Graphical Abstract

Lay Summary:

Quantum dots are tiny, crystal-like particles with remarkable light-emitting properties that can transform healthcare and dentistry. By controlling their size, scientists can engineer them to glow in vibrant colors, enabling doctors and dentists to capture detailed images of tissues at the cellular level. They can also attach medications or biomolecules to these dots for more precise drug delivery, reducing side effects. Moreover, quantum dots strengthen dental materials and combat harmful bacteria. As research refines their safety and effectiveness, these particles hold great promise for advancing diagnostics and treatments across medicine and dentistry. Ultimately, such innovations could reshape the future of personalized healthcare worldwide.

Future Works:

Further research will optimize the safety and large-scale production of QDs, paving the way for advanced clinical trials. Innovations in surface modifications, bioimaging techniques, and regenerative dentistry will expand their applications. Ultimately, sustainable manufacturing and refined toxicity profiles will ensure QDs become mainstream tools in precision medicine, benefitting patients worldwide.

Key Points:

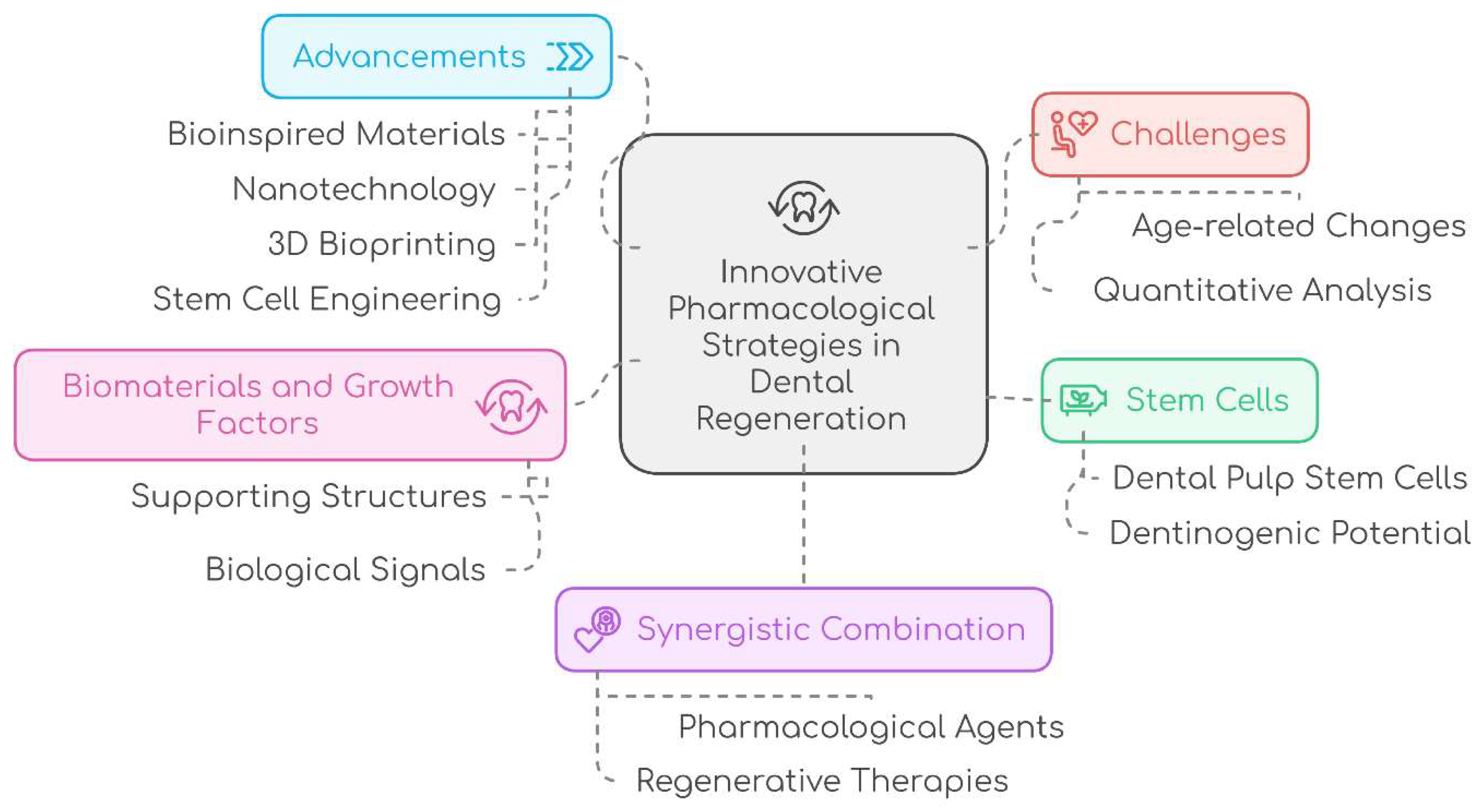

Innovative Integration: Combining bioengineering advancements with pharmacological strategies to enhance dental tissue regeneration.

Stem Cell Potential: Leveraging dental pulp stem cells and growth factors to overcome limitations of conventional therapies.

Technological Advancements: Employing nanotechnology, bioinspired materials, and 3D bioprinting to drive transformative progress in regenerative dentistry.

Personalized Therapies: Developing tailored regenerative solutions through the synergistic use of pharmacological agents and advanced therapies to revolutionize dental care.

Introduction

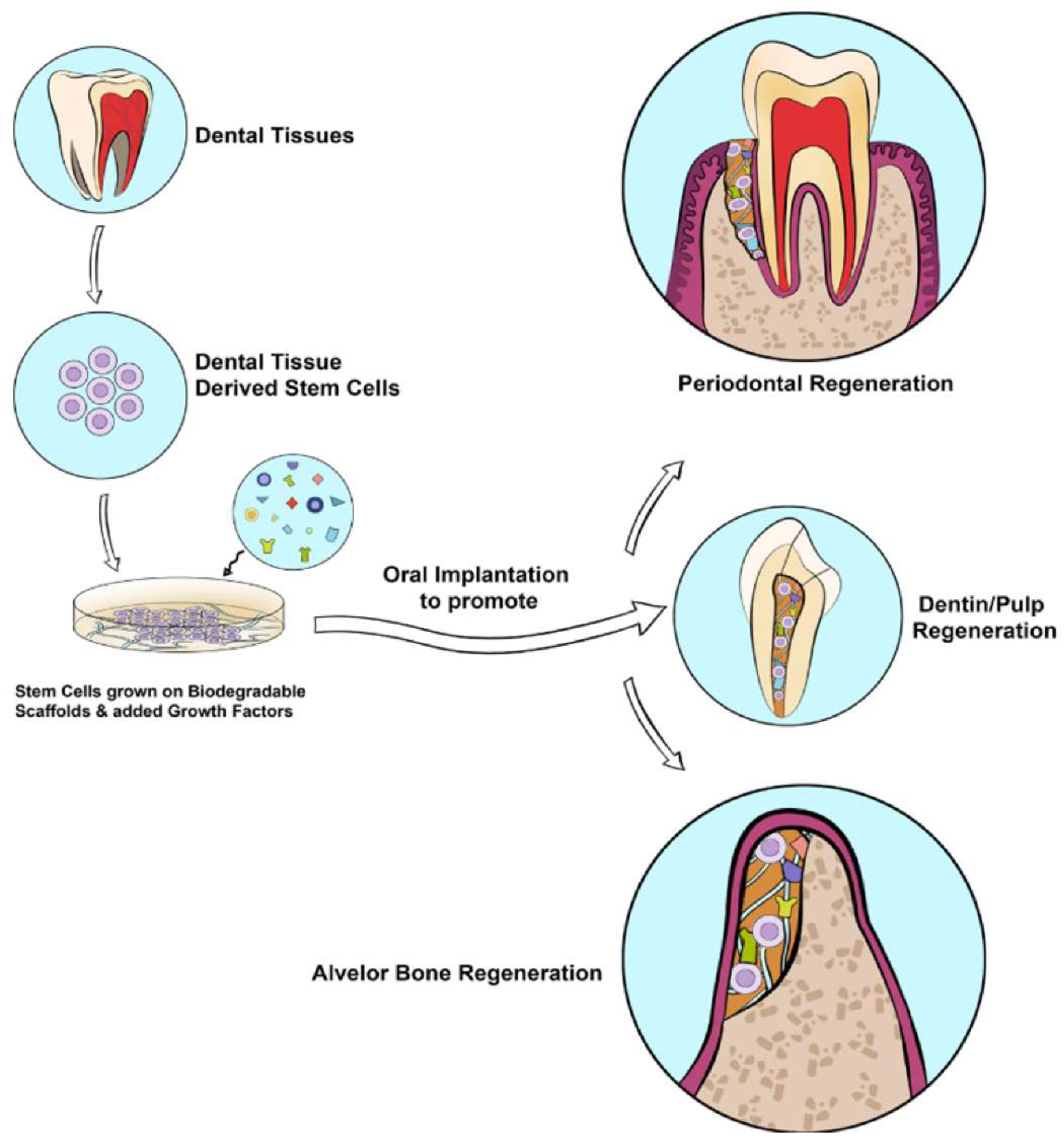

Embarking on a transformative era, regenerative approaches in dental pharmacology constitute a burgeoning field dedicated to advancing biomedical technologies, offering innovative solutions for achieving optimal bone and dental tissue regeneration and repair within the realm of dentistry. The exploration of this dynamic field aims to elucidate the pivotal role of regenerative strategies in enhancing oral health outcomes. Tissue regeneration stands as a cornerstone in modern dentistry, addressing the intricate challenges associated with periodontal tissue regeneration, bone grafting, and wound healing in the domains of oral surgery and implantology. The ultimate goal is to replicate the morphological and functional characteristics of native tissues. Dental defects, pervasive and impactful on patients' health and quality of life, pose significant financial challenges for effective restoration. Conventional therapies merely impede disease progression without the capacity to regenerate lost tissue, often accompanied by drawbacks like donor site morbidity, infection, and unpredictable outcomes. In response to these limitations, regenerative medicine emerges as a transformative discipline, leveraging stem cells, biomaterials, and growth factors to restore both the form and function of damaged tissues and organs.

