Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

3. Methods, Model and Materials

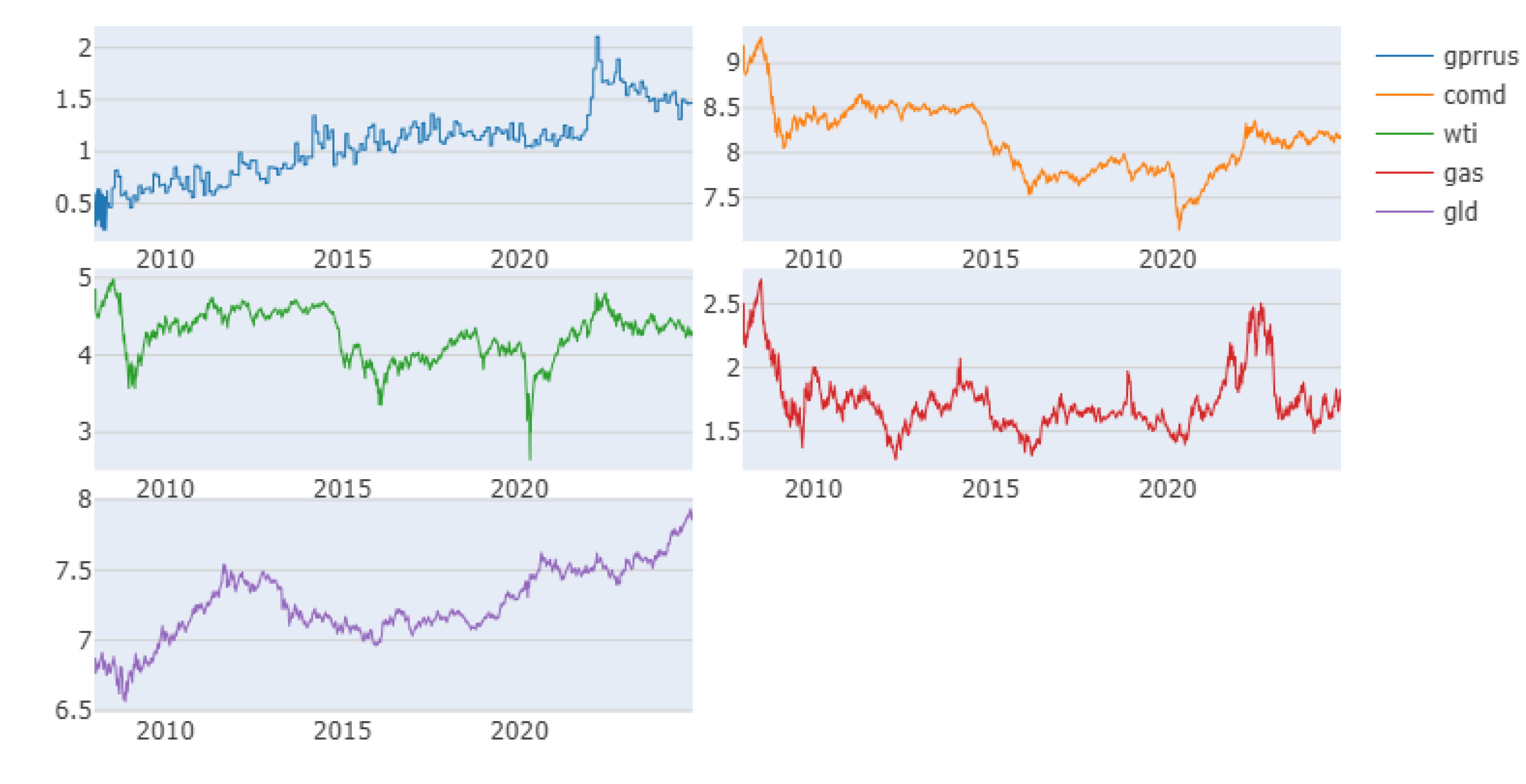

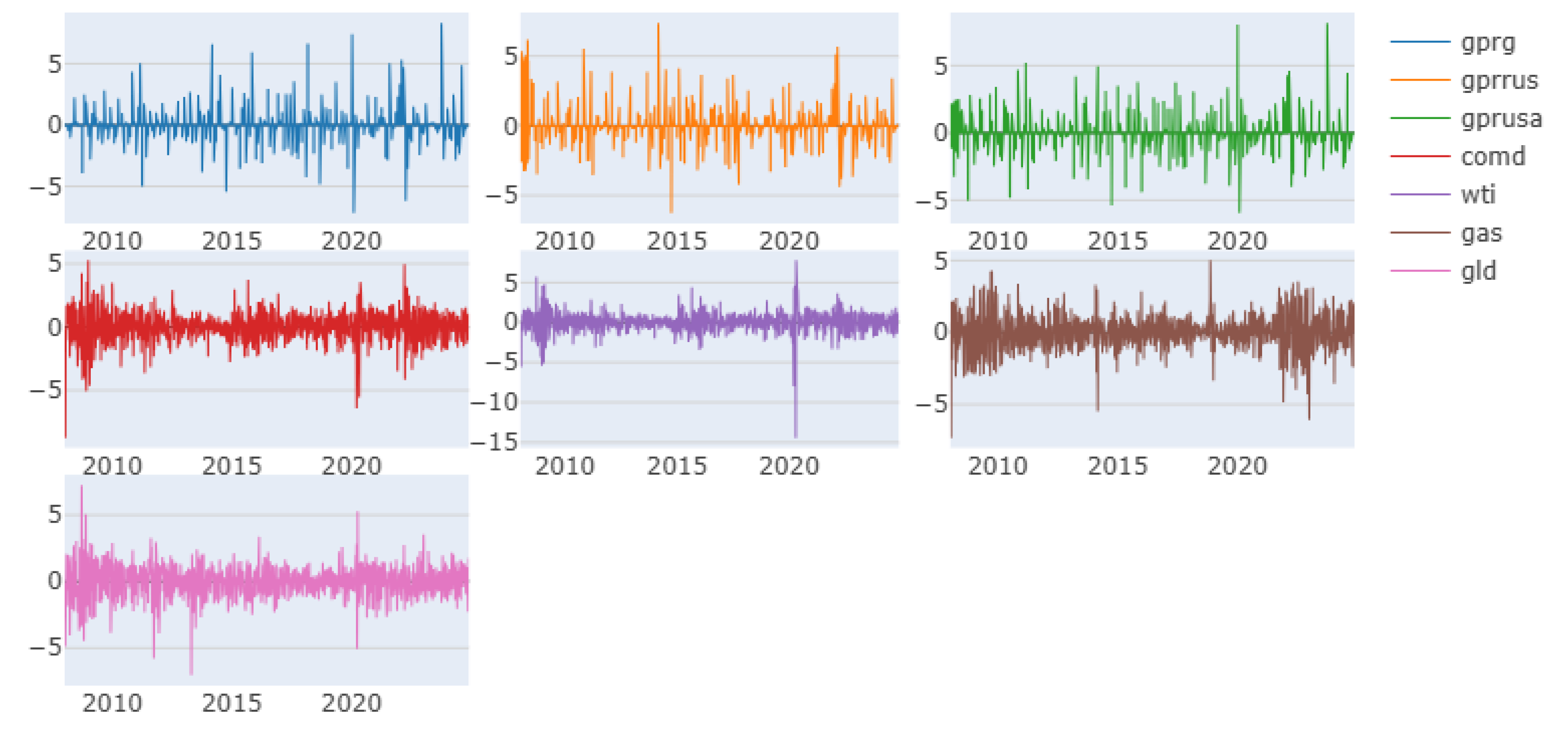

