1. Introduction

The concept of incremental dialysis was initially established in the context of peritoneal dialysis treatment [

1]. Subsequently, use of this therapeutic strategy was extended to extra-corporeal dialysis, becoming known as incremental hemodialysis (IHD). IHD was adopted across a wide population of patients with End Stage Chronic Kidney Disease (ESKD) who were mainly treated by means of twice-weekly hemodialysis sessions (2WHD) until the need arose to progress to a thrice-weekly frequency (3WHD) [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].One of the major benefits of IHD is represented by the possibility of starting patients on a once-weekly hemodialysis bridging schedule (1WHD) before patients transition to a higher frequency of treatments. Indeed, the first therapeutic approach for chronic uremic patients in 1WHD with no dietary restrictions was introduced in the 1960s by Scribner et al., although it was promptly abandoned within a few weeks due to the rapid onset of “underdialysis syndrome” [

8]. In the 1980s, the practical experiences first described by Mitch et al [9] and Morelli et al. [

10] were again reintroduced in the 1990s by Locatelli et al. with his Integrated Diet Dialysis Protocol (IDDP) [

11,

12]. The IDDP was progressively modified, integrated and optimized by Caria S. et al. and Bolasco et al., with the first reports published in 2014, renaming the protocol as the 'Combined Diet Dialysis Program' (CDDP) [

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, still today, the majority of Authors tend to prescribe a twice-weekly IHD schedule in which the regulation of uremia is not supported by an integrated low-protein nutritional program, but merely on the persistence of adequate residual kidney function (RKF) and optimal efficiency of extracorporeal clearance aimed at slowing down the inevitable loss of glomerular filtration (GFR) and diuresis [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Indeed, even following the advent of 1WHD, many Authors failed to integrate the schedule with a low-protein diet, or, even when doing so, tended to adopt a Very Low Protein Diet (VLPD) accounting for 0.3-0.4 g protein/kg/day with supplementation of amino acids and/or their keto-analogues, in the same way as for IDDH [

11,

12]. Integrated protocols based on use of a VLPD put patients at higher risk of malnutrition, poor control of uremia and scarce patient adherence due, in particular, to the large number of tablets or sachets to be taken daily. However, several Authors opted for diets based on a higher protein content of 0.6 g protein/Kg/day (Low Protein Diet, LPD) together with supplementation of amino acids and/or their keto-analogues [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Literature reports have indeed confirmed how the efficacy of a lower-frequency hemodialysis schedule associated with a prudent, but rigorously adhered to, low protein diet, is linked to a series of fundamental factors that affect mortality, morbidity and quality of life of patients, i.e.: a) the well-known slower rate of RKF decline elicited by a low-protein diet [

22,

23,

24]; b) a lower number of hemodialysis sessions with consequent decrease in a detrimental dialysis-induced hypercatabolic and inflammatory response resulting in clinical frailty of patients [

25] - this situation can be easily modified by using biocompatible membranes and materials, where possible, and use of ultrapure dialysis fluids and infusion solutions [

26,

27]; c) a higher-frequency hemodialysis schedule based on increased weekly treatment sessions typically reduces the rate of ultrafiltration during hemodialysis and lowers the frequency and severity of intradialytic hypotensive episodes resulting in a more rapid decline of RKF and progressive reduction of 24-hour urine volume [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The aim of this study therefore was to evaluate literature reports and identify protocols relating to trials conducted and completed exclusively using a 1WHD schedule for the purpose of evaluating safety, clinical benefits and drawbacks and impact on the quality of life of enrolled patients, all of whom agreed to adhere regularly to a low-protein diet for the purpose of initiating a once-weekly hemodialysis protocol.