The unique promise of stem cells derived from dental tissues takes center stage in the pursuit of regenerative therapy for maxillofacial bone defects. These cells possess remarkable versatility, capable of differentiating into diverse cell types and secreting bioactive molecules that orchestrate crucial processes such as inflammation modulation, angiogenesis, and tissue repair. The potential inherent in these stem cells offers a tantalizing prospect for addressing the inadequacies of current dental defect treatments. Moreover, recognizing the paramount importance of effective pharmacological management becomes imperative, particularly in mitigating pain and inflammation post stem cell implantation surgery. Such management not only influences the survival and function of transplanted stem cells but also significantly shapes the overall outcome of cell therapy. In this intricate interplay of cutting-edge science and therapeutic application, regenerative approaches in dental pharmacology stand poised to revolutionize the landscape of dentistry, offering innovative solutions for comprehensive tissue regeneration and repair [

1]. The objectives of this review encompass a comprehensive analysis of growth factors, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), and stem cell-based therapies in the context of dental regeneration.

Delving into the realm of growth factors, this review seeks to unravel their intricate roles in promoting tissue regeneration, with a particular focus on their applications in periodontal tissue regeneration, bone grafting, and wound healing. The subsequent sections dedicated to PRP and PRF aim to dissect the biological properties of these regenerative agents, exploring their potential and efficacy in dental pharmacology. Stem cell-based therapies, another frontier in regenerative dentistry, are scrutinized for their potential applications in fostering tissue regeneration.

While progressing through these regenerative modalities, it becomes imperative to address the challenges and limitations inherent in the field. The examination meticulously identifies and addresses these challenges, offering insights into potential strategies to overcome them. Moreover, it extends its gaze towards the future, illuminating emerging trends that hold promise in reshaping the landscape of dental pharmacology.

In essence, this research review endeavors to weave together the intricate tapestry of regenerative approaches in dental pharmacology. By combining historical perspectives, contemporary insights, and future trajectories, it aspires to provide a comprehensive and scholarly exploration of this evolving field. In the course of this investigation, the review aims to contribute to the broader understanding of regenerative dentistry, ultimately influencing the standards and practices that define modern approaches to tissue regeneration in dentistry.

Growth Factors in Dental Regeneration

Regenerative endodontics focuses on revitalizing and restoring the functionality of the dentin-pulp complex, moving away from the traditional method of using bioinert materials to fill root canals. A variety of growth factors intricately regulate essential cellular processes, such as migration, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, across multiple cell types that are key to dentin-pulp regeneration. These cell types include odontoblasts, interstitial fibroblasts, vascular endothelial cells, and emerging nerve fibers.

Signaling molecules, such as growth factors and cytokines, are crucial in controlling cell behavior through intracellular communication. Growth factors, which are proteins or polypeptides, bind to specific receptors on target cells, triggering a series of intracellular signals and acting either through autocrine or paracrine pathways. Cytokines, often referred to as immunomodulatory proteins or polypeptides, sometimes overlap with growth factors in their actions. Unlike hormones, which typically have widespread effects on target cells throughout the body, growth factors and cytokines generally influence target cells in a localized manner [

2].

Different types of growth factors used in dental pharmacology

In dental pharmacology, growth factors are essential for regulating cellular functions and promoting tissue regeneration. Notable examples of these growth factors include bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2 or bFGF), and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) [

2].

BMPs play a vital role in the regeneration of dentin and are considered promising candidates for endodontic therapy [

2].

FGF-2 is well-known for its regulatory effects on pulp repair and regeneration, making it a widely studied growth factor in dentistry [

3]. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), released by platelets, has shown effectiveness in promoting both angiogenesis and cell proliferation. At the site of injury, PDGF stimulates the chemotaxis and proliferation of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells. After trauma, hemorrhage leads to the formation of a blood clot in the dental pulp, during which platelets release α-granules containing PDGFs. These growth factors attract neutrophils and macrophages, which are essential in the early stages of wound healing, producing additional signaling molecules that facilitate granulation tissue formation [

2]. The significance of these growth factors is paramount in advancing tissue repair and regeneration within the realm of dental pharmacology.

BMPs (Bone morphogenetic proteins).

BMP2, BMP4, BMP7, and BMP11 are clinically important due to their role in promoting mineralization. Application of human recombinant BMP2 encourages dental pulp cells to differentiate into odontoblasts, leading to increased expression of dentin sialophosphoproteins (DSPPs) at the mRNA level. BMP2 also enhances alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, though it does not affect the proliferation of dental pulp cells. The regulation of DSPP expression and the differentiation of dental pulp cells into odontoblasts by BMP2 likely occurs through the activation of nuclear transcription factor Y signaling. Additionally, BMP2 promotes the differentiation of dental pulp stem/progenitor cells into odontoblasts in both in vitro and in vivo environments. When recombinant BMP2 or BMP4 is applied in capping materials over amputated canine pulp, dentin formation is initiated. When BMPs are incorporated into a collagen matrix, osteodentin forms in amputated canine pulps. Similarly, bovine dental pulp cells exposed to BMP2 and BMP4 differentiate into preodontoblasts. BMP7, also known as osteogenic protein-1, stimulates dentin formation when applied to amputated dental pulp in macaque teeth [

2,

4].

BMPs possess the ability to mobilize and stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of host cell populations, making them highly valuable for promoting tissue regeneration [

5].

FGF-2

FGF-2 (fibroblast growth factor 2) has shown effectiveness in enhancing the regeneration of periodontal tissues compared to control groups. During the early stages of wound healing, soluble factors like FGF-2 are released, targeting specific cells or pathways to accelerate the healing process. FGF-2 has yielded promising results in regenerating bone and periodontal ligament-like tissues when integrated into micropatterned scaffolds containing immobilized growth factor genes [

6].

In relation to dental pulp cells, FGF-2 has been found to promote their migration. In a transwell migration assay, significantly more dental pulp cells are attracted by bFGF (FGF-2) into a 3D collagen gel compared to control groups without cytokines and BMP7. FGF-2 also enhances the proliferation of dental pulp cells without inducing differentiation. However, when combined with TGFβ1, FGF-2 induces the differentiation of dental pulp cells into odontoblast-like cells and synergistically boosts TGFβ1's effect on odontoblast differentiation.

Moreover, applying FGF-2 to exposed dental pulp in rat molars results in early vascular invasion and cell proliferation during the wound healing process. FGF-2 also promotes the formation of reparative dentin or dentin particles in the exposed pulp. These findings emphasize the potential of FGF-2 in promoting periodontal tissue regeneration, stimulating dental pulp cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation, as well as facilitating vascular invasion and dentin formation in cases of dental pulp injury or exposure [

2].

PDGF

PDGF (Platelet-Derived Growth Factor), released by platelets, plays a critical role in promoting angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels) and cell proliferation. It exists in several isoforms, including homodimers AA, BB, CC, and DD, as well as a heterodimer, PDGF-AB. These PDGF dimers bind to two types of cell surface receptors, PDGFRα and PDGFRβ.

During injury, PDGF contributes to the chemotaxis (movement) and proliferation of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells at the site of trauma. After hemorrhage, blood clot formation occurs in the dental pulp, and platelets within the clot release α-granules containing PDGFs. These factors attract neutrophils and macrophages, which are crucial for early wound healing as they secrete additional signaling molecules necessary for the development of granulation tissue.

