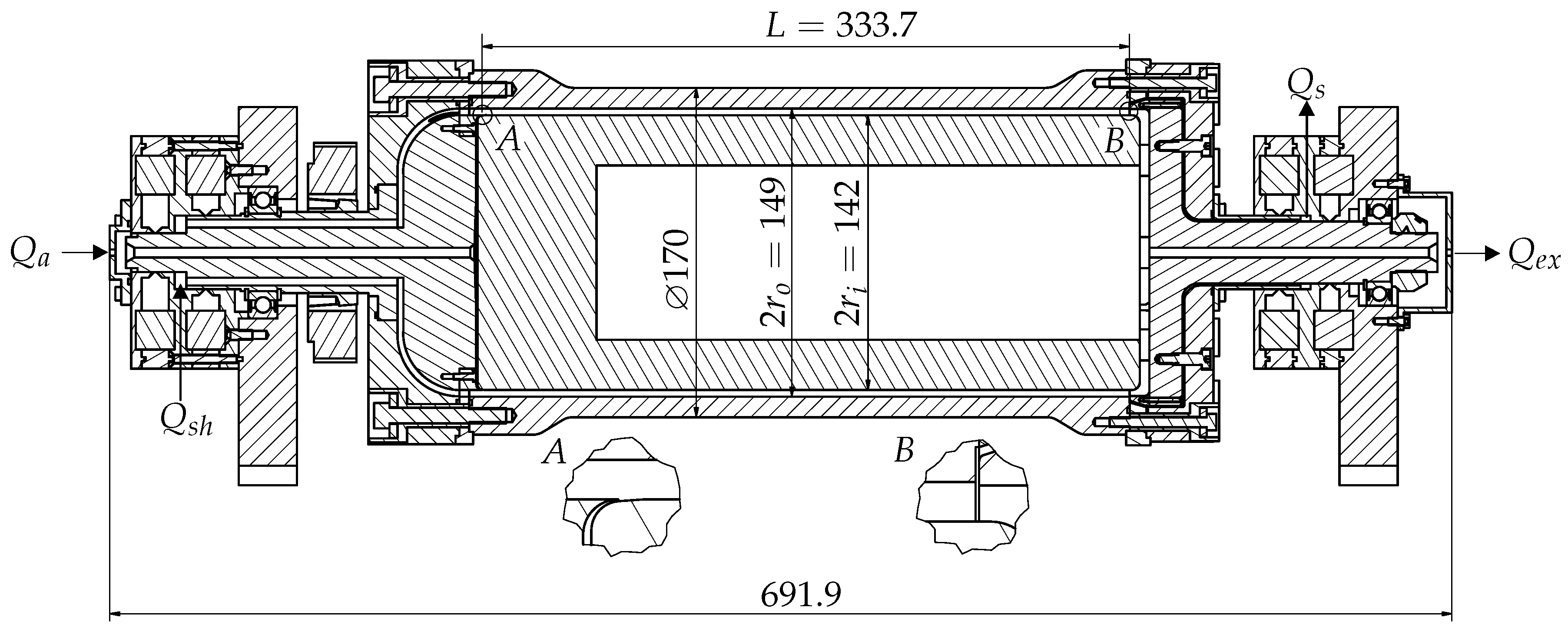

3. Design

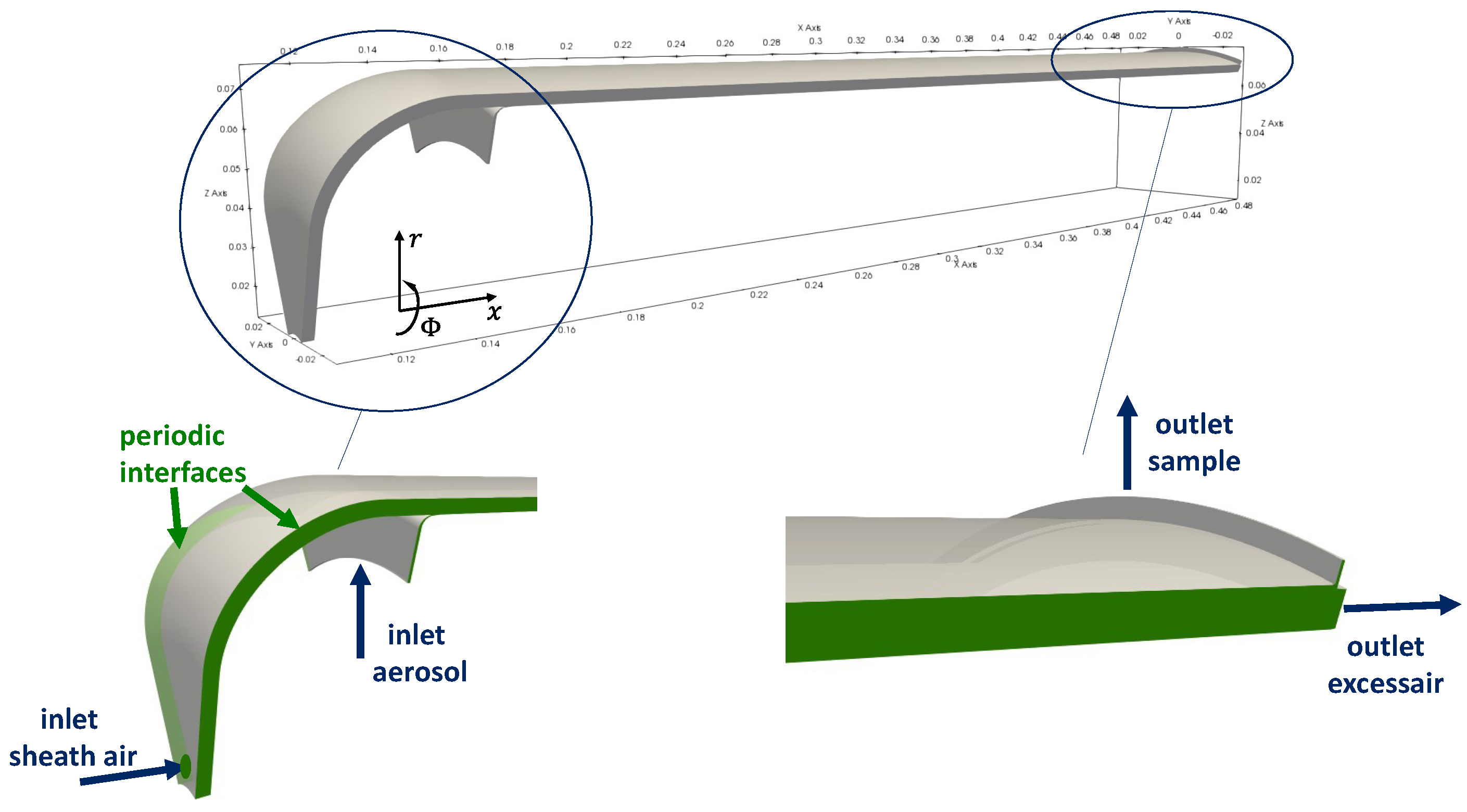

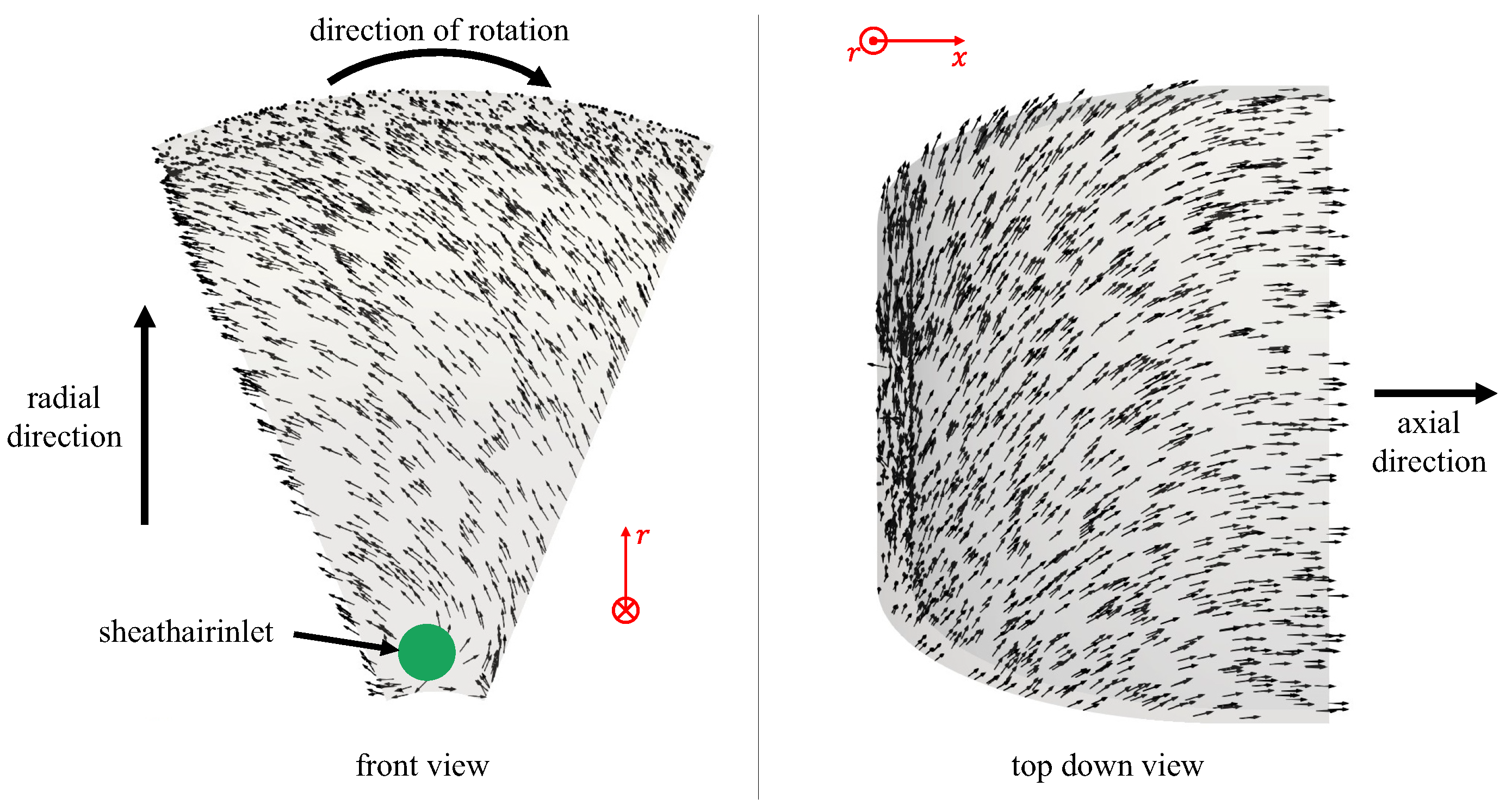

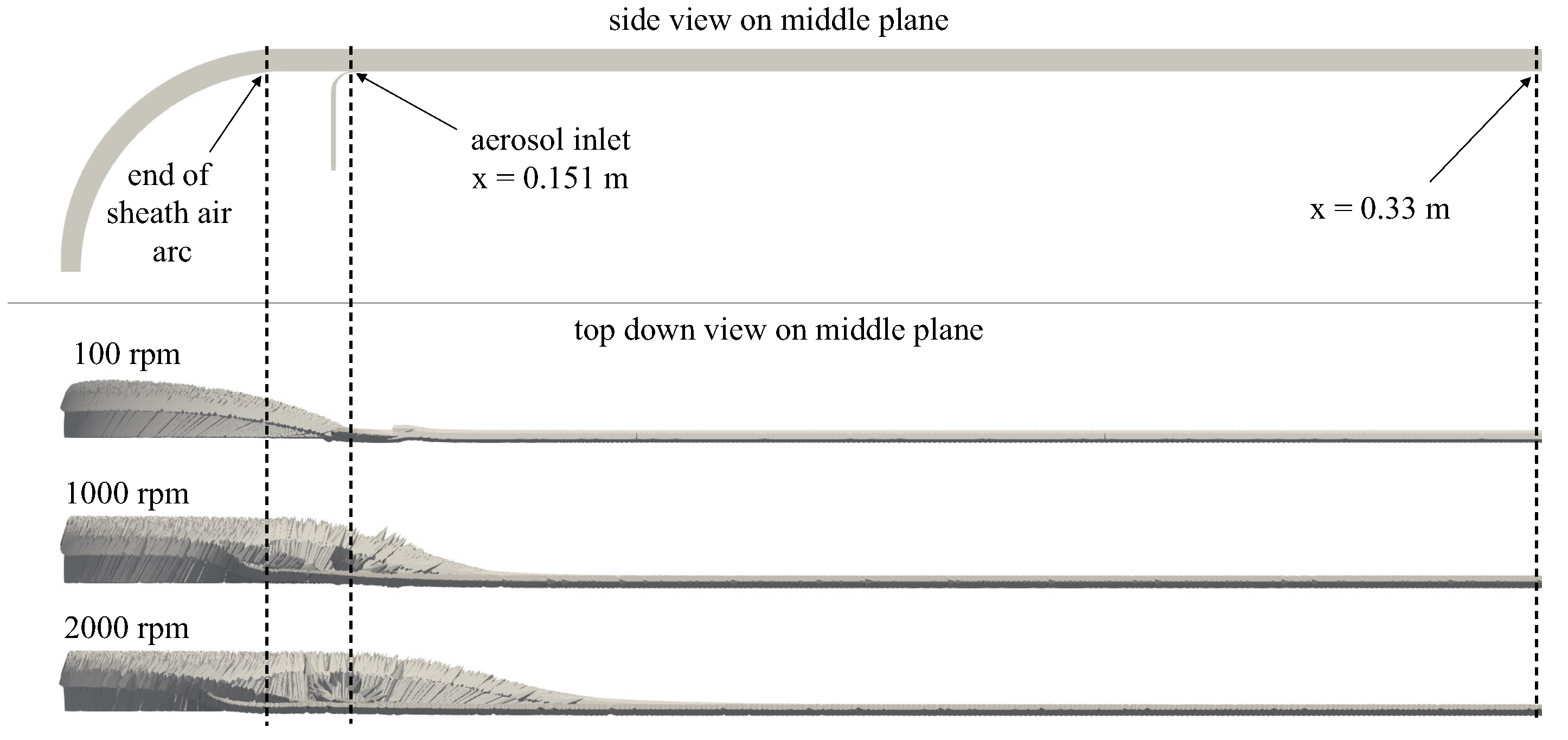

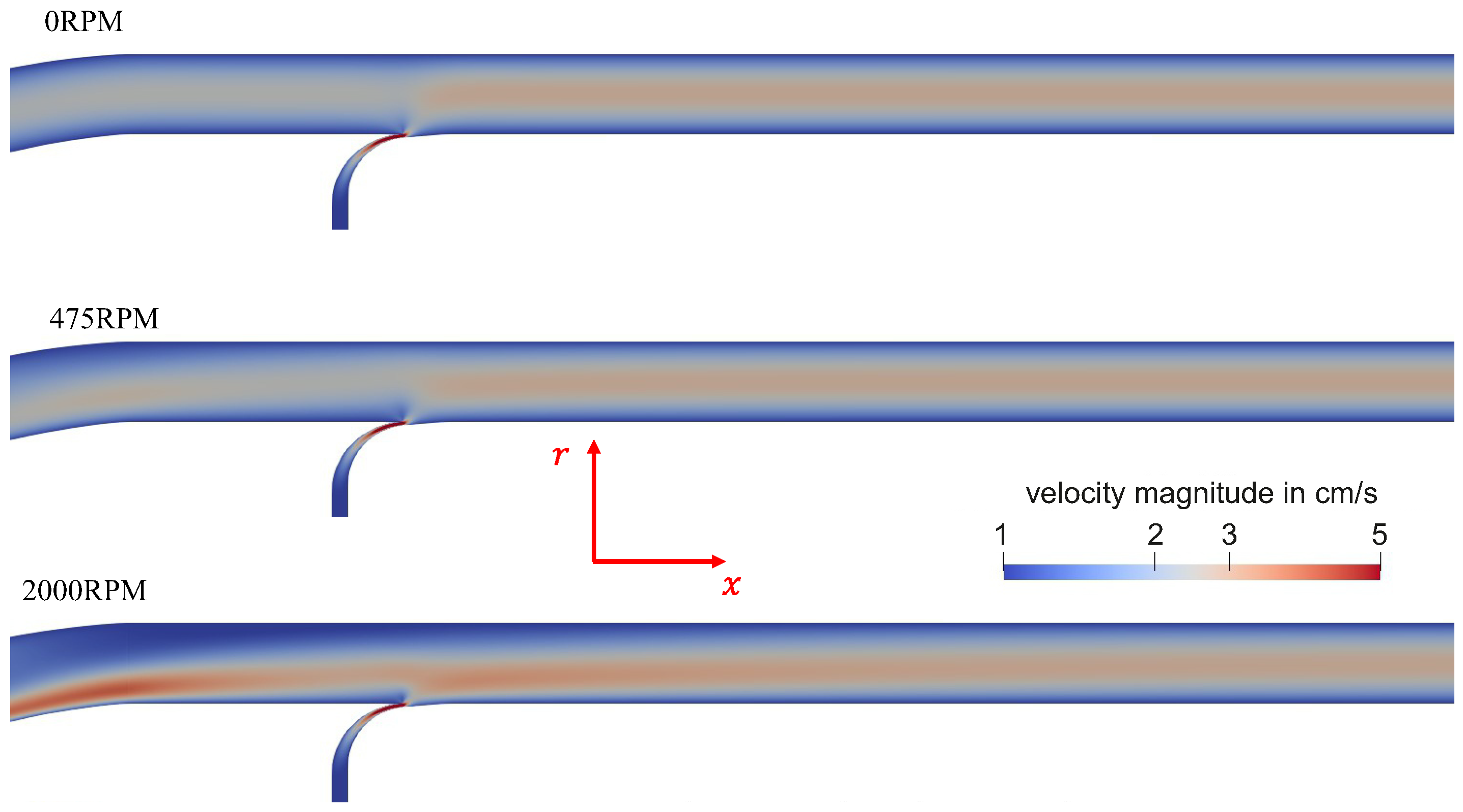