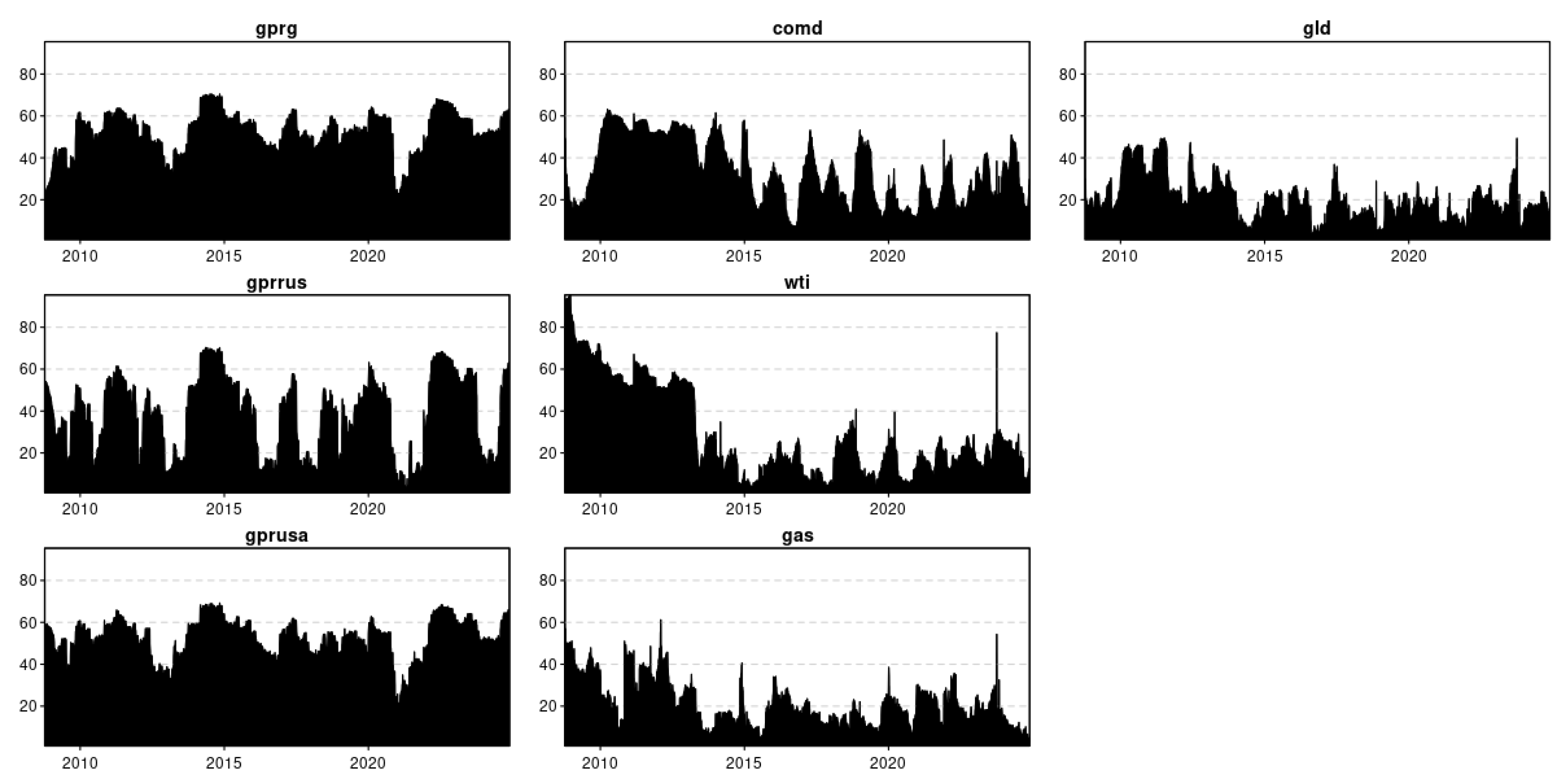

Data and Materials

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Preliminary Model Estimation