However, PDGFs seem to have a limited effect on the formation of dentin-like nodules in dental pulp cells isolated from rat lower incisors. Although the PDGF-AB and PDGF-BB isoforms increase the expression of dentin sialoprotein (DSP), they do not significantly influence the formation of dentin-like nodules. Nevertheless, PDGFs do stimulate cell proliferation and the synthesis of dentin matrix proteins. Interestingly, they tend to inhibit alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in dental pulp cells cultured in vitro. In conclusion, PDGF released by platelets plays a key role in promoting angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and immune cell recruitment during early wound healing. While it enhances cell proliferation and the synthesis of dentin matrix proteins, its impact on dentin-like nodule formation and ALP activity in dental pulp cells is limited [

2].

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in Dental Regeneration

Explain the concept of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and its preparation methods.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an innovative technique for tissue regeneration, widely used in various surgical fields such as head and neck surgery, otolaryngology, cardiovascular surgery, and maxillofacial surgery. PRP is typically prepared in gel form by combining PRP, which is derived from centrifuged autologous whole blood, with thrombin and calcium chloride. The resulting PRP gel contains high concentrations of platelets and retains native levels of fibrinogen, which enhances tissue repair and regeneration. Platelets are essential in initiating the wound healing process, quickly responding to injury. In addition to their role in clotting, platelets release vital growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) 1 and 2, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). These growth factors promote angiogenesis, aiding the healing of both soft and hard tissues [

7].

The clinical use of PRP hinges on the high concentration of growth factors released from the alpha granules in platelets, as well as the secretion of proteins that contribute to cellular-level healing. The quality and functionality of platelets are significantly influenced by the PRP preparation method. However, due to wide variation in protocols regarding factors such as rotational speed, centrifugation time, blood volume, and anticoagulant use, standardization across studies remains difficult, complicating direct comparisons. PRP can be prepared using either one-step or two-step centrifugation techniques. The Anitua plasma-rich growth factor protocol is the most commonly referenced one-step procedure, producing PRP with fewer leukocytes and lower platelet concentration compared to other methods. In the typical two-step protocol, whole blood is centrifuged, forming three distinct layers: a bottom layer of red blood cells, a central "buffy layer" containing white blood cells, and a top layer with platelets suspended in plasma. The top layer, along with part or all of the buffy layer (depending on the desired leukocyte content), is transferred to a new tube for a second centrifugation, resulting in a platelet-rich pellet.

A consistent centrifugation rate is crucial to maximizing platelet concentration in PRP preparation, and it is important to apply the right centrifugation force to avoid damaging the fragile platelets. Platelets can be activated prior to application to the target tissue, though there is no consensus on whether pre-activation is necessary or on the best activating agent. Common activators include thrombin and calcium chloride (CaCl2), both of which induce platelet aggregation and degranulation, leading to the release of growth factors [

8].

Review studies and clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of PRP in periodontal tissue regeneration, bone grafting, and wound healing in oral surgery and implantology.

Whitman et al. introduced Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) into oral and maxillofacial surgery in 1997. Rich in growth factors, PRP has a significant impact on wound healing, implant placement, and reconstructive surgery for mandibular defects. Its use leads to marked improvements in local conditions, especially in the alveolar socket following tooth extraction, aiding tissue regeneration and minimizing complications. PRP enhances soft tissue healing by increasing collagen content, promoting angiogenesis, and strengthening early wound integrity. Furthermore, PRP effectively stimulates bone regeneration, particularly at the distal surface of the mandibular second molar after the extraction of impacted third molars.

Research has demonstrated PRP's effectiveness in accelerating bone regeneration during the early phases, typically within 3 to 6 weeks following oral surgery. Recent in vitro studies have shed light on PRP's cellular mechanisms, illustrating its capacity to induce chemotactic migration and proliferation of human mesenchymal cells in a dose-dependent manner, while maintaining their ability to form bone tissue. However, despite promising results from many clinical trials, there are conflicting findings regarding PRP's efficacy in promoting bone formation and healing, particularly highlighted by Ranly et al. noted reduced osteoinductivity of demineralized bone matrix following PRP treatment in immunocompromised mice. These findings underscore the need for further well-designed clinical trials to establish the evidence supporting PRP's regenerative potential in oral surgery.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is crucial in dental and oral surgeries, supporting various procedures such as ablative surgeries, mandibular reconstruction, alveolar cleft repair, and the treatment of periodontal defects. It improves flap adaptation, hemostasis, and sealing compared to primary closure alone. PRP is also being explored for its potential in managing conditions like bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) and avascular necrosis, with the goal of accelerating wound healing and promoting bone maturation.

Tooth extractions, especially of impacted molars, often result in considerable postoperative pain and bleeding, particularly in patients on anticoagulant therapy. Techniques such as using a fibrin sponge and LASER biostimulation are employed to reduce discomfort and enhance tissue repair. PRP is rich in growth factors that promote fibrin clot formation, fibroblast proliferation, and collagen synthesis, thus aiding wound healing and the regeneration of periodontal tissue. While its effectiveness in improving clinical attachment levels in chronic periodontitis is still uncertain, PRP shows promise in alleviating gingival recession. When combined with graft materials for treating intrabony defects, PRP has shown positive adjunctive effects, though results can vary.

In bone surgery, the application of PRP along fracture lines enhances bone regeneration. However, its efficacy in sinus lift procedures and maxillary sinus augmentation remains a topic of debate, with mixed results regarding improvements in bone density and new bone formation. In implant surgery, coating implant surfaces with PRP has been found to improve osseointegration and increase patient satisfaction, particularly in reconstructive jaw surgery and in the regeneration of alveolar bone following tooth extraction. PRP significantly enhances the quality of newly formed bone in dental bone grafting, resulting in improved stability of dental implants and reduced risk of implant failure. Furthermore, PRP dental bone grafting enhances the aesthetics of a patient's smile by stimulating the growth of new bone tissue, thereby enhancing the shape and contour of the jawbone and resulting in a more natural and appealing smile [

7,

8,

9].

Discuss the biological properties of PRF and its applications in dental regeneration.

The development of bioactive surgical additives aimed at modulating inflammation and speeding up the healing process poses a significant challenge in clinical research. Healing is a complex process that involves cellular organization, chemical signaling, and the extracellular matrix, all of which are essential for effective tissue repair. Although our understanding of the healing process is still evolving, it is well established that platelets play a crucial role in both hemostasis and wound healing [

10]. In the 1970s, researchers uncovered the regenerative potential of platelets, revealing that they contain growth factors that promote collagen production, stimulate cell division, facilitate the formation of new blood vessels, attract additional cells to the injury site, and initiate cell differentiation [

11].

A recent development in oral surgery involves the use of platelet concentrates, such as Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF), for in vivo tissue engineering applications. These concentrates, which are concentrated suspensions of growth factors derived from platelets, function as localized bioactive surgical additives that stimulate wound healing and promote tissue regeneration. The initial introduction of Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF) in oral and maxillofacial surgery was pioneered by Choukroun et al [

12]. in 2001. PRF is an autologous leukocyte-platelet-rich fibrin matrix known for its tetra-molecular structure, which includes platelets, cytokines, and stem cells. It acts as a biodegradable scaffold that aids in the formation of microvasculature and guides the migration of epithelial cells to its surface. Moreover, PRF serves as a carrier for cells involved in tissue regeneration and provides a sustained release of growth factors over a period of 1 to 4 weeks. This extended release of growth factors creates an environment conducive to significant wound healing over a considerable duration. Several studies have shown that PRF possesses significant potential as a biomaterial for promoting bone and soft tissue regeneration. It has been observed that PRF can be used independently or in conjunction with bone grafts to facilitate hemostasis, stimulate bone growth, and support the maturation of tissues during surgical procedures. Notably, PRF has been found to promote these regenerative processes without causing inflammatory reactions. PRF has the potential to act as a resorbable membrane in guided bone regeneration (GBR) procedures. Its role would involve preventing the infiltration of undesired cells into the bone defect while creating a suitable environment for the migration of osteogenic and angiogenic cells. Additionally, PRF allows for the mineralization of the underlying blood clot. However, regular PRF membranes tend to degrade quickly within 1-2 weeks. By cross-linking the fibers, enhanced resistance against enzymatic degradation can be achieved, resulting in a more stable membrane throughout the healing period.

Both in vitro and in vivo studies have consistently demonstrated positive and safe outcomes with the use of Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF), whether used alone or in combination with other biomaterials, without any conflicting findings reported. PRF offers several advantages and potential applications across both medical and dental fields. Currently, platelet-rich fibrin is regarded as an accepted minimally invasive technique, known for its low risks and favorable clinical results [

10].

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in Dental Regeneration

Platelets have been recognized for their regenerative capabilities in various medical and dental applications, including dental regeneration. They play a crucial role in hemostasis and wound healing [

13]. Concentrated forms of platelets, such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), have been utilized in these contexts [

14]. PRF was first introduced by Choukroun et al. in 2001 for use in oral and maxillofacial surgery [

15]. It offers several advantages over PRP, including a simpler preparation process and the absence of chemical treatments, resulting in a strictly autologous product [

16].

