1. Introduction

The predecessors of Co-design include Action Research and Socio technical Design, which emerged alongside the development of participatory design [

1]. It can be traced back to Scandinavia in the 1970s and is also considered the earliest form of participatory design [

2], also known as cooperative design. Since then, the advantages and importance of interdisciplinary collaboration have gradually emerged, and designers are increasingly eager to approach the future users their designs are aimed at [

3]. Therefore, a method called action research has developed and evolved in the field of design practice. This method emphasizes the need for active collaboration between researchers and workers, by providing feedback to researchers based on their practical experience, in order to optimize and improve the actual work situation of staff [

4].At the same time, the participatory design movement has been widely spread around the world. In September 1971, the British Manchester Design Research Association held a conference called "Design Participation". In the preface of the conference, Cross pointed out the responsibility of designers in predicting the adverse effects of projects and emphasized the need for new design methods to address the constantly upgrading problems of the artificial world. He believed that involving people in decision-making may be of certain importance, and since then, users and consumers have gradually been given more initiative and influence [

5]. To this day, user centered design methods are unable to address the scale and complexity of challenges faced by the design industry. Therefore, instead of simply designing products centered around users, we are beginning to explore Co-design services between designers and stakeholders such as users, which is a practice of involving users in the innovation process.

The trend in design applications is to leverage the characteristics of collaborative design to meet user needs. As a design methodology, it involves involving users throughout the design process to jointly complete activities such as requirement analysis and creative generation [

6], in order to ensure that the final product or service better meets users' needs, expectations, and preferences. Czyzewski [

7] first defined it as a system design carried out jointly with users as an expert; Kuhn [

8] believes that it is a role exchange that involves designers in the user world and allows users to directly participate in the design; Gregory [

9] views this design as a process in which users and designers become partners and collaborate to create knowledge; Kanstrup [

10] takes the exploration of user driven innovation by end-users as the perspective and approach for such designs.The summary of various viewpoints makes it clear that collaborative design is a method that emphasizes the use of strong participatory approaches such as collaboration, respect, participation, and co construction, with both users and designers as the main body. It is hoped that users can be deeply involved in the design process to drive innovation. Collaborative design effectively implements the design concept of "people-oriented". Compared with the user centered design concept, users are no longer passive choices, ensuring the scientific nature of the design. Collaborative design is also an important direction for product design reform, providing a good design method to better meet users' emotional needs and reflect personalization. Collaborative design from multiple parties has been widely applied in fields such as education, politics [

11], and healthcare [

12], and has produced services and systems that better meet the needs of the public.

Empirical research on neurobehavior is an effective path for objectively observing team collaboration tasks. The complexity and implicit nature of cooperation level in the collaborative process of multi-party team tasks make it impossible to meet current observation needs solely through subjective evaluation methods. Neuroscience is a discipline that studies the impact of the nervous system on behavior and cognition, using methods such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy brain imaging fNIRS [

13], EEG (electroencephalography) [

14], fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) [

15], and MEG (magnetoencephalography) [

16] to help understand brain functioning. Among them, super scanning technology is widely used as the main method in research on different types of team activities. The concept of superscan was first proposed by Montague in 2002 [

17]. This is a technique that can simultaneously collect changes in brain activity from two or more individuals [

18]. Dumas [

19] found that it can not only observe the activity of individual brain regions, but also pay attention to the synchronicity of brain activity among multiple individuals. IBS is considered a consistent response observed through neuroscience, meaning that when two or more experimental participants complete a specified task, the correlation between activity signals recorded in relevant brain regions can be considered as similarity or synchronicity of brain activity.In the context of teamwork, the rise of IBS can be seen as a coordination and synchronization of neural activity among team members. This synchronicity may help team members better understand and share each other's ideas, thereby promoting team creativity. This technology provides support for observing how people receive ideas from others and think about feedback in team tasks. Among them, fNIRS has better tolerance to head movements and non invasiveness [

20], and has been successfully applied in fields such as sports [

21] and face-to-face communication [

22]. In addition, the research results of fNIRS have laid a theoretical foundation for the psychological theory of team tasks [

23], and provided technical support for their psychological cognitive assessment and psychological state observation. Therefore, this technology is considered to have practical value and prospects in the field of team collaboration research.