2. Methods, Data Sources and Search Strategies

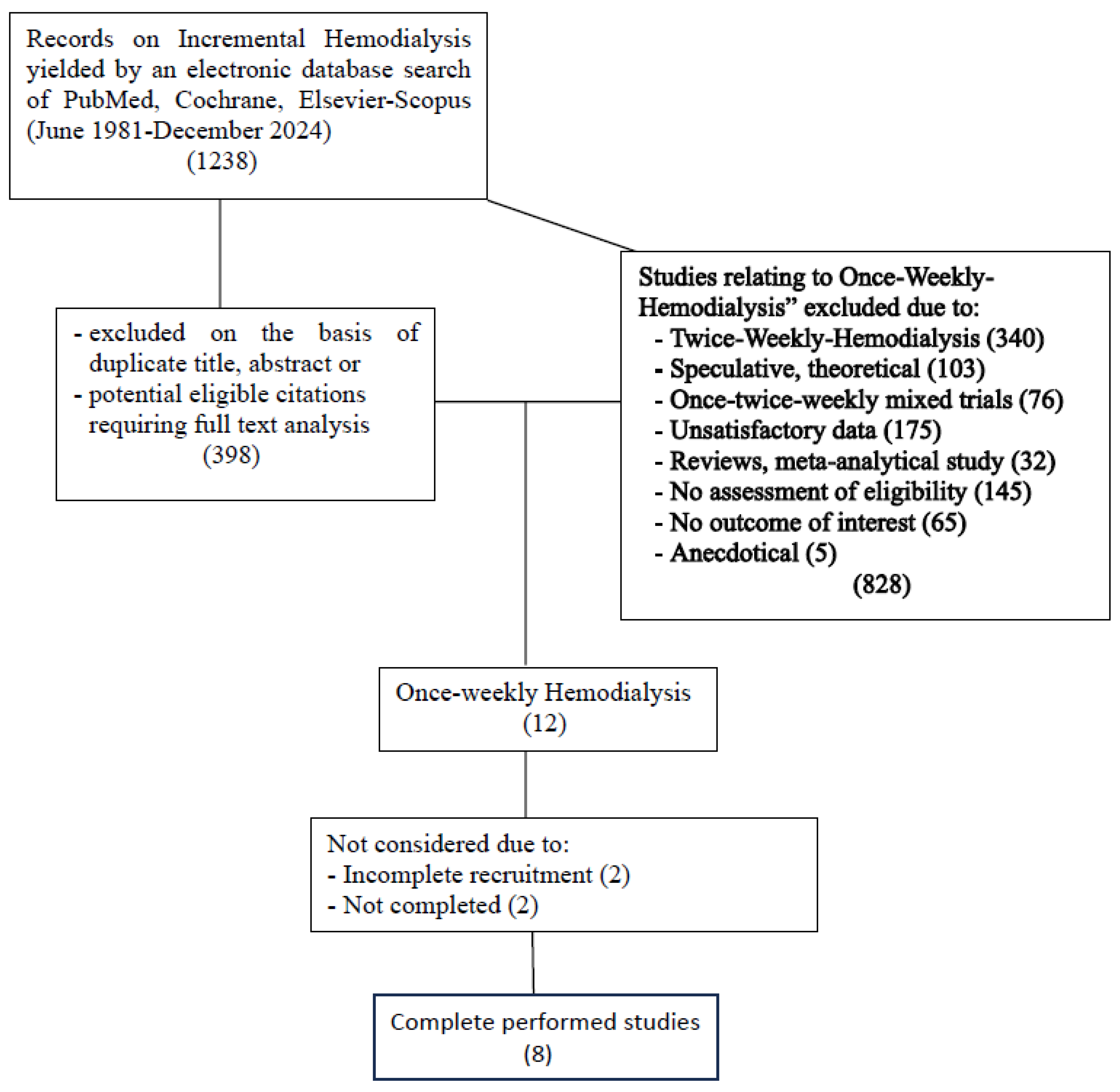

This systematic review was carried out based on presence of the term “Incremental Hemodialysis” (IHD). A systematic search of the online databases Medline through PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library was performed to include research studies dating back to the 1980s. The studies thus identified were based on the application of a series of methodologies for the purpose of initiating 1WHD in selected, motivated patients; studies relating to speculative and mathematical models, mixed patient populations undergoing 1WHD+2WHD, and patients on a 2WHD schedule were excluded. Only studies including the term “Incremental Hemodialysis” in which once-weekly hemodialysis trials had been followed to completion were selected. A thorough analysis of 1,238 publications including the term IHD yielded a total of 12 publications relating to patients on 1WHD, which on further analysis were reduced to 8; of these, only three studies had been set up with a control group. The flow-chart in

Figure 1 lists the reasons for exclusion from further analysis.

