1. Introduction:

Ethics are fundamental to qualitative research, ensuring the integrity and credibility of a study, especially in research that relies on direct interaction with individuals to understand their experiences and perspectives. The aim of qualitative research is to explore human and social phenomena in depth, which necessitates applying a set of ethical principles to protect participants' rights and preserve their dignity. By adhering to these principles, researchers ensure that studies are conducted in a manner that respects participants' privacy and provides a fair and safe opportunity for their participation. Therefore, ethics are the cornerstone of trust between researchers and participants in qualitative research, producing credible and reliable research results (Sikes, 2021; Smith & White, 2024). However, with the recent dramatic developments that have taken place in technology and the emergence of AI, these ethics need to be reconsidered to determine how or to what extent AI can be implemented in qualitative research. This matter remains controversial and has yet to be clearly stated.

Research involves various processes such as data collection, data analysis, and writing. In each of these stages, the ethics of using AI needs to be clarified, especially as submitting a study for publication usually requires a declaration of whether AI tools have been used to produce the article. In the fields of Applied Linguistics and TESOL, qualitative data are commonly gathered to investigate an existing case and draw conclusions. In this study, an investigation was necessary to understand the perspectives of faculty members regarding the use of AI in qualitative research. In doing so, an attempt was made to answer the following research question:

What are the ethical issues related to implementing AI in qualitative research from the perspective of Applied Linguistics and TESOL researchers?

1.1. Significant Objectives of this Research

This study attempts to meet the following objectives:

To investigate the perspectives of university researchers in the fields of Applied Linguistics and TESOL through a survey of their use of AI to conduct qualitative research.

Establishing ethical considerations for the use of AI in qualitative research.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews the literature on the ethics of using AI in qualitative research, especially in terms of ethical boundaries.

2.1. Ethics of Conducting Qualitative Research

In qualitative research, ethics refers to a set of rules and principles that guide researchers in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of qualitative data, with the goal of safeguarding participants' rights and protecting them from potential harm. These principles include obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, and protecting personal data in addition to treating them in a fair and respectful manner. Ethics in qualitative research also relate to minimizing the researcher's influence on the data and ensuring transparency in the reporting of results. These standards aim to enhance scientific integrity and social justice in studies of individuals' experiences and viewpoints (O’Leary, 2023).

2.1.1. Respect for Autonomy

Respect for autonomy emphasizes the right of participants to make informed, voluntary decisions about their involvement in a study. Therefore, researchers must ensure that participants are fully informed about the study, its purpose, potential risks, and benefits. Meanwhile, participants should be able to consent freely without any coercion and retain the right to withdraw from the study at any time (Noble & Smith, 2022).

2.1.2. Beneficence

Beneficence requires researchers to act in the best interests of their participants by maximizing the potential benefits of a study and minimizing its harm. Therefore, researchers must design studies that avoid any risk of harm, whether psychological, emotional, or physical. Instead, a study should offer participants potential benefits, such as new knowledge or improved practice, and any potential harm should be outweighed by these benefits (Creswell & Poth, 2022).

2.1.3. Non-Maleficence

The principle of non-maleficence asserts that researchers must ‘do no harm’ to their research participants. This not only means avoiding physical, psychological, and emotional harm but also respecting participants’ privacy and ensuring the confidentiality of their information. Moreover, researchers must take care to create a safe environment where participants feel comfortable and free from any distress during the research process (Flick, 2021).

2.1.4. Confidentiality and Privacy

Confidence and privacy are vital ethical principles in qualitative research. Researchers must protect their participants' personal information by securely storing data and limiting access exclusively to authorized individuals. Participants’ identities should remain anonymous, especially when sensitive information is involved, and confidentiality should be maintained throughout the study (Smith & White, 2024).

2.1.5. Integrity

Integrity in qualitative research emphasizes honesty and transparency in all aspects of the study. Therefore, researchers must accurately collect and report data, avoiding manipulation or falsification of information. Likewise, they should present their findings honestly, which will equally mean acknowledging the limitations or inconsistencies of the data. Moreover, researchers should strive to minimize bias throughout the research process (Noble and Smith, 2022).

Transparency in research: Transparency in research is a fundamental principle that ensures the integrity of a scientific study by providing clear and honest information about all aspects of the research, from its design to its results. Researchers must be explicit about the methodologies they use and the reasons for their choices, as well as provide detailed information about the ways in which data were collected and analysed. This transparency allows for the replication of results and verification of their accuracy (Creswell & Poth, 2022).

