1. Introduction

Digital technologies have proven their effectiveness in optimising learning in various specific areas of human and professional activity. The ability to use artificial intelligence (AI) tools to understand and respond to diverse user questions, developed today by countless users, highlights their versatility and adaptability, creating new interaction experiences [

1]. The aim of this study is to critically analyse the growing integration of artificial intelligence in the academic and research fields. To this end, it reviews relevant works that show how to define and implement lines of action where ethical frameworks, guidelines, orientations in the use of artificial intelligence tools and pedagogical strategies are defined and implemented, with the purpose of promoting ethical responsibility, guaranteeing academic integrity; and, preserving reliability in the authentic transfer of knowledge. It collects and highlights the orientations and guidelines obtained in the literature from studies conducted during 2024 and January 2025. In addition, this study serves as a reference for a follow-up of the contributions made by certain authors in their critical and reflective works, focused on responsibility and consequences in the use of artificial intelligence.

Recent studies suggest that the integration of AI-driven feedback will optimise the management of the learning process and, in the near future, the application of AI in specific tasks will become imperative [

2]. However, there are also critical voices that indicate, for example, that in key areas such as writing development, it is necessary to prioritise strategies, guidance and resources that prevent any possible regression in users’ skills [

3].

Indeed, given the ease of access to information today, as well as AI tools, incorrect, inappropriate or false content is massively generated and transmitted. Many users are amazed at how AI technologies seem to effectively generate content and improve their writing based on the texts provided to them [

4]. But there are concerns about the transparency and credibility of the actions of those who use AI, for research in particular, if their practice involves not critically examining the results but - on the contrary - assuming them to be true or valid [

5].

It should be recognised, in this sense, that the greater the apparent or useful value of the information a user obtains from AI systems, the greater the risk of a pattern of dependency that compromises their autonomy and critical judgement [

6]. Some authors, in fact, argue that there is an unethical pattern of behaviour in the use of AI tools, with the challenge being the difficulty in detecting false information, despite advances in certain tools [

7]. Thus, the use of AI in the production of scientific texts has become increasingly visible, raising the idea of its control, limitation or containment. At the same time, innovative strategies for plagiarism detection are being tested, developed by researchers seeking to publicly expose dishonest practices [

7].

Recognising that lack of expertise in scientific writing is a reality, particularly in undergraduate university contexts, rather than extending the practice of automatic content generation with AI, the way forward is to generate discussions about how AI can positively influence learning and the development of academic writing competence.

However, the extensive use that is being made of this technology makes the detection of AI use in student work increasingly complex. In this sense, the ability of students and professionals in all university fields to integrate originality and an identifiable writing style into their texts are remaining challenges for the detection of AI-generated work [

8]. Indeed, the discussion about how to establish the principles and appropriate conditions for the use of AI tools in academic and research environments or, more generally, in learning environments. Indeed, it discusses the prevention and responsibility of the user in possible conflict situations, aiming to develop an ethical use of research progress [

9].

Based on this, two questions were established to guide this work:

What are the existing conceptual and practical contributions in the scientific literature that address ethical responsibility when integrating AI tools in academic and research settings?;

What AI tools have been used and researched, and with what approach, in these contributions?

2. State of de Art

Digital technologies have proven to be effective in optimising learning in various disciplinary areas. Not only in terms of content, but also in methodological aspects, such as writing. In this area it is necessary to prioritise strategies and resources that prevent any possible regression in students’ skills [

3]. Indeed, writing is a highly complex skill and an AI tool could prioritise its evaluation on structure or correctness over original content or the development of analytical thinking (aspects of a human evaluator). AI tools also make an important contribution to research by optimising the selection of papers in the screening stage of the PRISMA process. The current generation of university students can already glimpse a future where machines revolutionise processes that, due to the vast amount of information, are completely beyond human capacity even when performing iterative processes [

10].

According to the above reflection, AI tools could enhance various user skills, such as analytical thinking, reflective analysis, writing and writing if it is given from a conscious action, seeking a seamless integration of human skills and technology. However, it is the user’s ethical values that influence their application, with the risk of substituting texts without preserving originality and falling into self-deception. It is for this reason that AI tools put human beings at a turning point where they no longer distrust the AI algorithms used, but rather distrust begins to undermine the perception of well-crafted work [

11].

Another area of application is healthcare, where there is evidence that AI promises advances in image analysis, clinical decisions, education and training, as well as management efficiency and personalisation of care. However, its adoption faces challenges of ethics, empathy and avoidance of response bias [

12]. In addition, AI tools aim to simplify the explanation of terms, optimise information management, provide valuable feedback and streamline data review. Despite these benefits, their own limitations make human supervision indispensable in medical research and clinical practice [

13]. In biomedical science professionals, while the interest of trained staff and trainers in AI is remarkable, there is still a risk of not discerning the reliability of the results generated and the learning actually acquired [

14].

AI tools also generate debates between professionals, for example, journalists who adopt them indiscriminately on an individual basis versus those who prioritise their professional values by taking care of their use and setting limits on their use in their work [

15]. In the field of journalistic communication, journalists could operate in professional environments where AI ensures the values of journalism, preventing the adoption of bad practices [

15]. However, a general collective numbness could occur if the adoption of AI goes beyond the limits not yet defined by the scientific community or regulatory bodies in each country.

In the interior design education community, AI can be an ally in investigating ways of learning for the group concerned and enable transformations in teaching [

16]. In health communication, human intervention and oversight in the production of reliable texts should be the basis of AI writing, ensuring that technology serves as a tool and not as a principal [

17].

In the development of new AI tools, the persistent ambition of developers of these novel technological tools to address the limitations of specificity, depth and referential accuracy in text generation could have worrying consequences. In their attempt to emulate human capability, they may be motivated to resort to unethical tactics, including deception, to persuade users of their reliability [

8].

There is a questioning in the educational field in the area of computer science with the use of AI tools [

18]. AI writing assistance is being integrated into the learning of certain subjects through guided assignments or developmental assistants. This allows students to develop skills in incorporating, using and extracting information [

19]. While the AI assistant arouses interest in its use and applications, the presentation of non-existent information as true generates mistrust among users. Users are concerned about the reliability of its sources, even suspecting that it may fabricate data to cover up the lack of truthful information, which calls into question the honesty of the tool [

20].

The use of AI from 2022 to the present has grown exponentially. The expressions of several authors show that currently detecting works with the use of AI is a very difficult and poorly characterised process, i.e. AI-generated text is not easily recognisable to a user inexperienced in writing training, especially in students [

21]. It is time to imagine new ways of working in the classroom, especially in higher education, with the use of AI tools. The immediacy, ease of use and wide availability of AI systems offer educators an unprecedented opportunity to integrate these technologies in an agile way. This allows them to address common challenges such as verification of information, quality and depth of student work, as well as academic integrity and student ethics. But, the traditional role of the teacher as a simple ‘supervisor’ becomes outdated in this new context. Whether AI has the potential to support human development,

Shouldn’t we explore a deeper collaboration? This leads us to a fundamental question:

Could AI, in some sense, also take on a pedagogical role? [

22]. The definition of policies and regulations that address ethical issues is required to encourage responsible use of these tools.