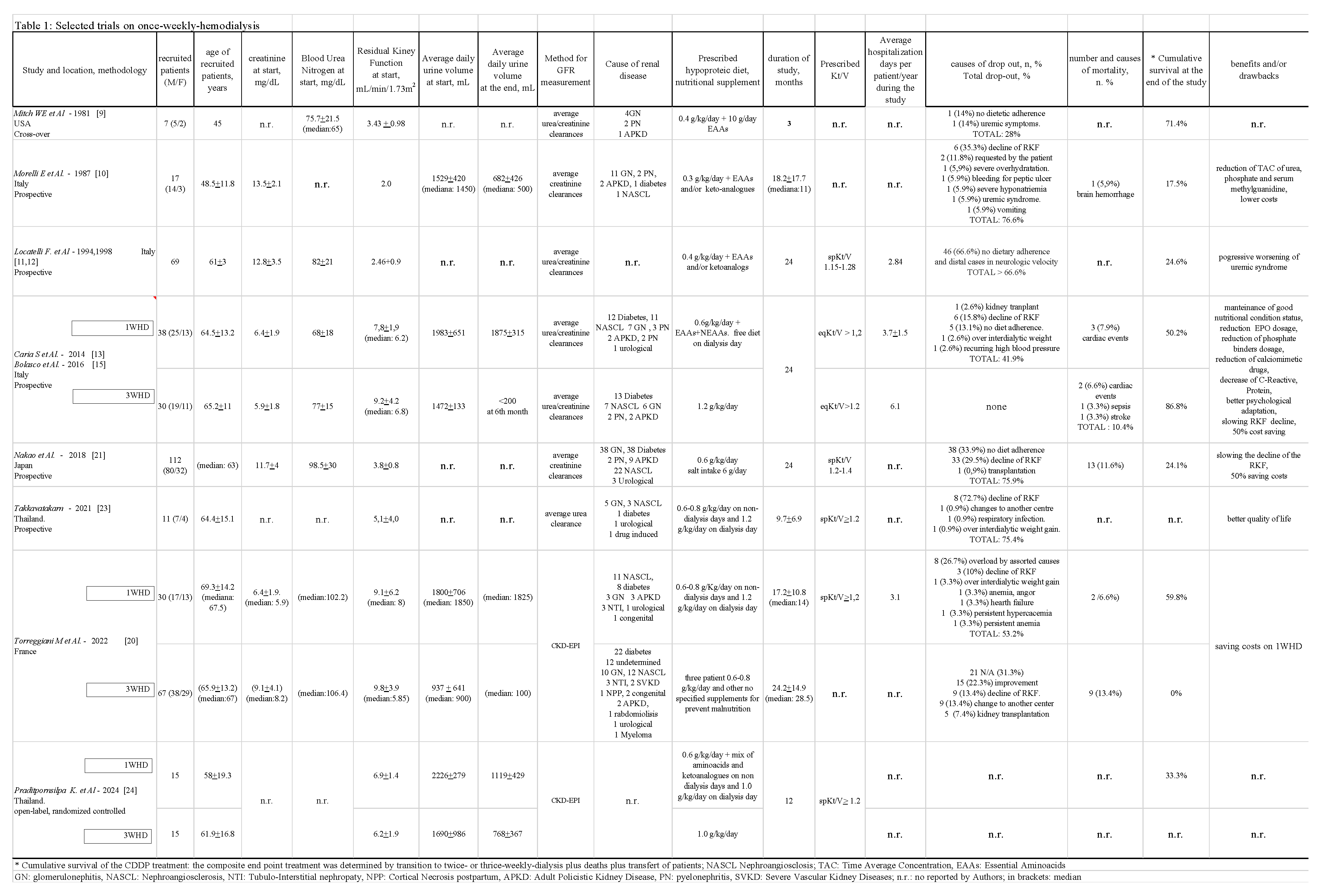

3. Baseline Details Reported in Studies

The main characteristics of the 8 resulting studies are summarized in Table 1, including name of the Author, location, and when provided, number of recruited patents (male/female), age (years), reference number, baseline creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, mean RKF trend and methods used to calculate the latter, 24H daily urine volume at baseline and end of the study, causes of renal diseases, nutritional combined diet with/without supplementation, average duration of 1WHD, hemodialytic adequacy, reasons for drop-out, mortality, cumulative survival, days of hospitalization, clinical benefits and/or drawbacks. Recruited patients all displayed a good nutritional status with a BMI 18.5-25 kg/m2 and metabolic steady state. The same criteria were used in three parallel comparison studies. Table 1 indicates, where detectable, the mean + SD, and/or the median.

4. Results

Studies included were all published between June 1981 and December 2024. They accounted for a total of 299 patients treated with 1WHD with a mean age ranging from 45 to 68 years, in addition to 112 patients included in three comparative studies in which 15 patients had received 2WHD and 87 3WHD. Three studies were performed in Italy, two in Thailand, one in North America, one in France and one in Japan. In five studies, average RKF was calculated based on urea + creatinine clearance/2, mL/min/1.73 m

2 yielding average values of 5.62.5, in one using urea clearance mL/min/1.73 m

2 equal to 5.1

+4.0, in two creatinine clearance mL/min/1.73 m

2 yielding average values 2.9

+1.3, in another CKD-EPI mL/min/1.73 m

2 yielding values of 6.9

+1.4 and in the last, creatinine clearance mL/min/1.73 m

2 with values of 2.0. Reported dialysis adequacy was measured using single pool Kt/V (spKt/V) or equilibrated Kt/V (eqKt/V), with levels invariably > 1.2. Patients' BMI ranged from 22.0 to 26.5 kg/m

2. The average duration of 1WHD protocol varied between 1.5-24 months (15.9

+7.6). The dropout rate from 1WHD defined as progressing to higher frequency weekly hemodialysis sessions across five studies was 66.9