The disclosure of conflicts of interest is a key aspect of transparency in research. Researchers must be transparent about any external funding or personal interests that could influence the impartiality of a study or its outcomes. This practice helps build credibility and prevents any doubts about the potential impact of external factors on the research results (Smith & White, 2024). The sharing of data in a transparent manner is equally important. The research community and general public should have access to the data and findings obtained during the study. This will facilitate verification of the accuracy of the study and support the progress of future research. It also encourages collaboration between researchers in related fields (Flick, 2021).

Hence, transparency helps prevent the manipulation of data or distortion of research results. By adhering to transparency at all stages of a study, researchers can build greater trust between themselves and the scientific community, thus enhancing the credibility and value of their research in the academic field (Creswell & Poth, 2022).

Justice in qualitative research ethics: Justice is one of the core principles of qualitative research ethics, ensuring the fair and equal treatment of all participants in a study. It requires participants to be selected transparently and without bias, meaning that no individual or group should be favoured or excluded based on factors such as race, gender, social status, or other personal characteristics. Furthermore, justice ensures equal opportunities for all individuals to participate in a study. Thus, no participants faced discrimination or exploitation because of their social or economic circumstances. This principle aims to create an environment that ensures the accurate and inclusive representation of all relevant groups, thereby enhancing the credibility of the research findings and contributing to a better understanding of the phenomena being studied (Flick, 2021).

Practically, justice in qualitative research requires researchers to treat participants with fairness and respect, with no exploitation or bias. For example, researchers must remain aware of participants' social and cultural contexts and avoid any actions that could harm or marginalize certain groups. The data collection and analysis process must also be transparent and unbiased to ensure that the findings reflect reality and are accurate. In particular, researchers must be cautious when dealing with vulnerable or marginalized groups, taking care to avoid exploitation and injustice. By applying the principle of justice, researchers can contribute to the literature by conducting ethical and impartial studies, thereby producing reliable results while simultaneously respecting the rights of all participants (Noble & Smith, 2022).

2.2. Emergence of AI as a Knowledge Provider

Artificial intelligence is a branch of computer science involving the creation of systems and software that can perform tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as understanding, learning, reasoning, and decision-making. Artificial intelligence relies on algorithms and mathematical models to process and analyse data, consequently enabling machines to recognize patterns, make predictions, and interact naturally with humans (Noble & Smith, 2022).

2.2.1. Historical Stages of AI Development

The beginnings (1950s-1960s): The concept of AI emerged with Alan Turing's ‘Turing Test’, designed to evaluate the ability of a machine to think like a human. Early developments included systems capable of solving mathematical problems or playing chess (Kristensen et al., 2024; Singla, 2024).

1970s-1980s: Expert systems were introduced that could provide rule-based advice and solutions. However, the field faces challenges owing to limited computational power and high costs (ibid.).

1990s and beyond: Artificial intelligence saw significant advancements with the rise of machine learning techniques, improved computational capabilities, and access to large-scale data. Practical applications, such as machine translation, facial recognition, and virtual assistants, emerged during this period (ibid.).

2.2.2. Difference Between Narrow and General AI

Narrow AI: Narrow AI focuses on performing specific tasks with high efficiency, such as image classification or language translation. However, these systems lack the flexibility of human thinking and are used in applications such as virtual assistants (e.g., Siri or Alexa).

General AI: The future goal of AI is to develop systems that think and learn like humans, enabling them to perform a wide range of tasks and solve complex problems without direct human intervention. The significance of AI lies in its ability to enhance efficiency and foster innovation in various sectors. For instance, it is used in healthcare for accurate diagnosis and medical imaging analysis and in education to provide personalized learning experiences. In addition,, it accelerates industrial processes and facilitates automation, thereby reducing operational costs. Moreover, AI serves as a critical tool for addressing global challenges, such as climate change and ensuring food security (Bergmann, 2023). To achieve these goals, AI possesses the following technological enhancements that contribute to its ability.

Machine learning and neural networks: Machine learning involves training systems to learn from data and to improve their performance over time without explicit programming. Neural networks, a subset of machine learning, mimic the functioning of the human brain through interconnected layers that process data and identify patterns. These technologies are widely used in applications such as fraud detection, market analysis, and recommendation systems (Reliable Group 2024).

