1. Introduction

Spirulina, whose name comes from a Latin word for “helix” or “spiral” [

1,

2], is a genus of filamentous multicellular cyanobacteria in the phylum Cyanophyceae [

3]. The dietary supplement named ‘spirulina’ refers to the biomass of a species formerly known as

Spirulina platensis, but now known as

Arthrospira platensis.

A. platensis is an aerobic, multicellular, and filamentous photosynthetic cyanobacterium that live in alkali environments with high levels of salts, such as carbonate and bicarbonate, in subtropical and tropical areas [

4,

5].

A. platensis cells also contain abundant vitamins (e.g., vitamin B

12 [

6], β-carotene [

7]), proteins (60–70%) [

8], the unsaturated fatty acid gamma-linolenic acid [

9], and natural pigments, such as zeaxanthin [

10], phycocyanin, and myxoxanthophyll [

11]. Dietary supplements prepared from these cells are is utilized to boost the immune system [

12,

13], increase blood circulation [

14,

15], and as a food additive [

16] and dietary supplement [

17,

18].

Taxonomic identification of the species in

Arthrospira is challenging due to morphological variability caused by genetic drift, possibly due to changing environmental conditions. In natural ecosystems and cultures,

A. platensis filaments have two distinct morphological types: spiral or linear [

19]. The linearization of

A. platensis from its spiral form mainly occurs in artificial conditions, such as in laboratories and industrial settings [

20], and it is now widely accepted that the linear shape is one of the major morphologies of

A. platensis [

21,

22]. The linear morphology was long considered to be a permanent degeneration that could not be reversed [

23], although Wang and Zhao [

24] reported that linear filaments can revert to their original spiral morphology under certain conditions. In addition to a permanent morphological degeneration caused by genetic changes, other studies reported alterations in the trichome length and helicity of

A. platensis in response to external factors, such as changes in light spectrum, salinity, and glucose level [

25,

26].

Many studies of the morphological conversion of different A. platensis strains have focused on changes in morphology, ultrastructure, physiology, biochemistry, and genetics [22,27-31]. However, no research has yet examined the relationship of harvest efficiency with A. platensis morphology. In this study, we examined the relationship of filament length of A. platensis with different types and concentrations of sodium compounds in the growth medium, and then examined the effect of filament morphology on the harvest efficiency using filtration and auto-flotation. We also compared the linear and coiled types of A. platensis in terms of growth rate, photosynthetic activity, and auto-flotation efficiency. Our results provide a foundation led to a hypothesis that explains the relative rarity of linear filaments in nature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Culture Conditions

Arthrospira platensis KCTC AG40101 was cultivated under different conditions, and the effect of the type and concentration of the carbonate source on filament morphology was determined. A spontaneously converted linear A. platensis isolate was screened from the coiled wild-type A. platensis. Both strains were grown in the original SOT medium: 16.8 g/L NaHCO3, 0.5 g/L K2HPO4, 2.5 g/L NaNO3, 1.0 g/L K2SO4, 1.0 g/L NaCl, 0.2 g/L MgSO47H2O, 0.04 g/L CaCl22H2O, 0.01g/L FeSO47H2O, 0.07 g/L Na2EDTA2H2O, and 1 mL of a micronutrient solution. The micronutrient solution consisted of 2.86 g/L H3BO3, 1.81 g/L MnCl24H2O, 0.222 g/L ZnSO44H2O, 0.021 g/L Na2MoO42H2O, 0.08 g/L CuSO4 5H2O, and 0.05 g/L Co(NO3)26H2O. Cells were cultivated in a closed 2 L bottle-type photobioreactor system which had a hydrophobic air filter that was embedded in the bottom of the reactor. During cultivation, the bioreactor was efficiently mixed with 3% CO2 and the photon flux density from a cool white LED lamp was 100 μmol photons/m2∙s.

The different types and concentrations of carbonate compounds were 0.1 M NaHCO3, 0.4 M NaHCO3, and 0.2 M Na2CO3 (instead of 0.2 M NaHCO3 in the original SOT medium). To investigate the effect of the concentration of the sodium ion on filament morphology, 0.2 M NaCl was added to the original SOT medium. A 0.1 L sample of A. platensis filaments grown in SOT medium containing 0.2 M NaHCO3 was used as a preculture for each cultivation experiment. Subsequently, we observed changes in filament morphology over time under different conditions

2.2. Filament Morphology

The morphological variations of A. platensis filaments related with filament length were observed using a hemocytometer (Marienfeld-Superior Counting Chamber) with a 0.1 mm scale. Observations were conducted every three days using an optical microscope (OLYMPUS CKX41). The lengths of ten randomly selected filaments were measured, and averages and standard deviations were presented.

2.3. Monitoring of Cell Growth

Cell density was analyzed using a spectrophotometer (JASCO V-730 UV-Vis spectrometer) with measurements of absorbance at 680 nm (OD680nm, corresponding to chlorophyll) every 3 days.

2.4. Efficiency of Auto-Flotation and Filtration

To measure the auto-flotation efficiency, filaments in the stationary phase were collected and placed into 50 mL self-standing Falcon tubes. The tubes were briefly shaken and then allowed to stand. A 1 mL sample was then taken from a depth of 3 cm after 0, 3, 6, 9, and up to 24 h. To determine the auto-flotation efficiency, a spectrophotometer (JASCO V-730) was used to measure OD680nm of this sample. The auto-flotation efficiency at each time was then expressed as:

where OD680 (t0) is the initial cell concentration, and OD680 (ti) is the cell concentration at time ti.

Filtration efficiency was determined by passing coiled and linear filaments through standard sieves with pore sizes of 0.1 and 0.075 mm. The cell concentration (OD680 nm) was measured using a spectrometer (JASCO V-730), and filtration efficiency was expressed as:

where OD680 (t0) is the initial cell concentration (before filtration) and OD680 (tf) is the cell concentration after filtration.

2.5. Biomass and Photosynthetic Activity

The in vivo photosynthetic activity of filaments was determined by measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence with a Multi-Color-PAM fluorimeter (Heinz Walz, Germany) after dark adaptation of filaments for 20 min. A stepwise increase in the level of the actinic LED light (440 nm), with a step width of 1 min, was used to record light response curves. The relative electron transport rate (rETR) and effective quantum yield of PSII (Y(II)) were calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of NaHCO3 Concentration on Growth and Morphology

