Submitted:

12 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Characteristics

2.2. Collection of the Tissue Samples

2.3. Formation of the Study Groups

2.4. Characteristics of the Study Groups

2.5. MiRNA Isolation from the FFPE

2.6. Profiling of miRNA

2.7. Statystical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Profiling of miRNAs in Rectal Cancer Tissue

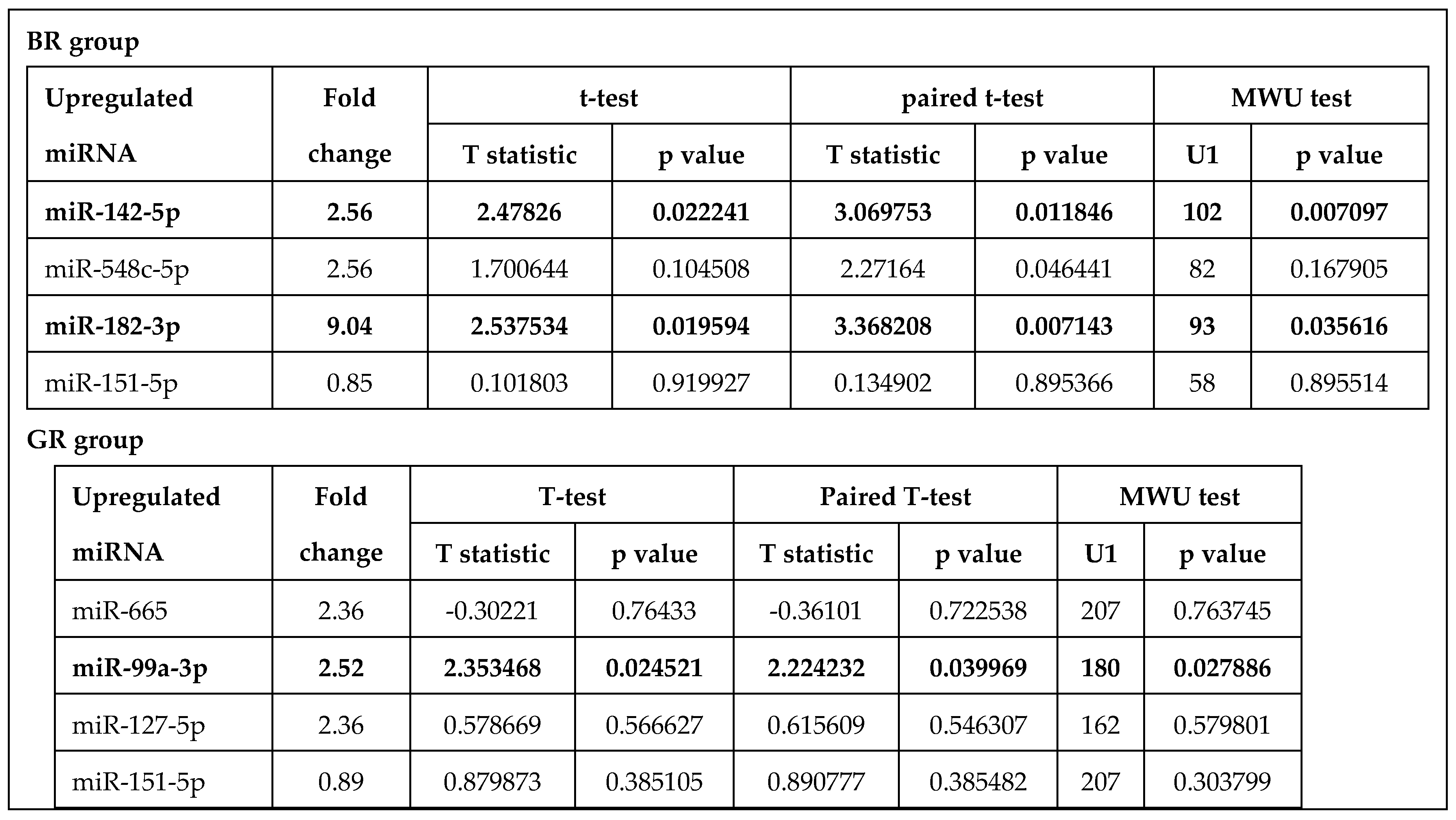

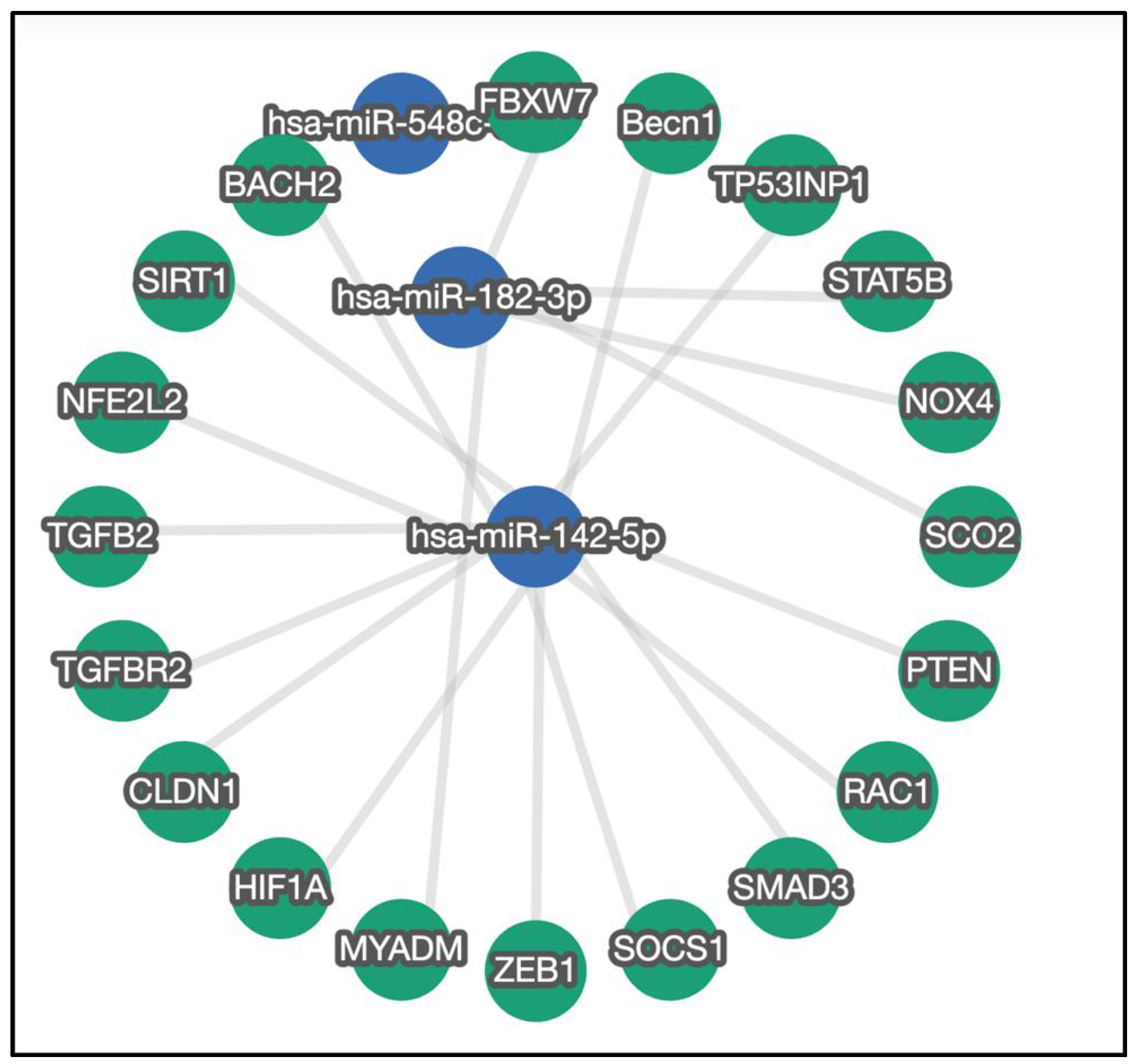

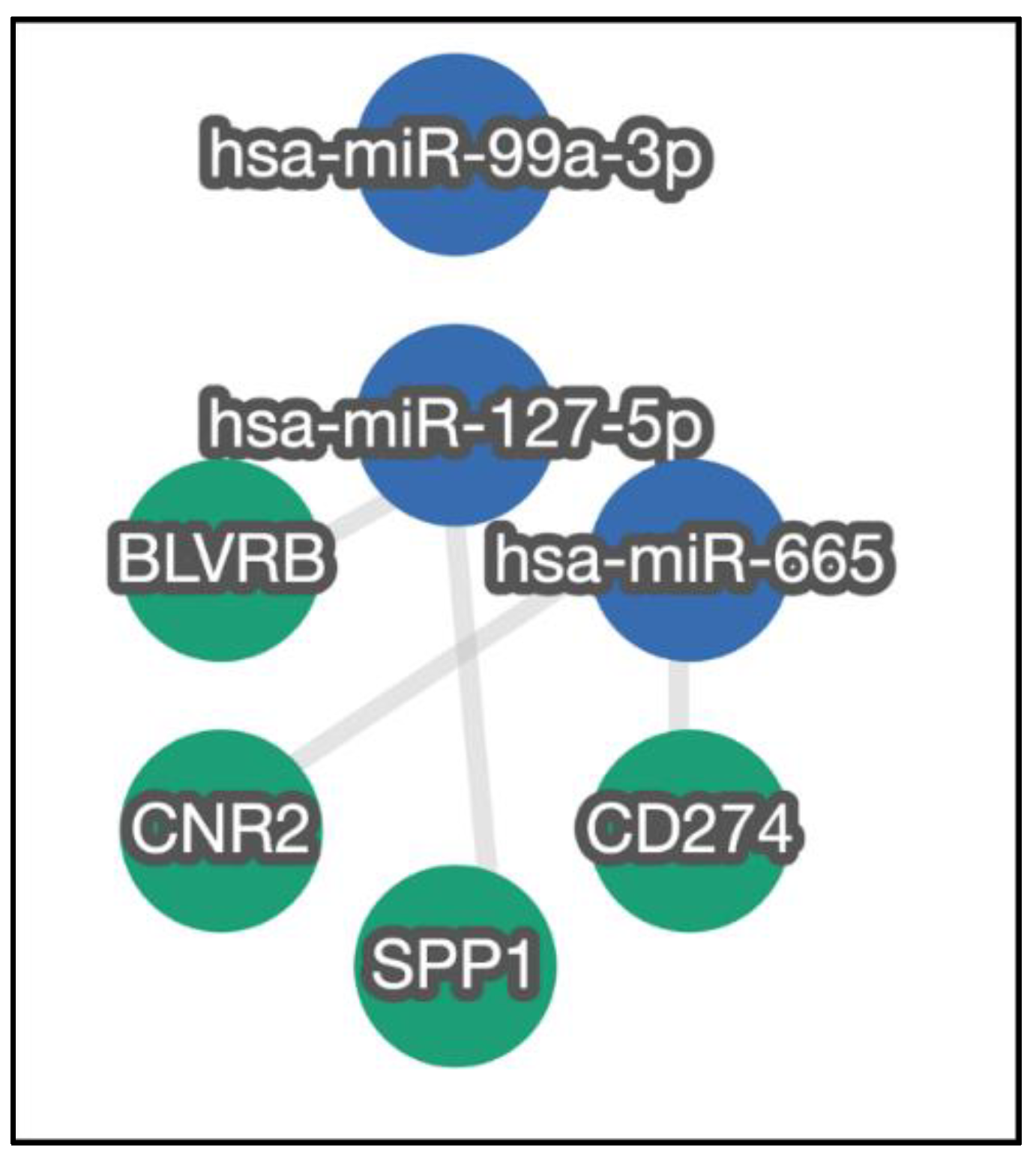

3.2. Verification of Selected miRNA

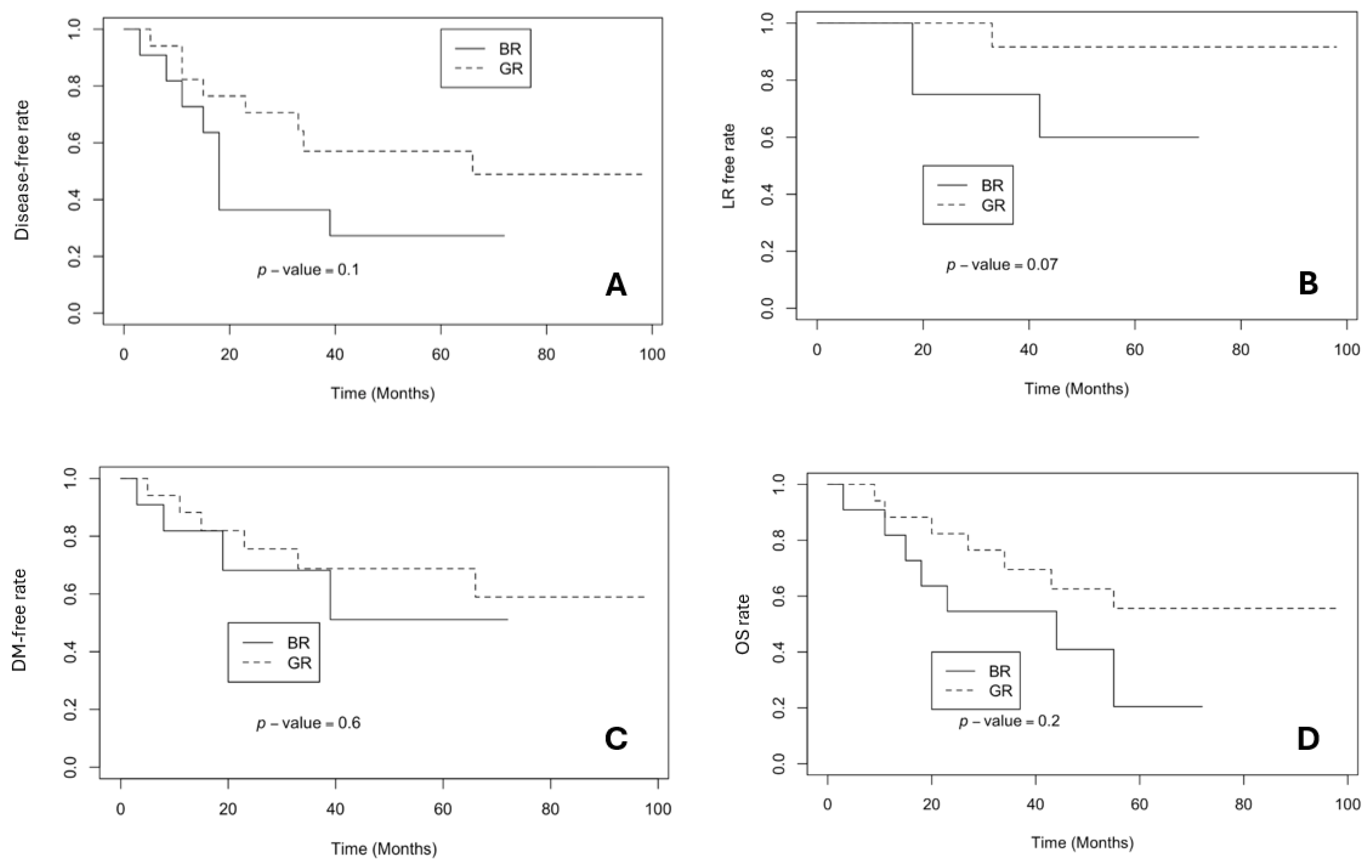

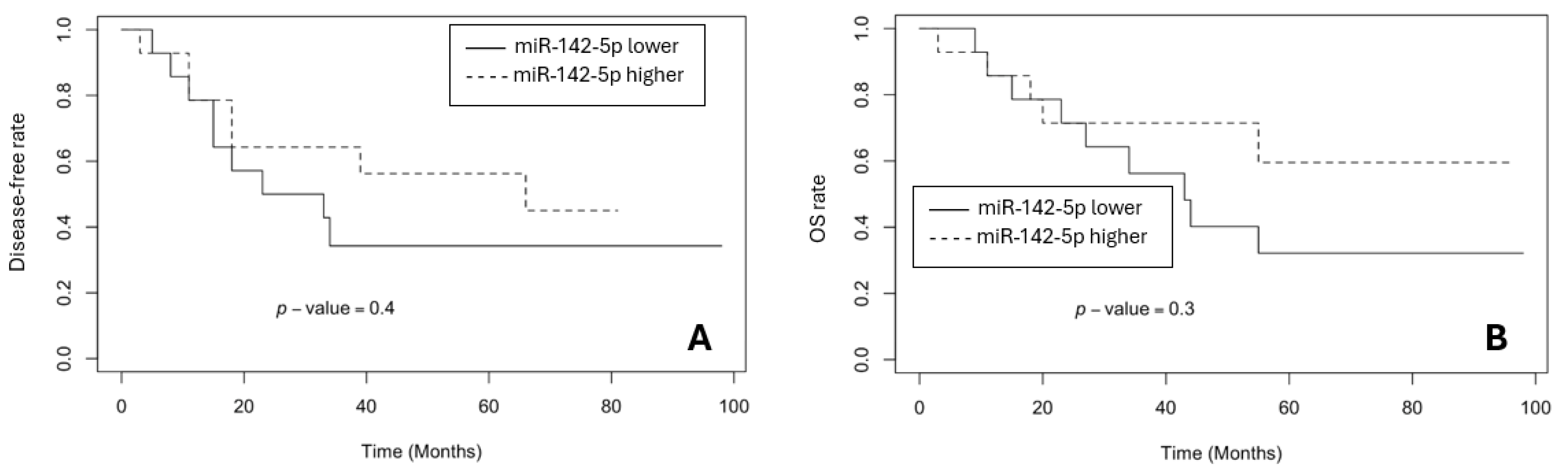

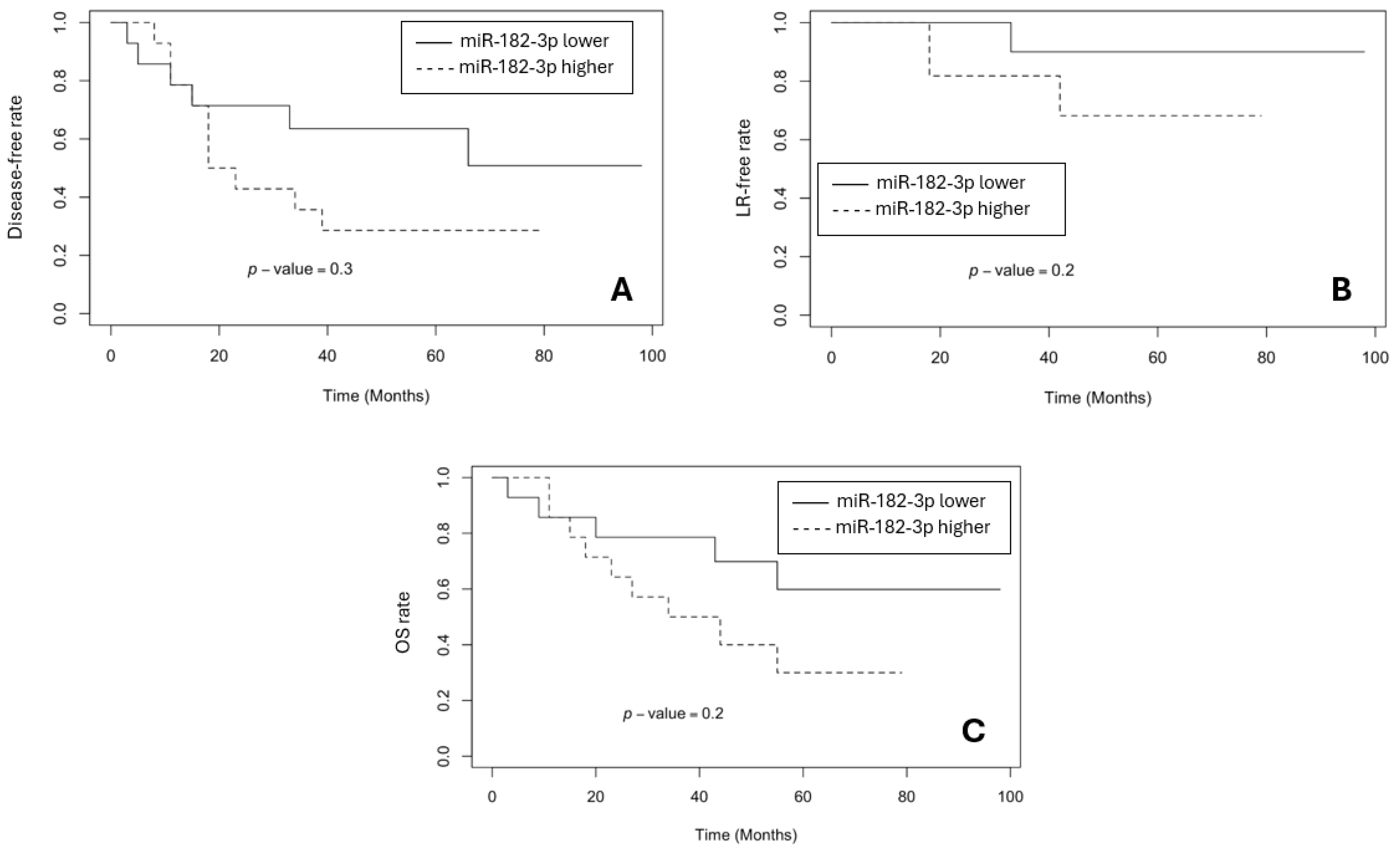

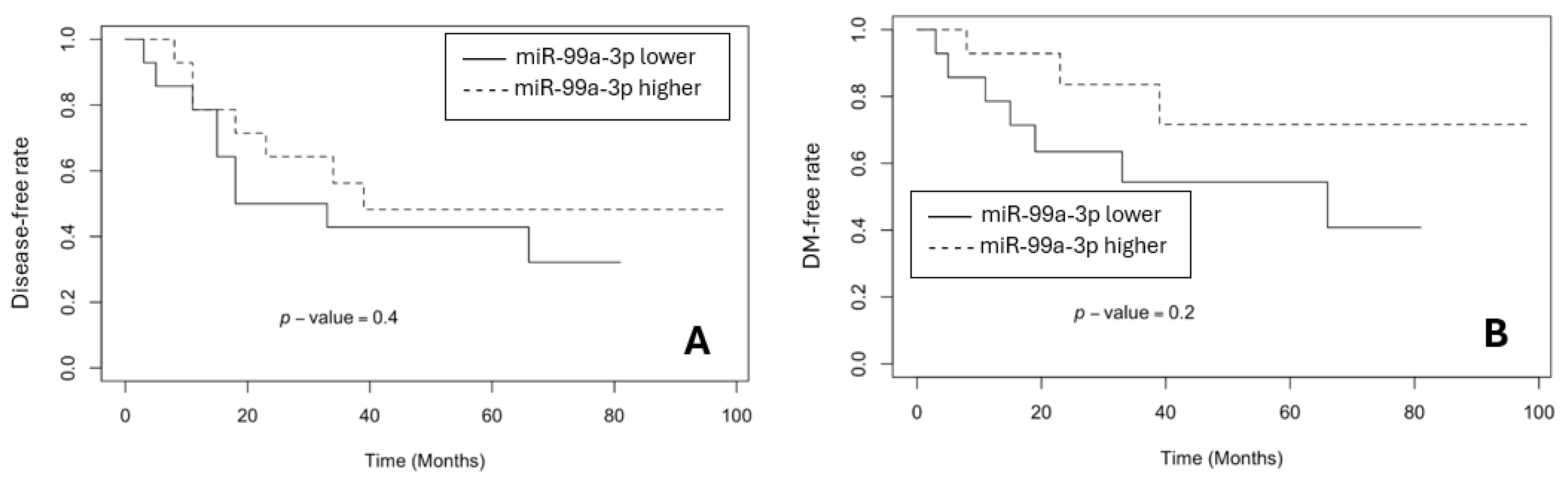

3.3. The Survival Rates in BR and GR Groups

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| miRNAs | micro ribonucleic acids |

| nCRT | neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy |

| GR | good response |

| BR | bad response |

| TRG | tumour regression grading |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| cCR | clinical complete response |

| pCR | pathological complete response |

| onco-miRNAs | oncogenic miRNAs |

| FFPE | formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded |

| HE | haematoxylin-eosin |

| CT-scan | computed tomography scan |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| CEA | carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CA19-9 | carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| Gy | gray |

| i/v | intravenous |

| 5FU | fluorouracil |

| FOLFOX6 | leucovorin calcium (folinic acid), fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin |

| AR | anterior resection |

| HP | Hartmann’s Procedure |

| APR | abdominoperineal resection |

| TR | transanal resection |

| RL | resection line |

| cDNA | complementary DNA |

| LRFS | local recurrence-free survival |

| DMFS | distant metastases-free survival |

| DFS | disease-free survival |

| OS | overall survival |

Appendix A

| hsa-miR-7-5p | hsa-miR-16-5p | hsa-miR-99b-5p | hsa-miR-654-5p | hsa-miR-631 |

| hsa-miR-217-5p | hsa-miR-98-5p | hsa-miR-431-5p | hsa-miR-545-3p | hsa-miR-34c-5p |

| hsa-miR-337-5p | hsa-miR-185-5p | hsa-miR-23b-3p | hsa-miR-29b-2-5p | hsa-miR-211-5p |

| hsa-miR-328-3p | hsa-miR-25-3p | hsa-miR-367-3p | hsa-miR-491-5p | hsa-miR-454-3p |

| hsa-miR-374b-3p | hsa-miR-765 | hsa-miR-505-3p | hsa-miR-92b-3p | hsa-let-7f-5p |