4. Numerical Flow Simulations

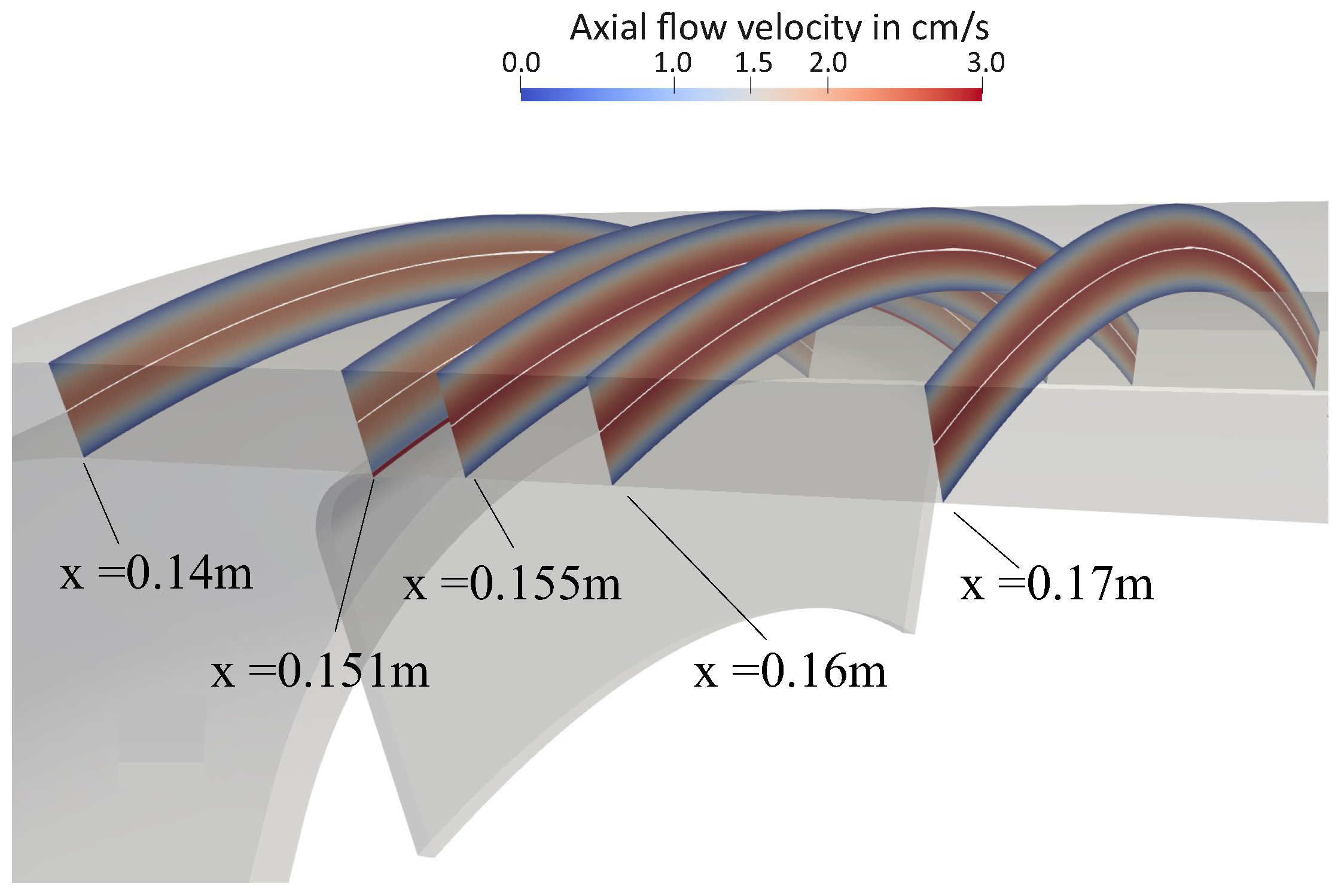

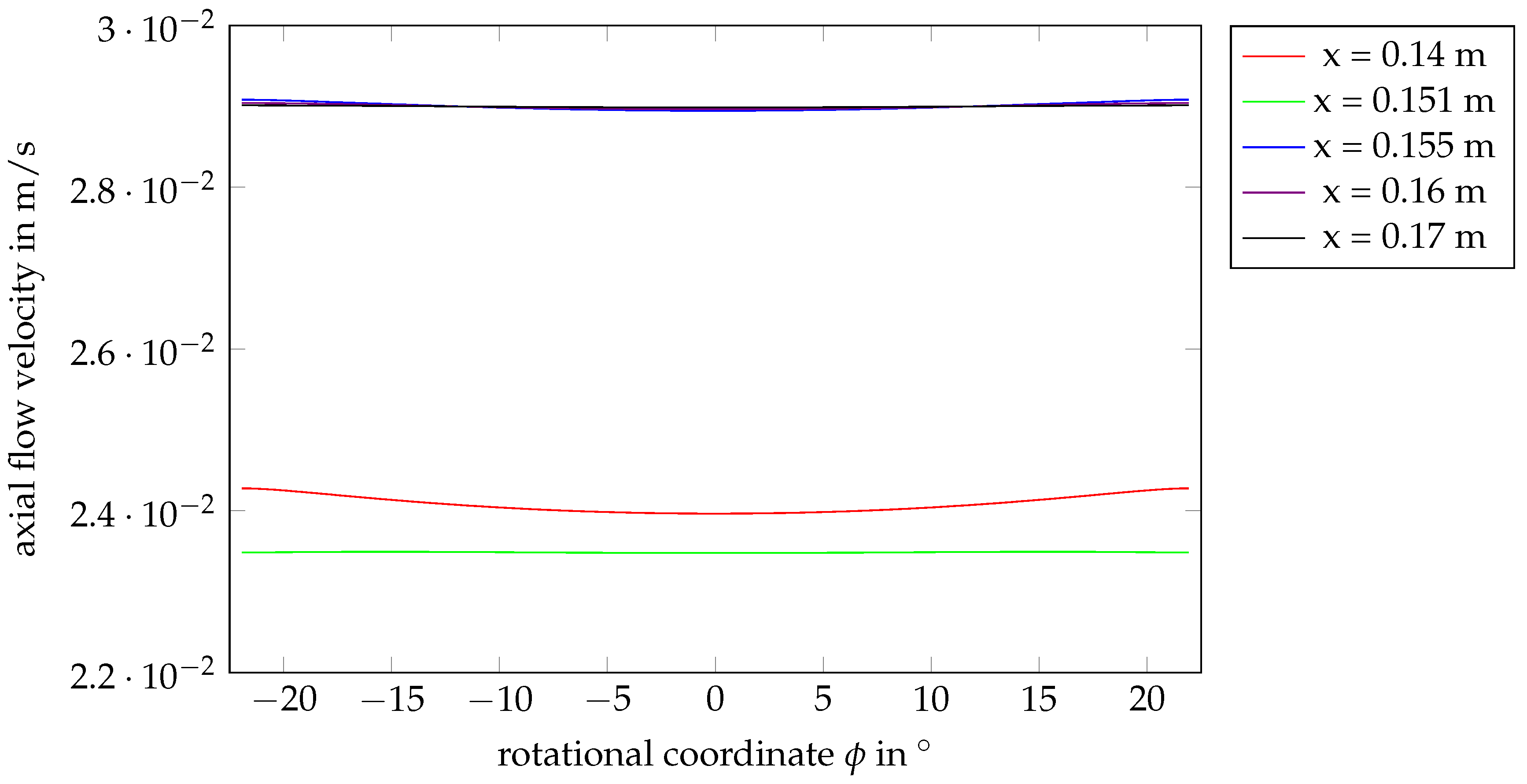

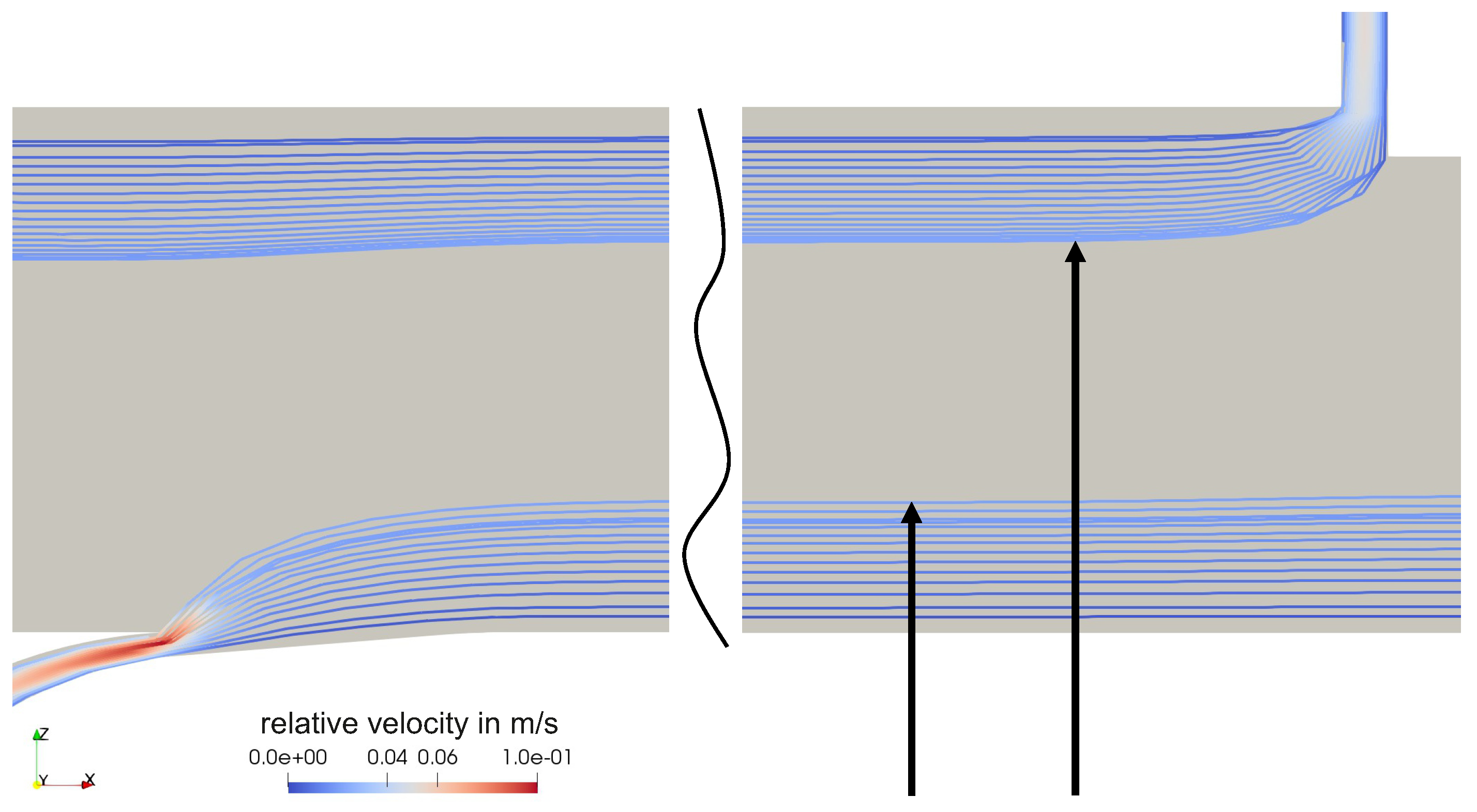

4.1. Flow Behavior Without Rotation