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) has been shown to provide beneficial effects on dental regeneration. It enhances wound healing and periodontal regeneration, leading to accelerated recovery and bone regeneration following periodontal treatment [

13]. As an autologous platelet concentrate, PRF is used in various medical fields, including dentistry and periodontology [

17]. PRF consists of platelets, cytokines, leukocytes, a dense fibrin matrix, glycoproteins, and growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor β1, and vascular endothelial growth factor. It is derived from the patient’s blood without the use of anticoagulants. PRF has demonstrated the capacity to accelerate wound healing, promote the attraction, proliferation, and differentiation of cells, and enhance the overall process of tissue regeneration [

18]. PRF has demonstrated the ability to accelerate wound healing, facilitate the attraction, multiplication, and specialization of cells, and improve the process of tissue regeneration. It functions as a signalling agent and provides a long-lasting scaffolding effect that promotes cell activity [

19]. PRF has demonstrated efficacy in treating musculoskeletal diseases, promoting periodontal regeneration, and mending non-healing trophic ulcers in leprosy patients. Despite not meeting all the requirements of a conventional barrier membrane, PRF has been shown to enhance wound healing greatly and may possess other characteristics beyond a barrier membrane's limitations [

20,

21].

Preparation techniques of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF)

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) can be prepared through numerous techniques. One technique includes centrifuging blood samples to separate them into platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) with varying quantities of plasma components and physical-chemical properties [

13]. Another method involves collecting blood without anticoagulants, enabling the creation of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) without any artificial biochemical alterations. This results in fibrin membranes that are rich in platelets and growth factors [

19]. The typical procedure for PRF preparation includes acquiring a consistent quality and quantity of the fibrin matrix, leukocytes, platelets, and growth factors [

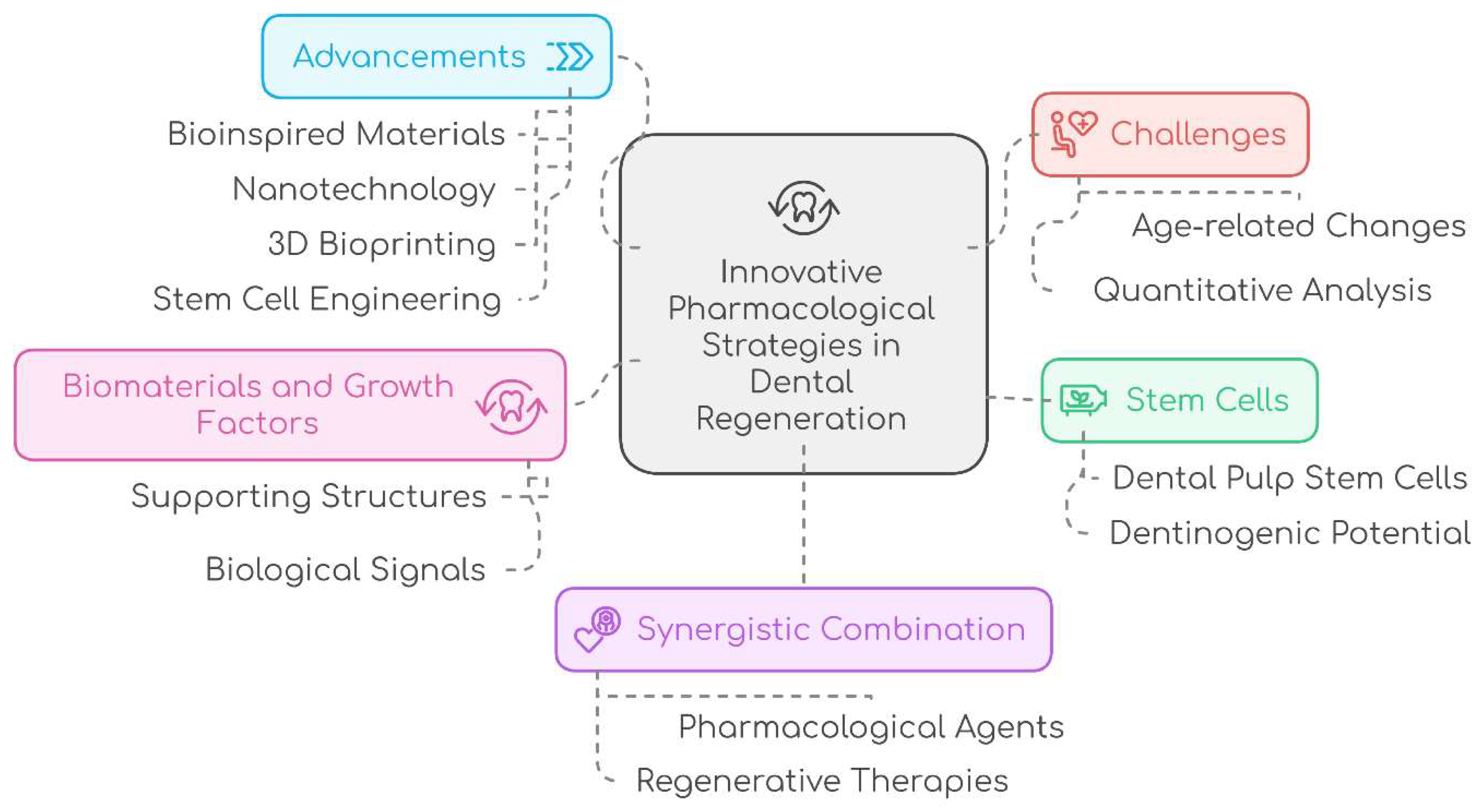

22]. The advancement of PRF protocols has resulted in the creation of different types of PRF (

Figure 1), including L-PRF (a membrane that collects platelets and leukocytes), A-PRF (PRF abundant in growth factors and cytokines), I-PRF (a liquid phase with increased cell accumulation), T-PRF (titanium-prepared PRF with improved biocompatibility), C-PRF (platelet aggregates with the highest cell accumulation), and A-PRF+ (an advanced form of A-PRF with enhanced growth factor release) [

23].

Biological properties of PRF and its applications in dental regeneration.

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) exhibits numerous biological characteristics that render it a significant asset in the fields of regenerative medicine and dentistry. The biological properties of PRF involve increasing angiogenesis, stimulating cell proliferation, modulating the inflammatory response, facilitating soft tissue healing, and improving bone regeneration [

24]. Below are a few fundamental biological characteristics of PRF:

Platelet-Derived Growth Factors: PRF contains a high concentration of platelets that act as rich sources of various growth factors. These growth factors are crucial for tissue repair and regeneration as they promote cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation [

25]. Among the key growth factors in PRF are platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) [

26]. These factors play a vital role in angiogenesis, which refers to the formation of new blood vessels, as well as in tissue remodeling and wound healing [

27].

Fibrin Matrix: Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) generates a natural fibrin matrix that acts as a scaffold for cellular movement and tissue restoration [

16]. This fibrin matrix provides structural support and aids in the organization of cells and the extracellular matrix during the wound healing process. Additionally, it serves as a reservoir for growth factors and other bioactive substances, gradually releasing them over time, which promotes ongoing tissue repair and regeneration [

28,

29].

Leukocytes and Immune Response: PRF consists of leukocytes, specifically neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes, These immune cells have a vital function in the immune response and protection against infections. In addition, leukocytes secrete cytokines and other substances that control the inflammatory response, modify immunological reactions, and impact tissue repair mechanisms [

30,

31].

Anti-Inflammatory Properties: Although inflammation is essential for healing, an excessive or protracted inflammatory response might impede tissue regeneration. PRF has demonstrated anti-inflammatory characteristics through its ability to regulate the immune response and decrease the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The capacity to control inflammation facilitates the establishment of an ideal milieu for the process of healing and the renewal of tissues [

32].

Angiogenic Potential: The growth factors found in PRF, including VEGF, stimulate the development of fresh blood vessels through a process called angiogenesis. The angiogenic capacity of this treatment improves the blood flow to the affected region, hence promoting the transportation of oxygen, nutrients, and immune cells that are essential for the repair and regeneration of tissues [

33].

PRF has demonstrated the ability to promote bone and cartilage regeneration, indicating its osteogenic and chondrogenic potential. The growth factors and bioactive compounds in PRF make osteoblasts and chondrocytes multiply and change into other types of cells. PRF's inherent characteristics render it highly helpful in the fields of dental implantology, periodontal regeneration, and orthopaedic operations [

34].

Clinical applications of PRF in dentistry

PRF has demonstrated its versatility as a biomaterial in dentistry through its numerous applications, encompassing tissue regeneration, wound healing, and antimicrobial activity.

- 7.