Natural language processing (NLP) and computer vision: Natural language processing (NLP) focuses on enabling machines to understand and analyse human language, allowing for interaction through text or voice. Some examples include machine translation, sentiment analysis, and interactive chatbots. In contrast, computer vision consists of teaching machines that interpret and analyse images and videos. This technology is widely used in facial recognition, medical image analysis, and intelligent surveillance systems (Bergmann, 2023).

2.3. Ethics of Using AI in Qualitative Research Procedures

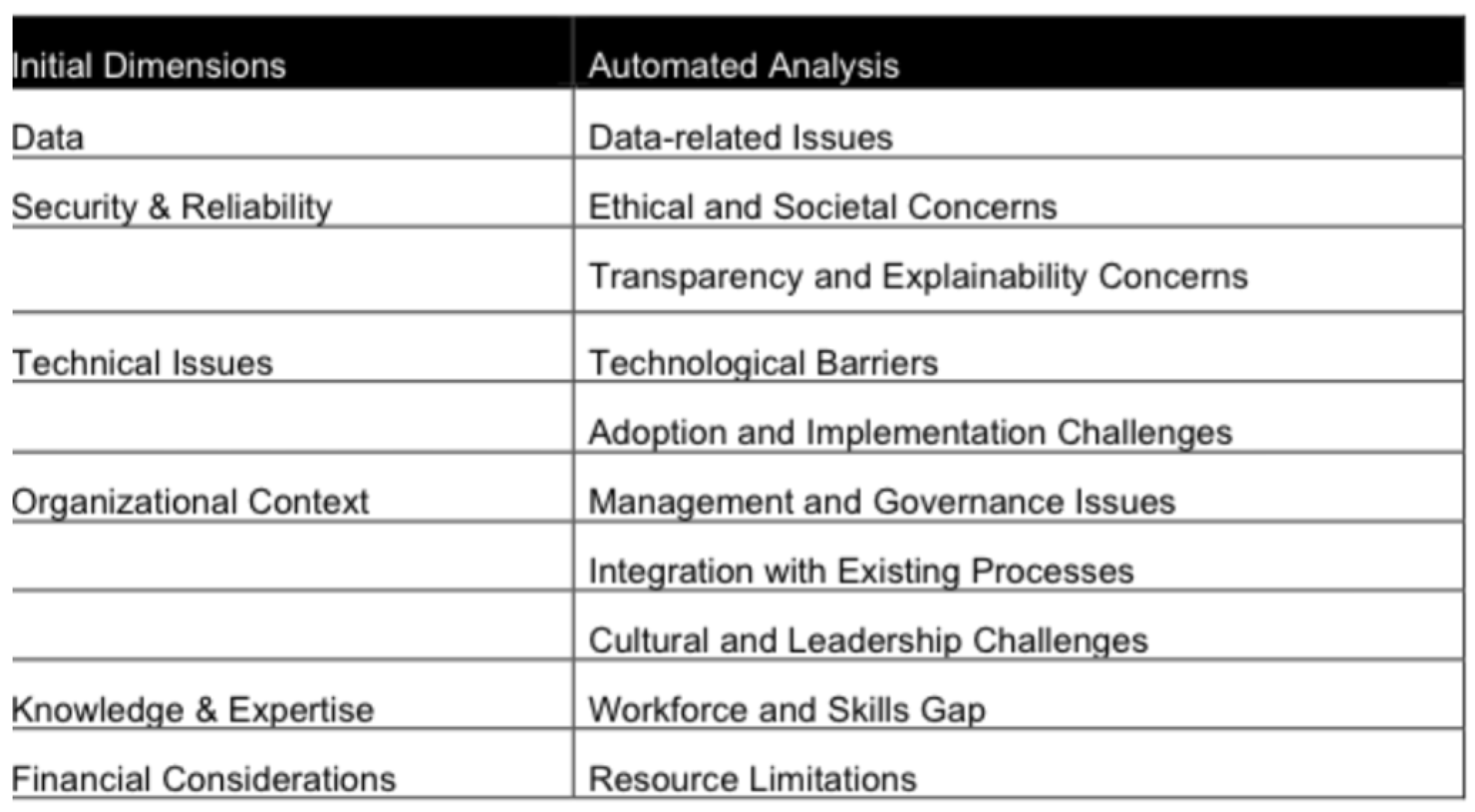

Conducting qualitative research, especially in the field of linguistics, involves a series of complex processes, each requiring data to be successively generated, stored, organized, and analysed to produce suitable results and recommendations. Recent studies have established an important research stream on the use of AI in research, flagging possible ethical concerns. For example, Kerschbaum and Dachs (2024) examined the use of AI in different research processes, such as reviewing the literature and collecting data. They identify the silent challenges mentioned in the extant literature. In their study, Kerschbaum and Dachs categorized the dimensions they considered for analysis: data, security and reliability, technical issues, organizational context, knowledge and expertise, and financial considerations, as illustrated below:

