Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

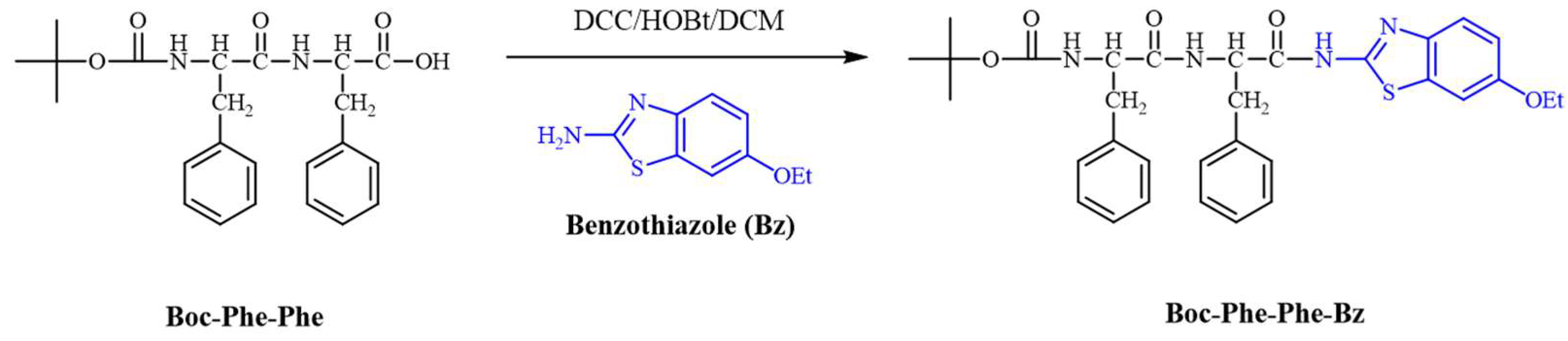

2.1. Synthesis

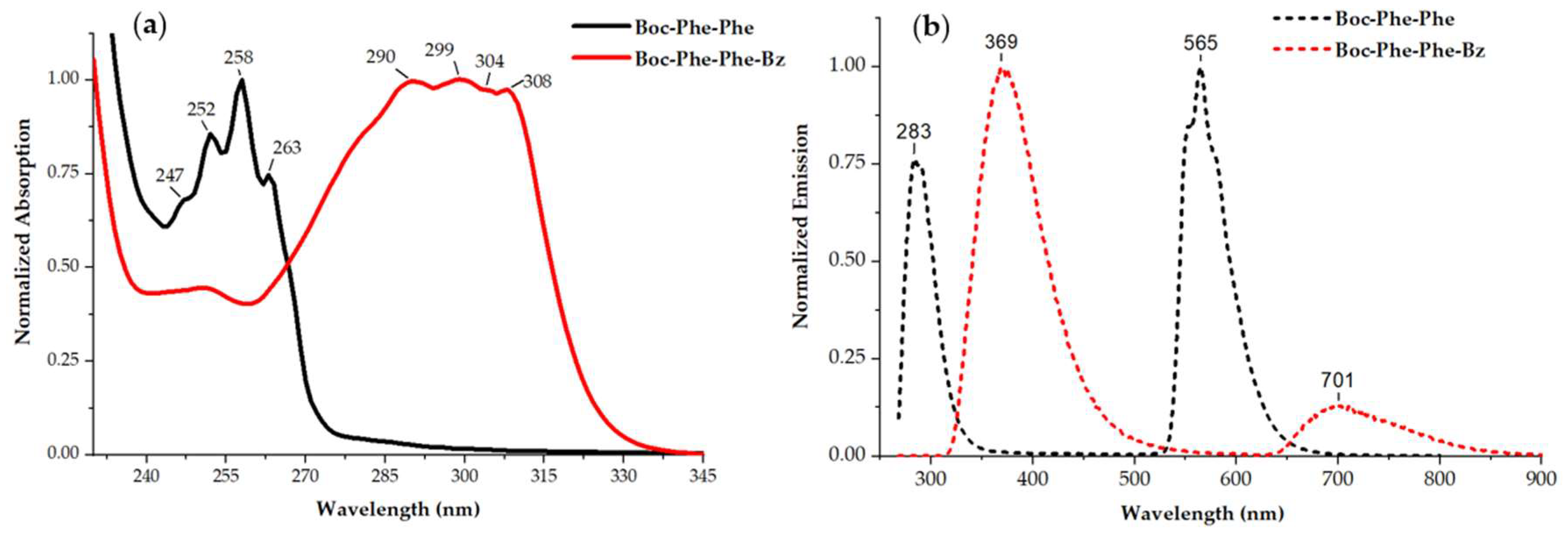