| hsa-miR-143-3p | hsa-miR-24-3p | hsa-miR-18a-5p | hsa-miR-665 | hsa-miR-30e-5p |

| hsa-miR-623 | hsa-miR-369-5p | hsa-miR-92a-3p | hsa-miR-506-3p | hsa-miR-34a-5p |

| hsa-miR-520c-3p | hsa-miR-425-5p | hsa-miR-500a-5p | hsa-miR-363-3p | hsa-miR-663a |

| hsa-miR-557 | hsa-miR-590-5p | hsa-miR-887-3p | hsa-miR-132-3p | hsa-miR-518e-3p |

| hsa-miR-218-5p | hsa-miR-760 | hsa-miR-491-3p | hsa-miR-651-5p | hsa-miR-29b-3p |

| hsa-miR-136-5p | hsa-miR-574-3p | hsa-miR-423-3p | hsa-miR-628-3p | hsa-miR-658 |

| hsa-miR-127-5p | hsa-miR-130b-3p | hsa-miR-126-3p | hsa-miR-432-5p | hsa-miR-572 |

| hsa-miR-140-5p | hsa-miR-30c-5p | hsa-miR-421 | hsa-miR-154-3p | hsa-miR-802 |

| hsa-miR-31-3p | hsa-miR-133b | hsa-miR-376b-3p | hsa-miR-27a-3p | hsa-miR-521 |

| hsa-miR-20b-3p | hsa-miR-524-5p | hsa-miR-302c-3p | hsa-miR-376c-3p | hsa-miR-433-3p |

| hsa-miR-325 | hsa-miR-23a-3p | hsa-miR-625-3p | hsa-miR-940 | hsa-miR-660-5p |

| hsa-miR-509-3-5p | hsa-miR-193b-3p | hsa-miR-339-5p | hsa-miR-22-5p | hsa-let-7c-5p |

| hsa-miR-210-3p | hsa-miR-501-5p | hsa-miR-873-5p | hsa-miR-224-5p | hsa-miR-28-5p |

| hsa-miR-199b-5p | hsa-miR-518c-5p | hsa-miR-323a-3p | hsa-miR-885-5p | hsa-miR-324-5p |

