1. Introduction

Winter precipitation significantly disrupts daily life, affecting transportation, power grid stability, and home safety depending on its phase, duration, and intensity. Freezing rain (ZR) and freezing drizzle (ZL) are particularly destructive forms of precipitation. A notable example is the severe winter storm from January 5–9, 1998, which impacted northern New York, New England, Quebec, and Ontario. The storm caused widespread damage to homes and power infrastructure, left millions without electricity, disrupted transportation, and resulted in billions of dollars in economic losses. Tragically, it also caused several fatalities, including three in Ontario (Lott et al., 1998; DeGaetano, 2000; Gyakum and Roebber, 2001; Roebber and Gyakum, 2003). Strapp et al., (1996) previously identified the Great Lakes region near Ottawa and Newfoundland near St. John’s as areas with a high frequency of freezing precipitation events. Climatological studies have also highlighted significant occurrences along the St. Lawrence-Ottawa River Valleys and in the Maritime Provinces (Stuart and Isaac, 1999; Cortinas et al., 2004). In its solid form, precipitation can severely disrupt air and ground transportation by reducing visibility, complicating road conditions, and making aircraft landing and takeoff operations more challenging (Boudala and Isaac, 2009).

Freezing precipitation (ZP) such as ZR and ZL occurs when supercooled drops freeze upon contacting the Earth's surface at cold temperatures (T < 0°C). Currently, two cloud microphysical mechanisms are believed to lead to the formation of supercooled drops: classical and non-classical mechanisms (Cortinas et al., 2004). The classical mechanism involves a melting layer (ML) aloft, associated with a temperature inversion, and a cold layer below that keeps the drops super-cooled until they reach the ground and freeze. In contrast, the non-classical mechanism does not require a ML. Instead, supercooled drops form through collision and coalescence processes, often resulting in ZL (Huffman and Norman 1988; Bocchieri, 1980; Rauber et al., 2000, Bernstein, 2000). The formation of ice pellets (IP) requires a melting layer (warm layer) aloft and a refreezing cold layer near the surface. Studies have shown that the incomplete melting of snowflakes in the warm layer is the main factor in producing ice pellets, with the strength and depth of the cold layer being secondary factors (Hanesiak and Stewart, 1995; Zerr, 1997).

Forecasting precipitation types remains one of the most challenging problems in meteorology (Hewson et al., 2018; Ralph et al., 2005; Tessendorf et al., 2021), especially for non-classical ZP. Predicting supercooled and mixed-phase clouds is particularly complex, as it requires a detailed understanding of cloud microphysical and dynamical processes and their interactions with atmospheric aerosols and radiation. Even the most sophisticated numerical weather prediction (NWP) models are prone to significant errors due to small biases in temperature profiles (e.g., Thériault et al., 2010). Some models have also shown that errors in predicting the precipitation phase are largely influenced by surface temperature biases (Ikeda et al., 2017). Most nowcasting and forecasting algorithms for diagnosing freezing precipitation are based on classical freezing mechanisms, which require the presence of freezing layers aloft and subfreezing temperatures at the surface (e.g., Bourgouin, 2000; Baldwin et al., 1994).

Measuring precipitation and identifying the associated phase and type of falling particles are crucial for the development and validation of NWP models, as well as for improving remote sensing data retrieval algorithms. Aircraft and surface-based studies indicate that nonclassical ZP typically occurs at colder surface temperatures (-10°C < T < 0°C) as compared to the classical range (-6°C < T < 0°C) (Isaac et al., 1998). Cortinas et al., (2004) analyzed hourly data to derive the frequency distributions of ZR, ZL, and IP as a function of temperature (-18°C < T < 4°C) and found that ZP, including IP, mostly occur near freezing temperatures. Studies of wintertime mixed-phase precipitation, including the liquid phase fraction and icing potential, have been conducted in the continental cold climate of Cold Lake, Alberta, Canada (Boudala et al., 2027; 2019). These studies indicate that present weather sensors, such as the Visala PWD22, can effectively characterize precipitation compared to traditional gauges like the Pluvio2, especially during snow events (Boudala et al., 2017). Using PARSIVEL disdrometer data, Lachapelle et al., (2024) characterized the fall velocity (V) of IP and liquid phase precipitation particles, finding that IP particles typically fall at slightly lower speeds than raindrops, consistent with other studies (Rahman and Testik, 2020).

While there have been some sporadic studies of mixed-phase precipitation using hourly METAR data to identify precipitation types, there are limited studies using high-resolution data that combines surface and aloft datasets. To gain better insights into mixed-phase precipitation, a major campaign known as the Winter Precipitation Type Research Multi-Scale Experiment (WINTRE-MIX) was conducted (Minder et al., 2023). This involved surface-based measurements at several sites in Quebec, Canada, and the US, chosen for their climatological conditions conducive to understand freezing precipitation (Minder et al., 2023; Strapp et al., 1996; Lott et al., 1998; DeGaetano, 2000; Gyakum and Roebber, 2001; Roebber and Gyakum, 2003).

This paper will use the surface-based datasets collected at the Sorel site located in Quebec, Canada. The instruments deployed at the Sorel site include the MRR, the Vaisala FD71P present weather sensor, the OTT PARSIVEL disdrometer, a single Alter shielded OTT Pluvio2 gauge, and the Vaisala WXT520 that measures temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), and wind speed (, There have been also occasional Radiosonde based measurements and high-resolution human based precipitation type reports.

This paper focuses on several key objectives: (a) Characterizing the microphysical processes of mixed-phase precipitation to enhance understanding of formation mechanisms of ZP and IP using integrated datasets from MRR, surface measurements, and Radiosonde data, with a focus on observed temperature (T), relative humidity (RH), velocity (V), and size relationships.(b) Gaining insights into the distributions of liquid and solid and mixed-phase precipitation by contrasting precipitation measurements under various meteorological conditions such as T and RH. (c) Evaluating the performance of the FD12P and PARSIVEL probes in detecting precipitation types, compared to manual reports where available. (d) Comparing measurements from the FD71P, PARSIVEL, and Pluvio 2 gauges equipped with a single Alter shield, alongside manual measurements for snow. The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 details the materials and methodologies,

Section 3 presents the results, and

Section 4 summarizes the findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area and Data

The Sorel site, located in southeastern Quebec, Canada (at 13 m ASL; 46.04 N, 73.11 W), is characterized by its proximity to the Saint Lawrence River, which surrounds the area from the west to the northeast, including St. Pierre Lake (

Figure 1). Climatically, the region is classified as continental and humid. This site was selected for the WINTRE-MIX project due to its favorable meteorological conditions for producing various types of precipitation, such as ZR, ZL, and snow (

Minder et al., 2023). The meteorological instruments were deployed in an open park area, as depicted in

Figure 2, which shows views towards the east (

Figure 2a) and south (

Figure 2b). Towards the east (

Figure 2a), there are nearby houses extending southeastwards (not shown), potentially influencing local sheltering effects. Conversely, the western and southwestern directions (

Figure 2b) are relatively open, with scattered trees further away. The instruments are enclosed within an octagonal fence to minimize wind-induced loss of falling snow. Data for this study were collected using several instruments: the Biral/Metek 24 GHz (K-band) MRR (METEK, 2017), the Vaisala FD71P present weather sensor (

Klugmann and Kauppinen, 2022), the PARSIVEL disdrometer, and a single Alter shielded (SAS) OTT Pluvio2 gauge. The Vaisala FD71P sensor provides measurements of P, PT, and visibility averaged at 1 min intervals, with outputs recorded every 5 seconds. It also includes temperature and humidity sensors for RH and T measurements. The OTT PARSIVEL disdrometer (

Boudala et al.

, 2014;

Boudala and Milbrandt, 2023) measures P, PT, V, and size distributions of precipitation particles (N(D)) at 1-min resolution. The SAS OTT Pluvio2 gauge measures P and accumulation at 1-min intervals (

Boudala and Milbrandt, 2023). The MRR provides vertical profiles of V, radar reflectivity (

), and mixed-phase ML identification (METEK, 2017). Additionally, intermittent manual measurements of snowfall were made using a Snowtube as part of research by Université de Québec à Montréal (UQAM) (

Han et al, 2022). These datasets were utilized to validate snowfall measurements from the instruments mentioned above. Human observations of PT were also recorded manually every 10-min during the project, serving as validation data for instrument-derived PTs. Precipitation comparisons were based on 10-min averaged datasets, focusing only on dates with recorded precipitation events (see

Figure 3). Detailed descriptions of the FD71P sensor and the modification of PARSIVEL data for deriving solid phase precipitation (

) by including the riming effect in the snowflake density size relationship (

Holroyd, 1971) are provided in

Appendix A. Further details about the Pluvio2, WXT520, and MRR instruments can be found elsewhere (

Boudala and Milbrandt, 2023;

Boudala et al.

, 2017; METEK, 2017).

2.2. The Meteorological Conditions of the Site During the WINTRE-MIX Project

One min averaged T, RH and 2m height

observed during precipitation events within the measurement period (Oct 2021- Mar 2022) at the Sorel site are given in

Figure 3. Temperature varied substantially from -30

oC to 10

oC and with a mean and standard deviation (SD) of -7.7

oC and 12.1

oC respectively (

Figure 3a). The RH varied from 40% to 100% with a mean value of 74% and SD of 15% respectively. The wind speed inside the fence, however, did not vary much, only occasionally reaching 10 ms

-1 and can be considered mostly calm (

Figure 3b). The mean and SD values were 1.42 ms

-1 and 1.32 ms

-1 respectively. The PT reported based on the FD71P and PARSIVEL show a variety of precipitation types including ZR, ZL, IP, ice crystals (IC), snow grains (SG), snow pellets (SP), snow (S), rain (R), and drizzle (L), R+L+S (RLS), R+L (RL), and un and C represent the unknown type and non-precipitation condition respectively (

Figure 3c). Note here that the FD71P does not report SP and the PARSIVEL does not report SG, IC, and IP. Based on visual inspection , the probes reasonably agreed detecting C, S, ZR, L and R events. It is possible also that the PARSIVEL may report IP as SP. This subject will be discussed in more detail in

Section 3.

Figure 3.

Observation of T and RH (a), wind speed (WXT520) (b), and precipitation type (PT) based on the FD71P and PARSIVEL (c). In panel (c), the symbols represent no precipitation (C), snow (S), snow pellets (SP), ice pellets (IP), snow grains (SG), ice crystals (IC), rain (R), freezing rain (ZR), freezing drizzle (ZL), the PT is not identified (UN), and R+L+S (RLS).

Figure 3.

Observation of T and RH (a), wind speed (WXT520) (b), and precipitation type (PT) based on the FD71P and PARSIVEL (c). In panel (c), the symbols represent no precipitation (C), snow (S), snow pellets (SP), ice pellets (IP), snow grains (SG), ice crystals (IC), rain (R), freezing rain (ZR), freezing drizzle (ZL), the PT is not identified (UN), and R+L+S (RLS).

3. Results

3.1. PT Manual and Instruments Comparisons

As discussed earlier there were limited manual observations of PT for a total of 11 days of data collected every 10 min during precipitation events. The human observations were reported as primary and secondary according to the occurrence of most frequent and less frequent PTs respectively. In this analysis only the primary PTs are included for validating the PT reports based on the instruments.