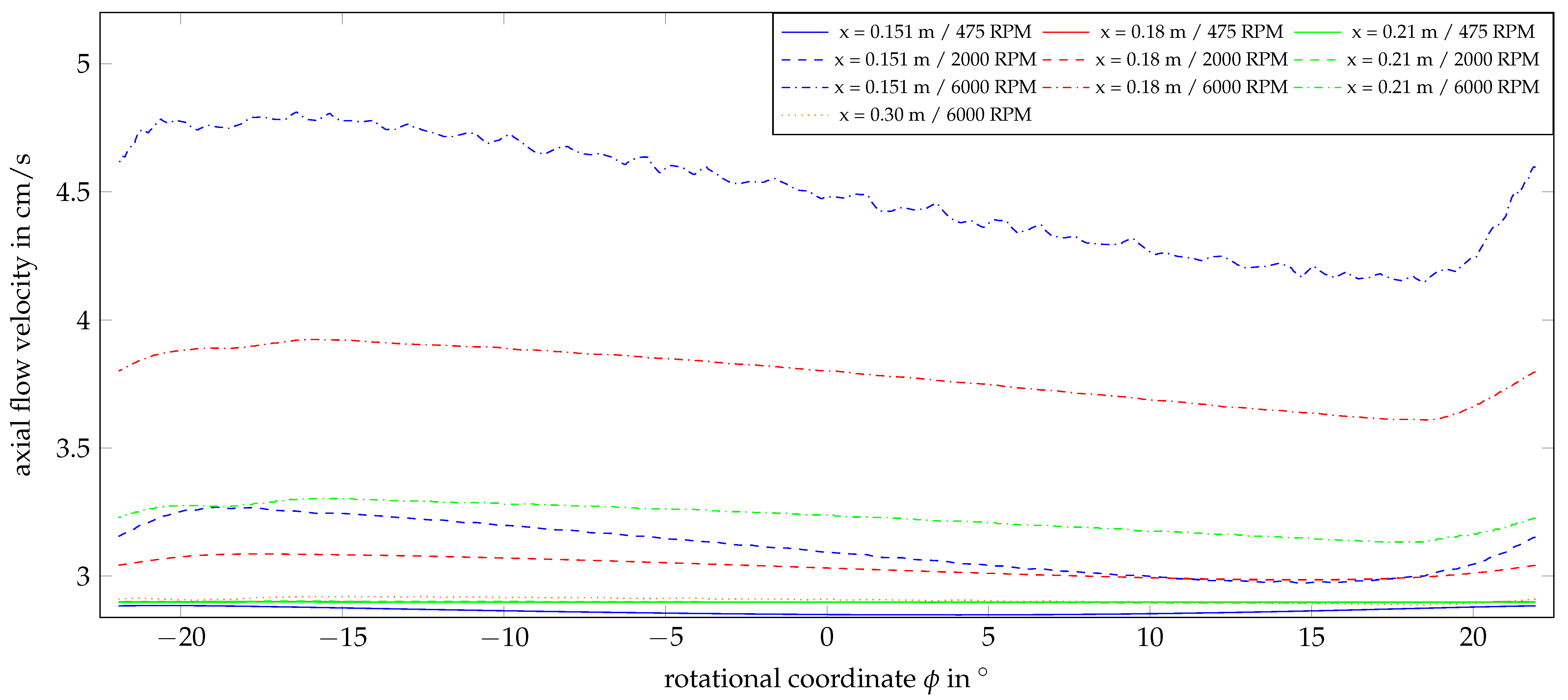

4.2. Flow Behavior with Rotation

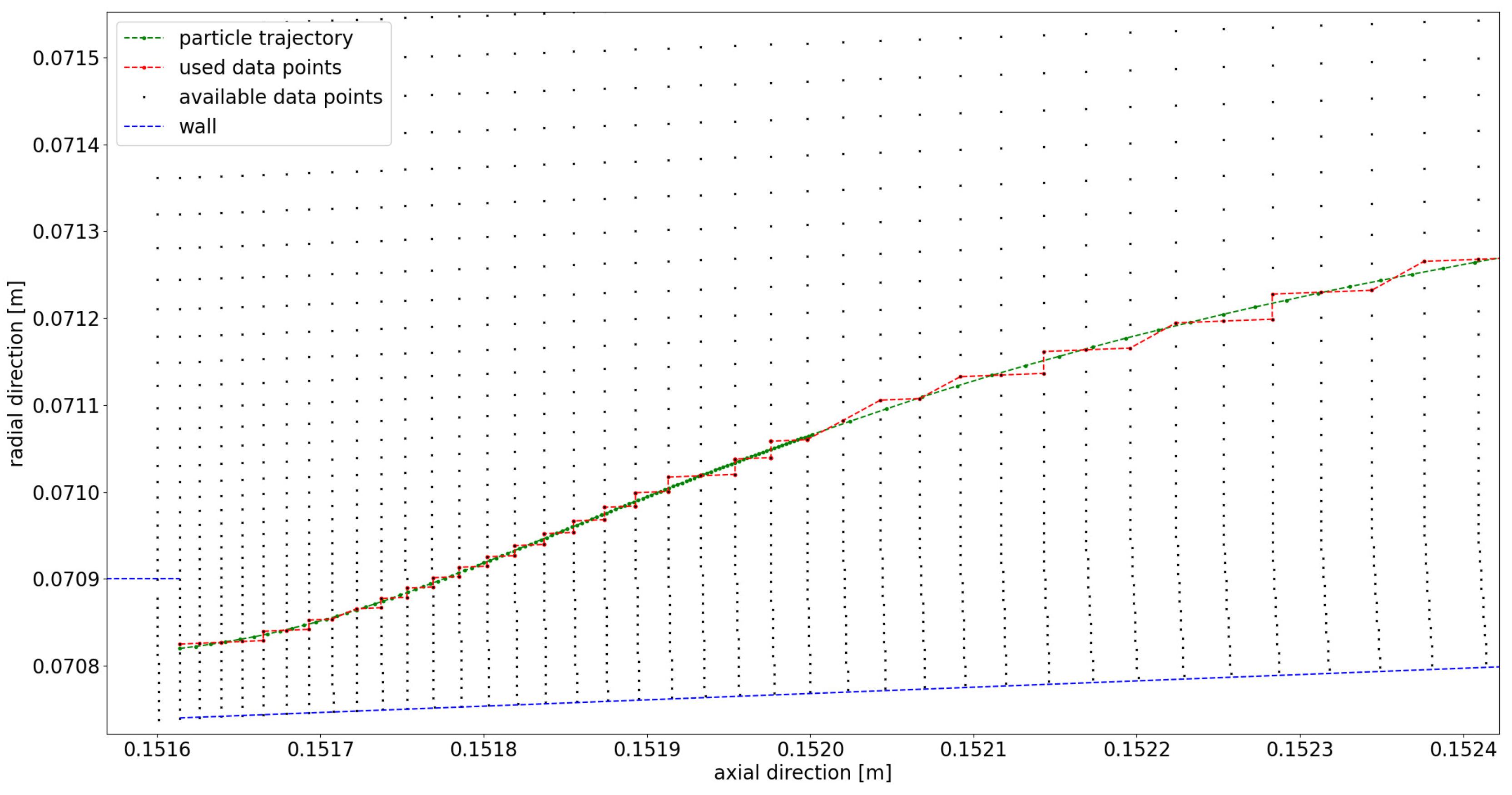

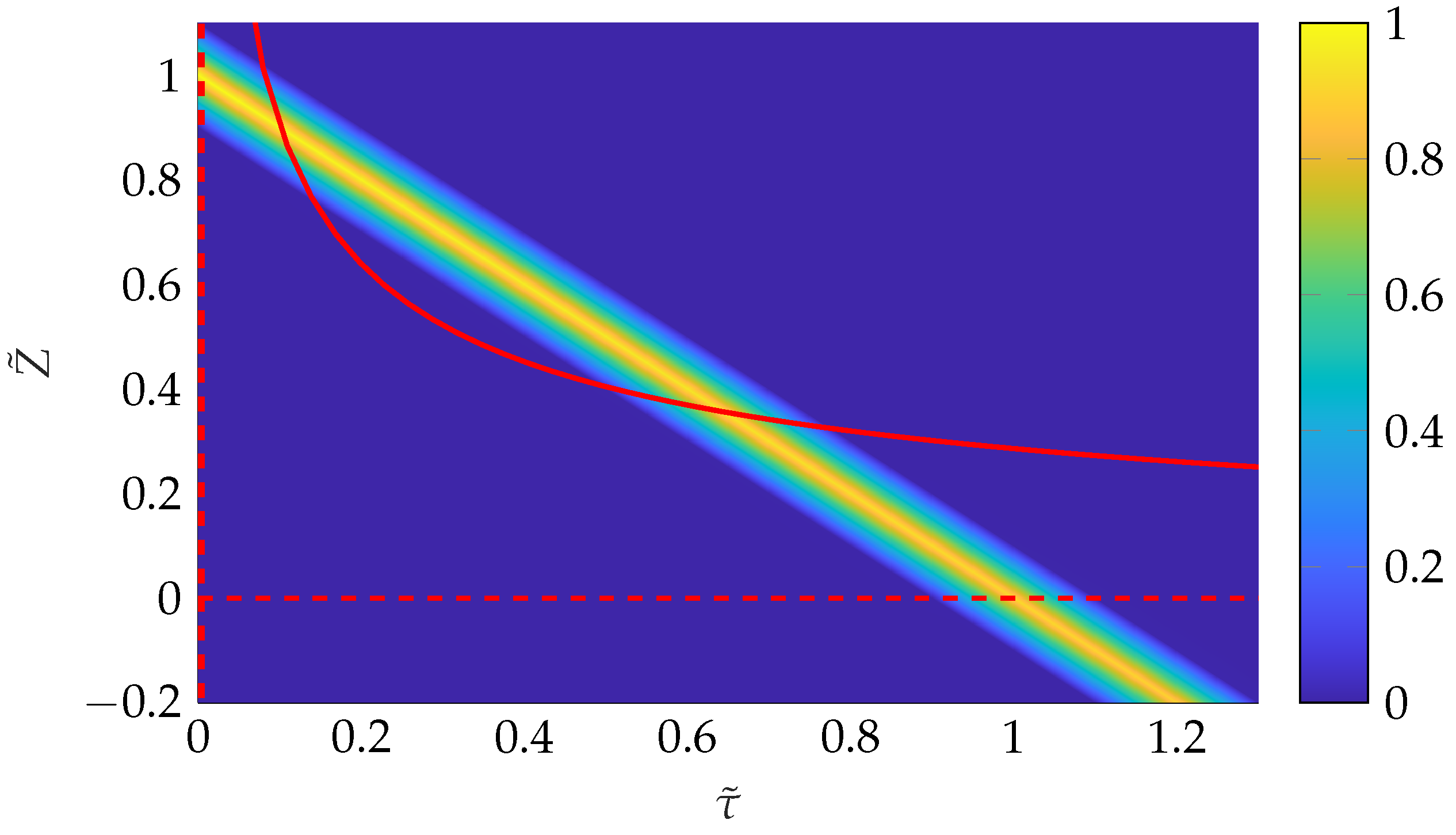

5. Derivation of Ideal Transfer Functions from the CFD Simulation