The working principle of fNIRS imaging relies on the absorption law of light in different media, that is, the wavelength of light and the type of medium have an impact on the absorption coefficient of light in the medium. Among them, HbO and Hb are sensitive to near-infrared light with wavelengths of around 760nm and 850nm, respectively. Therefore, in the near-infrared ultra scanning experiment, the instrument uses 760mm and 850mm types of light as the emitting light sources. Light passes through the scalp, skull, and is ultimately absorbed by HbO and Hb in the cerebral cortex capillary blood. Calculate the changes in local HbO and Hb concentrations using BLL (Beer-Lambert Law). The basic theory of fNIRS imaging is the neurovascular coupling mechanism [

24], which states that there is a relationship between local neural activation and changes in cerebral blood flow, and the cerebral blood flow supply responds locally to changes in functional activity. After stimulation, the cerebral cortex consumes HbO, leading to an increase in Hb concentration. Subsequently, the compensatory effect of cerebral blood flow causes capillaries to dilate and flow into fresh blood, resulting in an increase in HbO concentration and a decrease in Hb concentration. This process is consistent with the HRF (hemodynamic response function) [

25]. When the brain is induced by specific tasks, relevant brain regions are functionally activated, and due to the existence of neurovascular coupling mechanisms, the changes in brain oxygen levels in these regions have significant characteristics during this process. When fNIRS imaging is performed in the region of interest of the brain, activated dynamic contours can be observed, providing rich spatial information.

WTC (Wavelet Transform Coherence) is a technique for examining the correlation between two time series at particular frequencies and time intervals. In neuroscience, it is frequently employed to assess the synchronization of neural activity across various brain areas or among different individuals [

26]. This approach allows scientists to uncover interaction patterns at the neural level and subsequently investigate the possible associations between tasks and brain regions within these patterns.

3. Results

3.1. IBS Increased in DLPFC and BROCA During Co-Design

By integrating the 24-channel map localized by the Polhemus Patriot system with the WTC analysis results, significant activation in the DLPFC and BROCA area-related channels under Co-design conditions can be observed as shown in below

Table 1.

After conducting WTC analysis in MATLAB, it was found that users and designers exhibited a higher level of synchronization during co-design sessions. Within this dataset ,we observed an increase in consistency was also observed in other channels covering DLPFC and BROCA (CH2, 3, 4, 11, 24).Taking the CH4 pair as an example which was consisting of DLPFC and BROCA ( CH4 : 45 pas triangularis Broca's area, 0.11594, 46 Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, 0.88406), as shown in

Figure 6.

During the aggregated data collected from the overall experiment, encompassing the Exp, Com, and Draw blocks, Significantly higher coherence levels were identified within the temporal frequency range of 12.8 to 51.2 seconds (visually represented in red), suggesting that the enhanced neural synchronization observed within this specific time window is functionally associated with task-related variables.

Firstly, it can be observed that even within the same group performing the same design task, there are differences in coherence between blocks conducted at different times. Specifically, the later blocks exhibit higher coherence compared to the earlier ones, indicating an improved level of collaboration.

Secondly, when comparing the two task modes, it is evident that co-design exhibits a higher and more significant level of coherence than traditional design, as previously mentioned. Furthermore, Fisher Z-transform was performed on the difference in IBS between the Traditional and Co-designs of the same group of subjects, and single sample t-test was performed. It was found that channels 2 and 3 showed a significant increase in IBS compared to the Traditional during Co-design (CH2: t=2.309, p=0.029, Cohen's d=0.429; CH3: t=2.333, p=0.010, Cohen's d=0.433).

Finally, To quantify the changes in coherence among all participants and investigate the levels of collaboration and synchronization across different contextual phases of various design modes for subsequent correlation analysis and discussion, the t-values for interactive blocks under both traditional design and co-design tasks were further calculated. These blocks included "Traditional Com," "Co-design Com," "Traditional Draw," and "Co-design Draw." The t-values obtained from all channels after testing were used to generate the topographic map of t-values as shown in

Figure 7.

It can be clearly seen that the t-value topology map of the Co-design group on the same horizontal round is warmer in color, with larger values and more significant activation effects compared to the Traditional group; The t-value topology diagram of Draw on the same column Block is warmer in color and has larger values compared to the Traditional group, resulting in a more significant activation effect.

3.2. The Gradual Development of Cooperation Has Improved Participants' IBS

Due to the fact that each round experiment has two interactive blocks, Com and Draw, and the order of the two cannot be changed in order to reproduce the real design context, that is, all participants experience Com first and then Draw, which are two different but communicative and cooperative tests, it is necessary to analyze the impact between the two. Based on the analysis above, it can be concluded that Draw exhibits more significant activation than Com under the same experimental conditions. Therefore, further Fisher Z-transform was performed on the IBS difference between Draw and Com in the same group of subjects under Traditional and Co-design, and single sample t-test was performed. After testing, the t-values obtained from all channels generated the t-value topology as shown in

Figure 8. It can be clearly seen that 9 channels in the Traditional group (CH1, 8, 13, 16, 21, 22, 23, 24) and 8 channels in the Co-design group (CH2, 3, 4, 11, 12, 13, 19, 24) have a certain degree of activation due to warm colors. After FDR correction, it was found that they still have significance.