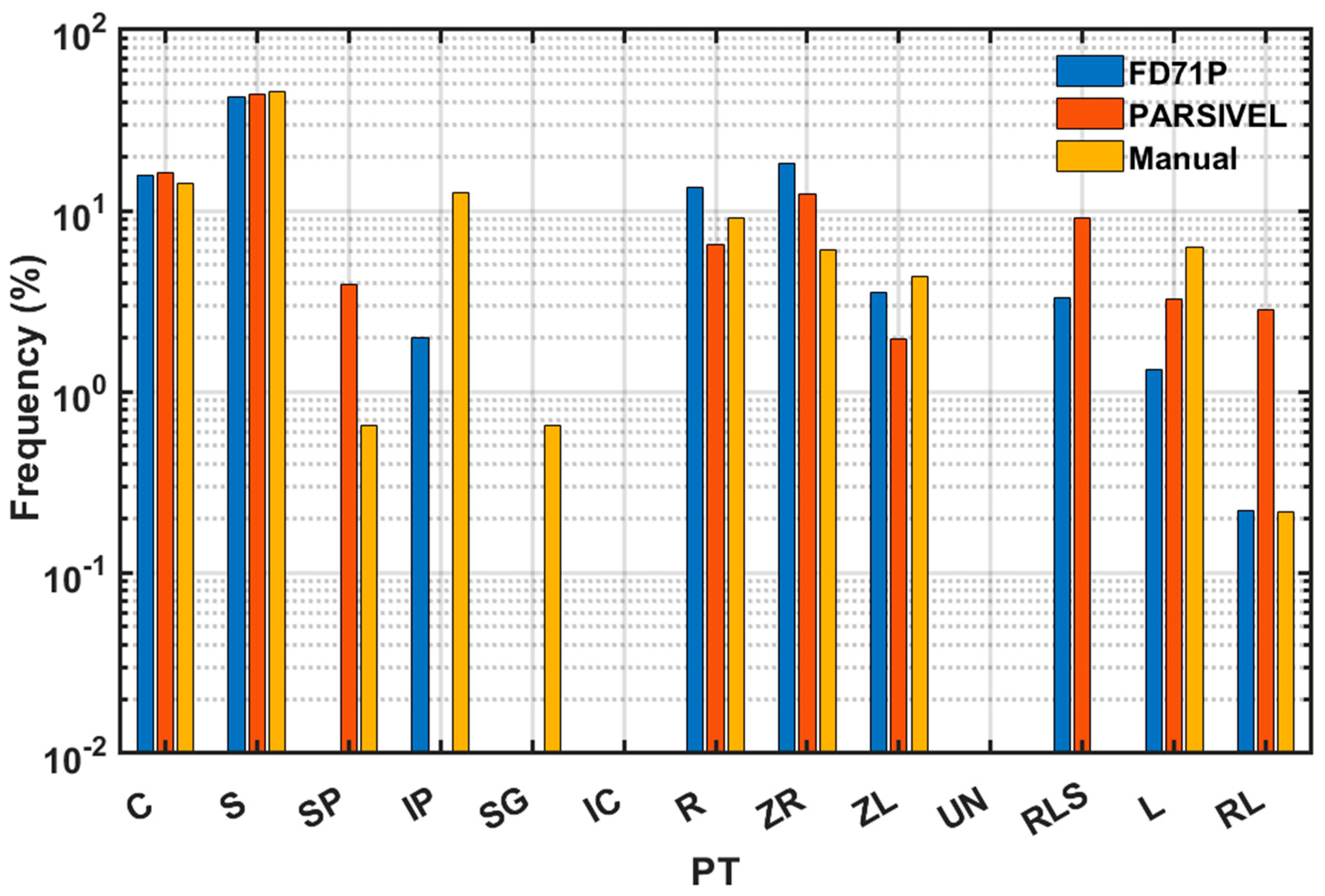

Figure 4 shows the frequency distribution of PTs for the selected dates that precipitation occurred based on the FD71P, PARSIVEL, and manual measurements. The percentage of the PTs detected during these measurements period are given in

Table 1. According to these results, both instruments reasonably agreed with the manual observation detecting no precipitation cases (C) (~15%) as compared to the manual detection of 14% which is slightly lower. This may be attributed to the higher sensitivity of the instruments as compared to the human observer. The manual detection of S (46%) represents the larger fraction of the PT events, and it is slightly underestimated by the instruments, FD71P(42.3%) and PARSIVEL (43%). The next significant PT that is manually reported was IP (12.6%), but it is significantly under detected by the FD71P (2%). The PARSIVEL does not report IP (NA). The next significant PTs manually reported were R(9%), ZR (6%), L(6.3%) and ZL (4%) and when compared to the instruments, the FD71P overestimated R(13%) and ZR(18%), underestimated L (1.3%), but agreed very well detecting ZL (4%). The PARSIVEL probe is somewhat close to the manual observation as compared to the FD71P detecting R (7%), ZR (12%) and L (3.3%), but detected lower ZL (2%) as compared to the manual observation. There were no significant manual reports for IC (0%) and SG (0.7%), mostly in agreement with the instruments. Although the datasets were limited, the results suggest that the two instruments were able to detect C and S events with reasonable accuracy. The FD71P appears to overestimate ZR and underestimate IP. Comparing the manual observation taken every 10 min and the interpolated nearest of the manual observation time against the higher resolution data collected every minute by the instruments has some uncertainties since instrument-based PT under some conditions fluctuates rapidly within a 10 min interval. More rigorous testing of these instruments using much larger datasets is required to better understand the differences reflected in this study. The other reason could be linked to the instrument algorithm used to diagnose the PT, the possible reasons related to this will be investigated in more detail in

Section 3.4.

3.2. Case Study of Mixed Precipitation on 06 March, 20022

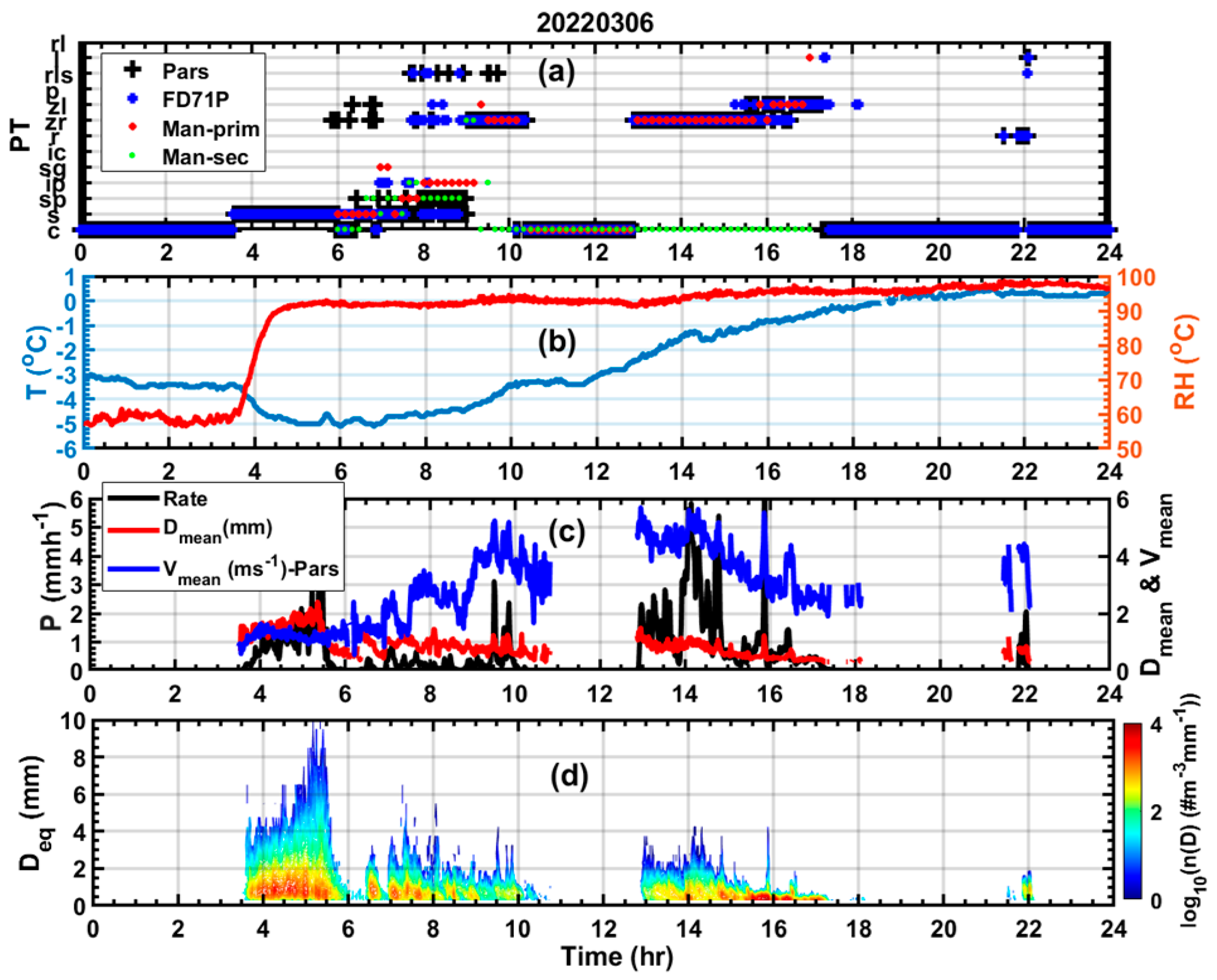

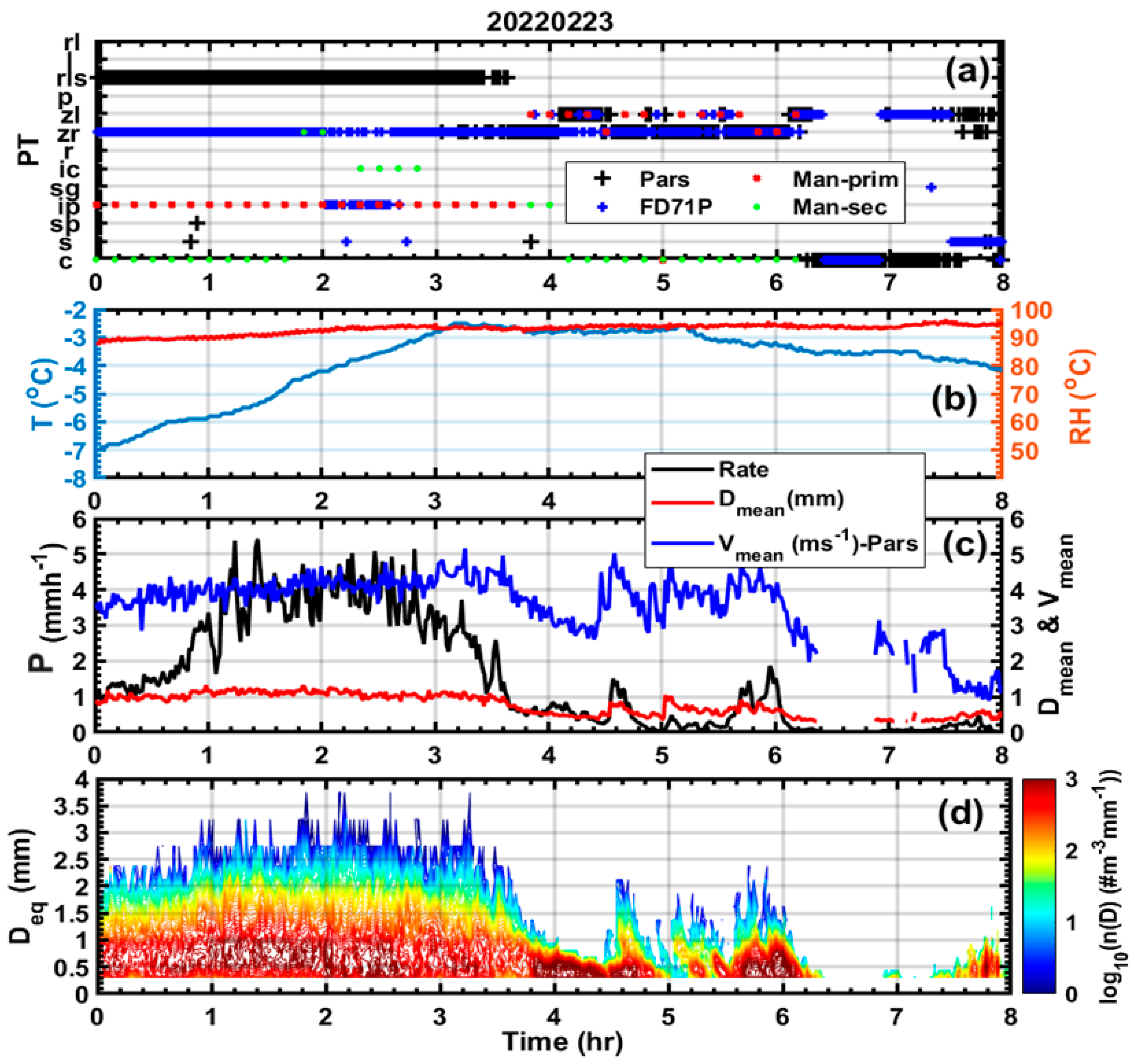

Figure 5 shows the time series on 6 March, 2022 of PT based on human observation and reported by the instruments (FD71P and PARSIVEL) (

