Submitted:

19 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Zone 7, located in the south of Ecuador, stands out as a megadiverse region due to the combined influence of the distinctive characteristics of the climate, soil, and topography of the Coastal Marine, Andean Sierra, and Eastern Jungle. The research focused on analyzing the impact of climate, soil, and slope on the phenotypic characteristics of the parent trees of J. neotropica populations, both natural and artificial. Six provenances were selected: The Tundo, The Victoria, The Tibio, The Zañe, and The Argelia. It is noteworthy that the latter is a planted forest that has naturalized over time. In the last two decades, a decrease in precipitation, an increase in temperature, relative humidity below 70%, and soil moisture below 60% were observed. Regarding the soil, the physical properties were similar, with mountainous relief and a texture ranging from loam to clay loam to sandy loam, and chemically neutral to slightly acidic. All provenances were found on slopes greater than 45%. Phenology varied by a maximum of one month between provenances in terms of presence, leaf fall, and fruit maturation. The age of the trees varied between provenances, with The Tundo being the oldest at 355 years and The Argelia the youngest at approximately 76 years. The results showed a wide diversity in phenotypic characteristics, ensuring a high adaptability of J. neotropica populations, a key species for the health of mountainous ecosystems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Climate

2.3. Soil

2.3.1. Identification of Representative Areas

2.3.2. Sample Extraction

2.3.3. Multiple Samples per Zone

2.3.4. Detailed Record

2.3.5. Storage and Biosafety

2.3.6. Recording of Weather Conditions

2.3.7. Sample Conservation and Laboratory Shipment

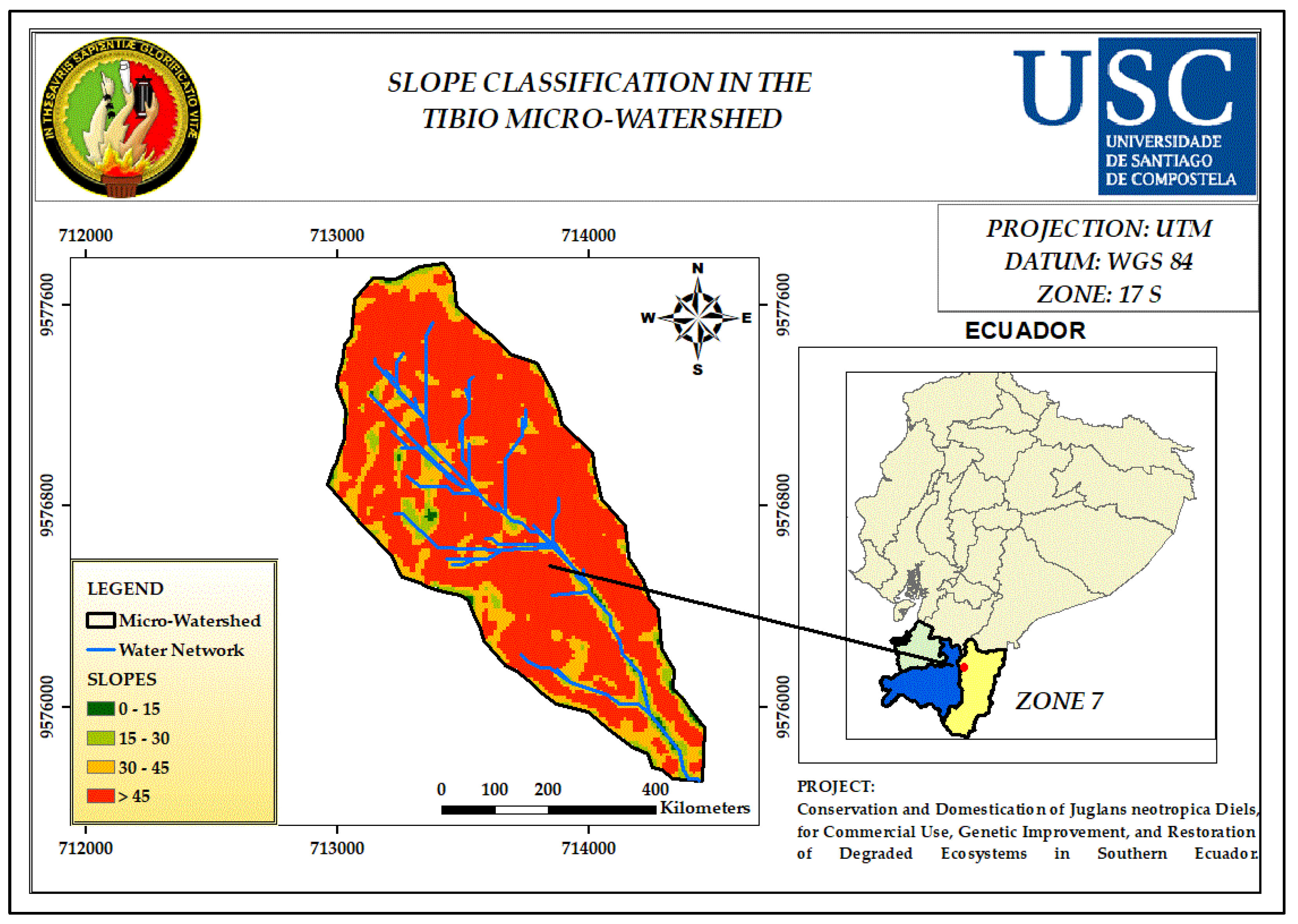

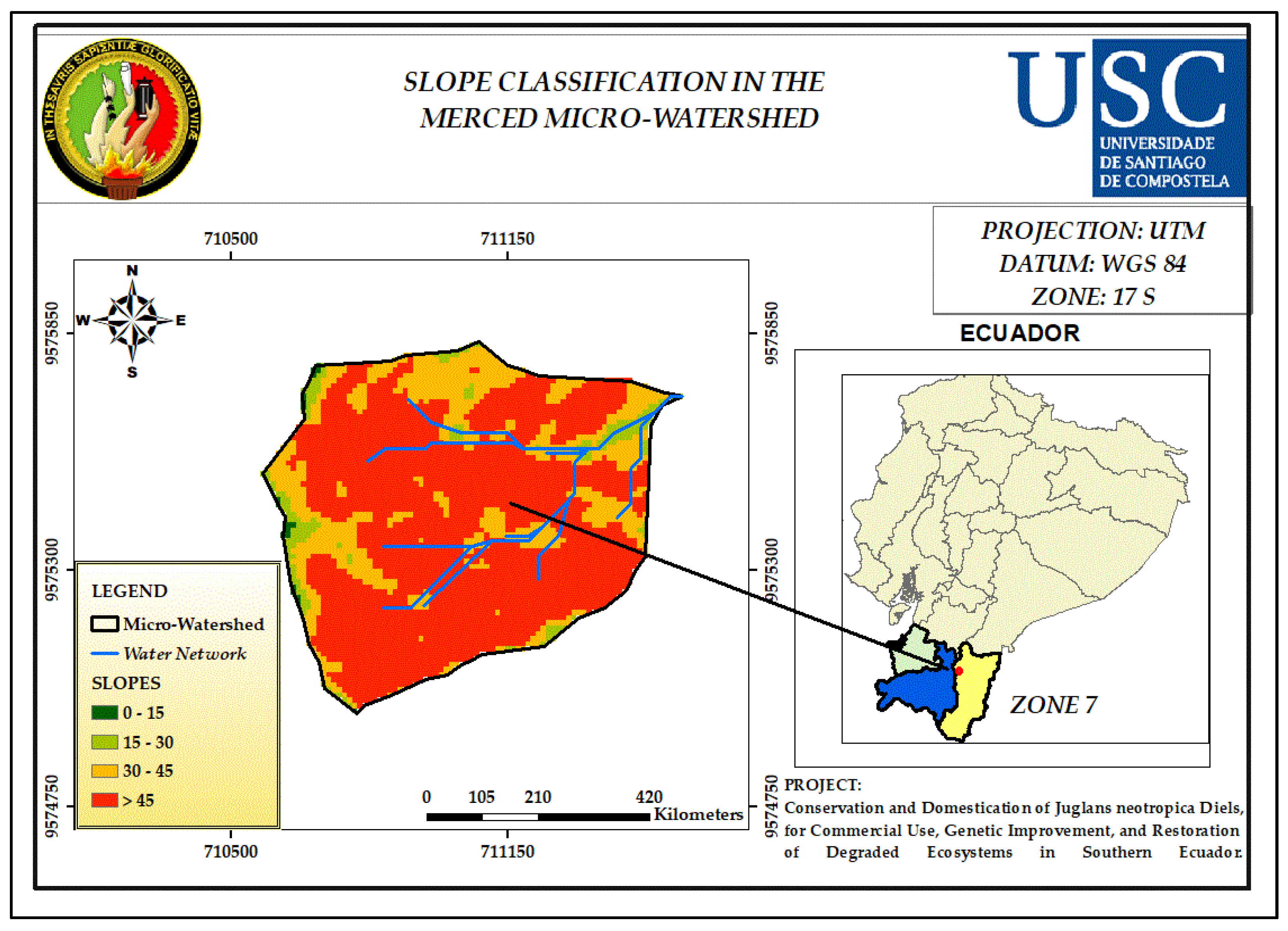

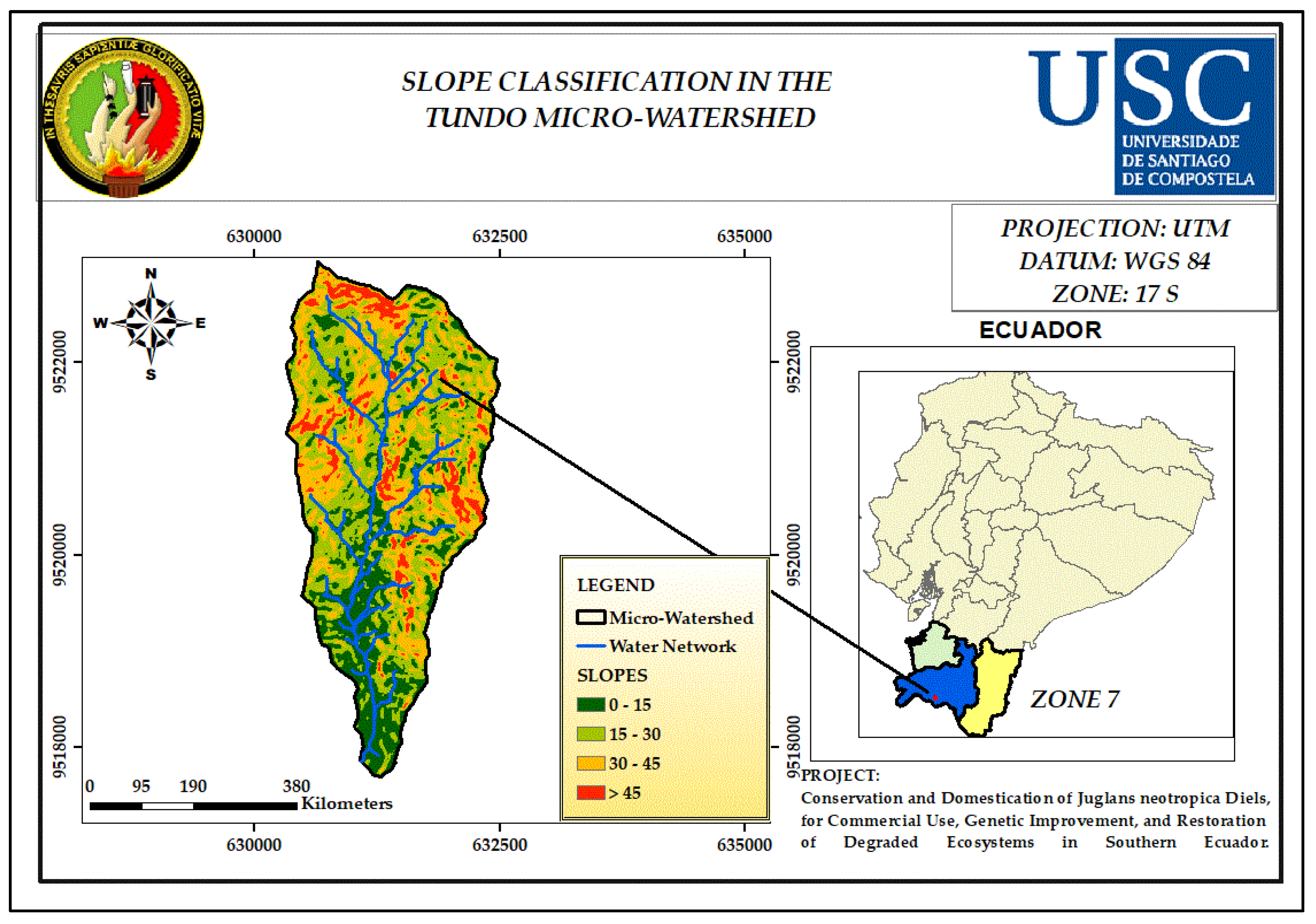

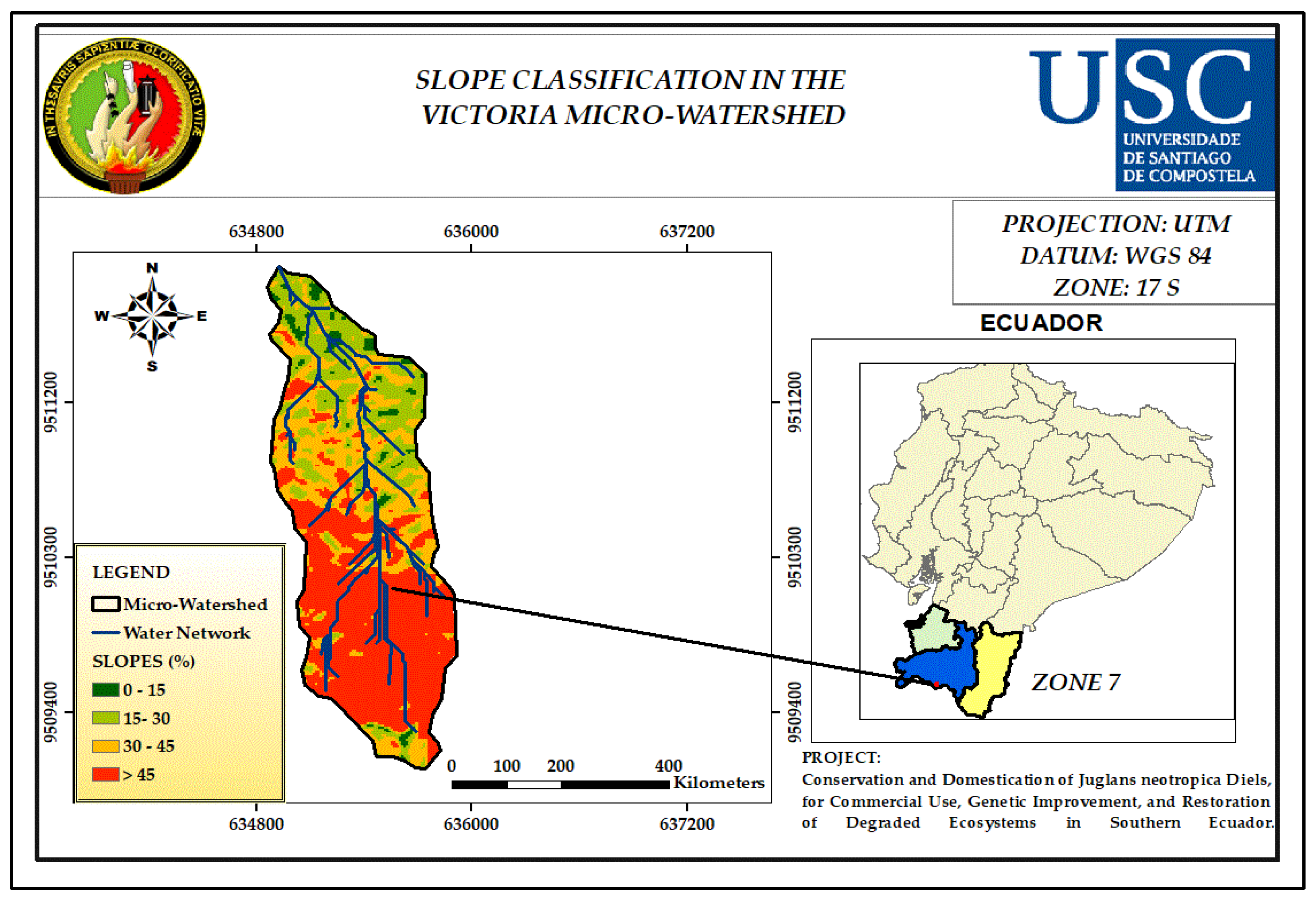

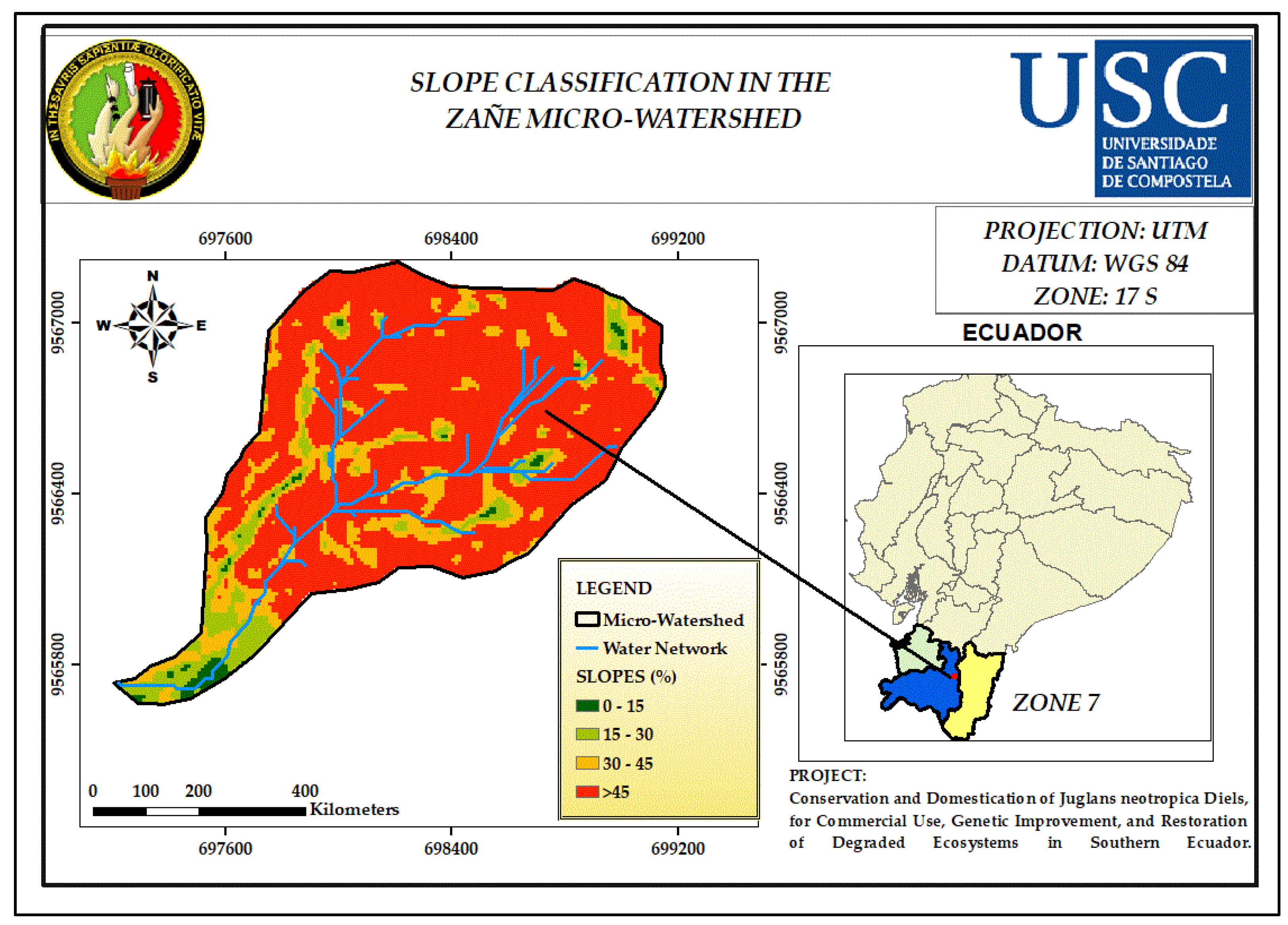

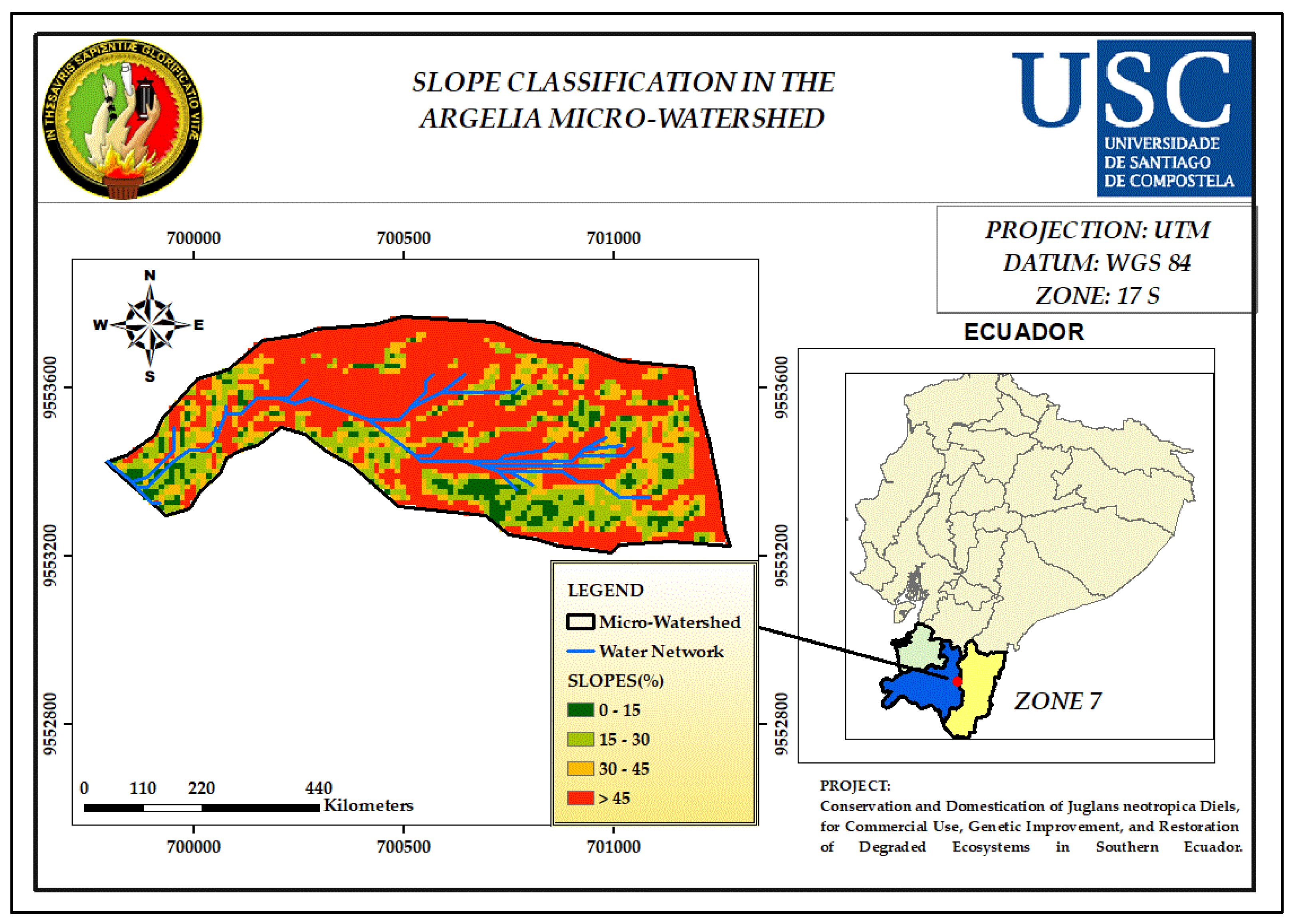

2.4. Slope

2.4.1. Topographic Digitization of Localities

2.5. Phenology

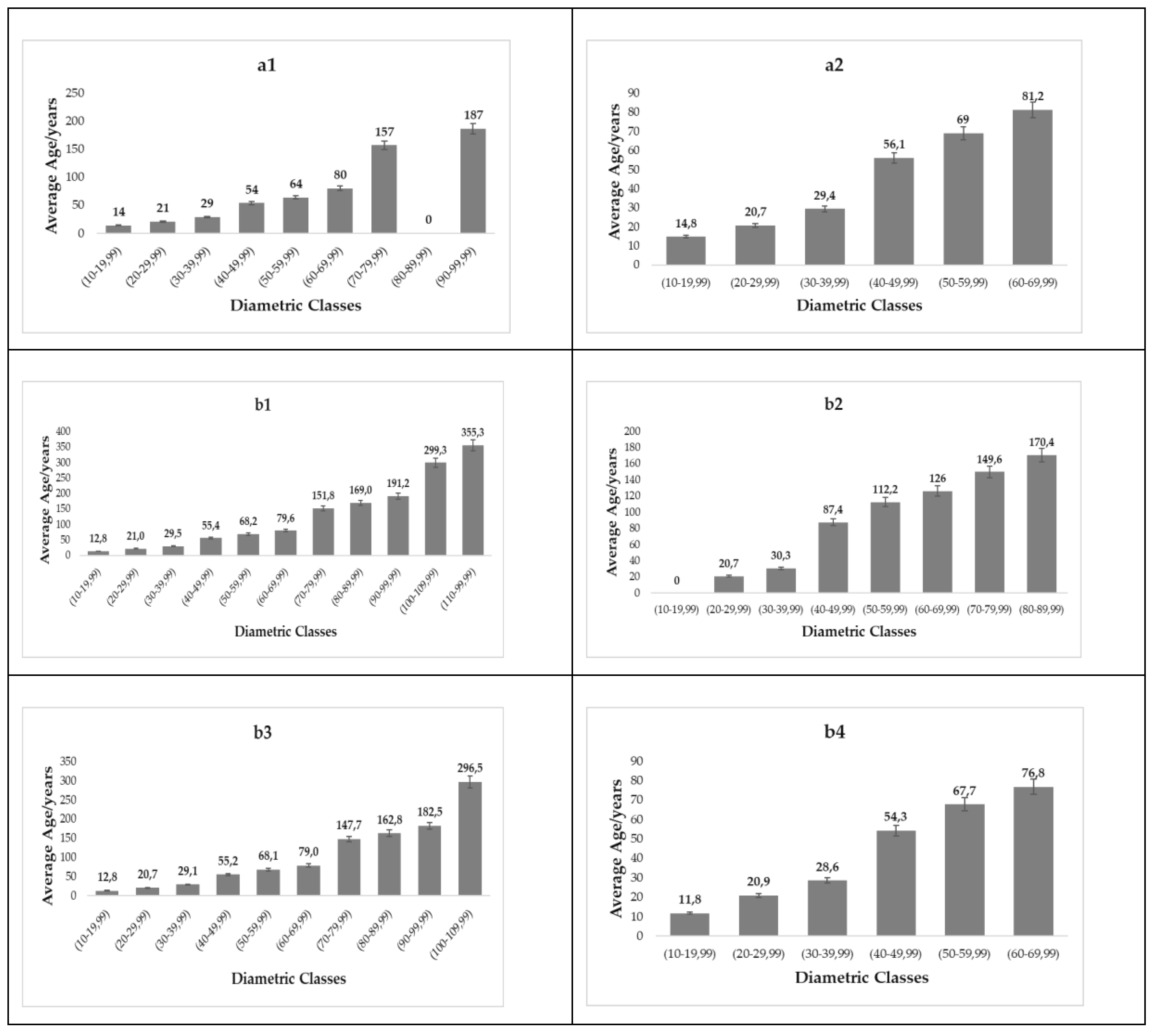

2.6. Determination of the Age of Trees

2.6.1. The Calculation of Transit Time

- a)

