1. Introduction

The treatment methods of PI mainly include conservative dressing change, surgical debridement, negative pressure therapy, platelet and growth factor application, etc [

1]. However, due to impaired cell function and the lack of bioactive factors around the wound, these traditional therapies are not effective in promoting wound healing and blood vessel formation [

2]. Due to the limitations of various treatment modalities, the treatment of PI remains a challenge and it is necessary to seek new therapeutic approaches.

Free radical-mediated oxidative stress causes DNA to break and lipid peroxidase to be inactivated, further hindering wound healing [

3]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by oxidative stress are one of the important factors that increase I/R injury, resulting in inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. This disrupts cytokine synthesis, delays healing, leads to extensive tissue necrosis and the development of ulcers [

4]. In addition, ROS is also essential for angiogenesis, which is a key link in the wound healing process [

5]. Therefore, the search for effective regulation of oxidative stress treatment has become a research hotspot. Recent studies indicate that P38MAPK/NFκB signaling pathway can inhibit oxidative stress injury and inflammatory infiltration, and then promote PI healing and angiogenesis after skin I/R [

6]. P38MAPK is a signal transduction molecule that exists in cells and is mainly involved in cell response to stress stimuli. When ROS levels rise in vivo, ROS can modify protein kinases located on the P38MAPK signaling pathway, change their activity state, and then activate the P38MAPK signaling pathway, triggering a series of stress responses in cells, including inflammation, cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [

7].

PRP is used to repair and rebuild wounds by activating growth factors released after the treatment. PRP is safe and has been in use since the 1970s, It has great application prospect in the field of biomedicine [

8,

9]. GO and Alg gels are two kinds of nanomaterials and natural polymer materials with good biocompatibility and drug transport capacity. When they are used together, drug carriers with excellent biological activity and therapeutic function can be prepared [

10]. Studies have shown that hydrogels containing PRP and Alg help human cells proliferate [

11]. Studies have proved that hydrogels containing PRP and oxidized alginate can promote the proliferation of human cells. The composite hydrogel of platelet-rich plasma fibrin matrix and alginate can promote wound healing in diabetic mice [

12]. Other studies have proved that GO can improve the physical properties of biomaterials and promote tissue repair. PRP gels with different concentrations of graphene oxide can promote bone tear healing and supraspinatus tendon reconstruction in rabbit models [

13]. However, there are no relevant studies on PRP supported by GO/Alg gel. We have explored the safety and feasibility of GO/Alg/PRP before [

9,

14]. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of GO/Alg gel-loaded PRP on mice skin I/R PI and human keratinocyte (HaCaT) cells in vitro, and to explore the relationship between PRP and ROS and p38MAPK/NF-κB pathway.

4. Materials and Methods

According to our experimental design, 8 weeks old healthy male BALB/c mice (25~30g) were selected, and all the animals were kept in standard laboratory conditions, eating and drinking freely. Animal care and experimental procedures are approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University and Weihai Municipal Hospital and comply with all applicable institutional and governmental regulations regarding the ethical use of animals. Strictly follow the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

4.1. Preparation of PRP

PRP was separated by secondary centrifugation. Male BALB/c mice weighing 25~30g were selected for the preparation of PRP. They were successfully anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate (Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., LTD., China). Peripheral blood was then extracted from the mice and placed in an anticoagulant tube containing 3.2% sodium citrate (Peripheral blood: sodium citrate =10: 1). The samples were thoroughly mixed to prevent blood clotting. Part of the sample was analyzed within 1 hour using an automatic cell counting system to detect the whole blood platelet concentration. The whole blood was put into a centrifuge (Hunan Xiangyi Laboratory Instrument Development Co., LTD., China) for the first centrifugation (centrifugation parameter was 2000rmp, 15 minutes). After centrifugation, the whole blood was divided into three layers, the upper layer contained most platelets and plasma, the bottom layer was red blood cell layer, and the middle layer (buffer) contained white blood cells and platelets. Platelets are mainly found in the upper and middle layers. The upper layer and part of the middle layer were slowly transferred to a new aseptic centrifuge tube, and a second centrifuge was performed after leveling (centrifuge parameter was 3000rmp, 10 minutes). The upper 2/3 was platelet-poor plasma (PPP), in which the platelet content was low, and the lower 1/3 was PRP. Discard the upper 2/3 of the PPP and gently shake the centrifugal tube to obtain the final PRP. The PRP prepared using this method obtained a platelet concentration approximately 6 times higher than the baseline concentration.

4.2. Preparation of GO / Alg

An appropriate amount of GO powder (Shenzhen Guosen Linghang Technology Co., Ltd., China) was dispersed in sterilized distilled water with a concentration of 2 mg/ml. The dispersion was then placed in an ultrasonic washer (Ningbo Xinzhi Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) at room temperature and evenly dispersed for 2 hours. An appropriate amount of Alg powder (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China) was added to the GO dispersion (3%wt), stirred well, and left at room temperature for later use.

4.3. Preparation of PRP Gel and Activation of PRP

Fresh PRP was evenly mixed with 2000U thrombin powder and 5ml 10% calcium gluconate solution at a ratio of 10:1. The mixture was shaken evenly and condensed into a gelatinous form after 3-5 minutes. After allowing it to stand for 2 hours at 37°C, PRP was fully activated. The activated PRP supernatant was placed in a centrifuge at 4°C for a gradient centrifuge at 1000rpm for 20 minutes. The underlying debris was discarded, and the supernatant was extracted and placed in a new sterile tube. In PRP activation, Platelet Rich Plasma Activation Supernatant (PRP-AS) is preserved in the refrigerator at -80°C for follow-up experiments.