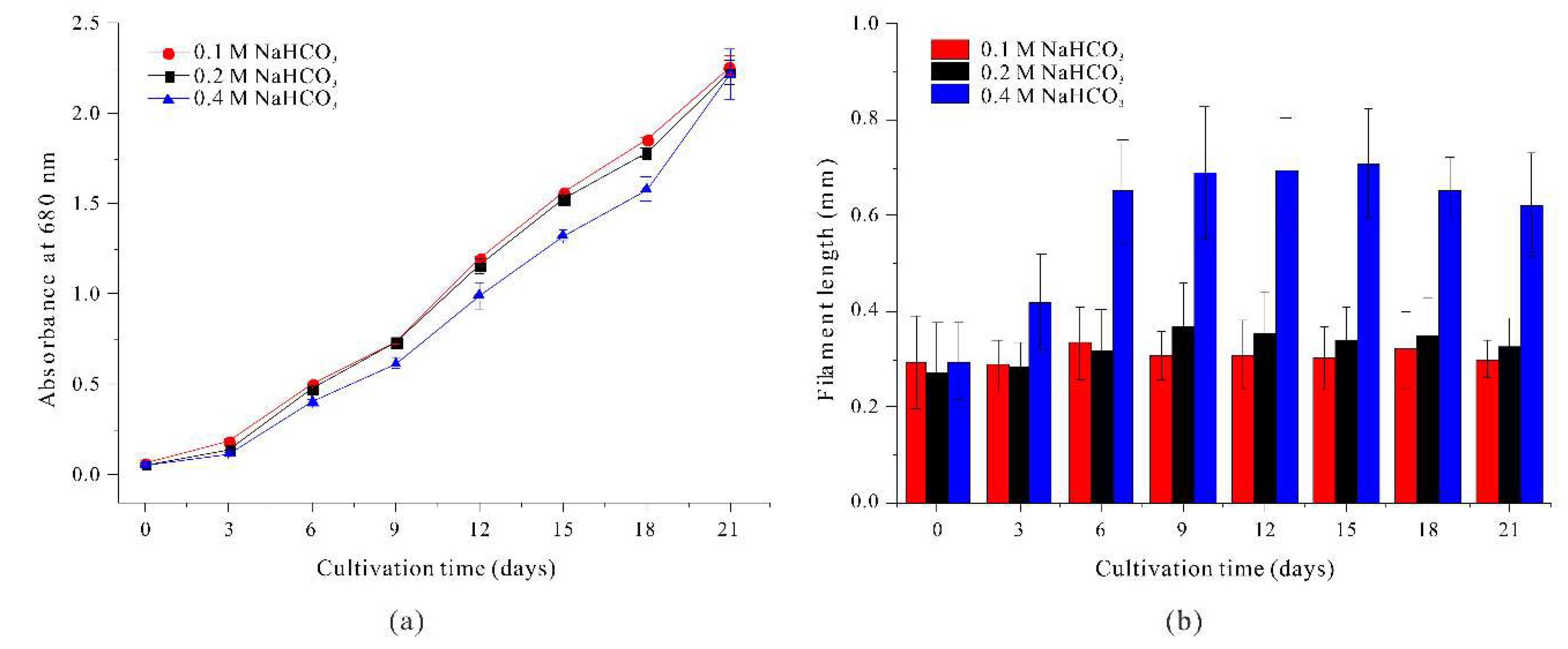

We first investigated the effect of NaHCO

3 concentration on the growth of

A. platensis by culturing filaments in the standard SOT medium (with 0.2 M NaHCO

3), in medium with 0.1 M NaHCO

3, and in medium with 0.4 M NaHCO

3 (

Figure 1a).

The results show no significant differences in cell growth when the medium had 0.1 M and 0.2 M NaHCO3, but the initial growth rate was slightly delayed when the medium had 0.4 M NaHCO3, although the biomass on day 21 was similar in all three groups.

The NaHCO

3 concentration also affected filament length (

Figure 1b). In particular, the average filament length was similar when the medium had 0.1 M or 0.2 M NaHCO

3, and there were no significant changes during the 21-day culture period. However, when the medium had 0.4 M NaHCO

3, the filament length increased significantly on day 3 (from 0.2950 mm to 0.4180 mm) and the length reached 0.6498 mm on day 6, more than twice the initial length. The filament length continued to increase gradually until day 15, and then decreased slightly on day 18 and day 21. This decrease in filament length after day 18 is likely attributable to depletion of NaHCO

3 from the growth medium. These results show that the NaHCO

3 concentration affected the morphology of

A. platensis filaments, in that a higher concentration induced a significant elongation of the linear filaments.

3.2. Effect of Sodium Ion Concentration on Growth and Morphology

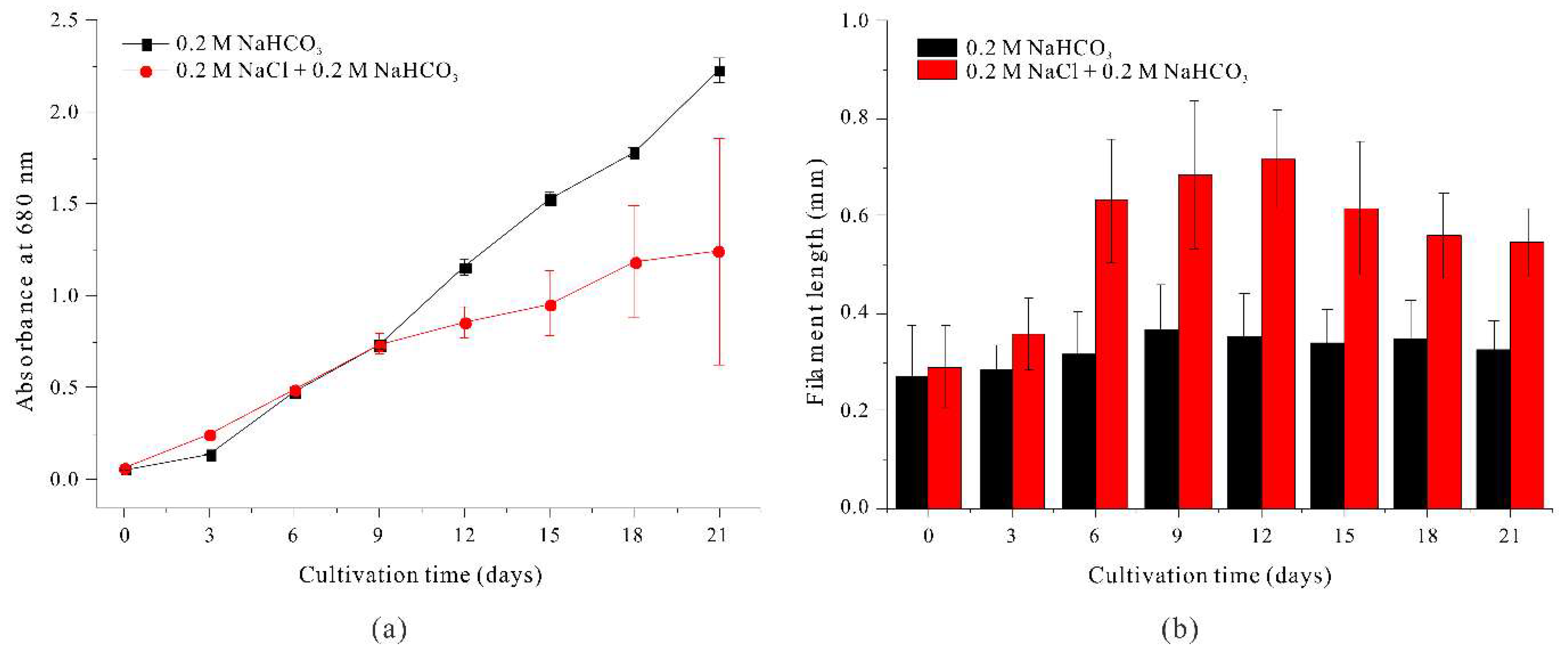

We then examined whether the increased length of A. platensis filaments when grown with 0.4 M NaHCO3 was due to the increased sodium concentration. Thus, we initially cultured filaments in the standard SOT medium (which contains 0.2 M NaHCO3), transferred them into medium with 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO3, and then determined changes in growth and morphology.