+14.5% (41.9-76.6), reducing to 50.4% at 12 months; in six studies cumulative survival (1WHD drop-out + deaths) was 35.8

+22.3% (17.5-71.4), which had decreased to 28.6% at 12 months. In seven studies, the average diuresis volume at baseline was 1664

+426 and 802

+707 (p=0.018) at the end of the study. A low-protein diet of 0.3-0.6 g protein/kg/day was prescribed in seven studies, of which six prescribed nutritional supplementation with amino acids with or without keto-analogues [

9,

10,

11,

13,

21,

24]; no dietary measures were implemented in two studies [

20,

21], whilst in another two, patients were allowed to eat freely on the day of their hemodialysis session [

13,

23,

24]. As no statistically significant effects, either positive or negative, were observed across seven studies, the 'Combined Diet Dialysis Program' based on a once-weekly hemodialysis protocol, should be highlighted [

13,

15]; indeed, at variance with the findings obtained for a thrice-weekly protocol, the 1WHD schedule yielded the following findings: stable Hb despite a significant reduction in dose of erythropoietin (p < 0.001) and reduction of calcium phosphate binders (p < 0.002) and use of calcimimetics (p < 0.03). In a sample of 75 hemodialysis sessions performed in the context of a 1WHD schedule, inter-dialysis weight gain was 900

+923 ml (min. 0, max. 2500 ml), with patients displaying a negative inter-dialysis weight gain in 5 out of 17 hemodialysis sessions (-974

+ - 667; min. -200, max -1400), thus dictating a need to reintegrate ideal dry weight during sessions [

16]. Following 8-12 days of oligoanuria, urination was reinstated and, in several cases, exceeded 10 L over six extra-dialysis days.

The main characteristics of the 8 resulting studies are summarized in Table 1, including name of the Author, location, and when provided, number of recruited patents (male/female), age (years), reference number, baseline creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, mean RKF trend and methods used to calculate the latter, 24H daily urine volume at baseline and end of the study, causes of renal diseases, nutritional combined diet with/without supplementation, average duration of 1WHD, hemodialytic adequacy, reasons for drop-out, mortality, cumulative survival, days of hospitalization, clinical benefits and/or drawbacks. Recruited patients all displayed a good nutritional status with a BMI 18.5-25 kg/m2 and metabolic steady state. The same criteria were used in three parallel comparison studies. Table 1 indicates, where detectable, the mean + SD, and/or the median. Sporadically several patients experienced a recovery of RKF with exit from 1WHD and return to outpatient clinical conservative with unquantifiable time. Regrettably, due to a lack of clinical data, the inter-dialysis influence of arterial hypotension on the general outcome of 1WHD, including incidence of vascular access issues, episodes of hyperkaliemia, episodes of hypervolemia and/or acute pulmonary edema, on number of days of hospitalization and quality of life. The main characteristics of the 8 resulting studies are summarized in Table 1, including name of the Author, location, and when provided, number of recruited patents (male/female), age (years), reference number, baseline creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, mean RKF trend and methods used to calculate the latter, 24H daily urine volume at baseline and end of the study, causes of renal diseases, nutritional combined diet with/without supplementation, average duration of 1WHD, hemodialytic adequacy, reasons for drop-out, mortality, cumulative survival, days of hospitalization, clinical benefits and/or drawbacks. Recruited patients all displayed a good nutritional status with a BMI 18.5-25 kg/m2 and metabolic steady state. The same criteria were used in three parallel comparison studies. Table 1 indicates, where detectable, the mean + SD, and/or the median. Regrettably, due to a lack of clinical data, the inter-dialysis influence of arterial hypotension on the general outcome of 1WHD, including incidence of vascular access issues, episodes of hyperkaliemia, episodes of hypervolemia and/or acute pulmonary edema, on number of days of hospitalization and quality of life.

5. Discussion

The main goal of a once-weekly hemodialysis schedule is to preserve the safety of patients and quality of life (QoL) for as long as possible. The fundamental basis underlying the inclusion and maintenance of ESKD patients on a 1WHD schedule is the compliance of both new patients and those currently undergoing conservative outpatient treatment in adhering to a low-protein calorie-controlled diet.

