Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

19 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

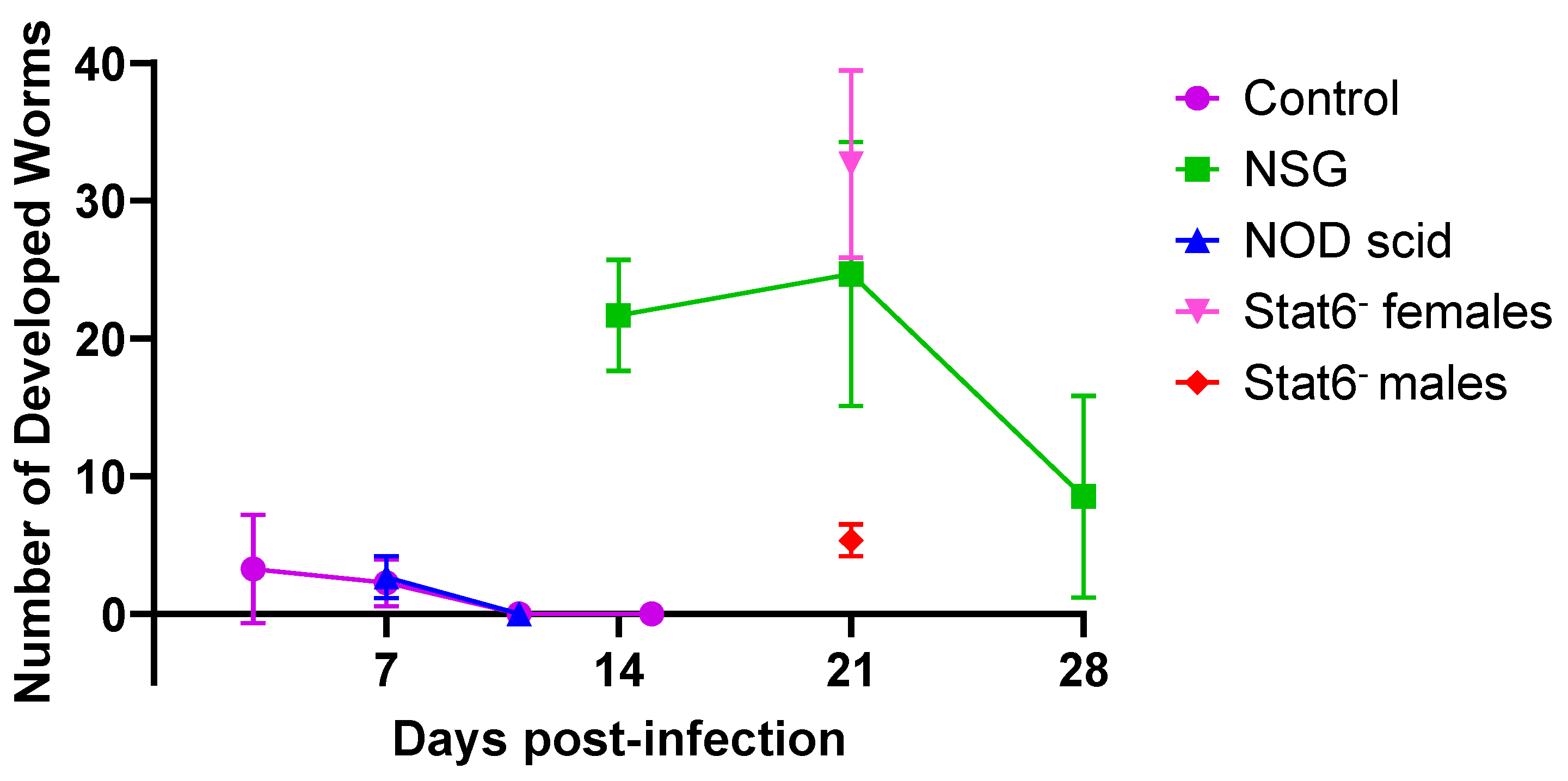

3.1. The Innate Immune System Is Responsible for Protection Against Hookworm Infection in Mice

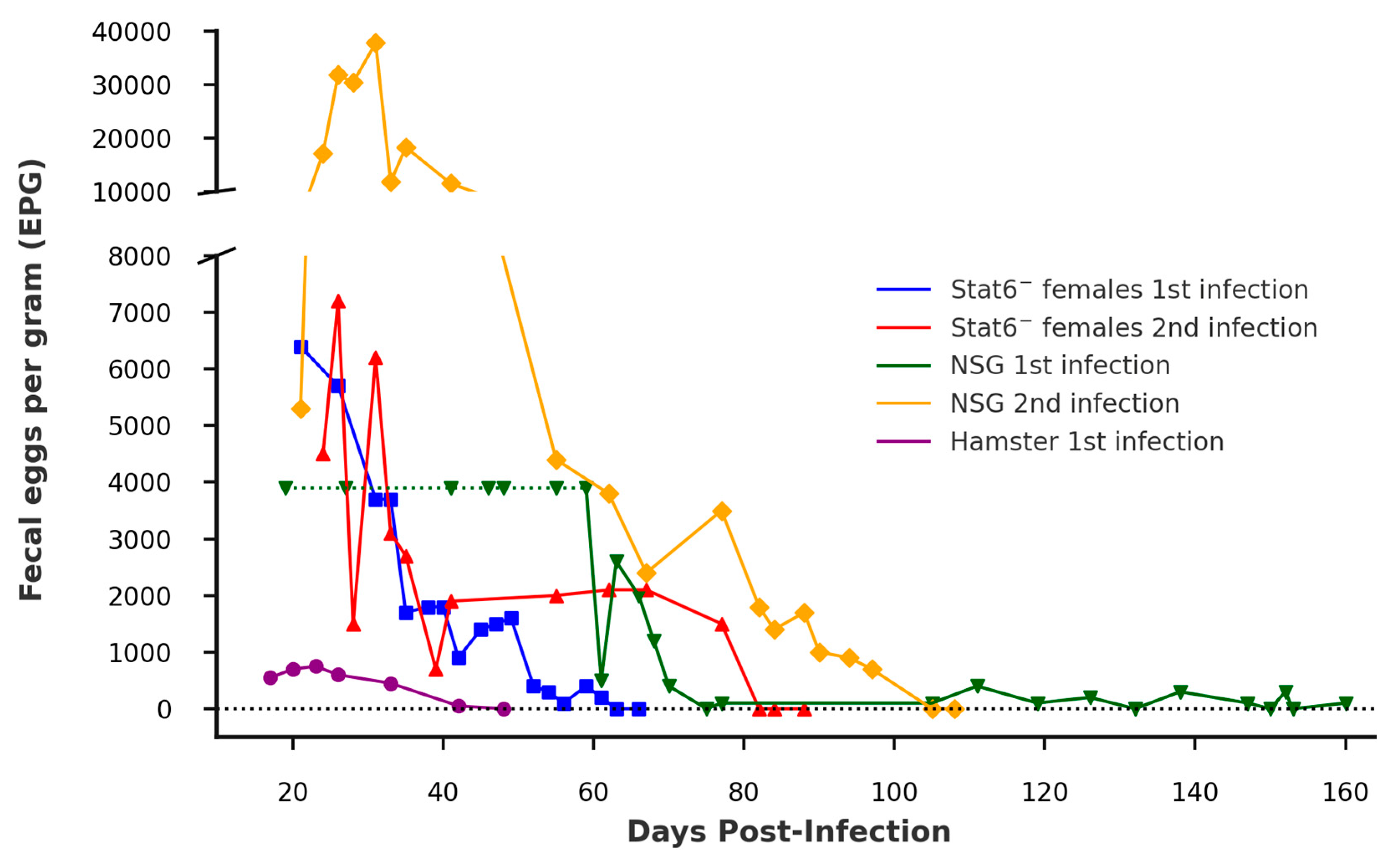

3.2. The Stat6 Pathway Is Responsible for Hookworm Protection in Female Mice

3.3. Infectivity of Stat6- Derived A. ceylanicum Larvae for a Permissive Host

3.4. Ancylostoma Caninum Fails to Develop in Immunodeficient Stat6- and NOD Scid Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STAT6 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 |

| STN | Soil transmitted nematodes |

| PI | Post-infection |

| NSG | NOD scid gamma |

| Esr | Estrogen receptor 1 |

| iL3 | Infective third-stage larvae |

| EPG | Eggs per gram |

| Black 6N | C57BL/6J |

| IL | Interleukin |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| MS | Muscoskeletal |

References

- R. L. Pullan, J. L. Smith, R. Jasrasaria, and S. J. Brooker, “Global numbers of infection and disease burden of soil transmitted helminth infections in 2010,” Parasit Vectors, vol. 7, p. 37, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. W. Gyorkos and N. L. Gilbert, “Blood Drain: Soil-Transmitted Helminths and Anemia in Pregnant Women,” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, vol. 8, no. 7, p. e2912, Jul. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Jourdan, P. H. L. Lamberton, A. Fenwick, and D. G. Addiss, “Soil-transmitted helminth infections,” Lancet, vol. 391, no. 10117, pp. 252–265, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Lozoff, E. Jimenez, and A. W. Wolf, “Long-term developmental outcome of infants with iron deficiency,” N Engl J Med, vol. 325, no. 10, pp. 687–694, Sep. 1991. [CrossRef]