The results show that filament length was greater beginning on day 6 when filaments were grown in medium that contained 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO

3 (

Figure 2b), reaching a maximum of approximately 0.7161 mm on day 12, but decreasing slightly thereafter.

This response is similar to the effect of 0.4 M NaHCO3, and indicates that increased concentration of the sodium ion was responsible for the elongation of A. platensis filaments.

However, we also observed distinct differences in filament morphology when filaments were grown with a 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO3 rather than 0.4 M NaHCO3. In particular, in the medium with 0.2 M NaCl, both the filament length and helix pitch increased without changes in filament width. Previous studies reported similar effects of sodium concentration on the spiral structure of A. Platensis filaments. For example, Kebede (1997) observed abnormally long trichomes under low salinity conditions (13 g/L) due to salinity stress in the presence of different sodium salts (NaHCO3, NaCl, Na2SO4), but short and dense spiral structures in high-salinity NaCl-based media (55–68 g/L). Nosratimovafagh et al. (2023) demonstrated that helix length, diameter, and pitch length were affected by the light spectrum, NaCl concentration, and glucose level. In particular, they showed that a higher NaCl concentration combined with specific light conditions led to longer filaments and increased helical pitch. In the present study, sodium-mediated effects on filament length and helical pitch also affected the harvest efficiency of A. platensis by altering auto-flotation, as described in more detail below.

We also examined the effect of sodium ion concentration on the growth of

A. platensis (

Figure 2a). The results show that a high concentration of NaCl significantly inhibited the growth beginning on day 12. This negative effect may be attributed to the reduced efficiency of light utilization caused by salt stress, specifically the presence of Cl⁻ ions [

25]. Thus, these initial experiments confirmed that a higher concentration of sodium ions in the medium increased filament length but also inhibited cell growth, making this medium unsuitable for culturing of

A. platensis.

3.3. Effect of Cultivation of Using 0.2 M Na2CO3 as a Carbonate Source

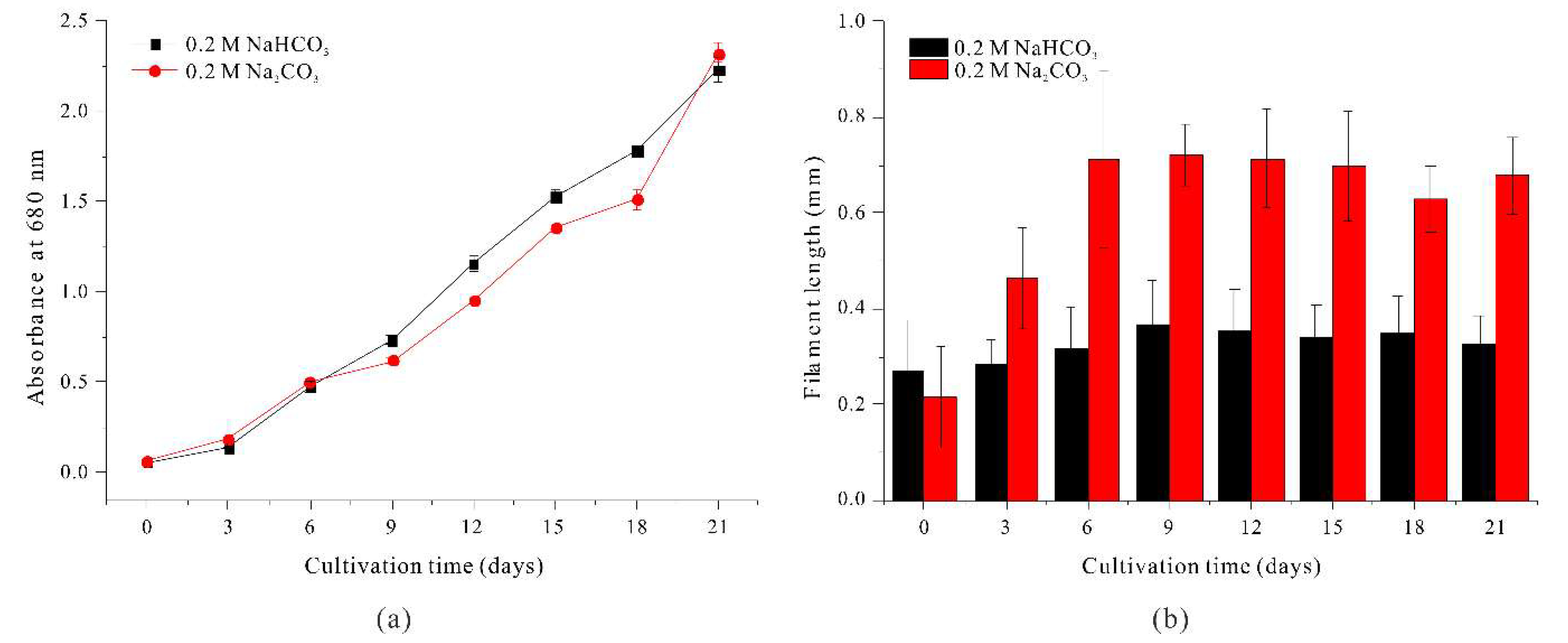

As the length of A. platensis filaments increase, the efficiency of filtration harvesting also increases. Thus, the growth of long filaments with a moderate amount of sodium ions (to prevent growth inhibition) can provide more efficient cultivation. When 0.2 M NaCl was added to the standard SOT medium, the length of filaments increased, but growth was greatly inhibited and the filaments clumped together, making sustainable culture problematic. Similarly, although cultivation in a medium with 0.4 M NaHCO3 led to increased filament length, it required a doubling of the carbonate source, making cultivation less cost-effective. To address this issue, we measured the growth and morphology of filaments cultured in medium in which the standard 0.2 M NaHCO3 was replaced with 0.2 M Na2CO3 (an equivalent molar concentration of sodium ions as medium with 0.4 M NaHCO3).

Our results show that filament length was similar when

A. platensis was grown in medium with 0.2 M Na

2CO

3 and medium with 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO

3. In particular, filament length more than doubled by day 3, continued to increase, and reached a maximum of 0.7200 mm at day 9, after which there was a slight decrease (

Figure 3b).