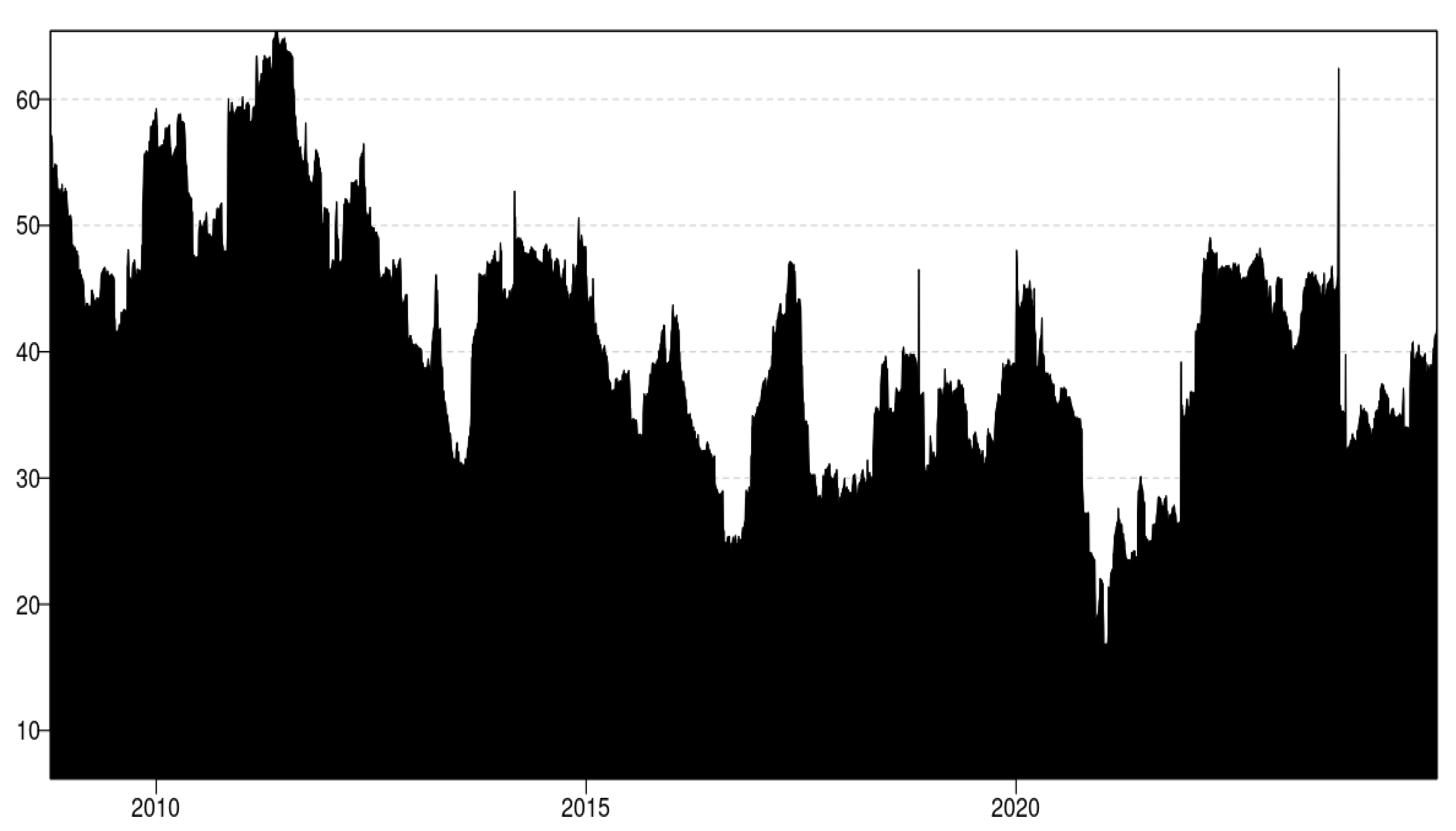

4.2. Commodity Market and Geopolitical Risk Assessment

4.3. TVP VAR Estimation Model

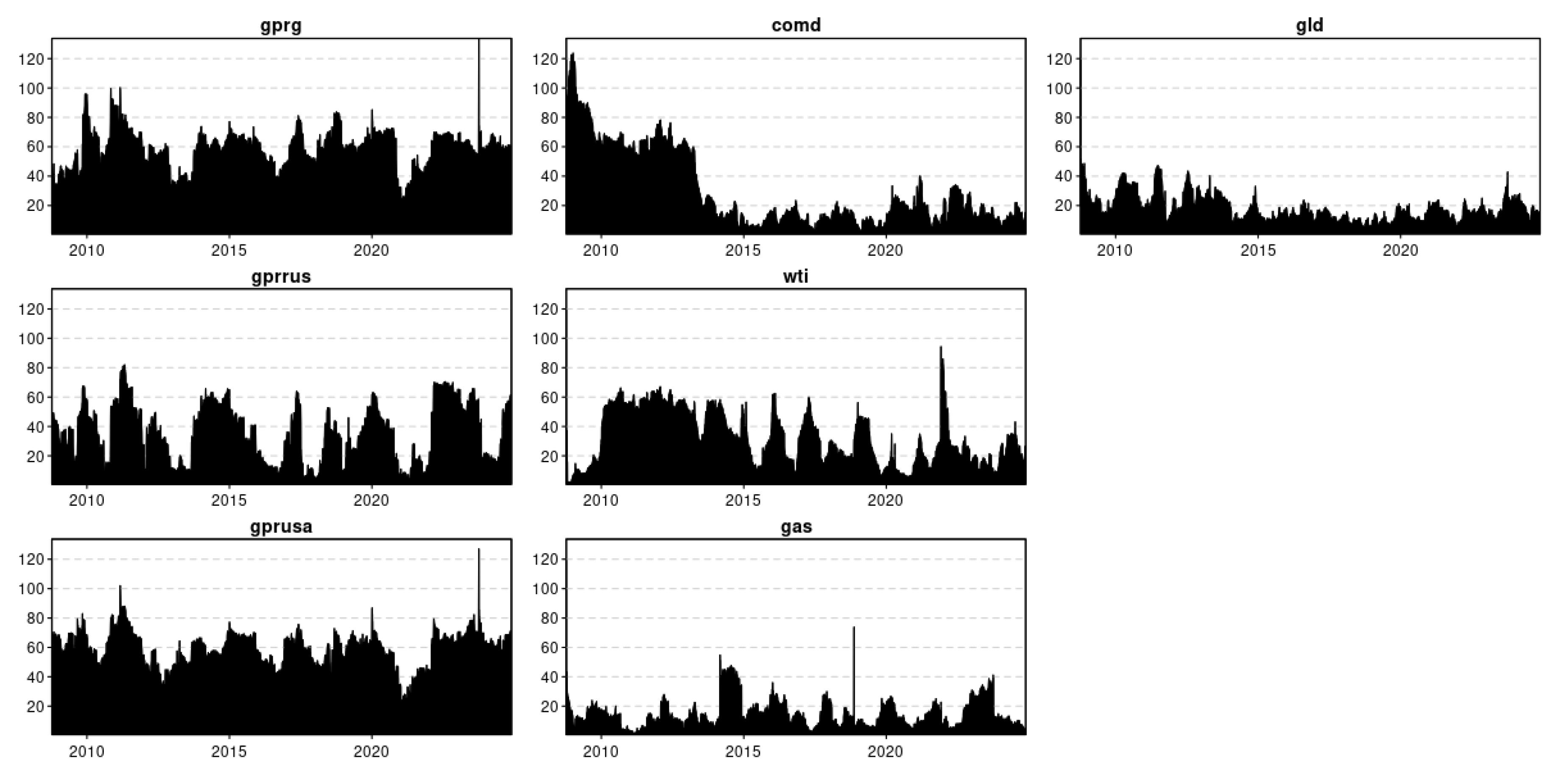

4.4. Commodity Markets Volatility Spillover

4.5. Dynamic Network Connectedness and Volatility Spillover Estimation

4.6. Global and Regional Geopolitical Risk and Commodity Markets

5. Conclusions

References

- Gong, X. , & Xu, J. Geopolitical risk and dynamic connectedness between commodity markets. Energy Economics 2022, 110, 106028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joets, M. , Mignon, V., Razafindrabe, T., Does the volatility of commodity prices reflect macroeconomic uncertainty? Energy Econ. 2017, 68, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngo¨r, A. , Tas¸ tan, H., On macroeconomic determinants of co-movements among international stock markets: evidence from DCC-MIDAS approach. Quant. Financ. Econ. 2021, 5, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. , Deng, Y., Yang, X., Cao, J., Yang, X., A network perspective of comovement and structural change: evidence from the Chinese stock market. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 76, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Xiao, X., Wahab, M.I.M., Ma, F., The role of oil futures intradayinformation on predicting US stock market volatility. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2021, 6, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S. H. , & Nam, S. Technical Innovation and Export Activities of Small and Medium-Sized Firms in Korea. Korean Social Science Journal 2021, 48, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Aruga, K. , & Wakamatsu, H. Investigating the Consumption Patterns of Japanese Seafood during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Commodities 2024, 3, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.W. , Khan, K., Tao, R., Nicoleta-Claudia, M., Does geopolitical risk strengthen or depress oil prices and financial liquidity? Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Energy 2019, 187, 116003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinbas, H. Volatility in the Turkish stock market: an analysis of influential events. Journal of Asset Management 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, M. Portfolio optimization in deformed time. Journal of Asset Management 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, M. , Gupta, R., McAleer, M., Forecasting volatility and co-volatility of crude oil and gold futures: effects of leverage, jumps, spillovers, and geopolitical risks. Int.J. Forecast. 2020, 36, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacelli, V. , Di Tommaso, C., Foglia, M., & Povia, M. M. Spillover effects between energy uncertainty and financial risk in the Eurozone banking sector. Energy Economics 2024, 108082. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A.K. , Boachie, M.K., Suleman, M.T., Gupta, R., Structure dependence between oil and agricultural commodities returns: the role of geopolitical risks. Energy 2021, 219, 119584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M. , Sohag, K., Khan, S., & Sohail, H. M. 2023. Impact of Russia–Ukraine conflict on Russian financial market: Evidence from TVP-VAR and quantile-VAR analysis. [CrossRef]

- Chenghao, Y. , Mayburov, I. A., & Ying, W. Fiscal Effects of Environmental Tax Reform: A Comparative Analysis of China, Germany and the United Kingdom. Journal of Tax Reform 2024, 10, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, H. , El-Gamal, M., Financial liquidity, geopolitics, and oil prices. Energy Econ. 2020, 87, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K. , Su, C.W., Tao, R., 2021. Does oil prices cause financial liquidity crunch?

- Perspective from geopolitical risk. Def. Peace Econ. 32.

- Lyu, Y. , Yi, H., Hu, Y., Yang, M., Economic uncertainty shocks and China’s commodity futures returns: a time-varying perspective. Res. Policy 2021, 70, 101979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X. , Yilmaz, K., Better to give than to receive: predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. Int. J. Forecast. 2012, 28, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X. , Yilmaz, K., On the network topology of variance decompositions: measuring the connectedness of financial firms. J. Econ. 2014, 182, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Diebold, F.X. , Liu, L., Yilmaz, K., 2017. Commodity Connectedness.

- Olshanska, O. , Bebko, S., & Budiakova, O. Solving the food crisis in the context of developing the bioeconomy of the agro-industrial complex of Ukraine. Economics, Finance and Management Review. [CrossRef]

- Tyczewska, A. , Twardowski, T., & Woźniak-Gientka, E. Agricultural biotechnology for sustainable food security. Trends in biotechnology 2023, 41, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidolin, M. , La Ferrara, E., The economic effects of violent conflict: evidence from asset market reactions. J. Peace Res. 2010, 47, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. , & Baek, J. 2024. A new look at exchange rate dynamics and the bilateral trade balance: The case of South Korea. The Singapore Economic Review.