Despite identifying these concerns, Kerschbaum and Dachs failed to specify the number, research design, or research area of the studies reviewed in their methodology. This would suggest that they simply included as many studies as they could find without considering the above-mentioned details, thereby conducting a ‘rapid structure’ literature review, as defined by Armitage & Keeble-Allen (2008). Furthermore, although Kerschbaum and Dachs proposed solutions for each challenge, the ethical considerations for each procedure were not clearly stated, in contrast to the present study.

In another significant study, Marshall and Naff (2024) conducted a survey of a sample of 101 researchers to gather their perceptions of using AI in qualitative research. It was consequently found that researchers largely used AI for transcription purposes, and to a lesser extent, for preliminary coding. Moreover, researchers from high research productivity (R1) universities were generally less accepting of the use of AI in research compared to their counterparts in other universities.

3. Research Design

This case study was conducted in the autumn of 2024. Permission was granted by the heads of departments in the colleges of the included universities. An electronic survey was used, which contained a consent form to obtain participants’ approval. Quantitative analysis of the questionnaire items was performed using mean, standard deviation, percentage, and frequency. Hence, a content analysis of the qualitative data was carried out.

This survey was adapted from Marshall and Naff (2024). Both closed- and open-ended questions were included, together with questions designed to gather the participants’ demographic data, such as their academic position, specialty, research interest, and preferred research design. The second part of the questionnaire concerned three classifications of AI in qualitative research: 1) scribing qualitative data, 2) coding qualitative data, 3) generating findings, and 4) Using AI to write the manuscript. Responses were measured on a six-point Likert scale, with 1= strongly agree and 6= strongly disagree. However, two open-ended questions were also included, inviting the participants to express their concerns about AI and any benefits discerned in its application to research. As such, the survey contained three banks of items, each asking the participants to offer their perspectives of using AI for the purposes of transcription, coding data, generating findings, and writing.

3.1. Reliability

In this study, it was important to assess the reliability of the questionnaire instrument, as it would determine the quality of the data gathered and, therefore, the robustness of the research. Reliability refers to the degree of consistency or stability in the research results if a study is conducted among the same or similar respondents on repeated occasions.

To evaluate the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha values were calculated for each dimension. Cronbach’s alpha (α), developed by the educational psychologist Lee in 1951 (Shavelson, 2015), is the most commonly applied estimate of reliability in this regard. It is based on the inter-correlation of observed indicator variables and results in values between 0 and 1, with an acceptable range of 0.7 and 1.

The above Table demonstrates that the data passed the reliability test, as all Cronbach’s alpha values exceeded the acceptable value: the Cronbach's alpha value for the questionnaire was .966 (hence, more than 0.7).

The study sample consisted of 99 participants, all of whom were faculty members at two major Saudi universities. These universities were selected because both the present researchers are members of faculties within them, which was anticipated to facilitate the data collection process. Male and female faculty members were invited to participate. These participants either specialized in Applied Linguistics or TESOL. A link was sent to the Heads of Department in each institution so that this link could be disseminated to faculty members.

Therefore, random sampling was applied to the two selected universities. The main characteristics of the sample are presented in

Table 3, which provides participants' personal information, such as gender, academic position, institution, and specialty.

4. Results:

This study investigated ethical issues related to the implementation of AI in Applied Linguistics and TESOL research. Accordingly, the following question was addressed.

What are the ethical issues related to implementing AI in qualitative research from the perspective of Applied Linguistics and TESOL researchers?

