Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bitumen at Al-Qusur

2.2. Archaeological Samples Analyzed

2.3. Analytical Procedures

2.3.1. Bitumen Analysis

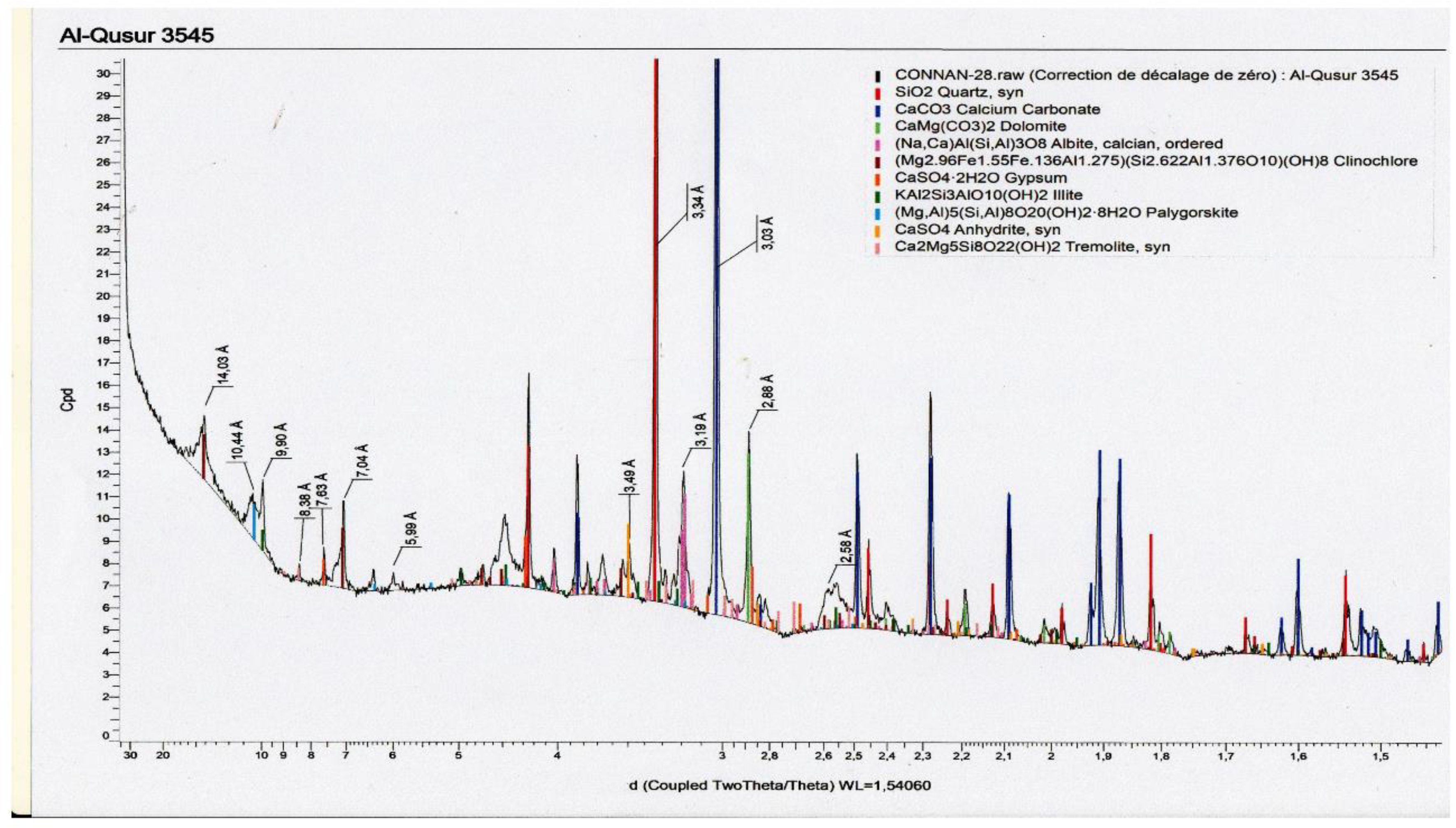

2.3.2. Mineralogical Analysis

2.3.3. Complementary Organic Analyses

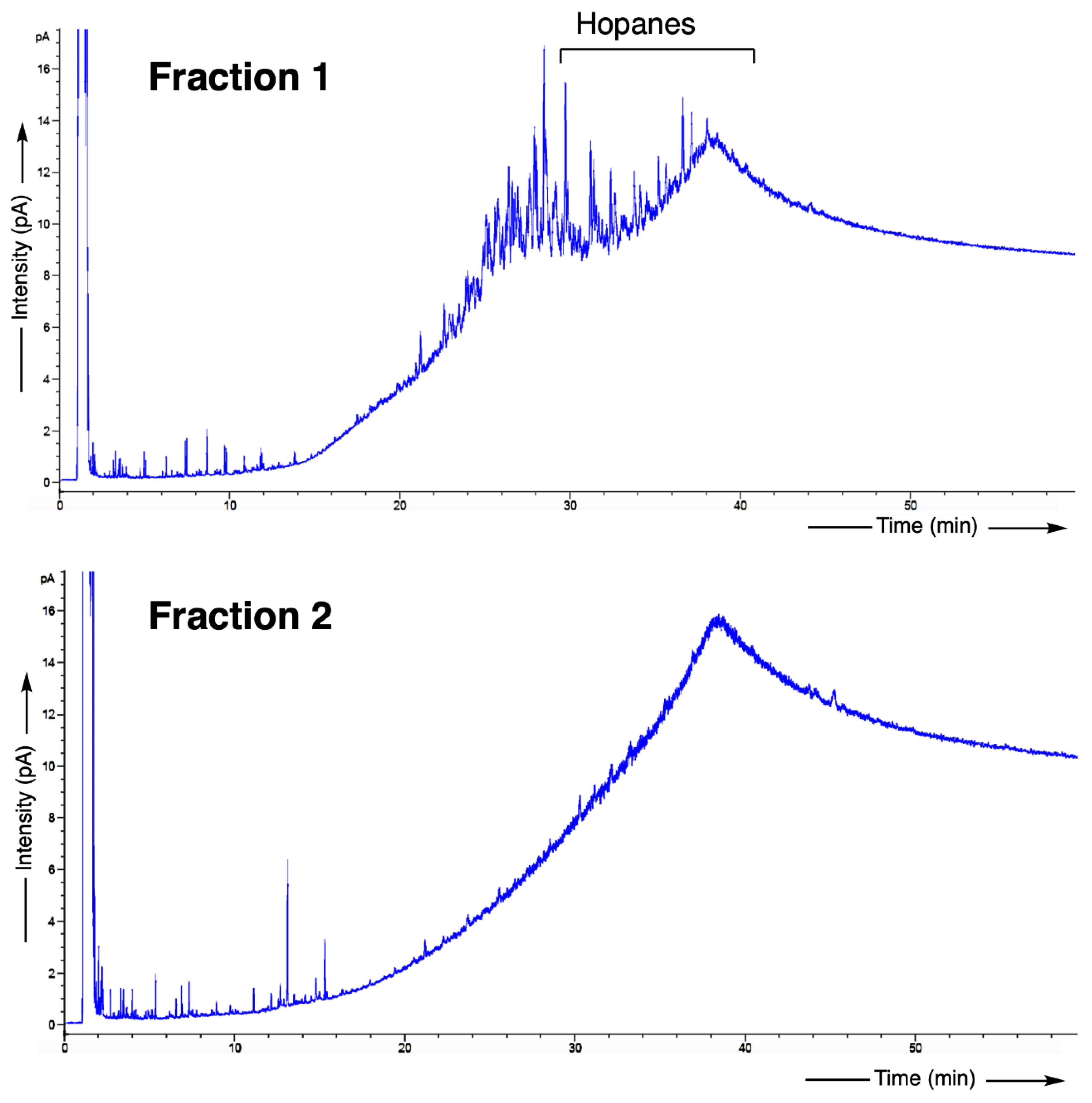

GC-FID

GC/MS

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gross Composition of Extractable Organic Matter