- H. Sakti et al., “Evidence for an association between hookworm infection and cognitive function in Indonesian school children,” Trop Med Int Health, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 322–334, May 1999. [CrossRef]

- S. Brooker, P. J. Hotez, and D. A. P. Bundy, “Hookworm-Related Anaemia among Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review,” PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, vol. 2, no. 9, p. e291, Sep. 2008. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Manzoli, M. J. Saravia-Pietropaolo, S. I. Arce, A. Percara, L. R. Antoniazzi, and P. M. Beldomenico, “Specialist by preference, generalist by need: availability of quality hosts drives parasite choice in a natural multihost–parasite system,” International Journal for Parasitology, vol. 51, no. 7, pp. 527–534, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Ray, K. K. Bhopale, and V. B. Shrivastava, “Development of Ancylostoma ceylanicum Looss, 1911 (hamster strain) in the albino mouse, Mus musculus, with and without cortisone,” Parasitology, vol. 71, no. 2, pp. 193–197, Oct. 1975. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Bungiro Jr., B. R. Anderson, and M. Cappello, “Oral Transfer of Adult Ancylostoma ceylanicum Hookworms into Permissive and Nonpermissive Host Species,” Infect Immun, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1880–1886, Apr. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Langeland, E. L. McKean, D. M. O’Halloran, and J. M. Hawdon, “Immunity mediates host specificity in the human hookworm Ancylostoma ceylanicum,” Parasitology, vol. 151, no. 1, pp. 102–107, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Langeland, E. Grill, A. C. Shetty, D. M. O’Halloran, and J. M. Hawdon, “Comparative transcriptomics from intestinal cells of permissive and non-permissive hosts during Ancylostoma ceylanicum infection reveals unique signatures of protection and host specificity,” Parasitology, vol. 150, no. 6, pp. 511–523, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Shultz et al., “Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells,” J Immunol, vol. 174, no. 10, pp. 6477–6489, May 2005. [CrossRef]

- M. Bosma, W. Schuler, and G. Bosma, “The scid mouse mutant,” Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, vol. 137, pp. 197–202, 1988. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Kaplan, U. Schindler, S. T. Smiley, and M. J. Grusby, “Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells,” Immunity, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 313–319, Mar. 1996. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Hewitt, G. E. Kissling, K. E. Fieselman, F. L. Jayes, K. E. Gerrish, and K. S. Korach, “Biological and biochemical consequences of global deletion of exon 3 from the ER alpha gene,” FASEB J, vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 4660–4667, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Kitchen et al., “Isolation and characterization of a naturally occurring multidrug-resistant strain of the canine hookworm, Ancylostoma caninum,” Int J Parasitol, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 397–406, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Baermann, “A simple method for the detection of Ankylostomum (nematode) larvae in soil tests.,” A simple method for the detection of Ankylostomum (nematode) larvae in soil tests., pp. 41–47, 1917.

- H. M. Gordon and H. V. Whitlock, “A new technique for counting nematode eggs in sheep faeces,” Journal of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 50–52, 1939.

- S. C. Pan et al., “Cognitive and Microbiome Impacts of Experimental Ancylostoma ceylanicum Hookworm Infections in Hamsters,” Sci Rep, vol. 9, p. 7868, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Brooker, J. Bethony, and P. J. Hotez, “Human hookworm infection in the 21st century,” Adv Parasitol, vol. 58, pp. 197–288, 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Quinnell et al., “Genetic and household determinants of predisposition to human hookworm infection in a Brazilian community,” The Journal of infectious diseases, vol. 202, no. 6, p. 954, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wesołowska, “Sex—the most underappreciated variable in research: insights from helminth-infected hosts,” Veterinary Research, vol. 53, no. 1, p. 94, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Schad, “Hypobiosis and related phenomena in hookworm infection.,” Hookworm disease - current status and new directions., pp. 71–88, 1990.

- W. M. Stone and J. C. Peckham, “Infectivity of Ancylostoma caninum larvae from canine milk,” Am J Vet Res, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 1693–1694, Sep. 1970.

- Bereshchenko, S. Bruscoli, and C. Riccardi, “Glucocorticoids, Sex Hormones, and Immunity,” Front Immunol, vol. 9, p. 1332, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Stoye and J. Krause, “Reactivation of inhibited larvae of Ancylostoma caninum. Effect of estradiol and progesterone,” Zentralbl Veterinarmed B, vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 822–839, Dec. 1976.