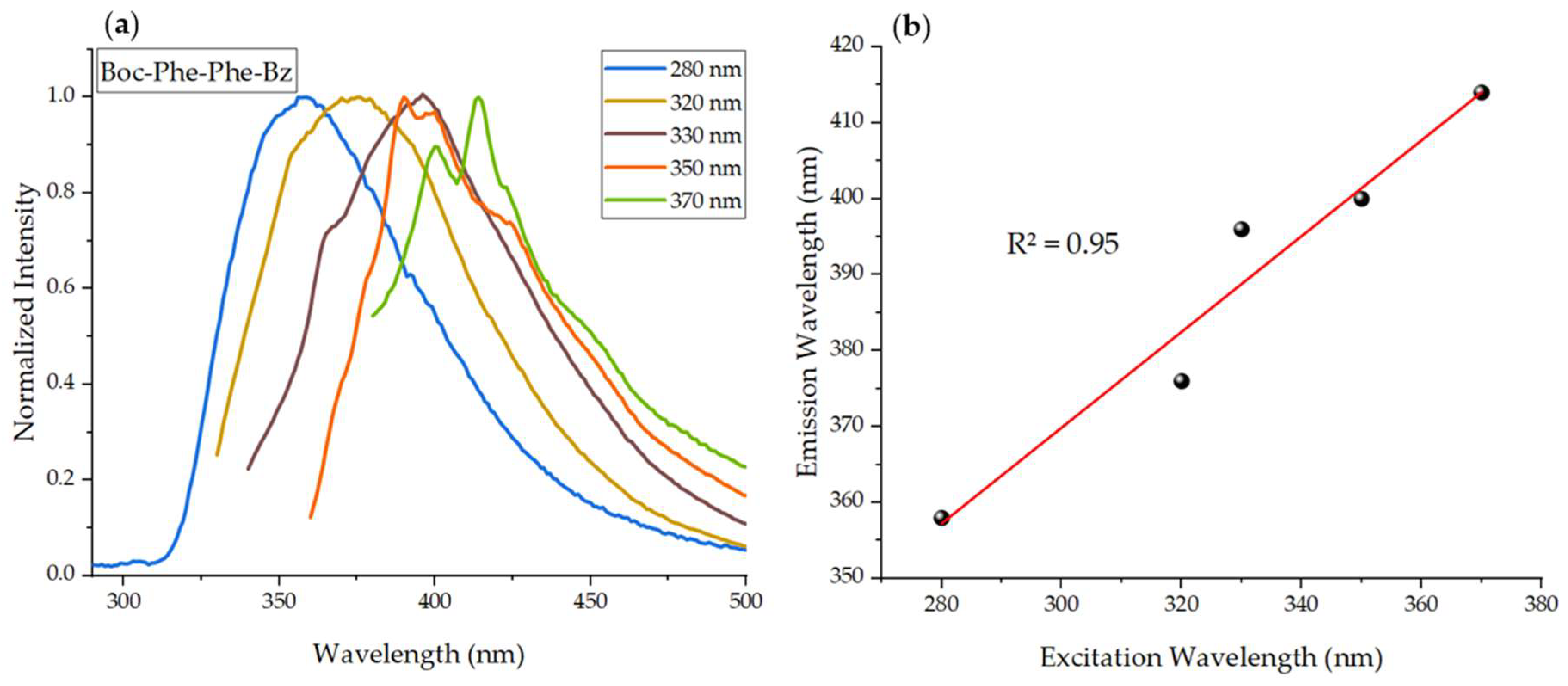

2.2. Linear Optical Properties: Absorption and Fluorescence

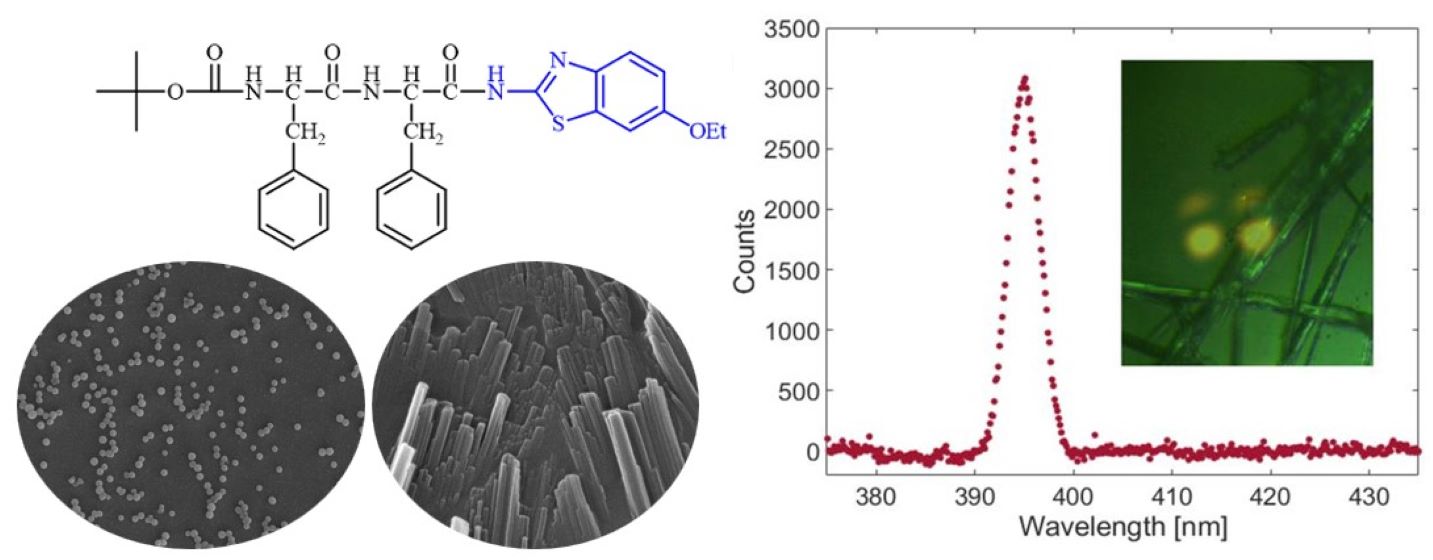