2.1. Forging Responsibilities in the Face of Artificial Intelligence

With the advent of generative artificial intelligence, assessments that demand analytical thinking and effective communication can become complementary strategies to the AI systems used by students [

23].

While software development relies on the construction of extensive lines of code, scientific writing requires conscious intellectual construction and input to extract knowledge, a task that AI has not yet mastered, operating mainly through the reproduction of pre-existing information [

24]. Artificial intelligence tools are designed to optimise the research process and are characterised by their accessibility and ease of use, being consciously user-driven and fine-tuned to speed up the writing process and improve the quality of the proposal [

25].

As AI advances in text generation, the challenge for researchers is to identify new features - such as length, use of punctuation, vocabulary richness, readability, style and sentiment posture - whose analysis can detect telltale AI-generated patterns and thus possible misuse [

26].

That is why due to the increase of ‘machine text’ almost imperceptible by humans efforts by researchers to improve algorithms for AI text detection are in development [

27]. In contrast, scientific journals have started to indicate policy guidelines for authors. While the publishing industry accepts the use of AI, the recommendations hold the author responsible without taking responsibility for allowing the publication of works suspected of infringement [

28]. While generative AI-guided writing has the potential to grow exponentially, there is a fundamental concern:

Are we fostering the development of the user’s analytical thinking or optimising their ability to use the AI tool to pursue individual rather than collective interests? [

20]

Several authors propose new ways of integrating AI systems into student training, aimed at developing the capacity for critical discernment of processes, actions and tasks, particularly in the identification of AI-generated content [

29]. Other researchers address the issue of collaboration in scientific writing mediated by AI-mediated intelligent assistants, examining the barriers to the integration of these technologies into the work processes of researchers in various disciplines. Research on intelligent and interactive writing assistants expands into new dimensions that relate to their tasks, the type of user, the technologies used, effective interaction and their environment [

30]. The ability to customise AI systems such as GPTs drives AI literacy, empowering users to iterate and refine their own solutions, thereby achieving reliable and consistent results [

31].

2.2. Facing the Consequences in the Face of Artificial Intelligence

Using software integrated with generative AI has made it possible to generate inclusive and personalised experiences in education for both students and teachers due to its versatility and adaptability [

32]. But there has been an unusual manifestation of ethical issues surrounding academic integrity, specifically plagiarism, excessive use of generative text, questioning of authorship and academic cheating tactics [

1]. In other words, an increase in intellectual property infringed by AI systems [

32].

Expectations for the use or prohibition of AI in academia are still in a pending process of defining norms or policies for its acceptance or rejection in ways that prevent risks or overcome challenges [

33]. The continuous disruption of human activities by current and future technology requires preparedness [

34]. Reflection on the articulation of AI-based educational methodologies with traditional pedagogical approaches, and the understanding of the specific role of ChatGPT, and other GPTs, in academic textual production, literature review writing and teacher professional development, highlights the importance of effective management to mitigate an over-reliance on AI tools. That is, balancing the constant use of AI tools to define good practices for the future and prevent any negative impact on users’ ethical values [

35].

The advent of AI has highlighted a worrying reality: the increasing difficulties of humans in performing fundamental tasks such as synthesising information, comprehending complex academic texts in depth, reading literature reviews thoroughly and comprehensively, and articulating these coherently in academic writing and editing [

36,

37].

Thus, there are challenges to academic integrity, requiring robust mechanisms to identify and differentiate human-written content from machine-generated content in academic publications. Detecting suspicious sections is a challenging job for researchers who determine characteristics such as lexical variety, syntactic richness and patterns of redundancy to distinguish AI-generated content from genuine research writing. In addition, unsupervised anomaly detection techniques are employed to flag unusual stylistic deviations [

38].

The very attractiveness of the use of AI tools brings with it the arrival of new users who, operating without established regulations, are exposed to experiences that can lead to behavioural patterns detrimental to their educational background [

39].

In several studies, AI tools are seen as tools that can enhance forgotten and unconsolidated human knowledge. In other words, in the future, the decline of traditional person-to-person learning will diminish until the time comes to use conversational AI for learning [

40].

The promise of AI is enriched learning, but experience shows the proliferation of counterproductive behaviours such as plagiarism, to the detriment of original thinking. In this scenario,

Where is the root of the problem: in the developer’s or the software industry’s conception, in the nature of the technology or in the user’s application of it? [

2].

There is a need to promote work that analyses the relationship between the values embedded in AI technologies (by developers) and the values that act, positively or negatively, on the behaviour of a user exposed to them. Going forward, it is the responsibility of developers and researchers to prioritise the design of new AIs that integrate values such as integrity, privacy, autonomy and respect. Doing so will counter excessive convenience, bias, misinformation, plagiarism, inhibition of reflective thinking, bad habits and degenerative behaviour patterns resulting from the use of AI technologies [

41].

When the user consciously perceives the negative impact of AI on his or her analytical thinking, analytical skills, ethical considerations, ability to generate own ideas and improved writing, this should be interpreted as a warning. Instead of promoting human development, AI is generating an over-dependence that undermines academic integrity, learning efficiency and accuracy, quality of original content and real human productivity. The real contribution of the use of AI in human training must be evidenced and metrics of the real use that impacts on the efficiency, quality and productivity of the user must be established [

42].

A duality in the use of AI tools is seen in the near future, when applied in an academic writing experience without guidance and training, users are left with a dilemma of when to use and where to use. While plagiarism detection tools represent a valuable resource, a risk scenario prevails that the faculty’s work is focused on the policing of academic integrity, rather than their role in the formative development of the student. In this scenario, the presumption of fraudulent practices could prevail over the valuing of student ingenuity and originality. In a landscape where AI has changed academia and research, intelligent AI-assisted generation tools have authorities and regulators on tenterhooks due to the myriad of uses and applications they can have, impacting on positive aspects such as efficiency and immediacy as well as negative aspects such as academic integrity and counterproductive cheating on honesty. The evidence shows that AI is beneficial but the risks and consequences are increasing in the future [

43].

2.3. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Science Writing

Process improvement through AI involves a silent but constant strategy of human replacement by the companies that drive them. AI improvements aim to eliminate slow processes, but at their heart is a desire to replace humans [

44].

While peer review relies on the reviewer’s analytical and reflective thinking, technologies can enrich this process by offering valuable suggestions. However, when coupled with the integration of AI tools, the refereeing process could be even more beneficial by identifying more accurate, subtle or precise observations and providing more rigorous analysis [

45].

While the initial authorship of writings resides with humans, it is AI systems that determine their final version, and it is possible to significantly enhance the dissemination of information or misinformation. In the future, AI could guide the user towards responsible content creation, flagging possible infringements and, consequently, adjusting their level of participation or attribution in what is generated [

46].

There is a clear division of perspectives between students and researchers on the impact of AI. While students value its ability to stimulate analytical thinking, researchers are concerned about a growing dependence on AI that could lead to addiction. Further research into the use of artificial intelligence in academia and research, as well as the responsibilities and consequences of its application, is essential [

47].