| hsa-miR-194-5p | hsa-miR-130a-3p | hsa-miR-181d-5p | hsa-miR-320a-3p | hsa-miR-219a-5p |

| hsa-let-7g-5p | hsa-miR-933 | hsa-miR-125a-5p | hsa-miR-18b-5p | hsa-miR-19b-3p |

| hsa-miR-203a-3p | hsa-miR-379-5p | hsa-miR-129-5p | hsa-miR-187-3p | hsa-miR-526b-5p |

| hsa-miR-181a-3p | hsa-miR-452-5p | hsa-miR-492 | hsa-miR-516b-5p | hsa-miR-215-5p |

| hsa-miR-137-3p | hsa-miR-589-5p | hsa-miR-20a-5p | hsa-miR-302c-5p | hsa-miR-30b-5p |

| hsa-miR-551b-3p | hsa-miR-141-3p | hsa-miR-374b-5p | hsa-miR-548b-3p | hsa-miR-184 |

| hsa-miR-524-3p | hsa-miR-342-3p | hsa-miR-302d-3p | hsa-miR-186-5p | hsa-miR-422a |

| hsa-miR-486-5p | hsa-miR-668-3p | hsa-miR-346 | hsa-miR-199a-5p | hsa-miR-199a-3p |

| hsa-miR-329-3p | hsa-miR-934 | hsa-miR-151a-3p | hsa-miR-155-5p | hsa-miR-335-5p |

| hsa-miR-487b-3p | hsa-miR-101-3p | hsa-miR-493-3p | hsa-miR-107 | hsa-miR-519a-3p |

| hsa-miR-138-5p | hsa-miR-539-5p | hsa-miR-122-5p | hsa-miR-302b-3p | hsa-miR-21-5p |

| hsa-miR-191-5p | hsa-miR-331-3p | hsa-miR-99a-3p | hsa-miR-662 | hsa-miR-129-2-3p |

| hsa-miR-378a-3p | hsa-miR-499a-5p | hsa-miR-361-5p | hsa-miR-519d-3p | hsa-miR-26b-5p |

| hsa-miR-103a-3p | hsa-miR-196a-5p | hsa-miR-202-3p | hsa-miR-485-3p | hsa-miR-214-3p |