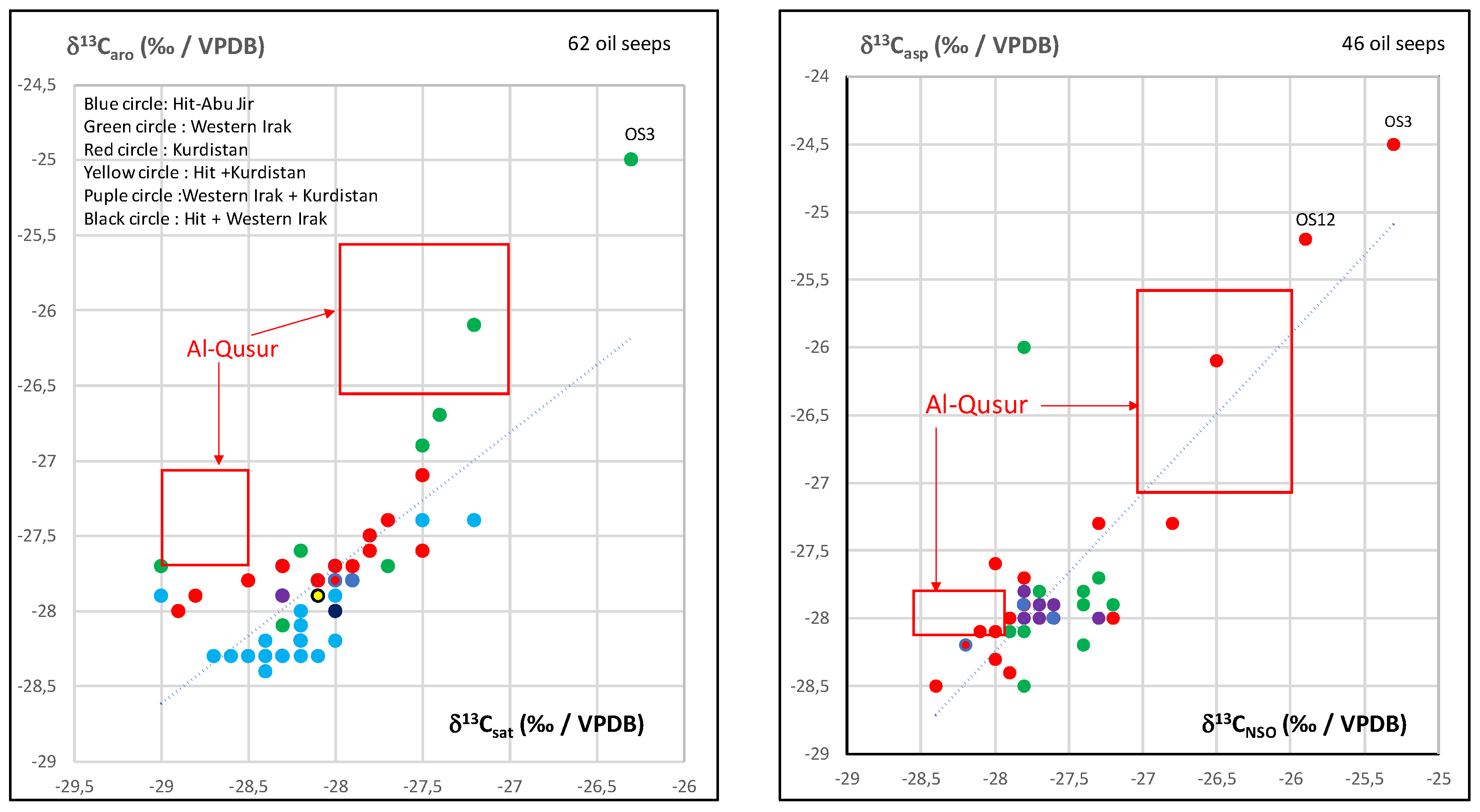

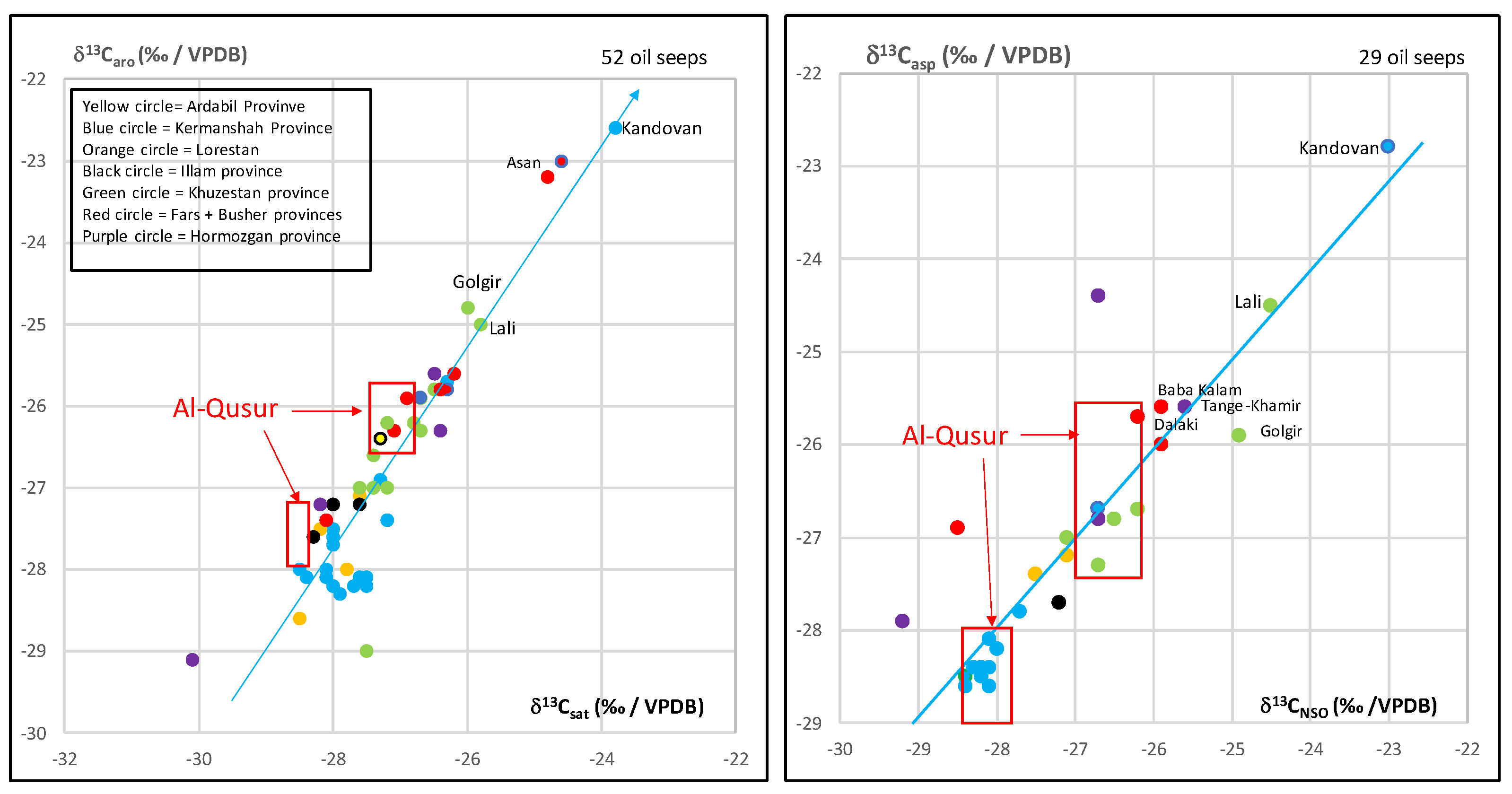

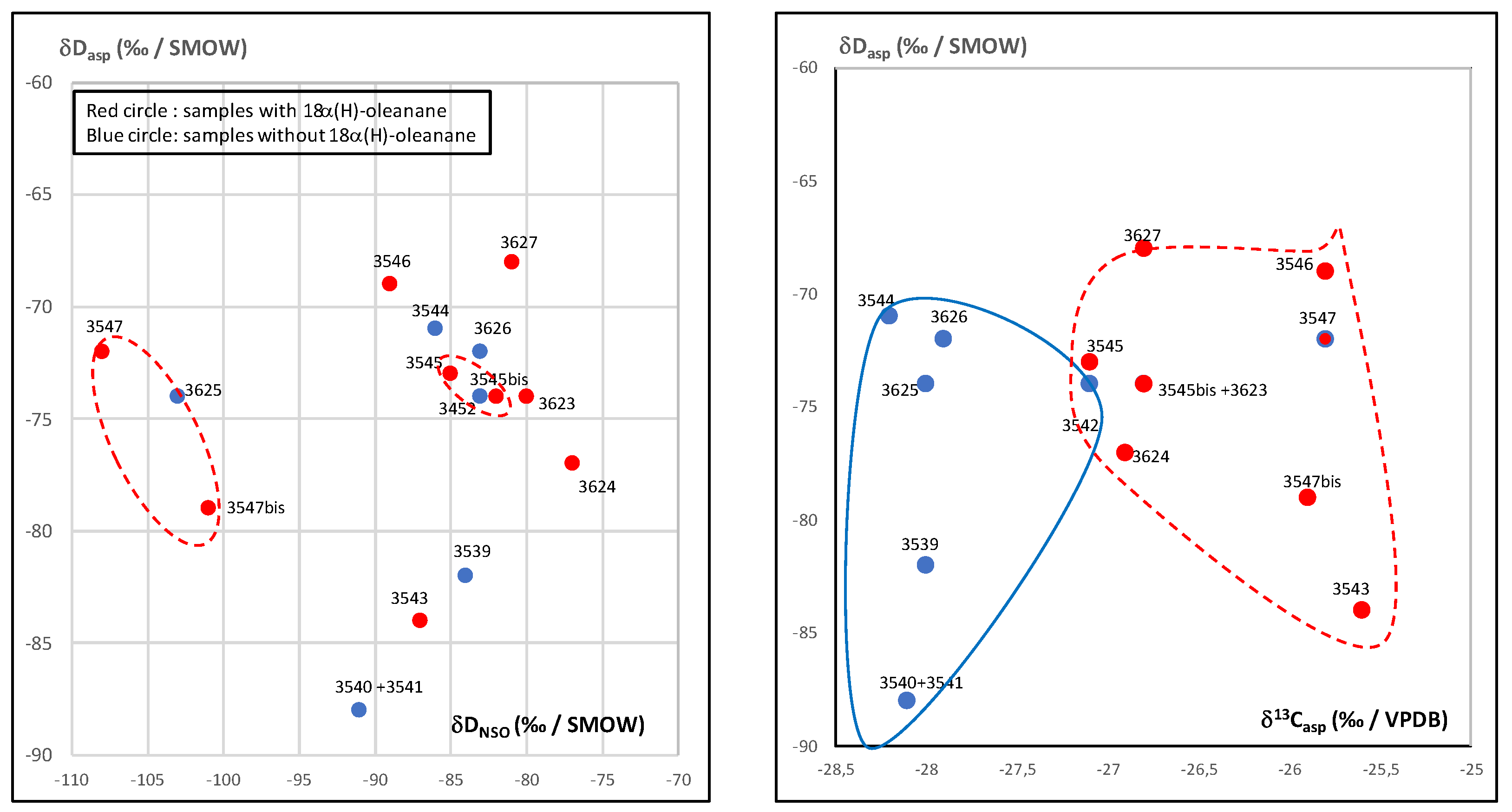

3.2. Isotopic Compositions

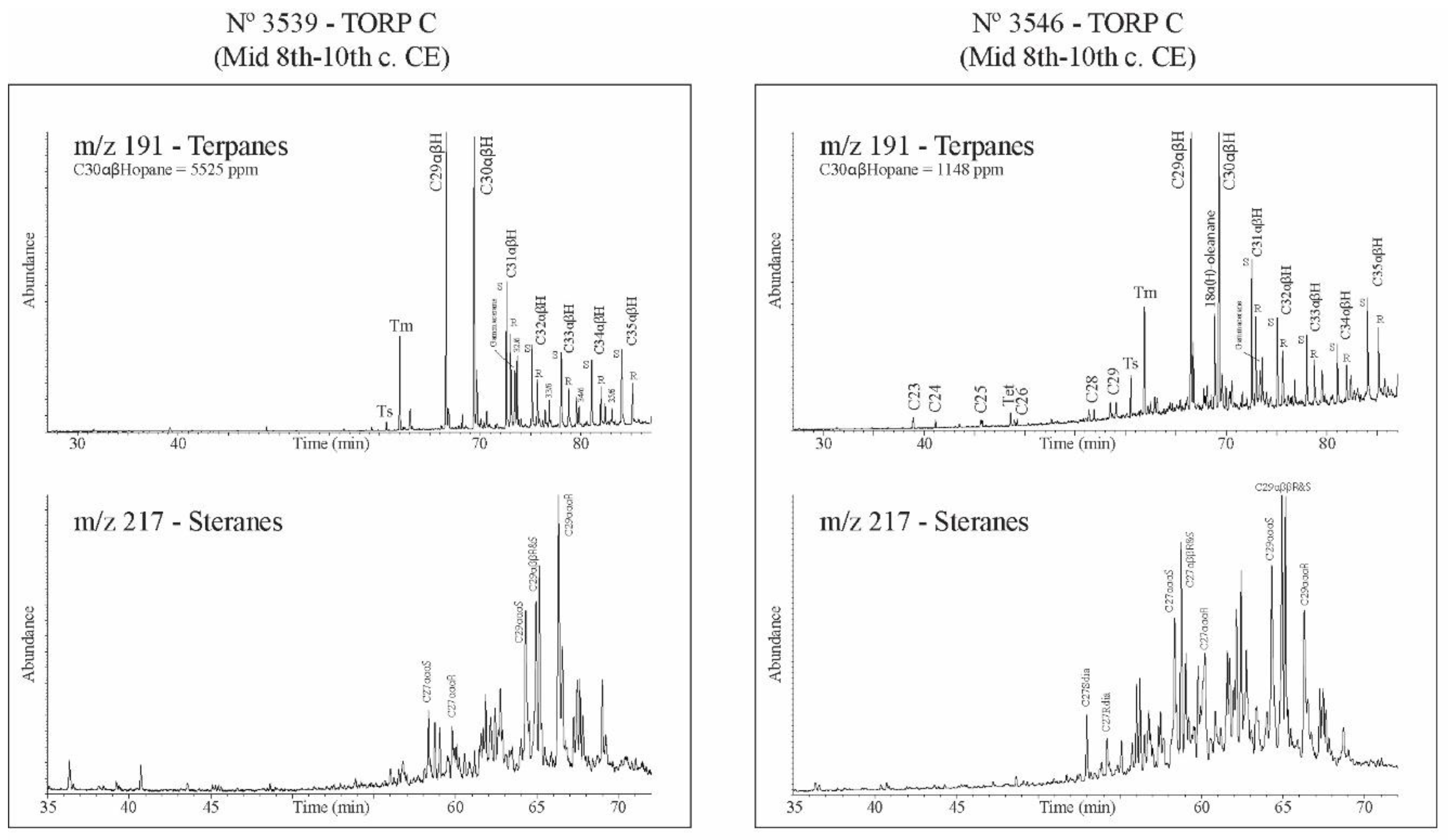

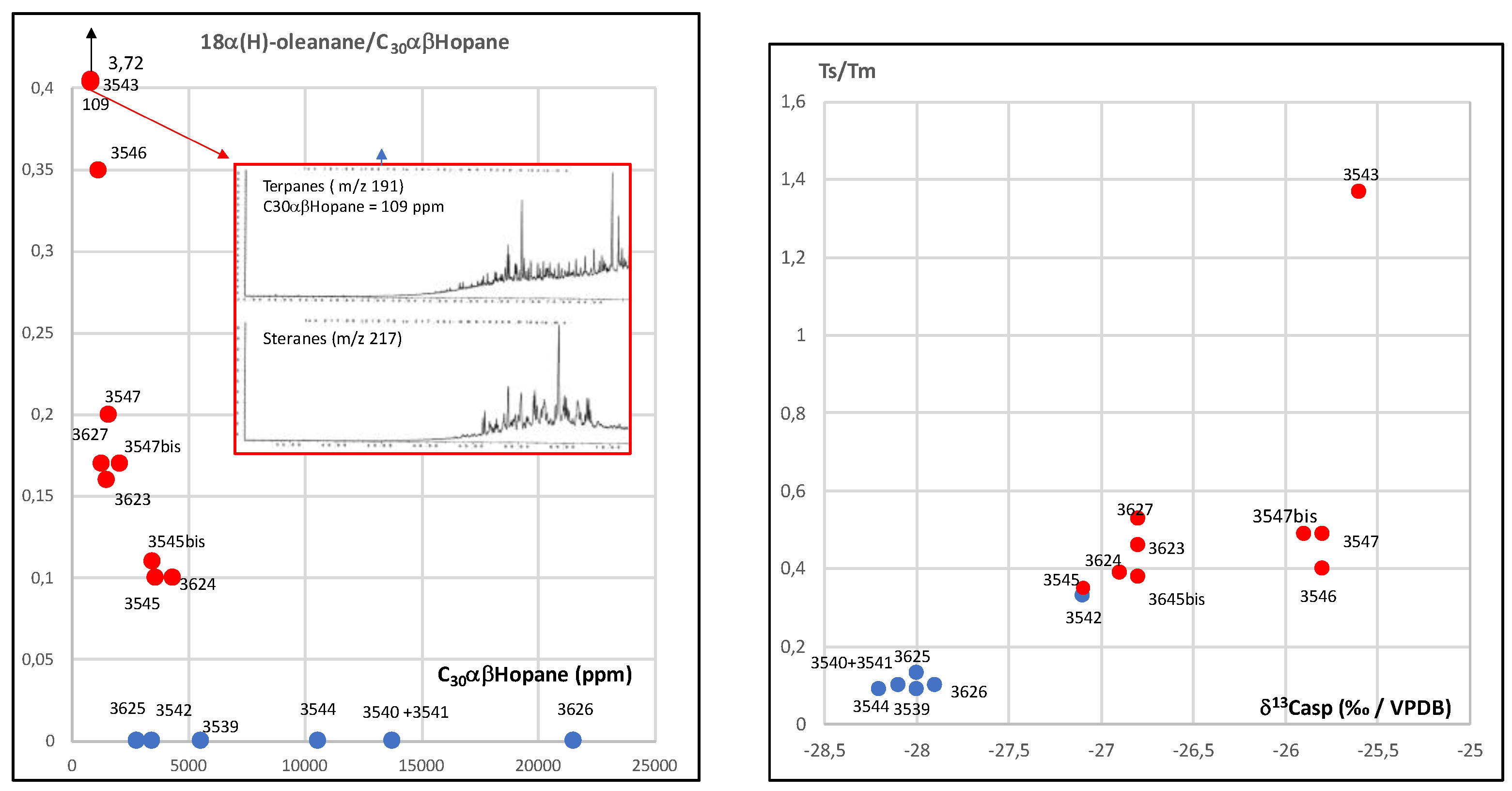

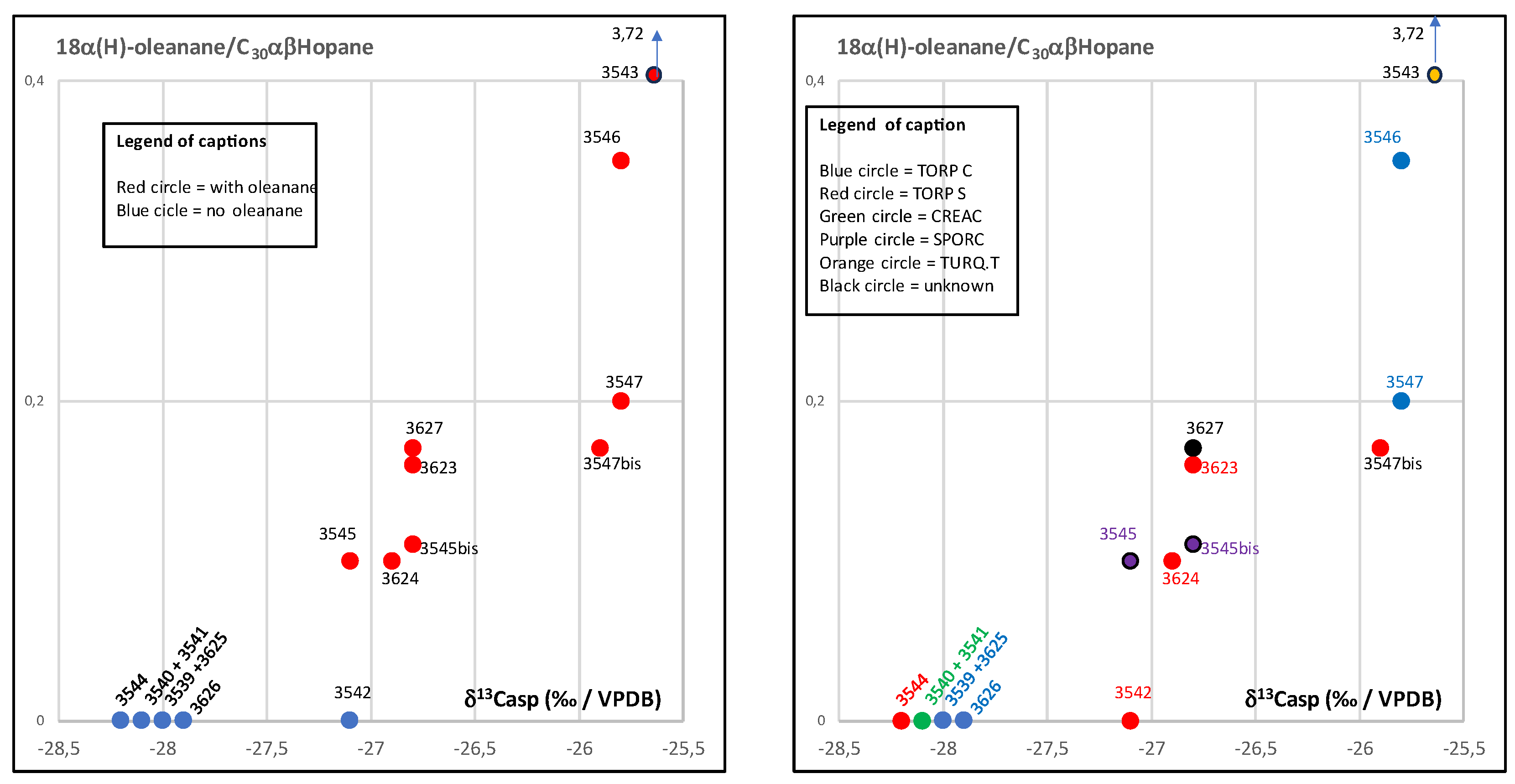

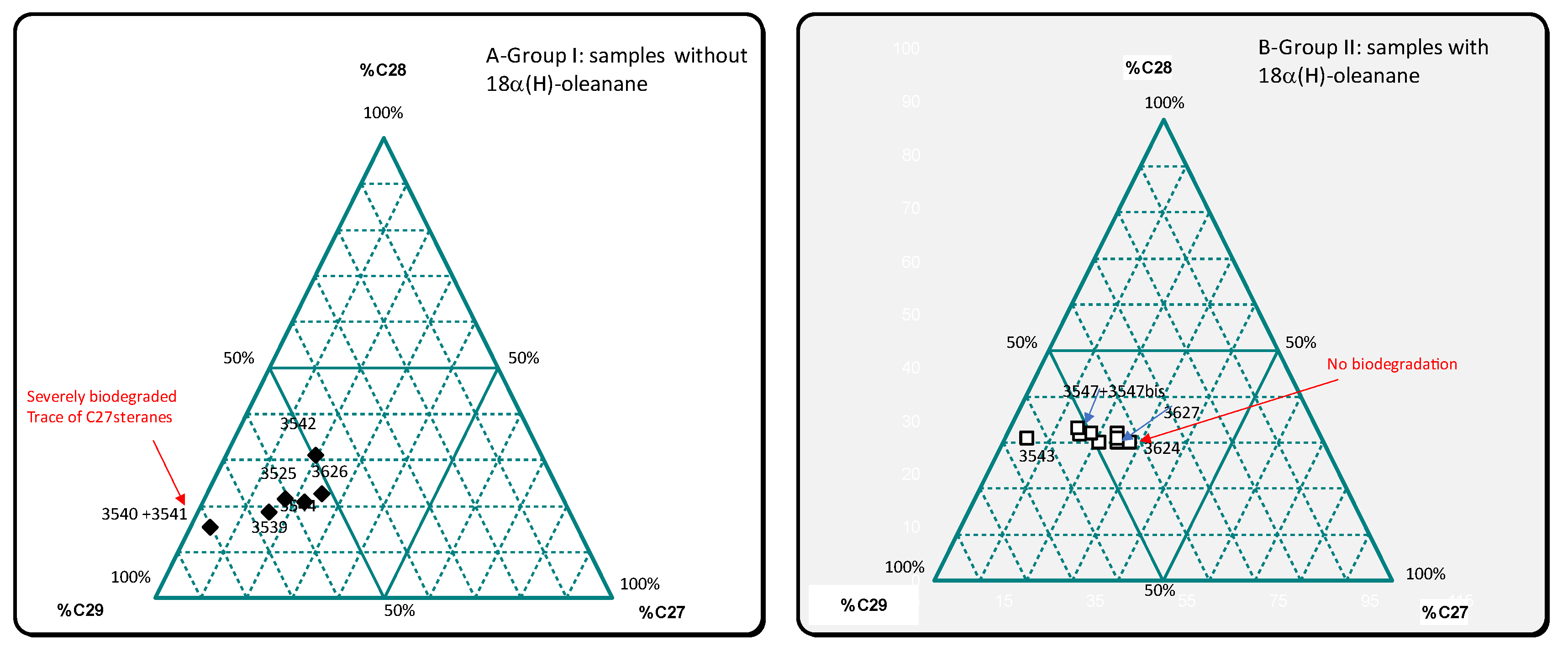

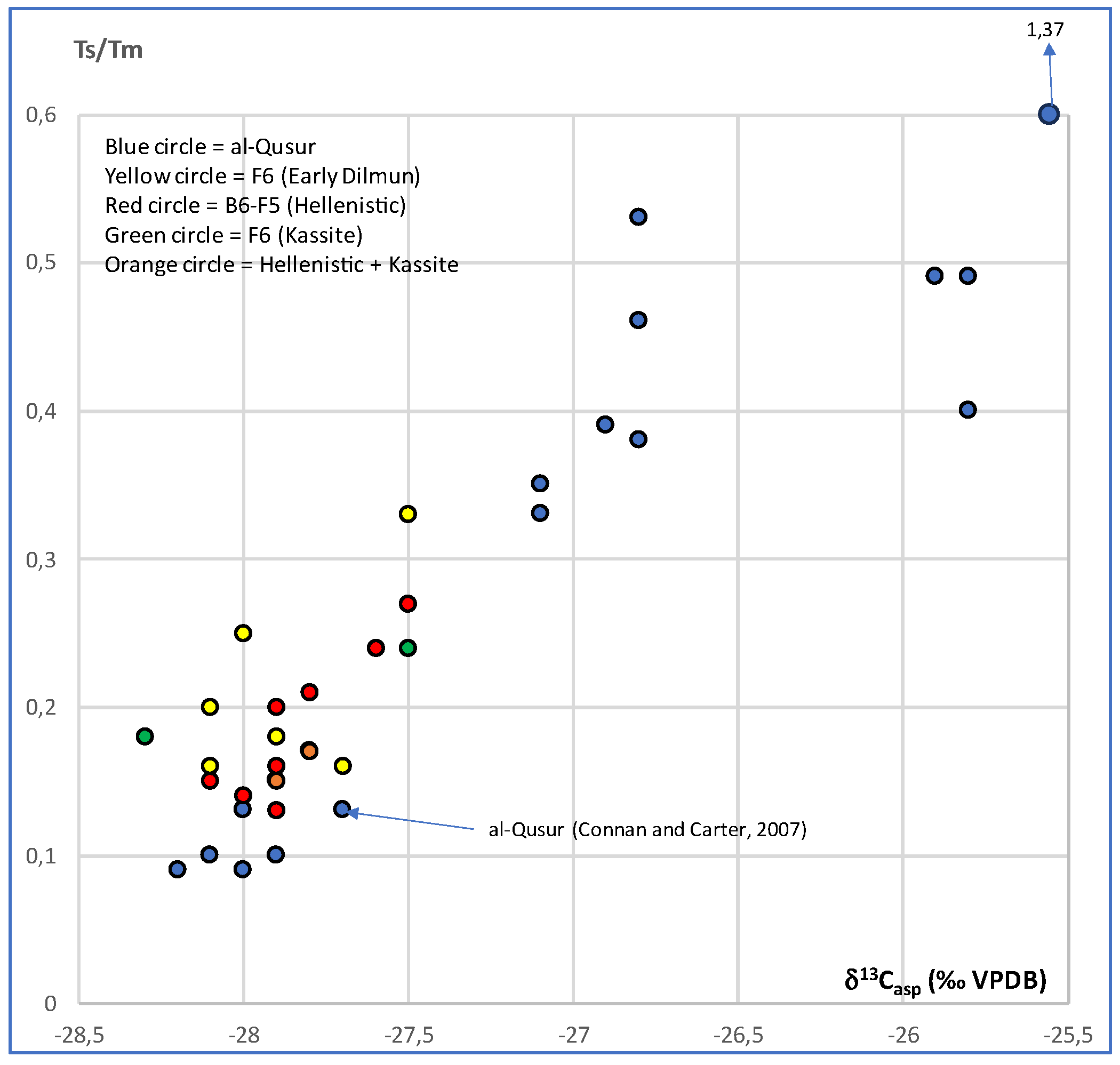

3.3. Biomarker Analysis