5.1. Hemodialysis Strategies

The depurative efficacy of current extracorporeal dialysis strategies in maintaining an adequate control of the uremic metabolism is of secondary importance compared to the contribution provided by a low-protein diet and maintenance of good RKF in the context of IHD, and particularly 1WHD. Indeed, the adequacy of current diffusive and/or convective extracorporeal techniques no longer poses a challenge due to the recent advent of high-efficiency dialysis machines, devices and compatible membranes capable of achieving, even exceeding spKt/V and/or eqKt/V > 1.2-1.4, more than sufficient to support a 1WHD schedule with the aim of better regulating uremia, reinstating euvolemia and rectifying any electrolyte imbalances. Paradoxically however, as a downside, effects of the hemodialysis session on RKF are manifested following completion of the session due to the onset of dialysis-induced hypercatabolism resulting in the generation of toxic small, medium and large pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant molecules [

32] and the well-known loss of more than 5g of amino acids in the outflow of spent dialysis fluid [

33]. Fortunately, this phenomenon wanes over subsequent extra-dialysis days. A gradual introduction to a 1WHD schedule will help to avoid an initial and abruptly intense start to HD, particularly in the presence of significant ultrafiltration or intradialytic hypotension, which may lead to a rapid decrease in RKF [

34]. Compared to peritoneal dialysis, average daily urine volumes were higher in patients on incremental HD (1WHD-2WHD) than those on conventional HD [

23], thus confirming how the transition of ESKD patients from conservative treatment to a 1WHD schedule is better accepted and less traumatic.

5.2. Nutritional Considerations

Several authors [

13,

23,

24] allowed patients to eat freely on the day of their hemodialysis session to compensate for the Protein Catabolic Rate corresponding to, or at times exceeding 1.4 g/kg/day. The need for this nutritional freedom on dialysis day is dictated largely by the energy demand produced by the hemodialysis session itself and to the dialysis-induced loss of amino acids [

33,

35]; this extra nutritional “reward” provides patients with an additional reason for embarking on and sticking to the 1WHD schedule. A very low-protein diet (VLP) of 0.6g protein/kg may however be required on the six inter-dialysis days, together with amino acid supplementation of mainly essential amino acids (EAA) and a quota of at least 4g/day branched chain amino acids (BCAA). The decision to supplement amino acids across inter-dialysis days is a rational one, particularly in view of the fact that even with diets providing 0.6 g protein/kg/day, EAAs are decreased by 50%, with EAAs in low-protein diets of 0.4 g protein/kg/day and 0.3 g protein/kg/day being reduced by 33% and 25%, respectively [

36,

38]. A series of interesting clinical benefits have been obtained following amino acid supplementation, as demonstrated in a study by Caria S. et al [

13] aimed at preventing at all costs the risk of progressive onset of sarcopenia [

39], whilst ensuring a calorie intake of at least 25-30 Kcal/day [

40]. Although one of the aspects given due consideration in the studies selected was maintenance of adequate diuresis, the importance of preserving phosphaturia even in the presence of GFR < 5 ml/min was underestimated: indeed, considering together levels of phosphaturia + the gastro-intestinal chelating effect of phosphorous chelating agents + low-protein diet of 1.0-1.2 g/kg/day, on a 3WHD schedule, a positive phosphate balance of 4.73 g/week is obtained. Accordingly, when adopting a 1WHD schedule with a dietary intake of 0.6 g/kg/day, optimum control of phosphates and hyperphosphatemia characterized by a negative phosphate balance reaching even – 3 g/kg/day is undeniably beneficial in reducing the incidence of cardiovascular events associated with the harmful phosphorus metabolism [

41]. Lastly, in 155 patients, these showed studies allowed us to extrapolate a mean but not significantly survival rate per patient/month in patients prescribed amino acid supplementation of 0.04 versus a rate of 0.03 obtained for the 142 patients who received no form of nutritional supplementation.

5.3. Motivation, Competence and Strategies

To effectively maintain a 1WHD schedule, the motivation and awareness of medical and nursing staff is paramount in aiding the transition. Indeed, the dialysis team is responsible for effectively monitoring sessions [

42] to ensure they proceed as smoothly as possible and, particularly, to limit the onset and intensity of harmful hypotensive episodes which may negatively affect RKF [

43]. To date, the small number of studies conducted have reported no major episodes of hyperkaliemia and, as yet, no positive or negative correlations in patients receiving amino acid supplementation can be inferred.

An additional benefit may be afforded by a reduced use of the vascular port and consequent decrease in associated complications [

44]. The present review failed to provide irrefutable data relating to mortality rates and days of hospitalization. Only five studies were found to initiate a 1WHD schedule at an RKF 5.0 - 10 ml/min/1.73m

2 and it is likely unadvisable to consider initiating 1WHD in late-referral patients with an eGFR < 5 ml/min/1.73m

2. The best effects are likely obtained both during transition to 1WHD and in the months immediately thereafter in the presence of an RKF of between 5-10 ml/min/1.73 m

2 and a well-maintained nutritional and metabolic profile. Moreover, to obtain a reliable measurement, RKF should be calculated based on the mean of creatinine + urea clearance/2 [

45,

46,

47]. Promising findings have been reported in three 1WHD trials, showing a significant decrease in 2-microglobulin levels throughout treatment compared to patients on 3WHD [

13,

20,

21]. This might have been due to better RKF preservation in incremental HD, potentially resulting in fewer cardiovascular events and lower mortality rates in this group [

48].