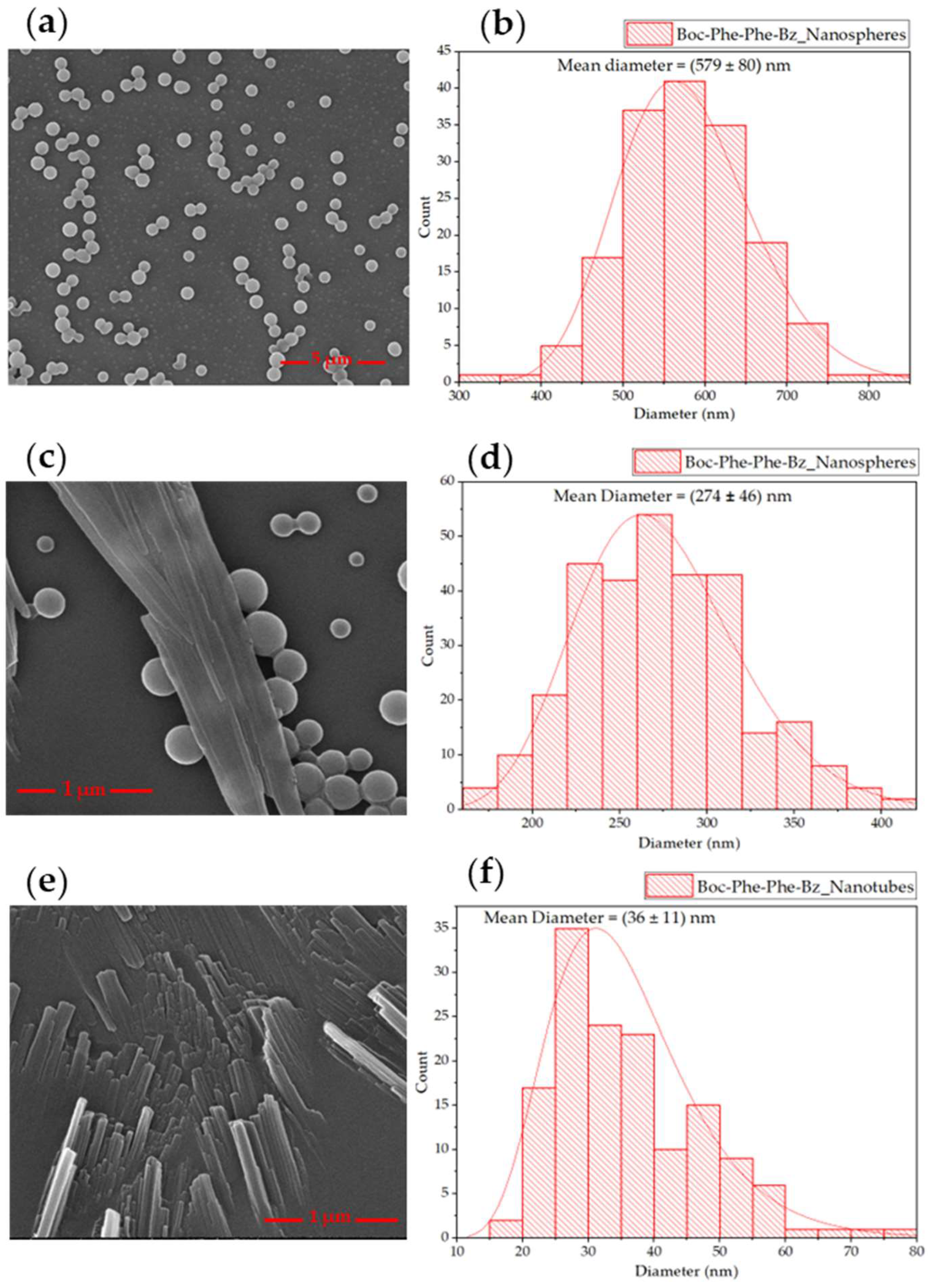

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy of Self-Assembled Nanostructures