4.1. Quantitative Analysis

Table 4 illustrates participants' varied opinions on the use of AI in academic research. These opinions fell into four main categories. The first showed that the participants possessed a good level of knowledge about AI and generally agreed on its benefits for conducting research (mean =4.20, percentage =69.9%), reflecting a” somewhat agree’ practice level. The second category was concerned with intentions to use AI, whereby the participants expressed a willingness to use AI for transcription but showed reservations about using it for the entire coding process or for generating findings and writing papers. The level of agreement decreased significantly for this category, with an overall mean of 55.8%, indicating a ‘somewhat disagree’ stance. Ethically, the third category revealed the participants' hesitation to rely comprehensively on AI, particularly to write papers or produce research findings (total agreement=50.2%), thereby reflecting a somewhat disagree’ practice level. Lastly, concerning recommendations in academic review, there was relative acceptance of preliminary coding with AI but strong disagreement with using AI to write a paper or generate final findings (indicating the lowest agreement at 35.9%). The overall mean across the categories (3.17) and percentage of total agreement (52.9%) indicated a general position of” somewhat disagree’ with regard to the full integration of AI use into academic research. Thus, it may be deduced that while the participants recognized some benefits of AI for specific tasks, ethical concerns remained regarding its full application to produce academic results

.

Consequently,

Table 4 reveals a general positive agreement on the benefits of AI for certain research activities such as transcription and preliminary coding. However, there is a clear reservation over the complete reliance on AI to generate findings and write papers, with the participants expressing ethical concerns about these advanced applications of AI in academic research.

4.2. Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative data were analysed based on responses to the following questions:

Responses to these questions are presented below.

4.2.1. Benefits of Using AI in Qualitative Research?

The use of AI in qualitative research offers several benefits, with timesaving and efficiency being the most frequently mentioned advantages, accounting for 25% of responses. The use of AI in research significantly reduces the effort required for tasks such as transcription, coding, and data analysis, allowing researchers to devote themselves to interpret the results. Another important benefit is the enhanced accuracy, which was highlighted by 20% of the participants. Researchers can use AI tools to process large amounts of data with precision, thereby minimizing human errors and identifying patterns that might otherwise be overlooked. Additionally, idea generation and inspiration were noted by 15% of the respondents as key benefits, since AI supports mind-mapping and the exploration of ideas and helps refine research frameworks. Other advantages include improving the writing and analysis process (10%) and reducing human bias (7.5%) to obtain more objective results. Some respondents (12.5%) mentioned the ability of AI to assist with literature reviews and academic tasks, while 10% highlighted its general organizational and scalability benefits. These findings illustrate how AI can transform qualitative research by increasing productivity and enhancing the quality of analysis.

Therefore, both the quantitative and qualitative results reflect a dual perspective among the participants, who appeared to view AI as a valuable tool for timesaving and streamlining preliminary processes, particularly in initial coding and categorization. However, the respondents were still cautious about relying completely on AI to conduct qualitative analysis, which demands human interpretation to ensure accuracy and authenticity.

4.2.2. Concerns Over Using AI in Qualitative Research

Thus, while AI offers many advantages in qualitative research, it also raises several concerns, the most frequently mentioned being its reliability and authenticity, which accounted for 22.5% of the responses. Many participants were worried that AI would generate results that lacked authenticity or failed to capture the depth and nuance required in qualitative studies. Other key concerns raised by 20% of the respondents were accuracy and credibility, as AI could misinterpret complex or ambiguous data, thereby producing misleading findings. Additionally, over-reliance on AI was highlighted by 15% of the participants, with fears that researchers would depend too heavily on AI tools, potentially diminishing the role of human judgement.

Ethical and legal issues were also noted, representing 12.5% of the responses. These issues included concerns about intellectual property and misuse of AI-generated content. Furthermore, risks to future research were indicated by 17.5% of the respondents, who were apprehensive that the overuse of AI would cause a decline in the creativity and originality of research. Finally, a lack of depth in the results accounted for 12.5% of the responses, as AI tools could oversimplify findings or miss critical contextual nuances.

These concerns underscore the need for a balanced approach, with AI serving as a complementary tool, rather than fully replacing human expertise in qualitative research. Overall, both the quantitative and qualitative results revealed a common concern among the participants regarding excessive reliance on AI in qualitative research. This reliance, they fear, could lead to superficial interpretations, loss of authenticity, and ethical issues relating to intellectual property and plagiarism.

5. Discussion

Linking the quantitative results with the benefits of using AI in research, as cited by participants, revealed a clear alignment between the qualitative and quantitative findings regarding the effectiveness of AI in saving time and effort. In the quantitative analysis, there was a significant agreement on the effectiveness of AI use for routine tasks, such as the initial transcription of data. These items elicited a high percentage of agreement, indicating general acceptance of AI use in tasks that do not require extensive human intervention.

However, the concerns expressed in the qualitative responses aligned with the quantitative findings, which showed lower agreement with the use of AI for more complex tasks, such as generating qualitative findings or writing an entire research paper. These items elicited a relatively low rate of agreement (38.4% and 52.5%, respectively), thereby indicating participants' reservations about relying on AI for tasks that require in-depth understanding and a precise qualitative context.