5.4. Limitations

To conclude, patients were assessed with regard to quality of life, anxiety and depression based on a range of scores which were difficult to combine or compare across studies. No studies reported significant impacts of 1WHD, largely due to the limitations of this review: First, there is a significant paucity of completed studies; second, the timing involved in referring patients to a 1WHD schedule varied across studies included in the review, thus contributing to a significant heterogeneity of results; third, variations in data relating to the definition of outcome and duration of follow-up may confound analysis. Lastly, it should be highlighted how the majority of studies included in the review were of an observational or retrospective design, which may have introduced limitations in terms of bias and interpretation of causality.

6. Conclusion

A once-weekly-hemodialysis protocol should be viewed as a bridging strategy between conservative pre-dialysis treatment in patients with ESKD and the onset of a full hemodialysis program geared towards preserving RKF and delaying the need for more frequent hemodialysis sessions. Greater emphasis should be placed on the importance of prescribing a low-protein diet and replacing amino acids lost during hemodialysis, with the intent of prolonging RKF and its vastly underestimated ability of facilitating the continuous clearance of small and medium toxic molecules from the body. A clearance index of eq/spKt/V > 1.2-1.4 is safe and easily achievable, and should be implemented as soon as a decline in RKF is detected. In the review conducted, Authors who opted to implement a once-weekly hemodialysis protocol likely favored a prospective or retrospective over a randomized study design due to the ethical difficulty of denying to other patients who had been recruited based on their eligibility for a once-weekly hemodialysis schedule, access to this form of treatment, which was deemed far more acceptable and produced a far smaller social impact. Further confirmation of the considerations made here should be provided from a wider range of clinical trials investigating the effectiveness of a once-weekly hemodialysis schedule and conducted by specially trained and highly motivated nephrologists and nursing staff. In the meantime however, the term "incremental hemodialysis" should be expanded to include the once-weekly-hemodialysis protocol.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I am truly grateful to especially to Dr. Massimo Torregiani and Prof. Barbara Giorgina Piccoli and for their precious collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

the Author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mehrotra R, Nolph KD, Gotch F. Early initiation of chronic dialysis: role of incremental dialysis. Peritoneal dialysis international: journal of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. 4: Sep- Oct;1997 17(5), 1997.

- Vilar, E.; Wellsted, D.; Chandna, S.M.; Greenwood, R.N.; Farrington, K. Residual renal function improves outcome in incremental haemodialysis despite reduced dialysis dose. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 2502–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, Y.; Streja, E.; Rhee, C.M.; Ravel, V.; Amin, A.N.; Cupisti, A.; Chen, J.; Mathew, A.T.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Mehrotra, R.; et al. Incremental Hemodialysis, Residual Kidney Function, and Mortality Risk in Incident Dialysis Patients: A Cohort Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino JL, Domínguez P, Bueno B, Amézquita Y, Espejo B, Paraíso V Application of a pattern of incremental haemodialysis, based on residual renal function, when starting renal replacement therapy. Nefrologia. 2017 Jan-Feb;37(1):39-46.

- Liu, Y.; Zou, W.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; He, Q. Comparison between incremental and thrice-weekly haemodialysis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology 2019, 24, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghahremani-Ghajar M, Rojas-Bautista V, Lau WL, Pahl M, Hernandez M, Jin A, Reddy U, Chou J, Obi Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Rhee CM Incremental Hemodialysis: The University of California Irvine Experience.Semin Dial. 2017 May;30(3):262-269.

- Han M, Song SH, Kwon SH. A Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trial: twice-Weekly vs. Thrice-Weekly Incident Hemodialysis in Elderly Patients (PRIDE): study Protocol Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN, 2023, 34, 653–654.

- Scribner BN, Buri R, Caner JE, Hegstrom R, Burnell JM.The treatment of chronic uremia by means of intermittent hemodialysis: a preliminary report. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1960 Apr 10-11;6: 114-22.

- Mitch, W.E.; Sapir, D.G. Evaluation of reduced dialysis frequency using nutritional therapy. Kidney Int. 1981, 20, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, E.; Baldi, R.; Barsotti, G.; Ciardella, F.; Cupisti, A.; Dani, L.; Mantovanelli, A.; Giovannetti, S. Combined Therapy for Selected Chronic Uremic Patients: Infrequent Hemodialysis and Nutritional Management. Nephron 1987, 47, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, F.; Andrulli, S.; Pontoriero, G.; Di Filippo, S.; Bigi, M.C. Supplemented Low-Protein Diet and Once-Weekly Hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1994, 24, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli F, Andrulli S, Pontoriero G, Di Filippo S, Bigi MC Integrated diet and dialysis programme. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13 Suppl 6:132-8.