5.1. Ideal Transfer Function

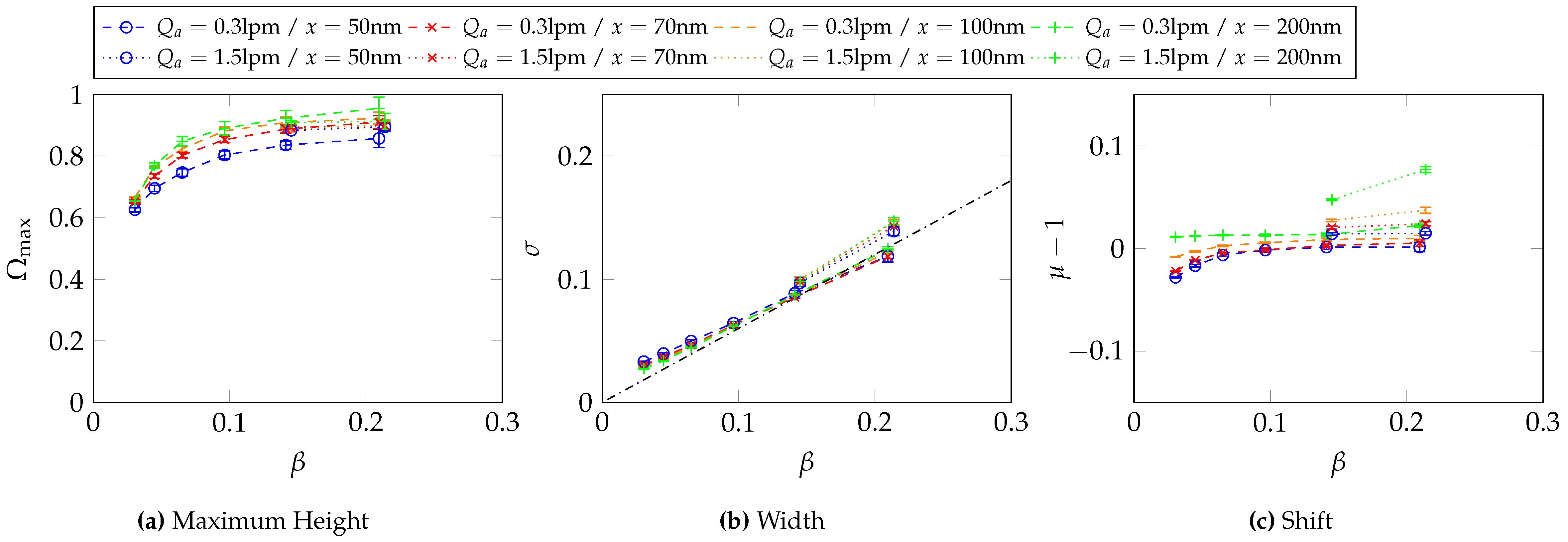

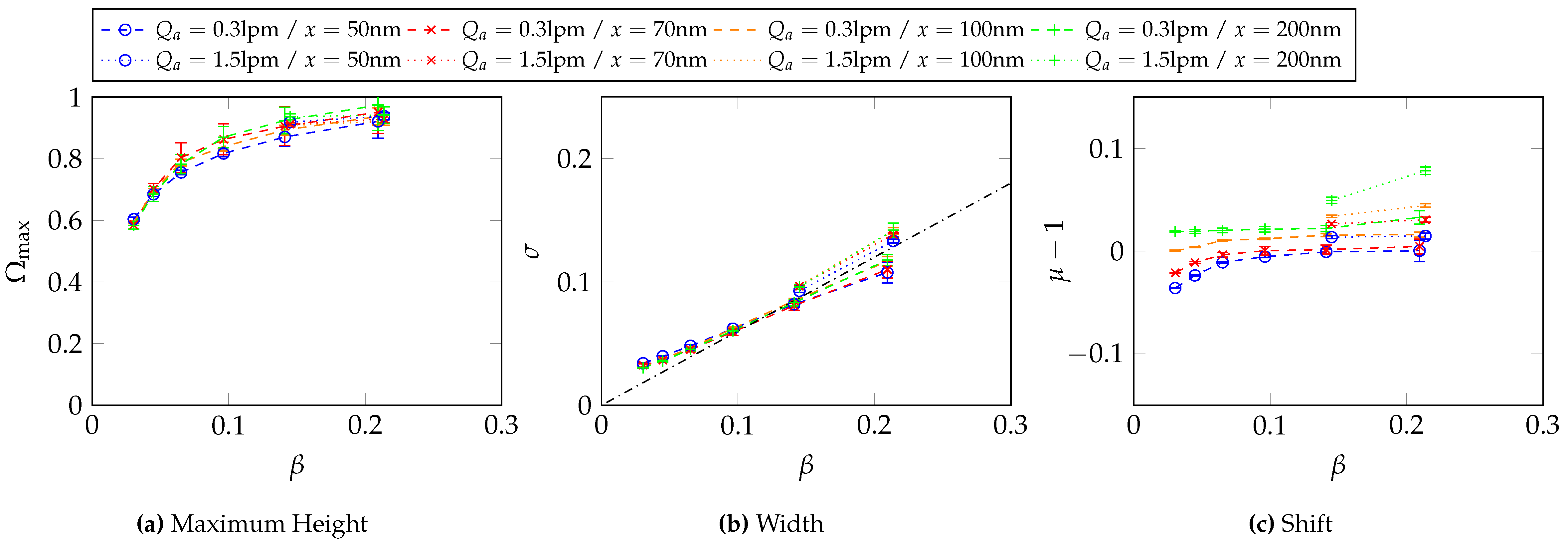

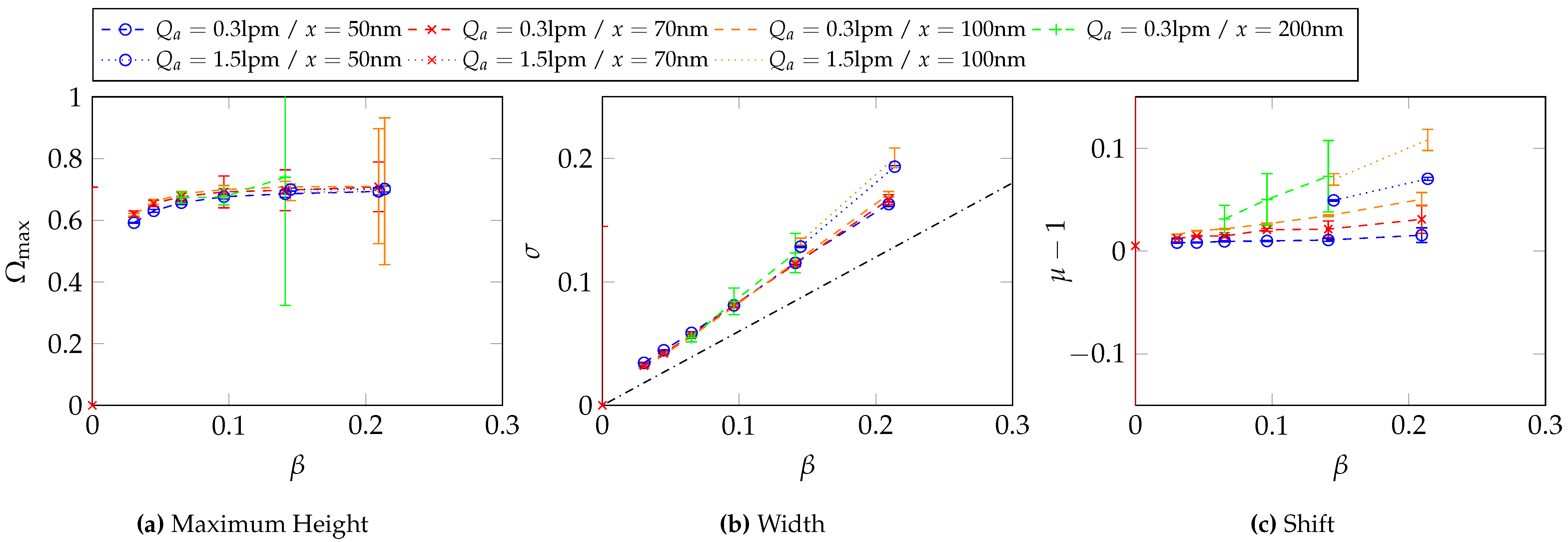

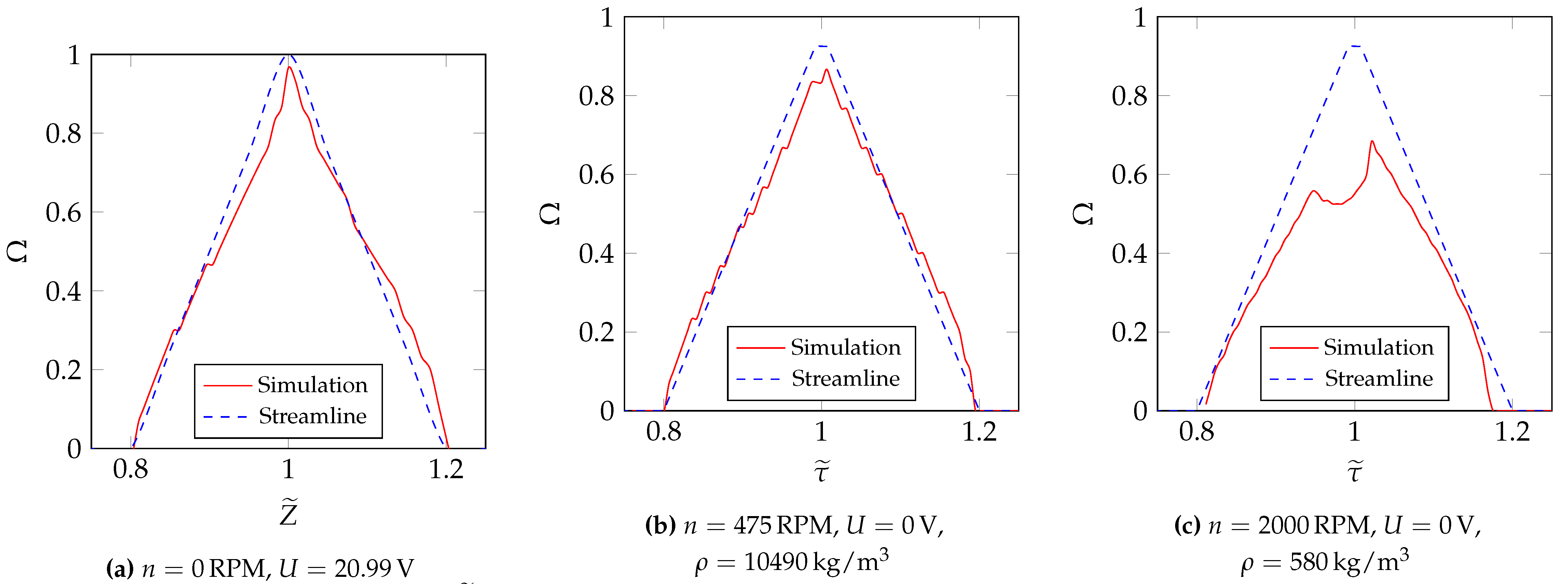

5.2. Simulated Transfer Functions for and