Figure 5a), RH and T (

Figure 5b), the number weighted mean particle velocity (

), and diameter (

) calculated using the PARSIVEL Disdrometer (

Figure 5c), and particle spectra (n(D) (

Figure 5d). The human observations are made every 10 min and the instruments report PT every min. The human observer reported both the dominant or primary (Man-Prim) PTs and those that are minor or secondary (Man-sec) PTs. Both instruments have reported snow between 4 UTC and 6 UTC (

Figure 5a). During this time, the observed T and RH were near -5

and 90% and characterized by relatively enhanced precipitation intensity. The calculated

varied from 1mm to 2 mm and the values of

varies from 1

to 1.5

, the maximum diameter of the particle spectra reached close to 10 mm, but the majority of the precipitation particles were less than 2 mm in size (

Figure 5d) indicating the existence of mostly relatively smaller ice particles as diagnosed by both manual and present weather sensors (

Figure 5c). After 06:00 UTC, the surface temperature started to warm up slightly and although the

remain approximately near 1 mm, the

exhibited fluctuation from 1

to about 3

between 6 UTC and 9 UTC under light precipitation indicating a mixture of particles. The human observation mainly indicated snow with some secondary SP and SG up to near 8 UTC. The PARSIVEL probe also reported mainly snow with some minor SP which is consistent with human observation, but occasionally reported ZR and ZL which is not supported by the human observation. In this period the FD71P reported mainly snow which is consistent with the human observation with an occasional IP where the manual observation indicated SP suggesting that the FD71P may have misclassified SP as IP. Also note that between 8 UTC and 9 UTC, the human observer reported mainly IP with some minor secondary PTs of SP when the FD71P reported mainly snow and some ZR, ZL, and RLS. The human observer does not report RLS, but according to the human observation there were mainly IP with some secondary SP particle, but the FD71P reported these as ZR and snow not consistent with human observation. Between 9 UTC and 11 UTC and between 13 UTC and 16 UTC, both the human observer and the instruments reported ZR where the surface temperature warmed up from -3

oC to -1

oC, and the RH was close to 90%.

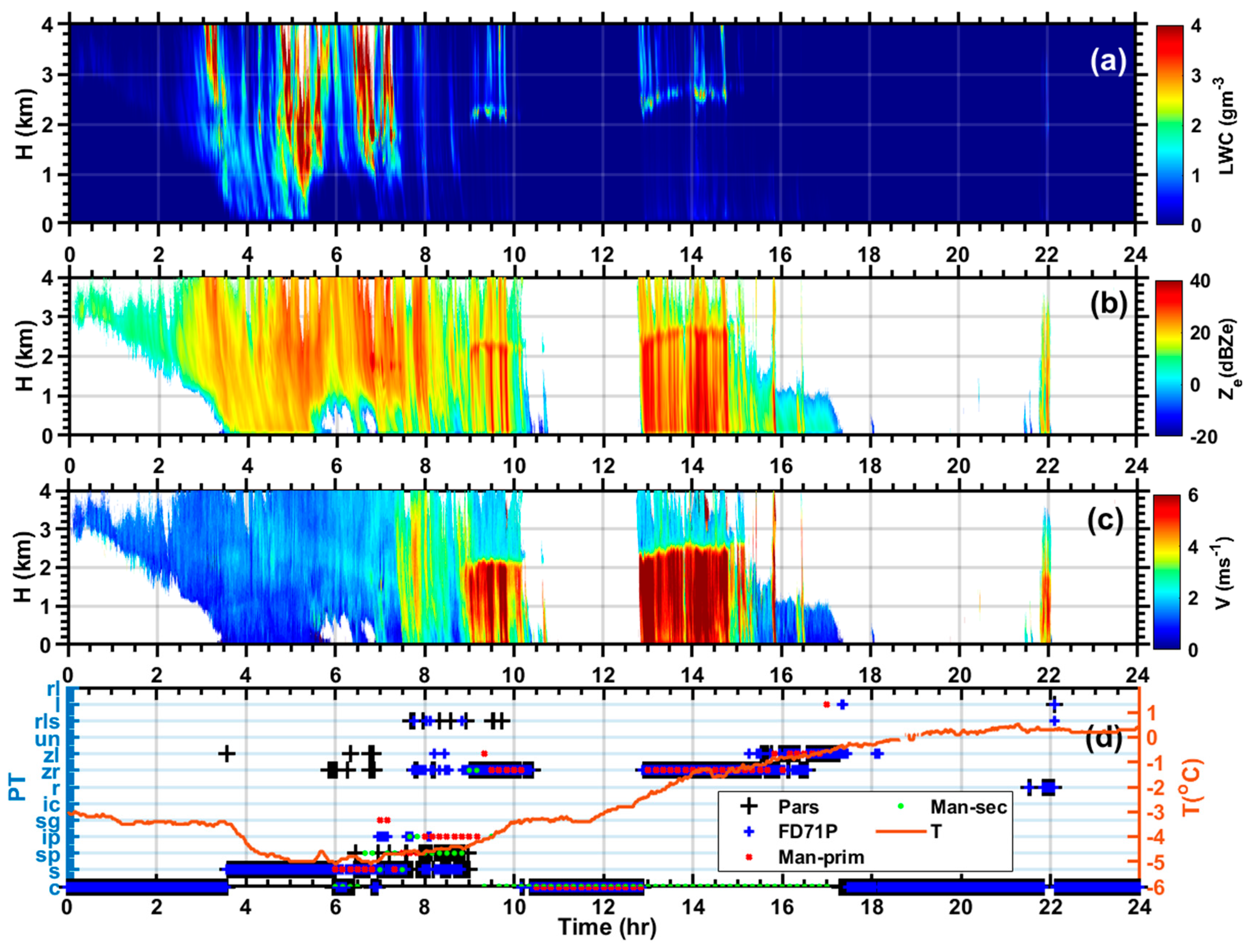

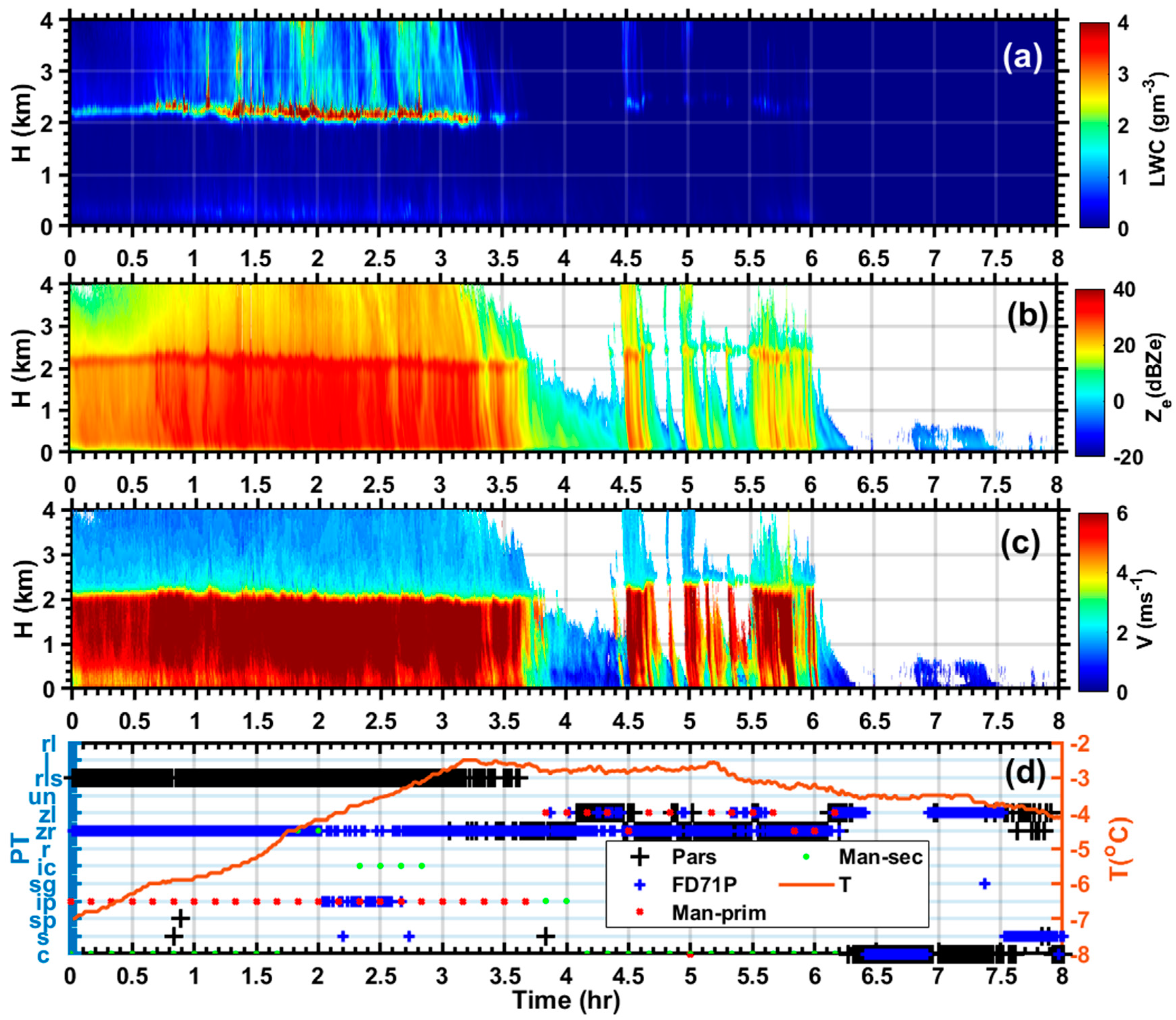

Figure 6 shows the time series of the vertical profiles of liquid water content (LWC) (

Figure 6a), radar reflectivity factor (

Figure 6b), fall velocity (

Figure 6c), and surface observation similar to

Figure 5d. As indicated in the figure, all the ZR events mentioned earlier are associated with melting layer (ML) as depicted by enhanced LWC, V and Z near 2 km and 2.5 km.

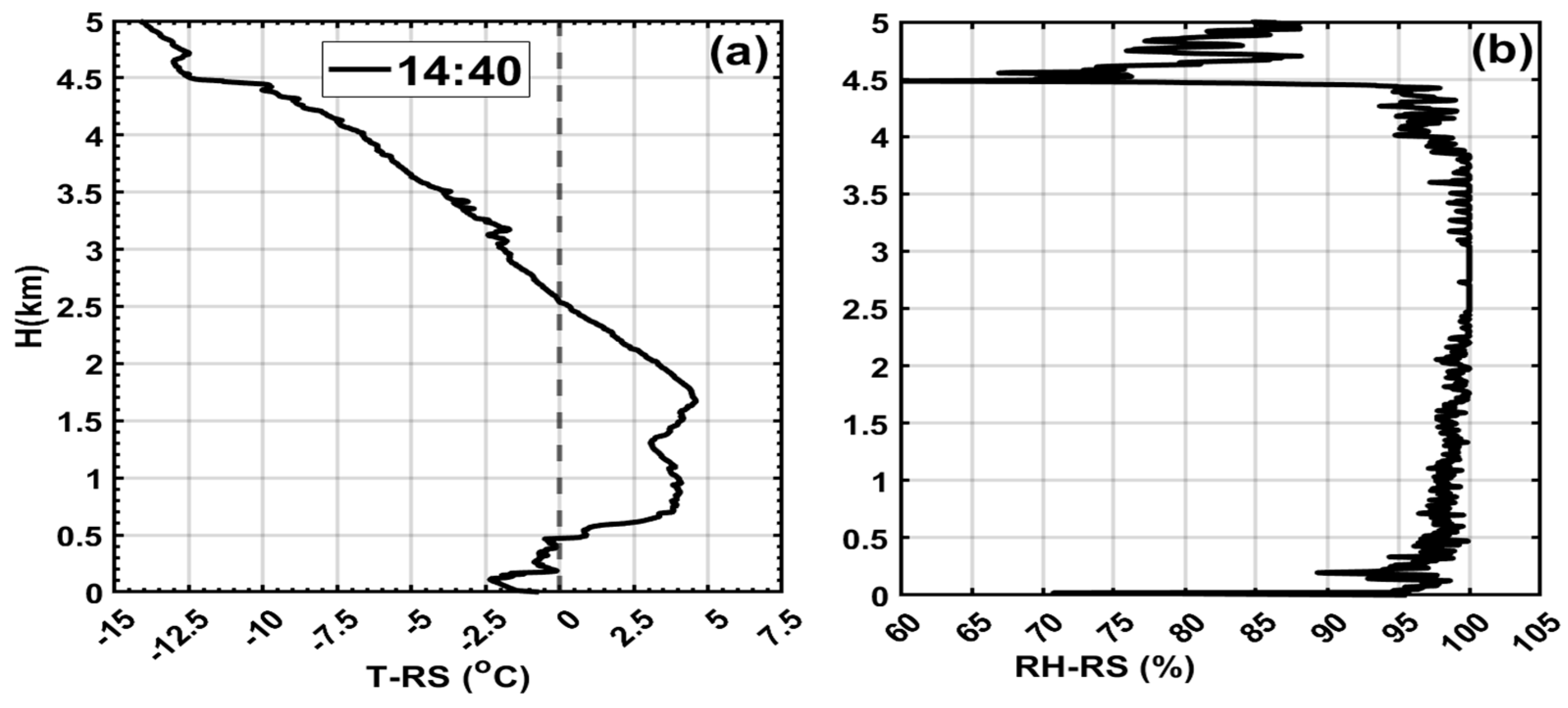

The temperature and RH profile obtained at 14:40 UTC using a radiosonde (

Figure 7a,b) shows a freezing level (FL) near 2.5 km that coincides with the data shown in