In linking the qualitative concerns expressed by the participants with the quantitative findings, a clear alignment was found in terms of general caution over the use of AI in qualitative research, especially for tasks requiring deep understanding and nuanced interpretation. The quantitative results demonstrated that the participants were hesitant to depend entirely on AI for processes such as writing research papers or conducting a comprehensive qualitative data analysis. For instance, the items ‘Using AI to write a qualitative paper’ and ‘Using AI to generate qualitative findings’ elicited low levels of agreement, with percentages of 38.4% and 52.5%, respectively. This revealed a tendency to Disagree’ or ‘Somewhat disagree with the use of AI for tasks that typically rely on a high degree of human intervention.

These quantitative findings align with the qualitative concerns raised by the participants, who expressed doubts about the accuracy and authenticity of the AI-generated material, along with ethical concerns related to plagiarism and reduced human input. Qualitative comments about the risk of ‘superficial interpretations’ and ‘over-reliance’ on AI also mirror the results derived from the ‘Intentions to Use AI’ section of the questionnaire, where the overall level of agreement was relatively low (55.8%). This suggests a shared reservation among the participants regarding AI use. Meanwhile, the results of the statistical analysis highlighted differences in responses from the study sample based on several demographic variables, namely gender, academic position, institution, specialty, and type of research conducted. The key findings for each category are summarized below.

5.1. Gender

No statistically significant differences were found between the male and female respondents in terms of their ‘Knowledge of AI’ (P=0.646), ‘Intentions to Use AI’ (P=0.365), ‘Ethical Perspectives of AI Use’ (P=0.272), or ‘Acceptance Recommendations in Academic Review’ (P=0.628). This indicated that gender differences were not statistically significant across any of the dimensions related to AI.

5.2. Academic Position

Statistically significant differences were observed for the ‘Intentions to Use AI’ (P=0.045), ‘Acceptance Recommendations in Academic Review’ (P=0.000), and the overall AI score (AI ALL) (P=0.003). The Assistant Professors tended to rate agreement with AI use higher in the dimension of acceptance recommendations compared to professors, consequently indicating that academic rank could influence approaches to AI use.

5.3. Institution

Statistically significant differences were found for AI knowledge (P=0.000) between faculty members from Imam Mohammed ibn Saud Islamic University and King Abdulaziz University. This indicates a notable variation in the level of AI knowledge across different institutions, with the faculties at Imam Mohammed ibn Saud Islamic University asserting a greater knowledge of AI.

5.4. Specialty

Statistically significant differences were found for Knowledge of AI (P=0.000) across different specialties, with fields such as Theoretical Linguistics and Applied Linguistics indicating a higher average level of AI knowledge. This suggests that researchers in some fields, such as linguistics, possess deeper knowledge of AI than researchers in other fields.

5.5. Type of Research Conducted

Significant differences were found across almost all dimensions, including Knowledge of AI (P=0.004), AI Utilization Intentions (P=0.004), Ethical Perspectives of AI Use (P=0.002), Acceptance Recommendations in Academic Review (P=0.012), and the overall AI score (P=0.002). These results indicate notable differences in attitudes towards AI based on the type of research conducted, with researchers who engage in quantitative research tending to evaluate AI more positively across several dimensions.

5.6. Evaluating Differences in opinions between faculty members

Differences in responses between senior and associate or assistant academic staff members were identified in this study. The more senior academic staff members were less accepting of AI use in various aspects of qualitative research than their lower-ranking colleagues, thereby corroborating Marshall and Naff (2024). Awareness of these differences could help establish more common ethical perspectives, whether in organizational terms or with regard to publication.

At present, while some journals demand a declaration that AI has not been used to produce a submitted article, or else request disclosure of AI use, they do not specify how AI could legitimately be used. Notably, AI can help with the storage, retrieval, and analysis of data, particularly in the coding of qualitative data, as mentioned by the participants. However, this could put the data security at risk. Thus, one solution would be to clarify to the participants that AI would be used to deal with data in different ways, one of which could be translated. This would render the practice ethical in terms of protecting participants’ rights, but might not be acceptable to journals.