In addition, the growth rate in the medium with 0.2 M Na

2CO

3 was comparable to the growth rate in the medium with 0. 4M NaHCO

3 (

Figure 3a). Therefore, replacing 0.2 M NaHCO

3 with 0.2 M Na

2CO

3 in the standard SOT medium led to a more than a two-fold increase in filament length and did not significantly inhibit growth. These findings also confirm that the concentration of sodium ions was directly related to the length of

A. platensis filaments.

Moreover, filament length was similar when

A. platensis was grown in medium with 0.2 M Na

2CO

3, medium with 0.4 M NaHCO

3, and medium with 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO

3 (

Figure 3b). In the Na

2CO

3 medium, filament length was 0.2164 mm on day 0, 0.4634 mm on day 3, and 0.7200 mm on day 9, followed by a slight decrease of length (

Figure 3b). Notably, the growth rate was similar when the medium contained 0.2 M Na

2CO

3 and 0.4 M NaHCO

3 (

Figure 3a).

These results demonstrate that replacing 0.2 M NaHCO3 with 0.2 M Na2CO3 in standard SOT medium did not significantly inhibit growth and more than doubled filament length. Moreover, the similar filament length under conditions with identical sodium ion concentrations (0.4 M NaHCO3 vs. 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO3) indicates that a higher sodium ion concentration led to increased filament length.

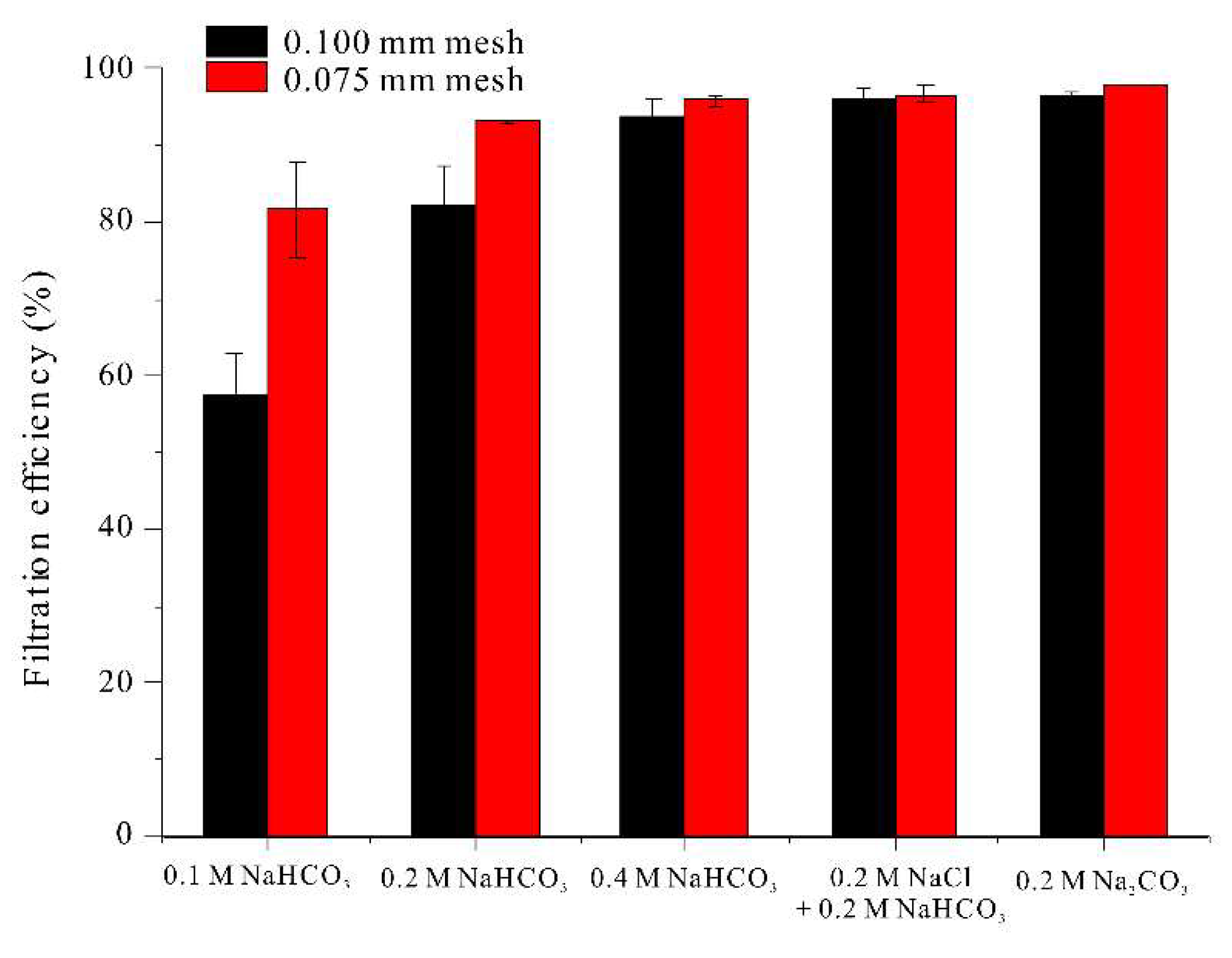

3.4. Effect of Different Carbonates on Harvest Efficiency

The harvesting of microalgae accounts for 20 to 30% of the total cost of biomass production when using energy-intensive methods, such as centrifugation [

32,

33]. Therefore, optimizing harvesting methods based on filtration and flotation is critically important for decreasing energy consumption and harvest time and for enabling recycling of growth media. We therefore evaluated the impact of variations in morphology and filament length in

A. platensis, which were induced by adjusting the carbonate anion and the sodium cation, on the efficiency of harvest

via filtration and flotation.

Thus, we examined the effect of mesh sizes of 0.100 mm and 0.075 mm to consider the efficiency of water drainage, a variable related to harvest time (

Figure 4).

For a medium that increased filament length to 0.7 mm or more (0.4 M NaHCO3, 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO3, 0.2 M Na2CO3), the harvesting efficiency was more than 93% for both mesh sizes. As expected, the harvesting efficiencies for filaments cultured in medium with 0.1 or 0.2 M NaHCO3 conditions were much lower (57% and 78% when using the 0.100 mm mesh). These results demonstrate that a harvest efficiency of more than 90% with a 0.100 mm mesh can be achieved when the filament length is at least 0.7 mm.