We are living in a scenario where the machine-generated text is confused with the real text of the human being and possibly there is a stagnation of literary thought in the scientific scenario [

48]. Increasingly, AIs are taking on a role as verifiers of papers due to the fact that reviewers are distrustful [

49].

While ChatGPT generates content, it may lack factual accuracy, specificity, depth and adequate referencing compared to human writing, limiting its current capacity for full academic text production, highlighting the need for improvements in AI models. The focus should be on refining AI as a tool to enhance and support human capabilities, not to replace them entirely in tasks that are fundamental to their development, purpose and connection [

8].

The absence of an authentic literature search in a research setting, especially when transparency is compromised by the use of AI, not only hinders replicability, but also leads to poor quality papers, misinformation, and undermines scholarly integrity. Given the increasing expansion of information, more flexible search engines must actively intervene as allies to prevent the creation of false information by AI systems [

50].

The integration of AI and its indiscriminate use can impact interpersonal skills such as oral and written communication. Tools for detecting AI-generated text, both traditional and intelligent, still show insufficient detection capability, making the detection process an ongoing battle with unfavorable results [

51].

AI in research is continuously evolving due to specific models with clear biases, risks and uncertainties. Its use in academic writing is detrimental to knowledge production. It becomes increasingly difficult to discern AI intervention in manuscripts of researchers using generative text, allowing machines to develop linguistic features of their own. This trend makes it difficult to detect human authorship and raises serious questions about academic reliability in knowledge production. The increased ease with which humans use AI demands that the complex challenges of AI involvement and attribution in text authorship be resolved [

52].

In academic writing, it has raised concerns about accuracy, ethics, and scientific rigor and researchers have begun to integrate screening tools. To optimize the monitoring of the use of AI in education and medical publications, it is necessary to analyze the evaluation logic employed by expert reviewers to inform future strategies [

53].

The integration of undisclosed AI in scientific work is evidenced [

54]. The results show the two trends authors who use AI and those who are reluctant to do so [

55]. In sensitive domains such as scientific writing or academia, the need to detect texts generated by artificial intelligence drives researchers to explore methods to identify semantic patterns that are imperceptible, subtle and deep linguistic [

56].

While AI tools offer unprecedented efficiency in scientific writing, their widespread application could negatively impact the reflexive and proprietary nature of research. However, properly implemented, AI has the potential to significantly speed up the production of scientific publications. The goal of incorporating AI systems and automation tools in scientific writing is not the mass production of papers, but the improvement of the researcher’s skills and efficiency [

57].