Subsequently, by further visualizing the IBS data in the Com and Draw Blocks with significant channels and drawing line graphs, it can be found that the IBS of the above channels show a significant upward trend gradually from Com to Draw, which may be related to the consensus generated,as shown in

Figure 9.

3.3. IBS Is Related to Psychological Needs Satisfaction Rate

Further analysis will be conducted on the correlation between brain synchronicity IBS in both brains and the users' psychological needs satisfaction rate, exploring the significant relationship between brain synchronicity and psychological needs satisfaction rate discovered in Traditional and Co-designs. Firstly, the total score in the questionnaire data above is divided by the total score to obtain the psychological needs satisfaction rate. Secondly correlation analysis is conducted between the IBS and the psychological needs satisfaction rate of Com and Draw blocks in Traditional and Co-designs for CH2 and CH3.Finally, a scatter diagram was constructed, highlighting the linear trend to visualize the association.

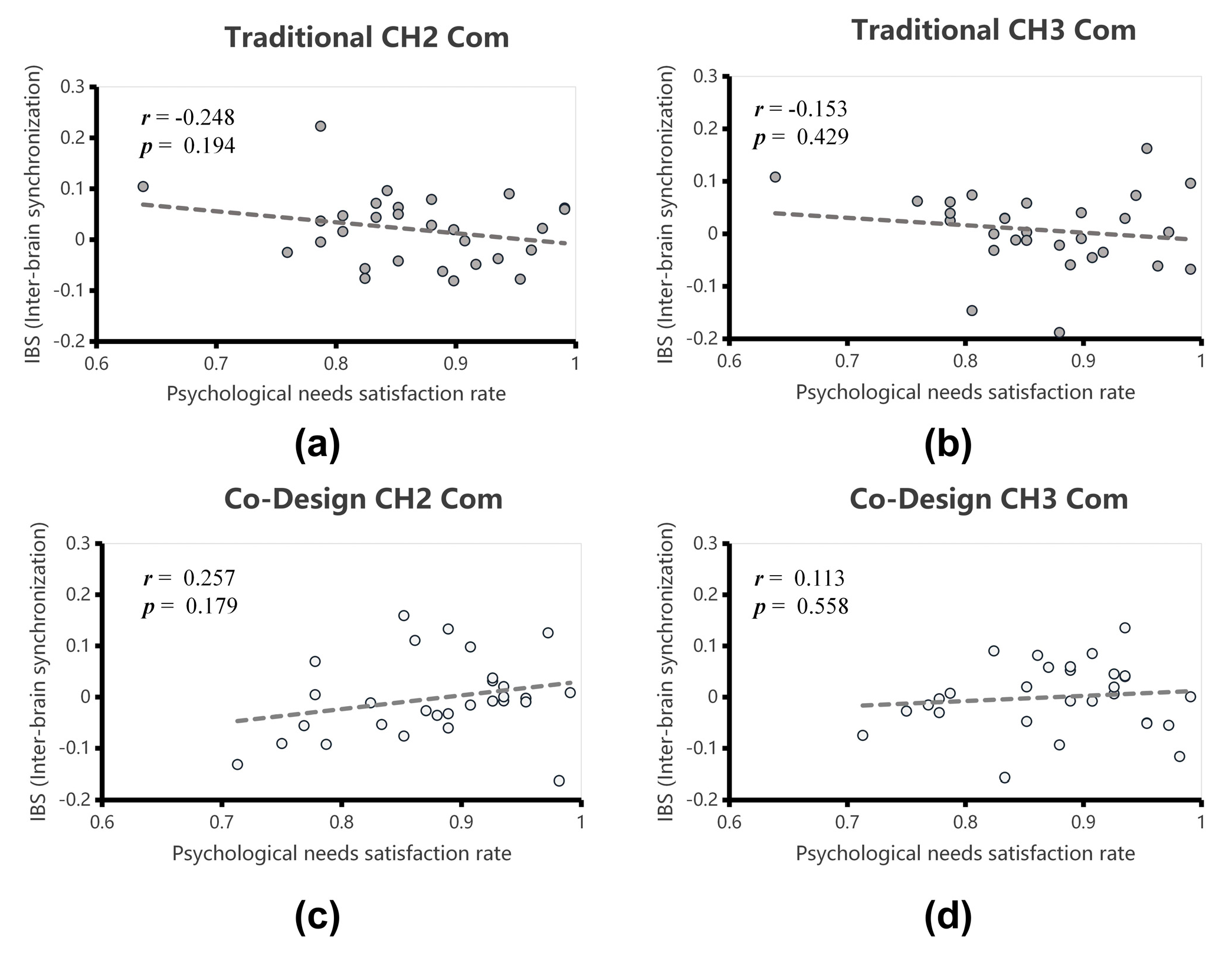

The correlation between IBS and psychological needs satisfaction rate of CH2 and CH3 under Traditional and Co-design tasks in Com Block as shown in

Figure 10. The results showed that there was neither a significant correlation between IBS and psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 nor CH3 under Traditional, with negative values for r (T2C: r=-0.248, p=0.194, T3C: r=-0.153, p=0.429). There was also no significant correlation between IBS and psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 and CH3 under Co-design, with positive values for r (C2C: r=0.257, p=0.179, C3C: r=0.113, p=0.558) .