- From the field database obtained on the dasometric variable DBH at 1.30m above ground level, each tree from the located provenances was divided into respective diameter classes (Table 2).

- b)

- The Average Current Annual Increment (CAI-A) was calculated for each diameter class.

- c)

- A curve was drawn through these points, adjusting the CAI-A values corrected by the DBH class.

- d)

- The amplitude of each class was divided by its respective corrected CAI-A to obtain the passage time, that is, the time required for an average tree to grow from the lower limit to the upper limit of the diameter class.

- e)

- The passage times were summed to determine the total time required for an average tree to grow from zero to the upper limit of all considered diameter classes.

- f)

- A curve was drawn through these points, adjusting the CAI-A values corrected by the DBH class.

- g)

- The amplitude of each class was divided by its respective corrected CAI-A to obtain the passage time, that is, the time required for an average tree to grow from the lower limit to the upper limit of the diameter class.

- h)

- The passage times were summed to determine the total time required for an average tree to grow from zero to the upper limit of all considered diameter classes.

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

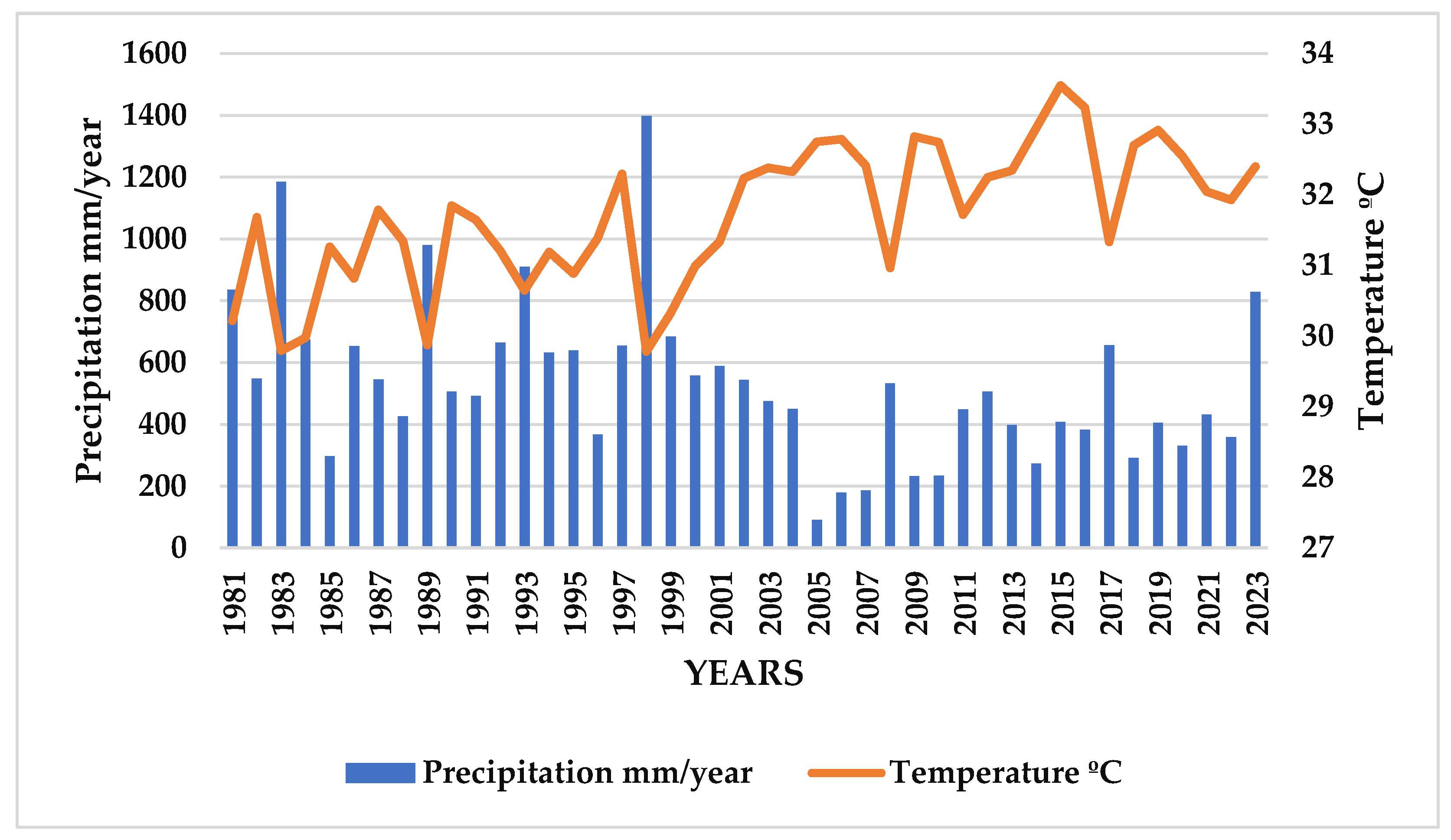

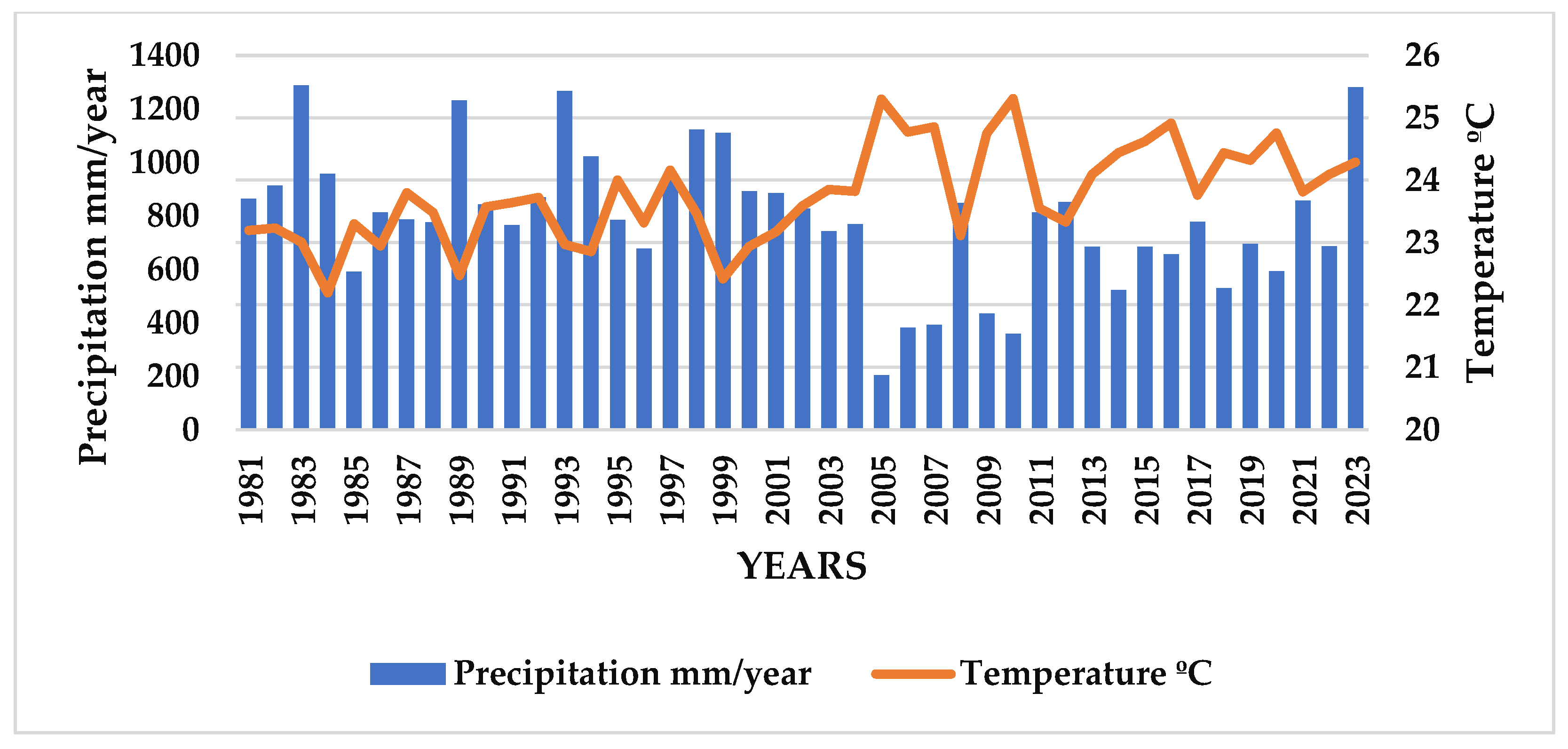

3.1. Climate

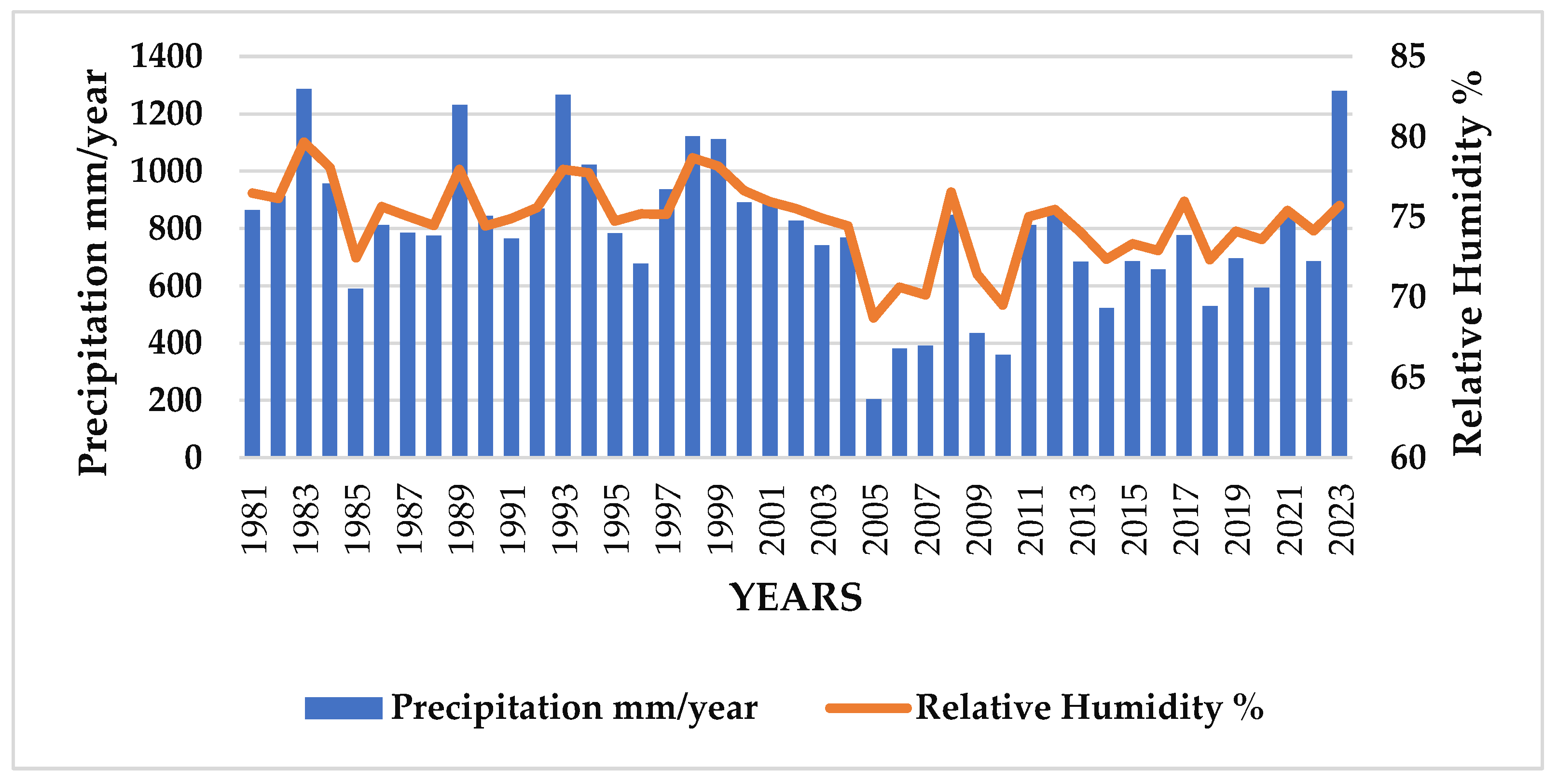

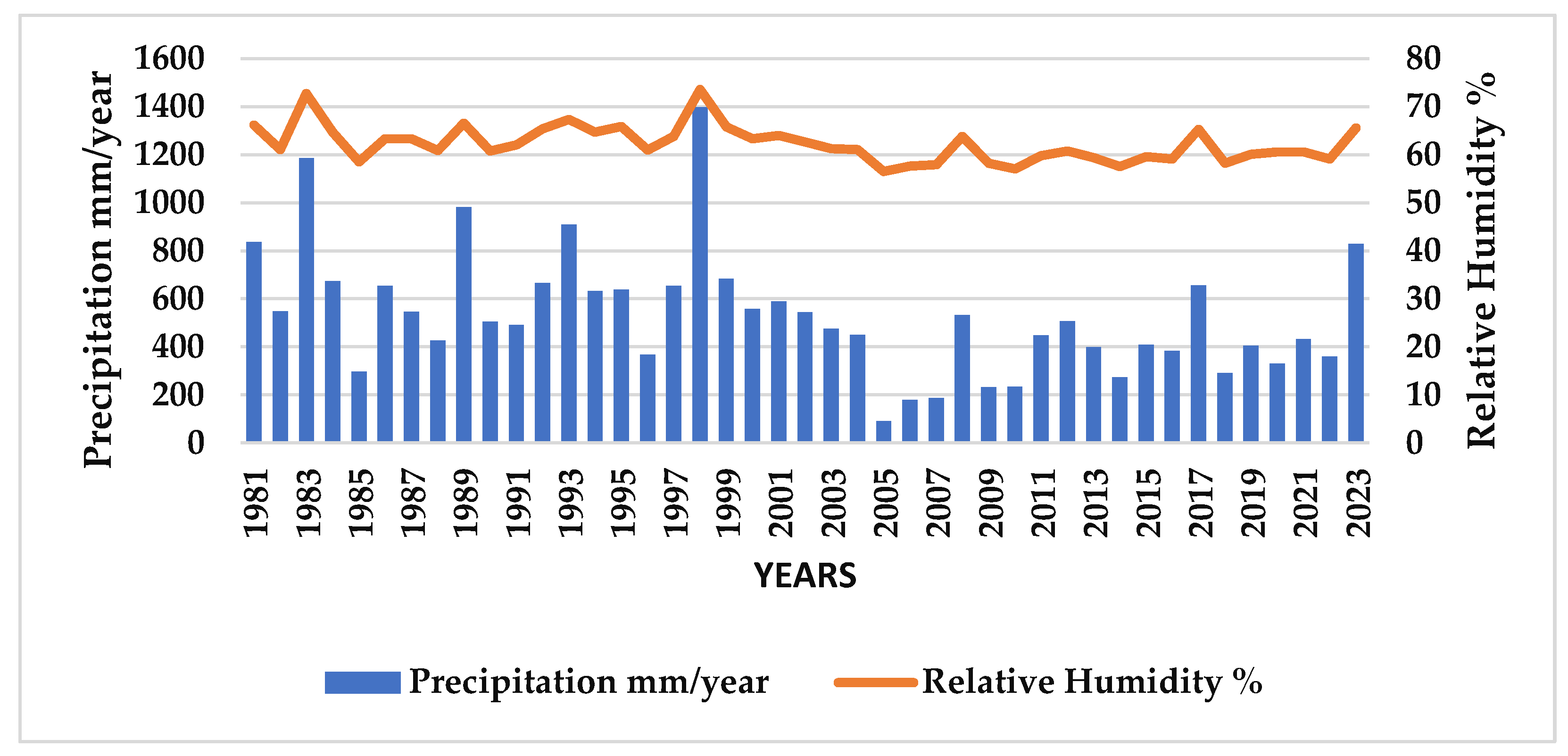

3.2. Precipitation (mm) and Relative Humidity (%)

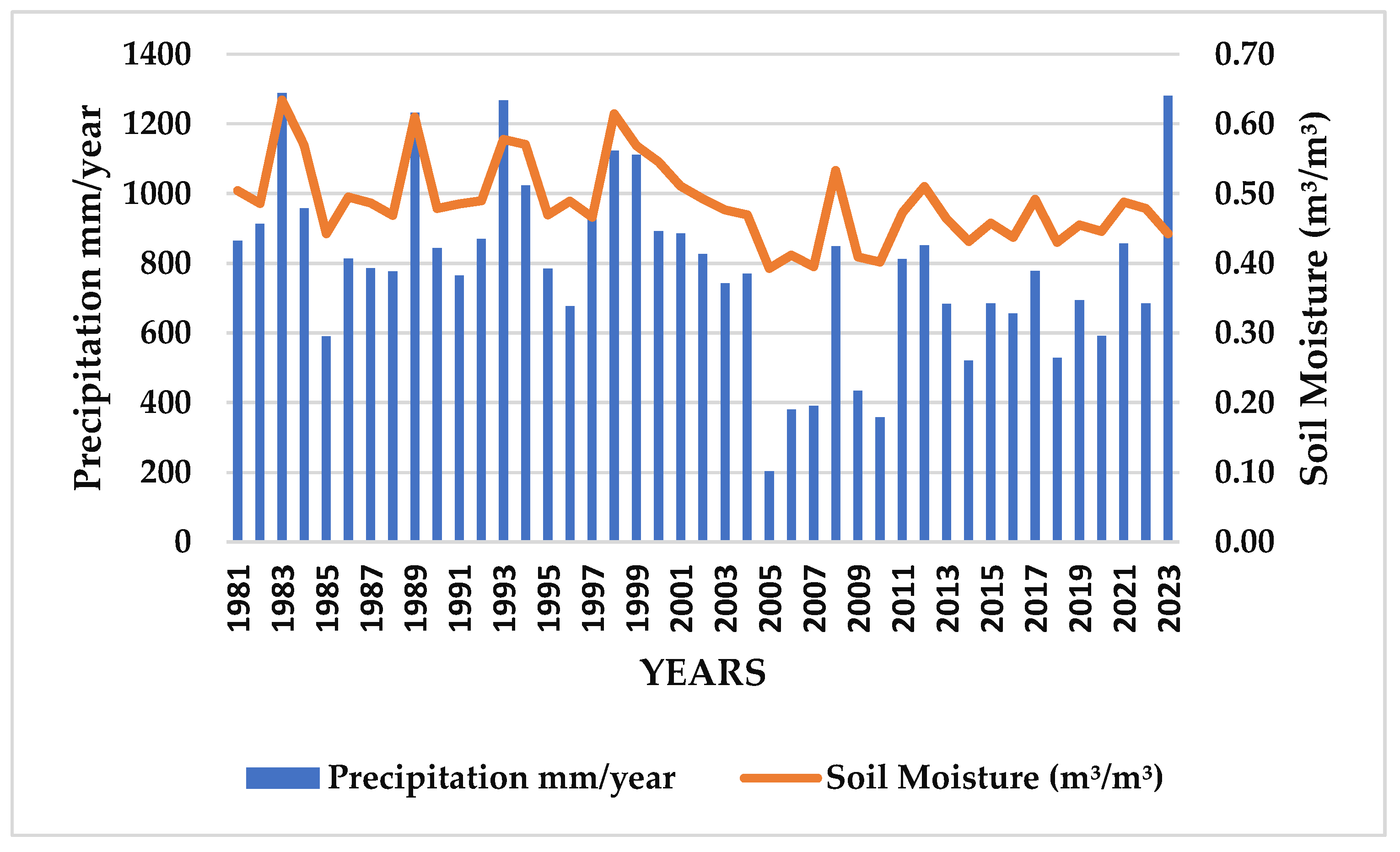

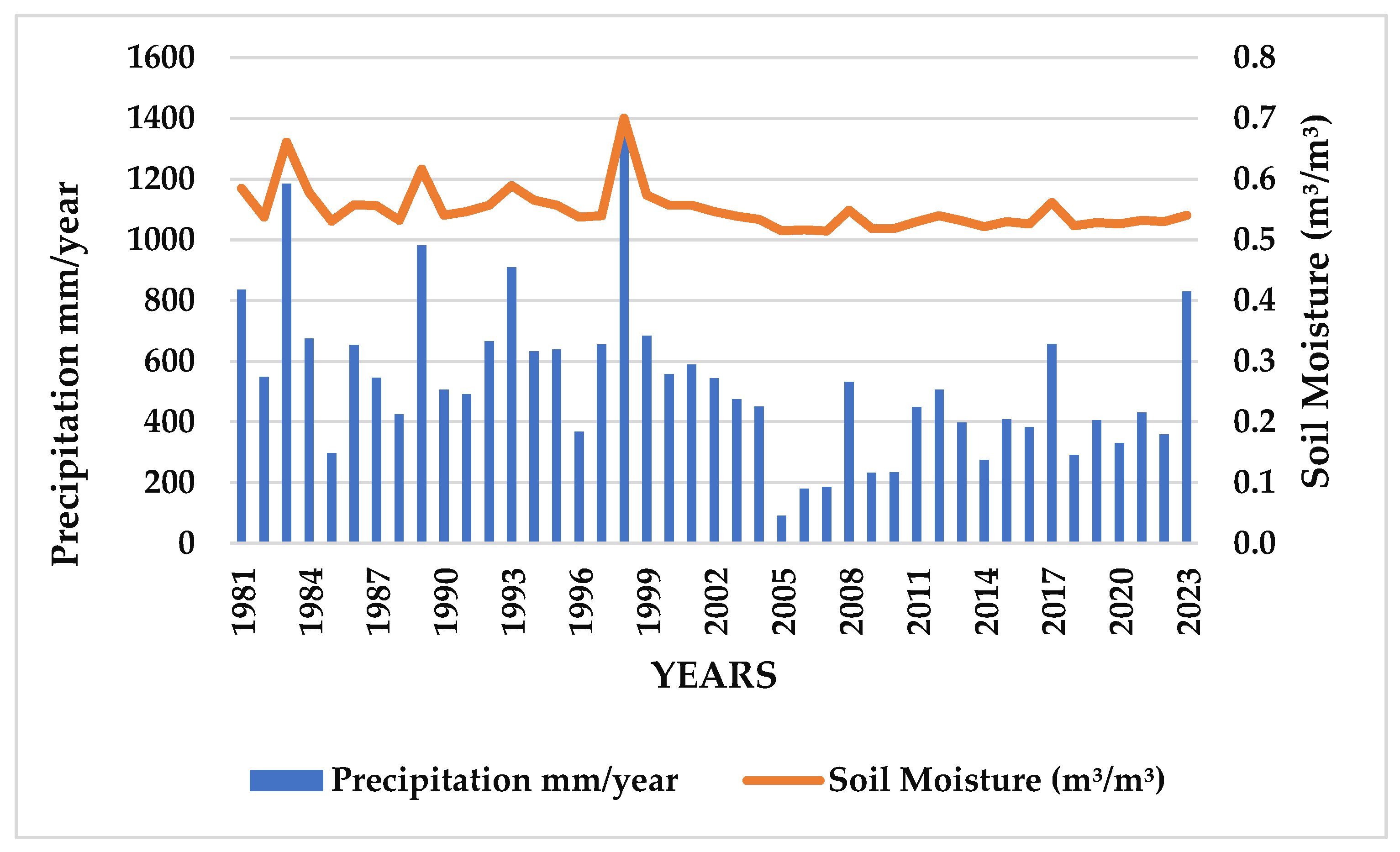

3.3. Precipitation (mm) and Soil Moisture at Root Level (m³/m³)

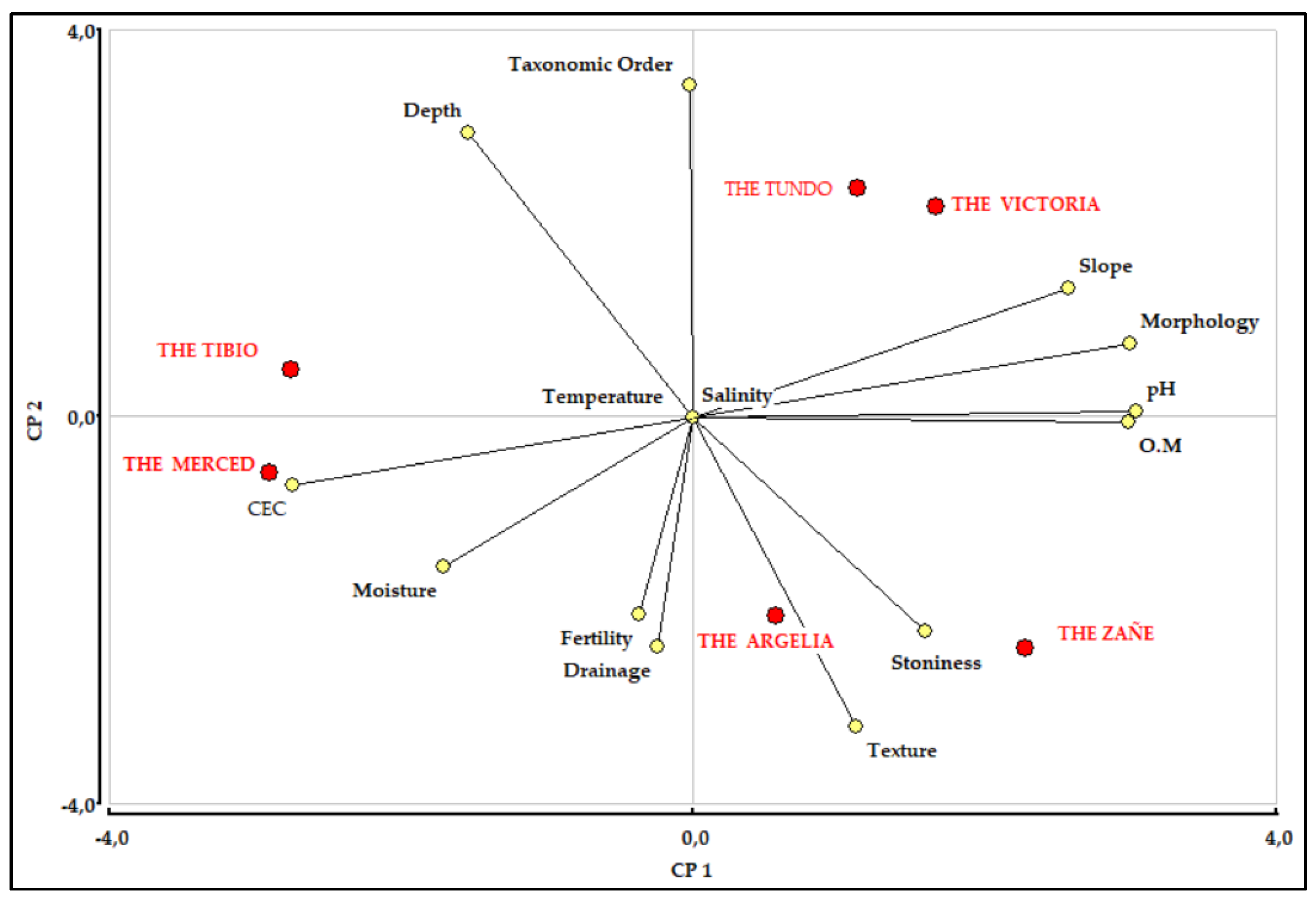

3.4. Soil

| CODE | A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 |

| pH | 6.8 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| CEC meq/100g | 8.0 | 4.0 | 14 | 22 | 25 | 8.0 |

| Fertility | Very low | Very low | Low | Medium | Medium | Low |

| Morphology | Heterogeneous slope | Rectilinear slope | Mountainous relief | Mountainous relief | Mountainous relief | Medium hilly relief |

| Slope | Steep > 40 - 70 % | Steep > 40 - 70 % | Very steep >70% | Very steep >70% | Very steep >70% | Steep > 40 - 70 % |

| Taxonomic Order | Inceptisols | Inceptisols | Alfisols | Alfisols | Entisols | Entisols |

| Texture | Clay loam | Silty clay loam | Clay loam | Clay loam | Loam | Sandy loam |

| Drainage | Good | Good | Moderate | Good | Good | Excessive |