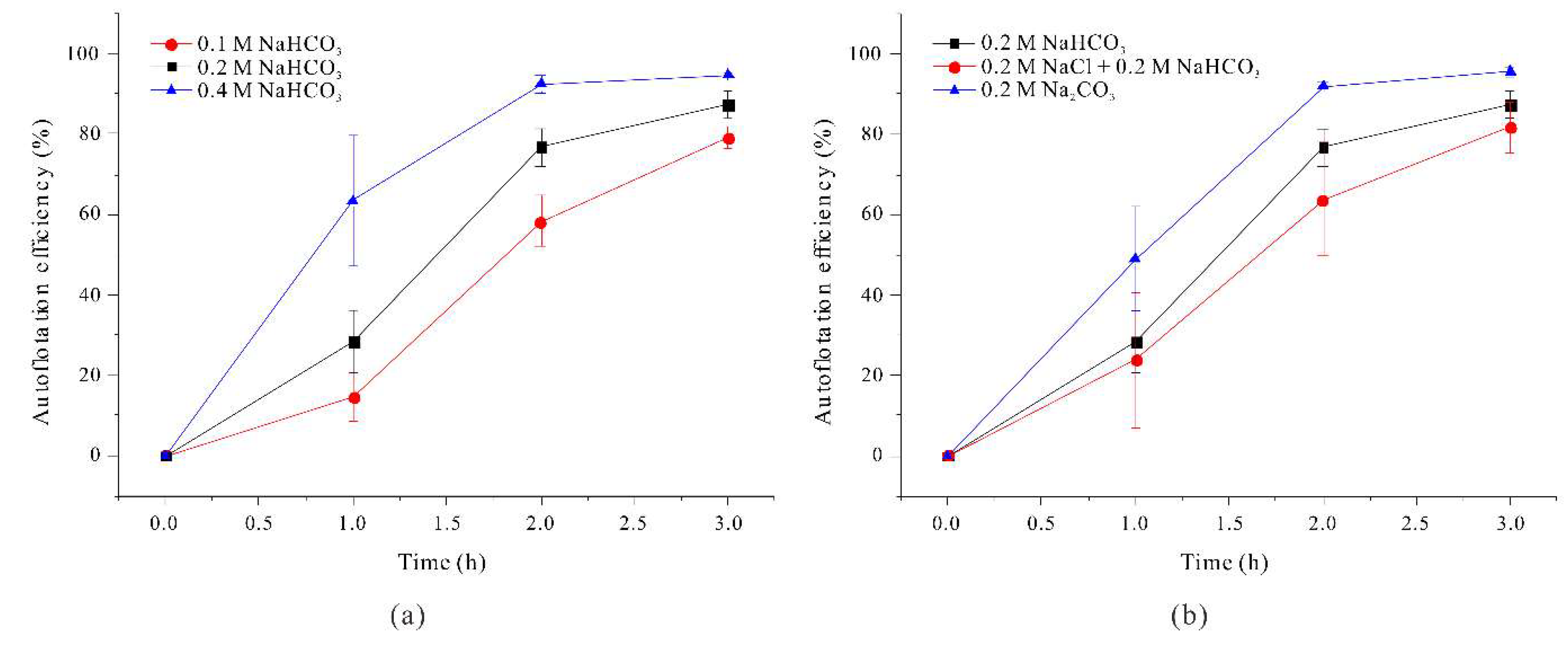

We also evaluated harvest efficiency using a flotation method, in which 50 mL of filaments grown under different conditions were transferred into a self-standing Falcon tube, thoroughly mixed, and then allowed to stand so the filaments could float. We then measured OD680nm of 1 mL samples collected from the midpoint of the Falcon tube and calculated flotation efficiency as the ratio of filament concentration at time t to the initial filament concentration. The results show that harvest efficiency by flotation increased with as the total sodium ion concentration increased (Fig. 5a).

Moreover, when the medium had 0.4 M NaHCO3 or 0.2 M Na2CO3 (conditions that led to the longest filaments), harvest efficiency exceeded 90% within 2 h. The lowest flotation efficiency occurred in medium with 0.1 M NaHCO3 (below 60% even after 2 h). However, the salinity level can also increase the buoyancy of an object. Therefore, it cannot be definitively concluded that changes in A. platensis filament length, which was determined sodium concentration, was the sole factor that affected harvest efficiency.

Considering the increased cost associated with the use of additional medium components, our results demonstrate that a growth medium with 0.2 M Na2CO3 was most effective for maximizing the efficiency of auto-flotation. Additionally, our experiments with the 0.2 M NaCl + 0.2 M NaHCO3 medium suggest that although this medium led to increased filament length, it also decreased flotation efficiency, presumably due to internal morphological changes caused by salt stress.