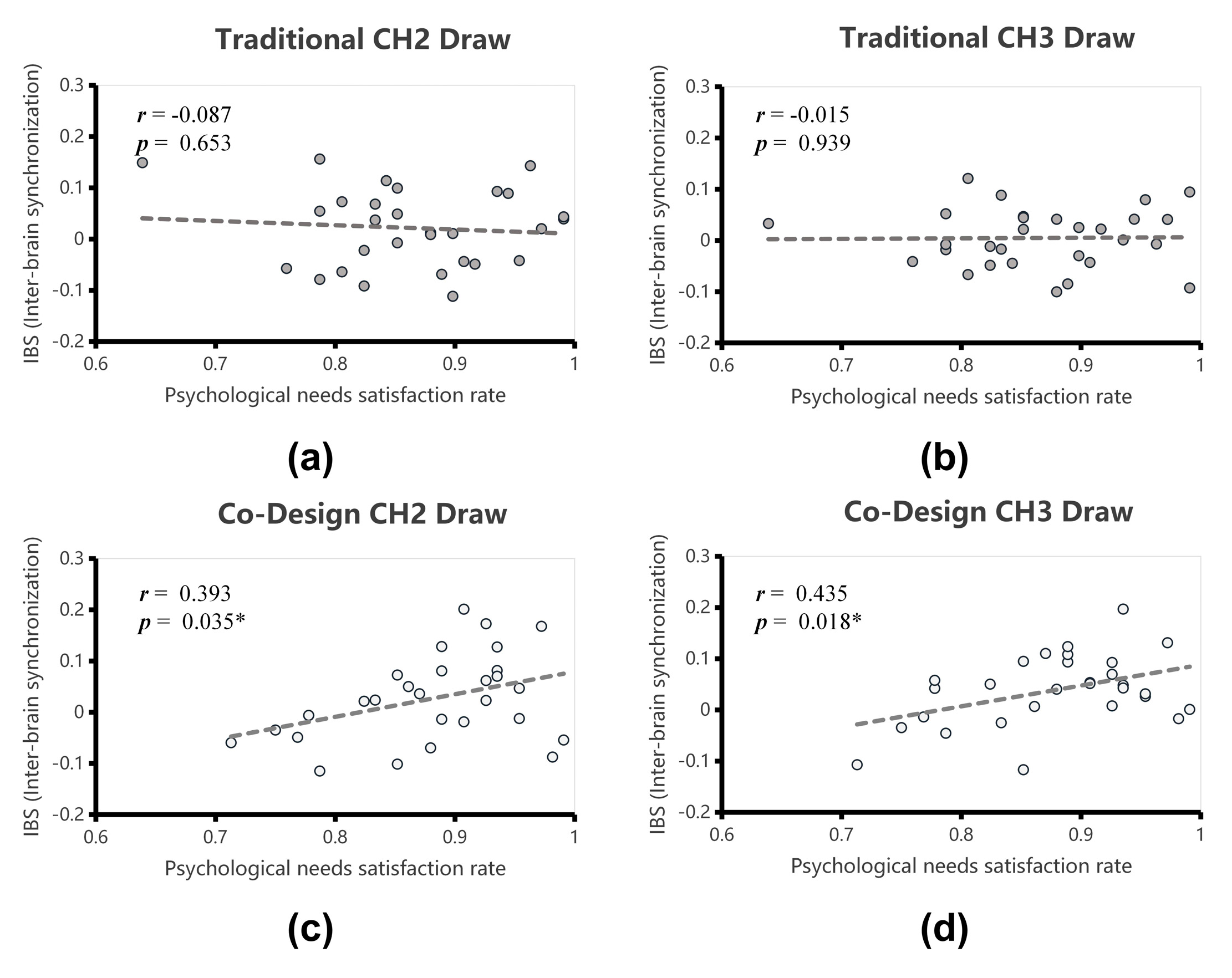

The correlation between IBS and psychological needs satisfaction rate of CH2 and CH3 under Traditional and Co-design tasks in Draw Block is shown as shown in

Figure 11. The results showed that there was neither a significant correlation between IBS and psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 nor CH3 under Traditional, with negative values for r (T2D: r=-0.087, p=0.653, T3D: r=-0.015, p=0.939). However, under Co-design, there was a significant positive correlation between IBS and psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 and CH3, with positive values for r (C2D: r=0.393, p=0.035, C3D: r=0.435, p=0.018).