5.3. Simulated Transfer Functions for Different CDMA Operating Parameters

6. Measurement of Transfer Functions

6.1. Theory

6.2. Production of the Test Aerosol and Measurement Setup

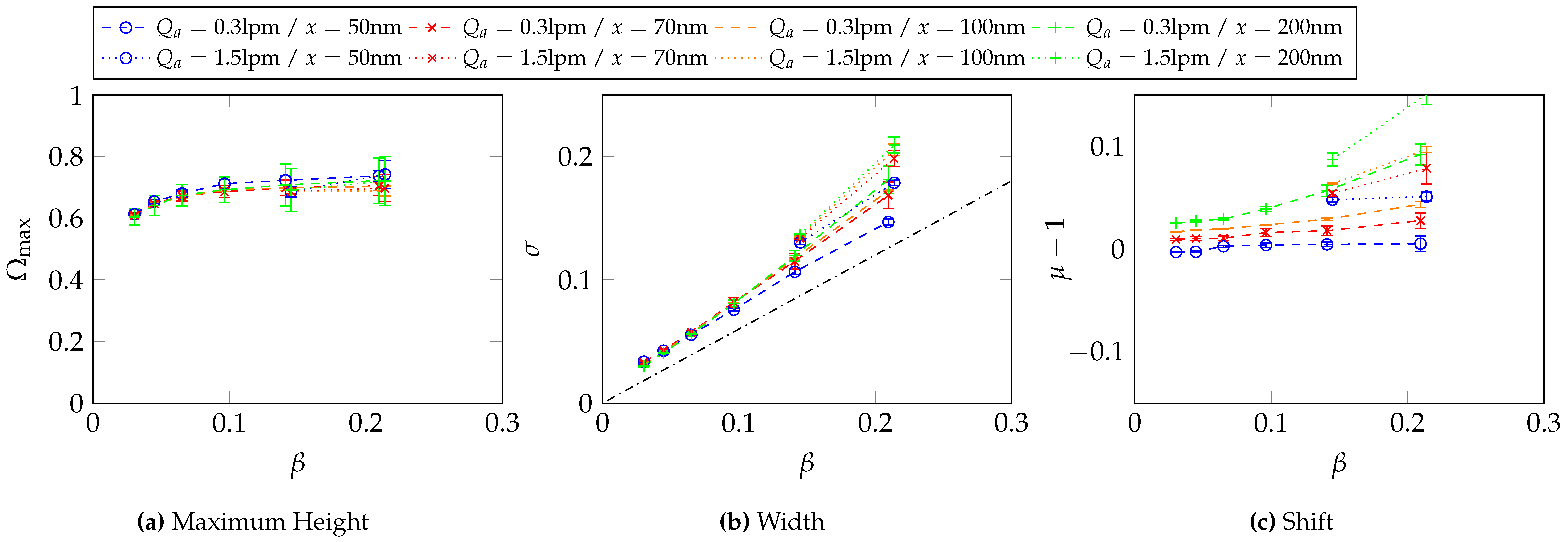

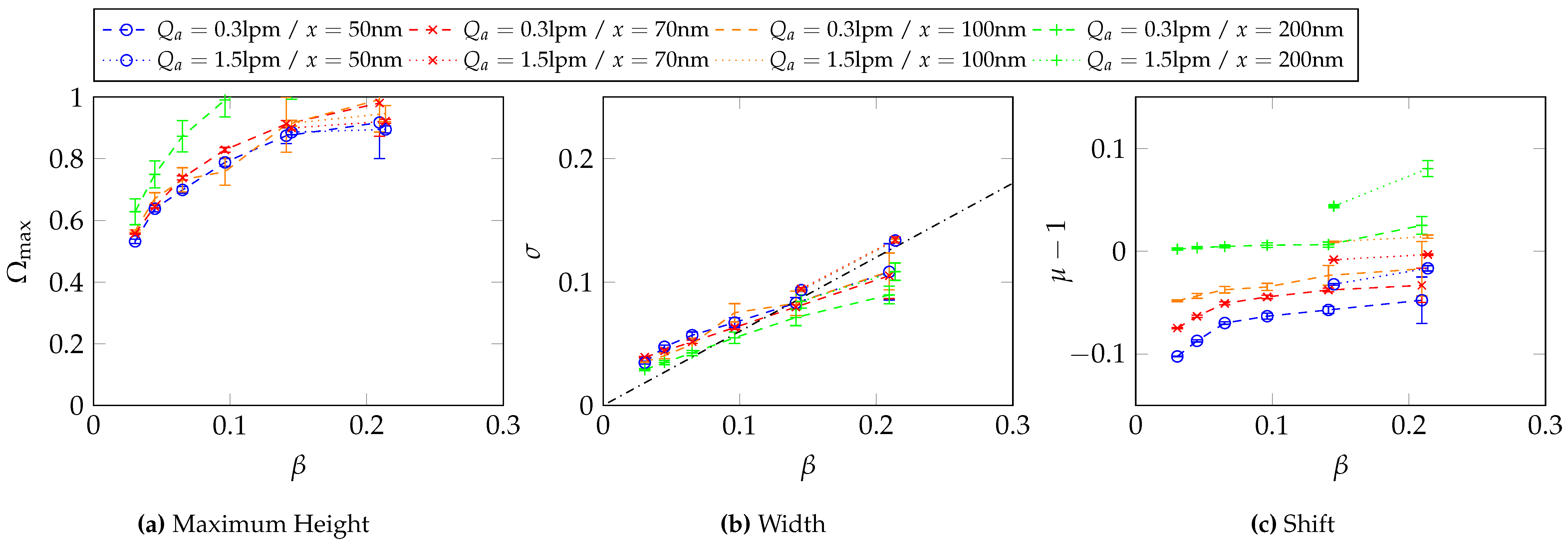

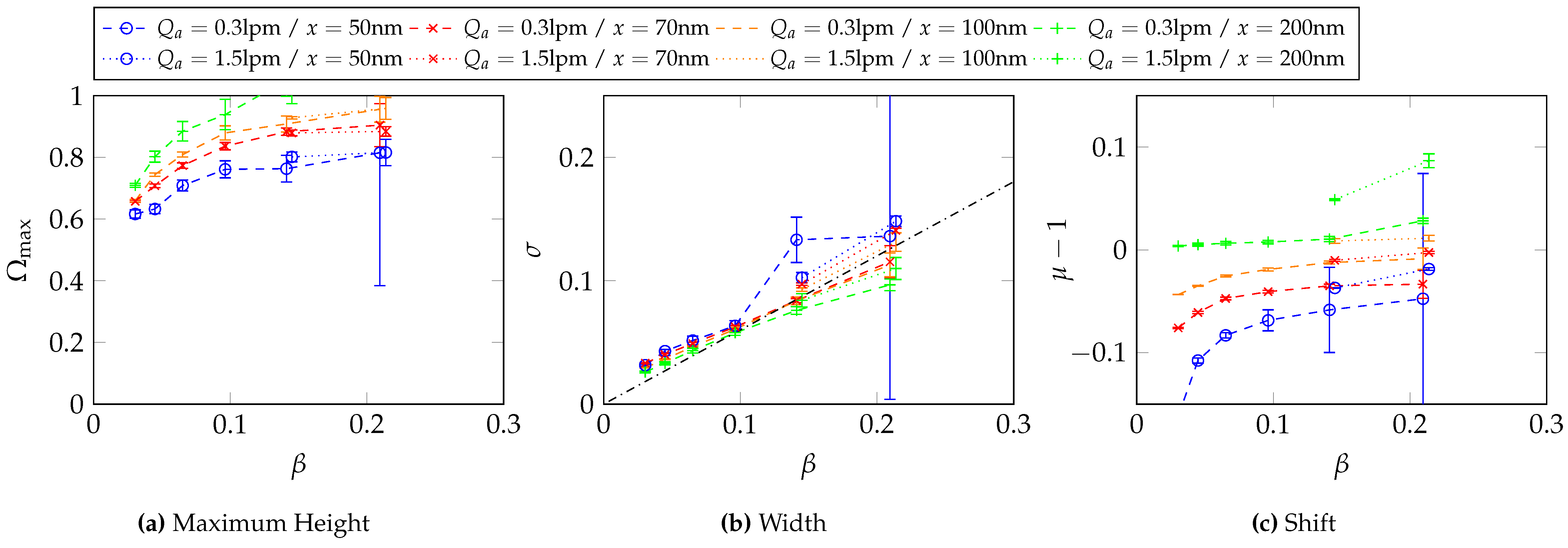

6.3. Determination of the Transfer Function Parameters for and at Different -Values