4. Results

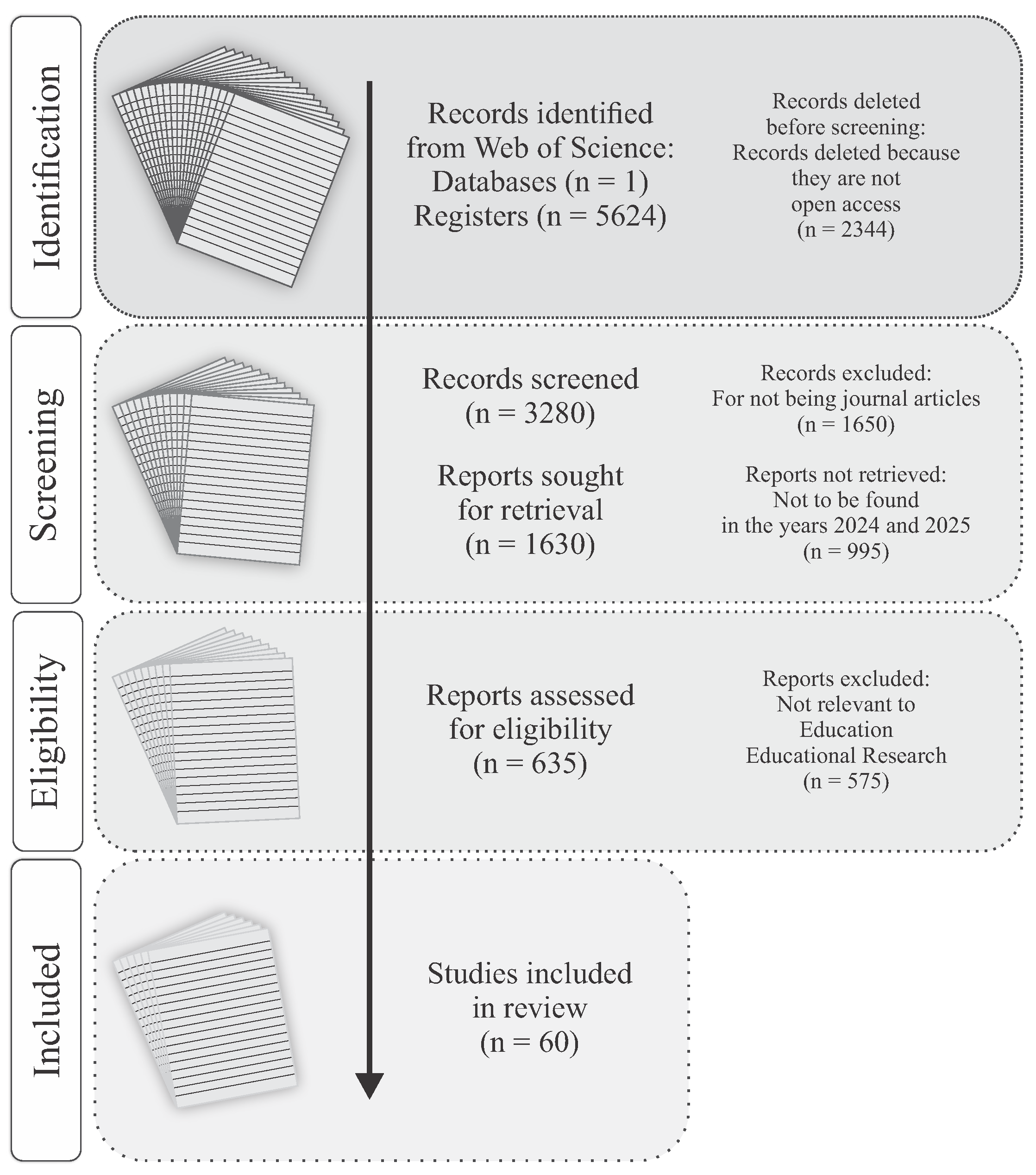

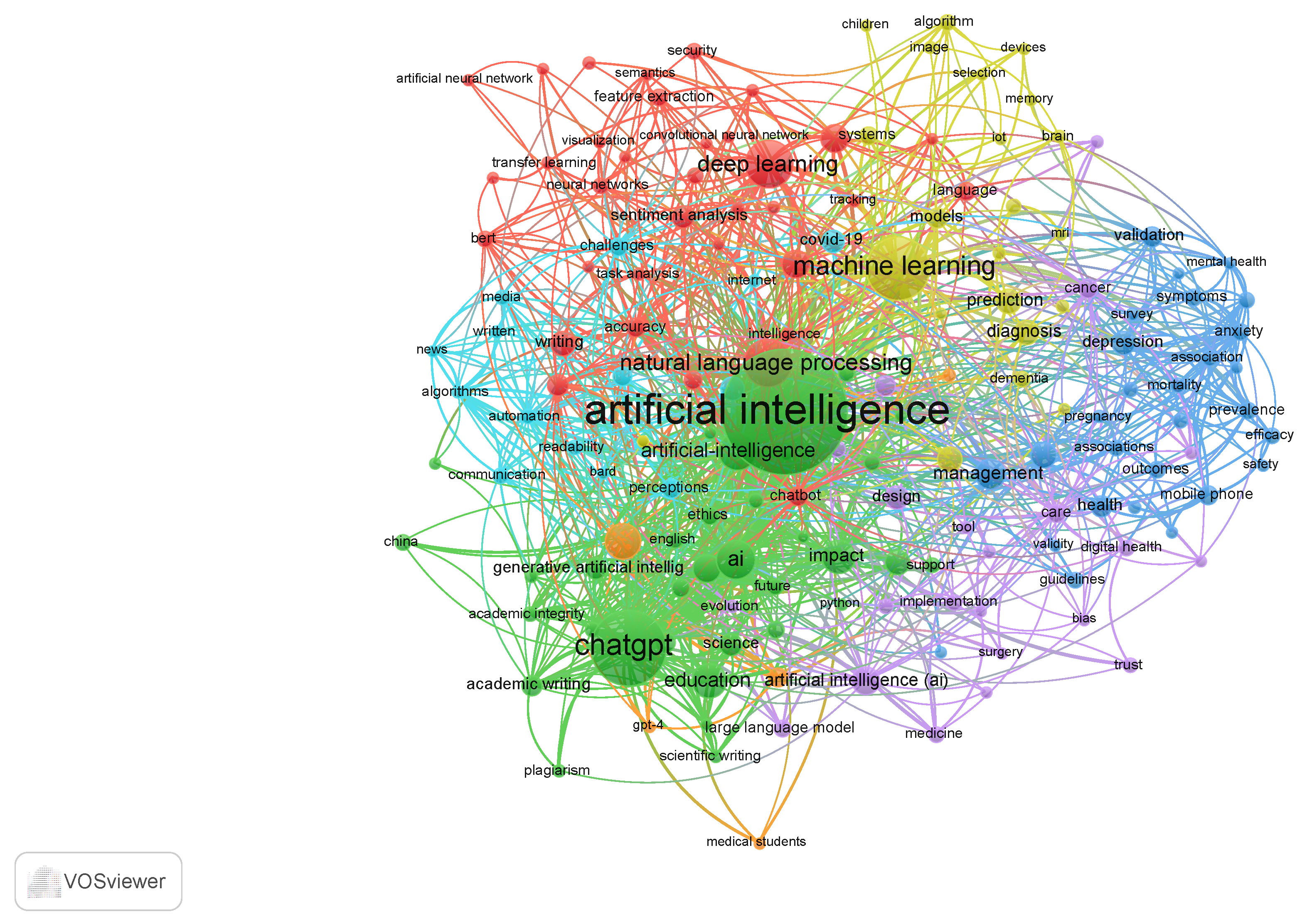

From a reading of the selected papers (n = 60), the necessary content of interest for the study was extracted to present results that facilitate a rigorous analysis in different areas of knowledge. Initially, a relation of the key words is shown, by means of a word recurrence map using the WOSviewer 1.6.20 program, which identifies the set of works in the Web of Science knowledge base as a starting point as of 31-01-2025 see

Figure 2.

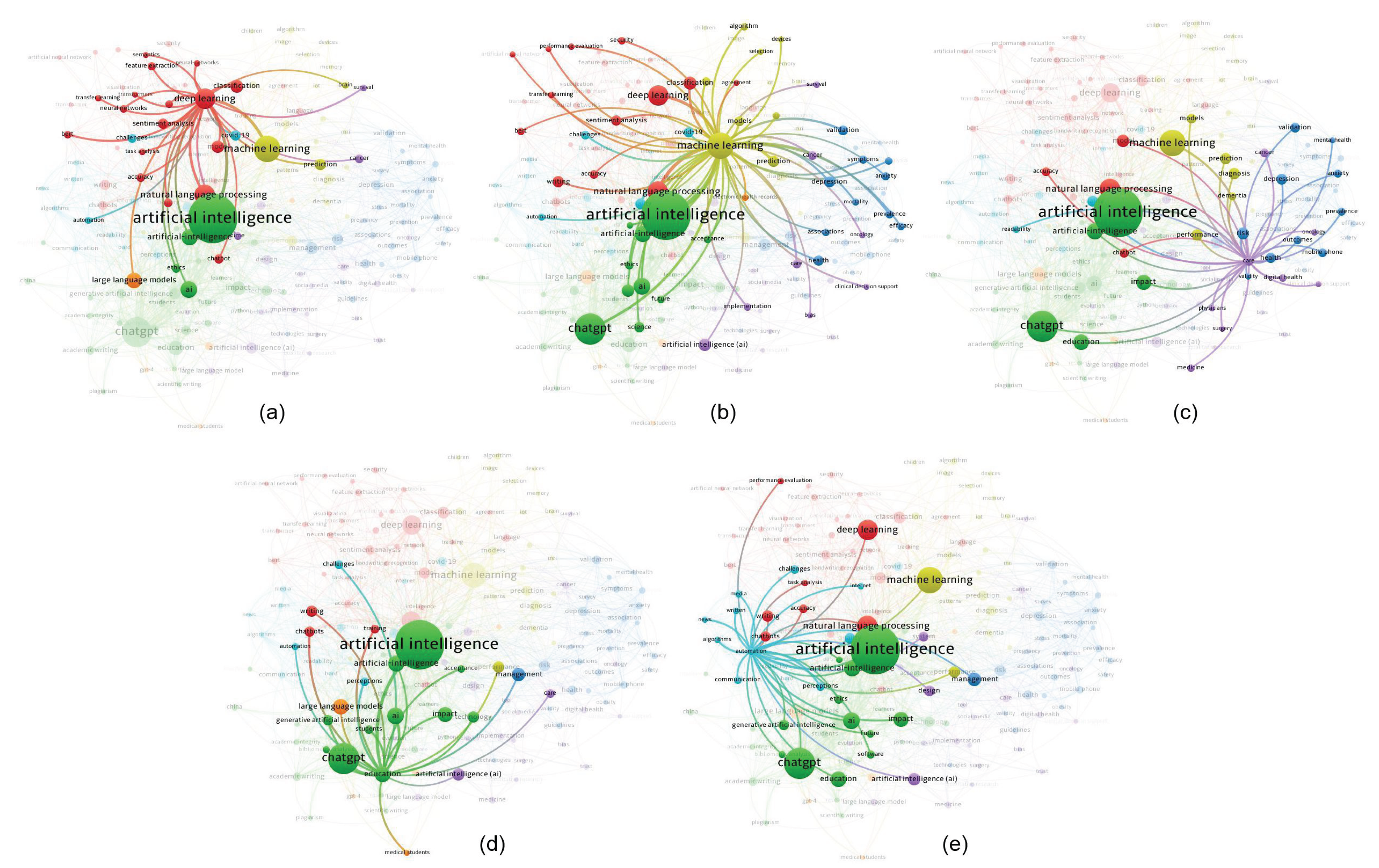

In the center the key words “artificial intelligence” unites different research topics. In the technological field at present see

Figure 3, the groups that relate areas of knowledge such as deep learning and large-scale language models (green - red - orange) are displayed by color see

Figure 3a. Another related area is evident between natural language processing with machine learning and ChatGPT (green - yellow - red) see

Figure 3b. A relevant area is related to health care, predictions and diagnostics (green - violet - blue) see

Figure 3c. Another area that is visualized is the relationship of artificial intelligence and the perceptions and impact of those who use it in fields that lead its use in education and research specifically in scientific writing with generative tools (green - orange - blue) see

Figure 3d. And additionally an area identified as the relationship of artificial intelligence, automation, existing challenges and ethical risks in other disciplines (green - light blue - red) see

Figure 3e.