To formulate an ethical framework that clearly states the possibility of using AI to generate reliable research findings, it is necessary to engage IT expertise in developing appropriate AI software. Given the rapid advancements that have taken place in the field of AI in recent years, this study represents an urgent call for researchers and journals to participate in defining a code of AI ethics to set its limits. In the specific field of linguistics and in dealing with real human data, an AI system should be able to collect and analyse data accurately, considering the different contexts and differences between personal, mental, and cultural properties. This is difficult to achieve with existing AI technology, although it could be proposed for reliable future use of AI in research. Hence, establishing ethical guidelines for AI use in research is essential to ensure that dependence on AI is controlled. This avoids hindering technological processes while at the same time maintaining creative human input.

6. Conclusion

Based on the research results, factors such as academic position, institution, specialty, and research type appear to significantly influence faculty members' attitudes toward AI and their stance on its use in research processes, particularly intentions to use it, knowledge of AI, and acceptance recommendations in academic reviews. However, determining the ethical boundaries of AI in research requires further investigation. It may be impractical to recommend the total exclusion of its use in qualitative research, as AI tools can be helpful for data storage, data analysis, and text translation, as mentioned by the participants in this study. Conversely, the participants asserted that literature reviews and the writing up or discussion of results should be carried out by human researchers with no interference from AI to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data analysis.

Appendix A

Table 7.

Statistical differences in faculty responses about AI by demographic and academic variables using one-way ANOVA (N=99).

Table 7.

Statistical differences in faculty responses about AI by demographic and academic variables using one-way ANOVA (N=99).