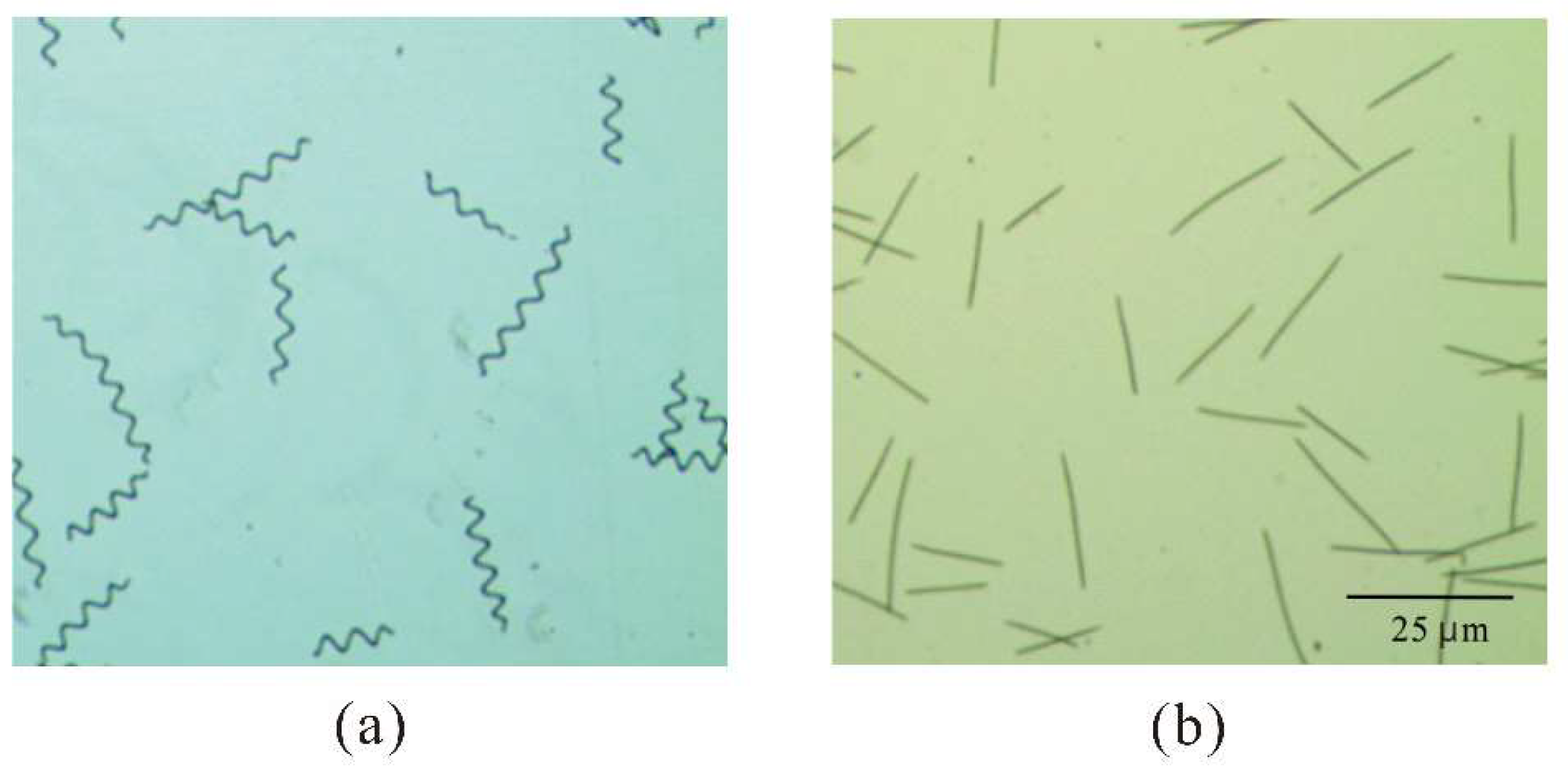

3.5. Screening of Linear Filaments

We obtained linear filaments of A. platensis by inducing the spontaneous conversion of coiled filaments. For screening of linear filaments, we passed a culture consisting of linear and coiled filaments through a sieve with 30 µm pores. Because the helix diameter of spiral filaments is greater than 30 µm, most of the coiled filaments remained on top of the sieve. Following several passages through the sieve, filaments that passed through were added into a 96-well microplate. Then, based on microscopic observations, we selected samples that only contained linear filaments for cultivation. We also collected coiled filaments from filaments that remained on top of the sieve. After this screening procedure, we observed no morphological reversion from the linear to coiled form, although linear filaments were readily generated from coiled filaments.

3.6. Photosynthesis and Biomass Accumulation of Linear Filaments

Notably, our microscopic observations of samples of linear filaments and coiled filaments (

Figure 6a and b) showed that when these samples had the same optical density (OD

680nm = 0.5), there were about two-fold more linear filaments than coiled filaments (data not shown).

To compare light penetration of cultures of linear and coiled filaments, we set up two transparent rectangular bottles (50 × 100 × 30 cm) in front of a light panel, so that the photon flux density was 100 µmol photons m

-2 s

-1 at the outer surface of each bottle. Then, we adjusted the concentration of cells in each bottle so that the transmitted light had a photon flux density of 10 µmol photons m

-2 s

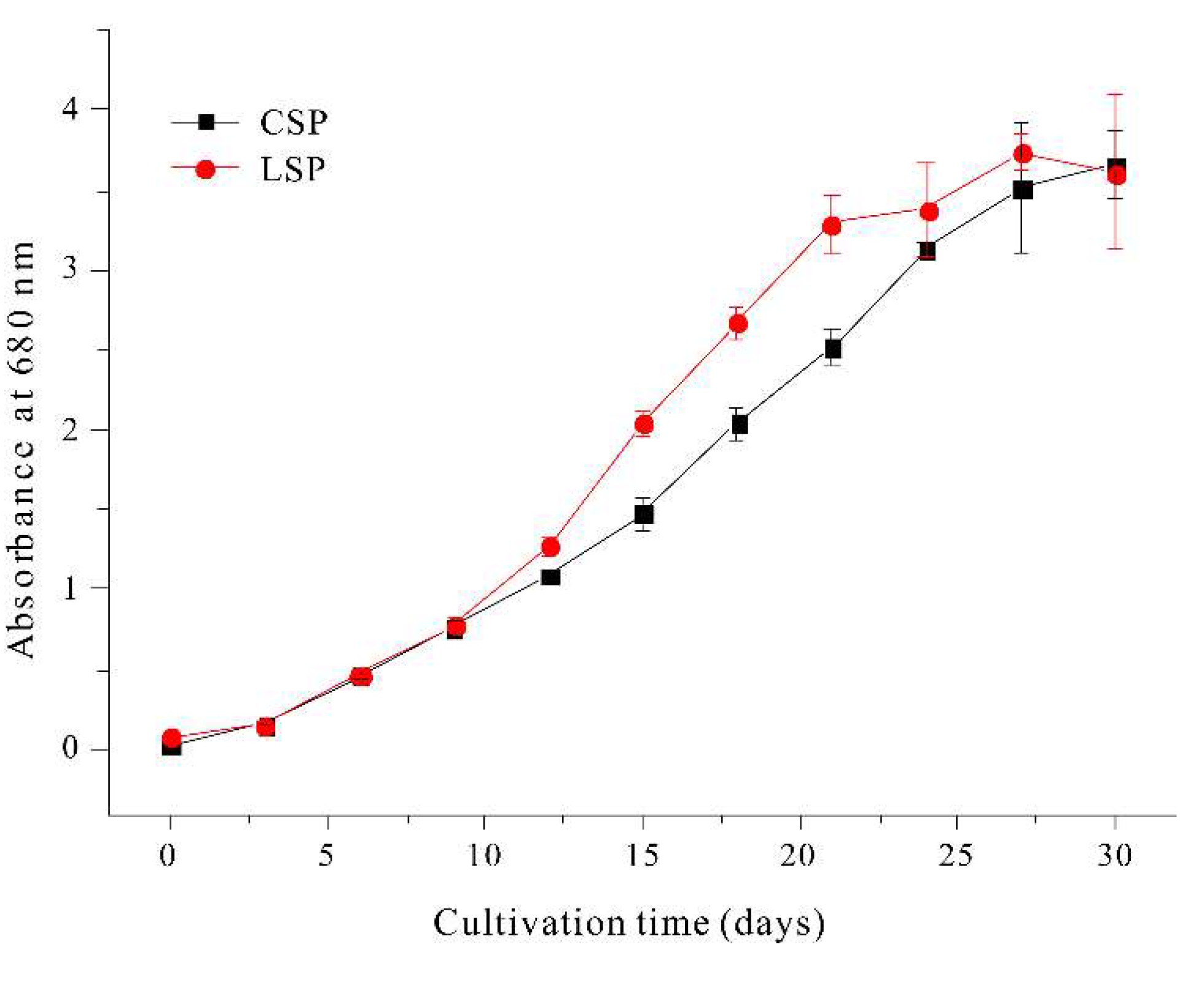

-1. Under these conditions, the bottle with linear filaments had 104±5 filaments/mL and the bottle with coiled filaments had 62±5 filaments/mL (data not shown). In other words, the linear filaments allowed more light penetration, had decreased self-shading, and had less light scattering due to their narrow linear shape. Culture density and light absorbance are related to the yield during photoautotrophic culturing in regard to the total volume of the photobioreactor. The cellular growth of the two filament types was compared under the same growth conditions. Other research reported that linear filaments of

A. platensis had a lower growth yield than spiral filaments [

34]. However, our results showed that the linear filaments had a faster growth rate and 1.5-times higher maximal cell density than the coiled filaments (

Figure 7).