Figure 6 b and c. Below the FL the temperature warmed significantly close 5

oC that would potentially melt the snow. The bottom cold layer (H<0.5km) cooled to -2.5

oC, but the surface temperature warmed up close to -1

oC as a result of this and the shallowness of the layer (H <0.5 km), melted liquid drops remained to be liquid in a supercooled state when they reached the surface that led to ZR. The RH profiles show near saturation between heights (0.5km <H < 4 km), but it is sub-saturated in the supercooled layer (H <0.5 km). The ZL events reported after 16:00 UTC does not seem to be associated with any ML which implies that they are formed via the non-classical freezing mechanism, this can not be tested because of the absence of Radiosonde data.

3.3. Case Study of Mixed Precipitation Dominated by IP on 23 Feb, 2022

Figure 8 shows similar plots as

Figure 5, but in this case on Feb 23, 2022, during the period (time < 04:00 UTC), the PT is dominated by IP according to the human observer, but the FD71P reported ZR and the PARSIVEL probe mainly reported RLS (

Figure 8a). During the time 04:00-06:30 UTC, both instruments and human observer reported ZR and ZL, but the human observer reported more frequent ZL. The size distribution also suggests the presence of ZL size particles (D<0.5 mm) during relatively light precipitation (P< 1 mmh

-1), particularly near 03:40 UTC (

Figure 8c). During the IP events, the surface temperature varied from -7

oC to about -3

oC, but the RH remained close to 90%, and the precipitation intensity varies from 1 mmh

-1 to 5 mmh

-1. The mean diameter varied slightly from 1 mm to 1.3 mm and the associated mean velocity varied from 3.5 ms

-1 mm to 5 ms

-1 (

Figure 8c). Most of the particles are below 1.5 mm reaching a maximum of about 3.5 mm (

Figure 8d). During the ZR and ZL events the temperature and RH remained for most part close to -3

oC and 90% respectively although the temperature slightly decreased. The possible reasons for some of these discrepancies between the manual and instrument-based PT will be discussed in more depth in Section 2.4.

As illustrated in

Figure 9a,b,c all the IP events were associated ML. The FL is well coincided with the beginning of enhanced fall velocity LWC and radar reflectivity factor except near 4 UTC where the instruments reported ZR, and the human observer reported minor IP and one event of ZL associated with light precipitation (P < 1 mmh

-1).

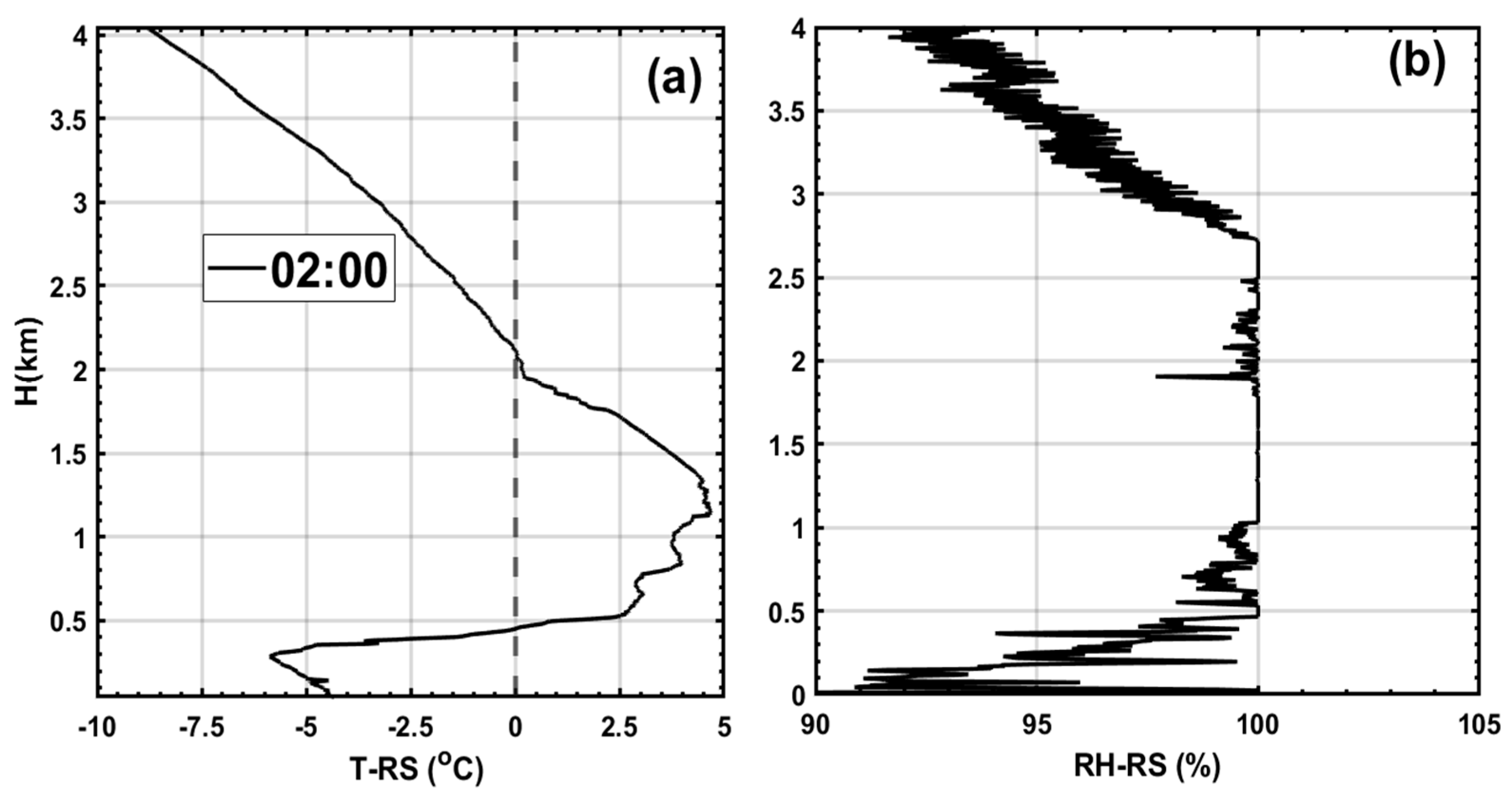

One example showing Radiosonde based vertical profiles of temperature and RH obtained at 02:00 UTC are given in

Figure 10. As indicated in the figure, the RH and T profiles are similar to the ZR case, but the temperature of the bottom cold layer (H<0.5 km) is much colder (-7

oC < T < 0

oC) and the surface temperature is near -5

oC which led to freezing of the supercooled drops as IP.

3.4. Velocity and Size Relationships and Precipitation Types

As mentioned earlier, instruments sometimes miss classify some of the PTs because of similarity of the velocity and size relationships of the PTs, this is particularly true for the instruments that use the observed V, size (D), and T information to diagnose PT. To investigate these V and D relationships for selected R, ZR, and IP, and mixed snow events are investigated. For these comparisons well established empirical V-D relationships for rain (

Gunn and Kinzer, 1949), given as

and a theoretically derived V for solid precipitation proposed by

Heymsfieldd and Westbrook, (2010), and other relationships based on observation for fresh hailstones (

Knight and Heymsfield, 1983) and medium density lump graupel (

Locatelli and Hobbs, 1974), and also hailstones (

Mitchel, 1996) have been used (see

Table 3).

Following

Heymsfield and Westbrook, (2010) (HW), the theoretical derivation of V based on drag force (

), drag coefficient (

, falling particle projected area (A) and air density

is given as

Heymsfield and Westbrook developed a parameterization that relates

to Renolds number (

) in a form.

where

and

and then

is defined as

where the modified best number (X) is defined as

where

is the gravitational acceleration set at 9.8 ms

-2, µ is dynamic viscosity of air,

is the mass of falling particle,

is the area ratio defined as

. Assuming a spherical particle, the mass of the falling particle, with density

, can be estimated as

The terminal velocity or in this case fall velocity is defined as

In this study it was assumed that = 1.246 kg m-3, =1.778x10-5 kg (ms)-1, , and the is assumed to be 0.91 gcm-3 for a dense solid sphere (Ssp=0.91) such as IP and for a fresh relatively less dense sphere the density was assumed to be 0.35 gcm-3 (Ssp=0.35),

Table 2.

D in mm and V is in ms-1.

Table 2.

D in mm and V is in ms-1.

| a |

b |

Type |

| 1.3 |

0.66 |

Lump graupel |

| 2.364 |

0.553 |

Fresh hailstone |

| 3.74 |

0.5 |

Hailstone |

Figure 11 shows the observed velocity and size distribution (

) observed using the PARSIVEL probe for selected days on March 06 (

Figure 11a,b), Feb 17 ((

Figure 11c,f), and Feb 23 (

Figure 11d,e) as indicated on the plots during ZR, S, R and IP events respectively. The uncertainties in measured fall velocities are removed when V is greater than

and lower than

- 0.5

for liquid and frozen drops events following (

Leston and Pryor 2023) and for snow case only particles that exceeded the

threshold are removed when they are encountered.

According to the results given in

Figure 11, for both during the R and ZR events, the

closely followed Equation 1 or the

empirical curve (

Figure 11 a–d,f). However, during the IP (

Figure 11 d,e) events, the

curve line is slightly below the

and approximately follows the

-HW which is consistent with frozen spherical drops (IP) (

Figure 11d). This is consistent with previous studies (

Rahman and Testik, 2020;

Nagumo et al, 2019;

Lachapelle et al.

, 2024). The similarity of the IP and ZR curves suggests that instruments that employ the V-D relationship, may sometimes confuse the two as discussed earlier. In the time interval of

Figure 11d (0200-02:30 UTC) both the manual observation and FD71P agreed reasonably well (

Figure 8a). Even when the two does not agree (

Figure 11e and

Figure 8a), the results does not change suggesting that the problem may be related to the type of algorithm being used by the FD71P to differentiate between IP and ZR/R. On the other hand, in the case shown in

Figure 6a, both the human observer and the instruments generally agreed reasonably well reporting ZR, ZL and S except near 08:00 UTC (

Figure 5a and

Figure 11b). During this time the human observer reported IP with some secondary SP which agreed with the PARSIVEL, but the FD71P mainly reported S since the FD71P does not normally report SP. According to the results shown in

Figure 11b, the

approximately follow the fresh hailstone (FHS-KH) and also the curve that delineates spherical solid sphere with density of 0.35 gcm

-3 (

-HW), particularly at higher

values. Thus, this suggests that the presence of mainly nearly spherical particles with relatively lower density than solid ice such as SP or sometimes referred to as soft hail and this is not normally reported by the FD71P.

These results suggest that when PT is dominated by IP, under some conditions the FD71P may misclassify the PT as ZR and this needs to be further investigated in order to better understand the pertinent reasons. This requires knowing how the Vaisala FD71P diagnose precipitation type using a proprietary software that is not currently described in its user manual.