- S. L. Schneider, S. O. Gollnick, C. Grande, J. E. Pazik, and T. B. Tomasi, “Differential regulation of TGF-beta 2 by hormones in rat uterus and mammary gland,” J Reprod Immunol, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 125–144, Dec. 1996. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Tissenbaum, J. Hawdon, M. Perregaux, P. Hotez, L. Guarente, and G. Ruvkun, “A common muscarinic pathway for diapause recovery in the distantly related nematode species Caenorhabditis elegans and Ancylostoma caninum,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 97, no. 1, pp. 460–465, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- P. Arasu, “In vitro reactivation of Ancylostoma caninum tissue-arrested third-stage larvae by transforming growth factor-beta,” J Parasitol, vol. 87, no. 4, pp. 733–738, Aug. 2001. [CrossRef]

- T. Bever, F. L. Hisaw, and J. T. Velardo, “Inhibitory action of desoxycorticosterone acetate, cortisone acetate, and testosterone on uterine growth induced by estradiol-17beta,” Endocrinology, vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 165–169, Aug. 1956. [CrossRef]

- Danisová, E. Seböková, and J. Kolena, “Effect of corticosteroids on estradiol and testosterone secretion by granulosa cells in culture,” Exp Clin Endocrinol, vol. 89, no. 2, pp. 165–173, Apr. 1987.

- T. Harding and N. S. Heaton, “The Impact of Estrogens and Their Receptors on Immunity and Inflammation during Infection,” Cancers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 4, p. 909, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao et al., “Sex Differences in IL-33-Induced STAT6-Dependent Type 2 Airway Inflammation,” Front Immunol, vol. 10, p. 859, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- J.-Y. Cephus et al., “Estrogen receptor-α signaling increases allergen-induced IL-33 release and airway inflammation,” Allergy, vol. 76, no. 1, pp. 255–268, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Salem, “Estrogen, a double-edged sword: modulation of TH1- and TH2-mediated inflammations by differential regulation of TH1/TH2 cytokine production,” Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 97–104, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- E. Maier, A. Duschl, and J. Horejs-Hoeck, “STAT6-dependent and -independent mechanisms in Th2 polarization,” European Journal of Immunology, vol. 42, no. 11, pp. 2827–2833, 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Urban et al., “IL-13, IL-4Ralpha, and Stat6 are required for the expulsion of the gastrointestinal nematode parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis,” Immunity, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 255–264, Feb. 1998. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Gazzinelli-Guimaraes, S. M. Jones, D. Voehringer, K. D. Mayer-Barber, and A. E. Samarasinghe, “Eosinophils as modulators of host defense during parasitic, fungal, bacterial, and viral infections,” Journal of Leukocyte Biology, vol. 116, no. 6, pp. 1301–1323, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. E. Norris, “The migratory behavior of the infective-stage larvae of Ancylostoma braziliense and Ancylostoma tubaeforme in rodent paratenic hosts,” J Parasitol, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 998–1009, Oct. 1971.

- P. Arasu and D. Kwak, “Developmental Arrest and Pregnancy-Induced Transmammary Transmission of Ancylostoma caninum Larvae in the Murine Model,” The Journal of Parasitology, vol. 85, no. 5, pp. 779–784, 1999. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press (US), 2011.

- (United States Department of Agriculture) USDA, Animal Welfare Act. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Publishing Office., 2018.

| Hamster | Sex | Infection Isolate | Worm burden | Mean ± SD | Combined EPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Stat6- derived A. cey | 48 | 58.0 ± 14.8 | 533 |

| 2 | M | Stat6- derived A. cey | 51 | ||

| 3 | M | Stat6- derived A. cey | 75 | ||

| 4 | M | NSG derived A. cey* | 22 | 31 ± 12.7 | 4100 |

| 5 | M | NSG derived A. cey* | 40 | ||

| 6 | M | Hamster derived A. cey* | 35 | 36 ± 1.4 | 1500 |

| 7 | M | Hamster derived A. cey* | 37 |

| Mouse | Strain | Sex | Infective dose | Days PI | #L3s in SI | #L3s in MS | MS weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NOD scid | M | 1000 | 7 | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | NOD scid | M | 1000 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 8.51 |

| 3 | Stat6- | F | 200 | 10 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| 4 | Stat6- | F | 200 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 8.26 |

| 5 | Stat6- | M | 200 | 10 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| 6 | Stat6- | M | 200 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 8.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).