3.4. Detailed Geochemical Study of Samples No.3545 and 3545bis

4. Conclusions

References

- Bonnéric, J. Mission archéologique franco-koweïtienne de Faïlaka : Le monastère sassanido-islamique d’al-Qusur. Dossier « Prix Clio» 2018, 1-19.

- Bonnéric, J. Archaeological evidence of an early Islamic monastery in the centre of al-Qusur (Failaka Island, Kuwait). Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2021, 32, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnéric, J. Why islands ? Understanding the insular location of late Sasanian and Early Islamic Christian monasteries in the Arab-Persian Gulf. Durand, C. ; Marchand, J. ; Redon, B. ; Schneider, P. ; Networked spaces. The spatiality of networks in the Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean, 2022, 193-210. https://doi:10.4000/booksmomeditions.16271.

- Perrogon, R.; Bonnéric, J. A consideration on the interest of a pottery typology adapted to the late Sasanian and early Islamic monastery at al-Qusur (Kuwait). Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2021, 32, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Miceli, A. The site of Al-Qurainiyah: Topography and phases of an early Islamic coastal settlement on Failaka Island. Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2021, 32, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestman, S. Bushehr, Dashtestan and Siraf: the Transformation of the Maritime Trade Network in the Middle Persian Gulf In Simpson, St-J. (Ed.) Sasanian Archaeology: Settlements, Environment and Material Culture, Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, 2022, pp.