- Yie, M. S. , & Nam, S. J. The impact of ICT sector on economic output and growth. Informatization Policy 2019, 26, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , Zhang, Z., Yan, L., Wen, F. Forecasting the volatility of EUA futures with economic policy uncertainty using the GARCH-MIDAS model. Fin. Innov. 2021, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, D.D. , Londono, J.M., Ross, L.J., Generating options-implied probability densities to understand oil market events. Energy Econ. 2017, 64, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysan, AF, Canga, M. , & Kayani, UN A Comparative Analysis between Islamic Economics and Environmental Economics: Historical Development and its Significance for Contemporary Challenges. Journal of Balkan Economies and Management 2024, 1, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. , Ji, Q., Du, Y.-J., Geng, J.-B., The dynamic dependence of fossil energy, investor sentiment and renewable energy stock markets. Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M. , Sohag, K., Doroshenko, S. et al. Examination of Bitcoin Hedging, Diversification and Safe-Haven Ability During Financial Crisis: Evidence from Equity, Bonds, Precious Metals and Exchange Rate Markets. Comput Econ. [CrossRef]

- Caldara, D. , Iacoviello, M.F.R.B., 2018. Measuring Geopolitical Risk. Working Papers – U. S, pp. 1–47.

- Sharif, A. , Aloui, C., Yarovaya, L., 2020. COVID-19 Pandemic, Oil Prices, Stock Market, Geopolitical Risk and Policy Uncertainty nexus in the US. Fresh, economy.

- Wen, F. , Cao, J., Liu, Z., Wang, X., Dynamic volatility spillovers and investment strategies between the Chinese stock market and commodity markets. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 76, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindyck, R.S. , Rotemberg, J.J., The excess co-movement of commodity prices. Econ. J. 1990, 100, 1173–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Aysan, A. F. , Batten, J., Gozgor, G., Khalfaoui, R., & Nanaeva, Z. Metaverse and financial markets: A quantile-time-frequency connectedness analysis. Research in International Business and Finance 2024, 72, 102527. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M. , Sohag, K., & Haddad, H. Comparative investment analysis between crypto and conventional financial assets amid heightened geopolitical risk. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R. , & Putnam, K. J. Financial Market Stress and Commodity Returns: A Dynamic Approach. Commodities 2024, 3, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, U. , Ullah, M., Aysan, A. F., Nazir, S., & Frempong, J. Quantile connectivity among digital assets, traditional assets, and renewable energy prices during extreme economic crisis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 208, 123635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H. , McIver, R., Yoon, S.-M., Dynamic spillover effects among crude oil, precious metal, and agricultural commodity futures markets. Energy Econ. 2017, 62, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopczuk, M. , Wese Simen, C., Wichmann, R., The dynamics of commodity return comovements. J. Futur. Mark. 2021, 41, 1597–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M. , & Baek, J. 2021. Exchange rate volatility and domestic investment in G7: Are the effects asymmetry? Empirica.

- Syarif, M. F. , & Aysan, A. F. 2024. Sharia crowdfunding in Indonesia: a regulatory environment perspective. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management.

- Yang, J. , Li, Z., Miao, H.,. Volatility spillovers in commodity futures markets: a network approach. J. Futur. Mark. 2021, 41, 1959–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupabado, M.M. , Kaehler, J., Financialization, common stochastic trends, and commodity prices. J. Futur. Mark. 2021, 41, 1988–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F. , Gurdgiev, C., Sohag, K., Islam, M. M., & Zeqiraj, V. Global, local, or glocal? Unravelling the interplay of geopolitical risks and financial stress. Journal of Multinational Financial Management 2024, 75, 75–100871. [Google Scholar]

- Aristovnik, A. , Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, F. , Pesenti, M., Araniti, F., Pilu, S. R., & Nocito, F. F. An Integrated and Multi-Stakeholder Approach for Sustainable Phosphorus Management in Agriculture. Agronomy. [CrossRef]

- Haase, M. , & Henn, J. Time-Varying Deterministic Volatility Model for Options on Wheat Futures. Commodities 2024, 3, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshisashi, K. , & Yamada, Y. Pricing Multi-Asset Bermudan Commodity Options with Stochastic Volatility Using Neural Networks. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. , Lang, C., Corbet, S., Hou, Y. (Greg), & Oxley, L. Exploring the dynamic behaviour of commodity market tail risk connectedness during the negative WTI pricing event. Energy Economics 2023, 125, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmel, B. , Fischer, L., Juraschek, E., Peuker, L., Stemmler, N., Vielsack, A., Bulander, R., Hinderer, H., Kilian-Yasin, K., Brugger, T., Kühn, A., & Brysch, T. Navigating the Challenges of Commodity Traps and Platform Economies: An Assessment in the Context of the Northern Black Forest Region and Future Directions. Commodities 2024, 3, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelmel, B. , Haug, T., Klein, L., Schwab, L., Bulander, R., Hinderer, H., Weyer, M., Brugger, T., Kuehn, A., & Brysch, T. Are German Automotive Suppliers in the Commodity Trap? Risks and Potentials of the Taiwanese Platform MIH EV Open. Commodities 2024, 3, 389–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostaridou, E. , Siatis, N., & Zafeiriou, E. Resource Price Interconnections and the Impact of Geopolitical Shocks Using Granger Causality: A Case Study of Ukraine–Russia Unrest. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. [CrossRef]