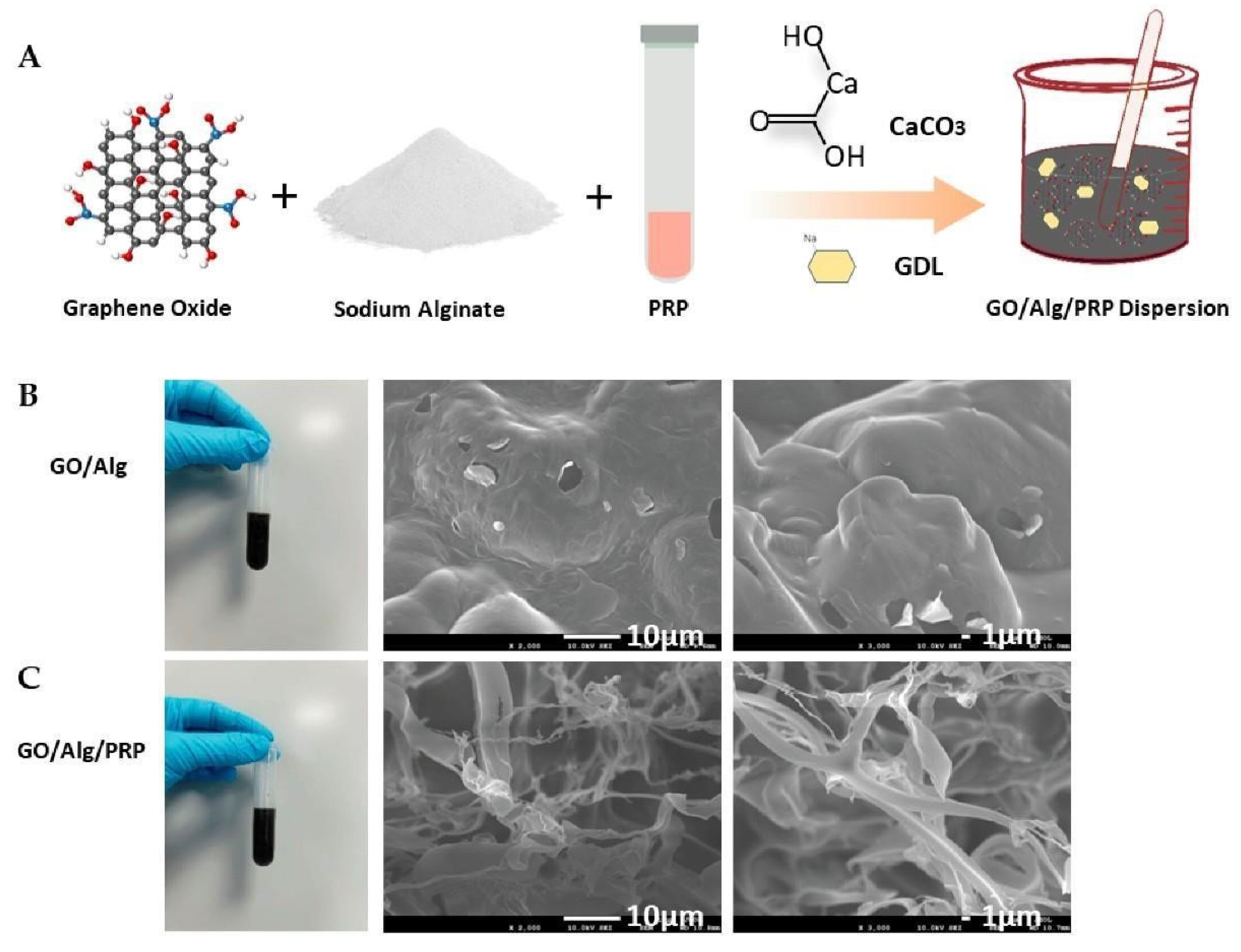

4.4. Preparation of GO/Alg and GO/Alg/PRP Gel

The GO / Alg and PRP(or phosphate buffer saline) were mixed evenly with the ratio of 1:2 to obtain GO/Alg/PRP and GO/Alg homogeneous solutions. Calcium carbonate powder (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China) and glucose-delta-lactone (GDL) powder (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China) were weighed and added into the above two mixed solutions respectively to prepare a uniform solution with a mass concentration of 0.4% calcium carbonate and a molar ratio of GDL powder to calcium carbonate of 2.65.After shaking and mixing thoroughly, allow the mixture to stand until a gel forms to obtain GO/Alg/PRP gel and GO/Alg gel.

4.5. Gel Lyophilization and Electron Microscopy Observation

GO/Alg/PRP and GO/Alg gels were prepared according to method 4.4. They were then divided into sterile EP tubes and left at room temperature for 1 hour. Samples with good shape were taken and frozen in a refrigerator at -80℃ for 24 hours. The frozen samples were then removed and placed in a vacuum freeze dryer (-88°C, 0.011 kPa, Labconco Co., US) for 24 hours to obtain fluffy GO/Alg/PRP and GO/Alg freeze-dried samples. The middle part of the freeze-dried sample with good shape was sharply cut and treated with vacuum gold spraying. The microstructure of the sample after goldplating was observed by Scanning Electron Microscopy.

4.6. Cells

HFF - 1, HaCaT and HUVEC were Purchased from Wuhan Punosai Life Technology Co., LTD. (Wuhan, China), The cells were stored in DMEM medium containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (Beijing Biogas Biotechnology Co., LTD., China) and cultured in a 5%CO2 environment at 37℃.

4.7. Cells Culture

H2O2 is a highly active compound that can induce cell damage. H2O2-induced oxidation models have been widely used to study cellular responses to oxidative stress [

40]. HFF-1, HaCaT

, and HUVEC cells were cultured to a concentration of 1×10

5 cells/mL, and after 24 hours of stabilization, oxidative stress was induced by treating the cells with H2O2 at 37℃ and 5% CO2 for 12 hours. Subsequently, gels containing PBS, GO/Alg, PRP, and GO/Alg/PRP were added to the cells, creating the model group, GO/Alg group, PRP group, and GO/Alg/PRP group. In addition, cells without H2O2 intervention were set as the control group, and PBS was added. The above 5 groups of cells were stored in the incubator for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cells were collected using a mechanical method combined with a washing method, and the relevant experiments were carried out.