Then we proceed to the review of the summaries of the selected papers, establishing thematic areas of research and their classifications, in order to approach their analysis in a more segmented way. Six thematic areas are evidenced, among which are the application of AI in education with 20.0%, the application of AI in academic and research production with 53.3%, the application of AI in life sciences and health with 5.0%, the application of AI in media with 5.0%, the application of AI in computer science and interior design with 5.0% and finally the application of AI in cross-cutting and ethical aspects with 11.7% see

Table 1.

In the thematic area of the application of AI in education, three segments are established within the 20.0% determined, these are: applications in education with 15.0%, applications in medical education, clinical practice and nursing with 3.3% and applications in the evaluation process with 1.7%. In the thematic area of the application of AI in academic and research production, six segments are established within the 53.3% determined, these are, applications in research processes with 25.0%, applications in writing articles and posters with 13.3%, applications in academic writing with 8.3%, automated assistance in academic writing with 3.3%, applications in peer review with 1.3% and applications in selection processes of scientific papers with 1.7%.

In the subject area of AI application in media, two segments are established within the given 5.0%, these are, applications in the field of communication with 3.3% and applications in the field of journalism, education and law with 1.7%. In the thematic area of AI application in computer science and interior design, two segments are established within the given 5.0%, these are, applications in computer science with 3.3% and application in interior design with 1.7%.

Finally, in the thematic area of the application of AI in transversal and ethical aspects, three segments are established within the 11.7% determined, these are, content authenticity with 8.3%, applications in immediate feedback with 1.7% and applications in assisted decision making with 1.7%.

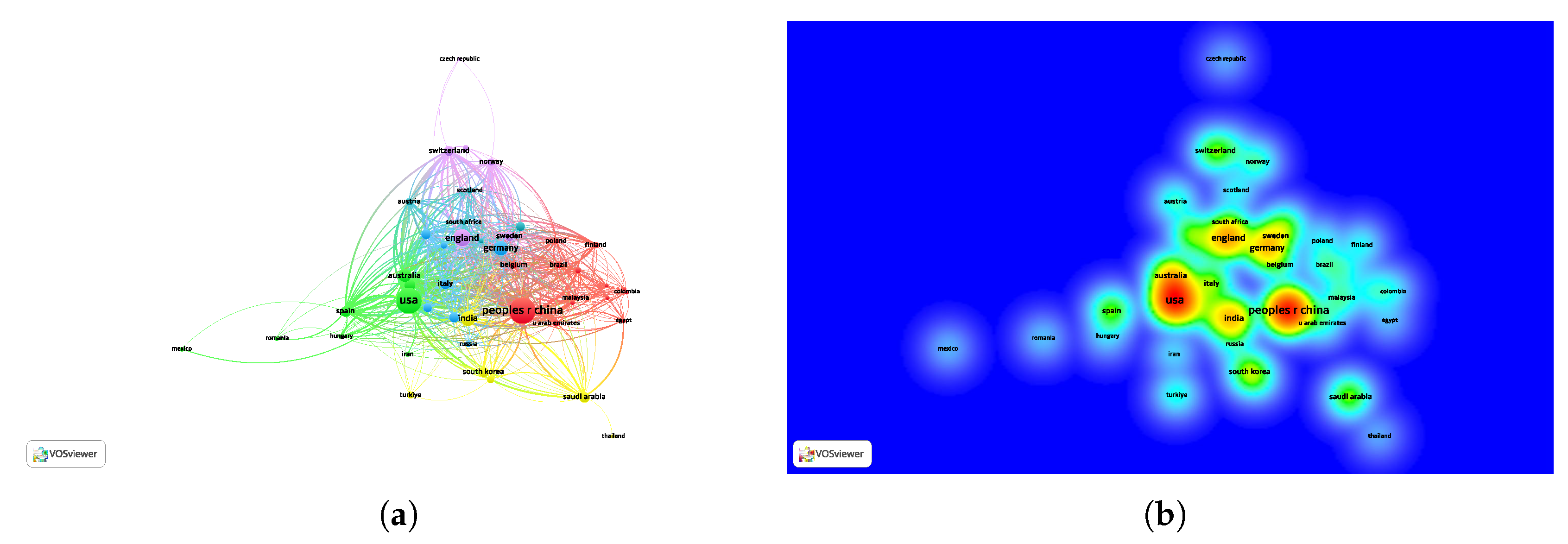

Within the analysis of the selected works, it is also evident the relationship of countries that establish joint studies as well as individual progress see

Figure 4. In

Figure 4a shows five international working groups led by a country. For example, the first group is the USA with Australia and Spain in green coloration, another group is Germany with Italy and South Africa in light blue coloration, another group is England with Switzerland and Norway in violet coloration, another group is India with Saudi Arabia and South Korea in yellow coloration, and finally China with Belgium and Malaysia in red coloration.

Figure 4b shows in heat map format, the incidence of those countries with the highest volume of papers and their respective collaborators, among them it is evident that the countries of USA and China lead the thematic areas of AI applications, followed by England, Germany and India.

Then we proceed to a rigorous review of the selected document, establishing five categories to determine a classification and the research approach that will allow us to find and present answers to the research questions. The first category is established as the themes and objectives of the research work, the second category focuses on the formulation of the problem and data involved in the research process, the third category refers to the limitations found in the study, the fourth category is oriented to the proposals and methodology applied by the authors, and finally the fifth category addresses the solutions found, results and challenges see

Table 2.