| hsa-miR-890 | hsa-miR-888-5p | hsa-miR-125b-5p | hsa-miR-200b-3p | hsa-miR-32-5p |

| hsa-miR-423-5p | hsa-miR-330-3p | hsa-miR-503-5p | hsa-miR-337-3p | hsa-miR-324-3p |

| hsa-miR-221-3p | hsa-miR-570-3p | hsa-miR-204-5p | hsa-miR-494-3p | hsa-miR-488-3p |

| hsa-miR-301b-3p | hsa-miR-518c-3p | hsa-miR-30d-5p | hsa-miR-371a-3p | hsa-miR-371a-5p |

| hsa-miR-550a-5p | hsa-miR-200a-3p | hsa-miR-301a-3p | hsa-miR-637 | hsa-miR-455-5p |

| hsa-miR-532-5p | hsa-miR-188-5p | hsa-miR-362-5p | hsa-miR-144-3p | hsa-miR-891a-5p |

| hsa-miR-99a-5p | hsa-miR-26a-5p | hsa-miR-30b-3p | hsa-miR-16-1-3p | hsa-miR-549a-3p |

| hsa-miR-205-5p | hsa-miR-498-5p | hsa-miR-296-5p | hsa-miR-216a-5p | hsa-miR-148a-3p |

| hsa-miR-518b | hsa-miR-148b-3p | hsa-miR-20b-5p | hsa-miR-424-5p | hsa-miR-146a-5p |

| hsa-miR-19a-3p | hsa-miR-127-3p | hsa-miR-147a | hsa-miR-921 | hsa-miR-139-5p |

| hsa-miR-150-5p | hsa-miR-598-3p | hsa-miR-198 | hsa-miR-513a-5p | hsa-miR-373-5p |

| hsa-miR-15a-5p | hsa-miR-96-5p | hsa-miR-375-3p | hsa-miR-140-3p | hsa-miR-149-5p |

| hsa-let-7d-3p | hsa-let-7d-5p | hsa-miR-517a-3p | hsa-miR-181a-5p | hsa-miR-642a-5p |

| hsa-miR-608 | hsa-miR-135b-5p | hsa-miR-361-3p | hsa-miR-10a-5p | hsa-miR-31-5p |

| hsa-miR-671-5p | hsa-miR-495-3p | hsa-miR-21-3p | hsa-miR-106a-5p | hsa-miR-451a |

| hsa-miR-497-5p | hsa-miR-299-5p | hsa-miR-373-3p | hsa-miR-182-5p | hsa-miR-620 |

| hsa-miR-877-5p | hsa-miR-34c-3p | hsa-miR-518f-3p | hsa-miR-370-3p | hsa-miR-27b-3p |

| hsa-miR-187-5p | hsa-miR-596 | hsa-miR-222-3p | hsa-miR-576-5p | hsa-miR-523-3p |

| hsa-miR-10b-5p | hsa-miR-744-5p | hsa-miR-617 | hsa-miR-425-3p | hsa-miR-374a-5p |

| hsa-let-7i-5p | hsa-miR-145-5p | hsa-miR-154-5p | hsa-miR-450a-5p | hsa-miR-92a-1-5p |

| hsa-miR-202-5p | hsa-miR-622 | hsa-miR-708-5p | hsa-miR-411-5p | hsa-miR-219a-1-3p |

| hsa-miR-652-3p | hsa-miR-516a-5p | hsa-let-7b-5p | hsa-miR-216b-5p | hsa-miR-1913 |

| hsa-miR-126-5p | hsa-let-7a-5p | hsa-miR-95-3p | hsa-miR-106b-5p | hsa-miR-1245a |

| hsa-miR-30e-3p | hsa-miR-96-3p | hsa-miR-517c-3p | hsa-miR-22-3p | hsa-miR-522-3p |

| hsa-miR-181c-5p | hsa-miR-185-3p | hsa-miR-151a-5p | hsa-miR-510-5p | hsa-miR-571 |

| hsa-miR-9-3p | hsa-miR-615-3p | hsa-miR-502-5p | hsa-miR-212-3p | hsa-miR-323a-5p |

| hsa-miR-548c-3p | hsa-miR-128-3p | hsa-miR-345-5p | hsa-miR-525-5p | hsa-miR-592 |

| hsa-miR-152-3p | hsa-miR-766-3p | hsa-miR-509-3p | hsa-miR-542-5p | hsa-miR-487a-3p |

| hsa-miR-93-5p | hsa-miR-206 | hsa-miR-134-5p | hsa-miR-576-3p | hsa-miR-1249-3p |

| hsa-miR-365a-3p | hsa-miR-298 | hsa-miR-382-5p | hsa-miR-583 | hsa-miR-25-5p |

| hsa-miR-29c-3p | hsa-miR-193a-5p | hsa-miR-490-3p | hsa-miR-483-3p | hsa-miR-922 |

| hsa-miR-372-3p | hsa-miR-449b-5p | hsa-miR-200c-3p | hsa-miR-582-5p | hsa-miR-124-5p |

| hsa-miR-133a-3p | hsa-miR-520d-5p | hsa-miR-30a-5p | hsa-miR-183-5p | hsa-miR-1264 |

| hsa-miR-124-3p | hsa-miR-192-5p | hsa-miR-181b-5p | hsa-miR-33b-5p | hsa-miR-504-5p |

| hsa-miR-190a-5p | hsa-miR-29a-3p | hsa-miR-33a-5p | hsa-miR-193a-3p | hsa-miR-138-1-3p |

| hsa-miR-302a-3p | hsa-miR-18a-3p | hsa-miR-195-5p | hsa-miR-153-3p | hsa-miR-502-3p |

| hsa-miR-595 | hsa-miR-383-5p | hsa-miR-874-3p | hsa-let-7e-5p | hsa-miR-490-5p |

| hsa-miR-602 | hsa-miR-9-5p | hsa-miR-135a-5p | hsa-miR-409-3p | hsa-miR-567 |

| hsa-miR-223-3p | hsa-miR-142-5p | hsa-miR-26a-2-3p | hsa-miR-100-5p | hsa-miR-18b-3p |

| hsa-miR-627-5p | hsa-miR-363-5p | hsa-miR-146b-5p | hsa-miR-629-5p | hsa-miR-125a-3p |

| hsa-miR-34b-3p | hsa-miR-147b-3p | hsa-miR-412-3p | hsa-miR-484 | hsa-miR-653-5p |

| hsa-miR-410-3p | hsa-miR-197-3p | hsa-miR-1-3p | hsa-miR-429 | hsa-miR-891b |

| hsa-miR-17-5p | hsa-miR-597-5p | hsa-miR-299-3p | hsa-miR-30c-2-3p | hsa-miR-144-5p |

| hsa-miR-376a-3p | hsa-miR-326 | hsa-miR-142-3p | hsa-miR-518a-3p | hsa-miR-1538 |

| hsa-miR-514a-3p | hsa-miR-15b-5p | hsa-miR-338-3p | hsa-miR-340-5p | hsa-miR-384 |

| hsa-miR-512-5p | hsa-miR-105-5p | hsa-miR-584-5p | hsa-miR-508-3p | hsa-miR-196b-3p |

| hsa-miR-449a | hsa-miR-196b-5p | hsa-miR-377-3p | hsa-miR-381-3p | hsa-miR-649 |

| hsa-miR-143-5p | hsa-miR-892a | hsa-miR-141-5p | hsa-miR-520h | hsa-miR-518d-3p |

| hsa-miR-1207-5p | hsa-miR-10b-3p | hsa-miR-1269a | hsa-miR-769-5p | hsa-miR-569 |

| hsa-miR-943 | hsa-miR-122-3p | hsa-miR-501-3p | hsa-miR-612 | hsa-miR-125b-1-3p |