5. Conclusions

This research employed dual functional near-infrared spectroscopy systems to monitor and compare neural activation patterns between design professionals and non-design specialists during various design task modalities. The study found that overall, participants will activate DLPFC and BROCA brain region related channels in both Traditional and Co-design tasks, and the increase in IBS is more significant in Co-design tasks. It was also found that regardless of the design task mode, the Draw block performed later showed higher consistency than the Com block performed first, and it was inferred that this was due to the consensus reached by different role parties after the gradual promotion of the stage. In addition, this experiment found that a higher level of collaboration in Co-design can be directly reflected in the satisfaction of psychological needs in the design results, demonstrating the correlation between collaboration and positive creative outcomes. From the perspective of applied science, this study observed the collaboration process and outcomes of two design patterns, analyzed the relationship between the two, and obtained the correlation between collaboration and outcomes. It emphasized the activation of IBS brain regions behind this process, providing empirical evidence for the characteristics of Co-design. The sample data created in this experiment is relatively small, and in further research, the number of subjects can be increased to further improve the accuracy of the data. The experimental paradigm is based on the situational reconstruction of existing design patterns, lacking separate analysis of the elements in the generative toolkit during Co-design processes. Further research can focus on this and provide empirical evidence related to collaboration.

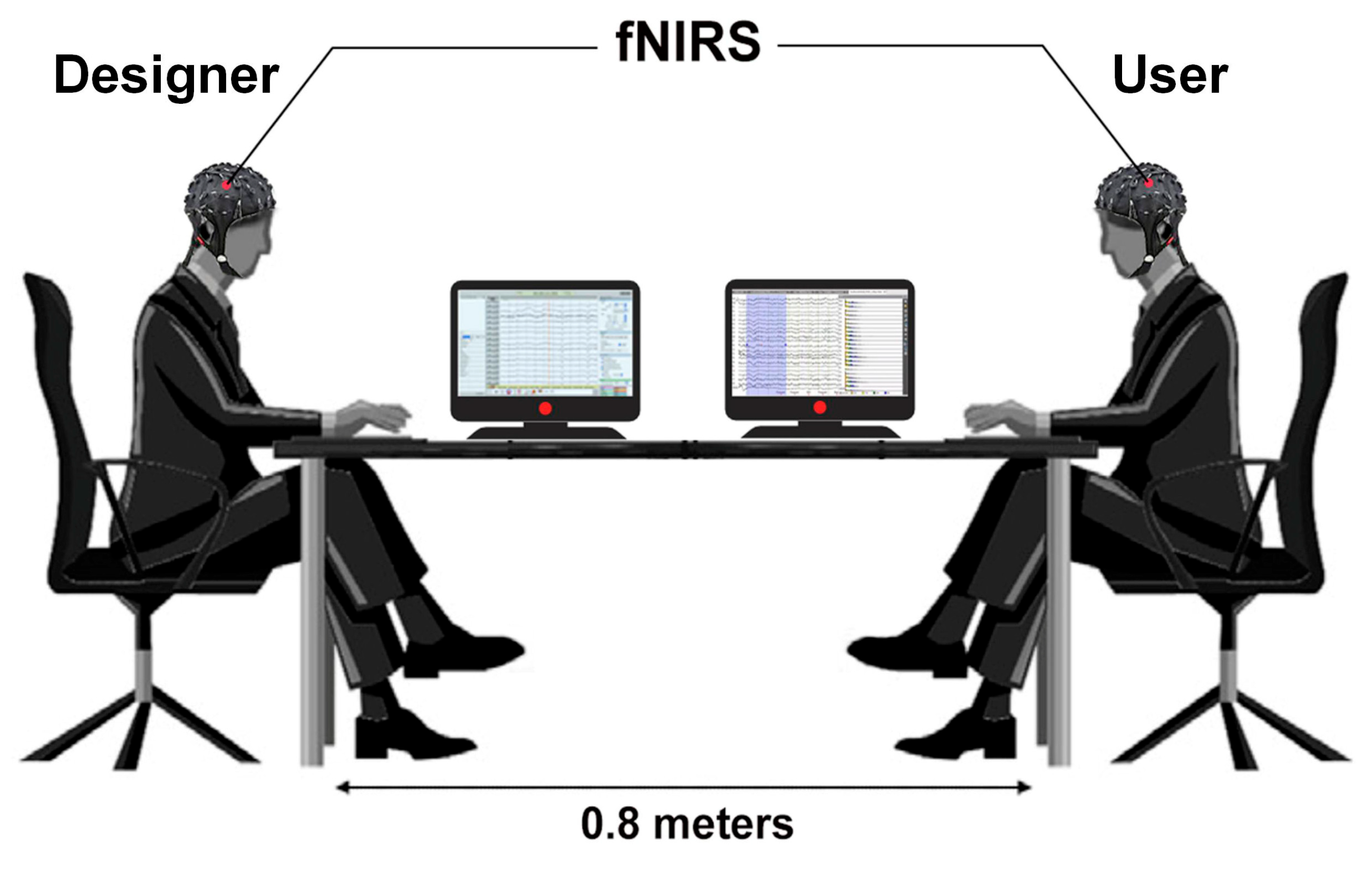

Figure 1.