| Depth | Shallow | Shallow | Shallow | Shallow | Superficial | Superficial |

| Stoniness | None | Frequent | Frequent | Few | Abundant | Abundant |

| Salinity | Non-saline | Non-saline | Non-saline | Non-saline | Non-saline | Non-saline |

| Temperature | Isothermal | Isothermal | Isothermal | Isothermal | Isothermal | Isothermal |

| Moisture | Udic | Udic | Ustic | Ustic | Udic | Ustic |

| O.M | High | Low | Low | Medium | Medium | Low |

3.5. Slope

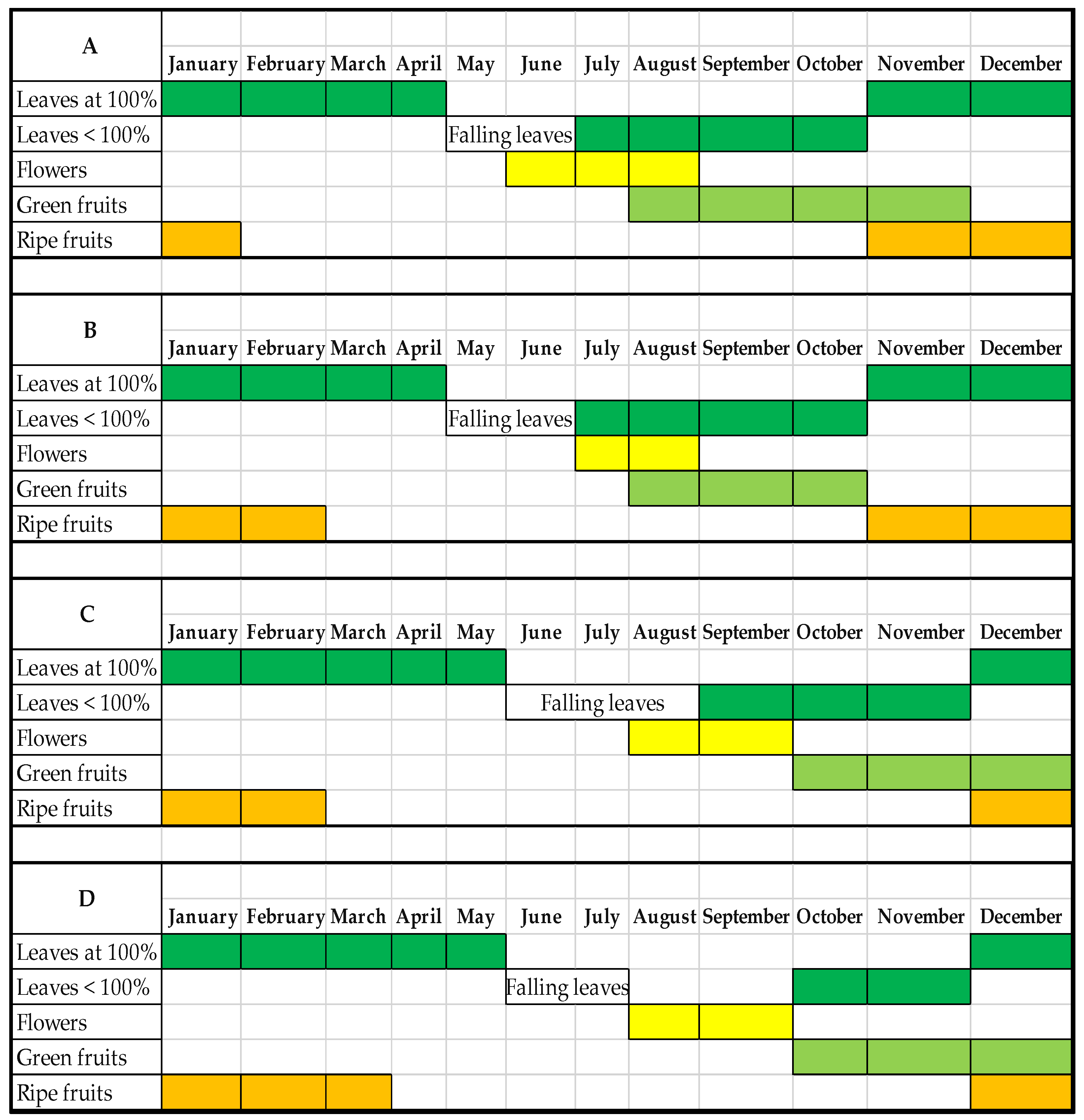

3.6. Phenology

3.7. Age

4. Discussion

4.1. Precipitation and Temperature

4.2. Relative Humidity

4.3. Soil Moisture at a Depth of One Meter (m³/m³)

4.4. Soil

4.5. Slope

4.6. Phenology

4.7. Age

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chávez-García, Alicia Sagrario, Hernández-Ramos, Jonathan, Muñoz-Flores, Hipólito Jesús, García-Magaña, J. Jesús, Gómez-Cardenas, Martín, & Gutiérrez-Contreras, Maribel. (2022). Plasticidad fenotípica de progenies de árboles de Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. superiores en producción de resina en vivero. Madera y bosques, 28(1), e2812381. Epub 05 de septiembre de 2022. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, H. B., & Hernández, J. V. (2004). Variación fenotípica y selección de árboles en una plantación de melina (Gmelina arborea Linn., Roxb.) de tres años de edad. Revista Chapingo. Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente, 10(1), 13-19. [Google Scholar].

- Jara, L. F. (1995). Mejoramiento forestal y conservación de recursos genéticos forestales. Serie técnica. Manual técnico/CATIE; número 14. [Google Scholar].

- Freschet, G.T.; Roumet, C.; Comas, L.H.; Weemstra, M.; Bengough, A.G.; Rewald, B.; Bardgett, R.D.; De Deyn, G.B.; Johnson, D.; Klimešová, J.; et al. Root traits as drivers of plant and ecosystem functioning: current understanding, pitfalls and future research needs. New Phytol. 2020, 232, 1123–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Trugman, A.T.; Badgley, G.; Anderson, C.M.; Bartuska, A.; Ciais, P.; Cullenward, D.; Field, C.B.; Freeman, J.; Goetz, S.J.; et al. Climate-driven risks to the climate mitigation potential of forests. Science 2020, 368, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (Ipcc), I.P.O.C.C. Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Marzilli, P. (2024). Un mundo alterado por las catástrofes y el cambio climático: Uno de los desafíos de la iglesia en el siglo XXI. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Teología, 2(1), 7-19.