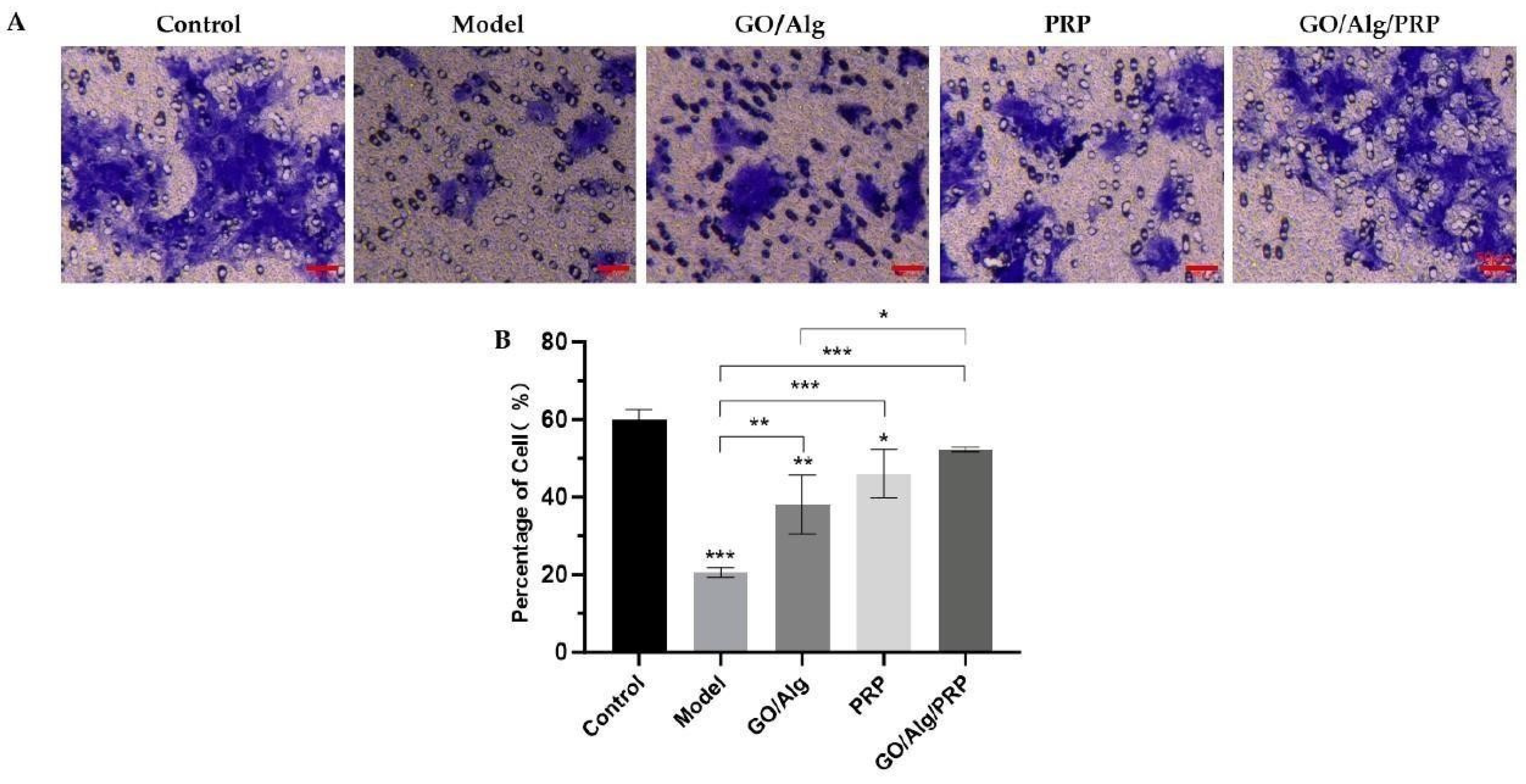

4.8. Transwell Assay

Transwell Cell (Beijing Lange Technology Co., LTD., China) was irradiated with ultraviolet light for 30 minutes under aseptic operation and operated in a 24-well plate. 5 groups of HFF-1 cells prepared in 4.7 were removed, and the cells were digested respectively and re-suspended with serum-free medium to obtain HFF-1 cell suspension with a concentration of 2 x 10^5 cells/ml. A 100µL cell suspension was added to the upper chamber of the Transwell chamber, and 600µL of serum medium was added to the lower chamber of the Transwell chamber. After incubating for 24 hours, the Transwell chamber was washed with PBS. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membrane was immersed in 70% methanol to fix the cells, and then the cells were stained with crystal violet solution. Finally, we used an inverted fluorescence microscope to obtain the final results, which were taken for quantitative analysis using the ImageJ software.