Participant experimental setup demonstration.

Figure 1.

Participant experimental setup demonstration.

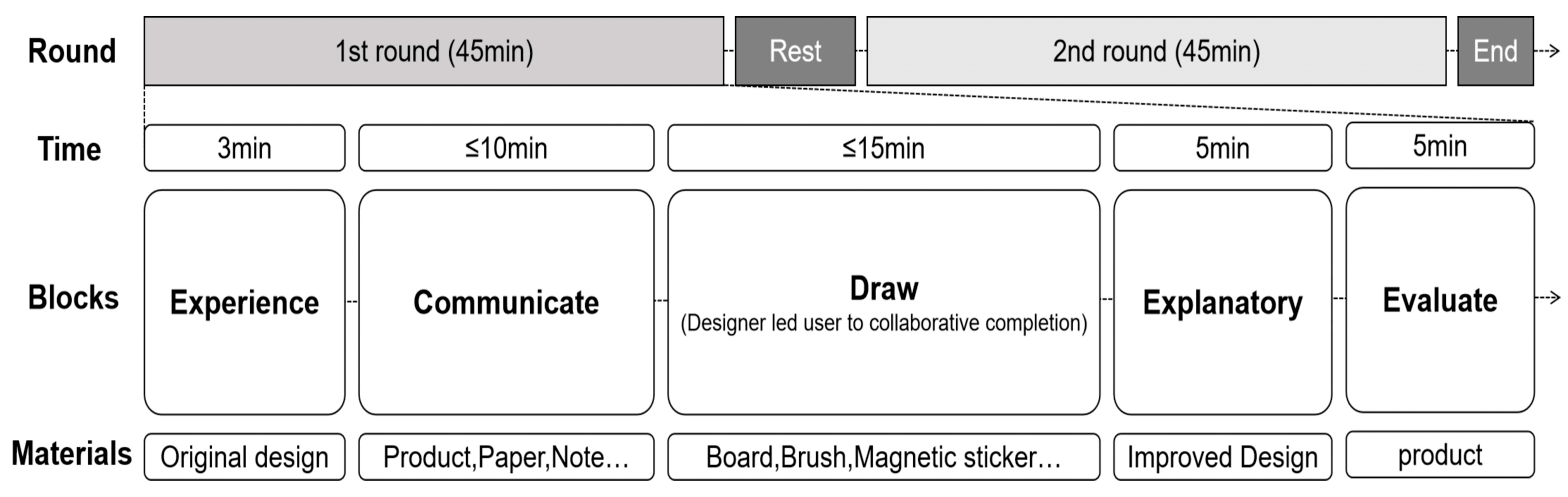

Figure 2.

Experimental procedures, showing two round trials. The entire task consisted of Five task blocks :Experience,Communicate,Draw,Explanatory,Evaluate.

Figure 2.

Experimental procedures, showing two round trials. The entire task consisted of Five task blocks :Experience,Communicate,Draw,Explanatory,Evaluate.