6.4. Determination of the Transfer Function Parameters for and at

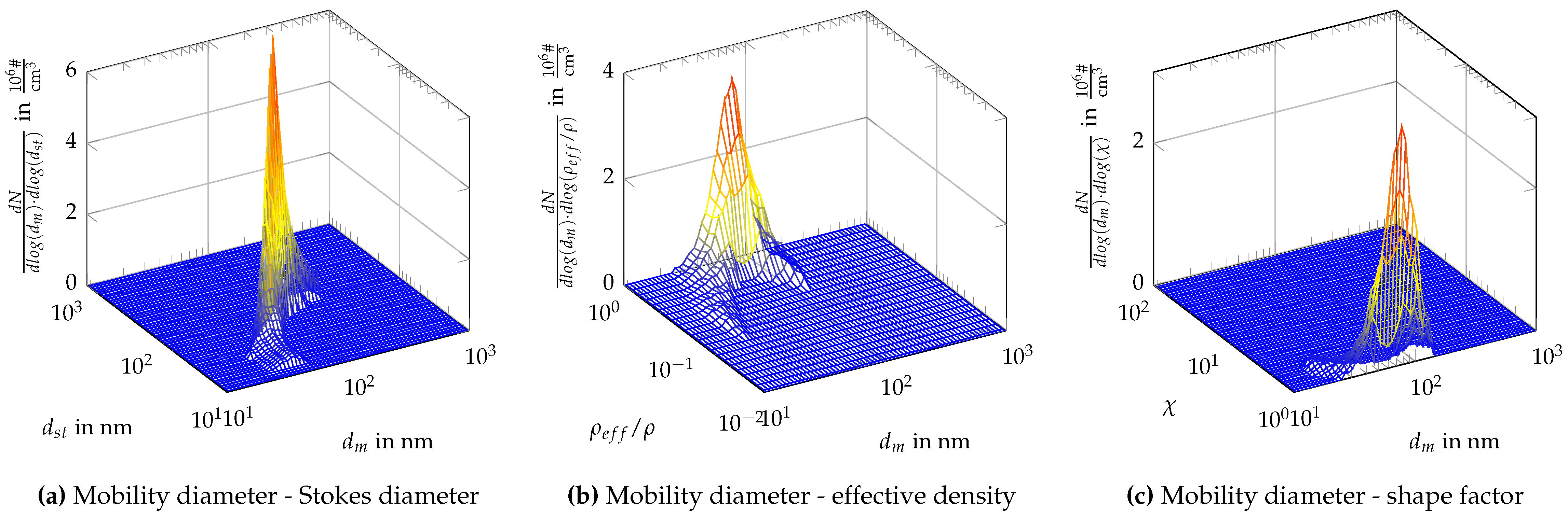

7. Measurement Results and Analysis of Two-Dimensional Size Distributions for Different Sintering Stages of Silver Nanoparticles