- Caria, S.; Cupisti, A.; Sau, G.; Bolasco, P. The incremental treatment of ESRD: a low-protein diet combined with weekly hemodialysis may be beneficial for selected patients. BMC Nephrol. 2014, 15, 172–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolasco P, Caria S, Egidi MF, Cupisti A. Incremental approach to hemodialysis: twice a week, or once weekly hemodialysis combined with low-protein low-phosphorus diet? G Ital Nefrol. 2015 Nov-Dec;32(6).

- Bolasco P, Cupisti A, Locatelli F, Caria S, Kalantar-Zadeh K Dietary Management of Incremental Transition to Dialysis Therapy: Once-Weekly Hemodialysis Combined with Low-Protein Diet.J Ren Nutr. 2016 Nov;26(6):352-359.

- Bolasco, P.; Casula, L.; Contu, R.; Cadeddu, M.; Murtas, S. Evaluation of Residual Kidney Function during Once-Weekly Incremental Hemodialysis. Blood Purif. 2020, 50, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong M, Wityk Martin TL, Zimmermann GL, Drall K, Pannu NI. Personalizing haemodialysis treatment with incremental dialysis for incident patients with end-stage kidney disease: an implementation study protocol. BMJ Open. 2024 Jan 29;14(1).

- Murea M, Raimann JG, Divers J, Maute H, Kovach C, Abdel-Rahman EM, Awad AS, Flythe JE, Gautam SC, Niyyar VD, Roberts GV, Jefferson NM, Shahidul I, Nwaozuru U, Foley KL, Trembath EJ, Rosales ML, Fletcher AJ, Hiba SI, Huml A, Knicely DH, Hasan I, Makadia B, Gaurav R, Lea J, Conway PT, Daugirdas JT, P Kotanko P. Comparative effectiveness of an individualized model of hemodialysis vs. conventional hemodialysis: a study protocol for a multicenter randomized controlled trial (the TwoPlus trial) Trials, 2024, 25(1), 424.

- Riehl-Tonn VJ, MacRae JM, Dumanski SM, Elliott MJ, Pannu N, Schick-Makaroff K, Drall K, Norris C, Nerenberg KA, Pilote L, Behlouli H, Gantar T, Ahmed SB Sex and gender differences in health-related quality of life in individuals treated with incremental and conventional hemodialysis. Clin Kidney J. 2024 Sep 3;17(10).

- Torreggiani M, Fois A, Chatrenet A, Nielsen L, Gendrot L, Longhitano E, Lecointre L, Garcia C, Breuer C, Mazé B, Hami A, Seret G, Saulniers P, Ronco P, Lavainne F, Piccoli GB Incremental and Personalized Hemodialysis Start: A New Standard of Care. Kidney Int Rep. 2022 Feb 19;7(5):1049-1061.

- Nakao T, Kanazawa Y Takahashi T. Once-weekly hemodialysis combined with low-protein and low-salt dietary treatment as a favorable therapeutic modality for selected patients with end-stage renal failure: a prospective observational study in Japanese patients. BMC Nephrol. 2018 Jun 28;19(1):151.

- Mathew AT, Fishbane S, Obi Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K Preservation of residual kidney function in hemodialysis patients: reviving an old concept. Kidney Int. 2016 Aug;90(2):262-271.

- Takkavatakarn, K.; Kittiskulnam, P.; Tiranathanagul, K.; Katavetin, P.; Wongyai, N.; Mahatanan, N.; Tungsanga, K.; Eiam-Ong, S.; Praditpornsilpa, K.; Susantitaphong, P. The role of once-weekly online hemodiafiltration with low protein diet for initiation of renal replacement therapy: A case series. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2021, 44, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praditpornsilpa, K.; Susantitaphong, P.; Phannajit, J. #1928 Stepwise incremental hemodialysis and low-protein diet supplemented with keto-analogues to preserve residual kidney function: a pilot study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.C.-K.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Ng, J.K.-C.; Tian, N.; Burns, A.; Chow, K.-M.; Szeto, C.-C.; Li, P.K.-T. Frailty in patients on dialysis. Kidney Int. 2024, 106, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wilcox, C.S.; Lipkowitz, M.S.; Gordon-Cappitelli, J.; Dragoi, S. Rationale and Strategies for Preserving Residual Kidney Function in Dialysis Patients. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 50, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, I.; Lee, Y.K.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Obi, Y. Individualized Hemodialysis Treatment: A Perspective on Residual Kidney Function and Precision Medicine in Nephrology. Cardiorenal Med. 2018, 9, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; He, X.; Yang, Y. An analysis of the relationship of blood pressure and its variability with residual kidney function loss in hemodialysis patients. Clin. Nephrol. 2023, 100, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, M.; Chu, T.; Lin, S.; Chen, Y.; Tsai, T.; Wu, K. Comparison of residual renal function in patients undergoing twice-weekly versus three-times-weekly haemodialysis. Nephrology 2009, 14, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugirdas, J.T.; Greene, T.; Rocco, M.V.; A Kaysen, G.; A Depner, T.; Levin, N.W.; Chertow, G.M.; Ornt, D.B.; Raimann, J.G.; Larive, B.; et al. Effect of frequent hemodialysis on residual kidney function. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wilcox, C.S.; Lipkowitz, M.S.; Gordon-Cappitelli, J.; Dragoi, S. Rationale and Strategies for Preserving Residual Kidney Function in Dialysis Patients. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 50, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolasco, P.; Spiga, P.; Arras, M.; Murtas, S.; La Nasa, G. Could there be Haemodynamic Stress Effects on Pro-Inflammatory CD14+CD16+ Monocytes during Convective-Diffusive Treatments? A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Blood Purif. 2019, 47, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtas, S.; Aquilani, R.; Deiana, M.L.; Iadarola, P.; Secci, R.; Cadeddu, M.; Salis, S.; Serpi, D.; Bolasco, P. Differences in Amino Acid Loss Between High-Efficiency Hemodialysis and Postdilution and Predilution Hemodiafiltration Using High Convection Volume Exchange—A New Metabolic Scenario? A Pilot Study. J. Ren. Nutr. 2019, 29, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn P, Narasaki Y, Rhee CM. Intradialytic hypotension: is timing everything? Kidney Int. 2021.