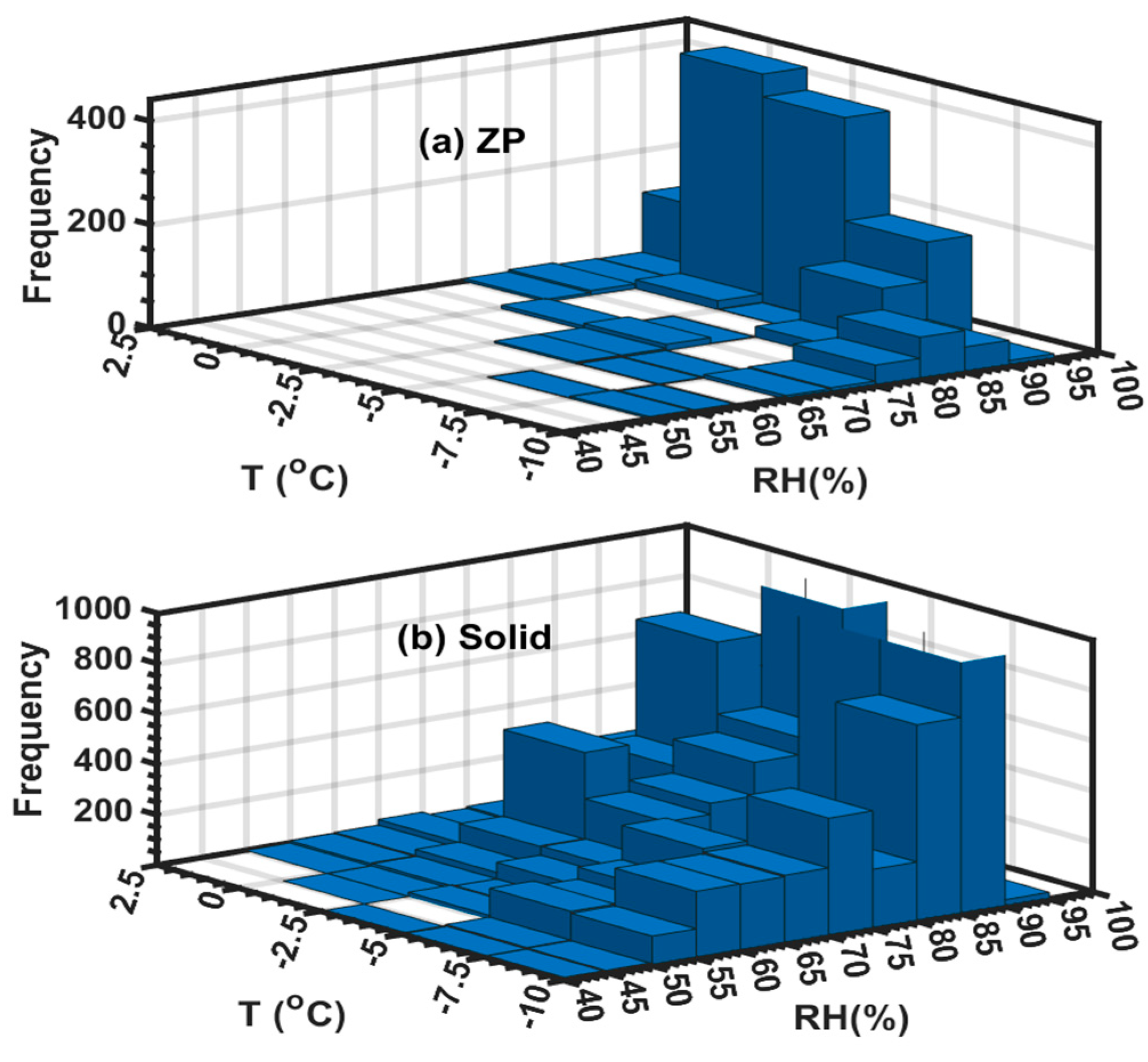

3.5. Solid and Freezing Precipitation as a Function of RH and T

As discussed earlier the precipitation at the surface is determined through dynamical and cloud microphysical process aloft. Traditionally, however, it is the surface temperature that is used to distinguish the boundary between snow and rain and potential for freezing precipitation. Some recent studies, including the analysis carried out in this study, show that there is a significant variation in temperature threshold that delineates the snow-liquid boundary (Jennings et al., 2018). According to Jennings et al., the continental climate showed the warmest snow-liquid boundary temperature threshold as compared to the maritime climate. Generally, the drier (low RH) regions get more snow at relatively warmer temperatures. This has been attributed to fact that as the solid particles pass through subsaturated environment, evaporative cooling of the air keeps the falling particles in solid phase and hence allow solid particles reach the ground event at warmer surface temperature. As a result, some surface models include RH in addition to T (Sun et al., 2022; Jennings et al., 2018). Nonetheless, forecasting precipitation phase and the associated boundary between liquid and sold phase is still a challenging problem.

To understand the dependence of precipitation on both surface T and RH, the 2D histogram plots of 1 min averaged freezing precipitation (ZP) and solid precipitation (S, IP, IC, and SG) events are shown in

Figure 12. For the similar T range , the ZP events generally occur at relatively higher RH ( RH > 75%) as compared to solid phase case that shows significant snow events down to RH 50%. During the ZP events, the frequency of the occurrence of the event generally increases with increasing T within the T interval (-10

oC<T<0

oC) , but at warmer temperatures (0

oC<T<2.5

oC) the frequency becomes rather smaller (

Figure 12a) , but no significant RH dependence, particularly for T (T > -5

oC). The maximum ZP occurred at relatively sub-saturated environment (90%<(RH<95%) when the temperatures were warmer (0

oC <T<-5

oC). During the solid precipitation events, for a given T the frequency generally increased with increasing RH, but the maximum occurred at relatively lower RH values (80%<RH < 85%) and warmer temperatures similar to the ZP events. For lower RH values (RH < 85%) the occurrence of snow events is more frequent than ZP at warmer temperatures ( 0

oC <T < 2.5

oC) (

Figure 12a,b) confirming the fact that snow events maybe more frequent at low RH and warmer temperatures. The inclusion of RH to identify the solid and liquid boundary for some mixed-phase precipitation events maybe relevant but based on this study it is not straight forward how the RH should be incorporated.

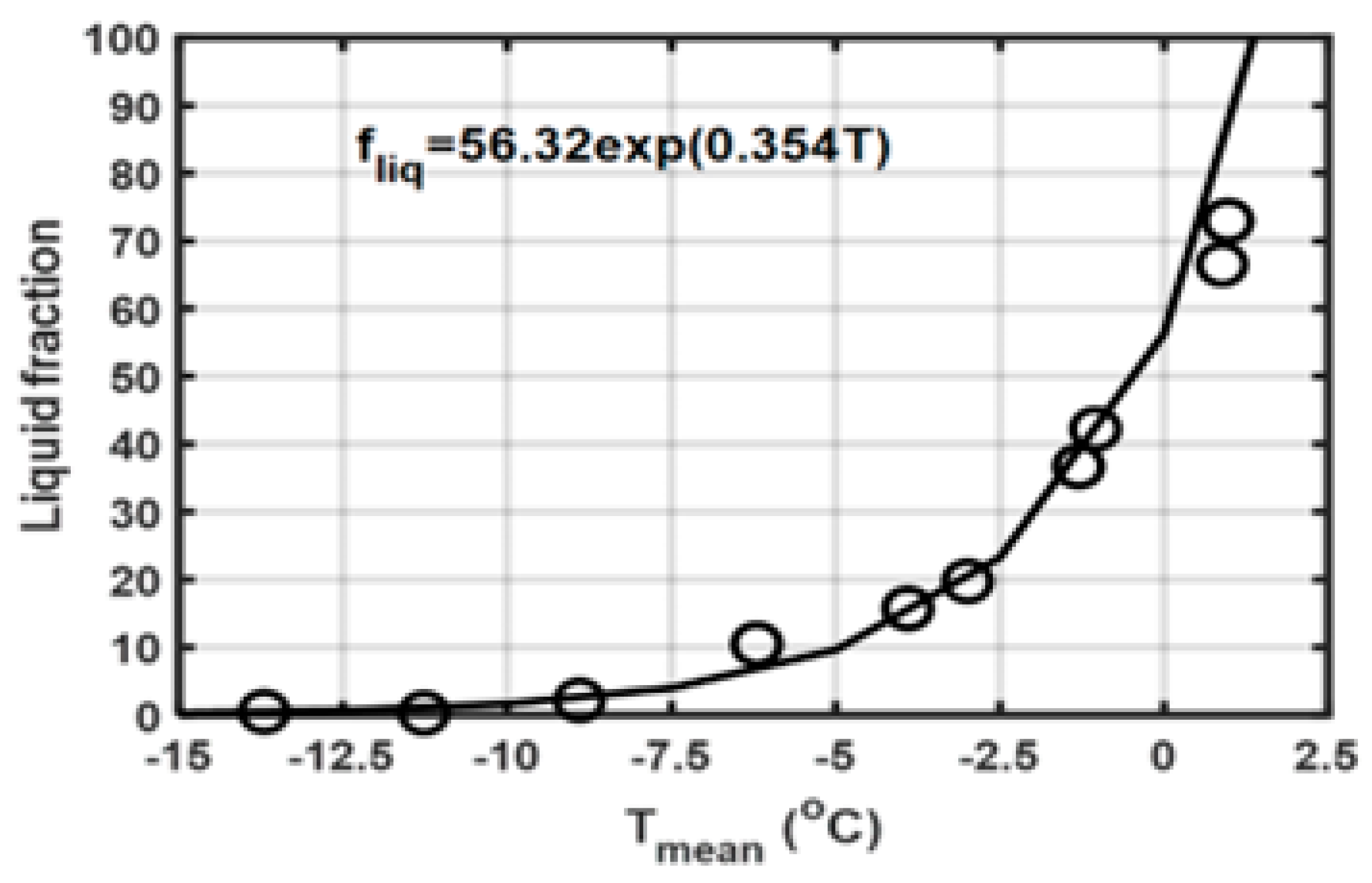

Knowing the number of solid and liquid phase events at a given temperature interval, it is possible, however, to derive the percentage of the time that liquid phase events occurred as a function of the mean temperature and the result is given in

Figure 13. According to the results indicated in the plot, on average at freezing temperature (T = 0

oC), about 60% of the precipitation is in liquid phase. This is remarkably similar to the finding reported in

Boudala et al, (2017) who have used direct manual measurements of liquid and solid precipitation during mixed precipitation events. Complete liquid phase precipitation does not occur unless the temperature is close to 2

oC. According to this result all solid phase precipitation occurs at temperatures close to -10

oC. In some studies, T=-2

oC was used as a threshold for delineating the upper bound below which the precipitation is all in solid-phase (E.g.,

Smith et al, 2022), but as demonstrated here on average about 28% of the precipitation could be in liquid phase at this temperature threshold. It should be noted that that there are some uncertainties related to the identification of the precipitation type. However, as demonstrated earlier, optical instruments are much more reliable identifying solid and liquid as compared to the identification of more detailed precipitation type. The results shown in

Figure 15 can be only considered in the average sense; it possible that under some conditions, all solid phase precipitation could be observed for temperature (T < -2

oC).

3.6. Precipitation

3.6.1. Comparisons of Solid Precipitation Using the Instruments and Manual Measurments

In the absence of a standard reference such as snow gauge in the Double-Fence Automated Reference (Boudala and Milbrandth, 2023) for snowfall amount at the surface, it is difficult to validate the precipitation data measured. However, there has been sporadic snow depth and snow water equivalent (SWE) measurements at the surface using the Snowmetrics Tube Sampler and a hanging spring scale with a 0.1 mm precision (STS) (Boudala et al., 2014). The measurements were carried out on a 41 cm x 41 cm x 1.25 cm white wooden snowboard. The snow depth was measured at average of at least 3 measurements and only a single measurement in case of the SWE by the UQAM research team. The snowboard was cleared before the measurements, but there were times that this has not been done and this was noted in the datasets. It should be noted here that there are some uncertainties in the measurement process that are not easily quantifiable, particularly a single measurement of SWE is probably more prone to be more uncertain.