- Kyriazis, N. A. Optimal Portfolios of National Currencies, Commodities and Fuel, Agricultural Commodities and Cryptocurrencies during the Russian-Ukrainian Conflict. International Journal of Financial Studies 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, K. T. Benefits of Property Assessed Clean Energy Programs and Securitization of Property Assessed Clean Energy Loans. Commodities 2024, 3, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, K. , Vasilyeva, R., Urazbaeva, A., & Voytenkov, V. Stock market synchronization: The role of geopolitical risk. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2022, 15, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Tissaoui, K. , Abidi, I., Azibi, N., & Nsaibi, M. Spillover Effects between Crude Oil Returns and Uncertainty: New Evidence from Time-Frequency Domain Approaches. Energies. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S. , Xia, Y., Li, Q., & Chen, Y. Global geopolitical risk and financial stability: Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters.

- Yilmazkuday, H. Geopolitical risk and stock prices. European Journal of Political Economy 2024, 83, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , & Lin, T. A Novel Deterministic Probabilistic Forecasting Framework for Gold Price with a New Pandemic Index Based on Quantile Regression Deep Learning and Multi-Objective Optimization. Mathematics. [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, U. , Mohammed, K. S., Tiwari, S., Nakonieczny, J., & Nesterowicz, R. Connectedness between geopolitical risk, financial instability indices and precious metals markets: Novel findings from Russia Ukraine conflict perspective. Resources Policy 2023, 80, 103190. [Google Scholar]

- Micallef, J. , Grima, S., Spiteri, J., & Rupeika-Apoga, R. Assessing the Causality Relationship between the Geopolitical Risk Index and the Agricultural Commodity Markets. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. , Bakhshi, P., & Gupta, H. Volatility in International Stock Markets: An Empirical Study during COVID-19. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. [CrossRef]

- Conlon, T. , & McGee, R. Safe haven or risky hazard? Bitcoin during the Covid-19 bear market. Finance Research Letters 2020, 35, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A. , Lins, K. V., Roth, L., & Wagner, H. F. Do institutional investors drive corporate social responsibility? International evidence. Journal of Financial Economics 2019, 131, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N. , Liu, C., Da, B., Zhang, T., & Guan, F. Dependence and risk spillovers between green bonds and clean energy markets. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 279, 123595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loxton, M. , Truskett, R., Scarf, B., Sindone, L., Baldry, G., & Zhao, Y. Consumer Behaviour during Crises: Preliminary Research on How Coronavirus Has Manifested Consumer Panic Buying, Herd Mentality, Changing Discretionary Spending and the Role of the Media in Influencing Behaviour. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G. S. , Kaur, M., & Kaushik, P. Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Its Mitigation Strategies: A Review. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Mazur, M. , Dang, M., & Vega, M. COVID-19 and the march 2020 stock market crash. Evidence from S&P1500. Finance Research Letters 2021, 38, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivinay, Manujakshi, B. C., Kabadi, M. G., & Naik, N. A Hybrid Stock Price Prediction Model Based on PRE and Deep Neural Network. Data. [CrossRef]

- Staugaitis, A. J. , & Vaznonis, B. Financial Speculation Impact on Agricultural and Other Commodity Return Volatility: Implications for Sustainable Development and Food Security. Agriculture 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. , Hu, M., & Ji, Q. Financial markets under the global pandemic of COVID-19. Finance Research Letters 2020, 36, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruga, K. , & Wakamatsu, H. Investigating the Consumption Patterns of Japanese Seafood during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Commodities 2024, 3, 182–196. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, R. , & Putnam, K. J. Financial Market Stress and Commodity Returns: A Dynamic Approach. Commodities 2024, 3, 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q., Ullah, F., Amin, F., Ullah, M., (2024) Dynamic Connectedness between Geopolitical Risk and Flow of Foreign Remittances with application of NARDL estimation approach. Transnational Corporation Review 200106 . [CrossRef]

- Cogley, T. , Sargent, T.J., 2001. Evolving post–World War II U.S. inflation dynamics.

- NBER/Macroeconomics Annual (MIT Press) 16, 331–373.