| hsa-miR-675-3p | hsa-miR-100-3p | hsa-miR-15b-3p | hsa-miR-1237-3p | hsa-miR-218-2-3p |

| hsa-miR-200b-5p | hsa-miR-769-3p | hsa-miR-146b-3p | hsa-miR-1908-5p | hsa-miR-519c-3p |

| hsa-miR-519e-5p | hsa-miR-300 | hsa-miR-222-5p | hsa-miR-1260a | hsa-miR-554 |

| hsa-miR-942-5p | hsa-miR-518e-5p | hsa-miR-601 | hsa-miR-182-3p | hsa-miR-938 |

| hsa-miR-450b-3p | hsa-miR-489-3p | hsa-miR-924 | hsa-miR-365b-5p | hsa-miR-1243 |

| hsa-miR-553 | hsa-miR-937-3p | hsa-miR-29a-5p | hsa-miR-508-5p | hsa-miR-708-3p |

| hsa-miR-605-5p | hsa-miR-381-5p | hsa-let-7a-2-3p | hsa-miR-671-3p | hsa-miR-1185-5p |

| hsa-miR-24-2-5p | hsa-miR-640 | hsa-miR-520f-3p | hsa-miR-941 | hsa-miR-512-3p |

| hsa-miR-23a-5p | hsa-miR-148b-5p | hsa-miR-101-5p | hsa-miR-23b-5p | hsa-miR-587 |

| hsa-miR-27b-5p | hsa-miR-29c-5p | hsa-miR-520a-3p | hsa-miR-591 | hsa-miR-603 |

| hsa-miR-759 | hsa-miR-499a-3p | hsa-miR-548m | hsa-miR-26b-3p | hsa-miR-1184 |

| hsa-miR-770-5p | hsa-let-7f-1-3p | hsa-miR-517-5p | hsa-miR-519b-3p | hsa-miR-20a-3p |

| hsa-miR-585-3p | hsa-miR-382-3p | hsa-miR-448 | hsa-miR-30d-3p | hsa-miR-588 |

| hsa-miR-376a-5p | hsa-miR-609 | hsa-miR-1296-5p | hsa-miR-518d-5p | hsa-miR-455-3p |

| hsa-miR-507 | hsa-miR-10a-3p | hsa-miR-1537-3p | hsa-miR-212-5p | hsa-miR-582-3p |

| hsa-miR-520b-3p | hsa-miR-106a-3p | hsa-miR-920 | hsa-miR-520e-3p | hsa-miR-409-5p |

| hsa-miR-302f | hsa-let-7e-3p | hsa-miR-1247-5p | hsa-miR-646 | hsa-miR-452-3p |

| hsa-miR-28-3p | hsa-miR-580-3p | hsa-miR-19b-2-5p | hsa-miR-519e-3p | hsa-miR-19b-1-5p |

| hsa-miR-875-5p | hsa-miR-761 | hsa-miR-558 | hsa-miR-626 | hsa-miR-610 |

| hsa-miR-219a-2-3p | hsa-miR-643 | hsa-miR-106b-3p | hsa-miR-26a-1-3p | hsa-miR-511-5p |

| hsa-miR-1183 | hsa-miR-618 | hsa-miR-1258 | hsa-miR-190b | hsa-miR-200c-5p |

| hsa-miR-758-3p | hsa-miR-221-5p | hsa-miR-619-3p | hsa-miR-1471 | hsa-let-7a-3p |

| hsa-miR-1244 | hsa-miR-513b-5p | hsa-miR-208a-3p | hsa-miR-548l | hsa-miR-135a-3p |

| hsa-miR-566 | hsa-miR-411-3p | hsa-miR-17-3p | hsa-miR-586 | hsa-miR-520a-5p |

| hsa-miR-1256 | hsa-miR-19a-5p | hsa-miR-136-3p | hsa-miR-103b | hsa-miR-1468-5p |

| hsa-miR-516a-3p | hsa-miR-338-5p | hsa-miR-877-3p | hsa-miR-488-5p | hsa-miR-628-5p |

| hsa-miR-548c-5p | hsa-miR-1914-3p | hsa-miR-935 | hsa-miR-129-1-3p | hsa-miR-552-3p |

| hsa-miR-496 | hsa-miR-323b-5p | hsa-miR-224-3p | hsa-miR-192-3p | hsa-miR-145-3p |

| hsa-miR-876-3p | hsa-miR-548i | hsa-miR-624-3p | hsa-miR-632 | hsa-miR-378a-5p |

| hsa-miR-532-3p | hsa-miR-541-3p | hsa-miR-767-5p | hsa-miR-181a-2-3p | hsa-miR-7-1-3p |

| hsa-miR-654-3p | hsa-miR-1272 | hsa-miR-559 | hsa-miR-1909-3p | hsa-miR-181c-3p |

| hsa-miR-659-3p | hsa-miR-1205 | hsa-miR-449b-3p | hsa-miR-573 | hsa-miR-195-3p |

| hsa-miR-135b-3p | hsa-miR-544a | hsa-miR-205-3p | hsa-miR-302d-5p | hsa-miR-578 |

| hsa-miR-641 | hsa-miR-431-3p | hsa-miR-604 | hsa-miR-194-3p | hsa-miR-505-5p |

| hsa-miR-2113 | hsa-miR-621 | hsa-miR-130b-5p | hsa-miR-302b-5p | hsa-miR-875-3p |

| hsa-miR-1254 | hsa-miR-556-5p | hsa-miR-149-3p | hsa-miR-551b-5p | hsa-miR-450b-5p |

| hsa-miR-661 | hsa-miR-1267 | hsa-miR-1271-5p | hsa-miR-635 | hsa-miR-876-5p |

| hsa-miR-362-3p | hsa-miR-379-3p | hsa-miR-92b-5p | hsa-miR-1911-3p | hsa-miR-1224-3p |

| hsa-miR-624-5p | hsa-miR-556-3p | hsa-miR-551a | hsa-let-7f-2-3p | hsa-miR-1539 |

| hsa-miR-27a-5p | hsa-miR-614 | hsa-miR-146a-3p | hsa-miR-155-3p | hsa-miR-663b |

| hsa-miR-744-3p | hsa-miR-616-5p | hsa-miR-218-1-3p | hsa-miR-105-3p | hsa-miR-1248 |

| hsa-miR-139-3p | hsa-miR-93-3p | hsa-miR-593-5p | hsa-miR-486-3p | hsa-miR-889-3p |

| hsa-miR-138-2-3p | hsa-miR-1972 | hsa-miR-561-3p | hsa-miR-320b | hsa-miR-1227-3p |

| hsa-miR-655-3p | hsa-miR-616-3p | hsa-miR-767-3p | hsa-miR-296-3p | hsa-miR-548h-5p |

| hsa-miR-99b-3p | hsa-miR-369-3p | hsa-miR-526b-3p | hsa-miR-7-2-3p | hsa-miR-1255b-5p |

| hsa-miR-581 | hsa-miR-2110 | hsa-miR-24-1-5p | hsa-miR-550a-3p | hsa-miR-330-5p |

| hsa-miR-191-3p | hsa-miR-548a-3p | hsa-let-7b-3p | hsa-miR-380-3p | hsa-miR-1238-3p |

| hsa-miR-32-3p | hsa-miR-634 | hsa-miR-193b-5p | hsa-miR-593-3p | hsa-miR-188-3p |

| hsa-miR-1204 | hsa-miR-320c | hsa-miR-335-3p | hsa-miR-1912-3p | hsa-miR-589-3p |

| hsa-miR-548j-5p | hsa-miR-636 | hsa-miR-541-5p | hsa-miR-493-5p | hsa-miR-125b-2-3p |