- Canaud, B.; Leblanc, M.; Garred, L.J.; Bosc, J.-Y.; Argilés, À.; Mion, C. Protein catabolic rate over lean body mass ratio: A more rational approach to normalize the protein catabolic rate in dialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1997, 30, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Biolo, G.; Cederholm, T.; Cesari, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Morley, J.E.; Phillips, S.; Sieber, C.; Stehle, P.; Teta, D.; et al. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Optimal Dietary Protein Intake in Older People: A Position Paper From the PROT-AGE Study Group. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney-Martin G, O Ball R, Pencharz PB, Elango R. Protein Requirements during Aging Nutrients. 2016 Aug 11;8(8):492.

- Volpi E, Campbell WW, Dwyer JT, Johnson MA, Jensen GL, Morley JE, Wolfe RR Is the optimal level of protein intake for older adults greater than the recommended dietary allowance? J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013 Jun;68(6):677-81.

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Landi, F.; Schneider, S.M.; Zúñiga, C.; Arai, H.; Boirie, Y.; Chen, L.-K.; Fielding, R.A.; Martin, F.C.; Michel, J.-P.; et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: A systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing 2014, 43, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, M.; Byham-Gray, L.; Beto, J. A Review of Dietary Intake Studies in Maintenance Dialysis Patients. J. Ren. Nutr. 2015, 25, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolasco, P.; Murtas, S. Clinical benefits of phosphate control in progression of end stage renal disease. Panminerva Medica 2017, 59, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panminerva Med. 2017 Jun;59(2):133-138.

- Roberts, G.V.; Jefferson, N.M.; Picillo, R.; Torreggiani, M.; Piccoli, G.B.; Jaques, D.A.; Niyyar, V.D.; Lea, J.; Hercé, M.; Heude, I.; et al. Patient, Nurse, and Physician Perspectives on Personalized, Incremental Hemodialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2024, 35, 1442–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How should we manage adverse intradialytic blood pressure changes? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012 May;19(3):158-65.

- Torreggiani, M.; Esposito, C. Vascular access in incremental hemodialysis: is less always more? J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 1727–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J Nephrol. 1: 2024 Sep;37(7), 2024.

- Santos SF, Peixoto AJ, Perazella MA. Ho Selistre L, de Souza V, Nicola C, Juillard L, Lemoine S, Derain-Dubourg L Average creatinine-urea clearance: revival of an old analytical technique? Clin Kidney J. 2023 ;16(8):1298-1306. 26 May.

- Selistre L, de Souza V, Nicola C, Juillard L, Lemoine S, Derain-Dubourg L Average creatinine-urea clearance: revival of an old analytical technique? Clin Kidney J. 2023 ;16(8):1298-1306. 26 May.

- Impact of the Preservation of Residual Kidney Function on Hemodialysis Survival: Results Belcher J, Coyle D, Lindley EJ, Keane D, Caskey FJ, Dasgupta I, Davenport A, Farrington K, Mitra S, Ormandy P, Wilkie M, Macdonald J, Solis-Trapala I, Sim J, Davies SJ from the BISTRO Trial. Kidney360. 2024 Oct 10.

- Shi F, Sun L, Kaptoge S. Association of β2-microglobulin and cardiovascular events and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2021 Mar; 320:70-78.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).