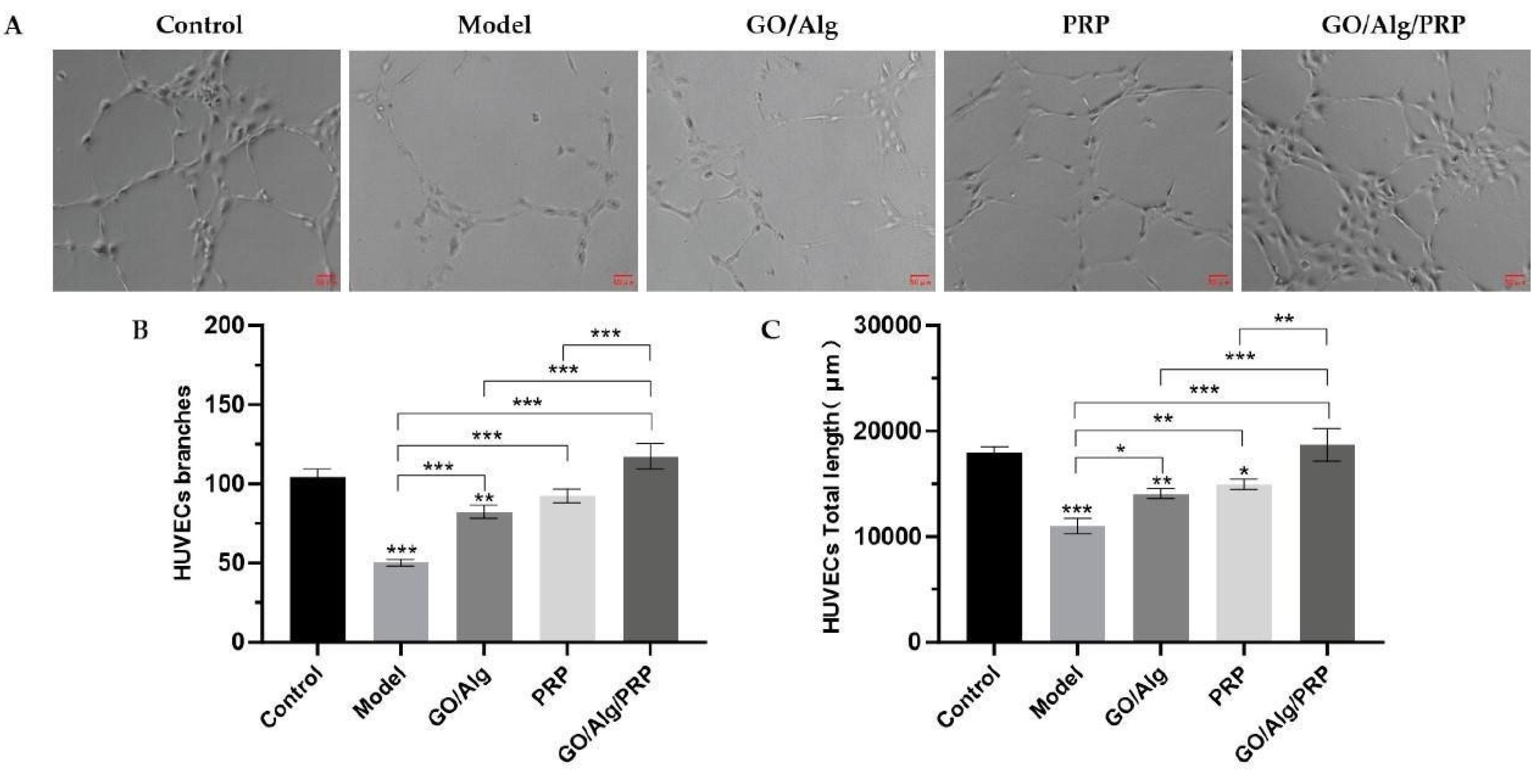

4.9. Tube Formation Assay

The day prior to the experiment, Matrigel was stored in an ice box and then transferred to a refrigerator set at 4℃. The adhesive was allowed to gradually thaw overnight. Before the experiment, Matrigel was kept in the ice box at all times. Matrigel is mixed with a pre-cooled gun head and worked on ice. The 96-well plate and the gun head were pre-cooled in advance, and 50 µL of matrix glue was added to each hole to avoid bubbles. The 5 groups of HUVEC cells prepared in 4.7 were placed in an incubator at 37°C for 45 minutes to 1 hour. When the HUVEC cells reached 70 to 80% confluence, they were digested and re-suspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS. The cells were then counted and 50µL of the re-suspension was added to each well at a concentration of 30,000 cells/well. This process was repeated for three wells. After incubation at 37℃, blood vessel formation was visible 4 hours later. After taking photos, we performed quantitative analysis using ImageJ software.

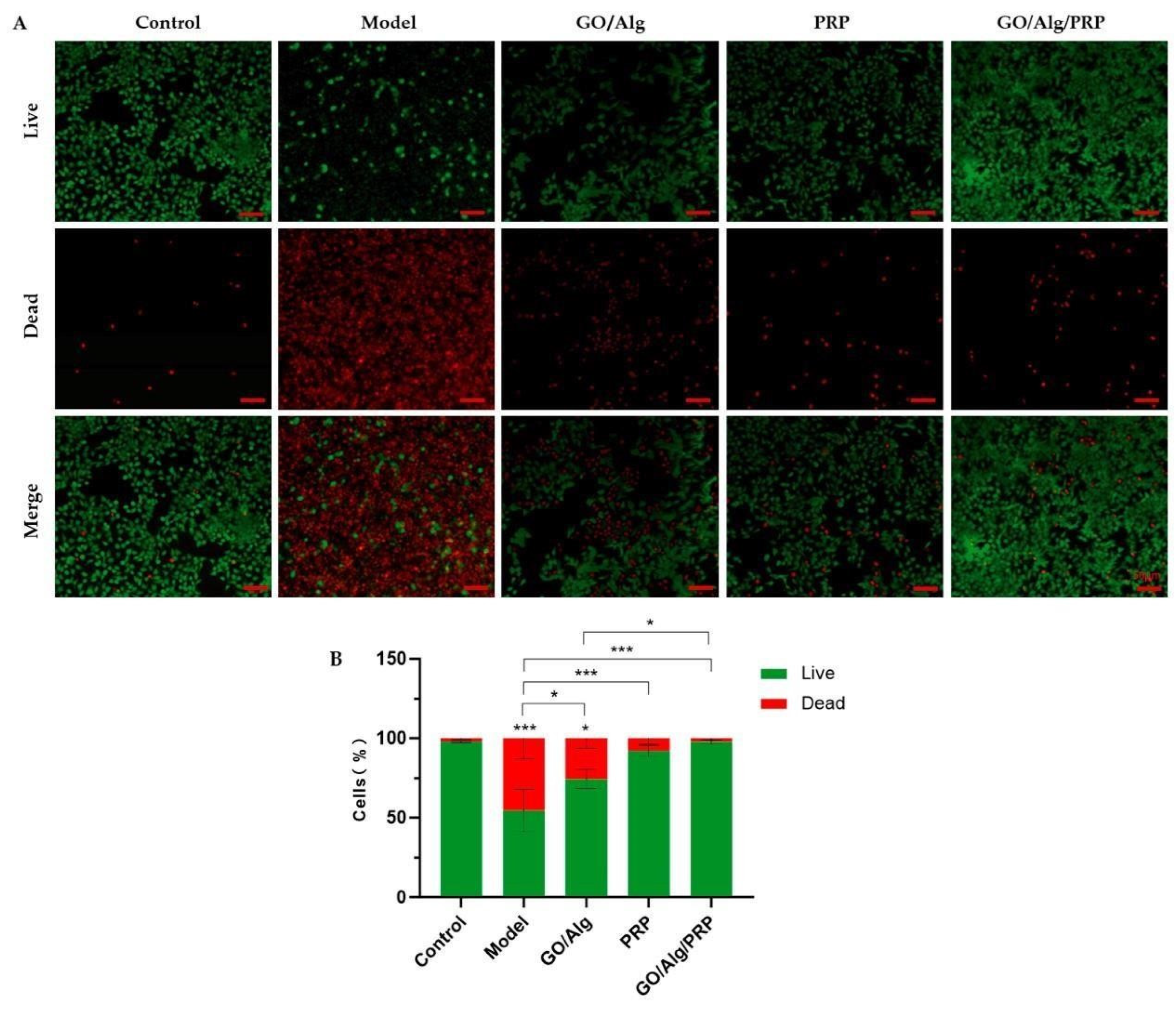

4.10. Live-Dead Cell Staining

The cell viability of HaCaT keratinocytes was studied by live/dead experiments. The five groups of cells prepared in

Section 4.7 were stained with the live/dead detection kit (Invitrogen R37601) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Images were taken with Olympus fluorescence microscope (FV300), and the results were further analyzed with Image-J software.