| hsa-miR-555 | hsa-miR-606 | hsa-miR-30c-1-3p | hsa-miR-432-3p | hsa-miR-16-2-3p |

| hsa-miR-515-5p | hsa-miR-208b-3p | hsa-miR-629-3p | hsa-miR-454-5p | hsa-miR-650 |

| hsa-miR-340-3p | hsa-miR-367-5p | hsa-miR-377-5p | hsa-miR-936 | hsa-miR-1178-3p |

| hsa-miR-513a-3p | hsa-miR-520d-3p | hsa-miR-630 | hsa-miR-30a-3p | hsa-miR-600 |

| hsa-miR-34a-3p | hsa-miR-1265 | hsa-miR-548d-3p | hsa-let-7g-3p | hsa-miR-599 |

| hsa-miR-342-5p | hsa-miR-1203 | hsa-miR-885-3p | hsa-miR-214-5p | hsa-miR-520g-3p |

| hsa-miR-639 | hsa-miR-548k | hsa-miR-320d | hsa-miR-183-3p | hsa-miR-564 |

| hsa-let-7i-3p | hsa-miR-548a-5p | hsa-miR-2053 | hsa-miR-1179 | hsa-miR-132-5p |

| hsa-miR-543 | hsa-miR-1253 | hsa-miR-675-5p | hsa-miR-562 | hsa-miR-577 |

| hsa-miR-645 | hsa-miR-615-5p | hsa-miR-1252-5p | hsa-miR-579-3p | hsa-miR-223-5p |

| hsa-miR-548d-5p | hsa-miR-607 | hsa-miR-548e-3p | hsa-miR-590-3p | hsa-miR-34b-5p |

| hsa-miR-33a-3p | hsa-miR-1208 | hsa-miR-1914-5p | hsa-miR-130a-5p | hsa-miR-888-3p |

| hsa-miR-664a-3p | hsa-miR-302e | hsa-miR-513c-5p | hsa-miR-563 | hsa-miR-424-3p |

| hsa-miR-1911-5p | hsa-miR-1206 | hsa-miR-331-5p | hsa-miR-200a-5p | hsa-miR-339-3p |

| hsa-miR-33b-3p | hsa-miR-1270 | hsa-miR-1182 | hsa-miR-483-5p | hsa-miR-380-5p |

| hsa-miR-638 | hsa-miR-525-3p | hsa-miR-611 | hsa-miR-15a-3p | hsa-miR-647 |

| hsa-miR-515-3p | hsa-miR-1200 | hsa-miR-1181 | hsa-miR-944 | hsa-miR-518f-5p |

| hsa-miR-548n | hsa-miR-92a-2-5p |

References

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Prz Gastroenterol 2019, 14, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globocan Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/en (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Nguyen, L.H.; Goel, A.; Chung, D.C. Pathways of Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Gastroenterol 2020, 158, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Rectal Cancer Treatment - Health Professional version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/hp/rectal-treatment-pdq#_19 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Glynne-Jones, R.; Wyrwicz, L.; Tiret, E.; Brown, G.; Rödel, C.; Cervantes, A.; Arnold, D. ESMO Guidelines. Ann Oncol 2017, 28, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalady, M.F.; de Campos-Lobato, L.F.; Stocchi, L.; Geisler, D.P.; Dietz, D.; Lavery, I.C.; Fazio, V.W. Predictive factors of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 2009, 250, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolverato, G.; Pucciarelli, S.; Bertorelle, R.; De Rossi, A.; Nitti, D. Predictive factors of the response of rectal cancer to neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2011, 3, 2176–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, E.; Fassan, M.; Maretto, I.; Pucciarelli, S.; Zanon, C.; Digito, M.; Rugge, M.; Nitti, D.; Agostini, M. Serum miR 125b is a non-invasive predictive biomarker of the pre-operative chemoradiotherapy responsiveness in patients with rectal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28647–28657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, I.H.; Garcia-Aguilar, J. Non-operative management of rectal cancer: Understanding tumor biology. Minerva Chir 2018, 73, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoendervangers, S.; Burbach, J.P.M.; Lacle, M.M.; Koopman, M.; van Grevenstein, W.M.U.; Intven, M.P.W.; Verkooijen, H.M. Pathological Complete Response Following Different Neoadjuvant Treatment Strategies for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2020, 27, 4319–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.S.; Zwintscher, N.P.; Johnson, E.K.; Maykel, J.A.; Stojadinovic, A.; Nissan, A.; Avital, I.; Brücher, B.L.D.M.; Steele, S.R. Future directions for monitoring treatment response in colorectal cancer. J Cancer 2014, 5, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.J.; You, Y.N.; Agarwal, A.; Skibber, J.M.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Eng, C.; Feig, B.W.; Das, P.; Krishnan, S.; Crane, C.H.; Hu, C.Y.; Chang, G.J. Neoadjuvant treatment response as an early response indicator for patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.H.; Xiao, J.; An, X.; Jiang, W.; Li, L.R.; Gao, Y.H.; Chen, G.; Kong, L.H.; Lin, J.Z.; Wang, J.P.; et al. Patterns of recurrence in patients achieving pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017, 143, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Xiao, Q.; Venkatachalam, N.; Hofheinz, R.D.; Veldwijk, M.R.; Herskind, C.; Ebert, M.P.; Zhan, T. Predicting response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: from biomarkers to tumor models. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2022, 14, 17588359221077972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedin, C.; Crotti, S.; D’Angelo, E.; D’Aronco, S.; Pucciarelli, S.; Agostini, M. Circulating Biomarkers for Response Prediction of Rectal Cancer to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Curr Med Chem 2020, 27, 4274–4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolskas, E.; Mikulskytė, G.; Sileika, E.; Suziedelis, K.; Dulskas, A. Tissue-Based Markers as a Tool to Assess Response to Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy in Rectal Cancer-Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, A.H.M.; Andersen, R.F.; Pallisgaard, N.; Sørensen, F.B.; Jakobsen, A.; Hansen, T.F. MicroRNA expresion profiling to identify and validate reference genes for the relative quantification of microRNA in rectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaby, O.; Svoboda, M.; Michalek, J.; Vyzula, R. MicroRNAs in colorectal cancer: Translation of molecular biology into clinical application. Mol Cancer 2009, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, M.; Pucciarelli, S.; Calore, F.; Bedin, C.; Enzo, M.V.; Nitti, D. MiRNAs in colon and rectal cancer: A consensus for their true clinical value. Clin Chim Acta 2010, 411, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imedio, L.; Cristóbal, I.; Rubio, J.; Santos, A.; Rojo, F.; García-Foncillas, J. MicroRNAs in Rectal Cancer: Functional Significance and Promising Therapeutic Value. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, C.; Walston, S.; Wald, P.; Webb, A.; Williams, T.M. Molecular profiling of locally-advanced rectal adenocarcinoma using microRNA expression (Review). Int J Oncol 2017, 51, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Kopetz, S.; Davuluri, R.; Hamilton, S.R.; Calin, G.A. MicroRNAs, ultraconserved genes and colorectal cancers. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2010, 42, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizian, A.; Gruber, J.; Ghadimi, B.M.; Gaedcke, J. MicroRNA in rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016, 8, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machackova, T.; Prochazka, V.; Kala, Z.; Slaby, O. Translational potential of microRNAs for preoperative staging and prediction of chemoradiotherapy response in rectal cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crist, I.; Rubio, J.; Santos, A.; Torrej, B.; Caram, C.; Imedio, L.; Luque, M. MicroRNA-199b downregulation confers and predicts poor outcome and response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer patients. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, e1655. [Google Scholar]