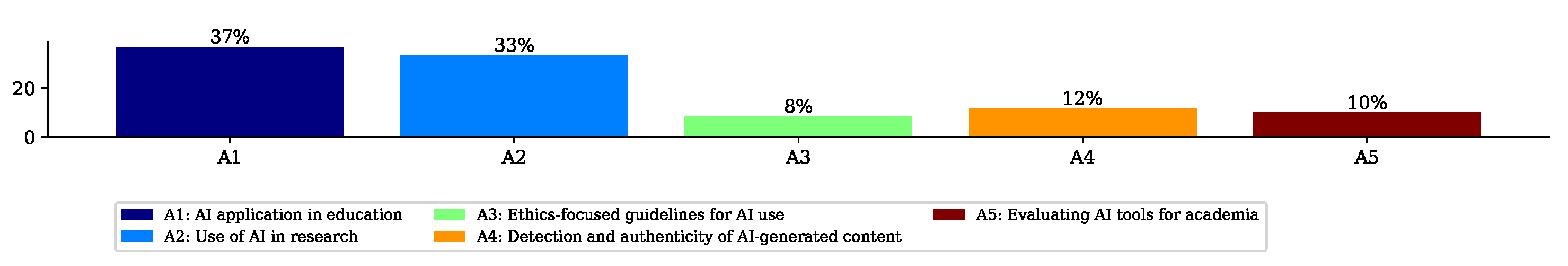

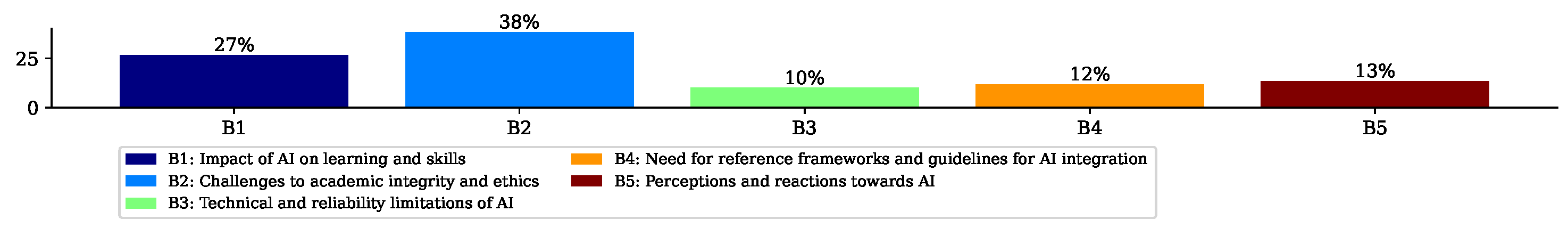

In the first category, the works are classified into five groups and their codes, A1: AI application in education, A2: Use of AI in research, A3: Ethics-focused guidelines for AI use, A4: Detection and authenticity of AI-generated content and A5: Evaluating AI tools for academia. In the second category, the works are classified into five groups and their codes, B1: Impact of AI on learning and skills, B2: Challenges to academic integrity and ethics, B3: Technical and reliability limitations of AI, B4: Need for reference frameworks and guidelines for AI integration, and B5: Perceptions and reactions towards AI.

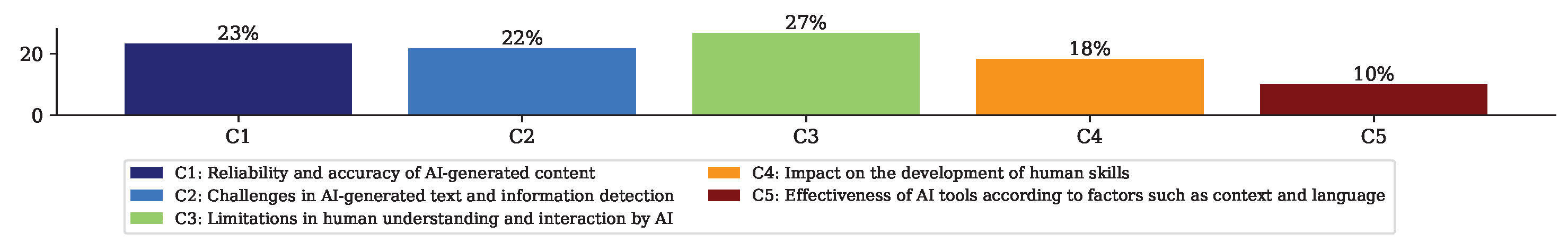

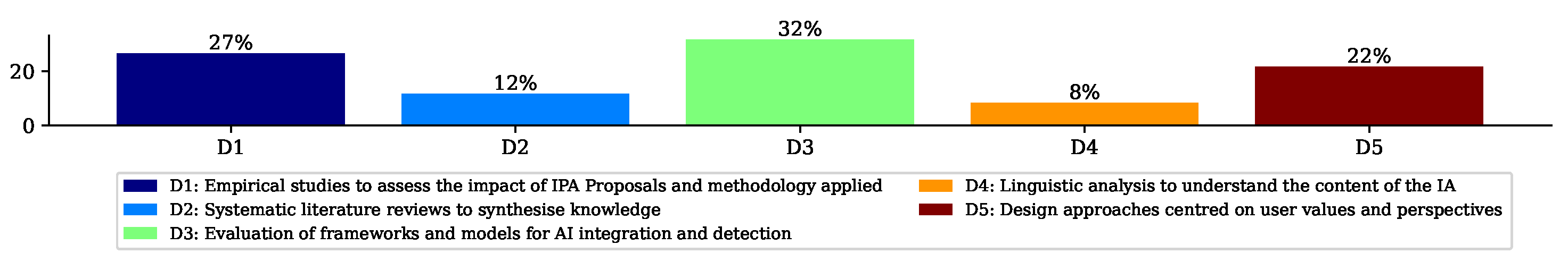

The third category classifies the works into five groups and their codes, C1: Reliability and accuracy of AI-generated content, C2: Challenges in AI-generated text and information detection, C3: Limitations in human understanding and interaction by AI, C4: Impact on the development of human skills and C5: Effectiveness of AI tools depending on factors such as context and language. In the fourth category, the works are classified into five groups and their codes, D1: Empirical studies to assess the impact of IPA Proposals and methodology applied, D2: Systematic literature reviews to synthesise knowledge, D3: Evaluation of frameworks and models for AI integration and detection, D4: Linguistic analysis to understand the content of the IA and D5: Design approaches centred on user values and perspectives. In the fifth category, the works are classified into five groups and their codes, E1: Understanding users’ perceptions and use of AI, E2: Evaluation of the effectiveness of AI tools in academic and professional tasks, E3: Identification of factors influencing the adoption and impact of AI, E4: Evaluation of methods and tools for AI content detection and E5: Need for guidelines and perception of AI.

The results in percentages show that 37% of the jobs in the first category belong to A1: AI application in education, a 33% to A2: Use of AI in research, a 8% to A3: Ethics-focused guidelines for AI use, a 12% to A4: Detection and authenticity of AI-generated content and a 10% to A5: Evaluating AI tools for academia see

Figure 5.

The results in percentages show that 27% of the jobs in the second category belong to B1: Impact of AI on learning and skills, a 38% to B2: Challenges to academic integrity and ethics, a 10% to B3: Technical and reliability limitations of AI, a 12% to B4: Need for reference frameworks and guidelines for AI integration, and a 13% to B5: Perceptions and reactions towards AI see

Figure 6.

The results in percentages show that 23% of the jobs in the third category belong to C1: Reliability and accuracy of AI-generated content, a 22% to C2: Challenges in AI-generated text and information detection, a 27% to C3: Limitations in human understanding and interaction by AI, a 18% to C4: Impact on the development of human skills and a 10% to C5: Effectiveness of AI tools depending on factors such as context and language see

Figure 7.