Table 3 shows comparisons of measurements conducted on four dates in February and March 2022. The maximum surface wind speed (

) at gauge height level and T, and the PT are also given in the table. The values of

were quite low to impact the collection efficiency of the Pluvio2 or PARSIVEL probe since these instruments are normally expected to respond to enhanced wind speed (

Boudala and Milbrandt, 2023). As indicated in the Table there are some variabilities among the instruments and the manual measurements, and this can be attributed to many factors including uncertainty associated with the manual measurements as well as the difference in the measurement methods employed by the instruments. On average, however, the Pluvio2 gauge measured relatively smaller amount as compared to the manual measurement and the PARSIVEL with no modification, relatively measured higher amount of precipitation. As shown in the Table, the wind speeds were quite low (

< 1.5 ms

-1 ) , thus not expected to explain these differences. The FD71P and the modified PARSIVEL data relatively agreed with the manual measurements. The comparison of the instruments using the entire datasets suggests similar conclusions and this will be discussed in the next section.

Table 3.

Comparisons of the solid precipitation measurements using the FD1P, PARSIVEL, Pluvio2 and manual snow water equivalent (SWE) measurements.

Table 3.

Comparisons of the solid precipitation measurements using the FD1P, PARSIVEL, Pluvio2 and manual snow water equivalent (SWE) measurements.

| Dates |

Manual

(SWE) |

FD71P

(mm) |

Pluvio2

(mm) |

(mm) |

(mm) |

T(oC)

(PT)

|

(ms-1)

|

| 20220301 |

5 |

12 |

3.5 |

6 |

6 |

< -7 (S) |

< 0.6 |

| 20220312 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

6 |

< 0.5 (S) |

<0.5 |

| 20220223 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

18.5 |

18 |

<-4.5 (IP) |

< 1 |

| 20220218 |

20 |

21 |

12 |

40 |

30 |

< 2 (S) |

< 1.5 |

| Total (mm) |

52 |

57 |

39.5 |

70.5 |

60 |

|

|

| Inst/Man |

- |

1.1 |

0.76 |

1.36 |

1.15 |

|

|

3.6.2. Comparisons of the Instruments Measuring Precipitation Using the Entire Data

Figure 14 show 10 min averaged liquid phase precipitation intensity measured using the three different instruments. The Pluvio2 gauge (Pluv2) is generally reasonably correlated (R=0.8) with optical probes (

Figure 14a,b), but it is evident that there are a lot of scatters at lower intensities (P < 1 mmh

-1), and this is maybe related to the poor sensitivity the Pluvio2 gauge (

Boudala et al.

, 2017). The mean ratio (MR) calculations show that the FD71P is close to the Pluvio2 with MR = 0.95 as compared to the PARSIVEL with a MR = 1.45 indicating that PARSIVEL measures 45% more precipitation than the Puvio2 . There are no significant differences between the PARSIVEL calculated and directly outputted precipitation intensities versus the FD71P (

Figure 14c,d). The discrepancy between the Pluvio2 and the optical probes maybe attributed to many factors including the sensitivity difference between the two instruments. There is excellent agreement between FD71P and PARSIVEL (R= 0.9), but on average the PARSIVEL probe measured 50% more precipitation than the FD71P. Provided that FD71P is relatively new instrument, further investigation is required to make definitive conclusions.

As shown in

Figure 15a,b, contrary to the liquid phase in

Figure 12, the Pluvio2 gauge underestimated the solid phase precipitation by a factor of 2 as compared to both optical instruments like the case discussed in the previous section. Since the 10 min averaged wind speed rarely exceeded 3 ms

-1 (not shown here), this is not expected to be due to under catch caused by wind speed. The two optical probes are generally well correlated (R=0.8), but the PARSIVEL probe slightly overestimated (20%) as compared to the FD71P, but the modified PARSIVEL data agreed reasonably well with the FD71P with MR=1(

Figure 15d) as also has been noted earlier when the two probes compared against the manual measurements. The more significant overestimation the unmodified PARSIVEL against the Pluvio2 data maybe partly caused by the internal algorithm employed by the PARSIVEL, particularly related to the density of snow and riming effects. The PARSIVEL disdrometer and Pluvio2 gauge have been tested based on more robust standard reference data (

Boudala and Milbrandt, 2023), but the FD72P is relatively new and not tested in similar fashion and hence further studies are needed to get better insights.

Figure 14.

The liquid precipitation intensity measured using FD71P and Pluvio2 (a), PARSIVEL and Pluvio2 (b), PARSIVEL and FD71P (c), and PARSIVEL calculated (cal) and FD71P (d).

Figure 14.

The liquid precipitation intensity measured using FD71P and Pluvio2 (a), PARSIVEL and Pluvio2 (b), PARSIVEL and FD71P (c), and PARSIVEL calculated (cal) and FD71P (d).

Figure 15.

The solid precipitation intensity measured using FD71P and Pluvio2 (corrected and uncorrected for wind) (a), PARSIVEL and Pluvio2 (b), PARSIVEL and FD71P (c), and PARSIVEL and FD71P (d).

Figure 15.

The solid precipitation intensity measured using FD71P and Pluvio2 (corrected and uncorrected for wind) (a), PARSIVEL and Pluvio2 (b), PARSIVEL and FD71P (c), and PARSIVEL and FD71P (d).

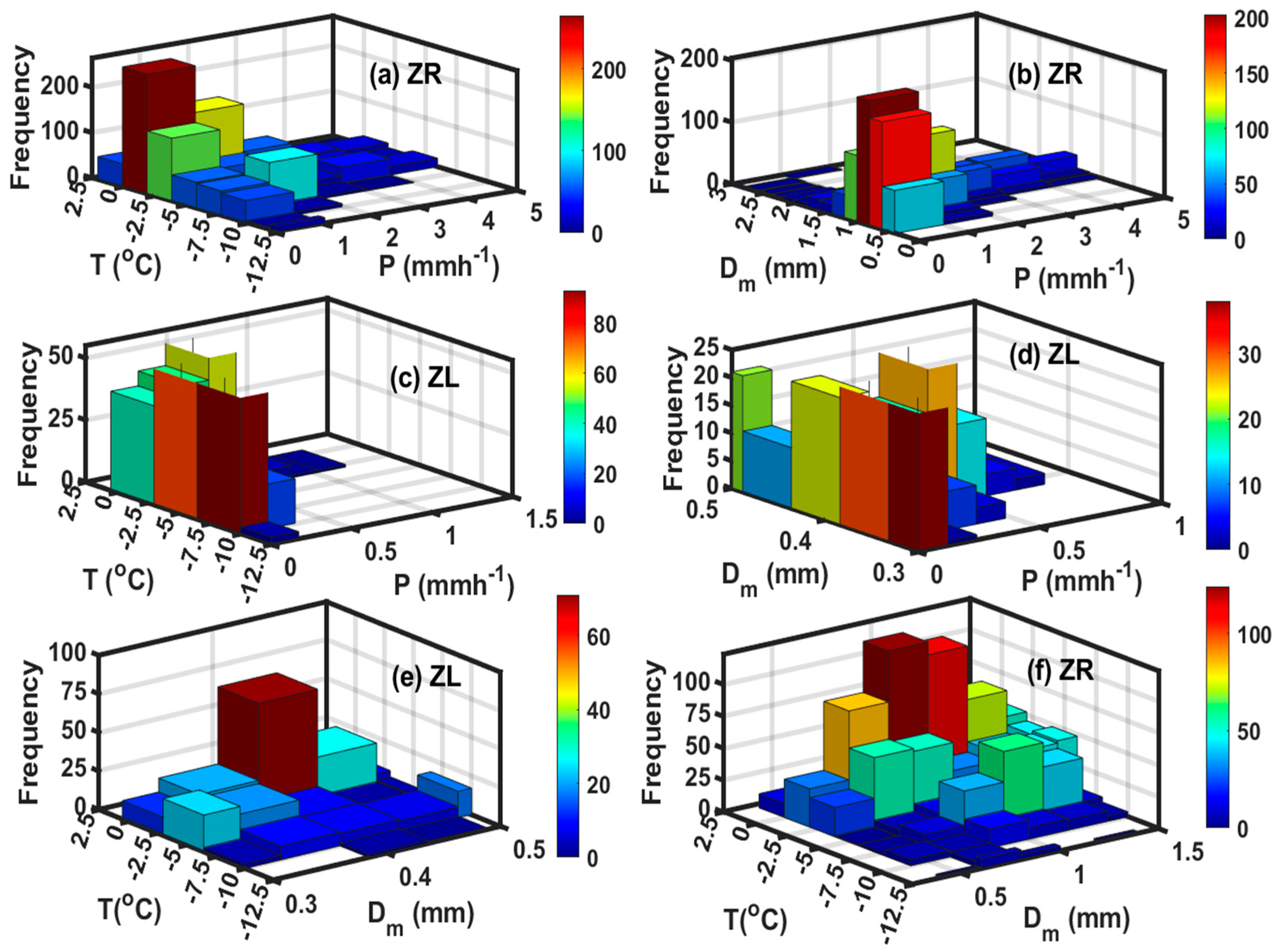

3.6.3. The Frequency Distributions of Freezing Precipitation as a Function of and T

Figure 16 shows the 2D frequency distributions of precipitation intensity (P),

and T function for ZR and ZL events using the entire datasets shown in

Figure 3. Most of freezing precipitation during the ZR events occurred during temperature interval (-2.5

oC <T <0

oC) , P < 1 mmh

-1, and 0.5 mm<

<1 mm (

Figure 16 a,b). The maximum P and

values during the ZR events reached 5 mmh

-1 and 2.5 mm respectively. On the other hand, most of the ZL events occurred at colder temperature (-10

oC < T < -2.5

oC) which suggests non-classical formation mechanism (

Isaac et al.

, 1998) and mostly associated with P < 0.25 mmh

-1. Contrary to ZR events, no ZL events were observed at warmer temperatures (T< 0C). The majority of the

of the ZL particles ranges 0.3<

<0.4 mm. The maximum values of P and

during ZL events were 1 mmh

-1 and 0.5 mm respectively. However, most of the larger particles for ZR and ZL events occurred at warmer temperatures (-2.5

oC<T<0

oC).

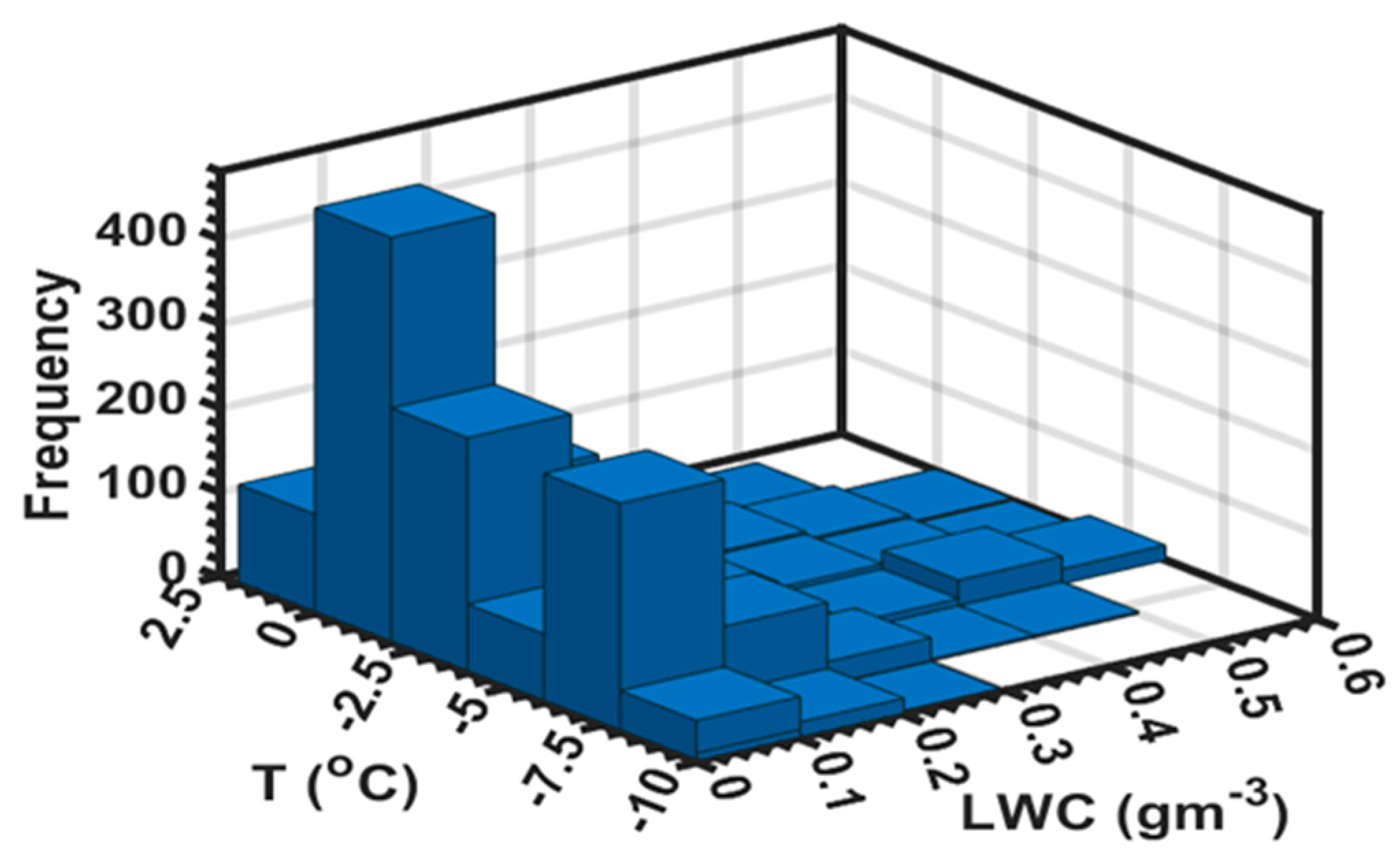

3.6.4. The 2D Frequency Distributions of Freezing Precipitation as a Function of and T

Figure 17 shows the LWC in ZP reached up to 0.6 gm

-3, but during most of the events the LWC were less 0.1 gm

-3 and mostly occurred at temperatures ( 0 < T < -2.5

oC). There is however a secondary peak in LWC near -7.5

oC, may be associated with ZL as indicated in

Figure 17. It is also evident that some LWC (<0.1 gm

-3) in ZP may occur at warmer temperature (0

oC < T < 2.5

oC) as would be expected based on

Figure 16.