This result is similar to the results from analysis of a

Synechocystis Olive mutant that had a partially truncated light harvesting antenna, which increased penetration depth of light into the culture volume and consequently increased time-space-productivity [

35].

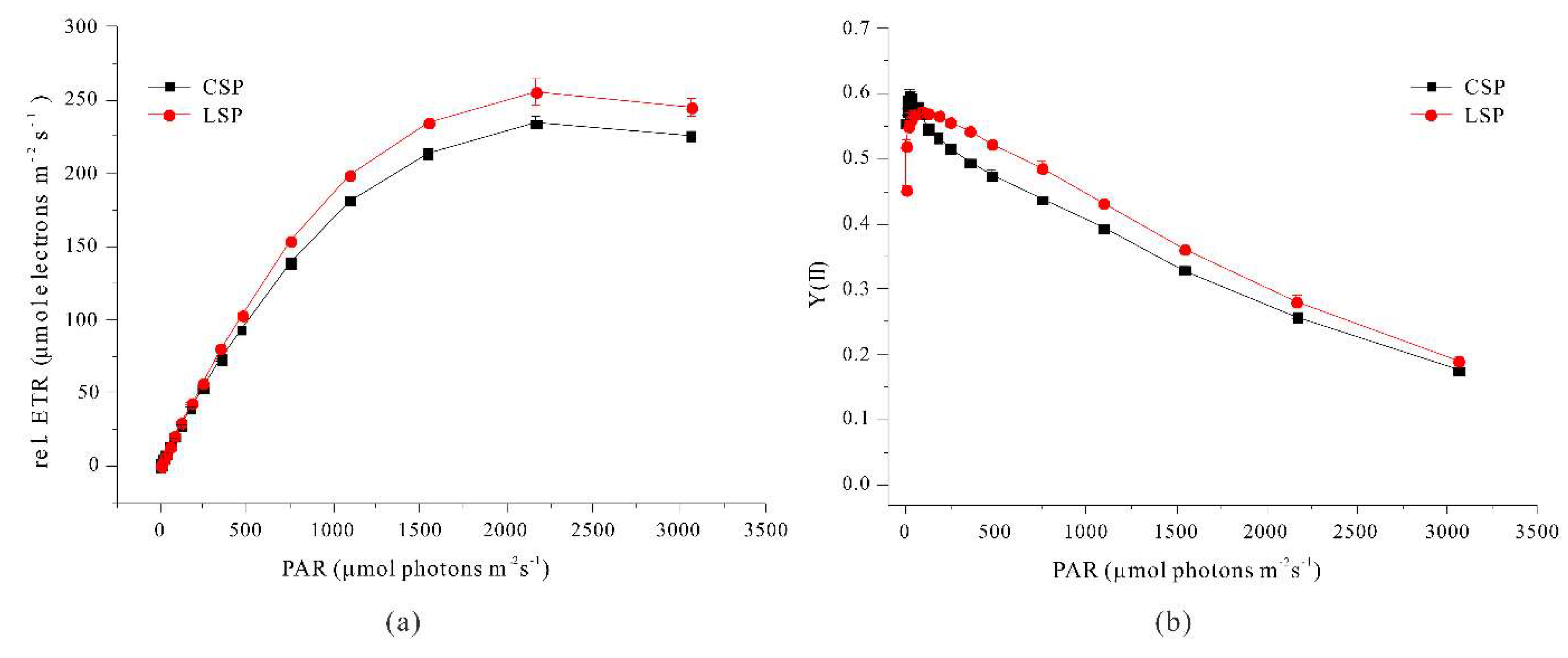

Moreover our linear filaments had increased photosynthetic activity based on measurements of the relative electron transport rate and quantum yield of PS II (

Figure 8).

This implies that the linear filaments had more resistance to high light levels than the coiled filaments. It is interesting that the coiled and linear filaments had no significant difference in the maximum quantum yield of PSII at very low photon flux density, which implies similar PSII status of these different filaments at low light levels. Thus, the higher photosynthetic efficiency of linear filaments is likely due to the greater light penetration throughout the culture.

The morphological conversion of coiled filaments to linear filaments was mainly believed to be heritable and stable due to genetic drift (Wang and Zhao, 2013, Muhling et al. 2013). However, our measurements showed that the coiled filaments had lower photosynthetic efficiency. No studies have reported linear

A. platensis filaments in nature, although linearization of spiral filaments frequently occurs in laboratories and mass cultures. Wang and Zhao [

24] reported that linear filaments of

A. platensis could revert to the original coiled morphology under certain conditions. However, spontaneous conversion of linear filaments to coiled filaments based genetic changes cannot explain the dominance of the coiled form in nature due to the long process of

A. platensis evolution. In the present study, we found distinct differences in auto-flotation activity of linear and coiled filaments, and it is likely that the greater buoyancy of coiled filaments gives them survival advantages in nature.

3.7. Auto-Flotation Efficiency of Linear and Coiled Filaments

It is reasonable to speculate the linearization of

A. platensis could also occur in nature. Natural aquatic environments differ from the culture conditions in a photobioreactor, in which artificial mixing is achieved by shaking or airlifting.

A. platensis filaments are inherently buoyant due to their gas vesicles [

36]. In competition among photosynthetic microorganisms in nature, migration to the water surface will lead to increased photosynthesis and growth. The flotation activity of

A. platensis could be affected physiological parameters.

We also investigated the effect of filament morphology on auto-flotation over a period of 24 h (

Figure 9).

The coiled filaments achieved an auto-floating efficiency of about 90%. In contrast, the linear filaments achieved a maximum auto-floating efficiency of only about 10%, even after 24 h, presumably because these filaments are thin (diameter of 6–12 μm [

37]) and have a compact structure. In fact, when linear filaments and coiled filaments are mixed and shaken, the linear filaments mostly accumulate in the middle layer, while the coiled filaments accumulate in the upper layer. Consequently, linear filaments of

A. platensis could be excluded by competition with coiled filaments soon after their formation due to their poor auto-flotation, in spite of their better light utilization due to less auto-shading.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that an increase in the concentration of sodium ions in the growth medium led to increases in the length of linear filaments of A. platensis and associated increases in harvest efficiency by filtration and auto-flotation. Specifically, an increase of the sodium ion concentration from 0.2 M to 0.4 M led to a more than doubling of filament length (from 0.3393 mm to 0.7084 mm), and this increase in filament length led to increased filtration efficiency through a standard 0.100 mm sieve (from 78.53% to 93.85%). Linear filaments of A. platensis had superior growth and photosynthetic efficiency compared to coiled filaments in our laboratory experiments. However, linear filaments also have lower buoyancy, so the coiled filaments would tend to dominate at the water surface in natural environments, where the light level is greatest. This may explain the dominance of coiled filaments of A. platensis in natural ecosystems.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2015R1C1A1A01054303).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of in-terest.