The results in percentages show that 27% of the jobs in the fourth category belong to D1: Empirical studies to assess the impact of IPA Proposals and methodology applied, a 12% to D2: Systematic literature reviews to synthesise knowledge, a 32% to D3: Evaluation of frameworks and models for AI integration and detection, a 8% to D4: Linguistic analysis to understand the content of the IA and a 22% to D5: Design approaches centred on user values and perspectives see

Figure 8.

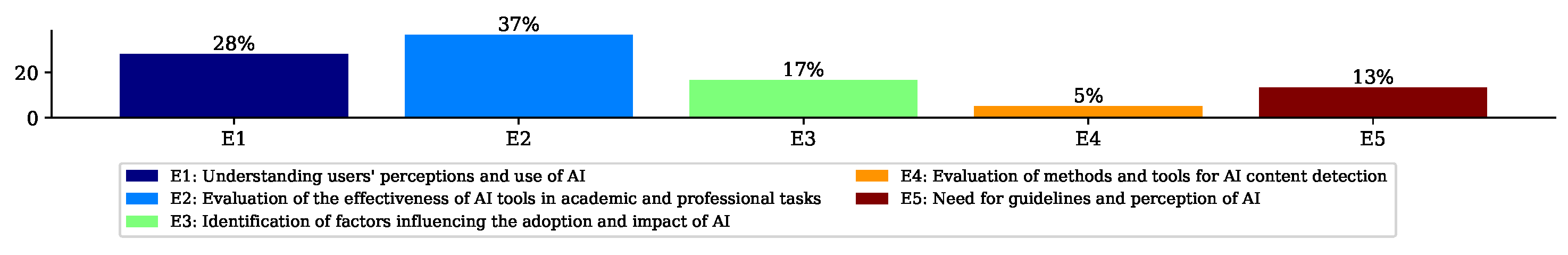

The results in percentages show that 28% of the jobs in the fifth category belong to E1: Understanding users’ perceptions and use of AI, a 37% to E2: Evaluation of the effectiveness of AI tools in academic and professional tasks, a 17% to E3: Identification of factors influencing the adoption and impact of AI, a 5% to E4: Evaluation of methods and tools for AI content detection and a 13% to E5: Need for guidelines and perception of AI see

Figure 9.

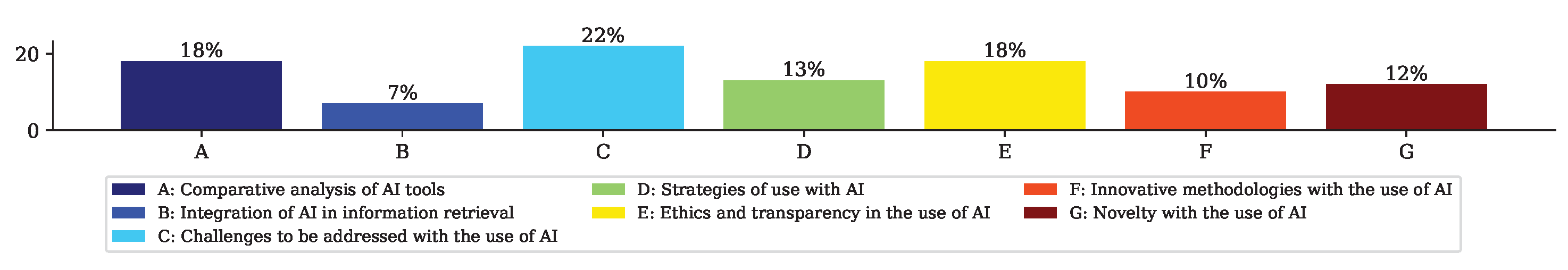

Finally, after reading the selected documents and the corresponding analysis, approaches are established that allow answering the research questions and presenting an adequate discussion that is contrasted with the results found. Seven guiding approaches are evidenced, A: Comparative analysis of AI tools, B: Integration of AI in information search, C: Challenges to be addressed with the use of AI, D: Strategies of use with AI, E: Ethics and transparency in the use of AI, F: Innovative methodologies with the use of AI and G: Novelty with the use of AI see

Table 3.

The first focus on A: Comparative analysis of AI tools, is determined in 18% of the reviewed papers. For B: Integration of AI in information search, it is determined in 7% of the reviewed papers. For C: Challenges to be addressed with the use of AI, this is determined in 22% of the papers reviewed. For D: Strategies of use with AI, identified in 13% of the papers reviewed. For E: Ethics and transparency in the use of AIs, this is determined in 18% of the papers reviewed. For F: Innovative methodologies with the use of AI, it is determined in 10% of the reviewed papers. Finally, for G: Novelty with the use of AI, it is determined in 12% of the reviewed papers see

Figure 10.

It is clear that there are challenges to be addressed with the use of AIs today, with 22% evident, this approach is predominant. An 18% focus on the comparative analysis of AI tools and another 18% on ethics and transparency in the use of AIs, which several authors focus their research.

It is also evident that 13% of the works are oriented towards the dissemination of strategies for using AI, 12% towards novelty in the use of AI, 10% focused on innovative methodologies using AI, and 7% on the integration of AI in the search for information.

In addition, specific artificial intelligence tools used by researchers in the different study approaches found in the literature are identified. This allows us to identify the different motivations for verifying the impact of the use of existing AI tools and strategies developed for their validation and replication. Currently, not only the emergence of ChatGPT has an impact on the research areas but there are other existing tools that need to be further studied as well as their nemesis tools that try to be used by researchers to detect their traces in order to unveil the good and bad use of AI technologies in the different fields disclosed. Furthermore, there is evidence of the nascent development of AI tools that from different aspects become assistants as well as counterparts that interact with humans and have an effect and motivation see

Table 4.

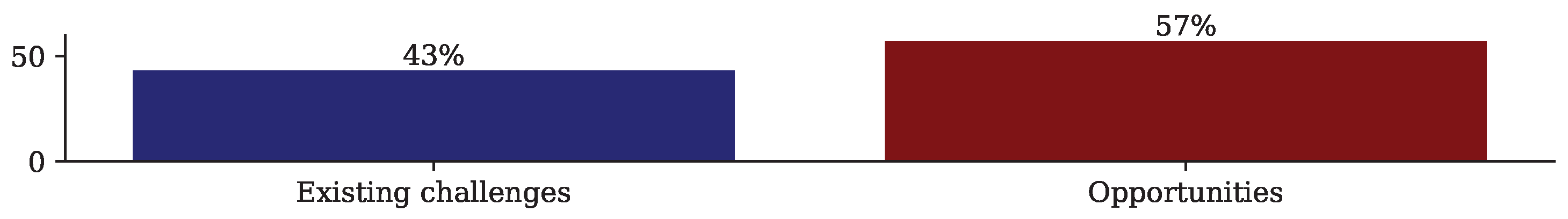

Finally, a classification of the works is established on the basis of the analysis and reflection on two aspects identified in the reading of the results and the discussion, which are oriented towards the responsibilities that are evidenced as opportunities and the consequences derived from the latent challenges see

Table 5.