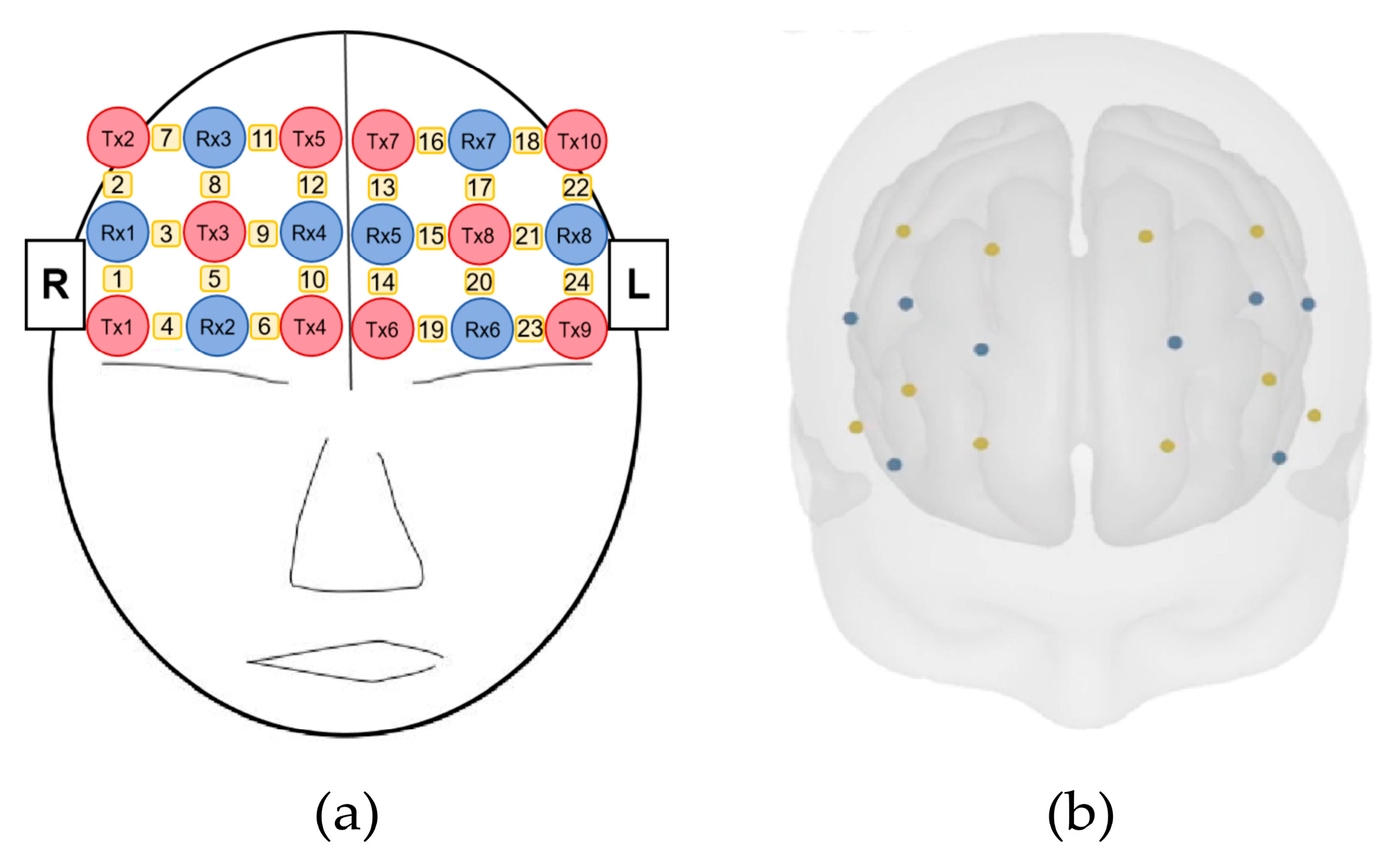

Figure 3.

A pair of Artinis Brite 24 fNIRS devices for restoring experimental channel settings.

Figure 3.

A pair of Artinis Brite 24 fNIRS devices for restoring experimental channel settings.

Figure 4.

Cap configuration. (a)Red circles indicate emitters; blue circles indicate detectors. Green squares indicate measurement channels between emitters and detectors;(b)The positioning of acquisition points in the Oxysoft software.

Figure 4.

Cap configuration. (a)Red circles indicate emitters; blue circles indicate detectors. Green squares indicate measurement channels between emitters and detectors;(b)The positioning of acquisition points in the Oxysoft software.