| |

Variables |

Categories |

N |

Mean |

Std |

F |

P Value |

| What is your academic position at your institution? |

Knowledge of AI |

Assistant Professor |

54 |

4.08 |

1.054 |

0.557 |

0.644 |

| Associate Professor |

36 |

4.33 |

1.000 |

|

|

| Professor |

6 |

4.25 |

0.274 |

|

|

| Teaching Assistant |

3 |

4.50 |

0.000 |

|

|

| Intentions to use AI |

Assistant Professor |

54 |

3.54 |

1.025 |

2.789 |

0.045 |

| Associate Professor |

36 |

3.20 |

0.872 |

|

|

| Professor |

6 |

2.50 |

0.110 |

|

|

| Teaching Assistant |

3 |

3.20 |

0.000 |

|

|

| Ethical perspectives of AI use |

Assistant Professor |

54 |

3.14 |

1.103 |

2.475 |

0.066 |

| Associate Professor |

36 |

2.97 |

0.903 |

|

|

| Professor |

6 |

2.00 |

0.000 |

|

|

| Teaching Assistant |

3 |

3.20 |

0.000 |

|

|

| Acceptance recommendations in academic review |

Assistant Professor |

54 |

3.34 |

0.689 |

8.277 |

0.000 |

| Associate Professor |

36 |

3.03 |

1.168 |

|

|

| Professor |

6 |

1.70 |

0.767 |

|

|

| Teaching Assistant |

3 |

4.40 |

0.000 |

|

|

| TOTAL |

Assistant Professor |

54 |

3.34 |

0.873 |

4.882 |

0.003 |

| Associate Professor |

36 |

3.07 |

0.819 |

|

|

| Professor |

6 |

2.07 |

0.219 |

|

|

| What is your specialty? |

Knowledge of AI |

Theoretical Linguistics |

6 |

4.50 |

1.095 |

12.781 |

0.000 |

| English Literature |

6 |

2.25 |

1.369 |

|

|

| Translation Studies |

36 |

4.08 |

0.824 |

|

|

| Applied Linguistics |

51 |

4.47 |

0.764 |

|

|

| Intentions to use AI |

Theoretical linguistics |

6 |

3.60 |

0.438 |

0.838 |

0.477 |

| English Literature |

6 |

3.40 |

0.219 |

|

|

| Translation Studies |

36 |

3.15 |

0.911 |

|

|

| Applied Linguistics |

51 |

3.45 |

1.068 |

|

|

| Ethical perspectives of AI use |

Theoretical Linguistics |

6 |

3.30 |

0.767 |

0.604 |

0.614 |

| English Literature |

6 |

2.70 |

0.110 |

|

|

| Translation Studies |

36 |

2.90 |

1.109 |

|

|

| Applied Linguistics |

51 |

3.09 |

1.023 |

|

|

| Acceptance recommendations in academic review |

Theoretical Linguistics |

6 |

3.20 |

0.876 |

0.741 |

0.530 |

| English Literature |

6 |

3.40 |

0.438 |

|

|

| Translation Studies |

36 |

3.32 |

0.992 |

|

|

| Applied Linguistics |

51 |

3.02 |

1.041 |

|

|

| TOTAL |

Theoretical Linguistics |

6 |

3.37 |

0.694 |

0.142 |

0.935 |

| English Literature |

6 |

3.17 |

0.110 |

|

|

| Translation Studies |

36 |

3.12 |

0.916 |

|

|

| Applied Linguistics |

51 |

3.19 |

0.915 |

|

|

| What type of research do you typically engage in? |

Knowledge of AI |

Mostly qualitative |

15 |

3.70 |

0.775 |

4.792 |

0.004 |

| Both quantitative and qualitative (including mixed methods) |

69 |

4.15 |

1.023 |

|

|

| Mostly quantitative |

12 |

4.75 |

0.584 |

|

|

| Exclusively qualitative |

3 |

5.50 |

0.000 |

|

|

| Intentions to use AI |

Mostly qualitative |

15 |

3.92 |

0.622 |

4.753 |

0.004 |

| Both quantitative and qualitative (including mixed methods) |

69 |

3.36 |

1.015 |

|

|

| Mostly quantitative |

12 |

2.60 |

0.467 |

|

|

| Exclusively qualitative |

3 |

3.20 |

0.000 |

|

|

| Ethical perspectives of AI use |

Mostly qualitative |

15 |

3.76 |

1.217 |

5.231 |

0.002 |

| Both quantitative and qualitative (including mixed methods) |

69 |

2.98 |

0.947 |

|

|

| Mostly quantitative |

12 |

2.35 |

0.633 |

|

|

| Exclusively qualitative |

3 |

2.60 |

0.000 |

|

|

| Acceptance recommendations in academic review |

Mostly qualitative |

15 |

3.88 |

1.146 |

3.835 |

0.012 |

| Both quantitative and qualitative (including mixed methods) |

69 |

3.06 |

0.900 |

|

|

| Mostly quantitative |

12 |

3.05 |

1.038 |

|

|

| Exclusively qualitative |

3 |

2.40 |

0.000 |

|

|

| TOTAL |

Mostly qualitative |

15 |

3.85 |

0.935 |

5.357 |

0.002 |

| Both quantitative and qualitative (including mixed methods) |

69 |

3.13 |

0.829 |

|

|

| Mostly quantitative |

12 |

2.67 |

0.625 |

|

|

| Exclusively qualitative |

3 |

2.73 |

0.000 |

|

|

References

- Armitage, A.; Keeble-Allen, D. Undertaking a structured literature review or structuring a literature review: Tales from the field. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 2008, 6, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, D. (2023). The most important AI trends in 2024. IBM. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/insights/artificial-intelligence-trends?mhsrc=ibmsearch_a&mhq=the%20top%20artificial%20intelligence%20trends.

- Creswell, J. W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An introduction to qualitative research, 6th ed. Sage Publications, 2021.

- Kerschbaum; Dachs, D. (2024). Challenges in AI implementation: Perspectives from practice and research [Conference paper]. 4th International Conference on AI Research (ICAIR), 5-6 December 2024, Lisbon.

- Kristensen, I.; Bevan, O.; Brown, S. (2024). Managing the risks around generative AI [Podcast]. McKinsey & Company. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/managing-the-risks-around-generative-ai.

- Marshall, D.T.; Naff, D.B. The ethics of using artificial intelligence in qualitative research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 2024, 19, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslej, N. (2024). Presenting the 2024 AI Index [Video-recorded seminar]. Stanford Human-centered AI Institute (Stanford HAI). 2024. Available online: https://hai.stanford.edu/events/presenting-2024-ai-index.

- Noble, H.; Smith, J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence Based Nursing 2022, 25, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, Z. The essential guide to doing your research project, 5th ed.; Sage Publications, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Reliable Group. (2024). AI 2024: Predictions and advances in artificial intelligence [Blogpost]. Available online: https://www.reliablegroup.com/blog/ai-2024-predictions-and-advances-in-artificial-intelligence/.

- Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Cronbach, Lee, J. (2016-2001) [Obituary], in Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology (pp. 360–361). Wiley.

- Sikes, P. Researching education from a qualitative perspective: Ethical considerations, 2nd ed.; Routledge, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Singla, A. (2024). The state of AI in early 2024: GenAI adoption spikes and starts to generate value. Quantum Black AI by McKinsey. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai.

- Smith, L.; White, S. Ethical challenges in qualitative research: Contemporary perspectives. Qualitative Research 2024, 24, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).