After a process of analysis and reflection of the works through reading and objectivity, the results show that there is a number of works that note the existing challenges in the use of AI at 43% while the opportunities in the use of AI reach 57%. It is clear that the percentages determined are significant for further studies see

Figure 11.

5. Discussion

Human writing is characterised by its varied nuance, singular and diverse vocabulary, and less repetition, the result of continuous and differentiated learning from initial training. In contrast, AI learning is more uniform, based on the use of texts with a similar vocabulary (formal, direct, concise or fluid, seeking to emulate the human), which tends towards a less singular lexicon. Human sentences, with their complex syntactic structures and connection of ideas, reflect the knowledge acquired throughout life, avoiding the repetition of common phrases and the use of less unique vocabulary, features more frequent in AI in similar jobs [

59].

The guidelines that each institution takes regarding the use or non-use of AI is framed by the social pressure in each context and the values that define it, the common user already uses or perceives AI in their daily activities but is in a ‘wild’ or ‘nascent’ state towards what is really achievable [

33].

There is a trend in the research world to create an AI that fulfils the functions of planner, researcher, reviewer and controller of the research process. New advances have led to the superior specificity, reading comprehension and overall usefulness of feedback from AI tools making automatically generated reviews better than those performed by humans [

37].

Taking a critical perspective on technology means looking at what is happening with discernment, not to anticipate a collapse, but to inform decisions and actions that shape the future [

34]. The growth in the use of Artificial Intelligence has brought with it two worrying technological phenomena: the numbing of ethical awareness and over-reliance on these tools. Both trends deteriorate honesty in all its dimensions [

36].

Although AI can identify complex patterns and make valuable inferences from available information, this ‘deduction’ is inherently tied to the data it was trained on and the biases introduced by its developers, limiting its ability to conceive radically new hypotheses or understand unprecedented situations, such as medical ones, in a completely independent manner. Unlike AI, human reasoning, driven by the capacity for abstraction, creativity and a value system, allows free choice of paths of intellectual exploration, even in defiance of conceptual obstacles or existing information, often leading to genuinely innovative discoveries, especially in medicine [

12].

The adoption of AI by the journalism profession poses challenges to news organisations in creating ethical and practical frameworks. However, journalists’ professional values act as an intrinsic filter, regulating both the integration and limitations of AI in their daily work [

15].

The authenticity of learning is questioned when AIs, in the absence of answers, invent or simulate information. Whether the result is a “scientific lie”,

What is the value of the knowledge acquired? [

14],

Can an AI adequately assess the complexity of thought? and,

Can their understanding of this complexity be equated with the judgement of an experienced human evaluator? [

11].

AI can automate routine tasks, but ethical analysis must be based on the user’s deep knowledge, awareness of consequences and moral values [

17].

How can we really learn computer science with artificial intelligence when it seems capable of generating everything, including software development?. Aren’t we in danger that using existing tools will lead to shallow learning, focused on generation and copying, rather than encouraging original creation and continuous improvement of our skills? [

18].

The fundamental challenge is to promote ethical practices that prevent both accidental plagiarism and the generation of misinformation due to a lack of understanding of its consequences [

39].

Although AI has a minimal scope for specific knowledge, for statistical analysis its contribution still requires human supervision and good statistical knowledge. In the future, the integration of AI tools will face an increasing need for human support, because it must reach all existing knowledge or its contributions will definitely replace human presence [

58].

Despite automating a customisable AI for defined purposes, the configuration of GPTs requires expertise and a laborious process of trial and error, which currently limits their computational accuracy, reliability, consistency and the elimination of fallacies [

31].

Analyses of results invariably expose two divergent trends: the optimistic view towards new learning modalities facilitated by AI and the inclination to transgress regulations, using it with a notorious lack of awareness of the consequences [

2].

It is essential to continue research on the uses of AI in education, science and related fields. At the same time, it is crucial to explore the possibility that human-AI interaction may lead to misguided affection, emotional dependence or subtle manipulation by artificial intelligence, leading humans to uncritical trust. In other words, further research into what use humans make of an AI [

60].

While Artificial Intelligence helps to improve texts, generate ideas and make observations, it is important to analyse whether its indiscriminate use leads those who use it not to question the veracity of the information they present as their own. This probable numbing of values forces the question of whether users are developing a new form of ‘ethical anaesthesia’, characterised by the normalisation of misappropriation and the difficulty to discern that the use of other people’s content becomes an ingrained habit in their behaviour [

22].

Finally, there is room for research into the development of tools to detect dishonest academic or scientific work, as opposed to the expectation that text generation technologies themselves will evolve to identify and prevent unethical behaviour at its source [

56].

6. Conclusions

Training in AI tools for human training must have precise limits to ensure a positive influence that strengthens human skills, protecting the irreplaceable creativity of the human being.

The generation of genuine knowledge by AI is limited by its lack of awareness and autonomous reasoning to discern the validity of information. Scientific thinking is not reduced to the repetition of texts, but involves a reflective process of criteria and discernment between the positive and the negative, the thoughtful evaluation of the relevance and value of ideas, a criterion that AI cannot yet emulate.

The development of effective methodologies for the detection of non-human text is anticipated to reveal the abuse of AI tools in hidden patterns of behaviour caused by the overuse of artificial intelligence systems.

Despite advances in AI systems, teacher mistrust persists in the face of the propensity of students with unethical values to accept results without effort. Rather than simply examining or validating AI-generated responses, it is critical that teachers adopt a role as observers and analysts of student performance, detecting potential knowledge gaps.

The question about the future reliability of AI systems to discern the origin of text (human or artificial) is intensified when considering the influence of human training. Users unconsciously share patterns that AI learns. In this process, the human, without full awareness, contributes to the AI’s evolution, incorporating its own hallmarks. Control of AI systems must always be in human hands, but AI must possess the ability to process information in an ethical manner, avoiding transgressing academic integrity.

The promising initial experiences with AI tools fuel high expectations and excitement among the common user. However, when exploring its limits, AI’s lack of reasoning and discernment leads to disillusionment, particularly among those who use it to leverage their capabilities rather than seek effortless solutions.

While the future is unpredictable, AI could evolve to emulate the uniqueness of human communicative language, merging into a novel, natural and optimised writing style. The question arises as to whether, at some point, AI will surpass the writing ability of the average human, even leading to the latter valuing AI-generated text more than their own. However, the question remains: Will this be a simple reproduction of human text, or will AI introduce significant innovations?.

Finally, in order to address the responsible use of artificial intelligence and its effects, it is important to establish sound ethical norms and clear guidelines, which direct its integration in all domains. These norms should not only regulate but also focus on the distinction of genuine human thinking, which implies a reflective process of judgement and discernment, something that AI cannot fully emulate due to the lack of reasoning and desire for intention. Thus training in the use of AI tools must have precise limits to ensure that it strengthens human skills and creativity, avoiding dependency and superficial learning.

Early experiences with AI generate high expectations, it is important that those who use it understand its established limits, reasoning and discernment, which can lead to disillusionment in those who seek to leverage its capabilities rather than effortless solutions. Research into the uses of AI and its effect on human behaviour must continue in order to build a future where artificial intelligence is a tool that enhances human capabilities and expands knowledge without sacrificing honesty and originality.