Role of PRF in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: PRF has been applied in dentistry and oral surgery to enhance tissue regeneration and promote wound healing. It has produced favorable results in a range of procedures, including alveolar ridge preservation, orthognathic surgeries (such as Lefort osteotomies), cleft lip and palate repairs, maxillary sinus augmentation, and dental implant placements [

35]. Additionally, PRF exhibits anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties, which are beneficial in the context of oral and maxillofacial surgery [

36]. Promising initial outcomes have also been reported with PRF-based membranes for patients undergoing anticoagulant therapy and for the prevention and treatment of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the mandible. Furthermore, L-PRF can be used to fill cavities after tumor excision [

37]. It has also been noted that PRF reduces the healing time of soft tissues, lowers morbidity, and decreases the need for analgesics following tooth extractions [

38].

- 8.

Role of PRF in periodontology: Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) is extensively utilized in periodontal surgery and dentistry due to its minimally invasive nature and low likelihood of adverse effects [

24]. In the realm of periodontics, PRF aids in the regeneration of periodontal tissues that have been lost due to periodontal diseases. It can be applied in periodontal pockets, defects, and around exposed roots to enhance the regeneration of the periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone [

39].

- 9.

Titanium-prepared platelet-rich fibrin (T-PRF) has effectively managed gingival recession, leading to impressive root coverage and favourable healing outcomes [

40]. Another study demonstrates that PRF was promising for treating grade II furcation deficiencies but does not offer any benefits for treating infra-bony periodontal pockets or root exposures [

41].

- 10.

Role of PRF in Regenerative Endodontics: PRF has also been employed in regenerative endodontics to facilitate tissue ingrowth and revascularization, leading to increased thickness of dentinal walls, root elongation, repair of pulpal floor perforations, revascularization of teeth with necrotic pulps, and regression of periapical pathologies [

42]. In a cohort study, Kritika et al. utilized mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) alongside platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) to investigate regenerative endodontics in non-vital immature maxillary incisors. They reported that PRF facilitated growth factors and induced root maturation, achieving significant increases in root length, dentinal wall thickness, and reductions in apical diameter over a 24-month follow-up period [

43]. PRF is particularly effective for revascularizing young permanent teeth with necrotic pulps, as its scaffold is rich in growth factors that promote cellular proliferation and differentiation. It serves as a structural support for tissue growth [

44]. The growth factors are released gradually as the fibrin matrix is absorbed, providing ongoing healing. Shivashankar et al. observed that applying PRF to a tooth with pulpal necrosis and an exposed apex resulted in thicker dentinal walls, root extension, reduction of the periapical lesion, and closure of the apex [

45]. Furthermore, a study indicated that regenerative endodontic treatment using advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF+) was successfully performed on a 12-year-old patient with necrotic pulp and asymptomatic apical periodontitis. After a 24-month follow-up post-treatment, the patient reported no symptoms, with complete root development and significant healing around the tooth apex [

46].

- 11.

Role of PRF in the Management of Oral Ulcers: Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) plays a crucial role in the treatment of oral ulcers and wounds. It can be applied topically to promote healing of soft tissue wounds and address bacterial sepsis, thereby improving the quality of life for patients suffering from oral mucositis [

47]. Additionally, PRF has been demonstrated to accelerate wound healing and reduce ulcer size in leprosy patients experiencing non-healing trophic ulcers [

48].

Stem Cell-Based Therapies in Dental Regeneration

overview of different types of stem cells used in dental pharmacology.

Stem Cells (SCs): Stem cells are undifferentiated cells that possess an extraordinary ability to proliferate, produce, and differentiate into various somatic cells, both in vitro and in vivo. Within the adult body, different populations of SCs play essential roles in maturation and tissue repair. Their remarkable capacity to generate functionally important physiological cells has led to the investigation of alternative strategies, such as recombinant or primed cells, as potential substitutes [

49].

Stem cells can be classified into four primary categories based on their origin: embryonic stem cells, fetal stem cells, umbilical cord stem cells, and adult stem cells. Additionally, they can also be categorized by their developmental stage, including pluripotent stem cells, multipotent stem cells, totipotent stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells [

50].

Oral tissues provide a rich source of stem cells, garnering interest from dental professionals due to their easier accessibility compared to other stem cell populations. These cells possess unique properties that are highly relevant in tissue engineering. In dentistry, patients often experience issues such as alveolar bone resorption following tooth extractions or loss due to periodontal disease, dental caries, or trauma-induced fractures. Individuals who lose teeth may face further bone loss, particularly in the mandible, which can hinder their ability to receive dental implants as a treatment option.

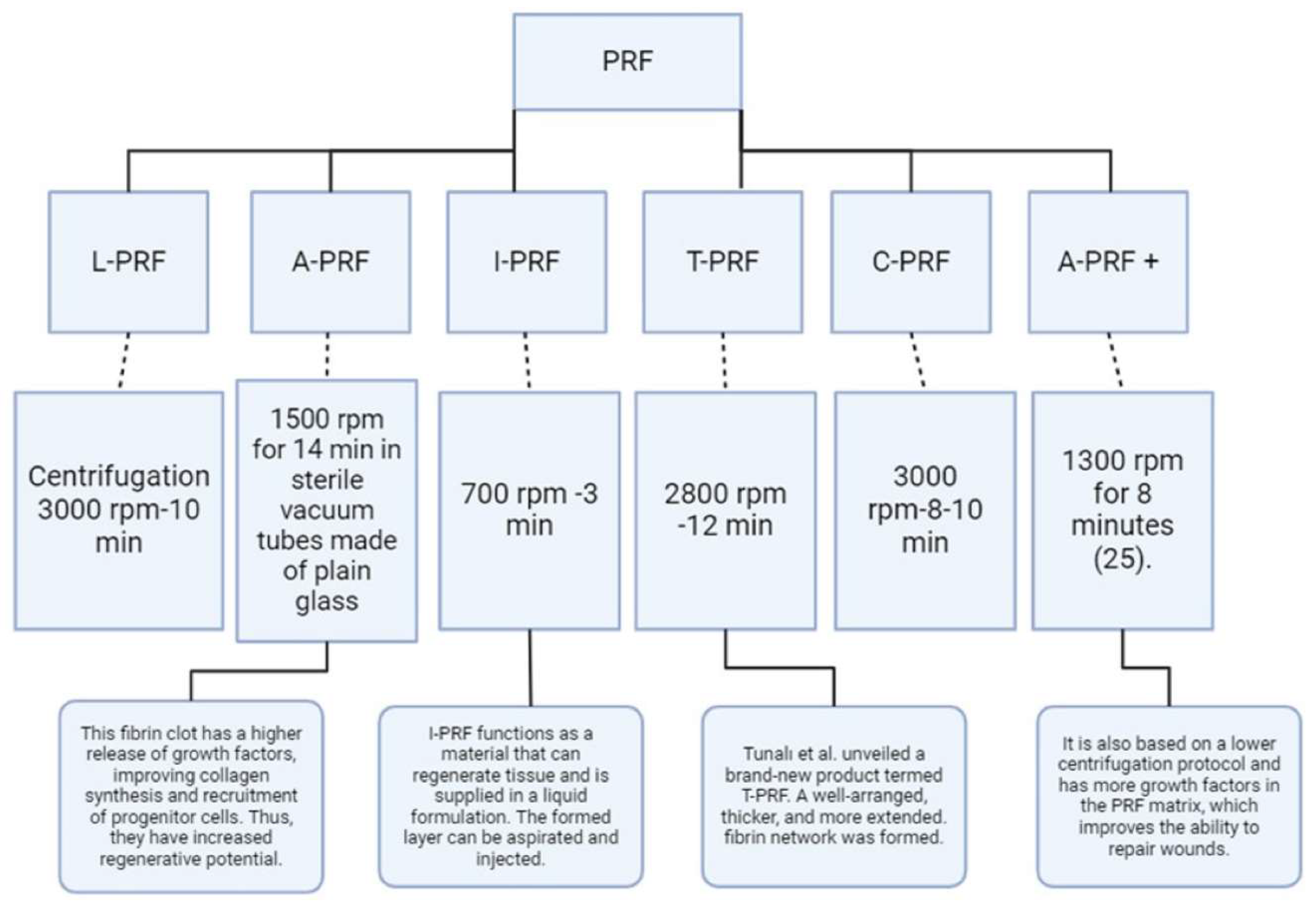

This situation creates a significant demand for stem cell-based tissue engineering therapies to address critical defects in periodontal tissue and alveolar bone, with the goal of restoring lost teeth. Dental tissues harbor two main types of mature stem cells: Oral Epithelial Stem Cells (OESCs) and Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), both of which are crucial for tooth tissue regeneration. The dental pulp and periodontal tissues provide favorable environments that encourage the formation of reparative dentin after dental interventions, facilitating the regeneration process. These tissues serve as valuable sources from which MSCs or other stem cells can be harvested.