4.11. Flow Cytometry Analysis

The ROS content of HaCaT oxidative stress cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. DCFH-DA (

Solarbio, Beijing) was diluted with serum-free medium at 1:1000 ratio. The final concentration is 10 mmol/L. The 5 groups of cells prepared by method 4.7 above were collected and suspended in diluted DCFH-DA at a cell concentration of 1 x 10^6 - 10^7 cells/mL, and incubated in a cell incubator at 37°C for 20 minutes. Invert and mix every 3-5 minutes so that the probe is in full contact with the cells. The cells were washed with serum-free cell culture medium 5 times for 10 minutes each time to fully remove the DCFH-DA that did not enter the cells. Intracellular ROS levels were measured by flow cytometry [

41].

4.12. Mice

Fifty healthy male BALB/c mice aged 8 weeks, weighing 25~30g, were purchased from Jinan Pengyue Experimental Animal Breeding Co., LTD.(Jinan, China), and placed under standard laboratory conditions(Temperature :25℃±2℃, relative humidity :55%, light period 12h/ dark period 12h). The mice ate and drank freely and acclimated for 1 week before the experiment. The mouse stress injury model was established by pressurizing tissue damage with magnets. The experiments were divided into control group, model group, GO/Alg group, PRP group and GO/Alg/PRP group(n=10). Animal experiments are approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Qilu Medical College of Shandong University, and all experiments involving the use of animals are conducted in accordance with China’s Animal Management Regulations. At the end of the experiment, the mice were euthanized by 30% ventricular gas /min CO2 asphyxia.

4.13. PI Mouse model

The PI model with 40 experimental mice was established using the method reported by Stadler et al. [

42]. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane by Rodent Anesthesia Machine Gas Anesthesia (

ABS Full Anesthesia Machine, Louisville, KY, USA), and drug concentrations in the anesthesia were approximately 2.5%. The back hair of the mice was scraped with an electric razor and the area was cleansed with 70% alcohol. The position of the magnetic plate was marked at the same spot on each mouse. The skin was gently pulled up and placed between two circular ceramic magnetic plates (12.0mm in diameter and 5.0mm in thickness) with an average weight of 2.4g and a magnetic force of 1000g (

Magnetic Source, Castle Rock, CO, USA), The magnet was applied for three I/R cycles, with one cycle consisting of 12 h of compression, followed by 12 h of release. Animals were not immobilized, anesthetized, or treated during the I/R cycles. Forty mice underwent the same procedure and posttreatment process (

Figure 3-2a). After the surgery, the mice returned to normal activities and diet and were able to bear the weight of the fixed magnet throughout the experiment. After successful modeling, they were randomly divided into three groups: sterile saline group (model group; n = 10), GO/Alg treatment group (wounds were applied with GO/Alg gel without other active ingredients; n = 10), PRP treatment group (wounds were applied with homologous rat PRP; n = 10), GO/Alg/PRP treatment group (wounds were applied with GO/Alg/PRP gel; n = 10). In addition, 10 mice in the nonI/R group underwent the above anesthesia, removed the hair, and used a 12mm skin biopsy punch (

Acuderm, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA) to create a full-thickness wound with a diameter of 12mm at the same position as the model established on the back of other mice, named control group.

4.14. Wound Closure Analysis

The wounds were photographed on days 0, 4, 7, 10, and 14 using a digital single-lens reflex camera (D750, Nikon, Japan). A ruler next to the wounds was used to show wound size, and ImageJ software was used to estimate the wound area. These measurements were then used to calculate the percentage of wound closure as follows: (area of original wound - area of actual wound) divided by the area of original wound, multiplied by 100%.

4.15. Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

On the 14th day of the experiment, the mice were euthanized, and the wound tissues were respectively stained with HE, Masson, vWF, α-sma, CD31 and VEGF-A immunohistochemistry. Tissue specimens were immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (

Shanghai McLean Biochemical Co., LTD., China) for 48 hours after removal. And then

, dehydration, embedding

, and sectioning (performed by Hua Yong from China using Leica RM2265) were conducted for follow-up inspection [

43]. Three pathologists utilized Image J to quantitatively analyze the levels of collagen and blood vessels.

4.16. ELISA

Cells: The 5 groups of cells prepared in 4.7 above were added to the cell culture medium for culture. The cell supernatant was collected when the cells grew to the required state. Tissue: Mouse skin tissue was extracted. 1.5mL buffer was added per gram of tissue, and then ground into homogenate. The homogenate was transferred to a 1.5mL centrifuge tube and spun at 1300rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes to obtain the supernatant. The obtained supernatant was then analyzed using the ELISA kit instructions to determine the levels of MDA and SOD in tissues and cells. This analysis helped assess the extent of oxidative stress and antioxidant capacity in the cells.

4.17. Western Blot Analysis

Cells: Preparation of each group of HaCaT cells: 100 µg of protein was extracted from the abovementioned 4.7 oxidative stress in the cell extract. The same amount of protein was processed using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Tissue: Cells and tissues were pyrolyzed using radioimmunity precipitation (RIPA) buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China). The same amount of protein was processed using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking the above substances with 5% skim milk in PBS for 1hour, specific primary antibodies were used for detection. These included TGFβ (11000), p-p38MAPK (11000), p38MAPK (11000), p-NF-κB-p65 (11000), NF-κB-p65 (11000), p-IκBα (11000), IκBα (1:1000), and GAPDH (11000), all sourced from Santa Cruz Biotechnology in Santa Cruz, CA. The incubation took place at 4°C for 18 hours, followed by a 1hour incubation with horseradish peroxidase coupling. Subsequently, the membrane was rinsed with tris buffered saline water and the peroxide-labeled Protein bands labeled with peroxidase were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and band imaging was carried out by using Sense-Q2000 (Lugencico., Ltd., Bucheon, Korea), and the results were further analyzed by using ImageJ software.