7.1. Production of the Aerosol and Measurement Setup for Two-Dimensional Distributions

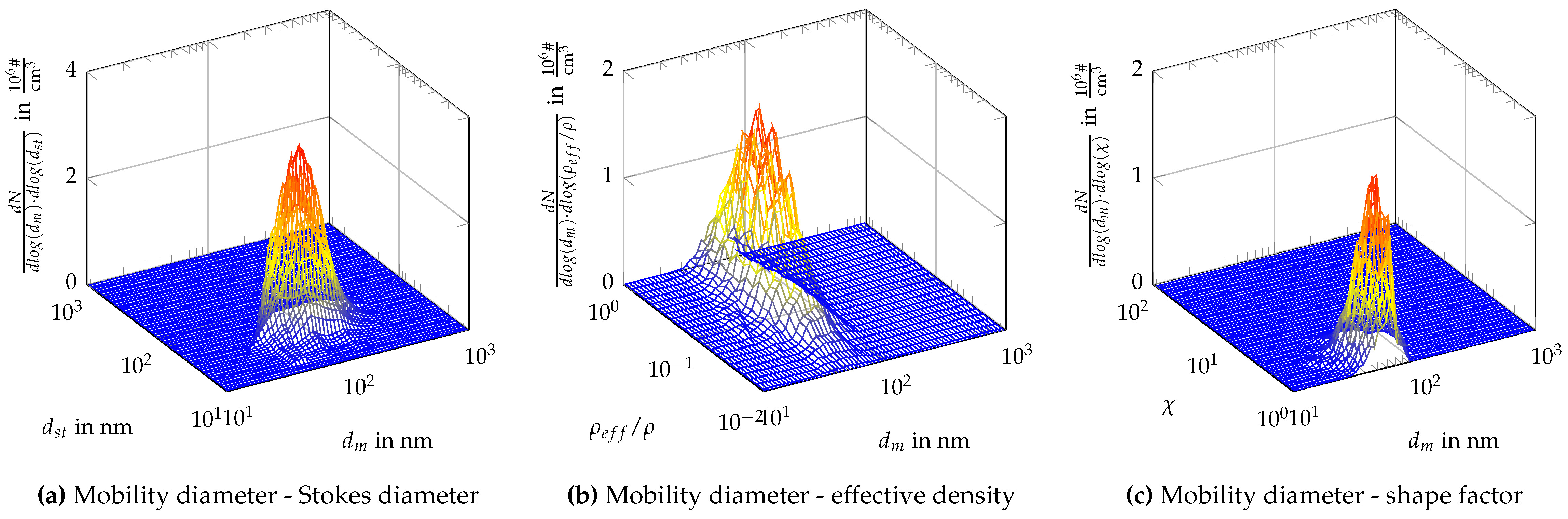

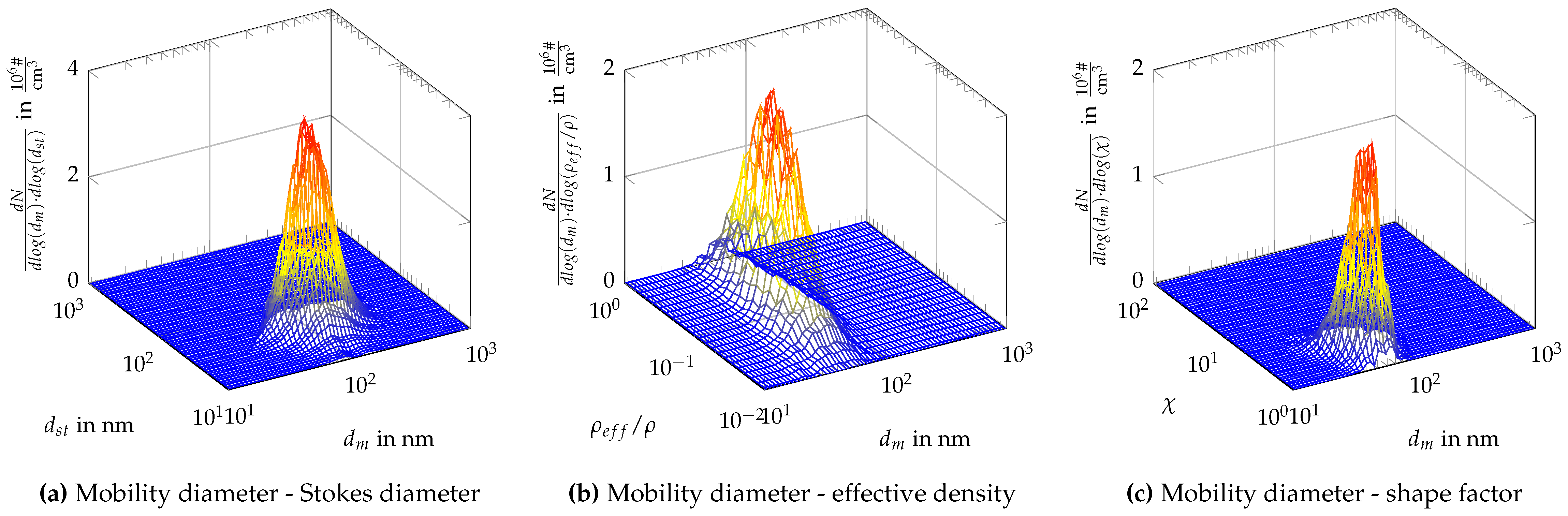

7.2. Derivation of Further Properties

7.3. Measurement Results

8. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Nomenclature

Abbreviations

| CDMA | Centrifugal Differential Mobility Analyzer |

| DMA | Differential Mobility Analyzer |

| AAC | Aerodynamic Aerosol Classifier |

| CPC | Condensation Particle Counter |

| lpm | liters per minute |

| RPM | Rounds per minute |

| MFC | Mass-flow Controller |

Nomenclature

| particle charge | |

| E | electric field |

| particle mass | |

| centrifugal acceleration | |

| dynamic viscosity | |

| n | number of particle charges |

| particle relaxation time | |

| nominal particle relaxation time | |

| normalized particle relaxation time | |

| particle mobility | |

| nominal particle mobility | |

| normalized particle mobility | |

| mobility equivalent diameter | |

| aerodynamic equivalent diameter | |

| stokes equivalent diameter | |

| volume equivalent diameter | |

| diameter of a sherical particle | |

| aerosol volume flow | |

| sheath air volume flow | |

| sample volume flow | |

| excess air volume flow | |

| L | length of the CDMA transfer path |

| inner radius | |

| maximum radius at which the particles enter | |

| outer radius of the aerosol air streamlines | |

| inner radius of the sampling air streamlines | |

| particle drift velocity | |

| y | length coordinate in axial direction |

| Cunningham slip correction factor | |

| U | voltage |

| particle density | |

| virtual assumed density of | |

| effective density | |

| angular speed | |

| transfer function | |

| ratio of to | |

| ratio of the gap width to the mean radius | |

| ratio of to | |

| total number of simulated streamlines | |

| number of sucessfully traversed streamlines | |

| fit parameters for the height of a Gaussian function | |

| fit parameters for the width of a Gaussian function | |

| fit parameters for the shift of a Gaussian function | |

| width of the transfer function | |

| shape factor |

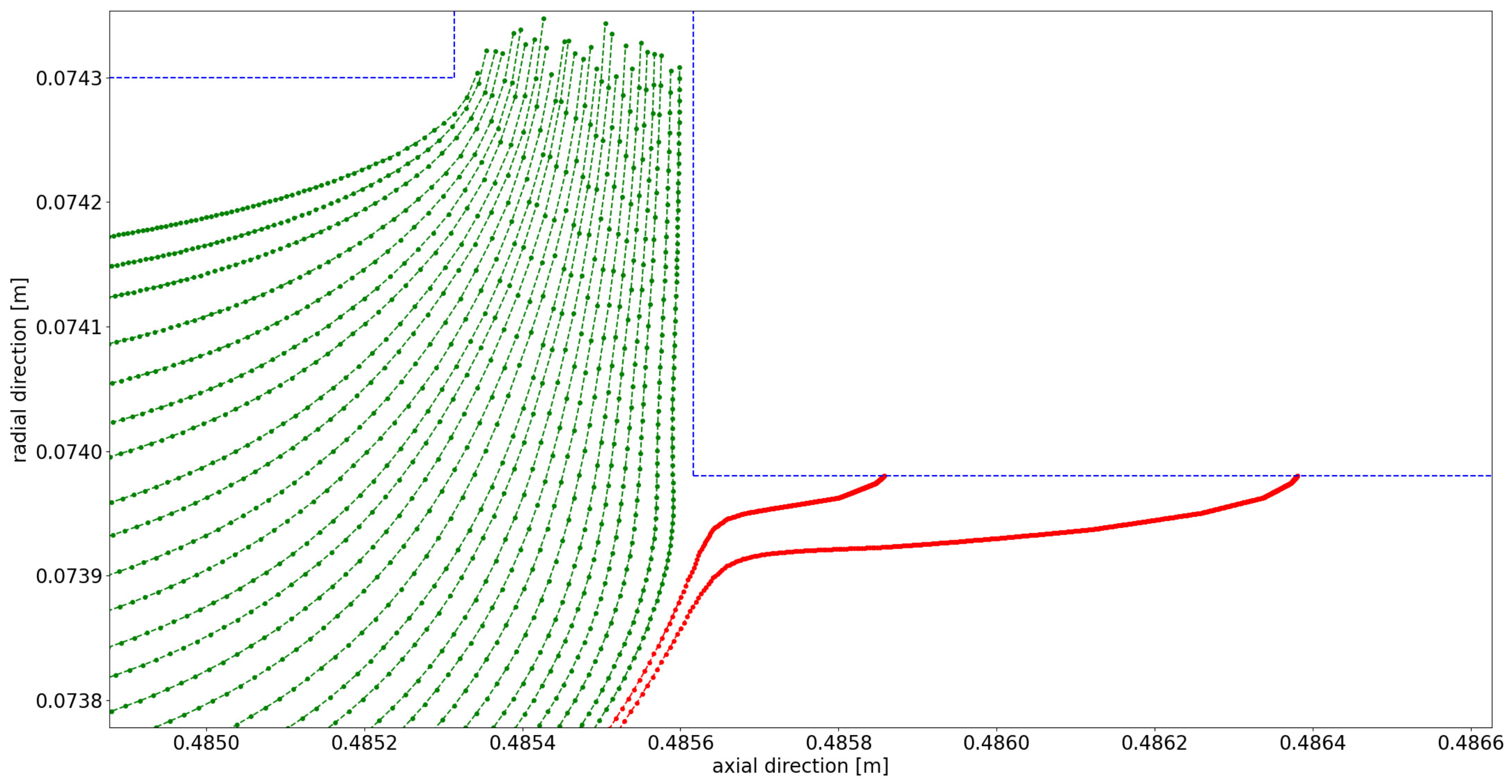

Appendix A. Further Illustration of the CFD Simulation

Appendix B. Transfer Function Parameter Determination

| DMA combination | 1-2 | 1-3 | 2-1 | 2-3 | 3-1 | 3-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6778 | 1.0173 | 0.6964 | 1.0443 | 0.8622 | 0.8950 | |

| 1.0282 | 1.0568 | 1.0261 | 1.0504 | 0.9900 | 0.9891 |

| DMA | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| k | 0.5732 | 0.5988 | 0.7818 |

| 1.0154 | 1.0117 | 1.0080 |

Appendix C. Two-Dimensional Property Distribution for Agglomerated Silver Particles Treated at Different Sintering Temperatures

References

- Tavakoli, F.; Olfert, J.S. Determination of particle mass, effective density, mass–mobility exponent, and dynamic shape factor using an aerodynamic aerosol classifier and a differential mobility analyzer in tandem. Journal of Aerosol Science 2014, 75, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, E.O.; Whitby, K.T. Aerosol classification by electric mobility: apparatus, theory, and applications. Journal of Aerosol Science 1975, 6, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Dutcher, D.; Emery, M.; Pagels, J.; Sakurai, H.; Scheckman, J.; Qian, S.; Stolzenburg, M.R.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Tandem Measurements of Aerosol Properties—A Review of Mobility Techniques with Extensions. Aerosol Science and Technology 2008, 42, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slowik, J.G.; Stainken, K.; Davidovits, P.; Williams, L.R.; Jayne, J.T.; Kolb, C.E.; Worsnop, D.R.; Rudich, Y.; DeCarlo, P.F.; Jimenez, J.L. Particle Morphology and Density Characterization by Combined Mobility and Aerodynamic Diameter Measurements. Part 2: Application to Combustion-Generated Soot Aerosols as a Function of Fuel Equivalence Ratio. Aerosol Science and Technology 2004, 38, 1206–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, F.; Olfert, J.S. An Instrument for the Classification of Aerosols by Particle Relaxation Time: Theoretical Models of the Aerodynamic Aerosol Classifier. Aerosol Science and Technology 2013, 47, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolzenburg, M.R. An Ultrafine Aerosol Size Distribution System. Disseratation, University of Minnesota, Minnesota, 1988.

- Rüther, T.N.; Rasche, D.B.; Schmid, H.J. The Centrifugal Differential Mobility Analyser – A new device for determination of two-dimensional property distributions. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, L.; Chen, D.R. Technical Note: A New Deconvolution Scheme for the Retrieval of True DMA Transfer Function from Tandem DMA Data. Aerosol Science and Technology 2006, 40, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCarlo, P.F.; Slowik, J.G.; Worsnop, D.R.; Davidovits, P.; Jimenez, J.L. Particle Morphology and Density Characterization by Combined Mobility and Aerodynamic Diameter Measurements. Part 1: Theory. Aerosol Science and Technology 2004, 38, 1185–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).