Dental-derived stem cells encompass Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs), Dental Follicle Progenitor Cells (DFPCs), Stem Cells from Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHED), Stem Cells from Apical Papilla (SCAP), Tooth Germ Stem Cells (TGSCs), Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells (PDLSCs), Tooth Germ Progenitor Cells (TGPCs), and gingival mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells (GMSCs) (

Figure 2) [

49].

The potential of stem cell-based therapies for tissue regeneration in dentistry.

Growth Factors (GFs): Growth factors play a crucial role in stimulating cell proliferation and are essential for tissue engineering when combined with scaffolds and stem cells. Research has explored the use of recombinant GFs for regenerating various oral tissues, including bone, salivary glands, nerves, dentin-pulp complexes, and periodontal tissues.

In regenerative endodontics, the application of growth factors like stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), and fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1) has shown promise for the dentin-pulp complex. These growth factors, when paired with scaffolds, have facilitated pulp regeneration, dentin formation, mineralization, neovascularization, and innervation within the root canal system (

Figure 3).

The regeneration of periodontal and alveolar bone has been improved through the use of growth factors such as bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP-7), and enamel matrix derivative (EMD). When applied alongside suitable scaffolds, these growth factors have encouraged the differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells and dental follicle progenitor cells into cementoblasts and osteoblasts, thereby supporting the regeneration of periodontal tissue and alveolar bone (

Figure 3).

For nerve regeneration in oral tissues, growth factors such as nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been beneficial. When incorporated into appropriate scaffolds, these growth factors have shown the potential to promote the differentiation and regeneration of nerve cells, aiding in the restoration of neural function within oral tissues (

Figure 3) [

49].

Type of dental stem cell and their Clinical Application in dentistry

1

. Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs) are characterized by the positive expression of markers such as CD9, CD10, CD13, CD29, CD44, CD49d, CD59, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD106, CD146, and CD166. These cells can differentiate into various cell types, including osteoblasts, odontoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, neural cells, muscle cells, melanoma cells, and hepatocytes [

49].

Application:

DPSCs have great potential for regenerating pulp-dentin tissue, making them useful in treating conditions like pulpitis and dentin defects. Their ability to generate dentin/pulp-like structures in vivo makes them a promising option for dental tissue engineering, offering an innovative alternative to traditional dental treatments. DPSCs could revolutionize regenerative dentistry by addressing challenges in oral and maxillofacial tissue repair [

50].

2.

Dental Follicle Progenitor Cells (DFPCs) express markers like CD10, CD13, CD29, CD44, CD59, CD73, and CD105. They have the capacity to differentiate into various cell types such as osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, neural cells, cementoblasts, periodontal ligament fibroblasts, and hepatocyte-like cells. DFPCs show promise in enhancing bone strength and regenerating periodontal tissues [

49].

Clinical Application:

DFPCs have demonstrated potential in bioengineering periodontal tissue on dental implants, suggesting their role in periodontal regeneration. Their ability to differentiate into cementoblasts and osteoblasts further supports their application in tissue engineering. DFPCs are a valuable resource for regenerating tooth roots and addressing clinical challenges in oral and maxillofacial regeneration [

50].

3

. Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHEDs): are marked by the positive expression of CD13, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD146, CD150, and CD166. These cells can differentiate into osteoblasts, odontoblasts, neural cells, adipocytes, hepatocytes, and endothelial cells, and they show potential in bone and dental tissue regeneration [

49].

Clinical Application:

SHEDs have exhibited versatility in regenerating various tissues, showing promise in treating conditions like myocardial infarction, muscular dystrophy, cerebral ischemia, and corneal injury. Their capacity to promote neurogenesis and vasculogenesis indicates potential in stroke treatment. Additionally, SHEDs have been effective in repairing large calvarial and mandibular defects, making them a valuable cell source for orofacial tissue reconstruction and regenerative medicine [

50].

4

. Stem Cells from Apical Papilla (SCAP) express markers such as CD24, CD44, CD49d, CD51/61, CD56, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD106, CD146, and CD166. These cells have shown potential in dentin regeneration and pulp tissue repair [

49].

Clinical Application:

SCAP have proven useful in root development and regeneration, making them an important cell source for addressing oral and maxillofacial clinical challenges. Their ability to differentiate into odontoblast-like cells and form dentin-like tissue both in vitro and in vivo supports their application in dental tissue engineering. Additionally, SCAP have shown promise in neural tissue regeneration, with potential applications in treating neurodegenerative diseases [

50].

5.

Tooth Germ Progenitor Cells (TGPCs) are undifferentiated cells found in human third molars, possessing high proliferative capacity and the potential to differentiate into various cell types such as chondrocytes, adipocytes, osteoblasts, odontoblasts, and neurons [

49].

Clinical Application:

TGPCs have been applied in regenerative medicine, particularly for liver diseases and bone regeneration, making them a valuable resource for tissue engineering and regenerative therapies [

49].

6.

Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells (PDLSCs) express markers such as STRO-1, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD146. They possess the ability to differentiate into bone, cartilage, adipose, neuronal cells, and cementoblasts, which is crucial for periodontal regeneration and tissue engineering [

49].

Clinical Application:

PDLSCs have shown promise in periodontal regeneration, with studies highlighting their effectiveness in repairing periodontal defects in both animal models and human clinical trials. PDLSCs are also being explored for use in dental implant treatments, offering a potential alternative to traditional osseointegrated implants [

50].

7.

Gingival Mesenchymal Stem Cells (GMSCs) express markers including CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD146. They demonstrate strong potential in periodontal regeneration and wound healing [

49].

Clinical Application:

GMSCs have shown promise in medical applications such as wound healing, tissue regeneration, and bone formation. Their immunomodulatory properties make them effective in treating inflammatory conditions like colitis, contact hypersensitivity, and arthritis in animal models. Additionally, GMSCs have been explored for generating connective tissue-like structures [

50].

8.

Oral Mucosa-Derived Stem Cells (OMSCs) are adult stem cells found in the oral mucosa, including gingiva lamina propria and oral epithelial stem cells/progenitors. These cells exhibit self-renewal, clonogenicity, and multipotent differentiation abilities, similar to bone marrow-derived MSCs [

49].

Clinical Application:

OMSCs have been utilized in regenerative medicine for the repair of various oral and maxillofacial tissues, including periodontal, bone, and nerve regeneration [

49].

Challenges and Future Directions

Regenerative approaches in dental pharmacology offer promising avenues for restoring damaged dental tissues and addressing various oral health concerns. However, their implementation is accompanied by a set of challenges and limitations that require thorough consideration and ongoing research.

One significant limitation in regenerative dental pharmacology is the restoration of morphological and functional reconstruction. Despite the potential shown by techniques utilizing dental pulp stem cells, they often encounter obstacles in achieving complete tissue regeneration [

51]. This limitation can impede the effectiveness of regenerative therapies, leaving gaps in the restoration process and compromising overall treatment outcomes. Moreover, age-related changes in dental tissues may hinder the success of pulp regeneration therapy in older patients.

Furthermore, the need for more strict quantitative analysis poses a significant challenge in translating regenerative approaches from experimental studies to clinical applications. Despite promising results in preclinical research, the efficacy and reliability of these approaches in real-world clinical scenarios remain uncertain due to insufficient quantitative testing, particularly in vivo. This gap in quantitative analysis not only hampers the validation of regenerative techniques but also limits their widespread adoption and integration into routine dental practice.

Achieving complete regeneration of dental pulp tissue remains a formidable challenge due to the intricate nature of dental tissues and the complexity of the regenerative process. Factors such as the microenvironment of the dental pulp, interactions between different cell types, and the influence of systemic health conditions all contribute to the complexity, making it difficult to achieve comprehensive restoration of dental tissues.

Several potential strategies can be employed to enhance the efficacy of tissue regeneration in dentistry, each addressing specific challenges and limitations associated with current approaches.

Implementing enhanced quantitative analysis methodologies is crucial. Rigorous testing of oral stem cells' self-proliferation and differentiation abilities, particularly in vivo, can provide valuable insights into their regenerative potential, essential for validating the efficacy of regenerative therapies and advancing their clinical application.

Moreover, integrating engineering and biology principles offers a promising avenue for tissue regeneration. By combining innovative engineering techniques with biological insights, researchers can develop advanced strategies to replicate and enhance tissue regeneration processes [

52]. This interdisciplinary approach has already demonstrated promising results in dentistry and holds significant potential for further advancements in tissue restoration.

Continued exploration of biological pathways and their applications in regenerative dental science is essential. Understanding the underlying mechanisms governing tissue regeneration can lead to the identification of novel targets and approaches to improve treatment outcomes.

Innovative techniques, such as the utilization of chitosan-collagen biomembranes embedded with specific compounds, show promise in enhancing the dentinogenic potential of dental pulp stem cells [

53]. These advancements contribute to overcoming limitations in tissue restoration and offer new avenues for enhancing regenerative therapies.