4.18. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.0 was used to statistically analyze the experimental data. All quantitative results are expressed as mean ± SD, and unpaired two-tailed Student t-test was used for statistical analysis. Differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posttest.

Figure 1.

Preparation diagram of GO/Alg/PRP (A). General appearance and Scanning Electron Microscopy images of GO/Alg(B) and GO/Alg/PRP(C) and their porous structures at specified magnification scales.

Figure 1.

Preparation diagram of GO/Alg/PRP (A). General appearance and Scanning Electron Microscopy images of GO/Alg(B) and GO/Alg/PRP(C) and their porous structures at specified magnification scales.

Figure 2.

Fluorescent photos of different groups of living and dead cells were stained. The green channel represents the living cells, while the red channel represents the dead cells, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm (A). Quantitative comparison of the percentage of living/dead cells can be observed in the image (B). All data are statistically significant(* p < 0.05,** p < 0.01,*** p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Fluorescent photos of different groups of living and dead cells were stained. The green channel represents the living cells, while the red channel represents the dead cells, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm (A). Quantitative comparison of the percentage of living/dead cells can be observed in the image (B). All data are statistically significant(* p < 0.05,** p < 0.01,*** p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Transwell assay of HFF-1 cells in different groups, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm (A). Additionally, quantitative analysis of HFF-1 cells was performed(B). All data are statistically significant(* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Transwell assay of HFF-1 cells in different groups, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm (A). Additionally, quantitative analysis of HFF-1 cells was performed(B). All data are statistically significant(* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Effect of materials in each group on the angiogenesis of HUVEC cells induced by oxidation. Photos of the angiogenesis of HUVEC cells induced by oxidative stress in each group are presented, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm (A). The number of vascular branches induced by oxidative stress in HUVEC cells in each group(B). Total vascular length after intervention of HUVEC cells induced by oxidative stress in each group(C). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Effect of materials in each group on the angiogenesis of HUVEC cells induced by oxidation. Photos of the angiogenesis of HUVEC cells induced by oxidative stress in each group are presented, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm (A). The number of vascular branches induced by oxidative stress in HUVEC cells in each group(B). Total vascular length after intervention of HUVEC cells induced by oxidative stress in each group(C). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

The degree of lipid peroxidation damage to HaCaT cells induced by oxidation in each group. The content of intracellular ROS production in HaCaT cells induced by oxidative stress was interfered by materials in each group (A). The content of MDA in HaCaT cells induced by oxidative stress in each group (B). The content of SOD in HaCaT cells induced by oxidative stress in each group(C). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

The degree of lipid peroxidation damage to HaCaT cells induced by oxidation in each group. The content of intracellular ROS production in HaCaT cells induced by oxidative stress was interfered by materials in each group (A). The content of MDA in HaCaT cells induced by oxidative stress in each group (B). The content of SOD in HaCaT cells induced by oxidative stress in each group(C). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Western blotting detected the expression of TGF-β, p-p38MAPK, p38MAPK, p-NF-κB-p65, NF-κB-p65, IκBα, and p-IκBα proteins in cells(A). Additionally, the relative ratio of TGF-β after intervention in each group is presented (B). The relative ratio of p-p38MAPK/p38MAPK after material intervention was measured in each group (C), and the relative ratio of p-NF-κB-p65/NF-κB-p65 was determined for each material after intervention (D). The relative ratio of p-IκBα/IκBα for each group after the intervention (E). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Western blotting detected the expression of TGF-β, p-p38MAPK, p38MAPK, p-NF-κB-p65, NF-κB-p65, IκBα, and p-IκBα proteins in cells(A). Additionally, the relative ratio of TGF-β after intervention in each group is presented (B). The relative ratio of p-p38MAPK/p38MAPK after material intervention was measured in each group (C), and the relative ratio of p-NF-κB-p65/NF-κB-p65 was determined for each material after intervention (D). The relative ratio of p-IκBα/IκBα for each group after the intervention (E). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

The treatment of each group of materials promoted wound healing in mouse full-layer skin wound model. Representative images of full-layer wounds at 0, 4, 7, 10, and 14 days after treatment with materials in each group are shown. Scale=1.6 cm(A). Quantification of wound healing. The wound size is expressed as a percentage relative to the initial wound area(B). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 7.

The treatment of each group of materials promoted wound healing in mouse full-layer skin wound model. Representative images of full-layer wounds at 0, 4, 7, 10, and 14 days after treatment with materials in each group are shown. Scale=1.6 cm(A). Quantification of wound healing. The wound size is expressed as a percentage relative to the initial wound area(B). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

The application of materials in each group enhanced tissue reepithelialization and collagen deposition. The representative images of H&E staining of fully reepithelialized wounds on day 14 post-injury are shown in (A). Masson-stained representative images of fully reepithelialized wounds on day 14 post-injury (B), and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm. Quantitative measurement of epidermal thickness (C). Quantitative collagen content (D). All data are statistically significant(* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 ).

Figure 8.

The application of materials in each group enhanced tissue reepithelialization and collagen deposition. The representative images of H&E staining of fully reepithelialized wounds on day 14 post-injury are shown in (A). Masson-stained representative images of fully reepithelialized wounds on day 14 post-injury (B), and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 50µm. Quantitative measurement of epidermal thickness (C). Quantitative collagen content (D). All data are statistically significant(* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 ).