- Cogley, T. , Sargent, T.J., Drifts and volatilities: monetary policies and outcomes in the post WWIIUS. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2005, 8, 262–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primiceri, G. , Time varying structural vector autoregressions and monetary policy. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 821–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakakis, N. , Gupta, R., Kollias, C., Papadamou, S. Geopolitical risks and the oil-stock nexus over 1899–2016. Financ. Res. Lett. 2017, 23, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Representation | Unit Of Measurement | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commodity Index | Comd. | Current spot price in US Dollar | S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (S&P GSCI), Garman and Klass (1980) |

| Crude Oil Futures | WTI | US Dollar Per Barrel | Energy Information Administration https://www.eia.gov |

| Natural Gas Futures | GAS | Dollars Per Million Btu | Energy Information Administration https://www.eia.gov |

| Gold | GLD | Current Price of Gold Per Ounce in US Dollar | https://goldprice.org/spot-gold.html |

| Geopolitical Risk Global | GPR | Frequency of Newspaper Stories and Features Worldwide | https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/gpr.htm Caldara and Iacoviello (2018) |

| Geopolitical Risk Russia | GPR-RUS | Frequency of Newspaper Stories and Features related to Russia | https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/gpr.htm Caldara and Iacoviello (2018) |

| Geopolitical Risk USA | GPR-USA | Frequency of Newspaper Stories and Features related to USA | https://www.matteoiacoviello.com/gpr.htm Caldara and Iacoviello (2018) |

| Date January 01, 2008, to November 25, 2024 | Data time Span | Crises Measurement | Volatility and Spillover |

| COVID-19 | Event-1 | Crises Measurement | WHO announced COVID-19 (March 11, 2020) |

| Russia Ukraine Conflict | Event-2 | Crises Measurement | Russia Ukraine Conflict (Feb 24, 2022) |

| GPR-RUS | COMD | WTI | GAS | GLD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1.068 | 8.146 | 4.272 | 1.734 | 7.258 |

| Variance | 0.111 | 0.147 | 0.102 | 0.059 | 0.065 |

| Skewness | 0.289*** | 0.273*** | -0.533*** | 1.478*** | 0.001 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -0.975 | |

| Ex.Kurtosis | -0.163** | -0.052 | -0.058 | 2.375*** | -0.323*** |

| -0.019 | -0.504 | -0.451 | 0 | 0 | |

| JB | 66.169*** | 55.091*** | 209.333*** | 2636.992*** | 19.148*** |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ERS | -0.246 | -0.062 | -1.074 | -0.658 | 0.83 |

| -0.805 | -0.951 | -0.283 | -0.511 | -0.407 | |

| Q(10) | 23508.930*** | 23909.399*** | 23587.762*** | 23339.532*** | 23874.570*** |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Q2(10) | 23598.807*** | 23892.272*** | 23622.239*** | 23325.317*** | 23870.574*** |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| ADF | 16.833*** | 14.132*** | 15.309*** | 14.004*** | 7.910*** |

| GPRRUS | COMD | WTI | GAS | GLD | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPRRUS | 87.34 | 2.44 | 2.62 | 4.14 | 3.46 | 51.66 |

| COMD | 1.66 | 53.4 | 36.82 | 3.53 | 4.59 | 46.6 |

| WTI | 1.84 | 16.05 | 73.51 | 4.48 | 4.12 | 26.49 |

| GAS | 2.08 | 2.33 | 2.83 | 89.24 | 3.52 | 10.76 |

| GLD | 2.37 | 5.24 | 4.69 | 2.32 | 85.37 | 14.63 |

| TO | 70.95 | 26.06 | 46.97 | 14.46 | 15.7 | 111.14 |

| INC.OWN | 95.29 | 79.46 | 120.47 | 103.71 | 101.07 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET | -4.71 | -20.54 | 20.47 | 3.71 | 1.07 | 27.78/22.23 |

| NPT | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | --- |

| GPRRUS | COMD | WTI | GAS | GLD | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPRRUS | 67.34 | 2.79 | 12.62 | 14.14 | 13.46 | 31.66 |

| COMD | 11.66 | 43.4 | 16.82 | 13.53 | 14.59 | 26.6 |

| WTI | 10.84 | 12.05 | 23.51 | 24.48 | 14.12 | 16.49 |

| GAS | 21.08 | 12.33 | 12.83 | 49.24 | 13.52 | 30.76 |

| GLD | 12.37 | 15.24 | 14.69 | 12.32 | 75.37 | 24.63 |

| TO | 51.95 | 16.06 | 26.91 | 11.46 | 15.7 | 91.14 |

| INC.OWN | 91.29 | 39.46 | 10.47 | 10.71 | 10.07 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET | -3.71 | -10.54 | 10.47 | 3.71 | 1.07 | 21.78/22.23 |

| NPT | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | --- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).