Furthermore, the transplantation of dental mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represents a promising approach for regenerating dental pulp within the pulp chamber. By leveraging the regenerative potential of MSCs, researchers aim to address age-related changes and other limitations that hinder the success of pulp regeneration therapy [54].

By adopting these strategies, researchers and practitioners can collaboratively overcome current challenges and advance the field of tissue regeneration in dentistry, ultimately improving patient outcomes and revolutionizing dental care.

The field of tissue regeneration in dentistry is witnessing transformative advancements driven by emerging trends and future directions. Bioinspired materials offer tailored solutions for tissue regeneration by providing an optimal microenvironment for cellular activities, drawing inspiration from natural extracellular matrices. Nanotechnology facilitates precise therapeutic delivery and enhances cellular interactions, overcoming existing limitations in regenerative dentistry.

3D bioprinting technology enables the fabrication of complex tissue constructs with precise spatial control, promising personalized solutions for dental implants and tissue engineering. Stem cell engineering, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and genome editing, opens new avenues for scalable and customizable cell-based therapies in dental tissue regeneration.

Furthermore, the integration of pharmacological agents with regenerative therapies through regenerative pharmacology enhances tissue microenvironments and accelerates translation into clinical practice. These emerging trends herald a future where innovative strategies driven by bioinspired materials, nanotechnology, 3D bioprinting, stem cell engineering, and regenerative pharmacology converge to revolutionize dental care, offering tailored solutions for tissue regeneration and improving oral health outcomes.

Authors' contributions

All authors have made the conception and design of the review paper, contributed significantly to the drafting and refinement of the manuscript, and provided substantial intellectual input throughout the analysis and critical review process. Additionally, All authors have actively participated in the acquisition of relevant literature and materials, ensuring the accuracy and completeness of the content. Furthermore, all authors have been involved in the critical review and revision of the manuscript, providing valuable insights and feedback. Finally, all authors have given their final approval of the version to be published and take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to our supervisor, Ali Alsuraifi, for his invaluable contributions to this research review paper. His significant input in refining the content and providing final approval of the manuscript played a crucial role in its completion. we also would like to extend our heartfelt appreciation to Abdullah Ayad for his outstanding contributions to this research review paper. His leadership in guiding the entire review process and his exceptional contributions were instrumental in shaping the quality and completeness of this work.

Statements and Declarations

Financial declaration

No external funding was received for this review research paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to the writing and approved the manuscript before submission.

Declaration Regarding the Use of Al-Assisted Readability Enhancement

I hereby affirm that the utilization of Al-assisted tools in the refinement of the manuscript was strictly limited to enhancing its readability. At no point were Al technologies employed to supplant essential authorial responsibilities, including the generation of scientific, pedagogic, or medical insights, the formulation of scientific conclusions, or the issuance of clinical recommendations.

The implementation of Al for readability enhancement was rigorously supervised under the discerning eye of human oversight and control.

| Abbreviation |

Full Name |

| PRP |

Platelet-Rich Plasma |

| PRF |

Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

| BMPs |

Bone Morphogenetic Proteins |

| FGF-2 |

Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 |

| PDGF |

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| VEGF |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| TGF-β |

Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| DPSCs |

Dental Pulp Stem Cells |

| SCAP |

Stem Cells from Apical Papilla |

| SHED |

Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth |

| PDLSCs |

Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells |

| GMSCs |

Gingival Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| OMSCs |

Oral Mucosa-Derived Stem Cells |

| NGF |

Nerve Growth Factor |

| BDNF |

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| G-CSF |

Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| EMD |

Enamel Matrix Derivative |

| BRONJ |

Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw |

| MTA |

Mineral Trioxide Aggregate |

References

- M. Adamička, A. Adamičková, L. Danišovič, A. Gažová, J. Kyselovič, "Pharmacological Approaches and Regeneration of Bone Defects with Dental Pulp Stem Cells", Stem Cells International, vol. 2021, Article ID 4593322, 7 pages, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cicciù M. (2020). Growth Factor Applied to Oral and Regenerative Surgery. International journal of molecular sciences, 21(20), 7752. [CrossRef]

- Kurogoushi, R., Hasegawa, T., Akazawa, Y., Iwata, K., Sugimoto, A., Yamaguchi-Ueda, K., Miyazaki, A., Narwidina, A., Kawarabayashi, K., Kitamura, T., Nakagawa, H., Iwasaki, T., & Iwamoto, T. (2021). Fibroblast growth factor 2 suppresses the expression of C-C motif chemokine 11 through the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway in human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 22(6). [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Goldman, G., MacDougall, M., & Chen, S. (2022). BMP signaling pathway in dentin development and diseases. Cells, 11(14), 2216. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D., Caton, J. G., & Benoit, D. S. W. (2022). Periodontal Wound Healing and Regeneration: Insights for Engineering New Therapeutic Approaches. Frontiers in Dental Medicine, 3. [CrossRef]

- Novais, A., Chatzopoulou, E., Chaussain, C., & Gorin, C. (2021). The Potential of FGF-2 in Craniofacial Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. Cells, 10(4), 932. [CrossRef]

- Margono, A., Bagio, D. A., Julianto, I., & Suprastiwi, E. (2021). The effect of calcium gluconate on platelet rich plasma activation for VEGF-A expression of human dental pulp stem cells. European Journal of Dentistry, 16(02), 424–429. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Gou, L., Zhang, P., Li, H., & Qiu, S. (2020). Platelet-rich plasma and regenerative dentistry. Australian Dental Journal, 65(2), 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Attia, S., Narberhaus, C., Schaaf, H., Streckbein, P., Pons-Kühnemann, J., Schmitt, C., Neukam, F. W., Howaldt, H. P., & Böttger, S. (2020). Long-Term Influence of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) on Dental Implants after Maxillary Augmentation: Implant Survival and Success Rates. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(2), 391. [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, V., Ciric, M., Jovanovic, V., Trandafilovic, M., & Stojanovic, P. (2021). Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications. Open medicine (Warsaw, Poland), 16(1), 446–454. [CrossRef]

- From Hematology to Tissue Engineering: Current Status and Projection of Platelet Concentrates and their Derivatives. Available online: https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/files-articulos/UO/41(2022)/231273734002/index.html.

- Goswami, P., Chaudhary, V., Arya, A., Verma, R., Vijayakumar, G., & Bhavani, M. (2024). Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF) and its Application in Dentistry: A Literature Review. Journal of Pharmacy and Bioallied Sciences, 16(Suppl 1), S5–S7. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Gou, L., Zhang, P., Li, H., & Qiu, S. (2020). Platelet-rich plasma and regenerative dentistry. Australian dental journal, 65(2), 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Farshidfar, N., Jafarpour, D., Firoozi, P., Sahmeddini, S., Hamedani, S., de Souza, R. F., & Tayebi, L. (2022). The application of injectable platelet-rich fibrin in regenerative dentistry: A systematic scoping review of In vitro and In vivo studies. The Japanese dental science review, 58, 89–123. [CrossRef]

- Zwittnig, K., Mukaddam, K., Vegh, D., Herber, V., Jakse, N., Schlenke, P., Zrnc, T. A., & Payer, M. (2022). Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Oral Surgery and Implantology: A Narrative Review. Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy : offizielles Organ der Deutschen Gesellschaft fur Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhamatologie, 50(4), 348–359. [CrossRef]

- Atsu, N., Ekinci-Aslanoglu, C., Kantarci-Demirkiran, B., Caf, N., & Nuhoglu, F. (2023). The comparison of Platelet-Rich plasma versus injectable platelet rich fibrin in facial skin rejuvenation. Dermatologic Therapy, 2023(1). [CrossRef]

- Lana, J. F. S. D., Purita, J., Everts, P. A., De Carvalho Neto, P. B., De Moraes Ferreira Jorge, D., Mosaner, T., Huber, S. C., Azzini, G. O. M., Da Fonseca, L. F., Jeyaraman, M., Dallo, I., & Santos, G. S. (2023). Platelet-Rich Plasma Power-Mix Gel (ppm)—An Orthobiologic Optimization Protocol Rich in Growth Factors and Fibrin. Gels, 9(7), 553. [CrossRef]

- Bodduru, R., Nudrath, A., Hari, S., Mushti, V. A., Veldurthi, D., & Charan, S. S. (2023). PRF: EMPOWERING PERIODONTAL REGENERATION FROM WITHIN. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology.