3.6.5. The Relationship Between LWC, and Freezing Precipitation

The intensity of the icing because of ZP depends on the precipitation intensity and duration of the precipitation. Some empirical models that estimate the ice accretion of the ice thickness use the LWC as input and this is normally derived using P (

Jones, 1998;

Jone,1998, 2022;

Cao et al.

, 2014) based on empirical power low relationships (Best, 1949;

Marshall and Palmer, 1948). To compare these power law relationships between LWC and P, 10 min averaged LWC and P were derived based on particle spectra measured using the PARSIVEL probe (

Figure 18a). Also, LWC was parameterized as function P and

(

Figure 18b). The best fit equations are given in Eqs (8) and (9).

According to these results the LWC is strongly correlation with P with correlation coefficient (R=0.97) and with a root mean square error (RMSE ) of 0.27 gm-3. . The best fit line agreed well with the one based on Best, 1949. The Marshal and Palmer method slightly overestimates the LWC and this has been also noted by earlier study (Jones, 1998). The inclusion of did not improve the estimation of LWC, but the parameterization maybe used to derive using the two equations since it is one of the important parameters used for parameterization of particle size distribution.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we have analyzed data collected in wintertime mixed-phase precipitation using several specialized instruments including the Vaisala FD71P and PARSIVEL that measure precipitation and type (P) and fall velocity (V) and precipitation size spectra (N(D)). Also used were a Micro Rain Radar (MRR) that measures V and radar reflectivity () and a single Alter shielded Pluvio2 that measures precipitation (P). The data includes some manual measurements of PT and snow water equivalent (SWE) snowfall based on the Snowmetrics Tube Sampler. The observed P and PT measured using the FD71P and Parsivel probes were compared against the manual measurements as well as the Pluvio2 precipitation gauge. The P and PT were characterized based on temperature (T) and humidity (RH), and microphysical quantities such mean mass weighed diameter (), fall velocity (V), and liquid water content (LWC). The freezing precipitation (ZP) and solid precipitation events were studied using integrated data sets of surface-based observations and vertical profiling dada obtained using the MRR and Radiosonde. Based on this study, the following key findings have been noted:

The comparison of the reported PT against human observation shows that FD71P and PARSIVEL agree reasonably well in detecting liquid phase precipitation and snow events. However, the FD71P significantly overestimates freezing rain (ZR) and underestimates ice pellets (IP) events. Generally, the PARSIVEL detected rain (R), ZR, and snow (S) better than the FD71P. The FD71P was better at detecting ZL, and only the FD71P could detect IP. The discrepancy may relate to the uncertainty of the V-D relationship used for diagnosing ZR and IP. More studies are needed to draw definite conclusions due to the limited manual datasets.

Further analysis of PARSIVEL data showed similar V-D relationships during IP and ZR events. But the V-D curve was slightly lower than the empirical liquid phase curve. The V for IP can be theoretically modeled assuming frozen spherical drops, consistent with previous studies.

The integrated vertical profiling data from the MRR and Radiosonde, and the surface observations during ZR and IP events, show both events are associated with ML. The warm layer depth was 2 km, and the RH was near saturation, but the surface temperature during IP events was much colder. This suggests that surface temperature is a controlling factor determining IP or ZR.

Statistical 2D histograms of ZR and ZL events under different surface environmental conditions showed that most of the ZR events occurred at warmer temperatures as comparted to the ZL events that mostly occurred at colder temperatures. Most of the P and associated with ZR and ZL were (P< 1 mmh-1 and < 1 mm) and (P<0.25 mmh-1 and <0.4 mm ) respectively. The majority of the larger particles, however, occurred at relatively warmer temperatures for both events. The 2D histogram of LWC and T during the ZP (ZR + ZL) events resembles the 2D histogram of P and T showing two distinct peaks one for ZR at warmer temperature and the other for ZL at colder temperatures. The more frequent LWC values observed for both ZR and ZL events were less than 0.1 gm-3 although the value reached up to 0.6 gm-3 under some environmental conditions.

According to this study, there is some evidence that at low RH, more snow events occur as at warmer temperatures (0 oC < T < 2.5 oC) as compared to the ZP, but on average it is T that mostly controls the precipitation phase. A simple calculation of the percentage of phase fraction based on measurements of precipitation phase and temperature reveals that at freezing temperature on average close to 40% of precipitation is in solid phase and total ice phase does not occur until the temperature is close to -10oC. This is consistent with previous finding (Boudala et al, 2017).

Comparisons of precipitation measured using the optical probes (FD71P and PARSIVEL), and the SAS Pluvio2 gauge showed different results when compared during solid and liquid precipitation events. During the liquid events, although the comparison Plivio2 and the two optical probes were reasonably correlated (R=0.8) , there was significant scatter at lower P values (P <1 mmh-1). The two optical probes were well correlated (R= 0.9) although that PARSIVEL probe on average overpredicted precipitation amount. During the snow events, the Pluvio2 gauge on average underestimated the snow amounts by close to a factor of 2 , even when compared to manual measurements. This underestimation is not attributed to wind effects. On the other hand, the two optical probes agreed reasonably well (R=0.8). The snowfall amounts derived using a modified algorithm that includes riming effects agreed relatively well with FD71P and manual snow measurements. It should be noted that that the manual snow measurements were only limited to a few days, it is recommended that these instruments, particularly the FD71P, being a relatively new, need to be tested using a standard reference gauge.

The functional relationship between ZP intensity and LWC derived from the PARSIVEL probe showed excellent agreement with Best, (1949). However, the relationship based on Marshall and Palmer (1948) N(D) parameterization overestimated LWC, as noted by other researchers (e.g., Jones, 1998).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, F.S.B.; resources, project administration, D.M..; data curation, R.R. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, M.L., G.A.I, and J.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Robert Crawford for archiving the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Brief description of the Vaisala FD71P

The FD71P is a relatively new instrument developed by Vaisala and it is briefly described in their website

https://docs.vaisala.com/v/u/B211744EN-G/en-US. Based on its user’s manual and description given in Klugmann and Kauppinen, (2022), it is a forward scattering probe like the previous Vaisala present weather sensors with some modification in the forward scattering geometry and also this version provides the particle size and velocity information in addition to precipitation, type and visibility. It is equipped with a transmitter and a receiver similar to the previous present weather seniors, but in this case the transmitter and receiver are geometrically configured to look downward, and the transmitter transmits a thin sheet of light at wavelength (λ= 850 nm) as opposed to the conventional light cone, and the receiver measures the forward scattered light at an angle of 42

o. The instrument outputs precipitation particle number at 41 size and 26 velocity bins. According to the user’s manual, the particle size measured in a range 0.1 -7+ mm and velocity in a range 0-10+ ms

-1. Unfortunately, no bin sizes are assigned for bins >40, the last 41 bin represents any size greater than 7mm, this makes it difficult to analyze the particle distribution spectra (D > 7mm), particularly for snow. According to the manufacturer, the instrument can measure the shape, size, and velocity of the falling hydrometeors, but no descriptions are provided in the user’s manual how these are archived. The sampling area of the instrument is 3800 mm

2 and the sampling time is 60s (Vaisala Phillip A. Allegretti personal communication). According to the user’s manual the instrument can measure precipitation intensity in the range 0.01 - 999.99 mmh

-1 at a resolution of 0.01 mm and meets the WMO standard. The look-down geometry and hood heating protect the sensor windows against external disturbances. The FD70 series complies with ICAO, FAA, and WMO requirements and uses WMO and NWS weather codes in reporting. It has a visibility up to 100 km and an optimal forward scattering angle of 42 degrees. It has a 5 MHz sampling frequency and 5 s measuring cycle. The instrument also incorporates a Vaisala HMP155 HUMICAP probe that measures the humidity and temperature of the air.

Appendix A.2. PARSIVEL Modified Snowfall Calculations

The PARSIVEL probe measures velocity and size spectra based on 32 size and 32 velocity bins . Using the number of particles at each size and velocity bins (

) , the modified snowfall rare (

) was calculated as

Where

is the density of snow given as

where a and b are some coefficients (

Holroyd,1971) and

is the degree of riming given as

following

Bukovčić et al.

, (2018,) where

is the mean observed fall velocity and

is given as

References

- Brandes, E.A.; Ikeda, K.; Zhang, G.; Schonhuber, M.; Rasmussen, R.M. A statistical and physical description of hydrometeor distributions in Colorado snowstorms using a video disdrometer. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol. 2007, 46, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudala, F.S.; Milbrandt, J.A. Solid Precipitation and Visibility Measurements at the Centre for Atmospheric Research Experiments in Southern Ontario and Bratt’s Lake in Southern Saskatchewan. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudala, F.S.; Isaac, G.A.; Wu, D. Aircraft Icing Study Using Integrated Observations and Model Data. Weather Forecast. 2019, 34, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudala, F.S.; Isaac, G.A.; Filman, P.; Crawford, R.; Hudak, D. Performance of Emerging Technologies for Measuring Solid and Liquid Precipitation in Cold Climate as Compared to the Traditional Manual Gauges. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 2017, 34, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudala, F.S.; Isaac, G.A.; Rasmussen, R.; Cober, S.; Scott, B. Comparisons of snowfall measurements in complex terrain made during the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2014, 171, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudala, F.S.; Isaac, G.A. Parameterization of visibility in snow: Application in numerical weather prediction models, J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, D19202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchieri, J.R. A new operational system for forecasting precipitation type. Mon. Weather Rev. 1979, 107, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukovcic, P.; Ryzhkov, A.; Zrnic´, D.; Zhang, G. Polarimetric radar relations for quantification of snow based on Disdrometer data. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol. 2018, 57, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgouin, P. . A method to determine precipitation types. Weather Forecast. 2000, 15, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M.; Treadon, R.; Contorno, S. Precipitation type prediction using a decision tree approach with NMC’s Meso- scale Eta Model. Preprints, 10th Conf. on Numerical Weather Prediction, Portland, OR. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 1994, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Best, A.C. The size distribution of raindrops. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 1949, 76, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGaetano, A.T. Climatic perspective and impacts of the1998 northern New York and New England ice storm. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2000, 81, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, J. 1973. The climates of the United States. NOAA, 113 pp. [NTIS COM-74-11708/6.].