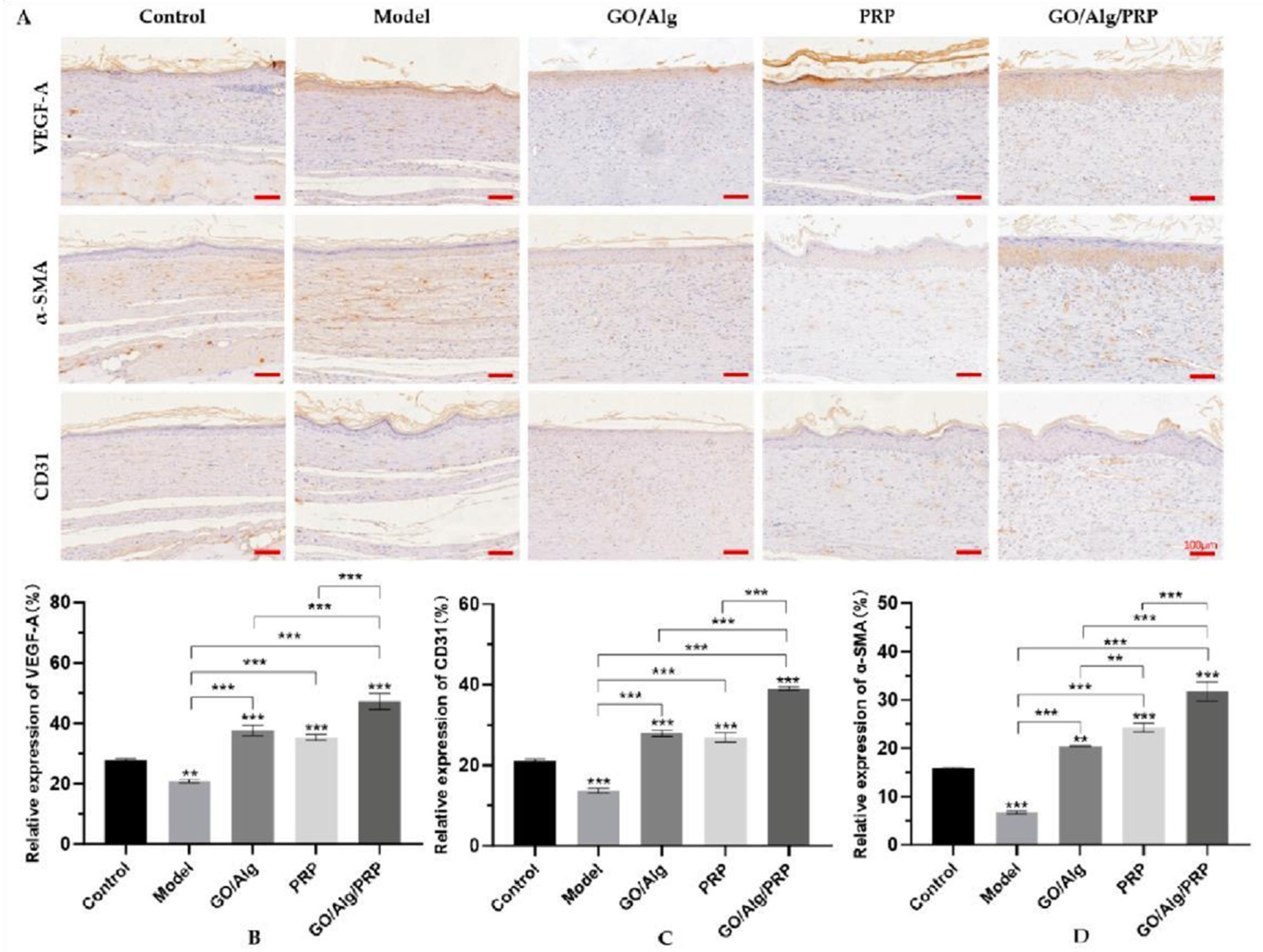

Figure 9.

The levels of VEGF, CD31 and α-SMA in vascular endothelial cells were detected by immunohistochemistry. Images of immunohistochemical staining results are presented in the figure, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 100µm (A). expression rates of VEGF, CD31, and α-SMA in vascular endothelial cells, respectively(B-D). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 9.

The levels of VEGF, CD31 and α-SMA in vascular endothelial cells were detected by immunohistochemistry. Images of immunohistochemical staining results are presented in the figure, and the scale in the lower right corner indicates that the scale is 100µm (A). expression rates of VEGF, CD31, and α-SMA in vascular endothelial cells, respectively(B-D). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