- Sağsöz, A., & Kaya, F. A. (2023). Use of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in the periodontology: A Review. Journal of Medical and Dental Investigations, 4, e230317. [CrossRef]

- Egierska, D., Perszke, M., Mazur, M., & Duś-Ilnicka, I. (2023). Platelet-rich plasma and platelet-rich fibrin in oral surgery: A narrative review. Dental and Medical Problems, 60(1), 177–186. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. (2023). Platelet rich fibrin is not a barrier membrane! Or is it? World Journal of Clinical Cases, 11(11), 2396–2404. [CrossRef]

- Ak, S., Devar, N., Velmurugan, P., Veeramuthu, M., Deepak, V., & Magadaline, V. (2023). Platelet Rich Fibrin (PRF) - A Novel Regenerative Material in oral and maxillofacial surgery - A LITERATURE REVIEW. Medical Research Archives, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- John, D. S., & Shenoy, N. (2023). Platelet-rich fibrin: Current trends in periodontal regeneration. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, K., Farrukh, U., Sarwar, H., Gul, J., Singh, S. P., Khan, S. S., & Naeem, M. M. (2023). Effect of PRF on extraction socket healing. International Journal of Health Sciences (IJHS), 7(S1), 974–989. [CrossRef]

- Mirhaj, M., Salehi, S., Tavakoli, M. R., Varshosaz, J., Labbaf, S., Abadi, S. a. M., & Haghighi, V. (2022). Comparison of physical, mechanical and biological effects of leucocyte-PRF and advanced-PRF on polyacrylamide nanofiber wound dressings: In vitro and in vivo evaluations. Biomaterials Advances, 141, 213082. [CrossRef]

- Baca-Gonzalez, L., Zamora, R. S., Rancan, L., Fernández-Tresguerres, F. G., Fernández-Tresguerres, I., López-Pintor, R. M., López-Quiles, J., Leco, I., & Torres, J. (2022). Plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF) and leukocyte-platelet rich fibrin (L-PRF): comparative release of growth factors and biological effect on osteoblasts. International Journal of Implant Dentistry, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Al-Rihaymee, S., & Mahmood, M. S. (2023). Platelet-rich fibrin potential role in periodontal regeneration: a review study. ResearchGate. [CrossRef]

- Ducret, M., Costantini, A., Gobert, S., Farges, J. C., & Bekhouche, M. (2021). Fibrin-based scaffolds for dental pulp regeneration: from biology to nanotherapeutics. European cells & materials, 41, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Zwittnig, K., Kirnbauer, B., Jakse, N., Schlenke, P., Mischak, I., Ghanaati, S., Al-Maawi, S., Végh, D., Payer, M., & Zrnc, T. A. (2022). Growth Factor Release within Liquid and Solid PRF. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(17), 5070. [CrossRef]

- Feng, M., Wang, Y., Zhang, P., Zhao, Q., Yu, S., Shen, K., Miron, R. J., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Antibacterial effects of platelet-rich fibrin produced by horizontal centrifugation. International journal of oral science, 12(1), 32. [CrossRef]

- Makki, A. Z., Alsulami, A. M., Almatrafi, A. S., Sindi, M. Z., & Sembawa, S. N. (2021). The Effectiveness of Advanced Platelet-Rich Fibrin in comparison with Leukocyte-Platelet-Rich Fibrin on Outcome after Dentoalveolar Surgery. International Journal of Dentistry, 2021, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Moraschini, V., Miron, R. J., De Almeida Barros Mourão, C. F., Louro, R. S., Sculean, A., Da Fonseca, L. a. M., Calasans-Maia, M. D., & Shibli, J. A. (2023). Antimicrobial effect of platelet-rich fibrin: A systematic review of in vitro evidence-based studies. Periodontology 2000. [CrossRef]

- Seghezzi, G., Patel, S., Ren, C. J., Gualandris, A., Pintucci, G., Robbins, E. S., Shapiro, R. L., Galloway, A. C., Rifkin, D. B., & Mignatti, P. (1998). Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the endothelial cells of forming capillaries: an autocrine mechanism contributing to angiogenesis. The Journal of cell biology, 141(7), 1659–1673. [CrossRef]

- Damsaz, M., Castagnoli, C. Z., Eshghpour, M., Alamdari, D. H., Alamdari, A. H., Noujeim, Z., & Haidar, Z. S. (2020). Evidence-Based clinical efficacy of leukocyte and Platelet-Rich fibrin in maxillary sinus floor lift, graft and surgical augmentation procedures. Frontiers in Surgery, 7. [CrossRef]

- De Lima Barbosa, R., Lourenço, E. S., De Azevedo Dos Santos, J. V., Rocha, N. R. S., Mourão, C. F., & Alves, G. G. (2023). The effects of Platelet-Rich fibrin in the behavior of mineralizing cells related to bone tissue Regeneration—A scoping review of in vitro evidence. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 14(10), 503. [CrossRef]

- Micko, L., Šalma, I., Skadiņš, I., Egle, K., Šalms, Ģ., & Dubņika, A. (2023). Can our blood help ensure antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory properties in oral and maxillofacial surgery? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(2), 1073. [CrossRef]

- Ockerman, A., Braem, A., EzEldeen, M., Castro, A., Coucke, B., Politis, C., Verhamme, P., Jacobs, R., & Quirynen, M. (2020). Mechanical and structural properties of leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin membranes: An in vitro study on the impact of anticoagulant therapy. Journal of periodontal research, 55(5), 686–693. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A. M., De Mesquita, K. B. N., De Azevedo, M. W. C., Ribeiro, E. G. M., Brígido, K. G. R., & Brígido, J. A. (2023). Use of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in dental surgical procedures. Research, Society and Development, 12(2), e2512239811. [CrossRef]

- Alani, R., Ercani, E., Fıratlı, Y., Fıratlı, E., & Tunalı, M. (2023). Innovative i-PRF semisurgical method for gingival augmentation and root coverage in thin periodontal phenotypes: a preliminary study. PubMed, 54(9), 734–743. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, H. S., Gummaluri, S. S., Rani, A., Verma, S. K., Bhattacharya, P., & Gurushanth, S. M. R. (2023). Additional benefits of titanium platelet-rich fibrin (T-PRF) with a coronally advanced flap (CAF) for recession coverage: A case series. Dental and Medical Problems, 60(2), 279–285. [CrossRef]

- Tarallo, F., Mancini, L., Pitzurra, L., Bizzarro, S., Tepedino, M., & Marchetti, E. (2020). Use of Platelet-Rich Fibrin in the Treatment of Grade 2 Furcation Defects: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(7), 2104. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, S., Tehreem, F., Khan, M. R., Ahmed, F., Marya, A., & Karobari, M. I. (2021). Platelet-Rich fibrin Used in Regenerative Endodontics and Dentistry: Current uses, limitations, and Future Recommendations for application. International Journal of Dentistry, 2021, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kritika, S., Sujatha, V., Srinivasan, N., Renganathan, S. K., & Mahalaxmi, S. (2021). Prospective cohort study of regenerative potential of non vital immature permanent maxillary central incisors using platelet rich fibrin scaffold. Scientific Reports, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hady, A. Y., & Badr, A. E. S. (2022). The Efficacy of Advanced Platelet-rich Fibrin in Revascularization of Immature Necrotic Teeth. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice, 23(7), 725-732.

- Tony, G., & Elheny, A. (2024). Clinical evaluation of Platelet-Rich fibrin in revitalization of necrotic young permanent incisors. El-Minia Medical Bulletin, 0(0), 0. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S. J. F., Chitsaz, N., Hamrah, M. H., Maleki, D., & Taghizadeh, E. (2023). Regenerative endodontic management of an immature necrotic premolar using advanced Platelet-Rich fibrin. Case Reports in Dentistry, 2023, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M., Gianfreda, F., De Oliveira Rosa, A. C. P., Fiorillo, L., Cervino, G., Cicciù, M., & Bollero, P. (2023). Treatment of oral mucositis using Platelet-Rich-Fibrin: A retrospective study on oncological patients. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 34(5), 1527–1529. [CrossRef]

- Vendhan, S., Neema, S., Vasudevan, B., Krishnan, L., & Gera, V. (2023). Platelet-rich fibrin therapy in the management of nonhealing trophic ulcers due to underlying leprous neuropathy. Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery, Publish Ahead of Print. [CrossRef]

- Mosaddad, S. A., Rasoolzade, B., Namanloo, R. A., Azarpira, N., & Dortaj, H. (2022). Stem cells and common biomaterials in dentistry: a review study. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine, 33(7). [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., Zeng, L., Zhang, Z., Zhu, G., Xu, Z., Xia, J., Weng, J., Li, J., & Pathak, J. L. (2023). Cannabidiol Rescues TNF-α-Inhibited Proliferation, Migration, and Osteogenic/Odontogenic Differentiation of Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Biomolecules, 13(1), 118. [CrossRef]

- Esdaille, C. J., Washington, K. S., & Laurencin, C. T. (2021). Regenerative engineering: a review of recent advances and future directions. Regenerative Medicine, 16(5), 495–512. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, E., Galler, K. M., & Widbiller, M. (2022). A compilation of study models for dental pulp regeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(22), 14361. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Sosa, J. F., Díaz-Solano, D., Wittig, O., & Cardier, J. E. (2022). Dental pulp regeneration induced by allogenic mesenchymal stromal cell transplantation in a mature tooth: a case report. Journal of Endodontics, 48(6), 736–740. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).