References

- Choonawala, B.B. Spirulina production in brine effluent from cooling towers. Durban University of Technology, 2007.

- Ohmori, M.; Ehira, S. Spirulina: an example of cyanobacteria as nutraceuticals. Cyanobacteria: an economic perspective 2014, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.K.; Saleh, A.M. Spirulina-an overview. International journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical sciences 2012, 4, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.-S. Growth of Spirulina platensis in effluents from wastewater treatment plant of pig farm. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 1993, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, R.A.; Sudhakar, K.; Rana, R. Spirulina–From growth to nutritional product: A review. Trends in food science & technology 2017, 69, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, V.; Drivas, G. Spirulina and vitamin B12. JAMA 1982, 248, 3096–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, C.; Umesh, B.; Manoharan, R. Beta-carotene studies in Spirulina. Bioresource technology 1991, 38, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranraj, P.; Sivasakthi, S. Spirulina platensis–food for future: a review. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. Technol 2014, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Choopani, A.; Poorsoltan, M.; Fazilati, M.; Latifi, A.M.; Salavati, H. Spirulina: a source of gamma-linoleic acid and its applications. Journal of Applied Biotechnology Reports 2016, 3, 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Wang, J.; Suter, P.M.; Russell, R.M.; Grusak, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yin, S.; Tang, G. Spirulina is an effective dietary source of zeaxanthin to humans. British journal of nutrition 2012, 108, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghari, A.; Fazilati, M.; Latifi, A.M.; Salavati, H.; Choopani, A. A review on antioxidant properties of Spirulina. Journal of Applied Biotechnology Reports 2016, 3, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, P. Spirulina as an Immune Booster for Fishes.

- Ghode, S.P.; Ghode, P.D.; Chatur, V.M.; Kolhe, R.; Patil, S. Formulation and Development of Spirulina (Athrospira plantasis) Loaded Chocolates as Immunity Boosters.

- Martínez-Sámano, J.; Torres-Montes de Oca, A.; Luqueño-Bocardo, O.I.; Torres-Durán, P.V.; Juárez-Oropeza, M.A. Spirulina maxima decreases endothelial damage and oxidative stress indicators in patients with systemic arterial hypertension: Results from exploratory controlled clinical trial. Marine drugs 2018, 16, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizzo, A.; Conte, G.M.; Sommella, E.; Damato, A.; Ambrosio, M.; Sala, M.; Scala, M.C.; Aquino, R.P.; De Lucia, M.; Madonna, M. Novel potent decameric peptide of Spirulina platensis reduces blood pressure levels through a PI3K/AKT/eNOS-dependent mechanism. Hypertension 2019, 73, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metekia, W.; Ulusoy, B.; Habte-Tsion, H.-M. Spirulina phenolic compounds: natural food additives with antimicrobial properties. International Food Research Journal 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Water, J.V.d.; Gershwin, M.E. Effects of a Spirulina-based dietary supplement on cytokine production from allergic rhinitis patients. Journal of Medicinal Food 2005, 8, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten Rutar, J.; Jagodic Hudobivnik, M.; Nečemer, M.; Vogel Mikuš, K.; Arčon, I.; Ogrinc, N. Nutritional quality and safety of the spirulina dietary supplements sold on the Slovenian market. Foods 2022, 11, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogato, T.; Kifle, D. Morphological variability of Arthrospira (Spirulina) fusiformis (Cyanophyta) in relation to environmental variables in the tropical soda lake Chitu, Ethiopia. Hydrobiologia 2014, 738, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongsthong, A.; Sirijuntarut, M.; Prommeenate, P.; Thammathorn, S.; Bunnag, B.; Cheevadhanarak, S.; Tanticharoen, M. Revealing differentially expressed proteins in two morphological forms of Spirulina platensis by proteomic analysis. Molecular biotechnology 2007, 36, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciferri, O. Spirulina, the edible microorganism. Microbiological reviews 1983, 47, 551–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Fu, H.; Zou, X. Effect of Cu 2+ on PS II Activity and Energy Transfer of Phycobillisome in Intact Cells of Spirulina platensis. In Proceedings of the Chinese Science Abstracts Series B; 1995; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli, L. Morphology, ultrastructure and taxonomy of Arthrospira (Spirulina) maxima and Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis. Spirulina platensis (Arthrospira): physiology, cell-biology and biotechnology 1997, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.P.; Zhao, Y. Morphological reversion of Spirulina (Arthrospira) platensis (Cyanophyta): from linear to helical 1. Journal of Phycology 2005, 41, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E. Response of Spirulina platensis (= Arthrospira fusiformis) from Lake Chitu, Ethiopia, to salinity stress from sodium salts. Journal of Applied Phycology 1997, 9, 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Nosratimovafagh, A.; Esmaeili Fereidouni, A.; Krujatz, F. Effect of light spectrum, salinity, and glucose levels on Spirulina morphology. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society 2023, 54, 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, R.A. Uncoiled variants of Spirulina platensis (Cyanophyceae: Oscillatoriaceae). 1981.

- Jeeji-Bai, N. Competitive exclusion or morphological transformation? A case study with Spirulina forsifomis. Arch Hydrobiol (suppl) 1985, 71, 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Vonshak, A. Strain selection of Spirulina suitable for mass production: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Seaweed Symposium: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Seaweed Symposium held in Sao Paulo, Brazil, July 27–August 1, 1986, 1987. pp. 75-77.

- Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Jia, X.; Cui, H.; Xu, B. The effect of environmental factors and gamma-rays on the morphology and growth of Spirulina platensis. Journal of Zhejiang Agricultural University 1997, 23, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, H.; Zhu, J.; Jia, X.; Qian, K. The comparison on growth rate and photopigments of filaments of Spirulina platensis strain Z with different morphology. Wei Sheng wu xue bao= Acta Microbiologica Sinica 1998, 38, 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, N.; Nayak, M.; Lee, B.; Chang, Y.-K. Efficient microalgae harvesting mediated by polysaccharides interaction with residual calcium and phosphate in the growth medium. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 234, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, G.; Alam, M.A.; Mofijur, M.; Jahirul, M.; Lv, Y.; Xiong, W.; Ong, H.C.; Xu, J. Modern developmental aspects in the field of economical harvesting and biodiesel production from microalgae biomass. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 135, 110209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.P.; Zhao, Y. Morphological reversion of Spirulina (Arthrospira) platensis (Cyanophyta): from linear to helical. Journal of Phycology 2005, 41, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.-H.; Bernat, G.; Wagner, H.; Roegner, M.; Rexroth, S. Reduced light-harvesting antenna: consequences on cyanobacterial metabolism and photosynthetic productivity. Algal Research 2013, 2, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsby, A.E. Gas vesicles. Microbiological reviews 1994, 58, 94–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotiroudis, T.G.; Sotiroudis, G.T. Health aspects of Spirulina (Arthrospira) microalga food supplement. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society 2013, 78, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).