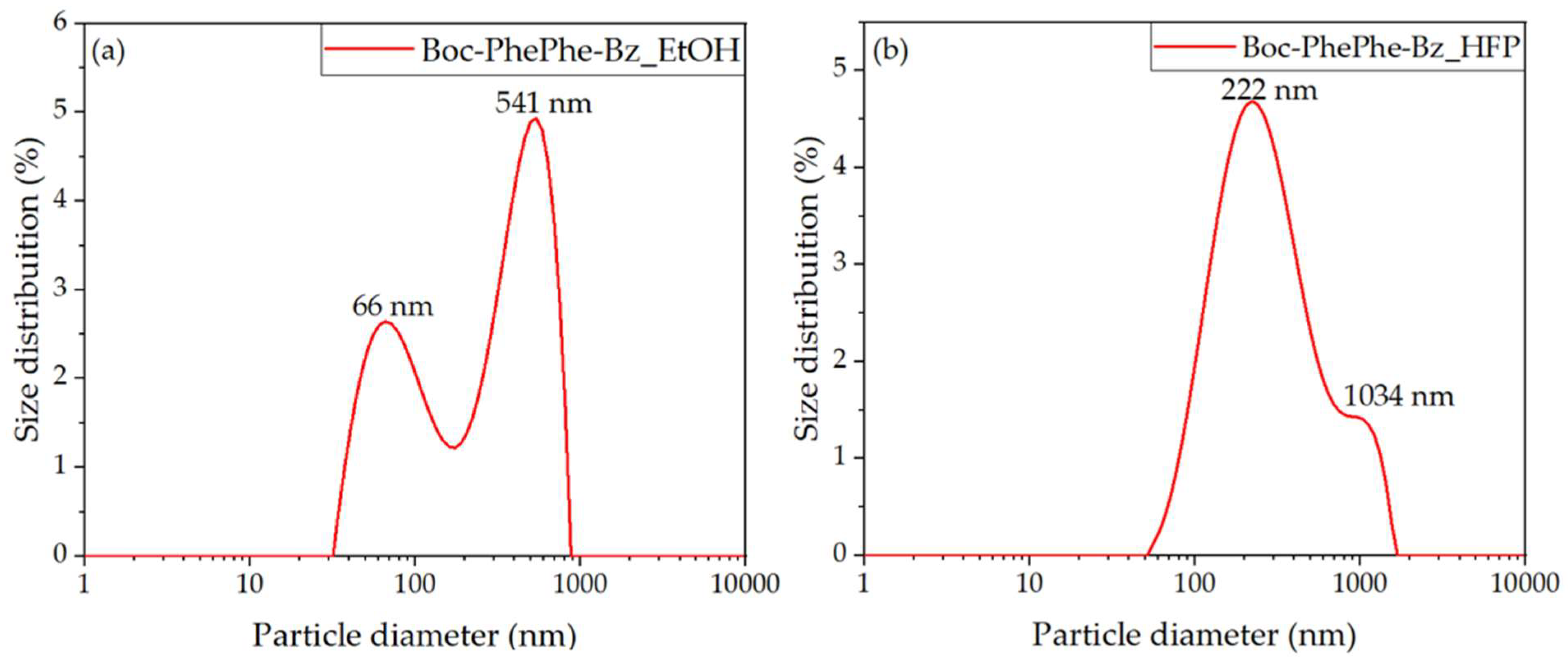

2.4. Dynamic Light Scattering Studies

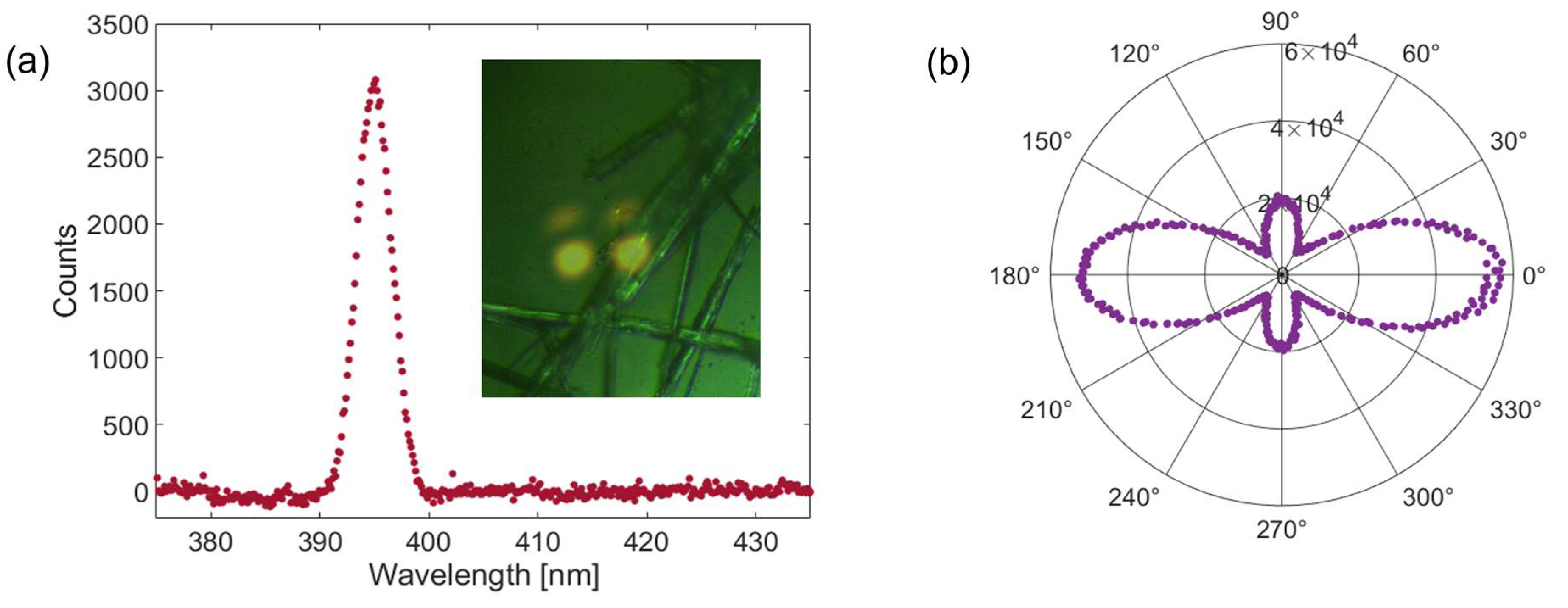

2.5. Nonlinear Optical Response

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Procedure for the Synthesis of tert-butyl ((R)-1-(((R)-1-((6-ethoxybenzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)amino)-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl)amino)-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl)carbamate (Boc-Phe-Phe-Bz)