- DePalma, F.D.E.; Luglio, G.; Tropeano, F.P.; Pagano, G.; D’Armiento, M.; Kroemer, G.; Maiuri, M.C.; De Palma, G.D. The Role of Micro-RNAs and Circulating Tumor Markers as Predictors of Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy in Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakarnsanga, A.; Gönen, M.; Shia, J.; Nash, G.M.; Temple, L.K.; Guillem, J.G.; Paty, P.B.; Goodman, K.A.; Wu, A.; Gollub, M.; et al. Comparison of Tumor Regression Grade Systems for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer After Multimodality Treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014, 106, dju248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiagen Gene Globe. Available online: https://geneglobe.qiagen.com/us/analyze (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Lee, M.-L.T.; Whitmore, G.A. Power and sample size for DNA microarray studies. Stat Med 2002, 21, 3543–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaedcke, J.; Grade, M.; Camps, J.; Søkilde, R.; Kaczkowski, B.; Schetter, A.J.; Difilippantonio, M.J.; Harris, C.C.; Ghadimi, B.M.; Møller, S.; Beissbarth, T.; Ried, T.; Litman, T. The rectal cancer microRNAome microRNA expression in rectal cancer and matched normal mucosa. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18, 4919–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 3, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunigenas, L.; Stankevicius, V.; Dulskas, A.; Budginaite, E.; Alzbutas, G.; Stratilatovas, E.; Cordes, N.; Suziedelis, K. 3D Cell Culture-Based Global miRNA Expression Analysis Reveals miR-142-5p as a Theranostic Biomarker of Rectal Cancer Following Neoadjuvant Long-Course Treatment. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Zhai, B.; Zheng, Y.; Ren, R.; Han, M.; Wang, X. Transcatheter arterial infusion chemotherapy increases expression level of miR-142-5p in stage III colorectal cancer. Indian J Cancer 2015, 52 Suppl 2, e47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cervena, K.; Novosadova, V.; Pardini, B.; Naccarati, A.; Opattova, A.; Horak, J.; Vodenkova, S.; Buchler, T.; Skrobanek, P.; Levy, M.; Vodicka, P.; Vymetalkova, V. Analysis of MicroRNA Expression Changes During the Course of Therapy In Rectal Cancer Patients. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 702258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, F.; Gopalan, V.; Vider, J.; Lu, CT.; Lam, A.K. MiR-142-5p act as an oncogenic microRNA in colorectal cancer: Clinicopathological and functional insights. Exp Mol Pathol 2018, 104, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sameti, P.; Tohidast, M.; Amini, M.; Bahojb Mahdavi, S.Z.; Najafi, S.; Mokhtarzadeh, A. The emerging role of MicroRNA-182 in tumorigenesis; a promising therapeutic target. Cancer Cell Int 2023, 23, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Du, L.; Wen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Li, W.; Zheng, G.; Wang, C. Up-regulation of miR-182 expression in colorectal cancer tissues and its prognostic value. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013, 28, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapti, S.M.; Kontos, C.K.; Papadopoulos, I.N.; Scorilas, A. Enhanced miR-182 transcription is a predictor of poor overall survival in colorectal adenocarcinoma patients. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014, 52, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, R. MiR-182 contributes to cell proliferation, invasion and tumor growth in colorectal cancer by targeting DAB2IP. Oncol Lett 2020, 19, 3923–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.H.; Yu, J.; Jiang, D.M.; Li, W.L.; Wang., S.; Ding, Y.Q. MicroRNA-182 targets special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 to promote colorectal cancer proliferation and metastasis. J Transl Med 2014, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Pan, Y.; Shan, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, L. Upregulation of microRNA-135b and microRNA-182 promotes chemoresistance of colorectal cancer by targeting ST6GALNAC2 via PI3K/AKT pathway. Mol Carcinog 2017, 56, 2669–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Pinelo, S.; Carnero, A.; Rivera, F.; Estevez-Garcia, P.; Bozada, J.M.; Limon, M.L.; Benavent, M.; Gomez, J.; Pastor, M.D.; Chaves, M.; Suarez, R.; Paz-Ares, L.; de la Portilla, F.; Carranza-Carranza, A.; Sevilla, I.; Vicioso, L.; Garcia-Carbonero, R. MiR-107 and miR-99a-3p predict chemotherapy response in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dworak | Explanation |

| 0 | No response. |

| 1 | Minimal response to the treatment (predominant tumour tissue with slight fibrosis, vasculopathy; fibrosis <25% of the tumour mass). |

| 2 | Moderate response to the treatment (fibrotic changes dominate, separate tumour groups are observed; fibrosis 25-50% of the tumour mass). |

| 3 | Almost complete response to the treatment (some tumour cells in fibrotic tissue with/without presence of mucin; fibrosis >50% of the tumour mass). |

| 4 | Complete response to the treatment (no tumour cells, only fibrotic tissue or acellular mucin collections). |

| BR group N=17 |

GR group N=23 |

|

|---|---|---|

| PRE-TREATMENT PARAMETERS | ||

|

Gender Male Female |

11 6 |

12 11 |

| Age (mean, range) | 66.47 (41-83) | 65.52 (55-77) |

|

Stage of rectal cancer II III |

3 14 |

1 22 |

|

Tumour grade Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 |

6 10 1 |

9 11 3 |

|

Serum CEA prior to nCRT: CEA ≤5.5 ng/ml CEA >5.5 ng/ml Serum CA19-9 prior to nCRT: CA19-9 ≤33 U/ml CA19-9 >33 U/ml |

15 2 17 0 |

19 4 23 0 |

|

Radiological parameters (pelvic MRI): tumour length (range, mean; cm) tumour circumference (range, mean; %) tumour distance from anal verge (range, mean; cm) node positive disease |

3-11; 6.9 50-100; 88 0-14; 6.9 14 |

3-9; 5.1 25-100; 65 1,5-11; 5.7 21 |

| TREATMENT PARAMETERS | ||

|

Radiation therapy (range of doses; Gy): tumour pelvic lymph nodes |

50.4 – 54 45 – 46.8 |

50.4 – 54 45 – 46.8 |

|

Chemotherapy (type, the way of administration): 5FU, i/v FOLFOX6, i/v Leucovorini + 5FU, i/v Capecitabine, p/o Oxaliplatine, i/v |

12 2 3 0 0 |

13 3 5 1 1 |

|

Surgery: AR HP APR TR |

10 3 4 0 |

12 5 5 1 |

| POST-TREATMENT PARAMETERS | ||

|

Radiological parameters: mrTRG1 mrTRG2 mrTRG3 mrTRG4 mrTRG5 Not done or cannot be evaluated (CT-scan done instead of MRI) |

0 0 7 6 0 4 |

1 8 4 3 0 7 |

|

Morphological parameters Tumour distance from RL (range; cm) Tumour length (range; cm) T stage T1 T2 T3 T4 N stage N0 N1 N2 Mucinous component ≥50% <50% not present Stromal desmoplasia mild moderate severe Inflammatory infiltration mild moderate severe Differentiation Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Perineural invasion Yes No Vascular invasion Yes No Lymphatic invasion Yes No |

0.5-8 1.5-7.5 1 5 10 1 12 2 3 4 0 13 6 8 3 7 7 3 2 14 1 2 15 1 16 7 10 |

0.5-6 0.8-5 1 9 12 1 16 6 1 0 5 18 14 4 5 18 5 0 4 13 6 4 19 0 23 7 16 |

|

Serum CEA after nCRT: CEA ≤5.5 ng/ml CEA >5.5 ng/ml Serum CA19-9 after nCRT: CA19-9 ≤33 U/ml CA19-9 >33 U/ml |

17 0 17 0 |

23 0 23 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).