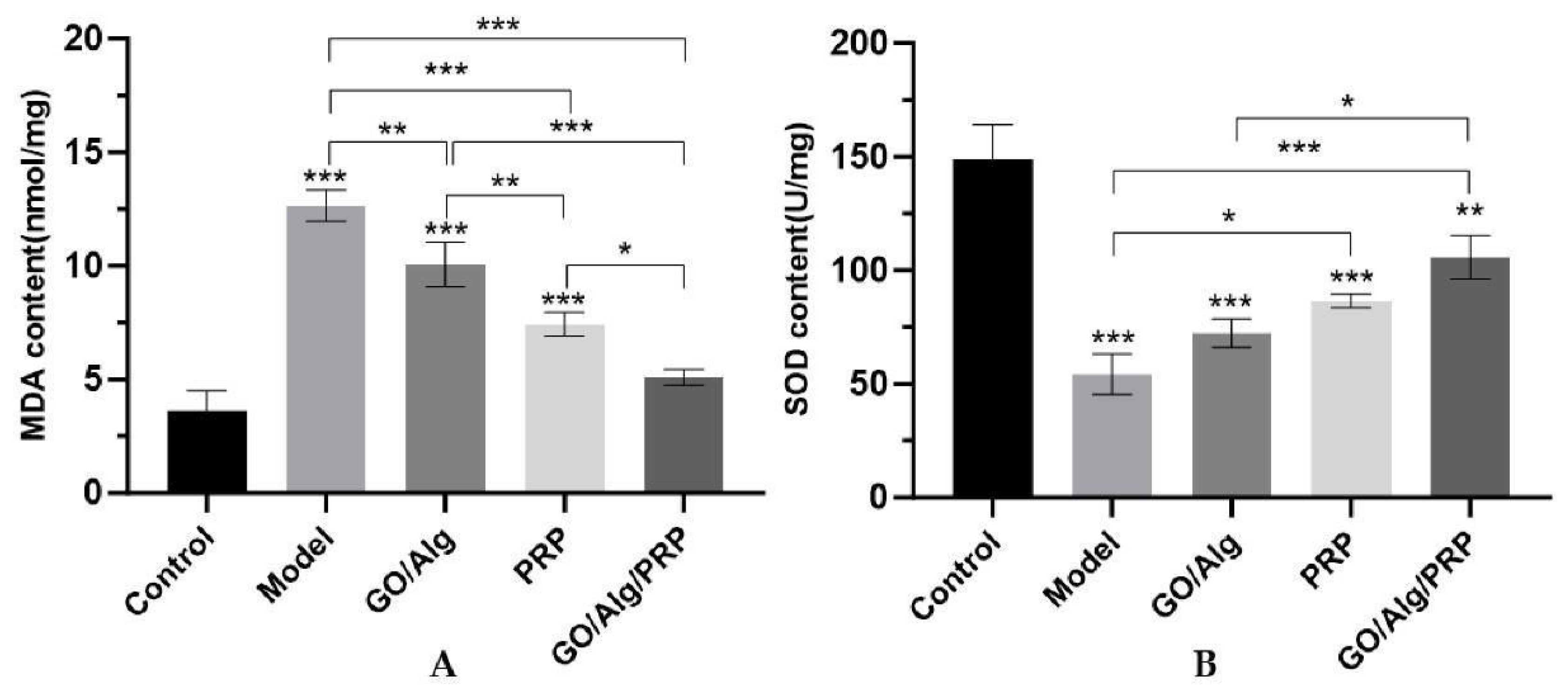

Figure 10.

The content of MDA in tissue induced by oxidative stress in each group (A). The content of SOD in tissue induced by oxidative stress in each group(B). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 10.

The content of MDA in tissue induced by oxidative stress in each group (A). The content of SOD in tissue induced by oxidative stress in each group(B). All data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

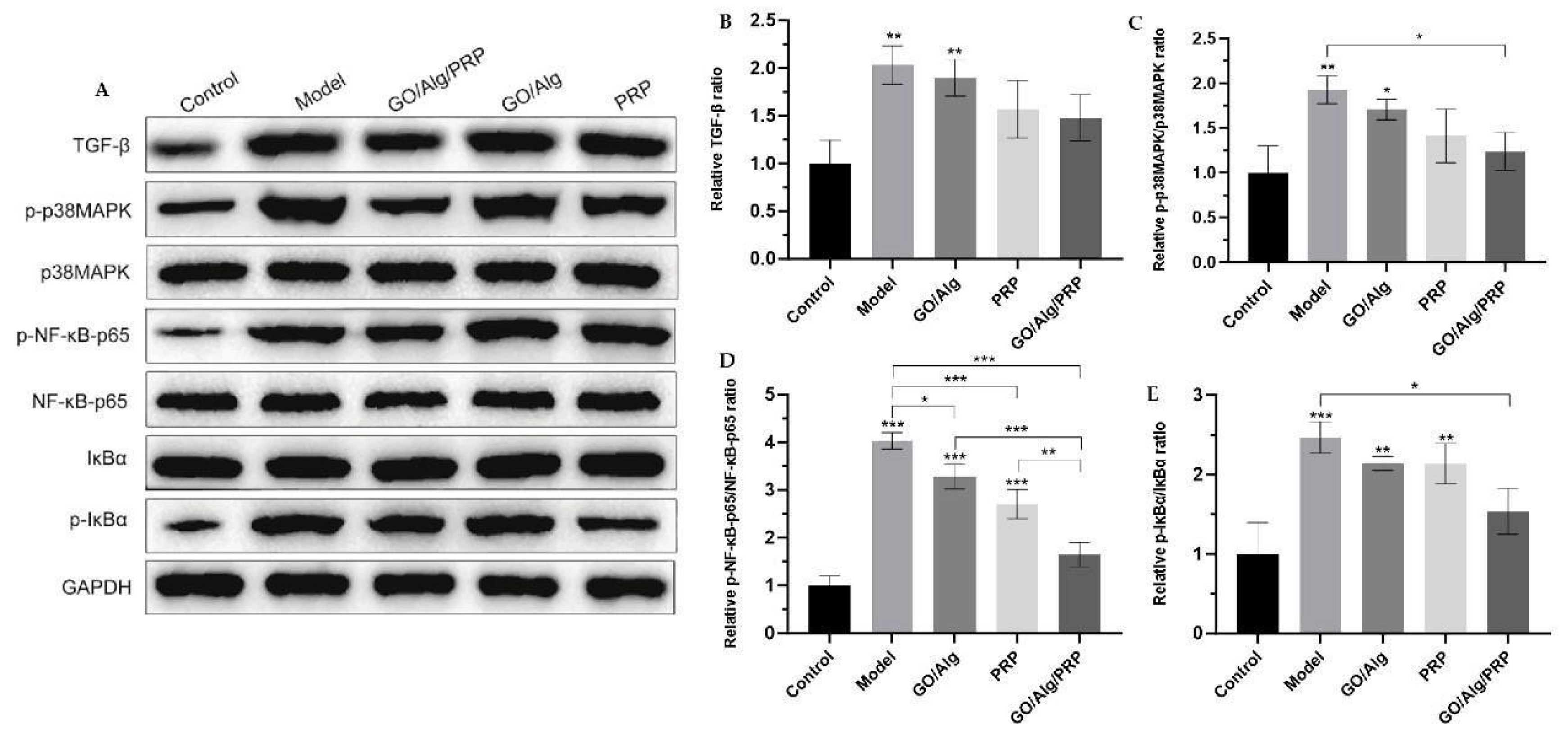

Figure 11.

Western blotting was used to detect the expression of TGF-β, p-p38MAPK, p38MAPK, p-NF-κB-p65, NF-κB-p65, IκBα, and p-IκBα proteins in tissues (A). Additionally, the relative ratio of TGF-β after intervention in each group was determined (B). The relative ratio of p-p38MAPK/p38MAPK after material intervention was measured in each group (C). Additionally, the relative ratio of p-NF-κB-p65/NF-κB-p65 was determined for each material after intervention (D). The relative ratio of p-IκBα/IκBα for each group after intervention (E) has been determined. All the data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 11.

Western blotting was used to detect the expression of TGF-β, p-p38MAPK, p38MAPK, p-NF-κB-p65, NF-κB-p65, IκBα, and p-IκBα proteins in tissues (A). Additionally, the relative ratio of TGF-β after intervention in each group was determined (B). The relative ratio of p-p38MAPK/p38MAPK after material intervention was measured in each group (C). Additionally, the relative ratio of p-NF-κB-p65/NF-κB-p65 was determined for each material after intervention (D). The relative ratio of p-IκBα/IκBα for each group after intervention (E) has been determined. All the data are statistically significant (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).