3.3. Self-Assembly of Dipeptide Nanostructures in HFP/Water and Ethanol/Water Solutions

3.4. Optical Absorption and Fluorescence

3.5. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

3.6. Scanning Electronic Microscopy (SEM)

3.7. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

3.8. Second Harmonic Generation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baptista, R.M.F.; de Matos Gomes, E.; Raposo, M.M.M.; Costa, S.P.G.; Lopes, P.E.; Almeida, B.; Belsley, M.S. Self-assembly of dipeptide Boc-diphenylalanine nanotubes inside electrospun polymeric fibers with strong piezoelectric response. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 4339–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Gazit, E. The physical properties of supramolecular peptide assemblies: from building block association to technological applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6881–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Kol, N.; Yanai, I.; Barlam, D.; Shneck, R.Z.; Gazit, E.; Rousso, I. Self-Assembled Organic Nanostructures with Metallic-Like Stiffness. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 9939–9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Reches, M.; Sedman, V.L.; Allen, S.; Tendler, S.J.B.; Gazit, E. Thermal and Chemical Stability of Diphenylalanine Peptide Nanotubes: Implications for Nanotechnological Applications. Langmuir 2006, 22, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amdursky, N.; Beker, P.; Schklovsky, J.; Gazit, E.; Rosenman, G. Ferroelectric and Related Phenomena in Biological and Bioinspired Nanostructures. Ferroelectrics 2010, 399, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbitz, C.H. The structure of nanotubes formed by diphenylalanine, the core recognition motif of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid polypeptide. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2332–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Aronov, D.; Beker, P.; Yevnin, M.; Stempler, S.; Buzhansky, L.; Rosenman, G.; Gazit, E. Self-assembled arrays of peptide nanotubes by vapour deposition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Jia, Y.; Dai, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Controlled Rod Nanostructured Assembly of Diphenylalanine and Their Optical Waveguide Properties. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 2689–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler-Abramovich, L.; Gazit, E. Controlled patterning of peptide nanotubes and nanospheres using inkjet printing technology. J. Pept. Sci. 2008, 14, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reches, M.; Gazit, E. Self-assembly of peptide nanotubes and amyloid-like structures by charged-termini-capped diphenylalanine peptide analogues. Isr. J. Chem. 2005, 45, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Han, T.H.; Kim, Y.-I.; Park, J.S.; Choi, J.; Churchill, D.G.; Kim, S.O.; Ihee, H. Role of Water in Directing Diphenylalanine Assembly into Nanotubes and Nanowires. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnon, Z.A.; Pinotsi, D.; Schmidt, M.; Gilead, S.; Guterman, T.; Sadhanala, A.; Ahmad, S.; Levin, A.; Walther, P.; Kaminski, C.F.; et al. Opal-like Multicolor Appearance of Self-Assembled Photonic Array. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018, 10, 20783–20789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S. Fabrication of novel biomaterials through molecular self-assembly. Nature Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basavalingappa, V.; Bera, S.; Xue, B.; O’Donnell, J.; Guerin, S.; Cazade, P.-A.; Yuan, H.; Haq, E.u.; Silien, C.; Tao, K.; et al. Diphenylalanine-Derivative Peptide Assemblies with Increased Aromaticity Exhibit Metal-like Rigidity and High Piezoelectricity. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7025–7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Hu, W.; Xue, B.; Chovan, D.; Brown, N.; Shimon, L.J.W.; Maraba, O.; Cao, Y.; Tofail, S.A.M.; Thompson, D.; et al. Bioinspired Stable and Photoluminescent Assemblies for Power Generation. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, M.; Li, S.; Cao, D. Novel benzothiazole-based fluorescent probe for efficient detection of Cu2+/S2− and Zn2+ and its applicability in cell imaging. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1324, 343093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, L.; Liu, Z. A benzothiazole-based fluorescent probe for sensing Zn2+ and its application. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2023, 545, 121275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Indurthi, H.K.; Asati, P.; Saha, P.; Sharma, D.K. Benzothiazole based fluorescent probes for the detection of biomolecules, physiological conditions, and ions responsible for diseases. Dyes Pigments 2022, 199, 110074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.E.M.; Abdel-Latif, S.A.; Elgemeie, G.H. Novel Fluorescent Benzothiazolyl-Coumarin Hybrids as Anti-SARS-COVID-2 Agents Supported by Molecular Docking Studies: Design, Synthesis, X-ray Crystal Structures, DFT, and TD-DFT/PCM Calculations. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 19587–19602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Even, N.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Buzhansky, L.; Dodiuk, H.; Gazit, E. Improvement of the Mechanical Properties of Epoxy by Peptide Nanotube Fillers. Small 2011, 7, 1007–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrender, A.K.; Pan, J.; Pudney, C.; Arcus, V.L.; Kelton, W. Red edge excitation shift spectroscopy is highly sensitive to tryptophan composition. J. R. Soc. Interface 2023, 20, 20230337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, A.; Mason, T.O.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Buell, A.K.; Meisl, G.; Galvagnion, C.; Bram, Y.; Stratford, S.A.; Dobson, C.M.; Knowles, T.P.J.; et al. Ostwald’s rule of stages governs structural transitions and morphology of dipeptide supramolecular polymers. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stetefeld, J.; McKenna, S.A.; Patel, T.R. Dynamic light scattering: a practical guide and applications in biomedical sciences. Biophys. Rev. 2016, 8, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, N.; Kramar, J.A. Dynamic light scattering distributions by any means. J. Nanopart. Res. 2021, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Ng, W.B.; Bernt, W.; Cho, N.-J. Validation of size estimation of nanoparticle tracking analysis on polydisperse macromolecule assembly. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishard, A.; Gibb, B.C. Dynamic light scattering–an all-purpose guide for the supramolecular chemist. Supramol. Chem. 2019, 31, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, R.M.F.; Gomes, C.S.B.; Silva, B.; Oliveira, J.; Almeida, B.; Castro, C.; Rodrigues, P.V.; Machado, A.; Freitas, R.B.; Rodrigues, M.J.L.F.; et al. A Polymorph of Dipeptide Halide Glycyl-L-Alanine Hydroiodide Monohydrate: Crystal Structure, Optical Second Harmonic Generation, Piezoelectricity and Pyroelectricity. Materials 2023, 16, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, A.; Lavrov, S.; Kudryavtsev, A.; Khatchatouriants, A.; Rosenberg, Y.; Mishina, E.; Rosenman, G. Nonlinear optical bioinspired peptide nanostructures. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2013, 1, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, P.; Maity, S.; Maity, S.K.; Ghorai, P.K.; Haldar, D. Photo-induced charge-transfer complex formation and organogelation by a tripeptide. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 5621–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Jana, P.; Maity, S.K.; Haldar, D. Inhibition of fibril formation by tyrosine modification of diphenylalanine: crystallographic insights. Cryst. Growth. Des. 2014, 14, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dipeptide | λabs [nm] |

λemi [nm] |

|---|---|---|

| Boc-Phe-Phe | 247; 252; 258; 263 | 283; 565 [1] |

| Boc-Phe-Phe-Bz | 290; 299; 304; 308 | 369; 701 |

| Boc-Phe-Phe-Bz | Hydrodynamic Diameter [nm] | Transmittance [%] |

Polydispersity Index [%] |

Diffusion Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanospheres | 482 | 99 | 30 | 1.02 |

| Nanobelts/nanospheres | 380 | 99 | 25 | 1.28 |

| Sample | Fundamental Wave Average Power (mW) |

Signal Integration Time (ms) |

Effective Thickness (µm) | Second Harmonic Signal (Counts) |

(pm/V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBO | 0.62 | 0.1 | 35 | 6.5x106 | 2.0 |

| Boc-Phe-Phe-Bz | 62 | 20 | 0.20 | 5.7x104 | 0.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).