- Name:seth, [.C.G.

- Simpson, St-J. Sasanian Pottery: Archaeological Evidence for Production, Circulation and Diachronic Change In Simpson, St-J (Ed.) Sasanian Archaeology: Settlements, Environment and Material Culture, Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, 2022, pp.

- Kawamata, M. Telūl Hamediyāt near Tells Gubba and Songor: part III. Al-Rāfidān 12, 1991, pp. 249-260.

- Carter, R. , Connan, J., Priestman, S., Tomber, R., Torpedo jars from Sir Bani Yas, Abu Dhabi. Tribulus, Journal of the Emirates natural History Group 19, 2011, pp.162-163.

- Carter, R. Christianity in the Gulf during the first centuries of Islam. Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2008, 19, 71–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestman, S. Ceramic exchange and the Indian Ocean economy (AD 400-1275) Volume 1: Analysis, The British Museum, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Carvajal López, J.; Guérin, A. & Georgakopoulou, M. Petrographic analysis of ceramics from Murwab, an early Islamic site in Qatar Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 51, 2022, pp. 55-70.

- West, N.; Alexander, R.; Kagi, R.I. The use of silicalite for rapid isolation of branched and cyclic alkane fractions of petroleum. Org. Geochem. 1990, 15, 499–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Engel, M.H.; Jackson, R.B.; Priestman, S.; Vosmer, T.; Zumberge, A. Geochemical Analysis of Two Samples of Bitumen from Jars Discovered on Muhut and Masirah Islands (Oman). Separations 2021, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charrié-Duhaut, A.; Lemoine, S.; Adam, P.; Connan, J.; Albrecht, P. Abiotic oxidation of petroleum bitumens under natural conditions. Org. Geochem. 2000, 31, 977–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J.; Borrell, F.; Vardi, J.; Wolff, S.; Ortiz, S.M.; Engel, M.; Gley, R.; Zumberge, A. Geochemical analysis of bituminous samples from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site of Nahal Efe (Northern Negev, Israel): Earliest evidence in the region and an example of alteration of the Dead Sea bitumen. Org. Geochem. 2024, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connan, J. Le bitume dans l’Antiquité. Errance, Actes Sud, Arles, France, 2012, pp.272.

- Connan, J.; Carter, R. A geochemical study of bituminous mixtures from Failaka and Umm an-Namel (Kuwait), from the Early Dilmun to the Early Islamic period. Arab. Archaeol. Epigr. 2007, 18, 139–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample number | Country | Lab number | Location | Building | Context | Archaeological reference | Latitude | Longitude | Date range | Pottery type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kuwait | 3539 | al-Qusur | building B16 (monk's cell) | 5313 | QSR-12 A5/18 | 29°26'12"N | 48°20'52"E | Mid. 7th - early 9th CE | TORP-C |

| 2 | 3540 | building B20 (food processing), room R8 | 6067 | QSR-16-A4/25 | Late 8th - 10th c. CE | CREAC (HAR-CR17) ? / BUFF ? | ||||

| 3 | 3541 | building B20, room R8 | 6067 | QSR-16-A4/25 | Late 8th - 10th c. CE | CREAC (HAR-CR17) . / BUFF ? | ||||

| 4 | 3542 | building B14, courtyard | 7103 | QSR22-A5/0002 | Mid. 7th - early 9th c. CE | TORP-S | ||||

| 5 | 3543 | building B1 | 4 | QSR07/2100 | Mid.7th - mid.8th c. CE | TURQ.T (TUR-CR7) | ||||

| 6 | 3544 | building B14, room R1 | 7162 | QRS2022-A5/0001 | Mid. 7th - early 9th c. CE | TORP-S | ||||

| 7 | 3545 | building B20 (food processing), room R8 | 6067 | QRS16-A4/57 | Late 8th - 10th c. CE | SPORC | ||||

| 8 | 3546 | building B23 (refectory) | 5635 | QSR15-A4/243 | Mid. 8th - 10th c. CE | TORP-C | ||||

| 9 | 3547 | building B23 (refectory) | 5635 | QSR15-A4/243 | Mid. 8th - 10th c. CE | TORP-C | ||||

| 26 | 3623 | building B14, courtyard | 7177 | QSR23- A5-B14-7177 | Mid. 7th - early 9th c. CE | TORP-S | ||||

| 27 | 3624 | building B19, room R2 | 6854 | QSR19- A5-U.97-6854 | Mid. 7th - early 9th c. CE | TORP-S | ||||

| 28 | 3625 | building B19, courtyard | 6862 | QSR19-A5-U.21-22-6862 | Mid. 8th - (early) 9th c. CE | TORP-C | ||||

| 29 | 3626 | building B20 (food processing), room R5 | / | QSR23-A4-B20 -U.63 R15 | Mid. 8th - (early) 9th c. CE | TORP-C | ||||

| 30 | 3627 | building B25, room R4 | 7701 | QSR23-A6-B25-u.140-7701 | / | / |

| sample number | country | lab number | location | %EO | %Sat | %aro | %HC | %NSO | %ASP | %Pol | d13Csat | d13Caro | d13CNSO | d13Casp | dDNSO | dDasp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kuwait | 3539 | al-Qusur | 13,8 | 1,4 | 2 | 3,4 | 8,7 | 87,9 | 96,6 | -28,5 | -27,4 | -28 | -28 | -84 | -82 |

| 2 | 3540 +3541 | 13,4 | 4,5 | 5,2 | 9,7 | 18,7 | 71,6 | 90,3 | -27,4 | -25,9 | -28,1 | -28,1 | -91 | -88 | ||

| 4 | 3542 | 53,5 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9,5 | 83,5 | 93 | -27,5 | -26,4 | -26,5 | -27,1 | -83 | -74 | ||

| 5 | 3543 | 21 | 4 | 3,1 | 7,1 | 14,9 | 78 | 92,9 | -27,1 | -26 | -26,1 | -25,6 | -87 | -84 | ||

| 6 | 3544 | 15 | 1,7 | 3,2 | 4,9 | 12 | 83,1 | 95,1 | -28,8 | -27,3 | -28,1 | -28,2 | -86 | -71 | ||

| 7 | 3545 | 34,3 | 3,9 | 2,7 | 6,6 | 7,5 | 85,9 | 93,4 | -27,2 | -26,5 | -26,9 | -27,1 | -85 | -73 | ||

| 3545bis | 36,7 | 3,4 | 2,5 | 5,9 | 7,5 | 86,6 | 94,1 | -27,6 | -26,6 | -26,8 | -26,8 | -82 | -74 | |||