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.H.; et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Seidl, R.; Delzon, S.; Corona, P.; Kolström, M.; et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Bahn, M.; Ciais, P.; Frank, D.; Mahecha, M.D.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Zscheischler, J.; Beer, C.; Buchmann, N.; Frank, D.C.; et al. Climate extremes and the carbon cycle. Nature 2013, 500, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, K.; Leinonen, I.; Loustau, D. The importance of phenology for the evaluation of impact of climate change on growth of boreal, temperate and Mediterranean forests ecosystems: an overview. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2000, 44, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicotra, A.; Atkin, O.; Bonser, S.; Davidson, A.; Finnegan, E.; Mathesius, U.; Poot, P.; Purugganan, M.D.; Richards, C.; Valladares, F.; et al. Plant phenotypic plasticity in a changing climate. 2010, 15, 684–692. [CrossRef]

- DORMLING, I. A. Criterios para valoración selección de árboles plus. [Google Scholar].

- Cornejo Oviedo, E. H. , Bucio Zamudio, E., Gutiérrez Vázquez, B., Valencia Manzo, S., & Flores López, C. (2009). Selección de árboles y conversión de un ensayo de procedencias a un rodal semillero. Revista fitotecnia mexicana, 32(2), 87-92.[Google Scholar].

- Suk-In, H. , Moon-Ho, L., & Yong-Seok, J. (2004, November). Study on the new vegetative propagation method ‘Epicotyl grafting’in walnut trees (Juglans spp.). In V International Walnut Symposium 705 (pp. 371-374). [Google Scholar].

- Toro Vanegas, E. , & Roldán Rojas, I. C. (2018). Estado del arte, propagación y conservación de Juglans neotropica Diels., en zonas andinas. Madera y bosques, 24(1). [Google Scholar].

- Weil, R. R. , & Brady, N. C. (2016). The nature and properties of soils, 15th edn., edited by: Fox, D. [Google Scholar].

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 135–150. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez Narváez, R. M. , Capa Benítez, L. B., & Capa Tejedor, M. E. (2019). La Zona 7-Ecuador hacia el desarrollo de ciudades intermedias. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 11(5), 356-361. [Google Scholar].

- Palacios-Herrera, B. , Pereira-Lorenzo, S., & Pucha-Cofrep, D. (2023). Natural and Artificial Occurrence, Structure, and Abundance of Juglans neotropica Diels in Southern Ecuador. Agronomy, 13(10), 2531. [Google Scholar].

- Murray, D. , McWhirter, J., Wier, S., & Emmerson, S. (2003, February). 13.2 the integrated data viewer–a web-enabled application for scientific analysis and visualization. In 19th International Conference on Interactive Information and Processing Systems for Meteorology, Oceanography, and Hydrology. [Google Scholar].

- Ochoa, A.; Campozano, L.; Sánchez, E.; Gualán, R.; Samaniego, E. Evaluation of downscaled estimates of monthly temperature and precipitation for a Southern Ecuador case study. Int. J. Clim. 2015, 36, 1244–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, R. B. , & Espinoza, A. (2017). Guía técnica para muestreo de suelos. [Google Scholar].

- Fernández, D. C. (2001). Clave de bolsillo para determinar la capacidad de uso de las tierras. Araucaria. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Palacios, B. , López, W., Faustino, J., Günter, S., Tobar, D., & Christian, B. (2018). Identificación de amenazas, estrategias de manejo y conservación de los servicios ecosistémicos en Subcuenca “La Suiza” Chiapas, México. Bosques Latitud Cero. Volumen 8, número 1 (Enero-Junio) 2018. [Google Scholar].

- Ramírez, F.; Kallarackal, J. The phenology of the endangered Nogal (Juglans neotropica Diels) in Bogota and its conservation implications in the urban forest. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canizales-Velázquez, P. A. , Aguirre-Calderón, Ó. A., Alanís-Rodríguez, E., Rubio-Camacho, E., & Mora-Olivo, A. (2019). Caracterización estructural de una comunidad arbórea de un sistema silvopastoril en una zona de transición florística de Nuevo León. Madera y bosques, 25(2). [Google Scholar.

- Baque, E.E.L.; Granda, V.D.V.; Chávez, M.D.V. Cambios en patrones de precipitación y temperatura en el Ecuador: regiones sierra y oriente. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Zhou, W., & Du, Y. (2023). Effects of temperature, precipitation, and CO2 on plant phenology in China: a circular regression approach. Forests, 14(9), 1844.

- Vincenti, S.S.; Puetate, A.R.; Borbor-Córdova, M.J.; Stewart-Ibarra, A.M. Análisis de inundaciones costeras por precipitaciones intensas, cambio climático y fenómeno de El Niño. Caso de estudio: Machala. La Granja 2016, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, F. P. (2018). Agroclimatología del Ecuador. Editorial Abya-Yala. [Google Scholar].

- Park, J.; Hong, M.; Lee, H. Phenological Response of an Evergreen Broadleaf Tree, Quercus acuta, to Meteorological Variability: Evaluation of the Performance of Time Series Models. Forests 2024, 15, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Wang, X. Disentangling the Effects of Atmospheric and Soil Dryness on Autumn Phenology across the Northern Hemisphere. Remote. Sens. 2024, 16, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Xu, G.; He, X.; Luo, D. Influences of Seasonal Soil Moisture and Temperature on Vegetation Phenology in the Qilian Mountains. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Lv, H., Fan, W., Zhang, Y., Song, N., Wang, X.,... & Wang, X. (2024). Quantifying the Impacts of Precipitation, Vegetation, and Soil Properties on Soil Moisture Dynamics in Desert Steppe Herbaceous Communities Under Extreme Drought. Water, 16(23), 3490. [Google Scholar].

- Shen, Q.; Tang, C.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Y. Experimental Study of Influence of Plant Roots on Dynamic Characteristics of Clay. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, D. T. , Sánchez, P. C., & Rojas, G. M. (2018). Umbrales en la respuesta de humedad del suelo a condiciones meteorológicas en una ladera Altoandina. Maskana, 9(2), 53-65. [Google Scholar].

- Dusek, J.; Vogel, T. Hillslope-storage and rainfall-amount thresholds as controls of preferential stormflow. J. Hydrol. 2016, 534, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Dutta, S.; Dubey, A.K. An insight into the runoff generation processes in wet sub-tropics: Field evidences from a vegetated hillslope plot. CATENA 2015, 128, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Zeng, J.; Huang, J.; Huang, X.; Liang, F.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X. Effects of Soil Properties and Altitude on Phylogenetic and Species Diversity of Forest Plant Communities in Southern Subtropical China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Fan, S.; Dong, L.; Li, K.; Li, X. Response of Understory Plant Diversity to Soil Physical and Chemical Properties in Urban Forests in Beijing, China. Forests 2023, 14, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llivigañay¬, J.A.V.; Herrera, B.G.P. Estructura, productividad de madera y regeneración natural de Juglans neotropica Diels en la Hacienda la Florencia del Cantón y provincia de Loja. 7, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, T.P.J.; Herrera, B.G.P. Establecimiento de una plantación de nueve especies forestales con fines de rehabilitación de suelos degradados en la hacienda la Florencia en el Cantón y provincia de Loja. 7, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Fu, D.; Li, X. Response of Plant Community Characteristics and Soil Factors to Topographic Variations in Alpine Grasslands. Plants 2024, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gašparović, M.; Pilaš, I.; Radočaj, D.; Dobrinić, D. Monitoring and Prediction of Land Surface Phenology Using Satellite Earth Observations—A Brief Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Herrera, B. G. (2012). Análisis participativo de la oferta, amenazas y estrategias de conservación de los servicios ecosistémicos (SE) en áreas prioritarias de la subcuenca” La Suiza”-Chiapas México. [Google Scholar].

- Azas, R. D. (2016). Evaluación del efecto de los tratamientos pregerminativos en semillas de nogal (Juglans neotropica Diels) en el recinto pumin provincia de Bolívar. Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas, Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, Ecuador. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

- Zuo, X.; Xu, K.; Yu, W.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H.; Ding, A.; Li, Y. Estimation of Forest Phenology’s Relationship with Age-Class Structure in Northeast China’s Temperate Deciduous Forests. Forests 2024, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inga Guillen, J. G. (2011). Turno biológico de corta en Juglans neotropica Diels, a partir del análisis de anillos de crecimiento en selva central del Perú. [Google Scholar].

- Córdova, M. E. E. , Mendoza, Z. H. A., Jaramillo, E. V. A., & Cofrep, K. A. P. (2019). Libro de Memorias.

- Lojan, I. (1992). El verdor de Los Andes. Árboles y arbustos nativos para el desarrollo forestal altoandino. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef].

| Slop (%) | Classification Indices |

| 0 - 15 | 1 |

| 15 - 30 | 2 |

| 30 - 45 | 3 |

| > 45 | 4 |

| REGISTRATION OF TREES BY DIAMETER CLASS | ||||||

|

CLASS I (10-19,99) CLASS n….. |

Nº | Common name | Scientific Name | DBH (cm) | Average /CAI(cm) |

Age/years |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | ||||||

| n.. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).