- Cortinas, J.V., B.C. Bernstein, C.C. Robbins, and J. W. Strapp,2004: An analysis of freezing rain, freezing drizzle, and ice pellets across the United States and Canada: 1976–90. Weather Forecast., 19, 377–390. [CrossRef]

- Gascón, E.; Hewson ,T.; Haiden, T. Improving predictions of precipitation type at the surface: Description and verification of two new products from the ECMWF ensemble. Weather Forecast. 2018,33:89–108. [CrossRef]

- Gunn, R.; Kinzer. , G.D. Terminal velocity of water droplets in stagnant air. J. f Meteorol. 1949, 6, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyakum, J.R.; Roebber, P.J. The 1998 ice storm—Analysis of a planetary-scale event. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2001, 129, 2983–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, E.W., III. The meso- and microscale structure of Great Lakes snowstorm bands: A synthesis of ground measurements, radar data, and satellite observations. Ph.D. dissertation, University at Albany, State University of New York, 1971, 148 pp.

- Hanesiak, J.; Stewart, R. . The mesoscale and microscale structure of a severe ice pellet storm. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1999, 123, 3144–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymsfield, A.J.; Westbrook, C.D. Advances in the estimation of ice particle fall speeds using laboratory and field measurements. J. Atmos. Sci. 2010, 67, 2469–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, G.A.; S.G. Cober; Korolev, A.V. ; Strapp, J.W. ; Tremblay, A.; Marcotte. D. L. Overview of the Canadian freezing drizzle experiment I, II, and III. Cloud Physics Conference. Amer. Meteor. Soc., August 17-21, 1998, Everett, WA.

- Ikeda, K.; Steiner, M.; Thompson, G. Examination of mixed-phase precipitation forecasts from the High-ResolutionRapid Refresh model using surface observations and sounding data. Wea. Forecasting 2017, 32, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, K.S.; Winchell, T.S.; Livneh, B.; Noah. P. Spatial variation of the rain–snow temperature threshold across the Northern Hemisphere. Nature Communications 2018, 1 -9. www.nature.com/naturecommunications. [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.F. Freezing Fraction in Freezing Rain. Weather Forecast. 2022, 47, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.F. A simple model for freezing rain ice loads. Atmos. Res. 1998, 46, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, N.C.; Heymsfield, A.J. . Measurement and interpretation of hailstone density and terminal velocity. J. Atmos. Sci 1983, 40, 1510–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachapelle, M.; Thompson, H.D.; Leroux, N.R.; Thériault, J.M., J. Measuring Ice Pellets and Refrozen Wet Snow Using a Laser-Optical Disdrometer. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2024, 63, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letson, F.; Pryor, S.C. From Hydrometeor Size Distribution Measurements to Projections of Wind Turbine Blade Leading-Edge Erosion. Energies 2023, 16, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, N.; Ross, D.; Graumann, A. Eastern U.S. flooding and ice storm January 1998. Tech. Rep., NOAA/National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, NC, 6 pp.

- Locatelli, J.D.; Hobbs, P. Fall speeds and masses of solid precipitation particles. J. Geophys. Res., V. 1974, 79, 2185–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martner, B.E., R. Rauber, R. Rasmussen, E. Prater, and M. Ramamurthy. Impacts of a destructive and well-observed cross-country winter storm. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 1992, 73, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minder, J.R.; Bassill, N.; Fabry, F.; French, J.; Friedrich, K.; Gultepe, I.; Gyakum, J.D.; Kingsmill, K.; Kosiba; Lachapelle, M. ; Michelson, D.; et al. P-Type Processes and Predictability: The Winter Precipitation Type Research Multiscale Experiment (WINTRE-MIX)-BAMS2023. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2023, 104, E1469–E1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.S. , Palmer, W.M. The distribution of raindrops with size. J. Meteorol. 1948, 5, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.L. The use of mass- and area-dimensional power laws for determining precipitating particle terminal velocities. J. Atmos. Sci. 1996, 53, 1710–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagumo, N.; Fujiyoshi, Y. Microphysical properties of slow-falling and fast-falling ice pellets formed by freezing associated with evaporative cooling. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2001, 143, 4376–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roebber, P.J.; Gyakum, J.R. Orographic influences on the mesoscale structure of the 1998 ice storm. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2003, 131, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.; Testik, F.Y. Shapes and Fall Speeds of Freezing and Frozen Raindrops. J. Hydrometeoro. 2020, 21, 1311–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, F.M.; Rauber, R.M.; Jewett, B.F.; Kingsmill, D.E.; Pisano, P.; Pugner, P.; Rasmussen, R.M.; Reynolds, D.W. Schlatter,T.W.; Stewart, R.E.; et al. Improving short-term (0–48 h) cool-season quantitative precipitation forecasting: Recommendations from a USWRP workshop. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 86, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, R.A.; Isaac, G.A. Freezing precipitation in Canada. Atmosphere-Ocean 1999, 37, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strapp, J.W.; Stuart, R.A.; Isaac, G.A. A Canadian climatology of freezing precipitation and a detailed study using data from St. John’s, Newfoundland. Proc. FAA Int. Conf. on Aircraft Inflight Icing, Vol. 2, Springfield, VA, FAA, DOT/FAA/AR-96/81,1996, 45–56.

- Thériault, J.M.; Stewart, R.E.; Henson, W. On the dependence of winter precipitation types on temperature, precipitation rate, and associated features. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol 2010, 49, 1429–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessendorf, S.A.; Ugg, A.; Korolev, A.; Heckman, I.; Weeks, C.; Thompson, G.; Jacobson, D.; Adriaansen, D.; Hagger, J. Differentiating Freezing Drizzle and Freezing Rain in HRRR Model Forecasts. Weather and Forecasting 2021, 36, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerr, R.J. Freezing rain: An observational and theoretical study. J. Appl. Meteor. 1997, 36, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Minder, J. R.; Winters, A.; Baima, R.; Thériault; Lachapelle, M.; Gyakum, J.; Wray, J.2022. WINTRE-MIX: Manual Hydrometeor Observation Reports. Version 1.0.11 data files, 2 ancillary/documentation files, KiB. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B. Regional and local influences on freezing drizzle freezing rain, and ice pellets. Weather Forecast. 2000, 15, 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, R.M.; Olthoff, L.; Ramamurthy, M.; Kunkel, K. The relative importance of warm rain and melting processes in freezing precipitation events. J. Appl. Meteor. 2000, 39, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, G.J.; Norman Jr., G. A. The supercooled warm rain process and the specification of freezing precipitation. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1988, 116, 2172–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y. Li; Duan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Chuan,w. Incorporating relative humidity improves the accuracy of precipitation. Atmos. Res. 2022, 271, 106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The ECCC observation site Sorel, Quebec, Canada.

Figure 1.

The ECCC observation site Sorel, Quebec, Canada.

Figure 2.

The ECCC instrumentation platform at the Sorel site. The views towards the east (a) and south (b).

Figure 2.

The ECCC instrumentation platform at the Sorel site. The views towards the east (a) and south (b).

Figure 4.

The frequency distributions of PT reported based on FD71 and PARSIVEL compared against the manual-based observations. The symbols represent no precipitation (C), snow (S), snow pellets (SP), ice pellets (IP),snow grains (SG), ice crystals (IC), rain (R), freezing rain (ZR), freezing drizzle (ZL), the PT is not identified (UN) , and R+L+S (RLS).

Figure 4.

The frequency distributions of PT reported based on FD71 and PARSIVEL compared against the manual-based observations. The symbols represent no precipitation (C), snow (S), snow pellets (SP), ice pellets (IP),snow grains (SG), ice crystals (IC), rain (R), freezing rain (ZR), freezing drizzle (ZL), the PT is not identified (UN) , and R+L+S (RLS).

Figure 5.

The time series of human and instrument-based PT (a), RH and T (b), precipitation intensity (Rate) based on FD71P (P), the mean particle ( ) size and fall velocity () (c), precipitation particle spectra based on PARSIVEL disdrometer (d).

Figure 5.

The time series of human and instrument-based PT (a), RH and T (b), precipitation intensity (Rate) based on FD71P (P), the mean particle ( ) size and fall velocity () (c), precipitation particle spectra based on PARSIVEL disdrometer (d).

Figure 6.

The time series of liquid water content (LWC) (a), equivalent radar reflectivity factor ( (b), fall velocity () (c) based on MRR. The time series of human and instrument-based precipitation type (PT) (d).

Figure 6.

The time series of liquid water content (LWC) (a), equivalent radar reflectivity factor ( (b), fall velocity () (c) based on MRR. The time series of human and instrument-based precipitation type (PT) (d).

Figure 7.

The vertical profiles of (T) (a) and RH (b) observed using Radiosonde on March 06, 2022.

Figure 7.

The vertical profiles of (T) (a) and RH (b) observed using Radiosonde on March 06, 2022.

Figure 8.

Similar to

Figure 5, but for 22 Feb 2022.

Figure 8.

Similar to

Figure 5, but for 22 Feb 2022.

Figure 9.

Similar to

Figure 6, but for 23 Feb 2022

.

Figure 9.

Similar to

Figure 6, but for 23 Feb 2022

.

Figure 10.

Similar to

Figure 7, but for 23 Feb 2022, case.

Figure 10.

Similar to

Figure 7, but for 23 Feb 2022, case.

Figure 11.

Velocity and size relationship based on PARSIVEL, the mean and standard deviation fall velocity, the empirical velocity and size relationship based on Gunn and Kinze , 1949 (G&K) for rain, hail stone (HS) based on Mitchel, (1996) (HS-M), solid sphere density of snow () 0.91 gcm-3(Ssp =0.91) and 0.35 gcm-3 (Ssp =0.35) based on Heymsfield and Westbrook, 2010 (HW), lump graupel of medium density based on Locatelli and Hobbs,1974 (GRL-midden-LH), and fresh hailstone (Knight and Hempfield, 1983 (HS-KH).

Figure 11.

Velocity and size relationship based on PARSIVEL, the mean and standard deviation fall velocity, the empirical velocity and size relationship based on Gunn and Kinze , 1949 (G&K) for rain, hail stone (HS) based on Mitchel, (1996) (HS-M), solid sphere density of snow () 0.91 gcm-3(Ssp =0.91) and 0.35 gcm-3 (Ssp =0.35) based on Heymsfield and Westbrook, 2010 (HW), lump graupel of medium density based on Locatelli and Hobbs,1974 (GRL-midden-LH), and fresh hailstone (Knight and Hempfield, 1983 (HS-KH).

Figure 12.

Composite two-dimensional histograms. The 2D density plots of 1 min averaged ZP (a), and solid precipitation (S, IP, IC and SG) (b) events plotted against T and RH.

Figure 12.

Composite two-dimensional histograms. The 2D density plots of 1 min averaged ZP (a), and solid precipitation (S, IP, IC and SG) (b) events plotted against T and RH.

Figure 13.

Liquid fraction calculated based on the observed temperature intervals and precipitation type.

Figure 13.

Liquid fraction calculated based on the observed temperature intervals and precipitation type.

Figure 16.

The 2D frequency distribution of ZR and ZL as a function temperature and precipitation intensity (P) (a,c), P and (b,d), temperature and (e,f).

Figure 16.

The 2D frequency distribution of ZR and ZL as a function temperature and precipitation intensity (P) (a,c), P and (b,d), temperature and (e,f).

Figure 17.

The 2D frequency distribution of T and LWC in freezing precipitation.

Figure 17.

The 2D frequency distribution of T and LWC in freezing precipitation.

Figure 18.

The10 min averaged observed LWC plotted against the precipitation intensity during the ZR events (a), and ZL (b) events. The best fit lines based on Best, (1949), Marshal and Palmer (1948) this study this study (best fit) are also show.

Figure 18.

The10 min averaged observed LWC plotted against the precipitation intensity during the ZR events (a), and ZL (b) events. The best fit lines based on Best, (1949), Marshal and Palmer (1948) this study this study (best fit) are also show.

Table 1.

The frequency distributions of PT based on manual, FD71P, and PARSIVEL probes.

Table 1.

The frequency distributions of PT based on manual, FD71P, and PARSIVEL probes.

| PT |

FD71P |

PARSIVEL |

Manual |

| C |

15.8 |

16.3 |

14.1 |

| S |

42.2 |

43.7 |

45.9 |

| SP |

NA |

4 |

1 |

| IP |

2 |

NA |

12.6 |

| SG |

0 |

0 |

0.7 |

| IC |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| R |

13 |

7 |

9 |

| ZR |

18 |

12.4 |

6.1 |

| ZL |

4 |

2 |

4.3 |

| RLS |

3.3 |

9.1 |

NA |

| L |

1.3 |

3.3 |

6.3 |

| RL |

0.22 |

2.8 |

0.22 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).