| 8 | 3546 | 22,1 | 3,3 | 3,5 | 6,8 | 7,1 | 86,1 | 93,2 | -27 | -25,9 | -26,2 | -25,8 | -89 | -69 | ||

| 9 | 3547 | 32,4 | 2,7 | 2,7 | 5,4 | 10,2 | 84,4 | 94,6 | -27 | -26 | -26,3 | -25,8 | -108 | -72 | ||

| 3547bis | 28,3 | 3,2 | 3 | 6,2 | 12,2 | 81,6 | 93,8 | -27 | -25,8 | -26,5 | -25,9 | -101 | -79 | |||

| 26 | Kuwait | 3623 | al-Qusur | 42,8 | 4,1 | 2,6 | 6,7 | 7,5 | 85,8 | 93,3 | -27,5 | -26,2 | -26,8 | -26,8 | -80 | -74 |

| 27 | 3624 | 41,5 | 4,5 | 2,2 | 6,7 | 5,3 | 88 | 93,3 | -27,2 | -26,3 | -26,7 | -26,9 | -77 | -77 | ||

| 28 | 3625 | 5,2 | 1,7 | 2,2 | 3,9 | 12,9 | 83,2 | 96,1 | -27,2 | -27,7 | -28,2 | -28 | -103 | -74 | ||

| 29 | 3626 | 1,7 | 1,4 | 1,4 | 2,8 | 8,4 | 88,8 | 97,2 | -28,7 | -27,8 | -27,9 | -27,9 | -83 | -72 | ||

| 30 | 3627 | 32,2 | 4,1 | 2,6 | 6,7 | 5,8 | 87,5 | 93,3 | -27,4 | -26,3 | -26,8 | -26,8 | -81 | -68 |

| Lab number | C30abHopane (ppm) | Tet/C23 | C29/H | Ol/H | C31R/H | GA/C31R | GA/C30H | C35S/C34S | Ster/Terp | Dia/Reg | %C27 | %C28 | %C29 | C2920S/20R | C29abbS/C29aaaR | Ts/Tm | tricyclics | terpanes | steranes | C27diasteranes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3539 | 5525 | 1,27 | 1,02 | 0 | 0,32 | 0,59 | 0,19 | 1,14 | 0,04 | 0,12 | 15,5 | 18,8 | 65,7 | 0,55 | 0,68 | 0,09 | almost absent | well preserved | biodegraded -C27<C28<C29 | |

| 3540+3541 | 13768 | 3,41 | 1,19 | 0 | 0,23 | 0,56 | 0,13 | 0,87 | 0,08 | 0,08 | 4,3 | 15,5 | 80,2 | 0,38 | 0,81 | 0,1 | almost absent | preserved? | severely biodegraded-C27 | |

| 3542 | 3428 | 4,15 | 1,35 | 0 | 0,3 | 0,55 | 0,17 | 1,03 | 0,13 | 0,19 | 19,5 | 31,2 | 49,3 | 0,71 | 0,99 | 0,33 | almost absent | preserved? | biodegraded | |

| 3543 | 109 | 0,53 | 1,65 | 3,72 | 0,43 | 1,07 | 0,46 | 3,7 | 0,72 | 0,28 | 4,8 | 30,9 | 64,4 | 11,38 | 2,6 | 1,37 | absent | severely biodegraded | severely biodegraded- | |

| 3544 | 10580 | 3,44 | 0,94 | 0 | 0,27 | 0,58 | 0,16 | 1,08 | 0,09 | 0,04 | 22,3 | 21 | 56,8 | 0,65 | 1,06 | 0,09 | absent | preserved | slightly biodegraded | |

| 3545 | 3563 | 1,15 | 0,98 | 0,1 | 0,31 | 0,36 | 0,11 | 1,15 | 0,36 | 0,69 | 25,1 | 29,9 | 45 | 0,76 | 1,37 | 0,35 | present low | preserved | preserved | present |

| 3545bis | 3426 | 1,79 | 1,01 | 0,11 | 0,33 | 0,35 | 0,12 | 1,25 | 0,33 | 0,86 | 21,1 | 30 | 48,9 | 1,05 | 1,52 | 0,38 | present low | preserved | preserved | present |

| 3546 | 1148 | 1,26 | 1,01 | 0,35 | 0,32 | 0,36 | 0,12 | 1,72 | 0,75 | 0,75 | 18,3 | 32 | 49,7 | 1,18 | 1,71 | 0,4 | present low | preserved | preserved | present |

| 3547 | 1569 | 1,24 | 0,94 | 0,2 | 0,38 | 0,29 | 0,11 | 1,26 | 0,36 | 0,92 | 15,9 | 31,8 | 52,2 | 1,19 | 1,71 | 0,49 | present low | preserved | slightly biodegraded-C29abbR -C27abbR biodegraded | present |

| 3447bis | 2027 | 1,85 | 0,94 | 0,17 | 0,36 | 0,3 | 0,11 | 1,19 | 0,34 | 0,87 | 14,8 | 33,1 | 52,1 | 1,16 | 1,79 | 0,49 | almot absent | preserved | slightly biodegraded-C29abbR -C27abbR biodegraded | present |

| 3623 | 1464 | 1,1 | 1,19 | 0,16 | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,12 | 1,3 | 0,82 | 1,09 | 24,1 | 32 | 43,9 | 1,28 | 2,05 | 0,46 | almost absent | preserved | slightly biodegraded-C29abbR -C27abbR biodegraded | present |

| 3624 | 4313 | 1,46 | 1,06 | 0,1 | 0,32 | 0,31 | 0,1 | 1,05 | 0,33 | 0,81 | 27,8 | 30 | 42,2 | 0,88 | 1,42 | 0,39 | almost absent | preserved | preserved | abundant |

| 3625 | 2786 | 2,14 | 1,04 | 0 | 0,35 | 0,73 | 0,26 | 1,18 | 0,04 | 0,59 | 17,5 | 21,8 | 60,7 | 0,71 | 0,74 | 0,13 | absent | preserved | biodegraded-C27<C28<C29 | present low |

| 3626 | 21510 | 3,62 | 1,13 | 0 | 0,25 | 0,54 | 0,14 | 0,9 | 0,08 | 0,05 | 24,9 | 22,9 | 52,2 | 0,47 | 0,77 | 0,1 | absent | preserved | biodegraded-C27<C28<C29 | absent |

| 3627 | 1244 | 0,58 | 1,23 | 0,17 | 0,32 | 0,42 | 0,13 | 1,55 | 0,7 | 1,09 | 24,6 | 30,8 | 44,6 | 1,18 | 1,44 | 0,53 | present | preserved? | preserved | abundant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).