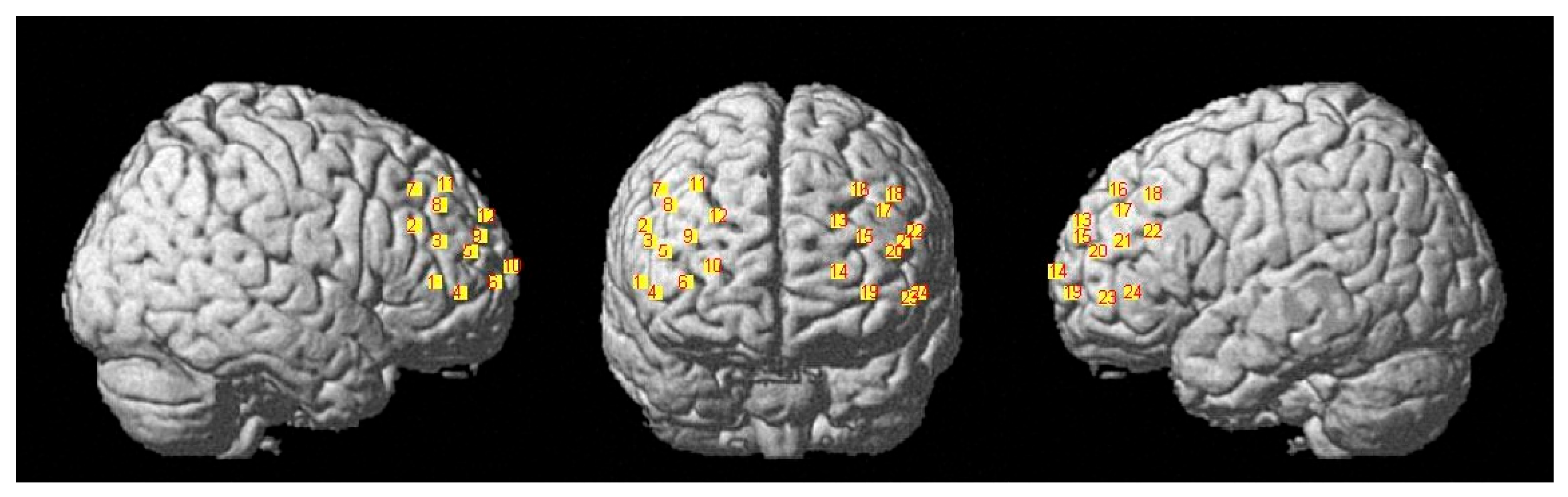

Figure 5.

Right, front, and left optical poles localization brain map.

Figure 5.

Right, front, and left optical poles localization brain map.

Figure 6.

The CH4 IBS increases in the DLPFC & BROCA during Traditional and Co-designs rounds: (a) Traditional; (b) Co-design.

Figure 6.

The CH4 IBS increases in the DLPFC & BROCA during Traditional and Co-designs rounds: (a) Traditional; (b) Co-design.

Figure 7.

Topographic map of IBS t-values across different blocks under Traditional and Co-designs rounds, Color indicates the t value: (a) Traditional Com; (b) Co-design Com; (c) Traditional Draw; (d) Co-design Draw.

Figure 7.

Topographic map of IBS t-values across different blocks under Traditional and Co-designs rounds, Color indicates the t value: (a) Traditional Com; (b) Co-design Com; (c) Traditional Draw; (d) Co-design Draw.

Figure 8.

Topographic map of t-values representing the differences in IBS between Draw and Com blocks , Color indicates the t value: (a) Traditional; (b) Co-design.

Figure 8.

Topographic map of t-values representing the differences in IBS between Draw and Com blocks , Color indicates the t value: (a) Traditional; (b) Co-design.

Figure 9.

Line graph of IBS across significant channels under Com and Draw block conditions: (a) Traditional; (b) Co-design.

Figure 9.

Line graph of IBS across significant channels under Com and Draw block conditions: (a) Traditional; (b) Co-design.

Figure 10.

Scatter plot of IBS versus psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 and CH3 under the Com block condition: (a) Traditional CH2 Com (T2C); (b) Traditional CH3 Com (T3C); (c) Co-design CH2 Com (C2C); (d) Co-design CH3 Com (C3C).

Figure 10.

Scatter plot of IBS versus psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 and CH3 under the Com block condition: (a) Traditional CH2 Com (T2C); (b) Traditional CH3 Com (T3C); (c) Co-design CH2 Com (C2C); (d) Co-design CH3 Com (C3C).

Figure 11.

Scatter plot of IBS versus psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 and CH3 under the Draw block condition: (a) Traditional CH2 Draw (T2D); (b) Traditional CH3 Draw (T3D); (c) Co-design CH2 Draw (C2D); (d) Co-design CH3 Draw (C3D).

Figure 11.

Scatter plot of IBS versus psychological needs satisfaction rate in CH2 and CH3 under the Draw block condition: (a) Traditional CH2 Draw (T2D); (b) Traditional CH3 Draw (T3D); (c) Co-design CH2 Draw (C2D); (d) Co-design CH3 Draw (C3D).

Table 1.

Table of significant channel data related to DLPFC and BROCA.

Table 1.

Table of significant channel data related to DLPFC and BROCA.

| Channel |

No. |

Brain area |

PR |

t |

p |

Cohen's d |

| CH2 |

44 |

pars opercularis, part of Broca's area |

0.086 |

2.288 |

0.036 |

0.418 |

| 45 |

pars triangularis Broca's area |

0.914 |

| CH3 |

45 |

pars triangularis Broca's area |

0.901 |

3.047 |

0.010 |

0.556 |

| 46 |

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

0.099 |

| CH4 |

45 |

pars triangularis Broca's area |

0.116 |

3.540 |

0.005 |

0.646 |

| 46 |

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

0.884 |

| CH11 |

9 |

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

0.912 |

2.665 |

0.018 |

0.486 |

| 46 |

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

0.088 |

| CH24 |

45 |

pars triangularis Broca's area |

0.807 |

4.290 |

0.005 |

0.783 |

| 46 |

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

0.193 |